Abstract

In women who die from cancer, breast cancer is the most common cause of death. The development of small molecular scaffolds as specific Cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitors is a promising strategy in the discovery of anti-breast cancer drugs. Isoindolin-1-ones are heterocyclic compounds with useful therapeutic properties. In this study, a library of 48 isoindolinones has been virtually screened by molecular docking that showed high binding affinity up to − 10.1 kcal/mol and conventional hydrogen bonding interactions with active amino acid residues of CDK7. The molecular dynamics simulation (MDS), fragment molecular orbital (FMO), density functional theory (DFT), and pharmacokinetics studies of the best two docked scored ligands 7 and 14 have been studied. Examining the ligand root mean square deviation and hydrogen bonding occupancy of the 100 ns MDS trajectory, both ligands 7 and 14 showed docked pose stability. FMO calculations displayed that LYS139 and LYS41 are majorly contributing to the binding interactions with ligands 7 and 14 in the docked poses. DFT studies of ligands 7 and 14 showed high values of global softness and low values of global hardness and chemical potential thus displaying chemically reactive soft molecules and this influences their anti-cancer activity. Our hits exhibited superior qualities to known CDK7 inhibitors, according to the comprehensive pharmacokinetic parameters that were predicted. The results indicate that isoindolin-1-one moieties are good candidates for anti-cancer action and could serve as effective CDK7 inhibitors.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40203-024-00225-0.

Keywords: Docking, CDK7, Breast cancer, Isoindolin-1-ones, Simulations, DFT

Introduction

Breast cancer is the leading fatal disease in women's cancer-related fatalities (Saghir et al. 2007; Bansode et al. 2019). The diverse and complex biomolecular profiles of breast cancer and the development of drug resistance have reduced the therapeutic effectiveness of existing anti-breast cancer drugs (Bansode et al. 2019). Cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitors have recently emerged as a valuable therapeutic option in hormone-dependent breast cancer (Chatelut et al. 2003). The most significant obstacle to the global increase in longevity is cancer, one of the leading causes of mortality in the twenty-first century (Cui et al. 2020). Chemotherapeutic treatments for breast cancer mainly comprise cytotoxic medications such as tamoxifen, paclitaxel, and docetaxel, but these often come with severe side effects (Bansode et al. 2019; Cui et al. 2020). CDK controls every phase of the cell cycle (Saghir et al. 2007; Bansode et al. 2016; Chashoo and Saxena 2014). The RNA polymerase-based transcription is strictly regulated by the CDK-7 (Peyressatre et al. 2015). Among the transcription-associated kinases, CDK-7 is a remarkable member of the CDK family, because of its unique role in cell division, regulation, and transcription (Galbraith et al. 2019). CDKs are the unique target for new clinical interventions that play a crucial role in cancer growth and progression (Lapenna and Giordano 2009). Only a few CDK-7 inhibitors including SY-1365 and THZ1 with good selectivity have been discovered, and they are now in different phases of clinical trials (Diab et al. 2020; Sánchez-Martínez et al. 2019; Wang et al. 2020). The direct involvement of CDK-7 in many malignancies has made it a desirable target for cancer treatment (Kim et al. 2020; Zhang et al. 2017).

Tumor cells possess intrusive, drug-resistant, metastatic, and anti-apoptotic traits through an abnormal expression of cell-cycle-related proteins (Deshpande et al. 2005; Liu et al. 2020). The genetic disruption of the communicating pathways that control the cells' proliferation, progression of the cell cycle, and apoptosis are characteristics of the disorder's initial steps of beginning (Sanchez-Vega et al. 2018). Inhibition of CDK-7 results in inhibiting both transcription and cell proliferation, which has a specific and precise anticancer effect (Deshpande et al. 2005; Sanchez-Vega et al. 2018). The first significant division of CDKs is the cell-cycle-associated CDKs (CDK-1, 4, and 6), which efficiently regulate cell-cycle progression and the second major division of CDKs is transcription-linked CDKs (CDK-7, 8, 9, 12, and 13) (Galbraith et al. 2019).

The cell cycle and RNA polymerase-based transcription are strictly regulated by the CDK-7 (Kumar et al. 2021). Through its involvement in the phosphorylation of RNA polymerase II, CDK-7 also contributes significantly to transcription (Bansode et al. 2016; Peyressatre et al. 2015). DNA synthesis in the S phase and the onset of mitosis are the two main phases of cell division that CDKs regulate (Bansode et al. 2016; Singla et al. 2013; Wang et al. 2004). Due to CDK7's dual function in cell-cycle control and transcription, there is a need for research in the creation of specific inhibitors to inhibit CDK7 (Peyressatre et al. 2015). With an inhibitory half-maximal dosage (IC50) of 21 nM, BS-181, it has been discovered as the first reversible small-molecule CDK7 inhibitor (Kaliszczak et al. 2013). The fundamental regulators' CDKs recreate an essential function in the initiation and progression of cancer, making them an attractive target for cutting-edge therapeutic strategies (Bansode et al. 2016; Singla et al. 2013). Several CDK7 inhibitors, including roscovitine, are now entering clinical trials, indicating the biological significance of CDK7 as a potential target for anticancer treatment (Chashoo and Saxena 2014; Peyressatre et al. 2015). There is just one known crystal structure of ATP-bound human CDK7 currently (1UA2.pdb) (Lolli et al. 2004). The protein's kinase domain, which has a length of 12 to 295 amino acids, is located at both the N- and C-termini of CDK7, and residues 90 to 170 comprise most of the protein's ATP-binding region (Sanchez-Vega et al. 2018). According to the CDK7 human crystal structure, the ATP-binding location has been identified in the gap between the residues of N- and C-terminal lobe (Lolli et al. 2004). Researchers have previously used information about CDK7's structure and function to design inhibitors that can interact with the enzyme's ATP-binding site (Diab et al. 2020; Lolli et al. 2004). The structural-based method utilized THZ1-bound structure (PDB ID: 6DX3), the sole covalent inhibitor also available. Hence, a complete analysis of the molecular mechanisms behind the special recognition of CDK7 by ligands and the kinetics of ligand-receptor interactions is crucial to the sound understanding of isoform-specific inhibitors (Chohan et al. 2016).

Small-molecule inhibitors with high selectivity profiles that are going to be successful in clinical trials are difficult to develop for kinase medications due to substantial similarity across the family members (Hazel et al. 2017; Norman et al. 2012). However, only a limited number of inhibitors have been observed to be highly effective against CDK7 due to adverse effects and low efficacy. The research demonstrates that tremendous progress has been made in the last years towards the development of CDK inhibitors (Diab et al. 2020; Sánchez-Martínez et al. 2019; Wang et al. 2020). Several inhibitors have demonstrated nanomolar potency against CDK7 but inhibit a wide range of CDK family members, which restricts their usefulness as selective inhibitors. Wang et al. recently reviewed the evidence on CDK7 inhibitors and came to the conclusion that the inhibition of residues like GLY21, PHE91, MET94, ASP155, THR170, and CYS312 is due to one or more hydrogen bonds with residues outside the kinase domain (Wang et al. 2020).

The isoindolin-1-ones moiety is regarded as a fundamental scaffold and virtually serves as a model for constructing compounds. Many literature studies reporting several isoindolin-1-one analogs as kinase inhibitors supported this hypothesis (Curtin et al. 2004). Due to these compounds, a broad range of remarkable biological activities, organic chemists have pioneered various methodologies for synthesizing isoindolin-1-ones using various chemical processes, such as base-catalyzed cyclization and transition metal-catalyzed cyclization (Savela and Méndez-Gálvez 2021; Brahmchari et al. 2018). Most of the isoindolinones had kinases as their primary target family, according to the "Swiss Target Prediction," which identified kinases as the significant target family (Mehta et al. 2023).

A simple, effective, and rapid molecular modelling technique called molecular docking predicts a ligand's active conformation in the active site of its target protein and utilizes a docking score to calculate the binding affinity between the ligand and protein (Chohan et al. 2016). MDS on specific complexes were used to evaluate the stability and binding affinity of the possible inhibitors with CDK7 under different physiological configurations. (Kumar et al. 2021). This handles the ligand-receptor combination flexibly and has typically been used to post-process docking data to accurately represent the dynamical behaviour of the complex at the atomic level (Meng et al. 2011). The Groningen Machine for Chemical Simulations (GROMACS v5.1.5) was used to perform MDS to better comprehend how proteins and possible substances interact in physiological circumstances (Pronk et al. 2013; Abraham et al. 2023). There were various in silico studies including QSAR, molecular docking, molecular dynamics simulation, density functional theory previously reported for the design of anti-cancer drugs (Er-rajy et al. 2022, 2023a, b, 2024; Ismail et al. 2023; Mellaoui et al. 2024). We believe our work will benefit medicinal chemists and may be useful in developing product-derived pharmaceuticals.

Materials and methods

Structure based virtual screening

In silico evaluation of the isoindolin-1-ones are done using cheminformatics tools to evaluate the bioactivity of a virtually synthesized series/library of 48 compounds. PerkinElmer ChemDraw Professional version 19.0.0.22 was employed to create two-dimensional molecular structures and SMILES notations for the isoindolin-1-ones. For molecular docking, SMILES notations have been converted to three-dimensional structures using Open Bable software (O'Boyle et al. 2011). The crystal structure of the protein kinase 7 associated with cell division in humans (PDB code: 1UA2) has been downloaded from the protein database https://www.rcsb.org (Lolli et al. 2004). The protein structure was cleaned while preserving the protein's existing hydrogen.

In the ongoing study, CDK7 (1UA2.pdb) has been docked with active isoindolin-1-ones using Pyrx virtual screening tool (Dallakyan and Olson 2015), in which AUTODOCK VINA is the software used for docking. PyRx is a high-throughput screening program that can be used in computational drug development to assess libraries of compounds against potential therapeutic targets (Halgren 1999). The energy of all the ligands have been minimized using the Pyrx software itself and adopting the MMFF94 force-field (Khanapure et al. 2018; Sonawane et al. 2020), present in OpenBabel tab. Subsequently, the compounds were converted to AutoDock ligands (.pdbqt) for docking. The dimensions and coordinates of the grid box were set to x = 27.5196954757, y = 24.1364940961, z = 31.6729233435 and, x = 40.1201560853, y = -− 4.39739797297, z = 21.8199590208, respectively. Exhaustiveness value was set to of 500.

Usually, multiple conformations of the ligand inside the active region of the receptor are frequently produced by the docking software. In the docking investigations for the comparison analysis, three well-known selective CDK7 inhibitors were employed. Then, using the visualizer software, BIOVIA Discovery Studio Visualizer (Dassault Systèmes 2021), we examined the interactions of the top-scoring docked complexes to find the strong hydrogen bonding connections. The discovery of lower binding energy emphasizes the stable complex formation. The hydrogen bonding interactions in the docked complexes of CDK7 (1UA2.pdb) and active ligands were analysed. We then examined various interactions like H-bonds, Pi-stacks, hydrophobic molecules, and van der Waals forces.

Molecular dynamics simulations

Compounds 7 and 14, which exhibited outstanding docking results, were subjected to further Molecular Dynamics Simulations using the GROMACS software (Pronk et al. 2013; Abraham et al. 2023). The CHARMM36-jul2021 force field was used in GROMACS and SwissParam to produce the Ligand topology (Zoete et al. 2011; Sapay and Tieleman 2011). The equilibration process was performed under NVT and NPT ensembles for 200 ps at 300 k, using a V-rescale thermostat and a Parrinello-Rahman barostat, respectively (Parrinello and Rahman 1981). During the simulation Run, the TIP3P water model was used for hydration. Using BIOVIA Discovery Studio, and CPPTRAJ of AmberTools (Roe and Cheatham 2013, 2018), the MD simulation trajectory was analysed. For 100 ns, all simulations were done using periodic boundary conditions.

Pharmacokinetic studies

The pharmacokinetic characteristics (PK) were studied using in silico methods (Lagorce et al. 2017; Pires et al. 2015). The PK features of a given chemical were taken into account, including subcategories in absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity (Lagorce et al. 2017; Pires et al. 2015). PK characteristics were predicted in the current investigation utilizing an open webserver called pkCSM (Pires et al. 2015). In order to evaluate the attributes of the chosen hits, PerkinElmer ChemDraw Professional version 19.0.0.22 was utilized (https://biosig.unimelb.edu.au/pkcsm/)(viewed on March 2, 2023). According to the threshold and expected values available on the website (https://biosig.lab.uq.edu.au/pkcsm/theory), the output data were evaluated for two ligands (7 and 14). Also, the pharmacokinetics data of known ligands of CDK7 (Ricci-Lopez et al. 2021; National Center for Biotechnology Information 2023a, b, c) were used for comparison studies with ligands 7 and 14.

DFT calculations

The DFT calculations of Ligands 7 and 14 were done using Gaussian 09W software (Frisch et al. 2009). Basis set used for geometry optimization was 6-31G(d,p) for both organic ligands to increase the efficacy of DFT calculations with DFT/B3LYP method (Zhang et al. 2023; Shukla et al. 2020; Shalaby et al. 2023; Anwer et al. 2023). The threshold converged values of maximum remaining force on an atom in the system, average average (RMS, root mean square) force on all atoms, the maximum structural change of one coordinate(maximum displacement), average (RMS) change over all structural parameters in the last two iterations were set to 0.000450, 0.000300, 0.001800 and 0.001200 Hartrees/Bohr respectively for geometry optimization. Geometry optimized molecule was further used for frontier HOMO–LUMO and molecular electrostatic potential surface (MESP) analysis using 6-31G(d,p) as basis set. Results were shown on the GaussView 6.0.16 program (Dennington et al. 2016).

FMO calculations

To find the contribution of specific CDK7 residues interaction with ligands 7 and 14 in a more quantitative way, fragment molecular orbital (FMO) calculations (Kitaura et al. 1999) were done which rely on the quantum mechanics computation. The docked poses of ligands 7 and 14 and protein residues within 4.5 Å distance from ligands were isolated from docked complexes and used for the preparation of input files for FMO calculations. Input Files were generated using Facio 25.1.2 software (Suenaga 2005). All the FMO calculations were performed using GAMESS implementation (Schmidt et al. 1993) at MP2/6-31G* level. Total pair interaction energy (PIE) was analyzed using Facio software.

Results and discussion

Structure based virtual screening

In the context of molecular docking, exhaustiveness refers to the thoroughness or completeness with which the Monte Carlo method explores the conformational space (possible orientations and conformations) of the molecules being docked. The Monte Carlo method is a stochastic algorithm used to sample different conformations of molecules in the search for the most energetically favourable binding pose. The term "exhaustiveness" typically refers to the number of different conformations explored during the docking process. So, using the exhaustiveness value of 500 in PyRx software, docking was done and binding interaction results between protein and ligand were observed.

The results indicate that the isoindolin-1-ones moieties are crucial for anticancer action because they have remarkable drug-like features and could serve as effective CDK7 inhibitors. For observing the interactions, the ligand conformation with the most favourable binding interactions and the docking score were taken into account. These docked complexes exhibited negative binding energies, indicating the structure's stability. Out of 48 ligands, 41 ligands exhibited hydrogen bonding interactions. We have determined the essential interactions that impact the predicted binding affinity, i.e., hydrogen bonding interactions among hydrophobic interactions and electrostatic interactions.

By observing the interactions, the ligand conformation with the most favourable binding interactions and the docking score were taken into account. We have determined the important interactions that impact the predicted binding affinity i.e. hydrogen bonding interactions. Results showed that the generated iso-indolinones had good binding affinity for CDK7.

The ligands 1–48 for CDK7 calculated binding energies ranging from -6.8 to -10.1 kcal/mol (Table 1), evidencing the preferential binding towards CDK7. According to the docking experiment data, ligand 7 has the lowest binding energy (-10.1 kcal/mol), strong hydrogen bonding interactions and forms a stable complex with CDK7 compared to known inhibitors (National Library and of Medicine National Centre for Biotechnology Information 2023a, b, c, d). Hence, it is indicated by investigations utilizing molecular docking and MDS that the ligand 7 with CDK7 has a strong and stable hydrogen bonding interaction, indicating that it is a promising therapeutic candidate to inhibit CDK7. Moreover, ligand 14 also has the lowest binding energy (-9.3 kcal/mol), strong hydrogen bonding interactions, and forms a stable complex with CDK7 compared to other known inhibitors (Vijayakumar et al. 2019; Gupta 2016). The results of the virtual docking investigation exhibit that isoindoline-1-ones with halogen and electron-withdrawing substituents have a more significant influence on anticancer activity, which may be because they are getting close to a conformation that will fit perfectly into the active region of CDK7 (Er-Rajy et al. 2024). Hence, results showed that the generated iso-indolinones had an excellent binding affinity for CDK7.

Table 1.

Binding Energy values(kcal/mol) and hydrogen bonding interactions of library of isoindolin-1-ones with CDK7 protein residues

| Ligand no | Structure | Binding energy (Kcal/mol) | Hydrogen bonding with protein residues |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |  |

− 9.4 |

LYS139 ASN141 ASN142 |

| 2 |  |

− 8.3 | MET94 |

| 3 |  |

− 9.7 |

LYS139 ASN141 ASN142 |

| 4 |  |

− 9.5 |

LYS139 ASN141 ASN142 |

| 5 |  |

− 9.3 |

LYS139 ASN141 ASN142 |

| 6 |  |

− 9.8 | – |

| 7 |  |

− 10.1 |

MET94 LYS139 ASN141 ASN142 |

| 8 |  |

− 9.4 |

LYS139 ASN141 ASN142 |

| 9 |  |

− 8.5 | LYS139 |

| 10 |  |

− 9.8 |

LYS139 ASN141 ASN142 |

| 11 |  |

− 8.5 |

LYS139 ASN141 ASN142 |

| 12 |  |

− 9 | - |

| 13 |  |

− 8.1 | ASP97 |

| 14 |  |

− 9.3 |

GLN22 LYS41 SER161 |

| 15 |  |

− 9.1 | LYS139 |

| 16 |  |

− 9.1 |

PHE23 SER161 |

| 17 |  |

− 8.9 | LYS139 |

| 18 |  |

− 9.3 | LYS139 |

| 19 |  |

− 9.2 |

LYS139 ASN141 |

| 20 |  |

− 8.1 | - |

| 21 |  |

− 8.6 | ASN141 |

| 22 |  |

− 9.3 |

LYS41 MET94 |

| 23 |  |

− 9.2 | MET94 |

| 24 |  |

− 9.3 | MET94 |

| 25 |  |

− 9.2 | LYS41 |

| 26 |  |

− 9.1 | MET94 |

| 27 |  |

− 9 | LYS41 |

| 28 |  |

− 8.3 | MET94 |

| 29 |  |

− 8.3 | MET94 |

| 30 |  |

− 9.3 | - |

| 31 |  |

− 8.9 |

LYS41 MET94 |

| 32 |  |

− 8.8 |

LYS41 MET94 |

| 33 |  |

− 9.2 | LYS41 |

| 34 |  |

− 8.9 | MET94 |

| 35 |  |

− 7.1 | MET94 |

| 36 |  |

− 8 | MET94 |

| 37 |  |

− 8.1 |

LYS41 MET94 |

| 38 |  |

− 6.8 | MET94 |

| 39 |  |

− 8.8 | MET94 |

| 40 |  |

− 9.1 | MET94 |

| 41 |  |

− 9 | MET94 |

| 42 |  |

− 8.9 | MET94 |

| 43 |  |

− 9.1 | MET94 |

| 44 |  |

− 9 | MET94 |

| 45 |  |

− 9.7 | – |

| 46 |  |

− 9.2 |

ASP92 ASP155 |

| 47 |  |

− 8.5 | LYS41 |

| 48 |  |

− 9.1 | MET94 |

We have identified 20 active amino acid in CDK7 protein i.e.—LEU18, GLU20, GLY21, GLN22, PHE23, ALA24, VAL26, ALA39, LYS41, ASP92, PHE91, PHE93, MET94, ASP97, LYS139, ASN141, ASN142, LEU144, ALA154, SER161 on the basis of Biovia Discovery Studio Visualizer. We can design better inhibitors by analysing the docking experiments and identifying the crucial amino acid residues involved in ligand binding. Binding mode analysis showed hydrogen bond interactions with the residues in the hinge region. Ligands 1, 3, 4, 5, 8, 10, and 11 exhibited a good binding affinity with CDK7, forming three hydrogen bonds with LYS139, ASN142, and ASN141 (Table 1). Ligands 2, 23, 24, 26, 28, 29, 34, 35, 36, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, and 48 exhibited a good binding affinity with CDK7, forming one hydrogen bond with MET94. The ligands 6, 12, 20, 30, 38, and 45 did not exhibit good binding affinity with CDK7 because none form hydrogen bonds. The ligand 46 did not exhibit an excellent binding affinity with CDK7 because of the formation of unfavourable donor bonds. Ligand 7 exhibited the strongest binding affinity with CDK7, followed by ligands 3, 4, 6, 7, 10, 14, and 45 (Table 1). Four hydrogen bond interactions have formed with the target protein's amino acid residues LYS139, ASN141, ASN142, and MET94 in the ligand 7 generated docking pose (Fig. 1). Ligand 14 also exhibited an excellent binding affinity (− 9.3 kcal/mol) with CDK7, forming three hydrogen bonds with the GLN22, LYS41 & SER161 (Fig. 2). Only ligands 14 and 16 exhibited hydrogen bonding with SER161.

Fig. 1.

a 2-D protein–ligand interactions diagram of Ligand 7 b 3-D protein–ligand interactions diagram of Ligand 7

Fig. 2.

a 2-D protein–ligand interactions diagram of Ligand 14 b 3-D protein–ligand interactions diagram of Ligand 14

Molecular dynamics simulations

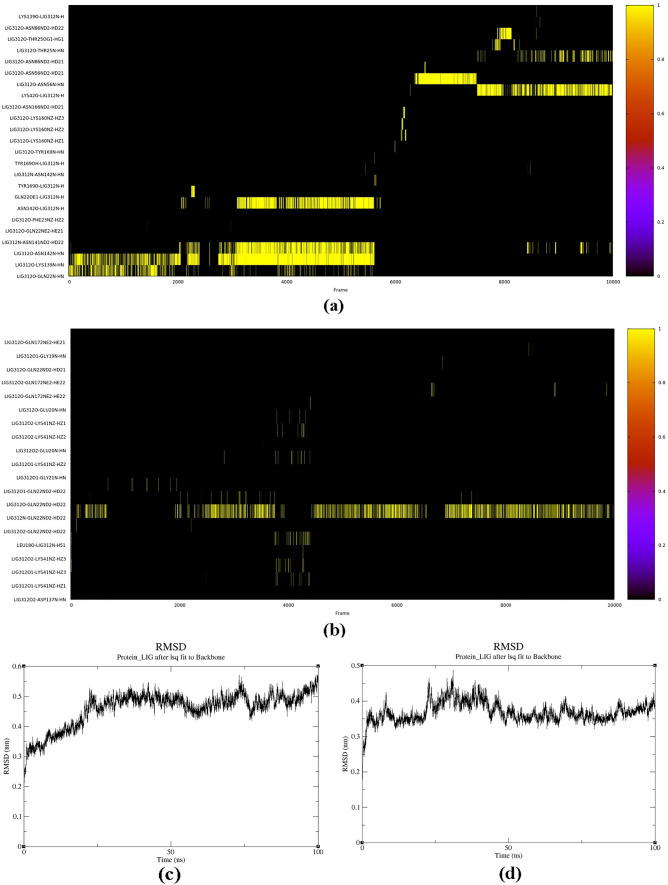

To gain an understanding of how molecules interact in physiological environments, MDS have been done with two CDK7-bound inhibitor complexes that simulated independently for 100 ns. The presence of hydrogen bond interactions with the hinge region residues in the binding mode analysis indicates that these interactions may be crucial for the binding of the ligand to the protein and that interfering with these interactions may impact the binding affinity or specificity. An illustration of hydrogen bonds between particular protein residues and ligand molecules over time is called a hydrogen bonding graph (Figs. 3a and b). These figures displayed the total numbers of hydrogen bonds formed between specific protein residues of CDK7 and ligands 7 and 14 respectively over the frames generated during the complete 100 ns simulation. LYS139 showed hydrogen bonding with ligand 7 for more than 50% of the simulation time, also ASN142 showed persistent hydrogen bonding for 35% of the simulation time while in case of ligand 14, most of the time, hydrogen bonding retained with GLN22 residue. Thus, these results indicated the effective binding of protein residues with ligands 7 and 14.

Fig. 3.

MD simulation analysis display the (a) hydrogen bonding graph—hydrogen bonds formed between specific residues in the protein and ligand 7 molecules (b) hydrogen bonding graph—hydrogen bonds formed between specific residues sin the protein and ligand 14 molecules over complete 100 ns simulation (c) RMSD of whole protein–ligand 7 complex (d) RMSD of whole protein–ligand 14 complex

The RMSD of whole protein–ligand complex including all the backbone atoms and alpha carbons was investigated to determine the stability of the simulated complexes during the MD run. The resolution of experimental structure, size and flexibility of the ligand, and the kind of interaction between the protein and ligand can all affect the typical value of RMSD for a protein–ligand complex.

Generally, a low RMSD value indicates a good fit between the protein and the ligand. In the case of a protein–ligand complex, RMSD is determined by superimposing the protein structures in both conformations and comparing the locations of the ligand's atoms in its bound conformation to the positions of the same atoms in its unbound conformation. We have obtained the RMSD of whole protein–ligand 7 and 14 complexes in the range of 0.2–0.6 nm and 0.2–0.5 nm respectively for 100 ns simulation (Fig. 3c and d). The RMSD of ligand 14 complex showed high stability in comparison of ligand 7 complex. It is significant to highlight that additional criterion, including shape complementarity, electrostatic interactions, and hydrogen bonding, must be considered to assess the strength of a protein–ligand complex in addition to RMSD.

Pharmacokinetic studies

A computational approach called pKCSM (Prediction of Kinase-specific CDK Substrate Motifs) forecasts the potential phosphorylation sites of kinase-specific substrates. According to the threshold and expected values available on the website (https://biosig.lab.uq.edu.au/pkcsm/theory), the output data were evaluated for two ligands 7 and 14 and three known inhibitors of CDK7: BS-181, THZ1, and Milciclib were taken for pharmacokinetics study comparison as shown in Table 2. According to PK characteristics results analysis, ligands 14 and 7 can be potential CDk7 inhibitors.

Table 2.

Pharmacokinetic characteristics of ligand 7, ligand 14, BS-181, THZ1 and Milciclib

| Pharmacokinetic characteristics | Ligand 7 | Ligand 14 | BS-181 | THZ1 | Milciclib | Optimum range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular weight (g/mol) | 355.824 | 395.458 | 380.54 | 566.065 | 460.586 | Less than 500 |

| LogP | 5.0034 | 4.67562 | 4.3985 | 6.3305 | 2.5658 | Less than 5 |

| Rotatable bonds | 1 | 3 | 11 | 9 | 4 | Less than 7 |

| Acceptors | 1 | 3 | 6 | 6 | 8 | Less than 10 |

| Donors | 1 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 2 | Less than 5 |

| Surface area | 156.689 | 175.707 | 167.103 | 241.834 | 199.741 | Less than 120 |

| Water solubility (log mol/L) | − 4.346 | − 4.868 | − 4.115 | − 3.264 | − 3.641 | |

| Caco2 permeability (log Papp in 10–6 cm/s) | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.766 | 0.863 | 1.291 | More than 0.90 |

| Intestinal absorption (human) | 94.518% | 98.208% | 86.832% | 93.019% | 96.174% | More than 30% |

| Skin permeability (log Kp) | − 2.76 | − 2.741 | − 2.828 | − 2.735 | − 2.775 | Less than − 2.5 |

| P-glycoprotein substrate | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| P-glycoprotein I inhibitor | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | |

| P-glycoprotein II inhibitor | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| VDss (human) (log L/kg) | 0.23 | − 0.128 | 1.267 | − 0.642 | 0.968 | Higher than 0.45 |

| Fraction unbound (human) | 0.103 | 0.097 | 0.152 | 0.165 | 0.204 | |

| BBB permeability (log BB) | 0.582 | − 0.14 | − 0.935 | − 1.264 | − 0.917 | Greater than 0.3 |

| CNS permeability (log PS) | − 0.175 | − 0.535 | − 2.514 | − 2.2 | − 2.562 | Greater than − 2 |

| CYP2D6 substrate | No | No | No | No | No | |

| CYP3A4 substrate | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| CYP1A2 inhibitor | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | |

| CYP2C19 inhibitor | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | |

| CYP2C9 inhibitor | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | |

| CYP2D6 inhibitor | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | |

| CYP3A4 inhibitor | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | |

| Total Clearance (log mL/min/kg) | − 0.047 | 0.284 | 1.156 | 0.488 | 0.571 | |

| Renal OCT2 substrate | No | No | No | No | Yes | |

| AMES toxicity | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | |

| Max. tolerated dose (human)(log mg/kg/day) | 0.543 | 0.287 | − 0.095 | 0.434 | 0.141 | Less than or equal to 0.477 |

| hERG I inhibitor | No | No | No | No | No | |

| hERG II inhibitor | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Oral rat acute toxicity (LD50) (mol/kg) | 2.813 | 2.756 | 2.786 | 2.847 | 3.051 | |

| Oral rat chronic toxicity (log mg/kgbw/day) | 1.602 | 1.796 | 1.135 | 1.677 | 1.076 | |

| Hepatotoxicity | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Skin sensitization | No | No | No | No | No | |

| T. Pyriformis toxicity (log ug/L) | 0.314 | 0.303 | 0.465 | 0.285 | 0.312 | Less than − 0.5 |

| Minnow toxicity (log mM) | − 0.193 | − 2.626 | 0.201 | 2.066 | 2.242 | More than − 0.3 |

As we know, cytotoxic agents' toxicity is prioritized over the selected scaffold's anticancer activity. We have conducted the PK analysis to check the little difference between the toxicity and therapeutic effects of the desired drug. We can find the potential anticancer drug molecule with the fewest side effects and the known difference between toxicity concentrations and therapeutic effects.

Even if a hypothesized substrate motif gets a high score, it may not be physiologically relevant. Ultimately, it is crucial to evaluate other aspects, such as the conservation of the pattern across species, experimental evidence of phosphorylation at the motif, and potential functional repercussions of phosphorylation. Experimentally confirming pKCSM predictions is crucial. In vitro phosphorylation tests, mutagenesis studies, and in vivo phosphorylation level measurements are all examples of experimental validation.

Comparison analysis of pharmacokinetic characteristics with known inhibitors reveals distinctive features between ligands 7 and 14, suggesting potential advantages for ligand 7 in terms of hERG inhibition. Milciclib is predicted to be a hERG II inhibitor but not a hERG I inhibitor. Ligand 7 may act as a potentially safer option, aligning with drug development goals to minimise cardiac-related complications. The compounds exhibit favorable Caco-2 permeability values, particularly ligand 14, indicating high predicted absorption through the human small intestine. Ligand 14 is predicted to be very well-absorbed in the human small intestine compared to other known ligands. Ligands 7 and 14, BS-181, and THZ1 are predicted to be P-glycoprotein I and P-glycoprotein II inhibitors. Cytochrome P450 inhibition profiles vary among the compounds, with Ligands 7 and 14, BS-181, and THZ1 predicted to be inhibitors for multiple isoforms. In contrast, Milciclib is not predicted to inhibit most isoforms. The predicted log BB for ligand 14 is below 0.3, indicating that this ligand may have limited distribution into the brain. All the compounds (Ligand 7, Ligand 14, BS-181, THZ1, and Milciclib) are predicted to have CNS permeability values below -2, suggesting limited penetration into the CNS. These characteristics work together to highlight the need for experiments to make decisions in the drug development process.

DFT calculations

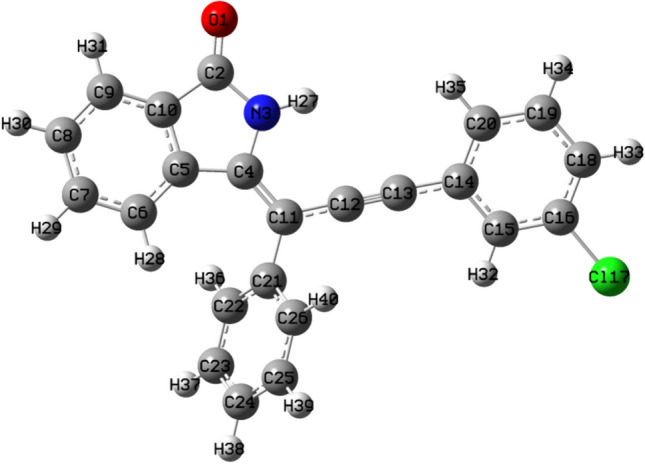

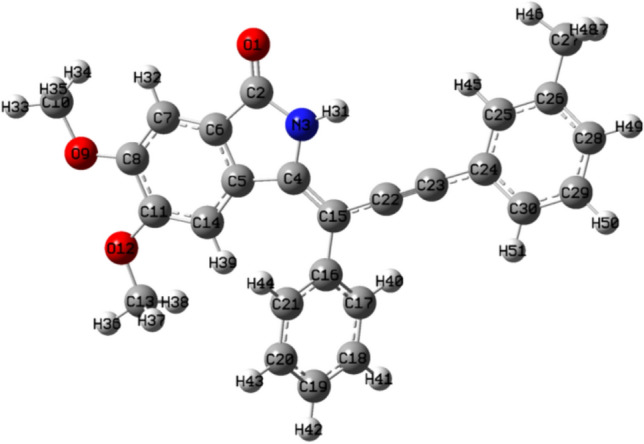

For DFT calculations, geometry optimization is important to get the molecule in the highest possible stable state and lowest energy state. It is the initial step for the DFT studies of organic compounds. The maximum remaining force on an atom in the system, average average (RMS, root mean square) force on all atoms, the maximum structural change of one coordinate(maximum displacement), average (RMS) change over all structural parameters in the last two iterations must be less than 0.000450, 0.000300, 0.001800 and 0.001200 Hartrees/Bohr respectively, then, stationary point was found and geometry was optimized. Until then, no. of cycles and iterations were repeated over and over again. Figures 4 and 5 showed the optimized structures of ligands 7 and 14 respectively obtained through software.

Fig. 4.

Optimized structure of ligand 7

Fig. 5.

Optimized structure of ligand 14

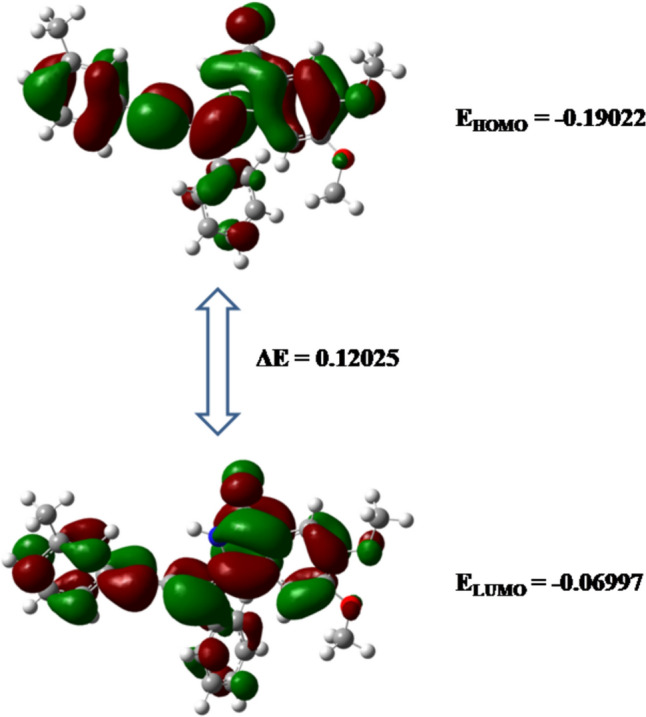

Frontier molecular orbitals is the study of highest occupied molecular orbitals (HOMO) and lowest unoccupied molecular orbitals (LUMO) of organic compounds is crucial for checking of reactivity and stability of compound. If the energy gap between HOMO and LUMO (ΔE) is low, compound is considered as more reactive and soft while in contrast, if ΔE is high, compound is considered as less reactive and hard (Pearson 1986; Renuga and Muthu 2014). Figures 6 and 7 showed the 3-D HOMO, LUMO images and EHOMO, ELUMO and ΔE values of ligands 7 and 14 respectively. Lower ΔE values indicated the high chemical reactivity and softness of these molecules.

Fig. 6.

3-D HOMO, LUMO images and EHOMO, ELUMO and ΔE values of ligand 7

Fig. 7.

3-D HOMO, LUMO images and EHOMO, ELUMO and ΔE values of ligand 14

Additionally, global reactivity parameters such as ionization potential, electron affinity, global hardness, electronegativity, chemical potential, global softness and electrophilicity index were calculated with the help of EHOMO and ELUMO values (Mary et al. 2020) as shown in Table 3. High values of global softness and low values of global hardness and chemical potential indicated that ligands 7 and 14 are chemically reactive soft molecules and thus influences their anti-cancer biological activity.

Table 3.

Global Reactivity Parameters for Ligand 7 and 14

| Parameter | Ligand 7 | Ligand 14 |

|---|---|---|

| EHOMO | − 0.204 | − 0.190 |

| ELUMO | − 0.083 | − 0.070 |

| Ionization potential | 0.204 | 0.190 |

| Electron affinity | 0.083 | 0.070 |

| ΔE | 0.122 | 0.120 |

| Global hardness | 0.061 | 0.060 |

| Electronegativity | 0.144 | 0.130 |

| Chemical potential | − 0.144 | − 0.130 |

| Global softness | 8.226 | 8.316 |

| Global electrophilicity index | 0.170 | 0.141 |

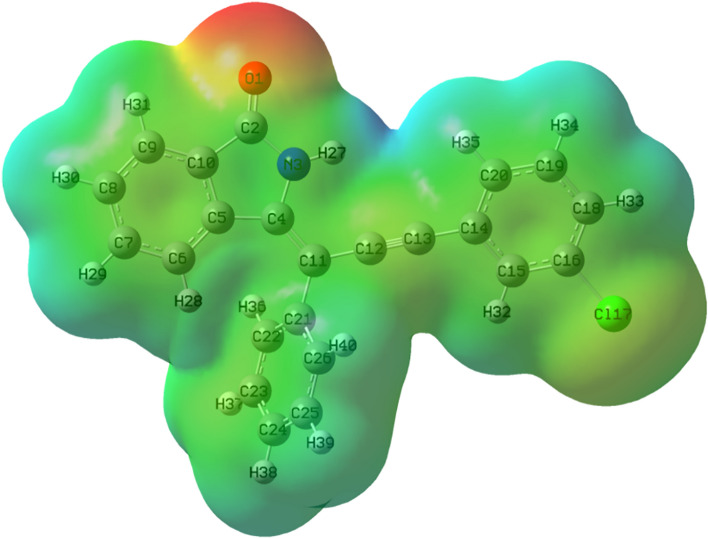

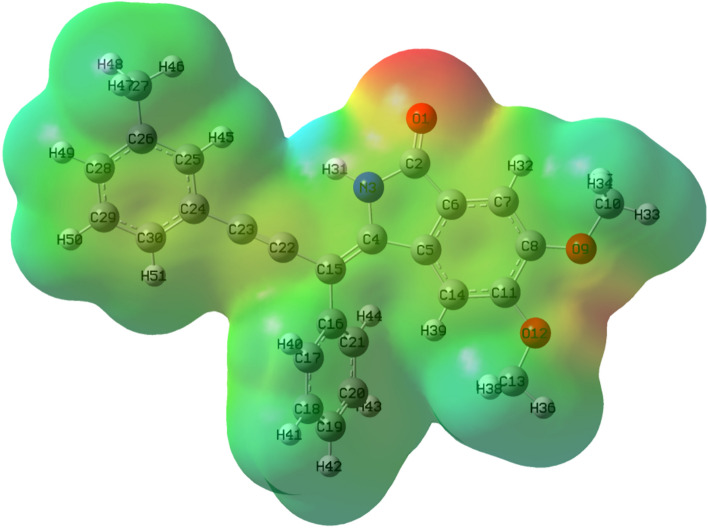

Molecular electrostatic potential (MEP) surfaces are useful for the correlation of molecular structure with the biological activity of compounds. Red colour region in MEP surface is the nucleophilic region which indicated negative electrostatic potential and susceptible with electrophilic attack as high electron density is present whereas blue colour region is the electrophilic region exhibited positive electrostatic potential and proned with nucleophilic attack due to low electron density.

Increasing order of electrostatic potential of different colours is Red < Orange < Yellow < Green < Blue (Beegum et al. 2019). MEP is important for the fact that it indicates the positive or negative electrostatic potential of a molecule with the help of colour grading. Figures 8 and 9 showed the 3-D MEP surface images of ligand 7 and 14 respectively with labelled atoms.

Fig. 8.

3-D MEP surface image of ligand 7

Fig. 9.

3-D MEP surface image of ligand 14

For ligand 7, the oxygen atom of isoindolin-1-one (O1) is highlighted by a red region, which indicated that O1 has high nucleophilic tendency than any other atom of ligand 7 which makes it susceptible to attack with electrophiles. Also, the H27 atom attached to N3 atom of isoindolin-1-one ring is near a blue region which showed high electrophilic tendency than any other atom of ligand 7 which makes it susceptible to attack with nucleophiles. The remaining atoms covered with a green region indicated less tendency towards any electrophile or nucleophile. This analysis can be correlated with the binding interactions as shown in "Structure based virtual screening" section between Ligand 7 and CDK7 protein in docking. O1 undergoes hydrogen bonding with electrophilic parts of LYS139 and ASN142 residues and H27 atom shows hydrogen bonding with nucleophilic parts of ASN141 and ASN142 residues.

The same type of observation is shown in the case of ligand 14, a dark red region is shown near O1 atom, light red colour is shown near other O9 and O12 atoms, so, O1 atom is highly susceptible for the electrophilic attack. By correlating this analysis with docking interactions, O1 atom undergoes hydrogen bonding with GLN22 whereas O12 and O9 atoms undergo hydrogen bonding with LYS41 and SER161 respectively. Thus, MEP surfaces are highly helpful in predicting which part of ligands is highly susceptible for electrophilic or nucleophilic interaction with active amino acid residues of protein. This is helpful in understanding the binding mechanism and in the development of potential inhibitors.

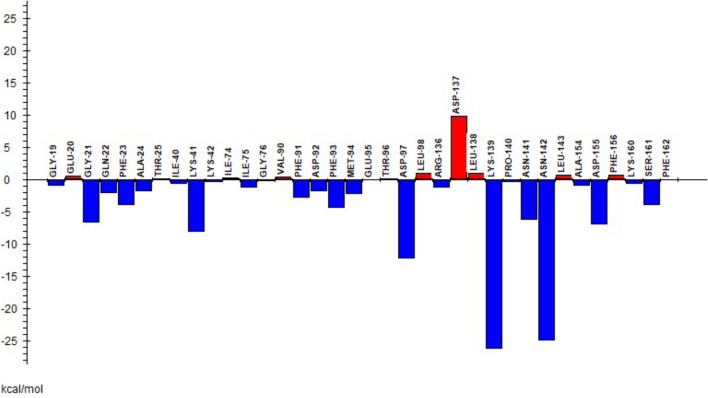

FMO calculations

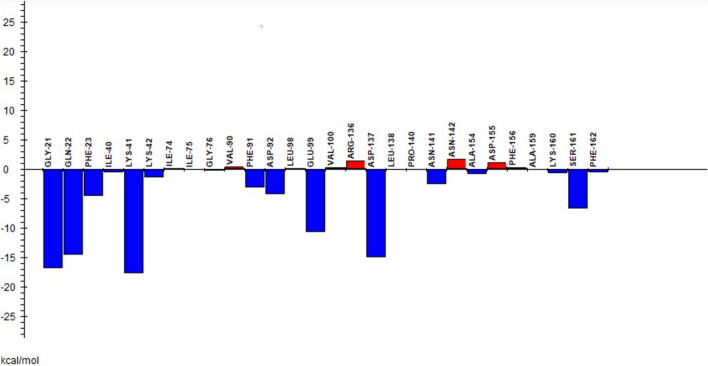

In FMO, system was divided into amino acid residues and ligands. Each amino acid residue was fragmented into one fragment and total pair interaction energy (PIE) between amino acid fragments and ligands was estimated as shown in Figs. 10 and 11 for ligands 7 and 14 respectively. Ligand 7 showed the highest total pair interaction energy with LYS139 residue having a value of − 26.32 kcal/mol. The second highest pair interaction energy, − 25.012 kcal/mol was with ASN142. Other amino acid residues GLY21, PHE23, LYS41, ASP97, ASN141, and ASP155 are also helpful in the successful binding with ligand having total PIEs of − 2.769, − 3.977, − 8.123, − 12.278, − 6.275 and − 7.036 kcal/mol respectively. On the other hand, ligand 14 showed a higher total PIE value of − 17.68 kcal/mol with LYS41. GLY21, GLN22, GLU99, ASP137 display total PIE values of − 16.864, − 14.543, − 10.643, and − 15.041 kcal/mol respectively and thus these residues are significant for the efficient binding in the active region of CDK7 protein.

Fig. 10.

Plot of Total Pair Interaction Energy values between ligand 7 and CDK7 amino acid residues

Fig. 11.

Plot of total pair interaction energy values between ligand 14 and CDK7 amino acid residues

Conclusion

Cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitors are an important target for the treatment of breast cancer. Isoindolin-1-ones are pharmaceutically active heterocyclic compounds. A total of 48 isoindolin-1-one derivatives have been virtually screed to act as CDK inhibitors. Based on molecular dynamics simulation (MDS), fragment molecular orbital (FMO), density functional theory (DFT), and pharmacokinetics studies, two ligands 7 and 14 have been identified as potential CDK7 inhibitors. To effectively target CDK7 inhibition, we have applied a structure-based pharmacophore modelling technique with several additional computational tools. Further focus will be on evaluating different analogs and conducting research to enhance bioactivity. This research has provided fresh opportunities to create more specific CDK7 inhibitors in the future and may help develop more potent and widely available anti-cancer treatments.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to Delhi Technological University for infrastructure and support.

Author contributions

C.A. and K.M. wrote the main manuscript text, did the docking studies, S.M. gave the initial concept, and R.S. reviewed the manuscript, and supervised.

Data availability

A supplementary data file of complete library of isoindolin-1-ones with CDK7 protein is provided.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Abraham M, Alekseenko A, Bergh C, Blau C, Briand E, Doijade M, Fleischmann S, Gapsys V, Garg G, Gorelov S, Gouaillardet G, Gray A, Irrgang ME, Jalalypour F, Jordan J, Junghans C, Kanduri P, Keller S, Kutzner C, Lemkul JA, Lundborg M, Merz P, Miletic V, Morozov D, Pall S, Schulz R, Shirts M, Shvetsov A, Soproni B, van der Spoel D, Turner P, Uphoff C, Villa A, Wingbermuhle S, Zhmurov A, Bauer P, Hess B, Lindahl E. 2023. GROMACS 2023 manual (Version 2023) Zenodo. [DOI]

- Anwer KE, Sayed GH, Kozakiewicz-Piekarz A, Ramadan RM. Novel annulated thiophene derivatives: Synthesis, spectroscopic, X-ray, Hirshfeld surface analysis, DFT, biological, cytotoxic and molecular docking studies. J Mol Struct. 2023;1276:134798. doi: 10.1016/j.molstruc.2022.134798. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bansode P, Jadhav J, Kurane R, Choudhari P, Bhatia M, Khanapure S, Salunkhe R, Rashinkar G. Potentially antibreast cancer enamidines: via azide-alkyne-amine coupling and their molecular docking studies. RSC Adv. 2016;6:90597–90606. doi: 10.1039/c6ra20583f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bansode P, Anantacharya R, Dhanavade M, Kamble S, Barale S, Sonawane K, Satyanarayan ND, Rashinkar G. Evaluation of drug candidature: In silico ADMET, binding interactions with CDK7 and normal cell line studies of potentially anti-breast cancer enamidines. Comput Biol Chem. 2019;83:107124. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiolchem.2019.107124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beegum S, Panicker CY, Armaković S, Armaković SJ, Arisoy M, Temiz-Arpaci O, Alsenoy CV. Spectroscopic, antimicrobial and computational study of novel benzoxazole derivative. J Mol Struct. 2019;1176:881–894. doi: 10.1016/jmolstruc201809019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- BIOVIA Dassault Systèmes [Discovery Studio 2021 client] [Discovery Studio Visualizer v211020298] San Diego: Dassault Systèmes 2021

- Brahmchari D, Verma AK, Mehta S. Regio- and stereoselective synthesis of isoindolin-1-ones through BuLi-Mediated Iodoaminocyclization of 2-(1-Alkynyl)benzamides. J Org Chem. 2018;83:3339–3347. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.7b02903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chashoo G, Saxena AK. Targetting CDKs in cancer: an overview and new insights. J Cancer Sci Ther. 2014;6:488–496. doi: 10.4172/1948-5956.1000313. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chatelut E, Delord JP, Canal P. Toxicity patterns of cytotoxic drugs. Invest New Drugs. 2003;21:141–148. doi: 10.1023/a:1023565227808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chohan TA, Qian HY, Pan YL, Chen JZ. Molecular simulation studies on the binding selectivity of 2-anilino-4-(thiazol-5-yl)-pyrimidines in complexes with CDK2 and CDK7. Mol Biosyst. 2016;12:145–161. doi: 10.1039/c5mb00630a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui W, Aouidate A, Wang S, Yu Q, Li Y, Yuan S. Discovering anti-cancer drugs via computational methods. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:733. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.00733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtin ML, Frey RR, Heyman HR, Sarris KA, Steinman DH, Holmes JH, Bousquet PF, Cunha GA, Moskey MD, Ahmed AA, Pease LJ, Glaser KB, Stewart KD, Davidsen SK, Michaelides MR. Isoindolinone ureas: a novel class of KDR kinase inhibitors. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2004;14:4505–4509. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2004.06.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallakyan S, Olson AJ. Small-molecule library screening by docking with PyRx Methods. Mol Biol. 2015;1263:243–250. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-2269-7_19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennington R, Keith TA, Millam JM (2016) Gauss view 6.0.16. Semichem Inc Shawnee Mission, KS, USA

- Deshpande A, Sicinski P, Hinds PW. Cyclins and cdks in development and cancer: a perspective. Oncogene. 2005;24:2909–2915. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diab S, Yu M, Wang S. CDK7 inhibitors in cancer therapy: the sweet smell of success? J Med Chem. 2020;63:7458–7474. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b01985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Saghir NS, Khalil MK, Eid T, El Kinge AR, Charafeddine M, Geara F, Seoud M, Shamseddine AI. Trends in epidemiology and management of breast cancer in developing arab countries: a literature and registry analysis. Int J Surg. 2007;5:225–233. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2006.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Er-rajy M, El Fadili M, Hadni H, Mrabti NN, Zarougui S, Elhallaoui M. 2D-QSAR modeling, drug-likeness studies, ADMET prediction, and molecular docking for anti-lung cancer activity of 3-substituted-5-(phenylamino) indolone derivatives. Struct Chem. 2022;33:973–986. doi: 10.1007/s11224-022-01913-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Er-rajy M, Mujwar S, Imtara H, Alshawwa SZ, Nasr FA, Zarougui S, Elhallaoui M. Design of novel anti-cancer agents targeting COX-2 inhibitors based on computational studies. Arab J Chem. 2023;16:105193. doi: 10.1016/j.arabjc.2023.105193. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Er-Rajy M, El Fadili M, Mujwar S, Zarougui S, Elhallaoui M. Design of novel anti-cancer drugs targeting TRKs inhibitors based 3D QSAR, molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulation. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2023;41:11657–11670. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2023.2170471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Er-Rajy M, Faris A, Zarougui S, Elhallaoui M. Design of potential anti-cancer agents as COX-2 inhibitors, using 3D-QSAR modeling, molecular docking, oral bioavailability proprieties, and molecular dynamics simulation. Anticancer Drugs. 2024;35:117–128. doi: 10.1097/CAD.0000000000001492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisch MJ, Trucks GW, Schlegel HB, Scuseria GE, Robb MA, Cheeseman JR, Scalmani G, Barone V, Mennucci B, Petersson GA, Nakatsuji H, Caricato M, Li X, Hratchian HP, Izmaylov AF, Bloino J, Zheng G, Sonnenberg JL (2009) Gaussian. Inc, CT Wallingford

- Galbraith MD, Bender H, Espinosa JM. Therapeutic targeting of transcriptional cyclin dependent kinases. Transcription. 2019;10:118–136. doi: 10.1080/21541264.2018.1539615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta VP. Electro Density analysis and electrostatic potential. Princ Appl Quantum Chem. 2016 doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-803478-100006-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Halgren TA. MMFF VI MMFF94s option for energy minimization studies. J Comput Chem. 1999;20:720–729. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-987X(199905)20:7<720::AID-JCC7>30CO,2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazel P, Kroll SH, Bondke A, Barbazanges M, Patel H, Fuchter MJ, Coombes RC, Ali S, Barrett AG, Freemont PS. Inhibitor selectivity for cyclin-dependent kinase 7: a structural, thermodynamic, and modelling study. ChemMedChem. 2017;12:372–380. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201600535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ismail MF, Aboelnaga A, Naguib MM, Ismaeel HM. Synthesis, anti-proliferative activity, DFT and docking studies of some novel chloroquinoline-based heterocycles. Polycycl Aromat Compd. 2023 doi: 10.1080/10406638.2023.2271112. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaliszczak M, Patel H, Kroll SH, Carroll L, Smith G, Delaney S, Heathcote DA, Bondke A, Fuchter MJ, Coombes RC, Barrett AG, Ali S, Aboagye EO. Development of a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor devoid of ABC transporter-dependent drug resistance. Br J Cancer. 2013;109:2356–2367. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khanapure S, Jagadale M, Bansode P, Choudhari P, Rashinkar G. Anticancer activity of ruthenocenyl chalcones and their molecular docking studies. J Mol Struct. 2018;1173:142–147. doi: 10.1016/jmolstruc201806091. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Cho YJ, Ryu JY, Hwang I, Han HD, Ahn HJ, Kim WY, Cho H, Chung JY, Hewitt SM, Kim JH, Kim BG, Bae DS, Choi CH, Lee JW. CDK7 is a reliable prognostic factor and novel therapeutic target in epithelial ovarian cancer. J Oncol. 2020;156:211–221. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2019.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitaura K, Ikeo E, Asada T, Nakano T, Uebayasi M. Fragment molecular orbital method: an approximate computational method for large molecules. Chem Phys Lett. 1999;313:701–706. doi: 10.1016/S0009-2614(99)00874-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar V, Parate S, Thakur G, Lee G, Ro HS, Kim Y, Kim HJ, Kim MO, Lee KW. Identification of CDK7 inhibitors from natural sources using pharmacoinformatics and molecular dynamics simulations. Biomedicines. 2021;9:1197. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines9091197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagorce D, Douguet Miteva MA, Villoutreix BO. Computational analysis of calculated physicochemical and ADMET properties of protein-protein interaction inhibitors. Sci Rep. 2017;7:46277. doi: 10.1038/srep46277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapenna S, Giordano A. Cell cycle kinases as therapeutic targets for cancer. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2009;8:547–566. doi: 10.1038/nrd2907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu K, Zheng M, Lu R, Du J, Zhao Q, Li Z, Li Y, Zhang S. The role of CDC25C in cell cycle regulation and clinical cancer therapy: a systematic review. Cancer Cell Int. 2020;20:213. doi: 10.1186/s12935-020-01304-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lolli G, Lowe ED, Brown NR, Johnson LN. The crystal structure of human CDK7 and its protein recognition properties. Struct. 2004;12:2067–2079. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2004.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mary YS, Yalcin G, Mary YS, Resmi KS, Thomas R, Önkol T, Kasap EN, Yildiz I. Spectroscopic, quantum mechanical studies, ligand protein interactions and photovoltaic efficiency modeling of some bioactive benzothiazolinone acetamide analogs. Chem Pap. 2020;74:1957–1964. doi: 10.1007/s11696-019-01047-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta S, Mangyan M, Brahmchari D. Design, synthesis and anti-cancer activity evaluation of a 3-methyleneisoindolin-1-one library. Comb Chem High Throughput Screen. 2023;26:1775–1792. doi: 10.2174/1386207325666221003093623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellaoui MD, Zaki K, Abbiche K, Imjjad A, Boutiddar R, Sbai A, Jmiai A, El Issami S, Lamsabhi AM, Zejli H. In silico anticancer activity of isoxazolidine and isoxazolines derivatives: DFT study, ADMET prediction, and molecular docking. J Mol Struct. 2024 doi: 10.1016/j.molstruc.2024.138330. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meng XY, Zhang HX, Mezei M, Cui M. Molecular docking: a powerful approach for structure-based drug discovery. Curr Comput-Aided Drug Des. 2011;7:146–157. doi: 10.2174/157340911795677602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Biotechnology Information. PubChem. https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/thz. Accessed 18 December 2023

- National Center for Biotechnology Information. PubChem. https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/bs-181. Accessed 18 December 2023

- National Center for Biotechnology Information. PubChem. https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Milciclib. Accessed 18 December 2023

- Norman RA, Toader D, Ferguson AD. Structural approaches to obtain kinase selectivity. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2012;33:273–278. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2012.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Boyle NM, Banck M, James CA, Morley C, Vandermeersch T, Hutchison GR. Open Babel: An open chemical toolbox. J Cheminform. 2011;3:33. doi: 10.1186/1758-2946-3-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrinello M, Rahman A. Polymorphic transitions in single crystals: a new molecular dynamics method. J Appl Phys. 1981;52:7182–7190. doi: 10.1063/1328693. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson G. Absolute electronegativity and hardness correlated with molecular orbital theory. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1986;83:8440–8441. doi: 10.1073/pnas83228440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peyressatre M, Prével C, Pellerano M, Morris MC. Targeting cyclin-dependent kinases in human cancers: from small molecules to peptide inhibitors. Cancers. 2015;7:179–237. doi: 10.3390/cancers7010179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pires DEV, Blundell TL, Ascher DB. pkCSM: Predicting small-molecule pharmacokinetic and toxicity properties using graph-based signatures. J Med Chem. 2015;58:4066–4072. doi: 10.1021/acsjmedchem5b00104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pronk S, Páll S, Schulz R, Larsson P, Bjelkmar P, Apostolov R, Shirts MR, Smith JC, Kasson PM, van der Spoel D, Hess B, Lindahl E. GROMACS 4.5: a high-throughput and highly parallel open source molecular simulation toolkit. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:845–854. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renuga S, Muthu S. Molecular structure, normal coordinate analysis, harmonic vibrational frequencies, NBO, HOMO–LUMO analysis and detonation properties of (S)-2-(2-oxopyrrolidin-1-yl) butanamide by density functional methods. Spectrochim Acta A Mol Biomol Spectrosc. 2014;118:702–715. doi: 10.1016/jsaa201309055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricci-Lopez J, Aguila SA, Gilson MK, Brizuela CA. Improving structure-based virtual screening with ensemble docking and machine learning. J Chem Inf Model. 2021;61:5362–5376. doi: 10.1021/acsjcim1c00511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roe DR, Cheatham TE., III PTRAJ and CPPTRAJ: software for processing and analysis of molecular dynamics trajectory data. J Chem Theory Comput. 2013;9:3084–3095. doi: 10.1021/ct400341p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roe DR, Cheatham TE. Parallelization of CPPTRAJ enables large scale analysis of molecular dynamics trajectory data. J Chem Theory Comput. 2018;39:2110–2117. doi: 10.1002/jcc25382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Martínez C, Lallena MJ, Sanfeliciano SG, de Dios A. Cyclin dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitors as anticancer drugs: recent advances (2015–2019) Bioorganic Med Chem Lett. 2019;29:126637. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2019.126637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Vega F, Mina M, Armenia J, Chatila WK, Luna A, La KC, Dimitriadoy S, Liu DL, Kantheti HS, Saghafinia S, Chakravarty D, Daian F, Gao Q, Bailey M, Liang WW, Foltz SM, Shmulevich I, Ding L, Heins Z, Ochoa A, Gross B, Gao J, Zhang H, Kundra R, Kandoth C, Bahceci I, Dervishi L, Dogrusoz U, Zhou W, Shen H, Laird PW, Way GP, Greene CS, Liang H, Xiao Y, Wang C, Lavarone A, Berger AH, Bivona TG, Lazar AJ, Hammer GD, Giordano T, Kwong LN. Oncogenic signaling pathways in the cancer genome atlas. Cell. 2018;173:321–337. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.03.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapay N, Tieleman DP. Combination of the CHARMM27 force field with united-atom lipid force fields. J Comput Chem. 2011;32:1400–1410. doi: 10.1002/jcc21726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savela R, Méndez-Gálvez C. Isoindolinone synthesis via one-pot type transition metal catalyzed C-C bond forming reactions. Chem Eur J. 2021;27:5344–5378. doi: 10.1002/chem.20200437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt MW, Baldridge KK, Boatz JA, Elbert ST, Gordon MS, Jensen JH, Koseki S, Matsunaga N, Nguyen KA, Su S, Windus TL, Dupuis M, Montgomery JA., Jr General atomic and molecular electronic structure system. J Comput Chem. 1993;14:1347–1363. doi: 10.1002/jcc540141112. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shalaby MA, Fahim AM, Rizk SA. Microwave-assisted synthesis, antioxidant activity, docking simulation, and DFT analysis of different heterocyclic compounds. Sci Rep. 2023;13:4999. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-31995-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shukla AK, Chaudhary AP, Pandey J. Synthesis, spectral analysis, molecular docking and DFT studies of 3-(2, 6-dichlorophenyl)-acrylamide and its dimer through QTAIM approach. Heliyon. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e05016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singla P, Luxami V, Paul K. Benzimidazole-biologically attractive scaffold for protein kinase inhibitors. RSC Adv. 2013;4:12422–12440. doi: 10.1039/c3ra46304d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sonawane K, Barale SS, Dhanavade MJ, Waghmare SR, Nadaf NH, Kamble SA, Naik NM. Homology modeling and docking studies of TMPRSS2 with experimentally known inhibitors camostat mesylate, nafamostat and bromhexine hydrochloride to control SARS-coronavirus-2. ChemRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.26434/chemrxiv.12162360.v1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suenaga M. Facio: new computational chemistry environment for PC GAMESS. J Comput Chem. 2005;4:25–32. doi: 10.2477/jccj425. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- US National Library of Medicine National Centre for Biotechnology Information. PubChem. https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Trilaciclib. Accessed 7 March 2023

- US National Library of Medicine National Centre for Biotechnology Information. PubChem. https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/thz1. Accessed 7 March 2023

- US National Library of Medicine National Centre for Biotechnology Information. PubChem. https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/bs-181. Accessed 7 March 2023

- US National Library of Medicine National Centre for Biotechnology Information. PubChem. https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Milciclib. Accessed 7 March 2023

- Vijayakumar V, Prabakran A, Radhakrishnan N, Muthu S, Chidambaram RK, Paulraj EI. Synthesis, characterization, spectroscopic studies, DFT and molecular docking analysis of N4, N4’-dibutyl-3 3’-diaminobenzidine. J Mol Struc. 2019;1179:325–335. doi: 10.1016/jmolstruc201811018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Wood G, Meades C, Griffiths G, Midgley C, McNae I, Fischer PM. Synthesis and biological activity of 2-anilino-4-(1H-pyrrol-3-yl) pyrimidine CDK inhibitors. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2004;14:4237–4240. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2004.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M, Wang T, Zhang X, Wu X, Jiang S. Cyclin-dependent kinase 7 inhibitors in cancer therapy. Future Med Chem. 2020;12:813–833. doi: 10.4155/fmc-2019-0334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Peng H, Wang X, Yin X, Ma P, Jing Y, Cai MC, Liu J, Zhang M, Zhang S, Shi K, Gao WQ, Di W, Zhuang G. Preclinical efficacy and molecular mechanism of targeting CDK7-dependent transcriptional addiction in ovarian cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2017;16:1739–1750. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-17-0078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Li T, Zhao L, Xu H, Yan C, Jin Y, Wang Z. DFT-aided infrared and electronic circular dichroism spectroscopic study of cyclopeptide S-PK6 and the exploration of its antitumor potential by molecular docking. J Mol Struct. 2023;1278:134903. doi: 10.1016/j.molstruc.2023.134903. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zoete V, Cuendet MA, Grosdidier A, Michielin O. SwissParam: a fast force field generation tool for small organic molecules. J Comput Chem. 2011;32:2359–2368. doi: 10.1002/jcc21816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Abraham M, Alekseenko A, Bergh C, Blau C, Briand E, Doijade M, Fleischmann S, Gapsys V, Garg G, Gorelov S, Gouaillardet G, Gray A, Irrgang ME, Jalalypour F, Jordan J, Junghans C, Kanduri P, Keller S, Kutzner C, Lemkul JA, Lundborg M, Merz P, Miletic V, Morozov D, Pall S, Schulz R, Shirts M, Shvetsov A, Soproni B, van der Spoel D, Turner P, Uphoff C, Villa A, Wingbermuhle S, Zhmurov A, Bauer P, Hess B, Lindahl E. 2023. GROMACS 2023 manual (Version 2023) Zenodo. [DOI]

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

A supplementary data file of complete library of isoindolin-1-ones with CDK7 protein is provided.