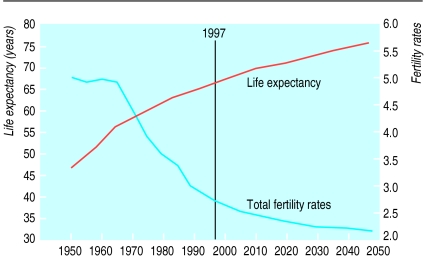

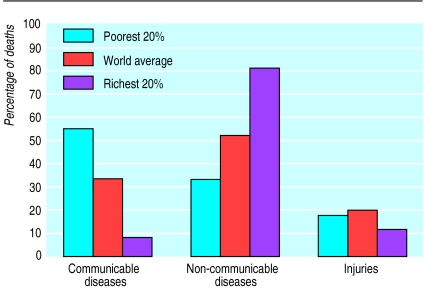

The World Bank estimates that 1.3 billion people live in absolute poverty, which means that about a quarter of the world’s population earns less than $1 a day. With the world’s population projected to almost double over the next century (from 5.3 billion in 1990 to around 10 billion by 2100, and mostly in poorer populations) malnutrition, childhood infections, poor maternal health, and high fertility will remain substantial challenges in real terms. Overall, however, the pattern of the global disease burden is shifting away from communicable diseases to non-communicable diseases as high fertility and mortality are being replaced by low fertility and mortality (fig 1). By 2020, the bank estimates that the share of the global disease burden from non-communicable diseases will be 57% (up from 36% in 1990), and the contribution from infectious diseases, pregnancy, and perinatal causes will have fallen to 22% (from 49% in 1990) (fig 2.)1

Summary points

A quarter of the world’s population earns less than $1 a day

The World Bank believes that governments need to find an “optimal balance” between public and private sectors in the financing and delivery of health care

The bank’s priorities focus on mobilising the female work force, enhancing the performance of healthcare systems, and ensuring sustainability of health care

However, it accepts that it needs to sharpen focus through greater selectivity, more rigorous evaluation of projects, and greater collaboration with governments and other agencies

Critics argue that the bank’s policies do not have the flexibility to achieve their goals

Figure 1.

Known and projected worldwide life expectancy and fertility rates

Figure 2.

Causes of death among rich and poor, worldwide

Despite the magnitude of the healthcare challenge, the bank believes that affordable solutions are available, but it blames governments and the private sector for rendering policies ineffective. The bank’s prescription for global health care is the marriage of public and private sectors, so that neither has too little or too much involvement. The bank warns that “in low and middle income countries, weak institutional capacity to deal effectively with regulatory problems in the private sector often causes governments to become excessively involved in the direct production of health services,”1 but it remains unclear exactly how responsibilities should be divided.

Waves of reform

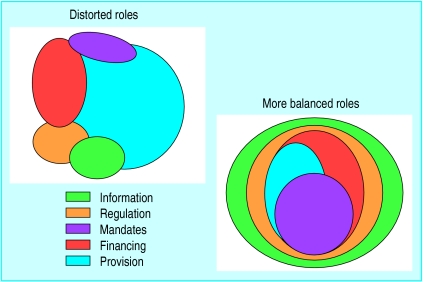

The bank explains that the “optimal balance” between public and private sectors depends on the country and is different for financing and for service delivery. “Strong, direct government intervention is needed in most countries to finance public health activities and essential health, nutrition, and reproductive services, as well as to provide protection against the impoverishing effects of catastrophic illness,” says the bank, which is convinced that succesful reform goes hand in hand with greater government input in information, regulations, and financing (fig 3). By devolving service delivery to non-governmental organisations, local communities, and the private sector, governments can, the bank believes, target their limited funds at preventive public health services, providing basic services to the poor, and overseeing medical education, research and development, and quality control.

Figure 3.

Government roles in the health, nutrition, and population sector

The bank advocates three “waves” of state reform. The first wave focuses on the privatisation of commercial enterprises; the second wave privatises public infrastructure and utilities; and the third wave continues with privatisation of state assests and utilises non-governmental and private management and investment in health, education, and pensions systems. The bank emphasises that these measures do not necessarily mean the sale of public assets, but that they encourage private co-financing and management. Paradoxically, the argument goes, governments end up having a greater role in the regulation of healthcare services. Though its health specialists might be eager to play down the bank’s support of the private sector, the latest annual report is less reserved: “One of the bank’s top priorities is to help stimulate the private sector. That’s because the private sector is the main source of economic growth—of jobs and higher incomes. The bank encourages the private sector by advocating stable economic policies, sound government finances, and open, honest, accountable, and consistent governance, and by offering guarantees.”2

One senior bank economist explained to me: “Policy based lending is where the bank really has power—I mean brute force. When countries really have their backs against the wall, they can be pushed into reforming things at a broad policy level that normally, in the context of projects, they can’t. The health sector can be caught up in this issue of conditionality.”

Health, nutrition, and population sector

The bank sees itself as a “knowledge” bank; a forum for the generation and dissemination of global knowledge. Beyond that, the health, nutrition, and population sector has three main priorities.

(1) To work with countries to improve the health, nutrition, and population outcomes of the world’s poor, and to protect the population from the impoverishing effects of illness, malnutrition, and high fertility.

To implement this objective, the bank aims to mobilise the female workforce by improving educational opportunities, improving childcare facilitites, and challenging society’s misconceptions about gender role. The ultimate aim is to reduce the fertility rate in low income countries and improve women’s health and their earning power. The “sector-wide” approach is proposed as a way of meeting economic objectives, and multisectoral policies that affect health, such as water supply and sanitation, are encouraged. As well as better coordination between government and other stakeholders, the bank also sees better internal coordination—between bank networks that are involved with alleviating poverty—as vital to the achievement of this priority.

(2) To work with countries to enhance the performance of healthcare systems by promoting equitable access and use of population based preventive and curative HNP services that are affordable, effective, well managed, of good quality, and responsive to client needs.

The bank is convinced that policies need to be moulded around existing healthcare systems. The role for government in a low income country where the private sector dominates healthcare provision might be to focus on preventive public health measures, provision of health care to the poor, and tighter regulation of the private sector; but in countries where the public sector dominates, governments should involve non-governmental organisations and the private sector in health service delivery. To achive this priority, the bank believes that it needs to liaise with ministries of finance, privatisation, and planning, as well as the ministry of health.

(3) To work with countries in securing sustainable healthcare financing by mobilising adequate levels of resources, establishing broad based risk pooling mechanisms, and maintaining effective control over public and private expenditure.

Working with ministries of finance and social security, the bank aims to achieve this priority by ensuring that governments target healthcare budgets at “effective and quality care that benefits those who need it most.” In low income countries, public resources should be enhanced by international aid and community based financing. For middle and higher income countries, taxation is seen as the key to sustaining health, nutrition, and population programmes.

Future strategies: sharpening focus

The bank’s strategy for the first decade of the new millennium is to achieve greater impact through “renewed commitment and focus.” The rapid expansion of its involvement in the health sector has blurred focus, the bank argues, blunting its impact and effectiveness. Several policy intitiatives have been proposed, and are being implemented, to rectify this.

Projects usually last five to eight years, but the bank’s HNP strategy has a “development timeframe” of 10 to 15 years. As well, bank staff and government officials will have changed several times during that period. The bank hopes to overcome this mismatch by setting, and achieving, medium term objectives for HNP strategies in specific countries, and by improving the rigour and evaluation of projects. What is needed, argues the HNP sector strategy, is “a reversal of recent cutbacks in sectoral analysis, an increase in the budget for HNP research in line with the HNP portfolio size, and a greater allocation of resources to help design and implement innovative projects.” The bank, however, is convinced that more effective indicators for health systems need to be developed, after consultation with other agencies and client countries, as the current indicators are too weak.

Selectivity is important—the bank doesn’t believe it can do everything well. By concentrating on the poorest countries, and on those that are receptive to its policies, the bank will practise greater selectivity in its lending programme. It is also keen to avoid duplicating services provided by the WHO and to emphasise the complementary relationship of the two organisations.

Another area that needs addressing is the quality of service offered to client countries. This can be enhanced by staying abreast of global developments and best practice in health, and by strengthening the bank’s knowledge base so that it can be a valuable resource for bank staff and those organisations that the bank works with. Further, the bank has developed more flexible lending mechanisms—Learning and Innovation Loans and Adaptable Program Loans were both introduced in 1997—and broader, sector-wide strategies. At the same time, lessons must be learnt from past and current projects, and the bank hopes that “projects that clearly fail to meet their development objectives will be restructured, or cancelled if they fail to improve after a reasonable time.”

Two other key areas are staffing and partnerships. The bank states that lending to the HNP sector has risen faster than staffing levels over recent years, and although the recent reorganisation should improve efficiency, adequate staffing remains a priority. But where should staff be located? The bank is keen on decentralisation and is sure that staff should be “closer to clients” rather than ensconced in Washington. Sometimes senior bank specialists are posted in client countries and oversee the work of health specialists hired locally, while a regional hub, such as the one in Budapest, can be the focal point for neighbouring resident missions.

Partners in health

The World Bank perceives that it has two levels of collaboration with the WHO—biomedical or technical advice from the WHO to improve projects at country level, and collaboration globally to improve worldwide understanding of health issues—and is eager to strengthen these links and those with clients, stakeholders, and other agencies.

The bank’s astuteness in recruiting staff from among its potential critics—such as the WHO and non-government organisations—both strengthens policies and dampens criticism. WHO staff are now frequently seconded to the bank, and although both sides are eager to create a symbiotic relationship, this is potentially problematic, especially bearing in mind the bank’s openness to private sector involvement in health care and the WHO’s traditional aversion to it. In addition, the WHO’s target of Health for All contrasts sharply with the bank’s more pragmatic adoption of disability adjusted life years (DALYs).

The Economist observed: “The WHO is behind the times.... Parts of the organisation seem to be stuck in a 1940s public-sector timewarp. They regard government as automatically good, profit automatically as evil, and intellectual property as theft. That sometimes makes collaboration with the private sector, particularly drug companies, a fraught affair. But the age of medicine as a pure public service is over.”3

Moreover, argues the Economist, while the WHO publicly welcomed DALYs, “privately many of its employees were scandalised by the idea of measuring the success or failure of a health policy by its economic consequences rather than by the ideologically pure goal of health for health’s sake.”

Richard Skolnik, the bank’s sector leader for south Asia, explains how he sees collaboration with the WHO: “There is a big interface, and it builds on a comparative advantage that we have. We are generally competent across a wide range of macroeconomic and technical matters but we are not specifically competent to deal with the highest level of technical inputs, but we have a lot of money. WHO has high levels of technical competence, generally in a narrow health framework, without much money. This sounds to me like a very good complementary situation.”

Charged with revitalising the WHO, Dr Gro Harlem Bruntland, who was elected director-general a year ago, cautiously strikes a similar chord: “We need to mobilise big partners like the World Bank.... Overall I think that cooperation with the World Bank will increase. The WHO can be actively involved, providing professional health backing to their work, if we feel confident there is mutual respect.”4 Over the past year the WHO and the World Bank have announced major initiatives on malaria, tobacco, and tuberculosis.

In 1998 the World Bank, the World Health Organisation, Unicef, and the United Nations Development Programme launched a campaign to “roll back malaria.” Each year there are 300-500 million acute cases of malaria; the four organisations aim to redirect strategy to implement a wide range of measures, such as the use of bed nets, computerised mapping of malaria cases, and development of new vaccines. In addition, the organisations aim to strengthen the health services provided to affected populations. Similarly, a new collaboration, the Stop TB Initiative, seeks to increase the coverage of the direct observation treatment, short course (DOTS), as only 16% of patients with tuberculosis worldwide receive treatment.

The bank’s ability to recruit leading health professionals and policymakers from governmental and non-governmental organisations, as well as economists, gives it an unsurmountable advantage over other agencies. In the past, some of the leading critics of bank policies have been non-government organisations, and even though they still watch the bank warily, criticism is harder to elicit. This is partly explained by the bank’s improved public relations and ostensibly more acceptable health policies. A more cynical explanation might be that the bank’s growing tendency to recruit workers from non-government organisations, and others, dampens criticism from these quarters.

“There are certainly more economists per square yard here than I’ve ever encountered,” says Maureen Law, former deputy minister of health and welfare in Canada and now a World Bank employee. “They were looking for people like me who were not economists and were from outside the bank, because of the expertise that we have and the commitment that we have to the health sector.”

For the bank’s partners in low income countries, implementing policies and projects is often difficult. Stephen Rudgard, director of development projects for CABI (formerly the Commonwealth Agricultural Bureau), an intergovernmental non-profit organisation, explains: “At the operational end, individual bank projects are formulated and executed by national implementing agencies in consultation with the bank’s task managers. This interchange greatly influences the nature of any potential “knowledge” component, and so projects vary widely in the extent of their focus on this area. The result is that large loan commitments to development of infrastructure often pay out millions of dollars for buildings, equipment, and information technology, but relatively trivial sums are allocated to acquisition or generation of content. It is down to a few individuals to determine the extent of this part of the agenda, and the bank’s stated policies are interpreted differently by individuals.”

Conclusion

In the first decade of the 21st century, the World Bank sees itself enhancing its role in improving human development by influencing the global health policy debate and strengthening partnerships. The bank has a prescription for health systems that it claims is adaptable, but critics argue that its policies vary little from country to country and are driven by economic outcomes. Decentralisation, partnerships, achieving sustainability, and better evaluations are key factors in the bank’s attempt to sharpen its focus; initiatives that have largely been welcomed. The bank seems to be winning over some of its natural critics, but others remain unconvinced of the efficacy of its policies. The next article discusses bank policies that have attracted heavy criticism over the past decade.

References

- 1.Sector strategy: health, nutrition, and population. Washington, DC: World Bank; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 2.The World Bank’s role, annual report 1998. World Bank. http://www.worldbank.org/html/extdr/backgrd/ibrd/role.htm (accessed 22 February 1999).

- 3.Repositioning the WHO. Economist 1998 May 9.

- 4.Mach A. Interview with G H Bruntland: the “new WHO” commits to making a difference. BMJ. 1998;317:302. [Google Scholar]