Abstract

OBJECTIVES:

To estimate the expected value of undertaking a future randomized controlled trial of thresholds used to initiate invasive ventilation compared with usual care in hypoxemic respiratory failure.

PERSPECTIVE:

Publicly funded healthcare payer.

SETTING:

Critical care units capable of providing invasive ventilation and unconstrained by resource limitations during usual (nonpandemic) practice.

METHODS:

We performed a model-based cost-utility estimation with individual-level simulation and value-of-information analysis focused on adults, admitted to critical care, receiving noninvasive oxygen. In the primary scenario, we compared hypothetical threshold A to usual care, where threshold A resulted in increased use of invasive ventilation and improved survival compared with usual care. In the secondary scenario, we compared hypothetical threshold B to usual care, where threshold B resulted in decreased use of invasive ventilation and similar survival compared with usual care. We assumed a willingness-to-pay of 100,000 Canadian dollars (CADs) per quality-adjusted life year.

RESULTS:

In the primary scenario, threshold A was cost-effective compared with usual care due to improved hospital survival (78.1% vs. 75.1%), despite more use of invasive ventilation (62% vs. 30%) and higher lifetime costs (86,900 vs. 75,500 CAD). In the secondary scenario, threshold B was cost-effective compared with usual care due to similar survival (74.5% vs. 74.6%) with less use of invasive ventilation (20.2% vs. 27.6%) and lower lifetime costs (71,700 vs. 74,700 CAD). Value-of-information analysis showed that the expected value to Canadian society over 10 years of a 400-person randomized trial comparing a threshold for invasive ventilation to usual care in hypoxemic respiratory failure was 1.35 billion CAD or more in both scenarios.

CONCLUSIONS:

It would be highly valuable to society to identify thresholds that, in comparison to usual care, either increase survival or reduce invasive ventilation without reducing survival.

Keywords: cost-effectiveness analysis, hypoxemic respiratory failure, noninvasive oxygen strategies, thresholds for intubation, value-of-information analysis

KEY POINTS.

Question: What is the expected value to society of a randomized controlled trial comparing intubation guided by usual care to intubation guided by a physiologic threshold in patients with hypoxemic respiratory failure?

Findings: In this health economic evaluation, we found that a randomized trial showing that a threshold can either improve survival compared with usual care, or reduce invasive ventilation while preserving survival compared with usual care, would be expected to generate 1.35 billion Canadian dollars or more in quality-adjusted life years and cost savings for Canadian society over 10 years.

Meaning: Further study of thresholds for invasive ventilation would be valuable to society.

Acute hypoxemic respiratory failure comprises at least 10% of ICU admissions worldwide, is associated with ICU mortality of 25–40%, and can cause long-term functional impairment in survivors (1–4). Invasive ventilation is a potentially life-saving therapy instituted in severe cases, but it can lead to adverse events, including periprocedural cardiac arrest (5, 6), ventilator-associated pneumonia, delirium, and ICU-acquired weakness (7–9). The decision to initiate invasive ventilation is based on expert opinion and clinical experience, with little data available (10). Observational research has investigated different thresholds for initiating invasive ventilation, with variation in predicted rates of invasive ventilation and mortality (11, 12).

Further study of when to intubate in hypoxemic respiratory failure will require a substantial investment of time and funding, because the relationship between outcomes and intubation guided by thresholds based on hypoxemia, work of breathing, or other clinical variables is uncertain (12). This investment may not be worthwhile, if thresholds that result in clinically plausible rates of invasive ventilation and mortality do not generate benefits to society relative to usual care in terms of quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) or costs (13–15). Health economic analysis has been used to assess the economic value of a randomized trial of IV immunoglobulin in sepsis, but otherwise its use in evaluating potential (as opposed to completed) research studies in critical care medicine has been limited (16).

In this study, we performed a model-based health economic analysis comparing usual care to multiple hypothetical thresholds for the initiation of invasive ventilation, to estimate the value of further study of thresholds in a randomized controlled trial.

METHODS

Here, we provide an overview of the modeling methods and approach, with a more comprehensive version in the Supplement (http://links.lww.com/CCX/B346). We performed a model-based cost-utility and value-of-information analysis comparing usual care to a threshold for initiation of invasive ventilation for people with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure.

We adopted the publicly funded healthcare payer perspective, a lifetime horizon, and discounted future clinical and cost outcomes by 1.5% annually, in accordance with guidelines from the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (17). We followed the Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards checklist (Supplement, http://links.lww.com/CCX/B346) (14, 17–19). In Table e1 (http://links.lww.com/CCX/B346), we have compiled a list of acronyms used in the article.

This project was developed in accordance with the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki, and access to and use of the de-identified Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care, Version IV (MIMIC-IV) database for research with a waiver for informed consent has been approved by the institutional review board of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, MA (2001-P-001699/14) (20, 21). All other data were drawn from published articles. All analysis code is available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7603995.

Target Population

The target population was adults at admission to ICU with non-COVID acute hypoxemic respiratory failure, receiving oxygen via high-flow nasal cannula, nonrebreather mask, or noninvasive positive pressure ventilation.

Scenarios

From a health economic perspective, there are two relevant scenarios: thresholds with increased invasive ventilation and decreased mortality compared with usual care (early invasive ventilation beneficial, threshold A, primary scenario), and thresholds with decreased invasive ventilation and similar mortality compared with usual care (late invasive ventilation safe, threshold B, secondary scenario). Other scenarios involve strategies that are obviously more cost-effective (similar or decreased invasive ventilation and decreased mortality compared with usual care), less cost-effective (increased invasive ventilation and similar mortality compared with usual care), or clinically unacceptable (increased mortality compared with usual care).

Strategies

We modeled health economic consequences using only the invasive ventilation rates and mortality rates that result from following a threshold. This allowed us to separate identifying the optimal threshold (not addressed in this article) from estimating the health economic impact of care guided by a threshold (the focus of this article).

We based invasive ventilation and mortality rates for each threshold on a recent observational study predicting clinical outcomes that would result from following different oxygenation thresholds to initiate invasive ventilation in hypoxemic respiratory failure (12). The primary scenario (threshold A) was based on the findings from the MIMIC-IV database, using a threshold of a saturation to Fio2 ratio of 110 or less. The secondary scenario (threshold B) was based on the findings from the Amsterdam University Medical Centres database, using a threshold of a saturation to Fio2 of 88 or less (Table e2, http://links.lww.com/CCX/B346).

Model Structure and Outputs

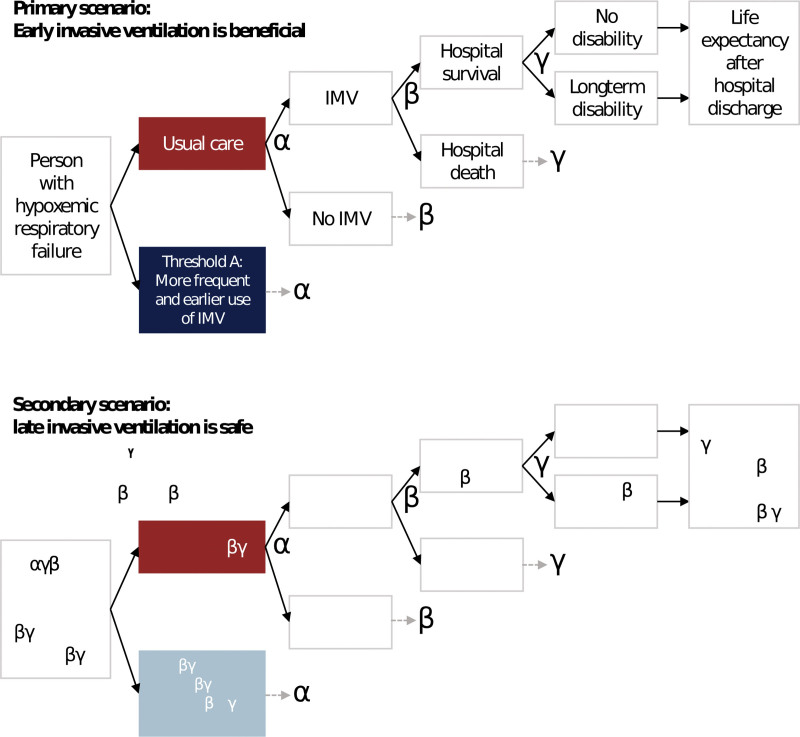

We built an individual-level simulation model to describe respiratory failure with respect to respiratory support and hospital outcomes (Fig. 1). Model outputs included clinical outcomes and costs. The primary clinical outcome was QALYs. Costs were denominated in 2022 Canadian dollars (CADs).

Figure 1.

Diagram of health economic model. This diagram shows the model structure, which is the same for both scenarios. An individual begins on the left, at “Person with hypoxemic respiratory failure.” Each individual was simulated through each strategy (usual care or threshold), with the same tree structure for each. The only “decision node” is the first node, where the strategy is chosen. All other nodes are “chance nodes.” The diagram has been simplified using α, β, and γ to denote identical branches of the tree structure. The diagram also shows the two scenarios with their hypothetical thresholds: Primary (early invasive ventilation beneficial, threshold A) and secondary (late invasive ventilation safe, threshold B). IMV = invasive mechanical ventilation.

For each individual, we simulated the following events, including whether they occurred and associated costs: invasive ventilation, hospital survival, life expectancy of hospital survivors, and whether hospital survivors had long-term disability. Disability was defined as functional impairment requiring assistance for bathing or stair locomotion (Supplement section 10.6, http://links.lww.com/CCX/B346).

Assumptions

Key assumptions about model structure and parameter distributions are highlighted in Table 1. All people were cared for in an ICU. Invasive ventilation availability for individuals was unaffected by invasive ventilation use in others, approximating usual critical care, as opposed to care during pandemic surges where human and ventilator resources may be scarce (22–24). We assumed no deviation from thresholds, no reinitiation of invasive ventilation, no ICU readmission, and no utility during hospitalization. Societal willingness-to-pay (WTP) was set at an incremental 100,000 CADs per QALY gained (17, 25).

TABLE 1.

Key Assumptions, Distributions, and Definitions

| Assumptions | Explanation | Limitation |

|---|---|---|

| Model structure | ||

| Intensive care setting | Some input parameters were derived using individual-level data of patients cared for in an ICU | Many patients for whom the decision to initiate invasive ventilation is relevant are cared for in emergency departments or hospital wards |

| Independent individuals | Use of invasive ventilation in a given patient was unaffected by invasive ventilation use in other patients, approximating nonpandemic usual critical care in well-resourced healthcare systems | During pandemic surges, the number of available ventilators or staff may limit the use of invasive ventilation |

| Perfect adherence | We assumed no crossover between clinical strategies | The cost-effectiveness and value of information of strategies other than usual care will be attenuated by crossover to usual care in trials or clinical practice |

| No reintubation or ICU readmission | We modeled only the first episode of invasive ventilation and ICU admission because modeling subsequent episodes would only be helpful for a small subset of patients | If there were significant differences in reintubation or readmission rates across strategies, model results would differ |

| Willingness-to-pay 100,000 CAD per QALY | This is within the willingness-to-pay range based on gross domestic product suggested by the World Health Organization (25) | Higher or lower willingness-to-pay affects the conversion between QALYs and CAD and will impact the value-of-information analysis |

| Cohort-level (second level) variables | ||

| Probabilities drawn from beta distributions | The probabilities of binary clinical events (invasive ventilation, hospital mortality, long-term disability) were drawn from beta distributions, then used to simulate individual patient outcomes | |

| Costs drawn from gamma distributions | Gamma distributions, which are greater than 0 and allow for long tails, are a common choice for modeling costs | The mean and median can be quite different in a gamma distribution |

| Coefficients drawn from normal distributions | Regression coefficients were used to individualize the distributions of duration of invasive ventilation, ICU stay, ward stay, and life after hospital survival | The relationship between coefficients and durations was derived from the Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care, Version IV database and may be different in other cohorts |

| Clinical event (first level) variables | ||

| Binary events drawn from binary distributions | The occurrence of binary events (invasive ventilation, hospital mortality, long-term disability) were simulated for each patient using binary distributions with probabilities drawn from beta distributions (see above) | |

| Durations drawn from Weibull distributions | Durations (invasive ventilation, ICU stay while not ventilated, hospital ward stay, life expectancy after hospital survival) were drawn from Weibull distributions including coefficients for individual patient covariates such as age, sex | Parametric time-to-event distributions may not extrapolate to other cohorts or care settings |

CADs = Canadian dollars, QALYs = quality-adjusted life years.

Data Sources and Parameters

We performed a literature search for each parameter. We favored recent estimates specific to the North American or Northern European context and full details of parameter values, distributions, and data sources are available in Tables e3–e6 and Figure e1 (http://links.lww.com/CCX/B346) (4, 26–40).

Analysis

We compared strategies using the net monetary benefit, defined as QALYS × WTP–costs. We reported the incremental cost-utility ratio for nondominated strategies relative to usual care. We built the model in TreeAge Pro (v2021 R2) (TreeAge Software, Williamstown, MA) and analyzed outputs in R (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) (41, 42). We reported means and 95% credible intervals. We showed, for each strategy and at WTP ranging from 0 to 200,000 CAD, the probability of having the highest net monetary benefit.

Value-of-Information Analysis

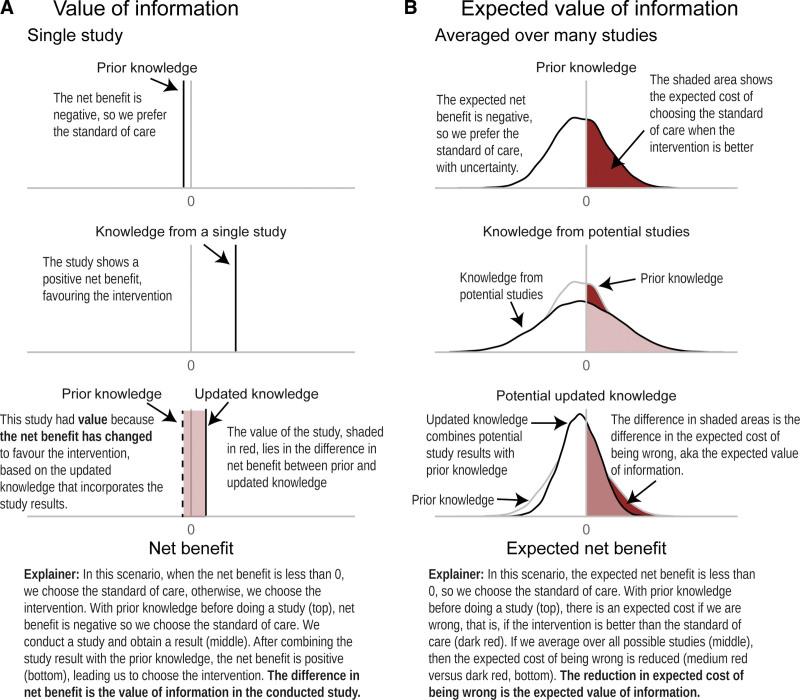

Value-of-information analysis quantifies the cost of deciding now, with imperfect information, compared with an alternative decision made once more information is available (43). The value accrues because making a decision once more information is available could increase the chance of choosing the most cost-effective option (Fig. 2). Value of information is usually quantified in terms of monetary benefit, but it encompasses value due to both costs and QALYs.

Figure 2.

What do we mean by the value of information?. This diagram explains value of information and expected value of information comparing two strategies, standard of care and intervention. Positive net benefit favors the intervention, and negative net benefit favors the standard of care. A, We begin with prior knowledge, summarized by a vertical black line showing the expected net benefit. Based on this net benefit, standard of care is preferred. A single study is conducted showing that the intervention is preferred. This study could have had a different result (see right-hand column for distribution of study results). After combining the information from the single study with prior knowledge to make an updated state of knowledge, net benefit is positive so the intervention is preferred. Without the new study, we would have opted for standard of care, and incurred a cost equal to the difference between incremental net benefit in updated knowledge compared with current knowledge (red shaded area). The study has value because it precipitated a change in decision-making. B, We begin with prior knowledge including the distribution of uncertainty around the net benefit. The expected net benefit favors the standard of care. We update the prior knowledge using the information from a new study, but there is a distribution of potential study results (based on prior knowledge). When we combine these distributions, we end up with a new distribution of potential updated knowledge. The opportunity cost of choosing the standard of care (the cost of choosing standard of care when the intervention is actually better) has been reduced, and this is the expected value of information.

For this clinical problem, the most relevant study design to reduce parameter uncertainty would be a randomized controlled trial. We report the estimated expected value of sample information (EVSI) for randomized trials with sample sizes from 100 to 3200 participants.

RESULTS

Clinical Outcomes

As expected, the primary scenario showed higher rates of invasive ventilation (62.4% vs. 30.4%) and hospital survival (78.1% vs. 75.1%) comparing threshold A to usual care (Table 2). Long-term disability was 11.5% (threshold A) and 6.2% (usual care). This resulted in slightly more QALYs (8.45 vs. 8.28) and higher lifetime costs (86,900 vs. 75,500) for threshold A compared with usual care.

TABLE 2.

Model Outputs, Primary Scenario

| Outcome | Primary Scenario (Early Invasive Ventilation Beneficial) | Secondary Scenario (Late Invasive Ventilation Safe) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Usual Care | Threshold A | Usual Care | Threshold B | |

| Durations (d) | ||||

| ICU, non-IMV duration | 4.65 (3.42–6.43) | 4.51 (3.26–6.24) | 4.67 (3.34–6.46) | 4.72 (3.42–6.7) |

| IMV duration (among ventilated people) | 8.62 (6.15–12.8) | 8.93 (6.35–13.3) | 8.5 (5.76–12.4) | 8.21 (5.52–12.2) |

| Ward duration | 5.69 (4.24–7.66) | 5.58 (4.12–7.49) | 5.68 (4.24–7.76) | 5.73 (4.25–7.75) |

| Hospital outcomes (%) | ||||

| Invasive ventilation | 30.4 (16.6–48.7) | 62.4 (42.8–80.2) | 27.6 (13.1–45.4) | 20.2 (7.6–38.1) |

| Survival | 75.1 (53.6–92.1) | 78.1 (53.6–93.4) | 74.5 (51.5–91.8) | 74.6 (53.5–92) |

| Long-term disability | 6.23 (2.88–11.3) | 11.5 (6.46–17.8) | 5.73 (2.1–10.8) | 4.56 (1.4–9.7) |

| Lifetime outcomes | ||||

| Life expectancy (yr) | 10.9 (7.35–14) | 11.3 (7.36–14.4) | 10.8 (7.18–14.1) | 10.7 (7.25–13.9) |

| Quality-adjusted life years | 8.28 (5.56–10.6) | 8.45 (5.57–10.8) | 8.2 (5.46–10.7) | 8.23 (5.58–10.7) |

| Cost (1000s CAD) | 75.5 (62.9–90.3) | 86.9 (73.2–103) | 74.7 (62.7–88.5) | 71.7 (61–85) |

| Net monetary benefit (1000s CAD) | 752 (487–986) | 758 (472–990) | 746 (474–990) | 751 (488–992) |

| Comparative outcomes | ||||

| Probability of highest net monetary benefit | 0.487 | 0.513 | 0.497 | 0.503 |

| Incremental cost-utility ratio (CAD) | Reference | 67,400 | 0 | –115,000 |

CADs = Canadian dollars, IMV = invasive mechanical ventilation.

The model outputs with the mean and 95% credible interval for each strategy.

Net monetary benefit calculated using a willingness-to-pay of 100,000 CAD per quality-adjusted life year. Incremental cost-utility ratio calculated for each threshold compared with usual care.

Also as expected, the secondary scenario showed a lower rate of invasive ventilation (20.2% vs. 27.6%) and similar rate of hospital survival (74.6% vs. 74.5%; Table 2). ICU length-of-stay, duration of invasive ventilation, and long-term disability rates were all slightly lower with threshold B than usual care. This resulted in similar QALYs and lower lifetime costs (71,700 vs. 74,700) for threshold B compared with usual care.

Cost-Utility Tradeoffs

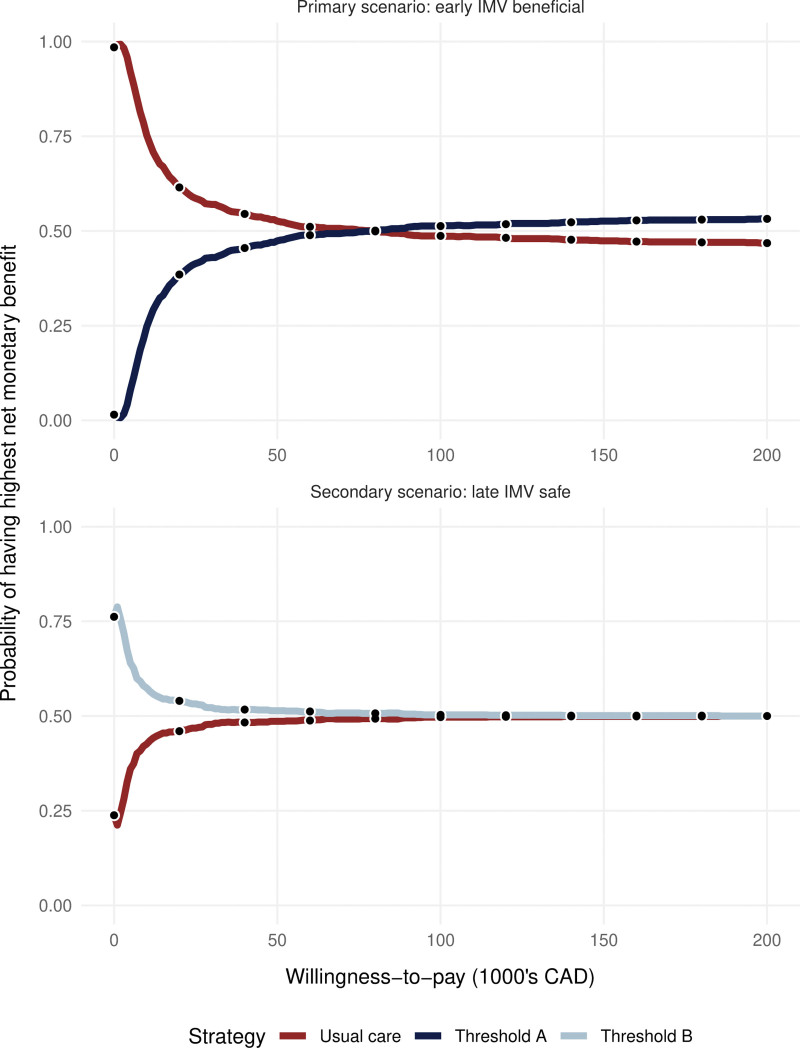

In the primary scenario, at the prespecified WTP of 100,000 CAD, mean net monetary benefit was greater with threshold A than usual care (Table 2). However, the probability of threshold A or usual care having the highest net monetary benefit was similar and close to 0.5, indicating residual uncertainty in the model outputs. Figure 3 shows the similarity between the probabilities of each threshold having the highest net monetary benefit. The incremental cost-utility ratio for threshold A when compared with usual care was 67,400 CAD per QALY.

Figure 3.

Cost-effectiveness acceptability curve. The proportion of iterations where each strategy has the highest net monetary benefit, vs. willingness to pay, for both scenarios. In the primary scenario, threshold A becomes more cost-effective than usual care at a willingness-to-pay of 75,000 or more per quality-adjusted life year (QALY). In the secondary scenario, threshold B is always slightly more cost-effective. In both scenarios, the difference in cost-effectiveness is small and uncertain (probability of being most cost-effective hovers around 0.5 at willingness-to-pay value of 100,000 Canadian dollars [CADs] per QALY). IMV = invasive mechanical ventilation.

In the secondary scenario, at the same WTP of 100,000 CAD, mean net monetary benefit was greater with threshold B than usual care (Table 2). Again, the probability of threshold B or usual care having the highest net monetary benefit was similar and close to 0.5 (Fig. 3). The incremental cost-utility ratio for threshold B compared with usual care was –115,000 CAD per QALY.

Value of Information

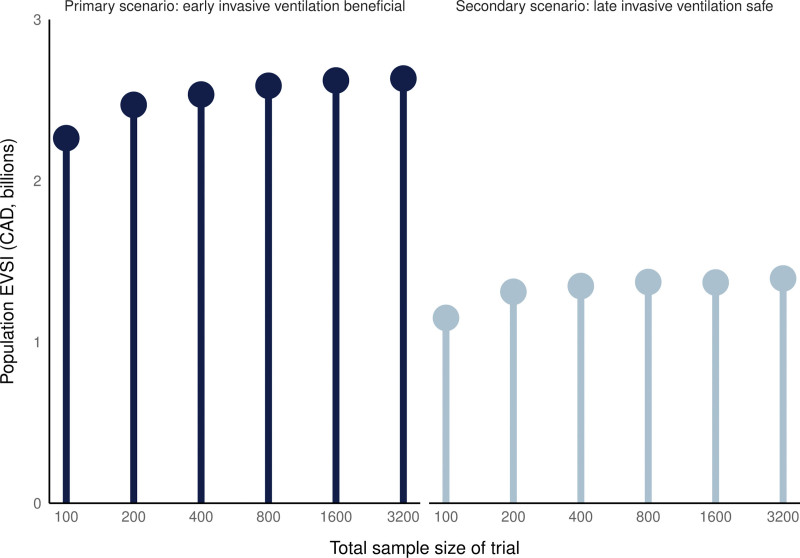

In the primary scenario, where early invasive ventilation was beneficial, a randomized trial of 400 patients had an EVSI of 54,160 CAD per-person (Fig. 4). Using a national annual incidence of 5000 eligible people per year (29) and a discount rate of 1.5%, the population EVSI for a randomized trial of 400 participants was 2.53 billion CAD over 10 years.

Figure 4.

Population expected value of a randomized trial by sample size. The population expected value of sample information (EVSI, y-axis) for randomized trials of different total sizes (x-axis, logarithmic scale) for both the primary scenario (left) and secondary scenario (right). The EVSI captures the value of the additional information gleaned from a study of a particular size. The value comes from an improved probability of correctly identifying the most cost-effective strategy. The population EVSI is derived by multiplying the per-person EVSI by the annual incidence of eligible people in Canada (5000) and the duration of information relevance (10 yr), discounting future benefits by 1.5% per year. For these values of the EVSI, we used a willingness-to-pay of 100,000 Canadian dollars (CADs). Note that these values only describe value that accrues to the Canadian population.

In the secondary scenario, where late invasive ventilation was safe, a randomized trial of 400 patients had an EVSI of 28,776 CAD per-person, which amounted to a population value of 1.35 billion CAD over 10 years. Additional value-of-information results are available in the Supplement (http://links.lww.com/CCX/B346).

DISCUSSION

In this health economic evaluation comparing usual care to hypothetical thresholds for initiating invasive ventilation in hypoxemic respiratory failure, we analyzed two scenarios. In the primary scenario, where earlier invasive ventilation according to a hypothetical threshold had lower mortality than usual care, we found that the threshold was more cost-effective than usual care. A 400-person randomized controlled trial in this scenario had an expected value to Canadian society of 2.53 billion dollars. In the secondary scenario, where later invasive ventilation according to a hypothetical threshold had similar mortality to usual care, the threshold was again more cost-effective than usual care. The expected societal value of a 400-person randomized trial remained high (1.35 billion CAD). These findings suggest that further research focused on identifying thresholds that can lead to improved mortality, or reduced invasive ventilation with similar mortality, would be immensely valuable for society.

Increased Use of Invasive Ventilation Can Be Cost-Effective, If It Improves Survival

The findings build on prior work by illustrating the net impact of survival, ventilator resource use, and disability on cost-effectiveness. Prior work has investigated the survival associated with particular thresholds for invasive ventilation but has not incorporated functional outcomes or costs (11, 12, 44). We found that a small improvement in survival associated with markedly increased use of invasive ventilation can be cost-effective. This provides important justification for studies investigating an early intubation approach. However, individuals may vary in the extent to which they value a life affected by weakness, dependence, and post-traumatic stress disorder (3). Further research needs to clarify what tradeoff between short-term increase in long-term disability risk is acceptable to people in this situation.

Further Study of Thresholds to Initiate Invasive Ventilation Would Be Valuable

The estimated expected value of a 400-person randomized trial on this topic was more than 1.35 billion CAD and far exceeds the cost of the proposed trial and associated studies. By comparison, the median cost of a clinical trial with more than 1000 participants testing a novel pharmaceutical agent is approximately 70 million CAD (45). This was driven more by a high estimated value of sample information per-patient (at least 28,776 CAD per eligible person) than a high incidence of the disease condition. By contrast, a value-of-information analysis of IV immunoglobulin use in septic shock had an estimated value of sample information of only 1049 CAD per-person for a similarly sized trial (16). Our per-patient EVSI is likely overestimated because the value captured in the EVSI assumes that all clinicians will incorporate the study findings into their decision-making (46, 47). However, our population EVSI could also be underestimated because it corresponds only to Canada, even though benefits would accrue to eligible people worldwide.

Another explanation for the high value of further study in this case is that there is significant uncertainty with current data. This uncertainty is evident in both scenarios because usual care had only a slightly smaller probability of being most cost-effective than the threshold. Even a small amount of additional information could increase the probability of the threshold being the most cost-effective, and consequently provide value to society. If the parameters used for the model had less uncertainty, which might be reasonable for a different clinical scenario, then further information would generate smaller changes in the cost-effectiveness analysis and provide less value to society.

Value-of-Information Analysis Could Inform Critical Care Research Priorities

Value-of-information analysis has been developed and recommended for use in setting research priorities (48, 49). This investigation highlights how value-of-information analysis could be used to help decision-makers assess the potential return of investment into different research topics. We identified two scenarios in which a threshold-based approach to the decision of when to intubate in hypoxemic respiratory failure could lead to different outcomes than usual care, and then assessed the expected health economic consequences of these two scenarios through modeling. Like all health economic models, these were based on many assumptions and so value-of-information analysis should not be used in isolation to decide on research priorities. Despite this limitation, value-of-information analysis can offer a powerful complementary quantitative perspective on the potential impact of a research program.

This Model-Based Evaluation Has Many Limitations

Our work has additional limitations. It is a model-based evaluation and may not incorporate enough nuance from clinical practice. Our target population is broad and includes individuals with heterogeneous diagnoses without specifying how the thresholds might accommodate this heterogeneity. We did not specify the details of the thresholds in either scenario, because those details are unknown at present, and so there may not exist thresholds that match with either scenario. Our results depend on many modeling decisions; different decisions may have led to different results (50). We discounted future outcomes according to the Canadian guideline-recommended 1.5% annually, but this rate may not reflect our current reality of increased inflation (17). Some costing data was from more than 10 years ago and may not reflect the costs of high-flow nasal cannula, which have become commonly used for nonintubated patients with hypoxemic respiratory failure. However, a prior health economic analysis in the United Kingdom found that high-flow nasal cannula use, compared with standard oxygen or noninvasive ventilation, was likely to be cost saving (51). The costing data from a prior acute respiratory distress syndrome cohort focused on a younger group of patients (3).

Our results were also limited by parameter validity. In particular, the relationship between thresholds, invasive ventilation rates, and mortality rates is uncertain and will require study in multiple cohorts. Some of our parameters were derived from individual-level data from MIMIC-IV, which means they are limited by the single-center and secondary nature of these data. We also do not have information on whether the probability of long-term disability varies by threshold choice, beyond the extent to which it is affected by the use of invasive ventilation. We included parameter uncertainty to address these limitations. Last, our results are most applicable in the Canadian healthcare context and may not be valid in systems with different practices around use of invasive ventilation and different resource availability or WTP.

CONCLUSIONS

It would be highly valuable to society to identify thresholds that, in comparison to usual care, either improve survival or reduce invasive ventilation without reducing survival.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the following for helpful comments: Allan Detsky.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Drs. Yarnell, Naimark, and Tomlinson were involved in concept. Drs. Yarnell, Barrett, Heath, Fowler, Sung, Naimark, and Tomlinson were involved in design. All authors were involved in data analysis and interpretation. Dr. Yarnell was involved in data acquisition. All authors were involved in drafting, revising for important intellectual content, final approval, and agreement to be accountable.

Dr. Yarnell was funded by the Canadian Institutes for Health Research Vanier Scholar program, the Eliot Phillipson Clinician Scientist Training Program, and the Clinician Investigator Program of the University of Toronto. Dr. Heath is supported by a Canada Research Chair in Statistical Trial Design and funded by the Discovery Grant Program of the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (RGPIN-2021-03366). Dr. Sung is supported by the Canada Research Chair in Pediatric Oncology Supportive Care. Dr. Fowler is the H. Barrie Fairley Professor of Critical Care at the University Health Network, Interdepartmental Division of Critical Care Medicine, and University of Toronto. The remaining authors have disclosed that they do not have any potential conflicts of interest.

The opinions, results, and conclusions reported in this article are those of the authors and are independent from the funding sources.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s website (http://journals.lww.com/ccejournal).

REFERENCES

- 1.Bellani G, Laffey JG, Pham T, et al. ; LUNG SAFE Investigators: Epidemiology, patterns of care, and mortality for patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome in intensive care units in 50 countries. JAMA 2016; 315:788–800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ranieri VM, Rubenfeld GD, Thompson BT, et al. ; ARDS Definition Task Force: Acute respiratory distress syndrome. JAMA 2012; 307:2526–2533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Herridge MS, Tansey CM, Matté A, et al. ; Canadian Critical Care Trials Group: Functional disability 5 years after acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 2011; 364:1293–1304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cuthbertson BH, Roughton S, Jenkinson D, et al. : Quality of life in the five years after intensive care: A cohort study. Crit Care 2010; 14:R6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cook T, Woodall N, Frerk C: The NAP4 Report: Major Complications of Airway Management in the UK. London, United Kingdom, Royal College of Anaesthetists, 2011. Available at: https://www.rcoa.ac.uk/research/research-projects/national-audit-projects-naps/nap4-major-complications-airway-management. Accessed May 22, 2024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Russotto V, Myatra SN, Laffey JG, et al. ; INTUBE Study Investigators: Intubation practices and adverse peri-intubation events in critically ill patients from 29 countries. JAMA 2021; 325:1164–1172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Devlin JW, Skrobik Y, Gélinas C, et al. : Clinical practice guidelines for the prevention and management of pain, agitation/sedation, delirium, immobility, and sleep disruption in adult patients in the ICU. Crit Care Med 2018; 46:e825–e873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Papazian L, Klompas M, Luyt CE: Ventilator-associated pneumonia in adults: A narrative review. Intensive Care Med 2020; 46:888–906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vanhorebeek I, Latronico N, Van den Berghe G: ICU-acquired weakness. Intensive Care Med 2020; 46:637–653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hakim R, Watanabe-Tejada L, Sukhal S, et al. : Acute respiratory failure in randomized trials of noninvasive respiratory support: A systematic review of definitions, patient characteristics, and criteria for intubation. J Crit Care 2020; 57:141–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bellani G, Laffey JG, Pham T, et al. ; LUNG SAFE Investigators: Noninvasive ventilation of patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome: Insights from the LUNG SAFE Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2017; 195:67–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yarnell CJ, Angriman F, Ferreyro BL, et al. : Oxygenation thresholds for invasive ventilation in hypoxemic respiratory failure: A target trial emulation in two cohorts. Crit Care 2023; 27:67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Noseworthy TW, Konopad E, Shustack A, et al. : Cost accounting of adult intensive care: Methods and human and capital inputs. Crit Care Med 1996; 24:1168–1172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Understanding costs and cost-effectiveness in critical care: Report from the second American Thoracic Society workshop on outcomes research. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002; 165:540–550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Byrick RJ, Mindorff C, McKEE L, et al. : Cost-effectiveness of intensive care for respiratory failure patients. Crit Care Med 1980; 8:332–337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Soares MO, Welton NJ, Harrison DA, et al. : An evaluation of the feasibility, cost and value of information of a multicentre randomised controlled trial of intravenous immunoglobulin for sepsis (severe sepsis and septic shock): Incorporating a systematic review, meta-analysis and value of information analysis. Health Technol Assess 2012; 16:1–186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guideline Working Group. Guidelines for the Economic Evaluation of Health Technologies: Canada. Fourth Edition. Ottawa, ON, Canada, Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health, 2017. Available at: https://www.cadth.ca/guidelines-economic-evaluation-health-technologies-canada-4th-edition. Accessed May 22, 2024 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Husereau D, Drummond M, Augustovski F, et al. ; CHEERS 2022 ISPOR Good Research Practices Task Force: Consolidated health economic evaluation reporting standards 2022 (CHEERS 2022) statement: Updated reporting guidance for health economic evaluations. BMC Med 2022; 20:23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sanders GD, Neumann PJ, Basu A, et al. : Recommendations for conduct, methodological practices, and reporting of cost-effectiveness analyses: Second panel on cost-effectiveness in health and medicine. JAMA 2016; 316:1093–1103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goldberger AL, Amaral LA, Glass L, et al. : PhysioBank, PhysioToolkit, PhysioNet: Components of a new research resource for complex physiologic signals. Circulation 2000; 101:E215–E220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnson AEW, Bulgarelli L, Shen L, et al. : MIMIC-IV, a freely accessible electronic health record dataset. Sci Data 2023; 10:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grasselli G, Zangrillo A, Zanella A, et al. ; COVID-19 Lombardy ICU Network: Baseline characteristics and outcomes of 1591 patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 admitted to ICUs of the Lombardy Region, Italy. JAMA 2020; 323:1574–1581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Richardson S, Hirsch JS, Narasimhan M, et al. ; the Northwell COVID-19 Research Consortium: Presenting characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes among 5700 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the New York City Area. JAMA 2020; 323:2052–2059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. : Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 2020; 395:497–506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bertram MY, Lauer JA, Stenberg K, et al. : Methods for the economic evaluation of health care interventions for priority setting in the health system: An update from WHO CHOICE. Int J Health Policy Manage 2021; 10:673–677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Evans J, Kobewka D, Thavorn K, et al. : The impact of reducing intensive care unit length of stay on hospital costs: Evidence from a tertiary care hospital in Canada. Can J Anaesth 2018; 65:627–635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaier K, Heister T, Wolff J, et al. : Mechanical ventilation and the daily cost of ICU care. BMC Health Serv Res 2020; 20:267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tan SS, Hakkaart-van Roijen L, Al MJ, et al. : A microcosting study of intensive care unit stay in the Netherlands. J Intensive Care Med 2008; 23:250–257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Canadian Institute for Health Information: Care in Canadian ICUs. 2016. Available at: https://secure.cihi.ca/estore/productSeries.htm?pc=PCC1475. Accessed May 22, 2024

- 30.Dasta JF, McLaughlin TP, Mody SH, et al. : Daily cost of an intensive care unit day: The contribution of mechanical ventilation. Crit Care Med 2005; 33:1266–1271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kristinsdottir EA, Long TE, Sigvaldason K, et al. : Long-term survival after intensive care: A retrospective cohort study. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2020; 64:75–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hill AD, Fowler RA, Burns KEA, et al. : Long-term outcomes and health care utilization after prolonged mechanical ventilation. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2017; 14:355–362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Khandelwal N, Hough CL, Bansal A, et al. : Long-term survival in patients with severe acute respiratory distress syndrome and rescue therapies for refractory hypoxemia. Crit Care Med 2014; 42:1610–1618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thompson K, Taylor C, Jan S, et al. : Health-related outcomes of critically ill patients with and without sepsis. Intensive Care Med 2018; 44:1249–1257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Steenbergen S, Rijkenberg S, Adonis T, et al. : Long-term treated intensive care patients outcomes: The one-year mortality rate, quality of life, health care use and long-term complications as reported by general practitioners. BMC Anesthesiol 2015; 15:142–142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Williams TA, Dobb GJ, Finn JC, et al. : Determinants of long-term survival after intensive care. Crit Care Med 2008; 36:1523–1530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sprooten RTM, Rohde GGU, Janssen MTHF, et al. : Predictors for long-term mortality in COPD patients requiring non-invasive positive pressure ventilation for the treatment of acute respiratory failure. Clin Respir J 2020; 14:1144–1152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Meynaar IA, Van Den Boogaard M, Tangkau PL, et al. : Long-term survival after ICU treatment. Minerva Anestesiol 2012; 78:1324–1332 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Herridge MS, Chu LM, Matte A, et al. ; RECOVER Program Investigators (Phase 1: towards RECOVER): The RECOVER program: Disability risk groups and 1-year outcome after 7 or more days of mechanical ventilation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2016; 194:831–844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wodchis WP, Austin PC, Henry DA: A 3-year study of high-cost users of health care. CMAJ 2016; 188:182–188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.R Core Team: R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2020. Available at: https://www.r-project.org. Accessed May 22, 2024 [Google Scholar]

- 42.TreeAge Software: TreeAge Pro. Williamstown MA, TreeAge Software, 2021. Available at: http://www.treeage.com. Accessed May 22, 2024 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fenwick E, Steuten L, Knies S, et al. : Value of information analysis for research decisions—an introduction: Report 1 of the ISPOR value of information analysis emerging good practices task force. Value Health 2020; 23:139–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Krishnan JK, Rajan M, Baer BR, et al. : Assessing mortality differences across acute respiratory failure management strategies in Covid-19. J Crit Care 2022; 70:154045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Moore TJ, Heyward J, Anderson G, et al. : Variation in the estimated costs of pivotal clinical benefit trials supporting the US approval of new therapeutic agents, 2015–2017: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2020; 10:e038863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Baston CM, Coe NB, Guerin C, et al. : The cost-effectiveness of interventions to increase utilization of prone positioning for severe acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med 2019; 47:e198–e205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Koffijberg H, Rothery C, Chalkidou K, et al. : Value of information choices that influence estimates: A systematic review of prevailing considerations. Med Decis Making 2018; 38:888–900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jackson CH, Baio G, Heath A, et al. : Value of information analysis in models to inform health policy. Annu Rev Stat Appl 2022; 9:95–118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Heath A, Myriam Hunink MG, Krijkamp E, et al. : Prioritisation and design of clinical trials. Eur J Epidemiol 2021; 36:1111–1121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Silberzahn R, Uhlmann EL, Martin DP, et al. : Many analysts, one data set: Making transparent how variations in analytic choices affect results. Adv Methods Pract Psychol Sci 2018; 1:337–356 [Google Scholar]

- 51.Eaton Turner E, Jenks M: Cost-effectiveness analysis of the use of high-flow oxygen through nasal cannula in intensive care units in NHS England. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res 2018; 18:331–337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.