Abstract

We previously reported that mitogenic activation of porcine peripheral blood mononuclear cells resulted in production of porcine endogenous retrovirus(es) (PERV[s]) capable of productively infecting human cells (C. Wilson et al., J. Virol. 72:3082–3087, 1998). We now extend that analysis to show that additional passage of isolated virus, named here PERV-NIH, through a human cell line yielded a viral population with a higher titer of infectious virus on human cells than the initial isolate. We show that in a single additional passage on a human cell line, the increase in infectivity for human cells is accounted for by selection against variants carrying pig-tropic envelope sequences (PERV-C) as well as by enrichment for replication-competent genomes. Sequence analysis of the envelope cDNA present in virions demonstrated that the envelope sequence of PERV-NIH is related to but distinct from previously reported PERV envelopes. The in vitro host range of PERV was studied in human primary cells and cell lines, as well as in cell lines from nonhuman primate and other species. This analysis reveals three patterns of susceptibility to infection among these host cells: (i) cells are resistant to infection in our assay; (ii) cells are infected by virus, as viral RNA is detected in the supernatant by reverse transcription-PCR, but the cells are not permissive to productive replication and spread; and (iii) cells are permissive to low-level productive replication. Certain cell lines were permissive for efficient productive infection and spread. These results may prove useful in designing appropriate animal models to assess the in vivo infectivity properties of PERV.

Clinical trials are ongoing to test the feasibility of using porcine cells or tissues as a viable alternative to the transplantation of their human counterparts. These trials are intended to form the groundwork for the general use of pig-derived cells or organs as a means to circumvent the increasingly inadequate supply of human organs. The impending application of porcine to human xenotransplantation on a widespread basis brings with it the possibility of introducing an infectious agent from the pig into the xenograft recipient and, ultimately, to the public. Extensive screening of source animals may provide animals free of certain exogenous agents. However, endogenous agents and those agents that current detection strategies do not identify may still be harbored in the porcine xenograft. For this reason, there is renewed interest in studying the biology of porcine endogenous retroviruses (PERVs).

We have previously shown that mitogenic activation of primary peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) of pigs results in the release of PERV(s) directly infectious for human cells (18). Other reports have shown that the pig kidney cell lines PK-15 and MPK spontaneously express retrovirus infectious for pig cells (2, 6, 11, 15), and later it was shown that the PK-15-derived virus could also infect human cell lines (11). More recently, it was also demonstrated that primary cultures of porcine endothelial cells spontaneously express PERVs capable of infecting human cells (7).

To gain insight into the in vivo biology and potential for PERV pathogenesis, it is critical to develop an animal model. Inherent in this process is the need to know what species are susceptible to infection by PERV. Analysis of in vitro susceptibility is a cost-effective and rapid way to screen a number of different species in order to make a more informed choice on an appropriate in vivo model. However, in vitro infection may not always correlate to in vivo infectivity. For example, gibbon ape leukemia virus can infect rat cell lines in vitro (16, 19), but rats are not susceptible to infection in vivo (3). Alternatively, a species may be susceptible to infection in vivo, but a derivative cell line(s) may not be sensitive to infection by a given virus. As one example, mice are the natural host for Moloney murine leukemia virus, yet certain murine cell lines, such as a nonpermissive murine teratocarcinoma cell line (10), will not support replication in vitro.

Host range analyses initially showed that PERVs are restricted in their species tropism, infecting only porcine cells and not cell lines derived from a range of species including chimpanzee, rhesus monkey, horse, mink, bat, rabbit, cow, cat, dog, and mouse (15). Subsequent molecular analysis of the envelope-coding sequences of PERV has demonstrated that there are at least three different classes of envelope, currently named A, B, and C (1, 4, 13). Takeuchi and coworkers (13) generated pseudotypes composed of murine leukemia virus retroviral vector genomes and core proteins bearing different PERV-derived envelope glycoproteins in order to determine what cell types express functional receptors for PERVs bearing any one of these three classes of envelope. Their studies demonstrated that cell lines derived from mink, mouse, rat, rabbit, bat, hamster, dog, and cat were susceptible to infection by one or more of the pseudotypes bearing one of these three classes of PERV envelopes (13). While these data demonstrate that a functional receptor for one of the three PERV envelopes exists on those cell lines, they do not necessarily imply that all cells examined are permissive for viral replication.

In this study, we have used a combination of pseudotypes and wild-type virus to determine whether susceptibility to infection by PERV pseudotype correlates with permissiveness to productive replication by PERV. We used this approach to analyze a range of human and nonhuman primary cells and cell lines. The results presented here have implications for development of appropriate approaches for monitoring recipients of porcine xenotransplants as well as for the analysis of candidate animal models for studying the in vivo infection properties of PERV.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Primary cells and cell lines.

The cell lines used in this study were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) unless otherwise indicated. 293 human embryonic kidney (ATCC CRL-1573), MMK Mus musculus molossinus kidney (ATCC CRL-6439; no longer available), and SC-1 mouse embryo epithelial (ATCC CRL-6450) cells, MDTF Mus dunni tail fibroblasts (kindly provided by Olivier Danos), NRK normal rat kidney cells (ATCC CRL-6509), Rat-2 rat embryo fibroblasts (ATCC CRL-1764), SIRC rabbit corneal fibroblasts (ATCC CCL-60), D17 canine oseosarcoma (ATCC CRL-6248), MDBK bovine kidney epithelium (ATCC CCL-22), FRhK4 rhesus monkey kidney (ATCC CRL-1688), Mv1Lu mink lung epithelial (ATCC CCL-64), and MiCL.1 (S+L−) mink lung (ATCC CCL-64.1) cells, Fc3TG feline tongue fibroblasts (ATCC CCL 176), and AK-D feline lung epithelial (ATCC CCL-150), CRFK feline kidney epithelial (ATCC CCL-94), CaKi-1 clear cell kidney carcinoma (ATCC HTB-46), HeLa cervical adenocarcinoma (ATCC CCL-2), HOS human osteosarcoma (ATCC CRL-1543), and CaCO-2 colorectal adenocarcinoma (ATCC HTB-37) cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 2 mM glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 100 U of penicillin per ml, and 100 μg of streptomycin per ml. PG-4 feline glial cells and astrocytes (ATCC CRL 2032) were maintained in McCoy's 5A medium supplemented with 15% FBS, 2 mM glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 100 U of penicillin per ml, and 100 μg of streptomycin per ml. HepG2 hepatoblastoma (ATCC HB-8065) and HT1080 fibrosarcoma (ATCC CCL-121) cells were maintained in Eagle's modified essential medium supplemented in a similar manner. The following cell lines were maintained in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FBS, 2 mM glutamine, 0.05 mg of gentamicin sulfate per ml, and 1× nonessential amino acids (Biofluids, Rockville, Md.): Molt 4 acute lymphoblastic (ATCC CRL-1582), Daudi Burkitt's lymphoma (ATCC CCL-213), Raji Burkitt's lymphoma (ATCC CCL-86), and U937 histiocytic lymphoma (ATCC CRL 1593.2) cells, UCLA-SO-M14 T cells (12), and human natural killer YTN10 (20) cells.

Derivation of viral pseudotypes.

Cells productively infected with PERV-NIH, derived originally from activated PBMC of NIH minipigs (pPBMC) (18), were superinfected with retrovirus vector-containing supernatant harvested from PA317/G1BgSvN (9) in a manner similar to that previously described (5). The resulting PERV pseudotypes carry the murine retrovirus genome, G1BgSvN, coated by PERV core and envelope proteins. G1BgSvN-containing cells were selected in 187 μg of G418 (active component) per ml. After 10 to 14 days of selection, G418-resistant colonies were pooled and used to generate viral pseudotypes. Since the G1BgSvN vector genome contains the coding sequences for both neomycin phosphotransferase and β-galactosidase (9), pseudotype infection can be monitored by the acquisition of target cell resistance to G418 or by immunohistochemical detection of target cells expressing β-galactosidase.

EM examination for enumeration of virus particles.

Ten-milliliter aliquots of virus-containing supernatants were prepared for electron microscopic (EM) examination by ultracentrifugation through a 20% sucrose cushion in 50 mM Tris (pH 8.0) at 150,000 × g. Viral pellets were resuspended in 100 μl of Dulbecco modified Eagle medium without additives, representing a 100-fold concentration of the samples. Samples were prepared for and examined by negative stain transmission EM by Advanced Biotechnologies, Inc. (Columbia, Md.), to determine particle counts.

Infectivity assays.

Supernatant infections were used to determine the infectivity of cell-free virus derived from different producer cell lines. Comparisons between fresh and frozen virus-containing supernatants demonstrated that storage of viral supernatants at −70°C resulted in >100-fold decrease in infectious titer (data not shown). Therefore, all experiments were performed with freshly harvested supernatant. On the day prior to initiation of an infectivity assay, target cells were seeded at 3 × 104 to 5 × 104 cells per well in 12-well dishes. On the next day, supernatants from confluent cultures of virus producer cells were harvested, filtered through a 0.45-μm-diameter filter, adjusted to 6 μg of Polybrene per ml, and used to replace the medium on target cells. On the following day, the cells were fed with fresh medium. When β-galactosidase expression was used to monitor infectivity, the cells were fixed and histochemically stained 48 to 72 h after exposure to viral supernatant and observed microscopically to enumerate blue-staining focus-forming units (BFU) per milliliter as previously described (17). If the experiment was performed to assess productive infection of the target cell, the cells would be passaged one or two times per week as needed during the course of the experiment and monitored as described below.

The coculture of target cells with virus producer cells was used to assess the ability of the virus to be transmitted to nonadherent cells. Since several different cell types were used as a source of virus producer cells in these experiments, the dosage of irradiation required to ensure that the virus producer cells would die within 5 days after irradiation was first determined. For this, 3 × 106 to 4 × 106 cells for each virus-producer cell line were exposed to 2,000, 5,000, or 10,000 rads (using a 137Cs source [Nordion GammaCell 1000]) and seeded into a 96-well plate at 2 × 105 to 3 × 105 cells/well. Irradiated and control nonirradiated cells were monitored for proliferation daily for 5 days by measuring [3H]thymidine uptake after cells were cultured for 8 h with 1.0 μCi of [3H]thymidine (6.7 Ci/mmol; Dupont NEN, Boston, Mass.), harvested onto glass filters (Skatron, Sterling, Va.), placed in scintillant, and counted (Wallac, Turku, Finland). The lowest irradiation dose where no proliferation was measured during the 5 days of assay was used in the coculture experiments; Daudi cells received 2,000 rads, Molt 4 cells received 5,000 rads, and U937 cells received 7,000 rads.

When the target cells in the coculture were human PBMC (hPBMC), the mononuclear layer was collected from a buffy coat from a human donor separated by lymphocyte separation medium (Organon Teknika, Durham, N.C.). Cells were stimulated in 1× phytohemagglutinin (PHA) as instructed by the manufacturer (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, Md.) for 3 days and then mixed in a 1:1 ratio with 3 × 106 lethally irradiated virus producer cells in 12-well dishes. Thereafter, the cocultures were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 10% purified human interleukin-2 (IL-2; Boehringer Mannheim), 10 ng of recombinant human IL-2 (Chiron Corporation, Emeryville, Calif.) per ml, 2 mM glutamine, 100 U of penicillin per ml, and 100 μg of streptomycin per ml. Control wells containing only irradiated virus producer cells were monitored for cell viability by visualizing samples microscopically for trypan blue exclusion. Cocultures containing 293 cells as target cells were carried out in parallel as a control for the infectivity of the virus producer cells. The day after initiation of the coculture, the medium was replaced with fresh medium and cells were subcultured once or twice per week as needed. Cocultures containing the hPBMC as targets were reinfused every 2 weeks with freshly stimulated hPBMC from the same buffy coat of cells.

Methods used to monitor virus infection of target cells.

Infection of target cells was assessed by one of three methods. All infectivity experiments included parallel mock-infected cultures as negative controls that were subject to the same analyses as virus-exposed cultures. In some cases, the titer of infectious virus pseudotypes was determined by β-galactosidase expression. Cells were histochemically stained 48 to 72 h after exposure to virus-containing supernatant, and titers (BFU per milliliter) were determined. Those titers were then normalized to the titer observed on 293 cells exposed to the same viral supernatant and are reported as percentage of control. The titer observed on 293 cells ranged from several hundred to 3,000 BFU/ml in different experiments.

Periodic samples of the supernatant from confluent cultures for reverse transcriptase (RT) activity were used to monitor infection of wild-type viruses. Supernatant samples were examined for RT activity as previously described (18).

RT-PCR analysis was used to assess the presence of viral RNA in cells exposed to PERV. RNA was extracted from cell culture supernatant by using RNA STAT 50-LS (Tel-Test “B”, Inc., Friendswood, Tex.) and coprecipitated with 6.6 μg of tRNA. RNA was reverse transcribed with SuperscriptII as instructed by the manufacturer (Life Technologies), using 50 ng of random primers (Life Technologies). The cDNA was then amplified by PCR using primers specific to the pol region of the virus genome (GenBank accession no. AF033259), PB906 (5′ ACGTACTGGAGGAGGGTCACCTGA 3′) and PB908 (5′ GTCCCGAACCCTTATAACCTCTTG 3′). The PCR products were fractionated on a 1% agarose gel, followed by Southern blotting and hybridization of the amplified products, using conditions as previously described (18).

Molecular analysis of envelope cDNAs.

Virus was concentrated from 100 ml of supernatant from PERV-NIH-1° or PERV-NIH-3° or PERV-NIH-2° virus producer cell lines by centrifugation of precleared cell supernatant as described elsewhere (17). The virus pellet was solubilized in RNA STAT-60 (Tel-Test “B”), extracted (according to the manufacturer's instructions), and coprecipitated with 6.6 μg of tRNA. Viral RNA was reverse transcribed as described above. To determine the envelope subgroup specificity of the envelope cDNA, the following primer pairs were used in a PCR: PL170 and PL171 for detection of PERV-A (GenBank accession no. Y12238) (4); PL-172 and PL-173 for detection of PERV-B (GenBank accession no. Y12239) (4); and MSL-1 (5′ CTGACCTGGATTAGAACTGGAAGC 3′) and MSL-2 (5′ AGAGGATGGTCCTGGTCCTTGGGA 3′) for detection of PERV-C (GenBank accession no. AF038600) (1). The fragments were amplified as follows: 30 cycles at 94°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min after an initial 1-min denaturation step at 94°C After fractionation of the PCR products on an agarose gel, the DNA fragments were immobilized onto Nytran by Southern blot transfer and hybridized under the following conditions. For detection of PERV-A envelope-specific sequences, a PCR fragment derived by amplification of an envelope expression plasmid by using primers PERVenv3 (5′ CTTTTGACCACACCAACGGCTGTG 3′) and PERVenv4 (5′ CCTTTCATTCCC CACTACTTGTC 3′) (GenBank accession no. Y12238) was gel purified, nick translated, and hybridized in Hybrisol at 42°C. The blot was then washed in 2× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate)–with 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) at room temperature for 15 min, followed by washing in 0.1× SSC–0.1% SDS at 65°C for 15 min. For detection of PERV-B-specific (GenBank accession no. Y12239) and PERV-C-specific (GenBank accession no. AF038600) sequences, the oligonucleotides PERV-B (5′ GGGACGAGGGTCCACTTTAACCATTCGCCTTAGGATAGAG 3′) and MSL-3 (5′ CAGCTGGAGCCTCCAATGGCTATAGGACCAAATACGGTC 3′), respectively, were end labeled with [γ-32P]dATP by using T4 polynucleotide kinase. The oligonucleotide probes were hybridized in 6× SSC–10 mM NaH2PO4–0.4% SDS–500 g of sheared DNA per ml at 42°C and then washed in 6× SSC–0.1% SDS at room temperature for 15 min and at 65°C for 15 min. Hybridizing DNA fragments were then visualized with a PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics).

For sequence analysis of the envelope cDNAs, a region encoding the envelope was amplified by using PCR primers from conserved regions in the noncoding regions flanking the envelope-coding region, based on an alignment of the PERV-A and PERV-B sequences (4). PERVenv1 (sense, nucleotides 124 to 144, GenBank accession no. Y12238, 5′ ACCTCGAGACTCGGTGGAAG 3′) and PERVenv2 (antisense, nucleotides 2282 to 2259, GenBank accession no. Y12238, 5′ CTGGGTTCTGGGAGGGTTAGGTTG 3′) were used to amplify viral cDNA for 30 cycles at 94°C for 30 s, 60°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min after an initial 1-min denaturation step at 94°C. PCR products were separated on a 1.0% agarose gel, and DNA fragments of 2 to 2.5 kb were purified by using a Qiaex gel purification kit (Qiagen, Valencia, Calif.). Purified PCR products were then cloned into the TA vector by using a TA cloning kit (InVitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.). Restriction analysis of clones derived from the TA vector was used to ensure the presence of a 2- to 2.5-kb insert. At least four representative clones were chosen for sequence analysis. All deoxynucleotide sequencing was performed by the Mayo Clinic Molecular Biology Core on a Perkin-Elmer ABI PRISM 377 DNA sequencer (with XL upgrade) with the ABI PRISM dRhodamine Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction kit with AmpliTaq DNA polymerase (PE Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.). The ClustalW multiple sequence alignment program of MacVector 6.0.1 (Oxford Molecular Group) was used to compare the deduced envelope amino acid sequences.

RESULTS

Passage of a primary isolate of PERV in human 293 cells.

Activated pPBMC were cocultured with human embryonic kidney 293 cells that became productively infected after 40 to 50 days (18). We have named the virus produced by the infected 293 cells PERV-NIH-1° and used these cells to passage virus to naive 293 cells to generate virus referred to here as PERV-NIH-2°. A murine leukemia virus-based retroviral vector genome, G1BgSvN (9), encoding β-galactosidase and neomycin phosphotransferase, was introduced into both sets of the 293 virus producer cells to generate virus pseudotypes carrying a PERV-NIH wild-type genome and/or the G1BgSvN vector genome (see Materials and Methods). Exposure of target cells to the pseudotypes allows for quantitative assessment of infectious titer by detection of β-galactosidase-expressing blue-staining cells after exposure to a chromogenic substrate. We were then able to use the expression of β-galactosidase to quantitatively assess the relative infection efficiency of virus pseudotype produced after initial and secondary passage of PERV through a human cell line. To analyze whether additional passage of PERV through human cells might select for a virus or population of viruses that would more efficiently infect human cells, we exposed human 293 cells to PERV-NIH-1° or PERV-NIH-2° pseudotype-containing supernatant. As shown in Table 1, in three experiments, the infectious titers on 293 cells of PERV-NIH-2° pseudotypes were approximately four- to fivefold higher than those observed for the PERV-NIH-1° pseudotypes.

TABLE 1.

Comparison of infectious titers on 293 cells of PERV-NIH pseudotypes containing the G1BgSvN genome

| Expt | BFU/ml on 293 cells (avg ± SD)

|

Fold difference in titer | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PERV-NIH-1° | PERV-NIH-2° | ||

| 1a | 466.67 ± 57.73 | 2,230 ± 195.2 | 4.7 |

| 2b | 233.5 ± 89.8 | 1,155 ± 205.1 | 4.9 |

| 3c | 360 | 1,383 ± 632 | 3.8 |

Values shown are averages from triplicate wells.

Values shown are averages from duplicate wells.

Values for PERV-NIH-1° were determined from a single well; values for PERV-NIH-2° are from duplicate wells.

A likely explanation for these observed differences is that the PERV-NIH-1° virus producer cells carry a higher percentage of defective genomes relative to the PERV-NIH-2° virus producer cells, which would account for the lower titer of infectious PERV-NIH-1° virus when exposed to 293 target cells. To assess this possibility, we infected 293 cells with supernatant from the PERV-NIH-1° and PERV-NIH-2° pseudotype producer cell lines. For each supernatant, samples of input viral supernatant were retained for analysis of RT activity and for particle count determination by negative strain transmission EM. As shown in Table 2, particle count enumeration revealed that PERV-NIH-2° supernatant contained twofold more particles than PERV-NIH-1° supernatant, while the incorporation of [3H]TTP (a measure of RT activity) was 4.2-fold higher and there was an 8.4-fold difference in infectivity titer on 293 cells.

TABLE 2.

Comparison of RT activities, EM particle counts, and infectious titers of PERV-NIH-1° and PERV-NIH-2° pseudotypes containing the G1BgSvN genome

| Virus pseudotype | EM particle count (107/ml) | [3H]TTP incorporated (cpm)a | BFU/ml on 293 cells (avg ± SD)b |

|---|---|---|---|

| PERV-NIH-1° | 1.4 | 149,510 | 137 ± 14.4 |

| PERV-NIH-2° | 2.8 | 631,365 | 1,153.6 ± 102.6 |

| Fold difference | 2 | 4.2 | 8.4 |

In supernatant used to expose 293 cells.

Average from quadruplicate wells infected with a 1:5 dilution of viral supernatant.

Analysis of envelope class and coding sequence.

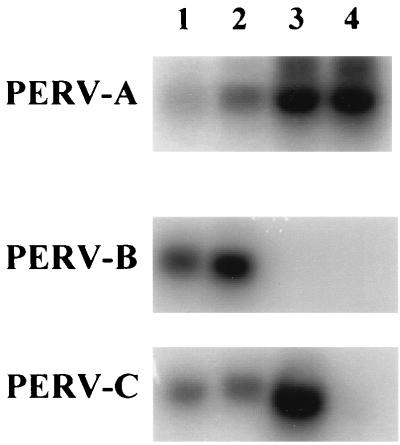

Presence of the PERV-C envelope in PERV-NIH-1° virions may account for the discrepancy in the particle/infectivity ratios, since pseudotypes carrying PERV-C envelopes cannot infect 293 cells (13). Complementary DNA was synthesized from the RNA of pelleted virions collected from supernatants of PERV-NIH-1° and PERV-NIH-2° producer cells. As controls, cellular RNA was also isolated from pPBMC directly isolated from a Ficoll-Hypaque gradient (unactivated) and from pPBMC activated in PHA and phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) for 5 days as previously described (18). Oligonucleotide primers capable of specifically amplifying each of the PERV envelope classes previously reported were used to amplify the cDNAs. Products were then hybridized with probes specific for each of the three envelope classes to enhance the detection sensitivity (Fig. 1). A product was detected for all three envelope classes in both unactivated and activated pPBMC (Fig. 1, lanes 1 and 2). The PERV-A-specific primers and probe detected a PCR product in cDNA from both PERV-NIH-1° and PERV-NIH-2° virions. No product was observed with PERV-B-specific primers or probes in either set of cDNAs, although PERV-B sequences were detected in cDNAs synthesized from both unstimulated and PHA- and PMA-stimulated pPBMC. The PERV-C-specific primers and probe generated a product from the PERV-NIH-1° cDNA but not the PERV-NIH-2° cDNA.

FIG. 1.

Detection of PERV envelope classes by RT-PCR of virion RNA. Viral RNA was examined by RT-PCR from cell lysate derived from unactivated pPBMC (lane 1) or pPBMC activated with PHA and PMA (lane 2) (18) or pelleted virions of PERV-NIH-1° (lane 3) or PERV-NIH-2° (lane 4), using primers specific for each of the envelope classes indicated. Each primer-specific reaction was fractionated on a 1% agarose gel, transferred to nitrocellulose, and then hybridized to probes specific for each PERV envelope class listed on the left (see Materials and Methods). The hybridized products were visualized with a PhosphorImager.

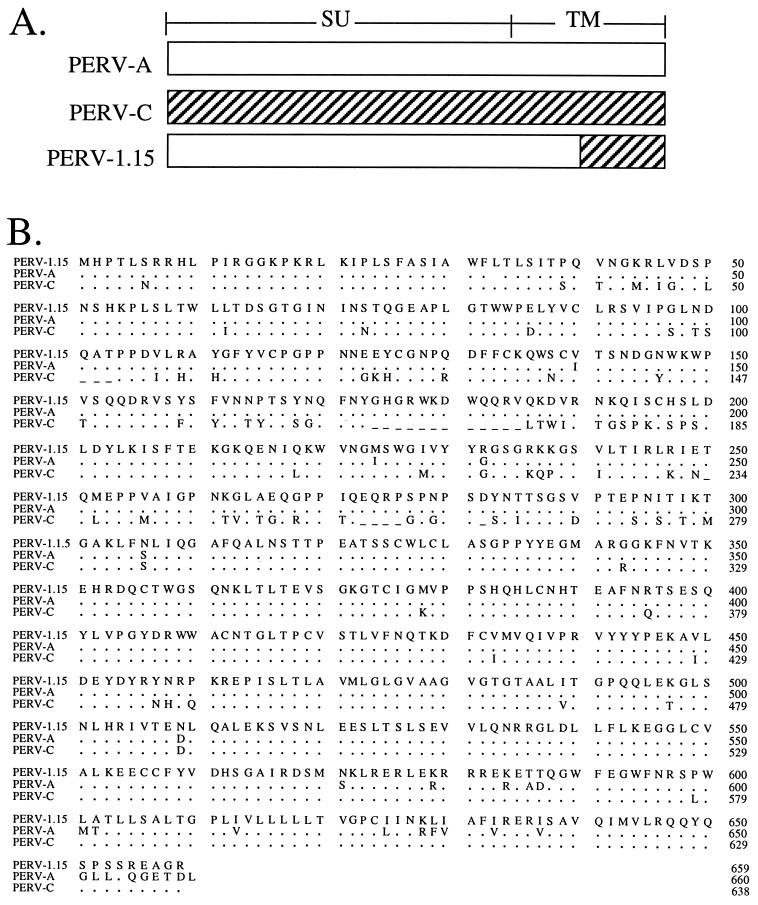

We then examined whether subtle progressive changes in the envelope-coding region may also contribute to the change in infectivity properties of PERV-NIH-1° relative to PERV-NIH-2°. Of the four representative clones sequenced from PERV-NIH-1°-derived PCR amplicons, three had full open reading frames, and three of six from the PERV-NIH-2°-derived PCR amplicons had full open reading frames. Sequence analysis showed that while each amplicon had nucleotide changes resulting in alterations in the deduced amino acid sequence, the predominant envelope expressed in all three virion preparations is essentially the same. Figure 2 shows an alignment of the deduced amino acid sequence from a representative clone, 1.15, derived from cDNA of the PERV-NIH-1° preparation of virions with the previously reported sequences for the PERV-A and PERV-C envelopes. The alignment shows that the surface glycoprotein (SU) portion of the envelope is most similar to the PERV-A class of envelope (4), while the C-terminal 90 amino acid residues of the transmembrane region are almost identical to the PERV-C class of envelope while sharing only 75% amino acid identity with PERV-A (1) (Fig. 2). The other clones examined contained nucleotide changes resulting in altered amino acids in three or four positions; of these, only one or two were in SU. Since each clone was unique with respect to the changes observed, these alterations most likely represent either PCR-induced mutations or the naturally occurring variance of the virus populations present in the two virus producer cell lines. No change at any specific amino acid residue was ever observed in more than one clone, suggesting that there was not a selection for a particular envelope, other than the shift from a mix of PERV-C and PERV-A in the PERV-NIH-1° virus population to only PERV-A-like envelopes in the PERV-NIH-2° population (Fig. 1).

FIG. 2.

Comparison of amino acid residues encoded by clone 1.15-derived cDNA of 293/PERV-NIH-1° virions (PERV-1.15), PERV-A, and PERV-C. (A) Schematic representation of regions of the PERV-1.15 envelope homologous to PERV-A (hatched) and PERV-C (open) genes. (B) Deduced amino acids for the envelope surface glycoprotein (SU; amino acids 1 to 460) and transmembrane (TM; amino acids 461 to 659) regions of clone 1.15 derived from cDNA of PERV-NIH-1° virions (GenBank accession no. AF130444) compared to PERV-A and PERV-C. Identical amino acids are denoted by dots; gaps are denoted by dashes.

Analysis of species tropism of PERV.

PERV pseudotypes were used for an initial screen for susceptibility to infection in a broad range of cell lines derived from several different species. Target cells were exposed to the PERV-NIH-2° pseudotype supernatant, and titers were determined after histochemical staining for β-galactosidase-expressing cells. The relative titers observed on the tested cell lines normalized to the titers observed on 293 cells are shown in Table 3. Cell lines derived from mouse, rat, rabbit, dog, cow, and rhesus monkey were resistant to infection by PERV-NIH-2° pseudotypes relative to 293 positive controls, while cell lines derived from cat or mink were susceptible to infection, as measured by this assay. The relative susceptibility of mink and cat cell lines was low compared with human 293 cells, with the exception of the MiCl.1 and PG-4 cell lines.

TABLE 3.

Relative susceptibility of nonhuman cell lines to infection by PERV-NIH-2°-derived PERV pseudotypes

| Species of origin | Cell line | % Controla |

|---|---|---|

| Mus musculus molossinus | MMK | 0 |

| M. musculus | SC-1 | 0 |

| M. dunni | MDTF | 0 |

| Rat | NRK | 0 |

| Rat | Rat-2 | 0.1 |

| Rabbit | SIRC | 0 |

| Dog | D17 | 0 |

| Cow | MDBK | 0 |

| Rhesus monkey | FRhK4 | 0 |

| Mink | Mv1Lu | 18, 53 |

| MiCL.1 | 5 | |

| Cat | PG-4 | 81, 90 |

| Fc3TG | 3, 6 | |

| AK-D | 1.3, 1.6 | |

| CRFK | 7, 6.1 |

Results were normalized to the infectivity titer observed on 293 cells exposed to the same PERV-NIH-2°-containing supernatant (see Materials and Methods). Titers on 293 cells varied from 500 to 3,000 BFU/ml in different experiments. In those cases where 0 is reported, no β-galactosidase-positive cells were observed after exposure of 30,000 to 40,000 cells to 1.0 ml of virus-containing supernatant. In those where a second independent experiment was carried out to verify the result, the results from both experiments are shown.

To investigate whether cell lines susceptible to infection by PERV pseudotypes could also be productively infected by PERV, the mink and feline cell lines were exposed to PERV-NIH-2° supernatant and monitored for RT activity. 293 cells were exposed to the same supernatant as a positive control for these experiments. In addition, cell supernatants of target cells were monitored for low-level virus production by RT-PCR to detect viral RNA. As shown in Table 4, PERV-NIH-2°-derived virus did not infect any of the cell lines examined as efficiently as control 293 cells, although all cells were positive by RT-PCR after exposure to the PERV-NIH-2° virus supernatant. Only low levels of RT activity were observed in the MiCL.1 and CRFK cultures, while RT activity was not above background levels in the other target cells exposed to PERV. The PG-4 cultures resulted in a peak level of RT activity of 9,733 cpm of [3H]TTP incorporated at 3 weeks that by 5 weeks was reduced to 2,344 cpm of [3H]TTP incorporated.

TABLE 4.

Susceptibility of nonhuman cell lines to productive infection by PERV-NIH-2°

| Cell line | Time (wk) postexposurea | [3H]TTP incorporated (cpm)b | Signal by RT-PCRc |

|---|---|---|---|

| 293 | 1 | 43,609 | |

| 3 | 19,526 | ND | |

| Mv1Lu | 1 | Bkgd | |

| 3 | Bkgd | ||

| 6 | 1,090 | ||

| 8 | 3,548 | + | |

| PG-4d | 1 | Bkgd | |

| 3 | 9,733 | ||

| 5 | 2,344 | ND | |

| CRFK | 1 | Bkgd | |

| 4 | 1,929 | ||

| 6 | 1,716 | ||

| 8 | 1,306 | + | |

| AK-D | 2 | ||

| 6 | |||

| 8 | Bkgd | + | |

| Fc3TG | 2 | ||

| 6 | |||

| 8 | Bkgd | + |

Cells were exposed to supernatant from PERV-NIH-2° producer cells.

Values shown are from an RT assay performed as previously described (18), with background values subtracted. The background value is obtained from a matched uninfected control assayed at the same time point as the culture exposed to virus. If the value observed for the virus-exposed culture is <2-fold greater than the background value, it is reported as Bkgd.

The 8-week cell supernatant was examined for the presence of viral RNA by RT-PCR as described in Materials and Methods. ND, not determined.

PG-4 cells were exposed to a 1:2 dilution of PERV-NIH-2° supernatant. 293 cells exposed to the same preparation of supernatant had RT values at 1 and 5 weeks of 7,629 and 43,733 cpm of [3H]TTP incorporated, respectively.

Analysis of the susceptibility of human adherent cell lines to infection by PERV.

A range of human cell lines derived from different tissue or cell types were exposed to PERV-NIH-2° pseudotypes and assayed for β-galactosidase expression. All of the cell lines examined except CaKi-1 were susceptible to various degrees to infection as measured by β-galactosidase expression (Table 5). For example, the PERV pseudotype titer observed on HOS or HeLa cells was 20- to 100-fold lower than that observed on 293 cells, while the pseudotype titer observed on HepG2 or HT1080 cells was in the same range as that observed on 293 cells. When cells were exposed to PERV pseudotype supernatant and cultured for 8 weeks, only HepG2 and HT1080 cells were permissive to productive infection as determined by RT assay, but the levels of RT activity were quite low relative to those measured in control 293 cultures (Tables 4 and 5).

TABLE 5.

Relative susceptibility of human adherent cell lines to infection by PERV-NIH-2° pseudotypes

| Origin | Cell line | % Controla | [3H]TTP incorporated (cpm)b | Signal by RT-PCRc |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clear cell kidney carcinoma | CaKi-1 | 0 | NDd | ND |

| Cervical adenocarcinoma | HeLa | 1 | ND | ND |

| Osteosarcoma | HOS | 3.6 | ND | ND |

| Hepatoblastoma | HepG2 | 90 | 6,201 | + |

| Fibrosarcoma | HT1080 | 39 | 1,237 | + |

| Colorectal adenocarcinoma | CaCO-2 | ND | Bkgd | + |

Results were normalized to the infectivity titer observed on 293 cells exposed to the same PERV-NIH-2° pseudotype-containing supernatant (see Materials and Methods). Titers on 293 cells varied from 500 to 3,000 BFU/ml in different experiments. In the case where 0 is reported, no β-galactosidase-positive cells were observed after exposure of 30,000 to 40,000 cells to 1.0 ml of virus-containing supernatant.

Values shown are for cell supernatant from cultures maintained for 8 weeks, determined in an RT assay performed as previously described (18), with background values subtracted. The background value is obtained from a matched uninfected control assayed at the same time point as the culture exposed to virus. If the value observed for the virus-exposed culture is <2-fold greater than the background value, it is reported as Bkgd.

The 8-week cell supernatant was examined for presence of viral RNA by RT-PCR as described in Materials and Methods.

ND, not determined.

Analysis of the susceptibility of human hematopoietic cells to infection by PERV.

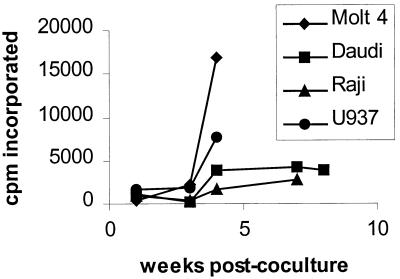

To assess whether primary hPBMC were susceptible to infection by PERV, PHA-activated hPBMC were cocultured with irradiated PERV-NIH-2° producer cells and maintained in IL-2-containing medium for 8 weeks (see Materials and Methods). No RT activity above background levels or viral RNA as measured by RT-PCR was detected during the course of the experiment (data not shown). Since maintenance of the PHA-activated hPBMC in IL-2 during the course of the experiment biases the culture conditions toward the proliferation of T cells, other hematopoietic lineages that are susceptible to infection may not have been represented. To investigate the possibility that other hematopoietic lineages would be permissive for infection, a number of human hematopoietic cell lines representing the T-cell, B-cell, myeloid, and NK cell lineages were analyzed for susceptibility to PERV infection by coculture with irradiated 293/PERV-NIH-2° producer cells. Supernatants from the cocultures containing either M14 (T-cell lineage), Jurkat (T-cell lineage), or K562 (myeloid lineage) cells or the NK cell line YTN10 remained negative for RT activity during the 8-week course of the experiment, although viral RNA could be detected by RT-PCR throughout the experiment (data not shown). Figure 3 shows RT activity for the cocultures containing the T-cell line Molt 4, the B-cell lines Daudi and Raji, and the myeloid cell line U937. By 4 weeks postcoculture, the RT activity in the Molt 4- and U937-containing cocultures was positive and continued progressively to increase throughout the period of the coculture. In contrast, the RT activity for both the Raji and Daudi sets of cocultures plateaud by 4 weeks postculture and never rose to a level comparable to that for either the Molt 4 or U937 coculture. The results from this experiment suggest that the Molt 4, Daudi, Raji, and U937 cell lines were permissive for productive infection by PERV.

FIG. 3.

RT activity observed in cocultures of 293/PERV-NIH-2° producer cells and human hematopoietic cell lines. Data points represent [3H]TTP incorporated in an RT assay measured in cell supernatants sampled at the times indicated after coculture of 293/PERV-NIH-2° producer cells with each of the cell lines indicated. Values of [3H]TTP incorporation for parallel mock-infected controls were subtracted from the values obtained in matched cocultures.

We then cocultured the RT-positive hematopoietic cell lines with primary hPBMC, hypothesizing that a virus population that more efficiently infects primary hematopoietic cells may have been selected in the susceptible hematopoietic cell lines. Before initiating this experiment, we determined the conditions optimal for lethal irradiation for each of the RT-positive Daudi, Molt 4, and U937 cell lines as described in Materials and Methods. We then used lethally irradiated RT-positive Daudi, Molt 4, and U937 cells as virus producer cells in cocultures with primary hPBMC activated with PHA or with human 293 cells as positive controls. By 2 weeks postcoculture, each of the cocultures containing 293 cells as target cells became significantly RT positive (>7,000 cpm); by 3 weeks, the RT activity in each of these cultures increased to >20,000 cpm. In contrast, none of the cocultures containing the hPBMC demonstrated RT activity higher than that of negative control cultures over the course of the experiment. Although viral RNA was detected by RT-PCR in the supernatant of cultures sampled 1 to 2 weeks postexposure, the supernatant was negative for viral RNA by RT-PCR by 3 weeks and remained so out to the 8-week time point. The positive RT-PCR results obtained at the early time points most likely reflect presence of residual irradiated virus producer cells which disappear from the culture at the later time points, rather than infected cells.

DISCUSSION

We have pursued our initial observation that pPBMC, upon activation, release a retrovirus infectious for a human cell line with a broader analysis of the in vitro host range of the PERV population isolated from primary pPBMC. Use of pseudotypes bearing the gene for β-galactosidase allowed us to show that additional passage of the initial PERV isolate (PERV-NIH-1°) through a human cell line produced a virus (PERV-NIH-2°) with an approximately four- to eightfold increase in titer on human 293 cells relative to the PERV-NIH-1° virus.

In an effort to understand the mechanism for the observed increase in titer of infectious virus present in the PERV-NIH-2° supernatants relative to the PERV-NIH-1° supernatant, we examined several aspects of the viral populations present. We found that the particle counts of the two supernatants were only twofold different whereas RT activities were fourfold different, demonstrating that there is a higher rate of defective particles present in the PERV-NIH-1° supernatant (i.e., particles detected by EM that may be RT negative). However, the additional observation that the PERV-NIH-2° virions had enhanced infectivity on 293 cells even greater than the difference in RT activity (eightfold difference in infectious titer) suggested an additional mechanism. Indeed, PCR analysis of the envelope class demonstrated that the second passage in 293 cells seemed to exclude the PERV-C envelope class, most likely due to the inability of virions coated with PERV-C to infect 293 cells (13). Presumably genomes encoding PERV-C were carried from the activated pPBMC into the initial 293 cells by pseudotyping. Besides the shift away from PERV-C-containing genomes, we could not detect a mutation in the envelope-coding region by sequence analysis that may also allow for the increase in infectious titer of PERV-NIH-2° virions on 293 cells. However, changes in other regions of the genome, such as the long terminal repeat or gag-pol coding regions, cannot be excluded as contributing to the enhanced infection efficiencies following passaging in human cells. Together these results suggest that a greater number of genomes that are either defective or incapable of infecting 293 cells (i.e., carrying PERV-C envelope) are present in the PERV-NIH-1° culture than in the PERV-NIH-2° culture, thus accounting for the lower titer of infectious PERV-NIH-1° pseudotypes relative to the PERV-NIH-2° pseudotypes on 293 cells.

The deduced amino acid sequence of the envelope glycoprotein derived from PERV-NIH-1° virions is similar to the previously reported PERV-A envelope sequence (4), with the exception of the C-terminal 90 amino acid residues of the TM envelope protein, which are virtually identical to those of PERV-C (1, 13). This observation demonstrates the presence of at least one additional variant of envelope in addition to those previously reported. It remains to be determined whether the envelope reported here is in the same receptor interference group as the PERV-A class, although one would expect so since the entire SU is most like that of PERV-A (4). Of the cell lines examined in our study that are common to those presented in the report of Takeuchi and coworkers, the in vitro host range of PERV-NIH is mostly in agreement with that reported for PERV-A, with the notable exception of canine D17 cells (13).

In this study, we analyzed cells from different species and tissues for in vitro susceptibility to infection by PERV-NIH-2° pseudotypes. Based on the initial assessment of infectivity by expression of β-galactosidase, we found that mouse- and rat-derived cell lines as well as cell lines derived from rabbit, dog, cow, and rhesus monkey were all resistant to infection relative to 293 cells. In contrast, of the human adherent cell lines examined, only CaKi-1, derived from a kidney carcinoma, was not susceptible to infection by PERV-NIH-2° pseudotypes. This marked difference in susceptibility to infection between the two human kidney cell lines examined, CaKi-1 and 293 cells, argues against the human tissue source as a predictor of whether a target cell is susceptible or resistant to infection by PERV-NIH-2°. The observation that 293 cells are efficiently infected while CaKi-1 cells are resistant to infection by PERV-NIH-2° may be attributable to differences in their phenotypic status. For example, the transformation of 293 cells by adenovirus and the expression of certain adenovirus proteins may alter the profile of cell surface proteins, resulting in expression of the PERV receptor which may not be expressed on kidney cells under other conditions. Alternatively, the fact that 293 cells are embryo derived whereas CaKi-1 is a tumor-derived cell line may also have an impact on the expression of cell surface proteins.

We determined that target cells that were susceptible to PERV-NIH-2° pseudotype infection as measured by β-galactosidase expression were not always productively infected, e.g., capable of producing replication-competent progeny virions. We used two tools to measure productive infection: an RT assay, which provided an insensitive assessment of viral replication, and a more sensitive RT-PCR assay. The detection of viral RNA by RT-PCR in the absence of detectable RT activity suggests low-level virus production in the absence of productive viral replication. This pattern was observed with the feline cell lines AK-D and Fc3TG, human colorectal adenocarcinoma CaCO-2 cells, the human T-cell lines Jurkat and M14, the NK cell line YTN10, and the myeloid cell line K56. These results are consistent with the conclusion that these cell lines are not permissive for productive infection. Some cell lines, such as feline CRFK, human fibrosarcoma HT1080, and the B-cell lines Daudi and Raji, were positive for RT activity. However, the activity measured in these cultures remained at low levels (i.e., <2,000 to 3,000 cpm) and did not increase during the 8-week culture period. This pattern may reflect decreased susceptibility to viral infection and/or viral replication and spread. Exposure of mink lung fibroblast Mv1Lu, feline PG-4, and HepG2 hepatoblastoma cells, the Molt 4 T-cell line, and the promyelomonocytic cell line U937 to PERV-NIH-2° virions or cells resulted in RT activity that increased over time, suggesting more efficient productive infection of these cell types. Collectively, these data suggest that PERV-NIH, isolated from activated pPBMC, is not highly infectious in vitro. However, an alternative explanation may be a lack of optimal methods for culturing the virus in vitro, and therefore these results may not reflect PERV infectivity in vivo.

One goal of this study was to survey cell lines from a variety of species to determine which species-derived target cells supported infection and replication by PERV-NIH as a first step in identifying a candidate animal model for assessing in vivo infectivity and pathogenicity. We found that the in vitro host range is quite restricted. Our analysis of a spectrum of mouse, rat, rabbit, and dog cell lines suggests that these animals would not serve as useful models. In addition, analysis of nonhuman primate cell lines described here and by others (13) suggests that nonhuman primates may not be permissive hosts for in vivo infectivity studies, assuming that our in vitro findings translate to the in vivo setting. This has been confirmed by one group who showed no evidence for infection in baboons after exposure to PERV-expressing porcine endothelial cells (8). The only cells productively infected, albeit inefficiently compared with 293 cells, were those derived from cat and mink. In vitro selection of a virus that more efficiently infects cat or mink cells may be an approach needed to enhance the development of an animal model system. For example, it was shown that after long-term passage of Rous sarcoma virus on nonpermissive quail cells, a variant that was able to infect quail cells could be isolated (14). A similar approach may be taken to isolate a variant that can more efficiently infect cells from the species of choice for analysis in that animal model.

We found no evidence for infection by PERV-NIH-2° of primary hPBMC under the culture conditions used in this study. In an extension of this analysis, we examined cell lines derived from different hematopoietic lineages and generally did not observe a correlation between susceptibility and lineage. Infection of the T-cell line Molt 4 resulted in high levels of RT activity, while the other T-cell lines examined, Jurkat and M14, were not permissive for productive infection. Similarly, the myelomonocytic cell line U937 was permissive for infection, while the myeloid cell line K562 was not. Only for B cells were both B-cell lines examined, Daudi and Raji, shown to be permissive for viral replication. These findings suggest that susceptibility to infection may be more dependent on other factors such as the means of transformation (all of these cell lines are transformed) or in vitro culture conditions, rather than lineage per se. This finding echoes the results observed for the two human kidney cell lines in this study, CaKi-1 and 293. In an effort to maximize the possibility of infecting primary cells, we used the RT-positive human hematopoietic cell lines Molt 4, Daudi, and U937 as virus producers in a coculture with human PBMC. Under the culture conditions of this experiment, the PBMC remained resistant to infection. In toto, these results underscore the need for caution in interpreting data from xenotransplant clinical trials where recipients are analyzed for evidence of infection by analysis of hPBMC for presence of proviral DNA sequences, since these cells may not be susceptible to infection in vivo.

Our analysis of the in vitro host range of PERV(es) complements and extends those analyses previously reported, for example, by Takeuchi and coworkers (13). In particular, our results demonstrate the utility of using pseudotypes for initial assessment of susceptibility to infection followed by monitoring for the spread of infection to demonstrate whether the cells are permissive for viral replication and not just for viral entry and expression. Further study is needed to understand the viral and cellular contributions to inefficient replication in vitro. In addition, these studies demonstrate that development of permissive animal models will be necessary to enhance our understanding of the in vivo infectivity properties of this virus.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Junji Yodoi, Kyoto University, for the gift of a cell line used in this study. We are grateful for technical insights provided by Judy Arcidiacono and Keizo Furuke. Finally, we thank Maribeth Eiden and Eda Bloom for helpful discussions and reviews of the manuscript.

This work was supported in part by the Siebens Foundation, under the Harold W. Siebens Research Scholar Program and the Mayo Foundation (M.J.F.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Akiyoshi D E, Denaro M, Zhu H, Greenstein J L, Banerjee P, Fishman J A. Identification of a full-length cDNA for an endogenous retrovirus of miniature swine. J Virol. 1998;72:4503–4507. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.5.4503-4507.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Armstrong J A, Porterfield J S, Madrid A T D. C-type virus particles in pig kidney cell lines. J Gen Virol. 1971;10:195–198. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-10-2-195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kawakami T G, Kollias G V, Jr, Holmberg C. Oncogenicity of gibbon type-C myelogenous leukemia virus. Int J Cancer. 1980;25:641–646. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910250514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Le Tissier P, Stoye J P, Takeuchi Y, Patience C, Weiss R A. Two sets of human-tropic pig retroviruses. Nature. 1997;389:681–682. doi: 10.1038/39489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leverett B D, Farrell K B, Eiden M V, Wilson C A. Entry of amphotropic murine leukemia virus is influenced by residues in the putative second extracellular domain of the human form of its receptor, Pit2. J Virol. 1998;72:4956–4961. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.6.4956-4961.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lieber M M, Sherr C J, Benveniste R E, Todaro G J. Biologic and immunologic properties of porcine type C viruses. Virology. 1975;66:616–619. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(75)90234-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martin U, Kiessig V, Blusch J, Haverich A, von der Helm K, Herden T, Steinhoff G. Expression of pig endogenous retrovirus by primary porcine endothelial cells and infection of human cells. Lancet. 1998;352:692–694. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)07144-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martin U, Steinhoff G, Kiessig V, Chikobava M, Anssar M, Morschheuser T, Lapin B, Haverich A. Porcine endogenous retrovirus is transmitted neither in vivo nor in vitro from porcine endothelial cells to baboons. Transplant Proc. 1999;31:913–914. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(98)01832-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McLachlin J R, Mittereder N, Daucher M B, Kadan M, Eglitis M A. Factors affecting retroviral vector function and structural integrity. Virology. 1993;195:1–5. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Niwa O. Suppression of the hypomethylated Moloney leukemia virus genome in undifferentiated teratocarcinoma cells and inefficiency of transformation by a bacterial gene under control of the long terminal repeat. Mol Cell Biol. 1985;5:2325–2331. doi: 10.1128/mcb.5.9.2325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patience C, Takeuchi Y, Weiss R A. Infection of human cells by an endogenous retrovirus of pigs. Nat Med. 1997;3:282–286. doi: 10.1038/nm0397-282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramsdell F J, Shau H, Golub S H. Role of proliferation in LAK cell development. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 1988;26:139–144. doi: 10.1007/BF00205607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Takeuchi Y, Patience C, Magre S, Weiss R A, Banerjee P T, Le Tissier P, Stoye J P. Host range and interference studies of three classes of pig endogenous retrovirus. J Virol. 1998;72:9986–9991. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.12.9986-9991.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taplitz R A, Coffin J M. Selection of an avian retrovirus mutant with extended receptor usage. J Virol. 1997;71:7814–7819. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.10.7814-7819.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Todaro G J, Benveniste R E, Lieber M M, Sherr C J. Characterization of a type C virus released from the porcine cell line PK(15) Virology. 1974;58:65–74. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(74)90141-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weiss R A, Long A L. Phenotypic mixing between avian and mammalian RNA tumor viruses. I. Envelope pseudotypes of Rous sarcoma virus. Virology. 1977;76:826–834. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(77)90262-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilson C, Eiden M. Viral and cellular factors governing hamster cell infection by murine and gibbon ape leukemia viruses. J Virol. 1991;65:5975–5982. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.11.5975-5982.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilson C, Wong S, Muller J, Davidson C, Rose T, Burd P. Type C retrovirus released from porcine primary peripheral blood mononuclear cells infects human cells. J Virol. 1998;72:3082–3087. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.4.3082-3087.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wilson C A, Farrell K B, Eiden M V. Comparison of cDNAs encoding the gibbon ape leukaemia virus receptor from susceptible and non-susceptible murine cells. J Gen Virol. 1994;75:1901–1908. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-75-8-1901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yodoi J, Teshigawara K, Nikaido T, Fukui F, Noma T, Hongo T, Takigawa M, Sasaki M, Minato N, Tsudo M, Uchiyama T, Maeda M. TCGF (IL-2)-receptor inducing factor(s). I. Regulation of IL-2 receptor on natural killer-like cell line (YT cells) J Immunol. 1985;134:1623–1630. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]