Abstract

F12 human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) nef is a naturally occurring nef mutant cloned from the provirus of a nonproductive, nondefective, and interfering HIV-1 variant (F12-HIV). We have already shown that cells stably transfected with a vector expressing the F12-HIV nef allele do not downregulate CD4 receptors and, more peculiarly, become resistant to the replication of wild type (wt) HIV. In order to investigate the mechanism of action of such an HIV inhibition, the F12-HIV nef gene was expressed in the context of the NL4-3 HIV-1 infectious molecular clone by replacing the wt nef gene (NL4-3/chi). Through this experimental approach we established the following. First, NL4-3/chi and nef-defective (Δnef) NL4-3 viral particles behave very similarly in terms of viral entry and HIV protein production during the first replicative cycle. Second, no viral particles were produced from cells infected with NL4-3/chi virions, whatever the multiplicity of infection used. The viral inhibition apparently occurs at level of viral assembling and/or release. Third, this block could not be relieved by in-trans expression of wt nef. Finally, NL4-3/chi reverts to a producer HIV strain when F12-HIV Nef is deprived of its myristoyl residue. Through a CD4 downregulation competition assay, we demonstrated that F12-HIV Nef protein potently inhibits the CD4 downregulation induced by wt Nef. Moreover, we observed a redistribution of CD4 receptors at the cell margin induced by F12-HIV Nef. These observations strongly suggest that F12-HIV Nef maintains the ability to interact with the intracytoplasmic tail of the CD4 receptor molecule. Remarkably, we distinguished the intracytoplasmic tails of Env gp41 and CD4 as, respectively, viral and cellular targets of the F12-HIV Nef-induced viral retention. For the first time, the inhibition of the viral life cycle by means of in-cis expression of a Nef mutant is here reported. Delineation of the F12-HIV Nef mechanism of action may offer additional approaches to interference with the propagation of HIV infection.

The in vivo role of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) Nef proteins has gained increasing consideration in the past few years, both in experimental models (e.g., HIV-infected [35, 38] or nef transgenic SCID mice [25], SIV-infected monkeys [28]) and in humans, in which the presence of HIV genomes expressing heavily mutated or even truncated forms of the nef gene was correlated with an impaired progression of the disease (16, 29, 44). Of note, it has been proposed that the pathogenicity of full-length HIV or SIV strains may be, at least in part, the consequence of the effects that Nef elicits directly on immune system (13).

On the other hand, conflicting results about the role of Nef in in vitro HIV replication have been reported (11, 24, 37, 50). There is now agreement that Nef induces the downregulation of both CD4 and major histocompatibility complex class I molecules (3, 21, 47) and dramatically improves the HIV replication efficiency in “resting” peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBLs). The stimulating effect of Nef in the HIV replication cycle acts in the producer cells at the stage of virus formation and could be appreciated in the target cells at the step of proviral DNA synthesis (2, 12, 46). Conversely, a much smaller enhancing effect on viral replication has been observed in both activated PBLs and immortalized cell lines (11, 37, 50). Furthermore, Nef interacts with several types of cellular kinases (for a review, see reference 43). The enhancement of HIV replication and the CD4 downregulation are the most accurately characterized functions of Nef.

From the provirus of a naturally occurring, nonproducer, and interfering HIV-1 variant, we have recently cloned and characterized an HIV-1 nef allele (F12-HIV nef) whose expression in stably transfected cells fails to downregulate the CD4 receptors and, more originally, induces an antiviral state (15). Interestingly, despite the dramatic phenotypic differences with respect to wild-type (wt) forms, this Nef mutant shows only three amino acid substitutions (9) never detected at the same time in any nef allele sequenced so far. Preliminary studies indicated that the block of infecting HIV induced in cells stably expressing F12-HIV Nef occurs at the stage of viral assembly and/or release (15). In view of the uniqueness of its phenotype, we decided to look more deeply at the molecular mechanism of the HIV inhibition induced by F12-HIV Nef. We analyzed the phenotype of a chimeric HIV molecular clone where the wt nef was replaced by the F12-HIV gene (NL4-3/chi). We established that in-cis expression of F12-HIV nef induces a complete block of viral replication through a mechanism acting at the step of viral assembly and/or release. Our efforts to determine both cellular and viral targets of the F12-HIV Nef inhibitory effect allowed us to obtain strong indications that the CD4–F12-HIV Nef interaction is involved in the F12-HIV Nef-induced viral retention. This was consistently observed by either transfecting or infecting cells lacking the expression of the CD4 intracytoplasmic domain. Furthermore, data obtained by cotransfecting an F12-HIV Nef expression vector together with diverse env mutant HIV molecular clones highlight the Env gp41 intracytoplasmic tail as a major viral target of the F12-HIV Nef inhibitory effect.

A model of HIV inhibition induced by in-cis expression of a mutated nef allele is described here for the first time. This seems only in part reminiscent of the negative trans dominance previously reported for other structural or regulatory HIV protein mutants (i.e., Gag, Rev, and Tat) (20, 33, 51). Furthermore, our results allow us to propose novel molecular interactions among Nef, the CD4 intracytoplasmic tail, and the HIV Env gp41 glycoprotein.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

HIV molecular clones and expressing vectors.

In order to obtain the NL4-3/chi chimeric construct, the F12-HIV nef gene was amplified by PCR from the pcDNAI/F12-HIV nef construct (15) with oligoprimers carrying the MluI (5′ end) and ClaI (3′ end) restriction sites and overlapping the nef initiation and stop codons, respectively. The amplified F12-HIV nef gene was then inserted into a derivative of the pNL4-3 plasmid (1) carrying the MluI (present in a linker inserted between the env stop and the nef start codons) and ClaI (downstream of the nef stop codon, by mutagenizing the ATC GAG sequence to ATC GAT) sites. pNL4-3 molecular clones defective in nef (Δnef) (11), env (Δenv) (48), the Env gp120 CD4 binding domain (pNL-A1[CD4−]) (54), the Env gp41 intracytoplasmic tail (HIV Tr712Env) (53), or the Nef myristoylation signal (pMD) (11) were as previously described. A Nef myristoylation-defective (Δmyr) NL4-3/chi molecular clone was obtained by reproducing the experimental strategy pursued to recover the NL4-3/chi construct, except that the oligoprimer overlapping the F12-HIV nef start codon used for the PCR amplification was designed by including nucleotide changes leading to Ala-Ala consensus in place of the two N-terminal glycines. An env-defective (Δenv) NL4-3chi molecular clone was obtained by replacing the SalI/BamHI region of the NL4-3/chi provirus with the homologous fragment from the wt Δenv HIV molecular clone (48).

wt and F12-HIV nef sequences were obtained by PCR amplifications from pNL4-3 and pUc/F12-HIV (18) molecular clones, respectively. Both primer sequences and the PCR methodology have been described (15). After appropriate digestions, nef genes were inserted into the HindIII/BamHI sites of a pcDNA3 vector (Invitrogen, San Diego, Calif.).

The pcDNA3/CD4 expressing vector was obtained by inserting the human CD4 sequence (32) into the polylinker EcoRI/EcoRV restriction sites after excision from the T4-pM7 construct (31) by EcoRI/BamHI digestions. The BamHI filling in was performed as described earlier (45).

The CD88X (5), CD884, and CD44x receptors (3), as well as the amphotropic murine leukemia virus (MLV) and HIV T-tropic (from HXB2c strain) Env proteins were expressed by a cytomegalovirus immediate-early promoter-based vector. pCNefsg25GFP (a vector expressing the NL4-3 Nef–green fluorescence protein [GFP] fusion protein) and its counterpart expressing the GFP protein alone were already described (39). F12-HIV nef–GFP-expressing vector was obtained by excising the wt nef from the former construct through SacII/NheI digestions and inserting the F12-HIV nef gene amplified by using primers carrying the SacII (5′ end) and NheI (3′ end) restriction sites overlapping the nef initiation and stop codons, respectively. All the sequences obtained by PCR amplifications were checked by the dideoxy chain termination method with the Sequenase II kit (U.S. Biochemicals, Cleveland, Ohio).

Cell cultures and transfections.

C8166 and CEMss cells were grown in RPMI 1640 (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, Md.) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS). 293 cells, HeLa cells and derivatives thereof were grown in Dulbecco modified minimal essential medium supplemented with 10% of heat-inactivated FCS.

Stably transfected cell lines were maintained in the presence of 0.5 mg of G418 antibiotic (70% activity; GIBCO Bethesda Research Laboratories, Gaithersburg, Md.) per ml, except HeLaCD4-LTR-βgal cells, which grow in G418 (0.1 mg/ml) plus hygromycin B (0.1 mg/ml) (Boehringer GmbH, Mannheim, Germany). Human PBLs from healthy donors were activated for 48 h with phytohemagglutinin (PHA), depleted of the CD8 subpopulation through immunomagnetic negative selection by using anti-CD8-coupled beads (Dynal, Oslo, Norway), and cultivated in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 20% of heat-inactivated FCS and 50 U of interleukin-2 (Roche, Nutley, N.J.) per ml.

Transfections and cotransfections were performed by the calcium phosphate method (52).

HIV infections and detection.

Supernatants from transiently transfected 293 cells were used as the source of wt, Δnef, or NL4-3/chi strains. For the infection experiments, supernatants were concentrated by ultracentrifugation as described earlier (10). Infections were performed by adsorbing the virus on cells in a small volume for 1 h at 37°C with occasional shaking. Cells were then extensively washed and refed. Virus detection in supernatants of infected cells was performed by reverse transcriptase (RT) assay (41). RT activities of supernatants were measured as counts per minute per milliliter and normalized for 106 cells after background subtraction. Viral titrations were performed either by scoring the syncytium number on C8166 cells 5 days after infection (17) or by evaluating the number of blue cells 2 days after the infection of HeLaCD4-LTR-βgal cells (7).

Protein analyses.

To determine the pattern of intracellular HIV structural proteins, Western blot assays of on infected cells were performed by the enhanced chemiluminescence method (Amersham Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom) as previously described (15) by using a strongly reactive HIV-positive human serum. Either specific polyclonal rabbit antisera or monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) (all obtained by the AIDS Research and Reference Program) were used in order to detect HIV regulatory proteins in infected or transfected cells. Detection of virionic proteins in supernatants of infected cells was performed as described earlier (6) by ultracentrifuging clarified (22-μm-pore-size filtration) supernatants at 100,000 × g, for 45 min at 4°C. Viral pellets were then loaded onto a 20% sucrose cushion, ultracentrifuged at 95,000 × g for 150 min at 4°C, and finally dissolved in a Western blot loading buffer (45).

Immunofluorescence analyses.

CD4 and CD8 membrane markers were detected by direct immunofluorescence analyses as previously described (4) by using, respectively, phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated Leu3a and Leu2a MAbs (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, Calif.).

Cells transfected with GFP fusion proteins and labeled with PE-conjugated anti-CD4 MAbs were observed, and images were analyzed by using a TCS4D confocal microscope (Leika, Heidelberg, Germany).

RESULTS

Production and titration of NL4-3/chi viral particles.

We previously demonstrated that CD4+ cells stably transfected with a vector expressing the F12-HIV nef gene maintain levels of CD4 receptors similar to those in control cells and became resistant to the HIV infection (15). To explore the mechanism of action underlying the F12-HIV nef-induced inhibition of HIV release, we constructed the pNL4-3/chi chimeric molecular clone by replacing the nef gene of the pNL4-3 molecular clone with the F12-HIV nef allele. In this manner, large amounts of F12-HIV Nef protein could be coexpressed with the remainder of the HIV protein pattern, excluding wt Nef. In most of our experiments, both wt and Nef-defective (Δnef) NL4-3 HIV infectious molecular clones or viral strains were used as controls.

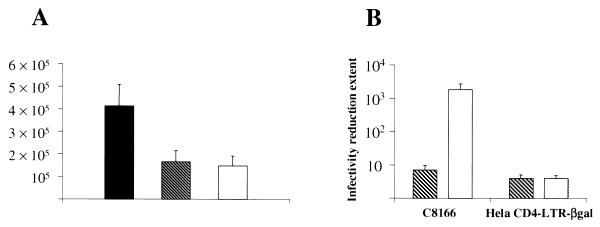

Infectious retroviral particles carrying the NL4-3/chi genome were generated by transfection of 293 cells. The ability of the pNL4-3/chi genome to code for the F12-HIV Nef protein was assessed by Western blot analysis (not shown). Results obtained by the RT assay performed on supernatants from 293 cells at 48 h posttransfection are reported in Fig. 1A. Transfection with the pNL4-3/chi molecular clone generated ca. threefold fewer viral particles than in cells transfected with wt HIV molecular clone, but these results were similar to the levels detectable in supernatants from Δnef HIV-transfected cells. In contrast, titration on C8166 cells of supernatant volumes normalized for RT activity demonstrated a sevenfold reduction and a >3-log decrease in HIV infectivity for Δnef and NL4-3/chi virions, respectively, compared to wt HIV (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 1.

Amounts (A) and infectivity (B) of HIV particles released by 293 cells transfected with pNL4-3, Δnef, or pNL4-3/chi HIV molecular clones (3 μg in semiconfluent 6-cm dishes). In panel A, RT activities in 1 ml of supernatant from each transfected cell culture are reported as the mean values ± the standard deviation (SD) from eight independent experiments. In panel B, fold reductions of infectivity (as measured by scoring either the formation of syncytia in C8166 cells infected with serial dilutions of supernatants or the relative number of blue cells after the infection of HeLaCD4-LTR-βgal cells) with respect to volumes of supernatants normalized for RT activity from pNL4-3 transfected 293 cells are reported as the average values ± the SD from four separate experiments. Viral titers of supernatants from pNL4-3 transfected cells ranged from 1 × 106 to 3.5 × 106 50% tissue culture infective doses/ml. Columns: ■, wt; ▧, Δnef; □, NL4-3/chi.

In order to assess a possible overhanging presence of noninfectious viral particles in supernatants from pNL4-3/chi-transfected cells, we repeated viral titrations on HeLaCD4-LTR-βgal cells. As shown in Fig. 1B and in contrast to the results obtained with C8166 cells, viral titers of supernatants from 293 cells transfected with either Δnef or NL4-3/chi were similar and both were reduced ca. fourfold compared to wt HIV. Thus, we can exclude the possibility that the results obtained in C8166 viral titrations depended on the generation of largely noninfectious NL4-3/chi viral populations.

From these data we deduced that (i) the expression of the F12-HIV nef gene does not positively influence the level of HIV production upon transfection, as does wt nef, and that (ii) HIV viral particles emerging from 293 cells transfected by Δnef or NL4-3/chi molecular clones show similar abilities to enter target cells (i.e., HeLaCD4-LTR-βgal). However, data from the viral titrations on C8166 cells suggest a dramatic impairment in the replicative capacity of NL4-3/chi viral particles.

No viral particles could be detected in the supernatants of CD4+ cells infected with the NL4-3/chi HIV strain.

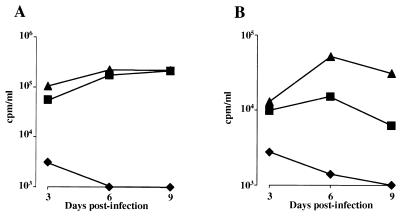

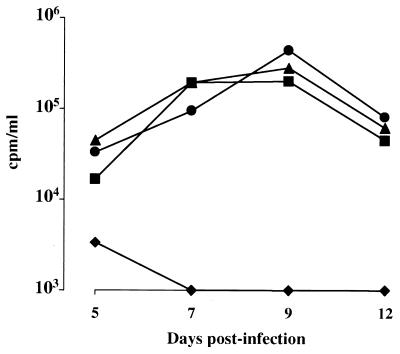

In order to better delineate the virological features of NL4-3/chi virions, infection experiments were performed by challenging either CEMss or PHA-stimulated CD8-depleted PBLs with a large dose (i.e., MOI of 0.5, as determined by titration on HeLaCD4-LTR-βgal cells) of NL4-3, Δnef, or NL4-3/chi viral particles. At 24 h after the challenge, infected cells were extensively washed and reseeded, and the supernatants were tested for RT activity at different days postinfection. The data reported in Fig. 2 clearly demonstrate that strain NL4-3/chi is unable to replicate in either CEMss cells or PHA-stimulated CD8-depleted human PBLs despite the very high MOI used. Infection experiments performed by utilizing a lower viral input produced qualitatively superimposable results (not shown).

FIG. 2.

RT activities at different days after infection with Δnef or NL4-3/chi HIV strains of either CEMss cells (A) or CD8-depleted PHA-stimulated human PBLs (B) (MOI, 0.5). Data from one representative of five (CEMss cells) or two (CD8-depleted PBLs) independent experiments are reported. Symbols: ▴, wt; ■, Δnef; ⧫, NL4-3/chi.

The lack of even aberrant viral particles in supernatants from NL4-3/chi-infected cells was assessed by Western blot analysis on supernatant ultracentrifuged through a 20% sucrose cushion (not shown). Of note, infection with strain NL4-3/chi induced a typically prompt formation of enlarged cells and syncytia (whose number depended on viral input) that were much larger and more prevalent with respect to those detectable after infection with either wt NL4-3 or Δnef viral strains (not shown). As in cells infected with wt or Δnef HIV, the infection with NL4-3/chi viral particles at a higher MOI (1 to 2) led to a rapid death of the whole cell culture (not shown). Both virological and morphologic observations were reproduced by infecting C8166, 293/CD4, and HeLaCD4 cells (not shown).

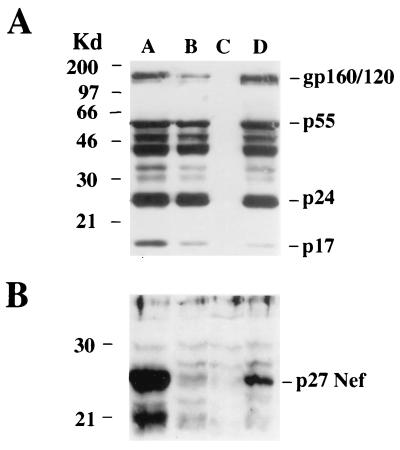

NL4-3/chi infection leads to a viral protein pattern highly reminiscent of that from Δnef NL4-3-infected cells.

As demonstrated by infecting HeLaCD4-LTR-βgal cells, both the viral entry efficiency and the ability to transactivate the β-galactosidase gene appear to be indistinguishable between the Δnef and NL4-3/chi viral strains. In order to assess whether the block of the viral release observed in NL4-3/chi-infected cells originated from a defect in structural viral protein synthesis, CEMss cells were infected (MOI, 0.5) and Western blot analyses were carried out 48 h after challenge. As shown in Fig. 3A, the intracellular HIV protein pattern appears to be essentially indistinguishable between Δnef- and NL4-3/chi-infected cells. As a control, the amounts of Nef protein on the same cell lysates were also determined (Fig. 3B). The apparent reduced levels of Nef production in NL4-3/chi with respect to wt HIV-infected cells is the likely consequence of an impaired ability of the anti-Nef polyclonal antibody used to bind the F12-HIV Nef protein. This was also observed by testing a large panel of poly- or monoclonal anti-Nef antibodies under different experimental conditions (not shown).

FIG. 3.

Western blot analyses performed with 20 μg of proteins from CEMss cells lysed 2 days after infection with either wt (lane A), Δnef (lane B), or NL4-3/chi (lane D) HIV strains (MOI, 0.5). Cell lysates from uninfected CEMss cells (lane C) were included as a negative control. Protein revelations were performed by using a strong HIV-reactive serum from an AIDS patient (A) or a polyclonal anti-Nef rabbit serum (B). HIV proteins are indicated on the right side of each panel. Molecular size markers (in kilodaltons) are given on the left side.

Finally, cells infected with strain NL4-3/chi did not show variations in the expression of the tat, rev, vif, vpr, or vpu gene with respect to either wt or Δnef HIV-infected cells (not shown).

In summary, these data indicate that the NL4-3/chi viral particles are able to enter the cells and express both regulatory and structural viral proteins at levels comparable to those of the Δnef HIV strain, but they fail to produce either infectious or noninfectious retrovirions.

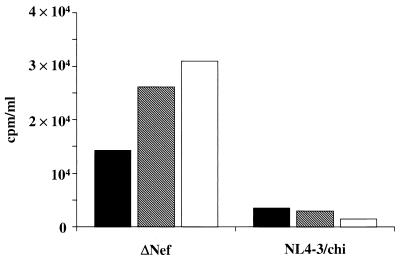

The block of viral release from cells infected by NL4-3/chi strain is not relieved by the coexpression of wt nef and is not mediated by soluble factors.

To test whether the presence of wt Nef protein could in some way relieve the F12-HIV Nef-induced inhibition of viral assembly and release, 293/CD4 cells were transfected with the pcDNA3/wt nef-expressing vector 24 h after infection (MOI, 1) with the NL4-3/chi or Δnef NL4-3 strain. After an additional 48 h, the RT activity was measured in cell supernatants. As shown in Fig. 4, whereas the expression of wt nef in Δnef NL4-3-infected cells favors, as expected, HIV production, no increase in RT activity could be conversely seen in supernatants from NL4-3/chi-infected cells. From these data we deduced that the possible positive action of wt Nef protein expression on HIV replication is not sufficient to overcome the block of viral replication imposed by the expression of F12-HIV Nef.

FIG. 4.

RT activities in supernatants of 293/CD4 cells infected with either Δnef or NL4-3/chi HIV and, after 24 h, transfected with different amounts of a pcDNA3-wt nef expressing vector. Viral input (MOI, 1) was adsorbed in 200 μl for 1 h at 37°C on 2 × 105 cells seeded in a 12-well plate. Cells were then extensively washed and refed. After 24 h, transfections with either 1 (▧) or 2 (□) μg of pcDNA3-wt nef vector were performed. After an additional 48 h, supernatants were collected and RT activities were measured. Supernatants from mock-transfected infected cultures (■) were included as a control. Data from one representative of two independent experiments are shown.

Moreover, we checked whether the release of a soluble factor(s) from NL4-3/chi-infected cells could mediate, through an autocrine loop, the inhibition of HIV release. Thus, supernatants of CEMss cells infected with a high MOI (0.5 to 1) of NL4-3/chi viral particles were collected 24, 48, and 72 h postinfection and added to CEMss cells infected 24 h in advance with different MOIs (0.1 or 0.01) of either wt or Δnef NL4-3 strains. No variations in RT activity were observed in supernatants from Δnef or wt NL4-3-infected CEMss cells treated with CEMss–NL4-3/chi-conditioned medium with respect to the infected control cultures, even after the clearance of viral particles by ultracentrifugation (data not shown). Thus, we could exclude the possibility that the block of viral release observed in CD4+ cells infected with NL4-3/chi viral strain is mediated by soluble factors.

Membrane association is essential for the F12-HIV Nef inhibitory effect.

Attempting to distinguish possible molecular targets of the F12-HIV Nef action, we first decided to monitor whether the F12-HIV Nef membrane association is important for the above-described viral retention. The N-terminal myristoylation allows Nef protein to localize in the inner side of the cytoplasmic membranes and, in particular, of the cell membrane (55). It has been demonstrated that Nef myristoylation is necessary for the interaction with CD4 at the cell membrane and, consequently, for the CD4 downregulation (27). F12-HIV Nef does not show amino acid substitutions in the Nef myristoylation signal (18) (i.e., GGXXS at the N-terminal end), and thus it presumably retains its capacity to be myristoylated and localized at the inner side of the membranes. We questioned whether the F12-HIV Nef membrane association was necessary to induce the block of the NL4-3/chi viral cycle. CEMss cells were then infected with either the parental or Δmyr forms of NL4-3/chi and, as controls, with wt or Δmyr NL4-3 HIV strains. In Fig. 5, the reversion of the NL4-3/chi to an infectious strain as the consequence of the lack of the Nef N-terminal myristoylation is clearly demonstrated. This result indicates that the myristoylation and the consequent membrane association are essential for the HIV-inhibitory effect of F12-HIV Nef protein.

FIG. 5.

RT activities of supernatants recovered on different days after infection of CEMss cells with Δmyr NL4-3 (●) or Δmyr NL4-3/chi (■) HIV (MOI, 0.5). As controls, infections with strains NL4-3 (▴) and NL4-3/chi (⧫) were replicated. Data from one representative of two independent experiments are reported.

F12-HIV Nef may interact with CD4. (i) Inhibition of the CD4 downregulation induced by wt Nef.

The data presented above strongly suggest that the block of the HIV replication cycle takes place during viral assembly and/or release. Furthermore, we showed that the membrane association of F12-HIV Nef is required for the HIV inhibitory effect. The cell membrane is the cellular compartment where a major Nef molecular target (i.e., CD4 receptor) is localized in its biologically active conformation. Moreover, it is well documented that wt Nef actively interacts with the CD4 intracytoplasmic domain (22, 23, 26, 40). We tried to establish whether F12-HIV Nef retains the ability to interact with CD4. This is conceivable, since amino acidic sequences involved in binding of the CD4 intracytoplasmic domain are well conserved in F12-HIV Nef (9). We also sought to determine, if this is true, whether F12-HIV Nef–CD4 interaction is involved in the block of HIV release.

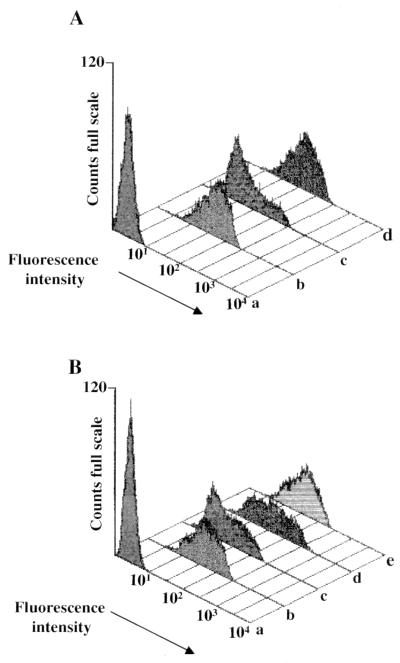

We reasoned that if F12-HIV Nef interacts with CD4, a competition with wt Nef for CD4 binding may be observed in cells coexpressing both nef alleles. Thus, we tested the possibility of the expression of F12-HIV Nef protein interfering with the wt Nef-induced CD4 downregulation, assumed to be an indicator of wt Nef-CD4 binding. Both the extent of CD4 downregulation induced by the expression of wt Nef protein and the lack of CD4 downregulation in cells transiently expressing F12-HIV Nef are shown in Fig. 6A. The transfection efficiency throughout these experiments was >80%, as assessed either by cotransfecting a GFP expressing vector or by using vector expressing Nef-GFP fusion proteins (not shown).

FIG. 6.

FACS analyses on 293/CD4 cells transfected (A) or cotransfected (B) with pcDNA3 vectors expressing either the wt or the F12-HIV nef alleles. Transfections were performed on 2 × 105 cells seeded in a 12-well plate. (A) Levels of CD4 receptors were measured by using the Leu3A anti-CD4 PE-conjugated MAb on mock-transfected 293/CD4 cells (b) and on cells transfected with 1 μg of either wt (c)- or F12-HIV nef (d)-expressing vectors. (B) CD4 levels were measured on 293/CD4 cells transfected with 1.5 μg of empty pcDNA3 vector (b), 0.5 μg of pcDNA3-wt nef plus 1 μg of empty pcDNA3 vector (c), 0.5 μg of pcDNA3-wt nef plus 0.5 μg of pcDNA3–F12-HIV nef vectors (d), or 0.5 μg of pcDNA3-wt nef plus 1 μg of pcDNA3–F12-HIV nef vectors (e). Transfected cells labeled with PE-conjugated nonspecific mouse immunoglobulin G isotype were used as a control (lane a in both panels).

293/CD4 cells were then cotransfected with the minimal amount of wt nef expressing vector able to induce an easily distinguishable CD4 downregulation, together with equal or twofold amounts of F12-HIV nef expressing vector (Fig. 6B). As controls, 293/CD4 cells were also cotransfected with wt nef and empty pcDNA3 vectors or with pcDNA3 alone. We observed that the expression of F12-HIV Nef inhibited in a dose-dependent manner the CD4 downregulation induced by wt Nef protein (Fig. 6B). This finding is in keeping with the hypothesis that F12-HIV Nef may directly or indirectly interact with the CD4 intracytoplasmic domain.

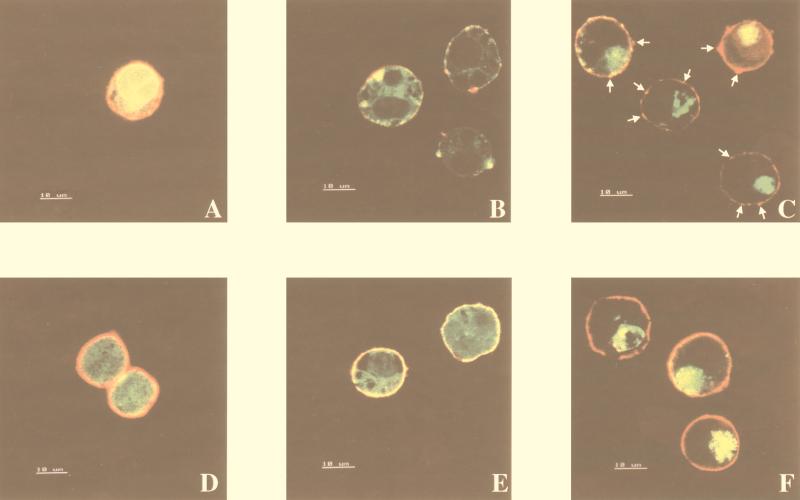

(ii) Influence on CD4 distribution at the cell membrane.

It was previously reported that the expression of wt Nef-GFP induces a CD4 redistribution from a uniform to a distinct punctate pattern at the cell margin (22). The ability of wt Nef protein to induce a CD4 clusterization was interpreted as a consequence of the interaction with the CD4 intracytoplasmic tail and considered as an intermediate step in CD4 downregulation (22). In order to highlight the ability of F12-HIV Nef to interact with CD4 more directly, we labeled 293/CD4 cells with an anti-CD4 MAb after transfection with vectors expressing F12-HIV Nef–GFP or, as a control, wt Nef/GFP or GFP alone. The analyses with a confocal microscope demonstrated that cells actively expressing F12-HIV Nef–GFP fusion protein show a clearly distinguishable punctate pattern of CD4 at the cell membrane (Fig. 7C). However, in contrast to cells expressing GFP alone (where a uniformly labeled cell margin is detectable [Fig. 7A]) and in cells expressing wt Nef-GFP protein (which show a massive lack of CD4-specific staining [Fig. 7B]), these zones of accumulation overlay a background of CD4 positivity. When the observations were carried out on 293 cells stably expressing CD4 molecules truncated in the intracytoplasmic domain (293/CD44x), a uniformly distributed CD4 pattern could be observed in all tested conditions (Fig. 7D to F). Of note, remarkable differences could be observed in the intracytoplasmic distributions between the two Nef proteins. In fact, whereas wt Nef localizes in discrete punctate aggregations, F12-HIV Nef (in conditions of similar protein expression levels [not shown]) appears to accumulate in larger amounts and in a more compartmentalized intracellular region (Fig. 7C and E).

FIG. 7.

Confocal microscopy analyses of 293/CD4 (A to C) and 293/CD44x (D and E) cells labeled with a PE-conjugated anti-CD4 MAb (see legend to Fig. 6) 48 h after transfection with vectors expressing GFP alone (A and D), wt Nef-GFP (B and E), and F12-HIV Nef–GFP fusion proteins (C and F). In panel C, the arrows indicate some of the CD4 accumulation zones. The panel C and F images were produced by using a laser power lower than that applied to obtain the remainder of the panels. This allowed a better discrimination of both F12-HIV Nef intracellular localization and membrane CD4 accumulation zones.

The evidence that the F12-HIV nef expression correlates with a redistribution of CD4 at the cell membrane supports the idea that F12-HIV Nef protein retains the ability to interact with the CD4 intracytoplasmic domain.

The F12-HIV Nef-induced block of HIV release correlates with the presence of both the CD4 intracytoplasmic tail and the HIV Env products.

We questioned whether the CD4–F12-HIV Nef interaction could be involved in the block of viral production. In addition, attempting to distinguish a viral target(s) of the F12-HIV Nef inhibitory effect, we also tried to determine whether viral Env products are involved in the F12-HIV Nef-induced viral retention. The expression of the Env products appears to be dispensable for viral release (19, 48, 49) but may play a role in the polarization of HIV budding (30). 293 cells stably expressing either CD4, CD44x, CD884 (a CD8-based chimeric receptor bearing the CD4 intracytoplasmic tail) (3), or CD88x (a CD8 receptor truncated in its intracytoplasmic domain) (5) were cotransfected with Δenv wt or Δenv NL4-3/chi HIV molecular clones together with vectors expressing either HIV or murine leukemia virus amphotropic Env proteins in a molar ratio of 1:10. All cell populations were scored in advance by fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analyses as >95% positive for the expression of either CD4 or CD8 membrane expression (not shown). As reported in Table 1, a strong impairment of HIV spread was detected in cells expressing the CD4 intracytoplasmic tail (whatever the extracellular domain) and transfected with the NL4-3/chi molecular clone expressing HIV Env in trans. These results indicate that (i) both the CD4 intracytoplasmic tail and the HIV Env products are required for the F12-HIV Nef-induced viral retention and (ii) the CD4 extracellular domain does not seem to be involved in the F12-HIV Nef-induced inhibition of HIV release.

TABLE 1.

RT activities on supernatants of 293 cells stably expressing CD4, CD44x, CD884, or CD88x receptors 48 h after the cotransfection of Δenv forms of either wt or pNL4-3/chi molecular clones with either T-tropic HIV or MLV Env-expressing vectorsa

| Cell line | RT activity of:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Δenv wt HIV cotransfected with:

|

Δenv pNL4-3/chi cotransfected with:

|

|||

| HIV Env | MLV Env | HIV Env | MLV Env | |

| 293/CD4 | 522 | 180 | 25 | 128 |

| 293/CD44x | 634 | 150 | 294 | 114 |

| 293/CD884 | 402 | 144 | 29 | 118 |

| 293/CD88x | 264 | 198 | 156 | 132 |

Values are expressed in 103 cpm/ml × 10−6 cells after background subtraction. A total of 100 ng of each Δenv HIV molecular clones was cotransfected with either HIV or MLV Env-expressing vectors in a 1:10 molar ratio on semiconfluent cultures (24-well plate) of 293 cells fully expressing either CD4, CD44x, CD884, or CD88x receptors. Values are reported from one representative of three independent experiments.

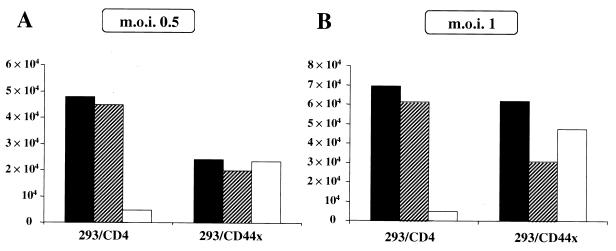

In order to enforce the hypothesis about a role of the CD4 intracytoplasmic tail in F12-HIV Nef-induced viral retention, we infected 293/CD44x cells with two different MOIs of either NL4-3/chi, Δnef, or wt NL4-3 strains. As a control, 293 cells expressing full-length CD4 were used. Figure 8 clearly shows that the lack of a CD4 intracytoplasmic tail allows the release of viral particles from cells infected with the chimeric virus. Conversely, no major differences could be observed in the RT activities measured with supernatants between the 293/CD4 and 293/CD44x cells infected with either Δnef or wt NL4-3 strains. Data from these infection experiments confirm and extend our experimental evidence concerning the major role that the CD4 intracytoplasmic tail plays in the F12-HIV Nef-induced inhibition of viral release.

FIG. 8.

RT activities in supernatants of either 293/CD4 or 293/CD44x cells 5 days after infection with two different MOIs (0.5 and 1; panels A and B, respectively) of wt (■), Δnef (▧), or NL4-3/chi (□) HIV strains. Data from one representative of three independent experiments are shown.

The HIV Env gp41 intracytoplasmic tail is required for F12-HIV Nef-induced viral inhibition.

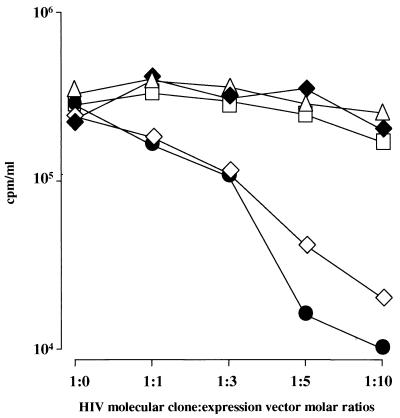

In order to define the region(s) of HIV Env products required for F12-HIV Nef-induced viral retention, we took advantage of the evidence that through transient cotransfection of an F12-HIV nef expressing vector and a pNL4-3 molecular clone, the F12-HIV Nef inhibitory effect has been fairly reproduced (15). 293/CD4 cells were cotransfected with HIV molecular clones defective for either the Env gp120 CD4 binding domain (pNL-A1 [CD4−]) (54) or the Env gp41 intracytoplasmic tail (HIV Tr712Env) (53), together with the pcDNA3–F12-HIV nef vector at different molar ratios (from 1:0 to 1:10). As controls, similar cotransfections were performed by using either the full infectious molecular clone pNL4-3 or an HIV molecular clone defective for the expression of the whole env gene (Δenv wt HIV). At 48 h after the cotransfections, supernatants were collected, and the RT levels therein were determined. The results (Fig. 9) clearly show that the F12-HIV Nef inhibitory effect does not take place in the absence of either the whole HIV Env protein or of the Env gp41 intracytoplasmic tail. Conversely, similar viral release inhibitions have been detected in supernatants of cells transfected with pNL-A1 (CD4−) or wt HIV molecular clones. These results allow us to propose the Env gp41 intracytoplasmic domain as a major viral target of the F12-HIV Nef inhibitory effect.

FIG. 9.

RT activities in supernatants of 293/CD4 cells 48 h after the cotransfection at different molar ratios (from 1:0 to 1:10) of either pNL4-3 (●), Δenv wt (▵), pNLA1 (CD4−) (◊), or Tr712 Env (⧫) HIV molecular clones (0.1 μg in a semiconfluent 24-well plate) with pcDNA3–F12-HIV nef vector. In the 1:0 points, the RT activities in the supernatants of cells transfected with each HIV molecular clone only are reported. Importantly, cotransfections with empty pcDNA3 vector did not significantly alter the RT levels in the supernatants of cells transfected with different HIV molecular clones. For example, values from supernatants of cells cotransfected with pNL4-3 and pcDNA3 plasmids (□) were included. Values from one representative of two independent experiments are reported.

DISCUSSION

The strong impairment in the replication of wt HIV induced by F12-HIV nef expression (15) is a unique feature among HIV or SIV nef alleles characterized so far. By infecting cell clones stably expressing F12-HIV nef, we previously demonstrated that the inhibitory effect acts at a very late step of the viral replication cycle, presumably during the viral assembly and/or release process (15). We also observed that cells expressing F12-HIV Nef resist infection with Δnef HIV (15; R. Bona, unpublished observations). We thus tentatively excluded the possibility that the F12-HIV Nef inhibitory effect could be the consequence of a negative trans-dominant effect, as has already been described for Tat (20) and Rev (33) mutants. In order to gain an experimental model in which an optimal coexpression of F12-HIV Nef may be achieved together with the full viral protein complement of a replication-competent HIV, but in the absence of wt Nef protein (that in most in vitro models is dispensable for HIV replication), the NL4-3/chi HIV clone was constructed. In this manner, we were able to make a closer discrimination of the effects of F12-HIV Nef on the HIV replicative cycle.

We demonstrate here that the expression of the F12-HIV nef gene is itself sufficient to transform the highly infectious NL4-3 HIV strain in a virus exclusively able to infect target cells abortively. Nef, as well as Vpr and Vpu, has been shown to be dispensable for in vitro HIV replication (11), except for the infection of resting PBLs (37, 50). Thus, the observation reported here that a slightly mutated nef gene may have such a dramatic effect on the HIV replication cycle appears to be both intriguing and original. More generally, our findings may enforce the hypothesis of a correlation between the high frequency of recovery of nef-mutated HIV genomes in long-term nonprogressor AIDS patients and the delay in disease development (16, 29, 44).

The observation that cells infected with the NL4-3/chi strain express an apparently unmodified pattern of viral proteins strongly suggests that F12-HIV Nef-induced HIV inhibition occurs at a very late replication step. This result appears to be consistent with that already observed by infecting cells stably expressing the F12-HIV nef gene (15). Furthermore, we found that the functional defect(s) of the chimeric virus could not be relieved by in-trans expression of wt nef. This finding indicates that the inhibitory effect(s) of F12-HIV Nef protein could overcome the wt Nef function(s) favoring HIV replication.

The amino acid sequences involved in Nef-induced CD4 downregulation have been mapped in both the CD4 intracytoplasmic tail and the Nef central core (23). The presence of a dileucine motif was demonstrated in both CD4 (3) and Nef (14) to be necessary for the CD4 downregulation. Through the utilization of either CD8 or CD4-Nef chimeric molecules, it has also been shown that Nef possesses an intrinsic ability to induce receptor internalization by means of a direct or indirect connection with the endocytic machinery (34). Although F12-HIV Nef fails to induce CD4 downregulation, no amino acidic substitutions have been detected in the sequences involved in the Nef-CD4 interaction (9). The possibility that F12-HIV Nef maintains the ability to interact with CD4 may be inferred from our competition assay that demonstrated the capacity of F12-HIV Nef protein to displace wt Nef from the CD4 molecule. However, we cannot formally exclude the possibility that such a result is the consequence, at least in part, of molecular events other than competition for CD4, e.g., the formation of wt–F12-HIV Nef dimers or polymers lacking the ability to bind and/or internalize CD4 receptors. An additional support for the hypothesis that F12-HIV Nef retains the ability to interact with CD4 comes from our fluorescence microscopy analyses. In fact, the coexpression of full-length CD4 and F12-HIV Nef leads to a CD4 redistribution at the cell membrane similar to that already observed for wt Nef (22). On the contrary, this phenomenon does not occur in cells expressing CD4 truncated in its intracytoplasmic domain. The lack of CD4 downregulation is likely at the basis of the much stronger CD4-specific membrane labeling in F12-HIV nef-transfected 293/CD4 cells with respect to those transfected with wt nef.

Both transfection and infection experiments done with 293/CD44x cells strongly support the hypothesis that a direct or indirect interaction between F12-HIV Nef and the intracytoplasmic tail of CD4 receptors is at the basis of the F12-HIV Nef-induced block of the viral release. This possibility is very intriguing, considering that neither nef expression (11) nor the CD4 intracytoplasmic domain (34) is necessary for completion of the HIV life cycle. In addition, from the results obtained by Western blot analyses, we may exclude defects in synthesis or processing of HIV proteins. Also noteworthy, from the transfection experiments carried out with the HIV molecular clones with either deletions or mutations in the env gene, is the suggestion that a critical role of the HIV Env gp41 intracytoplasmic domain in the F12-HIV Nef inhibitory effect may be inferred.

It has been reported that HIV Env constitutively undergoes internalization (42). This process appears to be mediated by the interaction with clathrin adapter molecules (36). The association of Env gp41 protein with Gag-derived viral core components at the cell membrane may prevent Env internalization by interfering with the binding of clathrin adapter molecules, leading to viral assembly and/or release (36). On the other hand, it was well demonstrated that Nef interacts with components of the clathrin coat at the plasma membrane, including clathrin and β subunits of adapter protein complex-2 (a component of the endocytotic machinery) (22, 27). We may hypothesize that CD4–F12-HIV Nef binding induces the recruitment of molecules from the endocytic machinery, as already shown for wt Nef. In this regard, it should be noted that F12-HIV Nef retains the dileucine motif (9) needed to address the cellular sorting machinery (14). However, the lack of CD4 downregulation may alter the physiological recycling of clathrin-adaptin molecules which thus may bridge the CD4–F12-HIV Nef complex with the Env gp41 intracytoplasmic tail. This could lead to an abnormal accumulation and/or an altered spatial distribution of clathrin molecules that may hinder their displacement from Env gp41 by HIV Gag proteins, thus inhibiting correct viral assembly and/or release. We consistently observed that the lack of either CD4 or Env gp41 intracytoplasmic domains renders ineffective the antiviral action of F12-HIV Nef. Our finding that removal of the F12-HIV Nef myristoyl group correlates with the reversion of NL4-3/chi to an infectious strain fulfills the hypothesis that crucial events leading to the viral block occur in the neighborhood of intracellular membranes or, more likely, of the inner side of the cell membrane. At the moment, a detailed description of both the molecular basis of the F12-HIV Nef, CD4, and Env interactions and their effects on correct HIV morphogenesis represents an attractive experimental challenge.

In summary, our data delineate a model of inhibition of HIV replication that has, to the best of our knowledge, no counterpart in the HIV field. HIV genomes that in vivo express nef alleles with a similar phenotype may have a role in the containment of HIV spread in that they show a reduced replication capacity and also could behave as interfering HIV genomes, as demonstrated for the whole F12-HIV genome (18). The findings we obtained while attempting to elucidate the mechanism of action of F12-HIV Nef-induced HIV inhibition are also encouraging from the perspective of anti-HIV gene therapy strategy. It is worth noting that the F12-HIV Nef inhibitory effect acts through the major component needed for viral entry, thus guaranteeing the block of viral spread from the cells attacked by HIV infection.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

HeLaCD4-LTR-βgal cells, pNL4-3, and Δenv HIV (pMenv−) molecular clones and mono- or polyclonal antibodies recognizing regulatory HIV proteins were obtained from the AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH. We are grateful to J. Guatelli, University of California, San Diego, for kindly providing both the Nef-deficient (pDs) and the Δmyr Nef (pMd) HIV molecular clones; to V. Bosch, Deutsches Krebsforschungszentrum, Heidelberg, Germany, for both Env mutated HIV molecular clones; and to S. Pulciani, from our laboratory, and to E. Vicenzi, DIBIT Institute, Milan, Italy, who provided murine leukemia virus- and HIV Env-expressing vectors, respectively. This study was definitively supported by C. Aiken, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, Tenn., who generously provided both CMX/CD44x and CMX/CD884 expression vectors. We are indebted to A. Baur, Institut für Klinische und Molekulare Virologie, Universität Erlangen, Erlangen, Germany, for the generous gift of both the CD88x expressing vector and the pNL4-3 MluI/ClaI molecular clone and for critical reading of the manuscript. We also acknowledge A. Lippa and F. M. Regini for excellent editorial assistance.

This work was supported by grants from the AIDS Project of the Ministry of Health, Rome, Italy.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adachi A, Gendelman H E, Koenig S, Folks T, Willey R, Rabson A, Martin M A. Production of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome associated retrovirus in human and nonhuman cells transfected with an infectious molecular clone. J Virol. 1986;59:284–291. doi: 10.1128/jvi.59.2.284-291.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aiken C, Trono D. Nef stimulates human immunodeficiency virus type 1 proviral DNA synthesis. J Virol. 1995;69:5048–5056. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.8.5048-5056.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aiken C, Konner J, Landau N R, Lenburg M E, Trono D. Nef induces CD4 endocytosis: requirement for a critical dileucine motif in the membrane-proximal CD4 cytoplasmic domain. Cell. 1994;75:853–864. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90360-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baiocchi M, Olivetta E, Chelucci C, Santarcangelo A C, Bona R, D'Aloja P, Testa U, Komatsu N, Verani P, Federico M. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-1 resistant CD4+ UT-7 megakaryocytic human cell line becomes highly HIV-1 and HIV-2 susceptible upon CXCR4 transfection: induction of cell differentiation by HIV-1 infection. Blood. 1997;89:2670–2678. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baur A S, Sass G, Laffart B, Willbold D, Cheng-Mayer C, Peterlin B M. The N-terminus of Nef from HIV-1/SIV associates with a protein complex containing Lck and a serine kinase. Immunity. 1997;6:283–291. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80331-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bona R, D'Aloja P, Olivetta E, Modesti A, Modica A, Ferrari G, Verani P, Federico M. Aberrant, noninfectious HIV-1 particles are released by chronically infected human T-cells transduced with a retroviral vector expressing an interfering HIV-variant. Gene Ther. 1997;4:1085–1092. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bryant M L, Ratner L, Duronio R J, Kishore N S, Devadas B, Adams S P, Grodon J I. Incorporation of 12-methoxydodecanoate into the human immunodeficiency virus Gag polyprotein precursor inhibits its proteolytic processing and virus production in a chronically infected human lymphoid cell line. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:2055–2059. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.6.2055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carlini F, Nicolini A, D'Aloja P, Federico M, Verani P. The non-producer phenotype of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 provirus F12/HIV-1 is the result of multiple genetic variations. J Gen Virol. 1996;77:2009–2013. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-77-9-2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carlini F, Federico M, Equestre M, Ricci S, Ratti G, Zibai Q, Verani P, Rossi G B. Sequence analysis of an HIV-1 proviral DNA from a non producer chronically infected Hut-78 cellular clone. J Virol Dis. 1992;1:40–55. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chelucci C, Hassan H J, Locardi C, Bulgarini D, Pelosi E, Mariani G, Testa U, Federico M, Valtieri M, Peschle C. In vitro human immunodeficiency virus-1 infection of purified progenitors in single-cell culture. Blood. 1995;85:1181–1187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chowers M Y, Spina C A, Kwoh T J, Fitch N J S, Richman D D, Guatelli J C. Optimal infectivity in vitro of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 requires an intact nef gene. J Virol. 1994;68:2906–2914. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.5.2906-2914.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chowers M Y, Pandori M W, Spina C A, Richman D D, Guatelli J C. The growth advantage conferred by HIV-1 Nef is determined at the level of viral DNA formation and is independent of CD4 downregulation. Virology. 1995;212:451–457. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Collins K L, Chens B K, Kalama A, Walker B D, Baltimore D. HIV-1 Nef protein protects infected primary cells against killing by cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Nature. 1998;391:397–401. doi: 10.1038/34929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Craig H M, Pandori M W, Guatelli J C. Interaction of HIV-1 Nef with the cellular dileucine-based sorting pathway is required for CD4 down-regulation and optimal viral infectivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:11229–11234. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.19.11229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.D'Aloja P, Olivetta E, Bona R, Nappi F, Pedacchia D, Pugliese K, Ferrari G, Verani P, Federico M. gag, vif, and nef genes contribute to the homologous viral interference induced by a nonproducer human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) variant: identification of novel HIV-1-inhibiting viral protein mutants. J Virol. 1998;72:4308–4319. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.5.4308-4319.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deacon N J, Tsykin A, Solomon A, Smith K, Ludford-Menting M, Hooker D J, McPhee D A, Greenway A L, Ellet A, Chatfield C. Genomic structure of an attenuated quasi species of HIV-1 from a blood transfusion donor and recipients. Science. 1995;270:988–991. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5238.988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Federico M, Taddeo B, Carlini F, Nappi F, Verani P, Rossi G B. A recombinant retrovirus carrying a nonproducer human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) type 1 variant induces resistance to superinfecting HIV. J Gen Virol. 1993;74:2099–2110. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-74-10-2099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Federico M, Nappi F, Bona R, D'Aloja P, Verani P, Rossi G B. Full expression of transfected nonproducer interfering HIV-1 proviral DNA abrogates susceptibility of human HeLaCD4+ cells to HIV. Virology. 1995;206:76–84. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6822(95)80021-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gheysen D, Jacobs E, de Foresta F, Thiriart C, Francotte M, Thines D, de Wilde M. Assembly and release of HIV-1 precursor pr55Gag virus-like particles from recombinant baculovirus-infected insect cells. Cell. 1989;59:103–112. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90873-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Green M, Ishino M, Loewenstein P M. Mutational analysis of HIV-1 Tat minimal domain peptides: identification of trans-dominant mutants that suppress HIV-LTR-driven gene expression. Cell. 1989;58:215–223. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90417-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Greenberg M E, Iafrate A J, Skowronski J. The SH3 domain-binding surface and an acidic motif in HIV-1 Nef regulate trafficking of class I MHC complexes. EMBO J. 1998;17:2777–2789. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.10.2777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Greenberg M E, Bronson S, Lock M, Neumann M, Pavlakis G N, Skowronski J. Co-localization of HIV-1 Nef with the AP-2 adaptor protein complex correlates with Nef-induced CD4 down-regulation. EMBO J. 1997;16:6964–6976. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.23.6964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grzesiek S, Stahl S J, Wingfield P T, Bax A. The CD4 determinant for downregulation by HIV-1 Nef directly binds to Nef. Mapping of the Nef binding surface by NMR. Biochemistry. 1996;35:10256–10261. doi: 10.1021/bi9611164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guy B, Kieny M P, Riviere Y, Le Peuch C, Dott K, Girard M, Montagnier L, Lecocq J P. HIV F/3′ orf encodes a phosphorylated GTP-binding protein resembling an oncogene product. Nature. 1987;330:266–269. doi: 10.1038/330266a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hanna Z, Denis G K, Rebai N, Guimond N, Jothy N, Jolicoeur N. Nef harbors a major determinant of pathogenicity for AIDS-like disease induced by HIV-1 in transgenic mice. Cell. 1998;95:163–175. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81748-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harris M P, Neil J C. Myristoylation dependent binding of HIV-1 Nef to CD4. J Mol Biol. 1994;241:136–142. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Iafrate A J, Bronson S, Skowronski J. Separable functions of Nef disrupt two aspects of T cell receptor machinery: CD4 expression and CD3 signaling. EMBO J. 1997;16:673–684. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.4.673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kestler H W, Ringler D J, Mori D J, Panicali D L, Sehgal D L, Daniel M D, Desrosiers M D. Importance of the nef gene for the maintenance of high virus loads and for development of AIDS. Cell. 1991;65:651–662. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90097-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kirchoff F, Greenough T C, Brettler D B, Sullivan J L, Desrosiers R C. Absence of intact nef sequence in a long-term survivor with nonprogressive HIV-1 infection. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:228–232. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199501263320405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lodge R, Gottlinger H, Gabudza D, Cohen E, Lemay G. The intracytoplasmic domain of gp41 mediated polarized budding of human immunodeficiency virus type I in MDCK cells. J Virol. 1994;68:4857–4861. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.8.4857-4861.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maddon P J, Dalgleish A G, McDougal J S, Clapham P R, Weiss R A, Axel R. The T4 gene encodes the AIDS virus receptor and is expressed in the immune system and the brain. Cell. 1986;47:333–348. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90590-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maddon P J, Littman D R, Godfrey M, Maddon D E, Chess L, Axel R. The isolation and nucleotide sequence of a cDNA encoding the T cell surface protein T4: a new member of the immunoglobulin supergene family. Cell. 1985;42:93–104. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(85)80105-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Malim M H, Freimuth W W, Liu J, Boyle T J, Lyerly H K, Cullen B R, Nabel G J. Stable expression of transdominant Rev protein in human T cell inhibits human immunodeficiency virus replication. J Exp Med. 1992;176:1197–1201. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.4.1197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mangasarian A, Foti M, Aiken C, Chin D, Carpentier J L, Trono D. The HIV-1 Nef protein acts as a connector with sorting pathways in the Golgi and at the plasma membrane. Immunity. 1997;6:67–77. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80243-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Markham R B, Schwartz S A, Templeton S A, Margolick S A, Farzadegan S A, Vlahov D, Yu X F. Selective transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 variants to SCID mice reconstituted with human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. J Virol. 1996;70:6947–6954. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.10.6947-6954.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marsh M, Pelchen-Matthews A, Hoxie J A. Roles for endocytosis in lentiviral replication. Trends Cell Biol. 1997;7:1–4. doi: 10.1016/S0962-8924(97)20038-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miller M, Warmerdam M T, Gaston I, Greene W C, Feinberg M B. The human immunodeficiency virus-1 nef gene product: a positive factor for viral infection and replication in primary lymphocytes and macrophages. J Exp Med. 1994;179:101–113. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.1.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mosier D E, Gulizia R J, Baird S M, Wilson D B, Spector D B, Spector S A. Human immunodeficiency virus infection of human-PBL-SCID mice. Science. 1991;251:791–794. doi: 10.1126/science.1990441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Palm G J, Zolanov A, Gaitanaris G A, Strauber R, Pavlakis G N, Wloulawer A. The structural basis for spectral variation in green fluorescent protein. Nat Struct Biol. 1997;4:361–365. doi: 10.1038/nsb0597-361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rossi F, Gallina A, Milanesi G. Nef-CD4 physical interaction sensed with the yeast two-hybrid system. Virology. 1996;217:397–403. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rossi G B, Verani P, Macchi B, Federico M, Orecchia A, Nicoletti L, Buttò S, Lazzarin A, Mariani G, Ippolito G, Manzari V. Recovery of HIV-related retroviruses from Italian patients with AIDS or AIDS-related complex and from asymptomatic at-risk individuals. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1987;511:390–400. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1987.tb36268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rowell J F, Ruff A L, Guarnieri F G, Staveley-O'Carrol K, Lin X, Tang J, August J T, Siliciano R F. Lysosome-associated membrane protein-mediated targeting of the HIV-1 envelope protein to an endosomal/lysosomal compartment enhances its presentation to MHC class II-restricted cells. J Immunol. 1995;155:1818–1828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saksela K. HIV-1 Nef and host cell protein kinases. BioScience. 1997;2:606–618. doi: 10.2741/a217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Salvi R, Garbuglia A R, Di Caro A, Pulciani S, Montella F, Benedetto A. Grossly defective nef gene sequences in a human immunodeficiency virus type 1-seropositive long-term nonprogressor. J Virol. 1998;72:3646–3657. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.5.3646-3657.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schwartz O, Maréchal V, Danos O, Heard J M. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Nef increases the efficiency of reverse transcription in the infected cell. J Virol. 1995;69:4053–4059. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.7.4053-4059.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schwartz O, Maréchal V, Le Gall S, Lemonnier F, Heard J M. Endocytosis of major histocompatibility complex class I molecules is induced by the HIV-1 Nef protein. Nat Med. 1996;2:338–342. doi: 10.1038/nm0396-338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sedaie M R, Kalyanaraman V S, Mukopadhayaya R, Tschachler E, Gallo R C, Wong-Staal F. Biological characterization of noninfectious HIV-1 particles lacking the envelope protein. Virology. 1992;187:604–611. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90462-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Smith A J, Cho M I, Hammarskjold M L, Rekosh D. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Pr55gag and Pr160gag-pol expressed from a simian virus 40 late replacement vector are efficiently processed and assembled into virus like particles. J Virol. 1990;64:2743–2750. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.6.2743-2750.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Spina C A, Kwoh T J, Chowers M Y, Guatelli J C, Richman D D. The importance of Nef in the induction of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication from primary quiescent CD4 lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1994;179:115–123. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.1.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Trono D, Feinberg M B, Baltimore D. HIV-1 Gag mutants can dominantly interfere with the replication of the wild-type virus. Cell. 1989;59:113–120. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90874-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wigler M, Sweet R, Sim G K, Wold B, Pellicer A, Lacy E, Maniatis T, Silverstein S, Awel R. Transformation of mammalian cells with genes from procaryotes and eucaryotes. Cell. 1979;16:758–777. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(79)90093-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wilk T, Pfeiffer T, Bosch V. Retained in vitro infectivity and cytopathogenicity of HIV-1 despite truncation of the C-terminal tail of the env gene product. Virology. 1992;189:167–177. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90692-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Willey R L, Maldarelli F, Martin M A, Strebel K. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vpu protein induces rapid degradation of CD4. J Virol. 1992;66:7193–7200. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.12.7193-7200.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zazopoulos E, Haseltine W A. Mutational analysis of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Eli Nef function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:6634–6638. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.14.6634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]