Abstract

Objectives.

Due to the rarity of olfactory neuroblastoma (ONB), there is ongoing debate about optimal treatment strategies, especially for early-stage or locally advanced cases. Therefore, our study aimed to explore experiences from multiple centers to identify factors that influence the oncological outcomes of ONB.

Methods.

We retrospectively analyzed 195 ONB patients treated at nine tertiary hospitals in South Korea between December 1992 and December 2019. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was used to evaluate oncological outcomes, and a Cox proportional hazards regression model was employed to analyze prognostic factors for survival outcomes. Furthermore, we conducted 1:1 nearest-neighbor matching to investigate differences in clinical outcomes according to the use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

Results.

In our cohort, the 5-year overall survival (OS) rate was 78.6%, and the 5-year disease-free survival (DFS) rate was 62.4%. The Cox proportional hazards model revealed that the modified Kadish (mKadish) stage and Dulguerov T status were significantly associated with DFS, while the mKadish stage and Hyams grade were identified as prognostic factors for OS. The subgroup analyses indicated a trend toward improved 5-year DFS with dural resection in mKadish A and B cases, even though the result was statistically insignificant. Induction chemotherapy did not provide a survival benefit in this study after matching for the mKadish stage and nodal status.

Conclusion.

Clinical staging and pathologic grading are important prognostic factors in ONB. Dural resection in mKadish A and B did not show a significant survival benefit. Similarly, induction chemotherapy also did not show a survival benefit, even after stage matching.

Keywords: Esthesioneuroblastoma, Neoadjuvant Therapy, Prognosis, Treatment Outcome

INTRODUCTION

Esthesioneuroblastoma, also known as olfactory neuroblastoma (ONB), is a rare malignant neoplasm that originates from the olfactory epithelium in the cribriform plate [1,2]. It accounts for 3%–5% of all sinonasal malignancies, but its etiology remains unclear [3,4]. ONB typically presents with an insidious growth pattern and minimal symptoms, which often leads to a delayed diagnosis and advanced-stage presentation [5]. As the disease progresses, ONB becomes locally aggressive, frequently causing significant erosion of the skull base and/or orbit [6,7]. This aggressive behavior makes the effective treatment of ONB particularly challenging.

Various staging systems and histologic grading scales have been developed to guide treatment decisions and predict outcomes for ONB. In 1976, Kadish et al. [8] introduced a classification system that has gained widespread acceptance. This system categorizes tumors according to their location: confined to the nasal cavity (stage A), invasion into the paranasal sinuses (stage B), or extension beyond the nasal cavity and sinuses (stage C) [8]. Subsequently, Morita et al. expanded this system by adding stage D, which accounts for patients with regional and distant metastasis [9]. In 1992, Dulguerov and Calcaterra [10] proposed a tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) staging system. For histological grading, Hyams devised a scale in 1988 that classifies ONB into four grades (I–IV), based on a range of histopathological characteristics [11].

Historically, the most widely accepted treatment for ONB has involved a multimodal approach combining surgery with adjuvant radiotherapy [5,12,13], which has provided reasonable locoregional control [14-17]. However, patients with unresectable or high-grade tumors often have a poor prognosis, even with aggressive multimodal treatment [15,18,19]. Chemotherapy has been used occasionally in cases of advanced-stage disease or when surgical margins are positive, but it is not typically a firstline treatment. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy has elicited a positive response in some patients with locally advanced ONB, yet its role remains poorly defined [20-26]. Consequently, no clearly defined treatment protocol exists for locally advanced ONB [27]. Due to the rarity of ONB and the challenges associated with large databases, most studies have relied on data from single institutions. Therefore, we examined multicenter ONB data to identify variables affecting the disease course, survival outcomes, and treatment options.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

This retrospective multicenter analysis of ONB patients diagnosed through histological examination was conducted by the Korean Sinonasal Tumor and Skull Base Surgery Study Group. It included patients treated at nine tertiary hospitals in Korea from December 1992 to December 2019. This study received approval from the Institutional Review Boards of all participating institutions with a waiver of informed consent.

Data collection and clinical outcome measurement

Patient demographics, staging, tumor invasion extent, treatment details, pathologic data, and oncologic outcomes were collected, if available. Staging was based on the modified Kadish (mKadish) stage [8] and Dulguerov T status [10]. We used the Hyams histologic grading system and categorized patients as low-grade (grades 1 and 2) or high-grade (grades 3 and 4) [11].

Intracranial and orbital invasions were initially classified based on imaging data. Intracranial invasion was categorized into four groups: absent, dura invasion (including suspicious condition), minimal intracranial invasion with an intact arachnoid plane, and extensive intracranial invasion with definite brain parenchymal invasion. Orbital invasion was classified into four groups based on the involved structures: absent, periorbita only, extension to orbital fat, and involvement of extraocular muscle or beyond. Disease-free survival (DFS) was defined as the duration from the initial treatment to the occurrence of any signs or symptoms indicating recurrence at any site. Overall survival (OS) was defined as the time from the initial treatment to death from any cause.

Statistical methods and analysis

Data are presented using means with standard deviations or absolute and relative frequencies. Fisher’s exact test was used to compare qualitative data. A Kaplan-Meier survival analysis assessed and compared survival outcomes using the log-rank test. Univariable and multivariable analyses used Cox proportional hazards regression models to identify independent risk factors for survival outcomes. Factors that were significant in the univariable analyses were included in the multivariable models.

To evaluate the effects of neoadjuvant chemotherapy on survival outcomes, we performed a matched subgroup analysis between patients who received neoadjuvant chemotherapy and those who underwent definitive treatment without neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Matching was based on the mKadish stage and node status and was conducted through 1:1 nearest neighbor matching without replacement. A caliper of 0.15 standard deviations of the logit propensity score was used to ensure the balance of covariates. Covariate balance was assessed by calculating standardized mean differences, with values below 0.10 (absolute value) taken to indicate well-balanced data. After matching, the analysis included 128 cases, with 64 cases in each group. All statistical analyses were performed in SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute), and a P-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Clinical and pathological characteristics

This study included 195 patients with an average age of 45.4 years. The majority of participants were male, accounting for 62.6%. The most common stage of disease was mKadish stage C, which was present in 114 patients (58.5%), while Dulguerov T4 status was observed in 83 patients (42.8%). When intracranial invasion occurred, extensive intracranial invasion was the most prevalent condition. Patient characteristics such as staging, orbital/intracranial invasion, nodal status, and pathologic grade (Hyams grade) are detailed in Table 1. The average follow-up period for the study was 66.6 months.

Table 1.

Patient and tumor characteristics

| Variable | Value |

|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis (yr) | 45.4±16.6 |

| Sex | |

| Female | 73 (37.4) |

| Male | 122 (62.6) |

| mKadish stage | |

| A | 18 (9.2) |

| B | 38 (19.5) |

| C | 114 (58.5) |

| D | 25 (12.8) |

| Dulguerov T status (n=194) | |

| T1 | 26 (13.4) |

| T2 | 50 (25.8) |

| T3 | 35 (18.0) |

| T4 | 83 (42.8) |

| Intracranial invasion | |

| Absent | 93 (47.7) |

| Dural invasion | 23 (11.8) |

| Minimal intracranial invasion | 35 (17.9) |

| Extensive intracranial invasion | 44 (22.6) |

| Orbital invasion | |

| Absent | 142 (72.8) |

| Periorbita only | 23 (11.8) |

| Orbital fat | 20 (10.3) |

| Extraocular muscle or more | 10 (5.1) |

| Nodal status (n=194) | |

| Negative | 171 (88.1) |

| Positive | 23 (11.9) |

| Hyams grade (n=129) | |

| 1 | 24 (18.6) |

| 2 | 67 (51.9) |

| 3 | 28 (21.7) |

| 4 | 10 (7.6) |

| Follow-up period (mo) | 66.6±67.6 |

Values are presented as mean±standard deviation or number (%).

mKadish, modified Kadish.

Treatment characteristics

The initial treatment analysis included 187 subjects, after excluding eight due to unavailable information (Table 2). Of these patients, 76 (40.6%) underwent neoadjuvant chemotherapy prior to surgery or radiotherapy. Within the group that did not receive neoadjuvant chemotherapy, 20.8% were treated with a single modality (18.7% with surgery alone and 2.1% with radiotherapy alone). The remaining 57 patients underwent multimodal treatment. An additional treatment category encompassed patients who underwent surgery for residual tumors following concurrent chemoradiotherapy (CCRT) or chemotherapy, as well as those who received CCRT subsequent to surgery. Furthermore, surgical data concerning the resection margin were examined in 87 patients, with 59 (67.8%) having negative margins (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of the initial treatment and resection margin status

| Initial treatment (n=187) | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy+surgery | 6 (3.2) |

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy+surgery+adjuvant radiotherapy | 32 (17.1) |

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy+radiotherapy (±chemotherapy) | 38 (20.3) |

| Surgery alone | 35 (18.7) |

| Surgery+adjuvant radiotherapy | 48 (25.7) |

| Radiotherapy alone | 4 (2.1) |

| Concurrent chemoradiotherapy alone | 9 (4.8) |

| Palliative chemotherapy without local treatment | 2 (1.1) |

| Concurrent chemoradiotherapy/chemotherapy+surgery | 13 (7.0) |

| Resection margin status in surgery cases (n=87) | |

| Negative | 59 (67.8) |

| Positive | 28 (32.2) |

We assessed mKadish staging in 128 patients who underwent surgery and had available information about the surgical approach (Table 3). Patients treated with both endoscopic and open surgical approaches were categorized as having undergone endoscopeassisted craniofacial resection (CFR). Notably, significant differences in the surgical approach were observed according to the mKadish stage. Endoscopic tumor resection without dura resection was common for mKadish stages A and B, whereas endoscopic CFR was frequently used for mKadish stage C. For mKadish stage D, the group undergoing endoscopic surgery without dural resection included patients who had either received neoadjuvant chemotherapy prior to surgery or were undergoing palliative surgical interventions.

Table 3.

mKadish stage and surgical approach

| Variable | mKadish stage |

Total | P-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | |||

| Endoscopic surgery without dura resection | 13 | 23 | 10 | 6 | 52 | <0.001 |

| Endoscopic CFR | 1 | 9 | 26 | 2 | 38 | |

| Endoscope assisted CFR | 0 | 2 | 15 | 0 | 17 | |

| Open CFR | 1 | 1 | 15 | 4 | 21 | |

| Total | 15 | 35 | 66 | 12 | 128 | |

mKadish, modified Kadish; CFR, craniofacial resection.

Oncologic outcomes

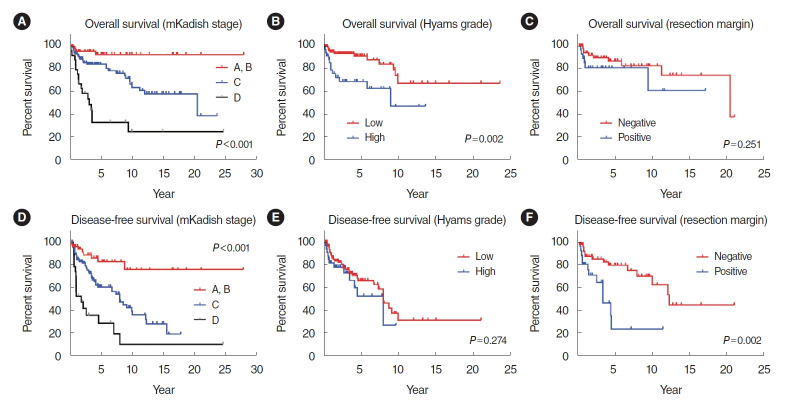

The 5-year OS rate was 78.6% and varied significantly based on mKadish staging (Fig. 1A). Specifically, the 5-year OS rate was 92.7% for mKadish stages A and B, 84.1% for mKadish stage C, and 32.8% for mKadish stage D. When stratified by Hyams grade as low or high, the 5-year OS rates were 91.4% and 68.9%, respectively, representing another significant difference (Fig. 1B). However, no significant differences in 5-year OS were observed between groups stratified by their resection margins (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

Overall survival and disease-free survival stratified by modified Kadish staging (A, D), Hyams grade (B, E), and resection margin (C, F).

The 5-year DFS rate was 62.4%. During the follow-up period, recurrence was observed in 71 patients (36.4%), with 25 cases (12.8%) of local recurrence, 29 cases (14.9%) of regional lymph node metastasis, and 17 cases (8.7%) of distant metastasis. Stratifying by mKadish stage, the DFS rates were 82.7% for mKadish stages A and B, 60.3% for mKadish stage C, and 28.2% for mKadish stage D, constituting statistically significant differences (Fig. 1D). However, when stratified by Hyams grade, no significant difference between groups was observed (Fig. 1E). Patients with negative margins had a significantly higher DFS rate (79.8%) than those with positive margins (23.1%) (Fig. 1F).

Prognostic factors for survival outcomes

The results of the univariable analysis for survival outcome prognosticators are presented in Table 4. mKadish stage and Dulguerov T status showed significant associations with DFS and OS. A higher Hyams grade was related to poorer OS (hazard ratio [HR], 3.33; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.46–7.59), but not DFS. Orbital invasion beyond the orbital fat and minimal to extensive intracranial invasion were associated with worse OS (HR, 2.98; 95% CI, 1.58–5.64 and HR, 2.32; 95% CI, 1.27–4.25, respectively). However, the treatment strategies and surgical approaches showed no significant correlations with either OS or DFS.

Table 4.

Univariable and multivariable Cox regression analyses for survival

| Variable | Univariable |

Multivariable |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DFS |

OS |

DFS |

OS |

|||||

| HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value | |

| mKadish stage | 0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| A | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| B | 2.37 (0.20–28.87) | >0.999 | 2.18 (0.05–88.25) | >0.999 | 2.60 (0.20–33.07) | >0.999 | 2.54 (0.05–122.98) | >0.999 |

| C | 5.99 (0.58–61.91) | 0.199 | 6.29 (0.19–206.87) | 0.623 | 8.06 (0.71–90.93) | 0.118 | 1.33 (0.03–59.30) | >0.999 |

| D | 12.34 (1.11–136.78) | 0.037 | 21.16 (1.19–375.94) | 0.038 | 21.50 (1.83–252.32) | 0.009 | 14.05 (0.30–667.26) | 0.304 |

| Dulguerov T status | 0.008 | 0.027 | 0.001 | 0.298 | ||||

| T1 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| T2 | 2.58 (0.61–10.95) | 0.353 | 5.12 (0.14–186.46) | 0.830 | 2.55 (0.56–11.50) | 0.413 | 2.66 (0.29–24.78) | >0.999 |

| T3 | 5.91 (1.42–24.62) | 0.009 | 16.32 (0.47–567.16) | 0.179 | 7.15 (1.62–31.66) | 0.005 | 8.62 (0.96–77.17) | >0.999 |

| T4 | 2.76 (0.72–10.55) | 0.209 | 14.13 (0.43–463.90) | 0.208 | 4.04 (0.95–17.25) | 0.063 | 5.59 (0.59–52.84) | 0.304 |

| Hyams grade | ||||||||

| Low | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||

| High | 1.04 (0.53–2.05) | 0.902 | 3.33 (1.46–7.59) | 0.004 | 4.76 (1.75–12.89) | 0.002 | ||

| Intracranial invasion | ||||||||

| Absent-dural invasion | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||

| Minimal-extensive invasion | 0.79 (0.50–1.25) | 0.315 | 2.32 (1.27–4.25) | 0.006 | 2.25 (0.80–6.34) | 0.124 | ||

| Orbital invasion | ||||||||

| Absent-periorbita only | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||

| Orbital fat-extraocular muscle or more | 0.78 (0.37–1.62) | 0.503 | 2.98 (1.58–5.64) | 0.001 | 0.79 (0.24–2.67) | 0.706 | ||

| Treatment | 0.052 | 0.456 | 0.610 | |||||

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||

| Non-neoadjuvant chemotherapy | 0.54 (0.33–0.89) | 0.015 | 0.67 (0.36–1.25) | 0.210 | 0.92 (0.59–1.44) | 0.709 | ||

| Palliative and others | 0.76 (0.35–1.66) | 0.492 | 0.87 (0.30–2.50) | 0.792 | 1.33 (0.65–2.74) | 0.433 | ||

| Surgical approach | 0.742 | 0.339 | ||||||

| Endoscopic without dura resection | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| Endoscopic CFR | 0.66 (0.25–1.78) | 0.956 | 0.93 (0.17–5.14) | >0.999 | ||||

| Endoscope assisted CFR | 0.70 (0.25–2.01) | >0.999 | 1.57 (0.33–7.42) | >0.999 | ||||

| Open CFR | 0.83 (0.36–1.92) | >0.999 | 2.37 (0.66–8.49) | 0.317 | ||||

DFS, disease-free survival; OS, overall survival; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; mKadish, modified Kadish; CFR, craniofacial resection.

The multivariable analysis of the aforementioned variables is also presented in Table 4. The mKadish stage remained an independent prognostic factor for DFS and OS. Dulguerov T status emerged as an independent prognostic factor for DFS, but not for OS. A higher Hyams grade remained an independent negative prognostic factor for OS (HR, 4.76; 95% CI, 1.75–12.89). However, the extent of orbital or intracranial invasion lost its significance.

Subgroup analysis

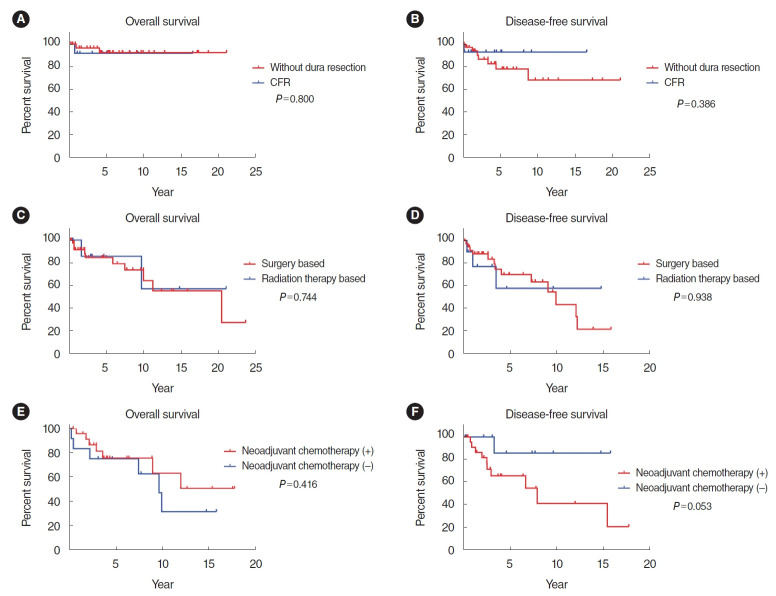

Subgroup analyses were conducted to compare clinical outcomes according to the treatment methods. First, we compared clinical outcomes based on the surgical approach in the mKadish A and B groups. Fifty patients with information about the surgical approach were classified into two groups: the CFR group (n=14) with dura resection, and the without-dura-resection group (n=36). The groups did not differ significantly in 5-year OS (91.7% vs. 92.5%) or 5-year DFS (92.9% vs. 77.8%). However, DFS in the CFR group was 92.9%, which was superior to the group without dura resection, and that tendency continued for up to 10 years (Fig. 2A and B).

Fig. 2.

Overall survival and disease-free survival in patients at mKadish stages A and B according to surgical strategy (A, B), in mKadish stage C patients according to surgery-based treatment versus radiation-based treatment (C, D), and in patients with extensive intracranial invasion according to the use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy (E, F).

Next, we evaluated the oncological outcomes of mKadish C stage patients according to whether they received surgery-based treatment (either surgery alone or surgery with adjuvant radiotherapy) or radiation-based treatment (radiotherapy alone or CCRT). Forty-nine patients were included (39 in the surgery-based group and 10 in the radiation-based group). Among those patients, 11 (22.45%) had extensive intracranial invasion, and seven of them (63.64%) underwent surgery-based treatment. One patient with invasion beyond the orbital fat underwent CCRT. No significant differences in the OS rate (84.5% vs. 85.7%, P=0.744) or DFS rate (69.9% vs. 57.9%, P=0.938) were observed between the treatment groups (Fig. 2C and D).

Third, we compared oncologic outcomes according to the use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy. When comparing patients who underwent neoadjuvant chemotherapy (n=76) with those who did not (n=96), the non-neoadjuvant chemotherapy group experienced a DFS benefit (HR, 0.54; 95% CI, 0.33–0.89), but not an OS benefit (Table 5). However, when we analyzed clinical outcomes among patients with extensive intracranial invasion (24 patients in the neoadjuvant chemotherapy group and 12 patients in the non-neoadjuvant chemotherapy group), we observed no significant differences in OS or DFS (Fig. 2E and F). In addition, after performing 1:1 nearest neighbor matching without replacement, we found no difference according to the use of induction chemotherapy in DFS (HR, 0.74; 95% CI, 0.42–1.28) or OS (HR, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.43–1.78) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Survival analysis according to neoadjuvant chemotherapy

| Variable | DFS |

OS |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Treatment (before matching) | ||||

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy | Reference | Reference | ||

| Non-neoadjuvant chemotherapy | 0.54 (0.33–0.89) | 0.015 | 0.67 (0.36–1.25) | 0.210 |

| Treatment (after matching) | ||||

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy | Reference | Reference | ||

| Non-neoadjuvant chemotherapy | 0.74 (0.42–1.28) | 0.277 | 0.87 (0.43–1.78) | 0.711 |

DFS, disease-free survival; OS, overall survival; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval.

DISCUSSION

This study reviewed cases of ONB from multiple tertiary institutions. The entire cohort exhibited a 5-year OS rate of 78.6% and a 5-year DFS rate of 62.4%, which is consistent with previous studies [28,29]. Stratification based on the mKadish stages revealed significant differences in 5-year OS and 5-year DFS according to the stage. However, when stratified by Hyams grade, only the 5-year OS showed a significant correlation. The status of resection margins significantly influenced DFS, with negative margins demonstrating better outcomes, in line with previous research [1,28]. Prognostic factors for oncological outcomes included mKadish stage for both DFS and OS, Hyams grade for OS, and Dulguerov T status for DFS, aligning with previous studies [18,28]. In addition to our data, a recent study [30] showed that incorporating the Hyams grade into traditional ONB staging systems (mKadish or Dulguerov T) may increase their ability to predict disease progression.

The treatment received by our cohort was notably diverse, with the most common approach being a combination of surgery and adjuvant radiotherapy. Nearly 40% of the patients underwent neoadjuvant chemotherapy, while around 20% received only a single treatment modality. Among those treated with surgery alone, 20 patients (57.14%) were classified as mKadish A and B, 13 patients (37.14%) as stage C, and 2 patients (5.71%) as stage D. Examination for orbital and intracranial invasion showed that the majority of mKadish C patients who had surgery alone did not exhibit obvious intracranial invasion. In the mKadish D subgroup treated with surgery alone, one patient received palliative surgery, while the other, despite having nodal metastases, was classified as Dulguerov T2 status. All patients who were treated exclusively with radiotherapy were at mKadish stage C. Considering the varied treatment histories, we conducted a further investigation into the prognosis based on the specific treatments administered.

Before the emergence of endoscopic surgery, the standard treatment for ONB involved complete resection of the cribriform plate, dura, and olfactory bulb through CFR [31,32]. However, resecting the dura is associated with significant risks, including complications such as cerebrospinal fluid leakage and central nervous system infections. These risks present challenges in determining the appropriate extent of resection [33]. Consequently, surgeons face a dilemma when considering dura resection in patients with early-stage mKadish ONB who show no definitive signs of dural involvement on imaging studies. May et al. [32] conducted a retrospective study to compare treatment outcomes in early-stage ONB cases without skull base involvement, focusing on the impact of dural and olfactory bulb resection. The study found that resecting the dura and olfactory bulb did not improve DFS. In contrast, resection of the cribriform plate significantly increased DFS, with a 5-year rate of 100%, compared to 75% in patients who did not undergo the procedure. The authors suggested that the removal of the adjacent anatomical layer beyond the tumor, ensuring a negative resection margin, accounted for this improvement. In our analysis, we observed no statistically significant differences in 5-year OS and DFS when comparing the dura resection status among patients with mKadish stage A or B ONB. The 5-year DFS was 77.8% in patients who did not have dura resection and 92.9% in those who did, although this difference was not statistically significant (P=0.386). A recent study reported a 12.1% incidence of pathological dural involvement in patients without radiological evidence of skull base involvement [34], suggesting a potential benefit of dural resection for local recurrence-free survival. However, due to the lack of significant statistical difference, the role of dural resection in the management of early-stage tumors remains to be confirmed by further research.

Despite aggressive multimodal treatment, patients with unresectable or Hyams high-grade tumors or those with nodal metastasis continue to have a poor prognosis [15,18,19]. In select cases, induction chemotherapy may be warranted prior to definitive therapy [13]. A number of studies have explored the use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy to enable successful surgical resection of advanced tumors [35,36] or to inform non-surgical management via definitive chemoradiation [37]. The chemosensitivity of ONB has been postulated due to its biological resemblance to other chemosensitive neural crest-derived tumors [38,39]. Nonetheless, the role of chemotherapy in the management of ONB is still a matter of debate [40,41]. Recent research has shown tumor response rates of 74%–82% in locally advanced (mKadish C) ONB treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy, which has been associated with improved surgical outcomes, OS, and DFS [12,42,43], as well as with enabling margin-negative resections [13]. However, most of these studies have focused solely on the response rates and clinical outcomes of neoadjuvant chemotherapy, without a comparative analysis involving patients who did not receive neoadjuvant chemotherapy. To address this gap, we performed a comparative analysis to evaluate the impact of neoadjuvant chemotherapy on OS and DFS. This comparison was feasible due to the varied treatment approaches employed by the multiple institutions participating in this study for locally advanced ONB. The initial cohort consisted of 51 patients (67.11%) with mKadish C and fifteen patients (19.74%) with mKadish D in the neoadjuvant chemotherapy group. The group that did not receive neoadjuvant chemotherapy included 43 patients (48.43%) with mKadish C and six patients (6.90%) with mKadish D. Prior to matching, the non-neoadjuvant group exhibited a better DFS than the neoadjuvant group, which may be attributed to a lower proportion of patients with advanced-stage disease. However, when focusing solely on patients with extensive intracranial invasion—the primary candidates for neoadjuvant chemotherapy —no significant differences in OS or DFS were found between the two groups.

Additionally, we conducted matching based on the mKadish stage and nodal status to mitigate the effects of baseline characteristics. Each group included 64 patients, with the neoadjuvant chemotherapy group consisting of 49 patients (76.56%) at mKadish stage C and five patients (7.81%) at stage D. The non-neoadjuvant chemotherapy group had 47 patients (73.44%) at stage C and seven patients (10.94%) at stage D. There were ten patients at mKadish stages A and B in both groups. In this matched analysis, neoadjuvant chemotherapy did not demonstrate a statistically significant benefit in terms of survival outcomes. To the best of our knowledge, these are the first comparative data regarding the role of neoadjuvant chemotherapy in the treatment of ONB. However, our findings are at odds with the promising results on chemotherapy effectiveness reported in previous studies. The retrospective design of our study made it challenging to achieve groups as well-matched as those in a randomized controlled trial, even after the matching process. Additionally, as a retrospective multicenter study, the treatment decision-making process varied slightly among hospitals, which could introduce selection bias and affect the results. Therefore, further research is warranted to explore this issue.

This study has limitations. Firstly, this was a retrospective review, with limited comprehensive data availability for all patients. Some patients were excluded from the analysis due to insufficient information about certain variables, which might have influenced the results. For example, in this study, resection margin status significantly impacted DFS, but not OS. However, these conclusions are based on data obtained from 87 patients (44.6% of the total) for whom resection margin information was available. Therefore, these factors might act as limitations when analyzing the impact of resection margin on OS. Secondly, as a multicenter study involving nine centers, there was heterogeneity in the treatment approaches. The decision-making process for treatment options might have differed slightly among hospitals, potentially affecting the analysis results. Moreover, variations in treatment regimens across hospitals, including differences in chemotherapy agents, radiotherapy doses, treatment durations, and other factors, might have contributed to variations in treatment outcomes, even among patients receiving the same type of treatment. Lastly, this study did analyze prophylactic neck irradiation. As studies have reported that it has a significant impact on reducing cervical lymph node recurrence, there has been growing interest in elective neck irradiation for N0 patients. However, no institution in our study offers prophylactic neck irradiation, precluding us from investigating this topic. Despite those limitations, this retrospective study presents data from a substantial multicenter investigation of different treatment regimens in patients with ONB.

In this multicenter study of 195 patients with ONB, the 5-year OS rate was 78.6% and the 5-year DFS rate was 62.4%. The prognostic factors for OS were the mKadish stage and Hyams grade, and the predictors of DFS were the mKadish stage and Dulguerov T status. Dural resection in mKadish A and B did not show a significant survival benefit. In this study, induction chemotherapy did not provide a survival benefit after matching for the mKadish stage and nodal status.

HIGHLIGHTS

▪ In 195 olfactory neuroblastoma patients, the 5-year overall survival rate was 78.6% and the 5-year disease-free survival rate was 62.4%.

▪ Preoperative staging categories, including modified Kadish and Dulguerov T status and Hyams pathologic grading, are important prognostic factors for olfactory neuroblastoma.

▪ Dural resection for early-stage tumors did not show a significant survival benefit.

▪ Induction chemotherapy for advanced tumors did not significantly improve survival.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization: SDH, DYK. Data Curation: JHK, SJH, HJC, DHL, SJM, SKP, YWK. Formal analysis: SDH, SIP. Methodology: SWC, TBW, DYK. Writing–original draft preparation: SDH, SIP. Writing–review & editing: SWC, TBW, DYK.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arnold MA, Farnoosh S, Gore MR. Comparing Kadish and modified Dulguerov staging systems for olfactory neuroblastoma: an individual participant data meta-analysis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020 Sep;163(3):418–27. doi: 10.1177/0194599820915487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marinelli JP, Janus JR, Van Gompel JJ, Link MJ, Moore EJ, Van Abel KM, et al. Dural invasion predicts the laterality and development of neck metastases in esthesioneuroblastoma. J Neurol Surg B Skull Base. 2018 Oct;79(5):495–500. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1625977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferlito A, Rinaldo A, Rhys-Evans PH. Contemporary clinical commentary: esthesioneuroblastoma: an update on management of the neck. Laryngoscope. 2003 Nov;113(11):1935–8. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200311000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kumar M, Fallon RJ, Hill JS, Davis MM. Esthesioneuroblastoma in children. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2002;24(6):482–7. doi: 10.1097/00043426-200208000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ow TJ, Bell D, Kupferman ME, Demonte F, Hanna EY. Esthesioneuroblastoma. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2013 Jan;24(1):51–65. doi: 10.1016/j.nec.2012.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schmidt C, Potter N, Porceddu S, Panizza B. Olfactory neuroblastoma: 14-year experience at an Australian tertiary centre and the role for longer-term surveillance. J Laryngol Otol. 2017 Jul;131(S2):S29–34. doi: 10.1017/S0022215116009592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hirose T, Scheithauer BW, Lopes MB, Gerber HA, Altermatt HJ, Harner SG, et al. Olfactory neuroblastoma. An immunohistochemical, ultrastructural, and flow cytometric study. Cancer. 1995 Jul;76(1):4–19. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19950701)76:1<4::aid-cncr2820760103>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kadish S, Goodman M, Wang CC. Olfactory neuroblastoma: a clinical analysis of 17 cases. Cancer. 1976 Mar;37(3):1571–6. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197603)37:3<1571::aid-cncr2820370347>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morita A, Ebersold MJ, Olsen KD, Foote RL, Lewis JE, Quast LM. Esthesioneuroblastoma: prognosis and management. Neurosurgery. 1993 May;32(5):706–14. doi: 10.1227/00006123-199305000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dulguerov P, Calcaterra T. Esthesioneuroblastoma: the UCLA experience 1970-1990. Laryngoscope. 1992 Aug;102(8):843–9. doi: 10.1288/00005537-199208000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hyams VJ, Batsakis JG, Michaels L. Tumors of the upper respiratory tract and ear. 2nd ed. Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Su SY, Bell D, Ferrarotto R, Phan J, Roberts D, Kupferman ME, et al. Outcomes for olfactory neuroblastoma treated with induction chemotherapy. Head Neck. 2017 Aug;39(8):1671–9. doi: 10.1002/hed.24822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miller KC, Marinelli JP, Janus JR, Chintakuntlawar AV, Foote RL, Link MJ, et al. Induction therapy prior to surgical resection for patients presenting with locally advanced esthesioneuroblastoma. J Neurol Surg B Skull Base. 2021 Jul;82(Suppl 3):e131–7. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-3402026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Broich G, Pagliari A, Ottaviani F. Esthesioneuroblastoma: a general review of the cases published since the discovery of the tumour in 1924. Anticancer Res. 1997;17(4A):2683–706. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dulguerov P, Allal AS, Calcaterra TC. Esthesioneuroblastoma: a meta-analysis and review. Lancet Oncol. 2001 Nov;2(11):683–90. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(01)00558-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gruber G, Laedrach K, Baumert B, Caversaccio M, Raveh J, Greiner R. Esthesioneuroblastoma: irradiation alone and surgery alone are not enough. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002 Oct;54(2):486–91. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(02)02941-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Diaz EM, Johnigan RH, Pero C, El-Naggar AK, Roberts DB, Barker JL, et al. Olfactory neuroblastoma: the 22-year experience at one comprehensive cancer center. Head Neck. 2005 Feb;27(2):138–49. doi: 10.1002/hed.20127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jethanamest D, Morris LG, Sikora AG, Kutler DI. Esthesioneuroblastoma: a population-based analysis of survival and prognostic factors. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007 Mar;133(3):276–80. doi: 10.1001/archotol.133.3.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van Gompel JJ, Giannini C, Olsen KD, Moore E, Piccirilli M, Foote RL, et al. Long-term outcome of esthesioneuroblastoma: hyams grade predicts patient survival. J Neurol Surg B Skull Base. 2012 Oct;73(5):331–6. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1321512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Capelle L, Krawitz H. Esthesioneuroblastoma: a case report of diffuse subdural recurrence and review of recently published studies. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2008 Feb;52(1):85–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1673.2007.01919.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bachar G, Goldstein DP, Shah M, Tandon A, Ringash J, Pond G, et al. Esthesioneuroblastoma: the Princess Margaret Hospital experience. Head Neck. 2008 Dec;30(12):1607–14. doi: 10.1002/hed.20920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prasad KC, Kumar A, Prasad SC, Jain D. Endoscopic-assisted excision of esthesioneuroblastoma. J Craniofac Surg. 2007 Sep;18(5):1034–8. doi: 10.1097/scs.0b013e318157264c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fitzek MM, Thornton AF, Varvares M, Ancukiewicz M, Mcintyre J, Adams J, et al. Neuroendocrine tumors of the sinonasal tract: results of a prospective study incorporating chemotherapy, surgery, and combined proton-photon radiotherapy. Cancer. 2002 May;94(10):2623–34. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eich HT, Hero B, Staar S, Micke O, Seegenschmiedt H, Mattke A, et al. Multimodality therapy including radiotherapy and chemotherapy improves event-free survival in stage C esthesioneuroblastoma. Strahlenther Onkol. 2003 Apr;179(4):233–40. doi: 10.1007/s00066-003-1089-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bradley PJ, Jones NS, Robertson I. Diagnosis and management of esthesioneuroblastoma. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003 Apr;11(2):112–8. doi: 10.1097/00020840-200304000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim HJ, Kim CH, Lee BJ, Chung YS, Kim JK, Choi YS, et al. Surgical treatment versus concurrent chemoradiotherapy as an initial treatment modality in advanced olfactory neuroblastoma. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2007 Dec;34(4):493–8. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rimmer J, Lund VJ, Beale T, Wei WI, Howard D. Olfactory neuroblastoma: a 35-year experience and suggested follow-up protocol. Laryngoscope. 2014 Jul;124(7):1542–9. doi: 10.1002/lary.24562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McMillan RA, Van Gompel JJ, Link MJ, Moore EJ, Price DL, Stokken JK, et al. Long-term oncologic outcomes in esthesioneuroblastoma: an institutional experience of 143 patients. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2022 Dec;12(12):1457–67. doi: 10.1002/alr.23007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sun M, Wang K, Qu Y, Zhang J, Zhang S, Chen X, et al. Long-term analysis of multimodality treatment outcomes and prognosis of esthesioneuroblastomas: a single center results of 138 patients. Radiat Oncol. 2020 Sep;15(1):219. doi: 10.1186/s13014-020-01667-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Choby G, Geltzeiler M, Almeida JP, Champagne PO, Chan E, Ciporen J, et al. Multicenter survival analysis and application of an olfactory neuroblastoma staging modification incorporating Hyams grade. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2023 Sep;149(9):837–44. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2023.1939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ketcham AS, Wilkins RH, Vanburen JM, Smith RR. A combined intracranial facial approach to the paranasal sinuses. Am J Surg. 1963 Nov;106:698–703. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(63)90387-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mays AC, Bell D, Ferrarotto R, Phan J, Roberts D, Fuller CD, et al. Early stage olfactory neuroblastoma and the impact of resecting dura and olfactory bulb. Laryngoscope. 2018 Jun;128(6):1274–80. doi: 10.1002/lary.26908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hanna E, DeMonte F, Ibrahim S, Roberts D, Levine N, Kupferman M. Endoscopic resection of sinonasal cancers with and without craniotomy: oncologic results. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009 Dec;135(12):1219–24. doi: 10.1001/archoto.2009.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Geltzeiler M, Choby GW, Ji KS, JessMace C, Almeida JP, de Almeida J, et al. Radiographic predictors of occult intracranial involvement in olfactory neuroblastoma patients. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2023 Oct;13(10):1876–88. doi: 10.1002/alr.23145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thompson LD. Olfactory neuroblastoma. Head Neck Pathol. 2009 Sep;3(3):252–9. doi: 10.1007/s12105-009-0125-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ozsahin M, Gruber G, Olszyk O, Karakoyun-Celik O, Pehlivan B, Azria D, et al. Outcome and prognostic factors in olfactory neuroblastoma: a rare cancer network study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010 Nov;78(4):992–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bhattacharyya N, Thornton AF, Joseph MP, Goodman ML, Amrein PC. Successful treatment of esthesioneuroblastoma and neuroendocrine carcinoma with combined chemotherapy and proton radiation: results in 9 cases. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1997 Jan;123(1):34–40. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1997.01900010038005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saade RE, Hanna EY, Bell D. Prognosis and biology in esthesioneuroblastoma: the emerging role of Hyams grading system. Curr Oncol Rep. 2015 Jan;17(1):423. doi: 10.1007/s11912-014-0423-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Loy AH, Reibel JF, Read PW, Thomas CY, Newman SA, Jane JA, et al. Esthesioneuroblastoma: continued follow-up of a single institution’s experience. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006 Feb;132(2):134–8. doi: 10.1001/archotol.132.2.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Platek ME, Merzianu M, Mashtare TL, Popat SR, Rigual NR, Warren GW, et al. Improved survival following surgery and radiation therapy for olfactory neuroblastoma: analysis of the SEER database. Radiat Oncol. 2011 Apr;6:41. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-6-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ow TJ, Hanna EY, Roberts DB, Levine NB, El-Naggar AK, Rosenthal DI, et al. Optimization of long-term outcomes for patients with esthesioneuroblastoma. Head Neck. 2014 Apr;36(4):524–30. doi: 10.1002/hed.23327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Patil VM, Joshi A, Noronha V, Sharma V, Zanwar S, Dhumal S, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy in locally advanced and borderline resectable nonsquamous sinonasal tumors (esthesioneuroblastoma and sinonasal tumor with neuroendocrine differentiation) Int J Surg Oncol. 2016;2016:6923730. doi: 10.1155/2016/6923730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kim DW, Jo YH, Kim JH, Wu HG, Rhee CS, Lee CH, et al. Neoadjuvant etoposide, ifosfamide, and cisplatin for the treatment of olfactory neuroblastoma. Cancer. 2004 Nov;101(10):2257–60. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]