Abstract

Objective:

To develop a desirability of outcome ranking (DOOR) scale for use in children with septic shock and determine its correlation with a decrease in 3-month post-admission health-related quality of life (HRQL) or death.

Design:

Secondary analysis of the Life After Pediatric Sepsis Evaluation prospective study.

Setting:

12 U.S. pediatric intensive care units (PICUs), 2013 to 2017.

Patients:

Children (1 month – 18 years) with septic shock.

Interventions:

None.

Measurements and Main Results:

We applied a 7-point pediatric critical care (PCC) DOOR scale: 7:death; 6:extracorporeal life support; 5:supported by life-sustaining therapies (continuous renal replacement therapy, vasoactives, or invasive ventilation); 4:hospitalized with or 3:without organ dysfunction; 2:discharged with or 1:without new morbidity to patients by assigning the highest applicable score on specific days post-PICU admission. We analyzed Spearman rank order correlations [95% confidence intervals] between proximal outcomes (PCC-DOOR scale on days 7, 14 and 21, ventilator-free days, cumulative 28-day Pediatric Logistic Organ Dysfunction-2 (PELOD-2) scores, and PICU-free days) and 3-month decrease in HRQL or death. HRQL was measured by PedsQL™ or FSII-R for patients with developmental delay. Patients who died were assigned the worst possible HRQL score. PCC-DOOR scores were applied to 385 patients, median age 6 years (IQR 2, 13) and 177 (46%) with a complex chronic condition(s). Three-month outcomes were available for 245 (64%) patients and 42 (17%) patients died. PCC-DOOR scale on days 7, 14 and 21 demonstrated fair correlation with the primary outcome (−0.42 [−0.52, −0.31], (−0.47 [−0.56, −0.36]) and −0.52 [−0.61, −0.42]), similar to the correlations for cumulative 28-day PELOD-2 scores (−0.51 [−0.59, −0.41], ventilator-free days (0.43 [0.32, 0.53]) and PICU-free days (0.46 [0.35, 0.55]).

Conclusions:

The PCC-DOOR scale is a feasible, practical outcome for pediatric sepsis trials and demonstrates fair correlation with decrease in HRQL or death at 3 months.

MeSH Terms: Health-Related Quality of Life, Pediatric Intensive Care Unit, Septic Shock, Outcome Measures, Critical Care Outcomes

Introduction

As pediatric sepsis survivorship has increased, clinical trial endpoints must evolve to include measures of morbidity and long-term health and functioning (1–4). Clinician and family stakeholders in pediatric critical care recommend prioritizing investigational outcomes of global domains of health, including a child’s health-related quality of life (HRQL) (5). Prior studies of critically ill sepsis survivors have shown increased rates of medical technology use and comorbidities following PICU admission (6, 7), increased measures of disability after discharge (8), worsened neuro-developmental outcomes (9) and negative family impacts (10). Few pediatric critical care trials use longitudinal patient-reported outcomes. In-hospital outcome measures are commonly used, which provide results efficiently and allow for trial adaptation. An in-hospital outcome measure that yields robust clinical information and is associated with long-term outcomes, such as HRQL, would be highly valuable for future pediatric critical care trials.

Ordinal scale outcome measures are increasingly used in trials of hospitalized and critically ill adults (11–13), including the World health Organization Clinical Progression Scale for COVID-19 therapies (14). Ordinal scale outcome measures include defined categories based on clinical outcomes and are evaluated on a predetermined study day. A specific ordinal scale framework is the Desirability of Outcome Ranking (DOOR) scale, which assigns clinical outcomes by rank order (15). These scales have not yet been adopted as pediatric critical care endpoints in clinical trials. A novel pediatric critical care ordinal scale, the Modified Clinical Progression Scale for Pediatric Patients, has been recently investigated in a cohort of patients with acute pediatric respiratory failure, but its association with long-term outcomes was not measured (16). Additional ordinal scales have been used to evaluate interventions in children for multisystem inflammatory syndrome, community-acquired pneumonia, and influenza (17–19).

Given increasing adaptation of DOOR scales for critical care, we developed a novel PCC-DOOR scale for pediatric sepsis and evaluated its use in a secondary analysis of the Life After Sepsis Evaluation (LAPSE) study. We evaluated the PCC-DOOR scale in this cohort of critically ill pediatric sepsis patients and determined its association with decreased 3-month HRQL or death. We hypothesized that a worse rank on the PCC-DOOR scale would correlate with worsened 3-month HRQL relative to baseline or death.

Materials and Methods

This is a secondary analysis of the LAPSE investigation, a prospective cohort study conducted across 12 U.S. pediatric intensive care units (PICUs) between 2013–2017. Full details of the LAPSE protocol were previously published (20–22). Institutional Review Board approval was granted centrally or by each site (Supplemental Digital Content [SDC] eText 1). IRB approval according to the ethical standards of the Helskinki Declaration of 1975 was obtained prior to patient enrollment. Informed consent was obtained from parents/guardians and, when appropriate, patient assent was obtained.

The study enrolled PICU patients (1 month – 18 years) with community acquired septic shock, defined as having documented or suspected infection with onset less than 48 hours prior to hospital admission, at least 2 systemic inflammatory response syndrome criteria (required to have either abnormal leukocyte count and/or differential or abnormal body temperature), need for invasive or non-invasive mechanical ventilation and vasoactive-inotropic support within 72 hours of hospitalization or 48 hours of PICU admission. Sepsis care was dictated by the clinical teams.

The PCC-DOOR scale (Figure 1) was developed based on the WHO COVID-19 Clinical Progression Scale (14). Initial development was performed via a focus group interview with pediatric critical care investigators at the University of Colorado. An initial version was evaluated in a small, single-center cohort (23). Subsequently, the PCC-DOOR scale categories underwent revision based on survey input from the Pediatric Acute Lung Injury and Sepsis Investigator Network’s POST-PICU Investigators Leadership Committee (24). The ordinal scale levels were determined to be distinct and represent worsening status with increasing PCC-DOOR categories for a sepsis population. Patients were categorized to the highest applicable PCC-DOOR ranking on each study day while the patient remained in the PICU, truncated at 28 calendar days. Day 0 represented the day of PICU admission.

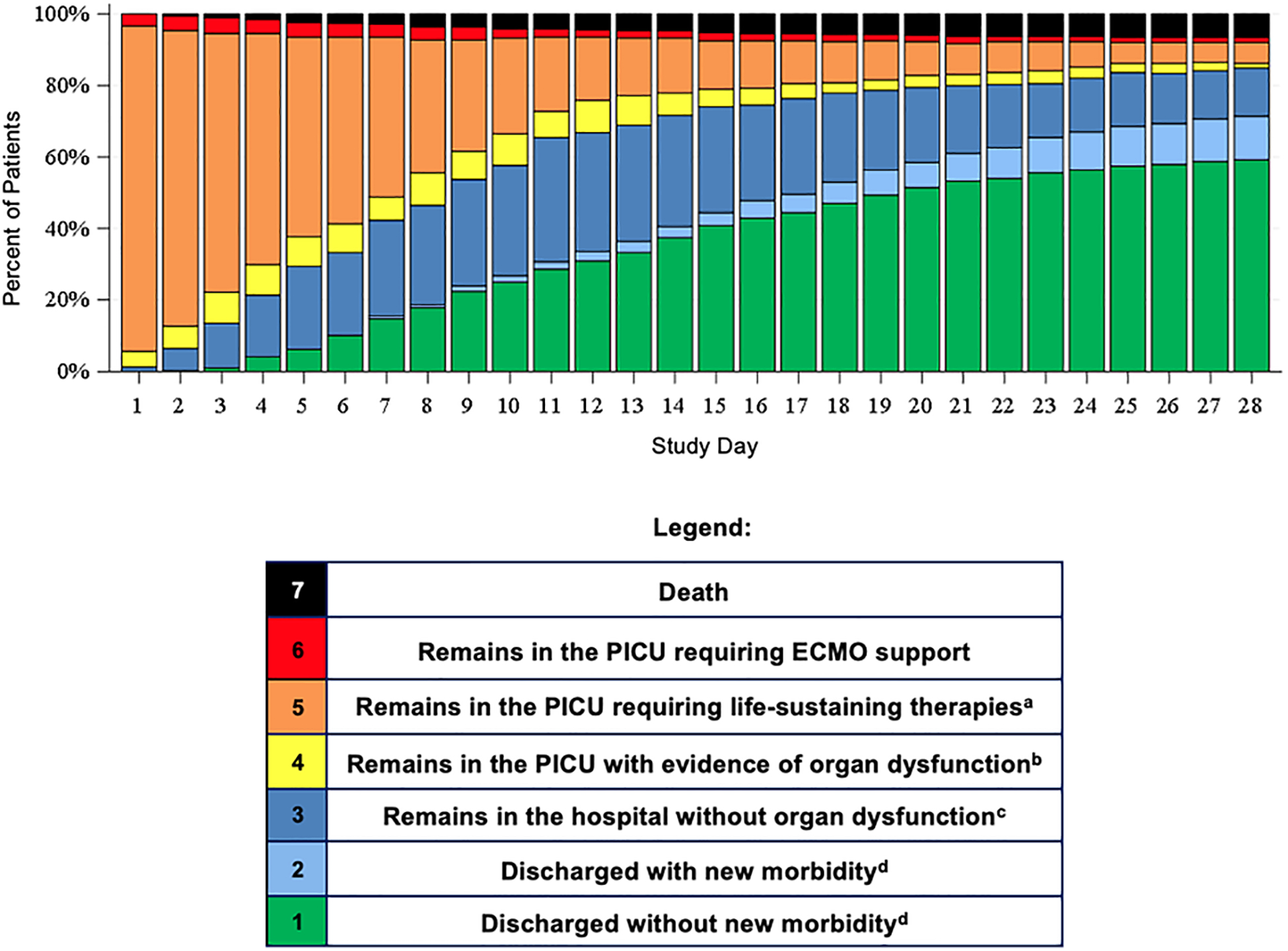

Figure 1.

Pediatric Critical Care Desirability of Outcome Ranking (PCC-DOOR) scale distribution during post-PICU admission days 1 through 28.

aLife-sustaining therapies were defined as receipt of invasive mechanical ventilation, vasoactive support, and/or continuous renal replacement therapy.

bOrgan dysfunction was defined by a Pediatric Logistic Organ Dysfuction-2 (PELOD-2) score of ≥ 2.

c”Remains in this hospital without organ dysfunction” was defined as patients who were either in the PICU with a PELOD-2 score of < 2 or had been transferred out of the PICU with the assumption they had achieved resolution of significant organ dysfunction.

dNew morbidity was defined by the Functional Status Scale (FSS) score at discharge relative to pre-admission baseline as having an increase of ≥ 3 points in the total FSS score or an increase of ≥ 2 points in a domain-specific score.

The primary outcome was a mixed continuous composite outcome of death or patient’s 3-month HRQL scores relative to their pre-illness baseline values. Pre-illness baseline was defined by HRQL assessed at PICU admission, reflecting HRQL during the 1-month prior to enrollment. HRQL was measured using the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory 4.0 (PedsQL™), or, when caregivers identified their child as having severe physical or developmental impairments at baseline, the Stein Jessop Functional Status II-R (FSII-R) scale (25, 26, SDC eText 2). Both scores were normalized on a 0 to 100 scale with higher scores representing better HRQL. Study results were interpreted using the minimal clinically important difference (MCID) for the PedsQL™ measure, which is a change of 4.5 points (26). The same MCID was applied to FSII-R measurements, though this MCID has not been validated for the FSII-R instrument. The same measure of HRQL was collected at admission, at PICU day 7 and at 1-, 3-, 6-, and 12-months after admission. Data were collected by parent-guardian interview locally at each site during the inpatient stay and remotely by the Seattle Children’s Research Institute after discharge.

Variable Definitions

Patients were categorized using the Pediatric Medical Complexity Algorithm (PMCA) as having no pre-existing chronic condition(s), non-complex chronic condition(s), or complex chronic condition(s), using ICD codes in the 3 years prior to and during admission (27). Baseline functional status was determined by the Functional Status Scale (FSS) score at hospital discharge (28) (SDC, eText 3). Severity of illness was measured by the Pediatric Risk of Mortality (PRISM)-III score (assessed within a 6-hour window at ICU admission) and by the Pediatric Logistic Organ Dysfunction-2 (PELOD-2) Score (29, 30, SDC, eText 4). Immunodeficiency states (SDC, eText 5) were identified at or during PICU admission. Neurologic insult was collected during the PICU admission, according to the primary LAPSE protocol. Cumulative 28-day PELOD-2 score is the summation of daily PELOD-2 scores of the patient while in the PICU, truncated at day 28. The worst daily PELOD-2 score possible is 33; consequently, the worst cumulative 28-day PELOD score possible is 924. Patients who died on or before study day 28 were assigned a score of 924.

Statistical Analysis

To identify the day with the broadest distribution of patients across the scale, we evaluated the standard deviation of the cohort’s PCC-DOOR scale level on post-admission days 1 to 28. We planned a priori to use the PCC-DOOR scale applied on 3 separate post-admission days (7, 14, 21), and on the day with the broadest patient distribution across the scale for the planned analysis. To investigate potential monotonic relationships between PCC-DOOR and worsened HRQL relative to pre-illness baseline at 3-months post-PICU admission, or death, we calculated Spearman rank order correlation coefficients and 95% confidence intervals. Patients who died on or before the 3-month follow-up period were assigned the worst possible HRQL score. We also tested for correlations between commonly used hospitalization outcomes including ventilator-free days, cumulative 28-day PELOD-2 score, and PICU-free days and the primary outcome. Correlations were calculated for the entire cohort and separately based on type of HRQL measurement (PedsQL™ or FSII-R). We also evaluated the correlation between the PCC-DOOR score on the pre-specified days and 3-month HRQL amongst survivors only. All analyses were performed using SAS v9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

The LAPSE study enrolled 389 patients including 4 of whom withdrew from the study, leaving 385 who are included in this analysis (SDC, eFigure 1). Patients were predominantly male (n=209; 54%), median age 6 years (IQR 2, 13), 68 (18%) were immunocompromised, and 177 (46%) had a complex chronic condition(s). Baseline functional status was normal in 217 (56%) patients and severely abnormal in 42 (11%) patients (Table 1). There was a median of 18 (IQR 9, 22) PICU-free days, and a median hospital length of stay of 16 days (IQR 9, 26). Of the cohort, 29 (8%) patients died prior to PICU discharge, and an additional 5 patients (1%) died prior to hospital discharge. Three-month outcome data were available for 245 (64%) patients including 203 (53%) with 3-month HRQL assessments (122 [60%] evaluated by PedsQL™ and 81 [40%] by FSII-R) and 42/385 (11%) patients who died before the 3-month evaluation. Patients with follow-up data more frequently had household income >$100,000 as compared to those patients with missing data (20% vs. 11%). A greater proportion of patients with follow-up data were diagnosed with complex chronic conditions (51% vs. 37%) and anoxic-ischemic injury (9% vs. 3%); as well as a greater proportion requiring cardiopulmonary resuscitation (12% vs. 5%) (SDC, eTable 1).

Table 1.

Patient demographics and clinical characteristics

| Patient and Clinical Course Characteristics | Cohort (n = 385) |

|---|---|

| Demographics | |

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 6 (2, 13) |

| Female, n (%) | 176 (46%) |

| Medicaid Insurance, n (%) | 194 (50%) |

| PMCA Category, n (%) | |

| Non-complex | 20 (5%) |

| Complex chronic conditions | 177 (46%) |

| Immunocompromised, n (%) | 68 (18%) |

| Baseline Functional Status Scale | |

| Good (6 – 7) | 219 (54%) |

| Mildly abnormal (8 – 9) | 36 (9%) |

| Moderately abnormal (10 – 15) | 85 (22%) |

| Severely abnormal (16 – 21) | 42 (11%) |

| Very severely abnormal (≥22) | 7 (2%) |

| Baseline Health Related Quality of Life a | |

| PedsQL™, median (IQR), n = 221 | 78 (66, 92) |

| FSII-R, median (IQR), n = 136 | 71 (61, 83) |

| Illness Indices | |

| Admission PRISM III percent risk of mortality, median (IQR) | 11 (6, 17) |

| Cumulative 28-day PELOD-2 scoreb, median (IQR) | 50 [25, 92] |

| Clinical Characteristics | |

| Infectious disease status, n (%) | |

| Documented | 163 (42%) |

| Suspected | 222 (58%) |

| Ventilator-free days, median days (IQR) | 20 [12, 23] |

| Continuous renal replacement therapy, n (%) | |

| Duration of CRRT, median days (IQR) | |

| Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, n (%) | |

| Duration of ECMO, median days (IQR) | |

| Neurologic insult(s) during PICU stay, n (%) | 167 (43%) |

| Cardiopulmonary resuscitation | 36 (9%) |

| PICU-free days, median days (IQR) | 18 [9, 22] |

| Hospital length of stay, median days (IQR) | 16 (9, 26) |

PedsQL™ and FSII-R instruments are scored from 0 to 100, where a higher score indicates better HRQL.

Cumulative 28-day PELOD-2 score is the summation of daily PELOD scores on study days 1–28 inclusive. The worst daily PELOD score is 33; consequently, the worst cumulative score is 924. Patients who died on or before study day 28 were assigned a score of 924.

IQR: Interquartile Range; PMCA: Pediatric Medical Complexity Algorithm; PRISM III: Pediatric Risk of Mortality III; PELOD-2: Pediatric Logistic Organ Dysfunction-2; PICU Pediatric Intensive Care Unit

PCC-DOOR Scale Distribution

We evaluated the distribution of the 385 patients in the study cohort across the 7-category PCC-DOOR scale (Figure 1 and SDC, eTable 2). Day 21 post-admission demonstrated the highest standard deviation of patient distribution across the DOOR categories. Baseline characteristics by PCC-DOOR category on day 21 are listed in SDC, eTable 3.

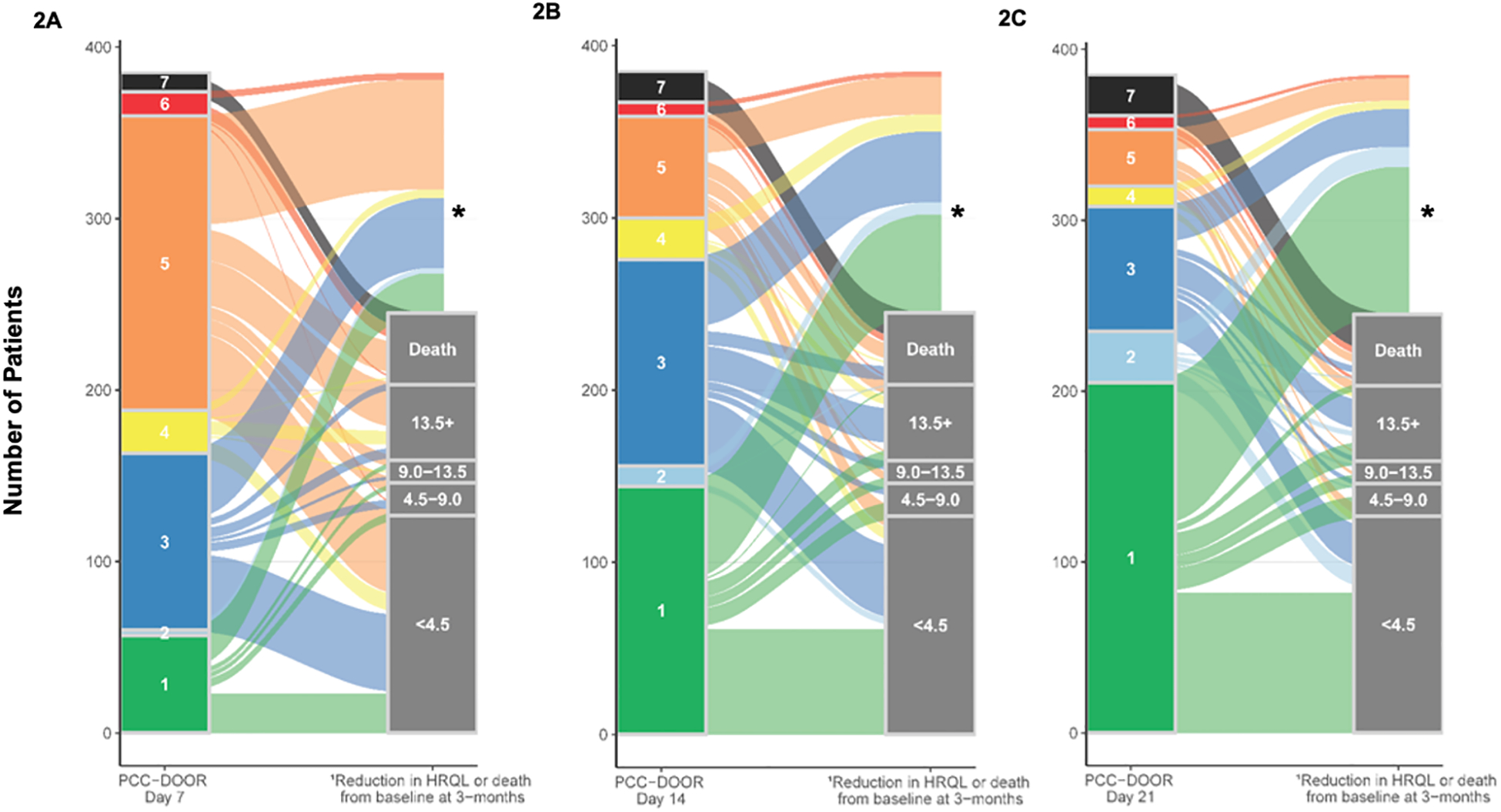

On day 7 post-admission, 60/385 (15%) patients were categorized as discharged from the hospital (PCC-DOOR scale scores 1 and 2), 103/385 (27%) patients as a score of 3, 211/385 (55%) as a score of 4 to 6, and 11/385 (3%) with a score of 7 (death). Of those 314 patients surviving on post-admission day 7 with a PCC-DOOR score ≥ 3, 169/314 (54%) patients survived to 3 months with available HRQL data and 65/169 (38%) had a ≥4.5 point decline in HRQL. This includes 51/169 (30%) with a >9 point decline in HRQL (Figure 2A). In comparison, of those 60 patients with a PCC-DOOR score 1 or 2 on day 7, 34/60 (57%) had 3-month HRQL data available, with 16/34 (47%) showing a decline in HRQL from baseline. Of those patients, 11/34 (32%) had ≥4.5 point decline from baseline. Of the 60 patients who were discharged by day 7, none died by 3 months compared to 42/314 (13%) of patients who were alive on day 7 with a PCC-DOOR score ≥3. Proportions of HRQL decrease from baseline at 3 months are noted separately by HRQL instrument (PedsQL™ or FSII-R) in the SDC, eFigures 4 – 6.

Figure 2A, 2B and 2C.

Three-month outcome of decreased health-related quality of life (HRQL) measured by combined PedsQL™ and FS-IIR or death by PCC-DOOR categories on day 7 (2A), day 14 (2B) and day 21 (2C) as represented by alluvial plots.

1HRQL categories are scaled according to MCID (4.5- point increments).

2Additional description of the PCC-DOOR scale components is listed in Figure 1.

* Surviving patients without assignment to a 3-month outcome were lost to follow-up or had insufficient data to calculate PedsQL™ or FS-IIR.

On day 14 post-admission, 156/385 (41%) patients were categorized as PCC-DOOR scale score 1 or 2, 120/385 (31%) patients had a score of 3, 91/385 (24%) had scores of 4 to 6, and 18 (5%) had a score of 7. Of those 211 patients with PCC-DOOR score ≥ 3 and alive on day 14, 113/211 (54%) survived to 3 months and had available HRQL data. Of those patients, 57/113 (50%) had decline in HRQL from baseline, with 51/113 (45%) patients having ≥4.5 point decline, including 42/113 (37%) with ≥9.0 point decline (Figure 2B).

On post-admission day 21, 235/385 (61%) patients were categorized by PCC-DOOR scale scores 1 or 2, 73/385 (19%) patients were categorized as a score of 3, 53/385 (14%) were categorized as scores 4 to 6, and 24/385 (6%) had died. Of those 126 patients with a PCC-DOOR score ≥ 3 and alive on day 21, 71/126 (56%) of patients survived to 3 months and had available HRQL data. Of those patients, 37/71 (52%) had a ≥4.5 point decline in HRQL from baseline, including 32/71 (45%) with ≥9.0 point decline from baseline (Figure 2C). Of the 235 patients with a PCC-DOOR score <3 on day 21, 132/235 (65%) patients survived to 3 months and had available HRQL data. Of those patients 39/132 (30%) had a ≥4.5 point decline in HRQL from baseline, including 25/132 (19%) with ≥9.0 point decline.

PCC-DOOR Scale Correlations with Primary Outcome

Higher PCC-DOOR scale categories on days 7, 14 and 21 correlated with having a decline from baseline in HRQL at 3-months or death (Table 2). Application of the PCC-DOOR scale on days 7, 14 and 21 had fair correlations with the composite 3-month outcome of death or worsened 3-month HRQL (−0.42 [−0.52, −0.31], (−0.47 [−0.56, −0.36]) and −0.52 [−0.61, −0.42], respectively) (31). These correlations were similar to those analyzed between 28-day cumulative PELOD-2 (−0.51 [−0.59, −0.41]), ventilator-free days (0.43 [0.32, 0.53]), PICU-free days (0.46 [0.35, 0.55]) and 3-month change in HRQL or death. These relationships were consistent when tested separately by PedsQL™ or FSII-R instrument. Limiting the analysis to survivors only, the correlation between days 7, 14 and 21 PCC-DOOR scores and change in 3-month HRQL was lower but remained inversely correlated (−0.21 [−0.33, −0.07], −0.22 [−0.34, −0.08] and −0.28 [−0.40, −0.14], respectively).

Table 2.

Correlation between in-hospital outcomes and change in HRQL or death at 3 months using Spearman rank order correlation coefficients.

| Proximal or In-hospital outcome | 3-month HRQL or Death | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| PedsQL™ and FS-IIR | PedsQL™ | FS-IIR | |

| PCC-DOOR Scale | |||

| Day 7 | −0.42 (−0.52, −0.31) | −0.47 (−0.58, −0.34) | −0.56 (−0.67, −0.43) |

| Day 14 | −0.47 (−0.56, −0.36) | −0.54 (−0.64, −0.42) | −0.62 (−0.72, −0.49) |

| Day 21a | −0.52 (−0.61, −0.42) | −0.60 (−0.69, −0.49) | −0.66 (−0.75, −0.55) |

| Cumulative 28-day PELOD-2 | −0.51 (−0.59, −0.41) | −0.59 (−0.68, −0.48) | −0.64 (−0.73, −0.52) |

| Ventilator-free days | 0.43 (0.32, 0.53) | 0.52 (0.40, 0.62) | 0.55 (0.41, 0.66) |

| PICU-free days | 0.46 (0.35, 0.55) | 0.55 (0.43, 0.65) | 0.57 (0.43, 0.68) |

Day 21 had the highest standard deviation for distribution of the cohort across the PCC-DOOR scale.

FS-IIR: Functional Status-IIR; HRQL: health-related quality of life; PELOD-2: Pediatric Logistic Organ Dysfunction Score-2; PCC-DOOR: Pediatric Critical Care-Desirability of Outcome Ranking; PICU: Pediatric Intensive Care Unit

Discussion

This study builds on previous work by the LAPSE investigators in establishing a novel composite primary outcome for pediatric septic shock and evaluating its correlation with long-term outcomes (32). The PCC-DOOR scale applied on days 7, 14 and 21 in this cohort demonstrated fair correlation with worsened 3-month HRQL or death (31), both of which are important outcomes for clinicians and patients/families (3). The correlation between the PCC-DOOR score and the primary outcome was similar when compared to commonly used in-hospital outcomes, suggesting that the PCC-DOOR scale is an acceptable proximal study endpoint. Our results demonstrated decreased strength of correlation when tested only in survivors, suggesting deaths had an important effect in this relationship. As demonstrated in this analysis, an ordinal scale outcome may be pertinent to pediatric sepsis survivorship given its association with HRQL.

An ordinal scale can also increase a study’s power relative to other statistical methods. When evaluated by proportional odds analysis, an ordinal scale can increase sample efficiency over other statistical design methods, such as time-to-event analysis or using binary outcomes (33). This is applicable to Bayesian adaptive designs as well as response adaptive randomization, which allow for modification of the study design during data collection to efficiently limit sample size and optimize power (34). In these analyses—which are based on real-time trial data collection—robust and timely availability of outcome data is required (35, 36). The PCC-DOOR scale may be a more feasible clinical trial endpoint as it requires data collection on discrete days (e.g., day 21) instead of daily assessment, such as cumulative 28-day PELOD, while demonstrating similar association with long-term outcomes.

Inclusion of death in composite clinical trial outcomes has been debated and approached using different techniques. In this analysis, death was quantified as the worst possible HRQL outcome, as is commonly done in composite outcomes that include death (37). We also assessed the correlation after excluding patients who died prior to the 3-month outcome assessment and found that the negative correlation persisted when DOOR was applied on days 7, 14 and 21. This finding suggests that the PCC-DOOR scale is relevant as a composite measure to evaluate death and the multiple outcomes between death and baseline health status.

This study has notable limitations including cohort attrition and lack of a validation cohort. Additionally, the HRQL outcome assessed combines two separate HRQL assessment instruments. The MCID reported for the combined cohort is not validated for use in the FSII-R scale. The PCC-DOOR scale may also be limited in patients with chronic organ failure support or technology use (e.g., chronic ventilation or tracheostomy) as acute on chronic organ dysfunction and its resolution may have different associations with long-term HRQL. In future work, for patients on chronic ventilator support, the pediatric acute respiratory distress syndrome criteria for higher respiratory support could be used to characterize life-sustaining therapies (38). We were unable to test this since our population did not include any patients on chronic ventilation. Additionally, the provision of life-supporting technologies included in the ordinal scale are not applicable across all settings, particularly where supportive technologies may not be available (e.g., low resource settings). Finally, the correlations between the proximal, in-hospital outcomes including the PCC-DOOR score and 3-month outcomes are fair. Ongoing investigations are necessary to identify in-hospital outcomes with strong correlations with long-term, patient- and family-centered outcomes. Future research should involve collaboration to standardize current clinical progression scales used in pediatric critical care medicine.

Conclusions

The PCC-DOOR scale is a useful endpoint that is associated with clinically meaningful, patient-centered post-discharge outcomes in a pediatric sepsis population. Further investigations are needed to better delineate the generalizability of this novel ordinal scale and reproducibility of the findings across sepsis cohorts and other outcome domains.

Supplementary Material

Research in Context.

Desirability of outcome ranking (DOOR) scales have shown increasing use in critical care clinical trials as primary endpoints.

This clinical investigation introduces a novel pediatric critical care desirability of outcome ranking scale (PCC-DOOR) for pediatric septic shock.

This secondary analysis of the Life After Sepsis Evaluation study aims to determine a correlation between the novel PCC-DOOR scale and post-discharge health-related quality of life or death in pediatric septic shock.

What this Study Means.

A novel pediatric critical care desirability of outcome ranking (PCC-DOOR) scale is feasible to apply to a large cohort of critically ill pediatric patients with septic shock.

This novel PCC-DOOR scale measured in-hospital correlates fairly with a decrease in 3-month health-related quality of life outcomes or death.

The PCC-DOOR scale provides similar comparison with a decrease in HRQL or death as with other commonly used in-hospital clinical markers (cumulative PELOD score, PICU-free days, ventilator-free days).

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the University of Colorado Pediatric Critical Care Clinical Research Investigators and the Pediatric Acute Lung Injury and Sepsis Investigator Network’s POST-PICU Investigators Leadership Committee: Mary Hartman, MD, MPH, Elizabeth Killien, MD, MPH, Alan Woodruff, MD, Erin Carlton, MD, Julia Heneghan, MD, Leslie Dervan, MD, Neethi Pinto, MD, MS, and R. Scott Watson, MD, MPH for their contributions to the development of the PCCM DOOR scale. Additionally, we would like to thank the original LAPSE collaborative for collecting data to construct the rich database that made the current investigation possible.

Conflicts of Interest and Sources of Funding:

Funding for the primary LAPSE investigation was provided by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R01HD073362 and cooperative agreements U10-HD050012, U10-HD050096, U10-HD063108, U10-HD049983 U10-HD049981, U10-HD063114, and U10-HD063106). Support was provided to Dr. Maddux by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (K23HD096018). For the remaining authors, no conflicts of interest were declared.

Copyright Form Disclosure:

Dr. Logan’s institution received funding from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (K23HD096018)(R01HD073362 and cooperative agreements U10-HD050012, U10-HD050096, U10-HD063108, U10-HD049983 U10-HD049981, U10-HD063114, and U10-HD063106). Drs. Logan, Banks, Reeder, Meert, Zimmerman, and Maddux received support for article research from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Drs. Banks, Bennett, and Zimmerman’s institutions received funding from the National Institute of Child Health and Development (NICHD). Dr. Banks disclosed government work. Drs. Reeder and Meert’s institutions received funding from the NIH. Dr. Bennett’s institution received funding from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Zimmerman’s institution received funding from Immunexpress; He received funding from Elsevier Publishing. Dr. Maddux’s institution received funding from the NICHD (K23 HD096018) and the Francis Family Foundation. The remaining authors have disclosed that they do not have any potential conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Site: 12 tertiary pediatric intensive care units including those comprising the Collaborative Pediatric Critical Care Research Network

References

- 1.Balamuth F, Weiss SL, Neuman MI, et al. : Pediatric severe sepsis in U.S. children’s hospitals. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2014; 15(9):798–805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hartman ME, Linde-Zwirble WT, Angus DC, et al. : Trends in the epidemiology of pediatric severe sepsis. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2013; 14(7):686–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Merritt C, Menon K, Agus MSD, et al. : Beyond Survival: Pediatric Critical Care Interventional Trial Outcome Measure Preferences of Families and Healthcare Professionals. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2018; 19(2):e105–e111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ruth A, McCracken CE, Fortenberry JD, et al. : Pediatric severe sepsis: current trends and outcomes from the Pediatric Health Information Systems database. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2014; 15(9):828–838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fink EL, Maddux AB, Pinto N, et al. : A Core Outcome Set for Pediatric Critical Care. Crit Care Med 2020; 48(12):1819–1828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carlton EF, Donnelly JP, Hensley MK, et al. : New Medical Device Acquisition During Pediatric Severe Sepsis Hospitalizations. Crit Care Med 2020; 48(5):725–731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carlton EF, Gebremariam A, Maddux AB, et al. : New and Progressive Medical Conditions After Pediatric Sepsis Hospitalization Requiring Critical Care. JAMA Pediatr 2022; 176(11):e223554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weiss SL, Fitzgerald JC, Pappachan J, et al. : Global epidemiology of pediatric severe sepsis: the sepsis prevalence, outcomes, and therapies study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2015; 191(10):1147–1157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Als LC, Nadel S, Cooper M, et al. : Neuropsychologic function three to six months following admission to the PICU with meningoencephalitis, sepsis, and other disorders: a prospective study of school-aged children. Crit Care Med 2013; 41(4):1094–1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clark JD, Kraft SA, Dervan LA, et al. : “I Didn’t Realize How Hard It Was Going to Be Just Transitioning Back into Life”: A Qualitative Exploration of Outcomes for Survivors of Pediatric Septic Shock. J Pediatr Intensive Care 2021; 10(1):1–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee N, Smith SW, Hui DSC, et al. : Development of an ordinal scale treatment endpoint for adults hospitalized with influenza. Clin Infect Dis 2021; 73(11):e4369–e4374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beigel JH, Tomashek KM, Dodd LE, et al. : Remdesivir for the treatment of Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2020; 383(19):1813–1826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Investigators Remap-Cap, 2021. Interleukin-6 receptor antagonists in critically ill patients with Covid-19. New England Journal of Medicine, 384(16), pp.1491–1502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Working Group on the Clinical Characterisation and Management of COVID-19 infection WHO: A minimal common outcome measure set for COVID-19 clinical research. Lancet Infect Dis 2020; 20(8):e192–e197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Evans SR, Rubin D, Follmann D, et al. : Desirability of Outcome Ranking (DOOR) and Response Adjusted for Duration of Antibiotic Risk (RADAR). Clin Infect Dis 2015; 61(5):800–806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leland SB, Staffa SJ, Newhams MM, et al. : The Modified Clinical Progression Scale for Pediatric Patients: Evaluation as a Severity Metric and Outcome Measure in Severe Acute Viral Respiratory Illness. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2023, Epublication ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beigel JH, Aga E, Elie-Turenne MC, et al. : Anti-influenza immune plasma for the treatment of patients with severe influenza A: a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet Respir Med 2019; 7(11):941–950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McArdle AJ, Vito O, Patel H, et al. : Treatment of Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children. N Engl J Med 2021; 385(1):11–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Williams DJ, Creech CB, Walter EB, et al. : Short- vs Standard-Course Outpatient Antibiotic Therapy for Community-Acquired Pneumonia in Children: The SCOUT-CAP randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr 2022; 176(3):253–261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Workman JK, Reeder RW, Banks RK, et al. : Change in Functional Status During Hospital Admission and Long-Term Health-Related Quality of Life Among Pediatric Septic Shock Survivors. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2023; 10.1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maddux AB, Zimmerman JJ, Banks RK, et al. : Health Resource Use in Survivors of Pediatric Septic Shock in the United States. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2022; 23(6):e277–e288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zimmerman JJ. Life After Pediatric Sepsis Evaluation (LAPSE) Dataset. Available at the NICHD Data and Specimen Hub: 10.57982/57zs-q947. Accessed January 3, 2023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Logan G, Miller K, Sierra Y, et al. : A Desirability of Outcome Ranking (DOOR) Scale: Development of a Novel Outcomes Scale for Pediatric Critical Illness. April 2022. Abstract 19.102, Pediatric Academic Society Meeting, Denver, CO. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Randolph AG, Bembea MM, Cheifetz IM et al. : Pediatric Acute Lung Injury and Sepsis Investigators (PALISI): Evolution of an Investigator-Initiated Research Network. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2022; 23:1056–1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stein RE, Jessop DJ. Functional status II®. A measure of child health status. Med Care 1990; 28(11):1041–1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Varni JW, Burwinkle TM, Seid M, et al. : The PedsQL 4.0 as a pediatric population health measure: feasibility, reliability, and validity. Ambul Pediatr 2003; 3(6):329–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Simon TD, Cawthon ML, Stanford S, et al. : Pediatric medical complexity algorithm: a new method to stratify children by medical complexity. Pediatrics 2014; 133(6):e1647–1654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pollack MM, Holubkov R, Glass P, et al. : Functional Status Scale: new pediatric outcome measure. Pediatrics 2009; 124(1):e18–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leteurtre S, Duhamel A, Salleron J, et al. : PELOD-2: an update of the PEdiatric logistic organ dysfunction score. Crit Care Med 2013; 41(7):1761–1773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pollack MM, Patel KM, Ruttimann UE. PRISM III: an updated Pediatric Risk of Mortality score. Crit Care Med 1996; 24(5):743–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Akoglu H U’er’s guide to correlation coefficients. Turk J Emerg Med 2018; 18(3):91–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zimmerman JJ, Banks R, Berg RA, et al. : Critical Illness Factors Associated With Long-Term Mortality and Health-Related Quality of Life Morbidity Following Community-Acquired Pediatric Septic Shock. Crit Care Med 2020; 48(3):319–328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peterson RL, Vock DM, Babiker A, et al. Comparison of an ordinal endpoint to time-to-event, longitudinal, and binary endpoints for use in evaluating treatments for severe influenza requiring hospitalization. Contemp Clin Trials Commun 2019; 15:100401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.VanBuren JM, Casper TC, Nishijima DK, et al. : The design of a Bayesian adaptive clinical trial of tranexamic acid in severely injured children. Trials 2021; 22(1):769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Faustino EVS, Raffini LJ, Hanson SJ, et al. : Age-dependent heterogeneity in the efficacy of prophylaxis with enoxaparin against catheter-associated thrombosis in critically ill children: a post hoc analysis of a Bayesian phase 2b randomized clinical trial. Crit Care Med 2021; 49(4):e369–e380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dean JM: Evolution of the Collaborative Pediatric Critical Care Research Network. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2022; 23:1049–1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Contentin L, Ehrmann S, Giraudeau B. Heterogeneity in the definition of mechanical ventilation duration and ventilator-free days. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2014; 189(8):998–1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Naidr Y, Smith L, Thomas NJ, et al. : Definition, Incidence, and Epidemiology of Pediatric Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome: From the Second Pediatric Acute Lung Injury Consensus Conference. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2023; 24(12 Suppl 2):S87–S98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.