Abstract

Bacterial spores resist antibiotics and sterilization and can remain metabolically inactive for decades. Nevertheless, bacterial spores can rapidly germinate and resume growth in response to nutrients. Broadly conserved receptors embedded in the spore membrane detect nutrients, but how spores transduce these signals remains unclear. Here, we found that these receptors form oligomeric membrane channels. Mutations predicted to widen the channel initiated germination in the absence of nutrients, while those that narrow it prevented ion release and germination in response to nutrients. Expressing receptors with widened channels during vegetative growth caused loss of membrane potential and cell death whereas addition of germinants to cells expressing wild-type receptors triggered membrane depolarization. Thus germinant receptors act as nutrient-gated ion channels such that ion release initiates exit from dormancy.

Summary:

Ligand-gated ion channels release cations in response to nutrients to initiate exit from spore dormancy.

Bacteria in the orders Bacillales and Clostridiales cause over a million infections each year and are responsible for huge monetary losses to the food industry (1, 2). These bacteria resist antibiotics and sterilization by entering a highly durable spore state (3). Spores are metabolically inactive and can remain dormant for decades. Upon exposure to nutrients, spores rapidly resume growth and can cause food spoilage, food-borne illness, or life-threatening disease. The exit from dormancy, called germination, is a key target in combatting these pathogens. The germination program of most spore-forming bacteria involves a common series of chemical steps and a small set of broadly conserved factors (4, 5). GerA-family receptors embedded in the spore membrane are required for sensing amino acids, sugars, and/or nucleosides. Nutrient detection leads to the release of mono- and divalent cations from the spore core, which is rapidly followed by the expulsion of large stores of dipicolinic acid (DPA) via the SpoVA transport complex (6, 7). DPA release activates cell wall hydrolases that degrade the specialized peptidoglycan that encases the spore, allowing core rehydration, macromolecular synthesis, and resumption of growth. The prototypical germinant receptor, GerA, in Bacillus subtilis is composed of three broadly conserved subunits GerAA, GerAB, and GerAC (8). GerAB is responsible for L-alanine recognition and genetic evidence suggests nutrient detection by GerAB is communicated to the GerAA subunit (9, 10). How this signal triggers germination and exit from dormancy remains unclear (11).

To elucidate the germination process further we examined the communication between GerA and the DPA transporter SpoVA. We reasoned that if GerA communicates with SpoVA via a protein-protein contact, germination signal transduction would be broken if SpoVA were substituted with a homolog that was unable to maintain this contact. We expressed the Bacillus cereus spoVA operon (spoVA1) in B. subtilis with the expectation that the heterologous transporter (~70% identical, Fig. S1A) would not be activated by the B. subtilis germination signal transduction pathway. Instead, B. subtilis spores harboring the SpoVA1 transporter and lacking the native spoVA locus released DPA and germinated in response to L-alanine in a manner similar to wild-type (Fig. 1A, S2–4). Similar results were obtained with a different B. cereus spoVA locus (spoVA2, ~56% identical) and the Clostridiodes difficile spoVA operon (~46% identical) (Fig. 1A and S1–4). Notably, C. difficile belongs to the small subset of spore formers that lacks GerA-family receptors (8, 12). These findings suggested that activation of SpoVA by GerA-family receptors is not mediated by protein-protein interactions and instead involves some chemical or physical change to the spore. To further test this idea, we performed a reciprocal experiment in which we expressed the Bacillus megaterium GerA-family receptor GerUV (Fig. S1B) (13) in a B. subtilis strain lacking all its native germinant receptors. These spores activated DPA release and germinated in response to GerUV’s cognate germinants D-glucose, L-leucine, L-proline, and K+ but not in response to L-alanine (Fig. 1B and S3).

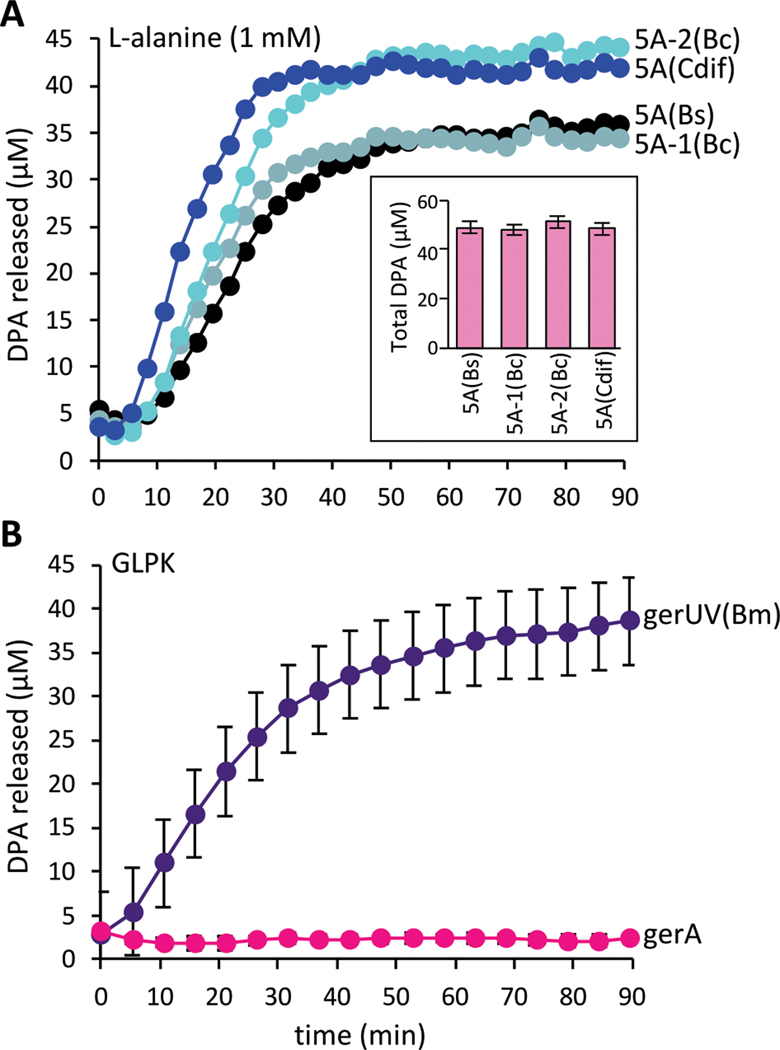

Figure 1. Cross-species complementation of key germination factors.

(A) spoVA loci from B. cereus and C. difficile support DPA release from B. subtilis spores in response to L-alanine. Purified spores of ΔspoVA mutant strains harboring an ectopic copy of the indicated spoVA (5A) locus from B. subtilis (Bs), B. cereus (Bc), or C. difficile (Cdif). Spores were mixed with 1 mM L-alanine and DPA release was monitored over time. The insert shows total DPA content in purified spores. Representative data from one of three biological replicates are shown. The other two replicates can be found in Figure S2. (B) B. subtilis spores harboring the gerUV locus from B. megaterium germinate in response to D-glucose, L-leucine, L-proline and K+ (GLPK). Purified B. subtilis spores lacking all 5 endogenous germinant receptor loci (Δ5) and harboring the gerUV or gerA locus were incubated with GLPK (10 mM each) and DPA release was monitored over time. The data represent the average results from three biological replicates. Error bars are the standard deviations from the means. Similar results were obtained using a germination assay that monitors the drop in optical density as phase-bright spores transition to phase-dark (Fig. S3 and S4).

The GerA complex is predicted to oligomerize into membrane channel

The release of cations from the spore core is the first measurable event during germination, but the molecular basis for ion release and its role in exit from dormancy have been unclear (14, 15). Based on the cross-species complementation results described above, we hypothesized that GerA-family receptors trigger DPA export and exit from dormancy by releasing cations. GerAA and GerAB are polytopic membrane proteins and GerAC is a lipoprotein (4); a conserved set of glycine residues in transmembrane (TM) helix 3 in GerAA potentially indicated that these proteins might act as ion channels (Fig. 2A). Conserved glycine patches have been observed in the luminal helices of other ion channels, where they facilitate tight oligomeric packing (16). Accordingly, we investigated whether GerAA could multimerize using AlphaFold-Multimer (17–19). Indeed, AlphaFold predicted that GerAA could form a high-confidence pentamer with a membrane channel formed by TM helix 3 (Fig. 2B and S5). Separately, AlphaFold also predicted that GerAC could form a pentamer (Fig. S5C) and that the GerAA-GerAB-GerAC trimer could dimerize with a packing angle of ~69˚, consistent with a pentameric complex (Fig. S6). GerAA-GerAB-GerAC trimers could be superimposed upon all five protomers of the GerAA and GerAC pentamers without clashes (Fig. 2D and S7–8). Furthermore, the ligand-binding pockets in the GerAB subunits were accessible to exogenous nutrients in the fully assembled complex (Fig. S7C). All AlphaFold models were supported by low inter-residue distance errors (pTM > 0.75) and strong per-residue accuracy estimates (pLDDT > 85) (Fig. S5). Thus, our modeling suggests that the GerA complex consists of a pentameric arrangement of heterotrimers (15 subunits total) that form a transmembrane channel.

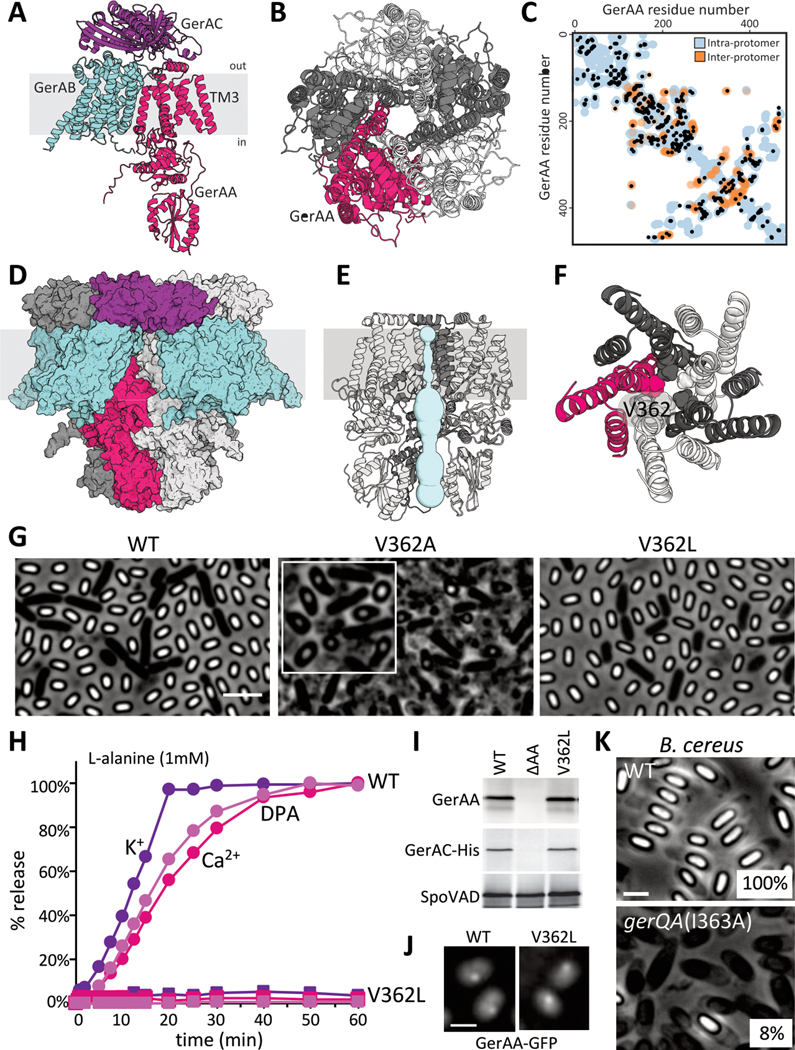

Figure 2. Evidence that GerAA forms a membrane channel.

(A) Predicted structure of the GerAA (red), GerAB (cyan), GerAC (purple) trimer. Topology is based on protease accessibility studies of GerAC and GerAA (10, 38). TM3, the lumen-adjacent helix in GerAA is labeled. (B) Predicted GerAA pentamer as viewed from outside the spore. Protomers are shown in dark and light gray and red. (C) Evolutionarily coupled (EC) residue pairs in GerAA are plotted as black circles. Intra-protomer (blue circles) and inter-protomer (orange circles) residue pairs that are ≤5 Å apart in the predicted GerAA pentamer are shown. (D) Space-filling model of the predicted pentamer of trimers. (E) Predicted pore (light blue) in the GerAA pentamer. Only three GerAA protomers are shown for clarity. (F) Top view of the GerAA hexamer model showing the concentric TM rings surrounding the channel. V362 is highlighted. (G) Representative phase-contrast images of sporulated cultures of strains harboring a second copy of gerAA(WT) or gerAA(V362A). The strain harboring gerAA(V362L) lacks the native gerAA copy. Scale bar, 3 μm. Inset highlights the teardrop-shaped spores in the V362A mutant. (H) Purified spores that have GerAA(WT) (circles) or GerAA(V362L) (squares) as the sole copy of the GerAA subunit were mixed with 1 mM L-alanine and the germination exudates were analyzed for K+, Ca2+, and DPA over time. (I) Immunoblots from lysates of the purified spores used in (H). GerAA(WT) and GerAA(V362L) are stable and stabilize GerAC-His, unlike spores lacking GerAA (ΔAA). SpoVAD controls for loading. (J) Representative fluorescence images of GerAA(WT)- and GerAA(V362L)-GFP localization in spores. Both localize in germinosome foci. Scale bar, 3 μm. (K) Representative phase-contrast images of sporulated cultures of wild-type B. cereus and a merodiploid strain harboring gerQA(I363A). Sporulation efficiency of each strain is indicated in the bottom right. Scale bar, 2μm. Representative data from one of at least three biological replicates are shown for (G), (H), (J), (K), and from one of two biological replicates for (I).

Further support for this oligomeric model comes from evolutionary co-variation analysis (20), wherein directly interacting amino acids tend to co-evolve and evolutionarily coupled (EC) residue pairs are generally close to each other in tertiary structure. Several high-confidence EC residue pairs within GerAA (Fig. 2C) and GerAC (Fig. S9) were distant from each other within individual protomers but could be fully explained by intermolecular contacts in the oligomeric model (Fig. 2C and S9, orange circles). Similarly, several EC residue pairs between GerAA and GerAB subunits and between GerAB and GerAC subunits were not satisfied by the predicted GerAA-GerAB-GerAC trimer but could be explained by intermolecular contacts in the predicted pentamer of trimers (Fig. S9). All detected EC residue pairs within GerAB appeared to be intramolecular contacts (Fig. S9), consistent with the observation that GerAB protomers did not contact each other in the predicted pentameric arrangement (Fig. 2D and S7).

The predicted membrane channel formed by the GerAA pentamer is lined with hydrophilic residues, contains a stereotypical glycine patch, and has dimensions similar to those of previously characterized ligand-gated ion channels (Fig. 2E and S10) (16, 21, 22). Furthermore, acidic residues are enriched at the periphery of the channel, suggesting cation selectivity (Fig. S10C). Intriguingly, pentameric ligand-gated ion channels (pLGICs) constitute a large family of neurotransmitter receptors that includes the cation-selective nicotinic acetylcholine receptor and the anion-selective gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptor (21). Although evolutionarily unrelated, these neurotransmitter receptors and the GerAA oligomer share a common channel-forming structural motif, comprising a three-helix bundle that, with symmetry, traces two concentric rings around the pore axis (Fig. 2F and S10B) (23, 24).

GerA complexes function as membrane channels

The GerA structural prediction was bolstered by an unbiased genetic screen. The screen identified hyperactive gerAA alleles that constitutively trigger germination. We PCR-mutagenized gerAA and screened for dominant mutants with defects in spore maturation (Fig. S11A). The three strongest mutants identified caused premature germination and pervasive lysis during spore formation (Fig. 2G and S11CD). The few unlysed spores had teardrop shapes, suggesting a severe defect in morphogenesis. All three mutants had amino acid substitutions in or adjacent to TM helix 3 (Fig. S11B), one of which (V362A) was predicted to face directly into the lumen of the channel (Fig. 2F). In the context of the structural model, this conservative substitution would widen the channel and potentially maintain it in an open state. To test this, we separately substituted leucine 358 (Fig. S11B), which is also predicted to be in TM helix 3 and face the lumen of the channel, with alanine. GerAA(L358A) similarly caused premature germination with teardrop-shaped spores (Fig. S11CD). To investigate whether narrowing the channel would impair GerAA function, we substituted valine 362 with leucine. Upon exposure to L-alanine spores harboring GerAA(V362L) were unable to release monovalent ions, DPA and its Ca2+ chelate, and failed to rehydrate as assayed by optical density (Fig. 2H and S12–13). We conclude that the V362L mutation fully impaired germination. The GerAA(V362L) protein was stable in spores and maintained the stability of GerAC (Fig. 2I and S13C), suggesting that the mutant subunit assembled into germination complexes (10, 25). GerAA(V362L), like GerAA(WT), also localized in clusters called germinosomes (26) in the spore membrane (Fig. 2J and S13D), further arguing that the mutant protein was properly assembled into germination receptor complexes but incapable of transducing nutrient signals. Leucine substitutions at two other positions in GerAA’s TM helix 3 (Q354 and Q366) that were also predicted to face the lumen of the channel behaved similarly to GerAA(V362L) in all the assays described above (Fig. S12 and S13).

All A subunits in the GerA family that we analyzed using AlphaFold-Multimer were predicted to form pentameric membrane channels. The GerQA subunit encoded in the B. cereus gerQ operon (27) has an isoleucine at position 363 in TM helix 3 that is analogous to V362 in GerAA (Fig. S14A). Introduction of gerQA(I363A) into B. cereus caused premature germination during sporulation and a reduction in spore viability (Fig. 3K and S14B). Thus, most GerA-family receptors, including those from pathogenic organisms, are likely to function as channels.

GerA complexes act as nutrient-gated ion channels

To investigate whether the GerA complex releases ions, we expressed GerAB and GerAC in exponentially growing B. subtilis cells and placed wild-type gerAA and gerAA(V362A) under the control of an isopropyl β-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG)-regulated promoter. Cells expressing GerAA(V362A) were not viable (Fig. 3A and S15). Loss of viability was GerAB- and GerAC-dependent (Fig. 3A and 3B), consistent with the requirement of a fully assembled GerA complex for toxic activity. Similar results were obtained with the other constitutively active gerAA alleles (Fig. S16). Inducible growth defects have been reported for mechanosensitive channel mutants that are locked in an open state (28, 29), suggesting that GerAA(V362A)-GerAB-GerAC complexes cause constitutive ion release. To investigate this possibility, we monitored the loss of membrane potential using the potentiometric fluorescent dye 3,3′-Dipropylthiadicarbocyanine iodide [DiSC3(5)] (30). Within 10 min after inducing gerAA(V362A), we detected a drop in DiSC3(5) fluorescence, which decreased further over the next 30 min (Fig. 3C and S17). Membrane permeability defects, assayed with propidium iodide, occurred ~80 min after gerAA(V362A) induction (Fig. 3C and S17). We observed no membrane integrity defects or depolarization when GerAA(WT) was expressed with GerAB and GerAC nor when GerAA(V362A) was expressed in their absence (Fig. 3C and S17). Addition of 50 mM L-alanine to cells expressing GerAA(WT), GerAB, and GerAC caused a 30% reduction in DiSC3(5) fluorescence (Fig. 3DE and S18). No reduction was observed when equimolar concentrations of L-alanine and the germinant-competitive inhibitor D-alanine (31) were added together (Fig. S18). Furthermore, L-alanine did not reduce membrane potential when added to cells expressing the channel-narrowing GerAA(V362L) mutant or a GerAB mutant (G25A) in the ligand-binding pocket that does not respond to L-alanine (Fig. 3DE, S18–20) (10). Thus, the GerA complex acts as a nutrient-gated ion channel.

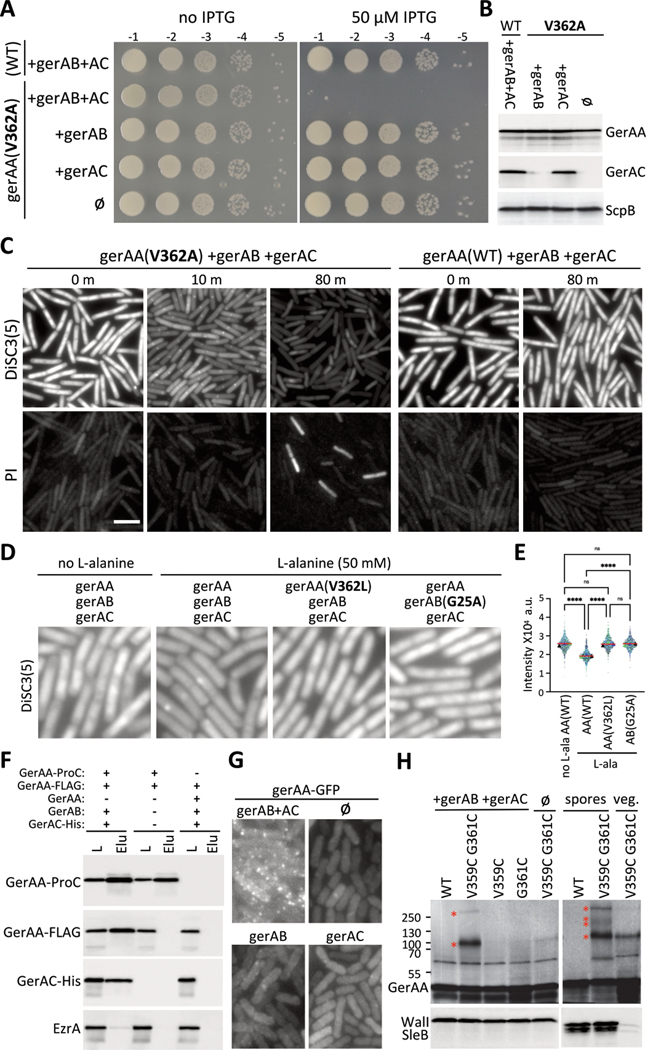

Figure 3. The GerA complex behaves like a nutrient-gated ion channel when expressed in vegetatively growing cells.

(A) Serial dilutions of the indicated strains with IPTG-regulated gerAA(WT) and gerAA(V362A) alleles and constitutively expressed gerAB and gerAC (AC). (B) Immunoblot analysis of the strains in (A). GerAA(WT) and GerAA(V362A) were expressed at similar levels in the presence or absence of GerAB and GerAC. ScpB controls for loading. (C) Representative fluorescence images of exponentially growing cultures of the indicated strains from (A). Time (in min) after IPTG addition is indicated. The top panels show fluorescence of the potentiometric dye DiSC3(5). The lower panels show propidium iodide (PI) staining. The two fields are from the same culture but stained and imaged separately. Scale bar, 5 μm. (D) Representative DiSC3(5) fluorescence images of exponentially growing cultures of the indicated strains 30 min after addition of 50 mM L-alanine. gerAA and gerAA(V362L) are IPTG-regulated alleles and gerAB, gerAB(G25A) and gerAC were expressed constitutively. (E) Quantitative analysis of DiSC3(5) fluorescence intensity from the same strains and conditions as in (D). DiSC3(5) fluorescence intensities were quantified from three biological replicates (>500 cells for each) and plotted in different colors. Triangles represent the median fluorescence intensity for each replicate, red lines show the median values for all cells per strain. P-value <0.0001 (****) and not significant (ns) are indicated. (F) Immunoblots of anti-ProC immuno-affinity purifications from detergent-solubilized membrane preparations of vegetatively growing B. subtilis cells expressing the indicated proteins. Load (L) and elution (Elu) are shown. GerAA-FLAG co-purifies with GerAA-ProC, provided GerAB and GerAC are co-expressed. The membrane protein EzrA serves as a negative control. (G) Representative fluorescence images of vegetative cells expressing GerAA-GFP in the presence and absence of GerAB and GerAC (AC). (H) Immunoblots of vegetative cells expressing cysteine-substituted GerAA variants in the presence or absence of GerAB and GerAC. GerAA(V359C G361C) produces disulfide species (red asterisks) with sizes of dimer and pentamer (left). WalI controls for loading. GerAA species of similar size were also detected from spore lysates (right). Two additional species were also detected. SleB controls for loading. Representative data from one of at least three biological replicates are shown for (A), (C-E), (G) and (H). (B) and (F) are from one of two biological replicates.

GerAA multimerizes in vivo

We used our vegetative GerA expression system to investigate whether GerAA subunits mutlimerize in vivo. First, we performed immunoprecipitation experiments from detergent-solubilized membranes derived from cells co-expressing functional GerAA-ProteinC (GerAA-ProC) and GerAA-FLAG fusions (Fig. S21). Anti-ProC resin efficiently co-precipitated GerAA-ProC and GerAA-FLAG provided GerAB and GerAC were also expressed (Fig 3F), indicating that at least two GerAA subunits reside in these membrane complexes. In a complementary set of experiments, we generated functional fluorescent fusions to GerAA (Fig. S21) that formed discrete fluorescent foci that depended on GerAB and GerAC (Fig. 3G and S22). Increasing expression of GerAA-mYpet resulted in an increase in the number of foci rather than an increase in the fluorescence intensity of individual foci, suggesting that each focus is a discrete oligomeric complex rather than a nonspecific aggregate (Fig. S23). Multimerization of GerAA in vivo was further supported by experiments in sporulating cells expressing equivalent levels of GerAA(WT) and GerAA(V362L) (Fig. S24A). The channel-blocking mutant was strongly dominant-negative for spore germination, arguing that GerAA(V362L) assembles into complexes with GerAA(WT) and poisons their function (Fig. S24). For comparison, the merodiploid spores were more severely impaired in DPA release and germination than spores with a gerAA allele that produced >8-fold lower levels of wild-type GerAA (Fig. S24).

As a final in vivo test of the AlphaFold-predicted GerA oligomer, we engineered cysteine substitutions in GerAA at positions predicted to reside within 5 Å of each other in adjacent TM3 channel helices (Fig. S25A). These variants were expressed in vegetative cells and then analyzed by immunoblot. We observed two high molecular weight GerAA species of approximately 100 and 250 kDa, consistent with a dimer and a pentamer (Fig. 3H). Both species were observed in the absence of exogenous chemical crosslinking reagents and were stable in the presence of SDS and β-mercaptoethanol but not tributyl phosphine, as expected for disulfide bonds within TM segments (32) (Fig. S24B). The 250 kDa species was only detected when both cysteines were present in GerAA and when co-expressed with GerAB and GerAC (Fig. 3H). Furthermore, species of identical sizes were observed when the cysteine-substituted GerAA variant was analyzed from dormant spores (Fig. 3H). Two additional species were detectable, albeit weakly, in the spore lysate that could represent GerAA trimers and tetramers, which could have resulted from incompletely oxidized pentamers.

Discussion

Our data support a model in which L-alanine detection by GerAB subunits in the GerA complex act cooperatively to induce a conformational change in the GerAA subunits, which in turn opens the transmembrane channel and allows cation release. That the B. subtilis GerA receptor can trigger DPA expulsion by the B. cereus and C. difficile SpoVA transporters and reciprocally the B. megaterium GerUV receptor can trigger DPA export by B. subtilis SpoVA further argue that ion release by GerA-family receptors activates the SpoVA complex and ultimately spore germination.

A Na+/H+-K+ antiporter in B. cereus, GerN, is required for spore germination in response to inosine (33). B. cereus spores lacking gerN are impaired in ion release and subsequent germination when exposed to inosine, but respond normally to L-alanine. GerN is not broadly conserved among spore formers and is absent in B. subtilis (33). Furthermore, no ion transporters have been found in B. cereus that are required for spores to respond to L-alanine (34), and analysis of remote homologs of GerN and other putative ion transporters present in the B. subtilis spore inner membrane have failed to identify analogous transporters required for germination (14) (Fig. S26). Nonetheless, the studies on B. cereus GerN provide foundational evidence that cation release is required in the germination signal transduction pathway. The data presented here are consistent with these studies and suggest that the link between ion release and germination is not the exception, but rather the rule. Indeed, our work suggests that in most cases, GerA-family complexes function as the principal germination-initiating ion channels.

Our finding that GerA receptors are ligand-gated ion channels provides a mechanistic explanation for how a transient pulse of L-alanine could trigger a pulse of K+ release, as was recently proposed to explain how spores retain the memory of a previous exposure to nutrients (35). In this model, germination is only triggered when the intracellular K+ concentration drops below a threshold value and each transient exposure to nutrients incrementally reduces ion concentration until this threshold is reached. Although we favor the idea that the SpoVA transport complex is activated to release DPA when intracellular K+ concentrations drop below a threshold value, the memory model proposed by Suel and co-workers cannot account for previous observations that the memory of an exposure to nutrients is lost over time (36, 37). This short-term memory can, however, be explained by the requirement for L-alanine to bind multiple, if not all, GerAB subunits in the pentameric complex to trigger ion release. If a transient pulse of L-alanine results in partial occupancy, and dissociation is slow, the subsequent pulse could more readily achieve full occupancy and open the GerAA channel. This model is consistent with the different rates of memory loss observed for different nutrient stimuli and the faster memory loss when spores are incubated at high temperature between germinant pulses (36).

It is noteworthy that ~4.2% of all sequenced germinant receptor operons encode two or more B subunits in addition to single A and C subunits (8). In the case of the B. megaterium gerUV locus, the two B subunits (GerUB and GerVB) can each function without the other provided that their shared A and C subunits are present (13). These data suggest that different B subunits could assemble into a single pentameric receptor. Because B subunits function in nutrient detection, these mixed pentamers could integrate distinct nutrient signals in the environment.

In summary, our data indicate that GerA-family receptors assemble into a family of pentameric ligand-gated ion channels that transduce germinant signals by releasing cations, which activates SpoVA complexes to expel DPA from the spore core. DPA release triggers degradation of the spore cortex peptidoglycan and exit from dormancy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

All three co-first authors made foundational discoveries and contributed equally to this work. L.A. formulated the key hypothesis that GerAA could multimerize into an ion channel. We thank Irina Shlosman, Assaf Alon and all members of the Bernhardt-Rudner super-group, for helpful advice, discussions, and encouragement, Andrea Vettiger and the HMS Microscopy Resources on the North Quad (MicRoN) core for advice on microscopy and analysis, the Center for Environmental Health Sciences Bioanalytical Core Facility at MIT for access to their ICP-MS. Portions of this research were conducted on the O2 High Performance Computing Cluster, supported by the Research Computing Group, at Harvard Medical School.

Funding:

Support for this work comes from the National Institute of Health Grants GM086466, GM127399, GM122512, AI171308 (DZR), AI164647 (DZR, ACK, DSM) and funds from the Harvard Medical School Dean’s Initiative. JDA was funded by National Institutes of Health grant F32GM130003. LA was a Simons Foundation fellow of the Life Sciences Research Foundation.

Footnotes

Competing interests:

The authors declare no competing interests. DSM is a cofounder of Seismic Therapeutics, an advisor for Dyno Therapeutics, Octant, Jura Bio, Tectonic Therapeutics and Genentech.

Data and materials availability:

All data are available in the manuscript or the supplementary materials.

References and Notes:

- 1.Andre S, Vallaeys T, Planchon S, Spore-forming bacteria responsible for food spoilage. Res Microbiol 168, 379–387 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mallozzi M, Viswanathan VK, Vedantam G, Spore-forming Bacilli and Clostridia in human disease. Future Microbiol 5, 1109–1123 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Setlow P, Spore Resistance Properties. Microbiol Spectr 2, (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moir A, Cooper G, Spore Germination. Microbiol Spectr 3, (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Setlow P, Wang S, Li YQ, Germination of Spores of the Orders Bacillales and Clostridiales. Annu Rev Microbiol 71, 459–477 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gao Y. et al. , The SpoVA membrane complex is required for dipicolinic acid import during sporulation and export during germination. Genes Dev 36, 634–646 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vepachedu VR, Setlow P, Role of SpoVA proteins in release of dipicolinic acid during germination of Bacillus subtilis spores triggered by dodecylamine or lysozyme. J Bacteriol 189, 1565–1572 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paredes-Sabja D, Setlow P, Sarker MR, Germination of spores of Bacillales and Clostridiales species: mechanisms and proteins involved. Trends Microbiol 19, 85–94 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Amon JD, Artzi L, Rudner DZ, Genetic Evidence for Signal Transduction within the Bacillus subtilis GerA Germinant Receptor. J Bacteriol 204, e0047021 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Artzi L. et al. , Dormant spores sense amino acids through the B subunits of their germination receptors. Nat Commun 12, 6842 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Trowsdale J, Smith DA, Isolation, characterization, and mapping of Bacillus subtilis 168 germination mutants. J Bacteriol 123, 83–95 (1975). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Francis MB, Allen CA, Shrestha R, Sorg JA, Bile acid recognition by the Clostridium difficile germinant receptor, CspC, is important for establishing infection. PLoS Pathog 9, e1003356 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Christie G, Lowe CR, Role of chromosomal and plasmid-borne receptor homologues in the response of Bacillus megaterium QM B1551 spores to germinants. J Bacteriol 189, 4375–4383 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen Y. et al. , Membrane Proteomes and Ion Transporters in Bacillus anthracis and Bacillus subtilis Dormant and Germinating Spores. J Bacteriol 201, (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Swerdlow BM, Setlow B, Setlow P, Levels of H+ and other monovalent cations in dormant and germinating spores of Bacillus megaterium. J Bacteriol 148, 20–29 (1981). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bass RB, Strop P, Barclay M, Rees DC, Crystal structure of Escherichia coli MscS, a voltage-modulated and mechanosensitive channel. Science 298, 1582–1587 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Evans R. et al. , Protein complex prediction with AlphaFold-Multimer. bioRxiv, 2021.2010.2004.463034 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jumper J. et al. , Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 596, 583–589 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mirdita M. et al. , ColabFold: making protein folding accessible to all. Nat Methods 19, 679–682 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hopf TA et al. , The EVcouplings Python framework for coevolutionary sequence analysis. Bioinformatics 35, 1582–1584 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nemecz A, Prevost MS, Menny A, Corringer PJ, Emerging Molecular Mechanisms of Signal Transduction in Pentameric Ligand-Gated Ion Channels. Neuron 90, 452–470 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Uysal S. et al. , Crystal structure of full-length KcsA in its closed conformation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106, 6644–6649 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Unwin N, Refined structure of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor at 4A resolution. J Mol Biol 346, 967–989 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhu S. et al. , Structure of a human synaptic GABA(A) receptor. Nature 559, 67–72 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mongkolthanaruk W, Cooper GR, Mawer JS, Allan RN, Moir A, Effect of amino acid substitutions in the GerAA protein on the function of the alanine-responsive germinant receptor of Bacillus subtilis spores. J Bacteriol 193, 2268–2275 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Griffiths KK, Zhang J, Cowan AE, Yu J, Setlow P, Germination proteins in the inner membrane of dormant Bacillus subtilis spores colocalize in a discrete cluster. Mol Microbiol 81, 1061–1077 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barlass PJ, Houston CW, Clements MO, Moir A, Germination of Bacillus cereus spores in response to L-alanine and to inosine: the roles of gerL and gerQ operons. Microbiology (Reading) 148, 2089–2095 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maurer JA, Elmore DE, Lester HA, Dougherty DA, Comparing and contrasting Escherichia coli and Mycobacterium tuberculosis mechanosensitive channels (MscL). New gain of function mutations in the loop region. J Biol Chem 275, 22238–22244 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ou X, Blount P, Hoffman RJ, Kung C, One face of a transmembrane helix is crucial in mechanosensitive channel gating. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95, 11471–11475 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Te Winkel JD, Gray DA, Seistrup KH, Hamoen LW, Strahl H, Analysis of Antimicrobial-Triggered Membrane Depolarization Using Voltage Sensitive Dyes. Front Cell Dev Biol 4, 29 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Woese CR, Morowitz HJ, Hutchison CA 3rd, Analysis of action of L-alanine analogues in spore germination. J Bacteriol 76, 578–588 (1958). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kirley TL, Inactivation of (Na+,K+)-ATPase by beta-mercaptoethanol. Differential sensitivity to reduction of the three beta subunit disulfide bonds. J Biol Chem 265, 4227–4232 (1990). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thackray PD, Behravan J, Southworth TW, Moir A, GerN, an antiporter homologue important in germination of Bacillus cereus endospores. J Bacteriol 183, 476–482 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Senior A, Moir A, The Bacillus cereus GerN and GerT protein homologs have distinct roles in spore germination and outgrowth, respectively. J Bacteriol 190, 6148–6152 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kikuchi K. et al. , Electrochemical potential enables dormant spores to integrate environmental signals. Science 378, 43–49 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.. Wang S, Faeder JR, Setlow P, Li YQ, Memory of Germinant Stimuli in Bacterial Spores. mBio 6, e01859–01815 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang P, Liang J, Yi X, Setlow P, Li YQ, Monitoring of commitment, blocking, and continuation of nutrient germination of individual Bacillus subtilis spores. J Bacteriol 196, 2443–2454 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wilson MJ, Carlson PE, Janes BK, Hanna PC, Membrane topology of the Bacillus anthracis GerH germinant receptor proteins. J Bacteriol 194, 1369–1377 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zeigler DR et al. , The origins of 168, W23, and other Bacillus subtilis legacy strains. J Bacteriol 190, 6983–6995 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schaeffer P, Millet J, Aubert JP, Catabolic repression of bacterial sporulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 54, 704–711 (1965). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Koo BM et al. , Construction and Analysis of Two Genome-Scale Deletion Libraries for Bacillus subtilis. Cell Syst 4, 291–305 e297 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Meeske AJ et al. , MurJ and a novel lipid II flippase are required for cell wall biogenesis in Bacillus subtilis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112, 6437–6442 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pravda L. et al. , MOLEonline: a web-based tool for analyzing channels, tunnels and pores (2018 update). Nucleic Acids Res 46, W368–W373 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hopf TA et al. , Three-dimensional structures of membrane proteins from genomic sequencing. Cell 149, 1607–1621 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Marks DS et al. , Protein 3D structure computed from evolutionary sequence variation. PLoS One 6, e28766 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Johnson LS, Eddy SR, Portugaly E, Hidden Markov model speed heuristic and iterative HMM search procedure. BMC Bioinformatics 11, 431 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ducret A, Quardokus EM, Brun YV, MicrobeJ, a tool for high throughput bacterial cell detection and quantitative analysis. Nat Microbiol 1, 16077 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ramirez-Peralta A, Zhang P, Li YQ, Setlow P, Effects of sporulation conditions on the germination and germination protein levels of Bacillus subtilis spores. Appl Environ Microbiol 78, 2689–2697 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stewart KA, Yi X, Ghosh S, Setlow P, Germination protein levels and rates of germination of spores of Bacillus subtilis with overexpressed or deleted genes encoding germination proteins. J Bacteriol 194, 3156–3164 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vepachedu VR, Setlow P, Localization of SpoVAD to the inner membrane of spores of Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol 187, 5677–5682 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rudner DZ, Losick R, A sporulation membrane protein tethers the pro-sigmaK processing enzyme to its inhibitor and dictates its subcellular localization. Genes Dev 16, 1007–1018 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fujita M, Temporal and selective association of multiple sigma factors with RNA polymerase during sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. Genes Cells 5, 79–88 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang X, Tang OW, Riley EP, Rudner DZ, The SMC condensin complex is required for origin segregation in Bacillus subtilis. Curr Biol 24, 287–292 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Szurmant H, Fukushima T, Hoch JA, The essential YycFG two-component system of Bacillus subtilis. Methods Enzymol 422, 396–417 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bernhards CB, Popham DL, Role of YpeB in cortex hydrolysis during germination of Bacillus anthracis spores. J Bacteriol 196, 3399–3409 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Levin PA, Kurtser IG, Grossman AD, Identification and characterization of a negative regulator of FtsZ ring formation in Bacillus subtilis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96, 9642–9647 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ghosh S. et al. , Characterization of spores of Bacillus subtilis that lack most coat layers. J Bacteriol 190, 6741–6748 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ramirez-Guadiana FH, Meeske AJ, Wang X, Rodrigues CDA, Rudner DZ, The Bacillus subtilis germinant receptor GerA triggers premature germination in response to morphological defects during sporulation. Mol Microbiol 105, 689–704 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Li Y. et al. , Structure-based functional studies of the effects of amino acid substitutions in GerBC, the C subunit of the Bacillus subtilis GerB spore germinant receptor. J Bacteriol 193, 4143–4152 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Li Y. et al. , Structural and functional analyses of the N-terminal domain of the A subunit of a Bacillus megaterium spore germinant receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 116, 11470–11479 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gharpure A. et al. , Agonist Selectivity and Ion Permeation in the alpha3beta4 Ganglionic Nicotinic Receptor. Neuron 104, 501–511 e506 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nicolas P. et al. , Condition-dependent transcriptome reveals high-level regulatory architecture in Bacillus subtilis. Science 335, 1103–1106 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zheng L. et al. , Bacillus subtilis Spore Inner Membrane Proteome. J Proteome Res 15, 585–594 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data are available in the manuscript or the supplementary materials.