Nearly 4.5 million adults live with chronic liver disease and cirrhosis in the United States alone and its incidence is rising.1 In 2019, age-adjusted cirrhosis-related mortality was highest among US adults of American-Indian/Alaska-Native (AI/AN) and Hispanic backgrounds and represented the 4th and 7th leading causes of death in these populations.2 There is a clear need to ensure that novel interventions for cirrhosis are studied in patients with the highest disease burden; however, minorities are often underrepresented in clinical trials.3 Given these trends, we aimed to examine the rates of reporting of sex, race, and ethnicity of participants in high-impact randomized clinical trials (RCTs) of adults with cirrhosis.

We conducted a systematic review of RCTs involving adults (≥ 18 years) with cirrhosis published in 12 leading medicine and gastroenterology journals from 2000 to 2021, consistent with prior work.4 Journals were considered high impact if they reported an impact factor of at least 10 in 2022. The general medicine journals were New England Journal of Medicine, Journal of the American Medical Association, Lancet, and British Medical Journal. The gastroenterology journals were Gastroenterology, Journal of Hepatology, Gut, Hepatology, Lancet Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics, and American Journal of Gastroenterology.

We collected data on sex, race (reported as White, Black, Asian, AI/AN, or Native-Hawaiian/Pacific-Islander), and ethnicity (reported as Hispanic or Latino). We compared the reported findings with the expected prevalence of cirrhosis for the respective populations.5 We examined differences in enrollment by sex, race, and ethnicity between US-only and international trials. Full methods are reported in the Supplementary Methods.

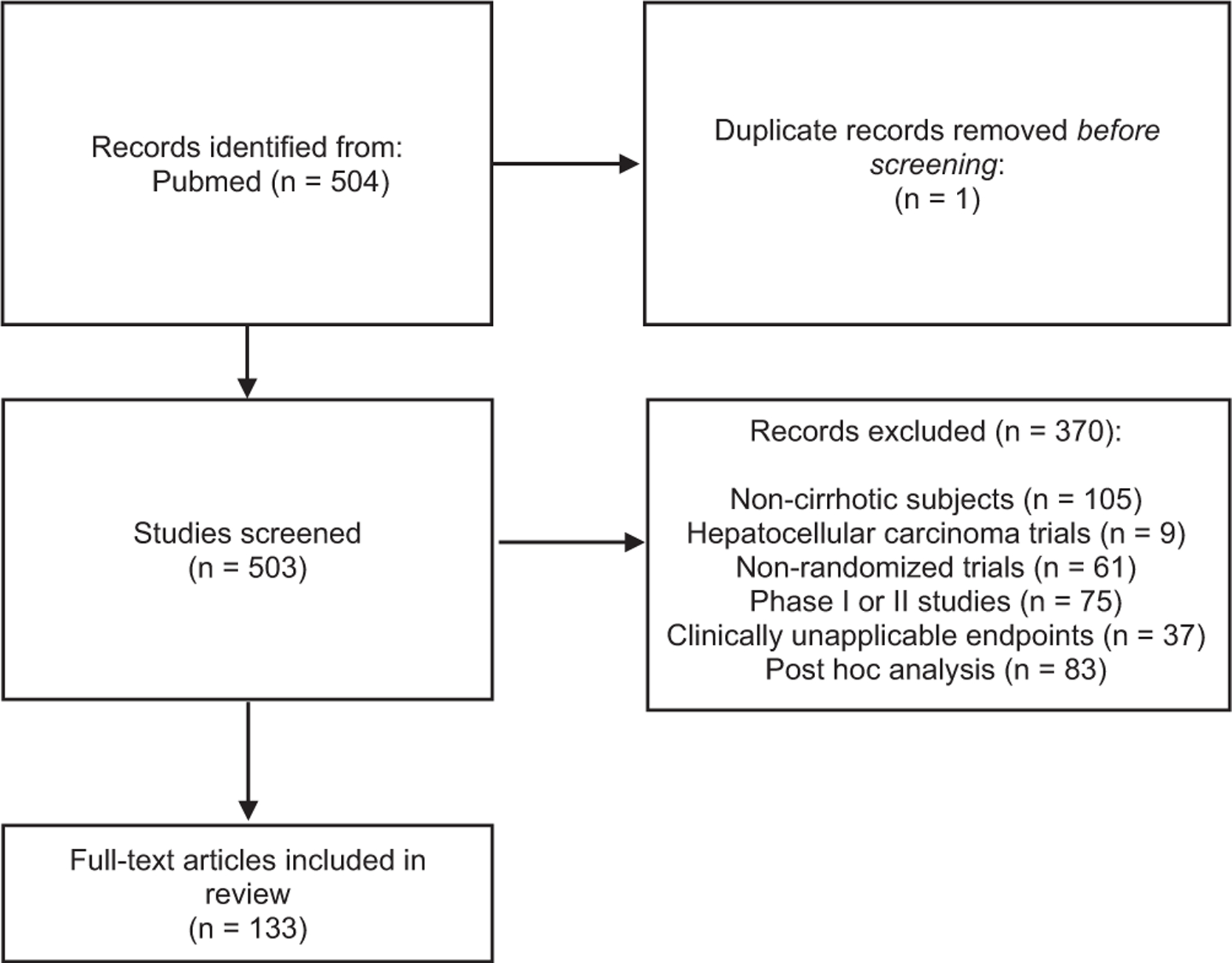

The search revealed 503 trials. Studies not exclusively investigating patients with cirrhosis (n = 105) were excluded, as were studies focusing on patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (n = 9), nonrandomized trials (n = 61), pre–phase 3 studies (n = 75), trials with clinically unapplicable end points (n = 37), and post hoc studies (n = 83) (Figure 1). In total, 133 RCTs (n = 20,870 participants) were selected for further abstraction and analysis. Most studies were drug trials (n = 89; 66.9%), followed by device (n = 38; 28.6%) and behavioral intervention (n = 6; 4.5%) trials. In total, there were 15 US RCTs and 118 international RCTs (Supplementary Table 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of study selection.

All 15 US trials reported sex of participants, with women comprising 33% (n = 1098) of study participants. Based on published US demographic data, female trial enrollment was greater than the gender composition of cirrhosis cases in the US (33% vs 27%; P < .001).5 In total, 8 out of the 15 (53%) US trials reported data on the race and/or ethnicity of trial participants (Table 1). In these trials, study participants (n = 2449) were characterized as follows: White (n = 2073; 84.6%), Black (n = 179; 7.3%), Asian (n = 27; 1.1%), Hispanic or Latino (n = 165; 6.7%), or other (n = 57; 2.3%), with only 3 US trials explicitly reporting the inclusion of AI/AN or Native-Hawaiian/Pacific-Islander participants (n = 15; 0.6%). The trial by Pearlman et al6 accounted for 22% of all Black study participants (n = 39). After accounting for study weights, the weighted average of Black participation was 7.1%. Compared with the expected prevalence from national health data, Black (29% of cirrhosis cases in the United States vs 7% in RCTs; P < .001) and Hispanic or Latino (34% of cirrhosis cases in the United States vs 7% in RCTs; P < .001) participants were underrepresented in the US RCTs.5

Table 1.

Characteristics of US Cirrhosis Clinical Trials Reporting Data on Race and Ethnicity of Study Participants (n = 8)

| Sex (n, % total) |

Race (n, % total) |

Ethnicity (n, % total) |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author | Year | Intervention | Total enrolled | Male | Female | White (33% of US cases with cirrhosis) | Black (29% of US cases with cirrhosis) | Asian | American Indian or Alaskan Native | Native Hawaiian/other Pacific Islander | Other | Hispanic/Latino (34% of US cases with cirrhosis) |

| Boyer TD | 2016 | Terlipressin vs albumin for hepatorenal syndrome | 199 | 120 (60.3) | 79 (39.7) | 177 (88.9) | 12 (6.0) | 5 (2.5) | 2 (1) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (1.5) | 32 (16.1) |

| Curry MPa | 2015 | Sofosbuvir and velpatasvir for decompensated HCV cirrhosis | 267 | 186 (69.7) | 81 (30.3) | 239 (89.5) | 17 (6.4) | 5 (1.9) | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.4) | 3 (1.1) | 39 (14.6) |

| Pearlman BL | 2015 | Simeprevir/sofobuvir for compensated HCV cirrhosis | 82 | 53 (64.6) | 29 (35.4) | 43 (52.4) | 39 (47.6) | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Mullen KD | 2014 | Rifaximin as hepatic encephalopathy maintenance therapy | 392 | 233 (59.4) | 159 (40.6) | 351 (89.5) | 17 (4.3) | NR | NR | NR | 24 (6.1) | NR |

| Bass NMa | 2010 | Rifaximin for hepatic encephalopathy therapy | 299 | 182 (60.9) | 117 (39.1) | 257 (86.0) | 12 (4.0) | 12 (4.0) | 8 (2.7) | 3 (1.0) | 6 (2.0) | NR |

| Schrier RWb | 2006 | Tolvaptan for hyponatremia | 448 | 262 (58.5) | 186 (41.5) | 374 (83.5) | 34 (7.6) | NR | NR | NR | 9 (2.0) | 31 (6.9) |

| Groszmann RJb | 2005 | Beta-blockers for variceal primary prophylaxis | 213 | 126 (59.2) | 87 (40.8) | 199 (93.4) | 4 (1.9) | 5 (2.3) | NR | NR | NR | 5 (2.3) |

| Morgan TRa,b | 2005 | Colchicine for alcohol-related cirrhosis | 549 | 538 (98.0) | 11 (2.0) | 433 (78.9) | 44 (8.0) | NR | NR | NR | 12 (2.2) | 58 (10.6) |

HCV, hepatitis C virus; NR, data are not reported.

Curry MP (n = 1), Bass NM (n = 1), and Morgan TR (n = 2) included subjects with missing data on race/ethnicity.

Schrier RW, Groszmann RJ, and Morgan TR trials classified Hispanic ethnicity as race.

There was a significantly higher frequency of reporting race and ethnicity in US trials (8/15; 53%) compared with international trials (4/118; 3.4%) (P < .001). All studies with exception of 1 international study reported participant sex.

This systematic review highlights several important findings. Racial and ethnic minorities, particularly those from AI/AN backgrounds, are underrepresented in high-impact US cirrhosis clinical trials. We also highlight the ongoing paucity of reported racial and ethnic demographic data among published cirrhosis clinical trials both in the United States and internationally. These findings limit the generalizability of treatment strategies for chronic liver diseases that are more prevalent in minority communities. Moreover, exclusion of minority patients hinders the ability to improve entrenched differences in liver health outcomes among racial and ethnic groups in the United States and internationally.

In the United States, AI/AN individuals have experienced disproportionately high mortality rates from complications of cirrhosis, thus greater efforts must be taken to ensure these individuals are adequately represented in clinical trials. Contributors to lower enrollment of AI/AN individuals in clinical trials include higher rates of rural living, lower access to treatment centers that are participating as clinical investigation sites, and smaller population size.7 Virtual technology, such as the Project ECHO model, can democratize access to hepatology experts for clinical care and future research opportunities.8

Barriers to clinical trial enrollment of racial and ethnic minority patients with cirrhosis should be systematically investigated to improve representation. Investigators should not assume unwillingness of underrepresented individuals to participate in clinical trials based on historical precedent alone. Study participation may be enhanced by promoting the efforts of Native American Research Centers for Health to support research interests selected and prioritized by the AI/AN communities.9 Community-based outreach efforts may also increase the willingness of minority populations to participate in research.10 Furthermore, governing scientific bodies should make securing funding for potentially high-impact trials contingent on investigators completing follow-up results and providing relevant demographic information.

The study has several limitations. Accurate US population-based estimates of cirrhosis among Asian, AI/AN, or Native-Hawaiian/Pacific-Islander groups are lacking.11 The trial by Pearlman et al6 investigating hepatitis C cirrhosis accounted for more than 20% of all Black participants in the studies included in this review. The underrepresentation of Black individuals in cirrhosis clinical trials may worsen as the burden of hepatitis C decreases in the direct-acting antiviral era. International trials rarely provided racial or ethnic demographic information, which may be related to the homogeneity of included countries. We did not perform a systematic review of ClinicalTrials.gov because we sought to focus on studies published in journals with the highest chance of producing practice change within the field.

Our findings highlight the underrepresentation of racial and ethnic minorities in high-impact cirrhosis clinical trials. These barriers may be overcome by requiring full reporting of demographic data and embracing innovative strategies to improve inclusion in future investigations.

Supplementary Material

Funding

This manuscript was supported by a Clinical, Translational, and Outcomes Research Award from the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease (NNU), Massachusetts General Hospital Physician-Scientist Development Award (NNU), and R03AG074059 (BK).

Abbreviations used in this paper:

- AI/AN

American-Indian/Alaska-Native

- RCT

randomized clinical trials

Footnotes

Supplementary Material

Note: To access the supplementary material accompanying this article, visit the online version of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology at www.cghjournal.org, and at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2022.11.020.

Conflicts of interest

The authors disclose no conflicts.

Contributor Information

PAIGE MCLEAN DIAZ, Division of Gastroenterology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts.

ANANYA VENKATESH, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, Virginia.

LAUREN NEPHEW, Division of Gastroenterology & Hepatology, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, Indiana.

PATRICIA D. JONES, Division of Digestive Health and Liver Services, Department of Medicine, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, Miami, Florida

BHARATI KOCHAR, Division of Gastroenterology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts.

NNEKA N. UFERE, Division of Gastroenterology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts

References

- 1. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/liver-disease.htm.

- 2.Heron M Natl Vital Stat Rep 2021;70:1–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bibbins-Domingo K, et al. JAMA 2022;327:2283–2284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kochar B, et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2021;27:1541–1543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scaglione SM, et al. J Clin Gastroenterol 2015;49:690–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pearlman BL, et al. Gastroenterology 2015;148(4):762.e12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen MS, et al. Cancer 2014;120(Suppl 7):1091–1096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arora S, et al. N Engl J Med 2011;364:2199–2207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. https://www.nigms.nih.gov/Research/DRCB/NARCH/Pages/default.aspx.

- 10.McGuire FH, et al. J Viral Hepat 2021;28:982–993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kardashian A, et al. Hepatology 2022. 10.1002/hep.32743. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.