Abstract

Background and Objectives

Spinocerebellar ataxia type 3 (SCA3) is a hereditary ataxia that occurs worldwide. Clinical patterns were observed, including the one characterized by marked spastic paraplegia. This study investigated the clinical features, disease progression, and multiparametric imaging aspects of patients with SCA3.

Methods

We retrospectively analyzed 249 patients with SCA3 recruited from the Organization for Southeast China for cerebellar ataxia research between October 2014 and December 2020. Of the 249 patients, 145 were selected and assigned to 2 groups based on neurologic examination: SCA3 patients with spastic paraplegia (SCA3-SP) and SCA3 patients with nonspastic paraplegia (SCA3-NSP). Participants underwent 3.0-T brain MRI examinations, and voxel-wise and volume-of-interest-based approaches were used for the resulting images. A tract-based spatial statistical approach was used to investigate the white matter (WM) alterations using diffusion tensor imaging, neurite orientation dispersion, and density imaging metrics. Multiple linear regression analyses were performed to compare the clinical and imaging parameters between the 2 groups. The longitudinal data were evaluated using a linear mixed-effects model.

Results

Forty-three patients with SCA3-SP (mean age, 37.58years ± 11.72 [SD]; 18 women) and 102 patients with SCA3-NSP (mean age, 47.42years ± 12.50 [SD]; 39 women) were analyzed. Patients with SCA3-SP were younger and had a lower onset age but a larger cytosine-adenine-guanine repeat number, as well as higher clinical severity scores (all corrected p < 0.05). The estimated progression rates of the Scale for the Assessment and Rating of Ataxia (SARA) and International Cooperative Ataxia Rating Scale scores were higher in the SCA3-SP subgroup than in the SCA3-NSP subgroup (SARA, 2.136 vs 1.218 points; ICARS, 5.576 vs 3.480 points; both p < 0.001). In addition, patients with SCA3-SP showed gray matter volume loss in the precentral gyrus with a decreased neurite density index in the WM of the corticospinal tract and cerebellar peduncles compared with patients with SCA3-NSP.

Discussion

SCA3-SP differs from SCA3-NSP in clinical features, multiparametric brain imaging findings, and longitudinal follow-up progression.

Introduction

Spinocerebellar ataxia 3 (SCA3), also known as Machado–Joseph disease, is the most prevalent form of spinocerebellar ataxia worldwide. It is caused by variations located within the ATXN3 gene,1 which lead to the abnormal expansion of polyQ tracts in the ATXN3 protein within neurons, primarily affecting specific nuclei in different regions of the CNS, including the cerebellum, brainstem, spinal cord, cerebral areas, and peripheral nerves.2,3 The onset of the disease typically occurs during adulthood, and the clinical signs are highly heterogeneous, such as progressive ataxia, pyramidal signs, parkinsonism, dystonia, eye movement abnormalities, painful axonal neuropathy, and cognitive and psychiatric disturbances.3-5

Several clinical patterns have been recognized.6-8 In 1996, a study described 2 siblings affected by SCA3 who reported a spastic paraplegia without evident cerebellar ataxia, leading to the proposal of a spastic paraplegic subtype, referred as type V later.8,9 Our previous investigation involved 3 index patients of SCA3 with spastic paraplegia at an average onset age of 18 years with more than 80 cytosine-adenine-guanine (CAG) repeats.10 In addition, an MRI meta-analysis including 160 patients with SCA3 has demonstrated that the volume loss is mainly located in the right corticospinal tract (CST),11 while another study performed on 91 patients with SCA3 has reported the CST damage by diffusion tensor imaging (DTI),12 suggesting that the spastic paraplegic pattern may have a specific genotype and phenotype. Nonetheless, little is known about their genetic, clinical, and multiparametric imaging features.

The phenotypic diversity of SCA3 poses challenges not only for clinical diagnosis and management but also for successful therapeutic interventions during clinical trials.13,14 In the context of SCA3 subtype IV, treatment with levodopa has shown a notable clinical improvement15,16 but not for the other clinical subtypes, thereby highlighting the importance of the selection of patients with genetic and phenotypic homogeneity for future therapeutic trials in specific clinical subtypes.

In this study, we conducted a comprehensive investigation to assess the differences in genotype, clinical features, multiparametric brain MRI assessments, and longitudinal follow-up observations of SCA3 patients with spastic paraplegia (SCA3-SP) and SCA3 patients with nonspastic paraplegia (SCA3-NSP), demonstrating that SCA3-SP represents a distinct clinical subtype.

Methods

Standard Protocol Approvals, Registrations, and Patient Consents

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee for Medical Research of Fujian Medical University Hospital ([2019]195; ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT04010214). All enrolled patients provided written informed consent to share their personal data.

Participants and Design

A cohort of patients affected by SCA3 were recruited from the Organization in Southeast China for Cerebellar Ataxia Research (OSCCAR) from patients admitted to the Department of Neurology of the Fujian Medical University between October 2014 and December 2020, and they were retrospectively evaluated. Of the cohort, 249 had genetically confirmed SCA3 patients with CAG repeat expansion in the alleles of ATXN3 gene in a range between 56 and 87.17 Moreover, healthy controls (HCs) comprising 44 sex- and age-matched patients with normal CAG repeat numbers within the ATXN3 gene in a range from 12 to 44 were also included.17

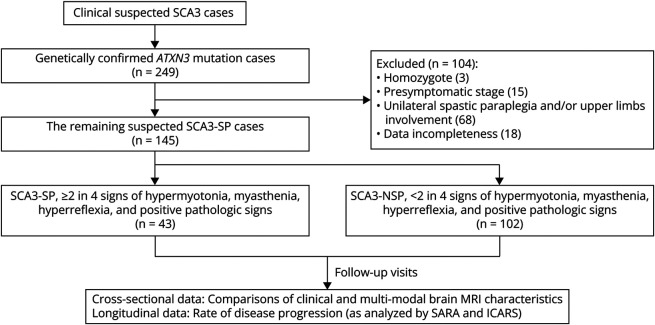

Owing to the clinical similarities between SCA3-SP and hereditary spastic paraplegia (HSP),10 the patients with SCA3-SP were assessed in conjunction with the core attributes of HSP,18 including symmetrical spasticity affecting both lower limbs, thereby excluding those showing asymmetry or spasticity of the upper limbs. Thus, we confirmed a diagnosis of spasticity when at least 2 of the 4 criteria were present: hypermyotonia, myasthenia, hyperreflexia, and positive pathologic signs.19 On the contrary, patients without spasticity at the level of the bilateral lower limbs were classified as SCA3-NSP (Figure 1). In both cases, patients exhibited cerebellar ataxia. In addition, 134 of the 249 patients were excluded for several reasons, including homozygosity (3), presymptomatic patients (15), unilateral spastic paraplegia and/or upper limb involvement (68), and incomplete data (18). In total, 145 patients were included in the final analysis.

Figure 1. Flowchart on the Recruitment and Inclusion of the Participants in This Study.

SCA3 = spinocerebellar ataxias type 3; SCA3-SP = SCA3 patients with spastic paraplegia; SCA3-NSP = SCA3 patients with nonspastic paraplegia.

Two composite cerebellar ataxia scales, the Scale for the Assessment and Rating of Ataxia (SARA) and the International Cooperative Ataxia Rating Scale (ICARS), were used during the same visit,20,21 considering the age of patients during the neurologic examination and/or MRI. In addition, the “AAO” was defined as the time in which gait instabilities were first noticed while the “disease duration” was the interval from AAO and the patient's age during the examination. Patients with SARA score <3 were defined as presymptomatic SCA3, while those with SARA score ≥3 were considered symptomatic SCA3.22 We collected signalment data about age at each examination and reported them in the flowchart of participants in Figure 1.

MRI Acquisition

The participants were examined using 3.0-T brain MRI (Siemens Skyra scanner). Sagittal anatomical images were acquired using a three-dimensional T1-weighted (T1W) magnetization-prepared rapid gradient-echo (MP-RAGE) sequence with the following scan parameters: TR = 2300 ms, TE = 2.3 ms, TI = 900 ms, flip angle = 8°, field of view = 240 × 256 mm, number of slices = 192, voxel size = 1 × 1 × 1 mm3, and total acquisition time = 5.2 minutes. By contrast, the diffusion data were obtained using a simultaneous multislice echo-planar imaging (EPI) sequence using the following parameters: TR = 11700 ms, TE = 96 ms, field of view = 232 mm × 232 mm, matrix size = 116 × 116, voxel size = 2 × 2 × 2 mm, number of slices = 80, NEX = 1, 3 b = 0 images, 2 b shells = 1,000 and 2000 s/mm2 with a diffusion encoding direction of 30 for each shell, and a total acquisition time of 12 minutes and 54 seconds. A total of 53 patients with SCA3 and 44 HCs underwent MRI. Experienced radiologists evaluated the collected data for quality control.

Postprocessing of the Volumetric T1W Image

Automatic and quantitative segmentations of the 3D T1W images were conducted using the FreeSurfer software,23 and the volume of the cerebellum and subcortical and cortical structures were obtained and expressed as a percentage of the total intracranial volume (TIV).

T1-weighted images were further segmented into gray matter (GM), white matter (WM), and CSF using Statistical Parametric Mapping software (SPM)24 on the MATLAB R2017b platform and then normalized to the standard space by diffeomorphic anatomical registration using the Exponentiated Lie algebra. Finally, the GM images were normalized using Jacobian determinants and smoothed using an 8-mm full-width at half-maximum Gaussian filter used in the voxel-wise statistical analyses.

Postprocessing of the Diffusion MRI Data

Owing to the sensitivity of the diffusion of water molecules within tissue, DTI can provide quantitative information on the brain microstructure.25 Diffusion tensor images were first denoised and corrected for Gibb's ringing using MRtrix3 software, while the eddy current distortion and head motion corrections and the brain tissue extraction were performed using the FMRIB Software Library.26 We performed the diffusion fitting to obtain DTI metrics, including fractional anisotropy (FA), mean diffusivity (MD), axial diffusivity (AD), and radial diffusivity (RD), derived from the image data with b = 0 and 1,000 s/mm2, using the “dtifit” function in FSL.

The neurite orientation dispersion and density imaging (NODDI) is an advanced three-compartment biophysical diffusion model that is able to provide specific information of the brain microstructure, thereby overcoming the limitations of standard DTI.27 The neurite density index (NDI) refers to the density of axons and dendrites, while the orientation dispersion index (ODI) represents the fanning and bending of axons and the pattern of sprawling dendritic processes.27 Volume fraction of isotropic (Viso) diffusion is able to quantify the fractional volume occupied by extracellular fluid.27,28 Therefore, the NODDI model was fitted to calculate the NODDI-related metrics, including NDI, ODI, and Viso, using the NODDI toolbox29 based on Matlab (MathWorks, Natick, MA).

Tract-based spatial statistics (TBSS) analysis was performed based on the standardized TBSS framework to investigate the microstructural alterations of the WM. First, the FA images captured from all participants were aligned to an FMRIB58_FA standard-space template by nonlinear registrations, and then, the mean image was thinned to create a mean FA skeleton with a threshold value of 0.2. Finally, the aligned FA images were projected onto the mean FA skeleton and onto other non-FA maps (including MD, AD, RD, Viso, NDI, and ODI) using the same nonlinear registration.

Statistical Analysis

The normality of the standardized residuals was evaluated using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Continuous variables are presented as means (SD) and categorical data as numbers (%). Univariate analysis to compare the demographic, clinical, and brain MRI parameters of patients with SCA3-SP and SCA3-NSP was conducted using the Mann–Whitney U or χ2 test, and multiple linear regression models were used for comprehensive analysis of AAO, SARA, and ICARS scores.

In addition, the rate of disease progression (as assessed by SARA and ICARS) in patients with SCA3-SP and SCA3-NSP was analyzed using linear mixed-effects models.30,31 The correlations among repeated measurements of the same patient were calculated using participant-specific random effects despite missing data, unequal number of follow-up visits, and irregular intervals between visits. Disease duration was used as the time scale. The analysis was corrected for age and duration at baseline, sex, and number of expanded CAG repeats.

Voxel-based morphometry (VBM) analysis was used to identify differences in GM volume. Covariates of no interest, including sex, age, and the total intracranial volume of each participant, were included in the analysis. A one-way ANOVA was performed to investigate the GM differences among HCs, patients with SCA3-SP, and patients with SCA3-NSP using SPM12, followed by a specific test for the GM differences between patients with SCA3-SP and SCA3-NSP. When p values were <0.05, the results were considered statistically significant after false discovery rate (FDR) cluster-level correction.

A TBSS approach was used to investigate changes in diffusivity parameters along the WM tract using a general linear model by FSL, with age and sex as covariates. Differences among HCs and patients with SCA3-SP and SCA3-NSP were assessed using an FSL permutation test (FSL Randomize Tool, 5,000 permutations) and a Threshold-Free Cluster Enhancement option. The statistical map threshold was set at p < 0.05 using family-wise error (FWE) correction.

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS v25.0 (IBM, Armond, New) and Prism v7.0 (GraphPad, San Diego, CA). p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Bonferroni correction was applied to adjust the results for multiple comparisons.

Data Availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Results

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

A total of 145 patients with SCA3 were selected and further analyzed in this study, of whom 43 were classified as having SCA3-SP and 102 were categorized as having SCA3-NSP. Patients with SCA3 and HCs were matched for age and sex (p > 0.05), and the main demographic and clinical characteristics are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical Characteristics of Patients With SCA3 and Healthy Controls

| Parameters | Mean (SD) or n (%) | p Valuea | |||

| Healthy controls | Whole SCA3 | SCA3-SP | SCA3-NSP | ||

| Total n | 44 | 145 | 43 | 102 | |

| Sex (female) | 21 (47.7) | 57 (39.3) | 18 (41.9) | 39 (38.2) | 0.683 |

| Age at examination, y | 41.86 (11.37) | 44.50 (13.04) | 37.58 (11.72) | 47.42 (12.50) | <0.001 |

| Age at onset, y | NA | 35.94 (11.78) | 28.62 (10.41) | 39.03 (10.96) | <0.001 |

| Disease duration, y | NA | 8.779 (5.057) | 8.98 (4.42) | 8.70 (5.32) | 0.455 |

| SARA scores, points | NA | 11.89 (7.064) | 14.49 (8.12) | 10.80 (6.29) | 0.005 |

| ICARS scores, points | NA | 30.54 (17.06) | 36.16 (19.50) | 28.18 (15.42) | 0.020 |

| Normal CAG repeats | NA | 19.41 (6.977) | 19.02 (7.05) | 19.57 (6.98) | 0.598 |

| Expanded CAG repeats | NA | 74.21 (4.059) | 76.12 (4.68) | 73.40 (3.48) | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: CAG = cytosine-adenine-guanine; ICARS = International Cooperative Ataxia Rating Scale; NA = not applicable; SARA = Scale for the Assessment and Rating of Ataxia; SCA3 = spinocerebellar ataxias type 3; SCA3-SP = SCA3 patients with spastic paraplegia; SCA3-NSP = SCA3 patients with nonspastic paraplegia.

Bold p value < 0.05.

Mann–Whitney U test or Pearson χ2 was used to compare variables between SCA3-SP and SCA3-NSP subgroups.

As per the univariate analysis, the SCA3-SP subgroup showed lower age (p < 0.001), earlier AAO (p < 0.001), larger number of CAG repeats (p < 0.001), and higher scores in SARA (p = 0.005) and ICARS (p = 0.020) than the SCA3-NSP subgroup (Table 1). To exclude any influence of covariates between the 2 subgroups, we conducted multivariate regression analysis that showed that patients with SCA3-SP had an earlier AAO than those with SCA3-NSP (p = 0.016). In addition, even after adjusting for sex, age, disease duration, and normal and expanded CAG repeats, the SCA3-SP subgroup showed higher SARA and ICARS scores than the SCA3-NSP subgroup (p = 0.001 and p = 0.002, respectively). Additional data are presented in eTable 1. Similarly, differences in AAO, CAG repeats, SARA, and ICARS scores were found when comparing the MRI subsets of the 19 patients with SCA3-SP and 34 patients with SCA3-NSP. Additional data are presented in eTable 2.

Disease Progression of the SCA3-SP and SCA3-NSP Subgroups

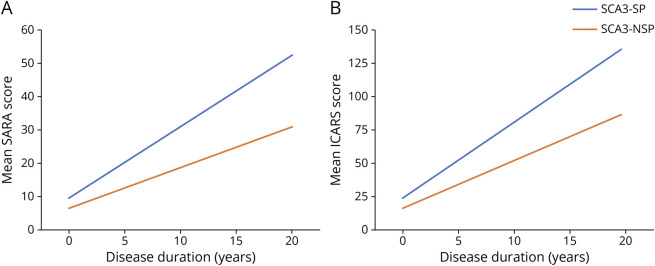

A total of 78 patients had follow-up visits (22 SCA3-SP and 56 SCA3-NSP), with a median of 2 visits per participant (range, 2–5 visits). A linear mixed-effects model was used to analyze the differences in SARA and ICARS scores at longitudinal progression between patients with SCA3-SP and SCA3-NSP. Disease duration was selected as the time scale and adjusted for age at baseline, sex, duration at baseline, and the number of expanded CAG repeats. The estimated SARA progression rate in the SCA3-SP subgroup was 2.136 per year (standard error [SE] = 0.2235; p < 0.001), whereas the SCA3-SP subgroup showed a much slower progression rate of 1.218 per year (SE = 0.1048; p < 0.001) (Figure 2A; eFigure 1). Furthermore, a statistically significant difference in the SARA score was found between the 2 subgroups (0.918; SE = 0.2192; p < 0.001) (Table 2). By contrast, the estimated ICARS progression rate in the SCA3-SP subgroup was 5.576 per year (SE = 0.5605; p < 0.001), and the SCA3-SP subgroup showed a slower progression rate of 3.480 per year (SE = 0.2642; p < 0.001) (Figure. 2B; eFigure 1), and as mentioned above, a difference in the ICARS score rates between the 2 subgroups was detected (2.096; SE = 0.5523; p < 0.001) (Table 2).

Figure 2. Longitudinal Trajectories of Mean Scale for the Assessment and Rating of Ataxia (SARA) and International Cooperative Ataxia Rating Scale (ICARS) Scores for SCA3 Patients With Spastic Paraplegia (SCA3-SP) and SCA3 Patients With Nonspastic Paraplegia (SCA3-NSP) Using a Linear Mixed-Effects Model.

(A–B) Longitudinal trajectories of mean SARA and ICARS scores showed lower progression for SCA3-SP than for SCA3-NSP. This observation included individuals sampled at different time points in the course of disease. Individuals were followed up for 0–5 visits. No individual was followed up for the full duration described on the x-axis. The graphs demonstrated the mean SARA and ICARS scores changes in the SCA3-SP and SCA3-NSP subgroups with covariates fixed at the following values: baseline age = 45 years, sex = male, baseline duration = 0 years, and the number of expanded CAG repeats = 75. Spaghetti plots demonstrating the change for individual participants are shown in eFigure 1.

Table 2.

Comparison of SARA and ICARS Scores Progression Between SCA3-SP and SCA3-NSP Subgroups by Longitudinal Follow-Up Data

| Characteristics | SARA score | ICARS score | ||||

| Coefficient | 95% CI | p Value | Coefficient | 95% CI | p Value | |

| Rate difference, ya | 0.918 | 0.4848 to 1.3508 | <0.001 | 2.096 | 1.0044 to 3.1866 | <0.001 |

| Baseline age, y | 0.150 | 0.0368 to 0.2628 | 0.010 | 0.374 | 0.1008 to 0.6473 | 0.008 |

| Sex (male) | 1.228 | −0.5592 to 3.0158 | 0.177 | 2.902 | −1.4154 to 7.2194 | 0.186 |

| Baseline duration, y | 0.519 | 0.2919 to 0.7454 | <0.001 | 1.296 | 0.7483 to 1.8432 | <0.001 |

| Expanded CAG repeats | 0.365 | 0.0519 to 0.6783 | 0.023 | 0.757 | 0.0006 to 1.5132 | 0.0498 |

| Duration at visit, y | 1.218 | 1.0108 to 1.4250 | <0.001 | 3.480 | 2.9585 to 4.0024 | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: CAG = cytosine-adenine-guanine; ICARS = International Cooperative Ataxia Rating Scale; SARA = Scale for the Assessment and Rating of Ataxia; SCA3 = spinocerebellar ataxias type 3; SCA3-SP = SCA3 patients with spastic paraplegia; SCA3-NSP = SCA3 patients with nonspastic paraplegia.

The difference in rate of change in SARA and ICARS scores in the respective models between SCA3-SP and SCA3-NSP, which is the predictor of concern in this model.

Volumetric MRI Features

Nineteen patients with SCA3-SP, 34 patients with SCA3-NSP, and 44 HCs underwent MRI. Volume-of-interest analyses adjusted for individual TIV showed a lower total cerebellar and brainstem volume in patients with SCA3-SP and SCA3-NSP than in HCs. In addition, a lower cerebellar volume was found in the SCA3-NSP group than in the SCA3-SP group (p < 0.05, eFigure 2), whereas no differences in volume between the SCA3-SP and SCA3-NSP subgroups were noted in the brainstem, subcortical, and cortical structures (p > 0.05). Additional data are presented in eTable 2.

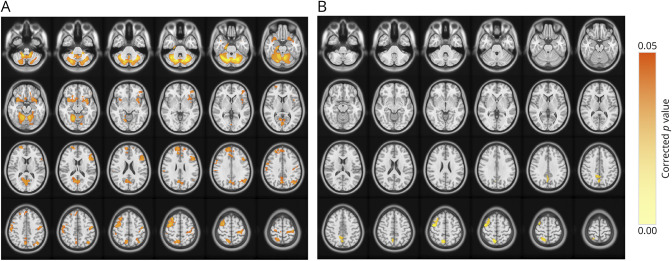

VBM analysis of the brain GM volume was performed to investigate the differences between the SCA3-SP subgroup, SCA3-NSP subgroup, and HCs. ANOVA showed several differences, mainly in the cerebellum, precentral gyrus, postcentral gyrus, precuneus, calcarine, parahippocampal gyrus, and basal ganglia (caudate and putamen) (p < 0.05, FDR-corrected at the cluster level; eFigure 3). Subsequent post hoc analysis showed reduced GM volumes in patients with SCA3-SP, mainly in the cerebellum, bilateral frontal lobes (precentral gyrus, middle frontal gyrus, and superior frontal gyrus), and parietal lobes (postcentral gyrus and precuneus) (p < 0.05, FDR-corrected at the cluster level; Figure 3A). When compared with the SCA3-NSP subgroup, the SCA3-SP subgroup had lower GM volumes within the right precentral gyrus, middle frontal gyrus, and precuneus (p < 0.05, FDR-corrected at the cluster level; Figure 3B).

Figure 3. Voxel-Based Morphometry Analyses of Brain GM Across Different Subgroups.

(A) Regions showcasing reductions in brain GM volume among the SCA3 patients with spastic paraplegia (SCA3-SP) compared with healthy controls. (B) Regions showcasing reductions in brain GM volume among the patients with SCA3-SP when compared with the patients with nonspastic paraplegia (SCA3-NSP). A post hoc test, p < 0.05, FDR-corrected.

TBSS Analysis of WM Microstructure in DTI and NODDI Metrics

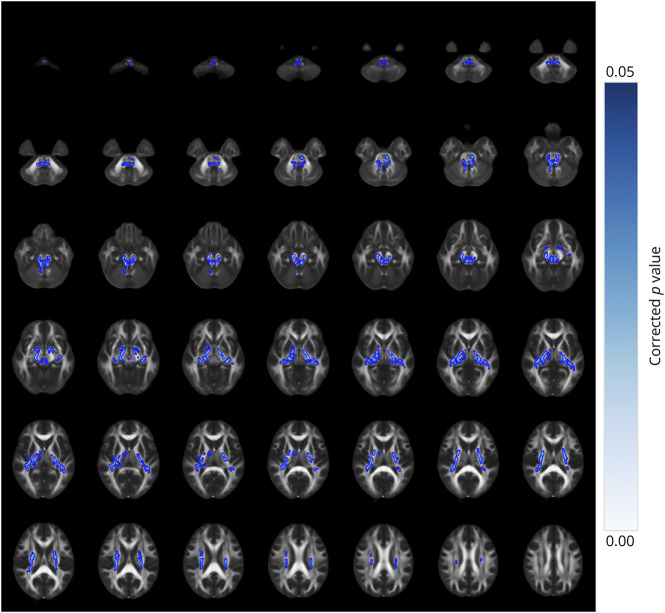

We performed TBSS analysis to investigate differences in WM microstructure among patients with SCA3-SP, SCA3-NSP, and HCs. As for DTI metrics, we noted statistically significant differences in FA, AD, and RD, as well as MD metrics in extensive regions among the 3 groups (p < 0.05, FWE-corrected, eFigure 4). However, no differences were identified in the FA, AD, RD, or MD metrics between the SCA3-SP and SCA3-NSP subgroups (p > 0.05). For the NODDI metrics, the ANOVA results revealed differences across broad brain regions among the 3 groups (p < 0.05, FWE-corrected, eFigure 5). Furthermore, within the SCA3-SP subgroup, lower NDI values were found in several regions, including the bilateral cerebral peduncles, optic radiation, internal capsules, fornix/stria terminalis, corona radiata, medial lemniscus, and superior and inferior cerebellar peduncles, when compared with those in the SCA3-NSP subgroup (p < 0.05, FWE-corrected; Figure 4). No differences in Viso and ODI scores were detected between the SCA3-SP and SCA3-NSP subgroups.

Figure 4. TBSS Analysis of Neurite Density Index (NDI) Metrics Across Different Subgroups.

Depicted are brain regions characterized by reduced NDI values of the SCA3 patients with spastic paraplegia (SCA3-SP) when compared with SCA3 patients with nonspastic paraplegia (SCA3-NSP). A post hoc test, p < 0.05, FWE-corrected.

Discussion

We conducted this study in a cohort of patients with SCA3 to investigate the clinical characteristics and alterations of the clinical pattern of SCA3-SP using multiparametric brain imaging. Our data demonstrated that the SCA3-SP subgroup had earlier AAO, larger expanded CAG repeats, and a more rapid progression rate based on SARA and ICARS scores than the SCA3-NSP subgroup. The MRI results revealed reduced GM volumes within the precentral gyrus, middle frontal gyrus, and precuneus of the SCA3-SP subgroup, along with a lower NDI value of the WM microstructure, when compared with those in the SCA3-NSP subgroups.

As the onset of SCA3 is typically during middle age,1 in contrast to HSP, which is more frequently associated with early childhood through late adulthood,18,19 the early onset and presence of spastic paraplegia can lead to misdiagnosis of patients with SCA3. In our study, we demonstrated that the SCA3-SP subgroup presented with disease at an earlier age at onset than the SCA3-NSP subgroup, which is an additional distinctive aspect between the 2 subgroups, along with a larger number of expanded CAG repeats. Of interest, we further noticed that the number of expanded CAG repeats was inversely proportional to the AAO, clarifying the variability in the onset of SCA3-SP to some extent.

Owing to the controversial results obtained from certain case studies that associated patients with SCA3 of spastic paraplegia with a lack of atrophy within the midbrain, pons, or cerebellum by MRI assessments10,32 in contrast to a more recent study of SCA3 with both spastic paraplegia and cerebellar signs, accompanied by atrophy within the cerebellum and spinal cord,33 we investigated patients with SCA3-SP with an average age of 28.6 years, with cerebellar signs. Volumetric MRI data indicated that patients with SCA3-SP exhibited atrophy in both the cerebellum and brainstem compared with that of HCs. In SCA3-SP, cerebellar signs and other symptoms, even if not detected in the first instance, appeared a few years later.

The distinctive pathologic characteristic of SCA3 involves the progressive degeneration of cerebellar cells and afferent and efferent fibers.13,34 By contrast, HSP is associated with degeneration primarily of the length-dependent CST and dorsal column.13,18 Furthermore, in this study, the SCA3-SP subgroup showed GM volume loss in the right precentral gyrus, in contrast to the SCA3-NSP subgroup. In addition, the NDI values decreased in the bilateral CST, internal capsule, cerebral peduncles, superior cerebellar peduncles, inferior cerebellar peduncles, and other brain regions in the SCA3-SP subgroup. Although direct histopathologic data would be auspicial to confirm these findings, the multimodal MRI data we used revealed volumetric loss in the right precentral gyrus and a decreased neurite density of the CST among patients with SCA3-SP, providing valuable insights into the understanding of the clinical manifestation of spastic paraplegia in the context of patients with SCA3.

Our study had several limitations. First, the MRI findings were derived from cross-sectional data, restricting our ability to infer time-dependent results and necessitating further investigation to confirm our findings. Second, MRI examinations were conducted on a relatively small sample size, and because of the lack of extensive follow-up data, linear models were adopted, although this may not be consistent with the trajectory of SCA3. Finally, although it provides a unique opportunity to noninvasively investigate neurite pathology at the microscopic level, it would be ideal if future investigations seek confirmation based on postmortem histopathology.

In summary, our data shed light on the clinical and multiparametric imaging characteristics of SCA3-SP, offering valuable insights into distinguishing between SCA3-SP subtypes. These findings have the potential to provide essential guidance for designing future clinical trials specifically tailored to address the therapeutic needs of this distinctive subtype.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the patients, families, caregivers, and OSCCAR members who participated in this research.

Glossary

- AD

axial diffusivity

- CST

corticospinal tract

- DTI

diffusion tensor imaging

- FA

fractional anisotropy

- FDR

false discovery rate

- FWE

family-wise error

- GM

gray matter

- HCs

healthy controls

- HSP

hereditary spastic paraplegia

- ICARS

International Cooperative Ataxia Rating Scale

- MD

mean diffusivity

- NDI

neurite density index

- ODI

orientation dispersion index

- RD

radial diffusivity

- SARA

Scale for the Assessment and Rating of Ataxia

- SCA3

spinocerebellar ataxia type 3

- SCA3-NSP

SCA3 patients with nonspastic paraplegia

- SCA3-SP

SCA3 patients with spastic paraplegia

- T1W

T1-weighted

- TBSS

tract-based spatial statistics

- TIV

total intracranial volume

- VBM

voxel-based morphometry

- WM

white matter

Appendix. Authors

| Name | Location | Contribution |

| Zhi-Xian Ye, MSc | Department of Neurology and Institute of Neurology of First Affiliated Hospital, Institute of Neuroscience, and Fujian Key Laboratory of Molecular Neurology, Fujian Medical University, Fuzhou, China | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data; analysis or interpretation of data |

| Hao-Ling Xu, MSc | Department of Neurology and Institute of Neurology of First Affiliated Hospital, Institute of Neuroscience, and Fujian Key Laboratory of Molecular Neurology, Fujian Medical University, Fuzhou, China | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data; analysis or interpretation of data |

| Na-Ping Chen, MSc | Department of Radiology of First Affiliated Hospital, Fujian Medical University, Fuzhou, China | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data; analysis or interpretation of data |

| Xin-Yuan Chen, MD | Department of Rehabilitation Medicine of First Affiliated Hospital, Fujian Medical University, Fuzhou, China | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data |

| Meng-Cheng Li, MSc | Department of Radiology of First Affiliated Hospital, Fujian Medical University, Fuzhou, China | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data |

| Ru-Ying Yuan, MD | Department of Neurology and Institute of Neurology of First Affiliated Hospital, Institute of Neuroscience, and Fujian Key Laboratory of Molecular Neurology, Fujian Medical University, Fuzhou, China | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data |

| Wei Lin, BSc | Department of Neurology and Institute of Neurology of First Affiliated Hospital, Institute of Neuroscience, and Fujian Key Laboratory of Molecular Neurology, Fujian Medical University, Fuzhou, China | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data |

| Liangliang Qiu, MD | Department of Neurology and Institute of Neurology of First Affiliated Hospital, Institute of Neuroscience, and Fujian Key Laboratory of Molecular Neurology; Department of Neurology, National Regional Medical Center, Binhai Campus of the First Affiliated Hospital, Fujian Medical University, Fuzhou, China | Major role in the acquisition of data |

| Minting Lin, MD | Department of Neurology and Institute of Neurology of First Affiliated Hospital, Institute of Neuroscience, and Fujian Key Laboratory of Molecular Neurology; Department of Neurology, National Regional Medical Center, Binhai Campus of the First Affiliated Hospital, Fujian Medical University, Fuzhou, China | Major role in the acquisition of data |

| Wan-Jin Chen, MD, PhD | Department of Neurology and Institute of Neurology of First Affiliated Hospital, Institute of Neuroscience, and Fujian Key Laboratory of Molecular Neurology; Department of Neurology, National Regional Medical Center, Binhai Campus of the First Affiliated Hospital, Fujian Medical University, Fuzhou, China | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data |

| Ning Wang, MD, PhD | Department of Neurology and Institute of Neurology of First Affiliated Hospital, Institute of Neuroscience, and Fujian Key Laboratory of Molecular Neurology; Department of Neurology, National Regional Medical Center, Binhai Campus of the First Affiliated Hospital, Fujian Medical University, Fuzhou, China | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data |

| Jian-Ping Hu, MD, PhD | Department of Radiology of First Affiliated Hospital, Fujian Medical University, Fuzhou, China | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; study concept or design; analysis or interpretation of data |

| Ying Fu, MD, PhD | Department of Neurology and Institute of Neurology of First Affiliated Hospital, Institute of Neuroscience, and Fujian Key Laboratory of Molecular Neurology; Department of Neurology, National Regional Medical Center, Binhai Campus of the First Affiliated Hospital, Fujian Medical University, Fuzhou, China | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; study concept or design; analysis or interpretation of data |

| Shi-Rui Gan, MD | Department of Neurology and Institute of Neurology of First Affiliated Hospital, Institute of Neuroscience, and Fujian Key Laboratory of Molecular Neurology; Department of Neurology, National Regional Medical Center, Binhai Campus of the First Affiliated Hospital, Fujian Medical University, Fuzhou, China | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data; study concept or design; analysis or interpretation of data |

Study Funding

This work was supported by the grants 82230039 (N.W.) and U21A20360 (Y.F.) from the National Natural Science Foundation of China, and by the grant 2021Y9128 (S.R.G.) from Joint Funds for the Innovation of Science and Technology of Fujian Province.

Disclosure

The authors report no relevant disclosures. Go to Neurology.org/NG for full disclosures.

References

- 1.Klockgether T, Mariotti C, Paulson HL. Spinocerebellar ataxia. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2019;5(1):24. doi: 10.1038/s41572-019-0074-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Da Silva J, Teixeira-Castro A, Maciel P. From pathogenesis to novel therapeutics for spinocerebellar ataxia type 3: evading potholes on the way to translation. Neurotherapeutics. 2019;16(4):1009-1031. doi: 10.1007/s13311-019-00798-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rüb U, Schöls L, Paulson H, et al. Clinical features, neurogenetics and neuropathology of the polyglutamine spinocerebellar ataxias type 1, 2, 3, 6 and 7. Prog Neurobiol. 2013;104:38-66. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2013.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pedroso JL, Franca MC Jr., Braga-Neto P, et al. Nonmotor and extracerebellar features in Machado-Joseph disease: a review. Mov Disord. 2013;28(9):1200-1208. doi: 10.1002/mds.25513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Durr A. Autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxias: polyglutamine expansions and beyond. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9:885-894. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70183-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spinella GM, Sheridan PH. Research initiatives on Machado-Joseph disease: National Institute of neurological disorders and Stroke Workshop summary. Neurology. 1992;42(10):2048-2051. doi: 10.1212/wnl.42.10.2048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paulson H. Machado-Joseph disease/spinocerebellar ataxia type 3. Handb Clin Neurol. 2012;103:437-449. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-51892-7.00027-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mendonça N, França MC Jr., Gonçalves AF, Januário C. Clinical features of Machado-Joseph disease. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2018;1049:255-273. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-71779-1_13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sakai T, Kawakami H. Machado-Joseph disease: a proposal of spastic paraplegic subtype. Neurology. 1996;46(3):846-847. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gan SR, Zhao K, Wu ZY, Wang N, Murong SX. Chinese patients with Machado-Joseph disease presenting with complicated hereditary spastic paraplegia. Eur J Neurol. 2009;16(8):953-956. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2009.02639.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu H, Lin J, Shang H. Voxel-based meta-analysis of gray matter and white matter changes in patients with spinocerebellar ataxia type 3. Front Neurol. 2023;14:1197822. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2023.1197822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Inada BSY, Rezende TJR, Pereira FV, et al. Corticospinal tract involvement in spinocerebellar ataxia type 3: a diffusion tensor imaging study. Neuroradiology. 2021;63(2):217-224. doi: 10.1007/s00234-020-02528-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Synofzik M, Schule R. Overcoming the divide between ataxias and spastic paraplegias: shared phenotypes, genes, and pathways. Mov Disord. 2017;32(3):332-345. doi: 10.1002/mds.26944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.D'Abreu A, Franca MC Jr., Paulson HL, Lopes-Cendes I. Caring for Machado-Joseph disease: current understanding and how to help patients. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2010;16(1):2-7. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2009.08.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang XL, Li XB, Cheng FF, et al. Spinocerebellar ataxia type 3 with dopamine-responsive dystonia: a case report. World J Clin Cases. 2021;9(28):8552-8556. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i28.8552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuo MC, Tai CH, Tseng SH, Wu RM. Long-term efficacy of bilateral subthalamic deep brain stimulation in the parkinsonism of SCA 3: a rare case report. Eur J Neurol. 2022;29(8):2544-2547. doi: 10.1111/ene.15339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Durr A, Stevanin G, Cancel G, et al. Spinocerebellar ataxia 3 and Machado-Joseph disease: clinical, molecular, and neuropathological features. Ann Neurol. 1996;39(4):490-499. doi: 10.1002/ana.410390411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shribman S, Reid E, Crosby AH, Houlden H, Warner TT. Hereditary spastic paraplegia: from diagnosis to emerging therapeutic approaches. Lancet Neurol. 2019;18(12):1136-1146. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(19)30235-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Salinas S, Proukakis C, Crosby A, Warner TT. Hereditary spastic paraplegia: clinical features and pathogenetic mechanisms. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7(12):1127-1138. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70258-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Trouillas P, Takayanagi T, Hallett M, et al. International cooperative ataxia rating scale for pharmacological assessment of the cerebellar syndrome. The Ataxia Neuropharmacology Committee of the World Federation of Neurology. J Neurol Sci. 1997;145(2):205-211. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(96)00231-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schmitz-Hubsch T, du Montcel ST, Baliko L, et al. Scale for the assessment and rating of ataxia: development of a new clinical scale. Neurology. 2006;66(11):1717-1720. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000219042.60538.92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li QF, Dong Y, Yang L, et al. Neurofilament light chain is a promising serum biomarker in spinocerebellar ataxia type 3. Mol Neurodegener. 2019;14(1):39. doi: 10.1186/s13024-019-0338-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.FreeSurfer Software Suite. Updated June 26, 2023. Accessed March 2024. surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu/ [Google Scholar]

- 24.Statistical Parametric Mapping. Updated January 13, 2020. Accessed March 2024. fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/ [Google Scholar]

- 25.Andica C, Kamagata K, Hatano T, et al. MR biomarkers of degenerative brain disorders derived from diffusion imaging. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2020;52(6):1620-1636. doi: 10.1002/jmri.27019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.FMRIB Software Library. Updated October 2018. Accessed March 2024. fsl.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl/fslwiki/ [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang H, Schneider T, Wheeler-Kingshott CA, Alexander DC. NODDI: practical in vivo neurite orientation dispersion and density imaging of the human brain. Neuroimage. 2012;61(4):1000-1016. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.03.072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rasgado-Toledo J, Shah A, Ingalhalikar M, Garza-Villarreal EA. Neurite orientation dispersion and density imaging in cocaine use disorder. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2022;113:110474. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2021.110474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.NODDI Matlab Toolbox. Updated July 6, 2021. Accessed March 2024. surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu/ [Google Scholar]

- 30.Laird NM, Ware JH. Random-effects models for longitudinal data. Biometrics. 1982;38(4):963-974. doi: 10.2307/2529876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saunders-Pullman R, Mirelman A, Alcalay RN, et al. Progression in the LRRK2-asssociated Parkinson disease population. JAMA Neurol. 2018;75(3):312-319. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.4019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kaneko A, Narabayashi Y, Itokawa K, et al. A case of Machado-Joseph disease presenting with spastic paraparesis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1997;62(5):542-543. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.62.5.542-a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Song Y, Liu Y, Zhang N, Long L. Spinocerebellar ataxia type 3/Machado-Joseph disease manifested as spastic paraplegia: a clinical and genetic study. Exp Ther Med. 2015;9(2):417-420. doi: 10.3892/etm.2014.2136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Watanave M, Hoshino C, Konno A, et al. Pharmacological enhancement of retinoid-related orphan receptor α function mitigates spinocerebellar ataxia type 3 pathology. Neurobiol Dis. 2019;121:263-273. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2018.10.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.