Abstract

The numbers of Asian and Latinx adolescents are growing fast in the United States. While their ethnic/racial identity and experience of discrimination have been found to play important roles in their development, current scholarship has only begun to understand their longitudinal relationships. Moreover, most of the existing studies have examined these associations only at the between-person level. To address these gaps, the current study examined both between- and within-person longitudinal associations between ethnic/racial identity (exploration, commitment, private regard, and centrality) and discrimination over a 3-year period among a total of 241 adolescents (Asian: n = 139, Latinx: n = 102; female: 65.96%; M age = 15.27, SD = 0.66). The within-person approach using the random-intercept cross-lagged panel models explained the associations better than the between-person approach using the cross-lagged panel model. Specifically, reciprocal within-person longitudinal associations were found between discrimination and developmental dimensions of ethnic/racial identity (exploration and commitment) for Asian adolescents and content dimensions (private regard and centrality) for Latinx adolescents. These findings imply the usefulness of within-person longitudinal designs in understanding the associations between ethnic/racial identity and discrimination. Implications for potential similarities and differences in the longitudinal associations between ethnic/racial identity development and the experience of discrimination for the two groups are discussed.

Keywords: Ethnic/racial identity, Discrimination, Asian adolescents, Latinx adolescents, Within-person design

Introduction

Asian and Latinx populations are the two fastest growing ethnic/racial groups in the United States (Frey 2018; Vespa et al. 2018). The majority of the United States population growth since 2000 has occurred from the increase in the number of both foreign-born and native-born populations of these two ethnic/racial groups, and the sizes of these groups in 2015 were projected to double by 2060 (Frey 2018). Demographic shifts will be especially pronounced for those under the age of 18. The proportions of Asian and Latinx children and adolescents are predicted to increase from 5.2% to 8.1% (Asian) and 24.9% to 32.0% (Latinx) by 2060 (Vespa et al. 2018). Yet, current scholarship has only begun to understand the experiences and development of Asian and Latinx youth.

During adolescence, individuals address the developmental task of understanding who they are within the contexts of the world around them (Erikson 1968). In ethnically/racially diverse societies such as the United States, Asian and Latinx adolescents explore, learn and develop feelings and attitudes about their ethnicity/race, referred to as ethnic/racial identity. Unfortunately, for these ethnic/racial minority adolescents, the developmental processes of ethnic/racial identity formation often occur against a backdrop of experiences of ethnic/racial discrimination—a source of stress due to racial bias and prejudice (Umaña-Taylor et al. 2014; Williams et al. 2003). As salient ethnic/racial experiences during adolescence, both ethnic/racial identity development and ethnic/racial discrimination may be mutually influential (Umaña-Taylor et al. 2014; Zeiders et al. 2017) and have important implications for adolescents’ adjustment and health (Pascoe and Smart Richman 2009; Rivas-Drake et al. 2014; Swanson et al. 2003; Umaña-Taylor et al. 2009). However, less is known about how they are related longitudinally. Furthermore, most of the existing studies have examined these psychological processes in perceptions, thoughts, and emotions by making comparisons across individuals rather than assessing the changes that occur within each person. The current study attempts to address these gaps by examining both between-person and within-person longitudinal associations between ethnic/racial identity and ethnic/racial discrimination among Asian and Latinx adolescents.

Experience of Ethnic/Racial Discrimination as Asian and Latinx Adolescents

Both Asian and Latinx adolescents belong to ethnic/racial minority groups in the United States and ethnic/racial discrimination is a normative experience for both groups (Yip 2018). Many studies on ethnic/racial discrimination in the past have focused on African American children and adolescents (Pachter and Coll 2009) and the experiences of Asian and Latinx adolescents have been less represented in the literature. In fact, studies with more Asian and Latinx adolescents, compared to African American adolescents found stronger negative influence of ethnic/racial discrimination on developmental outcomes, such as socio-emotional distress, academics, and risky health behaviors (Benner et al. 2018). While ethnic/racial discrimination could exert adverse effects on both Asian and Latinx adolescents and both groups are often viewed as perpetual foreigners, the two groups may experience ethnic/racial discrimination in different ways (Fisher et al. 2000; Greene et al. 2006; Huynh and Fuligni 2010) due to distinct stereotypes associated with each group. Asians have been viewed with an image of a “model minority,” described as quiet, hardworking, smart, unsociable, shy, less popular, and stoic (Katz and Braly 1933; Thompson and Kiang 2010). Asian immigrants have also been labeled as “fresh off the boat (also known as the FOB),” a term that has emerged on the notion of American supremacy, which derides those who are less acculturated to the American culture as being less sophisticated. Although some of the descriptions seem positive, these stereotypes have been found to arouse mixed feelings, and even generate negative consequences among Asians (Lin et al. 2005; Thompson and Kiang 2010). Individuals from Latinx background are often viewed as illegal immigrants who contribute to depressing wages and increasing public social service costs (Kao 2000). Negative adjectives such as unintelligent, violent and antisocial have been associated with this group, especially for Latinx males (Cowan et al. 1997; Niemann et al. 1998). Both Asian and Latinx adolescents in the United States grow up in an environment where stereotypes about their ethnic/racial groups exist. Yet, each group’s stereotype involves different types of treatments and expectations from the larger society.

Due to these reasons, unique patterns may be observed in the longitudinal associations between ethnic/racial identity and ethnic/racial discrimination for Asian versus Latinx adolescents. A recent meta-analytic study found the buffering effect of ethnic/racial identity to be stronger for Latinx adolescents than Asian adolescents in the association between ethnic/racial discrimination and developmental outcomes of mental health (e.g., depressive symptoms, anxiety and distress, self-esteem, life satisfaction, social connectedness/competence), academic and cognition (e.g., academic motivation, academic achievement, perception of school climate and satisfaction), risky health behaviors (e.g., delinquency, substance use), and physical health (e.g., sickness, sleep disturbance, inflammatory biomarkers) (Yip et al. 2019). Yet, it is still unclear if longitudinal relationships between ethnic/racial identity and ethnic/racial discrimination are different for Asian and Latinx youth. In this study, attempts are made to elucidate the direct longitudinal associations between ethnic/racial identity and ethnic/racial discrimination for Asian and Latinx adolescents who may encounter different sets of stereotypes in the United States society.

Multiple Dimensions of Ethnic/Racial Identity and Ethnic/Racial Discrimination

Ethnic/racial minority adolescents in ethnically/racially diverse societies become increasingly aware of their ethnicity/race (Fuhrmann et al. 2015) and develop ethnic/racial identity through the process of “reflection and observation” (Erikson 1968). Ethnic/racial identity is an aspect of self-concept that is related to one’s ethnic/racial group membership, and it is comprised of multiple dimensions. These dimensions include developmental processes (i.e., exploration and commitment; Phinney 1993), as well as the meaning (e.g., private regard; Sellers et al. 1997) and significance (e.g., centrality) of one’s ethnicity/race, which represent the content of ethnic/racial identity. Both developmental and content dimensions come together to form a synergistic and integrated ethnic/racial identity, and uniquely and cooperatively contribute to forming a coherent sense of self. In this study, the joint associations between developmental and content dimensions of ethnic/racial identity and ethnic/racial discrimination are considered.

The developmental dimension of ethnic/racial identity involves the processes of exploration and commitment (Phinney and Ong 2007)—concepts introduced by Marcia (1980) as part of theories about ego identity broadly. Exploration characterizes the state of trying out, looking for information, and learning about one’s ethnic/racial group. For instance, participating in cultural events and talking to people about one’s ethnicity/race are part of ethnic/racial exploration. Commitment characterizes the degree of attachment and investment to one’s ethnic/racial group. Examples include having a clear sense of one’s ethnic/racial background and what it means to them (Roberts et al. 1999). While exploration and commitment are often positively correlated (Phinney and Ong 2007), they play different roles in adolescents’ development (Torres et al. 2011). Exploration may increase the psychological distress of ethnic/racial discrimination (Phinney and Ong 2007), while commitment was observed to buffer the negative mental health effects of ethnic/racial discrimination among Latinx adults (Torres et al. 2011).

Yet, another approach to the study of ethnic/racial identity focuses on its content, including the meaning and significance. The meaning of ethnic/racial membership includes the beliefs and evaluative attitudes about one’s ethnic/racial group (Sellers et al. 1997). In this approach, private regard refers to personal feelings and attitudes about one’s own ethnic/racial group. Ethnic/racial identity private regard is distinguished from developmental ethnic/racial identity approaches, because positivity about one’s ethnic/racial group may vary, irrespective of how much an individual has explored or made commitments to one’s ethnic/racial group. As for significance of ethnic/racial identity, centrality refers to the degree to which one defines his or her self-concept to include ethnicity/race. High levels of centrality indicate high levels of significance one places on ethnic/racial group membership among multiple domains of self-concept (Sellers et al. 1997).

There is emerging research aiming to integrate both dimensions to arrive at a more comprehensive assessment of ethnic/racial identity (Yip 2014), but previous studies on the associations between ethnic/racial identity and ethnic/racial discrimination have focused on understanding either the developmental processes or the content dimension of ethnic/racial identity and the results have been mixed (Gonzales-Backen et al. 2018; Seaton et al. 2009; Zeiders et al. 2017). Although research on ethnic/racial identity was moved towards integrating the developmental and content approaches, it is yet unclear how they operate in tandem with respect to ethnic/racial discrimination.

Furthermore, while ethnic/racial identity development and ethnic/racial discrimination experiences are internal psychological processes involving one’s perceptions, thoughts, and emotions, existing studies have been conducted mostly at the between-person level, where comparisons were made across individuals. Taking note of this quality, recent studies (Gozales-Backen et al. 2018; Zeiders et al. 2017) have begun to examine and find some evidence for how the two may be related to one another at the within-person level. In other words, these studies point to the importance of addressing the changes in an individual’s ethnic/racial identity in relation to corresponding changes in ethnic/racial discrimination. In an effort to extend this line of research, the current study investigates both between- and within-person longitudinal associations between developmental and content dimensions of ethnic/racial identity and discrimination among Asian and Latinx adolescents.

Directionality of Longitudinal Associations between Ethnic/Racial Identity and Ethnic/Racial Discrimination: Theoretical Framework

In the quest to unpack the association between ethnic/racial identity and ethnic/racial discrimination, scholars have theorized three possible directions: (1) ethnic/racial identity as a predictor of ethnic/racial discrimination, (2) ethnic/racial discrimination as a predictor of ethnic/racial identity, and (3) reciprocal associations. The theories that support respective direction are identification-attribution model, social identity theory, and phenomenological variant of ecological systems theory (PVEST), which are reviewed in this section.

Ethnic/racial identity as a predictor of ethnic/racial discrimination: identification-attribution model

Some scholars have suggested that a strong identification with one’s ethnic/racial group predicts increased ethnic/racial discrimination experiences. For example, the identification-attribution model (Gonzales-Backen et al. 2018) assumes that high levels of ethnic/racial identity increase the awareness of ethnic/racial discrimination experiences due to the increased levels of understanding about one’s ethnic/racial group membership. In cross-sectional studies with African American adolescents and young adults, those who placed more significance on their ethnicity/race (i.e., higher levels of ethnic/racial identity centrality) tended to perceive higher levels of ethnic/racial discrimination (Scott 2004) and those who reported higher composite scores of ethnic/racial identity reported higher levels of ethnic/racial discrimination (Hall and Carter 2006). Sellers and Shelton (2003) also found that higher levels of ethnic/racial identity centrality were associated with higher levels of ethnic/racial discrimination the following year for African American college students.

Fewer studies have focused on Asian and Latinx adolescents. Hou et al. (2015) found that higher levels of positive ethnic/racial affect predicted lower levels of ethnic/racial discrimination among 7th or 8th grade Chinese American adolescents in metropolitan areas of Northern California. This is contrary to the identification-attribution model, possibly due to the effect of model minority stereotype, which includes positive qualities of being identified as Asians. It is also possible that the internal within-person processes of stronger identification and increased awareness of discrimination were not captured when these associations were tested at the between-person level. Evidently, the dearth of studies in the current state of scholarship calls for further investigation into both between-and within-person associations between ethnic/racial identity and discrimination among Asian population.

For Latinx adolescents, a recent study examined within-person longitudinal associations and found higher levels of ethnic/racial identity exploration to predict higher levels of ethnic/racial discrimination, while higher levels of ethnic/racial identity commitment predicted lower levels of ethnic/racial discrimination among immigrant adolescents in Miami and Los Angeles who had lived in the United States for five or less years in the first year of the study (Gonzales-Backen et al. 2018). In Zeiders et al. (2017), none of the developmental dimensions of ethnic/racial identity predicted ethnic/racial discrimination for United States-born Mexican-origin adolescent mothers. Taken together, this research suggests the need for additional research to clarify both between- and within-person associations of ethnic/racial identity and discrimination experience for the Latinx adolescents, with a specific focus on distinguishing multiple dimensions of ethnic/racial identity.

Ethnic/racial discrimination as a predictor of ethnic/racial identity: social identity theory

Social identity theory (Tajfel 1981) suggests that ethnic/racial discrimination motivates adolescents’ ethnicity/race to become salient; the heightened salience, in turn, with efforts to identify with positively-viewed social groups to maintain positive self-esteem, stimulates the development of ethnic/racial identity (Branscombe et al. 1999). For example, ethnic/racial discrimination may stimulate an adolescent to find positive qualities about their ethnic/racial heritage or develop positive feelings about their ethnic/racial group membership in order to protect their self-esteem against the negative impact of ethnic/racial discrimination. On the other hand, this theory also suggests that due to the desire to identify with a positively-viewed social group, adolescents may reduce the identification with their ethnic/racial group as a coping strategy since their ethnic/racial group is not viewed positively from the larger society.

In a 4-year longitudinal study of Latinx adolescents in Midwestern United States, ethnic/racial discrimination measured at Year 2 was associated with the mean level of ethnic/racial identity exploration and affirmation measured by Ethnic Identity Scale (EIS; Umaña-Taylor et al. 2014) across Years 2 to 4 (Umaña-Taylor et al. 2009; Umaña-Taylor and Guimond 2012). Adolescents who reported higher levels of ethnic/racial discrimination reported increased levels of ethnic/racial identity exploration, suggesting that ethnic/racial discrimination may stimulate identity crisis and increase adolescents’ awareness and curiosity about their ethnic/racial group membership. On the other hand, heightened levels of ethnic/racial discrimination lowered the levels of ethnic/racial identity affirmation, a similar concept to ethnic/racial identity commitment, likely a coping strategy to maintain a positive social identity by decreasing attachment to one’s negatively-viewed group. When longitudinal associations were tested among Mexican-origin adolescent mothers (average age of 16.83 years) in a 6-year longitudinal study (Zeiders et al. 2017), within-person increases in ethnic/racial discrimination did not predict changes in ethnic/racial identity exploration but predicted decreases in ethnic/racial identity resolution and affirmation one year later. At the between-person level, higher levels of ethnic/racial discrimination predicted lower levels of ethnic/racial identity affirmation, but not ethnic/racial identity exploration. Another cross-sectional study on Latinx youths (average age of 12.2 years) found higher levels of ethnic/racial discrimination experience to be associated with higher levels of ethnic/racial identity commitment (Baldwin-White et al. 2017).

Seaton et al. (2009) explored the longitudinal associations between ethnic/racial discrimination and ethnic/racial identity meaning and significance. Increased levels of ethnic/racial discrimination among 14–18 year-old African American adolescents predicted lower levels of ethnic/racial identity private regard the following year. Adolescents’ private regard was consistent with the negative experience of ethnic/racial discrimination. However, the significance of ethnicity/race as measured by ethnic/racial identity centrality, was not associated with ethnic/racial discrimination. Among international college students, Ramos et al. (2012) observed that higher levels of ethnic/racial discrimination predicted higher levels of ethnic/racial identity centrality, but not other ethnic/racial identity dimensions (i.e., ingroup ties, ingroup affect) one year later.

Again, the results in these few studies are mixed and suggest that the experience of discrimination may be differentially associated with different dimensions of ethnic/racial identity for adolescents from different ethnic/racial backgrounds. Furthermore, when and for whom the associations between ethnic/racial discrimination and ethnic/racial identity would be positive or negative also requires further investigation.

Reciprocal associations: phenomenological variant of ecological systems theory (PVEST)

In addition to unidirectional associations, there is theoretical support for bidirectional associations between ethnic/racial identity and ethnic/racial discrimination. For example, the ecological systems theory posits a reciprocal relationship—development as a product of interaction between individual and the surrounding environment (Bronfenbrenner 1992). Building off of ecological systems theory, PVEST suggests that adolescents’ ethnic/racial identity development occurs interactively within the context of ethnic/racial discrimination (Spencer et al. 2003). From this perspective, adolescents’ understanding of who they are in relation to their ethnicity/race is both a response to ethnic/racial discrimination and a lens through which discrimination is experienced in their everyday contexts. As well, in their model of ethnic/racial minority child development, Coll et al. (1996) and Yip (2018) have discussed how the development of ethnic/racial identity and the perception of ethnic/racial discrimination may be interrelated and influence one another as both experiences tend to be enhanced during adolescence. Building off of these perspectives, scholars have empirically tested these theorized associations (Baldwin-White et al. 2017; Pahl and Way 2006; Romero and Roberts 2003; Umaña-Taylor and Guimond 2012). While a mutual relationship between ethnic/racial identity and ethnic/racial discrimination is theoretically hypothesized, as reviewed earlier, there is research that observes ethnic/racial identity to predict ethnic/racial discrimination, such that ethnic/racial identity may reduce or enhance the experiences of ethnic/racial discrimination (Gonzales-Backen et al. 2018; Scott 2004), and corresponding research in which ethnic/racial discrimination diminishes or stimulates adolescents’ ethnic/racial identity development (Seaton et al. 2009; Zeiders et al. 2017). This study seeks to contribute integration to the literature by investigating the synergistic and bidirectional associations between various dimensions of ethnic/racial identity and ethnic/racial discrimination.

Current Study

Drawing upon the theoretical frameworks of the identification-attribution model, social identity theory, and PVEST, the current study examined the longitudinal associations between ethnic/racial identity dimensions and ethnic/racial discrimination over 3 years for Asian and Latinx adolescents. Based on these theories, bidirectional associations were hypothesized both at the between- and within-person levels. As related theories suggest internal psychological processes in the associations between ethnic/racial identity development and ethnic/racial discrimination experience, a within-person approach was expected to explain their associations better than a between-person approach. Specifically, higher levels of ethnic/racial identity were expected to heighten intrapersonal levels of discrimination experience in the following year. In turn, higher levels of ethnic/racial discrimination experience were expected to predict changes in the following year’s level of ethnic/racial identity within the same person. However, whether the changes would be positive or negative was a subject to exploration. Due to lack of empirical studies, specific hypotheses for different dimensions of ethnic/racial identity for Asian and Latinx adolescents remain open although different patterns are expected for the two ethnic/racial groups.

Method

Participants

From an original sample of 405 adolescents in a 3-year longitudinal study conducted at five public high schools in New York City, the current study selected all of Asian (n = 139) and Latinx (n = 102) adolescents. After excluding the adolescents from other ethnic/racial groups (e.g., African American, White, other), the total analytic sample of the current study included 241 adolescents (Asian n = 139, Asian female n = 69.06%; Latinx n = 102, Latinx female n = 61.76%). Data collected in the fall of each year starting from 9th grade to 11th grade (65.96% female) were used. A total of 108 adolescents (Asian n = 69; Latinx n = 39) remained throughout all three years (retention rate: Table 1). No significant differences were found in the first year means of ethnic/racial identity and ethnic/racial discrimination among those who participated in all three years, two years, and one year. The missing data were treated with Full Information Maximum Likelihood (FIML) estimation. Most of the adolescents (79.25%) were born in the United States. The foreign-born adolescents were from countries (n = 49) such as Argentina (n = 1), Bangladesh (n = 3), Bolivia (n = 1), Brazil (n = 2), China (n = 22), Colombia (n = 3), Dominican Republic (n = 1), Ecuador (n = 3), Hong Kong (n = 1), Indonesia (n = 2), Korea (n = 1), Malaysia (n = 1), Mexico (n = 2), Peru (n = 1), Philippines (n = 2), Puerto Rico (n = 1), Singapore (n = 1) and one participant did not indicate their country of origin. The mean age was 15.27 years (SD = 0.66).

Table 1.

Attrition and Cronbach’s alpha for ERI variables for all study sample, by gender, ethnicity/race, and study year with descriptive statistics

| Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | Exploration (6 items) | Commitment (8 items) | Private regard (5 items) | Centrality (6 items) | N (%) | Exploration (6 items) | Commitment (8 items) | Private regard (5 items) | Centrality (6 items) | N (%) | Exploration (6 items) | Commitment (8 items) | Private regard (5 items) | Centrality (6 items) | |

| Overall | 241 (100) | 0.69 | 0.85 | 0.68 | 0.68 | 193 (100) | 0.68 | 0.81 | 0.77 | 0.79 | 108 (100) | 0.75 | 0.90 | 0.78 | 0.85 |

| Gender | |||||||||||||||

| Male | 82 (34.02) | 0.74 | 0.80 | 0.72 | 0.71 | 63 (32.64) | 0.67 | 0.81 | 0.80 | 0.75 | 39 (36.11) | 0.70 | 0.87 | 0.86 | 0.79 |

| Female | 159 (65.96) | 0.65 | 0.87 | 0.67 | 0.66 | 130 (67.36) | 0.68 | 0.82 | 0.77 | 0.81 | 69 (63.89) | 0.77 | 0.91 | 0.72 | 0.86 |

| Ethnicity/Race | |||||||||||||||

| Latinx | 102 (42.32) | 0.57 | 0.87 | 0.66 | 0.56 | 80 (41.45) | 0.64 | 0.83 | 0.80 | 0.76 | 39 (36.11) | 0.76 | 0.86 | 0.73 | 0.82 |

| Asian | 139 (57.68) | 0.74 | 0.83 | 0.70 | 0.75 | 113 (58.55) | 0.70 | 0.79 | 0.75 | 0.79 | 69 (63.89) | 0.75 | 0.91 | 0.81 | 0.86 |

| Descriptive statistics | |||||||||||||||

| ERD | Exploration | Commitment | Private regard | Centrality | ERD | Exploration | Commitment | Private regard | Centrality | ERD | Exploration | Commitment | Private regard | Centrality | |

| Total mean (SD) | 3.81 (4.30) | 3.18 (0.48) | 3.50 (0.47) | 4.18 (0.96) | 4.08 (1.09) | 3.60 (4.46) | 3.20 (0.48) | 3.41 (0.44) | 4.13 (0.98) | 3.88 (1.04) | 3.35 (4.20) | 3.25 (0.47) | 3.42 (0.52) | 4.32 (0.99) | 3.99 (1.06) |

| Latinx | 3.92 (4.22) | 3.08 (0.43)* | 3.48 (0.53) | 3.97 (0.98)* | 3.98 (1.22) | 3.41 (4.56) | 3.14 (0.52) | 3.45 (0.49) | 4.01 (1.06) | 3.81 (1.11) | 3.79 (4.52) | 3.26 (0.52) | 3.54 (0.48) | 4.33 (1.03) | 3.84 (1.00) |

| Asian | 3.73 (4.37) | 3.25 (0.50)* | 3.51 (0.42) | 4.34 (0.92)* | 4.15 (0.98) | 3.73 (4.40) | 3.23 (0.45) | 3.39 (0.40) | 4.22 (0.91) | 3.93 (0.99) | 3.11 (4.03) | 3.25 (0.44) | 3.35 (0.53) | 4.32 (0.97) | 4.08 (1.09) |

Asterisk indicates significant ethnic/racial group mean differences within the same year at p < 0.01 based on t test

Procedure

The data come from a larger longitudinal study focused on ethnic/racial identity and outcomes conducted in five ethnically/racially diverse schools in New York City at six time-points in the fall and spring of each year over three years. The schools’ diversity indices (Simpson 1949) ranged from 0.55 to 0.74 (0 = no diversity, 1 = high diversity). The Simpson’s index is interpreted such that the resultant probability is equivalent to randomly choosing two students from different ethnic/racial groups in each school. All participating schools had diversity scores that surpassed the average level of diversity among New York State public schools (0.37) and national public schools (0.32) (Public School Review 2018).

Participants were recruited in the fall of 2008 (Cohort 1: 61.23%) and in the fall of 2009 (Cohort 2: 38.77%). Recruitment occurred at the school level in order to ensure representation of diverse school settings. Once participating schools were identified, parental consent and adolescent assent forms were sent home to all 9th graders. For the students who completed and submitted consent and assent forms, researchers visited each school and administered surveys about their demographic information as well as social, emotional and cognitive experiences, including ethnicity/race-related experiences in groups ranging from 10 to 30 students. Participants completed the survey in the fall and spring of each year. Whereas data was collected at six time-points, ethnic/racial discrimination was only administered during the fall of each year; therefore, the current study uses data from the three fall time-points to examine annual associations and changes over time.

Measures

Ethnic/racial discrimination

Ethnic/racial discrimination was measured with Harrell (2000)’s Daily Life Experiences (DLE). Across 18 situations of ethnic/racial discrimination (e.g., “How often has it happened because of your race: Been ignored, overlooked, or not given service,” “How much did it bother you: Being accused of something or treated suspiciously.”), participants responded to the frequency of experience on a 6-point Likert scale from 0 = “never” to 5 = “once a week”, along with how much each incident bothered them on a 6-point Likert scale from 0 = “has never happened to me” to 5 = “bothered me extremely.” A composite score was calculated by taking the mean of the product of frequency (0–5) and bothered scores (0–5), which ranged from 0 (0*0) to 25 (5*5). This measure with this scoring system has been reliably used in a number of studies (e.g., Seaton et al. 2009; Yip et al. 2008). The mean frequency ranged from 1.18 to 1.25 (standard deviations ranging from 1.01 to 1.09; maximum values ranged from 4.53 to 4.61) across the three years. The mean bothered-ness ranged from 1.46 to 1.55 (standard deviations ranged from 1.27 to 1.34; maximum values ranged from 4.89 to 5). The mean of the product of frequency and bothered-ness ranged from 3.35 to 3.81 (standard deviations ranged from 4.20 to 4.30, maximum values ranged from 21.11 to 22.29). Approximately 11.62% (n = 28) during the first year, 14.11% (n = 34) during the second year, and 11.62% (n = 28) during the third year reported a mean score of 0. The skewness values ranged from 1.61 to 1.69 with standard errors ranging from 0.16 to 0.23 across three years, while the kurtosis values ranged from 2.56 to 3.65 with standard errors ranging from 0.32 to 0.46, indicating the data is skewed to the right due to relatively high number of 0 values but still in the acceptable range (West et al. 1995).

Ethnic/racial identity exploration and commitment

The development of ethnic/racial identity was measured by 12-item Multigroup Ethnic Identity Measure (MEIM; Phinney 1992). On a 4-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 4 = strongly agree), participants were asked about how much they agreed with statements regarding their ethnic/racial identity exploration (6 items) and commitment (8 items). The scale included items such as “I have spent time trying to find out more about my own ethnic group, such as history, traditions, and customs” for exploration, and “I have a clear sense of my ethnic background and what it means for me” for commitment. For Latinx adolescents, the internal reliability ranged from α = 0.57–0.76 for exploration and α = 0.64–0.87 for commitment. For Asian adolescents, the internal reliability ranged from α = 0.70–0.75 for exploration and α = 0.79–0.91 for commitment. The Cronbach’s alphas for the entire sample and by gender and ethnicity/race are presented in Table 1.

Ethnic/racial private regard and centrality

The content (i.e., meaning and significance) dimension of ethnic/racial identity were measured by an abridged version of Multidimensional Inventory of Black Identity (MIBI; Sellers et al. 1997) by replacing “Black” with “my ethnic/racial group (Fuligni et al. 2005).” Using this measure, this study focused on private regard and centrality. Based on factor analyses (Cham et al. (in preparation)), 5 most reliable items were selected from the original 7 items for private regard and 6 items from the original 8 items for centrality. Private regard included items such as, “I feel good about people from my ethnic/racial group,” and centrality included items such as “In general, my ethnicity/race is an important part of my self-image.” Each statement was measured on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). For Latinx adolescents the internal reliability ranged from α = 0.66–0.80 for private regard and α = 0.56–0.82 for centrality. For Asian adolescents, the internal reliability ranged from α = 0.70–0.81 for private regard and α = 0.75–0.86 for centrality. The Cronbach’s alphas for the entire sample and by gender and ethnicity/race are presented in Table 1.

Covariates

Due to research which has found effects of age, nativity, gender for ethnic/racial identity and ethnic/racial discrimination (Douglass and Umaña-Taylor 2016; Geronimus et al. 2006; Kessler et al. 1999; Kuo 1995; Rumbaut 1994) these sociodemographic variables were controlled for in all of the paths, accounting for any individual differences by these characteristics. Age was calculated with date of birth in years. For nativity, United States-born was coded 1, and foreign-born was coded 0. For gender, male was coded 1and female was coded 0.

Analytic Approach

To examine the longitudinal relationships between ethnic/racial discrimination and multiple ethnic/racial identity dimensions, structural equation models (SEM) using cross-lagged panel models (CLPM) and random-intercepts cross-lagged panel models (RI-CLPM; Hamaker et al. 2015) were estimated in Mplus 7.31 (Muthén and Muthén 1998–2012). Traditionally, cross-lagged panel models (CLPM) are used to assess between-person associations between the same variables over time (i.e., autoregressive path) and between one variable at one time-point and another variable at another time-point (i.e., cross-lagged path) (Hamaker et al. 2015).

The RI-CLPM was recently introduced as a method that enables the decomposition of observed variance into between-person time-invariant factors and within-person time-varying factors. In other words, this method is able to tease out the within-person effects from the between-person effects (Hamaker et al. 2015). This approach focuses on within-person changes from one’s own mean by adopting the method of group mean-centering. Centering at the group-mean results in the difference between one’s response at a time-point and one’s own mean across all time-points. This way, it becomes possible to observe whether an increase or a decrease in ethnic/racial discrimination from one’s own (within-person) mean was associated with an increase or a decrease in ethnic/racial identity from one’s own (within-person) mean. As such, the within-person analyses explore how changes in ethnic/racial identity (or ethnic/racial discrimination) precede subsequent changes in ethnic/racial discrimination (or ethnic/racial identity).

Similar to CLPM, the RI-CLPM also consists of autoregressive and cross-lagged paths, but this model assesses the paths at the within-person level. Since each person’s report at one time-point is likely to be a continued representation of the same person measured at a previous time point, within-person variations may have a carryover effect from one time-point to the next. Therefore, in order to take this effect into account, the within-person variable at each time-point is regressed on the same variable at a previous time-point, which is referred to as an autoregressive path (e.g., ethnic/racial discrimination at Year 1 and ethnic/racial discrimination at Year 2). The cross-lagged paths in RI-CLPM examine the associations between within-person variations in a variable at one time-point and another variable at the next time-point (e.g., ethnic/racial discrimination at Year 1 and ethnic/racial identity exploration at Year 2). This model is recommended for analyzing reciprocal within-person associations for its ability to prevent biased cross-lagged estimates that result from possible between-person effects (Hamaker et al. 2015).

Simultaneously, all factor loadings for observed variables and random intercepts were fixed at 1 to account for the stable between-person effects. For selecting the model that most suitably and parsimoniously captures the associations, the fit indices of constrained versus unconstrained models as well as traditional CLPM versus RI-CLPM were compared. The constrained model is more parsimonious than the unconstrained model and assumes equal autoregressive and cross-lagged paths from one time-point to the next time-point, which increases the precision of estimates. The constrained model was selected over the unconstrained model if the constraints did not significantly worsen the model fit, according to the preference for parsimony.

The present study’s analytic procedure involved 4 steps. First, the between-person associations between ethnic/racial identity dimensions (i.e., ethnic/racial identity exploration, commitment, private regard, and centrality) and ethnic/racial discrimination for Asian adolescents using CLPM were examined, followed by the examination of their within-person associations using RI-CLPM. Next, the between-person association between ethnic/racial identity dimensions (i.e., ethnic/racial identity exploration, commitment, private regard, and centrality) and ethnic/racial discrimination for Latinx adolescents using CLPM were examined, again, followed by the examination of their within-person associations using RI-CLPM. These associations were assessed with separate statistical models for Asian and Latinx adolescents considering possible effects of age, gender, and nativity.

Results

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for each year by ethnicity/race. For the entire sample, the mean of ethnic/racial discrimination across three years ranged from 3.35 (SD = 4.20) to 3.81 (SD = 4.30) out of the highest possible score 25. The mean of ethnic/racial identity exploration across three years ranged from 3.18 (SD = 0.48) to 3.25 (SD = 0.47) out of 4, and the mean of ethnic/racial identity commitment ranged from 3.41 (SD = 0.52) to 3.50 (0.47) out of 4. For ethnic/racial identity private regard, the mean score ranged from 4.13 (SD = 0.98) to 4.32 (SD = 0.99) out of 7, while ethnic/racial identity centrality’s mean ranged from 3.88 (SD = 1.04) to 4.08 (SD = 1.09) out of 7. Significant differences were observed for the mean scores of Year 1 ethnic/racial identity exploration between Asian (M = 3.24, SD = 0.50, p < 0.01) and Latinx (M = 3.08, SD = 0.43, p < 0.01) adolescents and Year 1 ethnic/racial identity private regard between Asian (M = 4.34, SD = 0.92, p < 0.01) and Latinx (M = 3.97, SD = 0.98, p < 0.01) adolescents. In both cases, Asian adolescents scored higher than Latinx.

Table 2 presents bivariate correlations of study variables. Year 1 ethnic/racial discrimination was correlated with Year 2 and Year 3 ethnic/racial discrimination suggesting stability over time. Year 1 ethnic/racial discrimination was positively associated with Year 1 and 2 ethnic/racial identity exploration, commitment and private regard, and Year 1 ethnic/racial identity centrality. Age was negatively correlated with Year 3 ethnic/racial discrimination. All of the ethnic/racial identity measures (i.e., exploration, commitment, private regard, and centrality) across 3 years were significantly positively correlated with one another.

Table 2.

Correlations between study variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Year 1 Age | – | ||||||||||||||||

| 2. Nativity | −0.15* | – | |||||||||||||||

| 3. Gender | 0.22** | −0.05 | – | ||||||||||||||

| 4. Year 1 discrimination | −0.03 | 0.05 | −0.16* | – | |||||||||||||

| 5. Year 2 discrimination | −0.08 | 0.02 | −0.04 | 0.48** | – | ||||||||||||

| 6. Year 3 discrimination | −0.28** | 0.17 | −0.12 | 0.53** | 0.57** | – | |||||||||||

| 7. Year 1 exploration | −0.08 | −0.03 | −0.07 | 0.16* | 0.12 | 0.04 | – | ||||||||||

| 8. Year 2 exploration | 0.00 | −0.08 | −0.09 | 0.22** | 0.25** | 0.12 | 0.53** | – | |||||||||

| 9. Year 3 exploration | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.08 | 0.05 | 0.17 | −0.06 | 0.54** | 0.49** | – | ||||||||

| 10. Year 1 commitment | 0.01 | −0.07 | −0.05 | 0.15* | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.56** | 0.40** | 0.44** | – | |||||||

| 11. Year 2 commitment | −0.01 | 0.00 | −0.07 | 0.20** | 0.19** | 0.15 | 0.42** | 0.58** | 0.39** | 0.55** | – | ||||||

| 12. Year 3 commitment | 0.08 | −0.06 | 0.03 | −0.08 | 0.06 | −0.16 | 0.50** | 0.41** | 0.69** | 0.49** | 0.51** | – | |||||

| 13. Year 1 private regard | −0.09 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.18** | 0.16* | 0.19* | 0.45** | 0.35** | 0.32** | 0.59** | 0.41** | 0.31** | – | ||||

| 14. Year 2 private regard | −0.01 | 0.05 | −0.06 | 0.16* | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.31** | 0.35** | 0.24* | 0.45** | 0.49** | 0.32** | 0.55** | – | |||

| 15. Year 3 private regard | 0.04 | −0.01 | 0.09 | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.13 | 0.30** | 0.39** | 0.36** | 0.50** | 0.52** | 0.54** | 0.55** | 0.53** | – | ||

| 16. Year 1 centrality | −0.12 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.18** | 0.09 | 0.12 | 0.45** | 0.35** | 0.34** | 0.54** | 0.42** | 0.34** | 0.65** | 0.38** | 0.43** | – | |

| 17. Year 2 centrality | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.10 | 0.19 | 0.34** | 0.35** | 0.31** | 0.38** | 0.52** | 0.37** | 0.40** | 0.59** | 0.41** | 0.41** | – |

| 18. Year 3 centrality | −0.02 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.19 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.38** | 0.38** | 0.32** | 0.35** | 0.38** | 0.41** | 0.35** | 0.34** | 0.50** | 0.39** | 0.59** |

Nativity: 0 = foreign born, 1 = US born; Gender: 0 = female, 1 = male

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01;

p < 0.001

The fit of SEM models was assessed by indices such as the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), Comparative Fit Indices (CFI), Tucker Lewis Index (TLI), Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) values and change in χ2 value. Acceptable fit was considered to have RMSEA values less than or equal to 0.08, CFI and TLI values near 0.95, SRMR less than 0.08 (Hooper et al. 2008; Kline 2005).

For the between-person analysis of Asian sample, unconstrained CLPM was conducted, where all of the autoregressive and cross-lagged paths were freely estimated. The model did not fit the data very well (RMSEA = 0.10, 90% CI [0.08, 0.12], CFI = 0.74, TLI = 0.61, SRMR = 0.14). Then, a more parsimonious model, constrained CLPM, which assumes stable autoregressive and cross-lagged coefficients and applies equal constraints for these paths, was conducted but still demonstrated a relatively poor fit (RMSEA = 0.10, 90% CI [0.08, 0.11], CFI = 0.72, TLI = 0.65, SRMR = 0.14). In this model, stability paths for ethnic/racial discrimination (b = 0.43, SE = 0.06, p < 0.001), ethnic/racial identity exploration (b = 0.38, SE = 0.06, p < 0.001), commitment (b = 0.46, SE = 0.06, p < 0.001), private regard (b = 0.54, SE = 0.06, p < 0.001), and centrality (b = 0.45, SE = 0.07, p < 0.001) were all significant. However, none of the cross-lagged paths were significant.

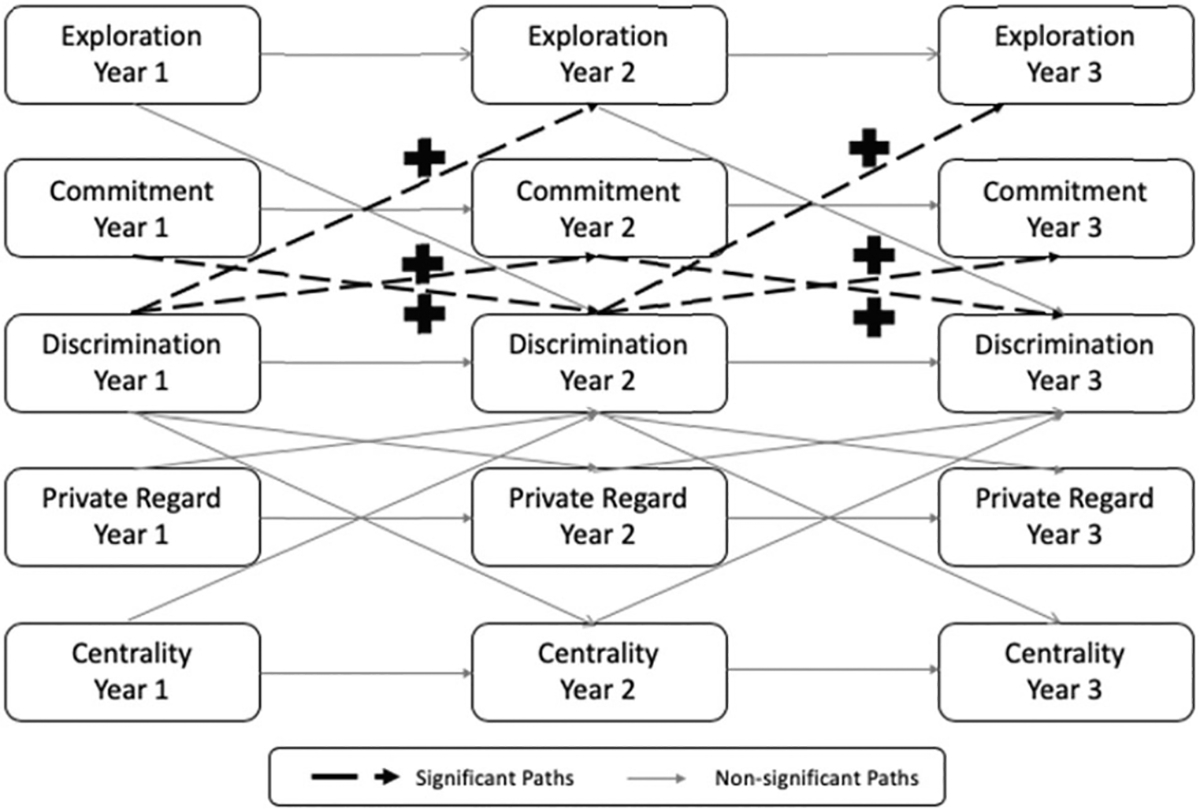

For the within-person analysis of Asian sample, first, unconstrained RI-CLPM was conducted (Fig. 1). This model displayed an acceptable fit (RMSEA = 0.05, 90% CI [0.02, 0.08], CFI = 0.97, TLI = 0.91, SRMR = 0.06). However, a more parsimonious constrained RI-CLPM, which assumes stable autoregressive and cross-lagged coefficients and applies equal constraints for these paths, also had a good fit (RMSEA = 0.05, 90% CI [0.02, 0.07], CFI = 0.95, TLI = 0.91, SRMR = 0.07). The equality constraints for these paths did not significantly worsen the fit (Δχ2(28) = 37.55, critical value = 41.34 at p = 0.05), and for the pursuit of parsimony the constrained model was selected over the unconstrained model.

Fig. 1.

Main results from RI-CLPM examining longitudinal associations between ethnic/racial identity and ethnic/racial discrimination among Asian adolescents

The poor fit of CLPM highlights the needs for separating the between-person effects and examining the within-person effects in the relationship between ethnic/racial discrimination and ethnic/racial identity. Therefore, it was deemed reasonable to select the constrained RI-CLPM as the final result. The constrained RI-CLPM demonstrates within-person paths from previous year’s ethnic/racial identity commitment to following year’s ethnic/racial discrimination (b = 4.29, SE = 1.43, p < 0.01), from previous year’s ethnic/racial discrimination to following year’s ethnic/racial identity exploration (b = 0.02, SE = 0.01, p < 0.01) and ethnic/racial identity commitment (b = 0.04, SE = 0.01, p < 0.01) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Path estimates for constrained RI-CLPM (within-person) of discrimination, exploration and commitment, private regard, and centrality for Asian and Latinx adolescents

| Y | X | Asian RI-CLPM (within person) | Latinx RI-CLPM (within person) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Discrimination (year +1) | Discrimination (year) | −0.08 (0.12) | 0.17 (0.19) |

| Exploration (year) | −0.45 (1.13) | −1.62 (1.49) | |

| Commitment (year) | 4.29 (1.43)** | 2.77 (1.80) | |

| Private Regard (year) | 0.25 (0.68) | −2.98 (1.06)** | |

| Centrality (year) | 0.40 (0.56) | 0.54 (0.84) | |

| Age | −0.77 (0.48) | −0.78 (0.79) | |

| Nativity | 0.12 (0.69) | 2.19 (1.08)* | |

| Gender | 0.74 (0.70) | 1.47 (0.80) | |

| Exploration (year +1) | Exploration (year) | −0.13 (0.13) | 0.49 (0.18)** |

| Discrimination (year) | 0.02 (0.01)* | 0.02 (0.02) | |

| Age | −0.02 (0.05) | 0.09 (0.08) | |

| Nativity | −0.03 (0.08) | 0.05 (0.10) | |

| Gender | −0.03 (0.07) | −0.08 (0.08) | |

| Commitment (year +1) | Commitment (year) | −0.14 (0.17) | 0.45 (0.26) |

| Discrimination (year) | 0.04 (0.01)** | 0.03 (0.02) | |

| Age | 0.00 (0.04) | 0.10 (0.07) | |

| Nativity | 0.03 (0.07) | −0.06 (0.10) | |

| Gender | −0.03 (0.06) | −0.13 (0.07) | |

| Private Regard (year +1) | Private Regard (year) | 0.12 (0.18) | −0.27 (0.25) |

| Discrimination (year) | 0.03 (0.03) | −0.03 (0.04) | |

| Age | −0.03 (0.10) | 0.24 (0.16) | |

| Nativity | 0.04 (0.15) | 0.14 (0.24) | |

| Gender | 0.02 (0.15) | 0.14 (0.18) | |

| Centrality (year +1) | Centrality (year) | 0.23 (0.21) | −0.25 (0.21) |

| Discrimination (year) | −0.02 (0.04) | 0.10 (0.04)* | |

| Age | −0.00 (0.11) | 0.22 (0.19) | |

| Nativity | 0.14 (0.16) | 0.18 (0.29) | |

| Gender | 0.13 (0.16) | 0.37 (0.21) |

Nativity: 0 = foreign born, 1 = US born; Gender: 0 = female, 1 = male

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01;

p < 0.001

For the between-person analysis of Latinx sample, unconstrained CLPM was conducted, where all of the autoregressive and cross-lagged paths were freely estimated. The model did not fit the data very well (RMSEA = 0.12, 90% CI [0.10, 0.14], CFI = 0.65, TLI = 0.48, SRMR = 0.17). Then, a more parsimonious model, constrained CLPM, which assumes stable autoregressive and cross-lagged coefficients and applies equal constraints for these paths, was conducted but still demonstrated a relatively poor fit (RMSEA = 0.11, 90% CI [0.09, 0.13], CFI = 0.65, TLI = 0.56, SRMR = 0.17). In this model, stability paths for ethnic/racial discrimination (b = 0.55, SE = 0.09, p < 0.001), ethnic/racial identity exploration (b = 0.54, SE = 0.08, p < 0.001), commitment (b = 0.53, SE = 0.07, p < 0.001), private regard (b = 0.52, SE = 0.07, p < 0.001), and centrality (b = 0.41, SE = 0.07, p < 0.001) were all significant. Also, the association between nativity status was positively association with ethnic/racial discrimination (b = 2.83, SE = 1.34, p < 0.05), meaning that Latinx adolescents born in the United States tended to report higher levels of ethnic/racial discrimination. However, similar to Asian sample, none of the cross-lagged paths were significant.

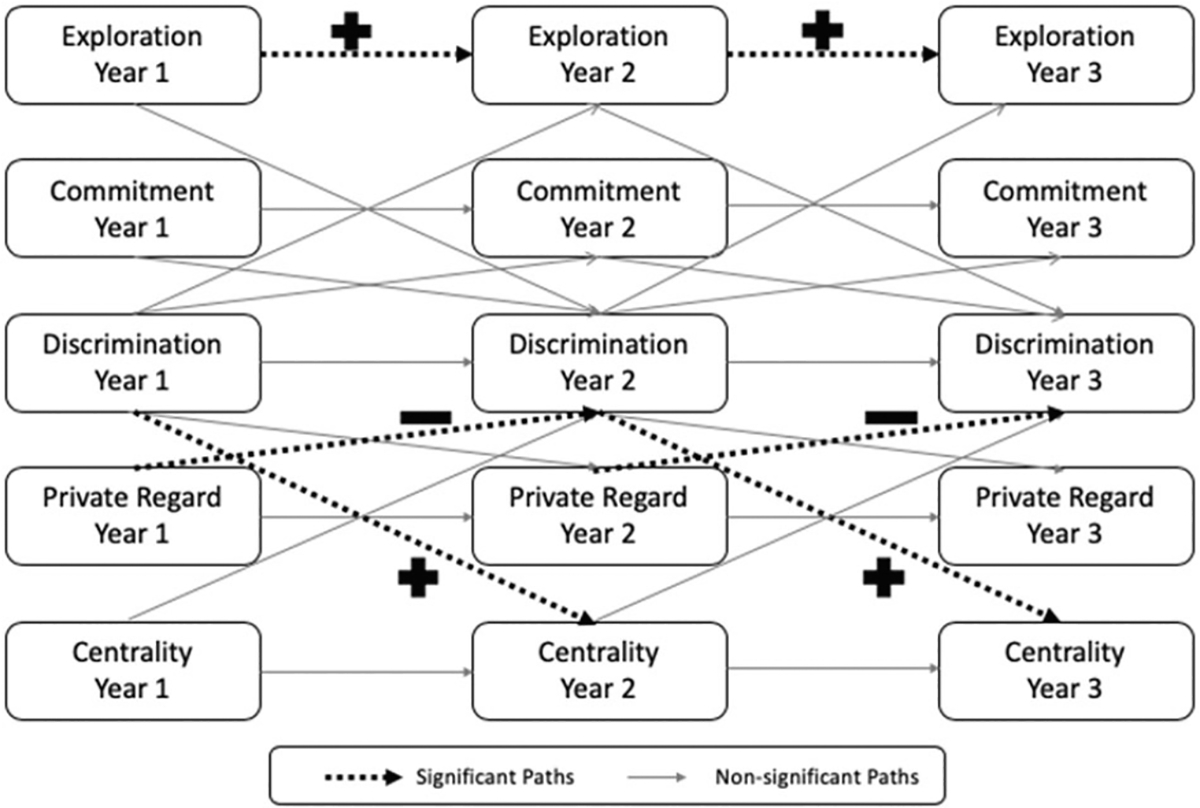

For the within-person analysis of Latinx sample, first, unconstrained RI-CLPM was conducted (Fig. 2). This model did not converge. When a more parsimonious constrained RI-CLPM, which assumes stable autoregressive and cross-lagged coefficients and applies equal constraints for these paths, demonstrated an acceptable fit by most of the fit indices (RMSEA = 0.07, 90% CI [0.04, 0.09], CFI = 0.93, TLI = 0.88, SRMR = 0.09). Again, the poor fit of CLPM highlights the needs for separating the between-person effects and examining the within-person effects in the relationship between ethnic/racial discrimination and ethnic/racial identity. It was considered reasonable to select the constrained RI-CLPM as the final result. The constrained RI-CLPM demonstrates within-person paths from previous year’s ethnic/racial identity private regard to following year’s ethnic/racial discrimination (b = −2.98, SE = 1.06, p < 0.01), from previous year’s ethnic/racial identity exploration to following year’s ethnic/racial identity exploration (b = 0.49, SE = 0.18, p < 0.01) and from ethnic/racial discrimination to following year’s ethnic/racial identity centrality (b = 0.10, SE = 0.04, p < 0.01). Again, Latinx adolescents’ nativity status was associated with ethnic/racial discrimination (b = 2.19, SE = 1.08, p < 0.05), where those who were born in the United States reported higher levels of ethnic/racial discrimination (Table 3).

Fig. 2.

Main results from RI-CLPM examining longitudinal associations between ethnic/racial identity and ethnic/racial discrimination among Latinx adolescents

Sensitivity Analysis

As an additional analysis, when the entire sample containing both Asian and Latinx adolescents were analyzed together, the chi-square test of model fit was not significant (χ2 = 90.43, df = 81, p = 0.22) indicating that it was reasonable to conduct separate analyses for Asian and Latinx adolescents.

In order to provide additional information about potential differences in the experience of discrimination among Asian and Latinx adolescents due to different stereotypes, comparisons were made for the frequency and bothered-ness of discrimination measured at the item-level. The results demonstrated statistically significant differences in the frequency of four items and bothered-ness of five items out of a total 18 items. Latinx adolescents reported higher mean frequency scores than Asian adolescents on items, “being observed or followed while in public places,” “being treated as if you were stupid and or being talked down to,” “being stared at by strangers.” Asian adolescents reported higher mean frequency scores than Latinx adolescents on one item, “others expecting your work to be inferior.” Latinx adolescents reported higher levels of mean bothered-ness on items, “being observed or followed while in public places,” “having your ideas ignored,” “not being taken seriously,” “being stared at by strangers.” Asian adolescents reported higher levels of mean bothered-ness on one item, “mistaken for someone else of your same race.” Similar to the stereotypes reviewed earlier, Latinx adolescents reported more frequent experience of “being treated as if you were stupid and or being talked down to” and similar other items compared to Asian adolescents. Asian adolescents reported higher frequency in a work-related item and were bothered more by being treated as undistinguished “other” than Latinx adolescents. Latinx adolescents also reported higher scores in general on more of the items both in frequency and bothered-ness than Asian adolescents.

Finally, Monte Carlo post hoc power analyses of constrained RI-CLPM models for Asian and Latinx groups were conducted separately with 10,000 observations (NOBSERVATIONS), simulating 1000 samples for replication (NREP). For both Asian and Latinx models, adequate power above 0.80 was observed for all of the main path coefficients although most of the path coefficients for covariates (i.e., age, nativity, and gender) lacked adequate power.

Discussion

Previous studies have documented the importance of ethnic/racial identity and ethnic/racial discrimination in the development of ethnically/racially diverse adolescents. While ethnic/racial identity and ethnic/racial discrimination are expected to be related, the directionality between these developmental constructs remains understudied especially for the two fastest growing ethnic/racial population—Asian and Latinx adolescents. Recent longitudinal designs among Latinx and African American adolescents have started to unpack the developmental dynamics between ethnic/racial identity and ethnic/racial discrimination; the take-home message remains equivocal.

The present study contributes to the existing research on the dynamics between ethnic/racial identity and ethnic/racial discrimination in three significant ways: (1) comparison of between-person and within-person longitudinal designs, (2) consideration of multiple ethnic/racial identity dimensions including developmental and content dimensions and (3) provision of developmental implications for the growing Asian and Latinx adolescent population in urban schools. In summary, within-person, rather than between-person, longitudinal designs explained the current data better. For Asian adolescents, longitudinal, within-person and holistic analyses of ethnic/racial identity dimensions and ethnic/racial discrimination demonstrated that higher levels of previous year’s ethnic/racial identity commitment from one’s own mean predicted higher levels of ethnic/racial discrimination one year later. In turn, higher levels of ethnic/racial discrimination from one’s own mean predicted higher levels of ethnic/racial identity exploration and commitment one year later. For Latinx adolescents, higher levels of ethnic/racial identity private regard from one’s own mean predicted lower levels of ethnic/racial discrimination in the following year. Higher levels of ethnic/racial discrimination, in turn, predicted intrapersonal increase in ethnic/racial identity centrality. Furthermore, higher levels of ethnic/racial identity exploration predicted intrapersonal increase in ethnic/racial identity exploration in the following year. Having been born in the United States was associated with higher levels of ethnic/racial discrimination.

Taken together, the current findings suggest that the dynamic associations between ethnic/racial identity and ethnic/racial discrimination occur internally within-person and may possess qualitatively different meanings for Asian and Latinx adolescents. Specifically, over a 3-year period, important reciprocal within-person associations were observed between ethnic/racial discrimination and developmental dimensions of ethnic/racial identity for Asian adolescents, and between ethnic/racial discrimination and content dimensions of ethnic/racial identity for Latinx adolescents, implying the possible role of different stereotypes attached to each group within the larger society. More detailed discussions of each finding and the study implications follow below.

Between-Person vs. Within-Person Longitudinal Approaches

Between-person designs that examined the associations between the overall levels of ethnic/racial identity and ethnic/racial discrimination did not represent the current study’s data very well. The associations were more clearly observed when changes from one’s own means (i.e., within-person designs) were considered, rather than when each year’s overall levels (i.e., between-person designs) were considered. In other words, the overall levels of ethnic/racial discrimination were not associated with the overall levels of ethnic/racial identity from one year to the next over a 3-year period. Rather, the degree of change in ethnic/racial discrimination from one’s own mean were reciprocally associated with the degree of change in ethnic/racial identity from one’s own mean, implying that the dynamic associations between the experience of ethnic/racial discrimination and the development of ethnic/racial identity are in fact internal psychological processes that occur within-person. These findings underscore the essential role of within-person longitudinal designs in the understanding of the associations between ethnic/racial identity and ethnic/racial discrimination suggested in recent studies (Gonzales-Backen et al. 2018; Zeiders et al. 2017). Accordingly, the following section focuses on and explains the current findings based on the within-person longitudinal analyses for each ethnic/racial group.

Longitudinal Associations between Ethnic/Racial Identity and Ethnic/Racial Discrimination

Asian adolescents

For Asian adolescents, the developmental dimensions of ethnic/racial identity were particularly relevant to the ethnic/racial discrimination experiences. Heightened levels of ethnic/racial identity commitment from one’s own mean predicted increased levels of ethnic/racial discrimination experiences from one’s own mean in the following year. While ethnic/racial identity commitment’s protective role was suggested in a few previous studies (Lee 2005; Noh et al. 1999) and may still be observed in developmental outcomes despite the experience of ethnic/racial discrimination, it may not directly reduce the experience of ethnic/racial discrimination. In fact, the heightened intrapersonal awareness of ethnic/racial discrimination supports the argument of the identification-attribution model (Gonzales-Backen et al. 2018). Increased levels of ethnic/racial identity commitment may have increased adolescents’ awareness and exposure to opportunities for ethnic/racial discrimination. For instance, increased levels of participation in ethnic/racial activities may have prompted socialization of ethnic/racial discrimination experiences and behaviors (Neblett et al. 2008), or increased interactions with discriminatory people or institutions.

These results differ from a recent study that examined within-person associations between ethnic/racial identity and ethnic/racial discrimination among Latinx foreign-born immigrant adolescents (Gonzales-Backen et al. 2018) which found a negative within-person association between ethnic/racial identity commitment and ethnic/racial discrimination, suggesting a potentially protective role of ethnic/racial identity commitment in the perception of ethnic/racial discrimination. The difference here may have resulted from the fact that participants of the current study were Asian adolescents who were mostly born in the United States (74.10%). Ethnic/racial identity commitment may have a stronger protective impact on ethnic/racial discrimination among foreign-born than United States-born adolescents, because ethnic/racial identity commitment of foreign-born adolescents may be based mainly on the country in which their ethnic/racial identity originates, which is likely less affected by the environment. For the United States-born adolescents, ethnic/racial identity may be based on the information gathered from the developmental, and racially-salient environment, which includes the ethnic/racial discrimination experiences. Indeed, Ying et al. (2000) found an exacerbating effect of ethnic/racial identity in the relationship between ethnic/racial discrimination and negative affect among United States-born adolescents, while ethnic/racial identity played a protective role for the foreign-born adolescents. Similarly, in the National Latino and Asian American Study (NLAAS), Yip et al. (2008) observed an exacerbating effect of ethnic/racial identity only among United States-born Asian adults, and not among the foreign-born. Although distinctions must be made between the main effects and moderating effects, these studies hint at potential differences in the way ethnic/racial identity and ethnic/racial discrimination are related among adolescents born in the United States versus another country. Taken together, the qualitative meaning of ethnic/racial identity commitment could be different for United States- versus foreign-born adolescents, which may reconcile differences in the data. Thus, future studies would benefit from systematically considering the moderating effect of adolescents’ nativity in addition to their ethnicity/race.

In addition to potential effects of nativity, other within-group heterogeneity may have also contributed to these differences. For example, adolescents’ national origins (e.g., Chinese, Korean, Filipino, Japanese, Mexicans, Cubans, Puerto Ricans, etc.) and skin color may have created differences in ethnic/racial identity development and exposure to different types and levels of ethnic/racial discrimination. Moreover, how these individual qualities interact with contextual factors such as their socioeconomic status and diversity levels at home, school, and neighborhood may have generated differences in adolescents’ development and experiences. As it was difficult to address all of these qualities within the scope of the current study, it is suggested that future studies include this information.

On the contrary, ethnic/racial identity exploration did not significantly predict within-person increases in ethnic/racial discrimination in the following year. This is in line with a previous study that found no direct association between ethnic/racial identity exploration and self-esteem among Asian adolescents (Umaña-Taylor and Shin 2007). The authors of this previous study explained their findings as possible effects of model minority stereotype, which portrays Asian Americans as academically and socially more successful than other ethnic/racial minority groups in order to create a misconceived image of equal opportunities and meritocracy for all in the United States (Yoo et al. 2010). Due to some of the positively portrayed characteristics of the model minority stereotype, the authors suggested that there may have been less need for Asian American adolescents to explore their ethnic/racial identity to protect their self-esteem. Although ethnic/racial discrimination and self-esteem are distinct psychological processes, this explanation hints at the mechanism in which the model minority stereotype may be related to Asian American adolescents’ psychological processes of their developmental context, including the experience of ethnic/racial discrimination. As Asian adolescents engaged in further exploration to seek more information about their ethnic/racial group membership positive public portrayals of this stereotype may have blurred the perception of ethnic/racial discrimination during the unsettled search process. It is also in line with other within-person research conducted among adolescents mostly born in the United States (Zeiders et al. 2017). Particularly for those who were born in the United States the level of ethnic/racial identity commitment, may have been more relevant than the level of ethnic/racial identity exploration to creating a meaningful impact on the awareness of ethnic/racial discrimination. Further investigation is needed to confirm this. As for the content dimensions, when multiple dimensions were considered holistically, ethnic/racial identity centrality and private regard did not predict Asian adolescents’ ethnic/racial discrimination experiences.

For the direction from ethnic/racial discrimination to ethnic/racial identity, ethnic/racial discrimination contributed to the formation of ethnic/racial identity, increasing both exploration and commitment within-person in the following year, confirming the PVEST and social identity theory. The experience of being treated differently and unfairly because of ethnicity/race may have triggered Asian adolescents to increase their exploration and commitment to their ethnic/racial group despite the possible effects of model minority stereotype. Unfair or differential treatment likely initiates a search for the meaning and social positioning of ethnicity and race and how adolescents choose to incorporate it into their self-concept. The research suggests that not only do positive cultural experiences, such as exposure to ethnic food or music (Umaña-Taylor et al. 2006), or family socialization practices (Hughes et al. 2006) contribute to the formation of ethnic/racial identity, but negative experiences such as ethnic/racial discrimination also contribute to the formation of ethnic/racial identity. These results reiterate the importance of identifying and understanding both positive and negative contributors of ethnic/racial identity development. However, again, ethnic/racial discrimination did not significantly predict ethnic/racial identity centrality and private regard.

While reciprocal relationships were found for developmental dimensions of ethnic/racial identity and ethnic/racial discrimination, why might the content dimensions of ethnic/racial identity not related to ethnic/racial discrimination for Asian adolescents? Again, there may be connections to the model minority stereotype. Asian adolescents may internalize positive attributes of Asian stereotypes and develop positive feelings about their ethnic/racial group membership. As a result, the content dimensions may not have necessarily generated much variability in their perception of ethnic/racial discrimination, or been affected by the experience of ethnic/racial discrimination. Still, the developmental dimensions were found to interact significantly with their experience of ethnic/racial discrimination. Further empirical studies are needed to confirm this possibility. Additionally, understanding the role of ethnic/racial socialization and culture in Asian adolescents’ families, such as the collectivistic culture or the promotion of cultural pride, will be helpful to address in future studies as close links have been found between ethnic/racial socialization and various ethnic/racial identity dimensions (Gartner et al. 2014; Hughes et al. 2009; Rivas-Drake 2011).

Latinx adolescents

For Latinx adolescents, the content dimensions of ethnic/racial identity were particularly relevant to the experience of ethnic/racial discrimination. The developmental dimensions of ethnic/racial identity did not predict ethnic/racial discrimination, which is consistent with an existing study exploring within-person associations between ethnic/racial identity and ethnic/racial discrimination among Hispanic adolescent mothers (Zeiders et al. 2017). However, this observation contrasts to another study that examined within-person associations between ethnic/racial identity and ethnic/racial discrimination among Hispanic immigrant adolescents in Miami and Los Angeles (Gonzales-Backen et al. 2018). Their study found developmental dimensions of ethnic/racial identity to significantly predict ethnic/racial discrimination. Although more studies are needed, the difference may be due to the nativity status of the majority individuals included in the sample as discussed earlier. Most of Latinx adolescents in the current study were born in the United States (87.13%), which was more similar to the sample of Zeiders et al. (2017), again, implicating potential differences in the qualitative meaning of ethnic/racial identity exploration and commitment for the foreign-born versus United States-born adolescents.

Relatedly, another interesting finding for Latinx adolescents was the difference in the mean levels of ethnic/racial discrimination by nativity status. Those who were born in the United States tended to report higher levels of ethnic/racial discrimination both in between-person and within-person designs. This is consistent with a previous finding on African American adults (Krieger et al. 2011) and adds to the discussion of immigrant paradox, which poses the question of whether becoming more Americanized was associated with increased developmental risks (Hernandez et al. 2012). This finding further highlights the importance of incorporating and comparing adolescents’ nativity status in future studies on ethnic/racial discrimination. Also, policies and programs should address the reasons and consequences of the United States-born Latinx adolescents’ tendency to be more prone to experiencing higher levels of ethnic/racial discrimination than those who are foreign-born.

For ethnic/racial identity content dimensions, higher levels of ethnic/racial identity private regard compared to one’s own mean lowered their perception of ethnic/racial discrimination the following year. The reason that a negative relationship was found when both developmental and content dimensions of ethnic/racial identity were considered together may be due to the influence of the prevalent negative stereotypes about Latinx groups in the United States context. For Latinx youth, having the ability to hold a positive view of their ethnic/racial group despite the prevalent negative stereotype may have helped them perceive lower levels of ethnic/racial discrimination, beyond the extent to which their ethnic/racial identity exploration and commitment have developed.

For the path from ethnic/racial discrimination to ethnic/racial identity, again, no developmental dimensions were affected by ethnic/racial discrimination experience in the previous year. Instead, higher levels of ethnic/racial discrimination from one’s own mean tended to increase the levels of Latinx adolescents’ ethnic/racial identity centrality, which is consistent with findings of a previous study on African American college students (Ramos et al. 2012). The within-person longitudinal associations revealed self-appraisal coping processes to be consistent with the social identity and PVEST model. As part of within-person self-appraisal processes, an increase in ethnic/racial discrimination experiences may have heightened one’s desire to place importance on ethnic/racial group membership.

It is noteworthy that the content dimensions, but not the developmental dimensions, of ethnic/racial identity were reciprocally related to ethnic/racial discrimination for Latinx adolescents. This was different from Asian adolescents who displayed significant relationships in the developmental dimensions of ethnic/racial identity. Again, this difference may be due to the pervasiveness of ethnic/racial stereotypes. For Latinx adolescents, in an effort to resist the predominantly negative contents in the stereotypes attached to their ethnic/racial group, their actions and reactions toward the ethnic/racial identity content dimensions may have come out to be more salient than the developmental dimensions when considered holistically. This contributes to the findings from existing scholarship that focused on either developmental or content dimensions of ethnic/racial identity (Gonazales-Backen et al. 2018; Seaton et al. 2009; Zeiders et al. 2017), calling for the need to conduct more studies from this holistic perspective.

Moreover, it has recently been found that developmental dimensions of ethnic/racial identity had a stronger buffering impact on Latinx adolescents’ experience of ethnic/racial discrimination and various developmental outcomes, compared to Asian adolescents (Yip et al. 2019). However, when both developmental and content dimensions were considered together and when their direct relationships with ethnic/racial discrimination were examined, the results of the current study suggested that the content dimensions were salient for Latinx adolescents, whereas developmental dimensions were salient for Asian adolescents. Ethnic/racial identity’s ability to protect or exacerbate the negative influence of ethnic/racial discrimination (i.e., moderating effect) may be independent of the extent to which ethnic/racial discrimination is experienced (i.e., direct effect). Comparing and teasing out direct versus moderating effects of ethnic/racial identity are recommended for future studies.

Finally, it is worth noting that all of the between-person stability paths of the same variable across time were significant, and none of the within-person stability paths except for Latinx adolescents’ ethnic/racial identity exploration were significant. The significant between-person stability paths are consistent with the findings of a previous between-person longitudinal study (Seaton et al. 2009), while the findings of the current study on the stability paths of within-person longitudinal design are mostly consistent with another previous study (Gonzales-Backen et al. 2018). This means that while the overall levels of ethnicity/race-related concepts tend to be similar across time, the changes from one’s own mean at a time point may be independent of changes from one’s own mean one year later. However, for Latinx adolescents, within-person associations were found for ethnic/racial identity exploration across time, which was different from the results of Gonzales-Backen et al. (2018) focusing on immigrant adolescents. Compared to foreign-born immigrant adolescents whose identity may be relatively firmly rooted in the country of birth, increased levels of ethnic/racial identity exploration of Latinx adolescents born in the United States may have triggered further exploration in the following year. The same pattern was not observed in Asian sample probably due to strong within-person reciprocal relationships between ethnic/racial identity exploration and ethnic/racial discrimination. Additional studies that address differences in the stability paths of between-versus within- person designs will be helpful in advancing the understanding of the current study’s results.

Limitations

As with all research, this study is not without its limitations. The sample was recruited from one of the largest and most diverse metropolitan cities in the United States, and one of the earliest ports of entry for immigrants from all over the world. Thus, the historical and sociological context is likely unique to the study sample. While there are certainly universal developmental phenomena associated with ethnic/racial identity and ethnic/racial discrimination, there are also likely context-specific meanings of these constructs as geographic regions have been found to contribute to distinguishing differential ethnic/racial development in Asian and Latinx adolescents (Umaña-Taylor and Shin 2007). Also, although the effects of age, gender, and nativity were examined, it was not possible to examine interactions among these demographic variables due to limited power. Follow up studies that examine the interaction of demographic factors and ethnic/racial identity dimensions with an addition of a narrative approach (Syed and Azmitia 2010) may shed light on the intersection of these constructs. Also, while there is general consistency in the measurement of ethnic/racial identity (i.e., MEIM, Phinney 1992; MIBI, Sellers et al. 1997), there are many different instantiations of ethnic/racial discrimination measurement. In fact, in a recent meta-analysis on ethnic/racial discrimination and outcomes, over 30 different measures of ethnic/racial discrimination were employed (Benner et al. 2018). Even a narrow a sampling of studies reviewed in this paper, Gonzales-Backen et al. (2018) used Perceived Discrimination Scale (Phinney et al. 1998), Baldwin-White et al. (2017) adapted multiple scales from the Bicultural Stressors Scale (Romero and Roberts 2003) and SAFE Acculturative Stress Scale (Mena et al. 1987), Zeiders et al. (2017) used a scale developed by Whitbeck et al. (2001). The current analyses employed the same Daily Life Experiences scale (Harrell 2000) as Seaton et al. (2009). Employing similar measures of ethnic/racial identity and ethnic/racial discrimination will bring coherence to the science of ethnic/racial minority youth development. Also, the reliability scores for some of the ethnic/racial identity measures at Year 1 were relatively low for Latinx adolescents. It may reflect ethnic/racial identity development in its early stage within the context of negative stereotypes. Further studies that examine the invariance of these measures across time will be helpful. Lastly, follow-up studies that examine both short-term and long-term within-person changes in the development of ethnic/racial discrimination and perception of ethnic/racial discrimination over time will also provide valuable information about the developmental trajectories.

Conclusion

While Asian and Latinx populations are the two fastest growing ethnic/racial groups in the United States, attempts to understand their experiences and development have only begun recently. Existing studies have found that the development of ethnic/racial identity and the experience of ethnic/racial discrimination play critical roles in the development of adolescents from these groups. Yet, little is known about how they may be related to one another longitudinally and within-person. This study examined the between- and within-person longitudinal associations between ethnic/racial identity and discrimination over a 3-year period among a total of 241 adolescents. The results demonstrated that the dynamic associations between ethnic/racial identity and ethnic/racial discrimination are likely internal within-person processes that may hold qualitatively different meanings for Asian and Latinx adolescents, possibly due to different stereotypes attached to each group within the larger United States society. Theoretically, the findings of this study provided support for the PVEST (Spencer et al. 2003), identification-attribution model (Gonzales-Backen et al. 2018), and social identity theory (Tajfel 1981) suggesting reciprocal relationships. The findings of the present study highlight the synergistic, longitudinal associations between ethnic/racial identity and ethnic/racial discrimination and underscore the value of analyzing different dimensions of ethnic/racial identity together. Moreover, the use of a within-person longitudinal design has contributed to teasing apart the mixed results regarding the reciprocal relationships between ethnic/racial identity and ethnic/racial discrimination. The current study has also made attempts to understand the increasing but understudied Asian and Latinx adolescents. Nevertheless, the current study can be leveraged to inform policies and programs to promote positive development of ethnic/racial minority adolescents.

Funding