Abstract

Background:

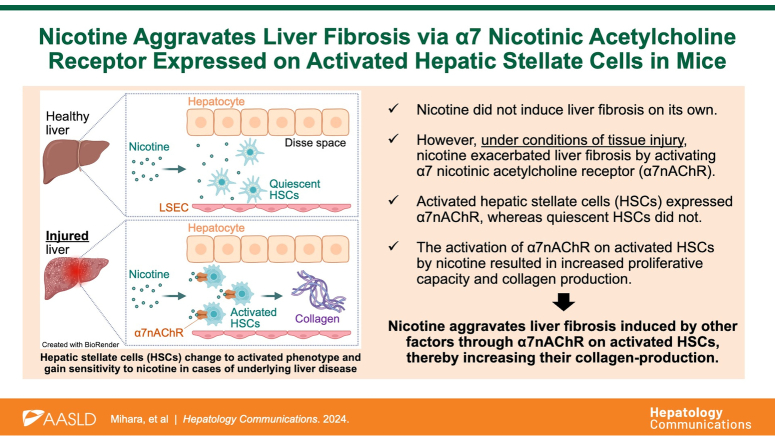

Smoking is a risk factor for liver cirrhosis; however, the underlying mechanisms remain largely unexplored. The α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (α7nAChR) has recently been detected in nonimmune cells possessing immunoregulatory functions. We aimed to verify whether nicotine promotes liver fibrosis via α7nAChR.

Methods:

We used osmotic pumps to administer nicotine and carbon tetrachloride to induce liver fibrosis in wild-type and α7nAChR-deficient mice. The severity of fibrosis was evaluated using Masson trichrome staining, hydroxyproline assays, and real-time PCR for profibrotic genes. Furthermore, we evaluated the cell proliferative capacity and COL1A1 mRNA expression in human HSCs line LX-2 and primary rat HSCs treated with nicotine and an α7nAChR antagonist, methyllycaconitine citrate.

Results:

Nicotine exacerbated carbon tetrachloride–induced liver fibrosis in mice (+42.4% in hydroxyproline assay). This effect of nicotine was abolished in α7nAChR-deficient mice, indicating nicotine promotes liver fibrosis via α7nAChR. To confirm the direct involvement of α7nAChRs in liver fibrosis, we investigated the effects of genetic suppression of α7nAChR expression on carbon tetrachloride–induced liver fibrosis without nicotine treatment. Profibrotic gene expression at 1.5 weeks was significantly suppressed in α7nAChR-deficient mice (−83.8% in Acta2, −80.6% in Col1a1, −66.8% in Tgfb1), and collagen content was decreased at 4 weeks (−22.3% in hydroxyproline assay). The in vitro analysis showed α7nAChR expression in activated but not in quiescent HSCs. Treatment of LX-2 cells with nicotine increased COL1A1 expression (+116%) and cell proliferation (+10.9%). These effects were attenuated by methyllycaconitine citrate, indicating the profibrotic effects of nicotine via α7nAChR.

Conclusions:

Nicotine aggravates liver fibrosis induced by other factors by activating α7nAChR on HSCs, thereby increasing their collagen-producing capacity. We suggest the profibrotic effect of nicotine is mediated through α7nAChRs.

INTRODUCTION

Chronic liver diseases, including cirrhosis, affect approximately 1.5 billion individuals worldwide.1 The liver is a highly regenerative organ that is capable of self-repair, even after the destruction of hepatocytes on a massive scale under inflammation or chemical exposure.2,3 However, fibrosis develops and impairs liver function in patients with severe chronic liver injury.4 Cirrhosis is the final stage of all chronic liver diseases, irrespective of etiology, and it may result in fatal secondary conditions such as portal hypertension and liver cancer.5 The inhibition and reversal of liver fibrosis have been extensively investigated6,7; however, effective therapies or pharmacological interventions have not been developed.

Epidemiological studies have established smoking as a risk factor for liver cancer and cirrhosis1,8,9; however, the underlying mechanisms remain poorly understood. Smoking contains various harmful components, including nicotine, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, tobacco-specific nitrosamines, aldehydes, and carbon monoxide. Among them, nicotine, which is the principal component of tobacco smoke, activates nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) and affects various biological regulatory systems, including the immune and circulatory systems.10,11 The effects of nicotine on the cardiovascular and respiratory systems have been extensively investigated12,13; however, studies on the gastrointestinal system, particularly the liver, are lacking.

The α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (α7nAChR) is a subtype of the nAChRs. nAChRs are ion channel receptors comprising 5 subunits, and α7nAChR is composed of 5 α7 subunits. They were first discovered and studied as receptors expressed on neurons responsible for memory and learning.14,15 In 2003, the α7nAChRs were found to be expressed on immune cells, resulting in anti-inflammatory effects upon activation.16 Since then, its involvement in various immune responses has been actively investigated.17,18 A previous study has reported that α7nAChR-knockout mice exhibited exacerbated renal fibrosis.19 Conversely, other studies have suggested that bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis is alleviated in α7nAChR-knockout mice and that α7nAChR inhibitors suppress cardiac fibrosis in mouse models.20,21 Overall, a consensus has not been reached regarding the role of α7nAChR in fibrosis.

Therefore, our study aimed to investigate whether nicotine promotes liver fibrosis via the α7nAChR and elucidate the underlying mechanisms.

METHODS

Animals

In this study, male C57BL/6J mice (wild-type mice; Sankyo Labo Service, Japan) and B6.129S7-Chrna7 tm1Bay /J mice, which have C57BL/6J mice background (α7nAChR-deficient mice; Strain#: 003232; The Jackson Laboratory, USA), aged 8–11 weeks were used. To exclude the possibility of sex cycle–induced alterations to the immune response, only male mice were used. Furthermore, to minimize potential microbiome effects, these mice were cohoused. The mice were bred under controlled conditions, with a temperature of 25 °C and a 12-hour light/dark cycle with free access to feed (MF, Oriental Yeast Co., Japan) and water. Specifics of the diet composition are shown in Supplemental Table S1, http://links.lww.com/HC9/A931. We used Q-Pla Tip (Sankyo Labo Service, Japan) for bedding and TAR-100E-A (Toyo-riko, Japan) for the caging system. Mice were not fasted before carrying out challenges or assessments. All interventions were made to the mice during the light cycle (8 am to 8 pm). All animal care and experimental procedures were performed in accordance with the Guidelines for Animal Use and Care published by the University of Tokyo and the International Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments guidelines. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Tokyo (approval numbers: P18-123M04, P23-152 and L21-014H02).

To induce liver fibrosis, carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) was intraperitoneally administered twice a week at a dose of 1 mL/kg for 4 weeks. CCl4 was diluted using olive oil. Nicotine (20 mg/kg/d) and methyllycaconitine citrate (MLA, 10 mg/kg/d) were administered using Alzet osmotic pumps according to the manufacturer’s instructions; the doses were chosen based on previous studies.22,23 Both nicotine and MLA were diluted using a saline solution.

HE and Masson trichrome staining

Following euthanasia under deep isoflurane anesthesia, the mice were perfused with saline and 10% buffered formalin for fixation. The livers were extracted, immersed overnight in formalin, and embedded in paraffin. Subsequently, 5-μm sections were prepared and subjected to staining with HE and Masson trichrome stain kits following standard protocols.

Hydroxyproline assay

Hydroxyproline assay was performed according to a previously reported protocol with modifications.24 Briefly, the liver samples were homogenized using a pair of scissors and dried overnight at 42°C. After weighing, the samples were hydrolyzed in 6 N HCl at 121°C under 2 atm. A 50-μL aliquot of the sample was desiccated in a draft chamber and resuspended in 10 μL of distilled water. Next, 100 μL of a solution containing 1.4% chloramine T, 10% 1-propanol, and 0.5 M sodium acetate was added to the samples, which were then incubated for 20 minutes at 25°C. Finally, 100 μL of Ehrlich solution consisting of 1 M p-dimethylaminobenzaldehyde, 70% 1-propanol, and 20% perchloric acid was added, and the samples were incubated for 15 minutes at 65°C. The absorbance of the samples was measured at 550 nm, and the calculated hydroxyproline content was normalized to the dried weight of the samples.

Real-time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from the liver tissue using TRIzol reagent following the manufacturer’s instructions and reverse-transcribed using ReverTra Ace and random primers. The cDNA was denatured at 95°C for 1 minute and amplified through 40 cycles at 95°C for 15 seconds and 60°C for 1 minute using SYBR Green. The primer sets used in this study are listed in Supplemental Table S2, http://links.lww.com/HC9/A931.

Cell culture

Human HSC line LX-2 was obtained from MERCK (SCC064, RRID: CVCL_5792). For the experiments, 1.0×105 cells were seeded in a 60-mm dish and cultured in DMEM with GlutaMAX supplement containing 2% fetal bovine serum, 100 U penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin. LX-2 cells and rat HSCs were treated with TGF-β, nicotine, and MLA for 72 hours.

Cell viability and proliferative measurement

Cell viability and proliferative capacity were assessed using a Cell Counting Kit-8 (Dojindo) per the manufacturer’s instructions. The average cell number of the control group was defined as 100%, and the relative cell viabilities for each treatment group and series were calculated.

Isolation of mouse and rat primary HSCs

HSCs were isolated following a previously published protocol with modifications.25 Briefly, the inferior vena cava was cannulated, and the hepatic superior vena cava was ligated along with the portal vein. The liver was then perfused with saline solution to clear the blood, followed by digestion with pronase and collagenase solutions to facilitate liver digestion. The harvested cells were centrifuged at a low speed (50g) to precipitate hepatocytes. The supernatants were centrifuged at a high speed (600g) to obtain nonparenchymal cells. The HSCs were isolated through density gradient centrifugation using OptiPrep.

Chemicals and equipment

All chemicals and equipment used in this study are listed in Supplemental Table S3, http://links.lww.com/HC9/A931 with manufacturers.

Statistics and data

All results are presented as scatter plots with means. The data were subjected to statistical analysis using Student t test for comparisons between 2 groups and a one-way ANOVA followed by Sidak test for comparisons among three or more groups. We used two-way ANOVA followed by the Sidak test for weight comparisons over time. Results with p<0.05 were considered statistically significant. We used “tend to” for differences with p-values >0.05 but with some increase or decrease in the mean value. All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism9 software.

RESULTS

Nicotine exacerbates CCl4-induced liver fibrosis via the α7nAChR

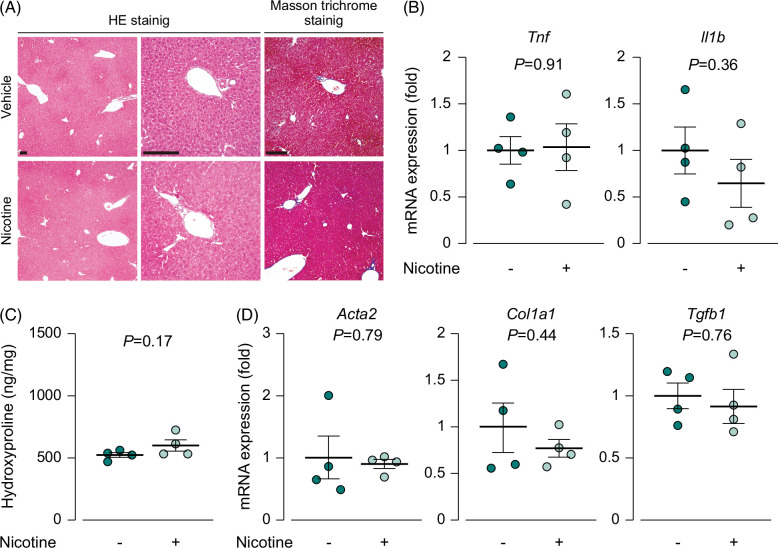

To investigate the effect of nicotine on the liver, we continuously exposed wild-type mice to nicotine for 4 weeks and compared the levels of inflammation and fibrosis to those in the control group. The histological analysis of liver sections after HE staining showed no changes in the liver morphology or infiltration of inflammatory cells in the nicotine-treated group (Figure 1A). Similarly, the mRNA expression of inflammatory cytokines was similar between the nicotine-treated and control groups (Figure 1B). Furthermore, Masson trichrome staining of liver sections and hydroxyproline assay revealed the absence of fibrosis in the nicotine-treated group (Figure 1A, C). The mRNA expression of profibrotic genes remained unchanged after nicotine treatment (Figure 1D). These findings suggest that the continuous administration of nicotine alone does not trigger inflammation or fibrosis in the liver.

FIGURE 1.

Nicotine by itself did not induce inflammation or fibrosis in the liver. (A) Images of HE and Masson trichrome staining of the liver, scale bars=100 µm; (B) mRNA expression of the inflammatory cytokines Tnf and Il1b (N=4); (C) hydroxyproline content in hydrolyzed liver samples (N=4); (D) mRNA expression of the profibrotic genes Acta2, Col1a1, and Tgfb1 (N=4). Each data point is presented as a plot and the means with the SEM are shown as bars. The data were subjected to statistical analysis using Student t test. Abbreviation: HE, hematoxylin and eosin.

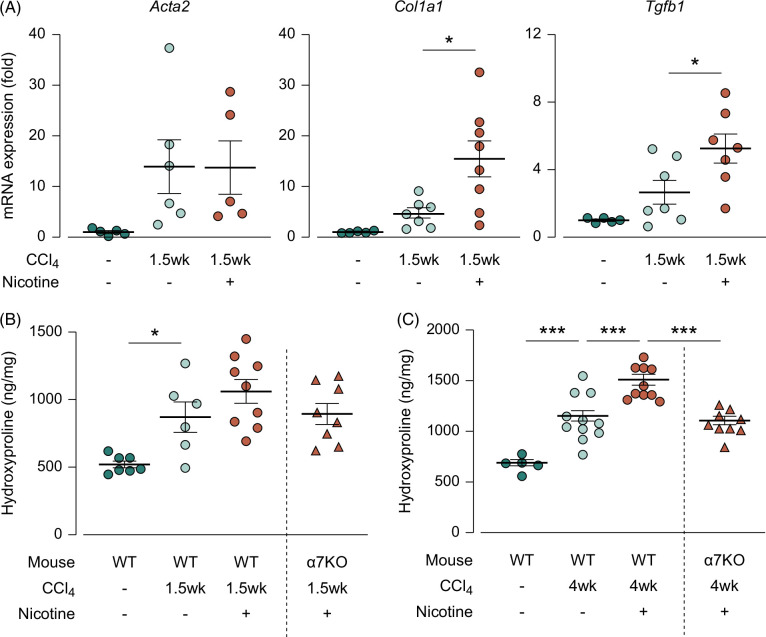

We considered the possibility that nicotine itself did not evoke fibrosis or inflammation but rather promoted fibrosis caused by other factors. Accordingly, we continuously administered nicotine to CCl4-induced liver fibrosis model mice and examined its effects. Fibrosis was evaluated in 2 stages: the fibrosis-progression stage (1.5 wk) and the fibrosis-completion stage (4 wk). These 2 stages were defined using the overtime hydroxyproline assay (Supplemental Figure S1, http://links.lww.com/HC9/A931).

In the progression stage, the mRNA expression of profibrotic genes increased in response to CCl4 treatment; they were further increased by nicotine treatment with statistical significance (Figure 2A, from 4.60 to 15.4 for Col1a1 and from 2.65 to 5.25 for Tgfb1; p<0.05). Moreover, the hydroxyproline assay showed a significant increase in liver collagen levels in the CCl4 group during the fibrosis-progressing stage compared to the control group. Nicotine tended to exacerbate the increase, but no significant differences between CCl4 group and CCl4+ nicotine group were observed (Figure 2B, p =0.31). In the fibrosis-completion stage, a notable increase in collagen level was observed in the CCl4-induced liver fibrosis model mice compared with that in the control group, with nicotine administration leading to further significant increases (Figure 2C, from 1068 to 1521; p<0.001). This fibrosis-promoting effect of nicotine tended to be low in the α7nAChR-deficient mice in the fibrosis-progression stage (Figure 2B, from 1060 in wild type to 893 in α7nAChR-deficient mice; p=0.35) and absent in the fibrosis-completion stage (Figure 2C, from 1521 in wild type to 1079 in α7nAChR-deficient mice; p<0.001). These results suggest that although nicotine did not induce fibrosis when administered alone, it promoted fibrosis induced by other factors via the α7nAChR.

FIGURE 2.

Nicotine exacerbated CCl4-induced liver fibrosis via the α7nAChR. (A) The mRNA expression of the profibrotic genes Acta2, Col1a1, and Tgfb1 in the liver during the fibrosis-progression stage (N=4–7), (B) hydroxyproline content in hydrolyzed liver samples during the fibrosis-progression stage (N=6–9), (C) hydroxyproline content in hydrolyzed liver samples during the fibrosis-completion stage (N=5–11). * p<0.05, *** p<0.001. Each data point is presented as a plot and the means with the SEM are shown as bars. The data were subjected to statistical analysis using one-way ANOVA followed by the Sidak test. Abbreviations: CCl4, carbon tetrachloride; KO, knockout; WT, wild type.

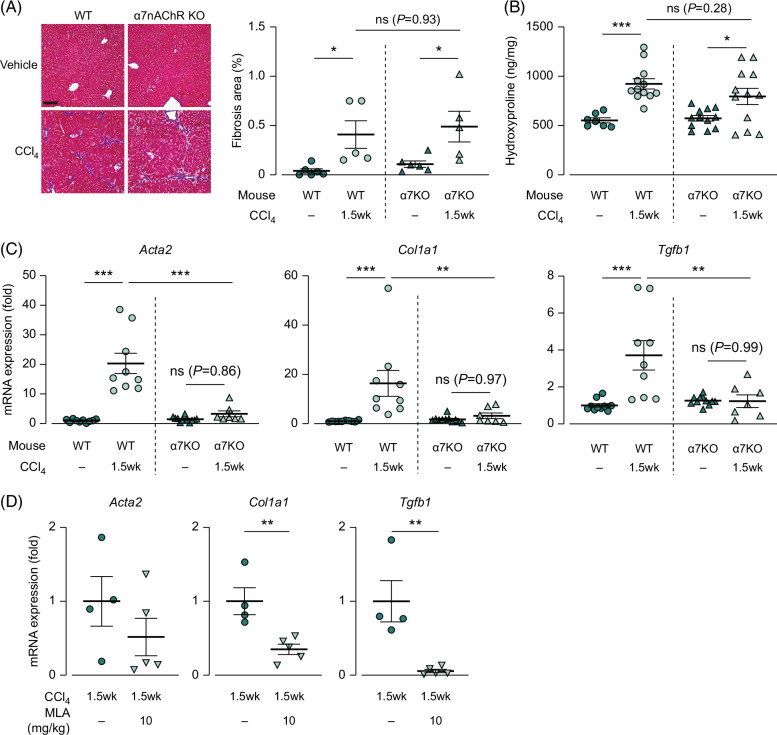

CCl4-induced liver fibrosis is alleviated during genetic and pharmacological inhibition of α7nAChR

To investigate the direct involvement of α7nAChR in liver fibrosis, we generated a CCl4-induced liver fibrosis model with genetic or pharmacological inhibition of α7nAChR expression under no nicotine treatment. α7nAChR-deficient mice showed a significantly lower weight loss than the wild-type mice (Supplemental Figure S2, http://links.lww.com/HC9/A931). During the fibrosis-progression stage, Masson trichrome staining revealed a statistically significant increase in the fibrotic area following CCl4 treatment, but no significant differences were observed between wild-type and CCl4-treated α7nAChR-deficient mice (Figure 3A). Similarly, the hydroxyproline assay showed no significant differences between CCl4-treated wild-type and α7nAChR-deficient mice (Figure 3B). However, the mRNA expression of the profibrotic genes was significantly upregulated following CCl4 treatment in the wild-type mice, and this upregulation was significantly suppressed in the α7nAChR-deficient mice (Figure 3C, from 20.4 in wild type to 3.31 in α7nAChR-deficient mice for Acta2 with p<0.0001, from 16.3 to 3.18 for Col1a1 with p<0.01, and from 3.71 to 1.23 for Tgfb1 with p<0.01). Additionally, the α7nAChR antagonist, MLA, effectively downregulated the expression of profibrotic genes in CCl4-treated wild-type mice (Figure 3D, from 1.00 to 0.35 for Col1a1 and from 1.00 to 0.06 for Tgfb1 by MLA; p<0.01).

FIGURE 3.

Upregulated expression of profibrotic genes induced by CCl4 was suppressed by genetic and pharmacological inhibition of α7nAChR expression during the fibrosis-progression stage. (A) Images of Masson trichrome staining of the liver (N=5–6), scale bars=100 µm, (B) hydroxyproline content in hydrolyzed liver samples during the fibrosis-progressing stage (N=7–12), (C, D) the mRNA expression of the profibrotic genes Acta2, Col1a1, and Tgfb1 in the liver during the fibrosis-progression stage with genetic and pharmacological inhibition of α7nAChR expression (N=7–11, 4–5). * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001. Each data point is presented as a plot and the means with the SEM are shown as bars. The data were subjected to statistical analysis using (A–C) one-way ANOVA followed by the Sidak test and (D) Student t test. Abbreviations: CCl4, carbon tetrachloride; KO, knockout; MLA, methyllycaconitine citrate; α7nAChR, α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor; WT, wild type.

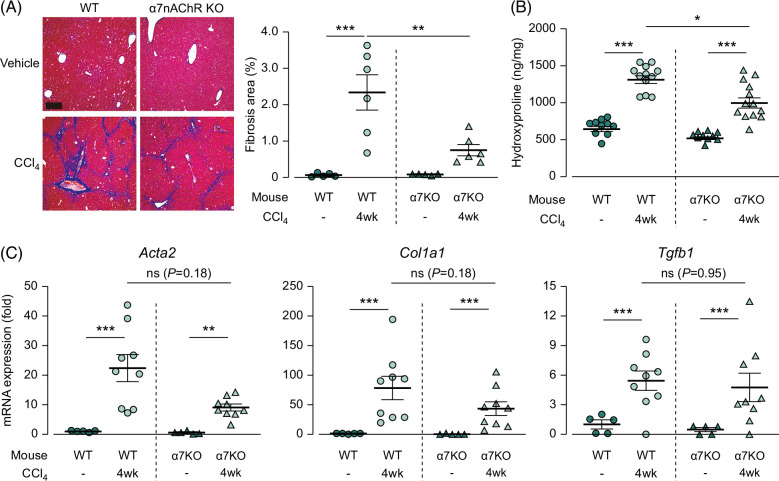

In contrast, during the fibrosis-completion stage, Masson trichrome staining revealed a decrease in the fibrotic area in the α7nAChR-knockout mice compared with that in the wild-type mice (Figure 4A, 2.33% in wild type and 0.75% in α7nAChR-deficient mice; p<0.01). The hydroxyproline assay revealed a similar trend (Figure 4B, 1281 in wild type and 995.4 in α7nAChR-deficient mice; p<0.05). However, the mRNA expression of profibrotic genes did not significantly differ between the CCl4-treated wild-type and α7nAChR-deficient mice (Figure 4C). These results indicate that α7nAChR deficiency suppresses the mRNA expression of profibrotic genes during the fibrosis-progression stage, leading to a reduction in the collagen protein levels during the fibrosis-completion stage.

FIGURE 4.

Upregulated collagen content in the liver induced by CCl4 was suppressed in α7nAChR-deficient mice during the fibrosis-completion stage. (A) Images of Masson trichrome staining of the liver (N=5–6), scale bars=100 µm. (B) Hydroxyproline content in hydrolyzed liver samples during the fibrosis-completion stage (N=10–13). (C) mRNA expression of the profibrotic genes Acta2, Col1a1, and Tgfb1 in the liver during the fibrosis-progression stage (N=5–9). * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001. Each data point is presented as a plot and the means with the SEM are shown as bars. The data were subjected to statistical analysis using one-way ANOVA followed by the Sidak test. Abbreviations: CCl4, carbon tetrachloride; KO, knockout; α7nAChR, α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor; WT, wild type.

α7nAChR is expressed on activated HSCs but not on quiescent HSCs

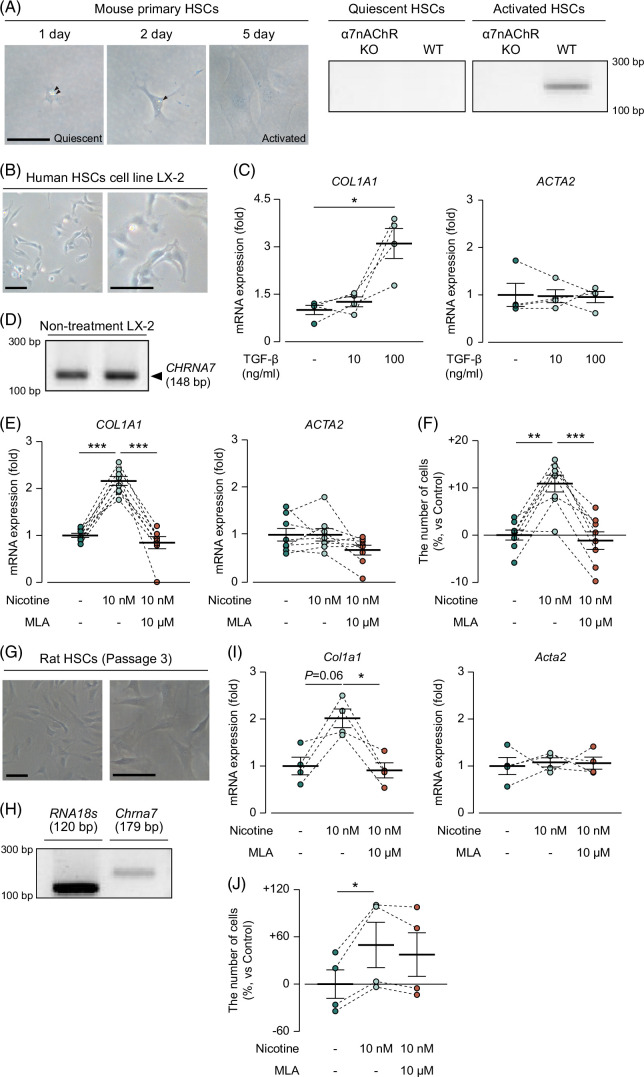

Liver fibrosis is predominantly driven by collagen production from HSCs.26 We therefore hypothesized that HSCs express α7nAChR, and nicotine stimulates the expressed α7nAChR, which subsequently promotes liver fibrosis. To investigate the expression of α7nAChR in HSCs, we isolated HSCs from wild-type mice. One day after seeding, we observed the accumulation of fat droplets, which is the characteristic of quiescent HSCs (Figure 5A). Therefore, quiescent and activated HSCs show distinct phenotypes; therefore, we obtained activated HSCs by culturing them on plastic culture dishes, as HSCs gradually become activated upon culturing on plastic dishes.27 After 5 days of culture, we confirmed the disappearance of fat droplets (Figure 5A). Accordingly, we defined HSCs that were obtained 1 day after seeding as quiescent HSCs and those obtained after 5 days as active HSCs. Subsequently, we assessed the mRNA expression of α7nAChR in quiescent and activated HSCs. We found no bands for α7nAChR in quiescent HSCs but detected 1 band for α7nAChR in the activated HSCs (Figure 5A, Supplemental Figure S3A, http://links.lww.com/HC9/A931).

FIGURE 5.

Activated HSCs expressed α7nAChR, and its activation promoted cell proliferation and collagen production in HSCs. Morphological observations of mouse primary HSCs cultured on plastic coats for 5 days and their mRNA expression of Chrna7, scale bars=50 µm. (B) Morphological observations of LX-2 cells, scale bars=100 µm. (C) mRNA expression of COL1A1 and ACTA2 in LX-2 treated with TGF-β (N=4). (D) mRNA expression of CHRNA7 in LX-2. (E) mRNA expression of COL1A1 in LX-2 treated with nicotine and MLA. (F) Cell viability rates of LX-2 treated with nicotine and MLA (N=8). (G) Morphological observations of rat HSCs. scale bars=100 µm. (H) Chrna7 mRNA expression in rat HSCs. (I) Col1a1 mRNA expression in rat HSCs treated with nicotine and MLA (N=4). (J) Cell viability rate of rat HSCs treated with nicotine and MLA (N=4). * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001. Each data point is presented as a plot and the means with the SEM are shown as bars. The results of the same series are connected by a line. The data were subjected to statistical analysis using one-way ANOVA followed by the paired Sidak test. Abbreviations: KO, knockout; LX-2, LX-2 human hepatic steallate cell line; MLA, methyllycaconitine citrate; α7nAChR, α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor; WT, wild type.

Owing to the limited amount of HSCs that could be obtained from a single mouse, it was difficult to obtain a sufficient number of cells for the experiments. Therefore, we used the human HSCs cell line LX-2 for further investigation. Morphological observations revealed that LX-2 cells had no fat droplets (Figure 5B). During the forced activation of HSCs with TGF-β, 100 ng/mL was identified as the concentration that could elicit an effect on LX-2 cells based on the increased mRNA expression of COL1A1 (Figure 5C, 1.00 in control and 3.10 in TGF-β 100 ng/mL; p<0.05); however, the mRNA level of ACTA2, which is a marker of HSCs activation, did not change (Figure 5C). These findings suggest that LX-2 cells exhibit an activated phenotype even without stimulation. Next, we examined the expression of α7nAChR in LX-2 cells and observed a band indicating the mRNA expression of α7nAChR (Figure 5D, Supplemental Figure S3B, http://links.lww.com/HC9/A931). We also reanalyzed our previous RNAseq results of LX-2 (PRJDB17392) to comprehensively evaluate the expression levels of nAChR family subunits and found that α7nAChR was the third most highly expressed subunit (Supplemental Figure S4, http://links.lww.com/HC9/A931). These results demonstrated that activated HSCs expressed α7nAChR, and LX-2 could be used instead of activated HSCs.

α7nAChR activation promotes collagen production capacity

To investigate whether nicotine promotes collagen production through α7nAChR activation in activated HSCs, we treated LX-2 cells with nicotine and the α7nAChR antagonist MLA. We measured the mRNA expression of COL1A1 and ACTA2 and cell proliferative capacity. We observed that nicotine significantly increased COL1A1 mRNA expression at 10 nM (Figure 5E, from 1.00 to 2.16; p<0.001); however, this increase in COL1A1 expression was significantly suppressed by MLA treatment (Figure 5E, from 2.16 to 0.85 by MLA; p<0.001). Nicotine and MLA did not induce any change in ACTA2 mRNA expression (Figure 5E). Moreover, nicotine significantly enhanced cell proliferation, and MLA significantly suppressed the upregulation (Figure 5F, +0.00% in the control group, +10.9% in the nicotine group, −1.16% in the nicotine+MLA group; p<0.01 for the control vs. nicotine, p<0.001 for nicotine vs. nicotine+MLA). MLA was used at concentrations that were confirmed to be noncytotoxic (Supplemental Figure S5, http://links.lww.com/HC9/A931).

Finally, we examined whether nicotine had the same effects as described above in rat HSCs. As evidenced by the disappearance of fat droplets (Figure 5G), rat HSCs were activated after passaging. Consistent with Figure 5A, Chrna7 expression in rat HSCs was observed (Figure 5H, Supplemental Figure S3C, http://links.lww.com/HC9/A931). Col1a1 mRNA expression was increased by 10 nM nicotine (from 1.00 to 2.02; p=0.06), and MLA administration significantly suppressed it (Figure 5I, from 2.02 to 0.91; p<0.05), while Acta2 mRNA expression was not changed by nicotine or MLA treatment (Figure 5I). Nicotine promoted cell proliferation (Figure 5J, +49.6% in proliferative rate; p<0.05 for control vs. nicotine).

These findings suggest that the activation of α7nAChR expressed on activated HSCs promotes proliferation and increases COL1A1 mRNA expression and subsequently collagen production.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we demonstrated that nicotine did not induce liver fibrosis on its own. However, under conditions of tissue injury, nicotine exacerbated liver fibrosis by activating α7nAChRs. Furthermore, activated HSCs expressed α7nAChR, whereas quiescent HSCs did not, and the activation of α7nAChR resulted in increased proliferative capacity and collagen production. These findings suggest that smoking may promote fibrosis by inducing a secondary stimulus on HSCs activated by a primary one from an underlying disease, such as hepatitis, through the activation of α7nAChRs. Although this study did not exactly mimic smoking as we did not use the other harmful chemicals found in tobacco, our results reveal some of the adverse effects of smoking on the liver. In Figure 1, nicotine administration in healthy mice did not cause inflammation and fibrosis in the liver. However, in actual smoking, other components, such as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and nitrosamines, are also ingested while smoking. Since the liver may be injured by these components, it should not be assumed that smoking has no adverse effects on healthy livers.

Epidemiological studies have consistently demonstrated a significantly high OR of developing cirrhosis among smokers with underlying diseases.28,29 However, the underlying mechanisms through which these comorbidities exacerbate the adverse effects of smoking on the liver remain unknown. In our in vivo experiments, nicotine showed no effects on the liver under normal conditions when HSCs were quiescent but exhibited a profibrotic effect under the conditions of tissue injury when HSCs were active. Consistent with this, the fibrosis-promoting effect of nicotine was observed in vitro in LX-2 cells that are phenotypically similar to and represent active HSCs. Based on these findings, we hypothesized that the underlying disease stimulates a phenotypic shift in HSCs from the quiescent to activated state, accompanied by the expression of α7nAChR. This phenotypic shift could be responsible for the increased sensitivity to nicotine intake via smoking and the promotion of collagen production from activated HSCs (Supplemental Figure S6, http://links.lww.com/HC9/A931). Our findings provide a scientific rationale for the observed epidemiological trends and highlight the detrimental effects of smoking on liver health.

The liver receives innervation from the vagus nerve; thus, α7nAChR on HSCs can be further activated by ACh released from nerve endings that extend throughout the liver. These nerves in the liver primarily travel toward the central vein through the Disse Space. As the nerve endings are close to the HSCs,30 ACh released from nerve endings could affect α7nAChR expressed on activated HSCs. To examine this possibility, a model needs to be established by performing the vagotomy of the hepatic branch and inducing liver fibrosis.

α7nAChR is known for its role in systemic neurotransmission and neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory effects, suggesting the beneficial effects of α7nAChR.31 However, this study revealed that α7nAChR exerts adverse effects, such as promoting liver fibrosis. Therefore, the activation of α7nAChR seems to have contradictory effects. However, fibrosis is also necessary for wound healing; thus, these contradictions can be resolved by considering that the fibrosis driven by α7nAChR might play a protective role in the body. AChRs in the respiratory tract and vessels reportedly maintain homeostasis by ACh produced from nearby non-neural cells in those tissues.32,33,34 Therefore, the liver fibrosis-promoting mechanism of α7nAChR might be a protective mechanism for the liver, and nicotine excessively and abnormally activates this mechanism, leading to the exacerbation of liver fibrosis.

This study had three limitations. First, the liver fibrosis mouse model induced by NASH would have been a better option than the CCl4-induced model, which is less relevant to human diseases. Second, the expression of α7nAChR on HSCs had only been verified at the mRNA level owing to the low specificity of available antibodies for α7nAChR.35,36 In future studies, genetically engineered mice that are tagged with 3× DYKDDDDK-tag or other tags for α7nAChR could be used to verify the protein expression. Third, although we administrated nicotine into mice for 4 weeks, it is possible that longer administration could more accurately mimic human smoking and that toxicity to healthy livers, which was not seen in the 4-week nicotine administration, could occur with an 8- or 12-week administration. Thus, it is unclear whether smoking induces inflammation and fibrosis in a healthy liver.

In summary, this study provides evidence that nicotine promotes liver fibrosis via α7nAChR in activated HSCs. We hope that these findings will contribute to the holistic understanding of the mechanism underlying liver fibrosis and the negative effects of smoking on the liver.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Editage (www.editage.jp) for English language editing and Biorender (BioRender.com) for creating Supplemental Figure S6, http://links.lww.com/HC9/A931.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This work was supported by Grant-in-Aid for JSPS Fellow (18J21166), Grant-in-Aid for Research Activity Start-up (21K20613), Grant-in-Aid for Early-Career Scientists (22K15008, 24K18016), Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (19H03125, 23H02379) from The Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology, and Smoking Research Foundation (2019G013).

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts to report.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: CCl4, carbon tetrachloride; LX-2, LX-2 human hepatic steallate cell line; MLA, methyllycaconitine citrate; nAChR, nicotinic acetylcholine receptor; α7nAChR, α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor.

Supplemental Digital Content is available for this article. Direct URL citations are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s website, www.hepcommjournal.com.

Contributor Information

Taiki Mihara, Email: amihara@g.ecc.u-tokyo.ac.jp.

Masatoshi Hori, Email: horimasa@g.ecc.u-tokyo.ac.jp.

REFERENCES

- 1. Jung HS, Chang Y, Kwon MJ, Sung E, Yun KE, Cho YK, et al. Smoking and the risk of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A cohort study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019;114:453–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Michalopoulos GK, Bhushan B. Liver regeneration: Biological and pathological mechanisms and implications. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;18:40–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Michalopoulos GK. Liver regeneration. J Cell Physiol. 2007;213:286–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hernandez-Gea V, Friedman SL. Pathogenesis of liver fibrosis. Annu Rev Pathol. 2011;6:425–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Schuppan D, Afdhal NH. Liver cirrhosis. Lancet. 2008;371:838–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tan Z, Sun H, Xue T, Gan C, Liu H, Xie Y, et al. Liver fibrosis: Therapeutic targets and advances in drug therapy. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9:730176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sun M, Kisseleva T. Reversibility of liver fibrosis. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2015;39(Suppl 1 S. 60–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ou H, Fu Y, Liao W, Zheng C, Wu X. Association between smoking and liver fibrosis among patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;2019:1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pang Q, Qu K, Zhang J, Xu X, Liu S, Song S, et al. Cigarette smoking increases the risk of mortality from liver cancer: A clinical-based cohort and meta-analysis. J Evid Based Med. 2015;30:1450–1460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Whitehead AK, Erwin AP, Yue X. Nicotine and vascular dysfunction. Acta Physiologica. 2021;231:e13631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mahmoudzadeh L, Abtahi Froushani SM, Ajami M, Mahmoudzadeh M. Effect of nicotine on immune system function. Adv Pharm Bul. 2022. doi: 10.34172/apb.2023.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kondo T, Nakano Y, Adachi S, Murohara T. Effects of tobacco smoking on cardiovascular disease. Circ J. 2019;83:1980–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kyte SL, Gewirtz DA. The influence of nicotine on lung tumor growth, cancer chemotherapy, and chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2018;366:303–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Albuquerque EX, Pereira EFR, Castro NG, Alkondon M, Reinhardt S, Schröder H, et al. Nicotinic receptor function in the mammalian central nervous systema. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1995;757:48–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Albuquerque EX, Pereira EF, Alkondon M, Rogers SW. Mammalian nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: From structure to function. Physiol Rev. 2009;89:73–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wang H, Yu M, Ochani M, Amella CA, Tanovic M, Susarla S, et al. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor alpha7 subunit is an essential regulator of inflammation. Nature. 2003;421:384–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mihara T, Otsubo W, Horiguchi K, Mikawa S, Kaji N, Iino S, et al. The anti-inflammatory pathway regulated via nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in rat intestinal mesothelial cells. J Vet Med Sci. 2017;79:1795–802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hajiasgharzadeh K, Somi MH, Sadigh-Eteghad S, Mokhtarzadeh A, Shanehbandi D, Mansoori B, et al. The dual role of alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor in inflammation-associated gastrointestinal cancers. Heliyon. 2020;6:e03611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Truong LD, Trostel J, Garcia GE. Absence of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor alpha7 subunit amplifies inflammation and accelerates onset of fibrosis: an inflammatory kidney model. FASEB J. 2015;29:3558–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sun P, Li L, Zhao C, Pan M, Qian Z, Su X. Deficiency of α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor attenuates bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis in mice. Molecular Medicine. 2017;23:34–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Li M, Zheng C, Kawada T, Inagaki M, Uemura K, Akiyama T, et al. Impact of peripheral α7-nicotinic acetylcholine receptors on cardioprotective effects of donepezil in chronic heart failure rats. Cardiovascular Drugs and Therapy. 2021;35:877–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Constandinou C, Henderson N, Iredale JP. Modeling liver fibrosis in rodents. Methods Mol Med. 2005;117:237–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Matta SG, Balfour DJ, Benowitz NL, Boyd RT, Buccafusco JJ, Caggiula AR, et al. Guidelines on nicotine dose selection for in vivo research. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2007;190:269–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sakai N, Nakamura M, Lipson KE, Miyake T, Kamikawa Y, Sagara A, et al. Inhibition of CTGF ameliorates peritoneal fibrosis through suppression of fibroblast and myofibroblast accumulation and angiogenesis. Sci Rep. 2017;7:5392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mederacke I, Dapito DH, Affo S, Uchinami H, Schwabe RF. High-yield and high-purity isolation of hepatic stellate cells from normal and fibrotic mouse livers. Nat Protoc. 2015;10:305–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Higashi T, Friedman SL, Hoshida Y. Hepatic stellate cells as key target in liver fibrosis. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2017;121:27–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Shimada H, Ochi T, Imasato A, Morizane Y, Hori M, Ozaki H, et al. Gene expression profiling and functional assays of activated hepatic stellate cells suggest that myocardin has a role in activation. Liver Int. 2010;30:42–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Enc FY, Ulasoglu C, Bakir A, Yilmaz Y. The interaction between current smoking and hemoglobin on the risk of advanced fibrosis in patients with biopsy-proven nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;32:597–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wijarnpreecha K, Werlang M, Panjawatanan P, Pungpapong S, Lukens FJ, Harnois DM, et al. Smoking & risk of advanced liver fibrosis among patients with primary biliary cholangitis: A systematic review & meta-analysis. Indian J Med Res. 2021;154:806–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bioulac-Sage P, Lafon ME, Saric J, Balabaud C. Nerves and perisinusoidal cells in human liver. J Hepatol. 1990;10:105–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kalkman HO, Feuerbach D. Modulatory effects of α7 nAChRs on the immune system and its relevance for CNS disorders. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2016;73:2511–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wessler I, Kirkpatrick CJ, Racke K. Non-neuronal acetylcholine, a locally acting molecule, widely distributed in biological systems: Expression and function in humans. Pharmacol Ther. 1998;77:59–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kirkpatrick CJ, Bittinger F, Unger RE, Kriegsmann J, Kilbinger H, Wessler I. The non-neuronal cholinergic system in the endothelium: Evidence and possible pathobiological significance. Jpn J Pharmacol. 2001;85:24–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kirkpatrick CJ, Bittinger F, Nozadze K, Wessler I. Expression and function of the non-neuronal cholinergic system in endothelial cells. Life Sci. 2003;72:2111–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Moser N, Mechawar N, Jones I, Gochberg-Sarver A, Orr-Urtreger A, Plomann M, et al. Evaluating the suitability of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor antibodies for standard immunodetection procedures. J Neurochem. 2007;102:479–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rommel FR, Raghavan B, Paddenberg R, Kummer W, Tumala S, Lochnit G, et al. Suitability of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor α7 and muscarinic acetylcholine receptor 3 antibodies for immune detection. J Histochem Cytochem. 2015;63:329–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.