Abstract

DosS is a heme-containing histidine kinase that triggers dormancy transformation inMycobacterium tuberculosis. Sequence comparison of the catalytic ATP-binding (CA) domain of DosS to other well-studied histidine kinases reveals a short ATP-lid. This feature has been thought to block binding of ATP to DosS’s CA domain in the absence of interactions with DosS’s dimerization and histidine phospho-transfer (DHp) domain. Here, we use a combination of computational modeling, structural biology, and biophysical studies to re-examine ATP-binding modalities in DosS. We show that the closed-lid conformation observed in crystal structures of DosS CA is caused by the presence of Zn2+ in the ATP binding pocket that coordinates with Glu537 on the ATP-lid. Furthermore, circular dichroism studies and comparisons of DosS CA’s crystal structure with its AlphaFold model and homologous DesK reveal that residues 503–507 that appear as a random coil in the Zn2+-coordinated crystal structure are in fact part of the N-box α helix needed for efficient ATP binding. Such random-coil transformation of an N-box α helix turn and the closed-lid conformation are both artifacts arising from large millimolar Zn2+ concentrations used in DosS CA crystallization buffers. In contrast, in the absence of Zn2+, the short ATP-lid of DosS CA has significant conformational flexibility and can effectively bind AMP-PNP (Kd = 53 ± 13 μM), a non-hydrolyzable ATP analog. Furthermore, the nucleotide affinity remains unchanged when CA is conjugated to the DHp domain (Kd = 51 ± 6 μM). In all, our findings reveal that the short ATP-lid of DosS CA does not hinder ATP binding and provide insights that extend to 2988 homologous bacterial proteins containing such ATP-lids.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Bacterial species often utilize a two-component signal transduction (TCS) pathway to sense and respond to changes in their microenvironment. This pathway consists of a histidine kinase (HK) and a response regulator (RR) that interact to transfer the signal from extracellular stimuli to bacterial DNA (Figure S1).1 HKs are frequently observed as homodimeric transmembrane enzymes, which upon binding ATP, catalyze autophosphorylation of a conserved histidine found in its dimerization and histidine phosphotransfer (DHp) domain in response to the stimuli (Figure 1a).2 The phosphoryl group on the HK’s catalytically activated histidine is then transferred to an aspartate residue of the RR, which binds to bacterial DNA to regulate gene transcription in response to the extracellular stimuli (Figure S1).3 As a result, HKs are essential for bacteria to adapt to various environmental changes, making them attractive drug targets due to their orthogonality to eukaryotic sensory domains and their importance to pathogenicity and bacterial survival.4,5 One such extensively investigated HK drug target is DosS fromMycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) that triggers dormancy in the bacteria under hypoxic/NO/CO-rich extracellular redox environments, making it resistant to tuberculosis drug regimes.6–11 Specifically, upon sensing hypoxia or nanomolar amounts of NO/CO, DosS catalyzes autophosphorylation of its H395 residue and then transfers the phosphoryl group to the D54 residue of the RR, DosR. The phosphorylated DosR, in turn, activates the transcription of more than 50 dormancy-related genes in Mtb, including several genes implicated in the proteostasis network.12,13 Despite consensus on downstream phospho-transfer events, the molecular basis for controlling interdomain redox signal transduction within the DosS heme-based HK sensor remains unclear.14,15 Previous studies have suggested that the short ATP-lid in the catalytic ATP-binding domain (CA) of DosS inhibits kinase activity by blocking ATP binding in the absence of interdomain interactions with the DHp domain of full-length DosS.16 Given the significance of DosS in Mtb’s persistence and drug resistance, it is critical to closely examine and understand DosS’s ATP-binding modalities in comparison to those of other well-studied HKs.

Figure 1.

(a) Representation of a dimeric HK complex. A sensory domain (in pink) is located in the extracellular space while the dimerization and histidine phosphotransfer (DHp) domain (in green) and the catalytic ATP-binding domain (CA in gray) extend into the intracellular cytosolic space. Crystal structures of (b) the PhoQ CA bound to an ATP analog (AMP-PNP; PDB ID: 1ID0) and (c) DosS CA bound to a zinc ion (PDB ID: 3ZXO). Zn2+ coordinating residues are highlighted in the inset of panel (c). In both structures, the N-box is colored orange, G-boxes are colored red, and the ATP-lid is colored green. (d) Alignment of DosS and PhoQ CA protein sequences showing various boxes and secondary structures.

The ATP-binding pocket of a typical HK CA is an α-helix/β-sheet sandwich (the Bergerat fold) featuring several conserved amino acid sequences referred to as “boxes”.17 How these boxes contribute to ATP binding is well understood for HKs like PhoQ and DesK.18,19 For instance, the PhoQ CA (Figure 1b) contains one N-box (orange), three G-boxes (red), and one F-box containing ATP-lid (colored green). The N-box has conserved asparagine, histidine, and lysine/arginine residues that bind to the triphosphate chain of ATP via ionic and hydrogen bonding (H-bonding) interactions. All three G-boxes possess multiple glycine residues that afford flexibility to the protein’s macromolecular structure for optimal ATP binding.20 Moreover, the adenine moiety of ATP is H-bonded to a conserved aspartate in the G1-box. Additionally, the CA domain comprises an ATP-lid that is characterized by considerable conformational flexibility in the absence of any bound nucleotide and often includes a conserved phenylalanine containing F-box. Upon nucleotide binding, the lid interacts with the DHp domain to correctly position the γ-phosphate of ATP for an autophosphorylation reaction.17 However, the ATP-lid displays length and secondary structure variations across different HK types. For instance, the ATP-lid of PhoQ CA has 21 residues and is significantly longer than that of DosS that has only 6 residues with the F-box absent (highlighted green in Figures 1c,d and S2). This short ATP-lid motif has been hypothesized to modulate DosS kinase activity by preventing ATP binding in the absence of interdomain interactions with the DHp domain of full-length DosS.16 In this work, we use a combination of computational modeling, structural biology, and biophysical investigations to further explore the structural and molecular aspects of ATP binding to the DosS CA domain. We show that despite possessing a short ATP lid, DosS CA exhibits an affinity to ATP (Kd = 53 ± 13 μM) that is comparable to other HK’s and is usually bound to ATP under physiological conditions of 1–5 mM ATP in the bacteria.21 Overall, our studies demonstrate key structural aspects and molecular interactions that enable ATP binding to DosS and are applicable to 2988 other homologous bacterial kinases that feature a short ATP-lid.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

All reagents were purchased from commercial sources and used without further purification.

Plasmid Design and Mutagenesis.

pET23a (+) vectors encoding DosS CA (amino acids 454–578 of full-length DosS) and DosS DHp-CA (amino acids 369–578 of full-length DosS) sequence with an N-terminal six-His tag and a TEV protease site were purchased from GenScript. DosS CA mutants were prepared from the WT plasmid via site-directed mutagenesis with end-to-end primers similar to methods described in previous work.22 The forward and reverse primers (5′ to 3′) for the H507F mutation were: ACACTTACAGTAAGAGTGAAGGTAGACGATGATTTG and GGATGCCTTCGCGAATCTAACAGCGTT, respectively. The forward and reverse primers (5′ to 3′) for the D529N mutation were: TCGAAGTCACTAATAACGGGCGGGG and TGCACAAATCATCGTC-TACCTTCACTCTTACTG, respectively. The forward and reverse primers (5′ to 3′) for the E537A mutation were: GTTACCTGATGCGTTCACTGGCTCCG and CCCCGCCCGTTATCAGTGACTTCGAT, respectively. All plasmid sequences were confirmed via sequencing by ACTG.

Expression and Purification of WT DosS CA, Its Mutants, and DosS DHp-CA.

BL21(DE3) competent cells (Thermo Fisher) were transformed with the pET23a(+)-DosS CA plasmid and plated on LB agar plates containing 100 μg/mL ampicillin. For DosS DHp-CA, the parent plasmid pET23a(+)-DosS DHp-CA was cotransformed with pACYC-GroEL/ES-TF (AddGene) and cell growth was conducted in the presence of 100 μg/mL ampicillin and 37 μg/mL chloramphenicol. Primary cultures were inoculated with a single colony from an agar plate and grown overnight at 37 °C while being shaken at 220 rpm. The secondary cultures were inoculated with 25 mL of primary culture and were grown in 1.5 L of 2XYT media containing 100 μg/mL ampicillin at 37 °C while shaking at 220 rpm. The cell density was monitored until the OD600 reached 0.6–0.8. Protein expression was induced with 0.5 mM IPTG at 18 °C while shaking at 180 rpm for 18 h. Cells were harvested via centrifugation at 8000 rpm for 15 min at 4 °C. The cell pellet was resuspended in 50 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 250 mM sodium chloride, and 1% Triton X-100 and lysed via sonication (Fisher Scientific) while on ice. The crude lysate was centrifuged for 1 h at 20,000 rpm and 4 °C (Beckman Coulter). The supernatant was filtered using a 0.44 μm syringe filter (Sartorius) and applied to a 5 mL HisTrap FF column (GE Healthcare) at a rate of 2 mL/min. The column was washed with 75 mL of 50 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 250 mM sodium chloride, and 20 mM imidazole at a rate of 2 mL/min. Recombinant protein was eluted with 50 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 250 mM sodium chloride, and 250 mM imidazole. The eluted protein was concentrated and buffer exchanged into 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 15 mM MgCl2, 94.5 mM NaCl, and 5% glycerol. Finally, the protein solution was concentrated to ~6 mL using a centricon (MW cutoff = 10 kDa) and purified via size exclusion chromatography with a HiLoad 26/600 Superdex 75 pg column (GE Healthcare). The purified protein solution was diluted to 135 μM (~2.0 mg/mL) in buffer containing 0.5 mM EDTA and 1 mM DTT, and 4.5 μM TEV Protease was added to it. The reaction mixture was gently rotated overnight, and the cleaved protein product was purified using a HisTrap FF column. EDTA and DTT were removed via a PD-10 column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated with 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 15 mM MgCl2, 94.5 mM NaCl, and 5% glycerol. WT DosS CA was concentrated to 2.25 mM, as estimated on the basis of absorbance at 280 nm using the extinction coefficient 5579 M−1 cm−1 determined via the BCA assay. Variants of DosS CA were expressed and purified using a similar protocol with minor variations. DosS DHp-CA was concentrated to 1.8 mM based on extinction coefficient 6990 M−1 cm−1 at 280 nm. Purity of WT DosS CA, its mutants, and DosS DHp-CA was verified using SDS PAGE gel (Figure S3).

X-ray Crystallography and Protein Structure Determination.

Initial crystallographic screening used the sitting-drop vapor diffusion method, conducted at the Nanoliter Crystallization Facility at the University of Minnesota (Minneapolis, MN). For each drop, 100 nL of 581 mM ABD (7.7 mg/mL) was mixed with 100 nL of commercial screening kits, namely, Index (Hampton Research), PEG/ION HT (Hampton Research), and Shotgun1 (Molecular Dimensions). A total of 288 different conditions were tested, with 864 total drops with three samples per condition. Diffraction-quality crystals were generated in 24-well hanging drop crystallization plates by mixing 1–2 μL of 581 μM CA (7.7 mg/mL) with 1–2 μL of 10 mM ZnCl2, 20% PEG 6000 (w/v), and 100 mM MES (pH 6.0) or 100 mM HEPES (pH 7.2). The CA crystals were cryoprotected by soaking in the reservoir solution supplemented with ethylene glycol, by gradually increasing the ethylene glycol concentration to 20%, and subsequently flash frozen in liquid nitrogen. X-ray diffraction data were collected at the NE-CAT beamline 24-ID-C of the Advanced Photon Source (Lemont, IL) and processed using XDS.23 Structures were determined by molecular replacement with PHASER using DosS (PDB ID: 3ZXO) as the search model.16,24–26 Iterative model building and refinement were conducted using COOT and PHENIX.27,28 A summary of the crystallographic data statistics is shown in Table S1. Figures were generated using Chimera.29 The coordinates and reflection files were deposited with http://rcsb.org/ with accession code 8SBM.

Molecular Dynamics Studies.

For the simulation of ATP-lid dynamics the starting structure of WT DosS CA was taken from the crystal structure (PDB: 8SBM). Using the tleap module in AmberTools22, explicit hydrogen atoms were added, Na+ ions were added to a concentration of 0.15 M, the system was neutralized with Cl− counterions, and the DosS CA protein was parametrized using the ff14SB force field.30,31 For simulations including Zn2+, a force field modification was included as well as a restraint that maintained the following distances: ~1.94 Å between Zn2+ and H507, ~1.82 Å between Zn2+ and D529, ~2.00 Å between Zn2+ and E537, and ~1.95 Å between Zn2+ and a water molecule.32 The protein was solvated in a 10.0 Å cuboid unit cell with TIP3P water molecules.33,34 The protein system was minimized, gently heated to 300 °C, and equilibrated for 2 ns. Three independent 300 ns simulations were performed. CPPTRAJ was used to perform all trajectory analyses. To simulate the protein-nucleotide interactions of the ATP-docked DosS CA crystal structure, atomic coordinates were obtained from the results of a docking calculation. The system was prepared using AmberTools22 as described above.30 In addition to the ff14SB force field, the DNA.OL15 force field was applied to parametrize ATP, and a force field modification was applied to the polyphosphate group.35,36 Restraints were placed between atom N6 of ATP and a carboxylate oxygen atom of D529 to maintain a distance ~3.0 Å, between Mg2+ and an oxygen atom on the γ-phosphate of ATP, and between Mg2+ and an oxygen atom on the β-phosphate of ATP to prevent dissociation. The distance of the Mg2+ restraints was centered at 2.0 Å. System preparation, minimization, equilibration, and heating were performed as described above. Three independent 300 ns simulations were performed.

For simulations with ATP-bound DosS CA Alphafold model, the atomic coordinates of DosS CA were obtained from the AlphaFold predicted structure of DosS.37 DosS CA structure was aligned to the ATP-bound crystal structure of the homologous DesK CA domain (PDB: 3EHG) using the MatchMaker tool in Chimera.29 The rigid body superposition of DosS and DesK allowed for the atomic coordinates of ATP from DesK to be superimposed onto the simulated DosS CA domain structures.38 The system was prepared using AmberTools22 as described above.30 In addition to the ff14SB force field, the DNA.OL15 force field was used to parametrize ATP, and a force field modification was applied to the polyphosphate group.35,36 System preparation, minimization, equilibration, and heating were performed as described above. No restraint was needed to maintain ATP interactions with DosS CA. Three independent 300 ns simulations were performed.

Docking Studies.

Atomic coordinates of the DosS CA were obtained from frame 493 of the molecular dynamics (MD) simulation, in which the ATP-lid motif formed an open conformation. The open conformation was determined by finding the maximum distance between the Cα’s of His507 and Glu537 (Figure 2c). Molecular docking simulations were performed using Glide (Schrödinger). The protein structure was minimized using the default parameters. We constructed ATP-Mg2+ with Mg2+ bound to oxygen atoms on the γ- and β-phosphate groups and minimized the complex using default parameters. The receptor grid was generated and centered on Asp529, a conserved residue that forms analogous interactions between ATP and homologous CAs. Residues surrounding the presumed binding pocket of ATP were allowed to rotate freely during the docking simulation. ATP-Mg2+ was docked to the protein crystal structure using Glide with flexible ligand sampling, XP scoring function, and postdocking minimization. All other parameters were kept as default.

Figure 2.

(a) Crystal structure of DosS CA showing the primary coordination sphere of zinc (PDB ID: 8SBM). (b) Distance variation between the alpha carbons of H507 and E537 residues of DosS CA with zinc (blue) and without zinc (black) during MD simulations. (c) Structure of the MD frame with the greatest distance between H507 and E537. (d) ITC data with DosS CA in the presence of 0 μM (black), 10 nM (pink), 0.21 mM (purple), and 1.4 mM (blue) zinc. A table with Kd and n values for these variants is summarized in the inset. (e) AlphaFold structure of the DosS CA domain shows an extra α helix in the N-box. (f) CD data of DosS CA in the absence (black) and presence (blue) of 10 mM zinc.

Isothermal Calorimetry Measurements.

Isothermal calorimetry (ITC) experiments were performed using a low volume Nano ITC (TA Instruments) similar to previous studies.39,40 A 0.5 mL 600 μM DosS CA solution was prepared and placed in a 6 kDa molecular weight cutoff dialysis membrane (Spectra/Por). Protein was dialyzed overnight against 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 15 mM MgCl2, and 94.5 mM NaCl while slowly stirring at 4 °C. The protein solution was filtered via 0.22 μm syringe filter and then used to prepare a 400 μL 400 μM protein, 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 15 mM MgCl2, 94.5 mM NaCl, and 0.8 mM TCEP titrand solution. For measurements with DosS DHp-CA, the dialysis buffer was composed of 50 mM HEPES (pH 8.0), 5 mM MgCl2, and 94.5 mM NaCl. A 400 μL 2.4 mM AMP-PNP solution containing 0.8 mM TCEP was prepared using filtered dialysate. A control titrand solution containing no protein and 0.8 mM TCEP was prepared with filtered dialysate. The sample cell was filled with 300 μL of protein or control solution and was cooled to 10 °C. The syringe was loaded with 50 μL of nucleotide solution. The nucleotide solution was titrated into the sample cell with one 0.5 and 24 2 μL injections while stirring at 200 rpm with 200 s in between injections to ensure thorough mixing of the cell. ITC measurements in the presence of metals were performed by including various concentrations of Zn(OAc)2, 1.4 mM CaCl2 or 1.4 mM CoCl2 in the dialysis buffer. Data analysis was performed using NanoAnalyze software (TA Instruments). The enthalpy of dilution of the nucleotide was subtracted from the raw data. Corrected heat data were integrated peak by peak, and the area was normalized per mole of injectant to get a plot of observed enthalpy change per mole of nucleotide against the molar ratio of nucleotide to protein.

Circular Dichroism of DosS CA.

Solutions of 40 μM DosS CA were prepared with and without 10 mM Zn(OAc)2 in buffer containing 10 mM BisTris at pH 7 and 50 mM NaF. A 1 mm quartz cuvette was used for sample measurement in a Jasco 815 circular dichroism (CD) spectrometer. Samples were measured between the wavelengths of 190 to 260 at 0.5 nm intervals with a bandwidth = 2 nm, data integration time = 2 s, and a scan rate = 50 nm/min. A baseline was obtained using buffer containing 10 mM BisTris (pH 7) and 50 mM NaF with and without 10 mM Zn(OAc)2. Ellipticity (, mdeg) was converted to molar ellipticity using the following equation , where MW is the average molecular weight, PL is the path length (in cm), and C is the protein concentration (in mg/mL). The calibration of the instrument was validated with a 0.06% CSA solution.

Bioinformatics Studies.

A sequence-based homology search (NCBI BLAST) of residues 454–578, the DosS CA domain, was performed using the nonredundant protein sequences database excluding Mycobacterium (taxid: 1763) organisms (BLAST E-value of e−5).41 The sequences of related CA domains were aligned using the NCBI Constraint-based Multiple Alignment Tool (COBALT).42 Next, CA domains were sorted based on the number of amino acid residues in the ATP-lid/F-box region, which was defined as the amino acids between the G1-and G2-box. Finally, a sequence logo plot was generated using WebLogo to analyze the conservation of amino acid residues in the homology boxes of CA domain sequences.43

Native Gel Electrophoresis.

DosS DHp-CA (15.7 μM) and DosS CA (25 μM) solutions without and with 0.075, 1, or 5 mM AMP-PNP concentrations were prepared in Native-PAGE Sample Buffer (Invitrogen) and allowed to equilibrate for 60 min. The gel tank was filled with tris-glycine pH 8.8 running buffer, and the wells of a 12% polyacrylamide gel were filled with 15 μL of each sample. A voltage of 150 V was applied for 40 min. The gel was stained with coomassie blue prior to imaging.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

To obtain a molecular understanding of the ATP-binding site in DosS, we performed a shotgun screen and identified crystallization conditions for WT DosS CA. Consistent with previous structural studies on a DosS CA variant,16 successful crystallization of WT DosS CA required 10 mM Zn2+, and the resulting protein crystals diffracted at 1.5 Å resolution. The WT DosS CA structure shows a Zn2+ in the ATP binding pocket coordinated to H507, D529, and E537 residues as well as a water molecule H-bonded to the carbonyl oxygen atom of V505 in a distorted tetrahedral geometry (Figure 2a). Among these, D529 is a highly conserved aspartate residue in the G1-box and is considered as the primary site of interaction between HKs and ATP’s N6 amino group. At the same time, Zn2+ coordination to the E537 residue in the ATP-lid may hinder conformational restructuring required for ATP binding. To investigate such effects, we performed MD simulations of the DosS CA in the presence and absence of Zn2+. We tracked the distance variation between the Cα’s of H507 and E537 residues throughout the course of the MD simulations. Residues H507 and E537 are present on loops 1 and 2 in the DosS CA structure (Figure S4a), and the distance between their Cα’s provides a measure of the openness of the ATP-lid. Temporal variations in this distance also provide a measure of ATP-lid flexibility. The Cα distance stays nearly constant at 9–10 Å for the Zn2+ bound CA structure suggesting low conformational flexibility of the protein and a relatively closed pocket in the presence of Zn2+ (Figure 2b blue trace). However, when Zn2+ is removed, we observe that the Cα distance rapidly increases up to 12 Å and varies from 12.5 to 9.5 Å over the 300 ns simulation time suggesting a significantly open ATP pocket and enhanced lid flexibility (Figure 2b black trace and Figure 2c).

In order to experimentally probe the influence of Zn2+ on ATP-lid flexibility and ATP binding to DosS CA, we conducted detailed ITC-based binding affinity studies of a non-hydrolyzable ATP analog, adenylyl-imidodiphoshate (AMP-PNP)44 to DosS CA. We began by titrating AMP-PNP to WT DosS CA in the absence of any Zn2+ and observed an exothermic heat profile indicative of an enthalpically driven binding interaction between the nucleotide and DosS CA (Figure S5). Using a single site binding equation to fit the heat evolved per mole of added ligand vs ligand-to-protein molar ratio, we extracted various parameters including binding affinity (Kd = 53 ± 13 μM), goodness of fit (c value = 6.2), maximal heat released (ΔHmax = −12.4 kcal/mol), and binding stoichiometry (n = 0.79) for the interaction between DosS CA and AMP-PNP. The Kd value of 53 ± 13 μM for AMP-PNP binding to DosS CA is comparable to other HKs such as HK853 and Spo0B (Table S2).45,46 This suggests that DosS CA would be completely bound to ATP under physiologically relevant ATP concentrations (1–5 mM) in bacteria and confutes claims from previous work that DosS CA by itself is unable to bind ATP.16,21 To probe the influence of Zn2+ on binding of the nucleotide to DosS CA, we also conducted ITC titrations of AMP-PNP to DosS CA in the presence of varied Zn2+ concentrations. Cells typically have all of their Zn2+ tightly bound to proteins and other cofactors with only femtomolar concentrations of free Zn2+.47,48 Our results show that even at 10 nM Zn2+ concentrations, the binding of AMP-PNP to DosS CA remains largely unaltered (Kd = 61 μM, n = 0.73) indicating negligible effect (Figure S6). We only observed competitive inhibition of AMP-PNP binding to DosS CA at exceedingly high Zn2+ concentrations of 210 μM (Figure 2d purple curve, Kd = 162 μM, n = 0.69) and 1.4 mM (Figure 2d blue curve, Kd = 402 μM, n = 0.32) (Figure S7). In addition to the diminished binding affinity, a significant decrease in binding stoichiometry is indicative of progressive enzyme deactivation at millimolar Zn2+ concentrations, which are relevant to WT DosS CA crystallization conditions. Nevertheless, the binding of Zn2+ to DosS CA reveals that the ATP binding pocket of DosS CA can provide a tetrahedral coordination environment for other divalent metals, as well. The preferred coordination geometry of physiologically relevant divalent transition metals in proteins are tetrahedral for Zn2+, octahedral for Co2+ and Ni2+, and square planar for Cu2+.49 Co2+ has been extensively used as a mimic of Zn2+ and has also been found to display tetrahedral coordination in a few proteins. We conducted ITC studies of ANP-PNP binding to DosS CA in the presence of 1.4 mM Co2+ (Figures S8a and S9a) which reveal that ANP-PNP binding to DosS CA is not impaired (Kd = 32 μM) by the presence of millimolar Co2+ suggesting that Co2+ does not bind to the ATP pocket at these concentrations. Beyond transition metals that are tightly regulated in cells, divalent metals like Ca2+ are physiologically present at high millimolar concentrations.50 Again, ANP-PNP binding to DosS CA in the presence of 1.4 mM Ca2+ (Figures S8b and S9b) is not impaired (Kd = 47 μM) by millimolar Ca2+. In summary, among physiologically relevant divalent metals, only Zn2+ prefers the required tetrahedral geometry and can bind most effectively to the ATP pocket of DosS CA, albeit at nonphysiological millimolar concentrations.

A closer examination of the AlphaFold model (Figure 2e) and the DesK homologue (Figure S10) of DosS CA compared to its structure crystallized under millimolar Zn2+ concentrations reveals that a key N-box α helix turn (residues N503–H507) of the ATP pocket manifests as a random coil in the Zn2+-coordinated protein crystal structure. CD can be used to detect such changes in the protein secondary structure. In particular, helix-to-coil transitions have been extensively studied using CD and are characterized by a reduction in the α helix-related dip at 221 nm.51 We conducted comprehensive CD studies of DosS CA under zinc-free and 10 mM Zn2+ conditions (Figure 2f black and blue curves, respectively). As anticipated, we observe signatures consistent with a helix-to-coil transition in the presence of Zn2+ highlighted by ~3% reduction in the dip at 221 nm. Although these are small yet detectable changes in CD spectrum, the magnitude correlates with the random coil transition of a single turn of an α helix in DosS CA, which constitutes ~7% of helical content in the protein (Figure S4). These findings suggest that the tetrahedral coordination of Zn2+ to residues in the ATP pocket, and more specifically to H507, drives a random coil transition of a key N-box helix turn, presenting itself as an artifact in the protein crystal structure that is physiologically irrelevant. In conclusion, these studies demonstrate that the ATP-lid of DosS CA has significant flexibility, ATP can effectively bind to DosS CA, and the AlphaFold model likely presents a physiologically relevant representation of DosS CA as compared to the crystallized Zn2+-bound structure.

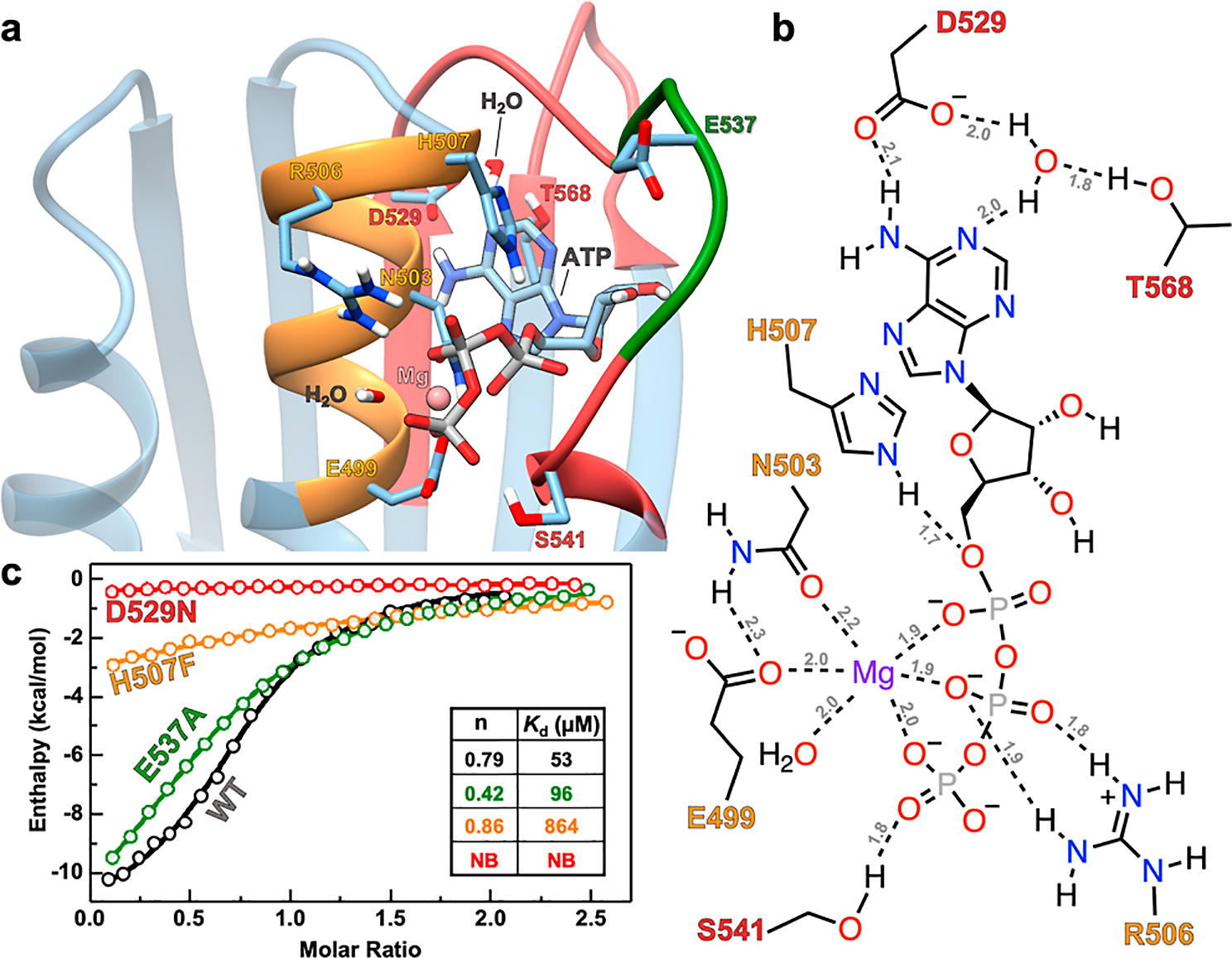

Next, we performed MD simulations on the AlphaFold model of DosS CA using ATP coordinates taken from its superposition to the homologous ATP-bound DesK crystal structure.2 The simulations showed that ATP remained in DosS CA’s ATP pocket for >100 ns of simulation time (Figure 3a) and its placement in the pocket resembled that of ATP-bound crystal structures of PhoQ and DesK (Figure S11). The simulated structure captured several characteristic interactions between ATP and residues in the G- and N-boxes of the DosS CA (Figure 3a). For instance, D529 in the G1-box and T568 in the G3-box interacted with ATP’s adenine ring. D529 formed an H-bond to N6 of adenine and, along with T568, positioned a water molecule to H-bond with N1 of adenine. Furthermore, S541 in the G2-box formed an H-bond with the γ-phosphate. Moving to the N-box, H507 formed H-bonds to the oxo groups of the α- and β-phosphates while R506 formed H-bonds to the oxo groups of the β- and γ-phosphates. Additionally, the carboxylate of E499 and the carbonyl of N503 also coordinated to the Mg2+ cation associated with ATP. We found no interactions between ATP and residues on the ATP-lid. We compared these observations with simulations of ATP docked to the Zn2+-removed DosS CA crystal structure and found that the random coil transition of an N-box α helix turn results in an unusual (out-of-pocket) placement of ATP that only interacts with D529 and R506 residues (Figure S12). To further assess the physiologically relevant mode of ATP binding to DosS CA, we conducted detailed ITC-based binding affinity studies of AMP-PNP to DosS CA variants with selected residues mutated (Figure S13). We began with the E537A variant in which the Zn2+-coordinating glutamate on the ATP-lid that is responsible for the closed-lid crystal structure was mutated to an alanine. ITC studies revealed only a slightly weakened binding affinity of 96 μM (Figure 3c, green curve) compared to that of WT DosS CA (Figure 3c, black curve). The lack of any affinity enhancement despite mutation of the ATP-lid residue responsible for the closed state in the presence of Zn2+ further confirms that the short ATP-lid does not hinder ATP binding. Moving on to the D529N variant (Figure 3c, red curve), which corresponds to a mutation of the adenine-binding aspartate in the G1-box to an asparagine, we observed a complete loss of AMP-PNP binding capacity. This is expected, as D529 is a highly conserved aspartate residue that binds to the adenine moiety of ATP across different HK types as observed in both our MD simulations that utilized the AlphaFold structure (Figure 3b) and the Zn2+-removed crystal structure (Figure S12). Focusing on the H507F variant, which corresponds to a mutation of the N-box histidine to phenylalanine, we observed a 16-fold weakening of AMP-PNP binding affinity (Figure 3c, orange curve), confirming the N-box H507 residue to be important for ATP binding. We note that H507 formed an H-bond with the oxo groups of the α- and β-phosphates in MD simulations that employed the AlphaFold model of DosS CA (Figure 3b) but was non-interacting in MD simulations that employed the DosS CA crystal structure (Figure S12). We believe that the non-interaction is due to the random coil manifestation of the N-box helix turn containing residues N503–H507, which orients the residues in such a way that only R506 can participate in ATP binding. Consequently, these ITC studies further validate the MD-based ATP-binding pose obtained using the AlphaFold model and highlight artifacts in the Zn2+-containing crystal structure. Overall, our computational modeling and biophysical studies demonstrate that the ATP pocket in DosS CA can bind ATP with affinities comparable to those of prototypical HKs. Beyond DosS CA, we also investigated the DosS DHp-CA construct (Figure 4a) that has been previously suggested to possess enhanced ATP affinity due to interdomain DHp/CA interactions. We expressed and purified the DosS DHp-CA construct and measured its affinity to AMP-PNP using ITC (Kd = 51 ± 6 μM) that reveal relatively unchanged affinity values when DosS CA is conjugated to the DHp domain (Figures 4b, S13 and S14). Our studies show that DosS CA by itself can bind ATP and DHp/CA interactions do not modulate ATP binding in a manner that is physiologically significant.

Figure 3.

(a) MD simulated structure of ATP bound to the AlphaFold model of DosS CA. (b) Schematic showing molecular interactions between DosS CA residues and ATP from MD simulations. H-bonds are indicated with dashed lines, and the distances (in Angstroms) are labeled in gray. Bond distances and angles are not to scale. The color of residue labels in parts (a,b) matches that of the boxes to which they belong. Orange is for the N-box, red is for the G-box, and green is for the ATP-lid. (c) ITC titrations showing the ATP analogue (AMP-PNP) binding affinity for WT (black), E537A (green), D529N (red), and H507F (orange) DosS CA variants. Inset shows a table with Kd and n values for these variants. No binding is abbreviated as NB.

Figure 4.

(a) Schematic showing various domains in DosS. (b) ITC titration data of DosS CA (black) and DosS DHp-CA (light blue) with AMP-PNP. Inset shows a table with Kd and n values for CA and DHp-CA.

Having demonstrated that DosS CA is capable of binding ATP with an affinity comparable to prototypical HKs with F-boxes and long ATP-lids, we set out to identify if other DosS-like proteins that lack an F-box and possess shorter ATP-lids are widespread. To this end, we searched the NCBI database for nonredundant proteins and found 5000 proteins homologous to DosS CA. We chose top 3000 sequences that made the most significant match with DosS CA based on their expect value (<1 × 10−6) and aligned their ATP-lids using the COBALT tool. Notably, we observed that the six amino acid lid-length was the most common among the homologous proteins (n = 2523), with much fewer proteins exhibiting five (n = 7), seven (n = 362), eight (n = 24), and nine (n = 72) amino acids in their lids (Figure 5a). Moreover, only 12 of the top 3000 DosS CA-type proteins displayed a lid with 10–27 amino acids. Next, we evaluated the sequence homology of the 3000 homologous proteins with varied amino acid lid sizes at the N-box, G-box, and ATP-lid residues. A LOGO plot analysis revealed strong conservation of residues E499, N503, R506, and H507 in the N-box (Figure 5b), and residues D529, G531, and G533 in the G1-box (Figure 5c). Furthermore, we found significant conservation of S541 in G2-box and T568 in G3-box of these 3000 homologous proteins (Figure S15). Notably, all the residues that showed H-bonding and ionic interactions in MD simulations of the ATP-bound AlphaFold DosS CA model were conserved in a large majority of the 3000 homologous proteins. Additionally, these proteins showed little sequence homology in their ATP-lid regions beyond a conserved proline which could be important for stabilizing/kinking the lid structure (Figure S16). Overall, our bioinformatics studies reveal the ubiquitous presence of short ATP-lids containing less than 10 residues in 2988 bacterial kinases and ATPases and suggest that such features do not impede ATP association in these proteins.

Figure 5.

(a) Bar graph demonstrating the variation in the number of ATP-lid residues in 2988 proteins that are homologous to the DosS CA domain. Logo plots representing the frequency and conservation of amino acids at each position of the (b) N box and (c) G1 box of 3000 proteins homologous to the DosS CA domain. The height of the letter stacks indicates conservation of amino acids at each position, while the height of letters within a stack represents the frequency of an amino acid at each position. Blank spaces in the sequence alignment indicate a low conservation of amino acids at these positions. Positions with dashed lines represent gaps in the DosS CA primary sequence.

CONCLUSIONS

Our computational modeling and biophysical studies demonstrate that the ATP pocket in DosS CA is capable of binding ATP with an affinity comparable to that of other prototypical HKs with F-boxes and longer ATP-lids. We also show that DosS CA by itself is able to bind ATP and that DHp/CA interactions do not modulate ATP binding in a manner that is physiologically significant. MD simulations of DosS CA in the presence and absence of Zn2+ illustrate that the ATP-lid has substantial flexibility in the absence of Zn2+ and that the AlphaFold model is likely providing a physiologically relevant representation of DosS CA as compared to the crystallized Zn2+-bound structure. Our ITC studies and bioinformatics investigations of homologous proteins further corroborate the MD-based ATP-binding pose obtained via the AlphaFold model. Our findings underscore potential artifacts such as the random coil transition of an important N-box α helix turn in the Zn2+-bound structure of DosS CA crystallized in the presence of excessive Zn2+. This highlights the necessity of being cognizant of possible artifacts that can arise in the crystallization of proteins, particularly when parasitic elements employed for crystallization appear at active site positions. Consequently, it conveys the importance of executing comprehensive biophysical, computational, and functional studies to validate the physiological relevance of the static, average structure of proteins obtained from diffraction experiments. Ultimately, our findings show that DosS CA-like domains are ubiquitous in bacterial species and that ATP binding is possible in CA domains of kinases in the absence of an F-box and a long ATP-lid. DosS CA with an AMP-PNP Kd of 53 μM is almost always bound to ATP in bacterial environments where the free ATP concentration is estimated to be 1–5 mM. From a signaling perspective, our studies indicate that ATP binding to DosS CA is unlikely to be a regulatory factor in the autophosphorylation reaction and subsequent signaling cascade.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Regents of the University of Minnesota and NIH NIGMS grant R35GM138277 (to A.B.-D.) and R35GM118047 (to H.A.). E.S. was supported by NIH Chemical Biology Training Grant T32GM132029. X-ray diffraction data were collected at the Northeastern Collaborative Access Team beamlines, which are funded by the NIH (P30 GM124165). The Pilatus 6M detector on 24-ID-C beamline is funded by a NIH-ORIP HEI grant (S10 RR029205).

ABBREVIATIONS

- AMP-PNP

adenylyl imidodiphosphate

- BLAST

basic local alignment search tool

- CA

catalytic ATP-binding domain

- CD

circular dichroism

- COBALT

constraint-based alignment tool

- DHp

dimerization and histidine phosphotransfer domain

- HK

histidine kinase

- ITC

isothermal titration calorimetry

- K d

dissociation constant

- Mtb

Mycobacterium tuberculosis

- RR

response regulator

- TCS

two-component system

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.biochem.3c00306.

Crystallization data collection and refinement statistics; dissociation constants of nucleotides to ATP-binding proteins; schematic of a generic two component system signal transduction pathway; COBALT alignment of HK CA domain homology boxes; SDS-PAGE analysis of DosS CA and its variants; DosS CA structure with labeled alpha helices and beta strands; ITC titration data of AMP-PNP into DosS CA and DosS DHp-CA in the presence of Zn2+ and other metals; structural comparisons of DosS CA crystal structure, AlphaFold, and homology models; comparisons of ATP-bound CA domains for various proteins; bioinformatic studies of G2, G3, and F boxes in HK CA domains; and native gel electrophoresis with DosS CA and DosS DHp-CA (PDF)

Accession Codes

This work discusses three different histidine kinases with UniProt IDs as—DosS: P9WGK3, PhoQ: P23837, and DesK: O34757.

Complete contact information is available at: https://pubs.acs.org/10.1021/acs.biochem.3c00306

Contributor Information

Grant W. Larson, Department of Chemistry, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota 55455, United States

Peter K. Windsor, Department of Chemistry, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota 55455, United States

Elizabeth Smithwick, Department of Chemistry, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota 55455, United States.

Ke Shi, Department of Biochemistry, Molecular Biology, and Biophysics, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota 55455, United States.

Hideki Aihara, Department of Biochemistry, Molecular Biology, and Biophysics, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota 55455, United States.

Anoop Rama Damodaran, Department of Chemistry, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota 55455, United States.

Ambika Bhagi-Damodaran, Department of Chemistry, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota 55455, United States.

REFERENCES

- (1).Jacob-Dubuisson F; Mechaly A; Betton JM; Antoine R Structural Insights into the Signalling Mechanisms of Two-Component Systems. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2018, 16 (10), 585–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Bhate MP; Molnar KS; Goulian M; DeGrado WF Signal Transduction in Histidine Kinases: Insights from New Structures. Structure 2015, 23 (6), 981–994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Buschiazzo A; Trajtenberg F Two-Component Sensing and Regulation: How Do Histidine Kinases Talk with Response Regulators at the Molecular Level? Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2019, 73 (1), 507–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Throup JP; Koretke KK; Bryant AP; Ingraham KA; Chalker AF; Ge Y; Marra A; Wallis NG; Brown JR; Holmes DJ; Rosenberg M; Burnham MKR A Genomic Analysis of Two-Component Signal Transduction in Streptococcus Pneumoniae. Mol. Microbiol. 2000, 35 (3), 566–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Ghosh M; Wang LC; Huber RG; Gao Y; Morgan LK; Tulsian NK; Bond PJ; Kenney LJ; Anand GS Engineering an Osmosensor by Pivotal Histidine Positioning within Disordered Helices. Structure 2019, 27 (2), 302–314.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Wayne LG; Sohaskey CD Nonreplicating Persistence of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2001, 55, 139–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Sousa EHS; Tuckerman JR; Gonzalez G; Gilles-Gonzalez M-A DosT and DevS Are Oxygen-Switched Kinases in Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. Protein Sci. 2007, 16 (8), 1708–1719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Dasgupta N; Kapur V; Singh KK; Das TK; Sachdeva S; Jyothisri K; Tyagi JS Characterization of a Two-Component System, DevR-DevS, of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. Tuber. Lung Dis. 2000, 80 (3), 141–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Park HD; Guinn KM; Harrell MI; Liao R; Voskuil MI; Tompa M; Schoolnik GK; Sherman DR Rv3133c/DosR Is a Transcription Factor That Mediates the Hypoxic Response of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. Mol. Microbiol. 2003, 48 (3), 833–843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Ioanoviciu A; Yukl ET; Moënne-Loccoz P; Ortiz De Montellano PR DevS, a Heme-Containing Two-Component Oxygen Sensor of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. Biochemistry 2007, 46 (14), 4250–4260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Sardiwal S; Kendall SL; Movahedzadeh F; Rison SCG; Stoker NG; Djordjevic S A GAF Domain in the Hypoxia/NO-Inducible Mycobacterium Tuberculosis DosS Protein Binds Haem. J. Mol. Biol. 2005, 353 (5), 929–936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Gopinath V; Raghunandanan S; Gomez RL; Jose L; Surendran A; Ramachandran R; Pushparajan AR; Mundayoor S; Jaleel A; Kumar RA Profiling the Proteome of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis during Dormancy and Reactivation. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2015, 14 (8), 2160–2176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Lupoli TJ; Fay A; Adura C; Glickman MS; Nathan CF Reconstitution of a Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Proteostasis Network Highlights Essential Cofactor Interactions with Chaperone DnaK. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2016, 113 (49), E7947–E7956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Williams MT; Yee E; Larson GW; Apiche EA; Rama Damodaran A; Bhagi-Damodaran A Metalloprotein Enabled Redox Signal Transduction in Microbes. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2023, 76, 102331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Sivaramakrishnan S; Ortiz de Montellano P The DosS-DosT/DosR Mycobacterial Sensor System. Biosensors 2013, 3 (3), 259–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Cho HY; Lee YH; Bae YS; Kim E; Kang BS Activation of ATP Binding for the Autophosphorylation of DosS, a Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Histidine Kinase Lacking an ATP Lid Motif. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288 (18), 12437–12447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Dutta R; Inouye M GHKL, an Emergent ATPase/Kinase Superfamily. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2000, 25 (1), 24–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Marina A; Mott C; Auyzenberg A; Hendrickson WA; Waldburger CD Structural and Mutational Analysis of the PhoQ Histidine Kinase Catalytic Domain. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276 (44), 41182–41190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Trajtenberg F; Graña M; Ruétalo N; Botti H; Buschiazzo A Structural and Enzymatic Insights into the ATP Binding and Autophosphorylation Mechanism of a Sensor Histidine Kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285 (32), 24892–24903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Zhu Y; Inouye M The Role of the G2 Box, a Conserved Motif in the Histidine Kinase Superfamily, in Modulating the Function of EnvZ. Mol. Microbiol. 2002, 45 (3), 653–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Mempin R; Tran H; Chen C; Gong H; Kim Ho K; Lu S Release of Extracellular ATP by Bacteria during Growth. BMC Microbiol. 2013, 13 (1), 301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Wilson RH; Chatterjee S; Smithwick ER; Dalluge JJ; Bhagi-Damodaran A Role of Secondary Coordination Sphere Residues in Halogenation Catalysis of Non-Heme Iron Enzymes. ACS Catal. 2022, 12 (17), 10913–10924. [Google Scholar]

- (23).Kabsch W Automatic Processing of Rotation Diffraction Data from Crystals of Initially Unknown Symmetry and Cell Constants. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 1993, 26 (6), 795–800. [Google Scholar]

- (24).McCoy AJ; Grosse-Kunstleve RW; Adams PD; Winn MD; Storoni LC; Read RJ Phaser Crystallographic Software. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2007, 40 (4), 658–674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Fisher OS; Liu W; Zhang R; Stiegler AL; Ghedia S; Weber JL; Boggon TJ Structural Basis for the Disruption of the Cerebral Cavernous Malformations 2 (CCM2) Interaction with Krev Interaction Trapped 1 (KRIT1) by Disease-Associated Mutations. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290 (5), 2842–2853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Fisher OS; Kenney GE; Ross MO; Ro SY; Lemma BE; Batelu S; Thomas PM; Sosnowski VC; DeHart CJ; Kelleher NL; Stemmler TL; Hoffman BM; Rosenzweig AC Characterization of a Long Overlooked Copper Protein from Methane- and Ammonia-Oxidizing Bacteria. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9 (1), 4276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Emsley P; Lohkamp B; Scott WG; Cowtan K Features and Development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. D: Biol. Crystallogr. 2010, 66 (4), 486–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Liebschner D; Afonine PV; Baker ML; Bunkóczi G; Chen VB; Croll TI; Hintze B; Hung L-W; Jain S; McCoy AJ; Moriarty NW; Oeffner RD; Poon BK; Prisant MG; Read RJ; Richardson JS; Richardson DC; Sammito MD; Sobolev OV; Stockwell DH; Terwilliger TC; Urzhumtsev AG; Videau LL; Williams CJ; Adams PD Macromolecular Structure Determination Using X-Rays, Neutrons and Electrons: Recent Developments in Phenix. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. D: Biol. Crystallogr. 2019, 75 (10), 861–877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Pettersen EF; Goddard TD; Huang CC; Couch GS; Greenblatt DM; Meng EC; Ferrin TE UCSF Chimera-A Visualization System for Exploratory Research and Analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 2004, 25 (13), 1605–1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Case DA; Aktulga HM; Belfon K; Ben-Shalom IY; Berryman JT; Brozell SR; Cerutti DS; Cheatham TE; Cisneros GA; Cruzeiro VWD; Darden TA; Duke RE; Giambasu G; Gilson MK; Gohlke H; Harris R; Izadi S; Izmailov SA; Kosavajhala K; Kaymak MC; King E; Kovalenko T; Kurtzman T; Lee TS; LeGrand S; Li P; Lin C; Liu J; Luchko T; Luo R; Machado M; Man V; Manathunga M; Merz KM; Miao Y; Mihailovskii O; Monard G; Nguyen H; O’Hearn KA; Onufriev A; Pan F; Pantano S; Qi R; Rahnamoun A; Roe DR; Roitberg A; Sagui C; Schott-Verdugo S; Shajan A; Shen J; Simmering CL; Skrynnikov NR; Smith J; Swails J; Walker RC; Wang J; Wang J; Wei H; Wolf RM; Wu X; Xiong Y; Xue Y; York DM; Zhao S; Kollman PA Amber 22; University of California: San Francisco, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- (31).Maier JA; Martinez C; Kasavajhala K; Wickstrom L; Hauser KE; Simmerling C Ff14SB: Improving the Accuracy of Protein Side Chain and Backbone Parameters from Ff99SB. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2015, 11 (8), 3696–3713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Li P; Roberts BP; Chakravorty DK; Merz KM Rational Design of Particle Mesh Ewald Compatible Lennard-Jones Parameters for + 2 Metal Cations in Explicit Solvent. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2013, 9 (6), 2733–2748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Joung IS; Cheatham TE Determination of Alkali and Halide Monovalent Ion Parameters for Use in Explicitly Solvated Biomolecular Simulations. J. Phys. Chem. B 2008, 112 (30), 9020–9041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Li Z; Song LF; Li P; Merz KM Systematic Parametrization of Divalent Metal Ions for the OPC3, OPC, TIP3P-FB, and TIP4P-FB Water Models. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2020, 16 (7), 4429–4442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Meagher KL; Redman LT; Carlson HA Development of Polyphosphate Parameters for Use with the AMBER Force Field. J. Comput. Chem. 2003, 24 (9), 1016–1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Zgarbová M; Šponer J; Otyepka M; Cheatham TE; Galindo-Murillo R; Jurečka P Refinement of the Sugar-Phosphate Backbone Torsion Beta for AMBER Force Fields Improves the Description of Z- and B-DNA. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2015, 11 (12), 5723–5736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Jumper J; Evans R; Pritzel A; Green T; Figurnov M; Ronneberger O; Tunyasuvunakool K; Bates R; Žídek A; Potapenko A; Bridgland A; Meyer C; Kohl SAA; Ballard AJ; Cowie A; Romera-Paredes B; Nikolov S; Jain R; Adler J; Back T; Petersen S; Reiman D; Clancy E; Zielinski M; Steinegger M; Pacholska M; Berghammer T; Bodenstein S; Silver D; Vinyals O; Senior AW; Kavukcuoglu K; Kohli P; Hassabis D Highly Accurate Protein Structure Prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 2021, 596 (7873), 583–589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Hosseinzadeh P; Watson PR; Craven TW; Li X; Rettie S; Pardo-Avila F; Bera AK; Mulligan VK; Lu P; Ford AS; Weitzner BD; Stewart LJ; Moyer AP; Di Piazza M; Whalen JG; Greisen PJ; Christianson DW; Baker D Anchor Extension: A Structure-Guided Approach to Design Cyclic Peptides Targeting Enzyme Active Sites. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12 (1), 3384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Olivieri C; Walker C; Karamafrooz A; Wang Y; Manu VS; Porcelli F; Blumenthal DK; Thomas DD; Bernlohr DA; Simon SM; Taylor SS; Veglia G Defective Internal Allosteric Network Imparts Dysfunctional ATP/Substrate-Binding Cooperativity in Oncogenic Chimera of Protein Kinase A. Commun. Biol. 2021, 4 (1), 321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Grossoehme NE; Mulrooney SB; Hausinger RP; Wilcox DE Thermodynamics of Ni2+, Cu2+, and Zn2+ Binding to the Urease Metallochaperone UreE. Biochemistry 2007, 46 (37), 10506–10516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Altschul SF; Gish W; Miller W; Myers EW; Lipman DJ Basic Local Alignment Search Tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990, 215 (3), 403–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Papadopoulos JS; Agarwala R COBALT: Constraint-Based Alignment Tool for Multiple Protein Sequences. Bioinformatics 2007, 23 (9), 1073–1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Crooks GE; Hon G; Chandonia J-M; Brenner SE WebLogo: A Sequence Logo Generator: Figure 1. Genome Res. 2004, 14 (6), 1188–1190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Yount RG; Babcock D; Ballantyne W; Ojala D Adenylyl Imidiodiphosphate, an Adenosine Triphosphate Analog Containing a P-N-P Linkage. Biochemistry 1971, 10 (13), 2484–2489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Zhou Y; Huang L; Ji S; Hou S; Luo L; Li C; Liu M; Liu Y; Jiang L Structural Basis for the Inhibition of the Autophosphorylation Activity of HK853 by Luteolin. Molecules 2019, 24 (5), 933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Mattoo AR; Saif Zaman M; Dubey GP; Arora A; Narayan A; Jailkhani N; Rathore K; Maiti S; Singh Y Spo0B of Bacillus Anthracis - A Protein with Pleiotropic Functions. FEBS J. 2008, 275 (4), 739–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Outten CE; O’Halloran T v. Femtomolar Sensitivity of Metalloregulatory Proteins Controlling Zinc Homeostasis. Science 2001, 292, 2488–2492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Marvin RG; Wolford JL; Kidd MJ; Murphy S; Ward J; Que EL; Mayer ML; Penner-Hahn JE; Haldar K; O’Halloran TV Fluxes in “Free” and Total Zinc Are Essential for Progression of Intraerythrocytic Stages of Plasmodium Falciparum. Chem. Biol. 2012, 19 (6), 731–741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Rulíšek L; Vondrášek J Coordination Geometries of Selected Transition Metal Ions (Co2+, Ni2+, Cu2+, Zn2+, Cd2+, and Hg2+) in Metalloproteins. J. Inorg. Biochem. 1998, 71 (3–4), 115–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Bhagi-Damodaran A; Lu Y The Periodic Table’s Impact on Bioinorganic Chemistry and Biology’s Selective Use of Metal Ions. The Periodic Table II; Springer: Cham, 2019; Vol. 182, pp 153–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Gans PJ; Lyu PC; Manning MC; Woody RW; Kallenbach NR The Helix-Coil Transition in Heterogeneous Peptides with Specific Side-Chain Interactions: Theory and Comparison with CD Spectral Data. Biopolymers 1991, 31 (13), 1605–1614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.