Abstract

Functional group compatibility in an amide bond cleavage reaction with hydrazine was evaluated for 26 functional groups in the functional group evaluation (FGE) kit. Accurate and rapid evaluation of the compatibility of functional groups, such as nitrogen-containing heterocycles important in drug discovery research, will enhance the application of this reaction in drug discovery research. These data will be used for predictive studies of organic synthesis methods based on machine learning. In addition, these studies led to discoveries such as the unexpected positive additive effects of carboxylic acids, indicating that the FGE kit can propel serendipitous discoveries.

Keywords: amide bond cleavage, functional group compatibility, functional group evaluation kit, carboxylic acid, zinc trifluoromethanesulfonate

1 Introduction

Amide bonds are among the most abundant chemical bonds in nature and are widely found in various organic molecules, such as peptides, natural products, and pharmaceuticals (Pattabiraman and Bode, 2011; Kaspar and Reichert, 2013; Brown and Bostrom, 2016). The chemical stability of amide bonds is extremely high due to their tendency to form resonance structures (Kemnitz and Loewen, 2007; Wang and Cao, 2011; Mahesh et al., 2018), and this stability affords beneficial properties to amide compounds. Due to their stability, except for biochemical cleavage by enzymes such as peptidases (Dai et al., 1995; Wu et al., 2020), chemical cleavage of amide bonds is quite difficult and often requires harsh reaction conditions (Thorner et al., 2000; Rashed et al., 2019; Lv et al., 2023). If amide bonds can be cleaved under mild conditions, the corresponding carboxylic acid equivalents and amines can be synthesized from various amides. Therefore, the development of amide bond cleavage reactions under mild conditions has attracted increased attention in recent years. Although several excellent reactions have been reported (Chaudhari and Gnanaprakasam, 2019; Li and Szostak, 2020), cleavage of common unactivated amides still requires the use of highly reactive metal catalysts, strict anhydrous conditions, and higher reaction temperatures.

To overcome these problems, we took advantage of the high nucleophilicity of hydrazine and found that simple inorganic ammonium salts, such as ammonium iodide, efficiently accelerated bond cleavage of unactivated amides 1 under mild conditions to afford the corresponding acyl hydrazides 2 and amines 3 in high yields (Scheme 1) (Shimizu et al., 2014). Furthermore, by employing a continuous microwave flow reactor, the reaction was easily scaled up (100 mmol scale, 23 mmol h–1) (Noshita et al., 2019). The obtained acyl hydrazides were easily converted into the corresponding ester 5 by reacting with β-diketone, such as acetylacetone, to the active amide acylpyrazole 4 (Kashima et al., 1994). By combining these reactions, both the carboxylic acid and amine portions of the amide 1 can be effectively utilized for further transformations.

SCHEME 1.

Ammonium salts promoted cleavage of amide bond with hydrazine and further transformation to esters.

If this reaction could be applied to amides with various functional groups, its usefulness would be greatly enhanced. The functional groups (FGs) are involved in the properties and reactivity of molecules and form the basis for organic chemistry and pharmaceutical chemistry (Dreos et al., 2011; Ertl, 2017). Although several functionalized amide substrates were investigated, comprehensive information on the functional group compatibility in this reaction has not yet been collected due to difficulties in synthesizing such functionalized amide substrates. Therefore, we used a functional group evaluation (FGE) kit (Saito et al., 2023), which allows for accurate and rapid assessment of information on the functional group compatibility using 26 FGE compounds, including the nitrogen-containing heterocycles imidazole and indole, important in drug discovery research (Collins and Glorius, 2013). In this system, the functional group compatibility of a given reaction is assessed by adding 26 external additives with various functional groups. Using this method, comprehensive data on functional group compatibility can be collected and entered into our “Digitization-driven Transformative Organic Synthesis (Digi-TOS)” database (https://en.digi-tos.jp). Artificial intelligence (AI) and digitization show great potential in next-generation organic synthesis, and data-driven prediction research of synthesis is essential to do so. In this regard, reliable information about functional group compatibility and chemoselectivity is important to understand the applicability of the reaction. This Digi-TOS database will be used for the development of a machine learning-based organic synthesis prediction method, such as a retrosynthetic analysis method (Mikulak-Klucznik et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2023). For this purpose, it is essential to ensure the reliability of data, and therefore, statistical methods are used for handling the data. Another purpose of the FGE kit is to discover unexpected chemoselectivity and unexpected “positive” additive effects. Such unexpected discoveries, which are commonly referred to as “serendipitous,” frequently result in the development of reactions (Maegawa et al., 2011). In fact, in the present study, we found the unexpected positive additive effect of carboxylic acids, and further investigation allowed us to develop a new Lewis acid-catalyzed reaction system. Our results demonstrate that FGE kit effectively promotes serendipitous discovery.

2 Results and discussion

2.1 Evaluation of functional group compatibility using FGE kit

2.1.1 Optimization of reaction conditions

Previously, we successfully developed ammonium salt-accelerated hydrazinolysis of unactivated amides using ammonium iodide and hydrazine monohydrate under mild conditions (Shimizu et al., 2014). To evaluate this reaction using the FGE kit, we selected N-(4-(trifluoromethoxy)phenyl)-4-(trifluoromethyl)benzamide (1) as the substrate because yields of the corresponding products 4-(trifluoromethyl)benzohydrazide (2) and 4-(trifluoromethoxy)aniline (3) can be determined by 19F NMR analysis of the crude mixture without affecting 1H-based contaminants such as additives in the FGE kit.

We first optimized reaction conditions for the hydrazinolysis of amide 1aa using General Procedure A (Table 1) (See Supplementary Material for detailed information). Under the standard conditions of our previous studies using 10 equiv of hydrazine hydrate and 1.0 equiv of ammonium iodide at 70 °C for 48 h, the reaction gave only 20% of benzohydrazide 2a (Entry 1). The reaction in the absence of solvent did not proceed (Entry 2). Increasing the reaction temperature to 100 °C increased the yield of 2a to 85% in 24 h (Entry 3). Aiming to accelerate the reaction, we performed the reaction using acidic solvent hexafluoroisopropanol (Zhang et al., 2018; Kabi et al., 2020; Bhattacharya et al., 2021) and trifluoroethanol (Entries 4 and 5) (Smithrud et al., 1990; Bautista et al., 1999; Bai et al., 2019); the use of trifluoroethanol led to desired product 2a in 93% yield. Using trifluoroethanol as the solvent in the absence of ammonium iodide decreased the reaction rate, however, clearly indicating that ammonium salt is important for achieving high reactivity (Entry 6) (Shimizu et al., 2012). On the other hand, the addition of 2 equiv of ammonium iodide decreased the yield of the product (Entry 7). NH4OAc (Kumar et al., 2022) instead of NH4I resulted in the lower yield of 2a (Entry 8). When hydrazine monohydrate was not added, the reaction did not proceed and amide 1aa was recovered quantitatively (Entry 9). Although increasing the amount of hydrazine from 10 to 20 equiv. improved the yield (Entry 10), the change was not significant (Entry 5). On the other hand, two equivalents of hydrazine gave 2a in 14% yield (Entry 11); therefore, 10 equiv was considered optimal. The concentration of the solvent also affected the reaction (Entries 12–14), and a 1 M solvent concentration was optimal (Entry 5). As shown in this table, the yields of benzohydrazide 2a and aniline 3a were nearly identical, so only the yields of 2a are listed in the following tables (See Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Optimization of reaction condition using amide 1aa.

| |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | X equiv | Y equiv | Solvent | (M) | Temp. (°C) | Time (h) | Yield (%) a | ||

| 2a | 3a | 1aa | |||||||

| 1 | 10 | 1.0 | ethanol | 1.0 | 70 | 48 | 20 | 17 | 82 |

| 2 | 10 | 1.0 | − | − | 70 | 24 | N.D b | N.D b | ≥99 |

| 3 | 10 | 1.0 | ethanol | 1.0 | 100 | 24 | 85 | 81 | 17 |

| 4 | 10 | 1.0 | hexafluoroisopropanol | 1.0 | 100 | 24 | 82 | 82 | 18 |

| 5 | 10 | 1.0 | trifluoroethanol | 1.0 | 100 | 24 | 93 | 93 | 7 |

| 6 | 10 | − | trifluoroethanol | 1.0 | 100 | 24 | 52 | 53 | 48 |

| 7 | 10 | 2.0 | trifluoroethanol | 1.0 | 100 | 24 | 69 | 67 | 32 |

| 8 | 10 | 1.0 c | trifluoroethanol | 1.0 | 100 | 24 | 57 | 60 | 42 |

| 9 | − | 1.0 | trifluoroethanol | 1.0 | 100 | 24 | N.D b | N.D b | ≥99 |

| 10 | 20 | 1.0 | trifluoroethanol | 1.0 | 100 | 24 | ≥99 | ≥99 | N.D b |

| 11 | 2.0 | 1.0 | trifluoroethanol | 1.0 | 100 | 24 | 15 | 14 | 85 |

| 12 | 10 | 1.0 | trifluoroethanol | 0.5 | 100 | 24 | 66 | 67 | 33 |

| 13 | 10 | 1.0 | trifluoroethanol | 1.4 | 100 | 24 | 78 | 78 | 22 |

| 14 | 10 | 1.0 | trifluoroethanol | 2.0 | 100 | 24 | 76 | 76 | 24 |

Determined by 19F NMR analysis of the crude mixture using 4-(trifluoromethoxy)anisole (0.1 mmol) as an internal standard.

Not detected.

NH4OAc was used instead of NH4I.

2.1.2 Additive compounds A0–A26 for FGE kit

After determining the optimized reaction conditions (Table 1, Entry 5), we applied the FGE kit to the reaction. Additive compounds A0–A26 for our FGE kit contain the 4-chlorophenyl moiety as the parent backbone to facilitate 1H NMR monitoring of the remaining additives (See Table 2). Because of its UV absorption, the 4-chlorophenyl moiety also enables HPLC analysis of the remaining additives. Furthermore, the isotopic distribution of the chlorine atoms facilitates the detection of chlorine-containing additive molecules as well as side products associated with the additives using mass spectroscopic analysis. We selected 26 functional groups found in many organic molecules, including amino acid residues such as the nitrogen-containing heterocycles imidazole A7 and indole A22.

TABLE 2.

Experimental results for hydrazinolysis of amides using FGE kit.

|

Determined by 19F NMR analysis of the crude mixture using 4-(trifluoromethoxy)anisole (0.1 mmol) as an internal standard.

Standard error.

Determined by 1H NMR analysis of the mixture using 4-(trifluoromethoxy)anisole (0.1 mmol) as an internal standard.

n = 5.

n = 4.

2.1.3 Control experiment with additive A0

Before starting the evaluation with the FGE kit, it was necessary to check whether the 4-chlorophenyl structure in the additive affects the reaction. Therefore, a control experiment was carried out by adding 1.0 equiv of additive A0 (1-butyl-4-chlorobenzene), which does not contain an additional functional group, to the amide bond cleavage reaction. Another objective of the control experiment with additive A0 was to check for reproducibility using the criterion of the standard deviation (σ) of the product yield (%) within 5 (σ ≤ 5) in five experiments (n = 5). Detailed experimental methods for using the FGE kit are reported in our previous work (Saito et al., 2023) (See Supplementary Material for detailed information).

Under optimized reaction conditions, the reaction was carried out five times with 1.0 equiv of additive A0 (Figure 1). The average yield decreased to 73% due to the decrease in the concentration caused by the addition of A0. Therefore, evaluation of the additive effect using A1–A26 is based on this yield. The standard deviation of the yield (%) was 0.97, suggesting that sufficient reproducibility could be obtained even under the conditions with additives. No decreases in the remaining additive (%) were observed (97%), and high reproducibility was obtained with a standard deviation of 2.52, indicating that the 4-chlorophenyl structure is tolerant to the reaction conditions (Supplementary Table S1).

FIGURE 1.

Reaction with additive A0. aDetermined by 19F NMR analysis of the crude mixture using 4-(trifluoromethoxy)anisole (0.1 mmol) as an internal standard. bThe amount of additives were calculated by 1H NMR analysis of the crude mixture using 4-(trifluoromethoxy)anisole (0.1 mmol) as an internal standard.

2.1.4 Evaluation functional group compatibility with additive A1–A26

After fulfilling the reproducibility criteria of additive A0, we examined the additive effects of the other additives, A1–A26, in the FGE kit. Each additive was subjected to an F-test through duplicate experiments (n = 2). Only when the F-test indicated that the variance differed and the variability was too high, two additional experiments with the same additives were performed. The following symbols are used in the experimental results (Figure 2; Table 2). The blue plus sign (+) indicates a statistically significant increase effect. The green plus/minus sign (±) indicates no statistically significant effect, but a result that was comparable to that of the control experiment. The yellow dash sign (−) indicates a statistically significantly decrease effect. When there was a significant decrease of more than half compared with the control experiment, a red “X” was used. Significant differences were determined by a t-test.

FIGURE 2.

The symbols in FGE kit.

The effects of 26 additives A1–A26 in the FGE kit were examined using General Procedure B (Table 2) (See Supplementary Material). Additives A2, A7–A9, A12, A19, A22, A23, and A26 with alcohol, imidazole, aryl bromide, iodide, silyl ether, thiol, indole, primary amine, thioester moieties had no effect on product yield nor remaining additives. It is particularly important that highly reactive thiol A19 and thioether A26, as well as N-unprotected imidazole A7 and indole A22, were tolerated. Additives A5, A6, A10, A11, A15, A18, A21 and A24 with aldehyde, primary amine, terminal alkene, alkyne, enone, nitrile, guanidine and ester moieties did not affect the product yields, but the remaining additives were decreased, suggesting that the functional groups of these additives reacted under the reaction conditions (vide infra). In the case of additives A3 and A14 with aryl chloride and epoxide moieties, the yield of the product slightly increased and the remaining additive was unchanged. On the other hand, additives A1 and A17 with carboxylic acid moieties provided significantly higher product yields than the control reaction with additive A0 although the remaining additives were decreased due to the formation of byproducts (vide infra). For additives A4, A13 and A16 with alkyl ketone, naphthol and aryl ketone moieties, both the yield of the product and the remaining additive were decreased. The addition of A20 and A25 with Bpin and Boc-protected amine moieties decreased the product yields but did not change the remaining additives.

The decrease in the remaining additives was mainly due to the formation of the corresponding byproducts by a competitive reaction between the additives and hydrazine. The byproducts that formed from the additives were either isolated from the crude mixture or, if difficult to isolate, synthesized by methods reported in the literature, and their structures were confirmed using NMR and mass spectrometry analysis (See Supplementary Material).

As expected, carboxyl groups in additives A1 and A17, the amide group in additive A6, and the ester group in additive A24 reacted with hydrazine to afford the corresponding acyl hydrazides such as B1.

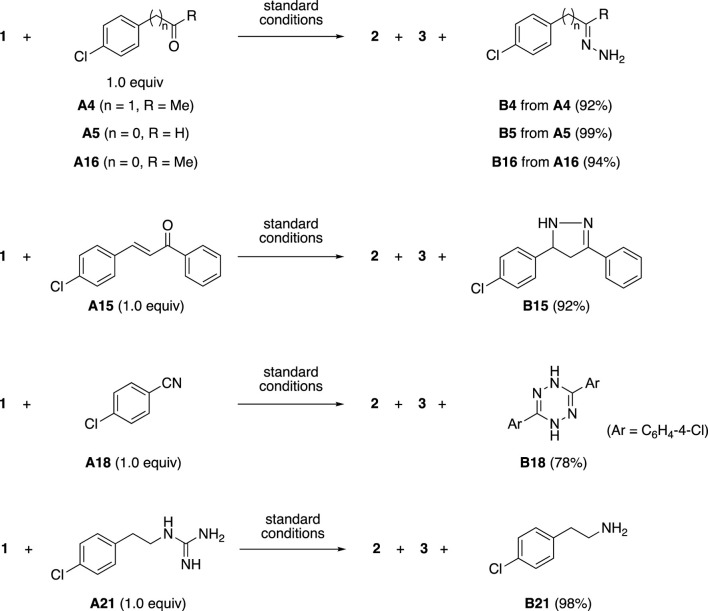

The carbonyl groups in additive A4, A5, and A16 also reacted with hydrazine to form the corresponding hydrazones such as B4, B5, and B16 (Scheme 2). Additive A15 with an enone moiety and additive A18 with a nitrile moiety also reacted with hydrazine to give nitrogen-containing heterocycles pyrazoline B15 and tetrazine B18 in good yields. On the other hand, some unexpected reactions were also observed. Additive A21 with a guanidine moiety reacted with hydrazine to give amine B21.

SCHEME 2.

Formation of byproducts derived from additives A4, A5, A15, A16, A18 and A21.

In the reactions using additives A10 and A11 containing terminal alkene and alkyne, a partial reduction proceeded to produce alkane B10 and alkene A10 (Scheme 3). This type of reduction of olefins by hydrazine was reported by Imada et al., where hydrazine was in situ-oxidized to diimide and the reduction was promoted by Brønsted acids (Arakawa et al., 2017). Surprisingly, the phenolic hydroxyl group and Ar-Cl moiety in additive A13 were converted to amino groups to give naphthalene-1,4-diamine (B13). The discovery of these unexpected reactions is an advantage of using the FGE kit.

SCHEME 3.

Formation of byproducts derived from additives A10, A11, and A13.

Functional group compatibility of a reaction is evaluated from two aspects: the effect of the functionalized additive on the product yield and the remaining additive. The two-dimensional plot in Figure 3 shows the degree of the functional group compatibility for each reaction at a glance. In this plot, dots positioned near additive A0 (red dot in the plot) indicate that the functional groups in the corresponding additive are tolerant in this reaction. On the other hand, dots father away from additive A0 suggest that the reaction is significantly (often negatively) affected by the presence of the functional groups in the additives. This plot clearly shows that under the conditions of this amide bond cleavage reaction, although some functional groups reacted (reducing the recovery of the additive), many functional groups did not inhibit the reaction itself (reducing the yield). In addition, there are many additives with positive effects, and additives A1 and A17 with a carboxyl group significantly increased the product yield.

FIGURE 3.

Two-dimensional representations of the product yield (%) and remaining additives (%).

2.2 Acidic additives for accelerating the amide bond cleavage reaction

Because the above results suggested that carboxyl groups accelerate the ammonium salt-promoted amide bond cleavage reaction, we next examined various acidic additives.

2.2.1 Screening of Brønsted acid additives

Carboxylic acids are easy to handle and often inexpensive (Gooßen et al., 2008; Pichette Drapeau and Gooßen, 2016). Therefore, even if the amide bond cleavage reaction requires an equivalent amount of additive, the carboxylic acid addition conditions can be a useful reaction system.

First, we screened various inorganic and organic Brønsted acids as additives using General Procedure B (See Supplementary Material). To evaluate the additive effects on the reaction rate, product yields were examined for 6 h during the course of the reaction. The use of inorganic acids C1–C3 significantly decelerated the reactions (Table 3). Next, we examined a wide variety of mono-carboxylic acids C4–C34 including A1 and A17 as additives to evaluate changes in the product yield. Overall, aliphatic or aromatic carboxylic acids were not very important, and the correlation between the electrical effects and reactivity was low. On the other hand, it is important to have a certain molecular size, and carboxylic acids, especially those with aromatic rings such as benzene rings, exhibited a good tendency. Ortho-substituted Benzoic acids C16–C18 and C26 were expected to have excellent effects because their carboxylic acid moieties did not react with hydrazine due to steric hindrance. They, however, did not significantly impact the product yields, suggesting that carboxylic acids without steric hindrance should be considered as additives to accelerate the reaction. The acceleration effect of heterocyclic rings is low (C29–C34). The presence of hydroxyl (C8 and C22) and amino (C7) groups in the vicinity of carboxylic acids was not desirable, and dicarboxylic and tricarboxylic acids (C34–C42) rather inhibited the reaction. Other types of acidic compounds, 4-toluenesulfonic acid (C41) and BINOL (C42), were also ineffective. Based on this screening study, we concluded that 4-butyl benzoic acid (C19) and 2-naphthoic acid (C27) were the most effective additives for the amide bond cleavage reaction.

TABLE 3.

Screening of Brønsted acid additives.

|

Determined by 19F NMR analysis of the mixture using 4-(trifluoromethoxy)anisole (0.1 mmol) as an internal standard.

2.2.2 Control experiments between carboxylic acid and hydrazide

As mentioned above, although several carboxylic acids had positive additive effects, the carboxyl groups reacted with hydrazine to form the corresponding hydrazide (Scheme 4). Therefore, control experiments between carboxylic acids and hydrazides were performed to determine whether the positive effect was due to the carboxylic acid or the in situ-formed hydrazide.

SCHEME 4.

Formation of byproducts derived from additives A1, A17, A6 and A24.

We selected benzoic acid (C14) and 4-chlorobenzoic acid (A17) as representative carboxylic acids, and the corresponding hydrazides were synthesized to study their effects. As shown in Table 4, the addition of hydrazides had lower effects (Entries 4 and 7) than carboxylic acids (Entries 2 and 5). Furthermore, the addition of equal amounts of carboxylic acid and hydrazide gave intermediate-level results (Entries 3 and 6). These results clearly suggest that carboxylic acids accelerated the amide bond cleavage reaction, not hydrazides.

TABLE 4.

Comparison of carboxylic acids and hydrazides.

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Additive | X equiv/Y equiv | Yield of 2a (%) a |

| 1 | none | − | 37 |

| 2 | benzoic acid | 1.0 | 59 |

| 3 | benzoic acid/benzohydrazide | 0.5/0.5 | 48 |

| 4 | benzohydrazide | 1.0 | 38 |

| 5 | 4-chlorobenzoic acid | 1.0 | 59 |

| 6 | 4-chlorobenzoic acid/4-chlorobenzohydrazide | 0.5/0.5 | 44 |

| 7 | 4-chlorobenzohydrazide | 1.0 | 43 |

Determined by 19F NMR analysis of the crude mixture using 4-(trifluoromethoxy)anisole (0.1 mmol) as an internal standard.

2.2.3 Lewis acid additives for accelerating the amide bond cleavage reaction

Because carboxylic acids are gradually converted to less effective hydrazides under the reaction conditions, we next examined Lewis acids as additives. Some Lewis acids are reported to accelerate C–H/C–C/C–O/C–N bond cleavage reactions and improve reaction efficiencies (Kita et al., 2013; Baglia et al., 2016; Gao et al., 2021).

In fact, the addition of 1.0 equiv of Zn(OTf)2 greatly accelerated the reaction, increasing the yield of 2a from 37% to 91% under the conditions shown in Supplementary Table S9. Furthermore, when the amount of Lewis acid was reduced to 0.1 equiv, the additive effect was maintained, although the yield was reduced to 66% (Table 5, Entry 9). In this case, no products other than the substrate 1aa and the target products 2a and 3a were observed.

TABLE 5.

Screening of Lewis acid catalysts.

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Lewis acid | Yield of 2a (%) a | Entry | Lewis acid | Yield of 2a (%) a |

| 1 | none | 37 | 11 | AgOTf | 27 |

| 2 | CuBr | 20 | 12 | Cu(OTf)2 | 28 |

| 3 | CuBr2 | 27 | 13 | Ni(OTf)2 | 51 |

| 4 | CuCl2 | 28 | 14 | Co(OTf)2 | 48 |

| 5 | PdCl2 | 34 | 15 | Fe(OTf)3 | 63 |

| 6 | Zn(OAc)2 | 52 | 16 | Fe(OTf)3 b | 38 |

| 7 | Cu(OAc)2 | 28 | 17 | Sc(OTf)3 | 36 |

| 8 | Pd(OAc)2 | 32 | 18 | Y(OTf)3 | 42 |

| 9 | Zn(OTf)2 | 66 | 19 | Yb(OTf)3 | 41 |

| 10 | Zn(OTf)2 b | 89 | 20 | La(OTf)3 | 32 |

| 21 | Bi(OTf)3 | 34 | |||

Determined by 19F NMR analysis of the crude mixture using 4-(trifluoromethoxy)anisole (0.1 mmol) as an internal standard. bWithout addition of NH4I.

We then screened various Lewis acid catalysts for the amide bond cleavage reaction using General Procedure B (Table 5) (See Supplementary Material). Although many Lewis acids showed no positive effects, a catalytic amount of Fe(OTf)3 along with Zn(OTf)2 efficiently accelerated the amide bond cleavage reactions and increased the yield of product 2a (Entry 15). Furthermore, in the case of Zn(OTf)2, the reaction was accelerated more efficiently in the absence of ammonium iodide (Entry 10). On the other hand, in the case of Fe, no acceleration effect was observed under conditions without NH4I (Entry 16).

2.2.4 Scope of amide substrates with acidic additive/catalyst

Finally, with the optimized activation systems using carboxylic acids C19 and C27 (1.0 equiv) and Lewis acid catalysts Fe(OTf)3 and Zn(OTf)2 (0.1 equiv) in hand, the substrate generality of amide was examined using General Procedure B (Table 6) (See Supplementary Material).

TABLE 6.

Substrate scope of amides with acidic additive/catalyst.

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amide | none | C19 | C27 | Fe(OTf)3 | Zn(OTf)2 | Zn(OTf)2 without NH4I |

1ba b |

69% | 73% | 70% | 63% | 67% | 45% |

| 83% (12 h) | 91% (12 h) | 88% (12 h) | 84% (12 h) | |||

1bb |

40% | 71% | 76% | 40% | 51% | 76% |

| 67% (12 h) | >99% (12 h) | 93% (12 h) | 90% (12 h) | |||

1bc |

39% | 53% | 55% | 44% | 45% | 77% |

| 67% (12 h) | 76% (12 h) | 76% (12 h) | 87% (12 h) | |||

| >99% (24 h) | >99% (24 h) | >99% (24 h) | ||||

1bd |

42% | 51% | 56% | 62% | 50% | 38% |

| 67% (12 h) | >99% (24 h) | >99% (24 h) | 79% (24 h) | 82% (24 h) | ||

1be b |

30% | 57% | 54% | 53% | 76% | >99% |

| 54% (12 h) | 80% (12 h) | 82% (12 h) | ||||

| >99% (24 h) | ||||||

Determined by 1H NMR analysis of the mixture using an internal standard.

At 90 °C.

We found that the additives also had a reaction-accelerating effect on other amide substrates. Again, to clarity the differences in the effects of these four systems, the results are shown for a reaction time of 6 h before the reaction is complete. Although the degree of effectiveness of each system varied depending on the substrates, in all cases the addition of 1.0 equiv of carboxylic acid was effective. In the case of 8-aminoquinoline amide 1be, a highly effective and frequently used directing group amide, the system using a zinc catalyst without the addition of NH4I showed drastic acceleration effects, increasing the yield from 30% to 99% at 6 h. With acidic additives/catalysts, the reactions using amides 1bb–1bf were almost completed by prolonging the reaction time. The addition of carboxylic or Lewis acids to the amide bond cleavage reaction is expected to be useful for cleavage of less reactive amide bonds.

3 Conclusion

In conclusion, we evaluated functional group compatibility in amide bond cleavage reactions using the FGE kit, which allows for accurate and rapid assessment of functional group compatibility using 26 FGE compounds with different functional groups. Except for some functional groups that react with hydrazine, we found many functional groups that are compatible. These evaluation experiments revealed that an unprecedented substitution reaction of additive A13 with phenolic hydroxyl group proceeded. Moreover, carboxylic acids were discovered to accelerate the reaction, leading to the development of a new catalytic amide bond cleavage reaction with Zn(OTf)2. These results revealed the clear advantage of the FGE kit for both collecting data that can be applied for machine learning and discovering seeds for the development of new reactions.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Taro Tsuji, Shunsuke Kataoka, Asuka Kudo, and Yunosuke Koga for synthesizing additive compounds and Prof. Nobuyuki Mase and his students at Shizuoka University for synthesizing the compounds A10, A11 and A25 in the FGE kit by flow reaction system. We also thank Yumiko Hirakawa for her management and operation of the FGE kit.

Funding Statement

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Transformative Research Areas (A) Digitalization-driven Transformative Organic Synthesis (Digi-TOS) (MEXT KAKENHI Grant JP21A204, JP21H05207, and JP21H05208) from MEXT, and Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B) (JSPS KAKENHI Grant JP17H03972 and JP21H02607 to TO) and (C) (JSPS KAKENHI Grant JP21K06477 to HM) from JSPS, Basis for Supporting Innovative Drug Discovery and Life Science Research (BINDS) (AMED Grant Numbers JP21am0101091 and JP22ama121031) from AMED. JC thanks the Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST) SPRING (JPMJSP2136).

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusion of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

JC: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Validation, Visualization, Writing–original draft, Writing–review and editing. AN: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Validation, Writing–review and editing. NS: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Validation, Writing–review and editing. YK: Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing–review and editing. HM: Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing–review and editing. TO: Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Visualization, Writing–original draft, Writing–review and editing.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fchem.2024.1378746/full#supplementary-material

References

- Arakawa Y., Kohda T., Minagawa K., Imada Y. (2017). Brønsted acid catalysed aerobic reduction of olefins by diimide generated in situ from hydrazine. SynOpen 1 (01), 11–14. 10.1055/s-0036-1588790 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baglia R. A., Krest C. M., Yang T., Leeladee P., Goldberg D. P. (2016). High-valent manganese–oxo valence tautomers and the influence of lewis/bronsted acids on C–H bond cleavage. Inorg. Chem. 55 (20), 10800–10809. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.6b02109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai Z., Zheng S., Bai Z., Song F., Wang H., Peng Q., et al. (2019). Palladium-catalyzed amide-directed enantioselective carboboration of unactivated alkenes using a chiral monodentate oxazoline ligand. ACS Catal. 9 (7), 6502–6509. 10.1021/acscatal.9b01350 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bautista J. A., Connors R. E., Raju B. B., Hiller R. G., Sharples F. P., Gosztola D., et al. (1999). Excited state properties of peridinin: observation of a solvent dependence of the lowest excited singlet state lifetime and spectral behavior unique among carotenoids. J. Phys. Chem. B 103 (41), 8751–8758. 10.1021/jp9916135 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya T., Ghosh A., Maiti D. (2021). Hexafluoroisopropanol: the magical solvent for Pd-catalyzed C–H activation. Chem. Sci. 12 (11), 3857–3870. 10.1039/D0SC06937J [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown D. G., Bostrom J. (2016). Analysis of past and present synthetic methodologies on medicinal chemistry: where have all the new reactions gone? Miniperspective. J. Med. Chem. 59 (10), 4443–4458. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhari M. B., Gnanaprakasam B. (2019). Recent advances in the metal‐catalyzed activation of amide bonds. Chemistry–An Asian J. 14 (1), 76–93. 10.1002/asia.201801317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins K. D., Glorius F. (2013). A robustness screen for the rapid assessment of chemical reactions. Nat. Chem. 5 (7), 597–601. 10.1038/NCHEM.1669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai X., De Mesmaeker A., Joyce G. F. (1995). Cleavage of an amide bond by a ribozyme. Science 267 (5195), 237–240. 10.1126/science.7809628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreos R., Geremia S., Randaccio L., Siega P. (2011). The chemistry of amidines and imidates (Patai's Chemistry of Functional Groups). Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Ertl P. (2017). An algorithm to identify functional groups in organic molecules. J. cheminformatics 9 (1), 36–37. 10.1186/s13321-017-0225-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao H., Hu L., Hu Y., Lv X., Wu Y. B., Lu G. (2021). Origins of Lewis acid acceleration in nickel-catalysed C–H, C–C and C–O bond cleavage. Catal. Sci. Technol. 11 (13), 4417–4428. 10.1039/D1CY00660F [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gooßen L. J., Rodríguez N., Gooßen K. (2008). Carboxylic acids as substrates in homogeneous catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 47 (17), 3100–3120. 10.1002/anie.200704782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabi A. K., Gujjarappa R., Vodnala N., Kaldhi D., Tyagi U., Mukherjee K. etal (2020). HFIP-mediated strategy towards β-oxo amides and subsequent Friedel-Craft type cyclization to 2‑quinolinones using recyclable catalyst. Tetrahedron Lett. 61 (46), 152535. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2020.152535 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kashima C., Harada H., Kita I., Fukuchi I., Hosomi A. (1994). The preparation of N-acylpyrazoles and their behavior toward alcohols. Synthesis 1994 (01), 61–65. 10.1055/s-1994-25406 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaspar A. A., Reichert J. M. (2013). Future directions for peptide therapeutics development. Drug Discov. today 18 (17-18), 807–817. 10.1016/j.drudis.2013.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemnitz C. R., Loewen M. J. (2007). “Amide resonance” correlates with a breadth of C− N rotation barriers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129 (9), 2521–2528. 10.1021/ja0663024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kita Y., Nishii Y., Onoue A., Mashima K. (2013). Combined catalytic system of scandium triflate and boronic ester for amide bond cleavage. Adv. Synthesis Catal. 355 (17), 3391–3395. 10.1002/adsc.201300819 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar D., Sharma H., Saha N., Chakraborti A. K. (2022). Domino synthesis of functionalized pyridine carboxylates under gallium catalysis: unravelling the reaction pathway and the role of the nitrogen source counter anion. Chem. – Asian J. 17 (15), e202200304. 10.1002/asia.202200304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G., Szostak M. (2020). Transition‐metal‐free activation of amides by N− C bond cleavage. Chem. Rec. 20 (7), 649–659. 10.1002/tcr.201900072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lv C., Zhao R., Wang X., Liu D., Muschin T., Sun Z., et al. (2023). Copper-catalyzed transamidation of unactivated secondary amides via C–H and C–N bond simultaneous activations. J. Org. Chem. 88 (4), 2140–2157. 10.1021/acs.joc.2c02551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maegawa Y., Ohshima T., Hayashi Y., Agura K., Iwasaki T., Mashima K. (2011). Additive effect of N-heteroaromatics on transesterification catalyzed by tetranuclear zinc cluster. ACS Catal. 1 (10), 1178–1182. 10.1021/cs200224b [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mahesh S., Tang K. C., Raj M. (2018). Amide bond activation of biological molecules. Molecules 23 (10), 2615. 10.3390/molecules23102615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikulak-Klucznik B., Gołębiowska P., Bayly A. A., Popik O., Klucznik T., Szymkuć S., et al. (2020). Computational planning of the synthesis of complex natural products. Nature 588 (7836), 83–88. 10.1038/s41586-020-2855-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noshita M., Shimizu Y., Morimoto H., Akai S., Hamashima Y., Ohneda N., et al. (2019). Ammonium salt-accelerated hydrazinolysis of unactivated amides: mechanistic investigation and application to a microwave flow process. Org. Process Res. Dev. 23 (4), 588–594. 10.1021/acs.oprd.8b00424 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pattabiraman V. R., Bode J. W. (2011). Rethinking amide bond synthesis. Nature 480 (7378), 471–479. 10.1038/nature10702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pichette Drapeau M., Gooßen L. J. (2016). Carboxylic acids as directing groups for C− H bond functionalization. Chemistry–A Eur. J. 22 (52), 18654–18677. 10.1002/chem.201603263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rashed M. N., Siddiki S. H., Touchy A. S., Jamil M. A., Poly S. S., Toyao T., et al. (2019). Direct phenolysis reactions of unactivated amides into phenolic esters promoted by a heterogeneous CeO2 catalyst. Chemistry–A Eur. J. 25 (45), 10594–10605. 10.1002/chem.201901446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito N., Nawachi A., Kondo Y., Choi J., Morimoto H., Ohshima T. (2023). Functional group evaluation kit for digitalization of information on the functional group compatibility and chemoselectivity of organic reactions. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 96 (5), 465–474. 10.1246/bcsj.20230047 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu Y., Morimoto H., Zhang M., Ohshima T. (2012). Microwave‐assisted deacylation of unactivated amides using ammonium‐salt‐accelerated transamidation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51 (34), 8564–8567. 10.1002/anie.201202354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu Y., Noshita M., Mukai Y., Morimoto H., Ohshima T. (2014). Cleavage of unactivated amide bonds by ammonium salt-accelerated hydrazinolysis. Chem. Commun. 50 (84), 12623–12625. 10.1039/C4CC02014F [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smithrud D. B., Sanford E. M., Chao I., Ferguson S. B., Carcanague D. R., Evanseck J. D., et al. (1990). Solvent effects in molecular recognition. Pure Appl. Chem. 62 (12), 2227–2236. 10.1351/pac199062122227 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thorner J., Emr S. D., Abelson J. N. (2000). Applications of chimeric genes and hybrid proteins, Part A: gene expression and protein purification (San Diego, USA: Academic Press; ). [Google Scholar]

- Wang B., Cao Z. (2011). Acid-catalyzed reactions of twisted amides in water solution: competition between hydration and hydrolysis. Chemistry–A Eur. J. 17 (42), 11919–11929. 10.1002/chem.201101274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z., Liu C., Zhang Z., Zheng R., Zheng Y. (2020). Amidase as a versatile tool in amide-bond cleavage: from molecular features to biotechnological applications. Biotechnol. Adv. 43, 107574. 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2020.107574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S. Q., Xu L. C., Li S. W., Oliveira J. C., Li X., Ackermann L., et al. (2023). Bridging chemical knowledge and machine learning for performance prediction of organic synthesis. Chemistry–A Eur. J. 29 (6), e202202834. 10.1002/chem.202202834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z., Zheng D., Wan Y., Zhang G., Bi J., Liu Q., et al. (2018). Selective cleavage of inert aryl C–N bonds in N-aryl amides. J. Org. Chem. 83 (3), 1369–1376. 10.1021/acs.joc.7b02880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusion of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.