Abstract

The present study seeks to explore the intersectionality of ethnicity/race and socioeconomic status (SES) among ethnic/racial minority adolescents in their developmental contexts, examining its implications for sleep disparities and the roles of discrimination and ethnic/racial identity (ERI; i.e., adolescents’ understanding and feelings about who they are in relation to their ethnic/racial group). With 350 adolescents (Asian 41.4%, Black, 21.7%, and Latinx 36.9%, female = 69.1%, Mage = 14.27), we conducted a latent class analysis (LCA) to identify latent classes of adolescents’ ethnicity/race, ethnic/racial diversity in their schools and neighborhoods along with SES of their families, schools, and neighborhoods. Next, with hierarchical regression, we tested the association between class membership and subjective and objective sleep duration and quality, followed by the moderating effect of discrimination and ERI. We expected to find adolescents living in low diversity and low SES across various developmental contexts to experience lower levels of subjective and objective sleep duration and quality compared to their counterparts. We also expected to find exacerbating effects of discrimination and ERI exploration, and protective effects of ERI commitment in these associations. Three latent groups were identified (C1: “Black/Latinx adolescents in low/moderate SES families in varying diversity and low SES schools and neighborhoods,” C2: “Predominantly Latinx adolescents in low SES families and moderate diversity and SES schools and neighborhoods,” and C3: “Predominantly Asian adolescents in low/moderate SES families in moderate/high diversity and SES schools and neighborhoods”). The class memberships to C1 and C2 were associated with compromised sleep duration and quality compared to C3. An interaction effect of discrimination was found for C1 in subjective sleep duration and for C2 in objective sleep duration. While no interactions were found for ERI, ERI commitment had a direct association with objective sleep duration and quality. Interpretations and implications for intersectionality approach in studies on sleep disparities and the roles of discrimination and ERI are discussed.

1. Introduction

Sleep plays an essential role in the healthy development of children and adolescents. At the national level, the U.S. government is working to promote public knowledge and awareness of the importance of adequate sleep for general health and well-being. Acknowledging declines in sleep starting in adolescence, there has been a concerted effort to encourage adolescents to get adequate duration and quality sleep as part of the Healthy People 2020 public health initiative (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2011). According to the National Sleep Foundation, both sleep duration and quality are important indicators of children’s and adolescents’ sleep hygiene. Sleep recommendations for children between ages 6 and 13 are 9–11h per night, while 8–10h is recommended for those who are between ages 14 and 17. Being able to sleep through the night without waking up in the middle or subjective feeling of having slept well in the morning are a few indicators of good sleep quality.

Insufficient and poor-quality sleep are associated with increased chances of being overweight, lower levels of academic achievement, and experiencing impairment in cognitive functioning and emotional regulation (Baum et al., 2014; Beebe, Rose, & Amin, 2010; Miller, Seifer, Crossin, & Lebourgeois, 2014; Neblett, Philip, Cogburn, & Sellers, 2006; Sadeh, Gruber, & Raviv, 2003; Snell, Adam, & Duncan, 2007). Scholars have attempted to identify the factors that contribute to children’s and adolescents’ sleep, and recent studies are finding disparities in sleep among ethnic/racial minority and among low socioeconomic status (SES) groups (Buckhalt, El-Sheikh, & Keller, 2007; Guglielmo, Gazmararian, Chung, Rogers, & Hale, 2018; Hoyniak et al., 2018; Kelly & El-Sheikh, 2018; Yanagi, Fujiwara, Hata, & Kondo, 2017). Independently, ethnicity/race and SES have been found to be associated with sleep disturbances, and the effects of each are still evident after adjusting for the other (Hicken, Lee, Ailshire, Burgard, & Williams, 2013). However, less research has systemically explored the ways in which ethnicity/race and SES come together to contribute to sleep disparities. The present study seeks to address this gap by first exploring the intersectionality of ethnicity/race and SES and examining its associations with sleep and the roles of discrimination and ethnic/racial identity (ERI; i.e., understanding and feelings about one’s ethnic/racial group membership).

1.1. Theoretical framework

1.1.1. Intersectionality framework

The intersectionality framework pays attention to the possibility of developing multiple identities across various domains of status (Crenshaw, 1989), such as ethnicity/race, gender, sexuality, SES, age, and religion (Dhamoon & Hankivsky, 2011). This perspective suggests that an adolescent may experience various combinations of privileges and oppressions across multiple identity domains. In other words, the experience and meaning of advantages and disadvantages may be qualitatively different for individuals at different intersections of multiple identities. Particularly, overlapping disadvantaged statuses across multiple domains, such as ethnicity/race and SES are likely to produce differences in one’s experience of marginalization, discrimination (Arellano-Morales et al., 2015) and health (Bowleg, 2012), including sleep.

Previously, efforts to capture the concept of intersectionality in systematic analyses of health outcomes have largely adopted variable-centered approaches to examine interactions among different factors, without considering holistic combinations of these factors (Assari, 2017; Ciciurkaite & Perry, 2018; Ward et al., 2004). More recent studies have adopted person-centered approaches (Bergman & Magnusson, 1997) to consider combinations or overlaps of multiple (dis)advantages to examine the intersectionality of ethnicity/race and SES (Gazard et al., 2018; Goodwin et al., 2018; Landale, Oropesa, & Noah, 2017). For example, in Goodwin et al. (2018) and Gazard et al. (2018) six subgroups of adults who were at different intersections of ethnicity/race and SES were identified and displayed different levels of privilege and disadvantage in the prevalence of having common mental disorder. In Landale et al. (2017), intersectionality approach was taken to examine discrimination experiences among Latino adults (age < 30: 26.6%) and they found different levels of discrimination experiences at different intersections of legal status and SES. All of these studies have highlighted promising benefits of person-centered approach in capturing intersectionality by classifying nuanced subgroups with similar patterns within their analytic sample. However, these studies were mainly focused on the adult populations and very little is known about the development of adolescents at varying intersections of ethnicity/race and SES. Building off of this line of research, the current study seeks to capture the intersectionality of ethnicity/race and SES using a person-centered approach and focusing on ethic/racial minority adolescents.

1.1.2. Ecological systems theory

In capturing the intersectionality of ethnicity/race and SES, the current study places the intersectionality framework within the ecological systems perspective (Bronfenbrenner, 1979), which views a person’s development occurring as a product of individual characteristics and the inseparable surrounding environmental characteristics. For adolescents, the most developmentally influential environments include family, school, and neighborhood (Eccles et al., 1993). As we examine the intersectionality of ethnicity/race and SES, we take into consideration the experience of ethnicity/race and SES at these multiple levels of influence. This way, it becomes possible to identify and specify not only children and adolescents’ ethnic/racial background and family SES, but also the ethnic/racial diversity and SES of their schools and neighborhoods. Adolescents’ ethnic/racial experiences and related development interact as embedded in multiple layers of ecological systems (Yip, Cheon, & Wang, 2019). From the intersectionality perspective, it is likely that adolescents living in disadvantaged families, schools, and neighborhoods characterized by low SES and segregation would exhibit the worst developmental outcomes. However, there is insufficient evidence to hypothesize how different levels of diversity at schools and neighborhoods might contribute to sleep disparities in ethnic/racial minority youth. As a result, we attempted to delineate the subgroups of adolescents based on individual ethnicity/race, SES of the family, school, and neighborhood and ethnic/racial diversity in these schools and neighborhoods. Guided by the intersectionality framework (Crenshaw, 1989) and ecological systems theory (Bronfenbrenner, 1979), the current study extends the existing knowledge by taking a person-centered approach that views each adolescent at the intersection of ethnicity/race and SES embedded in varying levels of ecological contexts.

1.2. Ethnicity/race and sleep

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s report on sleep and sleep disorders, a higher percentage of individuals having short sleep duration (<7h) was observed among Blacks relative to the White, Latinx, and Asians (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2017). In a recent literature review of racial/ethnic sleep disparities in the United States school-aged children and adolescents, Guglielmo et al. (2018) examined 23 studies and found ethnic/racial disparities across all studies in at least one sleep measure. Specifically, 17 out of 18 studies that examined sleep duration found that, compared to White youth, Black and Latinx youth slept shorter hours, while findings were mixed among the Asian group (e.g., Combs, Goodwin, Quan, Morgan, & Parthasarathy, 2016; Hawkins & Takeuchi, 2016; Keyes, Maslowsky, Hamilton, & Schulenberg, 2015; Matthews, Hall, & Dahl, 2014; Organek et al., 2015; Williams, Zimmerman, & Bell, 2013). Not many studies examined differences among ethnic/racial minority groups (i.e., Asian compared to Black compared to Latinx), but those that did explore differences observed the shortest sleep duration among Black compared to Latinx youth (Wong et al., 2013). In terms of sleep quality, studies that compared differences between ethnic/racial minority groups have been scarce, and existing studies find that White youth generally report more frequent sleep/wake difficulties than ethnic/racial minority youth (Guglielmo et al., 2018).

The current literature on differences in sleep duration and quality among ethnic/racial minority groups is limited and mixed. Moreover, none of these studies to our knowledge considered children and adolescents’ ethnicity/race within the context of ethnic/racial composition of important developmental contexts such as schools and neighborhoods. The consideration of children and adolescents’ ethnicity/race in the context of school and neighborhood diversity is important as studies have found that neighborhood conditions play a critical role in children and adolescents’ sleep (e.g., safety, disadvantage, social cohesion, violence; Chambers, Pichardo, & Rosenbaum, 2016; Johnson, Brown, Morgenstern, Meurer, & Lisabeth, 2015; Johnson et al., 2016).

1.3. Socioeconomic status (SES) and sleep

In addition to disparities among ethnic/racial minority groups, SES is another axis where sleep duration and quality are different. Previous studies have found more sleep problems among low-SES children (El-Sheikh et al., 2013; Gellis, 2011; Kelly, Kelly, & Sacker, 2013). El-Sheikh et al. (2013) explored multiple SES indicators, such as income-to-needs ratio, perceived economic well-being, maternal education, and community poverty, and lower-income-to-needs ratios were associated with more sleep-wake problems, whereas perceived economic well-being was related to shorter sleep duration and more sleep onset variability. In addition, lower levels of mother’s education were related to lower levels of sleep efficiency; and finally, children attending Title 1 schools (i.e., having at least 40% low income students) had lower sleep duration. Sleep disturbances among low SES youth and families have been attributed to noisy and uncomfortable environments (Stepanski & Wyatt, 2003) and less awareness of the importance of sleep among parents with lower levels of education (Winkleby, Jatulis, Frank, & Fortmann, 1992).

The current research builds upon these existing literature by considering the intersection of ethnicity/race and SES within family, school, and neighborhood contexts. As implied by the cumulative risk hypothesis (Rutter, 1979), the accumulation of risk factors may place adolescents at greater developmental risks. For example, how might adolescents from low SES families, in low SES neighborhoods, and attending low SES schools sleep differently from adolescents from low SES families, in middle SES neighborhoods, and attending middle SES schools? The present study takes a holistic approach to investigating these multiple contexts and attempts to integrate previous findings on the role of SES at multiple ecological levels.

1.4. Discrimination and sleep: At the intersection of ethnicity/race and SES

At the intersection of ethnicity/race and SES, research on adults suggests that disparities along these axes may involve the experience of discrimination (Williams, 1999). Discrimination is unequal treatment toward members of certain groups by individuals and society based on the belief that these groups are inferior (Williams, 1999). Biopsychosocial model posits that the experience of stress such as discrimination threatens one’s health and well-being (Clark, Anderson, Clark, & Williams, 1999). Particularly for sleep, the experience of discrimination may heighten individuals’ alertness and disrupt sufficient and quality sleep (Majeno, Tsai, Huynh, McCreath, & Fuligni, 2018). As the United States increases in ethnic/racial diversity, race and discrimination are salient issues for the American population (Scott, 2018). Furthermore, sleep among children and adolescents is an increasing public health concern (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2011); therefore, developmental science must continue to unpack the role of discrimination in sleep among ethnic/racial minority adolescents.

Among adults, the experience of discrimination, which is a type of stress, has been suggested as one of the influential factors that disrupts sleep of individuals in ethnic/racial minority and low SES groups (Hicken et al., 2013; Slopen, Lewis, & Williams, 2016; Stamatakis, Kaplan, & Roberts, 2007; Williams & Mohammed, 2009). These studies have generally found shorter sleep duration and lower sleep quality among low-income, Black, and Latinx individuals compared to middle to high income and White individuals, and found that racial disparities between Black and White adults slightly diminished after controlling for SES, and evaporated when racism-related vigilance was considered (Hicken et al., 2013). Although these studies have revealed the independent and additive effects of ethnicity/race and SES, it has still been difficult to pinpoint whose sleep may be most affected by discrimination in what ways as ethnicity/race and SES do not exist separately; rather, individuals are embedded in various combinations of ethnicity/race and SES at multiple levels of their ecological environments.

Moreover, most of the existing evidence comes from studies conducted on adults and only a few studies examined the role of discrimination in sleep among adolescents. In a few studies that have looked at children, they found ethnic discrimination to be related to shorter objective sleep duration, nonethnic discrimination to be related to worse subjective sleep quality among diverse adolescents including Latinx, White, Asian, and other ethnic background (Majeno et al., 2018). In Yip (2015), discrimination was negatively correlated with self-reported daily sleep quality among diverse adolescents from Black, Latinx, Asian, and White backgrounds.

In an effort to examine the intersection of ethnicity/race and SES, we focus on the role of everyday discrimination, not delineating between various forms or sources of discrimination (e.g., discrimination due to race, SES), and various measures of sleep. We will examine how the role of discrimination in sleep may vary by individual membership to latent classes of ethnicity/race and SES (Goosby, Straley, & Cheadle, 2017). Based on studies conducted among adults and well-established theories, we expect to find that discrimination will compromise both subjective and objective measures of sleep duration and quality. We also hypothesize that the experience of discrimination will have a more exacerbating effect on the sleep of the adolescents in multiple disadvantaged environments (i.e., family, school, neighborhood) than those who are in more advantaged conditions.

1.5. Ethnic/racial identity (ERI) and sleep: At the intersection of ethnicity/race and SES

In an effort to address the current needs for identifying modifiable contributors to sleep disparities (Guglielmo et al., 2018), we consider the role of ERI, which may buffer or exacerbate the effect of disadvantages experienced by the ethnic/racial minority adolescents across SES. Adolescence is a period of active identity development (Meeus, Iedema, Helsen, & Vollebergh, 1999). ERI is an aspect of identity that reflects one’s association with ethnic/racial group and its development occurs through exploration and commitment (Phinney & Ong, 2007). ERI exploration involves active search of one’s ethnic/racial group membership through asking questions or talking to others about their ethnic/racial group membership and participating in ethnic/racial activities. ERI commitment reflects the extent to which one feels attached or personally invested in their ethnic/racial group (Phinney & Ong, 2007). Both of these processes may interact with the intersections of ethnicity/race and SES to influence sleep (Lee, 2005; Rivas-Drake, Hughes, & Way, 2008; Yip, 2018). Yip (2018) has highlighted how the impact of ERI may be manifested differently for different ethnic/racial groups. Building upon their findings and suggestions, we wanted to see how ERI may have differential impact at different intersections of ethnicity/race and SES. Again, although different latent classes of ethnicity/race and SES will demonstrate different patterns, ERI exploration is expected to exacerbate the effects of multiple marginalized statuses on sleep (Torres & Ong, 2010). On the other hand, based on studies that have found a protective effect (Romero, Edwards, Fryberg, & Orduña, 2014; Stein, Kiang, Supple, & Gonzalez, 2014; Yip, Wang, Mootoo, & Mirpuri, 2019), ERI commitment is hypothesized to buffer the negative impact of multiple marginalization at the intersection of ethnicity/race and SES on sleep.

1.6. Current study

First, the current study identifies distinct subgroups of adolescents based on ethnicity/race and SES. Based on intersectionality framework and ecological systems theory, adolescents’ ethnicity/race, family SES, school diversity and SES, and neighborhood diversity and SES are included in the creation of latent classes. Next, we examine the associations between class membership and subjective and objective measures of sleep duration and quality, followed by the examination of interaction effects of discrimination and ERI. This study will offer a novel perspective to systematically and quantitatively test the intersectionality of ethnicity/race and SES among ethnic/racial minority adolescents and its associations with sleep health. Our findings will also provide helpful information for designing policies and programs to consider discrimination and ERI as potential risk and resilience factors for these associations.

2. Methods

2.1. Data and participants

The data in this study come from the first-year data of an on-going longitudinal study examining adolescents’ daily experiences and their development. This study was conducted among 9th grade students in five public high schools in a large metropolitan city in the northeastern part of the United States beginning in 2015. This data included a total of 350 ethnic/racial minority adolescents from Asian (41.4%), Black (21.7%), and Latinx (36.9%) backgrounds and their ages ranged from 13 to 17 (M = 14.27, SD = 0.61). There were 69.1% female and 30.9% male, 51.7% were born in the United States. Participants were given the option to indicate a non-binary sex other than female or male, however, no adolescents selected this option.

2.2. Procedures

Sampling first occurred at the level of school. Schools were selected for having various levels of school ethnic/racial diversity (Simpson’s Diversity Index School A: 0.55, School B: 0.51, School C: 0.29, School D: 0.36, School E: 0.62). Next, all 9th grade students from Asian, Black, and Latinx backgrounds as indicated by Department of Education statistics were invited to participate in the study and consent forms were mailed to students’ home addresses and placed in school mailboxes. Participating adolescents were first asked to complete an online demographic survey. Then, they were asked to wear an actigraphy watch (Ambulatory Monitoring, Motionlogger) for 14 consecutive days, completing nightly daily diaries on those same 14 days. Adolescents completed daily diaries each night before going to bed and answered questions about the day’s experiences and previous night’s sleep.

2.3. Measures

Ethnicity/race:

Self-reported ethnicity/race was coded Asian=1, Black=2, Latinx=3 and treated as a categorical variable.

Nativity:

In order to consider ethnic/racial minority adolescents’ immigration status, self-reported nativity was coded US-born=1, foreign-born=0.

Socioeconomic status (SES):

SES was estimated using three parameters: Family, school, and neighborhood.

Family SES:

Parents’ education level was used as a proxy for family SES. Participants reported on their father’s and mother’s highest level of education using three categories. Those who completed high school or less were coded “low (father: N=125, 35.7%; mother: N = 125, 35.7%),” having completed some college or 2-year college to 4-year college was coded as “middle (father: N=58, 16.6%; mother: N=93, 26.6%),” and having completed graduate or professional degrees was coded as “high (father: N=24, 6.9%; mother: N=25, 7.1%).”

School SES:

Students were recruited from five public schools. Information about each school’s percentage of students living in families below federal poverty line was retrieved from the Department of Education website. The number ranged from 21.4% to 37.2% (M=25.5, SD=10.43). School SES was categorized: schools with 20% or fewer families below the poverty line were coded “high SES (N = 187, 53.4%)” those that were below 30% were coded “middle SES (N=54, 15.4%),” and those above 30% were coded “low SES (N=109, 31.1%).” The inclusion in each category was mutually exclusive. According to this categorization, one school was coded “high SES,” two schools were coded “middle SES” and two schools were coded “low SES.” “Low” indicates low SES or a high percentage of students living under federal poverty level.

Neighborhood SES:

Adolescents’ home addresses were geocoded to correspond with the United States census tracts. Using the United States Census data, neighborhood SES was coded for the percentage of individuals living below poverty level within the census tract. The percentage ranged from 3.4% to 46.4%. The quartiles were 25%=10.20%, 50%=17.50%, and 75%=29.35%. Neighborhood SES was categorized: census tracts with 10.20% or less families living below the federal poverty line were coded “high SES (N=82, 23.4%),” above 10.20% and below or equal to 29.35% were coded “middle SES (N=170, 48.6%),” and neighborhoods above 29.35% of individuals living below poverty level were coded “low SES (N=81, 23.1%).”

Ethnic/racial Diversity:

Ethnic/racial diversity was estimated using two parameters: school and neighborhood.

School diversity:

School diversity was assessed by the information on the school ethnic/racial composition provided in the Department of Education website. This data from the website were used to compute Simpson’s diversity index (Simpson, 1949), which is a calculation of probability that two randomly selected individuals in each school are from different ethnic/racial groups. The index ranges from 0 to 1, with higher scores indicating higher levels of diversity (School A: 0.55, School B: 0.51, School C: 0.29, School D: 0.36, School E: 0.62). Since there were only five schools, categories were determined as relative to one another. Those falling under 0.30 was coded “low diversity (N=76, 21.7%),” those that were between 0.30 and 0.40 were coded “middle diversity (N=30, 8.6%),” and those that were above 0.40 were coded “high diversity (N=109, 31.1%).

Neighborhood diversity:

Adolescents’ home addresses were geocoded to correspond with the United States census tracts. Using the United States Census data, neighborhood diversity was coded using Simpson’s diversity index (Simpson, 1949) based on the total number of individuals within each census tract and the total count of individuals from each ethnic/racial group in each census tract. The diversity index ranged from 2% to 76%. The quartiles were 25% = 0.46 (i.e., there is a 46% chance that two randomly selected individuals from this census tract are from different ethnic/racial groups), 50% = 0.58, 75% = 0.68. The census tracts with diversity below or equal to 0.46 were coded “low diversity (N=82, 23.4%),” those above 0.46 and below or equal to 0.68 were coded “middle diversity (N=170, 48.6%),” and anywhere above 0.68 were coded “high diversity (N=81, 23.1%).”

Subjective and objective measures of sleep:

Guglielmo et al. (2018) have extensively reviewed ethnic/racial disparities in sleep and have taken note of the fact that most of previous studies measured sleep with self-reports, while a few studies used objective instruments and even fewer studies used both measures. As some studies conducted with adults have found discrepancies between subjective and objective measures (Baker, Maloney, & Driver, 1999; Bastien et al., 2003), which suggest that the two may have different implications, these studies have recommended the use of multiple measures (Sadeh, 2011; Van Den Berg et al., 2008). Therefore, based on these studies’ recommendation, we examine both subjective and objective measures of sleep.

Subjective sleep:

Participants’ perceptions of sleep duration and sleep quality were measured by Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (Buysse, Reynolds, Monk, Berman, & Kupfer, 1989). Sleep duration was asked: “During the past month, how many hours of sleep did you get at night?” “Greater than 7h” was coded 0, “6–7h” = 1, “5–6h” = 2, and “Less than 5h” = 3. These scores have been reverse-coded so that greater numbers indicated greater amounts of subjective sleep. Sleep quality was measured by: “During the past month, how would you rate your overall sleep quality.” A response of “Very Good” = 0, “Fairly Good” = 1, “Fairly Bad” = 2, and “Very Bad” = 3. These scores have also been reverse-coded so that greater numbers indicated better sleep quality. This measure has been used widely and validated in diverse samples of adolescents (Brand, Gerber, Hatzinger, Beck, & Holsboer-Trachsler, 2009; George & Davis, 2013; Lang et al., 2013).

Objective sleep:

Objective indicators of sleep were captured by the Motionlogger actigraph wrist watch, which uses both the accelerometer and heart rate monitor for the assessment of sleep and wake states. The participating adolescents wore the watch for 14 consecutive days and data were downloaded from each watch and analyzed with Sadeh’s algorithm (Sadeh, 2011). Each sleep-wake file was compared to the self-reported sleep and wake times and coded by one of three research assistants. All three research assistants coded the same first 20 files to discuss discrepancies and eventually obtained inter-rater reliability that ranged from ICC = 0.85 to ICC = 0.90. Thereafter, every 10th file was coded by two research assistants and the mean inter-rater reliability between the two research assistants coding the same files was high (M = 0.92, SD = 0.07). While many sleep-related measures are detected and calculated through this program, this study focuses on sleep duration and wake minutes after sleep onset (WASO, as a measure of objective sleep quality). Sleep duration refers to the total minutes between the time that adolescents fell asleep to the time that they woke up (M = 462.09, SD = 51.88). WASO is a sum of minutes that the adolescents woke up between the time that they fell asleep and woke up (M = 27.85, SD = 17.44). The mean of 14-day reports was used for the analysis. The reliability across 14 days was 0.73 for duration and 0.79 for WASO.

Discrimination:

Discrimination was measured by the Everyday Discrimination Scale (Williams, Yu, Jackson, & Anderson, 1997). The participants were asked, “In your day-to-day life IN THE PAST SIX MONTHS, how often have any of the following things happened to you?” Five incidents of discrimination such as, “You were treated with less courtesy or respect than other people” were presented and the participants responded to each incident on a 6-point Likert scale (“Never” = 1, “Rarely” = 2, “Sometimes” = 3, “Often” = 5, “Very Frequently” = 6). A mean across the five incidents was taken. However, due to a large number of participants responding “never” to all five incidents, this variable has been dummy-coded as 0 = reports of “never” across all incidents and 1 = report of any degree of experience in any incident. The reliability was 0.80. Ethnic/racial identity: Ethnic/racial identity was measured by the Multidimensional Ethnic Identity Measure (Phinney, 1992). Two subscales, exploration and commitment, were scored separately. Exploration included five items such as “I have spent time trying to find out more about my ethnic group, such as its history, traditions, and customs.” Commitment included seven items such as “I feel a strong attachment towards my own ethnic group.” The responses were coded as “strongly agree” = 1 to “strongly disagree” = 4. One reverse-coded item from each subscale was excluded due to issues in measuring the construct as suggested by Phinney and Ong (2007). The reliability of exploration was 0.79, and it was 0.92 for commitment.

Covariates

Age:

Participants’ age was measured using an open-ended item (M = 14.27, SD = 0.61).

Positive, negative and anxious mood:

As both sleep duration and quality have often been found to be closely associated with mood (Fuligni & Hardway, 2006; Thomsen et al., 2003), various mood states were included as covariates. Negative and anxious mood were measured by the Profiles of Mood States (McNair, Loor, & Droppleman, 1971). Since the POMS does not include a positive mood scale, one was developed by the authors. The three subscales, tension/anxiety (anxious, nervous, unable to concentrate, on edge), positive mood (happy, calm, joyful, excited), and negative mood (sad, hopeless, discouraged, blue) were scored separately. The responses were coded as “not at all” = 1, “a little” = 2, “moderately” = 3, “quite a lot” = 4, “extremely” = 5. The reliability of positive mood was 0.79, negative mood was 0.84, and it was 0.72 for tension/anxiety.

2.4. Analytic strategy

Step 1: Latent Class Analysis (LCA)

Latent Class Analysis (LCA) was conducted using Mplus 7.3 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2012). LCA is a useful method for identifying nuanced subgroups with similar underlying patterns among study participants. LCA is a person-centered approach based on a measurement model that is exploratory in nature. Whereas variable-centered approach provides variable-by-variable information, a person-centered approach assumes that the true underlying subgroups are not directly observable and infer the associations between observable characteristics. A series of statistical models are examined to determine the ideal number of latent classes that describe differences among the participants’ responses in observable characteristics (Scharoun-Lee et al., 2011). For each subgroup, LCA provides information about the number of study participants who are likely to fall under each group as well as the probability of each participant’s membership to each subgroup (Scharoun-Lee et al., 2011).

In this study, LCA was used to derive subgroups of underlying patterns of participants’ ethnicity/race and SES in multiple ecological contexts. All profiling variables were transformed into categorical variables (i.e., “low,” “middle,” or “high”). A total of nine categorical variables (i.e., ethnicity/race, gender, nativity, mother’s education level, father’s education level, school ethnic/racial diversity level, school poverty rate, neighborhood ethnic/racial diversity level, and neighborhood poverty rate) were included and contributed to forming latent classes. This way, latent classes demonstrate higher-order associations among the nine variables than the independent characteristics of each variable and holistically reflect profiles in various combinations of ethnicity/race and SES (Landale et al., 2017).

Statistical models are tested with a given number of subgroups starting from one group with an increment of one. The fit indices Akaike’s Information Criterion (AIC; Akaike, 1987), Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC; Schwartz, 1978), Adjusted Bayesian Information Criterion (ABIC), and entropy are compared. Generally, a decrease in AIC, BIC, ABIC indicate better fit and entropy values above 0.8 are considered appropriate. The number of subgroups is generally selected where the decrease in AIC, BIC, and ABIC starts to plateau. Moreover, the tests of Voung-Lo-Mendell-Rubin Likelihood Ratio Test (VLMR-LRT), Lo-Mendell-Rubin Adjusted Likelihood Ratio Test (adjusted LMR) and Bootstrapped Likelihood Ratio Test (BLRT) provide P-values that indicate whether having k number of subgroups significantly improves the model fit compared to having k-1 number of subgroups (Lo, Mendell, & Rubin, 2001; Tofighi & Enders, 2008). The final number of subgroups are selected based on the seven criteria with the consideration of interpretability (Enders & Tofighi, 2007; Lo et al., 2001).

Step 2: Multiple hierarchical regression: Latent class profiles, sleep, discrimination, and ERI

As the second step, the LCA class memberships were dummy-coded with the largest group as the designated reference group. Separate regression models were estimated with subjective sleep duration, subjective sleep quality, objective sleep duration and objective sleep quality (WASO) as respective outcome variables. For each outcome variable, the first model of hierarchical multivariable regression included the main effects of LCA class membership (i.e., dummy-coded class membership) with age, positive, negative, and anxious mood as covariates. The second model added discrimination, and ERI exploration and commitment in the equation. Finally, the third model included two-way interactions between LCA class membership and discrimination, LCA class membership and ERI exploration and LCA class memberships and commitment.

3. Results

3.1. Correlations

Significant correlations between study variables were found (Table 1). Asian participants experienced higher levels of discrimination, had fathers with higher education level, attended more diverse schools with higher levels of SES, lived in neighborhoods with low poverty, had longer subjective sleep durations, and reported shorter minutes waking up during the night after sleep onset compared to other ethnic/racial groups. Black participants, compared to other ethnic/racial groups, had mothers with higher education levels, attended less diverse schools with lower levels of SES, lived in neighborhoods with less diversity with lower levels of SES, and reported longer minutes waking up during the night after sleep onset. Latinx participants had mothers and fathers with lower education levels, attended less diverse schools with higher levels of poverty (low levels of SES), lived in neighborhoods with higher diversity and with higher poverty (low SES); and reported shorter subjective and objective sleep durations.

Table 1.

Bivariate correlations between study variables.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Asian | – | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 2. Black | – | – | |||||||||||||||||||

| 3. Latinx | – | – | – | ||||||||||||||||||

| 4. Age | 0.03 | −0.01 | −0.02 | – | |||||||||||||||||

| 5. Gender | 0.08 | −0.01 | −0.07 | 0.04 | – | ||||||||||||||||

| 6. Nativity | −0.05 | −0.07 | 0.10 | 0.05 | 0.13* | – | |||||||||||||||

| 7. Positive Mood | −0.00 | 0.09 | −0.07 | −0.02 | 0.06 | −0.07 | – | ||||||||||||||

| 8. Negative Mood | 0.00 | −0.06 | 0.05 | 0.06 | −0.12* | −0.05 | −0.27** | – | |||||||||||||

| 9. Anxious Mood | 0.09 | −0.09 | −0.02 | −0.02 | −0.12* | −0.06 | −0.12* | 0.65** | – | ||||||||||||

| 10. EDS - Discrimination | 0.14* | −0.09 | −0.07 | −0.02 | −0.02 | −0.03 | −0.12* | 0.23** | 0.25** | – | |||||||||||

| 11. ERI - Exploration | 0.04 | −0.07 | 0.02 | −0.02 | −0.19** | −0.01 | 0.20** | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.04 | – | ||||||||||

| 12. ERI - Commitment | −0.03 | −0.05 | 0.07 | −0.07 | −0.09 | 0.03 | 0.28** | 0.03 | 0.03 | −0.01 | 0.74** | – | |||||||||

| 13. Mother’s Education Level | 0.05 | 0.13* | −0.16* | −0.05 | −0.01 | −0.02 | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.01 | −0.00 | 0.11 | 0.15* | – | ||||||||

| 14. Father’s Education Level | 0.14* | 0.06 | −0.19** | −0.08 | 0.04 | −0.26** | −0.07 | −0.02 | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.49** | – | |||||||

| 15. School Diversity | 0.45** | −0.26** | −0.24** | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.16* | −0.11* | −0.06 | 0.05 | 0.05 | −0.04 | −0.09 | 0.09 | 0.12 | – | ||||||

| 16. School Poverty | −0.64** | 0.44** | 0.28** | −0.07 | −0.02 | −0.11 | 0.04 | 0.03 | −0.11* | −0.11* | −0.03 | 0.01 | −0.05 | −0.12 | −0.75** | – | |||||

| 17. Neighborhood Diversity | −0.10 | −0.28** | 0.34** | −0.07 | 0.06 | 0.13* | 0.05 | 0.04 | −0.07 | 0.00 | −0.04 | 0.04 | −0.14* | −0.12 | 0.20** | 0.15** | – | ||||

| 18. Neighborhood Poverty | −0.47** | 0.29** | 0.24** | −0.03 | −0.02 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.08 | −0.06 | −0.07 | 0.03 | −0.08 | −0.09 | −0.39** | 0.60** | 0.29** | – | |||

| 19. PSQI - Sleep Duration | 0.19** | −0.08 | −0.12* | −0.13* | −0.01 | 0.02 | 0.17** | −0.22** | 0.12* | −0.11* | 0.11* | 0.15** | −0.13* | −0.07 | 0.11* | −0.16** | 0.05 | −0.11 | – | ||

| 20. PSQI - Sleep Quality | −0.03 | 0.10 | −0.06 | 0.04 | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.20** | −0.24** | −0.25** | −0.16** | −0.04 | −0.02 | −0.02 | −0.01 | −0.1 | 0.03 | 0.01 | −0.00 | 0.34** | – | |

| 21. Actigraphy - Sleep Duration | −0.05 | −0.12 | 0.15* | −0.02 | 0.03 | 0.09 | −0.05 | 0.09 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.14* | −0.07 | −0.04 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.32** | 0.10 | – |

| 22. Actigraphy - WASO | −0.24** | 0.25** | 0.03 | −0.00 | 0.10 | 0.03 | 0.18** | −0.05 | −0.04 | −0.08 | 0.04 | 0.13* | 0.08 | 0.05 | −0.18** | 0.27** | −0.02 | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.15* | 0.30** |

P<0.05,

P<0.01

Females had higher levels of negative and anxious mood and higher levels of ERI exploration compared to males. For nativity, foreign-born participants had fathers with higher education levels, attended schools with higher diversity, and lived in neighborhoods with higher diversity. Positive mood was negatively correlated with negative mood and discrimination, but positively correlated with ERI exploration and commitment, subjective sleep duration and quality, and WASO. Negative mood was positively correlated with anxious mood and discrimination, and negatively correlated with subjective sleep duration and quality. Anxious mood was positively associated with discrimination, while it was negatively associated with subjective sleep quality. Discrimination was negatively associated with subjective sleep duration and quality.

ERI exploration was positively associated with ERI commitment, and ERI commitment was positively associated with mother’s education level, subjective sleep duration, and objective sleep duration and WASO. Mother’s education level was positively associated with father’s education level, but negatively associated with neighborhood diversity and subjective sleep duration. School diversity was correlated with lower levels of school poverty (higher SES), higher neighborhood diversity and lower levels of poverty (higher SES), and shorter WASO, but correlated with subjective sleep duration (higher subjective sleep duration). School poverty was positively associated with neighborhood diversity and poverty (lower school SES, higher neighborhood diversity, lower neighborhood SES), and shorter subjective sleep duration and longer WASO. Neighborhood diversity is positively correlated with neighborhood poverty (higher neighborhood diversity, lower SES). Subjective sleep duration is positively correlated with subjective sleep quality and objective sleep duration (higher subjective sleep quality, higher objective sleep duration), while subjective sleep quality was positively associated with WASO (higher subjective sleep quality, longer WASO). Lastly, objective sleep duration was positively associated with WASO (longer WASO).

3.2. Latent class analysis

Based on the fit indices (AIC, BIC, ABIC, entropy) and tests of model fit (VLMR-LRT, adjusted LMR, and BLRT) and the interpretability, a three-cluster solution was identified as the optimal number of subgroups to capture variations among the participants’ ethnicity/race, gender, nativity, mothers’ education, fathers’ education, school diversity level, school poverty rate (school SES), neighborhood diversity level and neighborhood poverty rate (neighborhood SES). According to Table 2, the decrease in the values of AIC, BIC, and ABIC starts to plateau at around 3-classes model. The entropy for this model was also acceptable. The model comparisons between 2-class model vs. 3-class model indicated that having 3-class significantly improved the fit compared to the 2-classes model (VLMR-LRT: P < 0.05; adjusted LMR: P<0.05; BLRT: P<0.001). Compared to having 3 classes, having 4 classes did not significantly improve the model fit for two out of three tests (VLMR-LRT: P=n.s.; adjusted LRM: P=n.s.; BLRT: P<0.001). Based on multiple indicators and tests with the consideration of interpretability, we decided to select the 3-class model (Table 3).

Table 2.

Fit indices for 1–4 latent class models.

| AIC | BIC | ABIC | Entropy | VLMR-LRT | LMR-ALT | BLRT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 class | 4931.165 | 4992.892 | 4942.134 | ||||

| 2 classes | 4375.144 | 4502.456 | 4397.769 | 1 | P<0.001 | P<0.001 | P<0.001 |

| 3 classes | 4244.325 | 4437.222 | 4278.604 | 0.989 | P<0.05 | P<0.05 | P<0.001 |

| 4 classes | 4193.771 | 4452.252 | 4239.704 | 0.978 | n.s. | n.s. | P<0.001 |

Table 3.

Latent class membership for the three-class model.

| C1 (n = 131) % | C2 (n = 32) % | C3 (n = 187) % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race | Asian | 3.6 | 16.1 | 72.2 |

| Black | 50.7 | 0 | 5.3 | |

| Latinx | 45.7 | 83.9 | 22.5 | |

| Gender | Female | 69.8 | 73.4 | 67.9 |

| Nativity | US-born | 73.9 | 78.6 | 80.8 |

| Mother’s Education | Low | 47.8 | 73.4 | 49.6 |

| Mod | 43.6 | 26.6 | 37.2 | |

| High | 8.6 | 0 | 13.1 | |

| Father’s Education | Low | 63.8 | 80.3 | 54.2 |

| Mod | 26.7 | 15.7 | 31.4 | |

| High | 9.4 | 3.9 | 14.4 | |

| School Diversity Index | Low | 58.4 | 0 | 0 |

| Mod | 0 | 91.6 | 0 | |

| High | 41.6 | 8.4 | 100 | |

| % Families in School below poverty level | Low (High SES) | 0 | 0 | 100 |

| Mod (Mod SES) | 16.3 | 100 | 0 | |

| High (Low SES) | 83.7 | 0 | 0 | |

| Neighborhood Diversity Index | Low | 31.6 | 5.1 | 23.2 |

| Mod | 34.2 | 52.2 | 62.7 | |

| High | 34.2 | 42.8 | 14.1 | |

| % Neighborhood below poverty level | Low (High SES) | 4.6 | 16.4 | 39.9 |

| Mod (Mod SES) | 34.9 | 69.4 | 58.4 | |

| High (Low SES) | 60.5 | 14.2 | 1.7 |

The first latent class (i.e., C1) was the second largest and included 131 adolescents who were mostly Black (50.7%) or Latinx (45.7%) with very few Asian (3.6%) adolescents (Table 3). In C1, 25.2% was from School A, 16.8% was from School B, 58.0% was from School C. Reflecting the general characteristic of the sample, this subgroup was mostly female (69.8% were female) and born in the United States (73.9%). At the family level, 47.8% of adolescents’ mothers completed high school or less, 63.8% of fathers completed high school or less. At the school level, adolescents in this class attend schools that had either low (58.4%) or high (41.6%) levels of school diversity. However, these same schools had relatively high percentages of students living under federal poverty level (83.7%). At the neighborhood level, this class was exposed to a range of ethnic/racial diversity (low: 31.6%, middle: 34.2%; high: 34.2%); however, the majority of this group lived in neighborhoods with relatively high percentages of individuals living under federal poverty level (60.5%). Based on these characteristics, this group could be summarized as, “Black/Latinx adolescents in low/moderate SES families in contexts of varying diversity and low SES (C1; Table 4).”

Table 4.

Summary of latent class characteristics.

| C1 “Black/Latinx adolescents in low/mod SES families in varying diversity and low SES schools and neighborhoods” | C2 “Predominantly Latinx adolescents in low SES families in moderate diversity and SES schools and neighborhoods” | C3 “Predominantly Asian adolescents in low/mod SES families in mod/high diversity and SES schools and neighborhoods” | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Race/ethnicity | Black/Latinx | Latinx/Asian | Asian/Latinx |

| Parent education | Low/Mod | Low | Low/Mod |

| School diversity | Low/High | Mod | High |

| School SES | Low | Mod | High |

| Neighborhood diversity | Low/Mod/High | Mod/High | Mod |

| Neighborhood SES | Low | Mod | Mod/High |

The second subgroup was the smallest with only 32 adolescents and was mostly Latinx (83.9%) and Asian (16.1%) adolescents with no Black adolescents (Table 3). In C2, 6.3% was from School B, 93.8% was from School D. This group was mostly female (73.4%) and born in the United States (78.6%). At the family level, the majority of mothers had education of high school or less (73.4%) and the majority of fathers also had education of high school or less (80.3%). At the school level, most adolescents attended schools with moderate levels of ethnic/racial diversity (91.6%) and high rates of poverty (100%). At the neighborhood level, adolescents lived in neighborhoods characterized by middle (52.2%) to high (42.8%) levels of ethnic/racial diversity and moderate levels of poverty (69.4%). Based on these characteristics, this group could be summarized as, “Predominantly Latinx adolescents in low SES families in moderate diversity and SES (C2; Table 4).”

The third subgroup was the largest with 187 adolescents and was mostly Asian (72.2%) with some Latinx (22.5%) and very few Black (5.3%) adolescents (Table 3). In C3, 100% was from School E. This subgroup was mostly female (67.9%) and United States born (80.8%). At the family level, 49.6% of mothers completed high school or less, and 54.2% of fathers completed high school or less. At the school level, all adolescents attended high diversity schools (100%) with low percentage of students living under federal poverty level (100%). At the neighborhood level, most adolescents lived in mid-level diversity neighborhoods (62.7%) with low (39.9%) to moderate (58.4%) percentages of individuals living under poverty line. Based on these characteristics, this group could be summarized as, “Predominantly Asian adolescents in low/moderate SES families in moderate/high diversity and SES (C3; Table 4).”

3.3. Multiple hierarchical regression

With the three identified LCA latent classes, multiple hierarchical regression analyses were conducted with discrimination and ERI also included in the equations to predict subjective sleep quality and quantity as well as objective sleep duration and wake minutes after sleep onset, respectively. Hierarchical regressions were conducted in three steps. In the first step, main effects of class membership were examined. Next, the main effects of discrimination and ERI exploration and commitment were included. The third step included two-way interaction terms for class membership and discrimination, ERI exploration and commitment, respectively.

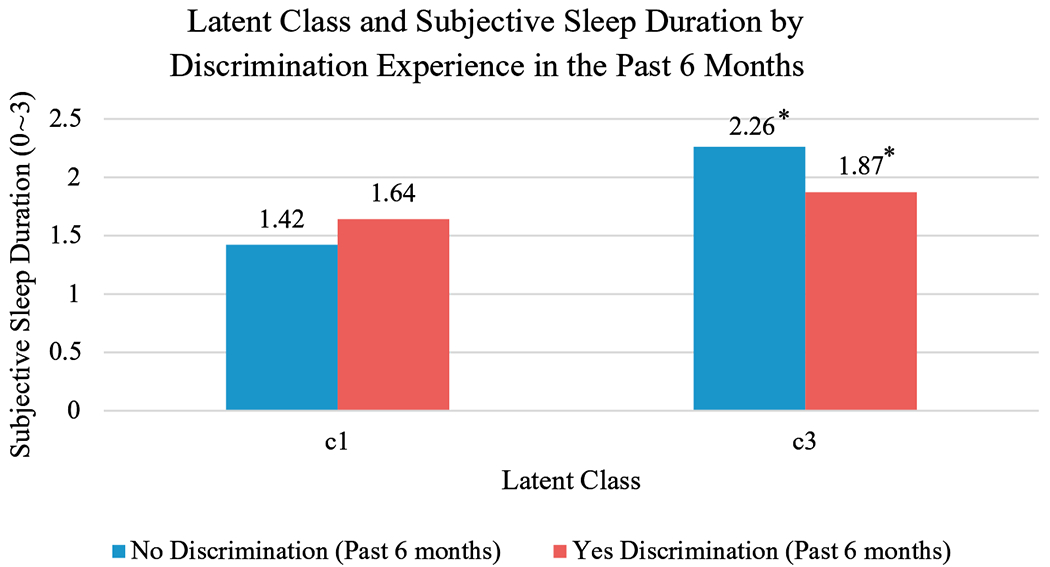

In the first model exploring subjective sleep duration as an outcome, compared to C3, groups C1 (B = −0.38, SE = 0.10, P<0.001) and C2 (B = −0.45, SE = 0.16, P<0.01) had shorter amounts (Table 5). In Model 2, discrimination was not directly associated with sleep. However, in Model 3 when two-way interactions between LCA class membership and discrimination as well as LCA class membership and ERI were included, a significant interaction between class membership and discrimination was found (B = 0.61, SE = 0.22, P<0.001). This interaction is modeled in Fig. 1 and the results suggest that for C3, subjective sleep duration was shorter for adolescents who experienced discrimination in the past 6 months (simple slopes test: P<0.05). However, for C1, subjective sleep duration was not significantly different for those who experienced discrimination in the past 6 months (simple slopes test: P = n.s.). Regardless of the discrimination experience, subjective sleep duration remained lower for C1 compared to C3. Among the covariates, age was negatively associated with subjective sleep duration, while positive mood was positively associated with subjective sleep duration.

Table 5.

Hierarchical multiple regression of class membership, discrimination, ERI, and subjective sleep duration and quality.

| Subjective sleep duration | Subjective sleep quality | Objective sleep duration | Objective sleep quality (WASO) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

| Intercept | 4.43 (1.07)*** | 4.38 (1.11)*** | 4.65 (1.07)*** | 1.29 (0.83) | 1.78 (0.87)* | 1.57 (0.84) | 505.68 (78.64)*** | 458.46 (82.49)*** | 529.34 (79.81)*** | 15.15 (24.78) | −1.42 (26.28) | 9.26 (25.95) |

| Age | −0.18 (0.07)* | −0.20 (0.07)** | −0.18 (0.07)* | 0.04 (0.06) | 0.03 (0.06) | 0.02 (0.06) | −2.79 (5.46) | −1.54 (5.56) | −2.75 (5.54) | 0.00 (1.72) | 0.74 (1.77) | 0.74 (1.80) |

| Positive mood | 0.13 (0.05)* | 0.13 (0.05)* | 0.14 (0.05)* | 0.10 (0.04)* | 0.12 (0.04)* | 0.14 (0.04)** | −1.48 (3.67) | −4.70 (3.90) | −4.76 (3.95) | 3.23 (1.72)** | 2.47 (1.24)* | 2.45 (1.28) |

| Negative mood | −0.12 (0.07) | −0.11 (0.07) | −0.11 (0.07) | −0.06 (0.05) | −0.03 (0.05) | −0.02 (0.05) | 7.40 (4.78) | 5.26 (4.80) | 5.49 (4.79) | −0.66 (1.51) | −0.87 (1.53) | −0.94 (1.56) |

| Anxious mood | −0.05 (0.07) | −0.03 (0.07) | −0.02 (0.07) | −0.13 (0.05)* | −0.13 (0.05)* | −0.13 (0.05)* | −4.66 (5.17) | −3.19 (5.19) | −4.70 (5.20) | 0.72 (1.63) | 0.83 (1.65) | 0.67 (1.69) |

| C1 | −0.38 (0.10)*** | −0.40 (0.10)*** | −0.84 (0.18)*** | 0.01 (0.08) | −0.04 (0.08) | −0.01 (0.14) | −0.75 (7.06) | −0.36 (7.09) | −18.23 (13.58) | 11.22 (2.22)*** | 10.86 (2.26)*** | 8.28 (4.42) |

| C2 | −0.45 (0.16)** | −0.45 (0.16)** | −0.38 (0.29) | −0.24 (0.13)+ | −0.26 (0.13)* | −0.39 (0.23) | −6.44 (11.71) | −5.42 (11.58) | −61.63 (22.74)** | 3.98 (3.69) | 4.01 (3.69) | −2.08 (7.39) |

| EDS | −0.15 (0.10) | −0.39 (0.15)** | −0.13 (0.08) | −0.13 (0.11) | −1.25 (7.72) | −18.67 (10.83) | −0.91 (2.46) | −3.20 (3.52) | ||||

| MEIM EXP | 0.03 (0.11) | 0.11 (0.14) | −0.05 (0.08) | 0.02 (0.11) | 10.85 (7.77) | −21.91 (10.80)* | −3.17 (2.47) | −4.82 (3.51) | ||||

| MEIM COM | 0.12 (0.12) | 0.06 (0.16) | −0.03 (0.09) | 0.04 (0.12) | 21.77 (8.29)** | 38.10 (12.02)** | 5.53 (2.64)* | 5.54 (3.91) | ||||

| EDS X C1 | 0.61 (0.22)** | −0.04 (0.17) | 23.91 (15.83) | 3.47 (5.15) | ||||||||

| EDS X C2 | −0.10 (0.35) | 0.12 (0.27) | 74.51 (26.40)** | 8.53 (8.58) | ||||||||

| MEIM EXP X C1 | 0.28 (0.23) | −0.04 (0.18) | 22.42 (16.46) | 3.69 (5.35) | ||||||||

| MEIM EXP X C2 | 0.12 (0.36) | −0.58 (0.28) | 25.89 (24.56) | 3.01 (7.99) | ||||||||

| MEIM COM X C1 | 0.26 (0.24) | −0.12 (0.19) | −29.69 (17.40) | −1.18 (5.66) | ||||||||

| MEIM COM X C2 | 0.06 (0.39) | −0.29 (0.30) | −42.78 (26.34) | 1.91 (8.57) | ||||||||

| R2 | 0.12 | 0.16 | 0.18 | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.15 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.15 |

Notes. C1 = Class1, C2 = Class2 (reference: Class3), EDS = Everyday Discrimination Scale (Discrimination), MEIM EXP = ERI Exploration, MEIM COM = ERI Commitment.

P < 0.05,

P < 0.01,

P < 0.001,

P < 0.07.

Fig. 1.

Latent class and subjective sleep duration by discrimination experience in the past 6 months.

For subjective sleep quality, Model 1 shows that compared to C3, group C2 reported marginally lower levels of sleep quality (Table 5; B = −0.24, SE = 0.13, P<0.07). In Model 2, with consideration of discrimination and ERI, C2’s subjective sleep quality was significantly lower than C3 (B = −0.26, SE = 0.13, P<0.05). No direct associations were found for discrimination or ERI. When two-way interactions were included in Model 3, no interaction effects were found. Among the covariates, positive mood was associated with higher subjective sleep quality, while anxious mood was associated with lower subjective sleep quality.

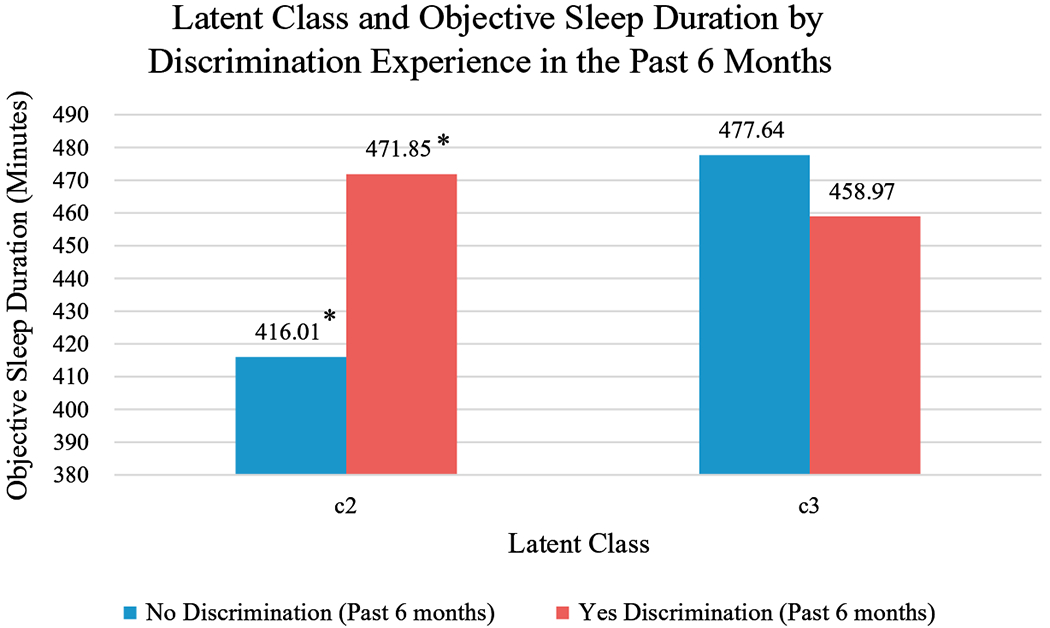

For objective sleep duration, Model 1 shows no associations with any of the predictors or covariates. In Model 2, ERI commitment was positively associated with objective sleep duration (Table 5; B = 21.77, SE = 8.29, P<0.01). With one unit increase in ERI commitment, adolescents reported 22 min longer objective sleep duration. When two-way interactions were considered in Model 3, an interaction effect between C2 and discrimination was found (Table 5; B = 74.51, SE = 26.40, P < 0.01; Fig. 2). For adolescents in C2 who experienced discrimination in the past 6 months displayed significantly longer objective sleep duration compared to those who did not experience discrimination (simple slopes test: P<0.05). For C3, the objective sleep duration seemed to be slightly lower for those who experienced discrimination compared to those who did not, but the difference was not significant (simple slopes test: P = n.s.).

Fig. 2.

Latent class and objective sleep duration by discrimination experience in the past 6 months.

Finally, objective sleep quality was examined with wake minutes after sleep onset (WASO) (Table 5). In Model 1, adolescents in C1 suffered more WASO than adolescents in C3 (B = 11.22, SE = 2.22, P< 0.001), indicating poorer sleep quality. When discrimination and ERI were included in Model 2, ERI commitment was positively associated with WASO (Table 5; B = 5.53, SE = 2.64, P < 0.05). In Model 3, two-way interaction terms were included and no significant interaction effects were found. Among covariates, positive mood continued to be positively associated with WASO, indicating that those who reported high levels of positive mood also reported longer wake minutes after sleep onset.

4. Discussion

The goals of the current study were first to explore the subgroups of ethnic/racial minority adolescents at the intersection of ethnicity/race and SES across various developmental contexts of family, school, and neighborhood; and second, to examine its implications for sleep and the roles of discrimination and ERI exploration and commitment. Drawing on theoretical foundations from the intersectionality framework (Crenshaw, 1989) and ecological systems theory (Bronfenbrenner, 1992), latent classes among adolescents according to individual ethnicity/race and school-, and neighborhood-level diversity and family-, school-, and neighborhood-level SES were derived. In total, three distinct classes of ethnicity/race, family, school and neighborhood characteristics were observed. Then, we found differences in subjective and objective sleep duration and quality across the identified latent groups, also discovering potentially important roles of discrimination and ERI. In this section, we review each finding in detail with interpretations and implications for future research, policies and programs. We also discuss limitations and contributions of the current study.

At the intersection of ethnicity/race and SES, we identified three latent classes in the current analytic sample. These groups were distinguished by differences in adolescents’ individual ethnicity/race, family SES, and their school and neighborhood diversity and SES levels. The three groups were labeled, “Black/Latinx adolescents in low/moderate SES families in varying diversity and low SES schools and neighborhoods (C1),” “Predominantly Latinx adolescents in low SES families in moderate diversity and SES schools and neighborhoods (C2),” and “Predominantly Asian adolescents in low/moderate families in moderate/high diversity and SES schools and neighborhoods (C3),” respectively (Table 4).

The Black/Latinx adolescents in C1 seemed to be at the intersection of multiple disadvantages and experiencing lack of resources across multiple contexts both in schools and neighborhoods. They were found across varying levels of diversity in schools and neighborhoods with a large percentage of them in low diversity schools and neighborhoods, which may be an indication of their attendance and residence in segregated schools and neighborhoods. Those in C2, which included mostly Latinx and some Asian adolescents, were not necessarily growing up in disadvantaged schools and neighborhoods, despite their ethnic/racial minority status and the fact that the largest percentage of the parents in this group had low levels of education. In fact, compared to their family SES, the schools and neighborhoods seemed to be relatively better, implying that this group may be subject to developing a sense of relative poverty (Foster, 1998). Overall, the school and neighborhood environment tended to be most favorable for the adolescents in C3 across multiple domains.

A person-centered analysis revealed the complex ways in which racial/ethnic and socioeconomic stratification at individual-, family-, school-, and neighborhood-levels are intertwined in U.S. communities (Ogbu, 1994). The latent classes had a mix of different ethnic/racial groups, demonstrating heterogeneity in their family, school, and neighborhood environment even within the same ethnic/racial groups and some overlaps between ethnic/racial groups. Particularly, the percentage of Latinx adolescents, which was dispersed across all three classes was noteworthy given that most of the Black adolescents were in C1 and most of the Asian adolescents were in C3. This also implies that while there is heterogeneity within ethnic/racial groups for Asian and Black adolescents, there may also be characteristics that set these two groups apart from one another in terms of their school and neighborhood environments. Simultaneously, Latinx adolescents may share significant commonalities with both Asian and Black adolescents at the intersection of ethnicity/race and SES at family-, school-, and neighborhood-levels. The observed heterogeneity, especially among the Latinx group, is consistent with and adds to the findings on the heterogeneity of Latinx adult population by Landale et al. (2017). However, there is still very little knowledge established around the heterogeneous combinations of ethnicity/race and SES within each ethnic/racial group including the Black and Asian groups (Nazroo, 2003). Since this study’s Asian adolescents were mostly recruited from one school and all of these adolescents’ characteristics were specific to one city that they all reside in, the results of this study reiterate the importance of conducting additional studies to replicate the findings to ensure they are generalizable. These classes also demonstrate that programs and policies that target a specific ethnicity/race or SES alone in a single context may overlook unique and qualitatively different experiences and meaning generated by different combinations of these characteristics. These results highlight that the intersectionality framework will add new dimensions to existing findings and advance the targeting of those who may be at different levels of need at different intersections of multiple identities.

These complex systems of stratification were borne out when looking at disparities in sleep. Compared to C3, shorter subjective sleep duration and worse objective sleep quality (longer WASO) were observed in “Black/Latinx adolescents in low/moderate SES families in varying diversity and low SES schools and neighborhoods (C1).” Moreover, when the interaction with discrimination experience was examined, this group demonstrated continuously low levels of subjective sleep regardless of the level of discrimination experience over the past 6 months, whereas those who experienced discrimination in “Predominantly Asian adolescents in low/moderate family SES in moderate/high diversity and SES schools and neighborhoods (C3)” demonstrated a significantly low levels of subjective sleep duration compared to those who did not experience discrimination in the past 6 months. The difference in the level of subjective sleep duration among adolescents in C3 by discrimination experience is consistent with the finding from a previous study that demonstrated a significant association between discrimination and sleep even after controlling for perceived stress (Huynh & Gillen-O’Neel, 2016). Moreover, this finding partly confirms the biopsychosocial model (Clark et al., 1999) in that the experience of discrimination was shown to threaten adolescents’ subjective health and well-being in the form of sleep. Whereas existing studies have mostly demonstrated the application of this model for adults, our study extends the application to the younger population.

At the same time, it is important to note that the subjective sleep duration of those who did experience discrimination in C3 was still higher than those who reported no experience of discrimination in the past 6 months in C1. For C1, it is possible that there were relatively stable contextual feelings of oppression or disturbance that compromised their sleep health beyond the reports of everyday discrimination experiences coming from their marginalized statuses in multiple areas of life. Due to consistently disadvantaged statuses across multiple developmental contexts that have induced stress, the adolescents in this group may have become desensitized to the experience of discomfort. What our measure referred to as “everyday discrimination” incidents in the past 6 months may in fact have been their default everyday experiences that do not necessarily generate much variation in their perception of how much sleep they are getting. However, the marginalized statuses across multiple domains still compromised overall sleep regardless of the discrimination reports as demonstrated by both shorter overall subjective sleep duration and objective sleep quality (longer WASO) of this group compared to C3. Their feelings of sleep duration were consistently lower and continuous sleep was consistently more disturbed than the reference group. In other words, the experience of stress such as discrimination may have been engraved in their common daily experiences and therefore, they may not have responded as sensitively to specific incidents of discrimination as other adolescents at different intersections of ethnicity/race and SES.

Additionally, previous studies find that perceived home atmosphere, a health-promoting lifestyle and good self-perception have been identified as important contributors to 15-year-old boys’ and girls’ subjective sleep duration (Tynjälä, Kannas, Levälahti, & Välimaa, 1999). While disruption in subjective sleep due to adverse conditions such as being noisy, unclean, crime-prone, unsafe in segregated and low SES environments was implied in these studies (Hale, Hill, & Burdette, 2010), our results suggest that these conditions may have an impact on continuous sleep in actual minutes beyond subjective experiences. It is possible that Black/Latinx adolescents in C1 who were in varying diversity and SES schools and neighborhoods were not able to practice coping strategy to discrimination through sleep and their WASO could not be reduced, possibly due to the strong impact of adverse conditions in the segregated and low SES environment that may have constantly disrupted continuous sleep (Hale et al., 2010). Even though both groups included ethnic/racial minorities, being in multiple disadvantaged contexts (i.e., in schools and neighborhoods marked by varying diversity, which included the highest percentage of varying diversity among the three classes, implying segregation, and high percentage of families and individuals living below poverty level) may have involved issues such as with noise and safety creating differences in the way adolescents respond to discrimination in the form of sleep duration and quality. Although adolescents in C3 and some adolescents in C1 were both in highly diverse schools and neighborhoods, those in C1 still suffered from high WASO (low sleep quality) regardless of the effect of discrimination. This is somewhat consistent with Branton and Jones’ (2005) finding that high SES contexts and high diversity contexts are both related to high levels of support for racial social issues, whereas low SES contexts and high diversity are related to low levels of support for those issues. Moreover, as objective sleep quality measures including WASO have been found to be closely related to one’s health and academic performance (Dewald, Meijer, Oort, Kerkhof, & Bögels, 2010; Hysing, Harvey, Linton, Askeland, & Sivertsen, 2016; Palermo & Kiska, 2005; Sivertsen, Harvey, Lundervold, & Hysing, 2014), our finding provides implications for the role of sleep in health and academic disparities especially for the individuals at the intersections of disadvantage across multiple contexts.

Next, shorter subjective sleep duration and worse subjective sleep quality were observed in “Predominantly Latinx adolescents in low SES families in moderate diversity and SES schools and neighborhoods (C2).” In other words, being in varying levels of diversity and low SES across schools and neighborhoods was strongly related to feelings of disruption in long and quality sleep. Moreover, some of the adolescents in this group may have experienced contrasting levels of diversity and SES across their developmental contexts. While most of their parents had low levels of education, their school and neighborhood SES were not necessarily low. These inconsistent statuses across different domains may have elicited feelings of relatively poverty (Foster, 1998) and cognitive dissonance (Festinger, 1957), or incongruence in one’s thoughts and beliefs, which requires increased amounts of mental energy to find the state of congruence in one’s identity. This process may have, in turn, contributed to low levels of subjective sleep duration and quality.

Interestingly, class membership to this group (C2) demonstrated an interaction effect with the experience of discrimination in objective sleep duration. Among the adolescents in C2, those who experienced discrimination in the past 6 months reported sleeping more than those who reported no experience of discrimination. The reference group, C3, the sleep minutes were slightly lower for those who experienced discrimination but the difference was not significant. In other words, adolescents in C2 who were likely to experience contrasting statuses across developmental contexts may have ascribed qualitatively different meaning to the experience of discrimination. They may have been more sensitive or vigilant to discrimination experiences than adolescents identified as C3, those who were likely to have experienced similarly moderate to high statuses across developmental contexts (Majeno et al., 2018). As this group (C2) generally experienced feelings of shorter sleep duration and worse sleep quality compared to C3, they may have actually needed or chosen to sleep for longer in the face of discrimination as a possible coping strategy to make up for the feelings of sleep deprivation and disturbance. Further, the contrasting statuses in their developmental environment may have stimulated these adolescents to be more perceptive and adjusting to the environmental changes. As previous studies also suggest potential differences in responses to stress in the form of sleep as coping strategies (Sadeh, Keinan, & Daon, 2004), it will be helpful to continue this line of research by examining the role of sleep as a coping strategy.

At the same time, ERI commitment was significantly related to longer objective sleep duration and longer WASO. In support of our hypothesis, adolescents with stronger commitment tended to sleep about 22 min more and be awake for about 5 min longer during their sleep duration than those with 1 unit lower level of commitment. ERI commitment could have contributed to a sense of stability at a deeper level that is described beyond positive, negative or anxious mood (Romero et al., 2014; Stein et al., 2014; Yip et al., 2019), and as a result of longer sleep duration there may have also been a slight increase in their WASO. However, ERI has also been found to be closely associated with heightened alertness to discrimination experience (Branscombe, Schmitt, & Harvey, 1999; Hughes, Watford, & Del Toro, 2016; Umaña-Taylor & Updegraff, 2007), and the literature regarding the role of ERI in sleep has not been solidly established (Yip, 2018), the strong impact of ERI commitment above the impact of mood, latent classes and discrimination in objective sleep duration highlights the need to further investigate the mechanism ERI plays in sleep.

Lastly, it is worth noting the significant associations with study covariates, which were various mood states. Positive mood was significantly associated with longer subjective sleep duration, better sleep quality, but longer WASO. This finding suggests that having a positive mood may help adolescents feel better about their sleep health in terms of duration and quality. However, it also suggests that positive mood may elicit heightened alertness thus resulting in longer WASO. Whether this should be of concern or not needs to be addressed further in future studies as sleep health involves various dimensions and measures. Simultaneously, negative mood was not associated with any of the sleep characteristics measured in this study, while anxious mood was associated with lower levels of subjective sleep quality. Our findings call for further studies to address potential contributions of various moods implied in previous studies (Fuligni & Hardway, 2006; Thomsen et al., 2003) considering various dimensions of sleep health.

The findings of this study need to be considered with limitations in mind. Although LCA enabled us to identify different groups of ethnic/racial minority adolescents at the intersection of ethnicity/race characterized by different person-environment combinations, we were not able to tease apart the qualitative meaning and experiences associated with these intersections. Further studies are needed to understand adolescents’ meaning-making processes and experiences at different intersections of ethnicity/race and SES. Also, only mothers’ and fathers’ education levels were used as a proxy for adolescents’ family SES since information about household income was not available. The inclusion of income information along with occupational information or employment status will provide a multidimensional perspective in capturing adolescents’ family SES more accurately. Moreover, a larger and more representative sample of the population will provide more generalizable implications and identify even more diverse patterns in the intersectionality of ethnicity/race and SES among ethnic/racial minority adolescents. Whereas our study only included students from five schools in one metropolitan city, greater variability in school and neighborhood diversity and SES will open doors for identifying more detailed and diverse subgroups. Future studies could also extend the findings by examining the changes in the intersectionality of ethnicity/race and SES over time, or the developmental trajectories taken by these adolescent groups in the long-term. Taking these subgroups to investigate within-person daily experiences and individual differences will also shed light on the unexamined areas of research in this field. Specifically, subsequent studies could examine how these subgroupings may create variations in the way children and adolescents respond to daily encounters of discrimination in the form of sleep. Furthermore, we have only examined duration and quality of sleep. Studies that also examine other aspects of subjective and objective sleep such as variability and onset latency will also contribute to the holistic understanding of sleep disparities among ethnic/racial minority and low SES groups.

Despite these limitations, this study extends and moves the existing literature beyond unidimensional perspective of ethnic/race and SES by adopting the intersectionality framework. Also, by examining both subjective and objective measures of sleep, we have recognized the multidimensional nature and complexity of sleep measures and how different individual and environmental factors may influence various aspects of sleep to create disparities in dynamic ways. We suggest future studies take these perspectives and replicate these findings for more generalizable and diverse populations across the nation. The intersectionality perspective will provide specific and rich information to enable the identification of individuals at varying levels of need in different dimensions of life for designing and implementing effective policies and interventions.

References

- Akaike H. (1987). Factor analysis and AIC. Psychometrika, 52(3), 317–332. [Google Scholar]

- Arellano-Morales L, Roesch SC, Gallo LC, Emory KT, Molina KM, Gonzalez P, et al. (2015). Prevalence and correlates of perceived ethnic discrimination in the Hispanic community health study/study of Latinos sociocultural ancillary study. Journal of Latina/o Psychology, 3(3), 160–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assari S. (2017). Combined racial and gender differences in the long-term predictive role of education on depressive symptoms and chronic medical conditions. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 4(3), 385–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker FC, Maloney S, & Driver HS (1999). A comparison of subjective estimates of sleep with objective polysomnographic data in healthy men and women. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 47(4), 335–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastien CH, Fortier-Brochu É, Rioux I, LeBlanc M, Daley M, & Morin CM (2003). Cognitive performance and sleep quality in the elderly suffering from chronic insomnia: Relationship between objective and subjective measures. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 54(1), 39–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baum KT, Desai A, Field J, Miller LE, Rausch J, & Beebe DW (2014). Sleep restriction worsens mood and emotion regulation in adolescents. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 55(2), 180–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beebe DW, Rose D, & Amin R (2010). Attention, learning, and arousal of experimentally sleep-restricted adolescents in a simulated classroom. Journal of Adolescent Health, 47(5), 523–525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergman LR, & Magnusson D (1997). A person-oriented approach in research on developmental psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology, 9(2), 291–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowleg L. (2012). The problem with the phrase women and minorities: Intersectionality—An important theoretical framework for public health. American Journal of Public Health, 102(7), 1267–1273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand S, Gerber M, Hatzinger M, Beck J, & Holsboer-Trachsler E (2009). Evidence for similarities between adolescents and parents in sleep patterns. Sleep Medicine, 10(10), 1124–1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branscombe NR, Schmitt MT, & Harvey RD (1999). Perceiving pervasive discrimination among African Americans: Implications for group identification and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77(1), 135–149. [Google Scholar]

- Branton RP, & Jones BS (2005). Reexamining racial attitudes: The conditional relationship between diversity and socioeconomic environment. American Journal of Political Science, 49(2), 359–372. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. (1979). The ecology of human development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. (1992). Ecological systems theory. In Vasta R(Ed.), Six theories of child development: Revised formulations and current issues (pp. 187–249). London: Jessica Kingsley. [Google Scholar]

- Buckhalt JA, El-Sheikh M, & Keller P (2007). Children’s sleep and cognitive functioning: Race and socioeconomic status as moderators of effects. Child Development, 78(1), 213–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF III, Monk TH, Berman SR, & Kupfer DJ (1989). The Pittsburgh sleep quality index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Research, 28(2), 193–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2017). Short sleep duration among US adults, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Division of Population Health. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/sleep/data_statistics.html. May 2.