MicroRNA-21 (miR-21) plays a significant role in the regulation of fibrotic and inflammatory gene expression signatures. Endogenous miR-21 shows robust expression in different types of cardiac cells, particularly in cardiac non-myocytes, and its expression is further increased in various cardiac and/or fibrotic diseases. Accumulating evidence indicates that inhibiting miR-21 can reverse myocardial fibrosis.1,2 Previous studies investigating the effects of miR-21 inhibition on cardiac function and pathology have frequently relied on cell cultures or animal models. However, the direct effect of inhibiting miR-21 in failing human hearts remained unexplored. In this study, we employed an ex vivo model of living myocardial slices (LMS) to investigate the direct effects of miR-21 inhibition on failing human myocardium. LMS are ultra-thin (∼300 µm) sections generated from left ventricular specimens obtained from explanted hearts during transplantation surgery. The thin nature of LMS allows free diffusion of oxygen and nutrients, enabling their survival in culture and contracting conditions.3

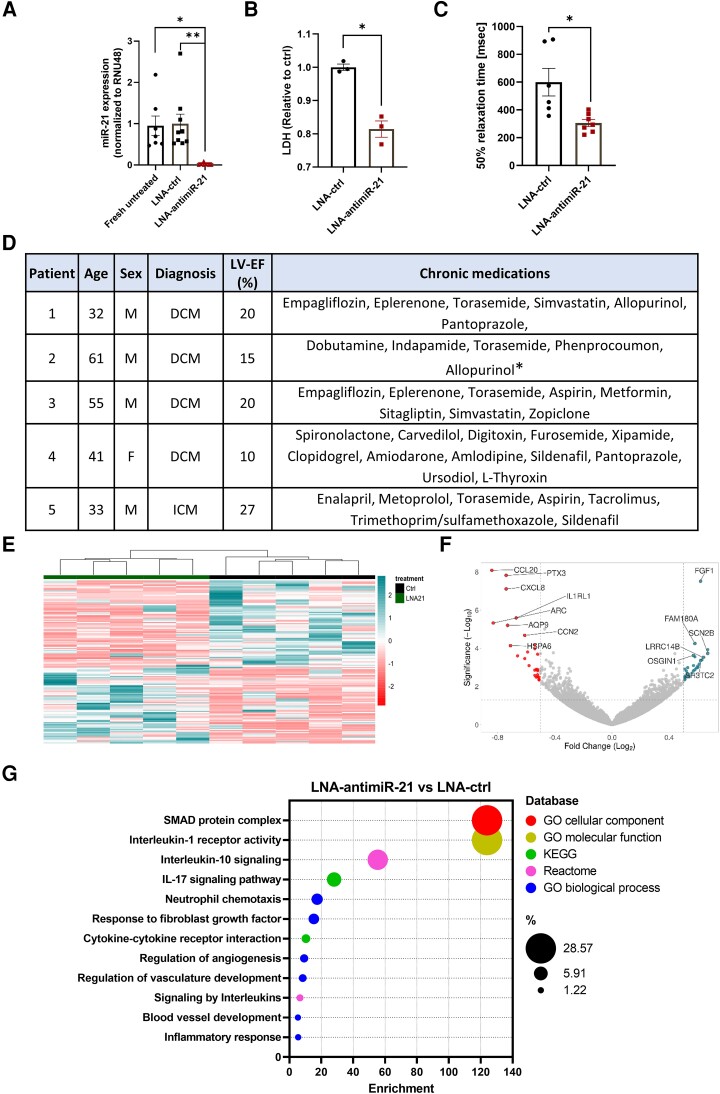

Locked nucleic acid (LNA)-antimiR-21, a modified form of nucleic acid, was used to silence miR-21-5p in LMS derived from five heart failure patients. Real-time-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) analysis demonstrated a near-total suppression of miR-21 expression when compared to fresh untreated tissue and LMS treated with a control LNA sequence (Figure 1A). To evaluate membrane integrity and cellular viability, a lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) assay was conducted, revealing reduced LDH levels upon treatment with LNA-antimiR-21 (Figure 1B). This indicates enhanced cell survival and viability as a direct result of the treatment.

Figure 1.

miR-21 inhibition results in cardioprotective effects in human heart failure LMS. (A) Reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) quantification of miR-21-5p in fresh untreated LMS and LMS treated with either LNA-ctrl or LNA-antimiR-21 (100 nM) for 96 h, normalized to RNU48 (*P < .05, **P < .01; one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA); bio n = 5, LMS n = 7–9). Data are displayed as mean ± SEM. (B) LDH quantification in the supernatant of LMS treated with LNA-ctrl or LNA-antimiR-21 (100 nM) for 96 h (*P < .05; Student’s t-test; bio n = 3, LMS n = 3). Data are displayed as mean ± SEM. (C) Half relaxation time (50% relaxation time, in msec) of LNA-ctrl and LNA-antimiR-21 treated LMS based on recordings obtained from biomimetic cultivation chambers (*P < .05; Student’s t-test; bio n = 5, LMS n = 6–7). Data are displayed as mean ± SEM. (D) Demographics, clinical characteristics, and concomitant medication of the enrolled patients. *patient 2 received levosimendan and bisoprolol as chronic treatment. The treatment was stopped two to three months before heart transplantation. M = male, F = female, DCM = dilated cardiomyopathy, ICM = ischaemic cardiomyopathy. LV-EF = left ventricular ejection fraction in %. (E) Heatmap of RNA-seq analysis illustrating top 150 differentially expressed genes—ranked by the mean difference between the groups: LNA-ctrl and LNA-antimiR-21. Bio n = 5, LMS n = 5; |Log₂FC|>0.5; P < .05); colour scaling shows the levels for a given gene, blue—up-, red—downregulated. (F) Volcano plot of RNA-seq dataset. X-axis: log2(fold change), Y-axis: -log(P-value). Top differentially expressed genes (DEGs) are highlighted. (G) Functional enrichment analysis of RNA-seq data. Selected clusters from different databases are included. X-axis—Normalized enrichment score LNA-antimiR-21 vs. LNA-control. False discovery rate (FDR) <.05.

LMS cultivation was done in biomimetic cultivation chambers that enabled continuous mechanical load and electrical stimulation of LMS (2–5 V, 2–4 ms, 0.2 Hz), and the contraction was monitored with Hall sensors integrated into each chamber. Functional analysis revealed a notable decrease in half relaxation time of LNA-antimiR-21 treated LMS, effectively halving its duration (Figure 1C). These findings align with previous in vivo studies in porcine myocardium after ischemia-reperfusion injury, which demonstrated improved left ventricular function and relaxation after LNA-antimiR-21 treatment.2 The observed improvement in cardiac relaxation may be attributed to enhanced cellular viability and suggests a potential mitigation of cardiac tissue fibrosis, which can lead to increase in stiffness and impaired relaxation.

Bulk RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) allows for an unbiased analysis of the entire transcriptome. We sought to characterize the transcriptomic profile after miR-21 inhibition in human LMS. The analysis included LMS obtained from five patients who experienced end-stage heart failure due to dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) or ischaemic cardiomyopathy (ICM). Clinical characteristics and concomitant medication of the patients are shown in Figure 1D. LMS from these tissues were treated with either LNA-antimiR-21 or LNA-control for 96 h. RNA was extracted using the miRNeasy Tissue/Cells Advanced Mini Kit (Qiagen 217684). Library was generated using NEBNext® Ultra II Directional RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (E7760L; New England Biolabs) and sequencing was performed in an Illumina NextSeq 550 sequencer using a High Output Flowcell for single reads (20024906; Illumina). Differential expression analysis was performed with DESeq2 (Galaxy Tool Version 2.11.40.6).

Using a setting of |log2FC|>0.5 and P-adj < .05, our analysis identified 60 differentially expressed genes (Figure 1E). Pathway enrichment and gene ontology analyses identified that the gene set associated with SMAD protein complex was the most strongly enriched (Figure 1G). This finding confirms the established association between miR-21 and SMAD proteins, which play crucial roles in the transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) signalling pathway. This pathway is responsible for regulating various cellular processes including cell proliferation, apoptosis, fibrosis, and tissue remodelling.4 Significant enrichments were observed in pathways associated with inflammation, such as interleukin signalling, neutrophil chemotaxis, and cytokine activity. Additionally, angiogenesis-related pathways, such as regulation of angiogenesis, regulation of vasculature development, and blood vessel development, exhibited notable enrichment. Moreover, the response to FGF1 stimulus was found to be enriched, with FGF1 itself being among the top five upregulated genes (Figure 1F). Of note, FGF1 is a predicted miR-21 target gene via TargetScan database.5FGF1 is known to regulate cardiac remodelling responses, including fibrosis and angiogenesis.6 Furthermore, several genes linked to cardiac fibrosis, including CCN2, CCL20, CCL2, TGFB2, and PTX3, displayed significant dysregulation. These results provide further evidence supporting the anti-fibrotic effects of inhibiting miR-21 in the heart. Additionally, they emphasize the relevance of miR-21 inhibition in targeting other remodelling-associated processes like inflammation and angiogenesis, although the majority of affetced pathways are invovled in cardiac fibrosis/cardiac fibroblasts.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to directly investigate the effects of miR-21 inhibition in failing human hearts and provide comprehensive functional and RNA-seq-based analyses of this treatment. First, our findings demonstrate the efficacy of using LNA as a powerful tool to target miR-21 in living adult heart multicellular preparations, resulting in a robust knockdown. Second, our results clearly indicate that silencing miR-21 enhances cellular viability leading to improved cardiac function, as evidenced by shorter relaxation time in the ex vivo LMS model. Third, our RNA-seq analysis underscores the significant impact of miR-21 inhibition on cardiac fibrosis, inflammation, and angiogenesis. These findings align with previous observations reported in animal models and in vitro experiments.1,2 We posit that illustrating phenotypical reverse remodelling in LMS, such as alterations in interstitial fibrosis and capillary rarefaction, is likely to necessitate a treatment duration extending beyond the temporal scope of this experiment. This is particularly relevant given that the tissue was obtained from severely diseased hearts and displayed a marked morphological phenotype associated with heart failure.

While our ex vivo model has narrowed objectives focusing on functional and molecular changes in the human failing heart, it cannot address the questions regarding the biodistribution, duration of the overall effects in the organ interplay, and the specificity of the organ delivery. Here existing literature suggests that LNA-based systemic antimiR-21 treatment in pigs results in robust knockdown of miR-21 in the heart, demonstrating efficacy for a minimum of 2 weeks.2 However, there was also a notable reduction of miR-21 levels in the lung and kidney, a phenomenon consistent with findings in other cardiac oligonucleotide-based therapies.7 In the context of heart failure, it is important to note the frequent occurrence of comorbidities affecting organs like the liver and kidneys. Indeed, pharmacologic inhibition of miR-21 has proven beneficial in animal models with heart failure-related comorbidities.8 This suggests potential advantages in suppressing miR-21 in compromised liver or kidney function. Nonetheless, further research is necessary to validate these potential benefits, and exploring innovative therapeutic approaches, including carrier systems (e.g. nanoparticle-based), antibody conjugates, and cell type–specific targeting moieties9 for achieving cardiac targeted drug delivery.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the MHH research core facility for transcriptomics (RGU transcriptomics).

Contributor Information

Naisam Abbas, Institute of Molecular and Translational Therapeutic Strategies (IMTTS), Hannover Medical School, Carl-Neuberg-Straße 1, 30625 Hannover, Germany; Fraunhofer Institute of Toxicology and Experimental Medicine (ITEM), Hannover, Germany.

Jonas A Haas, Institute of Molecular and Translational Therapeutic Strategies (IMTTS), Hannover Medical School, Carl-Neuberg-Straße 1, 30625 Hannover, Germany.

Ke Xiao, Fraunhofer Institute of Toxicology and Experimental Medicine (ITEM), Hannover, Germany.

Maximilian Fuchs, Fraunhofer Institute of Toxicology and Experimental Medicine (ITEM), Hannover, Germany.

Annette Just, Institute of Molecular and Translational Therapeutic Strategies (IMTTS), Hannover Medical School, Carl-Neuberg-Straße 1, 30625 Hannover, Germany.

Andreas Pich, Institute of Toxicology and Core Unit Proteomics, Hannover Medical School, Hannover, Germany.

Filippo Perbellini, Institute of Molecular and Translational Therapeutic Strategies (IMTTS), Hannover Medical School, Carl-Neuberg-Straße 1, 30625 Hannover, Germany.

Christopher Werlein, Institute of Pathology, Hannover Medical School, Hannover, Germany.

Fabio Ius, Department of Cardiothoracic, Transplantation and Vascular Surgery, Hannover Medical School, Hannover, Germany.

Arjang Ruhparwar, Department of Cardiothoracic, Transplantation and Vascular Surgery, Hannover Medical School, Hannover, Germany.

Jan Fiedler, Fraunhofer Institute of Toxicology and Experimental Medicine (ITEM), Hannover, Germany.

Natalie Weber, Institute of Molecular and Translational Therapeutic Strategies (IMTTS), Hannover Medical School, Carl-Neuberg-Straße 1, 30625 Hannover, Germany.

Thomas Thum, Institute of Molecular and Translational Therapeutic Strategies (IMTTS), Hannover Medical School, Carl-Neuberg-Straße 1, 30625 Hannover, Germany; Center for Translational Regenerative Medicine, Hannover Medical School, Carl-Neuberg-Straße 1, 30625 Hannover, Germany.

Declarations

Disclosure of Interest

T.T. is the founder and shareholder of Cardior Pharmaceuticals. T.T. has patented and licenced patents in the field of non-coding RNAs, including miR-21. All other authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data Availability

Data including transcriptome analyses can be obtained from the authors upon request.

Funding

This research was funded by the European Research Council Advanced Grant REVERSE and the Sonderforschungsbereich 1470.

Ethical Approval

Ethical agreement was obtained by Hannover Medical School and informed consent was obtained from the patients.

Pre-registered Clinical Trial Number

Not applicable.

References

- 1. Thum T, Gross C, Fiedler J, Fischer T, Kissler S, Bussen M, et al. MicroRNA-21 contributes to myocardial disease by stimulating MAP kinase signalling in fibroblasts. Nature 2008;456:980–4. 10.1038/nature07511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hinkel R, Ramanujam D, Kaczmarek V, Howe A, Klett K, Beck C, et al. AntimiR-21 prevents myocardial dysfunction in a pig model of ischemia/reperfusion injury. J Am Coll Cardiol 2020;75:1788–800. 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.02.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fischer C, Milting H, Fein E, Reiser E, Lu K, Seidel T, et al. Long-term functional and structural preservation of precision-cut human myocardium under continuous electromechanical stimulation in vitro. Nat Commun 2019;10:532. 10.1038/s41467-018-08003-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cavarretta E, Condorelli G. miR-21 and cardiac fibrosis: another brick in the wall? Eur Heart J 2015;36:2139–41. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Agarwal V, Bell GW, Nam JW, Bartel DP. Predicting effective microRNA target sites in mammalian mRNAs. Elife 2015;4:e05005. 10.7554/eLife.05005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Khosravi F, Ahmadvand N, Bellusci S, Sauer H. The multifunctional contribution of FGF signaling to cardiac development, homeostasis, disease and repair. Front cell Dev Biol 2021;9:672935. 10.3389/fcell.2021.672935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Stenvang J, Petri A, Lindow M, Obad S, Kauppinen S. Inhibition of microRNA function by antimiR oligonucleotides. Silence 2012;3:1. 10.1186/1758-907X-3-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Liu RH, Ning B, Ma XE, Gong WM, Jia TH. Regulatory roles of microRNA-21 in fibrosis through interaction with diverse pathways (review). Mol Med Rep 2016;13:2359–66. 10.3892/mmr.2016.4834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Roberts TC, Langer R, Wood MJA. Advances in oligonucleotide drug delivery. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2020;19:673–94. 10.1038/s41573-020-0075-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data including transcriptome analyses can be obtained from the authors upon request.