The World Bank is accustomed to criticism, and since the second world war few organisations have generated as much outcry. Most analysts, however, accept that the bank has conducted a successful campaign to improve its image over the past decade. Indeed, I was surprised during my meetings with health workers outside the bank that it attracted far less criticism than I had expected. None the less, reservations remain about the bank’s approach, and this article discusses some of the most controversial aspects of the bank’s policies.

Summary points

Despite its recent change in image, the World Bank still has staunch critics

Structural adjustment, user charges, and DALYs (disability adjusted life years) are unpopular strategies that have attracted criticism for many years

Introducing evidence into policy making and ensuring sustainability of projects are key issues for the future

These issues and the bank’s underuse of health outcome measures are stumbling blocks to wider acceptance of its policies

Structural adjustment

Critics of the World Bank argue that structural adjustment loans are a mechanism of forcing free market economics on countries through coercion. Countries with a debt crisis, whatever their other characteristics, agree to the bank’s package of legal and economic reforms, and the bank agrees to lend them money. Argentina, Ecuador, and India have all either weakened their labour legislation or amended their land laws to qualify for an adjustment loan. India is reported to have changed 20 pieces of major legislation.1

Common criticisms of the World Bank

Creating a climate where high levels of lending are deemed to be good

Advocating disability adjusted life years as a health measure

Disregard for the environment and indigenous populations

Evaluating health projects by looking at economic outcome measures

Insufficient evaluation of projects

Lack of sustainability of projects

Poor evidence base for policies

Promoting private health care

Forcing countries to adopt structural adjustment for their economies

User charges

Bank employees themselves have been sceptical about the wisdom and potential efficacy of such reforms, and the bank’s critics have been scathing about the negative impact that adjustment loans have had on economies and on health indicators. The bank’s hope is that adjustment should take no more than five years and require no more than five loans, but its figures reveal that, by 1995, not one out of 88 countries that had embarked on adjustment had stuck to the bank’s timescale.2

The bank’s view is that by achieving increased gross domestic product, domestic investment, and exports, and reduced inflation rates and “excessive” external borrowing, structural adjustment will lead to a reduction in poverty.2 World debt, however, has risen from $0.5 trillion to $1.2 trillion between 1980 and 1992, with most countries that have pursued structural adjustment policies being in greater debt.3 According to Unicef, a drop of 10-25% in average incomes in the 1980s—the decade noted for structural adjustment lending—in Africa and Latin America, and a 25% reduction in spending per capita on health and a 50% reduction per capita on education in the poorest countries of the world, are mostly attributable to structural adjustment policies.4 Unicef has estimated that such adverse effects on progress in developing countries resulted in the deaths of half a million young children—and in just a 12 month period.

However debatable the cause of these worsening indicators—and world debt increased more rapidly in the 1970s than the 1980s—the bank admits that structural adjustment does have drawbacks, and that in the short term the poor may suffer more—in some cases “short term” may mean up to 30 years.5 Adjustment, as shown by the bank’s own research, increases exports but does not reduce inflation, or achieve significant long term gains in gross domestic product or investments, and may in fact cause investments to drop.6 It may be that adjustment policies are better suited to richer countries, and indeed internal reports have suggested that there is little evidence for the success of structural adjustment in lower income countries.7

The bank argues that since it was formed in 1944 “economic progress has been faster than during any similar period in history” and that “far from being victims of reforms, the poor suffer most when countries don’t reform. What benefits the poor the most is rapid and broad based growth. This comes from having sound macroeconomic policies and a strategy that favours investment in basic human capital—primary health care and universal primary education.”8 Otherwise, the bank argues, adjustment is disorderly and more costly.9

The sector-wide approach

A key development in the bank’s thinking has been the espousal of the sector-wide approach, which the former director of the health, nutrition, and population sector, Richard Feacham, is credited with popularising in the bank’s Human Development Network. Donors have traditionally funded projects that address single diseases or specific health reforms, but this mechanism is thought to be flawed because it engenders a fragmented approach to health care delivery, with projects often being duplicated and both donors’ and clients’ time being consumed by project assessments. The sector-wide approach is increasingly being implemented in countries throughout Africa and Asia, and the bank sees it as being successful in raising government expenditure on the social sector in countries like Ghana and Pakistan.

Analysing sector-wide approaches, Cassels (an independent researcher) and Janovsky (from the division of analysis, research, and assessment of the World Health Organisation in Geneva) say, “Rather than selecting individual projects, international agencies contribute to the funding of the entire sector. In exchange for giving up the right to select projects according to their own priorities, donors gain a voice (but not a controlling interest) in the process of developing national health policies, and in decisions about how not only external but also domestic resources are allocated.”10

Few bank employees and clients are critical of the sector-wide approach; indeed, they are welcoming, seeing it as a means of developing a more comprehensive policy for that particular sector. However, some bank staff doubt that it is a radical shift in policy. One senior bank employee told me: “The debate pitting the value of the sector-wide approach against the merits of vertical projects is a false dichotomy. In fact, most bank projects deal with health policy and policy change.”

Cassels and Janovsky warn that sector-wide approaches may entail that “human development will be increasingly dominated by interests of governments and intergovernmental agencies. International and national non-governmental organisations fear that their traditional independence may become severely restricted,” but they concur with the general view: “The verdict so far: a promising start to a more grown-up relationship.”

User charges

Though bank lending for the health sector has increased over the years, low income countries remain disadvantaged and unable to meet, or maintain, health service costs. One way to raise funds has been to levy a fee, often called a user charge, for using public sector health services. Many health professionals and representatives of non-governmental organisations hold the World Bank responsible for introducing this concept, and they point to evidence showing that user charges result in a decline in the uptake of services, especially among the people who are most socioeconomically deprived.11

“Increases in maternal mortality and in the incidence of communicable diseases such as diphtheria and tuberculosis have been attributed to such policies,” argues Andrew Creese, a health economist at the World Health Organisation. “As an instrument of health and policy, user fees have proved to be blunt and of limited success and to have potentially serious side effects in terms of equity. They should be prescribed only after alternative interventions have been considered.”12

The bank claims not to actively promote user charges; instead, it suggests that they should be considered as another instrument for raising revenue. Years of criticism seem to have made the bank much more wary about forwarding this unpopular measure, but although critics and patients remain sceptical, doctors and government officials in low income countries are more in favour of their use, simply because of a lack of alternatives.

Alex Preker, a principal economist at the bank and coauthor of its 1997 strategy for the health, nutrition, and population sector, believes that the bank’s policy was misinterpreted: “The 1987 document on financing health services in developing countries was the one that highlighted the bank’s thinking about user charges, and people interpreted it in the way that they wanted. What the paper actually says is that user charges are part of a panoply of instruments available to countries for resource mobilisation, but what happened afterwards was that the bank was hammered for about 10 years, especially in Africa, for promoting user charges and taxing the poor. We, in this paper [the 1997 sector strategy], distance ourselves from that and make it quite clear that it isn’t bank policy. The bank doesn’t have a particular policy on whether user charges should or shouldn’t be used.”

Preker believes that risk pooling is the way forward, which means that people in low income countries contribute to insurance schemes so that when they are ill they share the cost with others: “You put a standard amount of money into the pot, and when you get sick you get full treatment. If you don’t get sick, you put money into the pot and you get nothing.” Which means, he envisages, that low income countries would have to go through a similar development phase to 19th century Europe, when community groups and friendly societies generated sickness funds through risk pooling.

The rule of DALYs

The bank defines the DALY (disability adjusted life year) as “a unit used for measuring both the global burden of disease and the effectiveness of health interventions, as indicated by reductions in the disease burden. It is calculated as the present value of the future years of disability-free life that are lost as the result of the premature deaths or cases of disability occurring in a particular year.”13

Richard Feacham, who chaired the advisory committee for the 1993 World Development Report, which introduced this measure, believes that it “broke new ground in presenting the global burden of disease analysis and inventing the metric of the DALY, which has now become widely adopted in discussions about health sector development. It broke new ground in taking forward the debate about cost effectiveness, as you’re able to measure mortality outcomes and morbidity outcomes through the DALY.”

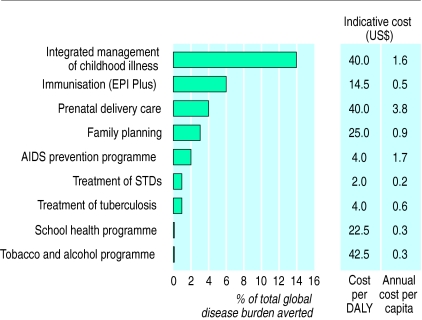

In this way, a value in dollars can be attached to each healthcare intervention to work out the amount that needs to be spent to gain, or buy, a DALY (figure; table). DALYs are gauged against a standard expectation of life at birth of 80 years for men and 82.5 years for women, and are derived by using a set of “value choices” which take into account age, sex, disability status, and time of illness.14 The aim is to keep the number of DALYs low. The bank believes that this measure helps focus health policy: for example, while $10 will buy a DALY for a child in need of vitamin supplementation or vaccination, tens of millions of dollars may be needed to buy a DALY for a patient in hospital. Critics point out, however, that the introduction of DALYs was not based on sound methodology, and that the underlying assumptions for their usefulness are weak.

Sudhir Anand, acting director of the Harvard Center for Population and Development Studies, and Kara Hanson of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine disagree with the bank’s view: “The DALY information set consists only of age, sex, disability status, and time period—which does not allow individuals’ socioeconomic circumstances to be taken into account. An equitable approach to resource allocation will use a criterion which attaches a greater weight to the illness of more disadvantaged people.”15

They argue that although DALYs are being increasingly used for health sector planning, they are in fact an inequitable measure of ill health and as such an inappropriate and unfair criterion for resource allocation: “Through age-weighting and discounting, they place a different value on years lived at different ages and at different points in time. They value a year saved from illness more for the able-bodied than the disabled, more for those in middle age-groups than the young or elderly, and more for individuals who are ill today compared with those who will be ill in the future.”15

Evidence and sustainability

Similarly, critics of the bank argue that it recommends policies that aren’t evidence based, a potentially critical error as lending money for such projects is likely to deepen debt without affording benefit in terms of health. The bank counters this by saying that its policies are well researched.

Paul Garner, head of the international division of the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, is sceptical: “The 1993 World Development Report came out before systematic reviews were being done, so there weren’t any its authors could use. The shame is that they didn’t do any themselves. But some reviews now on the Cochrane database are incompatible with bank policies—for example, the bank advises supplemental feeding in pregnancy but the Cochrane review suggests that there’s no benefit from it. Also, some of the bank’s recommendations on helminth treatment are only supported by weak evidence. Another problem is that the bank often focuses on findings from observational studies, and when they do accumulate evidence, they don’t do it systematically.”

Sustainability is an issue that bank employees accept has been neglected in the past, and, although it is addressed as a priority in the 1997 sector strategy document, how this objective will be achieved remains unclear. Indeed, the bank has been unable to allay the fears of doctors and healthcare workers in disadvantaged countries, as sustainability is the most prominent and most commonly mentioned concern.

The bank’s recent strategic changes, like the decentralisation of bank operations and the sector-wide approach, are largely welcomed by bank employees. More interaction with governments, however, does bring its own problems. When considering the fine line between buttering up governments and bullying them, employees are acutely aware that their career progression might depend on the way they are perceived by the government that they are lending to, and by subsequent feedback to seniors in Washington. In a climate where greater lending earns bigger plaudits, the danger of pushing rather than holding back on hairline lending decisions is also readily apparent.

Conclusion

The bank’s very nature is that it will generate criticism, often scathing. Certainly, it vigorously defends its economic reform policies without much room for negotiation with governments. Now, however, it seems to be distancing itself from unpopular policies like user charges. Nonetheless, genuine concerns remain about the strength of the evidence base for the bank’s policies and the sustainability of bank projects once loan monies have run out. While these hurdles, on top of the bank’s stated difficulty in finding suitable outcome measures, are difficult to surmount, they go to the core of why the bank’s policies will remain unacceptable to many, and they perpetuate the perception that the bank is all about lending dollars rather than improving health.

Table.

Disability adjusted life years (DALYs) lost, by cause and demographic region, 1990

| Cause | World | Sub-Saharan Africa | India | China | Other Asia and islands | Latin America and the Caribbean | Middle Eastern crescent | Formerly socialist economies of Europe | Established market economies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population (millions) | 5267 | 510 | 850 | 1134 | 683 | 444 | 503 | 346 | 798 |

| Communicable diseases: | 45.8 | 71.3 | 50.5 | 25.3 | 48.5 | 42.2 | 51.0 | 8.6 | 9.7 |

| Tuberculosis | 3.4 | 4.7 | 3.7 | 2.9 | 5.1 | 2.5 | 2.8 | 0.6 | 0.2 |

| Sexually transmitted diseases and HIV | 3.8 | 8.8 | 2.7 | 1.7 | 1.5 | 6.6 | 0.7 | 1.2 | 3.4 |

| Diarrhoea | 7.3 | 10.4 | 9.6 | 2.1 | 8.3 | 5.7 | 10.7 | 0.4 | 0.3 |

| Childhood infections preventable by vaccination | 5.0 | 9.6 | 6.7 | 0.9 | 4.5 | 1.6 | 6.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Malaria | 2.6 | 10.8 | 0.3 | <0.05 | 1.4 | 0.4 | 0.2 | <0.05 | <0.05 |

| Worm infections | 1.8 | 1.8 | 0.9 | 3.4 | 3.4 | 2.5 | 0.4 | <0.05 | <0.05 |

| Respiratory infections | 9.0 | 10.8 | 10.9 | 6.4 | 11.1 | 6.2 | 11.5 | 2.6 | 2.6 |

| Maternal causes | 2.2 | 2.7 | 2.7 | 1.2 | 2.5 | 1.7 | 2.9 | 0.8 | 0.6 |

| Perinatal causes | 7.3 | 7.1 | 9.1 | 5.2 | 7.4 | 9.1 | 10.9 | 2.4 | 2.2 |

| Other | 3.5 | 4.6 | 4.0 | 1.4 | 3.3 | 5.8 | 4.9 | 0.6 | 0.5 |

| Non-communicable diseases: | 42.2 | 19.4 | 40.4 | 58.0 | 40.1 | 42.8 | 36.0 | 74.8 | 78.4 |

| Cancer | 5.8 | 1.5 | 4.1 | 9.2 | 4.4 | 5.2 | 3.4 | 14.8 | 19.1 |

| Nutritional deficiencies | 3.9 | 2.8 | 6.2 | 3.3 | 4.6 | 4.6 | 3.7 | 1.4 | 1.7 |

| Neuropsychiatric disease | 6.8 | 3.3 | 6.1 | 8.0 | 7.0 | 8.0 | 5.6 | 11.1 | 15.0 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 3.2 | 1.5 | 2.1 | 6.3 | 2.1 | 2.6 | 2.4 | 8.9 | 5.3 |

| Ischaemic heart disease | 3.1 | 0.4 | 2.8 | 2.1 | 3.5 | 2.7 | 1.8 | 13.7 | 10.0 |

| Pulmonary obstruction | 1.3 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 5.5 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 1.6 | 1.7 |

| Other | 18.0 | 9.7 | 18.5 | 23.6 | 17.9 | 19.1 | 18.7 | 23.4 | 25.6 |

| Injuries: | 11.9 | 9.3 | 9.1 | 16.7 | 11.3 | 15.0 | 13.0 | 16.6 | 11.9 |

| Motor vehicle | 2.3 | 1.3 | 1.1 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 5.7 | 3.3 | 3.7 | 3.5 |

| Intentional | 3.7 | 4.2 | 1.2 | 5.1 | 3.2 | 4.3 | 5.2 | 4.8 | 4.0 |

| Other | 5.9 | 3.9 | 6.8 | 9.3 | 5.8 | 5.0 | 4.6 | 8.1 | 4.3 |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Millions of DALYs: | 1362 | 293 | 292 | 201 | 177 | 103 | 144 | 58 | 94 |

| Equivalent infant deaths (millions) | 42.0 | 9.0 | 9.0 | 6.2 | 5.5 | 3.2 | 4.4 | 1.8 | 2.9 |

| DALYs per 1000 population | 259 | 575 | 344 | 178 | 260 | 233 | 286 | 168 | 117 |

Less than 0.05%.

Source: World Bank data.

Figure.

Cost of public health and clinical services

References

- 1.Public Interest Research Group. The World Bank and India. New Delhi: Public Interest Research Group; 1994. p. 60. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Caulfield C. Masters of illusion: the World Bank and the poverty of nations. London: MacMillan; 1997. p. 149. [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Debt Tables, 1992-3. Washington, DC: World Bank; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Unicef. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1989. The state of the world’s children; pp. 16–17. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bolivia: riches for poverty. Economist 1998 Oct 17.

- 6.World Bank. Adjustment lending: policies for sustainable growth. Washington, DC: World Bank; 1990. p. 11. . (Country economics department, policy and research series No 14.) [Google Scholar]

- 7.Killick T. Improving the effectiveness of financial assistance for policy reforms. Report from World Bank Development Committee. Washington, DC: World Bank; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Bank. The World Bank’s role, annual report 1998. www.worldbank.org/html/extdr/backgrd/ibrd/role.htm (Accessed 22 Feb 1999.)

- 9.World Bank. Adjustment lending and mobilization of private and public resources for growth. Washington, DC: World Bank; 1992. p. 14. . (Country economics department, policy and research series No 22.) [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cassels A, Janovsky K. Better health in developing countries: are sector-wide approaches the way of the future? Lancet. 1998;352:1777–1779. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)05350-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McPake B. User charges for health services in developing countries: a review of the economic literature. Soc Sci Med. 1994;39:1189–1201. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(93)90382-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Creese A. User fees. BMJ. 1997;315:202–203. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7102.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Bank. World development report 1993: investing in health. New York: Oxford University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murray CJL, Lopez AD. The global burden of disease. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anand S, Hanson K. DALYs: efficiency versus equity. World Development. 1998;26:307–310. [Google Scholar]