Abstract

We report a case of a 54-year-old female diagnosed with HIV and antiretroviral therapy (ART) for the same. Seven years ago, she suffered from fever, cough and weight loss, was diagnosed with pulmonary tuberculosis and also seropositive for HIV. She suffered from Herpes Zoster infection, after which her ART regimen was changed to TLD (tenofovir, lamivudine and dolutegravir). The patient presented with two episodes of pyoderma gangrenosum (PG), which were biopsy-proven, corresponding to a rise in CD4 counts above 500. She responded to glucocorticoids, both systemic and topical.

Keywords: CD4, PLHIV, pyoderma gangrenosum, TLD

Introduction

Pyoderma gangrenosum (PG) is categorised as inflammatory neutrophilic dermatosis, caused by innate and acquired Immunity disturbances and often associated with various autoimmune diseases. Diagnosis is confirmed by biopsy of the lesion. Most lesions respond to Glucocorticoids.

Case Report

In October 2015, the patient presented with fever, cough and weight loss. She was concurrently diagnosed with HIV and pulmonary tuberculosis; her CD4 was 203. After 2 weeks of anti-tubercular treatment, the patient was started on ART (tenofovir, efavirenz, and emtricitabine). She continued ART but stopped AKT 5 months later. Her CD4 rose to 571 in 2017.

In January 2021, the patient suffered from Herpes Zoster infection. Her regimen was changed to TLD (tenofovir, lamivudine and dolutegravir).

Later, in August 2021, the patient presented with vesicular lesions over the hands, feet, back, neck, and oral mucosa. Biopsy reported lesions as pustular pyoderma gangrenosum. She was given an intralesional steroid every 4 days for seven doses and a prednisolone tablet 40 mg daily, slowly tapered over 6 months.

In June 2023, the patient again presented with fever, abdominal pain and loose stools for 1 day after which she had a spontaneous eruption of blisters on the palmar aspect of the hand and fingers associated with pain and serous discharge.

Vaccination History: Covaxin, December 2021, May 2022

Diagnosis: PLHIV, with gastro-intestinal infection with pyoderma gangrenosum. Laboratory and radiological investigations were normal except for haemoglobin 10.7 gm% and total leucocyte count 13000. ANA negative. ESR 98 mm/hour, CRP 134, CD4 count on this admission: 723.

Treatment given: Injection ceftriaxone and metronidazole.

For oral ulcers: cotrimoxazole lotion, tablet fluconazole 150 mg, prophylactic tablet cotrimoxazole DS, local Clobetasol, and mupirocin ointment. TLD regimen was continued.

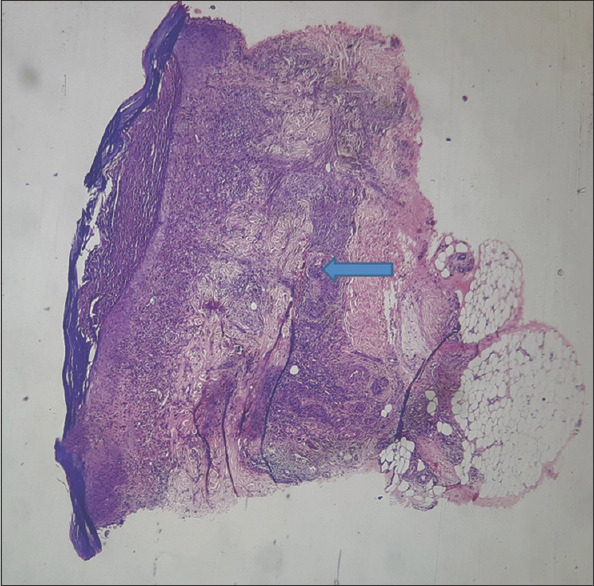

Histopathology of previous pustular pyoderma gangrenosum episode over right tibia’s shin in August 2021: Section showing skin and subcutaneous tissue. The epidermis showed spongiosis and areas of pseudoepithelial hyperplasia. A focus shows subcorneal bullae containing proteinaceous fluid and scattered neutrophils and keratinocytes. There is dense suppurative inflammation in the dermis and deeper areas. Areas of ulceration seen. No evidence of granuloma. The above findings were suggestive of a pustular variant of PG.

Lesions healed; the patient was discharged.

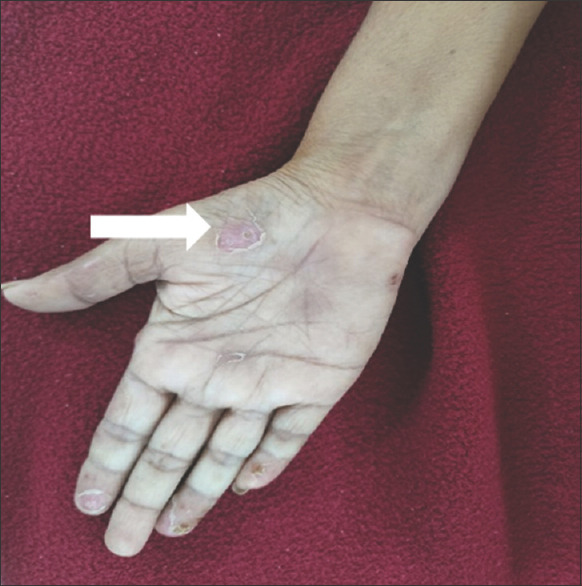

So, our patient, PLHIV, had an old history of pulmonary tuberculosis, herpes zoster infection and two episodes of PG, one at CD4 of 571 and the other at CD4 count of 723, probably triggered by a viral infection [Figures 1–5].

Figure 1.

On local examination: Blisters present over the palmar aspect of both the hands

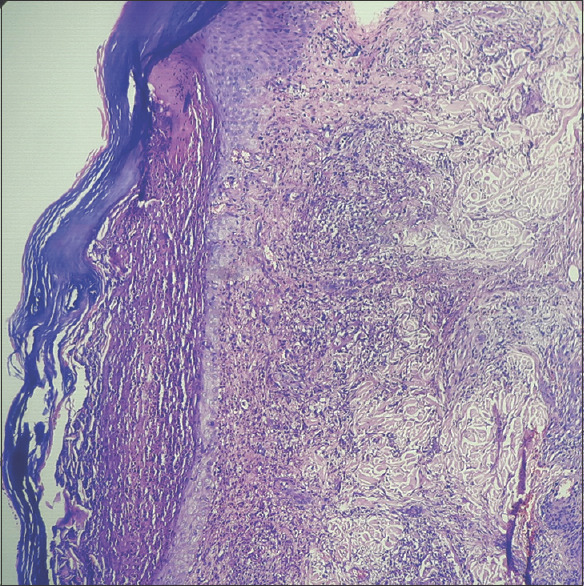

Figure 5.

H and E stain on 100x showing epidermis having hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis, and subcorneal collection of neutrophils (brown arrow). Dermis reveals mixed inflammatory infiltration around blood vessels and hair follicles. (Black arrow). Inflammation extends up to the deep dermis

Figure 2.

On local examination: Blisters present over the palmar aspect of both the hands

Figure 3.

Healed ulcer over shin of right leg suggestive of old lesion of pyoderma gangrenosum (black arrows)

Figure 4.

H and E stain showing full-thickness skin biopsy features of pustular pyoderma gangrenosum on 40x scanner (blue arrow)

Discussion

PG was seen twice during which the CD4 count was >500.

In 2003, Oakley and Brown[1] and her team working in Aukland Updated a list of Skin Manifestations of HIV in 2021. In our patient, cutaneous vasculitis and ichthyosis were considered. Viral infections namely herpes simplex virus occur more over oral and genital areas. Candidiasis was also a differential. Eosinophilic folliculitis occurs at CD4 <300, which was absent in our patient.

Brooklyn et al.[2] in 2006 described various forms of pyoderma: pustular, vegetative and bullous and according to them, they occur in patients with inflammatory bowel disease, rheumatoid arthritis and haematological malignancies. Our patient had none of these.

Rathod et al.[3] reported a 24-year-old male with Penile PG did not show a response to Acyclovir but responded to glucocorticoids and topical Imiquimod.

A French dermatologist, Louis Brocq[4], described PG as a rapidly progressive necrotic lesion. Later, it was realised that it is an auto-inflammatory condition as it recurs, causing neutrophil activation by producing cytokines. The common site was pre-tibial, seen in our patient during the first episode.

Sison[5] studied the relationship between autoimmune diseases and HAART. She reported that these patients had an increased risk of psoriasis, systemic lupus erythematosus, uveitis and Sjögren syndrome. We thought of vasculitis in our patient, but ANA was negative.

Garg and Sanke[6], in their discussion on inflammatory dermatoses in human immunodeficiency virus, have listed autoimmune bullous dermatoses as ‘less commonly’ encountered in HIV. They have listed PPE pruritic purpuric eruptions as commonly encountered in early HIV on starting ART and at low CD4 counts <300. Our patient’s lesions were non-pruritic, and CD 4 was more than 500. Vega and Espinoza[7] studied HIV infection and its effects on developing autoimmune disorders. They concluded that autoimmune diseases occur in PLHIV at various CD4 counts and that their presentation and response to treatment are the same as in the general population.

The authors have described two stages: the active ulcerative stage, representing a peripheral erythematous inflammatory halo, and the erythematous, raised necrotic edge. The second one is the wound healing stage, wherein the epithelial edges show string-like projections between the ulcer bed and normal surrounding skin – Gulliver’s sign. The healed ulcer has an atrophic cribriform scar, ‘cigarette paper-like’. This was seen in the old healed pre-tibial lesion in our patient.

Draganescu et al.[8] reported the perspectives on skin disorder diagnosis among people living with HIV. According to them, once the immune competence under HAART is restored, the obvious and frequent dermatoses in the general population manifest at similar degrees of prevalence.

Further, they separately studied the incidence of autoimmune diseases in HIV patients without exposure to HAART and after treatment with HAART. Those without prior treatment were more prone to autoimmune diseases. At the same time, patients on HAART were more prone to uveitis, psoriasis and autoimmune haemolytic anaemia. They further explained a possible molecular mimicry between viral proteins and autoantigens. Post-treatment this reduces Barry et al.,[9] from King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, report a case of PG-induced by the BNT162b2 COVID-19 vaccine. This patient developed one lesion after another within 24 hours of vaccination. The lesions did not respond to antibiotics or antivirals but later to topical steroids. COVID-19 infection has also been responsible for PG in some patients. Our patient did not have Covid 19, but possibly some other viral trigger.

Schmieder and Krishnamurthy[10] concluded their study by reporting that PG is not caused by infection or gangrene but rather associated with systemic illness.

Clinical Implications: As the CD4 count improves with appropriate antiretroviral treatment, there is an increased prevalence of autoimmune diseases in PLHIV. With early diagnosis, response to treatment is positively accomplished.

Consent

All authors have declared that ‘Written informed consent was taken from the study subject’.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

I would like to acknowledge the help extended to us by Dr Kirti Deo, Professor of the Dermatology Department and Dr Rupali Bavikar, Department of Pathology of Dr D Y Patil Medical College and Hospital, Dr DY Patil Vidyapeeth, Pimpri, Pune.

References

- 1.Oakley A, Brown M. Skin conditions relating to HIV infection. Dermnet J. 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brooklyn T, Dunnill G, Probert C. Diagnosis and treatment of pyoderma gangrenosum. BMJ. 2006;333:181–4. doi: 10.1136/bmj.333.7560.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rathod SP, Padhiar BB, Karia UK, Shah BJ. Penile pyoderma gangrenosum successfully treated with topical Imiquimod. Indian J Sex Transm Dis AIDS. 2011;32:114–7. doi: 10.4103/2589-0557.85418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gameiro A, Pereira N, Cardoso JC, Gonçalo M. Pyoderma gangrenosum: Challenges and solutions. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2015;8:285–93. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S61202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sison C. Relationship Between Autoimmune Diseases and HAART in HIV, Rheumatology advisor, September 14. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garg T, Sanke S. Inflammatory dermatoses in human immunodeficiency virus. Indian J Sex Transm Dis AIDS. 2017;38:113–20. doi: 10.4103/ijstd.IJSTD_22_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vega LE, Espinoza LR. HIV infection and its effects on the development of autoimmune disorders. Pharmacol Res. 2018;129:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2018.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Draganescu M, Baroiu L, Iancu A, Dumitru C, Radaschin D, Polea ED, et al. Perspectives on skin disorder diagnosis among people living with HIV in southeastern Romania. Exp Ther Med. 2021;21:97. doi: 10.3892/etm.2020.9529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barry M, AlRajhi A, Aljerian K. Pyoderma gangrenosum induced by BNT162b2 COVID-19 vaccine in a healthy adult. Vaccines. 2022;10:87. doi: 10.3390/vaccines10010087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schmieder SJ, Krishnamurthy K. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023. Pyoderma Gangrenosum. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]