Abstract

To improve the circularity and performance of polyolefin materials, recent innovations have enabled the synthesis of polyolefins with new structural features such as cleavable breakpoints, functional chain ends, and unique comonomers. As new polyolefin structures become synthetically accessible, fundamental understanding of the effects of structural features on polymer (re)processing and mechanical performance is increasingly important. While bulk material properties are readily measured through conventional thermal or mechanical techniques, selective measurement of local material properties near structural defects is a major characterization challenge. Here, we synthesized a series of polyethylenes with selectively deuterated segments using a polyhomologation approach and employed vibrational spectroscopy to evaluate crystallization and melting of chain segments near features of interest (e.g., end groups, chain centers, and mid-chain structural defects). Chain-end functionality and defects were observed to strongly influence crystallinity of adjacent deuterated chain segments. Additionally, chain-end crystallinity was observed to have different molar mass dependence than mid-chain crystallinity. The synthesis and spectroscopy techniques demonstrated here can be applied to range of previously inaccessible deuterated polyethylene structures to provide direct insight into local crystallization behavior.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Polyethylene (PE) is the most widely produced plastic worldwide, and its production is projected to grow in the coming decades.1 Accordingly, significant effort has been devoted to improving the performance and circularity of polyethylene materials through the introduction of various structural features, including unique comonomers,2-4 functional chain ends,5-10 hetero-blocks,11-13 and cleavable mid-chain breakpoints.14-16 Modifications to polyethylene’s chemical structure affect nucleation kinetics, spherulite growth, and lamellar packing, thereby impacting the resultant thermomechanical properties of the material and defining the application space for appropriate use. However, a full understanding of the mechanisms through which structural defects affect crystallization remains a major challenge.17 Consequently, improved measurement capabilities are necessary to be able to predictively model molecular structure to achieve desired properties or enhance (re)processibility. While bulk crystallization behavior and thermomechanical properties are often readily measured through conventional techniques (e.g., differential scanning calorimetry, rheometry, tensile testing), local crystallization behavior near chain defects is difficult to observe. A technique to selectively measure conformational order of specific segments of a PE chain, therefore, is desirable to establish mechanistic relationships between chemical structure and crystallization behavior.

Isotopic labelling is a powerful approach for changing spectroscopic and scattering properties while minimally influencing thermomechanical properties.18 Deuteration, in particular, has enabled a wealth of studies of polyethylene conformation in blends of deuterated (dPE) and protiated (PE) materials using neutron scattering and vibrational spectroscopy techniques.19-28 However, studies involving selectively deuterated segments in a polyethylene chain are surprisingly scarce. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, only six such samples (PE-b-dPE and PE-b-dPE-b-PE) have been reported in total.29-32 The dearth of studies on selectively deuterated PE can likely be attributed to the cost and synthetic difficulty of preparing them. For example, the ultralong alkanes with deuterated end-segments prepared by Brooke, et al., enabled a series of detailed neutron scattering experiments, but their synthesis required 4 separate reaction steps per 12 carbons in the final product.29,33 Alternatively, synthesizing PE with selectively deuterated segments via more conventional ethylene polymerization techniques requires the use of expensive deuterated monomer and is further complicated by the difficulty of adding precise amounts of gaseous monomers.

To circumvent some of this difficulty, two previous reports have demonstrated the use of polyhomologation to introduce deuterated segments in a polyethylene chain.31,32 Polyhomologation, in which a chain grows one methylene unit at a time from an organoboron initiator, uses the sulfur-based ylide, dimethylsulfoxonium methylide, as the monomer rather than ethylene. Unlike ethylene, the precursor to the ylide is readily deuterated via protium/deuterium (H/D) exchange with commercially available D2O.31 Additionally, polyhomologation is a living polymerization technique, enabling the installation of deuterated blocks at specific points within the polymer chain through sequential addition of deuterated and protiated monomers (Scheme 1). While prohibitively expensive for commercial production of PE, polyhomologation is a powerful approach for synthesizing PE with well-defined architectures,34-40 functional chain ends,41,42 and narrow molar mass distributions31,43 that are valuable for fundamental evaluation of structure-property relationships. Despite the versatility of polyhomologation and the access it grants to selectively deuterated materials, it has not been employed to measure segment-by-segment differences in polyethylene chains. In this work, a series of selectively labeled PE samples with a range of molar masses, end groups, and mid-chain defects were synthesized, and the conformational order in immediate proximity to those defects was measured via vibrational spectroscopy. The synthesis and spectroscopy techniques presented here can be extended to a range of previously inaccessible deuterated polyethylene structures to provide direct insight into local crystallization behavior and the potential influence of chemical or architectural variance at the molecular scale.

Scheme 1.

(a) General polymerization scheme showing polyhomologation via sequential addition of protiated and deuterated monomers to an organoborane initiator. (b) Structural features with different polarity and bulkiness with adjacent deuterated segments explored in this work.

Experimental

Disclaimer.

Certain commercial equipment, software, instruments, or materials are identified in this work to specify the experimental procedure adequately. Such identification is not intended to imply recommendation or endorsement by the National Institute of Standards and Technology, nor is it intended to imply that the materials or equipment identified are necessarily the best available for the purpose.

Materials.

Toluene and tetrahydrofuran (THF) were purified using an LC Technology Solutions solvent purification system with sequential columns of 3A molecular sieves and alumina-supported copper and stored under inert atmosphere. Trimethylsulfoxonium iodide (Alfa Aesar, >98 %) was recrystallized from water and dried in vacuo prior to use. Sodium hydride (TCI, 60 % dispersion in mineral oil) was washed 3× with anhydrous hexanes (Sigma-Aldrich, >99 %) under inert atmosphere immediately prior to use. Celite 545 (Sigma-Aldrich) was rinsed with acetone and dried in a 140 °C oven overnight prior to use. Styrene was filtered through a plug of basic alumina (oven dried at 140 °C overnight) and bubbled with dry Ar for 20 min prior to use. Triethylborane (BEt3) (Thermo Scientific, 1 mol/L) and borane dimethylsulfide complex (Alfa Aesar) were diluted with toluene to the concentrations indicated below prior to use. Concentration of active initiating species was estimated by performing several test polymerizations and analyzing the molar mass of the resulting materials. Tetrachloroethane-d4 (Cambridge, 99.5 %), deuterium oxide (Cambridge, 99.9 %), trimethylamine N-oxide dihydrate (TMANO) (Sigma Aldrich), terephthaloyl chloride (Acros, >99 %), benzyltributylammonium chloride (Sigma, >98 %), 9-Borabicyclo[3.3.1]nonane (9-BBN) (0.5 mol/L solution in THF, Thermo Scientific) and anhydrous pyridine (Sigma-Aldrich, 99.8 %) were used as received.

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy.

Spectra were collected on a 600 MHz Bruker spectrometer. Chemical shifts were referenced to the residual solvent signal of tetrachloroethane-d2 (6.0 ppm) or CDCl3 (7.26 ppm), as indicated in the spectra captions. For polyethylene samples, at least 64 scans were performed, and a relaxation delay of 5 s was used. The measurement temperatures were 90 °C for polymeric samples and 25 °C for other samples, unless otherwise stated in the spectrum caption.

Size exclusion chromatography (SEC).

Molar mass measurements were performed on a Tosoh EcoSEC HT instrument (HLC-8321GPC/HT) equipped with two Tosoh TSKgel GMHHR-H (S) HT2 columns (13 μm mixed bed, 7.8 mm ID × 30 cm) and one Tosoh TSKgel GMHHR-H (20) HT2 column (20 μm, 7.8 mm ID × 30 cm). Exclusion limit ≈ 4 × 108 g/mol. 1,2,4-trichlorobenzene or 1,2-dichlorobenzene with 300 ppm Irganox 1010 was used as the mobile phase at either 135 °C or 160 °C (specific conditions for each sample included in SI). Molar mass was calculated using a polystyrene standard curve and corrected using the appropriate Mark-Houwink-Sakurada parameters for polystyrene and polyethylene at the measurement temperature. The measured molar mass was then further corrected to account for the molar mass difference between 1H and 2H using Mn(corrected) = Mn(measured)*[(16 g/mol)*xD + (14 g/mol)*(1 – xD)] / (14 g/mol), where xD is the mole fraction of deuterated repeat units.

Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy.

Spectra were collected using a Nicolet iS50 FT-IR instrument. Attenuated total reflectance (ATR) measurements were performed at 4 cm−1 resolution using a diamond ATR plate. At least 128 scans were collected. The percent deuteration of each sample was calculated from the integrals of the CH stretching peak and the CD stretching peak. The CH stretching peak integral was multiplied by 0.63 to account for differences in absorbance between CH and CD bonds.44 Transmission measurements were performed in a temperature-controlled sample cell with CaF2 windows (32 mm diameter × 3 mm thickness) at 1 cm−1 resolution and 32 scans. The sample compartment was thoroughly purged with dry CO2-free air. Background spectra were collected at 46 °C. To load a sample, one CaF2 window was loaded into the temperature-controlled cell, then 3 mg to 4 mg of powdered polyethylene sample was placed in the center of the window and melted at 150 °C. Then, the second CaF2 window was placed on top of the sample and pressed down until the sample was approximately 2 cm in diameter (estimated sample thickness ≈10 μm). The sample was held at 150 °C for several minutes before ambiently cooling to 46 °C (initial cooling rate ≈5 °C/min). Samples were then heated to the indicated temperature and equilibrated for 10 minutes prior to measurement. Error bars represent the standard deviation among measurements for three separately loaded/melt-crystallized portions of each polyethylene batch. Baseline correction was performed using an asymmetrically reweighted penalized least squares (ArPLS) algorithm.45

Raman spectroscopy.

Raman spectra were collected using a DXR Raman instrument from Thermo Fisher Scientific using a 780 nm laser set to a power of 24 mW. Prior to measurement, about 50 mg of powdered polyethylene was pressed into an 8 mm diameter pellet. The samples were then melted at 150 °C in a vacuum oven and allowed to cool to room temperature ambiently (initial cooling rate ~0.5 °C/min). Samples were measured on glass substrates using a 20× objective (LMPLFLN, Olympus), then the Raman spectrum of the glass substrate was subtracted from the result. The exposure time per spectrum was 10 s, and a total of 200 spectra were averaged together for each copolymer at each temperature.

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC).

Measurements were performed using a TA Instruments Discovery DSC 2500. Powdered PE samples (2 mg to 5 mg) were loaded and crimped into aluminum sample pans. Samples were heated at 10 °C/min to 160 °C, held isothermal for 5 min, cooled to −70 °C at 5 °C/min, held isothermal for 5 min, then heated again to 160 °C at 10 °C/min. Peak melting temperature ™ and degree of crystallinity were calculated from the second heating cycle. Finite crystal size was accounted for in crystallinity calculations as previously described.46

Trimethylsulfoxonium chloride synthesis.

Protiated trimethylsulfoxonium chloride was prepared as previously described31 (detailed experimental procedures are included in the SI). Deuterated trimethylsulfoxonium chloride was prepared by dissolving 2.6 g protiated trimethylsulfoxonium chloride in 12 g D2O and stirring 16 h at 70 °C. D2O was then removed by rotary evaporation. The resulting powder was redissolved in 12 mL of fresh D2O, and the process was repeated a total of 4 times. While added base has been reported to catalyze the H/D exchange,31 we found exchange still occurred in the absence of base. The extent of deuteration (determined from integrals of CH3 and CD3 stretching peaks in ATR-FTIR) was estimated to be >97 %. The resulting deuterated trimethylsulfoxonium chloride was dried in vacuo at 60 °C overnight prior to use.

Dimethylsulfoxonium methylide synthesis.

Protiated and deuterated dimethylsulfoxonium methylide (referred to as ylide throughout) were prepared from protiated and deuterated trimethylsulfoxonium chloride, respectively, as previously described31 (detailed experimental procedures are included in the SI). Ylide was stored as 0.6 mol/L to 0.8 mol/L solutions in toluene in a −20 °C freezer under inert atmosphere.

Representative polymerization procedure (alkyl-6, Entry 1).

In an N2-filled glovebox, a 50 mL round bottom flask with a 24/40 rubber septum was loaded with 10 mL toluene and heated to 80 °C. Next, 1.3 mL 0.71 mol/L ylide-d8 solution in toluene (0.92 mmol) was added via syringe, followed by rapid addition of 0.24 mL of 0.029 mol/L BEt3 in toluene (7.0 μmol). After 30 min, complete monomer consumption was verified by adding a ≈0.1 mL aliquot to ≈1 mL water with phenolphthalein and confirming the mixture was colorless. Next, 12.9 mL 0.64 mol/L ylide in toluene (8.3 mmol) was added dropwise by syringe, and the mixture was stirred for 30 min, during which time the mixture became turbid. Complete monomer consumption was confirmed as described above. The flask was then removed from the glovebox, excess TMANO (100 mg) was added under flow of Ar, and the mixture was stirred for 2 h at 80 °C before precipitating in 200 mL rapidly stirring methanol. The resulting polyethylene was vacuum filtered, washed sequentially with methanol, deionized water, and acetone, and dried in vacuo at 60 °C overnight. Yield = 139 mg. For higher molar masses, shorter polymerization times (10 min / block) were observed to reduce7ispersityrsity of the molar mass distribution, likely due to reduced chain termination. Monomer concentrations below 0.4 mol/L are recommended because the polymerization is very exothermic. Polymerization times and reagent ratios for each polymerization are included in the SI.

Polyethylene with phenyl chain end (phenyl-5, Entry 2).

In an N2-filled glovebox, 0.135 g styrene (1.2 mmol) and 9.6 mL of 0.024 mol/L Bh3-SMe2 (0.23 mmol) were combined and stirred at room temperature for 3 h to generate B(CH2CH2C6H5)3. In a separate 50 mL round bottom flask, 10 mL of toluene was heated to 80 °C. Using a syringe, 1.17 mL ylide-d8 (0.66 mol/L in toluene, 0.77 mmol) was added to the flask, followed by 0.28 mL of the B(CH2CH2C6H5)3 solution (6.7 μmol). After 10 min, complete monomer consumption was verified as described above, and 11.0 mL of ylide (0.69 mol/L in toluene, 7.6 mmol) was added dropwise. The mixture was stirred for 10 additional minutes before quenching and purifying as described above. Yield = 123 mg.

Polyethylene with methyl terephthalate chain end (MT-5, Entry 4).

To a 100 mL Schlenk flask, 50 mg (9.3 μmol) of hydroxyl-5 (Entry S1) was added and dissolved in 1 mL toluene at 100 °C. The toluene was evaporated under Ar flow to remove any trace moisture or solvent from the polyethylene. Once the toluene was evaporated, 3 mL of toluene and 0.1 mL pyridine were added, the flask was stoppered with a rubber septum, and the polyethylene was re-dissolved at 100 °C. Once dissolved, 20 mg terephthaloyl chloride was quickly added to the flask under Ar flow, and the mixture was stirred for 2 h. Next, 0.1 mL methanol was slowly added to quench the reaction. After several minutes, the mixture was precipitated in 50 mL methanol, vacuum filtered, and dried in vacuo at 60 °C overnight. Yield = 48 mg.

Polyethylene with cyclooctane unit in chain center (mid-ring-6, Entry 6)

In a N2-filled glovebox, 7.9 mL of 0.5 mol/L 9-BBN in THF and 0.24 mL of cyclooctadiene were combined in a 100 mL Schlenk flask at room temperature. The mixture was magnetically stirred for 3 h, then cooled to 0 °C, and THF was evaporated in vacuo, yielding a viscous colorless liquid. The resulting hydroboration product was diluted to 0.05 mol/L in dry degassed toluene and stored under N2 at −20 °C prior to use as a polymerization initiator. 1H and 13C NMR spectra of the initiator are included in the Supporting Information. To synthesize mid-ring-9k, 0.9 mL of ylide-d8 (0.64 mol/L) was diluted with 10 mL toluene in a 50 mL round bottom flask and heated to 40 °C. Next, 0.085 mL of the initiator solution was quickly added to the flask, and the mixture was stirred for 15 minutes, at which point a small aliquot was removed to confirm complete monomer consumption. Next, 7.9 mL of protiated ylide (0.66 mol/L) was added dropwise. The mixture was stirred for 1 h at 40 °C, and an additional 1 h at 50 °C. The resulting polymer was quenched and purified as described above. Yield = 73 mg.

Results and Discussion

Employing the synthetic strategy outlined in Scheme 1, a series of polyethylenes with deuterated segments adjacent to structural features were synthesized. The length and location of the deuterated segments were controlled by adjusting the molar equivalents of deuterated monomer and the sequence of monomer addition steps, respectively. In this work, the target –(CD2)– segment lengths were chosen to be short enough that they were close to or lower than the entanglement molar mass, and shorter than a typical lamellar thickness in polyethylene, but long enough that acceptable signal/noise ratios could be achieved in vibrational spectroscopy measurements (e.g., 1400 g/mol for alkyl-48k and mid-chain-53k, and 700 g/mol, or 45 –(CD2)– repeat units, for all other samples). The fraction of deuterated repeat units in each sample was verified using ATR-FTIR and reported in Table 1. During the polymerization, it was important to confirm complete monomer consumption prior to polymerization of the subsequent block to ensure that –(CH2)– and –(CD2)– units were arranged in a blocky architecture rather than a gradient architecture and that deuterated and protiated ylide did not undergo H/D exchange with each other, leading to –(CDH)– units in the resulting polymer. By comparison of the ATR-FTIR spectra (included in the Supporting Information) to those of blocky and statistical PE/dPE copolymers reported by Farrell, et al.,32 we confirmed that the samples have a blocky architecture rather than a gradient architecture, as stretching modes for –(CDH)– units appear at different wavenumbers than those for –(CD2)– or –(CH2)– units. We also note that –(CD2)– units in long sequences can be distinguished from those flanked by –(CH2)– units by observation of the –(CD2)– rocking modes.47 While analysis of the FTIR spectra does not rule out the possibility of mixtures of PE and dPE homopolymers, such structures are not expected due to the livingness of polyhomologation polymerization31,32 and the absence of bimodality in the SEC traces (included in the Supporting Information), though we note some SEC traces showed minor shouldering.

Table 1.

Sample characterization

| entry | namea | Mn (kg/mol)b |

DPnc | Ðb | xDd (mol %) |

Tm (°C)e |

Tf (°C)e |

xc (%)e |

ff |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | alkyl-6k | 6.1 | 420 | 1.19 | 14 | 129 | 131 | 86 | 2.1 |

| 2 | phenyl-6k | 5.5 | 390 | 1.12 | 8 | 128 | 130 | 80 | 2.0 |

| 3 | hydroxyl-5k | 5.3 | 370 | 1.28 | 10 | 129 | 131 | 84 | 1.9 |

| 4 | MT-5k | 5.2 | 360 | 1.15 | 11 | 127 | 129 | 80 | 1.9 |

| 5 | mid-chain-6k | 5.7 | 430 | 1.13 | 12 | 129 | 130 | 84 | 2.1 |

| 6 | mid-ring-10k | 9.5 | 670 | 2.43 | 7 | 129 | 134 | 60 | 10 |

| 7 | alkyl-3k | 3.3 | 220 | 1.08 | 24 | 127 | 128 | 90 | 0.9 |

| 8 | alkyl-5k | 4.6 | 310 | 1.16 | 8 | 127 | 131 | 82 | 1.6 |

| 9 | alkyl-9k | 8.5 | 800 | 1.16 | 5 | 131 | 133 | 82 | 4.2 |

| 10 | alkyl-14k | 13.8 | 980 | 1.23 | 4 | 132 | 134 | 81 | 4.8 |

| 11 | alkyl-25k | 24.6 | 1750 | 1.61 | 2 | 133 | 136 | 76 | 12 |

| 12 | alkyl-48k | 48.0 | 3410 | 1.37 | 3 | 133 | 137 | 63 | 24 |

| 13 | mid-chain-3k | 3.4 | 240 | 1.19 | 20 | 128 | 129 | 88 | 1.1 |

| 14 | mid-chain-15k | 14.8 | 1040 | 1.43 | 3 | 132 | 134 | 79 | 6.4 |

| 15 | mid-chain-27k | 26.6 | 1890 | 1.34 | 3 | 133 | 135 | 76 | 11 |

| 16 | mid-chain-54k | 53.6 | 3810 | 1.32 | 2 | 133 | 137 | 62 | 24 |

Naming convention follows labels in Scheme 1. The number following the hyphen represents the molar mass in kg/mol.

Determined from SEC.

Number average carbons per chain.

Deuterated repeat units (xD) determined from ATR-FTIR spectra.

Peak melting temperature (Tm), melting endset temperature (Tf), and percent crystallinity (xc) determined from DSC 2nd heating cycle.

Mass average number of folds per chain in the crystalline lamellar structure

Chain ends are both the simplest and most ubiquitous type of chain defect, prompting us to explore deuterium labeling in polyethylene segments adjacent to chain ends in this work. The α-chain end was tunable by choice of organoborane (see alkyl-6k and phenyl-5k), and the ω-chain end could be functionalized via oxidative termination (hydroxyl-6k) and subsequent post-polymerization modification (MT-6k). For all low molar mass samples (<10 kg/mol) dispersity (Ð) was <1.3. Generally, Ð was higher for high molar mass samples (Table 1). Previous work from Shea, et al., has attributed increased dispersity at high molar mass to delayed initiation from oxidized impurities in the highly air-sensitive organoborane initiator. We note that premature termination of a small fraction of growing polymer chains is also possible, particularly in the multiblock materials presented here in which disadvantageous side reactions may occur in the time between monomer addition steps. Indeed, minor low molar mass shoulders can be observed in the SEC traces for some mid-chain-labeled samples (see Supporting Information), consistent with chain termination during or prior to monomer addition steps. Importantly, premature termination and delayed initiation would lead to a fraction of chains having deuterated segments in a different part of the chain than intended. However, the minor shouldering seen in some SEC traces suggest that the concentration of misdeuterated material in each sample is small.

A bulky mid-chain defect, a cyclooctane ring in this case, was achieved using an initiator derived from the hydroboration of 1,5-cyclooctadiene with 9-BBN (Scheme S1). However, the resulting polymer had high dispersity, and Mn was 1.6 times the target value. This observation is consistent with slow initiation from the bulky alkyl borane and fast propagation once a few monomer insertions gave rise to a less sterically encumbered site for monomer complexation. Boraadamantane-initiated polymerizations described by Shea, et al., similarly exhibited starkly different propagation rates depending on the sequence in which the first few monomer insertions occurred.36,37 An analogous initiator (B-thexyl-9-BBN) was proposed by Hadjichrisitidis, et al., but the reported 1H, 13C, and 11B NMR spectra of the initiator suggested that B-thexyl-9-BBN was a minor component among other organoboranes.41,48

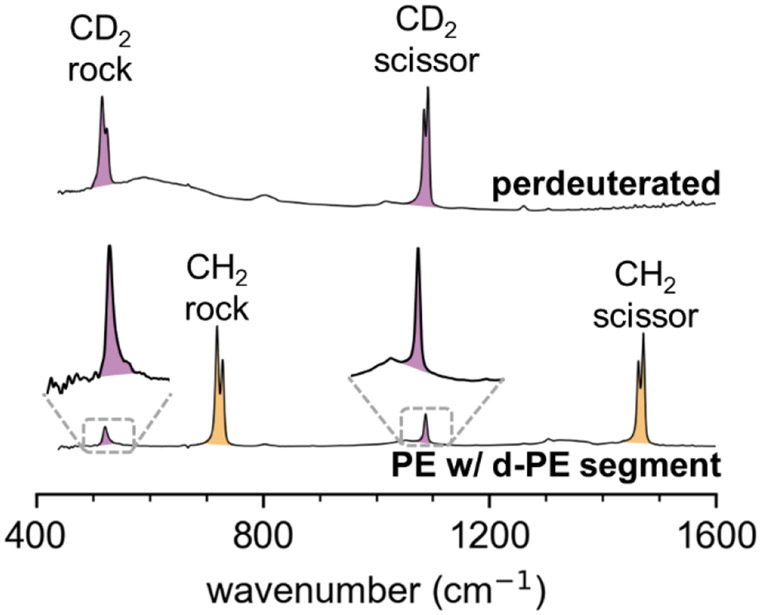

Vibrational spectroscopy techniques are particularly well-suited to characterization of deuterium-labeled polyethylenes, and the instrumentation for performing vibrational spectroscopy is generally more accessible to the experimentalist than techniques such as neutron scattering. Because a 2H atom is twice the atomic mass of a 1H atom, the wavenumbers of C-D vibrational modes are lower than those for C-H vibrational modes by a factor of √2, enabling selective observation of d-PE vibrational modes in the presence of protiated PE. Accordingly, vibrational spectroscopy has been employed extensively to study conformation and crystallization in blends of deuterated and protiated polyethylenes. Most typically, CD2 and CH2 bending modes are analyzed to obtain information on crystallinity and conformational order.19,49-51 Among the interesting features of these bending modes is the crystal field splitting effect that occurs when a chain segment shares a unit cell with an identical chain segment, enabling in-phase and out-of-phase bending that manifest as two separate peaks in FTIR and Raman spectra. In Figure 1, it is readily apparent that the CD2 rocking and bending modes in perdeuterated PE display this phenomenon. However, in PE with short deuterated segments, the CH2 bending modes exhibit crystal field splitting while the CD2 bending modes do not. It can be concluded that the deuterated segments, which comprise only 20 % of the chain in Figure 1, are relatively unlikely to share a unit cell with other deuterated segments because they are diluted by protiated segments. Importantly, it indicates that deuterated segments did not phase segregate from the protiated segments despite slightly different melting temperatures and crystallization rates reported for PE and dPE.52-56 While the CD2 bending mode peaks are relatively weak, the signal/noise ratio is sufficiently high to discern the peak shape, and the wavenumber resolution was the same for partially- and fully-deuterated samples shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

ATR-FTIR absorbance spectra of CD2 and CH2 bending modes in perdeuterated PE (Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, top) and mid-chain-3k (entry 13, bottom). Crystal field splitting was absent in CD2 bending modes (purple) for PE with deuterated segments, indicating phase segregation of deuterated segments did not occur.

Given the absence of crystal field splitting of the deuterated segments and the relatively low intensity of CD2 bending modes, we opted to use the C-D stretching mode vibrations for analysis of chain conformation. Raman and FTIR spectra both contain conformational order indicators in the C-D stretching region, shown on the annotated spectra in Figures 2 and 3. While conformational order is certainly correlated with crystallinity, we note that there can be instances of chains or chain segments with high conformational order that are not crystalline (e.g. extended segments of several consecutive trans bonds in dangling cilia and tie-chains).57 For Raman spectroscopy, the ratio of peak intensities at 2196 cm−1 and 2172 cm−1 (I2176/I2194) has been correlated with conformational order.58 In the Raman spectra shown in Figures S37-S41, an increase in I2176/I2194 upon heating is readily observed. We note that the peak that Liao, et al., observed at 2172 cm−1 was observed between 2176 cm−1 and 2182 cm−1 for the samples presented here. For FTIR spectroscopy, the disappearance of the C-D symmetric stretching peak at 2088 cm−1 and the emergence of a blue shifted peak at 2097 cm−1 is observed during melting, with both vibrational modes appearing to coexist at temperatures near the melting point (Figure 2). The blue shift in C-D stretching peaks has previously been used to selectively observe melting in phospholipid membrane components,59,60 and analogous behavior has been reported for C-H stretching modes.49 Here, the normalized absorbance at 2088 cm−1 (A2088/A2195) was used as a measure of conformational order, with higher values corresponding to higher conformational order in the deuterated segment. While it is difficult to extract direct structural information such as gauche/trans ratios from A2088/A2195, it can be applied to perform comparisons of conformational order between samples. Further, A2088/A2195 was less sensitive to isotopic impurities and subtle day-to-day differences in baseline curvature than peak deconvolution or peak width analyses, and the results were found to be highly reproduceable in repeat experiments.

Figure 2.

Representative transmission FTIR absorbance spectra of d-PE segment melting (mid-chain-6k, entry 5). Stretching modes of trace –CDH– isotopic impurities appear in the asterisked region.

Figure 3.

Conformational order indicators for (a) Raman and (b) transmission-FTIR spectra. Low ratios of Raman scattering intensity at 2176 cm−1 and 2194 cm−1 (I2176/I2194) and high ratios of FTIR absorbance at 2088 cm−1 and 2195 cm−1 (A2088/A2195) correlate with higher conformational order of the deuterated chain segment.

From comparison of A2088/A2195 for alkyl-6k and mid-chain-6k (Figure 3b), the deuterated segment adjacent to the methyl end group in alkyl-6k was observed to be more conformationally ordered than segments in the middle of the chain, in good qualitative agreement with previously reported solid state NMR experiments.30,61,62 In other words, segments in the middle of the chain were, on average, more likely to reside in the amorphous domain than segments adjacent to chain ends. In contrast to what often is schematized in textbook cartoons of lamellar semicrystalline structures, chain ends have been proposed to reside primarily at the surface of the lamellar structure rather than extending into the amorphous domain.61 Otherwise, a sterically unrealistic environment with anomalously high density would result at the interface between crystalline and amorphous domains. The problem of interfacial density anomalies was identified decades ago and traditionally accounted for with models that include tight chain folding at the lamellar surface,63 but measurements and calculations from Schmidt-Rohr, et al., showed that tight chain folding was insufficient to alleviate interfacial crowding.61 Instead, the interfacial vacancies resulting from chain ends residing at the lamellar surface, as well as chain tilt, were required. The FTIR spectra presented here are fully consistent with segments adjacent to chain ends being, on average, more conformationally ordered than the rest of the polymer chain, which would be expected if the chain ends resided at the lamellar surface. While the Raman spectra generally had poorer signal/noise ratios in this work, the lower values of I2176/I2194 for the chain-end-labeled segment are also consistent with a higher degree of conformational order.

To provide additional insight into the location of the deuterated segments, DSC melting traces were converted into crystal size distributions using Equations S1 and S2 (see Fig. S98 to S113) as described previously64 and in the Supporting Information. The mass average degree of polymerization was divided by the mass average crystal size (in units of backbone carbons) to estimate the number of chain folds, as , where nW is the mass average number of carbons per chain, and is the crystal thickness (see Table 1). A key advantage of estimating the crystal size distributions by DSC is that it measures the stem length along the direction of the stem. In contrast, SAXS measures interface-to-interface distance, which will underestimate the stem length due to chain tilt.61 The Huang-Brown method was used to estimate the fraction of chains bridging between crystals (fraction of tie molecules) using the molar mass distributions, mass averaged crystal size, and amorphous domain thickness from xc.65,66 The Huang-Brown method uses a random walk model to determine the probability of tie molecule formation (P) by determining which chains are sufficiently long to span the distance (L) from one lamellar crystal (thickness , where nm for PE) through the interlamellar amorphous region (thickness ) and through the next lamellar crystal, hence . The probability for a given chain length is given by66-68

| (1) |

where , with the degree of polymerization and the chain expansion factor ( for PE). was computed as described above and was determined via68

| (2) |

with and the crystal and amorphous density ( g/cm3 and g/cm3 for polyethylene).68 Eq. 1 was then integrated over the individual molar mass distributions for each sample

| (3) |

to yield the average tie molecular fraction . In all cases, was less than 0.05 %; the largest, Entry 12, was 0.02 % and most were estimated to be <0.002 %. This indicates that higher conformational order in a deuterated segment would be incredibly unlikely to be attributable to a tie molecule and is more likely attributable to higher likelihood of being incorporated into a given crystallite.

The synthetic approach employed in this work enabled systematic evaluation of the effect of molar mass on the conformational order of chain end segments and mid-chain segments (Figure 4). The molar mass dependence of mid-chain crystallinity largely followed expectation: As molar mass increased, the deuterated segment showed lower conformational order, likely due to decreased chain mobility during crystallization for longer, more entangled chains. In contrast, the alkyl chain end showed non-monotonic molar mass dependence of conformational order. Maximum chain end crystallinity was observed at 5 kg/mol to 6 kg/mol, after which A2088/A2195 sharply declined and plateaued at higher molar masses. At higher molar masses, we speculate that reduced chain mobility prevented chain ends from migrating to the lamella interface to the extent that they did for the 5–6 kg/mol samples. For the lowest molar mass sample, alkyl-3k, the concentration of chain ends is high, meaning a lower proportion of total chain ends would be required to reside at the lamella surface to alleviate steric crowding. Consequently, a relatively high proportion of chain ends may be accommodated in the amorphous domain compared to other samples. We also note that on average, alkyl-3k and mid-chain-3k are estimated to be once-folded (Table 1), meaning that the deuterated segment in mid-chain-3k should reside near the fold. The fact that the deuterated segment in mid-chain-3k has relatively high conformational order despite residing at the fold is consistent with a relatively tight chain fold, which would require the chain ends to extend into the amorphous domain to accommodate non-uniform molar mass chains into the crystal structure. It is also possible that a fraction of the deuterated segments lie in the center of the crystal due to its higher dispersity and the presence of two distinctive populations of crystal sizes (see Fig. S110) that could be attributed to once-folded and extended chain crystals as has been seen previously for the similar molar mass paraffin n-C294H590.69

Figure 4.

Ratio of transmission-FTIR absorbances at 2088 cm−1 and 2195 cm−1 (A2088/A2195) for (a) alkyl-end-labeled samples (entries 1 and 7–12) and (b) mid-chain-labeled samples (entries 5 and 13-16) at several molar masses. (c) Same data at 46 °C replotted vs Mn. Higher values of (A2088/A2195) at a given temperature correlate with higher conformational order of the deuterated chain segment. Error bars represent standard deviation among three experiments, each using separate portions of the indicated sample.

We next sought to leverage the versatility in end group functionality afforded by the polyhomologation approach to evaluate the effect of chain end functionality on local conformational order. In general, deuterated segments adjacent to bulky and polar chain ends showed lower conformational order than those adjacent to alkyl chain ends (Figure 5) and similar conformational order to an unfunctionalized deuterated mid-segment. Given the large difference observed between alkyl-6k and alkyl-9k, despite their nominal structural similarity, we sought to measure the effect of batch-to-batch variability for hydroxyl-5k and MT-6k. We found that of four identically-prepared hydroxyl-end-labeled samples (Entries 3, S1-S3), three had almost identical values of A2088/A2195, but Entry S3 showed significantly higher conformational order, similar to that exhibited by alkyl-6k, despite all four batches having similar molar mass, dispersity, and isotopic purity Figure S4). Interestingly, a methyl-terephthalate-capped sample (Entry S4) derived from Entry S3 also showed similarly high conformational order. This result, in combination with the stark differences observed between alkyl-6k and alkyl-9k, demonstrate that subtle differences in molar mass distribution may give rise to significant differences in crystallization behavior, as has been theoretically predicted.70

Figure 5.

Ratio of transmission-FTIR intensities at 2088 cm−1 and 2195 cm−1 (A2088/A2195) near different structural features (entries 1–6). Inset shows side-by-side results at 46 °C for clarity. Higher values of (A2088/A2195) at a given temperature correlate with higher conformational order of the deuterated chain segment. Error bars represent standard deviation among three experiments, each using separate portions of the indicated sample.

Surprisingly, the deuterated segment in mid-ring-10k showed similar conformational order to mid-chain-6k despite substantially lower bulk crystallinity measured by DSC (Table 1). Because it is unlikely that the cyclooctane ring itself was incorporated into the lamellar structure, the data suggest that the cyclooctane ring, like the chain ends, had a propensity to reside at the interface between the lamellar and amorphous domains. We note if slow initiation was indeed the cause of mid-ring-10k’s high dispersity, then unequal chain lengths on either side of the cyclooctane ring would result. Consequently, deuterated segments may reside closer to the chain end than chain center, and the lengths of the deuterated segments, like those of the whole polymer chain, are likely to be disperse. The melting endset point () of mid-ring-10k was slightly higher than the other samples, which was attributed to its larger fraction of higher molar mass chains, which melt at higher temperatures than low molar mass chains.71

Conclusion

Despite the utility of isotopic labelling for understanding microscopic details of polymer crystallization, only a handful of polyethylenes with selectively deuterated segments have been previously reported. In this work, we employed polyhomologation to synthesize a series of polyethylenes with deuterated segments of tunable length and position near a range of structural features such as functional chain ends and mid-chain defects. Using vibrational spectroscopy, conformational order of the deuterated segments could be assessed independently of the protiated segments, offering insight into local crystallization behavior. At 5 kg/mol to 6 kg/mol, deuterated segments adjacent to an unfunctionalized alkyl chain end showed generally higher conformational order than bulkier and more polar end groups and mid-chain segments. Additionally, we observed that alkyl chain end conformational order displayed different molar mass dependence than that of the bulk or chain center. With the ability to selectively measure conformation of specific chains or chain segments, new insight into local crystallization behavior is accessible. By understanding which parts of a polymer chain are incorporated into the crystalline and amorphous domains, one can more thoughtfully approach the design of materials to achieve desired mechanical performance, aging behavior, barrier properties, blend behavior, and other properties of interest.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

A.A.B acknowledges support from the NRC Postdoctoral Associateship Program. This work was supported by the NIST Circular Economy Program.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Detailed experimental procedures, analysis of batch-to-batch variability, FTIR spectra, Raman spectra, SEC traces, NMR spectra, DSC traces, calculated crystal size distributions.

The primary data underlying this study are openly available in the NIST Public Data Repository at [https://doi.org/10.18434/mds2-3035].

References

- (1).EMF. The New Plastics Economy: Rethinking the Future of Plastics & Catalysing Action. Ellen MacArthur Found. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- (2).Baur M; Mecking S Polyethylenes with Combined In-Chain and Side-Chain Functional Groups from Catalytic Terpolymerization of Carbon Monoxide and Acrylate. ACS Macro Lett. 2022, 11 (10), 1207–1211. 10.1021/acsmacrolett.2c00459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Zhang Y; Wang C; Mecking S; Jian Z Ultrahigh Branching of Main-Chain-Functionalized Polyethylenes by Inverted Insertion Selectivity. Angew. Chemie 2020, 132 (34), 14402–14408. 10.1002/ange.202004763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Chethalen RJ; Fastow EJ; Coughlin EB; Winey KI Thiol–Ene Click Chemistry Incorporates Hydroxyl Functionality on Polycyclooctene to Tune Properties. ACS Macro Lett. 2023, 12 (1), 107–112. 10.1021/acsmacrolett.2c00670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Burkey AA; Fischbach DM; Wentz CM; Beers KL; Sita LR Highly Versatile Strategy for the Production of Telechelic Polyolefins. ACS Macro Lett. 2022, 11 (3), 402–409. 10.1021/acsmacrolett.2c00108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Yan T; Guironnet D Synthesis of Telechelic Polyolefins. Polym. Chem 2021, 12 (36), 5126–5138. 10.1039/D1PY00819F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Park SS; Kim CS; Kim SD; Kwon SJ; Lee HM; Kim TH; Jeon JY; Lee BY Biaxial Chain Growth of Polyolefin and Polystyrene from 1,6-Hexanediylzinc Species for Triblock Copolymers. Macromolecules 2017, 50 (17), 6606–6616. 10.1021/acs.macromol.7b01365. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Pitet LM; Hillmyer MA Carboxy-Telechelic Polyolefins by ROMP Using Maleic Acid as a Chain Transfer Agent. Macromolecules 2011, 44 (7), 2378–2381. 10.1021/ma102975r. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Yan L; Hauler M; Bauer J; Mecking S; Winey KI Monodisperse and Telechelic Polyethylenes Form Extended Chain Crystals with Ionic Layers. Macromolecules 2019, 52 (13), 4949–4956. 10.1021/acs.macromol.9b00962. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Jian Z; Falivene L; Boffa G; Sánchez SO; Caporaso L; Grassi A; Mecking S Direct Synthesis of Telechelic Polyethylene by Selective Insertion Polymerization. Angew. Chemie 2016, 128 (46), 14590–14595. 10.1002/ange.201607754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Arriola DJ; Carnahan EM; Hustad PD; Kuhlman RL; Wenzel TT Catalytic Production of Olefin Block Copolymers via Chain Shuttling Polymerization. Science 2006, 312 (5774), 714–719. 10.1126/science.1125268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Eagan JM; Xu J; Di Girolamo R; Thurber CM; Macosko CW; La Pointe AM; Bates FS; Coates GW Combining Polyethylene and Polypropylene: Enhanced Performance with PE/IPP Multiblock Polymers. Science 2017, 355 (6327), 814–816. 10.1126/science.aah5744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Nomura K; Peng X; Kim H; Jin K; Kim HJ; Bratton AF; Bond CR; Broman AE; Miller KM; Ellison CJ Multiblock Copolymers for Recycling Polyethylene–Poly(Ethylene Terephthalate) Mixed Waste. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12 (8), 9726–9735. 10.1021/acsami.9b20242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Baur M; Lin F; Morgen TO; Odenwald L; Mecking S Polyethylene Materials with In-Chain Ketones from Nonalternating Catalytic Copolymerization. Science 2021, 374 (6567), 604–607. 10.1126/science.abi8183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Häußler M; Eck M; Rothauer D; Mecking S Closed-Loop Recycling of Polyethylene-like Materials. Nature 2021, 590 (May 2020). 10.1038/s41586-020-03149-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Arrington AS; Brown JR; Win MS; Winey KI; Long TE Melt Polycondensation of Carboxytelechelic Polyethylene for the Design of Degradable Segmented Copolyester Polyolefins. Polym. Chem 2022, 13 (21), 3116–3125. 10.1039/D2PY00394E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Lodge TP Celebrating 50 Years of Macromolecules. Macromolecules 2017, 50 (24), 9525–9527. 10.1021/acs.macromol.7b02507. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Li L; Jakowski J; Do C; Hong K Deuteration and Polymers: Rich History with Great Potential. Macromolecules 2021, 54 (8), 3555–3584. 10.1021/acs.macromol.0c02284. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Tashiro K; Stein RS; Hsu SL Cocrystallization and Phase Segregation of Polyethylene Blends. 1. Thermal and Vibrational Spectroscopic Study by Utilizing the Deuteration Technique. Macromolecules 1992, 25 (6), 1801–1808. 10.1021/ma00032a029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Tashiro K; Satkowski MM; Stein RS; Li Y; Chu B; Hsu SL Cocrystallization and Phase Segregation of Polyethylene Blends. 2. Synchrotron-Sourced x-Ray Scattering and Small-Angle Light Scattering Study of the Blends between the D and H Species. Macromolecules 1992, 25 (6), 1809–1815. 10.1021/ma00032a030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Tashiro K; Izuchi M; Kobayashi M; Stein RS Cocrystallization and Phase Segregation of Polyethylene Blends between the D and H Species.4.The Crystallization Behavior As Viewed from the Infrared Spectral Changes. Macromolecules 1994, 27 (5), 1228–1233. 10.1021/ma00083a023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Tashiro K; Izuchi M; Kaneuchi F; Jin C; Kobayashi M; Stein RS Cocrystallization and Phase Segregation of Polyethylene Blends between the D and H Species.6.Time-Resolved FTIR Measurements for Studying the Crystallization Kinetics of the Blends under Isothermal Conditions. Macromolecules 1994, 27 (5), 1240–1244. 10.1021/ma00083a025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Tashiro K; Izuchi M; Kobayashi M; Stein RS Cocrystallization and Phase Segregation of Polyethylene Blends between the D and H Species. 5. Structural Studies of the Blends As Viewed from Different Levels of Unit Cell to Spherulite. Macromolecules 1994, 27 (5), 1234–1239. 10.1021/ma00083a024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Tashiro K; Imanishi K; Izumi Y; Kobayashi M; Kobayashi K; Satoh M; Stein RS Cocrystallization and Phase Segregation of Polyethylene Blends between the D and H Species. 7. Time-Resolved Synchrotron-Source Small-Angle X-Ray Scattering Measurements for Studying the Isothermal Crystallization Kinetics: Comparison with the FTIR Data. Macromolecules 1995, 28 (25), 8477–8483. 10.1021/ma00129a003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Crist B; Nicholson JC Small-Angle Neutron-Scattering Studies of Partially Labelled Crystalline Polyethylene. Polymer 1994, 35 (9), 1846–1854. 10.1016/0032-3861(94)90973-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Coutry S; Spells SJ Molecular Changes on Drawing Isotopic Blends of Polyethylene and Ethylene Copolymers: 1. Static and Time-Resolved sans Studies. Polymer 2003, 44 (6), 1949–1956. 10.1016/S0032-3861(03)00040-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Alamo RG; Londono JD; Mandelkern L; Stehling FC; Wignall GD Phase Behavior of Blends of Linear and Branched Polyethylenes in the Molten and Solid States by Small-Angle Neutron Scattering. Macromolecules 1994, 27 (2), 411–417. 10.1021/ma00080a014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Qiu J; Chen X; Le AN; López-Barrón CR; Rohde BJ; White RP; Lipson JEG; Krishnamoorti R; Robertson ML Thermodynamic Interactions in Polydiene/Polyolefin Blends Containing Diverse Polydiene and Polyolefin Units. Macromolecules 2023, 56 (6), 2286–2297. 10.1021/acs.macromol.2c01866. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Brooke GM; Farren C; Harden A; Whiting MC Syntheses of Very Long Chain Alkanes Terminating in Polydeuterium- Labelled End-Groups and Some Very Large Single-Branched Alkanes Including Y-Shaped Structures. Polymer 2001, 42, 2777–2784. 10.1016/S0032-3861. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Wutz C; Tanner MJ; Brookhart M; Samulski ET Where Are the Chain Ends in Semicrystalline Polyethylene? Macromolecules 2017, 50 (22), 9066–9070. 10.1021/acs.macromol.7b01949. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Shea KJ; Walker JW; Zhu H; Paz M; Greaves J Polyhomologation. A Living Polymethylene Synthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1997, 119 (38), 9049–9050. 10.1021/ja972009f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Farrell WS; Orski SV; Kotula AP; Baugh III DW; Snyder CR; Beers KL Precision, Tunable Deuterated Polyethylene via Polyhomologation. Macromolecules 2019, 52 (15), 5741–5749. 10.1021/acs.macromol.9b00500. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Zeng XB; Ungar G; Spells SJ; Brooke GM; Farren C; Harden A Crystal-Amorphous Polymer Interface Studied by Neutron and X-Ray Scattering on Labeled Binary Ultralong Alkanes. Phys. Rev. Lett 2003, 90 (15), 155508. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.90.155508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Zapsas G; Ntetsikas K; Kim J; Bilalis P; Gnanou Y; Hadjichristidis N Boron “Stitching” Reaction: A Powerful Tool for the Synthesis of Polyethylene-Based Star Architectures. Polym. Chem 2018, 9 (9), 1061–1065. 10.1039/C8PY00110C. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Ntetsikas K; Zapsas G; Bilalis P; Gnanou Y; Feng X; Thomas EL; Hadjichristidis N Complex Star Architectures of Well-Defined Polyethylene-Based Co/Terpolymers. Macromolecules 2020. 10.1021/acs.macromol.0c00668. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Wagner CE; Kim JS; Shea KJ The Polyhomologation of 1-Boraadamantane: Mapping the Migration Pathways of a Propagating Macrotricyclic Trialkylborane. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2003, 125 (40), 12179–12195. 10.1021/ja0361291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Wagner CE; Shea KJ 1-Boraadamantane Blows Its Top, Sometimes. The Mono-and Polyhomologation of 1-Boraadamantane. Org. Lett 2001, 3 (20), 3063–3066. 10.1021/ol0159726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Shea KJ; Lee SY; Busch BB A New Strategy for the Synthesis of Macrocycles. The Polyhomologation of Boracyclanes. J. Org. Chem 1998, 63 (17), 5746–5747. 10.1021/jo981174q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Shea KJ; Busch BB; Paz MM Polyhomologation: Synthesis of Novel Polymethylene Architectures by a Living Polymerization of Dimethylsulfoxonium Methylide. Angew. Chemie Int. Ed 1998, 37 (10), 1391–1393. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Zhang Z; Altaher M; Zhang H; Wang D; Hadjichristidis N Synthesis of Well-Defined Polyethylene-Based 3-Miktoarm Star Copolymers and Terpolymers. Macromolecules 2016, 49 (7), 2630–2638. 10.1021/acs.macromol.6b00291. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Alshumrani RA; Hadjichristidis N Well-Defined Triblock Copolymers of Polyethylene with Polycaprolactone or Polystyrene Using a Novel Difunctional Polyhomologation Initiator. Polym. Chem 2017, 8 (35), 5427–5432. 10.1039/c7py01079f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Xu F; Dong P; Cui K; Bu SZ; Huang J; Li GY; Jiang T; Ma Z New Synthetic Strategy Targeting Well-Defined α,ω-Telechelic Polymethylenes with Hetero Bi-/Tri-Functionalities: Via Polyhomologation of Ylides Initiated by New Organic Boranes Based on Catecholborane and Post Functionalization. RSC Adv. 2016, 6 (74), 69828–69835. 10.1039/c6ra12014h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Luo J; Zhao R; Shea KJ Synthesis of High Molecular Weight Polymethylene via C1 Polymerization. The Role of Oxygenated Impurities and Their Influence on Polydispersity. Macromolecules 2014, 47 (16), 5484–5491. 10.1021/ma501206a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Kang S; Zeng Y; Lodge TP; Bates FS; Brant P; López-Barrón CR Impact of Molecular Weight and Comonomer Content on Catalytic Hydrogen-Deuterium Exchange in Polyolefins. Polymer 2016, 102, 99–105. 10.1016/j.polymer.2016.09.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Baek S-J; Park A; Ahn Y-J; Choo J Baseline Correction Using Asymmetrically Reweighted Penalized Least Squares Smoothing. Analyst 2015, 140 (1), 250–257. 10.1039/c4an01061b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Crist B; Mirabella FM Crystal Thickness Distributions from Melting Homopolymers or Random Copolymers. J. Polym. Sci. Part B Polym. Phys 1999, 37, 3131–3140. 10.1002/(SICI)1099-0488. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Kissin YV; Brandolini AJ Ethylene Polymerization Reactions with Ziegler-Natta Catalysts. II. Ethylene Polymerization Reactions in the Presence of Deuterium. J. Polym. Sci. Part A Polym. Chem 1999, 37 (23), 4273–4280. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Alshumrani RA; Hadjichristidis N Well-Defined Non-Linear Polyethylene-Based Macromolecular Architectures. J. Polym. Sci. Part A Polym. Chem 2018, 56 (18), 2129–2136. 10.1002/pola.29173. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Snyder RG; Strauss HL; Elliger CA Carbon-Hydrogen Stretching Modes and the Structure of n-Alkyl Chains. 1. Long, Disordered Chains. J. Phys. Chem 1982, 86 (26), 5145–5150. 10.1021/j100223a018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (50).MacPhail RA; Strauss HL; Snyder RG; Elliger CA Carbon-Hydrogen Stretching Modes and the Structure of n-Alkyl Chains. 2. Long, All-Trans Chains. J. Phys. Chem 1984, 88 (3), 334–341. 10.1021/j150647a002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Jin Y; Kotula AP; Snyder CR; Hight Walker AR; Migler KB; Lee YJ Raman Identification of Multiple Melting Peaks of Polyethylene. Macromolecules 2017, 50 (16), 6174–6183. 10.1021/acs.macromol.7b01055. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Stehling FC; Ergos E; Mandelkern L Phase Separation in N-Hexatriacontane-n-Hexatriacontane-d 74 and Polyethylene-Poly(Ethylene-d4) Systems. Macromolecules 1971, 4 (6), 672–677. 10.1021/ma60024a003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Bank MI; Krimm S Mixed Crystal Infrared Study of Chain Segregation in Polyethylene. J. Polym. Sci. Part B Polym. Lett 1970, 8 (3), 143–148. 10.1002/pol.1970.110080301. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Sadler DM; Keller A Trajectory of Polyethylene Chains in Single Crystals by Low Angle Neutron Scattering. Polymer 1976, 17 (1), 37–40. 10.1016/0032-3861(76)90150-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Schelten J; Ballard DGH; Wignall GD; Longman G; Schmatz W Small-Angle Neutron Scattering Studies of Molten and Crystalline Polyethylene. Polymer 1976, 17 (9), 751–757. 10.1016/0032-3861(76)90028-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Bank MI; Krimm S Mixed Crystal Infrared Study of Chain Folding in Crystalline Polyethylene. J. Polym. Sci. Part A-2 Polym. Phys 1969, 7 (10), 1785–1809. 10.1002/pol.1969.160071014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Migler KB; Kotula AP; Hight Walker AR Trans-Rich Structures in Early Stage Crystallization of Polyethylene. Macromolecules 2015, 48 (13), 4555–4561. 10.1021/ma5025895. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Liao Z; Pemberton JE Raman Spectral Conformational Order Indicators in Perdeuterated Alkyl Chain Systems. J. Phys. Chem. A 2006, 110 (51), 13744–13753. 10.1021/jp0655219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Moore DJ; Rerek ME; Mendelsohn R FTIR Spectroscopy Studies of the Conformational Order and Phase Behavior of Ceramides. J. Phys. Chem. B 1997, 101 (44), 8933–8940. 10.1021/jp9718109. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Ziegler W; Blume A Acyl Chain Conformational Ordering of Individual Components in Liquid-Crystalline Bilayers of Mixtures of Phosphatidylcholines and Phosphatidic Acids. A Comparative FTIR and 2H NMR Study. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc 1995, 51 (10), 1763–1778. 10.1016/0584-8539(95)01520-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Fritzsching KJ; Mao K; Schmidt-Rohr K Avoidance of Density Anomalies as a Structural Principle for Semicrystalline Polymers: The Importance of Chain Ends and Chain Tilt. Macromolecules 2017, 50 (4), 1521–1540. 10.1021/acs.macromol.6b02000. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (62).VanderHart DL; Pérez E A 13C NMR Method for Determining the Partitioning of End Groups and Side Branches between the Crystalline and Noncrystalline Regions in Polyethylene. Macromolecules 1986, 19 (7), 1902–1909. 10.1021/ma00161a020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (63).Flory PJ On the Morphology of the Crystalline State in Polymers. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1962, 84 (15), 2857–2867. 10.1021/ja00874a004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (64).Baumann A; Beaucage P; Vallery R; Gidley D; Nieuwendaal R; Snyder CR; Chen F; Stafford C; Soles C Baumann A; Beaucage P; Vallery R; Gidley D; Nieuwendaal R; Snyder CR; Chen F; Stafford C; Soles C Submitted. [Google Scholar]

- (65).Gu K; Snyder CR; Onorato J; Luscombe CK; Bosse AW; Loo Y-L Assessing the Huang–Brown Description of Tie Chains for Charge Transport in Conjugated Polymers. ACS Macro Lett. 2018, 7 (11), 1333–1338. 10.1021/acsmacrolett.8b00626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (66).Huang Y-L; Brown N Dependence of Slow Crack Growth in Polyethylene on Butyl Branch Density: Morphology and Theory. J. Polym. Sci. Part B Polym. Phys 1991, 29 (1), 129–137. 10.1002/polb.1991.090290116. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (67).Patel RM; Sehanobish K; Jain P; Chum SP; Knight GW Theoretical Prediction of Tie-Chain Concentration and Its Characterization Using Postyield Response. J. Appl. Polym. Sci 1996, 60 (5), 749–758. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (68).Deslauriers PJ; Rohlfing DC Estimating Slow Crack Growth Performance of Polyethylene Resins from Primary Structures Such as Molecular Weight and Short Chain Branching. Macromol. Symp 2009, 282 (1), 136–149. 10.1002/masy.200950814. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (69).Ungar G; Stejny J; Keller A; Bidd I; Whiting MC The Crystallization of Ultralong Normal Paraffins: The Onset of Chain Folding. Science 1985, 229 (4711), 386–389. 10.1126/science.229.4711.386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (70).Hoffman JD; Miller RL Kinetic of Crystallization from the Melt and Chain Folding in Polyethylene Fractions Revisited: Theory and Experiment. Polymer 1997, 38 (13), 3151–3212. 10.1016/S0032-3861(97)00071-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (71).Fatou JG; Mandelkern L The Effect of Molecular Weight on the Melting Temperature and Fusion of Polyethylene. J. Phys. Chem 1965, 69 (2), 417–428. 10.1021/j100886a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.