Cosmetic surgery is a rapidly growing medical specialty both in the numbers of patients treated and in the techniques and approaches available. This review consolidates the information available on cosmetic surgery from popular literature, the media, and advisory services.

Doctors differ in their attitude to surgery for cosmetic reasons only. Patients requesting such surgery are usually normal individuals, but with a heightened consciousness about their looks. A proportion of them may seek advice on what, to them, seems an unsatisfactory appearance. They deserve the same professional approach and empathy as patients seeking help for clinical disorders. I would like to encourage the non-specialist to approach cosmetic surgery objectively. By understanding what may be achieved cosmetically, patients can receive invaluable advice, and appropriate referrals can be organised.

Summary points

Cosmetic surgery remains highly dependent on the skill of the operator, and technological advance should be viewed with this in mind

Large volume infiltration can reduce the cost to benefit ratio for selected indications

Lasers have a relatively limited niche in medical aesthetics

No single method of breast augmentation has all advantages

Three surgical procedures can correct facial ageing: resurfacing, subdermal augmentation, and face lift surgery

Multidisciplinary team work is a practical way to provide a comprehensive service for the patient requiring cosmetic surgery

Methods

This article is based largely on my experience in a multidisciplinary medical team dedicated to aesthetics and health. Recent concepts that have changed the management of patients undergoing cosmetic surgery are incorporated. I have supplemented reviews with articles from high quality journals, and general references are from textbooks.

Extent of cosmetic surgery

Requests for cosmetic surgery can be divided into three categories: correction of abnormal features (eg prominent ears, a large nose, gigantomastia, breast hypoplasia, hirsutism); reversal of the signs of ageing (eg facial wrinkles and creases, thinning hair and baldness, irreversible skin stretching, drooping of prominent tissue such as breasts and buttocks); and treatment of health related problems (eg obesity, tooth decay, abdominal bloating, cellulite, facial fluid retention, chronic skin problems, brittle hair and nails). None of these conditions can be classified as overt clinical disease. Nevertheless, their correction or treatment can significantly enhance patients’ self perception and reduce self consciousness.

Patients requesting cosmetic surgery are generally well, so surgical risks should be minimal.

Anaesthetic techniques

Recent advances in anaesthetic techniques have reduced the need for general anaesthesia for certain cosmetic procedures, adding to the popularity of cosmetic surgery.1 Large volumes of dilute local anaesthetic and adrenaline are now used for subcutaneous infiltration, enabling up to 10% of the body surface to be anaesthetised locally and perioperative bleeding to be significantly reduced. Therefore haemodynamic stability can be maintained without intravenous fluid replacement or blood transfusion.2,3

Infiltration with a large volume of local anaesthetic furthermore reduces the need for general analgesics. Hypnotics can also be avoided in favour of intravenous sedation for simple procedures, so patients can keep control of their airway and vital functions. Such patients can even be upright during the procedure, and the surgeon can observe the effects of gravity and voluntary muscle activity during surgery.

Minor cosmetic procedures can take place safely under intravenous sedation in the doctor’s surgery.4 For more extensive surgery requiring general anaesthetic or intravenous sedation, hospital remains the best choice.

Cosmetic procedures

Liposuction

Aspiration of diet resistant fat is the most popular cosmetic surgical procedure. Requests for liposuction commonly include the abdominal wall, hips, buttocks, thighs, inside of the knees, and the back. Liposuction can also enhance the arms and the contours of the face and neck.

As fat cells do not regenerate in adults, areas undergoing liposuction are generally treated permanently. Increases in body weight after surgery, however, may lead to fat being preferentially deposited in untreated areas. Liposuction for progressive obesity cannot be recommended as a substitute for modification of life style.

Patients with localised fat deposits are best treated at a young age, as the effects of gravity may be difficult to reverse after the third decade.5

Originally, liposuction took place under general anaesthesia, using large bore cannulae and no infiltration.6 This resulted in a bloody operation with inherent sequelae and complications (ecchymosis, haematoma, haemosiderosis, infection5,6). Irregularities of body shape were common because of the use of large cannulae and high vacuum suction, and because patients could not cooperate during surgery.5,7 Substantial fluid loss also limited the amount of fat that could be aspirated.

Currently, about 5 or 6 litres of fluid are infiltrated during an average liposuction.3,6 The widest cannula used (4 mm diameter) is for deep deposits. The finest aspiration needles of 2 mm or 3 mm diameter are used to treat fat in the immediate subdermal layer. This technique causes little damage to fibrous and nervous tissues and blood and lymph vessels. Postoperatively, the skin has a tendency to firm up towards the deep fascia. Hence scars can often be avoided from the excision of redundant skin. Liposuction is the treatment of choice for fat on the abdomen, back, and buttocks. Even patients with breast hypertrophy can benefit from liposuction, particularly when young.8

Modern liposuction techniques depend on the surgeon expending much energy, so methods to reduce physical effort are constantly being developed—for example, devices with an ultrasonic generator at the tip to implode fat cells before aspiration.6 The device may also reduce the chance of small irregularities.5–7 Pneumatically driven devices are being developed to reduce operating times and to improve the results in virginal breast hypertrophy, gynaecomastia, tight male fat, and repeat surgeries. Most of these techniques are still controversial, and their future in liposuction is unclear.

Autologous fat transfer

Fat harvested by liposuction can be used to fill hollows and folds. Evidence shows that at least some of this fat survives as a graft.9,10

Transferred fat can be used to rejuvenate the face and to contour the body. The procedure needs repeating at least once, but long term results are reasonably predictable.9

Endoscopically assisted procedures

It took until the nineties before keyhole surgery could be extended to cosmetic surgery,11–13 because manufacturers had to design suitable instruments and find ways to create an optic cavity.

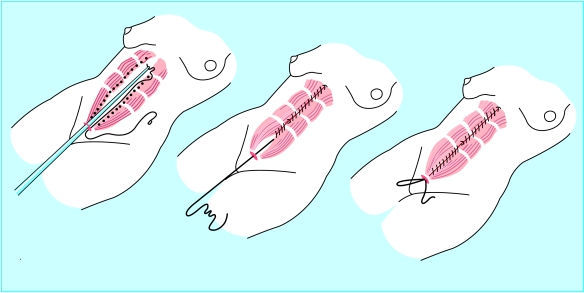

Keyhole cosmetic surgery first began with the insertion of inflatable breast implants via the umbilicus.14 At the same time, endoscopic techniques were developed for plication of abdominal muscle (figure).11–14 This was soon followed by requests for facial surgery.13

Sagging eyebrows and forehead creases can be corrected through keyhole incisions in the scalp. This approach has become the standard for many surgeons, and insights into facial movement have enabled more functional surgery to be performed.13

For selected abdominal requests, liposuction can replace traditional abdominoplasty, which leaves a long horizontal scar.11,12

Breast implants

Following the controversy over silicone breast implants, the use of any form of silicone gel for breast augmentation is forbidden in the United States and France.15 This has led to a search for alternative materials,16 such as a new cohesive form of silicone. The cohesiveness of the filling should reduce the chance of leakage after rupture or puncture. Alternatives to silicone are normal saline, hydrogel, and methylcellulose gel. Regardless of filling used, implants still have a silicone elastomer outer envelope, which acts as an inert interface between the implant and the host.

Surgery for breast augmentation entails the implantation of a foreign body into the subglandular or subpectoral plane. This procedure has several possible sequelae and complications (table1). No one method has all advantages.

Laser surgery

Laser technology has progressed rapidly,17 although one machine for all indications seems impossible to achieve at this stage. For a centre to cover all indications, at least three or four machines are required. This is often prohibitively expensive.

Red lesions

Red lesions can be treated by a pulsed dye laser with a spectrum of absorption of the colour of haemoglobin.18 Photothermal energy conversion coagulates the capillaries, which improves the appearance of the lesions. Laser treatment is the method of choice for port wine stains, which respond well if the patient is young. Other superficial vascular lesions can be treated by laser provided the capillaries are not too wide.

Telangiectasia on the legs does not respond to laser treatment. It is still treated by microsclerosis in those patients whose capillaries are wide enough to accommodate a fine needle. I use radiosurgery in patients with capillaries of a small diameter.19

Tattoo removal

Tattoos can be removed by laser, which breaks down the ink particles into fragments small enough for macrophages to digest.20,21 This Q switched (short pulse length) type of laser is only useful for professional tattoos. Traditional excision techniques are reserved for post-traumatic tattoos—that is, embedded dirt from insufficiently cleaned wounds—and amateur tattoos and for residues left after laser treatment.

Skin resurfacing

Removing the top layers of the dermis promotes regeneration of collagen, elastine, and epidermis. This rejuvenates the facial skin long term and improves fine wrinkling. Skin resurfacing can also remove superficial blemishes such as the brown spots of ageing, dilated capillaries, and small keratoses.

Traditional resurfacing methods include chemical peeling and dermabrasion.22,23 A chemical peel causes a chemical burn. Dermabrasion mechanically removes the epidermis and a variable layer of dermis. Recently, a rapid scanning device has been added to the cutting laser, enabling a predictable depth of skin to be destroyed.24

Resurfacing methods treat superficial wrinkles and repair skin aged by light. The results are ultimately dependent on the skill of the operator.

Resurfacing does not help the gravitational descent of facial tissue at subdermal level. Such tissue needs face lift surgery (table 2).

Table 2.

Surgical solutions for facial ageing

| Skin layer | Appearance | Surgical solution |

|---|---|---|

| Dermis | ||

| Problem: | ||

| Thinning and loss of elasticity | Superficial wrinkles | Resurfacing: chemical, mechanical, laser |

| Irreversible stretching | Creases, nasolabial folds, eyelid bags, submandibular skin excess | Excision: face lift surgery |

| Subdermis | ||

| Problem: | ||

| Progressive hypotrophy | Cheek hollow, lip thinning, nasolabial folds | Augmentation: autologous fat transfer, biodegradable substitutes, non-degradable materials |

| Gravitational descent | Sagging eyebrows, malar bags, nasolabial folds, jowls, platysma descent, witches’ chin | Repositioning: face lift surgery |

Brown lesions

Pulsed dye lasers with the spectrum of absorption of melanin can destroy melanophores responsible for brown lesions.25 These lasers only work reliably for superficial pigmentation. Unfortunately, they also remove normal pigment, which may result in bleaching of the skin. Most superficial brown spots can be treated by resurfacing, but there is a risk of topical depigmentation.22,23

Bloodless incisions

The carbon dioxide laser is a potentially dangerous instrument for the surgeon to use as there is no tactile feedback—that is, with a laser beam the surgeon can see but not feel what is going on.26 As such, radiosurgery is now gaining popularity, and its radiowaves precisely destroy tissue.19,26,27

Hair removal

Although laser depilation is intensively promoted, it is still under development.28 Often it leads to permanent hair bleaching without affecting hair density long term. Healing problems after laser depilation of the legs are not unknown.

Traditional bleaching and waxing techniques are at this stage unsurpassed for general use. For permanent depilation, radiosurgery is a good alternative for thick and less numerous hairs—for example, on naevi, around the areola, or areas of the face or bikini line.26

Injection techniques to combat ageing

Wrinkles and creases indicate ageing. Some of these can be improved by the local injection of materials to support skin.29

Bovine collagen

—This is used to temporarily fill out superficial wrinkles and deep creases. Antigenic reactions can occur.30

Hylan gel

—This is a synthetic substance of recent development. It is suitable for fine wrinkles, but its effects are short term.31

Permanent materials

Some materials on the market are simple to apply but difficult to remove.32 Microspheres of polymethylmethacrylate in a collagen matrix, and cristalline silicone, are used for subdermal injection.33,34,29 Their use is limited to deep folds, depressions, and lip augmentation.

Autologous fat injection

—This is a cheap and safe method for facial depressions, lip augmentation, and deep folds.8,9 It usually needs repeating. The medium term effects are encouraging for most patients.

Botulinum toxin

—This selectively paralyses muscles for 3-9 months. It is mainly used to correct glabellar frown lines and occasionally “crow’s feet” overlying an over active orbicularis oculi muscle.35

Hair restoration

Surgery and prosthetics

Surgery to cover bald areas has moved from the use of punch grafts and flaps that bear hair, “balloon” tissue expansion techniques, or microsurgery to the more reliable technique of micrografting.36,37

A strip of scalp is harvested from the occipital area of a donor and divided into individual follicles. These are grafted on to the bald area of the recipient. In some centres a powerful cutting laser is used to burn holes in the recipient’s scalp to receive the grafts.38 There is no proved benefit from using a laser, but there is the potential for damage to existing hair follicles. A natural density of hair growth is achieved after two or three sessions.

The most major advance in hair prosthetics has been the development of a skin glue, which attaches a hair piece for 4-6 weeks.39 The hair piece can be used in conjunction with micrografting for restoration of frontal hair. The combination of surgery and prosthetics allows for a natural look without limiting hair density.

Conclusion

Recently the cost to benefit ratio of cosmetic surgery has decreased substantially (table 3). This is reflected in an ever increasing demand for such treatment. General practitioners may be confronted both with preoperative planning and postoperative care of such patients.

Table 3.

Decrease in cost to benefit ratio responsible for increased demand in cosmetic surgery

| Benefits | Costs |

|---|---|

| Increase in: | Decrease in: |

| Indications | Expenses |

| Results | Surgical complications |

| Availability | Scars |

| Day surgery | Anaesthetic sequelae |

| Combined procedures | Time off work |

Patients requiring cosmetic surgery seek advice from the medical profession, healthcare workers, the media, beauticians, and other patients. A professional interest in cosmetic surgery may serve the public well.

Figure.

Endoscopic rectus plication. Reproduced with permission from Bostwick et al 11

Table 1.

Likelihood, on a scale of 1 (non-existant) to 6 (inevitable or maximal0, of outcome after breast augmentation using various implamts

| Filling, envelope surface, site | Access | Capsular contraction | Deflation after puncture | Content biodegradable | Mobility abnormality | Gravitational descent of implant | Overriding ptosis of residual breast | Rippling or folding of wall | Size limitations | Muscular distraction of overlying muscle |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cohesive silicone gel | ||||||||||

| Textured: | ||||||||||

| Prepectoral | Inframammary | 3 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 1 |

| Liquid silicone gel | ||||||||||

| Textured: | ||||||||||

| Prepectoral | Inframammary | 4 | 5 | 1 | 6 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 1 |

| Retropectoral | Transaxillary | 2 | 5 | 1 | 6 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 5 | 4 |

| Smooth: | ||||||||||

| Prepectoral | Inframammary, transaxillary, transareolar | 2 | 5 | 1 | 6 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 4 |

| Retropectoral | Inframammary, transaxillary, transareolar | 5 | 5 | 1 | 6 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 1 |

| Saline implants (inflatable) | ||||||||||

| Smooth: | ||||||||||

| Prepectoral | Transumbilical | 3 | 6 | 6 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 1 |

| Retropectoral | Inframammary, transaxillary, transareolar | 2 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 |

| Textured: | ||||||||||

| Prepectoral | Transaxillary- inframammary | 3 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 1 |

| Retropectoral | Transaxillary- transareolar | 2 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 |

| Methylcellulose gel | ||||||||||

| Prepectoral | Inframammary, transareolar | 3 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 1 |

| Retropectoral | Transareolar- transaxillary | 2 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 4 |

1=non-existent; 2=highly unlikely or minimal; 3=uncommon; 4=not uncommon; 5=likely; 6=inevitable or maximal.

Footnotes

Funding: None.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Aston SJ, Beasley RW, Thorne CHM. Grabb and Smith’s plastic surgery, 5th edn. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven; 1997. p. 101. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klein JA. Tumescent technique for local anaesthesia improves safety in large-volume liposuction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1993;92:1085–1098. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rohrich RJ, Berau SJ, Fodor PB. The role of subcutaneous infiltration in suction-assisted lipoplasty: a review. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997;99:1–6. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199702000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baker TJ, Gordon HL, Stuzin JM. Surgical rejuvenation of the face, 2nd edn. St Louis, MO: Mosby Year Book; 1996. pp. 11–44. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dillerud E. Suction lipoplasty: a report on complications, undesired results and patient satisfaction based on 3511 procedures. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1991;88:239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zocchi ML. Advances in plastic and reconstructive surgery. St Louis, MO: Mosby Year Book; 1995. pp. 197–221. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ning Chang K. Surgical correction of post liposuction contour irregularities. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1994;94:126. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199407000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maxwell GP, White DJ. Operative techniques in plastic and reconstructive surgery. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 1996. Breast reduction with ultrasound-assisted liposuction. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roddi R, Gilbert PM, Vaandrager JM, van der Meulen JCH. The value of microfat injection “lipofilling” in the treatment of soft tissue deformities of the face in Parry-Romberg syndrome. Eur J Plast Surg. 1994;17:79–83. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coleman WP. Autologous fat transplantation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1991;88:736. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199110000-00038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bostwick J, III, Eaves F, III, Nahai F. Endoscopic plastic surgery. St Louis, MO: Quality Medical; 1995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramirez OM, Daniel RK. Endoscopic plastic surgery. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Isse NG. Endoscopic facial rejevenation: endoforehead, the functional lift. Aesth Plast Surg. 1994;18:21–29. doi: 10.1007/BF00444243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson GW, Christ JE. The endoscopic breast augmentation: the transumbilical insertion of saline-filled breast implants. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1993;92:801. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cooper C, Dennison E. Do silicone breast implants cause connective tissue disease? BMJ. 1998;361:403–404. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7129.403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aston SJ, Beasley RW, Thorne CHM. Grabb and Smith’s plastic surgery, 5th edn. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven; 1997. pp. 713–723. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aston SJ, Beasley RW, Thorne CHM. Grabb and Smith’s plastic surgery, 5th edn. Philadelphia, PA: Lippencott-Raven; 1997. pp. 205–219. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Achauer BM, Van der Kam VM, Padilla JF., III Clinical experience with the tunable pulsed-dye laser (585 mm) in the treatment of capillary vascular malformations. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1993;92:1233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Havas DR, Noodleman R. Using a low current radiosurgical unit to obliterate telangiectasias. J Dermatolog Surg Oncol. 1991;17:382–383. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.1991.tb01715.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reid WH, McLeod PJ, Ritchie A, Ferguson-Pell M. Q-switched ruby laser treatment of black tattoos. Brit J Plast Surg. 1983;36:4559. doi: 10.1016/0007-1226(83)90128-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fitzpatrick RE, Goldmann MP, Dierckx C. Laser ablation of facial cosmetic tattoos. Aest Plast Surg. 1994;18:91. doi: 10.1007/BF00444255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Glogan RG, Matarasso SL. Chemical peels, trichloroacetic acid and phenol. Dermatol Clin. 1995;13:25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Benedetto AV, Griffin TD, Benedetto EA, Humenink HM. Dermabrasion: therapy and prophylaxis of the photoaged face. J Am Acad Dermatolog. 1992;27:439–447. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(92)70214-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kanvar ANB, Geronimu RG, Waldorf HA. Char-free tissue ablation: a comparative histopathologic analysis of new carbon dioxide (CO2) laser systems. Lasers Surg Med. 1995;16:50. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grekin RC, Shelton RM, Geisse JK, Frieden I. 510 nm pigmented lesion dye laser: its characteristics and clinical uses. J Dermatolog Surg Oncol. 1993;19:380–387. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.1993.tb00361.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Raus P, Mertens E. Evaluation of radiosurgery as a cosmetic surgery technique. Int J Aest Restor Surg. 1997;2:96–100. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pfenningen JL, Fowler GC. Procedures for primary care physicians. St Louis, MO: Mosby; 1994. pp. 91–101. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grossmann MC. Laser targeted at hair follicles. Lasers Surg Med. 1995;7:47. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spiza M, Rosen T. Injectable soft tissue substitutes. Clin Plast Surg. 1993;20:181–188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Orgentas HE, Pindur A, Spiza M, Liu B, Shenag S. A comparison of soft tissue substitutes. Ann Plast Surg. 1994;33:171–177. doi: 10.1097/00000637-199408000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Piacquadio D, Jarebo M, Goltz R. Evaluation of hylan b gel as a soft tissue augmentation implant material. J Ann Acad Derm. 1997;36(4):544–549. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(97)70241-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Male B. The use of Gore-Tex implants in aesthetic surgery of the face. Plast Recon Surg. 1992;90:200–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lemperle G, Haran-Gauthier N, Lemperle M. PMMA microspheres (Artecoll) for skin and soft tissue augmentation. Part II: clinical investigations. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995;96:627–634. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199509000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McClelland M, Egbert B, Hando V, Berg R, Delustro F. Evaluation of artecoll polymethyl-methylmethacrylate implant for soft tissue augmentation: biocompatibility and chemical characterization. Plast Recon Surg. 1997;100:1466–1474. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199711000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guyuron B, Huddleston SW. Aesthetic indications for botulinum toxin injection. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1994;93:913–918. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199404001-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Uebel CO. The punctiform technique with 1000 micro- and minigrafts in one stage. Am J Cosm Surg. 1994;11:293–303. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Uebel CO. Baldness surgery: the mega-punctiform technique. Plast Surg Techniques. 1995;1(2):95–103. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Unger W, David L. Laser hair transplanting. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1994;20:515. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.1994.tb00136.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Material safety data sheet. Dronten: HairTech Holland; 1998. Derma flesh perfector plus: medical grade adhesive for skin contact. [Google Scholar]