INTRODUCTION

The scene is a crowded Emergency Department (ED) triage corridor lined up with patients walking in or delivered by a queue of ambulances. Overcrowding in Emergency Departments has reached historic levels. Overcrowding has often been attributed to system-level barriers to ED input, throughput, and output.1 Within this framework, ED boarding is a critical contributor to overcrowding.2 ED boarding is defined as the time an individual remains physically located in the ED following the admission decision and bed request.2 Even though ED boarding has been associated with increased mortality, medical errors, care delays, discharge against medical advice, cost of care, and decreased patient satisfaction, ED options to mitigate boarding are limited.1,3 In response to the overcrowding crisis and increased ED boarding, the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) released a policy statement in 2017 highlighting that optimal care is provided on the wards once a patient is admitted. As such, boarding “represents a failure of inpatient bed management.”4 ACEP made several recommendations highlighting that the hospital must be responsible for timely transitions out of the ED with adequate nursing staff, contingency plans, and efforts to improve patient placement. Emergency medicine’s ongoing attempts to optimize strategies require a response from policymakers, healthcare payors, health system management, and community organizations, and reorganizing how patients are prioritized for inpatient care.

In the years since this statement, the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated the increased boarding times compared to pre-pandemic levels.3 Increased inpatient occupancy leading to ED gridlock, financial challenges leading to preferential admission of surgical patients, and nursing shortages are highlighted as some of the causes.3 To underscore the dire situation EDs in the United States are currently facing, on November 7th, 2022, ACEP sent a letter to The White House outlining ED overcrowding as a public health emergency.5 The letter included evidence of the harm from ED boarding, ranging from hours to days and weeks. Several testimonials from ED physicians describe preventable harm, even within pediatric populations, lack of adequate outpatient psychiatric care, provider and staff burnout, and nursing shortages. ACEP called on The White House to convene a stakeholder summit to address this urgent crisis. This letter was signed by multiple specialty societies from across the United States.

Although this recent call to action is supported, it fails to highlight how this crisis has disproportionately impacted the vulnerable and growing older adult population in the United States.

WHY IT MATTERS

Older adults use the ED at higher rates than other adult age groups. In 2018, adults over the age of 65 had 45 visits per 100 persons, accounting for 18% of all ED visits, and hospital admissions (40%) are disproportionately represented by older adults ≥ 65.6 We also know older adults experience increased complications from ED boarding. One study showed that increased boarding time is associated with increased mortality, length of stay, and ICU admission; concurrently, half of all individuals boarding longer than 24 hours were more than age 65 years.6 The same article noted that persons with higher boarding times were more frequently from minoritized racial/ethnic groups, had comorbidities, and had higher illness severity. Older adults and those with more comorbidities also have a greater frequency of complications from ED boarding, such as treatment and medication errors.7 Additionally, longer ED boarding is associated with increased delirium in older adults, morbidity, mortality, nursing home placement, and healthcare costs.7

These outcomes are forecast to increase without rapid policy interventions to mitigate ED boarding amongst older adults. In the next ten years, the older adult demographic of the US population is expected to increase, with older adults accounting for the largest proportion of the population for the first time in United States history.7

In response to this reality, we suggest several recommendations for addressing the complexities of the ED boarding epidemic for older adults. Many of these suggestions are implicit in the Geriatric Emergency Department (GED) program accreditation guidelines by ACEP.8 GED programs enhance the ability of the ED and health systems to address the specific needs of older adults. Yet, GED programs alone cannot address the scope of engagement needed to address prolonged ED boarding times.

RECOMMENDATIONS

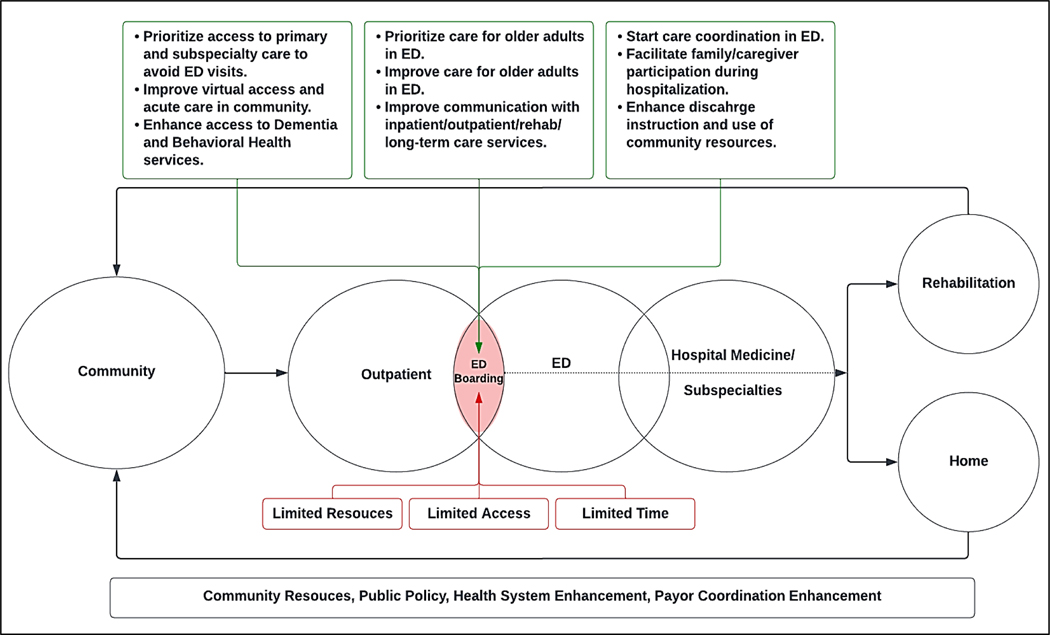

Healthcare systems of all capacities are aware of prolonged boarding time. With the dynamic nature of the problem, it is challenging to predict solutions. In the short term, there is unlikely to be a rapid increase in the number of EDs per capita or recovery of adequate healthcare staffing to mitigate the challenges of ED boarding for older adults. However, GED or Age-Friendly Initiatives may help coordinate transdisciplinary efforts to improve emergency geriatric care, enhance efficiency, and decrease preventable harms. We suggest the following age-friendly starting points to mitigate the adverse impact of prolonged boarding on older adults: (Figure 1.)

Figure 1: Framework for Boarded Older Adults in Overcrowded Emergency Departments: Driving (+) and Mitigating (−).

Health System Preparedness

Track and report boarding time.

Track and report adverse events. Examples include older adults leaving against medical advice, left without being evaluated, delirium incidence, falls in ED, use of antipsychotics, and provider (Nursing, Physicians, APPs) satisfaction/stress. Other traditional quality indicators for the care of older adults, such as hospital length of stay, pressure ulcers, mortality, and disposition metrics, can be connected to boarding metrics to make a case for resources.

Enhance administration staffing to register older adults quickly to reduce the time to initiation of emergency care.

Create teams to address social determinants of health. Robust outpatient, inpatient, and ED social work and case management teams should work in tandem to address social causes of admission or barriers to discharge for older adults. This requires systematic identification of targetable social determinants of health (e.g., medication access, transportation need, food safety, primary care access, and, when present, rapid referral to such services, allowing ED staff to address acute medical needs.

Create new support pathways for patients with Dementia and cognitive impairment, including resources for care and relationships with behavioral care units, assisted by local Geriatric and/or Specialty Memory Outpatient Centers, to mitigate the diagnostic difficulties and behavioral challenges that complicate care for vulnerable older adults with dementia.

Improve primary care and virtual care access for older adults.

Engage transdisciplinary teams including medicine and surgery services to 1) overcome barriers to discharge reducing hospital length of stay and 2) create new scheduling protocols that smooth inpatient bed utilization for elective surgical cases. This will enable more rapid ED admissions of older adults while preserving the ability to admit elective surgery cases which we recognize is often a priority given the financial burdens of hospitals nationwide.3

Enhance Interprofessional communication and cooperation with internal stakeholders such as Emergency Medicine, Hospital Medicine, Geriatric Medicine, Nursing, Case Management, Social Work, and Physical Therapy to continuously evaluate and strategize effective care transitions and permit optimal multimodal complex care for older adults.

Enhance Interprofessional communication and cooperation with external stakeholders, including local area Skilled and Long-Term Care facilities and community organizations.

Prioritize Care for Older Adults

Develop new communications tools to increase health system stakeholder awareness of boarding times and adverse events.

Develop instruments that consider age and other co-morbidity risks of boarding rather than informal rounding and provide documentation to support decision-making. Patient placement workflows seem both subjective and lack utilization of algorithmic or assessment scoring tools for patient priority regarding an ED to inpatient bed.

Improve systematic identification of high-risk older adults to enable efficient utilization of enhanced geriatric services such as: social work/case management, medication reconciliation, delirium prevention, focused goals of care discussions, early mobility programs, and prioritized admission.9

Engage health system and inpatient teams to prioritize transitioning older adults out of the ED to inpatient care, decreasing diagnostic delay and resulting in poor outcomes.10

Transitions of Care

Enhance discharge education protocols focused on educating the older adult and their caregivers about the diagnosis, follow-up plan, and medication changes. Discuss potential new functional needs of the older adult and identify resources to increase the likelihood of discharge success.11,12

Create enhanced information sharing and task management protocols with community primary care services and explore partnerships with Medicare/Medicaid managed care organizations to optimize transitions.

Improve ED relationships with community agencies and services and ensure accurate ED discharge communication. ED communication focusing on accurate medication reconciliation, scheduling needed follow-up appointments before discharge, social barriers, and expectations from the SNFs and other agencies for the older adult and their caregiver can avoid preventable readmissions, particularly for older adults with new functional impairments and fall risk.13

Continue evaluation and adoption of the waiver for the three-day acute stay policy, implemented during COVID relief, to enable discharge of older adults with skilled needs but no acute medical conditions to subacute inpatient rehabilitation (SCIR) or skilled nursing facilities (SNF) and increase acute inpatient bed capacity. The sunset of the federal COVID waiver to bypass the 72-hour acute admission requirement prior to transitions to skilled nursing facilities has limited an ED provider’s ability to avoid admission and instead transfer patients who may not require acute inpatient care. We recommend improved accountable care organization (ACO) contracting to demand the adoption of the waiver for the three-day acute stay policy implemented during COVID relief.

Adopt alternative discharge dispositions from emergency care which could include referral to same-day outpatient care, transition to observation units, hospital-at-home programs, and virtual emergency services.13

Add Caregiver support, services, and referrals to address stress, strain, and care coordination.14

Community Engagement

Create Partnerships with community organizations (local and national) such as Area Agencies on Aging (AAA), the Alzheimer’s Association, and community paramedicine15 to leverage their expertise in determining ways to proactively prevent ED visits, particularly for vulnerable older adults with social isolation, cognitive and mobility impairment, and socioeconomic barriers in the community.

National Engagement

Promote a national dialogue between key expert stakeholders such as, but not limited to, the American Geriatric Society (AGS), American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP), Society of Academic Emergency Medicine (SAEM), Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM), American College of Physicians (ACP), American Academy of Home Care Medicine (AAHCM), Society for General Internal Medicine (SGIM), Society for Post-Acute and Long-Term Care Medicine, Gerontological Advanced Practice Nurses Association (GAPNA), payors, health system executives, and policymakers to assess the burden of overcrowding on the care for older adults and determine support mechanisms and policy changes that can begin to address this health system burden.

CONCLUSION

We understand that the factors contributing to the boarding crisis are multifaceted, and proposed solutions are multi/transdisciplinary and will need Innovation, Interactions, and Investment (3I). As programs aim to develop initiatives pragmatically with the above recommendations, we suggest learning from and modifying existing, successful, and high value programs from other disciplines. For instance, the recently proposed Guiding an Improved Dementia Experience (GUIDE) Model16 by CMS, though geared towards creating a medical home for patients with dementia, can help in part model the creation of multi/transdisciplinary efforts to address the overcrowding of older adults in the ED. There has also been great success in improving outcomes with modified Hospital Elder Life Programs (HELP)17 and Geriatric Surgical Verification (GSV) programs.18 In addition, the Nurses Improving Care for Health System Elders (NICHE) program19 has had great success in training nurses to be geriatric resource nurses within successful programs. More such 3I initiatives are needed. With the above recommendations we can begin to address this critical epidemic by leveraging transdisciplinary expertise, local and national partners, and policymakers. We urge local and national leaders to address the boarding crises of older adults and how to mitigate its impact, consolidate strengths, and offer further guidance.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

American Geriatric Society Geriatric Emergency Debarment Special Interest Group (AGS GER-ED SIG)

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Sponsor Role:

There were no sponsors of this work.

Funding:

There was no funding for this work.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts to report.

Contributor Information

April Ehrlich, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

Mitchel Erickson, University of California, San Francisco.

Esther S Oh, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

Todd James, University of California, San Francisco.

Saket Saxena, Cleveland Clinic.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kenny JF, Chang BC, Hemmert KC. Factors Affecting Emergency Department Crowding. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2020;38(3):573–587. doi: 10.1016/j.emc.2020.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boudi Z, Lauque D, Alsabri M, et al. Association between boarding in the emergency department and in-hospital mortality: A systematic review. PLoS One. 2020;15(4):e0231253. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0231253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kelen GD, Wolfe R, D’onofrio G, et al. Emergency Department Crowding: The Canary in the Health Care System. NEJM Catal. Published online 2021. doi: 10.1056/CAT.21.0217 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.ACEP // Boarding of Admitted and Intensive Care Patients in the Emergency Department. Accessed February 10, 2023. https://www.acep.org/patient-care/policy-statements/boarding-of-admitted-and-intensive-care-patients-in-the-emergency-department/

- 5.Update on the ED Boarding Crisis: ACEP and 34 Other Organizations Send Letter to President Biden Calling for a Summit | ACEP. Accessed July 12, 2023. https://www.acep.org/federal-advocacy/federal-advocacy-overview/regs--eggs/regs--eggs-articles/regs--eggs---november-10-2022

- 6.Center for Health Statistics N. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2018 Emergency Department Summary Tables. Published online 2018. Accessed August 7, 2023. https://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/Health_

- 7.Liu SW, Thomas SH, Gordon JA, Hamedani AG, Weissman JS. THE PRACTICE OF EMERGENCY MEDICINE/BRIEF RESEARCH REPORT A Pilot Study Examining Undesirable Events Among Emergency Department-Boarded Patients Awaiting Inpatient Beds. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;54:381–385. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2009.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.American College of Emergency Physicians. ACEP geriatric emergency department accreditation. Accessed December 12, 2021. https://www.acep.org/geda/

- 9.Saxena S, Meldon S, Hashmi AZ, Muir M, Ruwe J. Use of the electronic medical record to screen for high-risk geriatric patients in the emergency department. JAMIA Open. 2023;6(2). doi: 10.1093/JAMIAOPEN/OOAD021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moura Junior V, Westover MB, Li F, et al. Hospital complications among older adults: Better processes could reduce the risk of delirium. Heal Serv Manag Res. 2022;35(3):154. doi: 10.1177/09514848211028707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gettel CJ, Serina PT, Uzamere IB, et al. Emergency department-to-community care transition barriers: A qualitative study of older adults. Published online 2022. doi: 10.1111/jgs.17950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liebzeit D, Rutkowski R, Arbaje AI, Fields B, Werner NE. A Scoping Review of Interventions for Older Adults Transitioning from Hospital to Home. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69(10):2950. doi: 10.1111/JGS.17323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tian Y, Ayyappan V, Hemmert K, Myers J, Gitelman Y, Ryskina K. Potentially avoidable emergency department use by patients discharged to skilled nursing facilities. J Hosp Med. 2023;18(6):524–527. doi: 10.1002/JHM.13111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang SS. Depression among caregivers of patients with dementia: Associative factors and management approaches. http://www.wjgnet.com/. 2022;12(1):59–76. doi: 10.5498/WJP.V12.I1.59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Myers LA, Carlson PN, Krantz PW. UC Irvine Western Journal of Emergency Medicine: Integrating Emergency Care with Population Health Title Development and Implementation of a Community Paramedicine Program in Rural United States Publication Date. West J Emerg Med Integr Emerg Care with Popul Heal. 21(5). doi: 10.5811/westjem.2020.7.44571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guiding an Improved Dementia Experience (GUIDE) Model | CMS Innovation Center. Accessed August 18, 2023. https://innovation.cms.gov/innovation-models/guide

- 17.XTammy Hshieh XT, Xmd X, XTinghan Yang X, et al. Hospital Elder Life Program: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Effectiveness. Published online 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2018.06.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Geriatric Surgery Verification | ACS. Accessed August 29, 2023. https://www.facs.org/quality-programs/accreditation-and-verification/geriatric-surgery-verification/

- 19.Squires A, Patel Murali K, Greenberg SA, Herrmann LL, D CO. A Scoping Review of the Evidence About the Nurses Improving Care for Healthsystem Elders (NICHE) Program. Gerontol cite as Gerontol. 2021;61(3):75–84. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnz150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]