Abstract

Background

Understanding antecedents and consequences of incivility across higher education is necessary to create and implement strategies that prevent and slow uncivil behaviors.

Purpose

To identify the nature, extent, and range of research related to antecedents and consequences of incivility in higher education.

Objectives

1) To identify disciplines and programs sampled in higher education incivility research, and 2) to compare antecedents and consequences examined in nursing education research with other disciplines and programs in higher education.

Design

A scoping review of the literature.

Data sources

Eight electronic databases searched in January 2023 including MEDLINE Ovid, CINAHL, ERIC, PsycINFO, Scopus, ProQuest Education Database, Education Research Complete, and ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global.

Review methods

We included primary research articles examining antecedents or consequences of incivility in higher education. Two reviewers independently screened and determined inclusion of each study. Data extraction was completed. We employed a numerical descriptive summary to analyze the range of data and content analysis to categorize the antecedents and consequences of incivility in higher education.

Results

Database searches yielded 6678 unique articles. One hundred and nineteen studies published between 2003 and 2023 met the inclusion criteria, of which, 65 reported research in nursing education, and 54 in other programs and disciplines. A total of 91 antecedents and 50 consequences of incivility in higher education were reported. Stress (n = 12 nursing, n = 4 other programs), faculty incivility (n = 9 nursing, n = 5 other programs), and student incivility (n = 4 nursing, n = 5 other programs) were reported as antecedents of incivility in higher education. Physiological and psychological negative outcomes (n = 25 nursing, n = 12 other programs), stress (n = 6 nursing, n = 6 other programs), and faculty job satisfaction (n = 3 nursing, n = 2 other programs) were reported as consequences of incivility in higher education

Conclusions

Supporting development of teaching practices and role modeling of civility by faculty is a crucial element to slowing the frequency of uncivil interactions between faculty and students. Specific strategies that target stress, such as, cognitive behavioral therapy, coping skills, and social support could mitigate incivility in higher education. Future research needs to examine the strength of the negative effects of incivility on physiological and psychological outcomes through advanced statistical methods, as well as the cumulative effects of uncivil behavior on these outcomes over time for both students and faculty. Application of advanced statistical methods can also support our understanding of sources of incivility as well as the accuracy of causal connections between its antecedents and consequences.

Keywords: Incivility, Higher education, Nursing education, Scoping review, Antecedents, Consequences

-

•

Incivility is a concerning occurrence in the academic setting affecting nursing education, and other areas of higher education such as occupational therapy, dentistry, engineering, mathematics, sciences, and liberal arts.

-

•

Experiencing incivility in nursing education may result in damaging effects for both nursing students and nursing faculty including strained relationship and satisfaction in their jobs and program.

Alt-text: What is already known about the topic?

-

•

Our review located reports that faculty incivility contributed to, triggered, and was even used to justify student incivility. Student incivility and competition among students also contributed to student incivility.

-

•

Supporting faculty in role modeling of civility and strategies targeting student stress may help to prevent, mitigate, and slow occurrences of incivility.

-

•

Future research needs to examine the strength of the effects of incivility on physiological and psychological outcomes through advanced statistical methods, as well as cumulative effects on these outcomes over time for students and faculty who receive or witness uncivil behaviour.

Alt-text: What this paper adds

1. Introduction

Incivility is a concerning occurrence affecting nursing education (Al-Jubouri et al., 2020; Clark et al., 2013; Natarajan et al., 2017; Small et al., 2019), and other areas of higher education such as occupational therapy (Bolding et al., 2020), dentistry (Ballard et al., 2018), engineering, mathematics, sciences, and liberal arts (Wagner et al., 2019). Understanding the nature of incivility across higher education, including its antecedents and consequences, is necessary for the creation and implementation of strategies to prevent, mitigate, and slow the incidence of uncivil behaviors (Clark et al., 2009). Given that the academic environment is an ideal place to promote civility and teach the skills to effectively manage incivility in practice (Bloom, 2019), increasing the understanding of incivility across disciplines in higher education may help faculty to work together on these strategies (Wagner et al., 2019).

Despite the wide reach of incivility in higher educational settings, most of the research has focused on nursing education (Ballard et al., 2018; Wagner et al., 2019). In nursing education, incivility has been defined as “the perception of verbal or nonverbal actions that demean, dismiss or exclude an individual” (Patel and Chrisman, 2020, p.6) or any speech or action that disrupts the harmony of the teaching and learning environment (Clark and Springer, 2007). Incivility includes faculty incivility towards students, student incivility towards faculty, student-to-student incivility, and faculty incivility towards other faculty and administrators. Regardless of who is involved, experiencing incivility in nursing education may result in damaging effects. Incivility can be a barrier to positive student-faculty relationships (Ingraham et al., 2018). Nurse educators can experience interrupted sleep patterns, self-doubt, self-blame, changes in confidence and self-esteem, recurrent reliving of events, and even consideration of actual withdrawal from nursing education because of encounters with student incivility (Luparell, 2007). Uncivil encounters with students can affect the recruitment and retention of nursing faculty (DalPezzo and Jett, 2010). Nursing students may respond to faculty incivility experiences with emotional distress, poor learning outcomes, and bitterness towards the nursing profession (Holtz et al., 2018). Experiences with incivility were also associated with nursing students’ dissatisfaction with their nursing programs (Marchiondo et al., 2010; Todd et al., 2016).

The purpose of this scoping review was to identify the nature, extent, and range of research related to the antecedents and consequences of incivility in higher education. Our objectives were: 1) to identify disciplines and programs sampled in higher education incivility research; and 2) to compare antecedents and consequences examined in nursing education research with other disciplines and programs in higher education. We focused on nursing with the opportunity to compare to other higher education disciplines and programs. The nursing perspective presented in this scoping review, represents the opinions and interpretations of the nursing authors who conducted the study.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design

We applied the methodological framework for a scoping review, as originally described by Arksey and O'Malley (2005) and enhanced by Levac et al. (2010).

2.2. Search strategy and data sources

Eight electronic databases were searched in January 2023 including MEDLINE Ovid, CINAHL, ERIC, PsycINFO, Scopus, ProQuest Education Database, Education Research Complete, and ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global (Table 1). In consultation with a university health sciences librarian, we developed a search strategy to maximize the number of articles. The university health sciences librarian advised on the electronic databases, the specific search and MeSH terms, and helped to formulate a sample search strategy for MEDLINE Ovid. Search terms included: “higher education”; “professional education”; “post-secondary”; “college”; “university”; “institution”; “education”; “learning”; “studies”; “school”; “incivility”, “civility”, “civil behavior”, “bullying”; “horizontal violence”; “lateral violence”; “vertical violence”, “harassment” and “workplace violence”. A search of Grey Literature, apart from dissertations, was not actively sought due to the focus on research. Initially no limitations were placed on publication dates, language, or study design. A visual scan of the references of included articles was completed to identify further articles.

Table 1.

Literature search of electronic databases.

| Database To January 2023 | Search terms | Number |

|---|---|---|

| Ovid MEDLINE | “higher education” or education, professional or universities or Advanced or Postsecondary or post-secondary or College* or Universit* or Graduate or professional or education or learning or studies or study or institut* or school* AND incivil* or uncivil* or civility or civil behavior or civil behaviour or bully* or horizontal violence or lateral violence or vertical violence or harrass* or harassment, non-sexual or incivility or workplace violence | 927 |

| ERIC Ovid | Same as above | 52 |

| PsycINFO Ovid | Same as above | 2918 |

| CINAHL | Same as above | 493 |

| Education Research Complete (EBSCO) | Same as above | 1033 |

| Scopus | incivil* or uncivil* or civility or civil behavior or civil AND behaviour or bully* or horizontal AND violence or lateral AND violence or vertical AND violence or harrass* AND in AND higher AND education | 270 |

| ProQuest Education Database | incivil* or uncivil* or civility or civil behavior or civil behaviour or bully* or horizontal violence or lateral violence or vertical violence or harrass* AND ‘higher education” | 714 |

| ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global | Same as above | 361 |

| Manual Search | 55 | |

| Total search results prior to duplicate removal | 6823 | |

| Total Titles and Abstracts Reviewed (Duplicates Removed) | 6678 | |

| Full text Screening of Studies | 388 | |

| FINAL Included Studies | 119 | |

2.3. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria were: 1) primary research; 2) aim/purpose to examine incivility in higher education environments; 3) examined antecedents or consequences of incivility in higher education; and 4) full text available in English. Exclusion criteria were: 1) incivility in any other context than higher education; 2) reviews (systematic, integrative, scoping); or 3) full text not available in English. Reviews were excluded due to risk of duplication; however, they were tracked for a hand search of the reference list. Quality appraisal was not part of the selection process for this review.

2.4. Screening

Pairs of independent reviewers (TP, PC, KT) screened titles and abstracts as well as full text records. Reviewer pairs held consensus meetings to discuss discrepancies, and consensus was reached in all cases. Covidence (Covidence Systematic Review Software, 2023) was used for screening records.

2.5. Data extraction

The following data elements were extracted from included studies: 1) study characteristics (author, year, journal, country), 2) study design and theoretical framework, 3) study aim/purpose, research question(s), or objectives; 4) study population, sample, and setting, 5) methods (data collection, data analysis, instruments used), and 6) identified or examined antecedents or consequences of incivility. Two reviewers (TP, PC) independently extracted data from the first 10 records and discussed if the approach was consistent and relevant to the review purpose (Levac et al., 2010). There was consensus of independent data extraction of a small number of selected included studies that one reviewer (TP) continued with data extraction while the second reviewer (PC) verified data against the articles. The reviewers were sufficiently qualified to conduct the screening and data extraction processes. One of the authors (GGC) has extensive experience in conducting systematic and scoping reviews, resulting in 48 published reviews.

2.6. Data synthesis

We employed a numerical descriptive summary to analyze the range of data demonstrating the nature, extent, and distribution of research on antecedents and consequences of incivility in higher education by faculty and student groups. We used inductive content analysis (Elo and Kyngas, 2008) to categorize antecedents and consequences of incivility in higher education. We categorized the antecedents and consequences by those reported in multiple studies to indicate the frequency and magnitude of specific antecedents and consequences in included studies.

We followed the studies’ authors and their application of the term ‘antecedent’ or its equivalent as correlated or associated factors or predictors in regression models in quantitative studies. Although causal structuring was implied in the application of the term ‘antecedent’, the lack of methodological attention lends little support that the antecedents can be considered as true causes of incivility. In quantitative studies, we followed what authors reported as consequences or outcomes of incivility either through correlational, regression analysis, or modeling. Study participants in qualitative studies self-reported their reactions, responses, and feelings as consequences of experiencing incivility. This raises an intriguing methodological issue about whether reported ‘consequences’ were caused by incivility or were they simply how study participants felt about experiencing incivility.

We did not consult experts to confirm the findings as this was an optional stage in the Arksey and O'Malley (2005) framework of scoping reviews. Given the authors’ extensive expertise in conducting and publishing reviews, we did not think that external consultation would lead to different interpretations of the findings.

3. Results

3.1. Search results

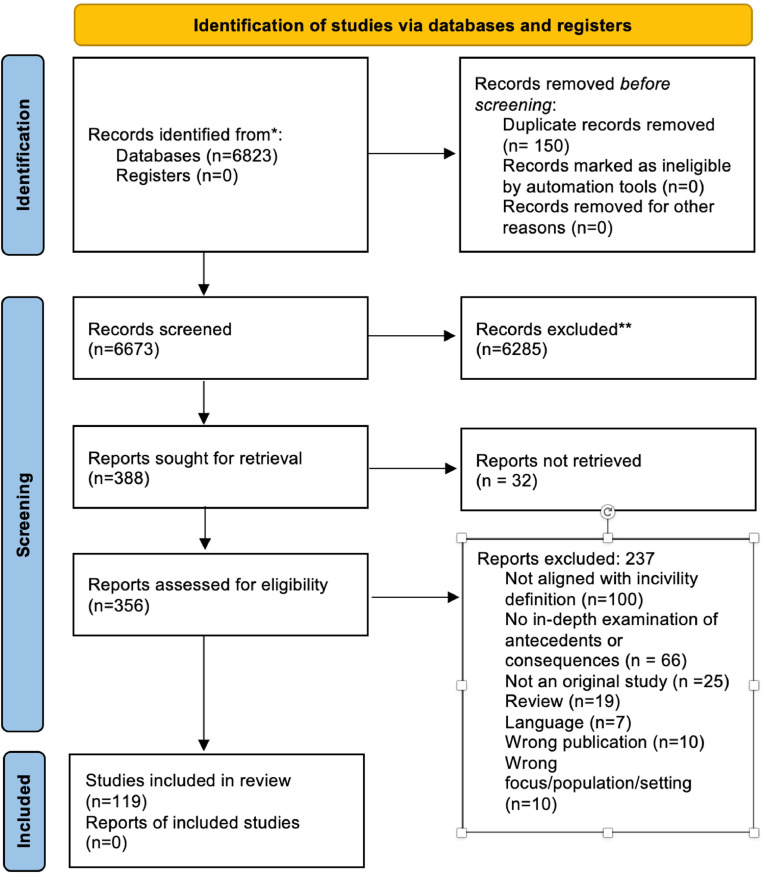

Online database searches yielded a total of 6678 unique articles for title and abstract screening; 388 records were then selected for full text screening, of which 119 articles were included (Fig. 1& Table 2).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA diagram.

Table 2.

List of Included Studies (n = 119) (references in supplementary file 4).

| Ref# | Author(s), Year | Ref# | Author(s), Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Agbaje et al. (2021) | 64 | Lampman et al. (2009) |

| 2 | Alberts et al. (2010) | 65 | Lampman et al. (2016) |

| 3 | Al Jubouri et al. (2021) | 66 | LaSala et al. (2016) |

| 4 | Alt & Itzkovich (2015) | 67 | Lasiter et al. (2012) |

| 5 | Alt & Itzkovich (2016) | 68 | Luparell (2003); Luparell (2007) |

| 6 | Alt et al. (2022) | 69 | MacDonald et al. (2022) |

| 7 | Altmiller (2012) | 70 | Martel (2015) |

| 8 | Amos (2013) | 71 | Marchand-Stenhoff (2009) |

| 9 | Aul (2017) | 72 | Marchiondo et al. (2010) |

| 10 | Babenko-Mould & Laschinger (2014) | 73 | McCarthy et al. (2020) |

| 11 | Bartlett (2009) | 74 | McClendon et al. (2021) |

| 12 | Bartlett & Bartlett (2016) | 75 | McCown (2021) |

| 13 | Bence et al. (2022) | 76 | McGee (2020); McGee (2021) |

| 14 | Boice (1996) | 77 | McKinne (2008) |

| 15 | Booth (2017) | 78 | Miner et al. (2019) |

| 16 | Braxton & Jones (2008) | 79 | Minton & Birks (2019) |

| 17 | Bunce (2021) | 80 | Mohammadipour et al. (2018) |

| 18 | Buhrow & Yehle (2022) | 81 | Morning (2014) |

| 19 | Byrnes (2015) | 82 | Naseri et al. (2023) |

| 20 | Cahyadi et al. (2021) | 83 | Ndazhaga (2014) |

| 21 | Casale (2017) | 84 | Nordstrom et al. (2009) |

| 22 | Cates (2021) | 85 | Ogunbote (2020) |

| 23 | Caza and Cortina (2007) | 86 | Offstein & Chory (2017) |

| 24 | Chavez Rudolph (2005) | 87 | Orfan (2022) |

| 25 | Chory & Offstein (2017) | 88 | Patel et al. (2022) |

| 26 | Christensen et al. (2020) | 89 | Peters (2014) |

| 27 | Christensen et al. (2021) | 90 | Rad et al. (2017) |

| 28 | Clark (2008a) | 91 | Sauer et al. (2017) |

| 29 | Clark (2008b) | 92 | Segrist et al. (2018) |

| 30 | Clark et al. (2012) | 93 | Shen et al. (2020) |

| 31 | Clark et al. (2021) | 94 | Sherrod et al. (2021) |

| 32 | Courtney-Pratt et al. (2018) | 95 | Small et al. (2019) |

| 33 | DeGagne et al. (2018) | 96 | Smith et al. (2022) |

| 34 | Dela Cruz (2022) | 97 | Spohn (2016) |

| 35 | Del Prato (2013) | 98 | Sprunk (2013) |

| 36 | DeSouza (2011) | 99 | Stephens (2020) |

| 37 | Doshy (2014) | 100 | Streif (2019) |

| 38 | El Hachi (2020) | 101 | Sweetnam (2014) |

| 39 | Epps (2016) | 102 | Tee et al. (2016) |

| 40 | Frisbee et al. (2019) | 103 | Thomas (2018) |

| 41 | Frye (2015) | 104 | Thupayagale‐Tshweneagae et al. 2020 |

| 42 | He at al. (2021) | 105 | Tower-Siddens (2014) |

| 43 | Heffernan et al. (2021) | 106 | Trad et al. (2012) |

| 44 | Herrin (2014) | 107 | Urban et al. (2021) |

| 45 | Hodgins & McNamara (2017) | 108 | Vermillera (2018) |

| 46 | Holtz (2016) | 109 | Vink & Adejumo (2015) |

| 47 | Huang et al. (2020) | 110 | Vural et al. (2020) |

| 48 | Hudgins et al. (2022) | 111 | Weger (2018) |

| 49 | Hyun et al. (2022) | 112 | Wegleitner (2021) |

| 50 | Ibrahim & Qalawa (2016) | 113 | Wentz (2015) |

| 51 | Irwin & Cederblad (2019) | 114 | Williams (2017) |

| 52 | Irwin et al. (2021) | 115 | Williamson (2011) |

| 53 | Jiang et al. (2017) | 116 | Wilson-Taylor (2006) |

| 54 | Karacay & Oflaz (2022) | 117 | Woo & Kim (2022) |

| 55 | Keating (2016) | 118 | Wyatt (2018) |

| 56 | Kershaw (2019) | 119 | Yassour-Borochowitz and Desivillia (2016) |

| 57 | Kim (2018) | ||

| 58 | Klebig et al. (2016) | ||

| 59 | Knepp & Knepp (2022) | ||

| 60 | Kopp & Finney (2013) | ||

| 61 | Koshy (2019) | ||

| 62 | Krug (2021) | ||

| 63 | Lambert et al. (2020) |

3.2. Characteristics of included studies

Most studies were conducted in the United States of America (n = 77), followed by Australia (n = 5), Israel (n = 4), and Canada (n = 4). Three studies were conducted in each of China, United Kingdom, South Korea, and Iran, while 2 studies were conducted in each of South Africa, Turkey, and Nigeria. Countries with single studies included: United States of America/Canada, Indonesia, United Arab Emirates, Ireland, Scotland/United Kingdom/Ireland, Scotland, Egypt, Botswana, Afghanistan, and New Zealand. One study was conducted in a multi-country setting. Characteristics of included studies can be found in Supplementary File 1.

Sixty-five studies reported research in nursing education, and 54 were research in other disciplines and programs, including business (n = 3), dental hygiene (n = 2), social sciences (n = 1), psychology (n = 1), pharmacy (n = 1), social work (n = 1), law (n = 1), and samples from multiple programs or disciplines (n = 43). Sixty-three studies employed qualitative or mixed method research design, and 56 studies used quantitative research designs. Fifty studies reported on antecedents of incivility in higher education, 45 reported on consequences, and 24 examined both antecedents and consequences.

3.3. Measures of incivility

In the 119 included studies, 64 used 23 different measurement instruments to measure incivility in higher education. Fourteen studies used the Incivility in Nursing Education Survey (original or revised version) (Clark et al., 2009, 2015), 13 used the Workplace Incivility Scale (Cortina et al., 2001; Cortina et al., 2011), 4 studies used the Nursing Education Environment Survey (Marchiondo et al., 2010), 4 studies used the Perceived Faculty Incivility Scale (Alt and Itzkovich, 2015), 3 studies used the 2000 Indiana University Survey on Academic Incivility, 2 studies used the Uncivil Workplace Behavior Questionnaire (Martin and Hine, 2005), 2 studies used the Workplace Incivility Survey (Clark, 2013), 3 studies used the Uncivil Behavior in Clinical Education Tool- Korean (Jo and. Oh, 2016) and Chinese (Cui et al., 2017) versions, 2 studies used Academic Contrapower Harassment measure (Lampman et al. 2009), 2 studies used the Taxonomy of Uncivil Classroom Behaviors (Bjorklund and Rehling, 2010), 2 studies used the Incivility in Higher Education- Revised Survey (Clark et al., 2009), and 2 studies used the Uncivil Behavior in Clinical Education Tool- English version (Anthony et al., 2014). Measurement instruments used in single studies include: the Student Classroom Incivility measure, Student Incivility measure (Nutt, 2013), Questionnaire on Teacher Interaction in Higher Education, Student Experience of Bullying during Clinical Placement (Budden et al., 2017), Faculty to Faculty Incivility Survey (Casale, 2017), Classroom Incivility (Chory and Offstein, 2014), Appropriateness of Uncivil Behavior Scale, Normative Appropriateness of Uncivil Behavior Scale, Incivility in Online Learning Environments (Clark et al., 2012), Attitude Toward Classroom In/Civility Scale (Farell et al., 2016), and Student Experience during Clinical Placement (Budden et al., 2017). No studies compared the various measures to provide evidence that these measures are indeed assessing a similar understanding of incivility.

3.4. Theoretical frameworks

Fifty-four studies in total included some type of theory, framework, or conceptual model to guide their research. Some studies used more than one theoretical or conceptual framework to guide the research. Ten studies used the Conceptual Model for Fostering Civility in Nursing Education (Clark, 2008a), 5 studies used Andersson and Pearson's (1999) Incivility Spiral and 3 studies used Watson's (2012) Human Caring theory. Five studies used Bandura's (1977) Social Learning theory, 3 studies used Attribution theory, 3 studies used Social Critical theory, 2 studies used Cognitive Appraisal (Lazarus, 1966), 2 studies used the Model for bullying (Salin, 2003), and 2 studies used Roy's Adaptation model. Theoretical or conceptual frameworks used in single studies include: Maslach and Leiter's (1997) Burnout theory, Mezirow's theory of Transformational Learning, Symbolic interactionism, Bourdieu's (1972) Social Practice theory framework, concepts of incivility in higher education (Caza and Cortina, 2007), Institutional satisfaction (Hatcher et al., 1992), Need to Belong Theory (Baumeister, 2012), Theory of the Nurse as Wounded Healer (Conti-O'Hare, 2002), Turner's Classic empowerment model, Herzberg's Motivation-Hygiene Theory (1966), Lewin's (1951) Theory of Planned Change, Equity theory, Appreciative Inquiry, Transformational Leadership, Broken Window Theory, Biblical perspective, Mood Congruence Theory (Bower, 1981), Pondy (1967) conceptual models organizational conflict, Blake and Mouton‘s (1964) Dual Concern Theory, Element of Transformational Leadership Influencing Civility and Wellbeing theoretical framework (Hallowell, 2011), Clark and Estes's (2008) gap analysis framework, Theory of media ecology (Postman, 1970), Social Exchange Theory, Emancipatory theory of Freire (1986), Callahan's (2011) framework of Power, Conservation of Resources theory (Hobfoll,1989), Theory of Planned Behavior (Ajzen, 1991), Theory of reasoned action (Ajzen and Fishbein, 1980), Tuckman's (1965) model Theory of Group Development, and Drollinger et al. (2006) conceptualization of active empathic listening.

3.5. Antecedents and consequences of incivility in higher education

Ninety-one antecedents and 50 consequences of incivility in higher education were reported in the 119 included studies. Antecedents and consequences of incivility in higher education reported in multiple studies can be seen in Table 3, Table 4. All antecedents and consequences of incivility in higher education reported in both single and multiple studies can be seen in Supplementary File 2 and Supplementary File 3 respectively.

Table 3.

Antecedents of incivility in higher education reported in multiple studies.

| Antecedents | Nursing Education | Other Programs* (specific discipline) |

|---|---|---|

| Stress | 9,18,29,30,31,33,85,95,96, 101,107, 115 | 48, 51, 74(social work), 99(dental hygiene) |

| Faculty incivility | ||

| Faculty behaviors perceived as uncivil; Unengaged faculty; Attitude of faculty superiority, inexperience, faculty pride, lack of empathy and privacy | 7,9,25,29,30,38,109,119 | 14, 34 (psychology), 77,83,86(business) |

| Teaching/pedagogy, boring lectures and classes, poor classroom management, poor teaching methods, inability of nursing faculty to engage students and incorporate technology into the classroom, classroom management and teaching styles | 9,44 | 83 |

| Faculty positive contributions | ||

| Teachers’ positive personal attributes, student-focused teaching, emphasis on classroom practice; Instructor credibility (competence, caring, and trustworthiness); instructor active empathic listening, nonverbal immediacy; teachers’ behavior towards students personally as just | 4,55, 58, 71,111 | |

| Student incivility/contributions | ||

| Uncivil student behaviours | 30,95 | 34 (psychology),83,84,92 |

| Competition | 7,44 | 119 |

| Student entitlement/consumerism | ||

| Student academic entitlement; lack of accountability; not taking responsibility and not being professional | 26,29,31,95,101 | 53,59,60,74(social work),84 |

| Socio demographic | ||

| Gender bias, sex, cultural differences, race, ethnicity | 2,3,7,19,65,85,93,101 | 11,24,37, 39(pharmacy), 64,74(social work), 84,87,110,116 |

| Age; age (over 35 years), older students | 9,54,93,94 | 1, 3,11,85 |

| Years of work experience in current job and institution; work experience of ≥ 10 years | 13,118 | 11,71,110 |

| Faculty status, administrative role | 36,74(social work),110 | |

| Educational level, doctoral degree | 11, 94 | 1 |

| Employed full-time | 8, 94 | |

| Marital status, single | 3,54 | |

| Classroom environment | ||

| Large class size, classroom environment | 9109 | 2,36,52 (social science),83,110,111,116, |

| Social factors | ||

| Immaturity of students, lack of respect for authority, and “the way they were raised”; mirror of society, bad upbringing | 44 | 116,119 |

| Diversity in norms and values among students and teachers and the gap between generations; different social and cultural backgrounds, with varying norms and values | 90,109 | |

| Relationships | ||

| Lack of reciprocal understanding and respect; miscommunication, lack of professionalism | 54 | 48,99(dental hygiene) |

| Leadership | ||

| Obliging conflict management style; hostile interaction style | 11,78(law) | |

| Program commitment and satisfaction | ||

| Satisfaction with major and clinical practice; Job satisfaction | 57 | 51 |

| Work environment | ||

| Unclear roles and expectations, demanding workloads | 31,85 | 74(social work) |

| Personal factors | ||

| Neuroticism, extraversion students with narcissistic tendencies | 51,84 | |

| Resilience | 96,107 | |

| Personality traits and generation gap | 54 | 119 |

Sampled from multiple programs or disciplines.

Table 4.

Consequences of incivility in higher education reported in multiple studies.

| Consequences | Nursing Education | Other Programs* (specific discipline) |

|---|---|---|

| Physiological and psychological negative outcomesa | 15,27,28,32,38,46,62,66,67,68,69, 70,75,76,79,80,89,94,98,100, 101,102,105,114,115 | 22,37,43,45,64,65,99(dental hygiene),103,108,113 |

| Isolation | 15,61 | 22,37 |

| Mental and physical health | 91,94 | |

| Stress | 35,38,91,105,114 | 36,37,43,108,119 |

| Burnout; Instructor emotional exhaustion and work strain | 10 | 53 |

| Program commitment and satisfaction | ||

| Nursing students considering leaving the program; questioning career choice and education | 15,28, 32, 70 | |

| Affected student graduate plans; missed opportunities | 46,67 | 33 |

| Educators wanting to leave job; career longevity; commitment to role and profession, loss of passion for teaching | 49, 68, 85,98,115 | 59,73(dental hygiene) |

| Job Satisfaction | 40,41,76 | 36,78(law) |

| Turnover intention | 40,76,102 | 78(law) |

| Student satisfaction with the institution | 19,72 | 23 |

| Student socialization to higher education | ||

| Hindered student learning experience, learning outcomes, academic performance; decreased student success; negatively influenced professional formation by hindering students' learning, self-esteem, self-efficacy, confidence, and developing identity as nurse | 35,105 | 37, 99(dental hygiene),112(business) |

| Relationships | ||

| Impact on professional relationships (loss of trust, distancing oneself, strained relations, and lost confidence in interactions), Tarnished reputation and credibility; relationship and professional damage; destruction of reputation and teaching credibility, threat to self esteem | 49, 66,100 | |

| Not establishing effective faculty-student relationship | 49, 80,98 | |

| Costs and productivity | ||

| Changes in pedagogy and faculty tendencies to modify grading criteria; dreaded doing tutorials | 27,68 | |

| Financial, emotional, and productivity costs | 66, 68, 98 | |

| Work environment | ||

| feeling unsafe, atmosphere of fear and uncertainty, workplace culture; hostile environment | 27 | 22,99(dental hygiene) |

| Professional formation | ||

| Nursing professional values | 57,82 |

Notea- Negative outcomes include: sleep disturbances, raised blood pressure, dramatic weight loss, respiratory infections, headaches, digestive problems, anxious, inadequate, depressed, fearful, confused, embarrassed, angry, ignored, humiliated, unsafe; feeling traumatized, powerless, helpless, angry, upset, humiliated, belittled, worthless; anxiety, depression; feeling incompetent/stupid; panic attacks; stomach ache and diarrhea; feeling embarrassed, dismissed, devalued; fear, dread, and loathing; altering personality; chest pain.

Sampled from multiple programs or disciplines.

3.5.1. Antecedents of incivility in higher education in multiple studies

The antecedents of incivility in higher education reported in multiple studies were categorized as: Stress, Faculty Incivility, Faculty Positive Contributions, Student Incivility/Contributions, Student Entitlement/Consumerism, Sociodemographic, Classroom Environment, Social Factors, Relationships, Leadership, Program Commitment and Satisfaction, Work Environment, and Personal Factors.

Stress. Stress was reported as an antecedent of incivility in nursing education in 12 studies (9,18,29,30,31,33,85,95,96,101,107,115). Of those, 8 studies reported stress as contributing to nursing student uncivil behaviors (18,29,33,95,96,101,107,115), 2 studies reported stress as contributing to both student and faculty incivility, and 2 studies reported stress as influencing faculty to faculty incivility. In other programs, stress was reported as an antecedent of incivility in 4 studies (48,51,74,99), with 2 studies focusing on students, faculty, and academic staff from across various programs (48), while one study focused on social work faculty perspectives (74), and one study considered dental hygiene students, faculty, and administrators (99).

Faculty Incivility. Faculty Incivility was reported in 9 nursing studies (7,9,25,29,30,38,44,109,119), of which 7 reported faculty incivility as contributing to, triggering, or justifying nursing student uncivil behaviors. In comparison, Faculty Incivility was reported in 5 other program studies (14,34,77,83,86), in which one study reported instructor incivility (i.e., gossiping about students), from the perspective of undergraduate business majors, significantly predicting student incivility.

Faculty Positive Contributions. Faculty credibility, focus on student-centered teaching, positive personal attributes, and just behavior towards students, significantly decreased incivility in 5 other program studies (4,55,58,71,111).

Student Incivility/Contributions. Student incivility and competition amongst students was reported as contributing to student incivility and provoking faculty incivility in 4 nursing studies (7,30,44,95) and 5 other program studies (34,83,84,92,119). One study reported students' attitudes about the appropriateness of uncivil classroom behavior significantly predicted whether they reported engaging in the behaviors (84). Another study reported undergraduate students in a large university were more likely to engage in uncivil behaviors if students believed that most college students engaged in classroom incivilities (92).

Student Entitlement/Consumerism. Student academic entitlement and sense of consumerism contributed to students’ incivility in both nursing (29,95,101) and other program studies (53,59,60,84).

Social Factors. Lack of respect of authority and differing norms and values between faculty and students also influenced the occurrence of student incivility in nursing (44,90,109) and other program studies (116,119).

Sociodemographic. Nursing faculty members’ years of work experience in current job was reported in two studies as significantly increasing the occurrence of incivility (13,118). Increased age of nursing faculty was reported in 2 studies (9,94) as significantly increasing the reporting of incivility in nursing education, and increased age of nursing students was reported as increasing the frequency of incivility experienced by nursing students (93). Meanwhile in other program studies, gender, race, or ethnicity significantly increased perceived incivility (11,24,74, 87).

Classroom Environment. Large class sizes and lectures as antecedents to incivility were reported in 7 other program studies (2,36,52,83,110,111,116) compared to 2 nursing studies (9109).

3.5.2. Consequences of incivility in higher education in multiple studies

The categories of consequences of incivility in higher education reported in multiple studies included: Physiological and Psychological Negative Outcomes, Stress, Program Commitment and Satisfaction, Student Socialization to Higher Education, Relationships, Costs and Productivity, Work Environment, and Professional Formation.

Physiological and Psychological Negative Outcomes. Feeling traumatized, powerless, helpless, angry, upset, humiliated, belittled, worthless; anxiety, depression; feeling incompetent/stupid; panic attacks; stomach-aches and diarrhea; feeling embarrassed, dismissed, devalued; fear, dread, and loathing; altering personality; and chest pain were self-reported by respondents as consequences of incivility in nursing education for both nursing students and nursing faculty in 25 nursing studies (15,27,28,32,38,46,62,66,67,68,70,75,76,79,80,

89,91,94,98,100,101,102,105,114,115). Of those 25 studies, 13 studies reported physiological and psychological negative outcomes of incivility on nursing faculty and educators (15, 27,62,68,75,76,89,94,98,100,101,102,115), 11 studies reported physiological and psychological negative outcomes of incivility on nursing students (28,32,38,46,67,70,79,80,91,105,114), and one study focused on nursing academic administrators (66). Only one nursing study (94) found a significant relationship, using hierarchical multivariate multiple regression, between incivility and decrease in health of nursing faculty. Another study (91) found lower mental health scores of nursing students who experienced peer incivility, using t tests. In comparison, 4 other program studies (23,24,47,78) reported that physiological and psychological negative outcomes were significantly increased by incivility, while 8 qualitative studies reported these negative outcomes of incivility (22,37,43,45,99,103,108,113).

Stress. Nursing students experienced increased levels of stress and burnout as consequences of incivility in six studies (10, 35,38,91,105,114), while stress and burnout for instructors and students were reported as a consequence in 6 other program studies (36, 37,43,53, 108,119).

Program Commitment and Satisfaction. Incivility influenced nursing (49, 68, 85,98,115) and dental hygiene (33) faculty commitment to their jobs and profession. Nursing faculty job satisfaction was significantly decreased as a consequence of incivility (40,41,76), as was for law faculty (78) and faculty from a university (36). Student satisfaction with their institution was significantly decreased by experiences of incivility as reported in two nursing studies (19,72) and 1 other program study (23).

Student Socialization to Higher Education. Incivility negatively influenced professional formation by hindering nursing students' (35,105) and doctoral, business, dental hygiene students’ (37,99,112) learning. Nursing students also considered leaving their programs because of incivility (15,28,32,70) and experiences with incivility affected student future plans for graduate studies for nursing students (46, 67) and healthcare profession students, including nursing students (33).

Relationships. Experiences with incivility affected nursing faculty professional relationships, reputation, and credibility (49,66,100). Effective faculty-student relationships in nursing education programs were also affected by incivility as reported in 3 studies (49,80,98). Nursing faculty (27), administrative staff (22), and dental faculty, students, and administrators (99) felt unsafe in their work environments as a consequence of incivility.

4. Discussion

The large number of studies in this higher education review suggests significant interest and concern about incivility in the scholarly community. It was important to include the broader context of higher education as the breadth of research identified and categorized in this review provides confirmation that incivility in nursing functions much like incivility in other academic areas.

In our review, faculty incivility triggered and even justified student incivility, supporting that incivility is complex, relational, and dynamic. In nursing, a profession centered around caring, the dynamic between faculty and students is particularly relevant. Clark (2008a), an included study in this review, conceptualized incivility between nursing faculty and nursing students as a complex, reciprocal, and dynamic dance: if nursing faculty and students engage and actively listen to one another they are involved in civil interactions or a dance of civility, but if either, or both faculty and students miss or poorly manage opportunities for growth and engagement, then they participate in the dance of incivility. This conceptual model is also applicable to faculty and students in other programs or disciplines as the experience of incivility and contributing factors, such as stress, are not exclusive to nursing (McClendon et al., 2021; Stephens, 2020). The contribution of nursing faculty to the dance of incivility is problematic given the unavoidable power imbalance between nursing faculty and nursing students, and the crucial role nursing faculty play in the socialization of nursing students to the profession of nursing (Del Prato, 2013; Tower-Siddens, 2014). Instead of focusing on changing only nursing student behaviors, it is important to critically examine how nursing faculty contribute to incivility (Butler et al., 2022).

Role modeling of civility by faculty is a crucial element to the establishment and maintenance of civil teaching and learning environments. Role models can act as “behavioral models and representations of the possible and/or inspirations” (Morgenroth et al., 2015, p. 468). Faculty may model for students that civility in higher education is possible and to inspire students to desire engaging in civil interactions. Nursing faculty, for example, can demonstrate enthusiasm and positivity towards nursing education and practice (Baldwin et al., 2014). However, nursing faculty may need support, mentorship, and educational interventions to develop their role modeling abilities. The implementation of formal structured mentorship programs has been argued as especially important for novice nursing faculty who are becoming socialized to academia (Dahlke et al., 2021). Mentors may be able to assist novice faculty in various programs to develop student-focused teaching skills, active listening skills, and other engaging classroom practices to lessen the experiences of student incivility.

Our review findings also suggest that students in higher education engage in a similar dance of incivility with other students, and not only with faculty. Student uncivil behaviors and competition with each other may contribute to further student incivility (Altmiller, 2012; Herrin, 2014; Yassour-Borochowitz and Desivillia, 2016). Nursing students, for example, would benefit from learning to recognize and respond to uncivil behaviors from their peers, such as through the implementation of journal clubs or e-learning modules (Kerber et al., 2012; Palumbo, 2018). Clark (2008a) identified that multiple factors influenced the dance of incivility, which aligns with our findings that stress experienced by students was reported to contribute to student incivility, affecting civil interactions among students. Nursing students may also experience additional stress from the clinical practice environment in which they face a high level of accountability and complex clinical situations. Specific strategies that target stress, such as cognitive behavioral therapy, coping skills, and social support could mitigate the experience of incivility (Yusufov et al., 2019). It is also important to gain a better understanding of the sources of stress through qualitative research. Nurse educators could support students in learning to value, collaborate, and be collegial with their peers while managing conflict, feeling devalued or insecure, and giving and receiving constructive feedback.

Additionally, employing advanced inferential statistical analysis could lend more information on which specific antecedents best explain the occurrence of incivility. Multiple regression, for example, can be used to simultaneously assess the contribution multiple independent variables, or antecedents, make to incivility. Applying multiple regression can help quantify the relationship between each specific antecedent and incivility (Field, 2013). Multiple regression models can also disentangle the effects of confounded variables, such as whether it is the age of nursing faculty or the years of work experience of nursing faculty, that contributes to incivility. Multiple regression models can also provide useful information on the combined strength of the effects of all the independent or predictor variables on a dependent variable like incivility. For example, R2 is a statistical report of the proportion of variance of the dependent variable, like incivility, that can be explained by the cumulative effects of all the included independent or predictor variables. If only a small fraction of the variance in incivility is explained, we would be cautioned that important sources of incivility remain to be discovered. This style of investigation reminds us that the authors of the studies included in this review often claimed variables as antecedents of incivility without providing concrete support that the variables actually are causes or sources of incivility, rather than mere correlates of incivility. While there is substantial evidence of relationships between outcome variables and incivility, and the term ‘consequence’ is also used with comfort, causal links or relationships by referring to these variables as consequences or outcomes often lacks clear support.

Much of the literature, and our views as well, gravitate toward the ‘natural inclination’ to prefer civility and civil interactions. Indeed, nurses are trained to respect and help others, and by default may not necessarily strive to seek alternative explanations beyond the ‘natural inclination’, which is fundamental to research. It would take an “unnatural”, though possibly research-advancing, inclination to momentarily consider that incivility might sometimes be preferred. It would take a real struggle to even-handedly assess an alternative way of viewing civility and incivility, but an unwillingness to engage with difficult or awkward thought may leave researchers less attuned to causal connections appropriate for perceiving and investigating incivility in nursing education. Reflection on the researcher's positionality toward incivility, and clear research support for antecedents of incivility, are warranted.

The range of detrimental consequences of incivility in higher education, especially physiological and psychological negative outcomes, is troubling. Our findings align with extant literature from healthcare delivery settings that report effects of workplace incivility on several work-related outcomes such as job satisfaction, turnover intention, burnout, organizational commitment, psychological distress, job performance, anxiety, cost, and quality of nursing care (Martin and Zadinsky, 2022). Administrators and those in leadership positions in higher education need to be aware of the strength of the effects of incivility on the various physiological and psychological negative outcomes as we develop and implement interventions meant to mitigate the negative effects of incivility. If incivility has a weak effect (that is, if incivility only explains a small proportion of the variance in the negative outcome), then even the most well intentioned and well implanted intervention reducing incivility will only have a weak effect on improving the outcome. The same logic applies to those interventions developed to slow or reduce the causes or sources of incivility. Future research should focus on the development and effectiveness of interventions while paying close attention to the strength of effects. There seems to be insufficient incivility literature that addresses this methodological issue, and hence we do not suggest a statistical-based review, rather we encourage researchers to consider this issue in their future work on incivility.

One statistical method that would be helpful in determining the strength of effects in future research is structural equation modeling. Structural equation modeling incorporates measurement concerns into path-structured models which permits researchers to represent their theoretical understanding in ways which estimate effect sizes and even permit testing (Hayduk, 1987; Hayduk and Littvay, 2012). If a structural equation model in which incivility and other variables function as we theorize, then there is the possibility of understanding the nature and strength of indirect and direct causal relationships among incivility and its contextualizing variables. But structural equation models may fail to match with the data – an outcome encouraging consideration of additional or alternative causal connections, which would contribute precision to future investigations of incivility. The measurement portion of structural equation models provide an obvious opportunity to assess the many ways incivility has been measured, as noted above.

Additionally, examining variables that moderate the effects of incivility on psychological negative outcomes, such as effective leadership, can identify features that may protect either nursing students or nursing faculty from the detrimental effects of incivility (Qui and Zhang, 2022). Given that experiencing psychological negative outcomes may affect health outcomes, such as exacerbating chronic conditions, future research should also examine the cumulative effects of physiological and psychological negative outcomes over time (Barry et al., 2020).

4.1. Measures and theories

Included studies used a variety of measures of incivility of which several were employed across various samples and settings, increasing confidence in the findings of the individual studies. Given the complex, relational, and dynamic nature of incivility, it is promising that the instruments used to measure it attempt to clarify and simplify our understanding of incivility between and among students and faculty. For example, some instruments focused on specific settings for experiences of incivility such as the online environment or the clinical setting. This leads to a greater understanding of which contextual factors may influence incivility. Other measurement instruments assess the multidimensionality of persons involved, such as faculty-to-faculty incivility or student-based experiences, allowing for the representation of unique relational perspectives. However, none of the measurement instruments assess uncivil behaviors that participants themselves ‘receive’ from other individuals or even behaviors they engage in themselves. Rather, the current measurement instruments focus on assessing observed uncivil behaviors only. We recommend that future reviews or studies focus on the comparison of these various measures and whether they are assessing a similar understanding of incivility to ensure our knowledge of incivility is accurate.

Multiple studies also used a variety of theoretical or conceptual frameworks to guide their research on the antecedents or consequences of incivility in higher education. There are too many conceptualizations to even summarize, but a separate review of conceptualization would likely be instructive. Theory is used to “explain, describe, and predict the range of phenomena of interest” (Meleis, 2012, p.125), therefore, grounding research in theory supports a deeper comprehension of the complexity and mechanisms of incivility. In the context of theoretical or conceptual frameworks, we may come to learn more about relationships between and among the influences on and outcomes of incivility. While theoretically inspired research contributes to the cumulative growth of knowledge by building both theory and research, too many unique theoretical perspectives may be redundant as they may ‘cloud’ and introduce inconsistencies into our understanding of incivility. Given the complex nature of incivility and multiple attempts at its comprehension through the application of various theories, our review findings point to the need for theory integration to support a common understanding of the nature of incivility. If existing theories used to study incivility are too heterogeneous for integration, then development and application of novel theoretical approaches may be warranted.

4.2. Study limitations

This review is limited by a potential reporting bias as published studies often over-report positive and significant findings. Inconsistent measurements of incivility in nursing education may limit validity of results. Most studies used qualitative or mixed methods research designs which limit our ability to draw strong conclusions around causal relationships among antecedents, consequences, and incivility. The exclusion of studies in languages other than English might limit our findings to specific cultural or geographical contexts.

5. Conclusion

Through a scoping review of the literature, we identified 119 studies that examined antecedents or consequences of incivility in higher education. Included studies were published between 2003 and 2023 with most conducted in nursing education. Faculty incivility was reported as an antecedent to student incivility, as was competition and incivility among students in higher education. Faculty need support in their development of role modeling civil behaviors. Strategies aimed at decreasing student stress can help to prevent and mitigate the experience of incivility in higher education. Given the degree and range of the physiological and psychological negative outcomes reported in nursing studies included in this review, future research needs to examine both the strength of the effects of these negative outcomes through advanced statistical methods and the cumulative effects of these outcomes over time on both students and faculty. Reviewing and organizing the multitude of conceptualizations of incivility would provide a useful contribution, as would assessing and consolidating the various measures of incivility. Addressing the antecedents of incivility and minimizing the consequences may help to tackle this serious problem not only in nursing education but perhaps in higher education overall.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Tatiana Penconek: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Visualization. Leslie Hayduk: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. Diane Kunyk: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. Greta G. Cummings: Supervision, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources

No external funding.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of Patrick Chiu and Kaitlyn Tate during the screening process and Megan Kennedy with the development of the search strategy.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.ijnsa.2024.100204.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- Ajzen I. Theory of planned behavior. Org. Behav. Hum. Dec. Process. 1991;50:179–211. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I., Fishbein M. Prentice-Hall; Englewood cliffs, NJ: 1980. Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behavior. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Jubouri M.B., Samson-Akpan P., Al-Fayyadh S., Machucas-Contreras F.A., Unim B., Stefanovic S.M., Alabdulaziz H., Oducado R.M.F., George A.N., Ates N.A., Radabutr M., Kamau S., Almazan J. Incivility among nursing faculty: a multi-country study. J. Prof. Nurs. 2020;37(2):379–386. doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2020.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alt D., Itzkovich Y. Assessing the connection between students' justice experience and perceptions of faculty incivility in higher education. J. Acad. Ethics. 2015;13:121–134. [Google Scholar]

- Altmiller G. Student perceptions of incivility in nursing education: implications for educators. Nurs. Educ. Res. 2012;33(1):15–20. doi: 10.5480/1536-5026-33.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson L.M., Pearson C.M. Tit for tat? The spiraling effect of incivility in the workplace. Acad. Manage. Rev. 1999;24(3):452–471. doi: 10.2307/259136. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anthony M., Yastik J., MacDonald D.A., Marshall K.A. Development and validation of a tool to measure incivility in clinical nursing education. J. Prof. Nurs. 2014;30(1):48–55. doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2012.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arksey H., O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ballard R.W., Hagan J.L., Fournier S.E., Townsend J.A., Ballard M.B., Armbruster P.C. Dental student and faculty perceptions of uncivil behavior by faculty members in classroom and clinic. J. Dent. Educ. 2018;82(2):137–143. doi: 10.21815/JDE.018.020e76543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin A., Birks M., Budden L., Mills J. Role modeling in undergraduate nursing education: an integrative literature review. Nurse Educ. Today. 2014;34(6) doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2013.12.007. e18-e26–e26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Prentice Hall; Englewood Cliffs, NJ: 1977. Social Learning Theory. [Google Scholar]

- Barry V., Stout M.E., Lynch M.E., Mattis S., Tran D.Q., Antun A., Ribeiro M.J.A., Stein S.F., Kempton C.L. The effect of psychological distress on health outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. J. Health Psychol. 2020;25(2):227–239. doi: 10.1177/1359105319842931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister R.F. In: Handbook of Theories of Social Psychology. Lange P.A.M.V., Kruglanski A.W., Higgens E.T., editors. Sage Publications Ltd; 2012. Need-to-belong theory; pp. 121–140. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bjorklund W.L., Rehling D.L. Student perceptions of classroom incivility. CollegeTeaching. 2010;58:15–18. [Google Scholar]

- Blake R.R., Mouton J.S. Gulf Publishing; Houston, Texas: 1964. The Managerial Grid. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom E.M. Horizontal violence among nurses: experiences, responses, and job performance. Nurs. Forum. 2019;54:77–83. doi: 10.1111/nuf.12300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolding D.J., Dudley T., Dahlmeier A., Bland L., Castro A., Covarrubias A. Prevalence and types of incivility in occupational therapy fieldwork. J. Occup. Therapy Educ. 2020;4(1) doi: 10.26681/jote.2020.040111. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu P. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, UK: 1972. Outline of a Theory of Practice. [Google Scholar]

- Bower G.H. Mood and memory. Am. Psychol. 1981;36:129–148. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.36.2.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budden L., Birks M., Cant R., Bagley T., Park T. Australian nursing students’ experience of bullying and /or harassment during clinical placement. Collegian. 2017;24(2):125–133. [Google Scholar]

- Butler A.M., Strouse S.M. An integrative review of incivility in nursing education. J. Nurs. Educ. 2022;61(4):173–178. doi: 10.3928/01484834-20220209-01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callahan J. Incivility as an instrument of oppression: exploring the role of power in construction of civility. Adv. Dev. Hum. Resour. 2011;13(1):10–21. doi: 10.1177/1523422311410644. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Casale K.R. Exploring nurse faculty incivility and resonant leadership. Nurs. Educ. Persp. 2017;38(4):177–181. doi: 10.1097/01.NEP.0000000000000171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caza B.B., Cortina L.M. From insult to injury: explaining the impact of incivility. Basic Appl. Soc. Psych. 2007;29:335–350. doi: 10.1080/01973530701665108. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chory R.M., Offstein E.H. The cool professor: instructor personal conduct's influence on student civility and professionalism. Acad. Manage. Annual Meeting Proc. 2014;1:666–671. doi: 10.5465/AMBPP.2014.213. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clark C. The dance of incivility in nursing education as described by nursing faculty and students. Adv. Nurs. Sci. 2008;31(4):E37–E54. doi: 10.1097/01.ANS.0000341419.96338.a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark C.M. Faculty and student assessment of and experience with incivility in nursing education. J. Nurs. Educ. 2008;47(10):458–465. doi: 10.3928/01484834-20081001-03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark C.M., Barbosa-Leiker C., Gill L.M., Nguyen D. Revision and psychometric testing of the incivility in nursing education (INE) survey: introducing the INE-R. J. Nurs. Educ. 2015;54(6):306–315. doi: 10.3928/01484834-20150515-01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark R.E., Estes F. Information Age Publishing; 2008. Turning Research Into Results: A Guide to Selecting the Right Performance Solutions. [Google Scholar]

- Clark C.M., Farnsworth J., Landrum R.E. Development and description of the incivility in nursing education (INE) survey. J. Theory Construct. Test. 2009;13(1):7–15. [Google Scholar]

- Clark C.M., Olender L., Kenski D., Cardoni C. Exploring and addressing faculty-to-faculty incivility: a national perspective and literature review. J. Nurs. Educ. 2013;52(4):211–218. doi: 10.3928/01484834-20130319-01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark C.M., Springer P.J. Thoughts on incivility: student and faculty perceptions of uncivil behavior in nursing education. Nurs. Educ. Perspect. 2007;28(2):93–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark C.M., Werth L., Ahten S. Cyber-bullying and incivility in the online learning environment, Part 1: addressing faculty and student perceptions. Nurse Educ. 2012;37(4):150–156. doi: 10.1097/NNE.0b013e31825a87e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conti-O'Hare M. Jones and Bartlett; 2002. The Nurse as Wounded Healer: From Trauma to Transcendence. [Google Scholar]

- Cortina L.M., Magley V.J., Williams J.H., Langhout R.D. Incivility in the workplace: incidence and impact. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2001;6(1):64–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortina L.M., Kabat-Farr D., Leskinen E.A., Huerta M., Magley V.J. Selective incivility as modern discrimination in organizations: evidence and impact. J. Manage. 2011;39(6) doi: 10.1177/0149206311418835. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Covidence systematic review software (2023). Veritas health innovation, Melbourne, Australia. Available at www.covidence.org.

- Cui S.S., Zhang L., Kong D.h., Chu J. Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the uncivil behavior in clinical nursing education scale. Nurs. J. Chinese PLA. 2017;34(18):21–25. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1008-9993.2017.18.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlke S., Raymond C., Penconek T., Swoboda N. An integrative review of mentoring novice faculty to teach. J. Nurs. Educ. 2021;60(4):203–208. doi: 10.3928/01484834-20210322-04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DalPezzo N.K., Jett K.T. Nursing faculty: a vulnerable population. J. Nurs. Educ. 2010;49(3):132–136. doi: 10.3928/01484834-20090915-04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Prato Students’ voices: the lived experience of faculty incivility as a barrier to professional formation in associate degree nursing education. Nurse Educ. Today. 2013;33(2013):286–290. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2012.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drollinger T., Comer L.B., Warrington P.T. Development and validation of the active-empathetic listening scale. Psychol. Mark. 2006;23:161–180. doi: 10.1002/(ISSN)1520-6793. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elo S., Kyngas H. The qualitative content analysis process. J. Adv. Nurs. 2008;62(1):107–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrell A.H., Provenzano D.A., Spadafora N., Marini Z.A., Volk A.A. Measuring adolescent attitudes toward classroom incivility: exploring differences between intentional and unintentional incivility. J. Psychoeduc. Assess. 2016;34(6):577–588. doi: 10.1177/0734282915623446. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Field A.P. Sage; 2013. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS statistics: and Sex and Drugs and Rock “n” Roll (4th ed.) [Google Scholar]

- Freire P. Continuum; New York: 1986. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. [Google Scholar]

- Hallowell E.M. Harvard Business Review Press; Boston, MA: 2011. Shine: Using Brain Science to Get the Best from Your People. [Google Scholar]

- Hatcher L., Kryter K., Prus J., Fitzgerald V. Predicting college student satisfaction, commitment, and attrition from investment model constructs. J. Appl. Psychol. 1992;22:1273–1296. [Google Scholar]

- Hayduk L. , 1987. Structural Equation Modeling with LISREL. Essentials and Advances. John Hopkins University Press; Baltimore, MD: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Hayduk L., Littvay L. Should researchers use single indicators, best indicator, or multiple indicators in structural equation models? BMC Med. Res. Method. 2012;12:1–17. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-12-159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrin, M.L. (2014). Incivility in nursing education: a study of generational differences (Order No. 3630876). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (1564231902).

- Hobfoll S.E. Conservation of resources: a new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am. Psychol. 1989;44:513–524. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.44.3.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtz H.K., Rawl S.M., Drauker C. Types of faculty incivility as viewed by students in bachelor of science in nursing programs. Nurs. Educ. Perspect. 2018;29(2):85–90. doi: 10.1097/01.NEP.0000000000000287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingraham K.C., Davidson S.J., Yonge O. Student-faculty relationships and its impact on academic outcomes. Nurse Educ. Today. 2018;71(2018):17–21. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2018.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo S.O., Oh J. Validity and reliability of the Korean version of a tool to measure uncivil behavior in clinical nursing education. J. Korean Acad. Soc. Nurs. Educ. 2016;22(4):537–548. doi: 10.5977/jkasne.2016.22.4.537. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kerber C., Jenkins S., Woith W., Kim M. Journal clubs: a strategy to teach civility to nursing students. J. Nurs. Educ. 2012;51(5):277–282. doi: 10.3928/01484834-20120323-02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lampman C., Phelps A., Bancroft S., Beneke M. Contrapower harassment in academia: a survey of faculty experience with student incivility, bullying, and sexual attention. Sex Roles: A J. Res. 2009;60(5–6):331–346. doi: 10.1007/s11199-008-9560-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus R.S. McGraw-Hill; New York, NY: 1966. Psychological Stress and the Coping Process. [Google Scholar]

- Levac D., Colquhoun H., O'Brien K.K. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement. Sci. 2010;5:69. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewin K. Harper & Brothers; New York, NY: 1951. Field Theory in Social Science: Selected theoretical Papers. [Google Scholar]

- Luparell S. The effects of student incivility on nursing faculty. J. Nurs. Educ. 2007;46(1):15–19. doi: 10.3928/01484834-20070101-04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchiondo K., Marchiondo L.A., Lasiter S. Faculty incivility: effects on program satisfaction of BSN students. J. Nurs. Educ. 2010;49(11):608–614. doi: 10.3928/01484834-20100524-05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin R.J., Hine D.W. Development and validation of the uncivil workplace behavior questionnaire. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2005;10(4):477–490. doi: 10.1037/1076-8998.10.4.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin L.D., Zadinsky J.K. Frequency and outcomes of workplace incivility in healthcare: a scoping review of the literature. J. Nurs. Manage. 2022;30(7):3496–3518. doi: 10.1111/jonm.13783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maslach C., Leiter M.P. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco, CA: 1997. The Truth About Burnout: How Organizations Cause Personal Stress and What to Do About It. [Google Scholar]

- McClendon J., Lane S.R., Flowers T.D. Faculty-to-faculty incivility in social work education. J. Soc. Work Educ. 2021;57(1):100–112. doi: 10.1080/10437797.2019.1671271. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meleis A.I. Lippincott; Philadelphia: 2012. Theoretical nursing: Development and Progress (5th ed.) [Google Scholar]

- Morgenroth T., Ryan M.K., Peters K. The motivational theory of role modeling: how role models influence role aspirants’ goals. Rev. General Psychol. 2015;19(4):465–483. doi: 10.1037/gpr0000059. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Natarajan J., Muliira J.K., van der Colff J. Incidence and perception of nursing students' academic incivility in Oman. BMC Nurs. 2017;16:1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12912-017-0213-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nutt C.M. Olivet Nazarene University; Bourbonnais, Illinois: 2013. Stop the Madness! College Faculty and Student Perceptions of Classroom Incivility. [Google Scholar]

- Palumbo R. Incivility in nursing education: an intervention. Nurse Educ. Today. 2018;66:143–148. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2018.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel S.E., Chrisman M. Incivility through the continuum of nursing: a concept analysis. Nurs. Forum. 2020;55(2):267–274. doi: 10.1111/nuf.12425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pondy L.R. Organization conflict: concepts and models. Adm. Sci. Q. 1967;12:296–320. [Google Scholar]

- Postman N. In: High School 1980: The Shape of the Future in American Secondary Education. Eurich A.C., editor. Pitman Publishing Corporation; New York, NY: 1970. The reformed English curriculum; pp. 160–168. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu S., Zhang R. The relationship between workplace incivility and psychological distress: the moderating role of servant leadership. Workplace Health Saf. 2022;70(10):459–467. doi: 10.1177/21650799221084067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens, K. (2020). An Evaluation of Incidence and Perceptions of Incivility among Dental Hygiene Students and Faculty/Administrators (Order No. 28086388). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (2437402177).

- Todd D., Byers D., Garth K. A pilot study examining the effects of faculty incivility on nursing program satisfaction. BLDE Univ. J. Health Sci. 2016;1:9–13. [Google Scholar]

- Tuckman B.W. Developmental sequence in small groups. Psychol. Bull. 1965;63(6):384–399. doi: 10.1037/h0022100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salin D. Ways of explaining workplace bullying: a review of enabling, motivating and precipitating structures and processes in the work environment. Hum. Relations. 2003;56(10):1213–1232. [Google Scholar]

- Small S.P., English D., Moran G., Grainger P., Cashin G. Mutual respect would be a good starting point: students’ perspectives on incivility in nursing education. Can. J. Nurs. Res. 2019;51(3):133–144. doi: 10.1177/0844562118821573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tower-Siddens, R. (2014). The relationship between incivility and learning: a study of how students interpret the affects of faculty incivility on student learning achievements (Order No. 3628732).

- Wagner B., Holland C., Mainous R., Matcham W., Li G., Luiken J. Differences in perceptions of incivility among disciplines in higher education. Nurse Educ. 2019;44(5):265–269. doi: 10.1097/NNE.0000000000000611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson J. 2nd ed. Jones and Bartlett; Boston, MA: 2012. Human Caring Science. [Google Scholar]

- Yassour-Borochowitz D., Desivillia H. Incivility between students and faculty in an Israeli college: a description of the phenomenon. Int. J. Teach. Learn. Higher Educ. 2016;28(3):414–426. [Google Scholar]

- Yusufov M., Nicoloro-SantaBarbara J., Grey N.E., Moyer A., Lobel M. Meta-analytic evaluation of stress reduction interventions for undergraduate and graduate students. Int. J. Stress. Manage. 2019;26(2) doi: 10.1037/str0000099. 132-145–145. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.