ABSTRACT.

Disseminated cysticercosis is defined by multiple brain lesions and involvement of other body sites. Cysticidal treatment in disseminated cysticercosis is considered life-threatening. We conducted a systematic review of all published cases and case series to assess the safety and efficacy of cysticidal treatment. We conducted a systematic review in accordance with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (PROSPERO CRD42022331895) to assess the safety and efficacy of cysticidal treatment. Using the search term “disseminated neurocysticercosis OR disseminated cysticercosis,” databases like PubMed, Scopus, Embase, and Google Scholar were searched. Outcomes included death and secondary measures like clinical improvement and lesion reduction. We calculated the predictors of primary outcome (death) using the binary logistic regression analysis. We reviewed 222 published cases from 101 publications. Approximately 87% cases were reported from India. Of 222 cases, 134 (60%) received cysticidal treatment. Follow-up information was available from 180 patients, 11 of them died, and 169 showed clinical improvement. The death rate was 4% (5 out of 114) in patients treated with cysticidal drugs plus corticosteroids, in comparison with 13% (5 out of 38) in patients who were treated with corticosteroids alone. All patients using only praziquantel faced fatality. Death predictors identified were altered sensorium and lack of treatment with albendazole. We noted that the risk of death after cysticidal treatment is not as we expected, and a multicentric randomized controlled trial is needed to resolve this issue.

INTRODUCTION

Taenia solium, a tapeworm, causes human taeniasis/cysticercosis. Its larval stages can infect the central nervous system, leading to neurocysticercosis. In disseminated cysticercosis, cysticercal larvae are distributed throughout the body. In disseminated cysticercosis, skin, eyes, muscles, heart, and rarely lungs are affected.1

Disseminated cysticercosis is a condition known since ancient time. Disseminated cysticercosis has even been described in a mummified Egyptian woman from the 25th Dynasty. A computed tomogram showed numerous tiny calcific nodules, creating a “starry night” pattern. The same speckled pattern in the woman’s spinal cord and heart indicates a disseminated stage of the parasitic disease.2

Although cysticidal treatments like albendazole and praziquantel have shown effectiveness in treating neurocysticercosis, these studies typically involve patients with only 1–20 viable cysts. For patients with one or two viable parenchymal cysticerci, albendazole monotherapy for 10–14 days is recommended over no antiparasitic therapy or combination therapy. However, for patients with more than two viable parenchymal cysticerci, a combination of albendazole (15 mg/kg/day) and praziquantel (50 mg/kg/day) for 10–14 days is favored over using only albendazole.3,4 While acknowledging the lack of definitive evidence, WHO guidelines advise against the use of anthelmintic drugs in patients with numerous parenchymal cysts causing inflammation and elevated intracranial pressure due to widespread edema or hydrocephalus. In such cases, experts generally recommend the use of corticosteroids alone to manage pronounced inflammation.5 Cysticidal treatment in disseminated cysticercosis can exacerbate cerebral edema, making cysticidal treatment unsuitable for those with heightened intracranial pressure due to widespread cerebral edema (known as cysticercal encephalitis) or untreated hydrocephalus.6–9

Nonetheless, some isolated cases have indicated that cysticidal treatment can be both safe and effective in disseminated cysticercosis. We conducted a systematic review of all documented isolated cases and case series of disseminated cysticercosis to assess the safety and efficacy of cysticidal treatment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We performed an extensive search and documentation of published case reports and case series involving disseminated cysticercosis. We focused specifically on the safety and efficacy of cysticidal treatment. For the systematic review, we adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. The methodology was recorded in PROSPERO with the reference number CRD42022331895.10

Search strategy.

We searched PubMed, Scopus, Embase, and Google Scholar databases. For the Google Scholar database, we limited our search to the initial 50 pages. We did not apply any language constraints while searching these databases. For articles not originally in English, we used Google Translate to render them in English. The search term we used was “disseminated neurocysticercosis OR disseminated cysticercosis”. The last search was done on February 28, 2023.

All case reports, case series, and cohort studies, if individual patient data were available, were included in the review.

Eligibility criteria.

Patients of any age or gender diagnosed with disseminated cysticercosis were included in this review. Disseminated cysticercosis was defined as the presence of multiple cystic/enhancing lesions in the brain, along with evidence of involvement of at least one extra site, like subcutaneous tissues, skeletal muscles, eyes, and presence in any visceral organ (such as liver, lung, spleen, or heart).

Intervention.

Cysticidal treatment in the form of either albendazole or praziquantel alone or in combination was considered the intervention.

Comparator.

Not receiving cysticidal treatment was considered the control.

Outcome.

Primary outcome.

Death was considered the primary outcome.

Secondary outcome.

Clinical improvement as considered by the primary author, seizure control and improvement in headache as considered by the primary author, reduction of lesion load on neuroimaging, and adverse events as reported by the primary author were considered the secondary outcome measures.

Study selection.

Two reviewers independently (I. Rizvi and R. K. Garg) selected the studies based on the above-mentioned criteria, and any disagreement was resolved by mutual discussion. Selection of studies was performed in two steps. In the first step, the two reviewers independently screened titles and abstracts. In the second step, full articles of the selected studies were obtained. Any subsequent exclusion was recorded with a relevant reason. Duplicate records were managed using the EndNote 20 web tool. Two reviewers (I. Rizvi and R. K. Garg) independently conducted the duplicate removal process. Any issues that arose were resolved with the assistance of another reviewer (H. S. Malhotra).

Data extraction.

Data extraction was performed independently by two reviewers (I. Rizvi and R. K. Garg), and any disagreement was sorted out by mutual discussion. Data were extracted onto a Microsoft Excel sheet. A predetermined data extraction sheet was used for data extraction. Data for individual patients such as age, gender, symptoms, seizure frequency, headache, altered sensorium, lesion count, sites of dissemination, type of cysticidal treatment, dose and duration of cysticidal treatment, type and dose of corticosteroids used, follow-up duration, and outcome such as death, seizure reduction, headache reduction, adverse events, and lesion load reduction were extracted.

Data synthesis and analysis.

We were not able to perform a meta-analysis, as most of the included studies were in the form of case reports. The authors used different treatment regimens, and there was much variability in outcome assessment and follow-up period; therefore, a formal head-to-head comparison and meta-analysis were not possible. We extracted the data and tabulated them in the form of numbers and percentages. The number and percentage of patients experiencing an outcome was determined in each treatment group. We calculated the predictors of primary outcome (death) using the binary logistic regression, the occurrence of death was taken as the dependent variable, and baseline clinical features, age, and treatment given were taken as independent variables. Only those cases for which the information regarding the outcome was clearly available were included in the analysis. SPSS version 24.0 was used to perform the analysis.

Risk of bias (quality) assessment.

The quality of the included case reports was assessed under four domains: selection, ascertainment, causality, and reporting.11 If the case report met all of the domain criteria, it was categorized as “good quality.” If it fulfilled three of the domain criteria, it was deemed “fair quality,” and if it met only one or two domain criteria, it was rated as “poor quality.”12

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics.

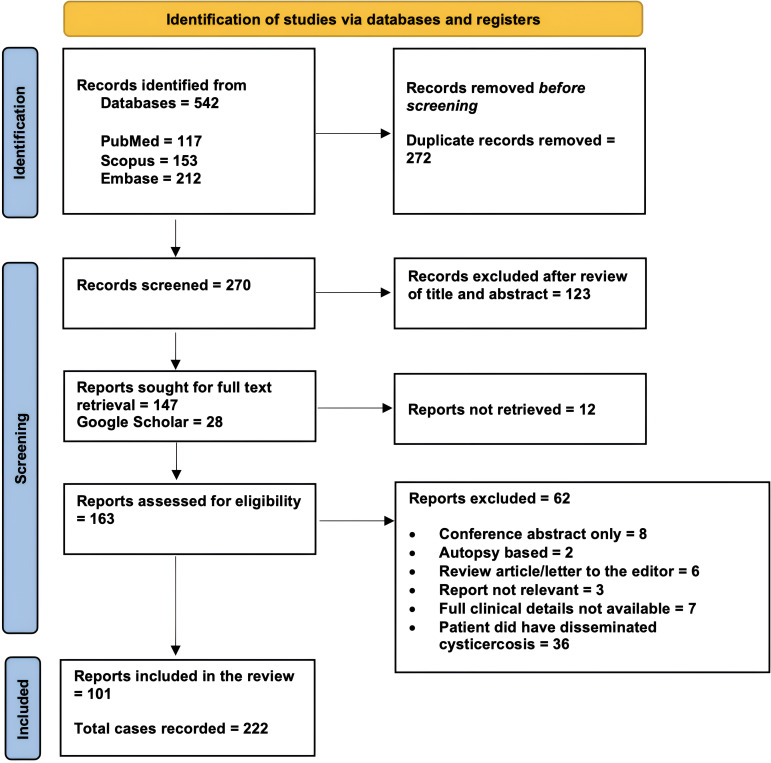

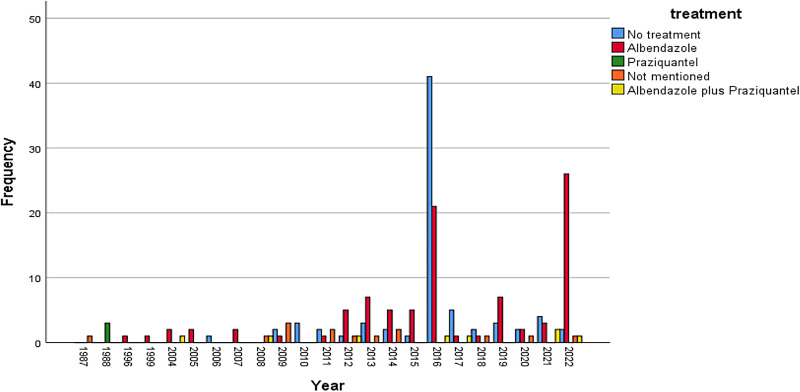

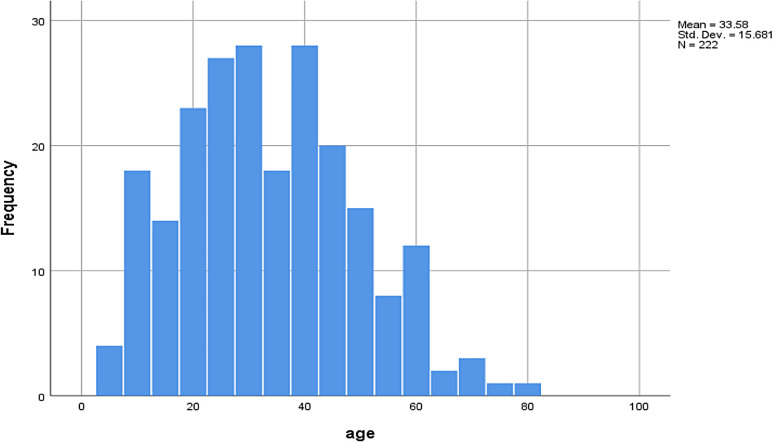

Our search resulted in 101 reports with information on 222 individual cases (Figures 1 and 2). The mean age of the patients was 33.6 ± 15.7 years, and the majority (186/222; 84%) were male (Figure 3). Most of the cases were reported from India (192/222; 87%). The reasons for excluding reports from analysis have been provided in Figure 1. Approximately 89% of case reports were of either good or fair quality (Supplemental Table).

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram of the study showing the process of article selection for systematic review.

Figure 2.

Bar diagram depicting year-wise distribution of number of reported cases of disseminated neurocysticercosis.

Figure 3.

Histogram demonstrating age distribution of the patients with disseminated neurocysticercosis.

Clinical features.

Seizures and subcutaneous nodules were the most prevalent clinical features, observed in 165 of the 222 cases and accounting for 74% each. Headaches were also a common symptom, reported in 61% (136 of 222) of the cases. Other frequently reported clinical signs included muscle enlargement, eye protrusion (proptosis), fever, and altered consciousness (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the 222 patients with disseminated NCC

| Variable | Value |

|---|---|

| Age in years | |

| Mean ± SD | 33.58 ± 15.7 |

| Median (IQR) | 32 (23) |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Male | 186 (84) |

| Female | 36 (16) |

| Country, n (%) | |

| India | 192 (87) |

| China | 6 (3) |

| Brazil | 4 (2) |

| USA | 4 (2) |

| South Africa | 3 (1) |

| Others | 13 (6) |

| Clinical features, n (%) | |

| Headache | 136 (61) |

| Seizure | 165 (74) |

| Altered sensorium | 42 (19) |

| Fever | 14 (6) |

| Vision loss | 46 (21) |

| Muscle enlargement | 116 (52) |

| Subcutaneous nodules | 165 (74) |

| Proptosis | 65 (29) |

| Site of dissemination, n (%) | |

| Eye | 98 (44) |

| Skin/subcutaneous tissue | 165 (74) |

| Muscle | 159 (72) |

| Heart/lung/visceral organ | 38 (17) |

| Neuroimaging findings, n (%) | |

| Multiple brain lesions | 222 (100) |

| Cystic/vesicular lesion | 193 (87) |

| Calcified lesions | 36 (16) |

| Scolex | 107 (48) |

| Cysticidal treatment, n (%) | |

| Only albendazole | 123 (55) |

| Albendazole plus praziquantel | 08 (4) |

| Praziquantel alone | 03 (1) |

| Cysticidal treatment not given | 74 (33) |

| Not mentioned | 14 (6) |

| Corticosteroids, n (%) | |

| Given | 170 (77) |

| Not given | 35 (16) |

| Not mentioned | 17 (7.7) |

| Treatment regimens, n (%) | |

| Cysticidal drugs plus steroid | 125 (56) |

| Only steroid | 45 (20) |

| Cysticidal drug without steroid | 06 (3) |

| Neither drug nor steroid | 29 (13) |

| Not mentioned | 17 (8) |

IQR = interquartile range; NCC, neurocysticercosis.

Sites of dissemination.

The most frequent sites of extracranial dissemination of neurocysticercosis were the skin and subcutaneous tissues and the muscles, noted in 74% (165/222) and 72% (159/222) of cases, respectively. Ocular involvement occurred in 44% of cases (98/222). The heart, lungs, and other visceral organs were affected in 17% of cases (38/222) (Table 1).

Neuroimaging findings.

Each of the 222 patients (100%) demonstrated multiple neurocysticercosis lesions. A cystic/vesicular stage was most commonly reported, seen in 193 (87%) cases. Calcified lesions were seen in 36 (16%) cases (Table 1).

Treatment.

Cysticidal therapy was administered to 60% (134/222) of the patients. Of these, 123 received albendazole. A combination of albendazole and praziquantel was prescribed for eight (4%) patients. Praziquantel alone was used in three (1%) patients. Treatment was not provided to 33% of the patients (74/222). Additionally, details regarding cysticidal therapy were not available for 14 cases (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Histogram depicting treatment option used in patients with disseminated neurocysticercosis.

The most common dosage of albendazole used was 15 mg/kg, although four patients received albendazole at a dose of 20 mg/kg. The duration of treatment was quite variable. Twenty-nine (13%) patients were given albendazole for 28 days, and this cycle was repeated three times. Thirty-nine patients were treated with albendazole for 28 days, and 16 patients were treated for 14 days. Three cycles of 10 days each were given to two patients, four cycles of 10 days each were given to two patients, and one patient got albendazole for 90 days.

A total of 170 of 222 patients (77%) were given corticosteroids. In 125 (56%) patients, a combination of corticosteroids and cysticidal drug was used. Forty-five (20%) patients received corticosteroids alone. Sixty-five patients got prednisolone, 69 got methylprednisolone, 29 were given dexamethasone, and three received betamethasone (Table 1).

Follow-up and outcome assessment.

The follow-up period varied. In many cases, clear follow-up details were not available. The follow-up period ranged from 0 days to 7 years (median, 180 days).

Information regarding outcome was available for 180 patients: 11 of them died, while the remaining 169 showed clinical improvement. Information regarding control of epileptic seizures was available for 141 cases: epileptic seizures were controlled in 135 of them. Information regarding improvement in headache was available for 118 cases: 102 of them showed improvement during follow-up. Follow-up neuroimaging was available in 130 cases, and 94 of them were reported to have a reduction in lesion load (Tables 2 and 3).

Table 2.

Outcome observed in patients receiving different cysticidal drugs

| Outcome | Albendazole Only | Albendazole Plus Praziquantel | Praziquantel Only | Cysticidal Drug not Given |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome 1: Death (data available for 180 patients), n (%) | n = 113 | n = 7 | n = 3 | n = 57 |

| Death | 2 (2) | 0 (0) | 3 (100) | 6 (11) |

| Alive | 111 (98) | 7 (100) | 0 (0) | 51 (89) |

| Outcome 2: Clinical improvement (data available for 180 patients), n (%) | n = 113 | n = 7 | n = 3 | n = 57 |

| Clinical improvement | 111 (98) | 7 (100) | 0 (0) | 51 (89) |

| No improvement | 2 (2) | 0 (100) | 3 (100) | 6 (11) |

| Outcome 3: Seizure control (data available for 141 patients), n (%) | n = 90 | n = 1 | n = 3 | n = 47 |

| Seizures controlled | 88 (98) | 1 (100) | 1 (33) | 45 (96) |

| Seizures not controlled | 2 (2) | 0 (0) | 2 (67) | 2 (4) |

| Outcome 4: Improvement in headache (data available for 118 patients), n (%) | n = 78 | n = 4 | n = 2 | n = 34 |

| Headache improved | 66 (85) | 4 (100) | 0 (0) | 32 (94) |

| Headache not improved | 12 (15) | 0 (0) | 2 (100) | 2 (6) |

| Outcome 5: Reduction in lesion load (data available for 130 patients), n (%) | n = 92 | n = 3 | n = 3 | n = 32 |

| Lesion load reduced | 80 (87) | 3 (100) | 1 (33) | 10 (31) |

| Lesion load not reduced | 12 (13) | 0 (0) | 2 (67) | 22 (69) |

Table 3.

Outcomes segregated by different treatment regimes

| Outcome | Cysticidal Treatment along with Steroids | Cysticidal Drugs without Steroids | Only Steroids | Neither Steroid nor Cysticidal Drug | Not Mentioned |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome 1: Death (N = 180), n (%) | n = 114 | n = 6 | n = 38 | n = 19 | n = 3 |

| Death | 5 (4) | 0 (0) | 5 (13) | 1 (5) | 0 (0) |

| Alive | 109 (96) | 6 (100) | 33 (87) | 18 (95) | 3 (100) |

| Outcome 2: Clinical improvement (N = 180), n (%) | n = 114 | n = 6 | n = 38 | n = 19 | n = 3 |

| Clinical improvement | 109 (96) | 6 (100) | 33 (87) | 18 (95) | 3 (100) |

| No improvement | 5 (4) | 0 (0) | 5 (13) | 1 (5) | 0 (0) |

| Outcome 3: Seizure control (N = 141), n (%) | n = 88 | n = 6 | n = 29 | n = 18 | n = 0 |

| Seizures controlled | 85 (97) | 5 (83) | 28 (97) | 17 (94) | 0 |

| Seizures not controlled | 3 (3) | 1 (17) | 1 (3) | 1 (6) | 0 |

| Outcome 4: Improvement in headache (N = 118), n (%) | n = 79 | n = 4 | n = 25 | n = 9 | n = 1 |

| Headache improved | 66 (84) | 3 (75) | 24 (96) | 8 (89) | 1 (100) |

| Headache not improved | 13 (16) | 1 (25) | 1 (4) | 1 (11) | 0 (0) |

| Outcome 5: Lesion load reduction on neuroimaging (N = 130), n (%) | n = 92 | n = 5 | n = 17 | n = 15 | n = 1 |

| Lesion load reduced | 79 (86) | 4 (80.0) | 7 (41) | 3 (20.0) | 1 (100) |

| Lesion load not reduced | 13 (14) | 1 (20.0) | 10 (59) | 12 (80.0) | 0 (0) |

Outcomes with different treatment regimens.

The various outcomes observed according to the treatment regimens are summarized in Tables 2 and 3. Only 2% (2/113) patients died among those who received albendazole, in comparison with 11% (6/57) deaths among patients who did not receive any cysticidal drugs. None of the patients who received albendazole along with praziquantel died. All three patients who were treated with praziquantel alone died. The death rate was 4% (5/114) in patients treated with cysticidal drugs plus corticosteroids, in comparison with 13% (5/38) in patients who were treated with corticosteroids alone (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Histogram depicts year-wise number of disseminated neurocysticercosis cases stacked as per outcome. Std. Dev. = standard deviation.

Clinical improvement was observed in 98% (111/113) of patients who received albendazole and in 100% (7/7) of patients who received a combination of albendazole and praziquantel, in comparison with improvement rates of 90% (51/57) among patients who did not receive any cysticidal drugs. The clinical improvement rate was 96% (109/114) in patients who received cysticidal drugs along with corticosteroids, in comparison with 87% (33/38) in patients who were treated with corticosteroids alone.

Seizure control was achieved in 98% (88/90) of patients who were treated with albendazole, in comparison with 96% (45/47) of patients who were not given cysticidal drugs. The seizure control rate was 97% (85/88) when cysticidal drugs were given along with corticosteroids, and the seizure control rate was 97% (28/29) in patients who were treated with corticosteroids alone.

The lesion load was reduced in 87% (80/92) of patients treated with albendazole and in 100% of patients treated with albendazole plus praziquantel. The lesion load was reduced in only 31% (10/32) of patients who did not receive any cysticidal drug. The lesion load reduction was observed in 86% (79/92) of patients who received cysticidal treatment along with corticosteroids, while the lesion load was reduced in only 41% (7/17) of patients who were treated with corticosteroids alone (Tables 2 and 3).

Predictors of death.

Upon univariate analysis, the presence of altered sensorium at baseline (P = 0.001, odds ratio = 9.63; 95% CI, 2.63–35.23) and treatment with albendazole alone (P = 0.001, odds ratio = 0.096; 95% CI, 0.02–0.46) were the factors found to be significantly associated with death.

Binary logistic regression analysis was performed to determine the predictors of death. Only 180 patients for whom outcome information was available were included in the analysis. Occurrence of death was taken as the dependent variable, and factors found to be significant on univariate analysis were taken as the independent variables.

Altered sensorium at presentation was found to be associated with poor outcome (P = 0.002, odds ratio = 9.01, 95% CI, 2.21–36.78). Treatment with albendazole was found to be negatively associated with poor outcome (P = 0.008, odds ratio = 0.107, 95% CI, 0.02–0.55).

Other adverse events.

After cysticidal treatment, 16 of 222 (7%) patients reported adverse reactions to the drug.7,13–22 Eleven of them were treated with albendazole, three of them were treated with praziquantel monotherapy, and two were treated with a combination of the two drugs. Three of these 16 patients died (all three were treated with praziquantel monotherapy), and the rest of the 13 patients improved during follow-up. One patient died in the hospital after developing worsening of the sensorium, epileptic seizures, and breathlessness after the third dose of praziquantel. One other patient died after 6 weeks after developing worsening of the sensorium, swelling of limbs, and worsening of proptosis after treatment. One patient developed cerebral edema on day 3, but he improved after stopping praziquantel and receiving steroids; this patient remained well for 8 months and then died as a result of status epilepticus (Table 4).

Table 4.

Details of 16 patients who developed adverse events after starting treatment

| Reference | Year | Patient Details | Cysticidal Treatment | Steroid | Type of Reaction | Final Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wadia et al.7 | 1988 | 23-year-old male with dementia, seizure, and muscle enlargement | Praziquantel | Not given initially; steroid was given after patient developed reaction | Cerebral edema developed on day 3; urticaria and decreased sensorium; these reactions subsided after cysticidal treatment was stopped and steroids were given | Clinical improvement and decrease in lesions initially; death after 8 months |

| Wadia et al.7 | 1988 | 17-year-old female with seizure, altered sensorium, nodules, and muscle enlargement | Praziquantel | Yes, prednisolone | After third dose, breathlessness, restlessness, seizures, worsening of sensorium, and death | Death in hospital |

| Wadia et al.7 | 1988 | 9-year-old male with seizures, altered sensorium, and proptosis | Praziquantel | Yes, dexamethasone | Seizures, decrease in sensorium, swelling of limbs, worsening of proptosis, and death over next 6 weeks | Death after 6 weeks |

| Kumar et al.13 | 1996 | 11-year-old male with mental decline, vision loss, proptosis, and muscle enlargement | Albendazole | Yes, dexamethasone | Deterioration of sensorium and recurrent focal seizures | Clinical improvement over 3 months, reduction in number of brain lesions |

| Foyaca-Sibat et al.14 | 2004 | 42-year-old male with seizures, muscle enlargement, and nodules | Albendazole plus praziquantel | Yes, prednisolone | Muscle pain | Clinical improvement and reduction of brain lesions; seizure controlled |

| Prasad et al.15 | 2012 | 7-year-old male with headache, vision loss, nodules, proptosis, and muscle hypertrophy | Albendazole | Yes, prednisolone | Transient deterioration of sensorium | Clinical improvement |

| Dhar et al.16 | 2013 | 40-year-old male with seizure, altered sensorium, and fever | Albendazole | Yes | Anaphylactic shock | Clinical improvement |

| Kobayashi et al.17 | 2013 | 31-year-old male with subcutaneous nodules | Albendazole | Yes, prednisolone | Fever, headache, and tenderness of nodules on day 3 | Clinical improvement and reduction of brain lesions |

| Duvignaud et al.18 | 2014 | Subcutaneous nodules | Albendazole | Yes, prednisolone | Transient eosinophilia and pericystic inflammatory reaction | Reduction in brain lesions |

| Mouhari-Toure et al.19 | 2015 | 50-year-old male with seizures and nodules | Albendazole | Yes, betamethasone | Seizures on day 8 | Clinical improvement, seizure free, disappearance of nodules |

| Mouhari-Toure et al.19 | 2015 | 50-year-old male with seizures and nodules | Albendazole | Yes, betamethasone | Seizures on day 25 | Disappearance of nodules, clinical improvement |

| Heller et al.20 | 2017 | 41-year-old female with seizures and subcutaneous nodules | Albendazole plus praziquantel | Yes, prednisolone | Severe headache, body aches, and vomiting | Clinical improvement, reduction in nodules |

| Zou et al.21 | 2019 | 18-year-old female with headache, fever, and reduced vision | Albendazole | Yes, dexamethasone | Acute inflammatory reaction (other details not mentioned); reaction subsided on giving increased dose of steroid | Clinical improvement and reduction of lesions over 6 months |

| Zou et al.21 | 2019 | 24-year-old male with headache and reduced vision in left eye | Albendazole | Yes, dexamethasone | Severe headache on day 3; improved with increased dose of steroids | Radiological reduction of lesions over 6 months |

| Zou et al.21 | 2019 | 42-year-old male with seizures and reduced vision in right eye | Albendazole | Yes, dexamethasone | Severe epilepsy on day 3; improved with increased dose of steroids | Radiological reduction of lesions over 6 months |

| Pandey et al.22 | 2020 | 52-year-old male with headache, seizures | Albendazole | Yes, methylprednisolone | Mild itching | Clinical improvement, reduction of seizures and brain lesions |

DISCUSSION

We noted that of 180 patients for whom follow-up information was available, only 11 of them died. Among those who received albendazole, the death rate was 2%. In contrast, the mortality rate among patients who did not receive any cysticidal drugs was 11%. The death rate was 4% in patients treated with cysticidal drugs plus corticosteroids, compared with 13% in patients who were treated with corticosteroids alone.

We noted that epileptic seizures and headaches were the most common clinical presentations in patients with disseminated neurocysticercosis. In Europe, a review of cases from 2000 to 2019 found 293 neurocysticercosis patients, with 59% initially presenting with epileptic seizures, 52% with headaches, and 54% with other neurological signs. Treatments varied, but outcomes were favorable in 90% of cases. In Tanzania, a cross-sectional study in three hospitals (spanning 2018–2020) involved patients with and without epileptic seizures. Using a point-of-care test for cysticercosis, the study found that over 30% of people with epileptic seizures had neurocysticercosis brain lesions, predominantly multiple and parenchymal. Serologically positive patients had more lesions, with active-stage lesions found only in this group. Among patients diagnosed with neurocysticercosis, older individuals and those with focal onset seizures and stronger headache episodes were more common.23,24

Our analysis indicated that alongside a decrease in mortality rates, there was also a notable decrease in the frequency of epileptic seizures, which corresponded with the diminished number of brain lesions. Garcia et al.25 also recorded a similar benefit of better epilepsy control. In a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, 120 patients with brain cysticerci and seizures, all on antiepileptic drugs, were randomly assigned to receive either daily albendazole (800 mg) and dexamethasone (6 mg) for 10 days (60 patients) or placebos (60 patients). Over a 30-month follow-up, the albendazole group showed a 46% reduction in seizures, particularly in seizures with generalization, and more cystic lesions resolved in this group than in the placebo group. Side effects were generally similar between the groups. This suggests that antiparasitic therapy is safe and effective, especially in reducing epileptic seizures.25

The significance of our findings lies in the fact that the treatment of neurocysticercosis with a substantial larval burden has been regarded as hazardous and potentially fatal, yet our review suggests a beneficial outcome. This story about severe adverse event following cysticidal treatment started after Wadia and colleagues reported on three patients with disseminated cysticercosis, clinically manifesting with uncontrolled epileptic seizures, progressive encephalopathy, behavioral issues, and muscular pseudohypertrophy, who succumbed after treatment with praziquantel.7 Initially, the efficacy of cysticidal drugs like praziquantel and albendazole was debated. Experts were concerned about whether the inflammation from larval death in the brain and the subsequent reduction of brain cysts were beneficial. There was also debate on whether cysticidal treatment or natural cyst degeneration was better for minimizing perilesional brain fibrosis and reducing seizure recurrence risk. Currently, experts believe that cysticidal treatment is advantageous when parasites, in the live vesicular stage, are present, although complete destruction of all cysts in the brain simultaneously is often not possible. In the initial phases of treatment, in many cases an increase in neurological symptoms due to the heightened inflammation from dying larvae is observed, primarily in the form of epileptic seizures. Besides epileptic seizures, some patients also experience headaches, often along with dizziness and vomiting.3,7

We observed that albendazole treatment is beneficial in averting fatalities, improving seizure management, and considerably reducing lesion counts. On the other hand, praziquantel use carries risks and should be avoided. Although corticosteroids by themselves fall short as a treatment, determining the optimal duration for albendazole therapy is still a challenge.8,9

Cysticercal encephalitis is a condition characterized by extensive brain inflammation caused by numerous inflamed cysticerci. Administering cysticidal drugs in these situations is generally not recommended. This is because rapidly killing the parasites may amplify the host’s inflammatory response, potentially resulting in a further increase in intracranial tension and possible transtentorial herniation. Treatment with high-dose corticosteroids, specifically dexamethasone, has been effective in many instances of cysticercal encephalitis.9,26–28

In our review, “death” was used as a primary outcome because of its clear, unbiased reportability. The variables in the study were not uniformly defined across sources. They were based on the descriptions provided by the authors of individual case reports and articles. “Clinical improvement” was noted when any clinical symptoms were reported to have improved. “Headache improvement” was considered when there was a reported decrease in either the severity or frequency of headaches. “Seizure control” referred to reports of either complete seizure cessation or a reduction in seizure frequency. “Reduction of lesion load” was interpreted as a decrease in the number of lesions observed on follow-up neuroimaging; in some instances, this meant at least a 50% reduction from the initial number of lesions.

Our review has several inherent weaknesses and limitations. Our review relied on case reports and case series, which are considered lower levels of evidence. Case reports and series are mainly descriptive and lack appropriate controls. Our results are not as robust as those from randomized controlled trials with larger sample sizes. Our study noted that 86.5% of the cases were from India. This geographic concentration might make it difficult to generalize the findings to other populations. The missing data could introduce a form of selection bias if the outcomes of the included data systematically differ from the excluded cases. There is a potential risk of publication bias. Case reports and series that find significant or unusual outcomes might be more likely to be published than those with null or expected results.

Another limitation of our study is the absence of certain crucial predictors for treatment outcomes in our multivariable logistic regression analysis. Specifically, we did not include location, number, or stage of neurocysticercosis lesions, which are known to strongly influence treatment outcomes. This omission is due to the challenges we encountered in accurately identifying these variables in our data. In many cases, neurocysticercosis lesions were difficult to categorize, with most being vesicular and some being calcified. Moreover, lesions often presented in various stages and were too numerous to count accurately. These limitations have been duly acknowledged in our study.

In conclusion, the risk of death after cysticidal treatment is not as we expected; a multicentric randomized controlled trial is needed to resolve this issue.

Supplemental Materials

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene (ASTMH) assisted with publication expenses.

Note: Supplemental materials appear at www.ajtmh.org.

REFERENCES

- 1. Bustos J, Gonzales I, Saavedra H, Handali S, Garcia HH, Cysticercosis Working Group in Peru , 2021. Neurocysticercosis. A frequent cause of seizures, epilepsy, and other neurological morbidity in most of the world. J Neurol Sci 427: 117527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Prates C, 2020. Heresenes’s short life under a “starry night”: Possible disseminated cysticercosis in an Egyptian mummy. Bioarchaeol Int 4: 231. [Google Scholar]

- 3. White AC, Jr., Coyle CM, Rajshekhar V, Singh G, Hauser WA, Mohanty A, Garcia HH, Nash TE, 2018. Diagnosis and treatment of neurocysticercosis: 2017 clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene (ASTMH). Am J Trop Med Hyg 98: 945–966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Monk EJM, Abba K, Ranganathan LN, 2021. Anthelmintics for people with neurocysticercosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 6: CD000215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. World Health Organization , 2021. WHO Guidelines on Management of Taenia solium Neurocysticercosis. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240032231. Accessed November 9, 2023. [PubMed]

- 6. Stelzle D. et al. , 2023. Efficacy and safety of antiparasitic therapy for neurocysticercosis in rural Tanzania: A prospective cohort study. Infection 51: 1127–1139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wadia N, Desai S, Bhatt M, 1988. Disseminated cysticercosis. New observations, including CT scan findings and experience with treatment by praziquantel. Brain 111: 597–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Singla A, Lekhwani S, Vaswani ND, Kaushik JS, Dabla S, 2022. Fourteen days vs 28 days of albendazole therapy for neurocysticercosis in children: An open label randomized controlled trial. Indian Pediatr 59: 916–919. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Del Brutto OH, Garcia HH, 2021. The many facets of disseminated parenchymal brain cysticercosis: A differential diagnosis with important therapeutic implications. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 15: e0009883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rizvi I, Garg RK, Malhotra HS, Kumar N, 2022. Treatment Outcome of Disseminated Cysticercosis: A Systematic Review. Available at: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42022331895. Accessed February 23, 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11. Murad MH, Sultan S, Haffar S, Bazerbachi F, 2018. Methodological quality and synthesis of case series and case reports. BMJ Evid Based Med 23: 60–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Della Gatta AN, Rizzo R, Pilu G, Simonazzi G, 2020. Coronavirus disease 2019 during pregnancy: A systematic review of reported cases. Am J Obstet Gynecol 223: 36–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kumar A, Bhagwani DK, Sharma RK, Kavita, Sharma S, Datar S, Das JR, 1996. Disseminated cysticercosis. Indian Pediatr 33:337–339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Foyaca-Sibat H, LdeF IV, Mashiyi MK, 2004. Disseminate cysticercosis. One-day treatment in a case. Electron J Biomed 3:39–43. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Prasad R, Kapoor K, Mishra D, Singh MK, Srivastava A, Mishra OP, 2012. Disseminated cysticercosis in a child. Indian J Pediatr 79: 1389–1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dhar M, Ahmad S, Srivastava S, Shirazi N, 2013. Disseminated cysticercosis: Uncommon presentation of a common disease. Ann Trop Med Public Health 6: 317–320. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kobayashi K. et al. , 2013. Rare case of disseminated cysticercosis and taeniasis in a Japanese traveler after returning from India. Am J Trop Med Hyg 89: 58–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Duvignaud A, Receveur MC, Pistone T, Malvy D, 2014. Disseminated cysticercosis revealed by subcutaneous nodules in a migrant from Cameroon. Travel Med Infect Dis 12: 551–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mouhari-Toure A, N’Timon B, Kumako V, Darre T, Saka B, Tchaou M, Amegbor K, Kombate K, Balogou AA, Pitche P, 2015. Disseminated cysticercosis: report of three cases in Togo. Bull Soc Pathol 108: 165–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Heller T, Wallrauch C, Kaminstein D, Phiri S, 2017. Case Report: Cysticercosis: Sonographic Diagnosis of a Treatable Cause of Epilepsy and Skin Nodules. Am J Trop Med Hyg 97: 1827–1829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zou Y, Wang F, Wang HB, Wu WW, Fan CK, Zhang HY, Wang L, Tian XJ, Li W, Huang MJ, 2019. Disseminated cysticercosis in China with complex and variable clinical manifestations: a case series. BMC Infect Dis 19: 543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pandey S. et al. , 2020. Quantitative assessment of lesion load and efficacy of 3 cycles of albendazole in disseminated cysticercosis: a prospective evaluation. BMC Infect Dis 20: 220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Stelzle D. et al. , 2023. Clinical characteristics and management of neurocysticercosis patients: A retrospective assessment of case reports from Europe. J Travel Med 30: taac102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Stelzle D. et al. , 2022. Epidemiological, clinical and radiological characteristics of people with neurocysticercosis in Tanzania—A cross-sectional study. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 16: e0010911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Garcia HH, Pretell EJ, Gilman RH, Martinez SM, Moulton LH, Del Brutto OH, Herrera G, Evans CA, Gonzalez AE, Cysticercosis Working Group in Peru , 2004. A trial of antiparasitic treatment to reduce the rate of seizures due to cerebral cysticercosis. N Engl J Med 350: 249–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ghosal A, Bhattacharya K, Shobhana A, Saraff R, 2020. Nightmares with a starry sky—Treating neurocysticercal encephalitis, how far to go. Trop Parasitol 10: 158–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jain RS, Handa R, Vyas A, Prakash S, Nagpal K, Bhana I, Sisodiya MS, Gupta PK, 2014. Cysticercotic encephalitis: A life threatening form of neurocysticercosis. Am J Emerg Med 32: 1444.e1–1444.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Patil TB, Gulhane RV, 2015. Cysticercal encephalitis presenting with a “starry sky” appearance on neuroimaging. J Glob Infect Dis 7: 33–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.