Abstract

STUDY QUESTION

Is preconception depression associated with time to pregnancy (TTP) and infertility?

SUMMARY ANSWER

Couples with preconception depression needed a longer time to become pregnant and exhibited an increased risk of infertility.

WHAT IS KNOWN ALREADY

Preconception depression in women contributes to impaired fertility in clinical populations. However, evidence from the general population—especially based on couples—is relatively scant.

STUDY DESIGN, SIZE, DURATION

A couple-based prospective preconception cohort study was performed in 16 premarital examination centers between April 2019 and June 2021. The final analysis included 16 521 couples who tried to conceive for ≤6 months at enrollment. Patients with infertility were defined as those with a TTP ≥12 months and those who conceived through ART.

PARTICIPANTS/MATERIALS, SETTING, METHODS

Couples’ depression was assessed using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 at baseline. Reproductive outcomes were obtained via telephone at 6 and 12 months after enrollment. Fertility odds ratios (FORs) and infertility risk ratios (RRs) in different preconception depression groups were analyzed using the Cox proportional-hazard models and logistic regression, respectively.

MAIN RESULTS AND THE ROLE OF CHANCE

Of the 16 521 couples analyzed, 10 834 (65.6%) and 746 (4.5%) couples achieved pregnancy within the first 6 months and between the 6th and 12th months, respectively. The median (P25, P75) TTP was 3.0 (2.0, 6.0) months. The infertility rate was 13.01%. After adjusting for potential confounders, in the individual-specific analyses, we found that preconception depression in women was significantly related to reduced odds of fertility (FOR = 0.947, 95% CI: 0.908–0.988), and preconception depression in either men or women was associated with an increased risk of infertility (women: RR = 1.212, 95% CI: 1.076–1.366; men: RR = 1.214, 95% CI: 1.068–1.381); in the couple-based analyses, we found that—compared to couples where neither partner had depression—the couples where both partners had depression exhibited reduced fertility (adjusted FOR = 0.904, 95% CI: 0.838–0.975). The risk of infertility in the group where only the woman had depression and both partners had depression increased by 17.8% (RR = 1.178, 95% CI: 1.026–1.353) and 46.9% (RR = 1.469, 95% CI: 1.203–1.793), respectively.

LIMITATIONS, REASONS FOR CAUTION

Reporting and recall bias were unavoidable in this large epidemiological study. Some residual confounding factors—such as the use of anti-depressants and other medications, sexual habits, and prior depressive and anxiety symptoms—remain unaddressed. We used a cut-off score of 5 to define depression, which is lower than prior studies. Finally, we assessed depression only at baseline, therefore we could not detect effects of temporal changes in depression on fertility.

WIDER IMPLICATIONS OF THE FINDINGS

This couple-based study indicated that preconception depression in individuals and couples negatively impacts couples’ fertility. Early detection and intervention of depression to improve fertility should focus on both sexes.

STUDY FUNDING/COMPETING INTEREST(S)

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82273638) and the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2018YFC1004201). All authors declare no conflicts of interest.

TRIAL REGISTRATION NUMBER

N/A.

Keywords: depression, infertility, time to pregnancy, couple, conception, cohort

WHAT DOES THIS MEAN FOR PATIENTS?

Studies have demonstrated that depressive symptoms in either women or men are associated with decreased fertility in the clinical population. However, these conclusions are challenging to extrapolate to the general population. Additionally, few studies have explored the combined effects of depressive symptoms in men and women on couples’ fertility. Therefore, this study used a community-based cohort of 16 521 couples trying to conceive to explore the individual and combined effects of depressive symptoms in men and women on time to pregnancy (TTP) and infertility. The results revealed that, irrespective of the other partner’s depressive symptoms, preconception depression in either men or women was associated with an increased risk of infertility, and preconception depression in women was associated with a longer TTP. When considering the other partner’s depressive symptoms, compared to couples where neither partner had depression, couples where both partners had depression needed a longer time to become pregnant, and couples where both partners or only the woman had depression exhibited an increased risk of infertility; however, the associations between depression and TTP and infertility were not observed in couples where only the man had depression. For patients and policymakers, these results support that screening for depression in couples who are actively preparing for pregnancy and providing psychological intervention for those with positive screening results are important. These measures will help reduce the TTP and incidence of infertility, especially for couples where both men and women suffer from depression and women are under 30 years old.

Introduction

Infertility—defined as the failure to establish a clinical pregnancy after 12 months of regular and unprotected sexual intercourse—is estimated to affect 8–12% of reproductive-aged couples worldwide (Vander Borght and Wyns, 2018). Infertility harms the physical and mental health of couples attempting to conceive (Shani et al., 2016; Salih Joelsson et al., 2017; Dokras et al., 2018) and also contributes to a massive worldwide illness burden (Sun et al., 2019). Despite ART having become more available, effective, and safe in recent years (Bai et al., 2020), the overall clinical pregnancy rate is still low (Chambers et al., 2021). Thus, identifying the risk factors for infertility is of great significance for public health. Recently, some lifestyle factors—such as physical activity, eating habits, and sleep duration—and environmental factors have been found to affect reproductive capacity (Carré et al., 2017; Massányi et al., 2020; Mena et al., 2020; Skoracka et al., 2021; Hernáez et al., 2022; Yao et al., 2022). Additionally, the influence of psychological factors (e.g. depression), which are often intertwined with lifestyle factors, on infertility has been debated for years (Rooney and Domar, 2018; Difrancesco et al., 2019; Vancampfort et al., 2021; Korczak et al., 2022), but the results remain largely inconclusive (Williams et al., 2007).

Depression is a widespread chronic illness characterized by low mood, lack of energy, sadness, insomnia, and anhedonia (Cui, 2015). Estimates suggest that 14% of women suffer from depression during their reproductive years and that women are disproportionately more prone to it than men (Weissman and Olfson, 1995; Smith, 2014). Depressive symptoms may reduce fertility in several ways, such as by disrupting the hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal (HPG) axis, which affects sex hormone production; and by reducing libido, sexual intercourse frequency, and sleep quality (Sansone et al., 2018; Meller et al., 2001; Hernáez et al., 2022; Yao et al., 2022; Zhu et al., 2022). Thus far, numerous studies have explored the relationship between depressive symptoms and fertility. Some cross-sectional studies have suggested that depressive symptoms are more common among couples who are infertile than those who are fertile (Pasch et al., 2016); one study reported that 39.1% of women and 15.3% of men fulfilled the criteria for major depressive disorder during infertility treatment (Holley et al., 2015). According to meta-analytic data from prospective cohort studies, depression and state anxiety scores during ART are associated with poor outcomes (Purewal et al., 2018). In randomized clinical trials of patients with infertility, those who received psychological interventions exhibited greater odds of becoming pregnant than those who did not (control group) (Hämmerli et al., 2009), suggesting that an improvement in mental health is beneficial for enhancing fertility. However, most of these studies were based on couples seeking assisted reproductive assistance, who have already endured a long period of struggling with pregnancy difficulties at the time of their evaluation of depressive symptoms (Williams et al., 2007). Therefore, whether infertility contributes to depression or depression contributes to infertility is unclear.

A growing body of studies has examined the effect of preconception depression on fertility in the non-ART population. However, most of them have measured depression solely in women (Lynch et al., 2012; Nillni et al., 2016), and few studies have considered depression in men in the context of assessing couples’ fertility. Prior research has indicated that depressive symptoms in men are associated with poor semen parameters, including low semen volume, low total sperm count, and low total motility (Yland et al., 2021; Ye et al., 2022), which probably translate into low couple fertility. Thus far, several studies have explored the relationship between depression and fertility in men and women, as well as in couples. However, these analyses solely focused on individuals, not couples, with their results demonstrating considerable heterogeneity. For example, a register-based study of 1 408 951 individuals in Finland found that depression is associated with a lower likelihood of having children and having fewer children, among both men and women (Golovina et al., 2023). However, another national-registry-based study found no link between depression in women and the number of children that they had (Power et al., 2013). In contrast, a prospective cohort study conducted among couples where the woman had been diagnosed with PCOS or unexplained infertility reported that depression is related to slightly decreased odds of pregnancy among men but not women (Evans-Hoeker et al., 2018).

To our knowledge, no study has explored the association between couples’ depression and their fertility. However, couples, as a whole, usually share a common living environment, some lifestyle and health behaviors, and emotions. Research has indicated a significant interdependence between health behaviors and depressive symptoms among partners in a couple (Yang et al., 2023). Depressive symptoms in one partner significantly impact depressive symptoms in the other (Tower and Kasl, 1995), which is also supported by data from our previous study (Gan et al., 2022). However, the ability to conceive depends on the couple, not merely the man or the woman. Thus, it is worthwhile to assess the joint effects of depressive symptoms in both partners to arrive at an improved understanding of depression’s effect on fertility among couples.

In this couple-based prospective cohort study, we examined the effects of couples’ preconception depression on their fertility (time to pregnancy [TTP] and infertility). We aimed to explore: the associations between each partner’s depression and couple fertility; effects of co-exposure to depression among couples on couple fertility; and potential moderating factors of the association between preconception depression and couple fertility. We assessed the participants’ depression during the period of preparing for pregnancy and, subsequently, followed up on their reproductive outcomes, to generate evidence for causal inference of depression on fertility.

Materials and methods

Study design and population

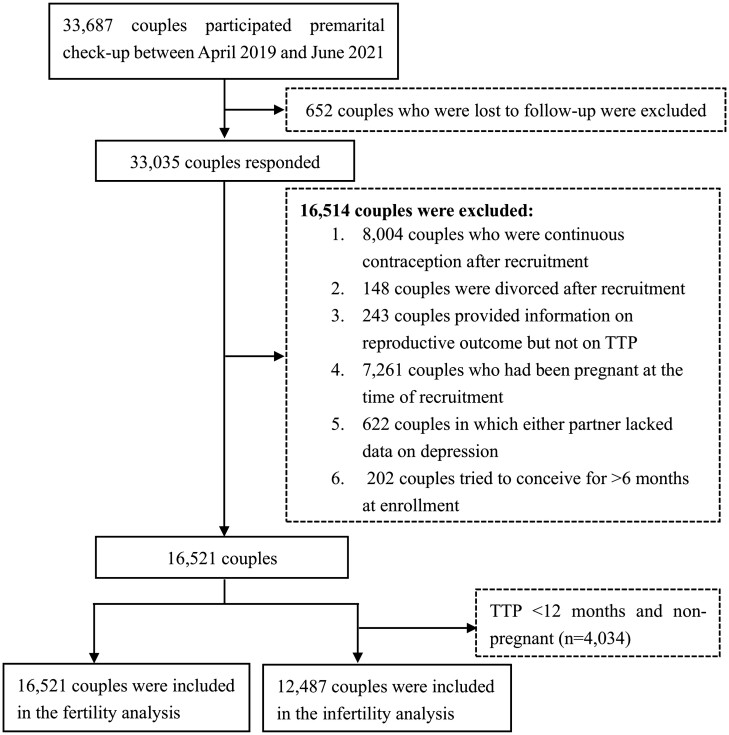

We conducted a couple-based reproduction cohort study by employing the Reproductive Health of Childbearing Couple-Anhui Cohort (RHCC-AC), which aimed to investigate the effect of psychological and environmental factors on fertility among couples of childbearing age. Overall, 33 687 couples were recruited as participants at 16 premarital examination centers in 16 cities/counties in China’s Anhui Province from April 2019 to June 2021. At enrollment, all participants completed a baseline questionnaire including information regarding their demographic characteristics, lifestyle, psychological condition, and diet, and provided their biological samples (e.g. blood, urine). Each couple was followed up by telephone at 6 and 12 months after enrollment to obtain their fertility status. In our study, patients with infertility are defined as those with a TTP ≥12 months and those who conceived through ART. Couples who could not be contacted or refused to respond at each follow-up visit were considered lost to follow-up and were excluded from this study (n = 652). Additionally, 16 514 couples were excluded for other reasons (Fig. 1). Finally, we included 16 521 and 12 487 couples in the fertility and infertility analyses, respectively. Overall, 4034 couples with TTP <12 months and not pregnant were excluded from the infertility analysis.

Figure 1.

Flow chart for the study population to examine the effects of couples’ preconception depression on their fertility. TTP, time to pregnancy.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committees of Anhui Medical University (approval number: 20189999) and was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration. All the participants provided informed consent.

Measures

Depressive symptoms (exposure)

At enrollment, participants filled the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), which has been recommended as a screening measure for depression in primary care (Zimmerman, 2019). It includes nine items that assess the frequency of the corresponding symptoms that they have experienced over the past 2 weeks. Each item is rated on a four-point ordinal scale—specifically, ‘0 = seldom or never’, ‘1 = a few days’, ‘2 = more than half of the days’, and ‘3 = nearly every day’. The total score (ranging from 0–27) of depressive symptoms is computed by summing the ratings on the nine symptom items, with higher scores indicating a greater degree of depressive symptoms. In this study, we defined a PHQ-9 cut-off score of ≥5 as depression, which exhibited a specificity and sensitivity of 0.75 and 0.86, respectively, in primary care (Zuithoff et al., 2010). For the individual-specific analyses, we divided the partners into the following two groups: no-depression; and depression. For the couple-based analyses, we divided the couples into the following four groups: neither partner with depression; man-only depression; woman-only depression; and both partners with depression. The Cronbach’s α-coefficient of the nine items for women and men were 0.807 and 0.800, respectively.

Fertility (outcome)

We used TTP (continuous variable) and infertility (dichotomous variable) as indicators to assess the couples’ fertility. All couples were contacted by the medical staff or researcher at 6 and 12 months after enrollment to obtain information regarding their pregnancy outcome, contraceptive status, and abortion as well as the time of the outcome’s occurrence. The pregnancy outcome was ascertained using a single-choice question, specifically ‘From recruitment to now, have you been pregnant?’ The response alternatives were as follows: ‘1 = Yes’, ‘2 = No’, and ‘3 = Yes but miscarried’. In this study, pregnancy was defined as a clinical pregnancy, which must be confirmed by a pelvic ultrasound scan. For the couples who responded ‘Yes’ or ‘Yes but miscarried’, we further asked the following questions to obtain the TTP: ‘How long (in months) did it take you to become pregnant having regular sex without using any contraception?’ For those who responded ‘No’, we asked the following questions to obtain the TTP: ‘How long have you and your partner been having regular sex without contraception (in months) in order to become pregnant?’ Importantly, the duration of pregnancy attempts before recruitment was also included in calculating the TTP; hence, the TTP may have been greater than 12 months at the 12-month follow-up. The rate of infertility was calculated using the following formula: Rate of infertility = (Number of couples with TTP ≥ 12 months + Number of couples who became pregnant using ART)/(Number of couples finally included in this study−Number of couples with TTP <12 months but not pregnant). Additionally, we collected information regarding conception type (natural pregnancy or ART).

Covariates

Data regarding the following covariates were collected using a standardized questionnaire at baseline: both partners’ age (years), weight (kg), height (cm), education level (≤junior high school, high school or technical secondary school, ≥junior college), individual income (yuan/year), occupation (technical personnel, government official and clerk or enterprise clerk, businessperson, unemployed, manual worker, and others), smoking status (yes or no), drinking status (yes or no), physical activity levels (low, moderate, and high); age of menarche (<13 years or ≥13 years), pregnancy history (have or do not have), live birth history (have or do not have), spontaneous abortion history (have or do not have), stillbirth history (have or do not have), and induced abortion history (have or do not have); and age of first spermatogenesis (<15 years or ≥15 years). The BMI was calculated as weight/height2 (kg/m2). Smoking was defined as consuming at least one cigarette per day during the previous 6 months. Drinking was defined as consuming alcohol at least once during the previous 6 months. Participants’ physical activity level was evaluated based on the International Physical Activity Questionnaire Short Form Scale (Macfarlane et al., 2007).

Statistical analysis

Continuous data were expressed using mean (SD) or median (P25, P75), and categorical data were expressed using frequencies (proportions). Pregnant and non-pregnant groups were compared using the Student’s t-test or Kruskal–Wallis H test for the continuous variables and the chi-square test for the categorical variables.

First, we performed individual-specific analyses to assess the associations between each partner’s depression symptoms and the couple’s fertility. Second, considering the potential impact of shared depression in couples on their fertility, we performed couple-based analyses to assess the effects of co-exposure to depression in couples on fertility.

The probability of pregnancy in each month was estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method; the differences in the probability of pregnancy were evaluated using a log-rank test. Multivariable analyses with discrete time-to-event Cox regression were employed to estimate the fertility odds ratios (FORs) at different preconception depression levels, which are reported here along with their 95% CIs. Notably, FORs <1 indicate a longer time to become pregnant. Logistic regression was employed to estimate the association between depressive levels and infertility (dichotomous variable), with the results reported as risk ratios (RRs) along with their 95% CIs. The above two regression models were conducted in both individual-specific and couple-based analyses. In the individual-specific analysis, for women, data were adjusted for woman’s age, BMI, personal income, education level, occupation, smoking, drinking, physical activity levels, age of menarche, pregnancy history, live birth history, spontaneous abortion history, stillbirth history, and induced abortion history; for men, data were adjusted for man’s age, BMI, personal income, education level, occupation, smoking, drinking, physical activity levels, age of first spermatogenesis, age of first sexual intercourse; and their partner’s pregnancy history, live birth history, spontaneous abortion history, stillbirth history, and induced abortion history. In the couple-based analysis, data were adjusted for each partner’s age, BMI, personal income, education level, occupation, smoking, drinking, physical activity level; woman’s age of menarche, pregnancy history, live birth history, spontaneous abortion history, stillbirth history, and induced abortion history; and man’s age of first spermatogenesis and first sexual intercourse. Notably, we included couples who conceived through ART in the TTP analysis but classified them as the infertility group in the infertility analysis.

Considering that fertility starts dropping in women and men over 30 and 40 years of age, respectively (Schwartz and Mayaux, 1982; de La Rochebrochard et al., 2006), we performed stratified analyses to assess whether the effect of depression on fertility was modified by maternal age (≤30 years or >30 years) and paternal age (<40 years or ≥40 years). Additionally, as maternal and paternal BMI exhibits a strong association with a couple’s fertility (Hernáez et al., 2021), we examined whether the effect of depression on fertility was modified by the BMI for men and women (<18.5, <24.0, and ≥24.0 kg/m2). Moreover, we investigated the modification effects of a woman’s pregnancy history (have or do not have). Finally, we conducted three sensitivity analyses to assess our results’ robustness. First, we reanalyzed the relationship between depression and fertility by excluding the couples who became pregnant through ART. Second, we reanalyzed the relationship between depression and fertility in couples after excluding participants who were infertile owing to specific factors of infertility related to females or males or both, such as azoospermia, asthenospermia, blocked fallopian tubes, and PCOS. Third, the participants were recruited and followed up for over 3 years (2019–2022)—during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. This major public health event might have increased the risk of depression and infertility (COVID-19 Mental Disorders Collaborators, 2021; Somigliana et al., 2021), hence, we conducted a sensitivity analysis among couples who believed that the COVID-19 pandemic did not affect their pregnancy preparedness.

The SPSS (version 23) software (IBM Crop, Armonk, NY, USA) was used to perform the statistical analyses. Finally, α-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant in all statistical tests.

Results

Descriptive analysis

Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of included couples. The average age of women and men were 26.13 ± 3.50 and 27.13 ± 3.45 years, respectively. The women in the non-pregnant group were more likely to be older, be smokers, have a higher BMI, and have lower incomes, and less likely to have a history of spontaneous abortion, induced abortion, or pregnancy. The men in the non-pregnant group were more likely to be older and have an earlier age of first spermatogenesis. As Table 2 indicates, 11 668 (70.6%) couples achieved a pregnancy during the study period. Notably, 10 834 (65.6%) and 746 (4.5%) couples achieved pregnancy within the first 6 months and between the 6th and 12th months, respectively. The median (P25, P75) TTP was 3.0 (2.0, 6.0) months. The infertility rate was 13.01%.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics by pregnancy status based on the follow-up of 12 months (n = 16 521).

| Baseline characteristics | Total (N = 16 521) | Pregnant (N = 11 668) | Non-pregnant (N = 4 853) | z/t/χ2 | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | |||||

| Age (years) | 26.13 ± 3.50 | 25.93 ± 3.35 | 26.61 ± 3.80 | 11.40 | <0.001 |

| Missing (n) | 8 | 4 | 4 | ||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22.20 ± 4.45 | 22.04 ± 4.41 | 22.58 ± 4.53 | 6.97 | <0.001 |

| Missing (n) | 254 | 193 | 61 | ||

| Education level | 0.820 | 0.664 | |||

| ≤ Junior high school | 3920 (23.7) | 2790 (23.9) | 1130 (23.3) | ||

| High school or technical secondary school | 2560 (15.5) | 1798 (15.4) | 762 (15.7) | ||

| ≥ Junior college | 10 041 (60.8) | 7080 (60.7) | 2961 (61.0) | ||

| Individual income (yuan/year) | 14.80 | 0.001 | |||

| <30 000 | 4571 (27.7) | 3234 (27.7) | 1337 (27.5) | ||

| ≥30 000 | 6901 (41.8) | 4965 (42.6) | 1936 (39.9) | ||

| ≥60 000 | 5049 (30.6) | 3469 (29.7) | 1580 (32.6) | ||

| Occupation | 5.57 | 0.233 | |||

| Technical personnel | 2893 (17.8) | 2043 (17.9) | 850 (17.8) | ||

| Government official and clerk or enterprise clerk | 2640 (16.3) | 1843 (16.1) | 797 (16.7) | ||

| Businessman | 5147 (31.8) | 3617 (31.6) | 1530 (32.1) | ||

| Unemployed | 2480 (15.3) | 1797 (15.7) | 683 (14.3) | ||

| Manual worker and other | 3051 (18.8) | 2138 (18.7) | 913 (19.1) | ||

| Missing (n) | 310 | 230 | 80 | ||

| Smoking | 12.28 | <0.001 | |||

| No | 16 114 (97.5) | 11 413 (97.8) | 4701 (96.9) | ||

| Yes | 406 (2.5) | 255 (2.2) | 151 (3.1) | ||

| Missing (n) | 1 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Drinking | 3.535 | 0.060 | |||

| No | 11 682 (72.0) | 8292 (72.5) | 3390 (71.0) | ||

| Yes | 4535 (28.0) | 3151 (27.5) | 1384 (29.0) | ||

| Missing (n) | 304 | 225 | 79 | ||

| Age of menarche (years) | 1.163 | 0.281 | |||

| <13 | 5821 (35.9) | 4077 (35.6) | 1744 (36.5) | ||

| ≥13 | 10 389 (64.1) | 7360 (64.4) | 3029 (63.5) | ||

| Missing (n) | 311 | 231 | 80 | ||

| Physical activity levels | 1.469 | 0.480 | |||

| Low | 9247 (56.2) | 6565 (56.5) | 2682 (55.5) | ||

| Moderate | 5938 (36.1) | 4166 (35.9) | 1772 (36.7) | ||

| High | 1267 (7.7) | 887 (7.6) | 380 (7.9) | ||

| Missing (n) | 69 | 50 | 19 | ||

| History of pregnancy | 8.435 | 0.004 | |||

| Do not have | 12 699 (76.9) | 8897 (76.3) | 3802 (78.3) | ||

| Have | 3822 (23.1) | 2771 (23.7) | 1051 (21.7) | ||

| History of live birth | 0.814 | 0.367 | |||

| Do not have | 15 598 (94.4) | 11 004 (94.3) | 4594 (94.7) | ||

| Have | 923 (5.6) | 664 (5.7) | 259 (5.3) | ||

| History of stillbirth | 0.391 | 0.532 | |||

| Do not have | 16 366 (99.1) | 11 555 (99.0) | 4811 (99.1) | ||

| Have | 155 (0.9) | 113 (1.0) | 42 (0.9) | ||

| History of spontaneous abortion | 23.47 | <0.001 | |||

| Do not have | 15 819 (95.8) | 11 115 (95.3) | 4704 (96.9) | ||

| Have | 702 (4.2) | 553 (4.7) | 149 (3.1) | ||

| History of induced abortion | 6.587 | 0.010 | |||

| Do not have | 14 290 (86.5) | 10 041 (86.1) | 4249 (87.6) | ||

| Have | 2231 (13.5) | 1627 (13.9) | 604 (12.4) | ||

| Men | |||||

| Age (years) | 27.13 ± 3.45 | 26.96 ± 3.35 | 27.52 ± 3.64 | 9.46 | <0.001 |

| Missing (n) | 16 | 12 | 4 | ||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.85 ± 3.65 | 23.83 ± 3.63 | 23.92 ± 3.69 | 1.01 | 0.083 |

| Missing (n) | 257 | 188 | 69 | ||

| Education level | 2.08 | 0.354 | |||

| ≤ Junior high school | 3897 (23.6) | 2758 (23.6) | 1139 (23.5) | ||

| High school or technical secondary school | 3400 (20.6) | 2432 (20.8) | 968 (19.9) | ||

| ≥ Junior college | 9224 (55.8) | 6478 (55.5) | 2746 (56.6) | ||

| Individual income (yuan/year) | 1.67 | 0.434 | |||

| <60 000 | 5085 (30.8) | 3589 (30.8) | 1496 (30.8) | ||

| ≥60 000 | 6833 (41.4) | 4858 (41.6) | 1975 (40.7) | ||

| ≥100 000 | 4603 (27.9) | 3221 (27.6) | 1382 (28.5) | ||

| Occupation | 1.744 | 0.783 | |||

| Technical personnel | 5267 (32.5) | 3720 (32.5) | 1547 (32.4) | ||

| Government official and clerk or enterprise clerk | 1756 (10.8) | 1237 (10.8) | 519 (10.9) | ||

| Businessman | 4244 (26.2) | 2993 (26.2) | 1251 (26.2) | ||

| Unemployed | 558 (3.4) | 407 (3.6) | 151 (3.2) | ||

| Manual worker and other | 4377 (27.0) | 3075 (26.9) | 1302 (27.3) | ||

| Missing (n) | 319 | 236 | 83 | ||

| Smoking | 0.000 | 0.990 | |||

| No | 8438 (51.1) | 5959 (51.1) | 2479 (51.1) | ||

| Yes | 8083 (48.9) | 5709 (48.9) | 2374 (48.9) | ||

| Drinking | 3.483 | 0.062 | |||

| No | 5699 (34.5) | 3973 (34.1) | 1726 (35.6) | ||

| Yes | 10 822 (65.5) | 7695 (65.9) | 3127 (64.4) | ||

| Age of first spermatogenesis (years) | 3.888 | 0.049 | |||

| <15 | 8046 (49.7) | 5620 (49.2) | 2426 (50.9) | ||

| ≥15 | 8156 (50.3) | 5812 (50.8) | 2344 (49.1) | ||

| Missing (n) | 319 | 236 | 83 | ||

| Physical activity levels | 3.944 | 0.139 | |||

| Low | 7086 (43.0) | 4955 (42.6) | 2131 (44.0) | ||

| Moderate | 6601 (40.1) | 4717 (40.6) | 1884 (38.9) | ||

| High | 2784 (16.9) | 1960 (16.9) | 824 (17.0) | ||

| Missing (n) | 50 | 36 | 14 | ||

BMI, body mass index. Numbers in bold in the table indicates statistical significance, with a P-value <0.05. Pregnant and non-pregnant groups were compared using the Student’s t-test or Kruskal–Wallis H test for the continuous variables and the chi-square test for the categorical variables.

Table 2.

The distribution of the cumulative pregnancy rate and median time to pregnancy in different groups.

| N (%) |

Couple |

Men |

Women |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

TTP

(Months) |

Total

(N = 16 521) |

Neither partner with depression (N = 10 230) |

Man-only depression (N = 2130) |

Woman-only depression (N = 3088) |

Both partners with depression (N = 1073) |

No-depression (N = 13 318) |

Depression (N = 3203) |

No-depression (N = 12 360) |

Depression (N = 4161) |

| ≤1 | 3885 (23.5) | 2434 (23.8) | 489 (23.0) | 717 (23.2) | 245 (22.8) | 3151 (23.7) | 734 (22.9) | 2923 (23.6) | 962 (23.1) |

| ≤2 | 6118 (37.0) | 3825 (37.4) | 772 (36.2) | 1126 (36.5) | 395 (36.8) | 4951 (37.2) | 1167 (36.4) | 4597 (37.2) | 1521 (36.6) |

| ≤3 | 8332 (50.4) | 5188 (50.7) | 1070 (50.2) | 1550 (50.2) | 524 (48.8) | 6738 (50.6) | 1594 (49.8) | 6258 (50.6) | 2074 (49.8) |

| ≤4 | 9095 (55.1) | 5676 (55.5) | 1157 (54.3) | 1702 (55.1) | 560 (52.2) | 7378 (55.4) | 1717 (53.6) | 6833 (55.3) | 2262 (54.4) |

| ≤5 | 9621 (58.2) | 6021 (58.9) | 1218 (57.2) | 1783 (57.7) | 599 (55.8) | 7804 (58.6) | 1817 (56.7) | 7239 (58.6) | 2382 (57.2) |

| ≤6 | 10 834 (65.6) | 6790 (66.4) | 1362 (63.9) | 2009 (65.1) | 673 (62.7) | 8799 (66.1) | 2035 (63.5) | 8152 (66.0) | 2682 (64.5) |

| <12 | 11 177 (67.7) | 6988 (68.3) | 1411 (66.2) | 2074 (67.2) | 704 (65.6) | 9062 (68.0) | 2115 (66.0) | 8399 (68.0) | 2778 (66.8) |

| 12 | 11 580 (70.1) | 7206 (70.4) | 1477 (69.3) | 2157 (69.9) | 740 (69.0) | 9363 (70.3) | 2217 (69.2) | 8683 (70.3) | 2897 (69.6) |

| ≤13 | 11 606 (70.2) | 7219 (70.6) | 1480 (69.5) | 2163 (70.0) | 744 (69.3) | 9382 (70.4) | 2224 (69.4) | 8699 (70.4) | 2907 (69.9) |

| ≤15 | 11 639 (70.4) | 7242 (70.8) | 1482 (69.6) | 2169 (70.2) | 746 (69.5) | 9411 (70.6) | 2228 (69.6) | 8724 (70.6) | 2915 (70.1) |

| ≤18 | 11 668 (70.6) | 7257 (70.9) | 1485 (69.7) | 2178 (70.5) | 748 (69.7) | 9435 (70.8) | 2233 (69.7) | 8742 (70.7) | 2926 (70.3) |

| MPT | 3.0 (2.0,6.0) | 3.0 (2.0,6.0) | 3.0 (2.0,7.0) | 3.0 (2.0,7.0) | 3.0 (2.0,9.0) | 3.0 (2.0,6.0) | 3.0 (2.0,8.0) | 3.0 (2.0,6.0) | 3.0 (2.0,8.0) |

| CART | 366 (2.22) | 213 (58.2) | 47 (12.8) | 73 (19.9) | 33 (9.0) | 286 (78.1) | 80 (21.9) | 260 (71.0) | 106 (29.0) |

| <12CART | 315 (1.91) | 186 (59.0) | 43 (13.7) | 59 (18.7) | 27 (8.6) | 245 (77.8) | 70 (22.2) | 229 (72.7) | 86 (27.3) |

| ≥12CART | 51 (0.31) | 27 (52.9) | 4 (7.8) | 14 (27.5) | 6 (11.8) | 41 (80.4) | 10 (19.6) | 31 (60.8) | 20 (39.2) |

| <12 N-P | 4034 (24.12) | 2496 (61.9) | 542 (13.4) | 740 (18.3) | 256 (6.3) | 3236 (80.2) | 798 (19.8) | 3038 (75.3) | 996 (24.7) |

Pregnancy rate presented as N (%). TTP, time to pregnancy; MPT, median time to pregnancy (months); CART, conceived by ART; <12 CART, conceived by ART and with a TTP < 12 months; ≥12 CART, conceived by ART and with a TTP ≥ 12 months; <12 N-P, TTP <12 months and non-pregnant.

Individual-specific analysis of associations between preconception depression and fertility

As Table 2 and Supplementary Fig. S1 indicate, for men, the median (P25, P75) TTP in the no-depression and depression groups was 3.0 (2.0, 6.0) and 3.0 (2.0, 8.0) months, respectively. The overall pregnancy rate in the no-depression group was significantly higher than that in the depression group (log-rank test: P = 0.033). For women, the median (P25, P75) TTP in the no-depression and depression groups was 3.0 (2.0, 6.0) and 3.0 (2.0, 8.0) months, respectively. Additionally, the overall pregnancy rate in the no-depression group was significantly higher than that in the depression group (log-rank test: P = 0.008).

As Fig. 2 indicates, after adjusting for the potential confounders listed in the Materials and methods section, preconception depression in women was significantly related to reduced odds of fertility (FOR = 0.947, 95% CI: 0.908–0.988); and preconception depression in both men and women was significantly associated with an increased risk of infertility (women: RR = 1.212 [95% CI: 1.076–1.366]; men: RR = 1.214 [95% CI: 1.068–1.381]).

Figure 2.

Associations between each partner’s depression and couple fertility. The no-depression group—defined as those with PHQ-9 scores <5—is the reference group. The depression group was defined as those with PHQ-9 scores ≥5. For women, data were adjusted for their age, BMI, personal income, education level, occupation, smoking, drinking, physical activity levels, age of menarche, pregnancy history, live birth history, spontaneous abortion history, stillbirth history, and induced abortion history. For men, data were adjusted for their age, BMI, personal income, education level, occupation, smoking, drinking, physical activity levels, age of first spermatogenesis, age of first sexual intercourse; their partner’s pregnancy history, live birth history, spontaneous abortion history, stillbirth history, and induced abortion history. In the subgroup analyses, data were adjusted for all the other factors, except the stratified factor. FOR, fertility odds ratio; RR, relative risk; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9; BMI, body mass index.

We further estimated the effect of individual preconception depression on couple fertility stratified by the woman’s age (≤30 years or >30 years), BMI (<18.5, <24.0, and ≥24.0 kg/m2), and pregnancy history (have or do not have); and the man’s age (<40 years or ≥40 years) and BMI (<18.5, <24.0, and ≥24.0 kg/m2). The woman’s age modified the associations between depression and couple fertility (P for interaction = 0.019); specifically, depression was significantly associated with reduced fertility in women ≤30 years (FOR = 0.934, 95% CI: 0.894–0.977), but no significant correlation was found between depression and fertility in women >30 years (FOR = 1.093, 95% CI: 0.946–1.263). Additionally, although the strength of the relationship between depression and fertility changed after the stratification analysis, we found no significant interaction between depression and other stratified factors (all P for interaction >0.05).

Couple-based analysis of associations between preconception depression and fertility

As Table 2 indicates, the median (P25, P75) TTP in the four groups—namely, neither partner with depression, man-only depression, woman-only depression, and both partners with depression—were 3.0 (2.0, 6.0), 3.0 (2.0, 7.0), 3.0 (2.0, 7.0), and 3.0 (2.0, 9.0) months, respectively. The log-rank test revealed a significant difference in overall pregnancy rates between the above four groups (P = 0.013). Specifically, couples where neither partner had depressive symptoms were most likely—while those wherein both the man and the woman had depressive symptoms were least likely—to conceive (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Figure 3 presents the full adjusted FOR (95% CI) and RR (95% CI) values for the association between couples’ depression and their fertility and infertility, respectively. For the fertility analysis, we adjusted for each partner’s age, BMI, personal income, education level, occupation, smoking, drinking, physical activity levels; the woman’s age of menarche, pregnancy history, live birth history, spontaneous abortion history, stillbirth history, and induced abortion history; and the man’s age of first spermatogenesis and first sexual intercourse (full adjusted model). We found that compared with couples where neither partner had depression, those where both partners had depression exhibited reduced fertility (adjusted FOR = 0.904, 95% CI: 0.838–0.975); meanwhile, no significant association was found in the man-only and woman-only depression groups. For the infertility analysis, in the fully adjusted model, compared to couples wherein neither partner had depression, the risk of infertility in the woman-only depression group and the group where both partners had depression increased by 17.8% (RR = 1.178; 95% CI: 1.026–1.353) and 46.9% (RR = 1.469; 95% CI: 1.203–1.793), respectively.

Figure 3.

Associations of couples’ depression with their fertility. Data were adjusted for each partner’s age, BMI, personal income, education level, occupation, smoking, drinking, physical activity levels; women’s age of menarche, pregnancy history, live birth history, spontaneous abortion history, stillbirth history, and induced abortion history; and men’s age of first spermatogenesis and first sexual intercourse. In the subgroup analyses, data were adjusted for all the other factors, except the current stratified factor. FOR, fertility odds ratio; RR, relative risk; BMI, body mass index.

Figure 3 also presents the stratified analyses’ results. Stratifying factors exerted no significant modifying effect on the association between co-exposure to depression in couples and their fertility—with all P values for interaction greater than 0.05.

The above-mentioned results remained largely unchanged when we excluded the couples who became pregnant through ART and those with specific factors of infertility related to females or males or both or restricted the analysis to couples who believed that the COVID-19 pandemic did not affect their pregnancy preparedness (Supplementary Figs S2, S3, and S4).

Discussion

Although much research has examined the relationship between depression and fertility, most of it has considered only one partner (Lynch et al., 2012; Nillni et al., 2016) or underrepresented populations (such as patients from reproductive centers) (Purewal et al., 2018). In this prospective cohort study, we focused on the general population and considered both partners to explore the association between preconception depression and fertility. Our results indicated that compared to the couples wherein neither partner had depressive symptoms, the couples wherein both partners had depression needed a longer time to become pregnant and were more likely to be infertile. Our study—compared with previous studies—provided stronger evidence for a link between depression and fertility.

In this study, 10 834 (65.6%) and 11 580 (70.2%) couples achieved pregnancy within the first 6 and 12 months, respectively; this proportion is slightly lower than that reported by a community-based cohort study of TTP in Guangzhou, China, which indicated that 968 (69.1%) and 1082 (77.2%) couples conceived within the first 6 and 12 months, respectively (Zhong et al., 2023). Our study reports an infertility rate of 13.01%, which falls within the range reported for the estimated period prevalence of infertility by the World Health Organization (10.0–16.4%) (https://www.who.int/health-topics/infertility). These similar pregnancy and infertility rates indicate that the participants are a good representation of the general population.

This study’s individual-specific analysis demonstrated that women with preconception depression needed a longer time to become pregnant, and women or men with preconception depression exhibited an increased risk of infertility. Consistent with our results, an internet-based preconception cohort with 2146 women found that participants with severe—compared with no or low—depressive symptoms at baseline exhibited a higher risk of decreased fertility (Nillni et al., 2016). However, another prospective cohort with 339 women found no association between depression and TTP (in cycles) and the day-specific probabilities of pregnancy (Lynch et al., 2012). Additionally, Evans-Hoeker et al. (2018) examined about 1600 couples who were infertile and pursuing non-IVF fertility treatments; they found that men with currently active major depression had low odds of achieving pregnancy but reported a positive association between women’s current active major depression and the odds of pregnancy. The inconsistency may be attributable to the differences in the study population, sample size, and study design.

Fertility depends on the couple, not merely on the man or the woman. Although couple-based epidemiological studies exploring the relationship between depressive symptoms and TTP and infertility are lacking, research has reported that depression decreases marital satisfaction and the frequency of sexual intercourse (Maroufizadeh et al., 2018), which is closely associated with decreased fertility in couples. Moreover, we observed that even if the male partner had depressive symptoms and the female partner did not, their risk of infertility did not increase significantly. This indicates the different roles of women’s and men’s depression in infertility, highlighting that achieving a pregnancy involves more factors for women than of men. For example, depression is associated with multiple female subfecundity symptoms, including sexual dysfunction (McMillan et al., 2017), menstrual disorder (Strine et al., 2005), low rates of oocyte retrieval (Worly and Gur, 2015), and abnormal changes in reproductive hormones (Padda et al., 2021). Additionally, female partners’ psychological states are strongly influenced by their male partners’ psychological states, but not vice versa. Studies have indicated that male partners’ depression is significantly associated with female partners’ happiness, but female partners’ depression is rarely associated with male partners’ happiness (Stimpson et al., 2006). In sum, more couple-based investigations are needed to confirm our innovative findings.

Although we found that preconception depression was associated with decreased fertility and an increased risk of infertility, the underlying mechanisms remain unknown. Human reproduction depends on an intact HPG axis that includes multiple reproductive hormones, such as FSH, LH, and GnRH (Kim et al., 2013; Maggi et al., 2016). Notably, FSH and LH—controlled by the hypothalamus through GnRH—play an important role in promoting ovarian follicle development and maturation and prompting ovulation in women and initiating spermatogenesis in men (Marshall and Kelch, 1986). Previous studies have revealed a dysfunctional HPG axis in women with depression (Meller et al., 2001), which may impair a couple’s fertility. Additionally, our research group has previously demonstrated that couples with—compared with those without—depression are more likely to engage in unhealthy lifestyles, such as smoking, drinking, and poor sleep quality, which are, reportedly, associated with decreased fertility (Sansone et al., 2018; Hernáez et al., 2022; Yao et al., 2022). Moreover, patients with depression are more likely to consume antidepressants, which may lessen the odds of a woman with a history of depression becoming pregnant naturally (Casilla-Lennon et al., 2016). Lastly, according to the actor–partner interdependence model, depression in one can decrease marital satisfaction in both partners (Maroufizadeh et al., 2018), which may reduce their sexual intercourse frequency, thus decreasing their fertility (Zhu et al., 2022).

Interestingly, our study revealed a significant moderating role of women’s age in the relationship between depressive symptoms in women and TTP, exhibiting a highly pronounced association in women aged less than 30 years but not in those aged above 30 years. Previous studies have indicated that women’s fertility begins declining significantly after the age of 30 years (Dunson et al., 2002). Additionally, the decline in fertility is generally attributable to ovarian aging and other age-related gynecological diseases (Rowlands et al., 2021; Moghadam et al., 2022). Certainly, the sample size may have been reduced after stratification.

The strengths of this study include its large couple-based population (16 521 couples), multicenter design (16 premarital clinics), and representative sample of childbearing age (community-based sample), which were less influenced by hospital-based treatment processes and health-related biases, thereby allowing us to ascertain the associations with adequate power. Its further strengths include its consideration of both couple-based and individual-specific models, which enabled us to assess the effect of depression in men, women, and both partners on couple fertility.

Nevertheless, this study had several limitations. First, the self-reported nature of our data precipitates reporting and recall bias. Second, we employed a cut-off score of 5 to define depression—inconsistent with prior studies (Evans-Hoeker et al., 2018), which used a cut-off score of 10 to define depression. However, the definition of depression with a cut-off score of 5 is ideal for community-based investigations. One study demonstrated a sensitivity of 0.86 and specificity of 0.75 for the cut-off score of 5 and a sensitivity of 0.49 and specificity of 0.95 for the cut-off score of 10 in primary care (Zuithoff et al., 2010). Third, although we adjusted for as many confounding factors as possible, some residual confounding factors remain, such as the use of medications, especially depression medications, frequency of sexual intercourse, and prior depressive and anxiety symptoms. Fourth, we assessed depression only at baseline, but depression might change over time; therefore, we could not detect the effect of changes in depression over time on fertility.

Conclusion

In this large couple-based prospective cohort study, individual-specific analysis revealed that preconception depression in either men or women was associated with an increased risk of infertility and that preconception depression in women was associated with a longer TTP, while couple-based analysis suggested that couples where both partners had depression needed a longer TTP and exhibit an increased risk of infertility. However, we found that even if the man had depressive symptoms while the woman did not, the couple’s risk of infertility did not significantly increase. Further evidence from well-designed epidemiological studies that consider medically diagnosed depression, assess depression at multiple timepoints, and employ longer follow-up periods are needed to clarify the effects of individual and couple preconception depression on their fertility.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank the doctors and nurses of the 16 premarital examination centers, as well as the staff who provide technical support for our project.

Contributor Information

Tierong Liao, Department of Maternal, Child and Adolescent Health, School of Public Health, Anhui Medical University, Hefei, China.

Yaya Gao, Department of Maternal, Child and Adolescent Health, School of Public Health, Anhui Medical University, Hefei, China.

Xinliu Yang, Anhui Provincial Key Laboratory of Population Health and Aristogenics, Anhui Medical University, Hefei, China.

Yanlan Tang, Anhui Provincial Key Laboratory of Population Health and Aristogenics, Anhui Medical University, Hefei, China.

Baolin Wang, Key Laboratory of Population Health Across Life Cycle, Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China, Anhui Medical University, Hefei, China.

Qianhui Yang, Key Laboratory of Population Health Across Life Cycle, Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China, Anhui Medical University, Hefei, China.

Xin Gao, Key Laboratory of Population Health Across Life Cycle, Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China, Anhui Medical University, Hefei, China.

Ying Tang, Key Laboratory of Population Health Across Life Cycle, Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China, Anhui Medical University, Hefei, China.

Kunjing He, Department of Maternal, Child and Adolescent Health, School of Public Health, Anhui Medical University, Hefei, China.

Jing Shen, Department of Maternal, Child and Adolescent Health, School of Public Health, Anhui Medical University, Hefei, China.

Shuangshuang Bao, Key Laboratory of Population Health Across Life Cycle, Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China, Anhui Medical University, Hefei, China.

Guixia Pan, Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, School of Public Health, Anhui Medical University, Hefei, China.

Peng Zhu, Department of Maternal, Child and Adolescent Health, School of Public Health, Anhui Medical University, Hefei, China.

Fangbiao Tao, Key Laboratory of Population Health Across Life Cycle, Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China, Anhui Medical University, Hefei, China.

Shanshan Shao, Department of Maternal, Child and Adolescent Health, School of Public Health, Anhui Medical University, Hefei, China.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at Human Reproduction Open online.

Data availability

The data underlying this article were provided by the Reproductive Health of Childbearing Couples-Anhui Cohort (RHCC-AC). Data will be shared on request to the corresponding author with permission of RHCC-AC.

Authors’ roles

All authors fulfill the criteria for authorship. T.L., Y.G., and S.S. conceptualized the manuscript; T.L. and Y.G. prepared the initial draft. T.L., Y.G., X.Y., Y.T., B.W., Y.T., Q.Y., X.G., K.H., and J.S. were involved in data collection and collation. S.S., S.B., P.Z., G.P., and F.T. were involved in project administration. P.Z., F.T., and S.S. provided the funding and resources and contributed to revising the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82273638) and the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2018YFC1004201).

Conflict of interest

All authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bai F, Wang DY, Fan YJ, Qiu J, Wang L, Dai Y, Song L.. Assisted reproductive technology service availability, efficacy and safety in mainland China: 2016. Hum Reprod 2020;35:446–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carré J, Gatimel N, Moreau J, Parinaud J, Léandri R.. Does air pollution play a role in infertility?: a systematic review. Environ Health 2017;16:82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casilla-Lennon MM, Meltzer-Brody S, Steiner AZ.. The effect of antidepressants on fertility. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2016;215:314.e1–314.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers GM, Dyer S, Zegers-Hochschild F, de Mouzon J, Ishihara O, Banker M, Mansour R, Kupka MS, Adamson GD.. International Committee for Monitoring Assisted Reproductive Technologies world report: assisted reproductive technology, 2014†. Hum Reprod 2021;36:2921–2934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COVID-19 Mental Disorders Collaborators. Global prevalence and burden of depressive and anxiety disorders in 204 countries and territories in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet 2021;398:1700–1712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui R. Editorial: a systematic review of depression. Curr Neuropharmacol 2015;13:480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de La Rochebrochard E, de Mouzon J, Thépot F, Thonneau P; French National IVF Registry (FIVNAT) Association. Fathers over 40 and increased failure to conceive: the lessons of in vitro fertilization in France. Fertil Steril 2006;85:1420–1424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Difrancesco S, Lamers F, Riese H, Merikangas KR, Beekman ATF, van Hemert AM, Schoevers RA, Penninx BWJH.. Sleep, circadian rhythm, and physical activity patterns in depressive and anxiety disorders: a 2-week ambulatory assessment study. Depress Anxiety 2019;36:975–986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dokras A, Stener-Victorin E, Yildiz BO, Li R, Ottey S, Shah D, Epperson N, Teede H.. Androgen excess- polycystic ovary syndrome society: position statement on depression, anxiety, quality of life, and eating disorders in polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril 2018;109:888–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunson DB, Colombo B, Baird DD.. Changes with age in the level and duration of fertility in the menstrual cycle. Hum Reprod 2002;17:1399–1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans-Hoeker EA, Eisenberg E, Diamond MP, Legro RS, Alvero R, Coutifaris C, Casson PR, Christman GM, Hansen KR, Zhang HP et al. Major depression, antidepressant use, and male and female fertility. Fertil Steril 2018;109:879–887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gan H, Li M, Wang X, Yang Q, Tang Y, Wang B, Liu K, Zhu P, Shao S, Tao F. et al. Low and mismatched socioeconomic status between newlyweds increased their risk of depressive symptoms: a multi-center study. Front Psychiatry 2022;13:1038061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golovina K, Elovainio M, Hakulinen C.. Association between depression and the likelihood of having children: a nationwide register study in Finland. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2023;228:211.e1–211.e11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hämmerli K, Znoj H, Barth J.. The efficacy of psychological interventions for infertile patients: a meta-analysis examining mental health and pregnancy rate. Hum Reprod Update 2009;15:279–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernáez Á, Rogne T, Skåra KH, Håberg SE, Page CM, Fraser A, Burgess S, Lawlor DA, Magnus MC.. Body mass index and subfertility: multivariable regression and Mendelian randomization analyses in the Norwegian Mother, Father and Child Cohort Study. Hum Reprod 2021;36:3141–3151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernáez Á, Wootton RE, Page CM, Skåra KH, Fraser A, Rogne T. et al. Smoking and infertility: multivariable regression and Mendelian randomization analyses in the Norwegian Mother, Father and Child Cohort Study. Fertil Steril 2022;118:180–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holley SR, Pasch LA, Bleil ME, Gregorich S, Katz PK, Adler NE.. Prevalence and predictors of major depressive disorder for fertility treatment patients and their partners. Fertil Steril 2015;103:1332–1339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim B, Kang ES, Fava M, Mischoulon D, Soskin D, Yu BH. et al. Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), current suicidal ideation and attempt in female patients with major depressive disorder. Psychiatry Res 2013;210:951–956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korczak DJ, Perruzza S, Chandrapalan M, Cost K, Cleverley K, Birken CS. et al. The association of diet and depression: an analysis of dietary measures in depressed, non-depressed, and healthy youth. Nutr Neurosci 2022;25:1948–1955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch CD, Sundaram R, Buck Louis GM, Lum KJ, Pyper C.. Are increased levels of self-reported psychosocial stress, anxiety, and depression associated with fecundity? Fertil Steril 2012;98:453–458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macfarlane DJ, Lee CC, Ho EY, Chan KL, Chan DT.. Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of IPAQ (short, last 7 days). J Sci Med Sport 2007;10:45–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maggi R, Cariboni AM, Marelli MM, Moretti RM, Andrè V, Marzagalli M, Limonta P.. GnRH and GnRH receptors in the pathophysiology of the human female reproductive system. Hum Reprod Update 2016;22:358–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maroufizadeh S, Hosseini M, Rahimi Foroushani A, Omani-Samani R, Amini P.. The relationship between marital satisfaction and depression in infertile couples: an actor-partner interdependence model approach. BMC Psychiatry 2018;18:310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall JC, Kelch RP.. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone: role of pulsatile secretion in the regulation of reproduction. N Engl J Med 1986;315:1459–1468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massányi P, Massányi M, Madeddu R, Stawarz R, Lukáč N.. Effects of cadmium, lead, and mercury on the structure and function of reproductive organs. Toxics 2020;8:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMillan E, Adan Sanchez A, Bhaduri A, Pehlivan N, Monson K, Badcock P, Thompson K, Killackey E, Chanen A, O'Donoghue B.. Sexual functioning and experiences in young people affected by mental health disorders. Psychiatry Res 2017;253:249–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meller WH, Grambsch PL, Bingham C, Tagatz GE.. Hypothalamic pituitary gonadal axis dysregulation in depressed women. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2001;26:253–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mena GP, Mielke GI, Brown WJ.. Do physical activity, sitting time and body mass index affect fertility over a 15-year period in women? Data from a large population-based cohort study. Hum Reprod 2020;35:676–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moghadam ARE, Moghadam MT, Hemadi M, Saki G.. Oocyte quality and aging. JBRA Assist Reprod 2022;26:105–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nillni YI, Wesselink AK, Gradus JL, Hatch EE, Rothman KJ, Mikkelsen EM, Wise LA.. Depression, anxiety, and psychotropic medication use and fecundability. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2016;215:453.e1–453.e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padda J, Khalid K, Hitawala G, Batra N, Pokhriyal S, Mohan A, Zubair U, Cooper AC, Jean-Charles G.. Depression and its effect on the menstrual cycle. Cureus 2021;13:e16532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasch LA, Holley SR, Bleil ME, Shehab D, Katz PP, Adler NE.. Addressing the needs of fertility treatment patients and their partners: are they informed of and do they receive mental health services? Fertil Steril 2016;106:209–215.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Power RA, Kyaga S, Uher R, MacCabe JH, Långström N, Landen M, McGuffin P, Lewis CM, Lichtenstein P, Svensson AC. et al. Fecundity of patients with schizophrenia, autism, bipolar disorder, depression, anorexia nervosa, or substance abuse vs their unaffected siblings. JAMA Psychiatry 2013;70:22–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purewal S, Chapman SCE, van den Akker OBA.. Depression and state anxiety scores during assisted reproductive treatment are associated with outcome: a meta-analysis. Reprod Biomed Online 2018;36:646–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rooney KL, Domar AD.. The relationship between stress and infertility. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 2018;20:41–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowlands IJ, Abbott JA, Montgomery GW, Hockey R, Rogers P, Mishra GD.. Prevalence and incidence of endometriosis in Australian women: a data linkage cohort study. BJOG 2021;128:657–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salih Joelsson L, Tydén T, Wanggren K, Georgakis MK, Stern J, Berglund A, Skalkidou A.. Anxiety and depression symptoms among sub-fertile women, women pregnant after infertility treatment, and naturally pregnant women. Eur Psychiatry 2017;45:212–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sansone A, Di Dato C, de Angelis C, Menafra D, Pozza C, Pivonello R, Isidori A, Gianfrilli D.. Smoke, alcohol and drug addiction and male fertility. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 2018;16:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz D, Mayaux MJ.. Female fecundity as a function of age: results of artificial insemination in 2193 nulliparous women with azoospermic husbands. Federation CECOS. N Engl J Med 1982;306:404–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shani C, Yelena S, Reut BK, Adrian S, Sami H.. Suicidal risk among infertile women undergoing in-vitro fertilization: incidence and risk factors. Psychiatry Res 2016;240:53–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skoracka K, Ratajczak AE, Rychter AM, Dobrowolska A, Krela-Kaźmierczak I.. Female fertility and the nutritional approach: the most essential aspects. Adv Nutr 2021;12:2372–2386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith K. Mental health: a world of depression. Nature 2014;515:181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somigliana E, Esposito G, Viganò P, Franchi M, Corrao G, Parazzini F.. Effects of the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic on natural and ART-mediated birth rates in Lombardy Region, Northern Italy. Reprod Biomed Online 2021;43:765–767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stimpson JP, Peek MK, Markides KS.. Depression and mental health among older Mexican American spouses. Aging Ment Health 2006;10:386–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strine TW, Chapman DP, Ahluwalia IB.. Menstrual-related problems and psychological distress among women in the United States. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2005;14:316–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun H, Gong TT, Jiang YT, Zhang S, Zhao YH, Wu QJ.. Global, regional, and national prevalence and disability-adjusted life-years for infertility in 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: results from a global burden of disease study, 2017. Aging (Albany NY) 2019;11:10952–10991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tower RB, Kasl SV.. Depressive symptoms across older spouses and the moderating effect of marital closeness. Psychol Aging 1995;10:625–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vancampfort D, Kimbowa S, Schuch F, Mugisha J.. Physical activity, physical fitness and quality of life in outpatients with major depressive disorder versus matched healthy controls: data from a low-income country. J Affect Disord 2021;294:802–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vander Borght M, Wyns C.. Fertility and infertility: definition and epidemiology. Clin Biochem 2018;62:2–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman MM, Olfson M.. Depression in women: implications for health care research. Science 1995;269:799–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams KE, Marsh WK, Rasgon NL.. Mood disorders and fertility in women: a critical review of the literature and implications for future research. Hum Reprod Update 2007;13:607–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worly BL, Gur TL.. The effect of mental illness and psychotropic medication on gametes and fertility: a systematic review. J Clin Psychiatry 2015;76:974–985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Q, Gao X, Tang Y, Gan H, Wang B, Li M, Pan G, Bao S, Zhu P, Shao S. et al. Association between behavioral patterns and depression symptoms: dyadic interaction between couples. Front Psychiatry 2023;14:1242611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao Q-Y, Yuan X-Q, Liu C, Du Y-Y, Yao Y-C, Wu L-J, Jiang H-H, Deng T-R, Guo N, Deng Y-L. et al. Associations of sleep characteristics with outcomes of IVF/ICSI treatment: a prospective cohort study. Hum Reprod 2022;37:1297–1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye YX, Chen HG, Sun B, Chen YJ, Duan P, Meng TQ, Xiong CL, Wang YX, Pan A.. Associations between depression, oxidative stress, and semen quality among 1,000 healthy men screened as potential sperm donors. Fertil Steril 2022;117:86–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yland JJ, Eisenberg ML, Hatch EE, Rothman KJ, McKinnon CJ, Nillni YI, Sommer GJ, Wang TR, Wise LA. A North American prospective study of depression, psychotropic medication use, and semen quality. Fertil Steril 2021;116:833–842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong Y, Peng S, Chen Q, Huang D, Zhang G, Zhou Z.. Preconceptional thyroid stimulating hormone level and fecundity: a community-based cohort study of time to pregnancy. Fertil Steril 2023;119:313–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y, Wang B, Zhu Q, Ye J, Kuang Y.. Changes in sexual frequency among 51 150 infertile Chinese couples over the past 10 years. Hum Reprod 2022;37:1287–1296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman M. Using the 9-item patient health questionnaire to screen for and monitor depression. Jama 2019;322:2125–2126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuithoff NPA, Vergouwe Y, King M, Nazareth I, van Wezep MJ, Moons KGM, Geerlings MI.. The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 for detection of major depressive disorder in primary care: consequences of current thresholds in a crosssectional study. BMC Fam Pract 2010;11:98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article were provided by the Reproductive Health of Childbearing Couples-Anhui Cohort (RHCC-AC). Data will be shared on request to the corresponding author with permission of RHCC-AC.