Abstract

Propagation of the agents responsible for transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSEs) in cultured cells has been achieved for only a few cell lines. To establish efficient and versatile models for transmission, we developed neuroblastoma cell lines overexpressing type A mouse prion protein, MoPrPC-A, and then tested the susceptibility of the cells to several different mouse-adapted scrapie strains. The transfected cell clones expressed up to sixfold-higher levels of PrPC than the untransfected cells. Even after 30 passages, we were able to detect an abnormal proteinase K-resistant form of prion protein, PrPSc, in the agent-inoculated PrP-overexpressing cells, while no PrPSc was detectable in the untransfected cells after 3 passages. Production of PrPSc in these cells was also higher and more stable than that seen in scrapie-infected neuroblastoma cells (ScN2a). The transfected cells were susceptible to PrPSc-A strains Chandler, 139A, and 22L but not to PrPSc-B strains 87V and 22A. We further demonstrate the successful transmission of PrPSc from infected cells to other uninfected cells. Our results corroborate the hypothesis that the successful transmission of agents ex vivo depends on both expression levels of host PrPC and the sequence of PrPSc. This new ex vivo transmission model will facilitate research into the mechanism of host-agent interactions, such as the species barrier and strain diversity, and provides a basis for the development of highly susceptible cell lines that could be used in diagnostic and therapeutic approaches to the TSEs.

The transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSEs), or prion diseases, are fatal neurodegenerative disorders that include Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease and Gerstmann-Sträussler syndrome in humans and scrapie and bovine spongiform encephalopathy in animals (29). Human TSEs are unique in that they occur in infectious, sporadic, and genetic forms. Although the nature of the infective agent, termed the prion (28), is not fully understood, the conversion of the normal cellular prion protein, PrPC, to an abnormal protease-resistant isoform, PrPSc, is a key event in the pathogenesis of all TSEs (27). The role of PrP in TSEs is also exemplified by genetic linkages between mutations in the PrP gene in the human inherited TSEs (25), as well as by the appearance of a spongiform encephalopathy in transgenic animals overexpressing mutated PrP (13, 18).

While the physiological function of host-encoded PrPC remains unknown, the central role of interaction between PrPC and PrPSc in the TSEs is evidenced by the fact that homozygous disruption of the Prnp gene encoding PrP renders mice resistant to prion, and the animals are no longer capable of generating PrPSc (4, 22, 33). It has also been shown by several in vivo and ex vivo experiments that PrPC is necessary for the neurotoxic effect of PrPSc (1, 2). In addition, data obtained from in vivo transmission studies with transgenic mice harboring various copy numbers of the Prnp gene suggest that the expression level of PrPC is a major factor in restricting agent replication and the incubation time of the diseases (6, 39).

Several neuronal cell lines persistently infected with mouse-adapted scrapie have been available for investigation of the biochemical properties of PrPSc (5, 30, 31, 34). A mouse neuroblastoma cell line infected with a Chandler scrapie strain, ScN2a, has been used to obtain important results concerning the mechanism of PrPSc generation and trafficking (9, 10, 37) and to evaluate potential therapeutic agents (8). However, the currently available cell lines are not sensitive enough to detect infectivity in tissue specimens (12), probably due to the relatively low level of PrPC expression in the host cells. An effective ex vivo system is urgently needed because animal assays are costly and time-consuming and because of the growing numbers of patients with new variant (15) and iatrogenic Creutzfeldt-Jakob (20) disease. We report here that PrP overexpression renders cell lines readily infectible by three mouse scrapie strains: Chandler, 139A, and 22L. These cell culture models represent a new tool in prion research and provide a basis for investigation into the mechanisms of TSE transmission and strain diversity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents and antibodies.

Pefabloc and proteinase K were purchased from Boehringer Mannheim. Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM), Opti-MEM, trypsin, G418, and horse serum were from Life Technologies, Inc., and fetal calf serum (FCS) was from BioWhittaker. Secondary antibodies were from Jackson ImmunoResearch (West Grove, Pa.). All other reagents were from Sigma. Rabbit polyclonal antibody P45-66, raised against synthetic peptide-encompassing mouse PrP (MoPrP) residues 45 to 66, has been described previously (21). Monoclonal antibodies SAF 60, SAF 69, and SAF 70 were generated in mice with scrapie-associated fibrils from infected hamster brains as immunogens by conventional procedures (16). These antibodies recognize residues 142 to 160 of hamster PrP, as demonstrated by enzyme immunoassay measurements with synthetic peptides (M. Rodolfo et al., unpublished data).

Cell cultures.

The mouse neuroblastoma cell line N2a, purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC CCL131), was transfected with a plasmid carrying wild-type mouse prnp cDNA, as previously described (21, 35). Four different clones (01, 11, 22, and 58) overexpressing MoPrP, isolated after selection with 700 μg of G418 per ml, were used in the experiments. Transfected and nontransfected N2a cells were cultured in Opti-MEM containing 10% heat-inactivated FCS, 2 mM l-glutamine, and penicillin-streptomycin and split every 4 days at a 1:10 dilution. GT1-7 cells, a subcloned cell line of immortalized hypothalamic GT-1 cells (23), a kind gift from D. Holtzman (Washington University, St. Louis, Mo.), were maintained in DMEM containing both heat-inactivated FCS and heat-inactivated horse serum at 5% each and penicillin-streptomycin. The cells were split every 5 days at a 1:3 ratio. All cultured cells were maintained at 37°C in 5% CO2 in the biohazard P3 laboratory of our institute.

Preparation of brain homogenates.

Brains infected with Chandler strain were obtained from terminal stage CD-1 mice that had been inoculated with cell lysates of ScN2a (30), which were kindly donated by B. Caughey (Rocky Mountain Laboratories, Hamilton, Mont.). The pooled brains were homogenized to 10% (wt/vol) in cold phosphate-buffered saline containing 5% glucose. Other brain homogenates (10% [wt/vol]) with mouse-adapted scrapie strains 22A, 22L, 139A, and 87V were kindly provided by R. Carp (New York State Institute for Basic Research). The origin and history of the strains are presented in Table 1. All homogenates were kept at −80°C until use.

TABLE 1.

Summary of inocula

| Strain | Host mice

|

Protein concn (mg/ml)a | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strain | Prnp allotype | ||

| Chandler | CD-1 | a/a | 6.2 |

| 139A | C57BL | a/a | 7.4 |

| 22L | C57BL | a/a | 6.5 |

| 22A | IM | b/b | 7.7 |

| 87V | IM | b/b | 7.8 |

Concentration of total protein in 10% (wt/vol) brain homogenate, measured by BCA protein assay.

Ex vivo transmission.

Cells were grown in 6-well plates at 2 × 105 cells/well 2 days before inoculation. They were then incubated for 5 h with 1 ml of 0.2 or 2% brain homogenate diluted in Opti-MEM. The theoretical multiplicities of infection were 1 and 10 50% infectious dose per cell. One milliliter of regular culture medium was added and the cells were incubated for an additional 17 h. The medium was then removed and the cells were cultured as usual. To evaluate the presence of infectious material in the cultures, a cell-to-cell transmission experiment was performed. The cells were collected from a confluent 175-cm2 flask under sterile conditions and resuspended in 100 μl of cold phosphate-buffered saline with 5% glucose. This suspension was subjected to four cycles of freezing-thawing and then passed through a 27-gauge needle. Twenty microliters of this extract diluted in 1 ml of Opti-MEM was added to the GT1-7 cells, which were then incubated for 2 days.

Detection of PrPC in cultured cells.

Confluent cultures were lysed for 30 min at 4°C in Triton-DOC lysis buffer (1× buffer is 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% Triton X-100, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, and 50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5]) plus protease inhibitors (1 μg [each] of pepstatin and leupeptin per ml and 2 mM EDTA). After 1 min of centrifugation at 10,000 × g, the supernatant was collected and its total protein concentration was measured by the BCA protein assay (Pierce). The equivalent of 12.5 μg of total protein in sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) loading buffer was subjected to SDS–12% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. The proteins were transferred onto an Immobilon-P membrane (Millipore) in 3-(cyclohexylamino)-1-propanesulfonic acid (CAPS) buffer containing 10% methanol at 400 mA for 60 min. The membrane was blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk in TBST (0.1% Tween 20, 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.8]) for 1 h at room temperature, and MoPrP was detected by immunoblotting with P45-66 antibody as previously described (21). The blots were developed by enhanced chemiluminescence and exposed on X-ray film (Biomax MR; Kodak). Films were analyzed with image analysis software (Sigma Scan/Image, version 1.02.09; Jandel Scientific).

Detection of PrPSc.

To detect the presence of PrPSc in cultures, cells of a 25-cm2 flask were lysed in 1 ml of Triton-DOC lysis buffer on ice for 15 min. The supernatant was collected and its total protein concentration was adjusted with lysis buffer to 1 mg/ml. The samples were digested with 20 μg of proteinase K per ml at 37°C for 30 min, and the digestion was stopped by incubating with Pefabloc (1 mM) for 5 min on ice. The samples were centrifuged at 19,283 × g for 45 min at 4°C, and the pellet was resuspended in 30 μl of Laemmli buffer (19) and then loaded onto a 12% polyacrylamide gel just after boiling. Proteins were electroblotted onto the membranes, and PrP was detected with a mixture of three monoclonal antibodies, SAF 60, SAF 69, and SAF 70 (present in a mixture of ascitic fluids diluted 1/200 in TBST). To detect PrPSc in infected brains, proteins were extracted from 10% brain homogenate mixed with an equal volume of 2× Triton-DOC lysis buffer. The protein concentration was then adjusted to 3 mg/ml and the lysate was digested with 100 μg of proteinase K per ml at 37°C for 30 min. The samples were then mixed with an equal volume of 2× Laemmli buffer, boiled for 5 min, and analyzed by Western blotting.

RESULTS

Expression of PrPC in host cells.

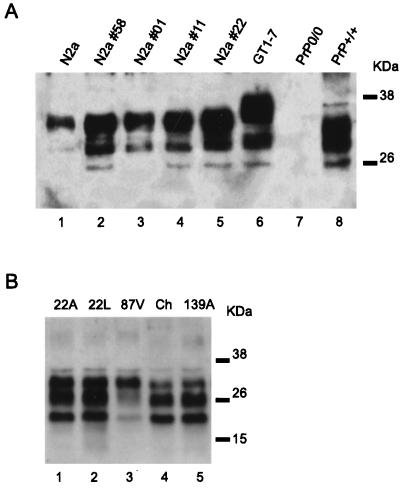

The level of PrPC expression in untransfected N2a and GT1-7 cells, as well as in four transfected N2a clones, was analyzed by immunoblotting with the MoPrP amino-terminus-specific antibody P45-66. Transfected cells gave a stronger signal than the untransfected cells (Fig. 1A, lanes 1 to 4). Quantification of the signal, achieved through serial dilution of the extracts and Western blotting (results not shown), revealed that N2a subclones 58, 01, 11, and 22 had five, three, four, and six times the PrP level of untransfected N2a cells, respectively. In addition, PrP expression in the GT1-7 cells (lane 5) was estimated to be eight times that in the N2a cells. PrPC in the GT1-7 cells had lower mobility, most likely due to its greater degree of glycosylation. The transfected N2a cells had a slightly lower growth rate than the untransfected cells and showed a tendency to aggregate (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Detection of PrPC in the different cell lines and of PrPSc in the brain extracts. (A) Lysate from various cell lines was analyzed by Western blotting with the PrP N-terminus-specific antibody P45-66. A total of 12.5 μg of protein was loaded onto each lane. N2a cells (lane 1) were stably transfected with mouse PrP and four subclones (N2a subclones 58, 01, 11, and 22) were selected (lanes 2 to 5). These clones expressed between three and six times more PrP than the untransfected N2a cells. GT1-7 cells gave the highest PrP signal (lane 6) and had glycosylated PrP bands of higher molecular weights. As controls, protein extracts prepared from the brains of PrP knockout (PrP0/0) and wild-type (PrP+/+) mice were used (lanes 7 and 8, respectively). (B) Protein extracts (3 mg/ml) from the brains of mice inoculated with various prion strains (i.e., 22A, 22L, 87V, Chandler, and 139A) were digested with proteinase K (100 μg/ml) and analyzed by Western blotting with a mixture of monoclonal antibodies (SAF 60, SAF 69, and SAF 70). PrPSc was detected in all samples (15 μg/lane) but differences existed among the glycosylation patterns of the bands. The positions of molecular size marker proteins are designated in kilodaltons. Ch, Chandler.

PrPSc in inoculum.

Prior to the ex vivo transmission studies, the presence of PrPSc was confirmed in all brain homogenates (Fig. 1B). After proteinase K digestion, different glycosylation patterns were observed in the PrPSc bands. The PrPSc pattern of the Chandler isolate was identical to that of 139A, as expected, while those of 22L, 22A, and 87V were clearly distinguishable from the first two strains, in concordance with previous reports (36). Notably, despite their different sequences, the patterns produced by 22A and 22L were indistinguishable. To evaluate the sensitivity of our immunoblotting for the detection of PrPSc, serially diluted samples of the Chandler homogenate were tested. PrPSc was still detectable in a sample containing 0.12 μg of total protein, equivalent to 2 μg of brain tissue (data not shown).

Production of PrPSc in N2a cells after inoculation with the Chandler strain.

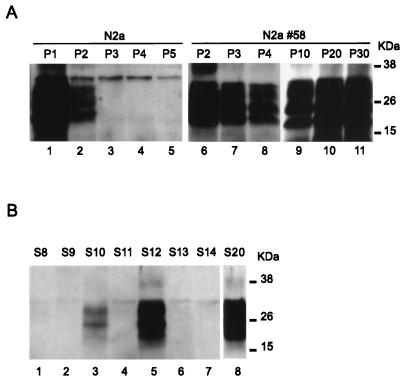

The MoPrP-transfected N2a clone 58 and untransfected N2a cells were incubated with 2% Chandler brain homogenate. At each passage, confluent cells were lysed and PrPSc was detected by immunoblotting after proteinase K digestion (Fig. 2A). After one passage (5 days postinoculation), a strong PrPSc signal was present in the untransfected cells (Fig. 2A, lane 1). In fact, the presence of PrPSc in the first two passages was detected in all experiments, whether or not infection was achieved, and was assumed to represent material remaining from the inoculum. At the second and third passages, the signal in the untransfected cells decreased, and it disappeared completely by the fourth passage (lanes 2 to 5). This experiment was repeated eight times (Table 2) and PrPSc was never detected after five passages in any experiment. In two experiments, the N2a cells were further cultured and tested again for PrPSc after 10 passages but remained negative (data not shown). In contrast, in the infected N2a 58 cells, the signal for PrPSc remained strong and was still detectable even after 30 passages (Fig. 2, lanes 6 to 11). This result was confirmed in several independent experiments (Table 2), and while at least four lines were passaged more than 10 times, a subsequent loss of the signal was never observed. To estimate the frequency of infection in N2a 58 cells, we subcloned the infected population by a limiting dilution method, as previously described (30). Briefly, after one passage, cells were vigorously diluted and seeded in a 96-well plate at 0.75 cells/well. Of 23 isolated subclones, 3 were positive for PrPSc (Fig. 2B). Notably, the level of PrPSc production in our cells was four- to sixfold higher than that in subclones derived from previously established ScN2a cells (data not shown). One clone, designated S20, grew slowly and revealed a more differentiated morphology. This phenomenon seemed unlikely to be due to the prion infection because the characteristics did not change after an antiprion drug treatment (data not shown) and because such changes were not seen in the other clones.

FIG. 2.

Infection of untransfected and transfected N2a cell lines with the Chandler strain. (A) N2a cells and one clone of transfected N2a cells (N2a 58) were infected with Chandler homogenate. Following the infection, the cells were passaged every 4 days and the presence of PrPSc was analyzed by Western blotting after proteinase K digestion. After one or two passages (P1 and P2) a strong signal was detected in the N2a cells (lanes 1 and 2), but this signal soon diminished and then disappeared (lanes 3 to 5). In transfected N2a cells (N2a 58), PrPSc persisted even after 30 passages (P30), indicating successful infection (lanes 6 to 11). (B) Infected N2a 58 cells were subcloned and 23 clones were analyzed for PrPSc. Persistent infection was observed in only three of these (S10, S12, and S20) (lanes 3, 5, and 8), while no signal was seen in any of the others (lanes 1, 2, 4, 6, and 7).

TABLE 2.

Frequency of successful transmission in cultured cells

| Host cell | No. of transmissions/no. of passages in inoculum

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chandler | 139A | 22L | 22A | 87V | |

| N2a | 0/8 | NTa | NT | NT | NT |

| N2a 58 | 10/10 | 4/4 | 4/4 | 0/4 | 0/4 |

| GT1-7 | 4/4 | 1/1 | 3/3 | 0/3b | 0/3b |

NT, not tested.

PrPSc was not detectable in the fifth and 10th passages of cell lysate.

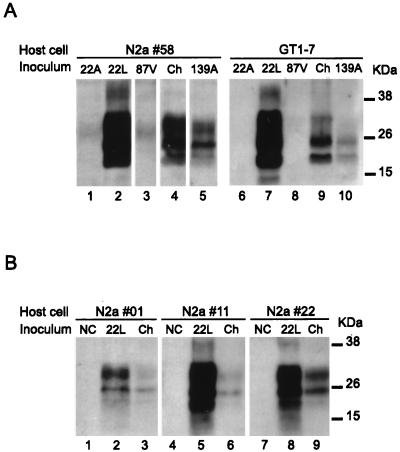

Transmission of different TSE strains to transfected N2a and GT1-7 cells.

To evaluate whether or not the N2a 58 cells are sensitive to other mouse-adapted scrapie strains, we inoculated different homogenates, at a 2% concentration, into the N2a 58 and GT1-7 cells. Only 22L, 139A, and Chandler strains were transmissible to both cell types (Fig. 3A), and PrPSc production was detectable in up to 20 passages in all positive cultures. Strains 22A and 87V (lanes 1 and 3) showed a weak signal of about 25 kDa at the fifth passage, but this disappeared after the next passage. To determine the susceptibility of transfected cells to TSE agents, we carried out infection experiments on other PrP-overexpressing cell clones. Cells were incubated with a 0.2% Chandler or 22L homogenate and then tested for PrPSc production after five passages. PrPSc was detectable by Western blotting in all inoculated cell types, even the lowest-expressing N2a 01 cells (Fig. 3B). Interestingly, cells inoculated with 22L always produced a much stronger signal than those inoculated with Chandler homogenate.

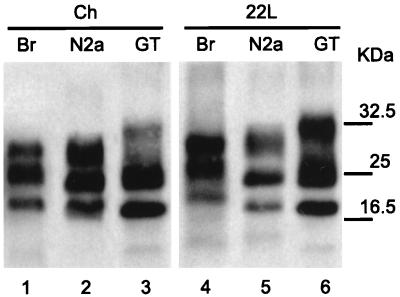

FIG. 3.

Infection of transfected N2a and GT1-7 cell lines with different prion strains. (A) GT1-7 and N2a 58 cells were infected with a 0.2% brain homogenate of 22A, 22L, 87V, Chandler, and 139A strains. After five passages (lane 5), the presence of PrPSc was analyzed by Western blotting after proteinase K digestion. Only 22L, Chandler, and 139A homogenates led to the production of PrPSc by the infected cell lines. (B) Three MoPrP-transfected N2a subclones (01, 11, and 22) were incubated with a 0.2% homogenate of 22L and Chandler strains. PrPSc was detected in each line after five passages and appeared to correlate with the level of PrPC expression of the different clones. NC, negative control; Ch, Chandler.

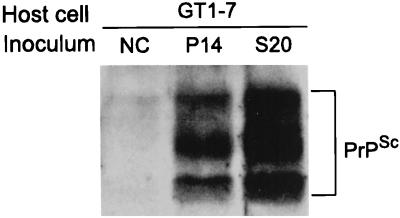

Cell-to-cell transmission of PrPSc.

Ultimately, only animal inoculation experiments can provide confirmation that the infected cell lines generated in this work not only synthesize PrPSc molecules but also permit growth of the agent, and we have recently confirmed that inoculation of mice with PrPSc-positive cells does indeed cause mouse scrapie (data not shown). We have also conducted transmission experiments with GT1-7 cells as recipients, as previously reported (34). For this, cell lysates from infected N2a 58 and S20 cells were prepared and added to the GT1-7 cells. PrPSc production was subsequently detected in cells inoculated with either of the infected cell lysates (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Transmission from infected N2a 58 cells to noninfected GT1-7 cells. GT1-7 cells were inoculated with lysates prepared from noninfected N2a 58 cells (NC), cells infected with the Chandler strain which were passaged 14 times without subcloning (P14), or subclonal cells from infected N2a 58 cells (S20). PrPSc was detected after five passages in GT1-7 cells inoculated with either of the infected N2a 58 cell lysates.

PrPSc pattern.

After proteinase K digestion, the different brain homogenates showed distinct PrPSc glycosylation patterns (Fig. 1). Chandler and 22L homogenates were distinguishable as the diglycosyl band for Chandler and the aglycosyl band for 22L were slightly underrepresented (Fig. 1B, lanes 2 and 4; Fig. 5, lanes 1 and 4). Additionally, the mobility of the aglycosylated PrPSc was lower in 22L. Upon passage into cells, the PrPSc had a higher mobility in both cell lines. Interestingly, this mobility was the same for both strains in the same cell line, with that in GT1-7 cells being even higher than that in N2a cells. Distribution in the infected N2a cells was variable, however, showing either no clear difference (Fig. 3B, lane 5; Fig. 5, lane 2) or an underrepresentation of the aglycosyl band (Fig. 3B, lanes 2, 8, and 9). In the GT1-7 cells, on the other hand, the diglycosyl band was consistently underrepresented after infection with the 22L strain (Fig. 3A, lane 7; Fig. 5, lane 6).

FIG. 5.

Proteinase K-digested samples obtained from Chandler and 22L brain homogenates (lanes 1 and 4) and from N2a 58 and GT1-7 cells infected with these two extracts (lanes 2, 3, 5, and 6) were loaded onto SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gels for comparison of their respective electrophoretic patterns.

DISCUSSION

In vivo transmission studies with transgenic mice have clearly demonstrated an inverse correlation between the expression level of PrPC in host animals and the incubation time of experimental prion diseases. A prolonged incubation time was noted in Prnp0/+ mice (4, 22, 33), and host animals harboring a high copy number of the Prnp transgene have shown a much shorter incubation time than animals harboring the wild type (6, 39). To test the hypothesis that high-level PrPC expression improves the sensitivity of cells to TSE agents, we developed stable transfected cell lines expressing various levels of MoPrP and subjected the cells to ex vivo transmission of mouse-adapted TSEs. N2a cells have been reported to be susceptible to Chandler scrapie prion, and infected N2a cells (ScN2a) have been used to analyze the cell biology of prions (12, 26). For this reason, we first subjected both untransfected and transfected N2a cells to the Chandler isolate but failed to detect any PrPSc in the untransfected cells after the third passage or thereafter. This result emphasizes the poor efficiency of transmission and the need to subclone cell populations to maintain prion infection in N2a cells. On the other hand, infection of different N2a cell lines overexpressing a wild-type MoPrP was repeatedly successful. The inoculated cells persistently produced PrPSc after 30 passages, even without subcloning, and the relative level of PrPSc production seemed to correlate with the level of PrP overexpression in the cells. In addition, the success rate of transmission was 100% and the frequency of infection was estimated at around 13% in the transfected cells, while that of untransfected N2a was previously reported to be less than 1% (30). Although the possibility of low-level infection or the presence of undetectable levels of PrPSc in the untransfected N2a cells cannot be ruled out at this point, our data strongly support the hypothesis that overexpression of PrPC can increase the sensitivity of cells to the agent. In a preliminary experiment, we were able to infect the transfected N2a cells with a high dilution of the Chandler homogenate (0.0002%). A full-scale study is now in progress to evaluate, for different samples, the respective sensitivities of animal assay, Western blotting, and our ex vivo transmission system.

In the present study, we also successfully infected GT1-7 cells with mouse prion. This cell line is a subline of immortalized hypothalamic neuronal cells, designated GT1, isolated from simian virus 40 T-antigen-introduced mice, and it has been reported to be susceptible to prion (34). The GT1-7 cells expressed even higher levels of PrPC than the transfected N2a cells. As expected, they were sensitive to the agent, again supporting the theory that the level of PrPC is an important factor for the successful propagation of prion. The fact that we have not been able to transmit mouse TSEs to either nonneuronal or nonmurine cells expressing large amounts of MoPrPC suggests that certain tissue- or species-specific factors other than PrPC are likely to be involved in the mechanism of propagation and replication of prion, as suggested by others (24, 38).

The presence of numerous strains of prion constitutes perhaps the most challenging evidence to the prion hypothesis, but the existence of distinct PrPSc conformations in different hamster strains was recently proposed as a possible mechanism for this strain variation (11, 32). In the present study, we tested the susceptibility of the transfected N2a and GT1-7 cells to five different well-established mouse scrapie strains. Both cell types were susceptible to 22L, 139A, and Chandler strains, but not to 22A or 87V. The 22L, 139A, and Chandler strains were obtained from PrP-A mice (7), as were the cell lines, whereas 22A and 87V were obtained from PrP-B mice (3) (Table 1). A possible explanation for the unsuccessful transmission of 22A and 87V may thus reside in the differences in the PrP allotype between the host and inoculum. This explanation is consistent with previous reports demonstrating the influence of PrPC polymorphism upon the incubation time of disease in both congenic and transgenic mice (6, 24). It is also possible that each strain possesses its own cell tropism, illustrated, for example, by differences in the localization of the neuropathologic changes in the affected brains (14, 17). The use of other strains such as ME7 or Fukuoka-1 and of strains passaged in mice of various genetic backgrounds may help in the understanding of this phenomenon. Another approach will be to use cell lines transfected with the Prnp-b allele as recipients.

The PrPSc profiles of 22L and Chandler strains can be distinguished in brain homogenates mostly by differences in the size of the unglycosylated fragment (Fig. 1 and 5). In infected N2a and GT1-7 cell lines, this difference was less clear and the fragments had a higher mobility than in the homogenate. Glycosylation patterns were also affected, and in GT1-7 cells, at least, Chandler and 22L strains were clearly distinguishable but still different from the inoculum. These data support the idea that the glycosylation of PrPSc depends not only upon the strain but also on the host cell type (36). The possibility that the strain and/or the conformation of PrPSc is affected upon passage into cells remains to be established, and it will be particularly interesting to see if strain properties can be recovered upon inoculation of infected cell lysates into mice. A more complete characterization of PrPSc in the different infected cell lines that we have generated in this work is also needed. It will be especially important to compare the biochemical properties of PrPSc (level of protease resistance, insolubility, and phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase sensitivity) between strains, as well as the biological characteristics such as subcellular localization. Notably, the 22L strain passaged in the different cell lines always gave a stronger PrPSc signal than the other strains. At this stage, we do not know if this is linked to biological properties of the strain, to biochemical properties of the PrPSc molecules such as tertiary structure, or to the infectious titers of the brain homogenates used. However, the latter is unlikely, since diluted 22L still led to a stronger PrPSc signal than did the other strains (data not shown).

In conclusion, the infected cell cultures that we generated in this work are likely to prove valuable in the search for the molecular mechanisms behind strain variation. They also represent new models for the study of PrPSc generation and the evaluation of potential therapeutic agents. Moreover, the results presented here suggest the potential for the adaptation of our murine cell culture system to create a human cell model for the laboratory testing of infectivity in clinical specimens. Such a diagnostic system could also conceivably constitute a means of evaluating the possibility of transmission from bovine spongiform encephalopathy-affected food to humans.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the Fondation de la Recherche Médicale, the Cellule de Coordination Interorganismes sur les Prions, and the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique. H.L. and S.L. are supported by a grant from the European Community (Biotech BIO4CT98-6064). N.N. is the recipient of a grant from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

We are grateful to Richard Carp (Staten Island, N.Y.) for providing infected brain homogenates and to David Holtzman (Washington University, St. Louis, Mo.) for GT1-7 cells. We thank Amanda Nishida for critically reading the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brandner S, Isenmann S, Raeber A, Fischer M, Sailer A, Kobayashi Y, Marino S, Weissmann C, Aguzzi A. Normal host prion protein necessary for scrapie-induced neurotoxicity. Nature. 1996;379:339–343. doi: 10.1038/379339a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown D R, Herms J, Kretzschmar H A. Mouse cortical cells lacking cellular PrP survive in culture with a neurotoxic PrP fragment. Neuroreport. 1994;5:2057–2060. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199410270-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bruce M E, Fraser H. Scrapie strain variation and its implications. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1991;172:125–138. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-76540-7_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bueler H, Aguzzi A, Sailer A, Greiner R A, Autenried P, Aguet M, Weissmann C. Mice devoid of PrP are resistant to scrapie. Cell. 1993;73:1339–1347. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90360-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Butler D A, Scott M R, Bockman J M, Borchelt D R, Taraboulos A, Hsiao K K, Kingsbury D T, Prusiner S B. Scrapie-infected murine neuroblastoma cells produce protease-resistant prion proteins. J Virol. 1988;62:1558–1564. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.5.1558-1564.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carlson G A, Ebeling C, Yang S L, Telling G, Torchia M, Groth D, Westaway D, DeArmond S J, Prusiner S B. Prion isolate specified allotypic interactions between the cellular and scrapie prion proteins in congenic and transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:5690–5694. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.12.5690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carp R I, Meeker H, Sersen E, Kozlowski P. Analysis of the incubation periods, induction of obesity and histopathological changes in senescence-prone and senescence-resistant mice infected with various scrapie strains. J Gen Virol. 1998;79:2863–2869. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-79-11-2863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caughey B, Brown K, Raymond G J, Katzenstein G E, Thresher W. Binding of the protease-sensitive form of PrP (prion protein) to sulfated glycosaminoglycan and Congo red. J Virol. 1994;68:2135–2141. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.4.2135-2141.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caughey B, Race R E, Ernst D, Buchmeier M J, Chesebro B. Prion protein biosynthesis in scrapie-infected and uninfected neuroblastoma cells. J Virol. 1989;63:175–181. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.1.175-181.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Caughey B, Raymond G J. The scrapie-associated form of PrP is made from a cell surface precursor that is both protease- and phospholipase-sensitive. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:18217–18223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Caughey B, Raymond G J, Bessen R A. Strain-dependent differences in beta-sheet conformations of abnormal prion protein. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:32230–32235. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.48.32230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chesebro B, Wehrly K, Caughey B, Nishio J, Ernst D, Race R. Foreign PrP expression and scrapie infection in tissue culture cell lines. Dev Biol Stand. 1993;80:131–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chiesa R, Piccardo P, Ghetti B, Harris D A. Neurological illness in transgenic mice expressing a prion protein with an insertional mutation. Neuron. 1998;21:1339–1351. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80653-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DeArmond S J, Sanchez H, Yehiely F, Qiu Y, Ninchak-Casey A, Daggett V, Camerino A P, Cayetano J, Rogers M, Groth D, Torchia M, Tremblay P, Scott M R, Cohen F E, Prusiner S B. Selective neuronal targeting in prion disease. Neuron. 1997;19:1337–1348. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80424-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ghani A C, Ferguson N M, Donnelly C A, Hagenaars T J, Anderson R M. Epidemiological determinants of the pattern and magnitude of the vCJD epidemic in Great Britain. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1998;265:2443–2452. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1998.0596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grassi J, Frobert Y, Lamourette P, Lagoutte B. Screening of monoclonal antibodies using antigens labeled with acetylcholinesterase: application to the peripheral proteins of photosystem 1. Anal Biochem. 1988;168:436–450. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(88)90341-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hecker R, Taraboulos A, Scott M, Pan K M, Yang S L, Torchia M, Jendroska K, DeArmond S J, Prusiner S B. Replication of distinct scrapie prion isolates is region specific in brains of transgenic mice and hamsters. Genes Dev. 1992;6:1213–1228. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.7.1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hsiao K K, Groth D, Scott M, Yang S L, Serban H, Rapp D, Foster D, Torchia M, Dearmond S J, Prusiner S B. Serial transmission in rodents of neurodegeneration from transgenic mice expressing mutant prion protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:9126–9130. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.19.9126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lang C J, Heckmann J G, Neundorfer B. Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease via dural and corneal transplants. J Neurol Sci. 1998;160:128–139. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(98)00226-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lehmann S, Harris D A. A mutant prion protein displays an aberrant membrane association when expressed in cultured cells. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:24589–24597. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.41.24589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Manson J C, Clarke A R, McBride P A, McConnell I, Hope J. PrP gene dosage determines the timing but not the final intensity or distribution of lesions in scrapie pathology. Neurodegeneration. 1994;3:331–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mellon P L, Windle J J, Goldsmith P C, Padula C A, Roberts J L, Weiner R I. Immortalization of hypothalamic GnRH neurons by genetically targeted tumorigenesis. Neuron. 1990;5:1–10. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90028-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moore R C, Hope J, McBride P A, McConnell I, Selfridge J, Melton D W, Manson J C. Mice with gene targetted prion protein alterations show that Prnp, Sinc and Prni are congruent. Nat Genet. 1998;18:118–125. doi: 10.1038/ng0298-118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parchi P, Gambetti P. Human prion diseases. Curr Opin Neurol. 1995;8:286–293. doi: 10.1097/00019052-199508000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Priola S A, Caughey B, Raymond G J, Chesebro B. Prion protein and the scrapie agent: in vitro studies in infected neuroblastoma cells. Infect Agents Dis. 1994;3:54–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Prusiner S B. Molecular biology of prion diseases. Science. 1991;252:1515–1522. doi: 10.1126/science.1675487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Prusiner S B. Novel proteinaceous infectious particles cause scrapie. Science. 1982;216:136–144. doi: 10.1126/science.6801762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Prusiner S B, Scott M R, Dearmond S J, Cohen F E. Prion protein biology. Cell. 1998;93:337–348. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81163-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Race R E, Fadness L H, Chesebro B. Characterization of scrapie infection in mouse neuroblastoma cells. J Gen Virol. 1987;68:1391–1399. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-68-5-1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rubenstein R, Deng H, Race R E, Ju W, Scalici C L, Papini M C, Kascsak R J, Carp R I. Demonstration of scrapie strain diversity in infected PC12 cells. J Gen Virol. 1992;73:3027–3031. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-73-11-3027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Safar J, Wille H, Itri V, Groth D, Serban H, Torchia M, Cohen F E, Prusiner S B. Eight prion strains have PrP(Sc) molecules with different conformations. Nat Med. 1998;4:1157–1165. doi: 10.1038/2654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sakaguchi S, Katamine S, Shigematsu K, Nakatani A, Moriuchi R, Nishida N, Kurokawa K, Nakaoke R, Sato H, Jishage K, Kuno J, Noda T, Miyamoto T. Accumulation of proteinase K-resistant prion protein (PrP) is restricted by the expression level of normal PrP in mice inoculated with a mouse-adapted strain of the Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease agent. J Virol. 1995;69:7586–7592. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.12.7586-7592.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schatzl H M, Laszlo L, Holtzman D M, Tatzelt J, DeArmond S J, Weiner R I, Mobley W C, Prusiner S B. A hypothalamic neuronal cell line persistently infected with scrapie prions exhibits apoptosis. J Virol. 1997;71:8821–8831. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.11.8821-8831.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shyng S L, Lehmann S, Moulder K L, Harris D A. Sulfated glycans stimulate endocytosis of the cellular isoform of the prion protein, PrPC, in cultured cells. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:30221–30229. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.50.30221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Somerville R A, Chong A, Mulqueen O U, Birkett C R, Wood S C, Hope J. Biochemical typing of scrapie strains. Nature. 1997;386:564. doi: 10.1038/386564a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Taraboulos A, Raeber A J, Borchelt D R, Serban D, Prusiner S B. Synthesis and trafficking of prion proteins in cultured cells. Mol Biol Cell. 1992;3:851–863. doi: 10.1091/mbc.3.8.851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Telling G C, Scott M, Mastriani J, Gabizon R, Torchia M, Cohen F E, DeArmond S J, Prusiner S B. Prion propagation in mice expressing human and chimeric PrP transgenes implicates the interaction of cellular PrP with another protein. Cell. 1995;83:79–90. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90236-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tremblay P, Meiner Z, Galou M, Heinrich C, Petromilli C, Lisse T, Cayetano J, Torchia M, Mobley W, Bujard H, DeArmond S J, Prusiner S B. Doxycycline control of prion protein transgene expression modulates prion disease in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:12580–12585. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.21.12580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]