Abstract

Background

Deep brain stimulation (DBS) is an effective therapy for Parkinson’s disease (PD), but disparities exist in access to DBS along gender, racial, and socioeconomic lines.

Summary

Women are underrepresented in clinical trials and less likely to undergo DBS compared to their male counterparts. Racial and ethnic minorities are also less likely to undergo DBS procedures, even when controlling for disease severity and other demographic factors. These disparities can have significant impacts on patients’ access to care, quality of life, and ability to manage their debilitating movement disorders.

Key Messages

Addressing these disparities requires increasing patient awareness and education, minimizing barriers to equitable access, and implementing diversity and inclusion initiatives within the healthcare system. In this systematic review, we first review literature discussing gender, racial, and socioeconomic disparities in DBS access and then propose several patient, provider, community, and national-level interventions to improve DBS access for all populations.

Keywords: Deep brain stimulation, Disparities, Minorities, Socioeconomic status, Gender, Ethnicity

Introduction

Racial, socioeconomic, and gender disparities, leading to delays in diagnosis, treatment, and worsened overall survival have been demonstrated in patients with Parkinson’s disease (PD) [1]. DBS is an effective treatment option for advanced PD and is associated with improvement in motor symptom control and quality of life [2, 3]. Given that DBS candidacy is evaluated via a multidisciplinary team of neurologists, neuropsychologists, and neurosurgeons, there are several steps along the DBS approval process that may contribute to disparities in access and patient outcomes [4, 5]. These steps are also areas to target with interventions to reduce disparities. Previous studies have shown differences in patient access to DBS based on race, socioeconomic status, and gender [6–17].

Women are underrepresented in clinical trials [18] and are less likely than men to undergo to DBS. One study found that only 30% of PD patients treated with DBS are women [6], while women represent approximately 42% of patients with PD [19]. In the Medicare population, women with PD are 21% less likely to undergo DBS than men [13].

Racial and ethnic minority patients are also less likely to undergo DBS, even when controlling for disease severity and demographic factors. For example, various studies conducted in the USA found that black PD patients were less likely to receive DBS than white patients, after controlling for disease severity and healthcare access [13, 16]. Socioeconomic status has also been shown to impact access to DBS, with studies showing that patients from wealthier communities and with private insurance are more likely to receive DBS [6, 11–13].

Much current research focuses on identifying and, to a lesser extent, understanding the underlying causes that propagate DBS disparities; however, few studies discuss potential interventions aimed at mitigating these disparities [20]. Prior studies have argued that unconscious biases among healthcare providers, lack of patient awareness and understanding of treatment options, and limited resources may all contribute to inequities in access [7, 8, 21]. This review will examine disparities in access to DBS across race, gender, and socioeconomic status as well as provide an overview of possible provider, patient, community, and policy/organizational-level evidence-based interventions.

Methods

Search Criteria and Study Selection

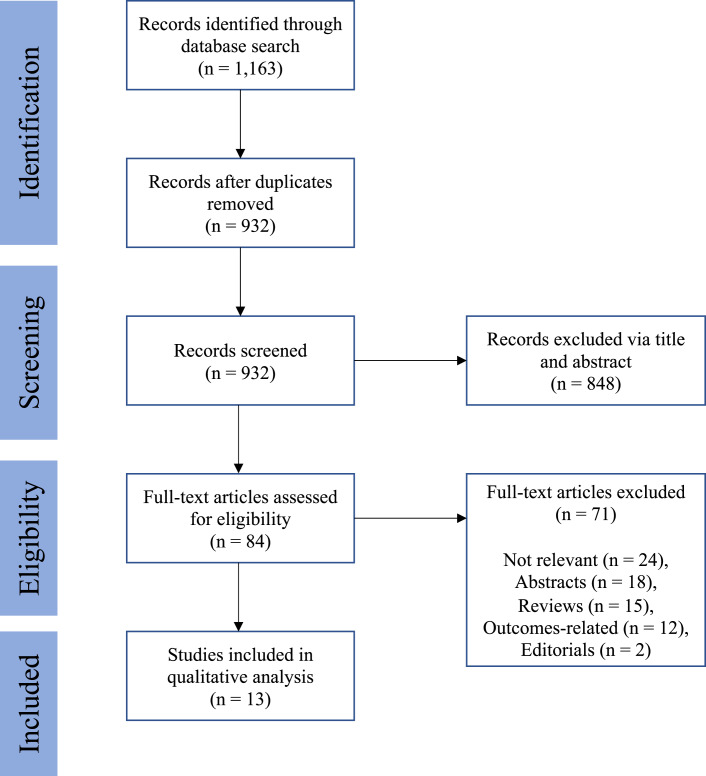

A literature review was performed to investigate disparities in access to DBS surgery. The search terms included (“deep brain stimulation” OR “DBS”) AND (“disparities” OR “inequality” OR “healthcare disparities” OR “racial disparities” OR “ethnic disparities” OR “socioeconomic disparities” OR “minority populations” OR “gender” OR “gender disparities”). Original studies that investigated any type of disparity relating to access to DBS from 1990 to present day were considered. Letters to the editor, commentaries, and articles of editorials were excluded from review. The search process included screening the title, abstract, and full-text article. Papers that did not specifically discuss disparities in access to DBS were excluded in the final qualitative analysis. Papers that discussed disparities in outcome were also excluded in the final analysis. Studies from all countries were considered, but an English version of the article was required for inclusion in the analysis. A flow diagram is provided in Figure 1.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram depicting identification and selection of papers describing disparities in access to DBS.

Results

Article Characteristics

Of the 1,162 initially screened studies, 13 met inclusion criteria (Fig. 1; Table 1) [6–17, 22], with publication years spanning 2014–2023. Studies originated from 5 different countries, with 8 (66.7%) from the USA. All studies performed a retrospective cohort analysis. The findings from these studies are synthesized and summarized below.

Table 1.

Study characteristics of included articles

| Author | Country | Number of DBS patients | Gender | Mean age, years | Most represented races | Disparity studied | Disparity observed | Proposed rationale |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shpiner et al. [6] 2019 | USA (FL) | 207 referred, 100 (48.3%) received surgery | Male: 75.8% | Male: 65.0 | Caucasian: 83% | Gender | Women are less likely to receive DBS due to preference | Decreased preoperative education for women |

| Female: 24.2% | Female: 65.3 | African American: 4.8% | ||||||

| Unknown: 4.8% | ||||||||

| Watanabe et al. [7] 2022 | USA (HI) | 74 | Male: 66.22% | N/A | White: 43.24% | AA and NHPI utilization of DBS | NHPI and black PD patients underrepresented. All NHPI receiving DBS were male | Lack of access to care in underserved minorities leading to earlier mortality |

| Female: 33.78% | AA: 45.95% | |||||||

| Jost et al. [8] 2022 | France | 316 referred | Male: 67% | Male: 62.0 | N/A | Gender | Fewer women underwent DBS assessment than expected, fewer referrals from physicians | Nonclinical factors such as referral biases, greater fear of surgery, or socioeconomic status |

| 190 (83.0%) received surgery | Female: 33% | Female: 62.7 | ||||||

| Dalrymple et al. [9] 2019 | USA (VA) | 137 | Male: 69.3% | Male: 63.3 | N/A | Gender | Women were less likely to receive DBS for medication refractory tremor | Male preference for surgery or clinician bias leading to fewer referrals for women |

| Female: 330.7% | Female: 63.3 | |||||||

| Crispo et al. [10] 2020 | Canada | 260 | Male: 74.6% | 64.4 | N/A | Age | Patients living in areas with a large minority population are less likely to receive DBS surgery | Differences in access to care, health-seeking behavior, or need for DBS |

| Female: 25.4% | ||||||||

| Chan et al. [11] 2014 | USA | 18,312 | Male: 67.53% | 63.66 | White: 85.71% | African American access to DBS | African Americans with PD are 8 times less likely to undergo DBS relative to white patients | Medicaid reliance amongst black patients, access to care, or cultural biases |

| Hispanic: 7.71% | ||||||||

| Female: 32.47% | Asian/PI: 2.50% | |||||||

| African American: 0.86% | ||||||||

| Skelton et al. [12] 2023 | USA (GA) | 209 referred | (Referrals) | 64.1 | (Referrals) | Utilization of DBS by black patients | Underutilization of DBS by black patients post-referral | Disparities occur in the time between medical management and surgical evaluation, driven by lack of patient follow-up |

| Male: 73.2% | White: 84.7% | |||||||

| Asian: 6.2% | ||||||||

| 171 (81.8%) received surgery | Female: 26.8% | Black: 4.8% | ||||||

| Hispanic: 4.3% | ||||||||

| Willis et al. [13] 2014 | USA | 8,420 | Male: 59.3% | Medicaid patients (>65) | White: 94.9% | Demographic, clinical, SES, and physician practice factors | Greatest disparities are associated with race: black and Asian patients were less likely to receive DBS than white patients. High neighborhood SES associated with greater odds of receiving DBS | Multidisciplinary care is not accessible in low-income areas. Lack of referrals in areas with a high minority population |

| Unknown: 0.12% | ||||||||

| Female: 40.7% | Hispanic: 1.7% | |||||||

| Black: 1.0% | ||||||||

| Vinke et al. [14] 2022 | Netherlands, Slovenia | 121 | Male: 64.5% | N/A | N/A | Gender | Women have a greater chance of undergoing DBS when an asleep MRI or CT guided method is available | Increased anxiety about surgery among women may make asleep operations more tolerable |

| Female: 35.5% | ||||||||

| Chandran et al. [15] 2014 | India | 51 | Male: 62.7% | Male: 55.8 | N/A | Gender | Women equally likely to undergo DBS | Financial considerations are main limitation for surgery in this population |

| Female: 37.3% | Female: 54.5 | |||||||

| Cramer et al. [16] 2022 | USA | 50,837 | Male: 68% | 64.3 | White: 84.9% | Race and SES | Black patients were 5 times less likely to undergo DBS than white patients. Female patients were also less likely to receive DBS than males | Systemic factors such as unconscious/conscious bias |

| Female: 32% | Other: 13.8% | |||||||

| Black: 1.3% | ||||||||

| Deuel et al. [22] 2023 | USA | 6,952 | Male: 69.5% | Male: 65.2 | N/A | Gender | Both national and local data were consistent with a gender disparity | Women with PD are more likely to live alone and more likely to have concerns over side effects |

| Female: 30.5% | Female: 65.5 | |||||||

| Sarica et al. [17] 2023 | Canada | 8,655 | Male: 69.5% | 65.1 | White: 85.0% | Gender | Female and black patients are less likely to undergo DBS. Increasing SES is a positive predictor for DBS use | Biases both at the initial screening stage and during the assessment for surgery |

| Hispanic: 6.8% | ||||||||

| African: 1.8% | Race | |||||||

| Female: 30.5% | Asian: 2.6% | |||||||

| Native American: 0.4% | SES | |||||||

| Other: 3.4% |

Gender Disparities

There has been increased recognition of gender disparities in access to services across medical fields [23–25], and such disparities are also seen in neurosurgery. Gender disparities are also present in DBS: among Medicare beneficiaries, women with PD are 21% less likely than men to receive DBS, even after adjusting for age, race, socioeconomic status, disease duration, and comorbidities [13]. Factors at multiple points in the DBS evaluation process may contribute to this disparity; we separately consider both disparities in DBS referrals and in DBS utilization after referral [8].

Gender Disparities in DBS Referrals

Women are overall less likely to be referred for a DBS candidacy evaluation and have been found to experience a delay both from symptom onset to diagnosis and from diagnosis to referral [26]. One study found that of the PD patients seen in an American neurologic clinic population, a smaller proportion of total female compared to male patients with PD were referred for DBS consideration [6]. Once referred, male and female patients were equally likely to be offered surgery [6]. Similarly, a retrospective analysis at a German university hospital found that women were underrepresented in the population referred for DBS but had a higher probability of approval for DBS after multidisciplinary evaluation (relative risk 1.17) [8]. The authors noted several nonclinical factors that may contribute to the observed gender disparities, including referral biases to specialty care [27, 28], greater fear of surgery [29], or socioeconomic status [28]. One study found that women with PD were 22% less likely to see a neurologist compared to men [30]. Given that most referrals to DBS come from neurologists [31], lower likelihood of seeing a neurologist may contribute to a smaller number of women being referred for surgical consideration.

Notably, some studies have suggested that women may have slower PD symptom progression [32, 33], which could affect identification of women as candidates for DBS. However, women are still underrepresented in DBS surgeries for essential tremor, a disease in which gender-specific symptom differences have not been found [17]. This suggests that differences in symptom progression are not the major factor contributing to gender-related DBS disparities. Additionally, women continue to be underrepresented in PD clinical trials [18], limiting our understanding of PD manifestations and treatment in this population – another manifestation of this disparity.

Gender Disparities in DBS Utilization after Referral

In addition to disparities impacting referral for DBS surgery, there are gender disparities impacting DBS utilization after referral. Several studies have found that in patients referred for and offered DBS surgery, women are more likely than men to decline surgery [6, 8]. Previous studies have shown that women tend to be more concerned about possible complications of a surgery [6, 34]. One study reported gender differences in the reasons that patients referred for DBS ultimately did not undergo surgery, with women being more likely not to undergo surgery due to personal preference [6]. Women may also be more likely to have caregiving responsibilities or other social or economic contributing factors which may impact their decision to undergo DBS.

Racial Disparities

Presence of Racial Disparities in DBS Access

Racial disparities in access to neurosurgical procedures are a pervasive problem that has been increasingly recognized [35, 36]. In the USA, black PD patients are 5–8 times less likely to undergo DBS than white patients [11, 13]. Black race predicts decreased DBS use even when adjusting for comorbidities [8]. Asian patients also have lower odds ratios of having DBS compared to white patients (adjusted odds ratio of 0.55) [13]. Even when receiving care at urban teaching hospitals with a high density of neurologists and neurosurgeons, black patients with PD undergo disproportionately fewer DBS procedures [8]. This disparity has persisted over time: Cramer et al. [16] examined DBS use before and after 2010 and found that while the total number of DBS surgeries increased, racial disparities remained unchanged.

One study found that there was no difference in DBS use between white and Hispanic Medicare beneficiaries after adjusting for confounders [13]. On the other hand, Hispanic patients with PD were found in a separate study to be less likely to undergo DBS when controlling for patient and hospital characteristics [37]. Given that Hispanic patients are also underrepresented in other neurosurgical procedures such as spine surgery [38], this is an area important for future study.

Factors Contributing to Racial Disparities in DBS Access

A number of structural, social, and economic factors impact access to care, which may contribute to racial disparities in DBS access. Previous studies have found racial disparities in access to PD management, which inherently limits evaluation of patients for DBS. Minority populations are less likely to have access to both general and specialized movement disorder neurologists [39, 40]. One study examined all PD-related admissions in Hawaii and found that Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander (NHPI) and black patients were underrepresented with odds ratios of 0.64 and 0.17, respectively [7], suggesting racial disparities in access to PD care are not limited to DBS. The study notes that NHPI individuals have higher rates of poverty and lack of health insurance which may impact their ability to access PD care [7].

In addition to racial disparities in PD medical management, there are disparities in referral for surgical consideration. Skelton et al. [12] reported that the ratio of black to white medically managed PD patients was 0.38, while that of surgically managed patients was 0.07, with disparities in medical management accounting for only 14% of the overall surgical disparity, suggesting that events between medical management and surgery also contribute to disparities in access [12]. In this study, far fewer black patients were referred for DBS consideration than would be expected based on regional demographics, and once referred, there was no racial difference in the proportion of patients who proceeded to surgery, suggesting that disparities in DBS referrals may be a major contributor to ultimate disparities in DBS utilization [12]. This pattern suggests potential provider bias, as previous studies have provided evidence against comorbidities [11, 16, 38] or initial disease presentation [16] exacerbating referral disparities. In addition, prior studies have presented evidence to suggest black patients experience discrimination to a greater extent than do other minority populations [41–43]. These findings emphasize the need to address disparities in access to DBS by not only addressing access to general PD care but also by increasing referrals for surgical evaluation, especially among underserved populations.

Other factors including disease, cultural, and social factors may impact racial disparities in DBS use. Some minority populations may have differences in PD progression [44, 45]; black patients with PD have been reported to have higher rates of postural instability on initial evaluation, which could impact the way in which their DBS candidacy is judged [41]. However, a more recent study showed evidence to support that the extent of disease severity on initial presentation does not account for the extent of racial disparity [13]. Indeed, disparities in access to DBS have also been observed outside of PD, such as ET and dystonia [17, 37]. Cultural differences may also impact the way in which patients interpret their symptoms [42] which could ultimately impact patients’ likelihood of presenting for evaluation and treatment. Patient-specific factors, such as underreporting of motor impairment and mistrust of the medical system due to longstanding disparities in care, may contribute to the racial disparity in DBS use [43, 46–48]. Delay in diagnosis and treatment in minority populations is a broad issue stemming from a variety of structural factors including lack of access to healthcare and disparities in healthcare quality and may impact likelihood of DBS referral [49].

Socioeconomic Disparities

Socioeconomic status also impacts access to DBS. Patients who live in neighborhoods with the highest median income, educational achievement, and housing values are more likely to receive DBS [13, 16]. Similarly, Sarica et al. [17] found that increasing median household income within a given zip code was a positive predictor for DBS use in PD patients. Insurance status is a significant contributor to socioeconomic disparities in DBS access. Patients with private insurance have better access to primary care, which may impact their likelihood of referral to specialty treatment and increase their access to advanced treatment options such as DBS [50, 51]. Several studies have found that patients with private insurance are more likely to undergo DBS, while patients with Medicaid are less likely to undergo DBS [11, 12]. Practitioner avoidance of increased administrative burdens and low monetary reimbursement from government-funded insurance may contribute to decreased DBS use among those relying on Medicaid insurance [52]. Overall, these studies suggest that there are socioeconomic disparities in access and response to DBS therapy, highlighting the need to examine and address the potential underlying causes.

Interaction between Race and Socioeconomic Status

Socioeconomic and racial disparities in access to DBS may interact. Neighborhood and settings of care are linked to socioeconomic status and race, which can ultimately influence access to DBS care. One study found that practices with a large proportion of racial minority patients have fewer patients who ultimately receive DBS [13], and this effect was seen regardless of the race of the individual patients, suggesting that the environment of care may contribute to disparities in access. Similarly, individuals living in neighborhoods with higher concentrations of recent immigrants and visible minorities were found to be less likely to receive DBS surgery [10]. Watanabe et al. [7] reported that Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander patients who underwent DBS surgery were on average in higher income brackets than Asian and white DBS patients. Chan et al. [11] found that the impact of having Medicaid on likelihood of receiving DBS is modulated by race. White patients using Medicaid are significantly more likely to receive DBS than black patients using either private insurance or Medicare, and black patients with Medicaid are the least likely to receive DBS of any other group combination of race/ethnicity and insurance status [11]. Combined, these findings suggest that socioeconomic status and racial disparities interact in affecting patient access to care.

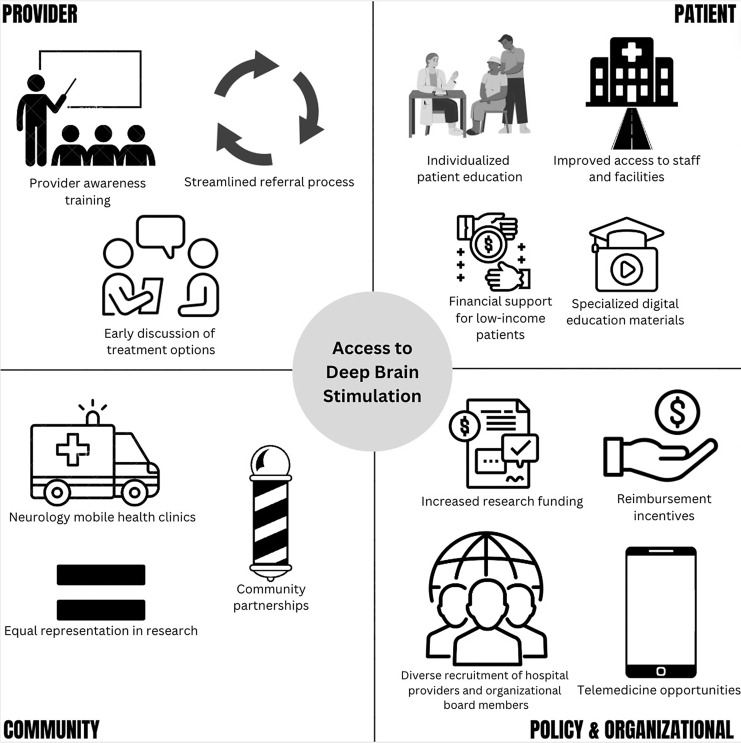

Proposed Interventions

In 2003, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) released a report to assess the extent and various causes of disparities in healthcare as well as suggest interventions to address these disparities [53]. Nonetheless, the vast majority of research on disparities within neurosurgery is still focused on the identification of disparities associated with treatment of neurosurgical diseases. A 2023 review investigating the current state of racial disparities literature within neurosurgical patients found that only 15.1% and 1.3% of the literature were devoted to understanding the root causes and proposing solutions, respectively, highlighting the importance of continued research [54]. We therefore propose provider, patient, community, and policy and organizational interventions aimed at addressing disparities in access to DBS as a treatment for advanced PD.

Provider-Level Interventions

Numerous systematic reviews have demonstrated not only the prevalence of racial and gender biases among providers but also how these biases are associated with worsened patient outcomes [55–57]. Research has suggested that diverse representation in the healthcare workforce may reduce bias, underscoring the importance of increasing diversity in neurosurgery to improve patient access [58]. Additionally, evidence across fields suggests that implementation of scientifically validated cultural competency training improves providers’ skills in providing culturally competent care, as well as patient satisfaction and follow-up [59–61]. Continued efforts should be made to provide clinicians with education regarding disparities in healthcare, strategies to recognize and overcome biases, as well as approaches to communicate treatment options to patients in an equitable manner [62, 63].

Most currently available diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) educational materials cover broad topics encompassing all of medicine [64]. There may be an opportunity to enhance effectiveness and applicability of the material by focusing on specific disparities in medicine, such as disparities in procedures. For example, integrating information about disparities in access to DBS into continued medical education modules for physicians, particularly in primary care and neurology, could be an impactful approach to raise awareness and communicate directly with the individuals capable of making actionable change. There is some evidence to suggest that integration of DEI training into continued medical education modules may improve provider skills in providing culturally competent services and patient satisfaction [65, 66]. Previous studies have also found that incorporating DEI material into graduate medical education was feasible and well received [67]. Co-engagement with providers may also involve establishing regular forums or workshops to discuss case studies and share insights on reducing disparities. Within a limited context such as large academic medical centers, showing providers how their referral rates compare to that of their colleagues may also mitigate disparities [68].

A personalized approach involving effective clinician-patient communication is essential to understanding patient perspectives that may serve as barriers to care. Prior literature suggests that making information more easily accessible to all patients [69, 70], providing decision-making support, and engaging in shared decision-making with patients and their families may reduce disparities [71]. Given disparities in patient access to specialized providers such as neurologists [30, 39, 40], additional education on DBS and its risks and benefits should be targeted toward general practitioners; prior literature evaluating primary care referrals to specialists across multiple medical specialties suggests providing education and structured referral guidelines for primary care providers improves referral patterns [72]. Ultimately, healthcare providers should work to ensure that all patients, regardless of race, gender, and socioeconomic status, are provided with information about advanced treatment options such as DBS in a timely, factual, and unbiased manner.

Patient-Level Interventions

Patient level interventions to reduce disparities in DBS access should include specialized educational materials. Poor health literacy is associated with lower rates of healthcare usage, leading to worse outcomes [73]. A systematic review found that approximately half of patients in the USA exhibit limited health literacy, with rates varying based on age, education, income, and race [74]. Surgical patients are considered a high-risk population due to the complexity of their pathologies and proposed interventions [75]. Numerous studies have shown that neurosurgical patients, particularly those from marginalized racial, gender, or socioeconomic groups, have a limited understanding of procedure-associated risks [76–78]. Furthermore, inequities in access to digital health technologies and low digital health literacy pose a unique challenge to PD patients as this disease impacts cognition and disproportionately affects the elderly [79]. Multiple studies have found that low digital literacy is a barrier to the use of digital health resources, particularly in underrepresented racial or socioeconomic groups [80, 81]. Providing accessible and easy to understand information in a variety of formats may help address some of the factors that are preventing patients from undergoing DBS and contributing to disparities in access to this therapy [82, 83].

Providing personalized education may also help reduce disparities in DBS access. One study found that educational material, including an informational video specially developed to address patient concerns about DBS, was effective in increasing the number of patients who decided to proceed with surgery evaluation and may improve the likelihood of women undergoing surgery [84]. Additionally, a randomized controlled trial found that using a three-dimensional brain model for education during DBS consultation significantly improved patient understanding of the procedure [85]. Importantly, educational materials should be created in an unbiased manner that uses language appropriate for the intended audience. In the first of a two-part systematic review of patient education in neurosurgery, Shlobin et al. [86] found that written materials and internet resources were often too advanced for the layperson to understand and may contain incomplete information due to financial conflicts of interest; the authors argue the importance of personalizing education to patient-specific needs and baseline knowledge levels using techniques such as reviewing imaging and providing relevant education resources. In the second systematic review, Shlobin et al. [87] aimed to understand characteristic features of effective neurosurgical patient education interventions; they recommend providing a variety of educational materials to reinforce concepts with an emphasis on the use of online resources such as video and three-dimensional models when appropriate. Previous studies evaluating the quality of neurosurgical videos posted on social media sites and YouTube found that a majority of videos contained advertisement biases, inaccurate information, and lacked references [88, 89]. There is evidence to suggest that high quality educational videos may be more effective than other mediums in reducing preoperative anxiety and increasing postoperative satisfaction, emphasizing the value of individualized digital education materials [90]. Additionally, increasing education and awareness regarding PD and its treatment options may encourage earlier diagnosis, more accurate reporting of symptoms, and greater trust in medical professionals [91, 92].

Better understanding gender and race-related differences in PD symptomatology, experience and expression of symptoms, and progression may also reduce disparities in patient evaluation and selection for DBS. Black patients have been found to underreport motor symptoms compared to white patients, leading to delays in diagnosis and treatment [93]. Women are more likely than men to be rejected for DBS due to depression [8]. To further illustrate the importance of addressing patient-specific concerns, after a center switched from awake microelectrode guided to asleep MRI-guided DBS placement, the percentage of women undergoing DBS increased to match the general PD population [14], suggesting that considering patient-specific concerns in approaches to surgery may help reduce disparities. Further research into DBS referral rates for different sexes and races as well as the frequency with which patients of different groups decide to undergo versus decline DBS is key to developing tailored treatment approaches that may help improve equity in treatment [94].

Community-Level Interventions

Community-level interventions have the opportunity to address disparities both in referral patterns and in post-referral DBS utilization. Efforts should be made to improve overall health outcomes in minority communities, such as increasing access to preventative care and addressing social determinants of health; doing so may also increase DBS candidacy in said communities’ PD patients. Prior literature in PD has revealed that implementation of a community-based dancing program improved PD symptoms in patients [95]. Community partnerships have also been used in other healthcare settings to accomplish a similar goal: partnerships with religious groups and barber shops have been shown to be effective in disseminating healthcare information to various communities and even facilitating referrals [96–98]. Such programs have been successfully implemented for diseases like SARS-CoV-2 and human immunodeficiency virus as well as for general health screening [96–98]. Similar coalitions could be made with elderly communities and their families to improve community and individual-level awareness of PD and DBS and also help facilitate neurologist referrals.

In the field of pediatric neurosurgery, the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) has funded studies in collaboration with the Bobby Jones Chiari and Syringomyelia Foundation [99], the Hydrocephalus Association [100], and the Lennox-Gastaut Syndrome Foundation [101]. These partnerships provide clinicians with invaluable insight into specific challenges that their patient populations face, paving the way for more targeted and efficacious interventions [102]. This community-engaged research framework has been employed by the Parkinson’s foundation to assess patient engagement in research, which may ultimately help more effectively capture the needs of the community and address factors that contribute to disparities [103]. This community-engaged research framework, with its focus on understanding patient needs and disparities, could be used to inform the development and implementation of DBS interventions tailored to address the specific challenges faced by diverse patient populations.

Interventions specific to PD and DBS could include programs providing support aimed at increasing access to specialists, such as movement disorder neurologists, in minority communities which may help address disparities in DBS referral patterns. In particular, mobile clinics have been shown to increase minority population access to care and improve outcomes in other specialties [104, 105]. Importantly, more than half of the patients that visit mobile health clinics are women or racial/ethnic minorities [104]. Therefore, a neurology mobile clinic could be used in initial PD evaluation prior to DBS referral and may be particularly useful for those patient populations who are affected by disparities in access to DBS. Combined, community-based interventions such as mobile clinics, direct community partnerships, as well as community wellness and exercise initiatives may all serve as methods to reduce disparities in DBS utilization as well as in medical care for PD.

Policy and Organizational Interventions

Many disparities stem from broad sources requiring organizational or national-level changes for more widespread improvement to occur [106]. First, increased support for research on disparities in DBS access is necessary to identify root causes and evaluate potential interventions. Socioeconomic and cultural factors contributing to healthcare disparities have been previously addressed at a policy and organizational level by implementing policies and programs that promote equity in opportunities, access to economic resources, and overall health [107], as well as providing education and support to address cultural barriers to care [108]. Similar approaches may help reduce disparities in accessing DBS treatment. Additionally, we propose that increased representation of diverse individuals in the membership and leadership of neurology and neurosurgery societies and publication of guidelines addressing disparities in care may be instrumental in instigating change. Notably, organizational and policy adaptations should increase diversity not just of committees within national and international societies but also of PD and DBS providers. There are significant gender and racial disparities within the fields of both academic neurology [109, 110] and academic neurosurgery [111], with these disparities especially pronounced in neurosurgery. Previously proposed organizational interventions to increase diverse representation include targeted effort toward recruitment of racial minorities to neurosurgery and in leadership positions [112], enforcement of parental leave policies [112], and compensation equity [113]. Within academic institutions, efforts such as embracing holistic admissions approaches, leveraging social media platforms for tailored outreach to underrepresented ethnic and racial groups, and integrating diversity tracking tools such as a diversity dashboard have demonstrated effectiveness in improving diverse representation [114]. Given that there is evidence that nonwhite physicians disproportionately care for racial minority patients [115], it is critical to recruit women and racial minority physicians to specialty fields such as neurology and neurosurgery as this could help improve access to neurological and neurosurgical care such as DBS for minority populations.

Telemedicine may be another cost-effective organizational method to expand access to care for those living in distant or underserved areas. While it has been used in many specialties [116, 117], telemedicine alone may still be affected by disparities in access to and comfort with technology [118]. Additionally, streamlining the referral process and providing support for presurgical evaluations has been shown to help reduce the burden on referring physicians and encourage more referrals for DBS evaluations [72, 119, 120]. Effectively addressing disparities in DBS will also require increasing access to interpreter services [121], providing patient education materials in multiple languages, increasing social worker and case manager involvement in perioperative DBS care, and implementing policies to reduce bias and ensure equitable access to care [118]. Efforts to have diverse representation in marketing materials and to target underrepresented minorities may also help improve awareness of and access to DBS, as differences in exposure to direct-to-consumer marketing in healthcare between races have been previously observed [122, 123].

Finally, changes in reimbursement policies could help improve access to DBS. Research in otolaryngology has suggested that providers may avoid government-funded insurance due to lower reimbursement and increased administrative burden [52]. Given that Medicaid is independently associated with decreased DBS use [11], improved Medicaid reimbursement may effectively encourage more neurological and neurosurgical providers to accept Medicaid and improve access to specialized care in underserved communities [124–126]. Additionally, although most insurances cover DBS for PD, the development of nationally accepted candidacy criteria for DBS may increase the equity of insurance coverage, particularly for lower income patients.

The aforementioned disparities and proposed solutions are summarized in Tables 2 and 3, respectively. Solutions are also graphically presented in Figure 2.

Table 2.

Summary of disparities in access to DBS

| General disparities in DBS | Source of disparities in DBS |

|---|---|

| Gender disparities | Provider biases decrease female referrals |

| Differences on when treatments options are discussed with female patients | |

| Potential differences in risk aversiveness | |

| Women having difficulty foregoing caregiver roles | |

| Differences affecting disease onset and progression | |

| Underrepresentation in clinical trials | |

| Racial disparities | Decreased access to medical care |

| Decreased access to specialty care such as neurologists | |

| Disparities in referrals for DBS | |

| Delayed diagnosis | |

| Lack of marketing toward minority populations | |

| Cultural factors | |

| Systemic disparities leading to mistrust of the medical system | |

| Differences affecting disease onset and progression | |

| Socioeconomic disparities | Limited access to specialists |

| Differences in insurance coverage |

Table 3.

Proposed interventions to decrease disparities in DBS

| Level of intervention | Proposed interventions |

|---|---|

| Provider level | Implement provider and leadership training to increase awareness of implicit and explicit biases |

| Specialized training in cultural competency and DEI | |

| Diverse representation among healthcare providers caring for PD patients | |

| Increase provider awareness of existing disparities to increase referral rates | |

| Introducing DBS treatment to all patients early in the decision-making process | |

| DBS education and structured referral guidelines for primary care providers and neurologists | |

| Patient level | Accessible educational materials |

| Individualized patient education | |

| Specialized digital educational materials | |

| Increase education among minority communities about PD and treatment options | |

| Increase understanding of differences in Parkinson’s symptom expression and experience | |

| Community level | Improve access to preventive care in minority communities |

| Implement community-based social or physical health programs | |

| Increase access to movement disorder neurologists in minority communities, ex through mobile clinics | |

| Implementation of community partnerships (i.e., with religious groups or barbershops) | |

| National-level interventions | Increase research into causes of and solutions for disparities in DBS access |

| Inclusion of a greater diversity of individuals in leadership of national organizations, as well as healthcare providers | |

| Development of official guidelines for reducing disparities in DBS access | |

| Increase telemedicine opportunities to those in underserved locations | |

| Streamlined referral process | |

| Increased diversity in targeted advertising | |

| Change reimbursement policies |

Fig. 2.

Proposed solutions for disparities in access to DBS.

Conclusion

Gender, racial, and socioeconomic disparities can all contribute to unequal access to DBS treatment. Factors that contribute to these disparities are diverse and include factors impacting access to care, disparities in referrals to surgical providers, social and cultural factors, and financial limitations. Interventions on a provider, patient, community, and policy level are necessary to overcome these disparities. Ongoing research is important to quantify and raise awareness of disparities, while providing a foundation to develop tailored approaches to reduce them.

Statement of Ethics

An ethics statement is not applicable because this study is based exclusively on published literature.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Sources

This study was not supported by any sponsor or funder.

Author Contributions

Data acquisition: A.E.B., S.B., A.T.L., and M.N.M.; interpretation of data: A.E.B., N.C.H., M.Z., D.L.P., S.B., and A.T.L.; writing – original draft: A.E.B., N.C.H., M.Z., D.L.P., S.B., A.T.L., and M.N.M.; revising – original draft: A.E.B., T.J.B., D.J.E., and S.K.B.; revisions: A.E.B., N.C.H., M.Z., and S.K.B.; study design and conception: A.E.B., D.J.E., and S.K.B. All authors approved the final version of this manuscript and are accountable for all aspect of the work.

Funding Statement

This study was not supported by any sponsor or funder.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

References

- 1. Dahodwala N, Xie M, Noll E, Siderowf A, Mandell DS. Treatment disparities in Parkinson’s disease. Ann Neurol. 2009;66(2):142–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hitti FL, Ramayya AG, McShane BJ, Yang AI, Vaughan KA, Baltuch GH. Long-term outcomes following deep brain stimulation for Parkinson’s disease. J Neurosurg. 2019:1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lozano AM, Lipsman N, Bergman H, Brown P, Chabardes S, Chang JW, et al. Deep brain stimulation: current challenges and future directions. Nat Rev Neurol. 2019;15(3):148–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Defer GL, Widner H, Marié RM, Rémy P, Levivier M. Core assessment program for surgical interventional therapies in Parkinson’s disease (CAPSIT-PD). Mov Disord. 1999;14(4):572–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Artusi CA, Lopiano L, Morgante F. Deep brain stimulation selection criteria for Parkinson’s disease: time to go beyond CAPSIT-PD. J Clin Med. 2020;9(12):3931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Shpiner DS, Di Luca DG, Cajigas I, Diaz JS, Margolesky J, Moore H, et al. Gender disparities in deep brain stimulation for Parkinson’s disease. Neuromodulation J Int Neuromodulation Soc. 2019;22(4):484–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Watanabe G, Morden FTC, Gao F, Morita M, Bruno MK. Utilization and gender disparities of deep brain stimulation surgery amongst asian Americans, native hawaiians, and other pacific islanders with Parkinson’s disease in Hawai`i. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2022;222:107466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jost ST, Strobel L, Rizos A, Loehrer PA, Ashkan K, Evans J, et al. Gender gap in deep brain stimulation for Parkinson’s disease. NPJ Park Dis. 2022;8(1):47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dalrymple WA, Pusso A, Sperling SA, Flanigan JL, Huss DS, Harrison MB, et al. Comparison of Parkinson’s disease patients’ characteristics by indication for deep brain stimulation: men are more likely to have DBS for tremor. Tremor Other Hyperkinet Mov. 2019;9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Crispo JAG, Lam M, Le B, Richard L, Shariff SZ, Ansell DR, et al. Disparities in deep brain stimulation use for Parkinson’s disease in ontario, Canada. Can J Neurol Sci. 2020;47(5):642–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chan AK, McGovern RA, Brown LT, Sheehy JP, Zacharia BE, Mikell CB, et al. Disparities in access to deep brain stimulation surgery for Parkinson disease: interaction between African American race and Medicaid use. JAMA Neurol. 2014;71(3):291–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Skelton HM, Grogan DP, Laxpati NG, Miocinovic S, Gross RE, Yong NA. Identifying the sources of racial disparity in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease with deep brain stimulation. Neurosurgery. 2023;92(6):1163–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Willis AW, Schootman M, Kung N, Wang XY, Perlmutter JS, Racette BA. Disparities in deep brain stimulation surgery among insured elders with Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2014;82(2):163–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Vinke RS, Georgiev D, Selvaraj AK, Rahimi T, Bloem BR, Bartels RHMA, et al. Gender distribution in deep brain stimulation for Parkinson’s disease: the effect of awake versus asleep surgery. J Park Dis. 2022;12(6):1965–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chandran S, Krishnan S, Rao RM, Sarma SG, Sarma PS, Kishore A. Gender influence on selection and outcome of deep brain stimulation for Parkinson’s disease. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2014;17(1):66–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cramer SW, Do TH, Palzer EF, Naik A, Rice AL, Novy SG, et al. Persistent racial disparities in deep brain stimulation for Parkinson’s disease. Ann Neurol. 2022;92(2):246–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sarica C, Conner CR, Yamamoto K, Yang A, Germann J, Lannon MM, et al. Trends and disparities in deep brain stimulation utilization in the United States: a Nationwide Inpatient Sample analysis from 1993 to 2017. Lancet Reg Health Am. 2023;26:100599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tosserams A, Araújo R, Pringsheim T, Post B, Darweesh SKL, IntHout J, et al. Underrepresentation of women in Parkinson’s disease trials. Mov Disord. 2018;33(11):1825–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Willis AW, Roberts E, Beck JC, Fiske B, Ross W, Savica R, et al. Incidence of Parkinson disease in north America. NPJ Park Dis. 2022;8(1):170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Memon AA, Gelman K, Melott J, Billings R, Fullard M, Catiul C, et al. A systematic review of health disparities research in deep brain stimulation surgery for Parkinson’s disease. Front Hum Neurosci. 2023;17:1269401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Xie T, Liao C, Lee D, Yu H, Padmanaban M, Kang W, et al. Disparities in diagnosis, treatment and survival between Black and White Parkinson patients. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2021;87:7–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Deuel LM, Peterson R, Sillau S, Willis AW, Yu C, Kern DS, et al. Gender disparities in deep brain stimulation surgery for Parkinson disease and essential tremor. Deep Brain Stimul. 2023;1:26–33. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kent JA, Patel V, Varela NA. Gender disparities in health care. Mount Sinai J Med. 2012;79(5):555–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Manuel JI. Racial/ethnic and gender disparities in health care use and access. Health Serv Res. 2018;53(3):1407–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Socías ME, Koehoorn M, Shoveller J. Gender inequalities in access to health care among adults living in British columbia, Canada. Wom Health Issues. 2016;26(1):74–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Saunders-Pullman R, Wang C, Stanley K, Bressman SB. Diagnosis and referral delay in women with Parkinson’s disease. Gend Med. 2011;8(3):209–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Feldman DE, Huynh T, Des Lauriers J, Giannetti N, Frenette M, Grondin F, et al. Gender and other disparities in referral to specialized heart failure clinics following emergency department visits. J Womens Health. 2013;22(6):526–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bhave PD, Lu X, Girotra S, Kamel H, Vaughan Sarrazin MS. Race- and sex-related differences in care for patients newly diagnosed with atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm. 2015;12(7):1406–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Setiawan M, Kraft S, Doig K, Hunka K, Haffenden A, Trew M, et al. Referrals for movement disorder surgery: under-representation of females and reasons for refusal. Can J Neurol Sci. 2006;33(1):53–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Willis AW, Schootman M, Evanoff BA, Perlmutter JS, Racette BA. Neurologist care in Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2011;77(9):851–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Katz M, Kilbane C, Rosengard J, Alterman RL, Tagliati M. Referring patients for deep brain stimulation: an improving practice. Arch Neurol. 2011;68(8):1027–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Iwaki H, Blauwendraat C, Leonard HL, Makarious MB, Kim JJ, Liu G, et al. Differences in the presentation and progression of Parkinson’s disease by sex. Mov Disord. 2021;36(1):106–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Haaxma CA, Bloem BR, Borm GF, Oyen WJG, Leenders KL, Eshuis S, et al. Gender differences in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007;78(8):819–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hamberg K, Hariz GM. The decision-making process leading to deep brain stimulation in men and women with Parkinson’s disease - an interview study. BMC Neurol. 2014;14:89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rinaldo L, Rabinstein AA, Cloft HJ, Knudsen JM, Lanzino G, Rangel Castilla L, et al. Racial and economic disparities in the access to treatment of unruptured intracranial aneurysms are persistent problems. J Neurointerv Surg. 2019;11(8):833–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sharma K, Kalakoti P, Henry M, Mishra V, Riel-Romero RM, Notarianni C, et al. Revisiting racial disparities in access to surgical management of drug-resistant temporal lobe epilepsy post implementation of Affordable Care Act. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2017;158:82–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Dorritie A, Faysel M, Gruessner A, Robakis D. Black and hispanic patients with movement disorders less likely to undergo deep brain stimulation. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2023;115:105811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Best MJ, McFarland EG, Thakkar SC, Srikumaran U. Racial disparities in the use of surgical procedures in the US. JAMA Surg. 2021;156(3):274–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Saadi A, Himmelstein DU, Woolhandler S, Mejia NI. Racial disparities in neurologic health care access and utilization in the United States. Neurology. 2017;88(24):2268–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Robbins NM, Charleston L 4th, Saadi A, Thayer Z, Codrington WU 3rd, Landry A, et al. Black patients matter in neurology: race, racism, and race-based neurodisparities. Neurology. 2022;99(3):106–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Palakurthi B, Burugupally SP. Postural instability in Parkinson’s disease: a review. Brain Sci. 2019;9(9):239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Pan S, Stutzbach J, Reichwein S, Lee BK, Dahodwala N. Knowledge and attitudes about Parkinson’s disease among a diverse group of older adults. J Cross Cult Gerontol. 2014;29(3):339–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Dahodwala N, Karlawish J, Siderowf A, Duda JE, Mandell DS. Delayed Parkinson’s disease diagnosis among African-Americans: the role of reporting of disability. Neuroepidemiology. 2011;36(3):150–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Aasly JO. Long-Term outcomes of genetic Parkinson’s disease. J Mov Disord. 2020;13(2):81–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ben-Joseph A, Marshall CR, Lees AJ, Noyce AJ. Ethnic variation in the manifestation of Parkinson’s disease: a narrative review. J Park Dis. 2020;10(1):31–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Breen DP, Evans JR, Farrell K, Brayne C, Barker RA. Determinants of delayed diagnosis in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol. 2013;260(8):1978–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Powell W, Richmond J, Mohottige D, Yen I, Joslyn A, Corbie-Smith G. Medical mistrust, racism, and delays in preventive health screening among african-American men. Behav Med. 2019;45(2):102–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Bazargan M, Cobb S, Assari S. Discrimination and medical mistrust in a racially and ethnically diverse sample of California adults. Ann Fam Med. 2021;19(1):4–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Riley WJ. Health disparities: gaps in access, quality and affordability of medical care. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 2012;123:167–74. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Wray CM, Khare M, Keyhani S. Access to care, cost of care, and satisfaction with care among adults with private and public health insurance in the US. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(6):e2110275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Hsiang WR, Lukasiewicz A, Gentry M, Kim CY, Leslie MP, Pelker R, et al. Medicaid patients have greater difficulty scheduling health care appointments compared with private insurance patients: a meta-analysis. Inquiry. 2019;56:46958019838118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Wang EC, Choe MC, Meara JG, Koempel JA. Inequality of access to surgical specialty health care: why children with government-funded insurance have less access than those with private insurance in Southern California. Pediatrics. 2004;114(5):e584–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care; Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR. Executive summary. In: Unequal treatment: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. National Academies Press (US); 2003. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK220355/ (Accessed Nov 30 2023). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Owolo E, Seas A, Bishop B, Sperber J, Petitt Z, Arango A, et al. Scoping review on the state of racial disparities literature in the treatment of neurosurgical disease: a call for action. Neurosurg Focus. 2023;55(5):E3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Hall WJ, Chapman MV, Lee KM, Merino YM, Thomas TW, Payne BK, et al. Implicit racial/ethnic bias among health care professionals and its influence on health care outcomes: a systematic review. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(12):e60–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. FitzGerald C, Hurst S. Implicit bias in healthcare professionals: a systematic review. BMC Med Ethics. 2017;18(1):19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Maina IW, Belton TD, Ginzberg S, Singh A, Johnson TJ. A decade of studying implicit racial/ethnic bias in healthcare providers using the implicit association test. Soc Sci Med. 2018;199:219–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Cohen JJ, Gabriel BA, Terrell C. The case for diversity in the health care workforce. Health Aff. 2002;21(5):90–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Beach MC, Cooper LA, Robinson KA, Price EG, Gary TL, Jenckes MW, et al. Strategies for improving minority healthcare quality: summary. In: AHRQ evidence report summaries. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2004. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK11918/ (Accessed Feb 10, 2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Cox WTL. Developing scientifically validated bias and diversity trainings that work: empowering agents of change to reduce bias, create inclusion, and promote equity. Manag Decis. 2023;61(4):1038–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Luaces MA, Galliart JM, Mabachi NM, Zackula R, Binion D, McGee J. Lessons learned from implementing unconscious bias training at an academic medical center. Kans J Med. 2022;15:336–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Nelson SC, Prasad S, Hackman HW. Training providers on issues of race and racism improve health care equity. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62(5):915–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Jacobs EA, Kohrman C, Lemon M, Vickers DL. Teaching physicians-in-training to address racial disparities in health: a hospital-community partnership. Public Health Rep. 2003;118(4):349–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Boatright D, London M, Soriano AJ, Westervelt M, Sanchez S, Gonzalo JD, et al. Strategies and best practices to improve diversity, equity, and inclusion among US graduate medical education programs. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(2):e2255110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Like RC. Educating clinicians about cultural competence and disparities in health and health care. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2011;31(3):196–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Gisondi MA, Keyes T, Zucker S, Bumgardner D. Teaching LGBTQ+ health, a web-based faculty development course: program evaluation study using the RE-AIM framework. JMIR Med Educ. 2023;9:e47777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Chung AS, Cardell A, Desai S, Porter E, Ghei R, Akinlosotu J, et al. Educational outcomes of diversity curricula in graduate medical education. J Grad Med Educ. 2023;15(2):152–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Ivers N, Jamtvedt G, Flottorp S, Young JM, Odgaard-Jensen J, French SD, et al. Audit and feedback: effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012(6):CD000259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Lorence DP, Park H, Fox S. Racial disparities in health information access: resilience of the Digital Divide. J Med Syst. 2006;30(4):241–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Dolcini MM, Canchola JA, Catania JA, Song Mayeda MM, Dietz EL, Cotto-Negrón C, et al. National-level disparities in internet access among low-income and black and hispanic youth: current population survey. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(10):e27723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Peek ME, Odoms-Young A, Quinn MT, Gorawara-Bhat R, Wilson SC, Chin MH. Race and shared decision-making: perspectives of African-Americans with diabetes. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71(1):1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Akbari A, Mayhew A, Al-Alawi MA, Grimshaw J, Winkens R, Glidewell E, et al. Interventions to improve outpatient referrals from primary care to secondary care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;2008(4):CD005471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Berkman ND, Sheridan SL, Donahue KE, Halpern DJ, Crotty K. Low health literacy and health outcomes: an updated systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(2):97–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Paasche-Orlow MK, Parker RM, Gazmararian JA, Nielsen-Bohlman LT, Rudd RR. The prevalence of limited health literacy. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(2):175–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Roy M, Corkum JP, Urbach DR, Novak CB, von Schroeder HP, McCabe SJ, et al. Health literacy among surgical patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Surg. 2019;43(1):96–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. King JT, Horowitz MB, Bissonette DJ, Tsevat J, Roberts MS. What do patients with cerebral aneurysms know about their condition? Neurosurgery. 2006;58(5):824–30; discussion 824-830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Krupp W, Spanehl O, Laubach W, Seifert V. Informed consent in neurosurgery: patients’ recall of preoperative discussion. Acta Neurochir. 2000;142(3):233–9; discussion 238-239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Prus N, Grant AC. Patient beliefs about epilepsy and brain surgery in a multicultural urban population. Epilepsy Behav. 2010;17(1):46–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Esper CD, Valdovinos BY, Schneider RB. The importance of digital health literacy in an evolving Parkinson’s disease care system. J Park Dis. 2024:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Nimmons D, Armstrong M, Pigott J, Walters K, Schrag A, Ogunleye D, et al. Exploring the experiences of people and family carers from under-represented groups in self-managing Parkinson’s disease and their use of digital health to do this. Digit Health. 2022;8:205520762211022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Marxreiter F, Buttler U, Gassner H, Gandor F, Gladow T, Eskofier B, et al. The use of digital technology and media in German Parkinson’s disease patients. J Parkinsons Dis. 2020;10(2):717–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Alcalde-Rubio L, Hernández-Aguado I, Parker LA, Bueno-Vergara E, Chilet-Rosell E. Gender disparities in clinical practice: are there any solutions? Scoping review of interventions to overcome or reduce gender bias in clinical practice. Int J Equity Health. 2020;19(1):166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Zajacova A, Lawrence EM. The relationship between education and health: reducing disparities through a contextual approach. Annu Rev Public Health. 2018;39:273–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Dinkelbach L, Möller B, Witt K, Schnitzler A, Südmeyer M. How to improve patient education on deep brain stimulation in Parkinson’s disease: the CARE Monitor study. BMC Neurol. 2017;17(1):36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Hirt L, Kern DS, Ojemann S, Grassia F, Kramer D, Thompson JA. Use of three-dimensional printed brain models during deep brain stimulation surgery consultation for patient health literacy: a randomized controlled investigation. World Neurosurg. 2022;162:e526–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Shlobin NA, Clark JR, Hoffman SC, Hopkins BS, Kesavabhotla K, Dahdaleh NS. Patient education in neurosurgery: Part 1 of a systematic review. World Neurosurg. 2021;147:202–14.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Shlobin NA, Clark JR, Hoffman SC, Hopkins BS, Kesavabhotla K, Dahdaleh NS. Patient education in neurosurgery: Part 2 of a systematic review. World Neurosurg. 2021;147:190–201.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Ward M, Ward B, Abraham M, Nicheporuck A, Elkattawy O, Herschman Y, et al. The educational quality of neurosurgical resources on YouTube. World Neurosurg. 2019;130:e660–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Shlobin NA, Hoffman SC, Clark JR, Hopkins BS, Kesavabhotla K, Dahdaleh NS. Social media in neurosurgery: a systematic review. World Neurosurg. 2021;149:38–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Monteiro Grilo A, Ferreira AC, Pedro Ramos M, Carolino E, Filipa Pires A, Vieira L. Effectiveness of educational videos on patient’s preparation for diagnostic procedures: systematic review and Meta-Analysis. Prev Med Rep. 2022;28:101895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Fleming R, Berkowitz B, Cheadle AD. Increasing minority representation in the health professions. J Sch Nurs. 2005;21(1):31–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Nesbitt S, Palomarez RE. Review: increasing awareness and education on health disparities for health care providers. Ethn Dis. 2016;26(2):181–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Bailey M, Anderson S, Hall DA. Parkinson’s disease in african Americans: a review of the current literature. J Park Dis. 2020;10(3):831–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Baugh AD, Shiboski S, Hansel NN, Ortega V, Barjaktarevic I, Barr RG, et al. Reconsidering the utility of race-specific lung function prediction equations. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2022;205(7):819–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Duncan RP, Earhart GM. Randomized controlled trial of community-based dancing to modify disease progression in Parkinson disease. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2012;26(2):132–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Galiatsatos P, Monson K, Oluyinka M, Negro D, Hughes N, Maydan D, et al. Community calls: lessons and insights gained from a medical-religious community engagement during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Relig Health. 2020;59(5):2256–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Nwakoby C, Pierce LJ, Crawford R, Conserve D, Perkins J, Hurt S, et al. Establishing an academic-community partnership to explore the potential of barbers and barbershops in the southern United States to address racial disparities in HIV care outcomes for black men living with HIV. Am J Men’s Health. 2023;17(1):15579883231152114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Releford BJ, Frencher SK, Yancey AK. Health promotion in barbershops: balancing outreach and research in African American communities. Ethn Dis. 2010;20(2):185–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Comparing surgery with and without duraplasty for youth with Chiari malformation type I and Syringomyelia. PCORI; (Accessed Feb 10, 2024). Available from: https://www.pcori.org/research-results/2015/comparing-surgery-and-without-duraplasty-youth-chiari-malformation-type-i-and-syringomyelia. [Google Scholar]

- 100. Comparing entry sites for cerebrospinal fluid shunts in children with Hydrocephalus. PCORI; (Accessed Feb 10, 2024). Available from: https://www.pcori.org/resources/comparing-entry-sites-cerebrospinal-fluid-shunts-children-hydrocephalus. [Google Scholar]

- 101. Comparing two treatments for children with lennox-gastaut Syndrome. PCORI; (Accessed Feb 10, 2024). Available from: https://www.pcori.org/research-results/2021/comparing-two-treatments-children-lennox-gastaut-syndrome. [Google Scholar]

- 102. Zimmerman K, Salehani A, Shlobin NA, Oates GR, Rosseau G, Rocque BG, et al. Community-engaged research: a powerful tool to reduce health disparities and improve outcomes in pediatric neurosurgery. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2022:1–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Feeney M, Evers C, Agpalo D, Cone L, Fleisher J, Schroeder K. Utilizing patient advocates in Parkinson’s disease: a proposed framework for patient engagement and the modern metrics that can determine its success. Health Expect. 2020;23(4):722–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Malone NC, Williams MM, Smith Fawzi MC, Bennet J, Hill C, Katz JN, et al. Mobile health clinics in the United States. Int J Equity Health. 2020;19(1):40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Brill SB, Juckett LA, Chandler E, Brown J, Thomas N, Flax C, et al. Implementing the better starts for all pilot mobile and telehealth intervention in Ohio appalachia: improving access to maternal healthcare. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2023;34(3):1037–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Abraham P, Williams E, Bishay AE, Farah I, Tamayo-Murillo D, Newton IG. The roots of structural racism in the United States and their manifestations during the COVID-19 pandemic. Acad Radiol. 2021;28(7):893–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Steinert JI, Alacevich C, Steele B, Hennegan J, Yakubovich AR. Response strategies for promoting gender equality in public health emergencies: a rapid scoping review. BMJ Open. 2021;11(8):e048292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Schiaffino MK, Ruiz M, Yakuta M, Contreras A, Akhavan S, Prince B, et al. Culturally and linguistically appropriate hospital services reduce Medicare length of stay. Ethn Dis. 2020;30(4):603–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Jordan MC, Tchopev ZN, McClean JC. Education research: diversity in neurology graduate medical education leadership. Neurol Educ. 2023;2(2). [Google Scholar]

- 110. Gutierrez C, Porter A, Ajiboye N, Armstrong J, Mejia N, Spencer K, et al. Diversity and inclusion: a snapshot of the academic neurology workforce (1848). Neurology. 2020;94(15_Suppl ment). [Google Scholar]

- 111. Asfaw ZK, Soto E, Yaeger K, Feng R, Carrasquilla A, Barthélemy EJ, et al. Racial and ethnical diversity within the neurosurgery resident and faculty workforce in the United States. Neurosurgery. 2022;91(1):72–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Plonsker JH, Benzil D, Air EL, Woodrow S, Stippler M, Ben-Haim S. Gender equality in neurosurgery and strategic goals toward a more balanced workforce. Neurosurgery. 2022;90(5):642–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Sowah MN, Fuller AT, Chen SH, Green BA, Ivan ME, Ford HR, et al. Promoting diversity in neurosurgery: a multi-institutional scholarship-based approach. J Neurosurg. 2023:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Glazer G, Tobias B, Mentzel T. Increasing healthcare workforce diversity: urban universities as catalysts for change. J Prof Nurs. 2018;34(4):239–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Marrast LM, Zallman L, Woolhandler S, Bor DH, McCormick D. Minority physicians’ role in the care of underserved patients: diversifying the physician workforce may be key in addressing health disparities. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(2):289–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Charles BL. Telemedicine can lower costs and improve access. Healthc Financ Manage. 2000;54(4):66–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Ganapathy K, Haranath SP, Baez AA, Scott BK. Telemedicine to expand access to critical care around the world. Crit Care Clin. 2022;38(4):809–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Barbosa W, Zhou K, Waddell E, Myers T, Dorsey ER. Improving access to care: telemedicine across medical domains. Annu Rev Public Health. 2021;42:463–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Odisho AY, Lui H, Yerramsetty R, Bautista F, Gleason N, Martin E, et al. Design and development of referrals automation, a SMART on FHIR solution to improve patient access to specialty care. JAMIA Open. 2020;3(3):405–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Bashar MA, Bhattacharya S, Tripathi S, Sharma N, Singh A. Strengthening primary health care through e-referral system. J Fam Med Prim Care. 2019;8(4):1511–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Lee JS, Pérez-Stable EJ, Gregorich SE, Crawford MH, Green A, Livaudais-Toman J, et al. Increased access to professional interpreters in the hospital improves informed consent for patients with limited English proficiency. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(8):863–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Lee D, Begley CE. Racial and ethnic disparities in response to direct-to-consumer advertising. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2010;67(14):1185–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Groeneveld PW, Sonnad SS, Lee AK, Asch DA, Shea JE. Racial differences in attitudes toward innovative medical technology. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(6):559–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Cunningham PJ, Nichols LM. The effects of medicaid reimbursement on the access to care of medicaid enrollees: a community perspective. Med Care Res Rev. 2005;62(6):676–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Saulsberry L, Seo V, Fung V. The impact of changes in medicaid provider fees on provider participation and enrollees’ care: a systematic literature review. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(10):2200–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Callison K, Nguyen BT. The effect of medicaid physician fee increases on health care access, utilization, and expenditures. Health Serv Res. 2018;53(2):690–710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.