Abstract

Severe influenza A virus (IAV) infections can result in hyper-inflammation, lung injury, and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS)1–5, for which there are no effective pharmacological therapies. Necroptosis is an attractive entry point for therapeutic intervention in ARDS and related inflammatory conditions because it drives pathogenic lung inflammation and lethality during severe IAV infection6–8 and can potentially be targeted by Receptor Interacting Protein Kinase 3 (RIPK3) inhibitors. Here, we show that a newly developed RIPK3 inhibitor, UH15-38, potently and selectively blocked IAV-triggered necroptosis in alveolar epithelial cells in vivo. UH15-38 ameliorated lung inflammation and prevented mortality following infection with lab-adapted and pandemic strains of IAV, without compromising antiviral adaptive immune responses or impeding viral clearance. UH15-38 displayed robust therapeutic efficacy even when administered later in the course of infection, suggesting that RIPK3 blockade may provide clinical benefit in patients with IAV-driven ARDS and other hyper-inflammatory pathologies.

Summary:

A RIPK3 kinase inhibitor blocks necroptosis in vivo and prevents deleterious lung inflammation without compromising virus clearance in severe influenza.

Main.

Seasonal influenza A virus (IAV) infections cause up to 5 million cases of severe illness, resulting in up to 650,000 deaths globally each year. Worryingly, while highly pathogenic H3, H5 and H7 strains of avian IAV are thus far limited in their spread between humans, they may require only a small number of mutations to become transmissible and achieve pandemic potential9–11. As current vaccines and antiviral strategies are either limited in their efficacy or susceptible to viral resistance and evasion, identifying new therapeutic approaches for virulent IAV-triggered pulmonary disease is imperative.

IAV-activated necrotic cell death is potentially one such entry point. As a lytic virus, IAV kills most lung cell types in which it replicates12. When such death is well-controlled, it is an effective mechanism of virus clearance, but when death is unchecked, or primarily necrotic, then lung injury and severe illness ensues, despite virus clearance12,13. Such severe pathology is observed in mouse models, where destruction of airway epithelia is a hallmark of lethal IAV infection4,14,15, and in humans, where extensive death of distal pulmonary epithelia, marked by areas of bronchoalveolar necrosis, is a classic feature of IAV-induced ARDS, and of viral and secondary bacterial pneumonia2,3,12.

Necroptosis drives influenza severity.

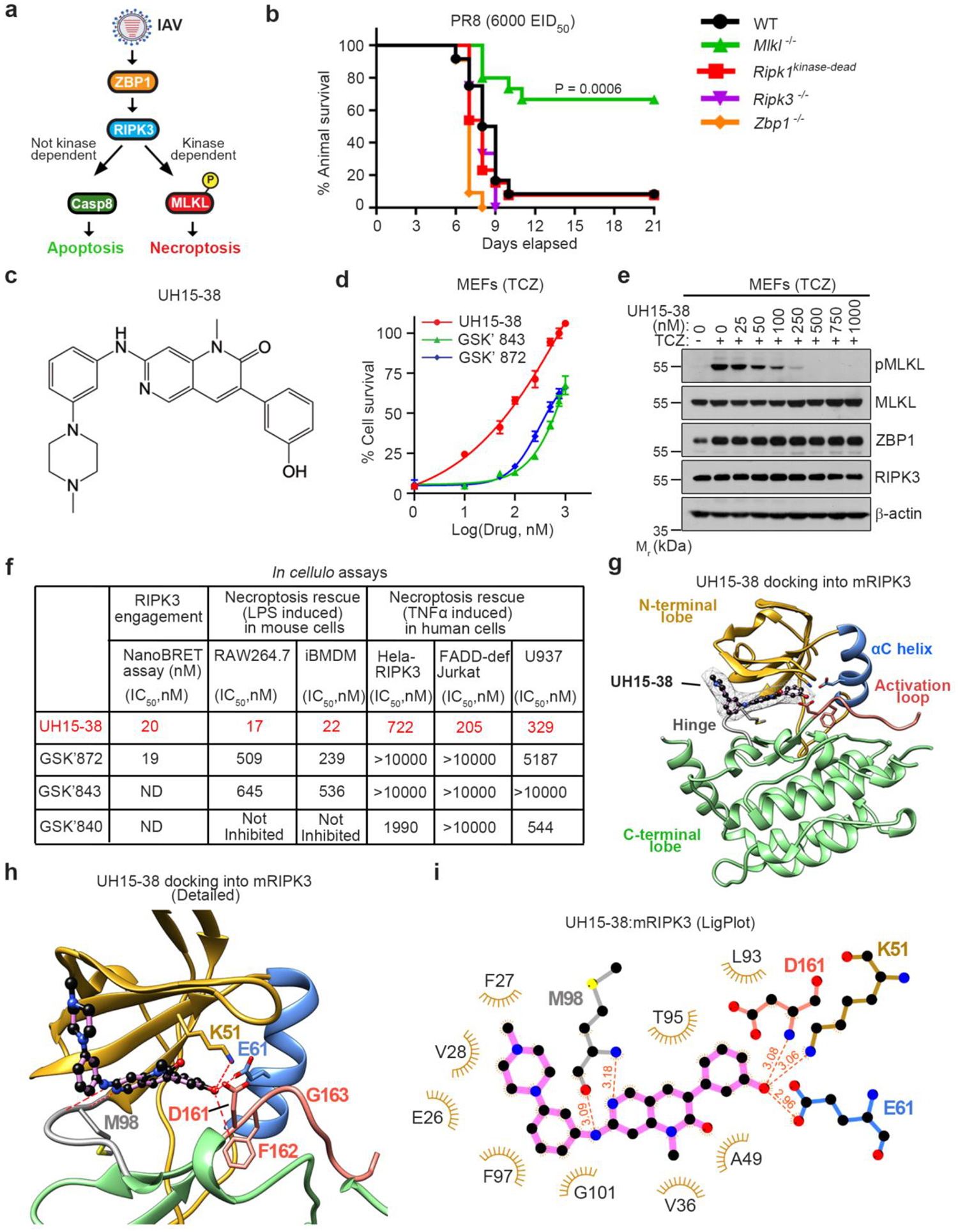

Necroptosis accounts for most IAV-activated programmed necrotic death in infected lung epithelial cells6–8,12,16,17. Necroptosis is initiated by the host sensor protein Z-form nucleic acid Binding Protein 1 (ZBP1), which detects IAV-generated Z-RNA and activates RIPK318,19. RIPK3 then phosphorylates Mixed Lineage Kinase Like protein (MLKL), which induces necroptosis6,8,12,13,18 (Fig. 1a). We have previously shown that necroptosis triggers pulmonary tissue necrosis, pathogenic neutrophil recruitment and lung inflammation during severe IAV infections, but is dispensable for either CD8+ T cell-mediated antiviral responses or for virus clearance8,13. This is because RIPK3 also activates a parallel pathway of apoptosis, which is fully capable of restricting IAV in the absence of necroptosis signaling6. These observations position necroptosis as an attractive node for therapeutic intervention, as only necroptosis, and not apoptosis, relies on RIPK3 kinase function6,20 (Fig. 1a). Inhibitors of RIPK3 kinase activity may be expected to ameliorate necrotic lung injury without affecting virus clearance, and, therefore, may represent an entirely new strategy for treatment of IAV-triggered lung inflammation and injury.

Figure 1. UH15-38 is a potent RIPK3 kinase inhibitor.

a, Influenza A viruses activate ZBP1 and trigger RIPK3-driven parallel pathways of MLKL-dependent necroptosis and caspase 8-mediated apoptosis. Only necroptosis is reliant on RIPK3 kinase activity. b, Survival analysis of mice of indicated genotypes (Wild-type [WT], n=12; Mlkl−/−, n=15; Ripk1kinase-dead, n=13; Ripk3−/−, n=12; Zbp1−/−, n=11) following intranasal challenge with IAV H1N1 strain PR8 (6000 Egg Infectious Dose [EID]50). c, Structure of UH15-38. d, Viability of primary wild-type MEFs exposed to the combination of murine TNFα (100 ng/ml), cycloheximide (250 ng/ml), and zVAD (50 μM) (TCZ) in the presence of UH15-38, GSK’872 or GSK’843. Viability was assessed 12 h after treatment. Data are mean ± SD, n = 3, examined over three biologically independent experiments. e, MEFs treated with TCZ in the presence of UH15-38 were examined for phosphorylated MLKL (pMLKL), total MLKL, ZBP1 and RIPK3 12 h after treatment. f, Comparative efficacy of UH15-38, GSK’872 and GSK’843 in human and mouse cells. g, Docking of UH15-38 into mouse RIPK3. N-terminal lobe (gold), αC helix (blue), activation loop (salmon), hinge region (grey), and C-terminal lobe (green) are shown. UH15-38 is shown in ball-and stick representation with a mesh surface, and atoms are color-coded by element. h, Detailed active- site view of UH15-38 docked into mouse RIPK3. Hydrogen bonds (2.0 – 3.1 Å) to the hinge residue M98 as well as the K51, E61 of the αC helix and D161 and F162 of the DFG motif are shown as red dashes. i, LigPlot showing interactions of UH15-38 with residues in mouse RIPK3. Hydrogen bonds are shown with red dashes and bond length in Angstroms. Cell viability in d was determined using Trypan Blue exclusion, and in f by the CellTiter-Glo assay. Groups were compared using the Log-rank (Mantel Cox) test (as in b).

To examine this possibility, we infected wild-type and Mlkl−/− mice with a lethal dose of IAV (H1N1 strain A/PuertoRico/8/1934; hereafter PR8) and assessed animal survival over a three-week time course. As Mlkl−/− mice are selectively deficient in RIPK3 kinase-driven necroptosis, we reasoned that results from these mice will foreshadow the effects of RIPK3 kinase inhibition during severe influenza in vivo. Whereas wild-type (WT) mice succumbed to IAV by 12 days after infection, ~70% of the necroptosis-deficient Mlkl−/− mice made complete recoveries, in line with our previous findings8 (Fig. 1b). Mice lacking Zbp1 or Ripk3 succumbed to this dose of IAV, as these animals lack both necroptosis and apoptosis signaling and therefore cannot control virus spread within the infected lung6,18 (Fig. 1b). Mice harboring a kinase-inactivating point-mutation in RIPK1 also succumbed to virus with kinetics and magnitude indistinguishable from wild-type animals, demonstrating that targeting RIPK1 kinase activity does not prevent IAV-induced lethality in the mouse model (Fig. 1b); these findings are consistent with our previous observations that RIPK3-driven necroptosis in IAV-infected murine cells does not necessitate the kinase activity of RIPK16. Thus, RIPK3 kinase-dependent necroptosis is not only unnecessary for animal survival or virus clearance but is actually deleterious to survival at lethal doses of IAV.

Based on these findings, we hypothesized that a pharmacological agent which selectively blocks RIPK3 kinase function, without interfering with RIPK3-induced apoptosis, will be able to protect mice from IAV-triggered necroinflammatory injury and lethality. RIPK3 represents a natural target for necroptosis blockade as it is the only kinase known to phosphorylate MLKL, and as phosphorylation of MLKL is the only known function of its kinase activity. This therapeutic strategy is, however, currently hindered by a lack of efficient and selective RIPK3 inhibitors for in vivo use. For example, GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) identified three molecules (GSK’872, GSK’843, and GSK’840) with potent activity against recombinant RIPK3 in vitro, but unexpectedly modest activity in cells20. Furthermore, even a two-fold increase in the concentration of these inhibitors triggered RIPK3-mediated apoptosis and unleashed consequent on-target toxicity20. In agreement with these findings, knock-in mice harboring a mutation (D161N) in RIPK3 designed to nullify necroptosis by inactivating catalytic function succumbed instead to fulminant RIPK3-mediated apoptosis in utero21. These observations raise the question of whether targeting necroptosis by blocking RIPK3 kinase function in vivo is even feasible or will inevitably produce on-target toxicity. Other groups, including ours, have since identified a subset of anti-cancer kinase inhibitors (e.g., ponatinib22,23 and dabrafenib24) capable of blocking RIPK3 without triggering on-target apoptosis, but these molecules are poorly-suited for non-oncological settings.

UH15-38 is a potent RIPK3 inhibitor.

To address the critical absence of a clinically viable RIPK3 inhibitor, we undertook a fresh approach to targeting this kinase. We focused on the molecule PD180970, originally developed as an inhibitor of the oncoprotein BCR-ABL, but shown in a proteomics analysis25 as capable of inhibiting RIPK2, a close mammalian homolog of RIPK3. We discovered that a PD180970 analog (PD166285) inhibited RIPK3 in vitro (IC50=1.08 μM) and was moderately potent at blocking necroptosis in cells (IC50 = 2.88 μM). We generated >40 PD166285 analogs, one of which showed potent anti-necroptosis activity in cells. We named this molecule UH15-38 (Fig. 1c). UH15-38 blocked TNFα-induced necroptosis in primary murine embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) at concentrations (IC50 = 98 nM) that were ~8.5-fold lower than GSK’843 (IC50 = 843 nM) and ~6-fold lower than GSK’872 (IC50 = 582 nM), the two best-performing GSK inhibitors of mouse RIPK320 (Fig. 1d). UH15-38 prevented phosphorylation of MLKL following necroptotic stimulation by TNFα (Fig. 1e), or upon enforced dimerization of RIPK3 (Extended Data Fig. 1a) in MEFs. UH15-38 also robustly inhibited necroptosis in an additional panel of human and mouse cell lines (Fig. 1f).

Notably, the previously developed GSK compounds showed markedly reduced anti-necroptotic potency in cells, compared to UH15-38 (Fig. 1d,f), despite robust inhibition of RIPK3 kinase function in vitro (Extended Data Fig. 1b), and in a RIPK3 target engagement assay in cellulo (Fig. 1f). These observations suggested that UH15-38 may display unique features in its RIPK3 binding mode that are distinct from GSK inhibitors and that translate strong RIPK3 binding into potent inhibition of necroptosis. To explore this possibility, we carried out molecular docking studies. These studies showed that UH15-38 can interact with the ATP binding pocket of both mouse and human RIPK3 in the active conformation, indicative of a Type I binding mode (Fig. 1g–i, Extended Data Fig. 1c). Consistent with the binding mode of other Type I kinase inhibitors, UH15-38 makes critical interactions with the backbone of the gatekeeper Met98 residue (Met97 in humans) in the hinge segment of the RIPK3 kinase domain (Fig. 1h,i; Extended Data Fig. 1c). Interestingly, modeling and X-ray crystal structure data26 for GSK’872 and GSK’843, respectively, displayed generally similar hinge binding poses to UH15-38 (Extended Data Fig. 1d,e), which may explain why the in vitro affinities of the GSK molecules for RIPK3 are on par with that of UH15-38. However, UH15-38 differed significantly from both GSK compounds in its interactions with the rear pocket of the RIPK3 active center. While GSK’872 and GSK’843 only made contacts with the backbone of the DFG motif of mouse RIPK3 (Extended Data Fig. 1d,e), UH15-38 not only engaged in similar interactions with the DFG motif, but also participated (via the phenol) in a broader network of hydrogen bonds and ionic-dipole interactions with the charged side-chains of catalytic Lys51 and the central residue in the αC helix, Glu61 (Fig. 1h,i; Extended Data Fig. 1c). Methylation of the phenol (e.g., as in the analog UH15-38 Me) resulted in loss of activity (Extended Data Fig. 1f). The elaborate interaction network unique to UH15-38 may account for the increased cellular potency of UH15-38 over the GSK molecules.

Although we found that UH15-38 binds RIPK1 in vitro (Extended Data Fig. 1b), it displayed no significant activity against RIPK1 kinase-driven caspase-8-dependent cell death27 induced in macrophages by the combination of LPS and a TAK1 inhibitor (Extended Data Fig. 1g), or in Ripk3−/− MEFs stimulated with TNFα and a TAK1 inhibitor (Extended Data Fig.1h), whereas the RIPK1 inhibitor GSK’547 was able to block such death in Ripk3−/− MEFs (Extended Data Fig. 1i). UH15-38 also did not inhibit either Gasdermin D cleavage (Extended Data Fig. 1j) or pyroptosis (Extended Data Fig. 1k) upon canonical activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome by Nigericin, demonstrating selectivity of this molecule for RIPK3-driven necroptotic cell death.

To assess if UH15-38 will be efficacious when administered systemically in vivo, we dosed wild type C57BL/6 mice with this compound at 30 mg/kg/day for four consecutive days via the intraperitoneal (i.p) route, and found that it achieved excellent accrual in lung tissues (Cmax = 42 μM) following this dosing regimen, which is ~8-fold higher than its levels in plasma (Extended Data Fig. 2a). UH15-38 also accumulated to significant levels in the liver, heart, kidney, and colon (Extended Data Fig. 2a). Next, we administered UH15-38 at 30 mg/kg/day for four consecutive days (i.p) to Casp8−/−Mlkl FLAG/FLAG mice28. In these mice, germline loss of caspase 8 triggers spontaneous multi-organ RIPK3 activation and phosphorylation of FLAG-tagged MLKL, but the N-terminal FLAG tag prevents MLKL from executing necroptosis28. This mouse model thus allows one to identify all cells harbouring phosphorylated MLKL without losing these cells to eventual necrotic demise. UH15-38 was able to effectively prevent MLKL phosphorylation in all tested organs (lung, liver, heart, kidney) in Casp8−/−Mlkl FLAG/FLAG mice, demonstrating its potential for therapeutic deployment in necroinflammatory diseases not just of the lung, but of these other organs as well (Extended Data Fig. 2b,c).

Comprehensive safety profiling of UH15-38 for off-target activity against a panel of 50 critical protein targets whose inhibition has been linked to potentially serious side effects in humans (InVEST, Reaction Biology) demonstrated that UH15-38 did not significantly inhibit any of these key targets (Extended Data Fig. 2d, Supplementary Table1). When profiled for inhibitory activity against a panel of 90 non-mutant human kinases (DiscoverX KinomeScan), UH15-38 displayed an S(35) selectivity score of ~0.25 (Supplementary Table 1), in line with other pre-clinical stage Type I kinase inhibitors, and on par with some of the current FDA-approved TKIs, such as Sorafenib [S(35) = 0.22] and Dasatinib [S(35) = 0.28].

UH15-38 was exceptionally well tolerated in vivo, with no detectable signs in any of these organs of on-target apoptosis as measured by cleaved caspase 3 (Extended Data Fig. 2e,f), or of general toxicity (Supplementary Table 2), even after extended dosing at 30 mg/kg/day (i.p) for seven consecutive days. There were no signs of liver toxicity (e.g., increase in serum alanine amninotransferase [ALT] or albumin levels), even though the compound reached peak concentrations >100 μM in this organ following dosing at 30 mg/kg/day (i.p) for four consecutive days (Extended Data Fig. 2a, Supplementary Table, 3). Collectively, these data indicate that UH15-38 possesses a pharmacological profile that is suitable for safe and effective in vivo deployment.

UH15-38 blocks IAV-activated necroptosis.

Before attempting to determine whether small molecule blockade of RIPK3 kinase activity by UH15-38 will be efficacious in mitigating IAV-induced pathology, we first sought to identify the primary cell type(s) undergoing RIPK3-dependent necroptosis in infected lungs, as these cell types will represent the dominant targets for pharmacological blockade of RIPK3 activity in vivo. We carried out scRNA-Seq analyses of IAV-infected lung cells and identified Type I alveolar epithelial cells (AECs) as the primary replicative niche for IAV in murine lungs; Type I AECs displayed significantly (84-fold) higher levels of IAV mRNA than any other cell type (Fig. 2a) and comprised over half of all IAV-positive cells in the infected lung (Fig. 2b). High levels of IAV mRNA were readily observed in Type I AECs by three days after infection, coincident with induction of Zbp1 mRNA (Fig. 2c). Death of Type I AECs is also highly correlated with compromised lung function and mortality in the mouse model15. Thus, although other lung cell types (most notably Type II AECs and ciliated cells) also represent important replication niches for IAV (Fig. 2a,b), we focused on examining the efficacy of UH15-38 in preventing necroptosis of IAV-infected Type I AECs.

Figure 2. UH15-38 selectively blocks IAV-induced necroptosis in Type I AECs.

a, IAV mRNA expression in lung cell types at 6 days after infection with PR8 (2500 EID50; i.n.). b, Distribution of IAV+ primary lung cell types at 6 days after infection c, IAV replication and ZBP1 expression in Type I AECs following IAV infection in vivo. d, Viability of primary Type I AECs from Zbp1+/+ and Zbp1−/− mice following infection with PR8 (MOI = 2). e, Expression of the indicated proteins in primary WT (Zbp1+/+) Type I AECs following PR8 (MOI=2) infection. f, Viability of Type I AECs after infection with PR8 (MOI = 2) and treatment with UH15-38, GSK’872 and GSK’843 with or without zVAD (50 μM). g, Photomicrographs of primary Type I AECs infected with PR8 (MOI = 2) and treated with UH15-38 (1 μM) with or without zVAD (50 μM). Images are representative of three independent experiments. h, Immunoblots of lysates from primary Type I AECs infected with PR8 (MOI = 2, 12h) in the presence of UH15-38. Data are representative of at least two independent experiments. i, Viability of M29 cells infected with PR8 (MOI =10, 24h) and treated with or without zVAD (50 μM) or UH15-38 (1 μM). j-l, Live human lung sections (n=3/group) infected with PR8 (5 × 106 pfu/ml) and treated with DMSO or UH15-38 (1 μM) for 24 h were stained for pMLKL (j, k) and IAV H1N1 antigen (j, l). Cell viability was determined by Trypan Blue exclusion in panels d, f, and i. Data are average of n=2 as in f and mean ± SD (n=3) as in d, i examined over three independent experiments with similar outcomes. Groups were compared using the unpaired two-sided Student’s t test (as in d), or by ordinary one-way ANOVA (as in i, k, l).

We isolated primary Type I AECs from mouse lungs by immunomagnetic selection with anti-aquaporin 5 (Aqp5) antibodies29,30. Staining these cells with the Type I AEC marker podoplanin31 showed them to be >95% pure (Extended Data Fig. 3a). Using these cells, we first established that they underwent ZBP1-dependent cell death upon infection with IAV (Fig. 2d). Whereas ~80% of infected wild type (Zbp1+/+) Type I AECs succumbed to IAV by 24 hours (h), similarly infected Type I AECs from littermate-matched Zbp1−/− animals remained mostly viable for over 48 h (Fig. 2d). Type I AECs strongly upregulated ZBP1 upon infection, possessed the entire ZBP1-dependent cell death machinery, and displayed markers of both necroptosis (pMLKL) and apoptosis (cleaved caspases-8 and −3) activation following infection with IAV (Fig. 2e). After confirming that UH15-38 was able to protect Type I AECs from canonical TNFα-induced necroptosis (IC50 = 114 nM, Extended Data Fig. 3b), we tested if UH15-38 could selectively prevent IAV-induced necroptosis, without impeding apoptosis, in this cell type. We found that UH15-38 was a highly potent inhibitor of IAV-induced necroptosis in primary Type I AECs (Fig. 2f, IC50=39.5 nM) and primary MEFs (Extended Data Fig. 3c, IC50=51.9 nM). Inhibition was selective for necroptosis, as UH15-38 did not prevent apoptosis (i.e., cell death in the absence of pan-caspase inhibitor zVAD) to any significant extent in these cells (Fig. 2f,g, Extended Data Fig. 3c,d). UH15-38 blocked IAV-induced phosphorylation of MLKL in Type I AECs (Fig. 2h) and MEFs (Extended Data Fig. 3d), without inhibiting cleavage of either caspase-8 or caspase-3. UH15-38 also prevented activation of MLKL and selectively inhibited necroptosis in cells infected with a panel of clinically relevant IAV and IBV strains (Extended Data Fig. 3e,f). UH15-38 completely blocked IAV-induced necroptosis in Ripk1−/− MEFs (Extended Data Fig. 3g). Although UH15-38 was derived from a BCR-ABL inhibitor with inhibitory activity against RIPK1 and RIPK2, neither the ABL inhibitor imatinib (Gleevec) nor the selective RIPK2 inhibitor CSLP3732 blocked IAV-triggered necroptosis in cells (Extended Data Fig. 3h,i), demonstrating that while UH15-38 can inhibit RIPK1, RIPK2 and ABL kinase activity in vitro (Supplementary Table. 1 and Extended Data Fig. 1b), the ability to target RIPK3 is central to its necroptosis-inhibitory activity in cells.

To examine if UH15-38 could block necroptosis in a virus-independent system of ZBP1 activation, we appended two Fv domains to the N-terminus of full-length murine ZBP1 (2xFv-ZBP1) and reconstituted Zbp1−/− MEFs with this chimeric construct. Chemical oligomerization of these Fv domains leads to ZBP1 activation, RIPK-mediated phosphorylation of MLKL, and necroptosis (Extended Data Fig. 3j,k). UH15-38 fully inhibited ZBP1-dependent RIPK3 activation and phosphorylation of MLKL and consequent necroptosis in this system (Extended Data Fig. 3j,k).

To test the efficacy of UH15-38 in human cells, we first reconstituted HeLa cells (which normally do not express RIPK3) with full-length human RIPK3 (HeLa-RIPK3) and exposing them to TNFα, in the presence of zVAD. We found that UH15-38 was again able to effectively prevent TNFα-induced necroptosis in HeLa-RIPK3 cells (Extended Data Fig. 3l,m). Most human cell lines (such as HeLa cells, as noted above) lack expression of one or more components of the necroptosis machinery, but we identified a human malignant mesothelioma-derived cell line (M29)33 which expressed ZBP1, RIPK3, and MLKL and underwent necroptosis following infection with IAV (Fig. 2i, Extended Data Fig. 3n). UH15-38 was able to prevent IAV-induced phosphorylation of MLKL at nanomolar concentrations (Extended Data Fig. 3n), resulting in full protection from IAV-induced necroptosis at 1 μM (Fig. 2i) in these cells. We observed that M29 cells manifested basally elevated levels of pRIPK3 (Thr224/Ser227), which were reduced upon infection, and further dampened by UH15-38 at concentrations ≥500 nM (Extended Data Fig. 3n). It should be noted that the relationship between RIPK3 autophosphorylation and catalytic activity remains incompletely understood, as the best-characterized sites of RIPK3 autophosphorylation (Thr231/Ser232 in mouse RIPK3 and Thr224/Ser227 in human RIPK3) are dispensable for RIPK3 catalytic activity34,35. Of particular clinical relevance, UH15-38 completely inhibited MLKL phosphorylation in human donor lung tissue, following infection of these tissues with IAV ex vivo (Fig. 2j–l). Together, these results demonstrate that UH15-38 is a potent and specific inhibitor of IAV-triggered necroptosis in murine and human cells.

UH15-38 did not induce apoptosis even at fifty times the IC50 dose for necroptosis blockade in type I AECs (IC50 = 39.5 nM) and MEFs (IC50 = 50 nM) and only modest toxicity was seen at 100x IC50 (Extended Data Fig. 4a,d). The toxicity manifested by UH15-38 at 100x IC50 was indeed RIPK3-dependent apoptosis, as it was accompanied by activation of caspases 8 and −3 (Extended Data Fig. 4b,e), and was eliminated in Ripk3−/− MEFs, or by addition of pan-caspase inhibitor zVAD.fmk (Extended Data Fig. 4c)). Thus, we have achieved in UH15-38 a compound with potent in cellulo efficacy in Type I AECs and other cell types, as well as wide separation of necroptosis-inhibitory activity from the capacity to trigger on-target apoptosis.

UH15-38 prevents IAV-driven lethality.

To test if UH15-38 can prevent IAV-triggered lethality when delivered as a systemic therapeutic, we next infected WT mice with a lethal dose of IAV (6000 EID50), treated these mice starting one day after infection with a four intraperitoneal (i.p.) once-daily doses of UH15-38 ranging from 7.5 mg/kg/day to 50 mg/kg/day, and compared their overall survival rates, as well as their rates of weight loss, to mice receiving vehicle alone. We found that doses of UH15-38 as low as 7.5 mg/kg/day prevented lethality in 40% of infected mice, with maximum protection observed at 30 mg/kg/day (Fig. 3a, Extended Data Fig. 5a). 80% of mice receiving the 30mg/kg/day dose of UH15-38 manifested significantly reduced (and delayed) weight loss and were fully protected from a lethal inoculum of IAV; these mice made full recoveries by three weeks after infection (Fig. 3a, Extended Data Fig. 5a). Increasing the dose of UH15-38 to 50 mg/kg/day did not provide any discernible additional benefit to survival outcomes of infected mice (Fig. 3a, Extended Data Fig. 5a). Evaluating UH15-38 for protection when administered over a shortened time course (30 mg/kg/day, once daily, for two days, starting one day after infection), or delaying administration by up to two days (i.e., starting UH15-38 at 30 mg/kg/day two or three days after infection) also reduced weight loss and prevented lethality in a significant proportion of mice infected with this highly lethal dose of virus (Extended Data Fig. 5b,c).

Figure 3. UH15-38 prevents lethality in severe influenza.

a, Survival analysis of mice infected with PR8 (6000 EID50) followed by i.p. administration of vehicle (n=20) or of UH15-38 at 50 mg/kg (n = 20), 30 mg/kg (n = 21), 15 mg/kg (n = 15), or 7.5 mg/kg (n = 15). Vehicle or UH15-38 was administered once-daily per the dosing schedule shown above the graph. b, Survival analysis of mice challenged with PR8 (4500 EID50; ~LD60) and treated i.p. with vehicle (n = 15) or with UH15-38 at 30 mg/kg, (n = 15); 15 mg/kg (n = 9), 7.5 mg/kg (n = 10), 3 mg/kg (n = 9), or 1 mg/kg (n = 9). Vehicle or UH15-38 was administered once-daily per the dosing schedule shown. c, Weight loss analysis of PR8 (4500 EID50)-infected mice (n = 15/group) following four once-daily i.p. doses of vehicle or UH15-38 (30 mg/kg). d, Survival analysis of mice infected with IAV H1N1 strain A/California/04/09 (600 EID50; ~LD60) and treated once-daily with vehicle (n = 10) or UH15-38 (30 mg/kg, i.p., n =13) per the dosing schedule shown. e, Survival analysis of PR8 (4500 EID50)-infected mice treated with UH15-38 (30 mg/kg, i.p.) starting either two (n = 10), three (n = 9), four (n = 10), or five (n = 10) days after infection. f, Survival analysis of PR8 (LD60)-infected Mlkl−/− (dashed lines) mice (vehicle group, n = 11; UH15-38 group, n = 10) or Ripk3−/− (solid lines) mice (vehicle group, n = 10; UH15-38 group, n = 9) following once-daily treatment with vehicle (black lines) or UH15-38 (30 mg/kg, i.p, red lines) administered per the dosing schedule shown. The LD60 for PR8 in Mlkl−/− mice was 6500 EID50, and for Ripk3−/− mice was 2500 EID50. Groups were compared using the Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test.

Remarkably, UH15-38 was fully (100%) protective against a less lethal, but more patient-relevant inoculum of IAV (4500 EID50; ~LD60), even at doses as low as 1 mg/kg/day (Fig. 3b). UH15-38 administered at 30 mg/kg/day not only delayed the onset of weight loss, but markedly mitigated the extent of such weight loss, compared to vehicle-treated controls, in mice infected with IAV at this dose (Fig. 3c). In contrast, mice receiving four once-daily doses of GSK’872 (30 mg/kg, i.p.) were not protected from IAV (PR8, LD60); in fact, GSK’872-treated mice fared worse than vehicle-treated controls over the three-week time course of this experiment (Extended Data Fig. 5d,e), possibly reflecting the on-target toxicity associated with this class of RIPK3 inhibitor18. UH15-38 was also able to afford full protection against lethality triggered by the H1N1 A/California/04/2009 strain of pandemic IAV (Fig. 3d, Extended Data Fig. 5f), demonstrating its potential for therapeutic benefit against seasonal and pandemic strains of IAV. Importantly, UH15-38 was able to protect almost all mice infected with IAV at the LD60 dose even when administered up to five days after infection (Fig. 3e, Extended Data Fig. 5g). This represents a significant advantage over the frontline antiviral agent oseltamivir (Tamiflu, Roche), which loses therapeutic benefit if administered more than 48 h after infection in mice36 and humans37. UH15-38 failed to protect Ripk3−/− or Mlkl−/− mice from IAV, confirming that its protective effects are mediated by blockade of RIPK3-MLKL signaling (Fig. 3f). In fact, UH15-38 treatment was notably superior to germline MLKL loss in preventing IAV-induced lethality at all doses of virus tested (Extended Data Fig. 5h,i; also compare Fig. 1b to Fig. 3a). We attribute this result to the benefit some early necroptosis may provide in sparking the antiviral immune response, or to some other currently unknown protective function of MLKL in maintaining baseline immune homeostasis or limiting early disease, both of which may be lost when MLKL is permanently ablated.

UH15-38 dampens IAV-induced lung injury.

To examine if UH15-38 prevented IAV-induced mortality by blocking necroptosis and consequent lung injury in vivo, we infected WT mice with a lethal dose of PR8 (6000 EID50), and administered UH15-38 (30 mg/kg) to these mice i.p. once-daily for a total of four days, starting 24 h after infection. Lungs from vehicle-treated mice showed significant evidence of necroptosis (i.e., pMLKL+) as early as day 3 post infection; by day 6, necroptosis was seen in a substantial fraction of Type I AECs (PDPN+) (Fig. 4a,b). Mice receiving UH15-38, however, showed markedly reduced numbers of pMLKL+ necroptotic cells at both these time points (Fig. 4a,b). As we have previously shown, the majority of pMLKL+ cells are also IAV+ 16. Importantly, UH15-38 did not significantly alter the proportion of infected cells undergoing apoptosis (CC3+) (Extended Data Fig. 6a,b), demonstrating that UH15-38 is a selective inhibitor of IAV-triggered necroptosis in vivo.

Figure 4. UH15-38 prevents necroptosis, inflammation, and injury in IAV-infected lungs.

a, b, Immunofluorescence staining of pMLKL (a) and quantification of pMLKL signal (b) in lung sections harvested from mice infected with PR8 (6000 EID50) and treated i.p. with either vehicle or UH15-38 (30 mg/kg once-daily), starting one day after infection, for up to four days. c, Levels of inflammatory mediators in BALF (n = 4/group) from mice infected with PR8 (6000 EID50) three days after infection. Mice were treated with either vehicle or UH15-38 (30 mg/kg once-daily) starting D1 post-infection. d, e, Lung images (d) and quantification (e) of neutrophil influx three days after infection with PR8 (6000 EID50), following treatment with either vehicle or UH15-38 (30 mg/kg, i.p., once-daily) starting one day after infection. f, H & E stained lung sections of vehicle- and UH15-38-treated mice nine days after infection (PR8;4500 EID50). Black arrow shows hyaline membranes and red arrow depicts denuded bronchioles. g, Histological scores of late lung injury nine days after infection. h. Arterial oxygen saturation (SpO2) measured in uninfected (n = 4/group) or infected mice (PR8, 4500 EID50; n = 6/group) 3 and 6 days after infection following treatment with vehicle or UH15-38 (30 mg/kg, i.p.) once daily for four days starting 24 h after infection. i, Frequencies of IFNγ-producing CD8+ T cells nine days after infection with PR8 in BALF of vehicle- and UH15-38-treated mice following in vitro stimulation with peptides corresponding to PB1 residues 703–711 or PA residues 224–233 (n = 10/group). Data are mean ± SD. n = 6 in b or n = 5 mice/group unless stated otherwise. Groups were compared using the two-sided Mann-Whitney U test (as in b, c, e, g, i, j), or by two-way ANOVA (as in h).

UH15-38 was able to prevent the release of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines (e.g., IL-1α, IL-33, IL-6, TNFα, CXCL1) from infected Type I AECs in culture (Extended Data Fig. 6c), and this activity was recapitulated in vivo. Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) from UH15-38 treated mice three days after infection, and following just two doses of UH15-38, also showed significantly reduced levels of key inflammatory cytokines and neutrophil chemoattractants (e.g., IL-1β, IL-6, IL-18, TNFα, CXCL1, GMCSF) (Fig. 4c), accompanied by a marked diminishment in the magnitude and extent of infiltrating neutrophils into pulmonary tissues (Fig. 4d,e), compared to animals receiving vehicle.

By nine days after infection, following the full four-dose cycle of vehicle or UH15-38, lungs from infected animals treated with UH15-38 showed a decrease in diffuse alveolar damage and the formation of hyaline membranes (Fig. 4f, black arrow; Fig. 4g), as well as notably reduced bronchiolar denudation (Fig. 4f, red arrow; Fig. 4g) and histological appearance of fibrosis (Fig. 4g). Staining pulmonary tissues for Tenascin C, a marker of fibrotic remodeling following injury38, confirmed that UH15-38 reduced the extent of fibrotic lung damage (Extended Data Fig. 6d,e). Consistent with this observation, BALF from mice receiving UH15-38 displayed significantly lower levels of the pro-fibrotic mediators (IL-1β, IL-6, IL-18, IL-17, and CCL5), compared to controls, early (three days) after infection (Fig. 4c, Extended Data Fig. 6f). Lungs from UH15-38 treated mice also displayed dampened alveolar and interstitial infiltration, accompanied by decreases in septal thickening and epithelial metaplasia (Extended Data Fig. 6g). In addition, UH15-38 completely blocked the release of IAV-triggered inflammatory cytokines IL-1β and IL-18 from necroptotic BMDMs (Extended Data Fig. 6h). Importantly, UH15-38-treated animals maintained relatively normal lung function, as measured by evaluating arterial oxygen saturation levels three and six days after infection (Fig. 4h), and by measuring airway resistance ten days after infection (Extended Data Fig. 6i).

UH15-38 did not alter the extent of virus replication and spread, or the rate of virus clearance from infected lungs (Extended Data Fig. 7a–c). UH15-38 also did not negatively impact the frequencies of IAV-specific CD8+ cytotoxic T cells (CTLs) in BALF (Extended Data Fig. 7d, Extended Data Fig. 8a), while the functional profile of these cells, as measured by IFNγ secretion, was improved (Fig. 4i, Extended Data Fig. 8b). Together, these results demonstrate that UH15-38 dampens neutrophil influx into infected pulmonary tissues and significantly reduces the extent of virus-triggered lung injury, without negatively impacting either virus clearance or anti-IAV CD8+ T cell responses.

Discussion.

In this study, we report that RIPK3 kinase activity, the key enzymatic driver of necroptosis, is a new host target for the prevention of lung inflammation and injury during severe influenza virus infections. We have developed a potent new RIPK3 kinase inhibitor, UH15-38, which effectively and selectively blocked activation of necroptosis in IAV-infected alveolar epithelial cells in vivo, preventing both the aberrantly high neutrophil recruitment that characterizes severe influenza, as well as the histological sequelae, such as the presence of hyaline membranes and widespread bronchiolar denudation, which are hallmarks of IAV-triggered lung injury and ARDS. Our data also demonstrate that the production and release of a set of critical inflammatory mediators capable of promoting secondary inflammation, fibrosis and cycles of necroinflammation, is almost completely dependent on necroptosis, highlighting the uniquely inflammatory nature of this form of cell death.

Our findings support a model in which UH15-38, by preventing necroptosis of infected type I AECs and other lung cell types, blocks the release of DAMPs, alarmins, and other inflammatory mediators from these cells. This reduces neutrophil influx into the lung, dampens necroinflammation, and prevents consequent loss of alveolar integrity and gas exchange function, without affecting either beneficial anti-IAV adaptive immune responses or virus clearance rates, both of which are fully enabled via the more immunologically silent pathway of apoptosis. Neither virus spread, progeny virion titers, or eventual virus clearance were significantly impacted by necroptosis blockade with UH15-38. In fact, we noted a small, but significant, increase in PA-specific CTLs in the BAL fluid of UH15-38 treated mice, compared to controls, suggesting that the anti-IAV T cell response may proceed more efficiently when the infected lung is not clogged by neutrophils (which by themselves can dampen CTL-driven antiviral responses39,40) or by other inflammatory mediators.

Strikingly, UH15-38 was efficacious even when first administered as late as five days after infection. To our knowledge, no other host-targeted therapeutic has been shown to prevent lethality in the mouse model when dosed this late after infection and suggests that blocking feed-forward cycles of neutrophil-driven necro-inflammation affords strong therapeutic benefit even during the peak of virus replication, which is a finding of significant clinical importance.

While the in vitro affinity of UH15-38 towards RIPK3 was on par with previous RIPK3 inhibitors GSK’843 and GSK’872, its activity in cells is markedly greater than either GSK compound, whose unexpected loss of cellular potency had been previously noted20. As GSK’872 showed comparable in cellulo target engagement to UH15-38, the difference in cellular potency between these compounds is unlikely to result from differential cell penetration. Rather, we propose that the ability of the phenol of UH15-38 to engage an interaction network in the back pocket of RIPK3 may define a binding mode that translates more efficiently into cellular potency. We have previously observed similar discrepancies between in vitro and cell-based inhibitors for another RIPK family member, RIPK232,41,42. In that case, a subset of RIPK2 inhibitors capable of specifically occluding the deep pocket along the αC helix were effective at blocking RIPK2-mediated cellular signaling, whereas other structurally similar RIPK2 inhibitors lacking the ability to occlude this pocket, were equally potent in vitro, but manifested poor cellular activity against RIPK2. Mechanistically, the ‘deep pocket occluders’, were able to allosterically interfere with RIPK2 binding to the E3 ligase XIAP, which is critical for RIPK2 signaling in cells. Our modeling suggests that similar engagement of the deep pocket of RIPK3 by UH15-38 may produce allosteric effects on RIPK3 kinase function beyond simple catalytic blockade. A comparison of the published structures of monomeric RIPK3 to the MLKL-bound form of RIPK3 showed that MLKL binding requires the displacement of the RIPK3 αC helix34 (Extended Data Fig. 9a,b); this transition is likely to be impeded by UH15-38 engagement of Glu61 in the αC helix, but whether this occurs in cells remains to be verified.

As several other respiratory viruses, including RSV and SARS-family CoVs have been shown to trigger necroptosis in infected lungs5,43, and as necroptosis has also been implicated in the pathogenesis of several chronic inflammatory and fibrotic lung diseases, such as COPD and IPF44, our findings suggest that necroptosis blockade may represent a therapeutic strategy for a range of lung pathologies, whether of viral etiology or otherwise. Because RIPK3 is essential for all known pathways of necroptosis, RIPK3 kinase inhibitors such as UH15-38 will potentially have benefit in a wider range of acute and chronic inflammatory conditions involving necroptosis than will anti-TNF approaches or RIPK1 inhibitors.

Materials and Methods.

Mice, cells, viruses, reagents

Zbp1−/− 45, Mlkl−/− 46, Ripk3−/− 47, Ripk1K45A 48, Casp8−/−MlklFLAG/FLAG 28 animals have been described previously. C57BL/6 mice were obtained from Taconic and were allowed at least 1 week to acclimate to housing conditions before use in experiments. Mice were randomly assigned into groups before each experiment. Mice were housed in SPF facilities at the Fox Chase Cancer Center, St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, and all in vivo experiments were conducted under protocols approved by the Committee on Use and Care of Animals at these institutions. No statistical methods were used to predetermine sample size. The investigators were not blinded to allocation during experiments. Primary MEFs were obtained from E14.5 embryos and were immortalized using the 3T3 protocol. Immortalized MEFs were routinely tested by qPCR and by immunoblot analyses for protein expression. To create the 2xFv-RIPK3 and 2xFv-ZBP1 constructs, tandem inducible dimerization domains (hereafter 2xFv) derived from the protein FKBP were placed at the N-terminus of full length human RIPK3 or murine ZBP1. 2xFv-tagged constructs were cloned into the Dox-inducible vector pRetroX-TRE3G (631188, Clontech). Immortalized Ripk3−/− or Zbp1−/− MEFs inducibly expressing 2xFv-RIPK3 or 2xFv-ZBP1, respectively, were produced using the retroviral Tet-On 3G System. Activation of RIPK3 or ZBP1 in cells expressing the 2xFv constructs was achieved by treatment with doxycycline (5 μg/ml) for 12 h, followed by exposure to B/B homodimerizer, AP20187 (100 nM). HeLa (ATCC, CCL-2) cells were retrovirally transduced with full-length human RIPK3 to generate HeLa-RIPK3 cells. Mouse adapted strains of Influenza A/Puerto Rico/8/1934 (H1N1), A/California/04/2009 (H1N1), Influenza A/Brisbane/10/2007 (H3N2), A/Singapore/INFIMN-16-0019/2016 (H3N2), Influenza B/Florida/04/2006, and B/Colorado/06/2017 were propagated by allantoic cavity inoculation of 10 day-embryonated chicken egg. Influenza virus titers were determined by plaque assay on MDCK cells obtained from the ATCC. For necroptosis induction, MEFs and Type I AECs were infected with virus or treated with 100 ng/mL TNFα (R&D Systems, 410-MT) in the presence of 250 ng/mL cycloheximide (Sigma, 01810) and 50 μM zVAD (Bachem, N-1510); RAW264.7 cells were treated with 100ng/ml LPS (Sigma, L2630), 20 μM IDN-6556 (Medkoo, 210530); immortalized Bone marrow derived macrophages (iBMDM, gift of Dr. Kate Fitzgerald) were treated with 10ng/ml LPS, 20 μM IDN-6556, 100nM 5z-7-oxozaenol (MedChemExpress, HY-12686); HeLa RIPK3 and U937 cells were treated with 20 ng/ml human TNFα (R&D Systems, 210-TA), 20 μM IDN-6556, 100 nM Smac Mimetic SM164 (MedChemExpress, HY-15989); FADD-deficient Jurkat cells were treated with 20ng/ml human TNFα. RIPK1 dependent apoptosis in iBMDM was induced by treatment with 10ng/ml LPS and 100 nM 5z-7-oxozaenol. All cell lines obtained from ATCC were maintained in DMEM 10% FBS, 1mM sodium pyruvate, 1x GlutaMAX and 1% penicillin/streptomycin at 37°C and 5% CO2. The human malignant mesothelial cell line M29 was a gift of Dr. J. Testa, and maintained in RPMI medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 1x GlutaMAX and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. M29 cells were authenticated for use by the Cell Culture Facility at Fox Chase Cancer Center. Immortalized BMDMs were authenticated by FACS for the presence of BMDM markers. All other cell lines were authenticated by ATCC. All cell lines were routinely tested for Mycoplasma and only used when negative for Mycoplasma.

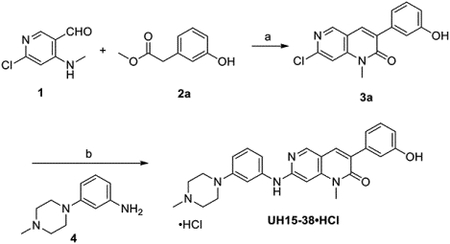

Synthesis of UH15-38 and analogs

UH15-38 was prepared in a two-step procedure, as described below, and used as the hydrochloride salt (UH15-38.HCl) in all experiments. UH15-38.HCl is commercially available under license from Tocris Bioscience, a Bio-Techne brand.

Reagents and conditions: (a) KF/Al2O3, DMA, 0 °C-rt, 2 h; (b) (i) Pd(OAc)2, Xantphos, Cs2CO3, dioxane, 80 °C, 24 h; (ii) 2.0 M HCl in diethylether, diethylether: MeOH, 0 °C – rt, 16 h.

Synthesis of 7-Chloro-3-(3-hydroxyphenyl)-1-methyl-1,6-naphthyridin-2(1H)-one (3a)

To a stirred solution of 1 (1.0 g, 5.71 mmol) and 2a (1.60 g, 5.71 mmol) in dry DMA (15 mL), KF/Al2O3 (6.0 g, 40 wt%) was added at 0 °C portion wise under argon. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature (rt) for 2 h. After completion, the reaction mixture was filtered through Celite and the residual solid was washed with MeOH and DCM several times. The filtrate was concentrated, and the residue was purified by column chromatography over silica gel using 25% EtOAc/hexane to give 3a (1.30 g, 80%) as a light-yellow solid. 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 9.56 (s, 1H), 8.78 (s, 1H), 8.15 (s, 1H), 7.64 (s, 1H), 7.24 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 7.13–7.05 (m, 2H), 6.80 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H), 3.64 (s, 3H); 13C-NMR (151 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 160.5, 157.0, 150.5, 150.4, 150.3, 145.9, 137.0, 134.2, 132.5, 129.2, 119.4, 115.8, 115.4, 108.5, 29.8.

Synthesis of UH15-38

To a stirred solution of 3a (1.0 g, 3.50 mmol) and 4 (668 mg, 3.50 mmol) in dioxane (20 mL), were added Xantphos (405 mg, 0.70 mmol) and cesium carbonate (2.28 g, 7.0 mmol). The reaction mixture was degassed with argon for 10 min. Pd(OAc)2 (79 mg, 0.35 mmol) was added to the mixture and the flask flushed with argon for another 10 min. Next, the reaction mixture was heated at 80 °C for 24 h. The reaction mixture was then partitioned between ethyl acetate and water, dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered, concentrated and purified by column chromatography using silica gel (3 % MeOH/DCM) to give UH-15-38 (540 mg, 35 %) as a white solid. mp. 206–208 °C. 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.47 (s, 1H), 7.72 (s, 1H), 7.26–7.23 (m, 4H), 7.13 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H), 6.89 (s, 1H), 6.81 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 6.80 (d, J = 6 Hz, 1H), 6.66 (s, 1H), 3.50 (s, 3H), 3.26 (t, J = 4.5 Hz, 4H), 2.64 (t, J = 4.5 Hz, 4H), 2.39 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3) δ162.2, 157.0, 156.4, 152.5, 150.5, 146.6, 140.3, 137.8, 135.2, 130.3, 129.6, 128.5, 120.3, 116.2, 115.5, 112.9, 112.3, 111.4, 109.0, 89.0, 55.0, 48.7, 46.0, 29.6; HRMS (ESI): m/z [M + H]+ calcd for C26H28N5O2: 442.2238; found: 442.2241.

Synthesis of UH-15-38•HCl

UH-15-38 (500 mg, 1.13 mmol) was dissolved in 10 mL diethyl ether and then 2 mL methanol was added to speed up dissolution. 2.0 M HCl in diethyl ether (2.82 mL, 5.65 mmol) was added to the mixture dropwise with constant and vigorous stirring at 0 °C. Stirring then continued at rt for 16 h. The precipitate was collected by filtration, washed with diethyl ether, and dried under vacuum to furnish UH15-38•HCl (450 mg, 83%) as a white solid; mp. 245–250 °C; 1H-NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 11.01 (bs, 1H), 10.10 (bs, 1H), 8.63 (s, 1H), 8.04 (s, 1H), 7.29 – 7.26 (m, 1H), 7.23 – 7.21 (m, 2H), 7.10 (s, 1H), 7.05 – 7.03 (m, 2H), 6.83 (s, 1H), 6.78 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 2H), 3.84 – 3.81 (m, 2H), 3.54 (s, 3H), 3.49 – 3.46 (m, 2H), 3.19 – 3.12 (m, 4H), 2.81 (s, 3H); 13C-NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 160.8, 157.0, 152.1, 150.6, 147.7, 143.0, 138.9, 137.0, 134.3, 130.2, 129.5, 129.0, 119.3, 115.7, 115.2, 113.1, 112.4, 110.6, 108.9, 92.5, 51.8, 45.3, 41.9, 29.5; HRMS (ESI): m/z [M + H]+ calcd for C26H28N5O2: 442.2238; found: 442.2236. Purity was determined to be 98% by analytical high-performance liquid chromatography (WATERS 2545 HPLC) using binary gradient pump Kinetex 5 μm C18 100 Å column (250 × 4.6 mm). UV absorption was monitored at λ = 254 nm. The injection volume was 100 μL. The gradient of acetonitrile/water (water containing 0.1% formic acid) was 2:98 to 98:2 over a total run time of 30 min and a flow rate of 1.2 mL/min. tR = 14.44 min.

Synthesis of UH15-38Me

Reagents and conditions: (a) KF/Al2O3, DMA, rt, 2 h; (b) Pd2(dba)3, Xantphos, Cs2CO3, dioxane, MW, 90 °C, 20 h.

Synthesis of 7-Chloro-3-(3-methoxyphenyl)-1-methyl-1,6-naphthyridin-2(1H)-one (3b)

To a stirred solution of compound 1 (70 mg, 0.41 mmol), 2b (88 mg, 0.50 mmol) in DMA (2 mL) was added KF/Al2O3 (420 mg) at rt and the reaction mixture was stirred at rt for 2 h. After completion of the reaction, filter the reaction mixture through a small Celite pad and water (5 mL) was added to the filtrate. The organic layer was extracted with ethyl acetate (2 × 15 mL). The combined organic layers washed with brine solution, dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, and filtered. The solvents were removed under reduced pressure and purification of the residue on combiflash chromatography (0–10% ethyl acetate in hexane) furnished the product 3b as a white solid. mp. 165–167 °C; yield: 83 mg (67%); 1H-NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.61 (s, 1H), 7.81 (s, 1H), 7.37 (t, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 7.26 – 7.23 (m, 3H), 6.98 – 6.96 (m, 1H), 3.86 (s, 3H), 3.72 (s, 3H); 13C-NMR (151 MHz, CDCl3) δ 161.1, 159.4, 151.8, 149.8, 145.9, 136.8, 133.9, 133.7, 129.3, 121.2, 115.8, 114.5, 114.3, 107.8, 55.3, 29.8.

Synthesis of UH15-38Me

To a stirred solution of compound 3b (75 mg, 0.25 mmol), 3-(4-methylpiperazin-1-yl) aniline 4 (48 mg, 0.25 mmol), Cs2CO3 (162 mg, 0.5 mmol), Xantphos (29 mg, 0.05 mmol), Pd2(dba)3 (23 mg, 0.03 mmol) in dioxane (2 mL) and flushed argon gas for 10 minutes and refluxed the reaction mixture at 90 °C for 20 h. After completion of the reaction, the reaction mixture was filtered through a small Celite pad and water (2 mL) was added to the filtrate. The organic layer was extracted with ethyl acetate (2 × 15 mL). The combined organic layers washed with brine solution, dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, and filtered. The solvents were removed under reduced pressure and purification of the residue on combiflash chromatography (0 – 10% methanol in CH2Cl2) furnished UH15-38Me as a pale-yellow solid. mp. 70–72 °C; yield: 22 mg (19%). 1H-NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.44 (s, 1H), 7.71 (s, 1H), 7.34 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.31 – 7.23 (m, 2H), 6.93 – 6.90 (m, 2H), 6.88 – 6.84 (m, 2H), 6.77 – 6.74 (m, 1H), 6.69 (s, 1H), 3.86 (s, 3H), 3.58 (s, 3H), 3.26 (t, J = 4.7 Hz, 4H), 2.60 (t, J = 4.8 Hz, 4H), 2.37 (s, 3H); 13C-NMR (151 MHz, CDCl3) δ 162.0, 159.3, 157.0, 152.5, 150.4, 146.5, 140.3, 137.9, 135.0, 130.2, 129.1, 128.7, 121.2, 114.2, 113.8, 112.5, 111.9, 111.2, 108.9, 88.9, 55.3, 55.0, 48.7, 46.1, 29.5. HRMS (ESI): m/z [M + H]+ calcd for C27H30N5O2: 456.2394, found: 456.2385. Purity was determined to be 98% by analytical high-performance liquid chromatography (WATERS 1525 HPLC) using binary pump Kinetex 5 μm C18 100 Å column (250 × 4.6 mm). UV absorption was monitored at λ = 254 nm. The injection volume was 15 μL. The gradient of acetonitrile/water (both containing 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid) was 2:98 to 90:10 over a total run time of 30 min and a flow rate of 1 mL/min. tR = 17.365 min.

NMR spectra and HPLC chromatograms of UH15-38•HCl and UH15-38Me are shown in Supplementary Table 4.

Pharmacokinetic and toxicological assessment of UH15-38.

Pharmacokinetics of UH15-38 were evaluated in male (9–10 weeks old) C57Bl/6 mice following once-daily dosing at 30 mg/kg for four consecutive days. UH15-38 was administered by i.p. injection, and tissues were collected from three mice for each time point. Plasma was generated by standard centrifugation techniques and immediately frozen. Drug levels are determined by mass spectrometry using an ABSciex 6500 mass spectrometer and multiple reaction monitoring analytical methods. Pharmacokinetic parameters were calculated using a non-compartmental model (Phoenix WinNonlin, Pharsight Inc.). UH15-38 concentrations in each tissue were modeled separately. All procedures were approved by the IACUC at the UF Scripps Institute for Biomedical Innovation & Technology. For toxicological assessment of UH15-38, three male and three female C57Bl/6 mice were dosed i.p. for 7 days with UH15-38 at 30 mg/kg/day, and potential toxicity of the drug was assessed 24 h after the last dose. Comprehensive blood chemistry and blood cell composition analyses were carried out by IDEXX Bioanalytics. Effects of UH15-38 on whole-animal and organ weights were assessed by Tufts University Comparative Medicine Services (TUCMS), and histological examination of tissues was carried out by a certified veterinary pathologist (Dr. Lauren Richey, TUCMS). IHC assessment of cleaved caspase 3 was carried out by the Histology Facility at the Fox Chase Cancer Center.

In vitro RIPK3 and RIPK1 kinase and in cellulo RIPK3 target engagement assays

ADPGlo RIPK3 kinase assays utilizing hRIPK3 (1–313 aa) construct expressed in Sf9 cells were performed as previously described22. NanoBRET target engagement assays were performed as described earlier32. Briefly, NanoLuc-RIPK3 (Promega) was transfected into HEK293T cells. After 24–48 hr, cell density was adjusted to 2 × 105 cells/ml, and cells were incubated with PBI-6948 nanoBRET tracer (Promega) and various inhibitor concentrations for 2 h at 37°C. Next, NanoLuc substrate mix (Promega) was added, and BRET ratios were determined using a Victor3V plate reader (PerkinElmer). Determination of the affinities of the drugs towards recombinant RIPK1 and RIPK3 kinase domains was performed by DiscoverX using the KinomeScan platform, which is based on a competition binding assay that quantitatively measures the ability of a compound to compete with an immobilized, active-site directed ligand. An 11-point 3-fold serial dilution of UH15-38 compound was tested in duplicate. Binding constants (Kd) were calculated with a standard dose-response curve using the Hill equation: Response = Background + (Signal – Background)/ (1 + (KdHill Slope / DoseHill Slope). The Hill Slope was set to −1. Curves were fitted using a non-linear least square fit with the Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm.

Molecular docking

Docking of UH15-38 into the RIPK3 kinase domain was performed using standard protocol of AutoDock Tools1.5.6 (http://autodock.scripps.edu), which is computed with MGLTools-1.5.4 (http://mgltools.scripps.edu). UH15-38 was created through ChemDrawBio and subjected to energy minimization using MM2 force field. The coordinates of mouse and human RIPK3 were extracted from crystal structures of mouse RIPK3 (PDB: 4M66) and human RIPK3 (PDB: 7MX3) using BIOVIA Discovery Studio Visualizer 2016 software (http://www.3dsbiovia.com). Autodock Tools were used and grid boxes for docking simulations were selected based on each binding site. The docking results were analyzed using PyMOL visualization software (version PyMOL™ 2.5.4) and UCSF Chimera 1.1549. When needed, hydrogens and charges were assigned to docking models in Chimera prior to assessment of contacts between drug and RIPK3. 2D analysis was performed using LigPlot+ (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/thornton-srv/software/LigPlus/)50 and identified hydrogen bonds and salt bridges were confirmed in Chimera. High resolution rendering of models was done with Chimera.

Isolation of Type I AECs

C57BL/6 mice were anesthetized with 3% isoflurane and cardiac perfusion carried out by inserting a 23 G needle attached to a 10 ml syringe containing RPMI (supplemented with 25 mM HEPES, at 37°C) into the right ventricle. The trachea was then exposed, and a small incision was made on the ventral surface. A polyethylene tube (PE50, BD, 427410) was inserted through the incision and fixed inside the trachea by suture. Lungs were lavaged three times with PBS containing 5 mM EGTA and 5 mM EDTA and instilled with 3ml of RPMI containing 25 mM HEPES, 10% Dextran40, and 4.5 U/ml Elastase, immediately followed by 0.5 ml of 1% (w/v) low melting temperature agarose in water. The trachea was tied below the incision point and the tube was removed. Mouse carcasses were allowed to cool for 5 minutes at 4°C, lungs were then excised and placed into 15 ml tubes with 2 ml of Wash Buffer (RPMI containing 25 mM HEPES, 10% Dextran40, and 4.5U/ml Elastase) and rocked for 45 min at 25°C (Roto-Therm Plus, Benchmark Scientific, G0520075). After digestion, lungs were disintegrated in 6 cm plates containing 8 ml RPMI supplemented with 25 mM HEPES, 20% FBS, and 100 μg/ml DNAse I for 10 min. Crude single cell fractions were then serially passed through 100 μm, and then through 40 μm cell strainers. Single cells were centrifuged (250g for 8 min), rinsed in Wash Buffer, and incubated with 40 μg/ml rabbit polyclonal anti-Aqp5 antibody at 4°C in a rotator for 40 min. After washing (3x) and resuspension in Wash Buffer, cells were incubated with 400 μl pre-washed goat anti-rabbit IgG BioMag® beads and rotated at 4°C for 40 min. Antibody-bound cells were precipitated using a magnetic field, and any unbound cells were removed by washing in Wash Buffer. Antibody-bound cells were washed and cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) containing 10% FBS, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 1x GlutaMAX (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. The purity of Type I AEC isolated in this manner was assessed by staining for podoplanin with an anti-podoplanin antibody (1:500), and for the presence of contaminating fibroblasts using an antibody to CD140a (PDGFRα) antibody (1:500).

Single-cell gene expression data and analysis

Single-cell gene expression analyses were performed on datasets of mouse lung cells isolated pre-infection and 1, 3, and 6 days after infection51. Data were processed as previously described51. Briefly, sequencing data were processed using CellRanger (v.3.0.2, 10x Genomics) with the mouse mm10 reference genome adapted to include the influenza A/Puerto Rico/8/1934 genome. Feature-barcode matrices were then loaded into Seurat (v.3.0.0.900) using a scaling factor of 1×104 for subsequent analysis and data visualization52. Log-normalization of gene-expression counts was performed, and variable genes were identified using the ‘vst’ method with default parameters. Next, gene expression was scaled to regress out any effects of total number of transcripts, cell cycle scores, and percent mitochondrial expression. Based on an elbow plot of PC standard deviations, 25 principal components (PCs) were selected for t-SNE dimensionality reduction and clustering using shared-nearest-neighbor modularity algorithm in Seurat. Marker gene expression was analyzed to identify major lung cell types, including epithelial (Epcam), endothelial (Pecam1), mesenchymal (Col1a2), and immune (Ptprc). Data were then subset on non-immune cells and dimensionality reduction using t-SNE and clustering was performed.

Immunoblotting

Cells were lysed in RIPA lysis buffer (Thermo Scientific, 89900) containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Thermo Scientific, 815-968-0747). SDS sample buffer was added, and the samples were boiled for 10 min. Protein samples were then loaded onto 12–15% SDS-PAGE gels and proteins transferred overnight at 4°C onto PVDF membranes. The membranes were then blocked in PBS containing 0.1% Tween-20 and 3% BSA, and treated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C, followed by HRP-conjugated goat secondary antibodies at room temperature for 4 h. Membranes were washed and visualized following brief exposure to ECL substrate (Thermo Fisher, 34578). The following primary antibodies were used for immunoblotting: Mouse monoclonal anti-ZBP1 (1:2000), Rabbit polyclonal anti-ZBP1 (1:1000), Rabbit polyclonal anti-RIPK3 (1:2000), Rabbit monoclonal anti-mouse (phospho T231/S232) RIPK3 (1:1000), Rabbit monoclonal anti-human RIPK3 (1:2000), Rabbit monoclonal anti-human (phospho S227) RIPK3 (1:1000), Rabbit monoclonal anti-mouse (phospho-S345) MLKL (1:2000),Rabbit monoclonal anti-human (phospho-S358) MLKL (1:2000), Rat monoclonal anti-MLKL (1:1000), Rabbit polyclonal anti-mouse MLKL (1;1000), Rabbit monoclonal anti-human MLKL (1:1000), Mouse monoclonal anti-RIP1 (1:1000 ) Rabbit monoclonal anti-FADD (1:1000), Rabbit polyclonal anti-human FADD (1:1000), Mouse monoclonal anti-human caspase 8 (1:1000), Rabbit polyclonal anti-mouse caspase 8 (1:1000), Rabbit monoclonal anti-mouse cleaved caspase-8 (1:1000), Rabbit polyclonal anti-caspase-3 (1:1000), Rabbit polyclonal anti-influenza A virus NP (1:5000), Mouse monoclonal anti-influenza A virus NS1 (1:2000), Mouse monoclonal anti-influenza B Nucleoprotein (1:2500), Rabbit polyclonal anti-GSDMD (1:1000), Mouse monoclonal anti-β-actin ((1:2000)), Mouse monoclonal GAPDH (1:2000), Rabbit polyclonal anti-alpha tubulin (1:5000). Following secondary antibodies were used: Peroxidase-conjugated Affinity purified Goat anti-mouse IgG (H+L) (1:5000), Peroxidase-conjugated Affinity purified Goat anti-rat IgG (H+L) (1:2500), Peroxidase-conjugated Affinity purified Goat anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) (1:10000).

Immunofluorescence microscopy

Cells were fixed with freshly prepared 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde, permeabilized in 0.2% (v/v) Triton X-100, blocked with MAXblock™ Blocking Medium (Active Motif), and incubated overnight with primary antibodies at 4°C. After three washes in PBS, slides were incubated with fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature. Following an additional three washes in PBS, slides were mounted in ProLong Gold antifade reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and imaged by confocal microscopy on a Leica SP8 instrument. Fluorescence intensity was quantified using Leica LAS X software. The following antibodies were used for immunofluorescence studies: anti-phosphorylated murine MLKL53 (1:1000), rabbit polyclonal anti-cleaved caspase 3 (1:500) and anti-podoplanin (1:500), Donkey anti-Rabbit IgG (H+L) Highly Cross-Adsorbed Secondary Antibody (1:500), Alexa Fluor™ 594, Donkey anti-Mouse IgG (H+L) Highly Cross-Adsorbed Secondary Antibody (1:500), Alexa Fluor™ 488, Donkey anti-Rabbit IgG (H+L) Highly Cross-Adsorbed Secondary Antibody (1:500), Alexa Fluor™ 488, Donkey anti-Mouse IgG (H+L) Highly Cross-Adsorbed Secondary Antibody, Alexa Fluor™ Plus 594 A32744 (1:500).

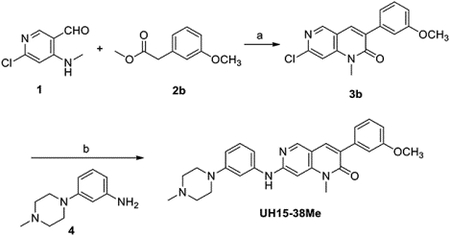

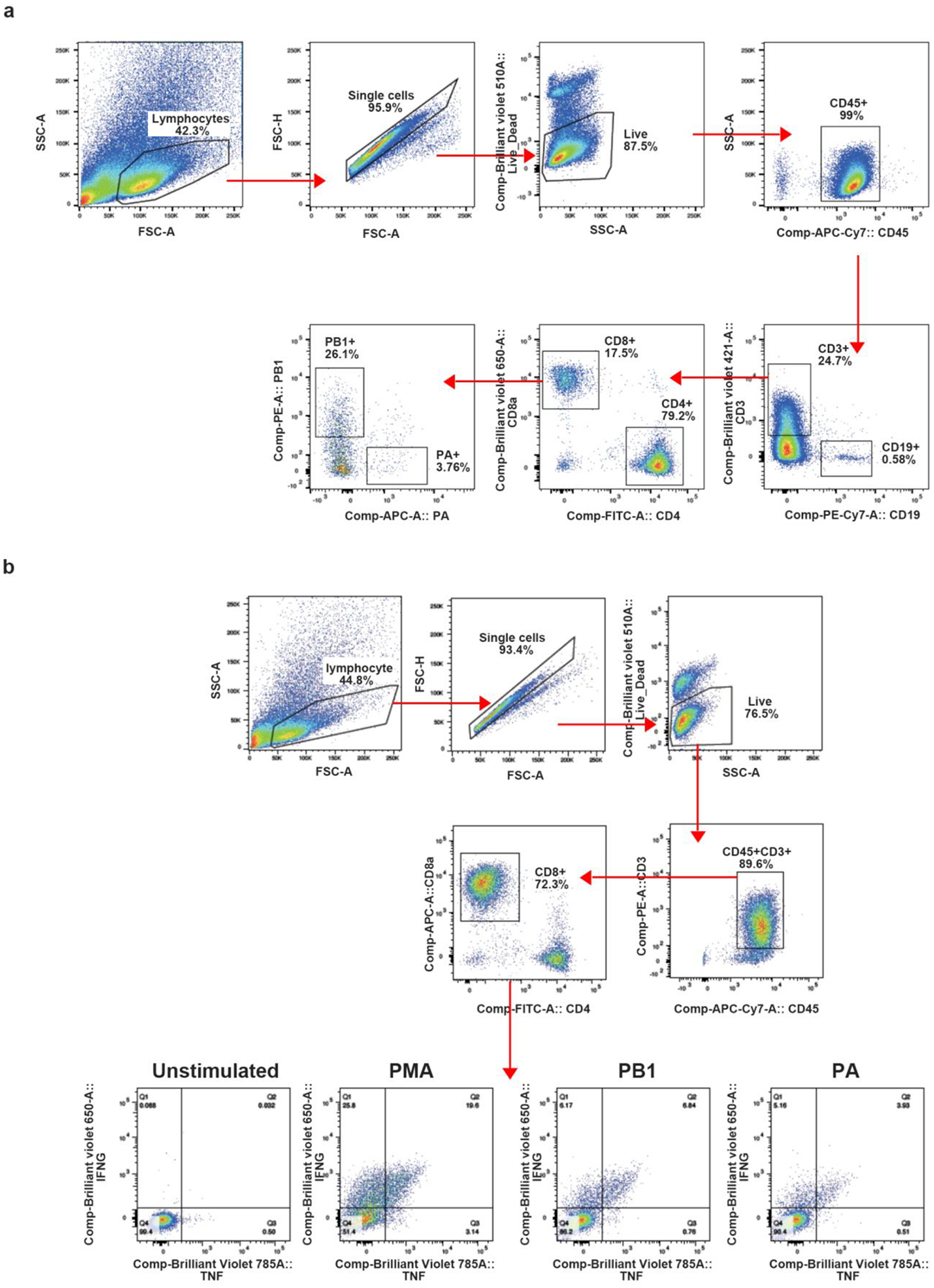

In vivo IAV studies

Age- (8–12 week-old) and sex-matched mice were anesthetized with Avertin (2,2,2-tribromoethanol) or 3% isoflurane and infected intranasally with virus inoculum diluted in endotoxin-free saline. UH15-38 dissolved in DMSO was diluted to the desired concentration in carrier solvent containing 10% Solutol HS (MedChemExpress, HY-Y1893) in normal saline for in vivo use. Mice were treated i.p. with UH15-38 or vehicle (DMSO plus an equivalent volume of carrier solvent) in 400 μL. Treatment groups that did not require drug treatment on a particular day(s), were administered vehicle. Mice were either monitored for survival over a period of 21 days or sacrificed at defined time points for analysis of histology and virus replication. Mice losing >30% body weight were considered moribund and euthanized by gradual CO2 asphyxiation. Titration of virus was conducted by standard plaque assay of diluted lung homogenates on monolayers of MDCK cells, and plaques were scored after three days of incubation. IAV-specific CD8+ T cell responses were assessed on cells isolated from bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid collected 9 days after infection. BAL washes were performed using 2 mL of sterile 1x DPBS. BAL washes were centrifuged at 500 x g for 5 min before performing red blood cell lysis on cell pellets. To analyze the frequency of IAV-specific CD8+ T cells, peptide:MHC tetramer staining was performed on 1×106 total BAL cells per sample. Cells were incubated with PE-PB1 (residues 703 – 711) and APC-PA (residues 224–233) tetramers at a dilution of 1:750 for each for 1 h on ice. Following incubation with tetramers, cells were washed with FACS buffer (1% FBS and 1 mM EDTA in 1x DPBS) and then incubated with Trustain FcX anti-mouse CD16/CD32 (Biolegend) (1:100) for 10 min at room temperature. Cells were then stained for surface markers with a cocktail of the following antibodies and viability dye for 30 min on ice: Ghost Dye Violet 510 (1:100), APCFire750 anti-mouse CD45 (1:100), PE-Cy7 anti-mouse CD19 (1:100), BV421 anti-mouse CD3 (1:100), BV650 anti-mouse CD8a (1:200), and FITC anti-mouse CD4 (1:200). To analyze the frequency of cytokine producing CD8+ T cells, intracellular cytokine staining was performed following stimulation with IAV peptides. For each condition, 5×105 cells from each sample were plated in a 96-well U-bottom plate. Cells were incubated with either PB1 (residues 703 – 711) or PA (residues 224–233) peptides at a concentration of 1 μM in complete RPMI in the presence of Protein Transport Inhibitor Cocktail, containing Monensin and Brefeldin A, (eBioscience, 1:500) for 4 h at 37 degrees C. As positive control, cells were incubated with Cell Stimulation Cocktail plus protein transport inhibitors, containing phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA), Monensin, and Brefeldin A (eBioscience, 1:500). Following stimulation, cells were washed with FACS buffer and then incubated with Trustain FcX anti-mouse CD16/CD32 (Biolegend) (1:100) for 10 min at room temperature. Surface staining was then performed by incubating with a cocktail of the following antibodies for 30 min at room temperature: Ghost Dye Violet 510 (1:100), APCFire750 anti-mouse CD45 (1:100), PE anti-mouse CD3 (1:100), APC anti-mouse CD8a (1:200), and FITC anti-mouse CD4 (1:200). Intracellular staining was then performed by fixing and permeabilizing cells in 100 μL of fix-perm solution (BD Biosciences) for 20 min on ice. The cells were then washed with permeabilization buffer and incubated with BV650 anti-mouse IFNγ (1:100) for 30 min on ice. For flow cytometry, all samples were analyzed on an LSR Fortessa (BD Biosciences) using BD FACSDIVA Software version 8.0.1.

Histological assessment of IAV-infected tissues

For assessment of phosphorylated MLKL (pMLKL) in human pulmonary tissues, frozen human lung slices were purchased from the Institute for In Vitro Sciences Inc, and cultured per instructions provided by the supplier. Following infection of these sections with IAV, immunohistochemical staining of pMLKL was performed on a Ventana Discovery XT automated staining instrument (Ventana Medical Systems) using Ventana reagents, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Slides were de-paraffinized using EZ Prep solution (950–102) for 16 min at 72 °C. Epitope retrieval was accomplished with CC1 solution (950–224) at 95–100 °C for 30 min. Rabbit primary antibody to human pMLKL (1:20) dilution) and goat polyclonal antibody to Influenza A (1:1000) were titered with a TBS antibody diluent into user fillable dispensers for use on the automated stainer. Immune complexes were detected using the Ventana OmniMap anti-Rabbit detection kit (760–4311) and developed using the Ventana ChromMap DAB detection kit (760–159) per to the manufacturer’s instructions. Slides were then counterstained with hematoxylin II (790–2208) for 8 min, followed by Bluing reagent (760–2037) for 4 min. The slides were then dehydrated with ethanol series, cleared in xylene, and mounted. As a negative control, the primary antibody was replaced with normal rabbit IgG to confirm absence of specific staining. Immunostained slides were scanned using a Leica Aperio ScanScope CS 5 slide scanner (Aperio, Vista, CA, USA). Scanned images were then viewed and captured with Leica Aperio’s image viewer software (ImageScope, version 11.1.2.760, Leica Aperio). The pMLKL signal was quantified using the Aperio Positive Pixel Count algorithm.

To examine IAV spread and pathology in murine pulmonary tissues, lungs were first inflated with 1 ml of 10% neutral-buffered formalin, removed, and placed in 15 ml conical tube containing 3 ml of formalin and incubated at room temperature for 24 h to ensure complete fixation. Then lungs were embedded in paraffin blocks and sectioned onto glass slides. These lung sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin for histological analyses. Immunohistochemical labelling of viral antigen was performed with goat polyclonal antibody to influenza A (1:1,000) and a secondary biotinylated donkey anti-goat antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology; 1:200) on tissue sections subjected to antigen retrieval for 30 min at 98°C. The extent of virus spread was quantified by first capturing digital images of whole-lung sections stained for viral antigen by using an Aperio ScanScope XT Slide Scanner (Aperio Technologies), then manually outlining fields with the alveolar areas containing virus antigen–positive pneumocytes highlighted in red (defined as “active” infection), whereas lesioned areas containing no antigen-positive cells and no/minimal antigen-positive debris were highlighted in yellow (defined as “inactive” infection). The percentage of each lung field with infection/lesion was calculated using the Aperio ImageScope software (version 12.3.3).

For the measure of extent of neutrophil infiltration, lungs were first embedded in paraffin, sectioned at 4 μm, mounted on positively charged glass slides (Superfrost Plus; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), and dried at 60°C for 20 min. For detection of neutrophils, antigen retrieval at 100°C for 20 min in Epitope Retrieval solution 2 (ER2) was performed on a Bond Max immunostainer (Leica Biosystems, Buffalo Grove, IL). A rat monoclonal primary antibody to Ly-6B.2 (1:30,000) was applied for 15 minutes followed by biotinylated secondary rabbit anti-rat antibody 1:400 (Vector Laboratories) for 10 minutes and then ready-to-use BOND DAB Enhancer (AR9432; Leica Biosystems) and a hematoxylin counterstain. Slides were scanned and digital whole lung images were evaluated using the DenseNet algorithm of the image analysis platform HALO (version 3.1; Albuquerque, NM). Alveoli in the lung images were classified as being either normal or infiltrated with neutrophil exudates and subjected to deep learning (DL) until convergence to a cross-entropy that was <0.1. Lungs were then analyzed by the trained model, and pathologists visually confirmed the results. In the cases in which the auto-recognized regions were misrecognized, the regions were corrected or appropriately annotated, and then the DL was repeated to construct the trained model for the automated recognition. To improve the recognition accuracy, the cycle was repeated until the number of misrecognized regions was reduced to an absolute minimum, or until the analysis results did not change even when further DL was performed. The fraction of lung volume that was occupied by neutrophil infiltrates was determined by quantitative morphometry using the HALO™ Area Quantification v2.1.11 algorithm (IndicaLabs, NM, USA).

For detection of Tenascin C, antigen retrieval at 100°C for 32 min was completed in Cell Conditioning 1 (CC1) buffer (Ventana Medical Systems, 950–500) on a Discovery Ultra immunostainer (Ventana Medical Systems). A rabbit monoclonal primary antibody to Tenascin C diluted at 1:100 (Abcam, ab108930) was applied for 32 min at 37°C. Secondary goat anti-rabbit polyclonal antibodies labeled with a proprietary hapten nitropyrazole (Ventana Medical Systems, 760–4311) were applied for 16 min at RT and then developed with ChromoMap DAB (3,3′-Diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride) chromogen, and then counterstained with hematoxylin (all from Ventana Medical Systems). The extent and severity of pulmonary inflammation were determined from sections examined in a blinded fashion by a pathologist and scored on a severity scale as follows: 0 = no lesions; 1 = minimal, focal to multifocal, barely detectable; 15 = mild, multifocal, small but conspicuous; 40 = moderate, multifocal, prominent; 80 = marked, multifocal coalescing, lobar; 100 = severe, diffuse, with extensive disruption of normal architecture and function. These scores were converted to a semiquantitative scale as described previously54.

Cytokine and chemokine assessment in BALF

For cytokine profile studies, BALF was collected using 1 ml of sterile phosphate-buffered saline (calcium-magnesium free). Concentrations of analytes were determined using the ProcartaPlex Mouse Immune Monitoring Panel 48-Plex kit (ThermoFisher, EPX480-20834-901). Briefly, samples were centrifuged at 1400 rpm for 10 min at 4°C. Prepared standards, high and low controls, diluent only controls, and clarified supernatants were added to plates containing capture beads, according to manufacturer’s instructions. Plates were shaken at 600 rpm overnight at 4°C, then warmed to room temperature for an additional 30 min with shaking. The remaining steps were performed according to manufacturer’s instructions. Plates were run on a Luminex 200 instrument (Luminex Corp), and data were analyzed using 5PL logistic fit in ProcartaPlex Analyst 1.0 software (ThermoFisher).

Pulse oximetry and lung function studies

For pulse oximetry studies, mice were infected with PR8 (4,500 EID50, i.n.). At day 3 and day 6 after infection, the fur around the neck of the mouse was removed and arterial oxygen saturation (SpO2) was measured with a throat collar sensor using the MouseOx system (STARR Life Sciences). To assess airway resistance, mice were infected with PR8 (2,500 EID50, i.n.). At day 10 post infection, a tracheal tube was inserted into anesthetized mice, and airway resistance was measured on a Buxco Finepointe Resistance and Compliance instrument. Data were collected using Buxco Finepointe software version 2.6 (Data Sciences International). Two methacholine challenges were performed at doses of 1.5625 and 3.125 mg/ml, administering the methacholine in 0.010 ml PBS. Following each methacholine challenge, airway resistance was measured for 3 min, allowing the mice to recover for 1 min after each measurement. Measurements for airway resistance were averaged over the 3 min measurement period for each methacholine challenge.

Statistics

Statistical significance was determined by use of multiple unpaired Student’s t tests or the Mann-Whitney U test for comparison between two groups, or one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test or the two-way ANOVA, for comparisons between multiple (>2) groups. Significance of in vivo survival data was determined by the log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. P-values of 0.05 or lower were considered significant. Graphs were generated using Graph Pad Prism 9.5.0 software.

Extended Data

Extended data Fig. 1. UH15-38 is a potent RIPK3 kinase inhibitor.

a, Immunoblot analysis of pMLKL and cleaved caspase 8 (CC8) in lysates obtained from Ripk3−/− MEFs stably expressing 2xFv-RIPK3 and treated with dimerizer (AP20187, 100 nM) in the presence of the pan-caspase inhibitor (IDN-6556, 20 μM) and UH15-38 (500 nM) for 12 h. b, Table comparing UH15-38 to GSK’872 in the indicated recombinant kinase assays. Kinase assays were performed using ADPGlo (Promega) and on the DiscoverX platform (Eurofins DiscoverX). ND = Not determined. c, Overview of docking of UH15-38 into human RIPK3. d, Docking of GSK’872 into mouse RIPK3. e, Docking of GSK’843 into mouse RIPK3. f, MEFs infected with PR8 (MOI =2) were treated with indicated drugs in the presence of zVAD (50 μM) and cell viability was determined after 24 h. g, Cell survival kinetics of iBMDMs treated with LPS (10 ng/ml) and TAK1 inhibitor 5z7 (200 nM) following exposure to the indicated concentrations of the RIPK3 inhibitors UH15-38 and GSK’872 or the RIPK1 inhibitor GSK’547 for 6 h. h, Ripk3+/+ and Ripk3−/− MEFs were treated with TNF/5z7/IDN6556 and TNF/5z7, respectively, in the presence of the indicated concentrations of UH15-38, and viability was determined after 24 h. Ripk3−/− MEFs treated with UH15-38 alone were used as controls. i, Viability of Ripk3−/− MEFs treated with TNF/5z7 in the presence of DMSO or GSK’547 (10 μM). j, Immunoblot analysis of Gasdermin D (GSDMD) cleavage in primary BMDMs pre-treated with LPS (10 ng/ml) for 3 h followed by Nigericin (10 μM) or ATP (5 mM), along with DMSO or UH15-38 (500 nM), for an additional 1 h. k, Viability of primary BMDMs pre-treated with LPS (10 ng/ml for 3 h) followed by treatment with Nigericin (10 μM) and the indicated concentrations of UH15-38 for 1 h. Viability was determined by using CellTiter-Glo assay (as in g, h, k) or Trypan Blue exclusion assay (as in f). Error bars represent mean ± SD (n=3). Data are from one of the at least two independent experiments. Groups were compared using ordinary one-way ANOVA (as in f, k) or the unpaired two-sided Student’s t test (as in i).

Extended Data Fig. 2. Pharmacological profiling of UH15-38.

a, Half-life (T1/2) and peak concentrations (Cmax) of UH15-38 in tissue samples collected from mice treated with four once-daily) doses of UH15-38 (30 mg/kg/day, i.p.). b, c, Immunofluorescence staining for phosphorylated-MLKL (pMLKL) (b) and quantification of pMLKL signal in lung, heart kidney and liver sections (c) obtained from Casp8−/−MlklFLAG/FLAG mice following i.p administration of either vehicle (n = 3 mice) or UH15-38 (30 mg/kg, once-daily, n = 4 mice) for four days. Six fields of each tissue section per mice were quantified. d, InVEST Safety Panel profile of UH15-38 showing percent inhibition of each target in the presence of 1 μM compound. e, f, Immunohistochemistry for cleaved caspase 3 (CC3) (e) and quantification of cleaved caspase 3 signal (f) in lung, heart, kidney and liver sections (n = 4 mice) following i.p. administration of either vehicle or UH15-38 (30 mg/kg, once-daily) for seven days. IAV PR8-infected lung tissue (n = 4 mice) is shown as positive control in e and f (green). Groups were compared using the two-sided Mann-Whitney U test.

Extended Data Fig. 3. UH15-38 is a potent and specific inhibitor of necroptosis in murine and human cells.