Abstract

Background

The Middle East and North Africa (MENA) offer optimal climatic conditions for tick reproduction and dispersal. Research on tick-borne pathogens in this region is scarce. Despite recent advances in the characterization and taxonomic explanation of various tick-borne illnesses affecting animals in Egypt, no comprehensive examination of TBP (tick-borne pathogen) statuses has been performed. Therefore, the present study aims to detect the prevalence of pathogens harbored by ticks in Egypt.

Methodology/Principal findings

A four-year PCR-based study was conducted to detect a wide range of tick-borne pathogens (TBPs) harbored by three economically important tick species in Egypt. Approximately 86.7% (902/1,040) of the investigated Hyalomma dromedarii ticks from camels were found positive with Candidatus Anaplasma camelii (18.8%), Ehrlichia ruminantium (16.5%), Rickettsia africae (12.6%), Theileria annulata (11.9%), Mycoplasma arginini (9.9%), Borrelia burgdorferi (7.7%), Spiroplasma-like endosymbiont (4.0%), Hepatozoon canis (2.4%), Coxiella burnetii (1.6%) and Leishmania infantum (1.3%). Double co-infections were recorded in 3.0% (27/902) of Hy. dromedarii ticks, triple co-infections (simultaneous infection of the tick by three pathogen species) were found in 9.6% (87/902) of Hy. dromedarii ticks, whereas multiple co-infections (simultaneous infection of the tick by ≥ four pathogen species) comprised 12% (108/902). Out of 1,435 investigated Rhipicephalus rutilus ticks collected from dogs and sheep, 816 (56.9%) ticks harbored Babesia canis vogeli (17.1%), Rickettsia conorii (16.2%), Ehrlichia canis (15.4%), H. canis (13.6%), Bo. burgdorferi (9.7%), L. infantum (8.4%), C. burnetii (7.3%) and Trypanosoma evansi (6.6%) in dogs, and 242 (16.9%) ticks harbored Theileria lestoquardi (21.6%), Theileria ovis (20.0%) and Eh. ruminantium (0.3%) in sheep. Double, triple, and multiple co-infections represented 11% (90/816), 7.6% (62/816), and 10.3% (84/816), respectively in Rh. rutilus from dogs, whereas double and triple co-infections represented 30.2% (73/242) and 2.1% (5/242), respectively in Rh. rutilus from sheep. Approximately 92.5% (1,355/1,465) of Rhipicephalus annulatus ticks of cattle carried a burden of Anaplasma marginale (21.3%), Babesia bigemina (18.2%), Babesia bovis (14.0%), Borrelia theleri (12.8%), R. africae (12.4%), Th. annulata (8.7%), Bo. burgdorferi (2.7%), and Eh. ruminantium (2.5%). Double, triple, and multiple co-infections represented 1.8% (25/1,355), 11.5% (156/1,355), and 12.9% (175/1,355), respectively. The detected pathogens’ sequences had 98.76–100% similarity to the available database with genetic divergence ranged between 0.0001 to 0.0009% to closest sequences from other African, Asian, and European countries. Phylogenetic analysis revealed close similarities between the detected pathogens and other isolates mostly from African and Asian countries.

Conclusions/Significance

Continuous PCR-detection of pathogens transmitted by ticks is necessary to overcome the consequences of these infection to the hosts. More restrictions should be applied from the Egyptian authorities on animal importations to limit the emergence and re-emergence of tick-borne pathogens in the country. This is the first in-depth investigation of TBPs in Egypt.

Author summary

Molecular monitoring of ticks for pathogen nucleic acids is informative when used in the surveillance of diseases transmitted by ticks. In the view of the limited information of genetic aspects of either ticks or their pathogen burdens in Egypt, it is crucial to give more attention into this direction to overcome the consequences might happen due to the caused diseases. We investigated three tick species (Rhipicephalus rutilus, Rh. annulatus, and Hyalomma dromedarii). These ticks are well-established in Egypt, infesting dogs, sheep, cattle, and camel among other hosts. The ticks were screened for the presence of different bacterial and protozoan pathogens using PCR technique for four years. The findings showed a prevalence of bacterial agents overall the ticks, followed by the protozoans. Surprisingly, the ticks showed different degrees of co-infections along with single infections. The data provided in this study should be used as a base in the construction of the “One health approach” that is being adopted by the country to protect the lives of both humans and their companion animals.

Introduction

Egypt probably has the oldest record ever on ticks, as the ancient Egyptians have reported the occurrence of ticks and their infestations, documenting the incidence of tick fever in a figure of a hyaena-like animal’s head found in Dra Abn el-Nago, Western Thebes, dating back to the time of Hatshepsut-Thuthmosis III about 1500 B.C. [1]. Presently, the ticks identified in Egypt include approximately 52 tick species, including eight argasid species infesting birds, rodents, foxes, and hedgehogs [2–7] and 44 ixodid species belongs to the genera of Amblyomma, Haemaphysalis, Hyalomma, Ixodes, and Rhipicephalus. Apart from the exotic tick species found occasionally in Egypt, the actual fauna includes well-established Rh. sanguineus, Rh. annulatus, and Hy. dromedarii out of 15 Rhipicephalus species and 15 Hyalomma ticks [8]. Despite the global debate regarding Rh. sanguineus complex over the past decades, due to the morphological similarity and misidentification between all the species of this complex, molecular techniques have differentiated three distinguished mitochondrial lineages viz. temperate lineage, tropical lineage, and southeastern Europe lineage [9–12]. The ambiguous identities of these different lineages have been recently resolved through neotype designations of the temperate lineage to be the actual Rh. sanguineus [13], followed by a new identification of the tropical lineage to be Rh. linnaei [14,15], and the southeastern Europe lineage to be dealt with as Rh. rutilus [16].

Historically, trading routes connecting Africa, Europe, and Asia were being constructed through Egypt due to its strategic location. Egypt’s population (110 million) is notably increasing with anticipated population that is expected to be over 150 million in 2050, rearing and consuming more than 18 million animals in the area, including 5.4 million sheep; 5.1 million cattle, 4 million goats; 3.7 million water buffaloes, 120,000 camels, and 85,000 horses [17]. In view of the universal issues of food security and the rising frequency of undernourished individuals started in 2019, owing mostly to the COVID-19 pandemic [18], the Egyptian authorities were asked to embrace a One Health approach when developing and implementing livestock policies and investments, particularly when dealing with emerging and re-emerging animal diseases, including TBDs that, if left uncontrolled, might jeopardize the entire livestock sector’s development progression. Egypt is expected to grow by 65% in the next three decades. According to the United Nations Population Fund (UNPF), the country’s livestock and animal sector is crucial for its agricultural gross domestic product (GDP) and services, accounting for 40% of the country’s total GDP. However, Egypt faces challenges in providing sufficient meat and livestock products to its 110 million population, affecting its overall agricultural output. Ticks and the diseases they cause are key obstacles that prevent agricultural and animal growth in the country.

Ticks (Acari: Ixodida) are well-known for their diverse and wide capacity for pathogens that could be easily transmitted to their hosts. Although ticks cause direct damage to their hosts during the acquisition of their blood meals (damaging skin and allowing secondary infections to occur), a greater danger comes with their ability to transmit a huge variety of bacteria, viruses, protozoa, and filarial nematodes [19–25]. Tick-borne diseases (TBDs) are a significant constraint on global livestock industries and can result in annual losses amounting to billions of US dollars for farmers [26,27]. As vectors, ticks have grown in prominence among other arthropod groups capable of spreading more pathogens than any other group of invertebrates, causing significant diseases in animals and humans [28,29]. The geographic range of tick species is quickly and continuously expanding globally, probably due to ecological factors and climatic change, demographics, greater human travel, and global animal trafficking/exportations, leading to the revival and redistribution of infectious and zoonotic diseases [30]. In this context, there are two likely scenarios for the emergence and re-emergence of tick-borne diseases (TBDs) in Egypt, which are the migration routes of birds over the African-Eurasian flyways, and the importation of infected animals and their infesting ticks over the barriers of sub-Saharan countries and neighboring ones (Sudan, Libya, Somalia, Ethiopia, Chad, and Kingdom of Saudi Arabia) [31–34], harboring and spreading pathogens that have not been previously identified in the country. Despite the insignificant burden on human populations, cases of zoonotic pathogens in animals that can negatively impact on public health and quality of life, found in ticks and humans have been reported. Generally, human infections due to the TBPs in Egypt are usually underestimated, requiring extensive molecular surveillance to identify known and new pathogens [35]. Limited data from the available Egyptian records of TBP-suffering humans refers to four children in Giza Governorate diagnosed with tick paralysis [36], a couple of human babesiosis cases in Al-Minia Governorate [37,38], four children suffering from Lyme disease in Alexandria Governorate [39], and three human Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever (CCHF) cases in Cairo and Gharbia Governorates [40].

Although the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) offer favorable climates and circumstances for tick propagation and dispersion, studies on TBPs in this region are limited [41]. Moreover, despite recent breakthroughs in the characterization and taxonomic justification of numerous tick-borne diseases infecting animals in Egypt, no thorough investigation of TBP statuses has been conducted. In Egypt, scattered information regarding individual groups of TBPs is present, mostly relying on serological detection; however, phenotypic traits have limited value in identifying and delimiting species during microscopic examination [42,43]. Furthermore, TBDs’ symptoms frequently overlap and are widespread, making accurate diagnosis critical for proper treatment and control methods [44]. On the other hand, the emergence of molecular diagnostic tools has led to their increasingly widespread use in studying tick-borne agents due to their high sensitivity and accuracy [45–48]. The continuous advancements in molecular biology techniques have played a great role in the discovery of new species, strains, and genetic variants of microorganisms worldwide, leading to considerable improvements in TBPs’ detection and surveillance [49]. Given the scarcity of non-molecular data on TBDs in Egypt, further molecular research on this topic is required to build a robust dataset on the country’s status and develop appropriate preventative measures.

To effectively manage ticks and their borne-pathogens, comprehensive surveillance studies on circulating tick-borne pathogens in the Egyptian population, molecular diagnostic tools, and enhanced border inspections are necessary. The current study used molecular techniques (PCR-based) to screen for and genetically identify tick-borne pathogens (TBPs) in ticks infesting dromedary camels, cattle, dogs, and sheep from Egypt. This is the first comprehensive study regarding the identification at species level for TBPs circulating in Egypt.

Methods

Study location and tick collection

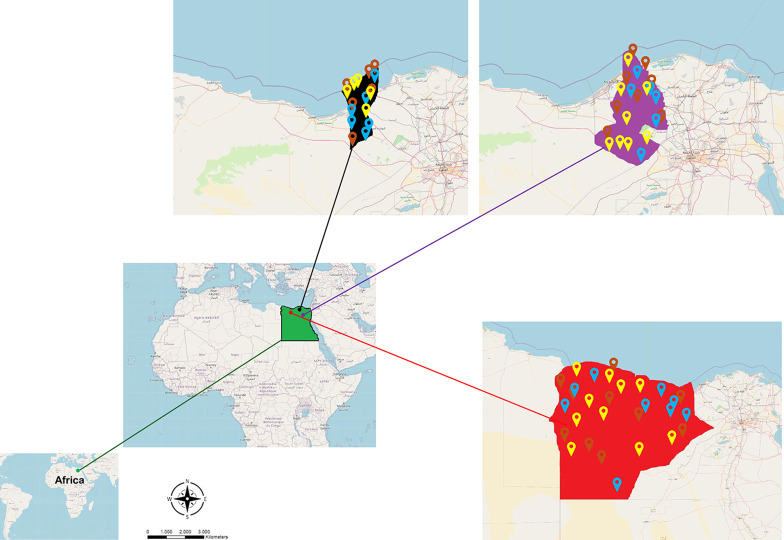

Egypt is a north African country with over 100 million people and 28 million livestock [50], extends between 22° N and 31.5° N and 25° E and 37° E to cover approximately 1 × 106 km2. The annual mean of temperature is between 16°C to 28.6°C with extremes of 5–30°C [51]. The country is divided into 27 governorates and five geographical territories viz. the Great Cairo (Cairo, Giza, and Shoubra El-Kheima), Middle Egypt (Giza, Beni-Suef, Fayoum, and Al-Minia), Middle Delta (Qualiobia, Menoufia, Gharbia, Dakahlia, Kafr Al-Shiekh, and Damietta), East Delta (Sharkia, Port Said, Ismailia, Suez, Siniai), West Delta (Alexandria, Behiera, Nubaria, and Marsa Matrouh), and Upper Egypt (Assuit, Sohag, Qena, Al-Wadi Al-Gadid, and Aswan) [52]. A total of 11,221 Semi and fully engorged adult ticks (females and males; 70%: 30% ratio) were collected between 2017 and 2021 from dromedary camels (2,267), cattle (3,010), dogs (3,355), and sheep (2,589) using tweezers. Tick specimens were collected from three North and North-western Egyptian governorates viz. Alexandria (31°12′0.3312′’N; 29° 55′7.4604′’E), Beheira (31°10′48.18′’N; 32°2′5.82′’E), and Marsa Matrouh (31°21′9.7596′’N; 27°15′18.972′’E) (Fig 1). Predominant tick species (over 95% of infestations on specific hosts) have only been considered in the current study (Hy. dromedarii represented > 96% of camel ticks, whereas ∼ 4% included Hy. excavatum, Hy. impeltatum and Hy. franchinii; Rh. rutilus represented ∼ 95% of the infested dogs and sheep, whereas only 5% were Rh. turanicus; Rh. annulatus were exclusively representing 100% of the ticks infesting cattle). Host-wise collected specimens of every collection trip were kept together based on their morphological characteristics in vials containing 70% ethanol for preservation purposes until further investigation, and data of host type, locality, date, and number of ticks were noted. A list of collected ticks in relation to their hosts is shown in S1 Table. Out of the collected ticks, a total of 3,940 valid specimens of all species were eventually considered and processed in our study to represent the entire tick populations based on their collection locality, collection date and season, host type, tick sex and activity (excluded specimens were due to obstacles of shredded ticks, transfer between countries (Egypt-India), low-yielded DNA specimens, and other biotechnological and sequencing issues).

Fig 1. Egypt’s map showing the tick collection spots and their distribution in the study area.

Green color refers to Egypt, black to Alexandria governorate, violet to Beheira governorate, and red to Marsa Matrouh governorate. Brown map marks refers to collection sites of Hyalomma dromedarii, light blue map marks to Rhipicephalus annulatus, and yellow map marks to Rhipicephalus rutilus. Open Street Map, which is licensed under an Open Database License ODbL 1.0, was used. The base layer was extracted here: https://www.openstreetmap.org/export. The terms and conditions of the copyright are provided here: https://www.openstreetmap.org/copyright. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0012185.

Identification of ticks

In our previous study, we identified and characterized the collected tick species at both morphological and molecular levels from brown dog ticks, Rhipicephalus sanguineus s.l. (Southeastern-Europe lineage) which was proposed later to be referred as Rhipicephalus rutilus (hereafter: Rh. rutilus), the Texas cattle tick, Rh. annulatus and the camel tick, Hyalomma dromedarii.

DNA extraction

DNA extraction was carried out using the DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the protocol for the purification of total DNA from individual tick species (Approximately 50% of the collected and valid specimens for each tick species). Briefly, the whole tick bodies were cut into pieces using a sterile scalpel blade and homogenized by micro pestles (Jainco Lab, Haryana, India), and DNA was extracted from the homogenate according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Two hundred μl of Buffer AL and 20 μl of proteinase K were added to the homogenate, and the suspension mixed thoroughly by vortexing using Spinix (Tarsons, Kolkata, India). The total genomic DNA was eluted in a final volume of 30 μl AE buffer, followed by incubation for one minute at room temperature and then centrifugation at room temperature for one minute at 6,000 xg. This last step was repeated with the eluate to increase the DNA yield.

The optical density at 260 and 280 nm was measured with a DNA-RNA calculator (NanoDrop ND-1000, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) to quantify DNA content and purity. Genomic DNA was dispensed in aliquots of 10 μl and kept frozen until use in PCR reactions. Prevalence ratios of detected pathogens were based on the results of screened 1,435 Rh. rutilus, 1,465 Rh. annulatus, and 1,040 Hy. dromedarii ticks.

Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR)

The oligonucleotide sets of primers used for the amplification of the target genes of every pathogen group, including Anaplasma spp., Babesia spp., Borrelia spp., Coxiella spp., Ehrlichia spp., Hepatozoon spp., Leishmania spp., Mycoplasma spp., Rickettsia spp., Theileria spp., Trypanosoma evansi, and Trypanosoma vivax are shown in Table 1. Every amplification was accompanied by a negative and positive control samples from the same pathogen group (Negative control contained all the PCR reaction components except the template DNA, whereas positive control contained all the PCR reaction components with known template DNA previously recognized from the same pathogen group). For each PCR reaction, 2 μl of 300–500 ng/ μl genomic DNA (gDNA) was used as the template in 50 μl reaction mixture containing 2 μl of each primer concentrated to 10 pmol (forward and reverse); 2 μl of dNTP mixture (2.5 mM); 5 μl of 10X PCR buffer; 0.5 μl of Takara Ex Taq polymerase (Takara Bio Inc., Kyoto, Japan); and 36.5 μl of distilled water. The reactions were conducted in GeneAmp PCR System 9700 fast thermal cycler (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) with specified conditions for each pathogen group. The obtained PCR products were run by agarose 1% gel electrophoresis later, and every pathogen group sample was loaded into the gel. DL 2,000 DNA marker was used as ladder (Takara Bio Inc., Kyoto, Japan). The bands were finally visualized using the Alpha Innotech AlphaImager EP Gel Imaging System (Bio-Techne, Connecticut, USA).

Table 1. Oligonucleotide sets of primers used to detect tick-borne pathogens in this study.

| Pathogen | Target gene | Primers | Sequence (5’-3’) | Annealing temperature (°C) | PCR mode | Amplicon size (bp) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anaplasma spp. | 16S rRNA | 16ANA-F 16SANA-R |

CAGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAGAACG GAGTTTGCCGGGACTTCTTCTGTA |

69 | Touch down: -0.5°C | 421 | [167] |

| Babesia/Theileria spp. | 18S rRNA | RIB19 RIB20 BabRumF BabRumR |

CGGGATCCAACCTGGTTGATCCTGC CCGAATTCCTTGTTACGACTTCTC ACCTCACCAGGTCCAGACAG GTACAAAGGGCAGGGACGTA |

54 | Nested | 430 | [168] |

| Theileria ovis | 18S RNA | TSst170F TSst670R TSsr250FN YSsr630RN |

TCGAGACCTTCGGGT TCCGGACATTGTAAAACAAA CGCGTCTTCGGATG AAAGACTCGTAAAGGAGCAA |

54 | Nested | 520 | [169] |

| Babesia bovis | 18S RNA | BoF BoR BoFN BoRN |

CACGAGGAAGGAACTACCGATGTTGA CCAAGGAGCTTCAACGTACGAGGTCA TCAACAAGGTACTCTATATGGCTACC CTACCGAGCAGAACCTTCTTCACCAT |

55 | Nested | 356 | [170] |

| Borrelia spp. | flaB | flaBF flaBR |

AACAGCTGAAGAGCTTGGAATG CTTTGATCACTTATCATTCTAATAGC |

55 | Normal | 350 | [171] |

| Borrelia burgdorferi | 5S-23S ribosomal RNA intergenic spacer region | 5S rRNA (rrf) 23S rRNA (rrl) BburgF BburgR |

CGACCTTCTTCGCCTTAAAGC TAAGCTGACTAATACTAATTACCC CTGCGAGTTCGCGGGAGA TCCTAGGCATTCACCATA |

59 | Nested | 226–266 | [172] |

| Coxiella spp. | 16S rRNA | Cox16SF1 Cox16SR2 Cox16SF2 Cox16SR1 |

CGTAGGAATCTACCTTRTAGWGG GCCTACCCGCTTCTGGTACAATT TGAGAACTAGCTGTTGGRRAGT ACTYYCCAACAGCTAGTTCTCA |

56 | Nested | 719–826 | [173] |

| Ehrlichia spp. | 16S rRNA | EHR16SD EHR16SR |

GGTACCYACAGAAGAAGTCC TAGCACTCATCGTTTACAGC |

53 | Normal | 345 | [174] |

| Ehrlichia ruminantium | pCS20 | AB130 AB129 AB129 AB128 |

RCTDGCWGCTTTYTGTTCAGCTAK TGATAACTTGGTGCGGGAAATCCTT TGATAACTTGGTGCGGGAAATCCTT ACTAGTAGAAATTGCACAATCTAT |

58 | Semi-nested | 279 | [175] |

| Hepatozoon spp. | 18S rRNA | HepF HepR |

ATACATGAGCAAAATCTCAAC CTTATTATTCCATGCTGCAG |

57 | Normal | 666 | [176] |

| Leishmania spp. | ITS1 | LITSR L5.8S |

CTGGATCATTTTCCGATG TGATACCACTTATCGCACTT |

53 | Normal | 300–350 | [177] |

| Mycoplasma/Spiroplasma spp. | 16S rRNA | fHF5 rHF6 |

AGCAGCAGTAGGGAATCTTCCAC TGCACCAACCTGTCACCTCGATAAC |

50 | Normal | 674 | [178] |

| Rickettsia spp. | 16S RNA | fD1 Rc16S-452n |

AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG AACGTCATTATCTTCCTTGC |

54 | Normal | 416 | [179] |

| Trypanosoma evansi | ITS1 | Te1F Te1R Te2F Te1R |

GCACAGTATGCAACCAAAAA GTGGTCAACAGGGAGAAAAT CATGTATGTGTTTCTATATG GTGGTCAACAGGGAGAAAAT |

56 | Semi-nested | 280 | [180] |

| Trypanosoma vivax | Cathepsin L | Tvi2 DTO156 |

GCCATCGCCAAGTACCTCGCGA TTAGAATTCCCAGGAGTTCTTGATGATCCAGTA |

56 | Normal | 177 | [181] |

Cases of multiple bands were run in a protocol of gel extraction with the help of QiAquick Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). The desired fragments of the expected sizes were extracted from the gel and processed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The purified DNA was re-analyzed on 1% gel as previously described to check the integrity of the samples.

DNA Sequence analysis

Amplified amplicons were sent to Bioserve Biotechnologies Pvt. Ltd. (Hyderabad, Telangana state, India) to perform the sequencing based on Sanger sequencing method (dideoxy sequencing or chain termination method) [53]. The protocol used for sequencing the final products started with using 2.5 μl of BigDye Terminator reagent mix (Version 3.1) (Applied Biosystems, California, USA) to be mixed with 1 μl of the template; 0.5 μl of primer; and 1 μl distilled water. In total, 5 μl reaction mixture were used for amplification with specified PCR conditions. The products were run on a Genetic Analyzer ABI3730XL (Applied Biosystems, California, USA). Sequences obtained from the sequence analyzer were analyzed using the GENERUNNER software.

The obtained nucleotide sequences were firstly assembled by the help of CAP3 online tool (http://doua.prabi.fr/software/cap3) (Pôle Rhône-Alpes de Bioinformatique Site Doua (PRABI-Doua), Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes, Lyon, France). The consensus contigs were then aligned and blasted on the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) using the BLASTn tool (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool) and were run with the parameter of highly similar sequences (Megablast) to inquire the homology between the obtained sequences and the existing sequences on the NCBI database. Thereafter, the contigs were submitted to the GenBank using BankIt submission tool of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/)(Bethesda, Maryland, USA) and the accession numbers were obtained. The data were simultaneously made available to the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA) (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/ena) (Hinxton, Cambridgeshire, UK) and to the DNA Data Bank of Japan (DDBJ) (https://www.ddbj.nig.ac.jp/index-e.html) (Shizuoka, Japan).

Phylogenetic analysis

The sequences were multiply aligned with the sequences of different pathogens obtained from the NCBI database by the MegAlign (DNASTAR, Wisconsin, USA) with default parameter settings. Maximum likelihood (ML) trees were constructed with bootstraps of 1,000 replicates based upon the alignment of the target genes using the Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Program Ver. X (MEGA X) (Pennsylvania State University, USA). The best-fit evolutionary models were selected according to the lowest values of Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), corrected Akaike Information Criterion (cAIC) and maximum likelihood value (InL). The evolutionary distances were estimated using the Kimura 2-parameter model [54] for Ehrlichia spp. (16S rRNA), Rickettsia spp. (16S rRNA) and Trypanosoma spp. (ITS1/ Cathepsin L); the Tamura-Nei model [55] for Anaplasma spp. (16S rRNA) and Mycoplasma/Spiroplasma spp. (16S rRNA); the Tamura 3-parameter model [56] for Borrelia spp. (FlaB/5S-23S ribosomal RNA intergenic spacer region) and Leishmania spp. (ITS1); the Hasegawa-Kishino-Yano model [57] for Theileria spp. (18S rRNA), Eh. ruminantium (pCS20) and Coxiella spp. (16S rRNA); and the General Time Reversible (GTR) for Babesia spp. (18S rRNA) and Hepatozoon spp. (18S rRNA). All ambiguous positions were removed for each sequence pair, and the phylogenetic trees were constructed accordingly.

Statistical analysis

The obtained datasets were statistically analyzed using MedCalc Statistical Software version 20.006 (MedCalc Software Ltd, Ostend, Belgium; https://www.medcalc.org; 2021). Prevalence rates were calculated as the number of TBP species-infected ticks (individual specimens) divided by the total number of molecularly screened tick specimens of the species. A Kruskal-Wallis test (post-hoc test: Conover; P < 0.05) was used for the assessment of pathogen prevalence in relation to year of collection, different collection sites, animal hosts, and tick species. The co-infection rates were analyzed by Chi-square to specify any significant associations between the tick species and different degrees of pathogenic co-infections. A confidence interval (CI) of 95% and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant in all analyses.

Results

Host-wise distribution of ticks

A total of 11,221 ticks were collected from 498 dromedary camels (n = 2,267), 684 cattle (n = 3,010), 553 dogs (n = 3,355), and 815 sheep (n = 2,589) (S1 Table and S1 Fig). Previous morphological and molecular characterization revealed that the collected ticks belong to two tick genera viz. Rhipicephalus and Hyalomma and three distinct species identified as Rh. rutilus of dogs and sheep, Rh. annulatus of cattle, and Hy. dromedarii of dromedary camels. The other tick species found infesting the animal hosts during this study (less than 4% of Hy. excavatum, Hy. impeltatum and Hy. franchinii infesting camels and Rh. turanicus for dogs and sheep) were excluded due to their occasional/irregular occurrence and considerably low numbers.

Detection of pathogens in ticks and prevalence rates

The present study revealed the presence of Anaplasma marginale, Candidatus Anaplasma camelii, Babesia canis vogeli, Ba. bigemina, Ba. Bovis, Theileria annulata, Th. lestoquardi, Th. ovis, Borrelia burgdorferi, Bo. theileri, Coxiella burnetii, Ehrlichia canis, Eh. ruminantium, Rickettsia conorii, R. africae, Hepatozoon canis, Leishmania infantum, Trypanosoma evansi, Mycoplasma arginini, and Spiroplasma-like endosymbionts with an overall infection rate of 84.1% (3,315/3,940) in all the investigated ticks. No single infection was found for T. vivax. Detailed information about the tick species-pathogen detected in relation to their hosts and GenBank accession numbers are provided in S2 Table along with their similarity, references, and genetic divergence statuses. The occurrence of TBPs in the screened ticks showed significant variations between different tick species (P = 0.0433), and between different infested animal hosts (P < 0.0346), whereas insignificant differences were found across the collection localities (P = 0.0757) and different years of collection (P = 0.8031).

Prevalence of TBPs associated with Hyalomma dromedarii

Approximately 86.7% (902/1040) of the screened Hy. dromedarii ticks were found positive to Bo. burgdorferi, Candidatus Anaplasma camelii, Eh. ruminantium, Mycoplasma arginini, R. africae, Spiroplasma-like endosymbionts, Th. annulata, C. burnetii, H. canis, and L. infantum. Out of 1,040 screened specimens, Ca. A. camelii recorded the highest prevalence by 18.8%, followed by Eh. ruminantium (16.5%), R. africae (12.6%), Th. annulata (11.9%), M. arginini (9.9%), Bo. burgdorferi (7.7%), Spiroplasma-like endosymbiont (4.0%), H. canis (2.4%), C. burnetii (1.6%) and L. infantum (1.3%) (Table 2 and S2 Fig). Single infections were found in 75 ticks viz. Eh. ruminantium (2.9%), Th. annulata (2.7%), R. africae (2.5%), and M. arginini (0.2%). Double co-infections were recorded in 27 ticks viz. Eh. ruminantium + R. africae (1.9%) and Bo. burgdorferi + M. arginini (1.1%) (Table 3); triple co-infections in 87 ticks by Ca. A. camelii + Eh. ruminantium + Th. annulata (9.6%). Multiple co-infections by co-existence of four or more pathogens in the same tick were found in 108 individuals viz. Ca. A. camelii + Bo. burgdorferi + M. arginini + R. africae (5.9%), Ca. A. camelii + L. infantum + M. arginini + R. africae + Th. annulata (1.4%), Ca. A. camelii + Bo. burgdorferi + C. burnetii + Eh. ruminantium + Spiroplasma sp. (1.9%), and Ca. A. camelii + Eh. ruminantium + H. canis + M. arginini + Spiroplasma sp. + R. africae (2.8%) (Table 4 and S3 Fig).

Table 2. Prevalence and species-wise distribution of tick-borne pathogens detected in ticks collected from North and North-Western Egypt.

| Samples | Number of positive ticks per pathogen species (%) | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tick species | Host | No. of screened ticks (% positive prevalence) |

Anaplasma | Babesia | Borrelia | Coxiella burnetii | Ehrlichia | Hepatozoon canis | Leishmania infantum | Mycoplasma/Spiroplasma | Rickettsia | Theileria | Trypanosoma evansi | |||||||||

| An. mar | Ca. An. cam | Ba. ca. vo | Ba. bi | Ba. bo | Bo. burg | Bo. Th | Eh. ca | Eh. ru | My. arg | Sp.-like endo | R. co | R. af | Th. lest | Th. ov | Th. an | |||||||

| Rhipicephalus rutilus | Dogs | 865 (94.3) | – | – | 148 (17.1) | – | – | 84 (9.7) | – | 63 (7.3) | 133 (15.4) | – | 118 (13.6) | 73 (8.4) | – | – | 140 (16.2) | – | – | – | – | 57 (6.6) |

| Sheep | 570 (42.5) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 5 (0.9) | – | – | – | – | – | – | 12 3(21.6) | 114 (20) | – | – | |

| Subtotal | 1,435 (73.7) | – | – | 148 (10.3) | – | – | 84 (5.9) | – |

63 (9.3) | 133 (3.1) | 5 (0.3) | 118 (8.4) | 73 (5.1) | – | – | 140 (9.8) | – | 123 (8.6) | 114 (7.9) | – | 57 (4.0) | |

| Rhipicephalus annulatus |

Cattle

(Subtotal) |

1,465 (99.2) | 312 (21.3) | – | – | 266 (18.2) | 205 (14.0) | 40 (2.7) | 187 (12.8) | – | – | 37 (2.5) | – | – | – | – | – | 181 (12.4) | – | – | 127 (8.7) | – |

| Hyalomma dromedarii | Camels (Subtotal) | 1,040 (86.7) | – | 195 (18.8) | – | – | – | 80 (7.7) | – | 17 (1.6) | – | 172(16.5) | 25 (2.4) | 13 (1.3) | 103 (9.9) | 42 (4.0) | – | 131 (12.6) | – | – | 124 (11.9) | – |

| Total | 3,940 (84.1) |

312 (7.9) | 195 (4.9) | 148 (3.8) | 266 (6.8) | 205 (5.2) | 204 (5.2) | 187 (4.7) | 80 (2.0) | 133 (3.4) | 214(5.4) | 143 (3.6) | 86 (2.2) | 103 (2.6) | 42 (1.1) | 140 (3.6) | 312 (7.9) | 123 (3.1) | 114 (2.9) | 251 (6.4) | 57 (1.4) | |

Abbreviations: An. mar (Anaplasma marginale), Ca. An. cam (Candidatus Anaplasma camelii), Ba. ca. vo. (Babesia canis vogeli), Ba. bi (Babesia bigemina), Ba. bo (Babesia bovis), Bo. burg (Borrelia burgdorferi), Bo. th (Borrelia theileri), Eh. ca (Ehrlichia canis), Eh. ru (Ehrlichia ruminantium), My. arg (Mycoplasma arginini), Sp-like endo (Spiroplasma-like endosymbiont), R. co (Rickettsia conorii), R. af (Rickettsia africae), Th. lest (Theileria lestoquardi), Th. ov (Theileria ovis), Th. an (Theileria annulata).

Table 3. Single and double co-infection rates detected in ticks infesting different hosts in Egypt.

| Tick species | Single infections (% of total positive prevalence) | Total | *X2 = 21.026 P = 0.0046 |

Double co-infections (% of total positive prevalence) | Total |

*X2 = 14.067 P = 0.0325 |

|||||||||||||||||||

| Bc | Hc | Rc | Te | Tl | To | Am | Bbi | Bbo | Ra | Er | Ma | Ta | Bc+Cb | Ec+Rc | Hc+Li | Tl+To | Am+Ra | Bbi+Bbo | Er+Ra | Bb+Ma | |||||

| Rh. rutilus (Dogs) |

5

(0.6) |

49

(6.0) |

3

(0.4) |

20

(2.5) |

77

(9.4) |

26

(3.2) |

24

(2.9) |

40

(4.9) |

90

(11.0) |

||||||||||||||||

| Rh. rutilus (Sheep) |

45

(18.6) |

36

(14.9) |

81

(33.5) |

73

(30.2) |

73

(30.2) |

||||||||||||||||||||

| Rh. annulatus |

39

(2.9) |

84

(6.2) |

7

(0.5) |

7

(0.5) |

137

(10.1) |

10

(0.7) |

15

(1.1) |

25

(1.8) |

|||||||||||||||||

| Hy. dromedarii |

23

(2.5) |

26

(2.9) |

2

(0.2) |

24

(2.7) |

75

(8.3) |

17

(1.9) |

10

(1.1) |

27

(3.0) |

|||||||||||||||||

Abbreviations: Am: Anaplasma marginale; Ac: Candidatus Anaplasma camelii; Bc: Babesia canis vogeli; Bbi: Babesia bigemina; Bbo: Babesia bovis; Bb: Borrelia burgdorferi; Bt: Borrelia theileri; Cb: Coxiella burnetii; Ec: Ehrlichia canis; Er: Ehrlichia ruminantium; Hc: Hepatozoon canis; Li: Leishmania infantum; Ma: Mycoplasma arginini; Rc: Rickettsia conorii; Ra: Rickettsia africae; Spi: Spiroplasma endosymbiont; Tl: Theileria lestoquardi; To: Theileria ovis; Ta: Theileria annulata; Te: Trypanosoma evansi.

* Chi-squared P-value test was used to assess the association between tick species and the carried pathogens with regard to the co-infection rates, significant association was found at the levels of single infections, and all the levels of co-infections.

Table 4. Triple and multiple co-infection rates detected in ticks infesting different hosts in Egypt.

| Tick species | Triple co-infections (% of total positive prevalence) | Total | *X2 = 12.592 P = 0.0291 |

Multiple co-infections (% of total positive prevalence) | Total | *X2 = 16.919 P = 0.0013 | |||||||||||||||

| Bc+Ec+Li | Ec+Hc+Rc | Tl+To+Er | Am+Ra+Ta | Am+Bbi+Bbo | Bbi+Bbo+Bt | Ac+Er+Ta | Bc+Bb+Ec+Rc | Bc+Bb+Cb+Rc+Te | Am+Bt+Ra+Ta | Am+Bbi+Bbo+Bb | Am+Bt+Er+Ra | Bbo+Bt+Ra+Ta | Ac+Bb+Ma+Ra | Ac+Bb+Cb+Er+Spi | Ac+Li+Ma+Ra+Ta | Ac+Er+Hc+Ma+Spi+Ra | |||||

| Rh. rutilus (Dogs) |

33

(4.0) |

29

(3.6) |

62

(7.6) |

47

(5.8) |

37

(4.5) |

84

(10.3) |

|||||||||||||||

| Rh. rutilus (Sheep) |

5

(2.1) |

5

(2.1) |

|||||||||||||||||||

| Rh. annulatus |

29

(2.1) |

75

(5.5) |

52

(3.8) |

156

(11.5) |

82

(6.1) |

40

(3.0) |

37

(2.7) |

16

(1.2) |

175

(12.9) |

||||||||||||

| Hy. dromedarii |

87

(9.6) |

87

(9.6) |

53

(5.9) |

17

(1.9) |

13

(1.4) |

25

(2.8) |

108

(12.0) |

||||||||||||||

Abbreviations: Am: Anaplasma marginale; Ac: Candidatus Anaplasma camelii; Bc: Babesia canis vogeli; Bbi: Babesia bigemina; Bbo: Babesia bovis; Bb: Borrelia burgdorferi; Bt: Borrelia theileri; Cb: Coxiella burnetii; Ec: Ehrlichia canis; Er: Ehrlichia ruminantium; Hc: Hepatozoon canis; Li: Leishmania infantum; Ma: Mycoplasma arginini; Rc: Rickettsia conorii; Ra: Rickettsia africae; Spi: Spiroplasma endosymbiont; Tl: Theileria lestoquardi; To: Theileria ovis; Ta: Theileria annulata; Te: Trypanosoma evansi.

* Chi-squared P-value test was used to assess the association between tick species and the carried pathogens with regard to the co-infection rates, significant association was found at the levels of single infections, and all the levels of co-infections.

Prevalence of TBPs associated with Rhipicephalus rutilus

An overall infection percentage of 73.7% (1,058/1,435) was recorded in Rh. ritulus ticks. Babesia canis vogeli, Borrelia burgdorferi, Coxiella burnetii, Ehrlichia canis, Hepatozoon canis, Leishmania infantum, Rickettsia conorii, Trypanosoma evansi in Rh. rutilus collected from dogs, whereas Eh. ruminantium, Theileria lestoquardi, and Th. ovis in Rh. rutilus collected from sheep. Approximately 94.3% (816/865) of Rh. rutilus tick specimen that were infesting dogs, Ba. canis vogeli was the predominant species with 17.1%, followed by R. conorii (16.2%), E. canis (15.4%), H. canis (13.6%), Bo. burgdorferi (9.7%), L. infantum (8.4%), C. burnetii (7.3%) and T. evansi (6.6%) (S4 Fig). For the positive Rh. rutilus ticks infesting dogs, 77 single infections viz. H. canis (6.0%), T. evansi (2.5%), Ba. canis vogeli (0.6%), and R. conorii (0.4%); 90 double-infected ticks viz. H. canis + L. infantum (4.9%), Ba. canis vogeli + C. burnetii (3.2%), and Eh. canis + R. conorii (2.9%) (Table 3); 62 ticks with triple co-infections viz. Ba. canis vogeli + Eh. canis + L. infantum (4.0%), and Eh. canis + H. canis + R. conorii (3.6%); and 84 ticks were found co-infected by four or more pathogens viz. Ba. canis vogeli + Bo. burgdorferi + Eh. canis + R. conorii (5.8%) and Ba. canis vogeli + Bo. burgdorferi + C. burnetii + R. conorii + T. evansi (4.5%) (Table 4 and S5 Fig).

On the other hand, approximately 42.5% (n = 242/570) investigated Rh. rutilus specimens collected from sheep were positive for Th. lestoquardi (21.6%), Th. ovis (20.0%) and Eh. ruminantium (0.9%) (S4 Fig). Eighty-one single infections were recorded as Th. lestoquardi (18.6%) and Th. ovis (14.9%), whereas 73 double co-infections were found by Th. lestoquardi + Th. ovis (30.2%) (Table 3), and five triple co-infections were found by Th. lestoquardi + Th. ovis + Eh. ruminantium (2.1%) (Table 4 and S6 Fig).

Prevalence of TBPs associated with Rhipicephalus annulatus

Approximately 92.5% (1,355/1,465) of Rh. annulatus ticks were found positive to the infections. Rhipicephalus annulatus harbored Anaplasma marginale, Ba. bigemina, Ba. bovis, Bo. burgdorferi, Eh. ruminantium, R. africae, Th. annulata, Bo. theileri. Out of 1,465 screened Rh. annulatus specimens, A. marginale was positively found in 21.3% of the ticks, followed by Ba. bigemina (18.2%), Ba. bovis (14.0%), Bo. theleri (12.8%), R. africae (12.4%), Th. annulata (8.7%), Bo. burgdorferi (2.7%) and Eh. ruminantium (2.5%) (Table 2 and S7 Fig). Single infections were recorded in 137 ticks viz. Ba. bigemina (6.2%), A. marginale (2.9%), Ba. bovis (0.5%), and R. africae (0.5%). Double co-infections were recorded in 25 ticks viz. Ba. bigemina + Ba. bovis (1.1%) and A. marginale + R. africae (0.7%) (Table 3). The cases of triple co-infections were found in 156 ticks viz. A. marginale + Ba. bigemina + Ba. bovis (5.5%), Ba. bigemina + Ba. bovis + Bo. theileri (3.8%), and A. marginale + R. africae + Th. annulata (2.1%). The multiple co-infections by four or more pathogens in the same tick were found in 175 ticks viz. A. marginale + Bo. theileri + R. africae + Th. annulata (6.1%), A. marginale + Ba. bigemina + Ba. bovis + Bo. burgdorferi (3%), A. marginale + Bo. theileri + Eh. ruminantium + R. africae (2.7%), and Ba. bovis + Bo. theileri + R. africae + Th. annulata (1.2%) (Table 4 and S8 Fig). Significant associations were found between all the tick species and their harbored pathogens at the levels of single infection, and multiple co-infections (≥ four pathogens). The associations among various tick species and the pattern of infections were found statistically significant (P < 0.05) at the levels of single infections (X2 = 21.026, P = 0.0046), double co-infections (X2 = 14.067, P = 0.0325), triple co-infections (X2 = 12.592, P = 0.0291) and multiple co-infections (X2 = 16.919, P = 0.0013) (Tables 3 and 4).

Sequencing, Phylogenetic analysis and genetic diversity

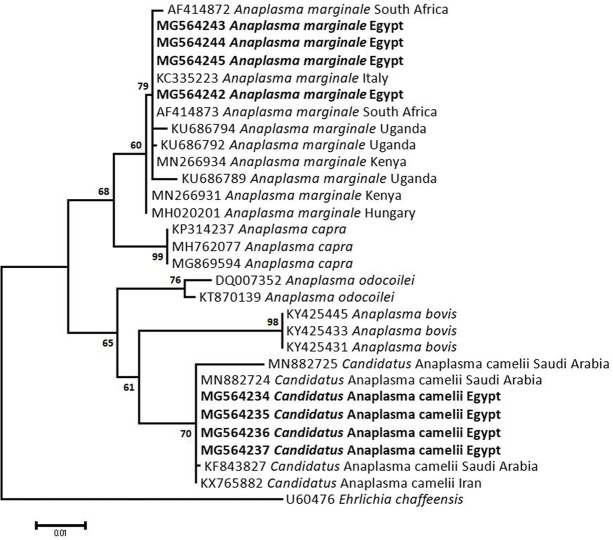

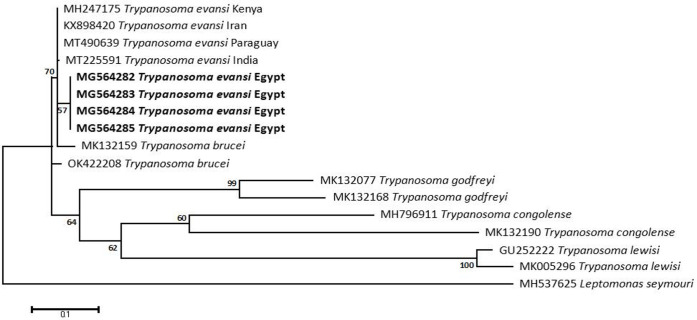

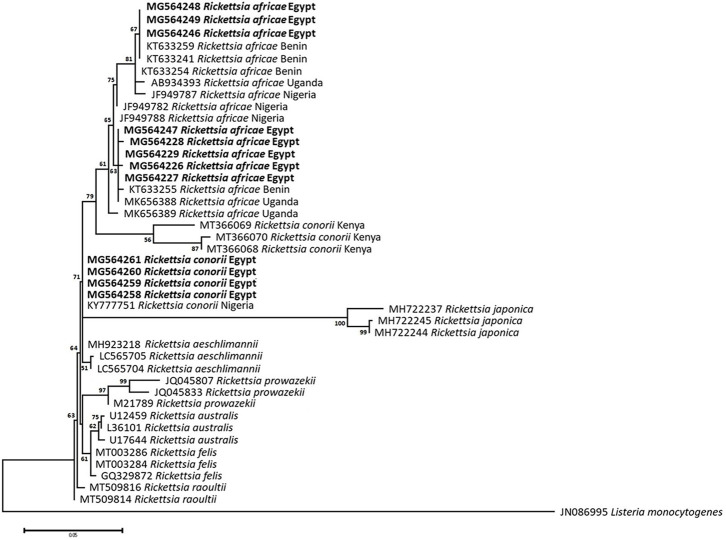

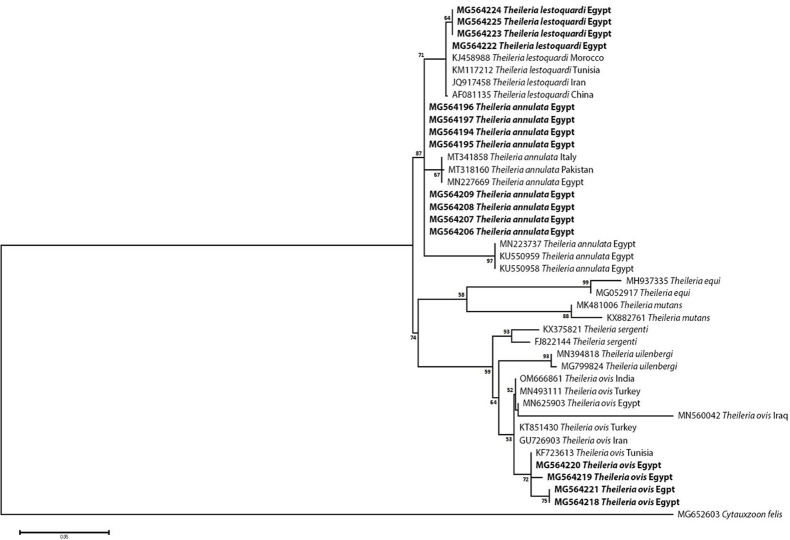

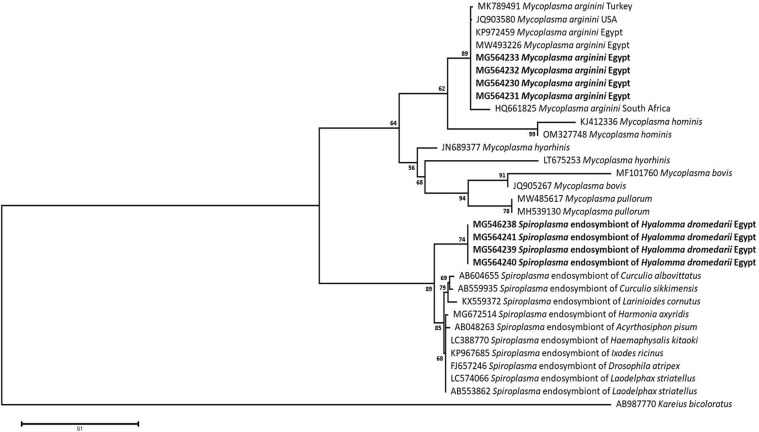

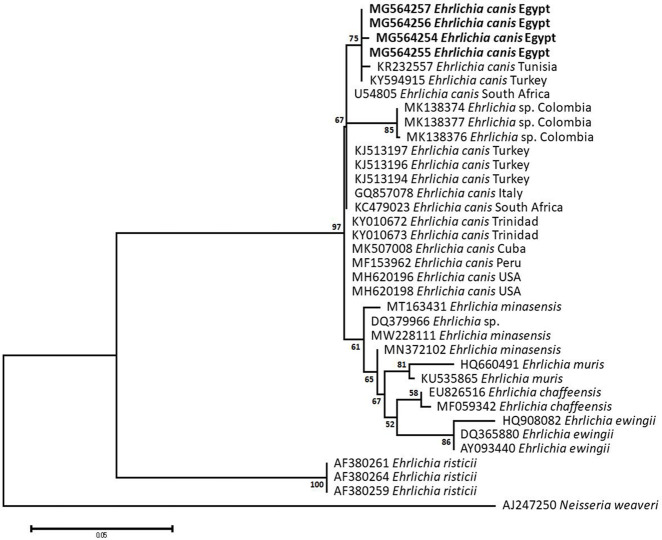

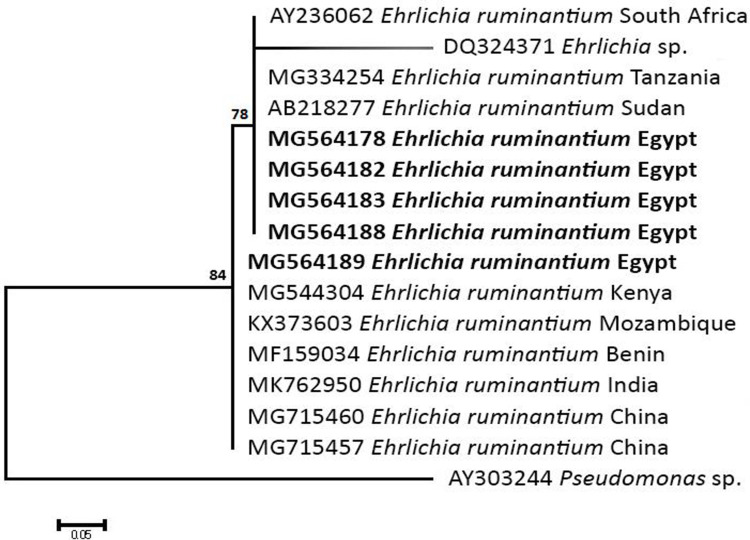

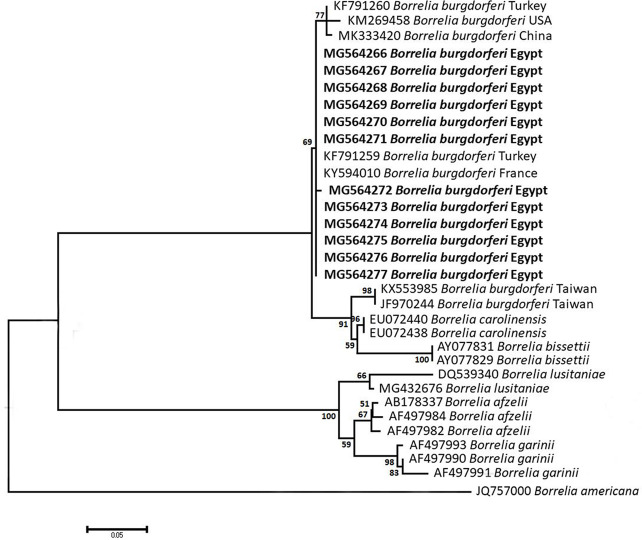

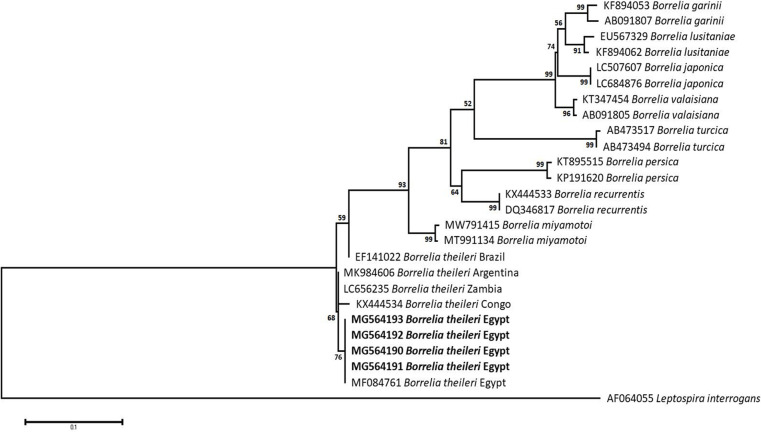

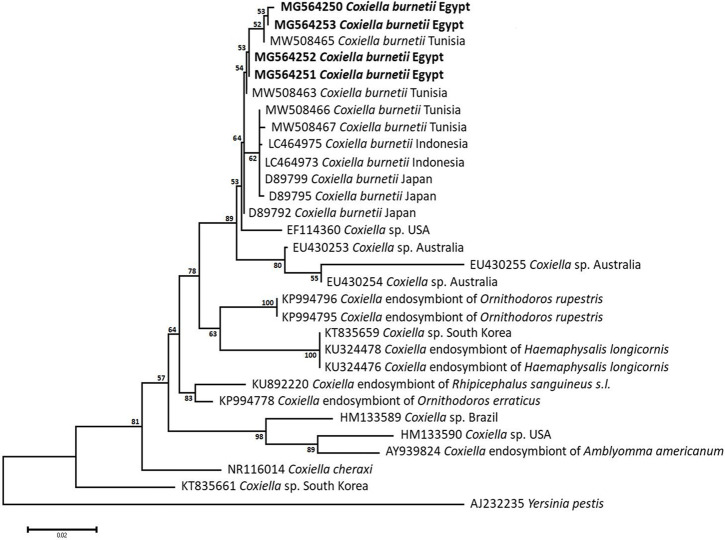

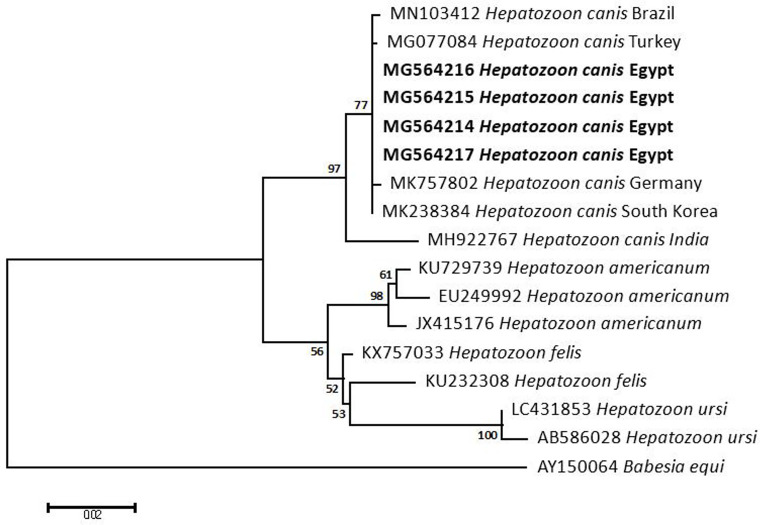

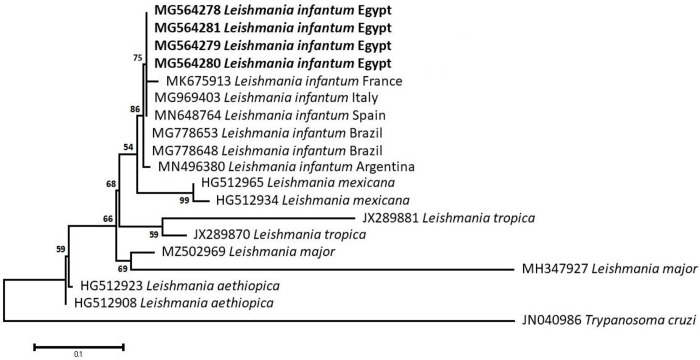

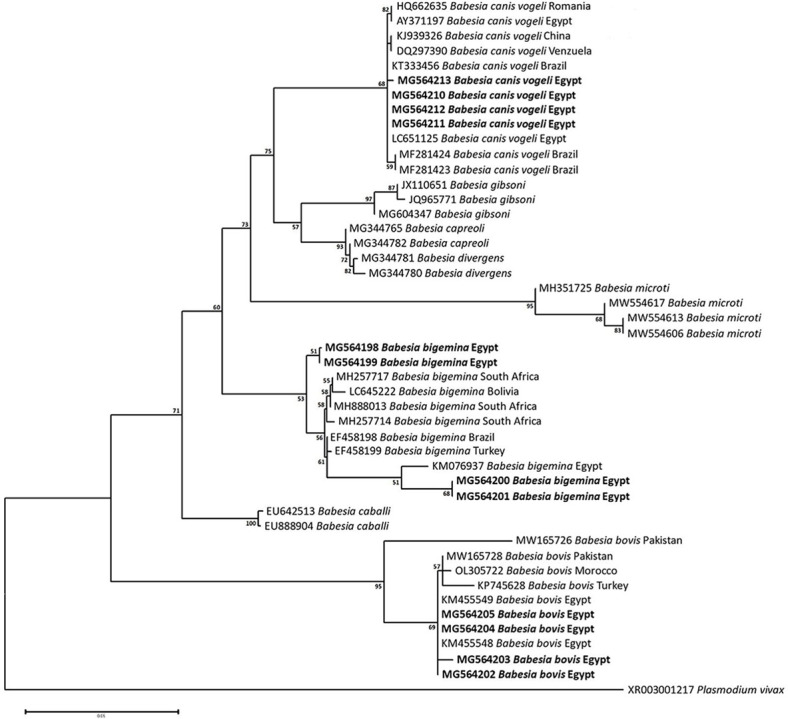

The obtained sequences of different pathogens detected in this study showed similarities ranging from 98.76 to 100% and a range between 0.001 to 0.009% genetic divergence. Exceptions were given to the Spiroplasma endosymbiont that showed similarity between 88.56–100%, and the sequences of Theileria annulata, Leishmania infantum, and Mycoplasma arginini that showed no genetic variations to their references. Details of homology percentages, reference accession numbers, and genetic divergence are shown in S2 Table. Phylogenetic trees of Anaplasma spp., Babesia spp., Rickettsia spp., Theileria spp., Mycoplasma/Spiroplasma spp., Ehrlichia canis, Eh. ruminantium, Borrelia burgdorferi, Bo. theileri, Coxiella burnetii, Hepatozoon canis, Leishmania infantum, and Trypanosoma evansi are presented in Figs 2–14. Phylogenetically, Egyptian isolates of An. marginale, R. africae, R. conorii, Eh. ruminantium, Bo. theileri clustered with other African isolates from Kenya, Uganda, South Africa, Benin, Nigeria, Tanzania, Sudan, Republic of Congo, Egypt, and Zambia. More closely, isolates of Ba. bovis, Ba. bigemina, Th. lestoquardi, Th. ovis, and C. burnetii clustered with isolates from northern Africa such as Tunisia, Egypt, and Morocco. Isolates of Ba. canis vogeli and some Ba. bigemina were phylogenetically close to South American isolates from Brazil, Venezuela, Bolivia. Asian and Eurasian isolates from Saudi Arabia, Iran, Pakistan, Turkey, China, India of Ca. An. camelii, Th. annulata, T. evansi clustered with Egyptian isolates of this study. Egyptian isolates of M. arginini, H. canis, and L. infantum clustered with European and Asian isolates from France, Germany, Spain, and China.

Fig 2. Maximum-likelihood tree based on sequences of the 16S rRNA gene of Anaplasma species detected in the present study of Egyptian ticks (bold).

Numbers represent bootstrap support generated from 1,000 replications. The tree was constructed with the Tamura-Nei model using Ehrlichia chaffeensis as an outgroup.

Fig 14. Maximum-likelihood tree based on sequences of the ITS1 gene of Trypanosoma evansi detected in the present study of Egyptian ticks (bold).

Numbers represent bootstrap support generated from 1,000 replications. The tree was constructed with the Kimura 2-parameter model using Leptomonas seymouri as an outgroup.

Fig 3. Maximum-likelihood tree based on sequences of the 18S rRNA gene of Babesia species detected in the present study of Egyptian ticks (bold).

Numbers represent bootstrap support generated from 1,000 replications. The tree was constructed with the General Time Reversible (GTR) model using Plasmodium vivax as an outgroup.

Fig 4. Maximum-likelihood tree based on sequences of the 16S rRNA gene of Rickettsia species detected in the present study of Egyptian ticks (bold).

Numbers represent bootstrap support generated from 1,000 replications. The tree was constructed with the Kimura 2-parameter model using Listeria monocytogenes as an outgroup.

Fig 5. Maximum-likelihood tree based on sequences of the 18S rRNA gene of Theileria detected in the present study of Egyptian ticks (bold).

Numbers represent bootstrap support generated from 1,000 replications. The tree was constructed with the Hasegawa-Kishino-Yano model using Cytauxzoon felis as an outgroup.

Fig 6. Maximum-likelihood tree based on sequences of the 16S rRNA gene of Mycoplasma/Spiroplasma detected in the present study of Egyptian ticks (bold).

Numbers represent bootstrap support generated from 1,000 replications. The tree was constructed with the Tamura-Nei model using Kareius bicoloratus as an outgroup.

Fig 7. Maximum-likelihood tree based on sequences of the 16S rRNA gene of Ehrlichia canis detected in the present study of Egyptian ticks (bold).

Numbers represent bootstrap support generated from 1,000 replications. The tree was constructed with the Kimura 2-parameter model using Neisseria weaveri as an outgroup.

Fig 8. Maximum-likelihood tree based on sequences of the ribonuclease III (pCS20) gene of Ehrlichia ruminantium detected in the present study of Egyptian ticks (bold).

Numbers represent bootstrap support generated from 1,000 replications. The tree was constructed with the Hasegawa-Kishino-Yano model using Pseudomonas sp. as an outgroup.

Fig 9. Maximum-likelihood tree based on sequences of the 5S-23S rRNA intergenic spacer of Borrelia burgdorferi detected in the present study of Egyptian ticks (bold).

Numbers represent bootstrap support generated from 1,000 replications. The tree was constructed with the Tamura 3-parameter model using Borrelia americana as an outgroup.

Fig 10. Maximum-likelihood tree based on sequences of the FlaB gene of Borrelia theileri detected in the present study of Egyptian ticks (bold).

Numbers represent bootstrap support generated from 1,000 replications. The tree was constructed with the Tamura 3-parameter model using Leptospira interrogans as an outgroup.

Fig 11. Maximum-likelihood tree based on sequences of the 16S rRNA gene of Coxiella burnetii detected in the present study of Egyptian ticks (bold).

Numbers represent bootstrap support generated from 1,000 replications. The tree was constructed with the Hasegawa-Kishino-Yano model using Yersinia pestis as an outgroup.

Fig 12. Maximum-likelihood tree based on sequences of the 18S rRNA gene of Hepatozoon canis detected in the present study of Egyptian ticks (bold).

Numbers represent bootstrap support generated from 1,000 replications. The tree was constructed with the General Time Reversible (GTR) model using Babesia equi as an outgroup.

Fig 13. Maximum-likelihood tree based on sequences of the ITS1 gene of Leishmania infantum detected in the present study of Egyptian ticks (bold).

Numbers represent bootstrap support generated from 1,000 replications. The tree was constructed with the Tamura 3-parameter model using Trypanosoma cruzi as an outgroup.

Discussion

The present study revealed a dominance of tick-borne bacterial agents in Egyptian ticks. The causative agent of bovine anaplasmosis, A. marginale, prevailed in 21.3% of Rh. annulatus ticks, whereas the newly emerged Candidatus A. camelii was found in 18.8% of Hy. dromedarii ticks. Reports of the former in Egypt started in 2010, being detected in various hosts in many parts of Egypt [58–70] with the known symptoms of the disease, causing blood impairment that might lead to death [71] (S3 Table). Contrary to the earlier studies, the infected Rh. annulatus ticks were exclusively infesting cattle hosts in the current study, with a first detection report from Alexandria governorate. This might be due to the high degree of host preference that Rh. annulatus ticks have. The emergence of Ca. A. camelii in Egypt was firstly reported from imported Sudanese camels, followed by only one report from Aswan governorate. Nonetheless, no information is available about its pathogenicity, reservoir hosts, or potential vectors, lowering its zoonotic importance [72]. The present study detected Ca. A. camelii in three new localities of Egypt in Hy. dromedarii ticks, recommending the importance of conducting laboratorial studies regarding the ability of this tick species to transmit Ca. A. camelii among different animal hosts and governorates in Egypt, especially that it has been detected once before in Aswan governorate (upper Egypt) [72]. In comparison, previous studies revealed the presence of the human granulocytic anaplasmosis agent, A. phagocytophilum with a percentage of 7.5% of Egyptian farmers in Giza and Nile Delta. This relatively high infectivity rate may be due to the daily contact of the farmers with the infected animals [73].

In contrast, limited attention has been given to ehrlichiosis in Egypt through ELISA [74,75] or PCR-based few studies [76–78]. Despite the high degree of association between Eh. ruminantium and Amblyomma tick vectors in several African countries, the heartwater disease agent has been found in 16.5% of Hy. dromedarii, 2.5% of Rh. annulatus, and 0.3% of Rh. rutilus ticks of camels, cattle, and sheep, respectively. These findings suggest that animal imports infested by Amblyomma ticks, such as Am. variegatum, Am. gemma, and Am. lepidum [79] are likely the main source of the introduction and spread of this pathogen. This is the first report of Eh. ruminantium in Egypt. Likewise, Eh. canis was previously detected in several hosts from Central and Northern Egypt [79] (S3 Table); however, the present study confirms its presence in 3.1% of Rh. rutilus of dogs in Beheira and Marsa Matrouh for the first time, indicating that canine ehrlichiosis cases are expanding throughout the country. In Egypt, transboundary transmission of emerging pathogens or even new genetic variants is mainly due to the importation of animals and birds [80]. Ehrlichia canis has not been previously reported in the country until 1995, when its known symptoms appeared among German Shepherd dogs, one of the most popular imported pets in Egypt, along with the Rottweiler and Pit Bull breeds. These imported breeds were later positively detected to be infected by Ehrlichia spp. with a prevalence percentage of 8.8%. Since these importations do not receive the proper inspections, they are continuously introducing novel pathogens or new genetic variants of known pathogens into the country. In this context, the increasing pet’s importation into the country might be a reason for the spread and appearance of new genetic variants of Eh. canis. The human ehrlichiosis seems to be rare in Egypt, even the only investigations regarding the positivity of Eh. chaffeensis and Eh. ewingii in humans revealed negative results.

Serological detections of rickettsiosis in Egypt previously revealed positivity in rodents, lambs, and humans to R. conorii and R. africae in many parts of the country [81–84]. However, none of these reports has linked the agents of either the spotted fever rickettsioses (SFG) or the neglected African tick-bite fever (ATBF) to any tick species as vectors, despite the familiarity of the former in Mediterranean countries [85]. Thus, the current study links R. conorii with Rh. rutilus ticks in three new localities in Egypt, with a prevalence of 9.8%. Furthermore, PCR-based studies have previously revealed the presence of R. africae in camels, cattle, and their ticks, particularly in North Sinai [85–88], and both R. africae and R. conorii in other Egyptian governorates, including Aswan, Sharkia, Cairo, and Giza [89–91] (S3 Table); however, the current study confirms its positivity in 12.6% and 12.4% of Hy. dromedarii and Rh. annulatus ticks, respectively, showing the rapid expansion of the disease towards the northern part of the country through the well-establishment of its tick vectors throughout the country.

Despite the typical association between Lyme spirochetes and Ixodes tick vectors, causing Lyme spirochetaemia that leads to annual medical costs between USD 712 million and 1.3 billion [92] and led to a total of 23 death cases between 1999 and 2003 in the USA only [93], the present study approved the positivity of 7.7%, 5.9%, and 2.7% of Hy. dromedarii, Rh. rutilus, and Rh. annulatus ticks, respectively. Although Bo. burgdorferi was previously detected in Egyptian people and their companion animals from different parts, including Fayoum, Beni-Suef, Cairo, and Giza [93,94] (S3 Table), the current study presents molecular evidence of the spirochetes in three new localities of Egypt, suggesting the success of landing migratory birds naturally infested by Bo. burgdorferi-infected Ixodes ticks such as I. ricinus, I. frontalis, and I. redikorzevi, and their co-infestation with local tick species to be the reason behind the emergence of the disease in Egypt. The human cases of Lyme borreliosis in Egypt were only detected once to include two persons and one case in co-infection with An. phagocytophilum. Since then, no other studies regarding the investigation of Lyme disease in Egyptian people were conducted. Probably, Bo. theileri is one of the endemic agents of cattle worldwide, particularly in the tropics and subtropics [95–97]. In Egypt, it has been previously detected in bovines from many parts of the country from its main vectors, Rhipicephalus ticks (S3 Table). The current study, in context, confirms the presence of bovine borreliosis in the only cattle tick species in Egypt, Rh. annulatus.

Q fever causative bacteria were previously detected in Egyptian citizens, animals, and ticks such as Hy. dromedarii, Hy. anatolicum, Argas persicus, Am. variegatum, Rh. pulchellus, and Rh. sanguineus, from Alexandria, Aswan, Cairo, Dakahlia, Giza, Ismailia, Marsa Matrouh, New Valley, Port Said, Sharkia, and Sinai (S3 Table) [98–100]. The disease affects 50 out of 100,000 people annually, with the main influence on the respiratory system [101,102]. The current study revealed the positivity of Rh. rutilus (9.3%) and Hy. dromedarii (1.6%) ticks to C. burnetii. Co-infestation is apparently a major reason behind the expansion of the disease. Seemingly, M. arginini is a newly emerged agent in Egypt, infecting the genital organs, eyes, and ears of animals and humans [103–105]. The presence of M. arginini in the blood circulation presents an advantage for ticks harboring it; however, extensive laboratory studies are needed to confirm Hy. dromedarii as a possible vector or not. Despite the previous reports about the presence of M. arginini in the blood of infected animal hosts in Giza and Menoufiya governorates [106–108], it has not been linked to tick vectors. Therefore, the present study found 9.9% of Hy. dromedarii ticks positive to M. arginini in the first report of linkage to ticks. Spiroplasma seems to be a regular presence in various arthropods, which impacts their growth, immunity, reproduction, and speciation [109–111]. Ticks are no exception, as we detected Spiroplasma in Hy. dromedarii ticks (4%) that shares a high percentage of similarity with previously detected ones, including S. mirum from Haemaphysalis leporispalustris and S. ixodetis from Ixodes pacificus, among others [112–121]. Although we primarily aimed to detect pathogenic microorganisms, we accidentally detected the Spiroplasma endosymbionts during the screening of pathogenic Mycoplasma, probably due to the similar genetic composition between the two genera. Spiroplasma endosymbionts selectively kill the male progeny during embryogenesis, having a female-biased (male-killing) effect on their hosts, which explains the female-biased populations loaded with these endosymbionts throughout our collecting expeditions, whereas no male Hy. dromedarii was found positive to this microorganism [122].

Protozoal pathogens causing canine and bovine babesiosis were highly abundant in the present study as well, as they were reported in 10.3% and 14–18.2% of Rh. rutilus and Rh. annulatus ticks, respectively. To date, eight Babesia species, including Ba. canis vogeli, Ba. bigemina, and Ba. bovis, have been reported from Egypt [123–135] (S3 Table). Three new localities have been confirmed for Ba. canis vogeli in the present study, which was linked to Rh. rutilus ticks as possible vectors, helping in its expansion since it was detected in dogs in Cairo [135]. Likewise, this study reports Ba. bigemina and Ba. bovis from Alexandria for the first time; however, bovine babesiosis seems to be endemic in Egypt.

Bovine theileriosis, initially documented in Egypt in 1947, affects cattle and buffaloes and has been linked to decreased animal production, resulting in annual losses of USD 13.9 to 18.7 billion [136,137]. The current study revealed the presence of Th. annulata in Hy. dromedarii (11.9%) and Rh. annulatus (8.7%) ticks, Th. lestoquardi (8.6%), and Th. ovis (7.9%) in Rh. rutilus of sheep. Although tropical theileriosis was reported from various hosts and governorates [138–145], (S3 Table). Moreover, both Th. lestoquardi and Th. ovis were previously reported in Egypt from Aswan, Beheira, Beni-Suef, Cairo, Giza, Menofia, New valley, Qualyobia, Sinai, and Upper Egypt [146–148] (S3 Table); however, no information was available about its possible tick vector. This is the first detection report between Th. ovis, Th. lestoquardi, and Rh. rutilus ticks in Alexandria and Beheira.

In addition, Hepatozoon canis is closely linked to its vector, Rh. sanguineus, worldwide [149]. Although there are characteristic signs, infected hosts usually do not show clinical symptoms [150,151]. Despite earlier serological detections of H. canis in dog blood or Rh. sanguineus ticks’ ingested blood meals in Cairo and Giza [152,153] (S3 Table), the present study introduces the first 18S rRNA molecular characterization of H. canis from Egypt. Likewise, canine leishmaniasis is a zoonotic disease prevalent in the Middle East, North Africa, and the Mediterranean basin, including Egypt, where it was first reported in Egypt over 4,000 years ago, possibly due to trading contacts between ancient Egyptians and Nubia (modern Sudan). The present study confirms the positivity of Hy. dromedarii (1.3%) and Rh. rutilus (5.1%) ticks to L. infantum. Since sand flies of the subfamily Phlebotominae are the only accepted biological vectors for Leishmania parasites, the role of ticks as vectors of Leishmania, along with the possible transovarial and transstadial transmission routes, should be comprehensively investigated in future studies, at least under laboratory conditions, especially that both the parasite and the ticks have strong associations and interactions in nature [154]. In this context, further experiments are needed to confirm the compatibility of these tick species to transmit the disease. Camel ticks occasionally harbor pathogens related to canines due to the possible co-infestations with dog ticks. African trypanosomiasis, including T. evansi in camels and other domestic animals, was previously shown to be endemic; however, there have been no reports about its potential transmission to different hosts [155–157]. Thousands of camels are frequently brought into Egypt from its neighbors (Libya, Sudan, and Somalia) for breeding and slaughter. While travelling through Egypt, they interact with indigenous animals at borders, resulting in mixed genotyping and the possibility of strain differences between Egyptian sub-populations and imported strains of T. evansi [158,159]. Nonetheless, no Hy. dromedarii ticks were found positive for T. evansi in our study; however, 4% of Rh. rutilus were positive, suggesting a possible infection during feeding on other infected hosts. Despite the positivity of the blood samples of the animal hosts to T. evansi in only three earlier reports from Ismailia and Cairo governorates (S3 Table), more extensive blood investigations from Egyptian animal hosts could be used to complete the route of these infections.

Our findings indicate the presence of multiple TBPs. Considering the correlations between the evolution of host preference, tick biology, and pathogens’ transmission, ticks are apparently following a style of being global generalists and local specialists [160]. In this context, the high degree of host preference of Rh. annulatus ticks as a one-host tick species for cattle has played a great role in shaping the pathogenic diversity of this tick species exclusively for bovine pathogens. Likewise, Rh. rutilus ticks infesting sheep were also positive to the ovine pathogens only. On the other hand, the existence of dog hosts guarding the camel farms in the collection sites is probably making a chance for the Hy. dromedarii ticks to acquire canine pathogens and transmit them into camels, such as H. canis, C. burnetii, and L. infantum, which were positively found in Hy. dromedarii ticks infesting camels. Co-infections with multiple pathogens are common in Egypt’s livestock due to the mixed farming system, high livestock density, and frequent contact among species, leading to worsening disease severity and a challenge in diagnosing and treating tick-borne diseases clinically [161,162]. The phenomenon has gained attention recently, with diverse pathogenic groups, including protozoa, bacteria, viruses, and variants of the same species, being found [163]. Apparently, ticks can acquire such mixed infections through blood feeding on different vertebrate hosts or through co-feeding, in which the same host acts as a bridge between infected and uninfected ticks, facilitating pathogen transmission [164]. Co-infecting pathogens can interact synergistically through immune modulation, shared siderophores, or genetic exchange, or antagonistically through genotype conflict, resource competition, or cross-immunity, potentially altering disease severity[165]. The scientific community has received warnings about the effects of various pathogenic co-infection statuses; therefore, further research is required to ascertain the true risk that such a combination poses to the host’s health, the agricultural industry, and Egypt’s economy.

Although there is a country-wide risk due to the occurrence of ticks and tick-borne pathogens, the Egyptian agricultural and veterinary authorities are unfortunately dealing with this problem only from an economic point of view when it comes to its large-scale status, neglecting the main reasons behind the beginning of the issue [166]. To date, there is no national surveillance system established in Egypt for TBPs, limiting the available information to only huge incidences regardless the actual occurrence of various pathogens in the country [166]. In view of the outdated records and limited information about the current estimations of animal trade and their tick infestations and TBPs’ infections in Egypt, a series of challenges are present, including real estimations of the country-wide prevalence of TBPs and their burden, particularly in humans, the determination of the genetic divergence, the transmission circulation and dynamics, the evaluation of the economic impact, running successful tick control programs, and performing meta-analysis.

To overcome these obstacles, a package of potential strategies is needed, such as upscaling border inspections of imported animals to prevent the transfer of novel ticks or pathogens into the country, increasing the number of diagnostic laboratories all over the country to guarantee regular screenings of TBPs, and fast policymaking in disease prevention, filling the research gaps in understanding the epidemiological aspects of these pathogens in Egypt. Moreover, the implementation of the One Health approach in research using advanced technologies such as Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) involving ticks, animals, and humans could greatly help in an inclusive view of ticks and their transmitted pathogens in Egypt.

In conclusion, the present study provides an in-depth investigation regarding the pathogenic burdens harbored by three economically important tick species invading Egypt, viz. Rh. rutilus (formerly Rh. sanguineus, southeastern Europe lineage), Rh. annulatus, and Hy. dromedarii, of four types of animals. In addition to the wide range of TBPs detected in the ticks under this study, several novel findings have been recorded for the first time, such as the first records of A. marginale, Ba. bigemina, R. conorii, and Bo. burgdorferi in new parts of Egypt; new occurrences between Ca. A. camelii, Ba. canis vogeli, Th. ovis, Th. lestoquardi, Eh. ruminantium, and T. evansi to Hy. dromedarii and Rh. rutilus ticks; the first 18S rRNA characterization of H. canis from Egypt; and the first detection of M. arginini in ticks and Spiroplasma-endosymbiont in Hy. dromedarii ticks. Considering the scarce information and studies about ticks and their borne diseases in Egypt, it is difficult to complete the picture of these important and neglected ectoparasites. In this context, laboratory diagnostic capability in the concerned authorities should be increased to facilitate regular screening of tick-borne infections, enhance diagnosis, and inform disease prevention policymaking. Furthermore, research should be rigorously focused on major present gaps in our understanding of the epidemiology of TBDs in Egypt in terms of current trends and directions, such as a coherent One Health approach.

Supporting information

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

Species-wise amplitude of ticks during the collection trips; (A) Rhipicephalus rutilus (Dogs), (B) Rh. rutilus (Sheep), (C) Rh. annulatus, (D) Hyalomma dromedarii.

(TIF)

(TIF)

(TIF)

Pathogens’ prevalence detected in Rhipicephalus rutilus ticks infesting dogs (top) and sheep (bottom) of the present study (The percentages are out of 865 and 570 screened ticks of dogs and sheep, respectively).

(TIF)

(TIF)

(TIF)

(TIF)

(TIF)

Acknowledgments

We thank Mr. Ehab Elsaeed for his great cooperation during the collection of our specimens in Egypt. Gratefulness is extended to the Faculty of Agriculture, Alexandria University, Egypt for their encouragement during the study.

Data Availability

All the relevant data of this study are within the paper and its Supporting Information files. Some of the raw and supporting files are available at 10.5281/zenodo.11062393.

Funding Statement

Funding was provided by the Indian Council for Cultural Relations [ICCR-IN 458] to HS; Researchers Supporting Project, King Saud University (SA), RSP2024R177 to NMA. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Arthur DR. Ticks in Egypt in 1500 B.C.? Nature. 1965; 206(988):1060–1061. doi: 10.1038/2061060a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoogstraal H. Ornithodoros salahi sp. nov. Ixodoidea, Argasidae from the Cairo Citadel, with notes on O. piriformis Warburton, 1918 and O. batuensis Hirst, 1929. Parasitol 1953a; 39: 256–263. doi: 10.2307/3273947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoogstraal H. Ornithodoros arenicolous sp. nov. (Ixodoidea, Argasidae) from Egyptian desert mammal burrows. J Parasitol. 1953. b; 39: 505–516, doi: 10.2307/3273850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davis GE, Hoogstraal H. The relapsing fevers: a survey of the tick-borne spirochetes of Egypt. J Egypt Public Health Assoc. 1954; 29: 139–143. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davis GE, Hoogstraal H. Etude sur la biologie du Spirochète Borrelia persica, trouvé chez la tique Ornithodorus tholozani (Argasinæ) récoltée dans le « Governorate » du désert occidental égyptien. Ann Parasitol Hum Comp. 1956; 31: 147–154. [In French]. doi: 10.1051/PARASITE/1956311147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.El Kammah KM, Oyoun LM, El Kady G, Abdel Shafy S. Investigation of blood parasites in livestock infested with argasid and ixodid ticks in Egypt. J Egypt Soc Parasitol. 2001; 31: 365–371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abdel-Shafy S. Scanning electron microscopy and comparative morphology of argasid larvae (Acari: Ixodida: Argasidae) infesting birds in Egypt. Acarologia. 2005; 45: 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Senbill H, Tanaka T, Karawia D, Rahman S, Zeb J, Sparagano O, Baruah A. Morphological identification and molecular characterization of economically important ticks (Acari: Ixodidae) from North and North-Western Egypt. Acta Trop. 2022; 231: 106438. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2022.106438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moraes–Filho J, Marcili A, Nieri–Bastos FA, Richtzenhain LJ, Labruna MB. Genetic analysis of ticks belonging to the Rhipicephalus sanguineus group in Latin America. Acta Trop. 2011; 117: 51–55. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2010.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nava S, Mastropaolo M, Venzal JM, Mangold AJ, Guglielmone AA. Mitochondrial DNA analysis of Rhipicephalus sanguineus sensu lato (Acari: Ixodidae) in the Southern Cone of South America. Vet Parasitol. 2012; 190: 547–555. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2012.06.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chitimia–Dobler L, Langguth J, Pfeffer M, Kattner S, Küpper T, Friese D, et al. Genetic analysis of Rhipicephalus sanguineus sensu lato ticks’ parasites of dogs in Africa north of the Sahara based on mitochondrial DNA sequences. Vet Parasitol. 2017; 239: 1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2017.04.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dantas–Torres F, Latrofa MS, Ramos RAN, Lia RP, Capelli G, Parisi A, et al. Biological compatibility between two temperate lineages of brown dog ticks, Rhipicephalus sanguineus (sensu lato). Parasit Vectors. 2018; 11: 398. doi: 10.1186/s13071-018-2941-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nava S, Beati L, Venzal JM, Labruna MB, Szabό MPJ, Petney T, et al. Rhipicephalus sanguineus (Latreille, 1806): neotype designation, morphological re–description of all parasitic stages and molecular characterization. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2018; 9 (6): 1573–1585. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2018.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Šlapeta J, Chandra S, Halliday B. The "tropical lineage" of the brown dog tick Rhipicephalus sanguineus sensu lato identified as Rhipicephalus linnaei (Audouin, 1826). Int J Parasitol. 2021; 51(6): 431–436. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2021.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Šlapeta J, Halliday B, Chandra S, Alanazi AD, Abdel-Shafy S. Rhipicephalus linnaei (Audouin, 1826) recognised as the "tropical lineage" of the brown dog tick Rhipicephalus sanguineus sensu lato: Neotype designation, redescription, and establishment of morphological and molecular reference. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2022; 13(6): 102024. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2022.102024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Šlapeta J, Halliday B, Dunlop JA, Nachum-Biala Y, Salant H, Ghodrati S, et al. The "southeastern Europe" lineage of the brown dog tick Rhipicephalus sanguineus (sensu lato) identified as Rhipicephalus rutilus Koch, 1844: Comparison with holotype and generation of mitogenome reference from Israel. Curr Res Parasitol Vector Borne Dis. 2023; 3: 100118. doi: 10.1016/j.crpvbd.2023.100118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.FAO. The long-term future of livestock and fishery in production targets in the face of uncertainty. 2020; 1–33. doi: 10.4060/ca9574en [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.FAO. The state of food security and nutrition in the world: The world is at a critical juncture. 2021; 1–55. doi: 10.4060/cc0639en [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Argasid Hoogstraal H. and nuttalliellid ticks as parasites and vectors. Adv Parasitol. 1985; 24: 135–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sonenshine D, Mather T. Ecological dynamics of tick–borne zoonoses. Oxford University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Raoult D, Roux V. (1997). Rickettsioses as paradigms of new or emerging infectious diseases. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1997; 10 (4): 694–719. doi: 10.1128/CMR.10.4.694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jongejan F, Uilenberg G. The global importance of ticks. Parasitology. 2004; 129: S3. doi: 10.1017/s0031182004005967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de la Fuente J, Antunes S, Bonnet S, Cabezas-Cruz A, Domingos AG, Estrada-Peña A, et al. Tick-pathogen interactions and vector competence: Identification of molecular drivers for tick-borne diseases. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2017; 7: 114. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2017.00114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wikel SK. Ticks and tick-borne infections: Complex ecology, agents, and host interactions. Vet Sci. 2018; 5(2): 60. doi: 10.3390/vetsci5020060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Muñoz-Leal S, Ramirez DG, Luz HR, Faccini JLH, Labruna M B. “Candidatus Borrelia ibitipoquensis,” a Borrelia valaisiana–related genospecies characterized from Ixodes paranaensis in Brazil. Microbial Ecol. 2020; 80: 682–689. doi: 10.1007/s00248-020-01512-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suarez CE, Noh S. Emerging perspectives in the research of bovine babesiosis and anaplasmosis. Vet Parasitol. 2011; 180(1–2): 109–125. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2011.05.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Garcia K, Weakley M, Do T, Mir S. Current and future molecular diagnostics of tick-borne diseases in cattle. Vet Sci. 2022; 9(5): 241. doi: 10.3390/vetsci9050241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Napp S, Chevalier V, Busquets N, Calistri P, Casal J, Attia M, et al. Understanding the legal trade of cattle and camels and the derived risk of rift valley fever introduction into and transmission within Egypt. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2018; 12: e0006143. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abdelbaset A, Hamed M, Abushahba M, Rawy M, Sayed AS, Adamovicz J. Toxoplasma gondii seropositivity and the associated risk factors in sheep and pregnant women in El-Minya Governorate, Egypt. Vet World. 2020; 13: 54. doi: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kilpatrick A, Dobson A, Levi T, Salkeld D, Swei A, Ginsberg H, et al. Lyme disease ecology in a changing world: consensus, uncertainty and critical gaps for improving control, Philos. Trans R Soc Lond Ser B Biol Sci. 2017; 372. doi: 10.1098/RSTB.2016.0117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hoogstraal H, Kaiser MN. Ticks from European-asiatic birds migrating through Egypt into Africa. Science. 1961; 133: 277–278. doi: 10.1126/science.133.3448.277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hoogstraal H, Kaiser MN, Traylor MA, Guindy E, Gaber S. Ticks (Ixodidae) on birds migrating from Europe and Asia to Africa, 1959–61. Bull World Health Organ. 1963; 28: 235–262. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hoogstraal H, Traylor MA, Gaber S, Malakatis G, Guindy E, Helmy I. Ticks (Ixodidae) on migrating birds in Egypt, spring and fall 1962. Bull World Health Organ. 1964; 30: 355–367. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Galbraith CA, Jones T, Kirby J, Mundkur T, Ana A, García B, et al. UNEP / CMS Secretariat. C Tech Ser. 2014; 164. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Abdelbaset AE, Nonaka N, Nakao R. Tick-borne diseases in Egypt: A one health perspective. One Health. 2022; 15: 100443. doi: 10.1016/j.onehlt.2022.100443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mosabah AAA, Morsy TA. Tick paralysis: First zoonosis record in Egypt. J Egypt Soc Parasitol. 2012; 42 (1): 71–78. doi: 10.12816/0006296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Michael SA, Morsy TA, Montasser MF. A case of human babesiosis (Preliminary case report in Egypt). J Egypt Soc Parasitol. 1987; 17(1): 409–410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.El-Bahnasawy MM, Morsy TA. Egyptian human babesiosis and general review. J Egypt Soc Parasitol. 2008; 38(1): 265–272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hammouda NA, Hegazy IH, El-Sawy EH. ELISA screening for Lyme disease in children with chronic arthritis. J Egypt Soc Parasitol. 1995; 25(2): 525–533. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.El-Bahnasawy MM, Mosabah AAA, Saleh HAA, Morsy TA. The tick-borne Crimean–Congo hemorrhagic fever in Africa, Asia, Europe, and America: What about Egypt? J Egypt Soc Parasitol. 2012; 42(2): 373–384. doi: 10.12816/0006324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Perveen N, Muzaffar SB, Al-Deeb MA. Ticks and tick-borne diseases of livestock in the Middle East and North Africa: A review. Insects. 2021; 12(1): 83. doi: 10.3390/insects12010083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schnittger L, Rodriguez AE, Florin-Christensen M, Morrison DA. Babesia: a world emerging. Infect Genet Evol. 2012; 12(8): 1788–809. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2012.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schreeg ME, Marr HS, Tarigo JL, Cohn LA, Bird DM, Scholl EH, et al. Mitochondrial genome sequences and structures aid in the resolution of piroplasmida phylogeny. PLoS One. 2016; 11(11): e0165702. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0165702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Andersson MO, Marga G, Banu T, Dobler G, Chitimia-Dobler L. Tick-borne pathogens in tick species infesting humans in Sibiu County, central Romania. Parasitol Res. 2018; 117(5): 1591–1597. doi: 10.1007/s00436-018-5848-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dong J, Olano JP, McBride JW, Walker DH. Emerging pathogens: challenges and successes of molecular diagnostics. J Mol Diagn. 2008; 10(3): 185–97. doi: 10.2353/jmoldx.2008.070063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Uilenberg G, Gray J, Kahl O. Research on piroplasmorida and other tick-borne agents: Are we going the right way? Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2018; 9(4): 860–863. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2018.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Springer A, Glass A, Topp AK, Strube C. Zoonotic tick-borne pathogens in temperate and cold regions of Europe- A review on the prevalence in domestic animals. Front Vet Sci. 2020; 7: 604910. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2020.604910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mans BJ, Venzal JM, Muñoz-Leal S. Editorial: Soft ticks as parasites and vectors. Front Vet Sci. 2022; 9: 1037492. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2022.1037492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dantas-Torres F, Chomel BB, Otranto D. Ticks and tick-borne diseases: a One Health perspective. Trends Parasitol. 2012; 28(10): 437–46. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2012.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Central Agency for Public Mobilization and statics (CAPMAS), Egypt Informatics Monthly Statistical Bulletin 2021; 109. Available from: https://www.capmas.gov.eg/Pages/IndicatorsPage.aspx?Ind_id=2370.

- 51.El Kenawy AM, Lopez–Moreno JI, McCabe MF, Robaa SM, Domínguez–Castro F, Peña–Gallardo M, et al. Daily temperature extremes over Egypt: Spatial patterns, temporal trends, and driving forces. Atmos Res. 2019; 226: 219–239. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosres.2019.04.030 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Elmenofi GAG EL Bilali H, Berjan S. Governance of rural development in Egypt. Ann Agric Sci. 2014; 59(2): 285–296. doi: 10.1016/j.aoas.2014.11.018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson AR. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci. USA. 1977; 74(12): 5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kimura M. A simple method for estimating evolutionary rate of base substitutions through comparative studies of nucleotide sequences. J Mol Evol. 1980; 16: 111–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tamura K, Nei M. Estimation of the number of nucleotide substitutions in the control region of mitochondrial DNA in humans and chimpanzees. Mol Biol Evol. 1993; 10:512–526. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tamura K, Kumar S. Evolutionary distance estimation under heterogeneous substitution pattern among lineages. Mol Biol Evol. 2002; 19:1727–1736. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a003995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kishino H, Hasegawa M. Evaluation of the maximum likelihood estimate of the evolutionary tree topologies from DNA sequence data, and the branching order in Hominoidea. J Mol Evol. 1989; 29:170–179. doi: 10.1007/BF02100115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]