Sir,

Port-wine stain (PWS) is a type of congenital capillary malformation characterized by the presence of dilated but otherwise normal capillaries in the dermis, without any associated endothelial proliferation. Our case report presents a distinct and unusual manifestation of PWS characterized by a rapid onset of hypertrophy and nodularity, suggestive of a combined malformation comprising capillary, lymphatic and arteriovenous components.

A 32-year-old man presented with a large purple macule on the right side of the head that had been present since birth. There has been a recent swelling and nodularity on this for the last 6 months [Figure 1a]. The patient also reported serous, bloody and purulent discharge for the past month.

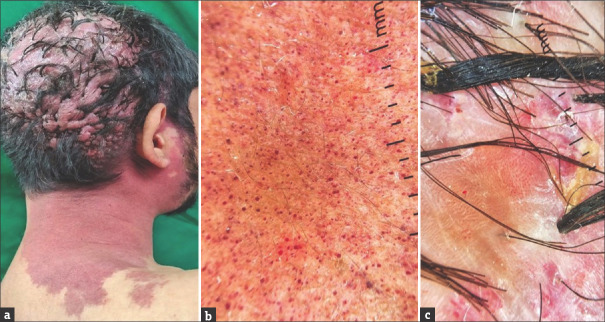

Figure 1.

(a) Port-wine stain extending from the right side of the parieto-occipital region to the side of the neck with multiple hypertrophic, flesh-coloured soft nodules coalescing to form a cerebriform appearance on the parieto-occipital region. (b) Dermoscopy from PWS patch showed red dotted and globular vessels (DermLite DL3N, dry, contact, polarized, x10). (c) Dermoscopy from cerebriform plaque showed red dotted and globular vessels along with white and red structureless areas, tufted hairs and yellowish crusting (DermLite DL3N, dry, contact, polarized, x10)

On examination, a well-defined, purple macule extends from the right side of the parieto-occipital region below to the side of the neck. There were multiple hypertrophic, flesh-coloured soft nodules coalescing to form a cerebriform appearance on the parieto-occipital region. On palpation, there were non-tender, non-pulsatile, soft swellings that were warm to touch. A complete ophthalmological examination showed no abnormalities. The dermoscopy was conducted from the PWS patch and cerebriform plaque, both showing red dotted and globular vessels [Figure 1b and c].

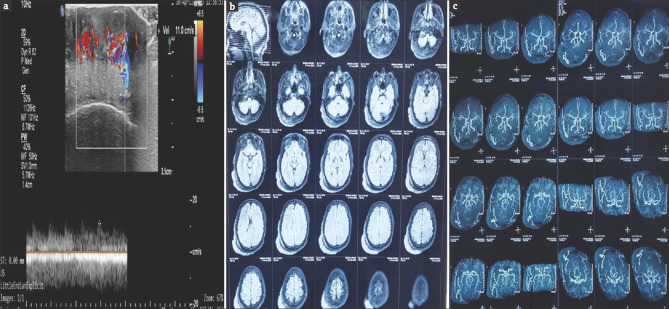

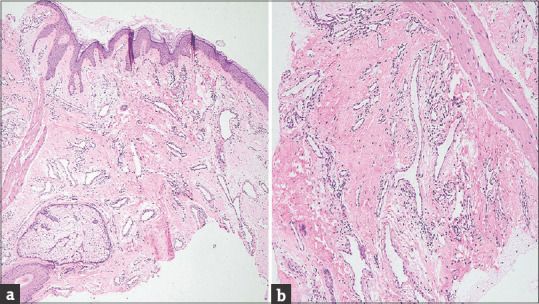

An ultrasonography Doppler study of the lesion revealed multiple dilated arterial and venous channels with an arterial peak systolic velocity of 20 cm/sec [Figure 2a]. The magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain showed arterial channels in the lesion, suggestive of a vascular origin [Figure 2b]. MRI angiography showed prominent vascular channels arising from the right external carotid branches [Figure 2c]. A biopsy of the lesion from the cerebriform plaque showed the entire dermis with variable-sized dilated lymphatic channels lined by endothelial cells suggestive of a lymphatic malformation [Figure 3]. The patient was diagnosed with combined vascular malformation known as capillary–lymphatic–arteriovenous malformation (CLAVM). The patient was referred to the Interventional Radiology Department for Digital Subtraction Angiography and Sclerotherapy using sodium tetradecyl sulphate under fluoroscopy guidance.

Figure 2.

(a) An ultrasonography Doppler study of the lesion revealed multiple dilated arterial and venous channels with an arterial peak systolic velocity of 20 cm/sec. (b) MRI of the brain showing arterial channels in the lesion, suggestive of a vascular origin. (c) MRI angiography showing prominent vascular channels arising from the right external carotid branches

Figure 3.

(a) Epidermis with hyperkeratosis and low papillomatosis. The dermis shows variable-sized dilated lymphatic channels (H and E; 40X). (b) lymphatic channels lined by prominent endothelial cells and surrounded by mild chronic inflammation (H and E 100X)

Port-wine stains (PWSs) are the second most common congenital vascular malformation observed in infancy. The development of PWS is suggested to be associated with irregularities in neural development and genetic mutations (GNAQ). PWSs are well-defined macules that can be pink, red or purple in colour. Facial PWSs usually present as isolated birthmarks, but 10% of cases involving the first branch of the trigeminal nerve are associated with Sturge–Weber syndrome (SWS). Other associated syndromes are Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome, Proteus syndrome and Cobb syndrome.

Over time, PWS may darken and thicken due to hypertrophy and nodularity development. This can increase the risk of spontaneous bleeding or bleeding upon injury. About two-thirds of patients with PWS develop these changes in their fifth decade of life, with a mean age of hypertrophy noted at 37 years. Hypertrophy has been described as an increase in the ectasia without an increase in the number of vessels. The lack of neural modulation of blood flow in PWS can result in subsequent ischemia in turn leading to neuronal dysfunction terminating in a vicious circle, possibly explaining the development of hypertrophy.[1]

Nodules are suggestive of pyogenic granulomas, angiomas, cavernous haemangiomas and arteriovenous malformations.[2] The age-related collagen degeneration can weaken the supporting dermal structures which make the underlying malformation evident with time. Pyogenic granuloma is a well-known complication of PWS, typically occurring on the neck, trunk or extremities.[3] Nodularity can also be rarely associated with intralesional basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma.[4] Although rare, there have been a few reported cases of combined capillary–lymphatic malformation in individuals with PWS.[5] However, most of these cases were associated with syndromes such as Proteus syndrome and Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome.

In our case, there was a rapid development of nodularity with features of a combined vascular malformation that included both arteriovenous and lymphatic components on a pre-existing capillary malformation. This development occurred within a remarkably short period of just 6 months, which is in contrast to the gradual development that is usually observed. It is possible that the rapid development of nodularity could be attributed to an unnoticed trauma.

The management of PWS involves various treatment modalities, including pulsed dye laser (PDL), intense pulsed light (IPL) systems, alexandrite and Nd: YAG lasers. Topical agents such as timolol, imiquimod and rapamycin may be used in combination with laser therapy but these modalities are not very effective for the treatment of nodularity. Additional treatment options include ultrasound sonography/computed tomography (USG/CT)-guided sclerotherapy and surgical excision. In our patient, a digital subtraction angiography-guided sclerotherapy using sodium tetradecyl sulphate was conducted.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form, the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Updyke KM, Khachemoune A. Port-Wine stains: A focused review on their management. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16:1145–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen D, Hu XJ, Lin XX, Ma G, Jin YB, Chen H, et al. Nodules arising within port-wine stains: A clinicopathologic study of 31 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:144–51. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0b013e3181e169f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sheehan DJ, Lesher JL., Jr Pyogenic granuloma arising within a port-wine stain. Cutis. 2004;73:175–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Minkis K, Geronemus RG, Hale EK. Port wine stain progression: A potential consequence of delayed and inadequate treatment? Lasers Surg Med. 2009;41:423–6. doi: 10.1002/lsm.20788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wimmershoff MB, Schreyer AG, Glaessl A, Geissler A, Hohenleutner U, Feuerbach SS, et al. Mixed capillary/lymphatic malformation with coexisting port-wine stain: Treatment utilizing 3D MRI and CT-guided sclerotherapy. Dermatol Surg. 2000;26:584–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4725.2000.00004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]