ABSTRACT

Military missions are conducted in a multitude of environments including heat and may involve walking under load following severe exertion, the metabolic demands of which may have nutritional implications for fueling and recovery planning. Ten males equipped a military pack loaded to 30% of their body mass and walked in 20°C/40% relative humidity (RH) (TEMP) or 37°C/20% RH (HOT) either continuously (CW) for 90 min at the first ventilatory threshold or mixed walking (MW) with unloaded running intervals above the second ventilatory threshold between min 35 and 55 of the 90 min bout. Pulmonary gas, thermoregulatory, and cardiovascular variables were analyzed following running intervals. Final rectal temperature (MW: p < 0.001, g = 3.81, CW: p < 0.001, g = 4.04), oxygen uptake, cardiovascular strain, and energy expenditure were higher during HOT trials (p ≤ 0.05) regardless of exercise type. Both HOT trials elicited higher final carbohydrate oxidation (CHOox) than TEMP CW at min 90 (HOT MW: p < 0.001, g = 1.45, HOT CW: p = 0.009, g = 0.67) and HOT MW CHOox exceeded TEMP MW at min 80 and 90 (p = 0.049, g = 0.60 and p = 0.024, g = 0.73, respectively). There were no within-environment differences in substrate oxidation indicating that severe exertion work cycles did not produce a carryover effect during subsequent loaded walking. The rate of CHOox during 90 minutes of load carriage in the heat appears to be primarily affected by accumulated thermal load.

KEYWORDS: Warfighter, thermoregulation, metabolism, carbohydrate, ruck, backpack, nutrition

Introduction

There is robust literature quantifying cardiovascular and thermoregulatory responses to heat stress, including increased heart rate (HR), rectal temperature (Tre), sweat rate, and perceptual strain [1–3.] It is well-established that high-intensity exercise (>75% peak oxygen consumption (VO2peak)) increases reliance on glycogen to sustain physical output [4]. Existing studies of macronutrient oxidation patterns during exercise under heat stress commonly employ ≤60 min of steady-state exercise at moderate intensities, e.g. 50–70% VO2peak [5–8], each finding an independent effect of heat stress on respiratory exchange ratio (RER) and/or carbohydrate oxidation (CHOox). Additionally, heat stress has been found to suppress fat oxidation (FATox) even in lower-intensity efforts at 30 and 60% VO2peak [9] and also impair utilization of exogenous CHO [10] which increases potential for impaired mission performance if pre-mission dietary intake is insufficient [11].

Dismounted military and other tactical operations utilizing load carriage face multiple physiologic stressors including prolonged mission durations, consecutive days of heavy exertion, variability in work intensity during missions, and environmental stress [12,13]. Recent studies evaluating the metabolic response to load carriage have focused on relative loads, walking speed, and terrain modeling [14–17], but to our knowledge have not evaluated intra-session variable workloads with or without thermal stress. Further, research evaluating carbohydrate (CHO) and fat oxidation in exercise are often in steady-state conditions over short durations (≤60 minutes) when loaded marches can be expected up to eight hours per day under ideal work and environmental conditions with work periods recommended from 60 to 90 minutes at a time [18]. Current military feeding doctrine recommends 3000 up to 4700 kcal per day for male servicemembers depending on level of exertion, but macronutrient recommendations are broad and not mission or environment specific [19].

Previous research reported increased CHOox during brief (25 min) moderate-intensity exercise at the first ventilatory threshold (VT1) in hot conditions (40°C) and during 5 min of high-intensity exercise at the second ventilatory threshold (VT2) in warm and hot conditions (34º and 40°C) [20]. To our knowledge there has been limited-to-no analysis of any carryover effect on substrate oxidation during steady state exercise following high-intensity efforts. This context is relevant to military operations as dismounted offensive and rescue tactics may involve a movement to contact, high-intensity attack phase(s), and pursuit or exfiltration [21]. An extended increase in CHO utilization following intense activity could potentially lead to under-estimation of CHO needs fostering greater depletion of glycogen reserves, contributing to fatigue in the following minutes-to-days if not corrected with nutrition interventions.

Therefore, this exploratory experiment aimed to evaluate the impact of environmental temperature and added severe intensity exercise with load carriage on energetics and thermal responses during 90 minutes of work. We hypothesized that 1) adding severe intensity exercise above VT2 would increase CHOox during subsequent weighted walking compared to matched continuous walking and 2) hot conditions would increase final CHOox, sweat rate, rating of perceived exertion (RPE), and body temperatures over temperate comparisons.

Materials and methods

Participants

Healthy males were recruited from the local university and resident population for this randomized crossover study (Table 1). This study focused solely on male physiology and metabolic responses to reduce variability within a small sample set considering females exhibit greater fat oxidation and lower CHO oxidation during endurance exercise [22–24]. Subjects were enrolled if they were between the ages of 18–39, capped due to possible impairments in heat dissipation for men over 40 years old [25]. Subjects must have exercised regularly at least twice weekly for the past 12 months, achieved a VO2peak ≥40 ml·kg−1·min−1 during baseline testing, were free of existing musculoskeletal injuries and cardiometabolic diseases, and were not prescribed medications that could affect thermoregulation or physiologic responses to exercise (e.g. β-adrenergic receptor blockers, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, or amphetamine salts).

Table 1.

Subject descriptive statistics.

| Variable | Mean ± SD |

|---|---|

| Age (y) | 25 ± 5 |

| Body Mass (kg) | 78.8 ± 13.4 |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2) | 24.5 ± 2.9 |

| Body Fat (%) | 11.9 ± 3.8 |

| VO2peak (ml·kg−1·min−1) | 49.8 ± 2.9 |

| 30% Body Mass Ruck Load (kg) | 23.7 ± 3.8 |

| Treadmill Incline for VT1 (% grade) | 6 ± 1 |

| % VO2peak at VT1 | 57.3 ± 5.3 |

| % VO2peak at VT2 | 76.9 ± 6.6 |

After being informed of study risks and benefits subjects provided written consent then completed health and training history questionnaires. A multi-pass 24-hour diet recall was collected by a Registered Dietitian to determine dietary CHO and fluid intake. Based on habitual intake, subjects were counseled to consume a standard pre-trial meal containing 2 to 3 g/kg CHO three hours before trials to normalize glycogen levels [26]. Height was measured to the nearest 1 cm using a stadiometer (Seca 217, Seca North America, CA, USA), body mass was measured to the nearest 0.01 kg using a digital scale (Seca 874 Dr, Seca North America, CA, USA), and body fat was assessed by a single trained investigator using 3-point skinfold (Lange, Beta Technology, CA, USA) and Jackson and Pollock body density equations [27].

Experimental trials

Visit 1: Baseline testing

Subjects were instructed to report to the lab hydrated, verified by urine-specific gravity (USG) < 1.020 (Master-URC, ATAGO Co., Tokyo, Japan). Subjects were fitted with a chest HR monitor (T31, Polar, NY, USA) and a one-way breathing mask (Hans Rudolph V2, KS, USA) connected to a metabolic cart (TrueOne 2400; ParvoMedics, UT, USA). Subjects then completed a staged, progressive treadmill test to establish VO2peak [28]. The treadmill workload eliciting the subject’s second ventilatory threshold (VT2) was determined using the V-slope method [29,30].

After at least 15 min rest with ad libitum fluid intake subjects began the first ventilatory threshold (VT1) assessment. Subjects were familiarized with and equipped a U.S. military spec MOLLE 4000 backpack loaded to 30% of their pre-trial body mass, a “fighting load” according to U.S. Army Doctrine 3–21.18 [18], and completed a progressive walking test while connected to the metabolic cart. Speed was fixed at 1.56 m·s−1 while incline progressed in 1% increments every 2 to 4 min until VEVO2 displayed an upward shift with no concurrent changes in VEVCO2, identifying the workload that elicited the subject’s VT1 [31,32]. The treadmill speed and incline that elicited VT1 was constant across all trials.

Visits 2 to 5: Experimental trials

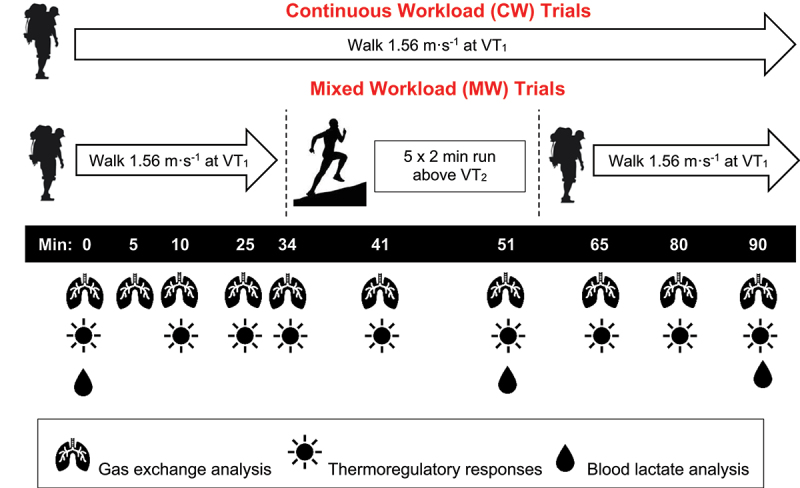

Previous work on substrate oxidation in the heat has reported that 34 to 40°C conditions contrast well with 18 to 20°C (40 to 60% relative humidity [RH]) in cyclists working at moderate and high intensities [5,7,20], though humidity would need to be low in the hot trials to reduce risk of excess hyperthermia over a prolonged trial [33]. Therefore, subjects completed two exercise trials in both hot, dry conditions (HOT: 37°C, 20% RH) and temperate conditions (TEMP: 20°C, 40% RH) (Figure 1). The order of trials was randomized using a Latin square design (two environments x two exercise types), consisting of continuous weighted walking (CW) and walking mixed with interval running (MW). During the CW trials, subjects completed 90 min of walking with 30% body mass load carriage on a motorized treadmill set to 1.56 m·s−1 with incline adjusted to elicit VT1. The MW trials also consisted of 90 min of exercise with subjects completing 35 min of loaded walking at VT1 then the load was removed and subjects completed 20 min of high-intensity interval running above VT2. The intervals consisted of 2 min at VT2 plus 10% speed [34] followed by 2 min of rest, repeated five times. Subjects reequipped the backpack and completed another 35 min of weighted walking at VT1 for a total exercise time of 90 min. Each subject conducted their respective trials at a consistent time of day depending on their individual availability to standardize diurnal variation with trials separated by at least 72 hours.

Figure 1.

Trial timeline and variables collected. VT1 = First ventilatory threshold. VT2 = Second ventilatory threshold. During 1.56 m·s−1 walk at VT1, subjects carried a backpack loaded to 30% of body mass. Subjects removed the pack during the run intervals above VT2 in MW trials.

Before each trial, subjects were instructed to consume a CHO-containing meal three hours before testing, to abstain from caffeine for 12 hours and exercise and alcohol for 24 hours. Subjects wore the same clothing (t-shirt, shorts, and comfortable shoes) for each trial and arrived euhydrated. Upon arrival, subjects entered a private room to collect a urine sample for USG, recorded nude body mass and self-inserted a rectal thermistor (400 series, Medline Inc., IL, USA) 10 cm past the anal sphincter. Thermocrons (DS1822, Maxim Integrated, CA, USA) were affixed to the right upper chest, triceps, anterior quadriceps, and calf to assess mean skin temperature (Tsk) [35]. Subjects were fitted with a HR monitor then entered an environmental chamber set to either HOT or TEMP conditions. Metabolic assessments were completed using a metabolic cart located outside the environmental chamber. Approximately halfway into each trial after collecting data at min 51, the metabolic cart tubing and filter were changed and the cart was recalibrated to minimize the influence of accumulated condensation [36,37].

Trials began with a standing metabolic assessment for 10 min. Blood lactate (BLa) was assessed via fingertip puncture (Lactate Plus, Nova Biomedical, MA, USA) before walking began, at trial-matched min 53 representing the recovery period following interval running, and two min after trial completion. Subjects were instructed to drink to thirst when not wearing the mask. Initial steady state gas exchange variables were collected at min 5, and then further gas exchange, HR, Tre, Tsk, and RPE (6–20 scale) were recorded at min 10, 25, 34, 41, 51, 65, 80, and 90. Post-trial nude towel-dried body mass, total fluid consumption, and urine volume were assessed to determine sweat rate and body mass loss.

Substrate oxidation and energy expenditure

Whole body substrate oxidation rates were estimated as [38]:

| (1) |

| (2) |

Energy expenditure was established as KW·s−1 then converted to watts relative to baseline body mass [38,39].

| (3) |

Statistical methods

Separate two-way time (3 levels) x condition (4 trials) analysis of variance (ANOVA) with repeated measures analyzed differences in the primary dependent variables following the running intervals at minutes 65, 80, and 90: gas exchange (VO2, VCO2, RER), rates of substrate oxidation, energy expenditure, Tsk, Trec, and HR. Data were checked for parametric testing assumptions and Greenhouse-Geisser corrections were applied if sphericity assumptions were violated. Post-hoc paired t-tests were conducted for any detected differences with Hedges’ g used to quantify effect sizes. Data are presented as mean differences and 95% confidence intervals unless otherwise noted. Change in CHOox (ΔCHOox), FATox (ΔFATox), and HR over the entire trial were evaluated comparing the initial 10 vs. final 10 min of load carriage. Change in fluid balance (% body mass loss, sweat rate), final ratings of perceived exertion (RPE), and metabolic shifts (ΔCHOox and ΔFATox) were analyzed using one-way ANOVAs. Statistical analyses were performed using Prism 10 (GraphPad, CA, USA) with α ≤ 0.05 [40].

Results

There was an interaction effect (p = 0.002) in CHOox across trials. In both HOT conditions CHOox was higher at the end of exercise (Table 2). Adding severe exercise to the HOT MW trial produced a noticeably higher end CHOox at min 90 compared to TEMP CW (+0.68 g·min−1, 95% CI [−0.64, 2.00], p < 0.001, g = 1.45). In HOT CW, CHOox was greater at min 90 compared to TEMP CW (+0.51 g·min−1, [−0.20, 1.22], p = 0.009, g = 0.67) and in HOT MW compared to TEMP MW at min 80 (+0.37 g·min−1, [−0.21, 0.95], p = 0.049, g = 0.60) and min 90 (+0.43 g·min−1, [−0.12, 0.98], p = 0.024, g = 0.73). Additionally, there was an interaction effect (p = 0.044) for ΔCHOox (Figure 2). Temperate conditions produced a greater downward shift in ΔCHOox between the initial and final 10 min compared to HOT (CW: −0.41 ± 0.38 g·min−1 vs. HOT: −0.15 ± 0.45, [−0.65, 0.13], p = 0.003, g = 0.62), (MW: −0.37 ± 0.44 vs. HOT: 0.04 ± 0.46, [−0.83, 0.01], p = 0.020, g = 0.91). Change in CHOox was greater in HOT CW compared to HOT MW (p = 0.019, g = 0.41).

Table 2.

Carbohydrate oxidation (g·min−1) across each trial.

| Minute | TEMP CW | TEMP MW | HOT CW | HOT MW |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.35 ± 0.18 | 0.38 ± 0.12 | 0.33 ± 0.13 | 0.37 ± 0.17 |

| 5 | 2.46 ± 0.73 | 2.71 ± 0.68 | 2.58 ± 0.56 | 2.61 ± 0.65 |

| 10 | 2.61 ± 0.58 | 2.68 ± 0.56 | 2.71 ± 0.53 | 2.76 ± 0.62 |

| 25 | 2.48 ± 0.65 | 2.56 ± 0.46 | 2.38 ± 0.69 | 2.69 ± 0.65 |

| 34 | 2.31 ± 0.70 | 2.33 ± 0.46 | 2.48 ± 0.54 | 2.58 ± 0.62 |

| 41* | 2.35 ± 0.81 | 4.21 ± 0.79 | 2.56 ± 0.74 | 4.85 ± 1.34 |

| 51* | 2.13 ± 0.69 | 3.46 ± 0.68 | 2.45 ± 0.60 | 4.52 ± 1.55 |

| 65 | 2.17 ± 0.77 | 2.09 ± 0.39 | 2.44 ± 0.64 | 2.27 ± 0.54 |

| 80 | 2.17 ± 0.77d | 2.33 ± 0.54d | 2.41 ± 0.72 | 2.71 ± 0.68ab |

| 90 | 2.07 ± 0.72cd | 2.32 ± 0.57d | 2.58 ± 0.79a | 2.75 ± 0.60ab |

*Unloaded high-intensity interval running above VT2 was performed between min 35 to 55 in the mixed workload (MW) trials. Values after interval running were analyzed to detect any carryover effects. a = Different from Temp CW, b = Different from Temp MW, c = Different from Hot CW, d = Different from Hot MW, p ≤ 0.05.

Figure 2.

Change in carbohydrate oxidation between the initial 10 and final 10 min (a) and average oxygen uptake (b) during the final 35 min of 90 min load carriage exercise in temperate or hot conditions with or without mid-session severe-intensity running intervals. TEMP: 20°C/40% relative humidity (RH), HOT: 37°C/20% RH. CW: Continuous walking, MW: Mixed walking. 95% CI, p ≤ 0.05.

Fat oxidation also presented an interaction effect (p < 0.001) across trials (Table 3) with TEMP CW presenting a higher rate of FATox compared to HOT MW at min 80 (+0.15 g·min−1, [- 0.05, 0.34], p = 0.007, g = 0.70) and 90 (+0.18 g·min−1, [−0.01, 0.37], p < 0.001, g = 0.88); there were no within-exercise condition differences at specific timepoints. As with CHOox, there was an interaction effect for ΔFATox (p = 0.039) wherein HOT conditions resulted in lower shifts toward FATox than their temperate controls in CW (HOT: 0.16 ± 0.16 g·min−1 vs. TEMP: 0.24 ± 0.14, [- 0.27, 0.91], p = 0.026, g = 0.51) and MW (HOT: 0.09 ± 0.17 g·min−1 vs. TEMP: 0.17 ± 0.25, [- 0.28, 0.12], p = 0.040, g = 0.36), respectively.

Table 3.

Fat oxidation (g·min−1) across each trial.

| Minute | TEMP CW | TEMP MW | HOT CW | HOT MW |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.08 ± 0.05 | 0.07 ± 0.05 | 0.08 ± 0.04 | 0.07 ± 0.05 |

| 5 | 0.17 ± 0.20 | 0.08 ± 0.17 | 0.20 ± 0.12 | 0.17 ± 0.24 |

| 10 | 0.16 ± 0.11 | 0.13 ± 0.14 | 0.16 ± 0.15 | 0.14 ± 0.19 |

| 25 | 0.23 ± 0.14 | 0.19 ± 0.11 | 0.32 ± 0.26 | 0.21 ± 0.21 |

| 34 | 0.31 ± 0.19 | 0.28 ± 0.13 | 0.30 ± 0.15 | 0.25 ± 0.19 |

| 41* | 0.29 ± 0.21 | 0.11 ± 0.27 | 0.26 ± 0.21 | 0.08 ± 0.42 |

| 51* | 0.37 ± 0.20 | 0.39 ± 0.18 | 0.31 ± 0.19 | 0.12 ± 0.51 |

| 65 | 0.36 ± 0.18 | 0.37 ± 0.10 | 0.32 ± 0.16 | 0.40 ± 0.16 |

| 80 | 0.39 ± 0.21d | 0.28 ± 0.18 | 0.36 ± 0.23 | 0.24 ± 0.21a |

| 90 | 0.42 ± 0.21d | 0.26 ± 0.22 | 0.31 ± 0.20 | 0.24 ± 0.20a |

*Unloaded high-intensity interval running above VT2 was performed between min 35 to 55 in the mixed workload (MW) trials. Values after interval running were analyzed to detect any carryover effects. a = Different from Temp CW, b = Different from Temp MW, c = Different from Hot CW, d = Different from Hot MW, p ≤ 0.05.

There was an RER interaction effect (p < 0.001) with RER higher in HOT CW at min 90 vs. TEMP CW (+0.05, [0.0, 0.10], p = 0.04, g = 0.60) and higher in HOT MW than TEMP CW at min 80 (+0.05, [0.0, 0.10], p = 0.003, g = 0.91) and min 90 (+0.05, [0.0, 0.10], p < 0.001, g = 0.99)(Table 4). Relative % VO2peak also presented an interaction effect (p < 0.001) with greater values in HOT compared to TEMP regardless of MW and CW (Table 5). End exercise % VO2peak was higher in HOT CW than TEMP CW (+3.5% VO2peak, [−0.61, 7.61], p = 0.002, g = 0.80) and in HOT MW vs. TEMP MW (+4.0% VO2peak, [−0.98, 8.96], p = 0.001, g = 0.75). BLa was higher at the end of running intervals in MW compared to the same timepoint during CW in both TEMP (7.2 ± 2.8 mmol·L−1 vs. 2.1 ± 0.9, [3.2, 7.1], p < 0.001, g = 2.45) and HOT (10.8 ± 3.2 vs. 2.2 ± 0.6, [6.4, 10.8], p < 0.001, g = 3.74) with higher BLa in HOT MW running intervals compared to TEMP MW (+3.6 mmol·L−1, [0.8, 6.4], p = 0.007, g = 1.15). BLa was similar at min 90 across conditions (TEMP CW: 2.2 ± 1.2 mmol·L−1 vs. HOT CW: 2.5 ± 0.72, p ≥ 0.05, g = 0.30; TEMP MW: 2.6 ± 1.2 vs. HOT MW: 2.6 ± 0.8, p ≥ 0.05, g = 0). Interaction effects for energy expenditure were present (p = 0.029) with reliably higher values in the heat. End-exercise values at min 90 were higher in HOT than TEMP in both the CW trials (HOT: 11.2 ± 0.9 W·kg−1 vs. 10.5 ± 1.0, [−0.2, 1.6], p < 0.001, g = 0.70) and MW trials (HOT: 11.3 ± 1.3 vs. 10.4 ± 1.4, [−0.4, 2.2], p < 0.001, g = 0.67), respectively. There were no within-environment differences in energy expenditure.

Table 4.

Respiratory exchange ratio across each trial.

| Minute | TEMP CW | TEMP MW | HOT CW | HOT MW |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.88 ± 0.07 | 0.91 ± 0.07 | 0.88 ± 0.05 | 0.91 ± 0.06 |

| 5 | 0.95 ± 0.05 | 0.97 ± 0.05 | 0.95 ± 0.03 | 0.95 ± 0.05 |

| 10 | 0.95 ± 0.03 | 0.96 ± 0.03 | 0.96 ± 0.04 | 0.96 ± 0.04 |

| 25 | 0.94 ± 0.04 | 0.95 ± 0.03 | 0.92 ± 0.06 | 0.95 ± 0.05 |

| 34 | 0.92 ± 0.05 | 0.93 ± 0.03 | 0.93 ± 0.04 | 0.93 ± 0.04 |

| 41* | 0.92 ± 0.06 | 0.98 ± 0.04 | 0.93 ± 0.05 | 1.01 ± 0.07 |

| 51* | 0.90 ± 0.05 | 0.93 ± 0.03 | 0.92 ± 0.04 | 0.98 ± 0.08 |

| 65 | 0.90 ± 0.05 | 0.90 ± 0.03 | 0.92 ± 0.04 | 0.90 ± 0.04 |

| 80 | 0.90 ± 0.05d | 0.93 ± 0.05 | 0.91 ± 0.05 | 0.94 ± 0.05ab |

| 90 | 0.89 ± 0.05cd | 0.93 ± 0.06 | 0.92 ± 0.05a | 0.94 ± 0.05a |

*Unloaded high-intensity interval running above VT2 was performed between min 35 to 55 in the mixed workload (MW) trials. Values after interval running were analyzed to detect any carryover effects. a = Different from Temp CW, b = Different from Temp MW, c = Different from Hot CW, d = Different from Hot MW, p ≤ 0.05.

Table 5.

Relative oxygen consumption (%VO2peak) across each trial.

| Minute | TEMP CW | TEMP MW | HOT CW | HOT MW |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 10.80 ± 1.62 | 10.69 ± 1.46 | 10.32 ± 1.50 | 11.65 ± 1.99 |

| 5 | 55.26 ± 4.74 | 55.42 ± 4.88 | 58.47 ± 3.20 | 58.13 ± 6.11 |

| 10 | 57.32 ± 5.27 | 57.12 ± 4.80 | 59.95 ± 4.31 | 59.16 ± 4.93 |

| 25 | 58.27 ± 5.48 | 58.28 ± 4.22 | 60.94 ± 4.25 | 61.55 ± 4.26 |

| 34 | 59.29 ± 4.41 | 58.26 ± 4.31 | 61.74 ± 4.67 | 61.65 ± 3.92 |

| 41* | 59.17 ± 5.78 | 85.04 ± 7.00 | 61.27 ± 2.49 | 87.66 ± 6.82 |

| 51* | 59.01 ± 4.32 | 85.07 ± 5.79 | 61.97 ± 3.39 | 91.31 ± 6.98 |

| 65 | 59.07 ± 5.02cd | 59.20 ± 4.96cd | 62.31 ± 3.72ab | 63.43 ± 5.67ab |

| 80 | 60.66 ± 4.38cd | 59.76 ± 4.62cd | 63.71 ± 3.67ab | 63.66 ± 5.95ab |

| 90 | 60.81 ± 4.80cd | 60.47 ± 4.84cd | 64.29 ± 3.90ab | 64.47 ± 5.71ab |

*Unloaded high-intensity interval running above VT2 was performed between min 35 to 55 in the mixed workload (MW) trials. Values after interval running were analyzed to detect any carryover effects. a = Different from Temp CW, b = Different from Temp MW, c = Different from Hot CW, d = Different from Hot MW, p ≤ 0.05.

Heart rate and RPE

HOT provoked higher cardiac and perceptual strain across conditions (p < 0.001) and at each timepoint compared to TEMP (Figure 3). End-exercise HR was greater in HOT in both the CW (HOT: 185 ± 13 bpm vs. TEMP: 162 ± 14, [10, 36], p < 0.001, g = 1.63) and MW trials (HOT: 183 ± 14 vs. TEMP: 164 ± 12, [7, 31], p < 0.001, g = 1.40). HR climbed steadily between min 10 and 90 in all trials, rising 13 ± 12 bpm (p < 0.001, g = 1.00) and 14 ± 9 (p < 0.001, g = 1.04) in the TEMP CW and MW trials, respectively, and rising 26 ± 10 (p < 0.001, g = 2.00) and 23 ± 9 (p < 0.001, g = 1.76) in the HOT CW and MW trials, respectively. Perceived exertion (6–20 AU, Figure 3) was different across conditions (p < 0.001) with final values higher in HOT regardless of exercise condition (HOT CW 19 ± 1 AU vs. TEMP CW: 15 ± 2, [3, 5], p < 0.001, g = 2.53) (HOT MW: 19 ± 1 vs. TEMP MW: 15 ± 2, [3, 5], p < 0.001, g = 2.53).

Figure 3.

Rectal temperature (a), skin temperature (b), heart rate (c), and perceived exertion (d) responses to 90 min of continuous or mixed-intensity walking in temperate and hot conditions. TEMP: 20°C/40% Relative Humidity (RH), HOT: 37°C/20% RH. CW: Continuous walking, MW: Mixed walking. Unloaded high-intensity interval running above VT2 was performed between min 35 to 55 in the MW trials and is annotated with dashed lines. a = Difference between CW trials. b = Difference between MW trials. 95% CI, p ≤ 0.05.

Thermoregulatory data

Data are presented in Figure 3. The HOT trials elicited a higher Tre at each timepoint (p < 0.001) with final Tre in HOT MW of 39.35 ± 0.19°C vs. 38.30 ± 0.34 in TEMP MW (+1.05°C, [0.79, 1.31], p < 0.001, g = 3.81) and Tre in HOT CW of 39.30 ± 0.24°C compared to 38.33 ± 0.24 in TEMP CW (+0.97°C, [0.74, 1.20], p < 0.001, g = 4.04). There were no within-environment differences in Tre at any timepoint.

Tsk was higher at every timepoint in HOT regardless of exercise condition (p < 0.001). Sweat rate was greater in HOT than TEMP (p < 0.001) for both CW (HOT: 1.30 ± 0.27 L·hr−1 vs. TEMP: 0.77 ± 0.27, [0.28, 0.78], g = 1.96) and MW (1.35 ± 0.38 vs. 0.79 ± 0.27, [0.25, 0.87], g = 1.70); there were no within-environment differences in sweat rate. Percent body mass loss was higher in HOT for both CW (HOT: 1.69 ± 0.60% vs. TEMP: 0.86 ± 0.57, [0.28, 1.38], p = 0.003, g = 1.42) and MW (HOT: 1.31 ± 0.62 vs. TEMP: 0.99 ± 0.64, [−0.27, 0.91], p = 0.021, 0.51). There were no within-environment differences in percent body mass loss for TEMP (p = 0.539, g = 0.21) or HOT (p = 0.054, g = 0.61).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this study was the first to describe the metabolic and physiologic outcomes of prolonged load carriage in the heat using a specific metabolic threshold to prescribe workload, incorporating intermittent severe-intensity workloads mid-trial to assess carryover effects. We observed significant increases in oxygen uptake and energy expenditure in each HOT trial as well as increased CHOox and decreased FATox during the final timepoints in HOT. However, interval running above VT2 during both TEMP and HOT MW trials did not increase CHOox at min 65, 80, or 90 compared to environment-matched CW controls (p ≥ 0.05) as hypothesized.

The change in CHOox appears to be in part driven by the accumulated combination of thermal and exercise stress as both the HOT CW and MW trials increased CHOox at later timepoints compared to their TEMP comparisons. In opposition to our hypothesis, there was not a direct within-environment effect of previous severe-intensity running intervals on subsequent CHOox or FATox, though while HOT MW and TEMP CW were clearly contrasted, the lack of statistical difference in CHOox between HOT CW and TEMP MW during the final timepoints is intriguing. Repeated high intensity exercise produces considerable increases in epinephrine [41] which can lead to increased hepatic glucose output and muscle glycogenolysis [42,43]. Subjects in TEMP MW exhibited comparable CHOox rates to HOT CW despite significantly higher thermal load and oxygen uptake in the HOT CW condition, suggesting that the exercise modality may have modulated metabolic outcomes to a similar degree as heat stress, though future studies with hormonal analyses will provide more definitive insight.

Compared to TEMP CW at min 90, HOT CW and HOT MW increased CHOox 0.5 g·min−1 and 0.68 g·min−1, respectively, thus environmental conditions have implications for nutrition recommendations when multiple prolonged efforts are conducted in a day or during several consecutive days which can exacerbate heat strain [3]. These differences could be further increased with added cortisol and epinephrine surge secondary to operational stress, increased pack weight, and increased thermal strain while wearing equipment that limits evaporative cooling [18].

The final RER during heated trials (CW: 0.92 ± 0.05 and MW: 0.94 ± 0.05) was similar to those reported by Febbraio et al.. (0.91 ± 0.01) and Hargreaves et al.. (0.94 ± 0.01), both of which had participants cycle in hot (40°C) conditions at 70% and 65% VO2peak [5,7]. Both studies reported final Tre ≥39.0°C with significant utilization of muscle glycogen content compared to 20°C. While our study did not conduct cellular analyses, the similar intensity and longer duration of the sessions compared to the Febbraio et al. and Hargreaves et al. studies combined with thermal load likely lead to considerable glycogen consumption. Blacker and colleagues reported that 120 min of flat walking load carriage (25 kg) at a fixed speed in a temperate room reduced RER from 0.90 to 0.83 between initiation and conclusion of exercise [44] and later published a similar study with the same parameters and reported RER shift from 0.94 to 0.87 by min 120 [45]. While our study incorporated relative loading and exercise intensities, there were similar trends in the TEMP CW trial with steady state RER reducing from 0.95 to 0.89, though this trend was nullified by the addition of heat stress to CW (0.95 to 0.92).

The nearly unanimous increase in oxygen consumption during heated exercise was expected as heated exercise studies have shown submaximal VO2 perturbations over time [46,47] though other well-controlled studies have reported no difference in VO2 during heat stress compared to temperate or cool conditions despite significant thermal and cardiovascular strain [5,5,6,48]. The influence of heat on VO2 kinetics is often implicated in degrading peak aerobic performance after sufficient thermal load (Tre + Tsk) has been accumulated [49] while our study employed submaximal workloads that drifted VO2 upward over time as a consequence of possible reduction in cardiac output, fluid shifts, and other systemic effects.

The use of the VT1 exercise prescription was appropriate to produce a significant but sustainable metabolic stimulus and there was no clear correlation between body mass and %VO2peak such that the exercise stimulus would be comparable across subjects of varying mass and relative carried load [31]. Importantly, drinking to thirst minimized dehydration effects to within 2% body mass loss to mitigate confounding influences of dehydration on substrate oxidation [50].

There are limitations to consider in this study. The individualized loading parameter (30% body mass) was based on an optimized “fighting load” according to U.S. Army ATP 3–21.18 and a load used in previous energy expenditure research [15], however it may not translate to real-world applications in which loads can vary widely depending on operational demand. This study did not record radiant heat and air velocity which limits generalization to outdoor operations. Additionally, these findings are relevant to a single bout of exercise and may not be reflective of the strain associated with multiple efforts on a single day or in consecutive days [3,51–53].

To our knowledge, this study was one of the first to incorporate ventilatory thresholds with load carriage while reporting substrate oxidation values as g·min−1, therefore given the novelty it is possible that the study was underpowered. However, these data may provide a benchmark for future studies investigating physiologic and metabolic responses to load carriage in the heat.

While we verbally confirmed a standardized pre-trial meal before each trial based on habitual intake, subjects did not provide written or audiovisual record of other foods consumed in the 24-hours preceding which may have affected RER and substrate oxidation. Subjects were approximately three hours post-prandial for each trial and while each subject’s trials were scheduled at similar times of the day based on their availability, not every subject performed their exercise at a set time, e.g. first thing in the morning following an overnight fast. There are established diurnal variations in glycogen turnover [54,55] however we chose to implement subject-driven and familiar pre-trial meal procedures to reduce subject burden considering the otherwise substantial metabolic and physiologic strain experienced in the study. Future studies may consider assessing catecholamine responses and cytokine production to elucidate mechanistic changes in steady state metabolomics following heavy exertion.

With continued increases in female enlistment, future studies should evaluate female responses to heated load carriage and assess for inter-sex differences. Other factors to consider include varying and accounting for air, humidity, solar, and wind stress, the incorporation of armor, boots, uniforms, weapons, and other held loads, however given the degree of thermal strain observed in our study with sports clothing and low humidity, environmental conditions may need to be cooler and/or incorporate rest periods to temper rise in Tre. Lastly, daily nutritional intake has not been thoroughly explored with regards to substrate oxidation rates, thermotolerance, or measures of performance in the heat.

Ninety minutes of loaded walking in the heat results in elevated end-exercise carbohydrate oxidation and evokes considerable increases in HR, Tre, and sweat loss. Adding unloaded severe-intensity exercise in the middle of the walking trial does not evoke a further increase in metabolic or physiologic variables after returning to loaded walking compared to continuous walking in environment-matched controls. This suggests that the rest cycles during the severe-intensity exercise may have mitigated sympathetic strain. Future studies should incorporate female subjects load carriage in the heat and consider standardized nutrition protocols twelve or more hours before trials. Mission planners should consider additional carbohydrates and fluids for load carriage operations in hot environments.

Abbreviations

- RH

relative humidity

- CW

Continuous workload

- MW

Mixed workload

- CHOox

Carbohydrate oxidation

- HOT

37°C/20% relative humidity conditions

- TEMP

20°C/40% relative humidity conditions

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- [1].Akerman AP, Tipton M, Minson CT, et al. Heat stress and dehydration in adapting for performance: good, bad, both, or neither? Temperature. 2016;3(3):412–436. DOI: 10.1080/23328940.2016.1216255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Bartman NE, Larson JR, Looney DP, et al. Do the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health recommendations for working in the heat prevent excessive hyperthermia and body mass loss in unacclimatized males? J Occup Environ Hyg. 2022;19(10–11):596–602. DOI: 10.1080/15459624.2022.2123493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Pryor RR, Pryor JL, Vandermark LW, et al. Exacerbated heat strain during consecutive days of repeated exercise sessions in heat. J Sci Med Sport. 2019;22(10):1084–1089. DOI: 10.1016/j.jsams.2019.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Vigh-Larsen JF, Ørtenblad N, Spriet LL, et al. Muscle glycogen metabolism and high-intensity exercise performance: a narrative review. Sports Med. 2021;51(9):1855–1874. DOI: 10.1007/s40279-021-01475-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Febbraio M, Snow RJ, Stathis CG, et al. Effect of heat stress on muscle energy metabolism during exercise. J Appl Physiol. 1994;77(6):2827–2831. DOI: 10.1152/jappl.1994.77.6.2827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Fernández-Elías VE, Hamouti N, Ortega JF, et al. Hyperthermia, but not muscle water deficit, increases glycogen use during intense exercise. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2015;25(S1):126–134. DOI: 10.1111/sms.12368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Hargreaves M, Angus D, Howlett K, et al. Effect of heat stress on glucose kinetics during exercise. J Appl Physiol. 1996;81(4):1594–1597. DOI: 10.1152/jappl.1996.81.4.1594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Jentjens RLPG, Underwood K, Achten J, et al. Exogenous carbohydrate oxidation rates are elevated after combined ingestion of glucose and fructose during exercise in the heat. J Appl Physiol. 2006;100(3):807–816. DOI: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00322.2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Ruíz-Moreno C, Gutiérrez-Hellín J, González-García J, et al. Effect of ambient temperature on fat oxidation during an incremental cycling exercise test. Eur J Sport Sci. 2021;21(8):1140–1147. DOI: 10.1080/17461391.2020.1809715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Jentjens RLPG, Wagenmakers AJM, Jeukendrup AE.. Heat stress increases muscle glycogen use but reduces the oxidation of ingested carbohydrates during exercise. J Appl Physiol. 2002;92(4):1562–1572. DOI: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00482.2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Kenefick RW, Heavens KR, Luippold AJ, et al. Effect of physical load on aerobic exercise performance during heat stress. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2017;49(12):2570–2577. DOI: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000001392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Cuddy JS, Sol JA, Hailes WS, et al. Work patterns dictate energy demands and thermal strain during wildland firefighting. Wilderness Environ Med. 2015;26(2):221–226. DOI: 10.1016/j.wem.2014.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Margolis LM, Crombie AP, McClung HL, et al. Energy requirements of US army special operation forces during military training. Nutrients. 2014;6(5):1945–1955. DOI: 10.3390/nu6051945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Looney DP, Lavoie EM, Vangala SV, et al. Modeling the metabolic costs of heavy military backpacking. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2022;54(4):646–654. DOI: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000002833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Looney DP, Santee WR, Blanchard LA, et al. Cardiorespiratory responses to heavy military load carriage over complex terrain. Appl Ergon. 2018;73:194–198. DOI: 10.1016/j.apergo.2018.07.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Looney DP, Santee WR, Hansen EO, et al. Estimating energy expenditure during level, uphill, and downhill walking. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2019;51(9):1954–1960. DOI: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000002002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Looney DP, Santee WR, Karis AJ, et al. Metabolic costs of military load carriage over complex terrain. Mil Med. 2018;183(9–10):e357–e362. DOI: 10.1093/milmed/usx099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Department of the Army . (2022). ATP 3-21.18 Foot Marches. https://armypubs.army.mil/epubs/DR_pubs/DR_a/ARN35163-ATP_3-21.18-000-WEB-1.pdf

- [19].Department of the Army, the Navy, and the Air Force . (2017). Nutrition And Menu Standards For Human Performance Optimization. U.S. Department of Defense. https://armypubs.army.mil/epubs/DR_pubs/DR_a/pdf/web/AR40-25_WEB_Final.pdf [Google Scholar]

- [20].Maunder E, Plews DJ, Merien F, et al. Exercise intensity regulates the effect of heat stress on substrate oxidation rates during exercise. Eur J Sport Sci. 2020;20(7):935–943. DOI: 10.1080/17461391.2019.1674928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Department of the Army . Field manual 3-90: tactics. Department of the Army; 2023. https://armypubs.army.mil/epubs/DR_pubs/DR_a/ARN38160-FM_3-90-000-WEB-1.pdf [Google Scholar]

- [22].Green HJ, Fraser IG, Ranney DA. Male and female differences in enzyme activities of energy metabolism in vastus lateralis muscle. J Neurol Sci. 1984;65(3):323–331. DOI: 10.1016/0022-510x(84)90095-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Horton TJ, Pagliassotti MJ, Hobbs K, et al. Fuel metabolism in men and women during and after long-duration exercise. J Appl Physiol (1985) 1998;85(5): 1823–1832. DOI: 10.1152/jappl.1998.85.5.1823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Purdom T, Kravitz L, Dokladny K, et al. Understanding the factors that effect maximal fat oxidation. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2018;15:3.DOI: 10.1186/s12970-018-0207-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Larose J, Boulay P, Sigal RJ, et al. Age-related decrements in heat dissipation during physical activity occur as early as the age of 40. PLoS One. 2013;8(12):e83148. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Kerksick CM, Arent S, Schoenfeld BJ, et al. International society of sports nutrition position stand: nutrient timing. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2017;14(1):33. DOI: 10.1186/s12970-017-0189-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Loenneke JP, Barnes JT, Wilson JM, et al. Reliability of field methods for estimating body fat. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging. 2013;33(5):405–408. DOI: 10.1111/cpf.12045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Bruce RA, Pearson R, Lovejoy FW. Variability of respiratory and circulatory performance during standardized exercise 1. J Clin Invest. 1949;28(6 Pt 2):1431–1438. DOI: 10.1172/JCI102208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Beaver WL, Wasserman K, Whipp BJ. A new method for detecting anaerobic threshold by gas exchange. J Appl Physiol. 1986;60(6):2020–2027. DOI: 10.1152/jappl.1986.60.6.2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Gaskill SE, Ruby BC, Walker AJ, et al. Validity and reliability of combining three methods to determine ventilatory threshold. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001;33(11):1841–1848. DOI: 10.1097/00005768-200111000-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Pallarés JG, Morán-Navarro R, Ortega JF, et al. Validity and reliability of ventilatory and blood lactate thresholds in well-trained cyclists. PLoS One. 2016;11(9):e0163389. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0163389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Phillips DB, Stickland MK, Lesser IA, et al. The effects of heavy load carriage on physiological responses to graded exercise. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2016;116(2):275–280. DOI: 10.1007/s00421-015-3280-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Mekjavic IB, Ciuha U, Grönkvist M, et al. The effect of low ambient relative humidity on physical performance and perceptual responses during load carriage. Front Physiol. 2017;8(451). DOI: 10.3389/fphys.2017.00451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Neder JA, Stein R. A simplified strategy for the estimation of the exercise ventilatory thresholds. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2006;38(5):1007–1013. DOI: 10.1249/01.mss.0000218141.90442.6c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Ramanathan NL. A new weighting system for mean surface temperature of the human body. J Appl Physiol. 1964;19(3):531–533. DOI: 10.1152/jappl.1964.19.3.531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Bassett D, Howley ET, Thompson DL, et al. Validity of inspiratory and expiratory methods of measuring gas exchange with a computerized system. J Appl Physiol. 2001;91(1):218–224. DOI: 10.1152/jappl.2001.91.1.218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Garcia-Tabar I, Eclache JP, Aramendi JF, et al. Gas analyzer’s drift leads to systematic error in maximal oxygen uptake and maximal respiratory exchange ratio determination. Front Physiol. 2015; 6: doi: 10.3389/fphys.2015.00308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Péronnet F, Massicotte D. Table of nonprotein respiratory quotient: an update. Can J Sport Sci. 1991;16(1):23–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Kipp S, Byrnes WC, Kram R. Calculating metabolic energy expenditure across a wide range of exercise intensities: the equation matters. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2018;43(6):639–642. DOI: 10.1139/apnm-2017-0781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Headquarters, Department of the Army . Technical Bulletin, Medical (TB MED) 507: heat stress control and heat casualty management. United States Army; 2022. https://armypubs.army.mil/epubs/DR_pubs/DR_a/ARN35159-TB_MED_507-000-WEB-1.pdf [Google Scholar]

- [41].Marliss EB, Simantirakis E, Miles PD, et al. Glucoregulatory and hormonal responses to repeated bouts of intense exercise in normal male subjects. J Appl Physiol. 1991;71(3):924–933. DOI: 10.1152/jappl.1991.71.3.924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Febbraio M, Lambert DL, Starkie RL, et al. Effect of epinephrine on muscle glycogenolysis during exercise in trained men. J Appl Physiol. 1998;84(2):465–470. DOI: 10.1152/jappl.1998.84.2.465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Howlett K, Febbraio M, Hargreaves M. Glucose production during strenuous exercise in humans: role of epinephrine. Am J Physiol. 1999;276(6):E1130–1135. DOI: 10.1152/ajpendo.1999.276.6.E1130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Blacker SD, Fallowfield JL, Bilzon JL, et al. Physiological responses to load carriage during level and downhill treadmill walking. Med Sport. 2009;13(2):116–124. DOI: 10.2478/v10036-009-0018-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Blacker SD, Williams NC, Fallowfield JL, et al. The effect of a carbohydrate beverage on the physiological responses during prolonged load carriage. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2011;111(8):1901–1908. DOI: 10.1007/s00421-010-1822-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Arngrímsson SÁ, Stewart DJ, Borrani F, et al. Relation of heart rate to percentV˙o 2 peak during submaximal exercise in the heat. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2003;94(3):1162–1168. DOI: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00508.2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Wingo JE, Lafrenz AJ, Ganio MS, et al. Cardiovascular drift is related to reduced maximal oxygen uptake during heat stress. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2005;37(2):248–255. DOI: 10.1249/01.mss.0000152731.33450.95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Young A, Sawka M, Levine L, et al. Skeletal muscle metabolism during exercise is influenced by heat acclimation. J Appl Physiol. 1986;59(6):1929–1935. DOI: 10.1152/jappl.1985.59.6.1929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Cheuvront SN, Kenefick RW, Montain SJ, et al. Mechanisms of aerobic performance impairment with heat stress and dehydration. J Appl Physiol. 2010;109(6):1989–1995. DOI: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00367.2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].González-Alonso J, Calbet JAL, Nielsen B. Metabolic and thermodynamic responses to dehydration-induced reductions in muscle blood flow in exercising humans. J Physiol. 1999;520(2):577–589. DOI: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.00577.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Meade RD, D’Souza AW, Krishen L, et al. The physiological strain incurred during electrical utilities work over consecutive work shifts in hot environments: a case report. J Occup Environ Hyg. 2017;14(12):986–994. DOI: 10.1080/15459624.2017.1365151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Notley SR, Meade RD, D’Souza AW, et al. Cumulative effects of successive workdays in the heat on thermoregulatory function in the aging worker. Temperature. 2018;5(4):293–295. DOI: 10.1080/23328940.2018.1512830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Schlader ZJ, Colburn D, Hostler D. Heat strain is exacerbated on the second of consecutive days of fire suppression. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2017;49(5):999–1005. DOI: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000001191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Iwayama K, Onishi T, Maruyama K, et al. Diurnal variation in the glycogen content of the human liver using 13C MRS. NMR Biomed. 2020;33(6):e4289. DOI: 10.1002/nbm.4289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Iwayama K, Tanabe Y, Tanji F, et al. Diurnal variations in muscle and liver glycogen differ depending on the timing of exercise. J Physiol Sci. 2021;71(1):35. DOI: 10.1186/s12576-021-00821-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]