The World Bank’s policies may sound reassuring in Washington, but their true efficacy can be gauged only at country level. Each region (figure) offers differing challenges—from economic collapse in the Far East to economic infancy in central Asia; from perpetual poverty in Africa to the floundering aspirations of Latin America. Perhaps, of all regions, South Asia is the most enigmatic. Sri Lanka’s healthcare system is relatively successful despite the ongoing civil war, whereas Nepal and Afghanistan lie at the other end of the spectrum. Somewhere in between—geographically, and in terms of health indicators—are Bangladesh, India, and Pakistan.

A sixth of the world’s population is crammed into what was, until partition in 1947, a single nation. Bangladesh, India, and Pakistan may have common cultures, but in their short, independent lives they have acquired distinct personalities which require differing approaches from the bank (table). In Bangladesh, approximately 35% of health sector funding of the government is coordinated through a large consortium of donors and aid agencies, headed by the bank. In India, specific disease control, health, population and family planning, and nutrition programmes are being increasingly linked through state-wide health reform programmes. In Pakistan, by contrast, lending for health is dependent on the government introducing institutional reforms. The regions within each of these countries can present equally diverse challenges.

Richard Skolnik, the bank’s sector leader for health, nutrition, and population in South Asia, believes that the region is unique: “This region is especially important given the very large numbers of very poor people. Our aim over the long term would be to assist our client countries in establishing coherent, effective, and sustainable approaches to health.” Such approaches seem far off in an area that is struggling against malnutrition, especially in children, high fertility, high maternal mortality, and gender inequality; as Richard Skolnik puts it, “The region hasn’t historically paid high levels of attention to the quality of health outcomes.”

Summary points

The success of the World Bank’s policies can only be truly judged in client countries

South Asia offers a useful insight into the bank’s response to differing challenges in Bangladesh, India, and Pakistan

High levels of poverty, poor health indicators, gender inequality, rampant private healthcare, and corruption are some of the defining features of the region.

Decentralisation has helped the bank’s negotiations with the Bangladeshi government in developing a mutually acceptable health programme

Critics argue that the healthcare agenda in Bangladesh is still strongly driven by the bank and are concerned about the sustainability of projects

He argues that South Asian nations have been prone to using ineffective, inefficient, and outmoded models of service delivery that have gauged success by the numbers treated rather than the outcomes of those treatments—a criticism that many others level at the bank as well. As an example Skolnik describes the pride many health workers in India took over the large number of cataract operations in their national programme, even though closer evaluation revealed that 25% of those operations may not have been appropriate.

Rampant private health and corruption

Another vital issue is the pre-eminence of the private sector in the region. National surveys in Pakistan show that only 20% of the population is using the government’s health facilities; the rest see quacks, dispensers, traditional healers, and, if they can afford to, doctors in the private sector. Patients regularly complain that if they consult a doctor at an overcrowded government clinic they’ll be offered a longer consultation privately by the same doctor. Because of the waiting times and perceived quality of service, patients readily decide on a private appointment.

One prominent bank employee says that the bank doesn’t promote private health care but, because many of the poor use the private sector, the bank is inevitably drawn into enhancing it. In addition, the bank argues that government services are so inadequate in this region that the private sector has a vital role to play in service delivery. Critics of the bank, however, certainly find it difficult to accept that poor people are more likely to use the private sector than those who are better off. Indeed, one look at a teeming government hospital in the region leaves no doubt that it is poor people who rely on public services, however inadequate, and have difficulty raising enough money for a private consultation. Even if private health care is affordable, the quality of care is highly variable.

“In South Asia you have no accreditation,” argues Richard Skolnik, “no continuing medical education, and medical associations who barely know who belongs to them and who doesn’t. You have a highly unempowered population, huge shares of which are illiterate, and if you think studies suggest that there are problems with outcome based medicine in the US, what do you think the illiterate people of India, or Nepal, or Pakistan do about their health care?”

A final blight on the region is the constant whiff of corruption. A real concern is that loan monies end up with subcontractors, who do nothing more than bolster their bank accounts. The bank accepts that corruption is difficult to weed out, and it is often criticised for being very concerned about lending money and then barely making an effort to ensure that it has been appropriately used. This is an aspect of its lending that the bank is hoping to strengthen, and government officials in South Asia now readily testify to the thoroughness of visits by bank staff. But as anyone familiar with the region will know, unless every detail of every transaction is monitored, the culture of corruption is difficult to curtail.

For a better understanding of the challenges posed by the region, I visited bank projects in Bangladesh, India, and Pakistan, and spoke with bank employees, politicians, and other health workers.

Bangladesh: donor country

Bangladesh is flat, watery, and full of rickshaws. It is also poverty stricken—half the population lives below the poverty line, if not on the water line. Bangladesh, formerly East Pakistan, gained independence in 1971 and has the ninth largest population in the world. Around 120 million people pack into 144 000 square kilometres—the highest population density for any country. The World Bank is positive about Bangladesh, and feels that some of its best work in the health sector is being done there. Indeed, Bangladesh has reduced fertility rates and infant mortality faster than some of its neighbours, notably Pakistan. The fertility rate has halved since the early 1970s and is now less than 4.0 per woman aged 15-49.

Two crucial factors in this advance have been the healthy relationship between bank staff and government officials and the heavy involvement of non-government organisations in the delivery of health care. The bank heads a consortium of 10 donors that funds around a third of the health ministry’s budget, with over 30 multilateral and bilateral organisations supporting the ministry of health.

“In Bangladesh you have the world’s ultimate sector-wide approach to foreign assistance in health,” claims Richard Skolnik. “That is, every donor, their mother, their uncle, and cousin, is working together to help finance the Bangladesh five year programme in health, which has 67 components and includes every programme that the Bangladesh central government is financing.”

Brad Herbert, the bank’s team leader for the health, nutrition, and population sector in Bangladesh, believes that decentralisation is the key: “I feel it was right. We’ve a large staff here, which positions us well and makes us more operational. Our main focus is addressing the needs of government and supporting them. We’ve moved a long way since the early 1970s, when programmes were vertical. Now they’re horizontal, which is better.” Bank employees “in the field” believe they are now more empowered and used less for rubber stamping the policies emanating from the bank’s headquarters in Washington.

Another benefit of decentralisation, Herbert argues, is that governments no longer feel intimidated and find it easier to negotiate with bank staff. In fact, he believes that the Bangladeshi government is more progressive than the bank in the health sector: “It’s easy to negotiate with the government, but difficult to negotiate with the bank.” The danger is that when the bank and government become too close, the government can be paralysed, he says, citing the bank’s experience in Hungary, where he was previously stationed: “It’s not our money, not our project, and we should be there to assist,” he says, rather than to run the ministry of health.

Alleviating poverty

The primary objective in Bangladesh is the alleviation of poverty. Focusing on the health needs of women, children, and poor people, the bank hopes to help reinforce basic services, introduce a sector-wide agenda, and enhance the national drug policy. All these are key elements of the government’s health and population sector programme 1998-2003.2

In 1998 the Bangladeshi minister for health and family welfare, Salahuddin Yousuf, wrote to James Wolfensohn, president of the World Bank, outlining why more funding from donors was necessary: “Persistent poverty and gender differentials continue to undermine the effort to achieve better help for the people of Bangladesh .... Women constitute almost half of the Bangladesh population. But because of widespread illiteracy among the population as a whole and women in particular, inadequate female participation in development activities and, above all, the age old sex discrimination, it is difficult to ensure their active participation in health and health related development activities.”

Past funding was focused on specific health measures, but the bank believes that this approach is too costly, especially as financial support from donors is declining and is not sustainable. A wider, three pronged strategy has been negotiated with the government: improving health services for women and children; reorganising the public sector to provide a more cost effective service; and broadening health reform through decentralisation, improved cost recovery, and greater input from non-governmental organsations and the private sector.

Non-governmental organisations already have a vital role in Bangladesh, perhaps more so than in any other country. Their strength, they claim, lies in their flexibility, as they can work in remote and sensitive areas, where government organisations are less welcome. Some 500 non-governmental organisations operate in the health, nutrition, and population sector in Bangladesh, working mainly in supervising microcredit and in women’s empowerment programmes. Indeed, educating women and mobilising the female workforce have been key to Bangladesh’s improvement, especially on the background of a culture that traditionally limits opportunities beyond the home for women.

Bangladesh is divided up into 489 localities known as thanas, and non-governmental organisations work in most of these. Among the best known is the Bangladesh Rural Advancement Committee, which reaches around 17 million people. The non-governmental organisations don’t want to simply be used as implementation agencies; they want to be fully integrated into the health programme, and they have gone some way towards achieving this in Bangladesh. Indeed the government’s policy is to encourage the involvement of non-governmental organisations and the private sector in the delivery of health care.

The World Bank’s main method of lending is by funding projects. The bank’s fourth population and health project in Bangladesh, which has disbursed around $780m over six years—$190m from the bank, $282m from other donors, and $310m from the Bangladeshi government—was reviewed by a bank mission in June 1998, and the findings were mixed. Progress had been made from 1992 to 1998 in lowering fertility, reducing infant mortality, combating communicable diseases, and raising life expectancy, but other areas, such as maternal health services, programme efficiency, and human resources development, were deemed to be “missed opportunities.” Underperformance was blamed on a mix of factors including the inefficiency of parallel service delivery, systems for health and family welfare, overcentralisation, and a lack of institutional autonomy. Although the project was thought to be satisfactory overall, another failing was that it took six and a half years to complete, rather than five as planned.

Another major initiative has been the Bangladesh integrated nutrition project, which is scheduled to run from 1995 to 2001 and amounts to $67.3m in lending. It is an example of how coordination can be achieved at national, community, and intersectoral levels. The government believes that it has demonstrated the benefits of social mobilisation, with villages becoming self sufficient in producing extra food.

Good and evil

Bruce Currey, a public health doctor in Dhaka, is unconvinced by the bank’s strategy. He is worried about the outcome measures used by the bank, in that they tend to be financial rather than health oriented. Despite the bank’s optimism he remains sceptical about the sustainability of projects: “What happens when food supplementation stops in the nutrition programme? Patients die.”

The bank is still prepared to bully governments into health policy reform, especially through its liking for the sector-wide approach, argues Kent Buse from the health policy unit of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.3 He states that “the bank, in 1996, in consultation with other consortium members, indicated it would not proceed with processing a further credit for health and population activities in Bangladesh until the government produced a strategy that set out an agenda for substantive reforms. With guidance from the bank and other donors, the ministry of health prepared the requisite strategy document.” The bank, it seems, is most responsive to countries that are ready to implement its policies.

Muhammad Ali, the secretary of state of the ministry of health and family welfare, is more positive about the bank’s role in Bangladesh. He believes that progress is being made with the help of the bank, and that many of Bangladesh’s problems have arisen from poor coordination in the delivery of health care, either because of too many projects or through the ministry being divided, at all levels, between health and family planning services. The family planning branch has been better coordinated up to now, resulting in more progress—thanks to strong donor support, good understanding between government and the non-governmental organisation sector, and overcoming traditional barriers like the conservatism of religious leaders, women’s illiteracy, and women’s unemployment.

Ali is convinced that future prospects are good because of the government’s collaborative relationship with the bank. None the less, he feels that the bank’s role is changing: “The bank is responding to the changing needs of the country. Before, it used to focus on structural investment, but now it concentrates on programmes. It is a more accountable system, and they are trying to involve the local community. The bank is trying to bring about quality.” Although Ali’s words may have been carefully chosen (a senior bank employee was present when I spoke to him), it is clear that the bank and the Bangladeshi government work closely on policies, with the inherent dangers of such close collaboration that Brad Herbert outlined earlier.

Conclusion

South Asia’s health problems are compounded by weak public sector health care, corruption, and a lack of accountability. While common themes run through the region, the bank has historically had different approaches to healthcare delivery in Bangladesh, India, and Pakistan, largely depending on the bank’s interaction with officials from each country. In Bangladesh, the bank has found officialdom to be receptive to its policies. But Bangladesh remains largely dependent on its unique donor consortium, and although there has been some progress, critics are unconvinced that sustainability is a real prospect.

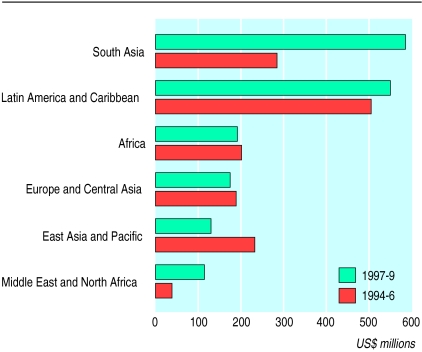

Figure.

Variation in annual lending in the health, nutrition, and population sector. Adapted from Sector strategy: Health, nutrition, and population1

Table.

Health indicators in South Asia. Figures are for 1995 unless stated otherwise. Adapted from Sector strategy: health, nutrition, and population1

| Country | Gross national product per capita (US$) | Human development

|

Health indicators

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population (millions) | Population growth rate (%) | % of under 5s malnourished 1985-95 | % of population living in cities 1985-95 | % with access to safe water 1985-95 | Total fertility rate | % change in fertility rate 1980-95 | Maternal mortality 1990-5 (per 100 000 live births) | Infant mortality (per 1000 live births) | ||||

| Bangladesh | 240 | 119.8 | 1.6 | 68 | 18 | 83 | 3.5 | −43 | 887 | 115 | ||

| India | 340 | 929.4 | 1.7 | 53 | 27 | 63 | 3.2 | −35 | 437 | 69 | ||

| Pakistan | 460 | 129.9 | 2.9 | 40 | 35 | 60 | 5.3 | −24 | 340 | 91 | ||

| Sri Lanka | 700 | 18.1 | 1.2 | 38 | 22 | 57 | 2.3 | −34 | 30 | 16 | ||

Figure.

A Bangladeshi fishing village

Figure.

Bangladeshi women making nutritional supplements

References

- 1.Sector strategy: health, nutrition, and population. Washington, DC: World Bank; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Health and population sector programme 1998-2003. Dhaka: Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buse K, Gwin C. The World Bank and global cooperation in health: the case of Bangladesh. Lancet. 1998;351:665–669. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)11453-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]