Abstract

This study examined longitudinal effects of adolescent and parent cultural stress on adolescent and parent emotional well-being and health behaviors via trajectories of adolescent and parent family functioning. Recent immigrant Latino adolescents (Mage=14.51) and parents (Mage = Mage=41.09; N=302) completed measures of these constructs. Latent growth modeling indicated that adolescent and parent family functioning remained stable over time. Early levels of family functioning predicted adolescent and parent outcomes. Baseline adolescent cultural stress predicted lower positive adolescent and parent family functioning. Latent class growth analyses produced a two-class solution for family functioning. Adolescents and parents in the low family functioning class reported low family functioning over time. Adolescents and parents in the high family functioning class experienced increases in family functioning.

Keywords: Latino parents and adolescents, family functioning, cultural stress, mental health, health risk behaviors

Family Functioning Trajectories among Latino Families: Links with Cultural Stress, Emotional Well-Being, and Behavioral Health

Adolescence is a time of rapid change and many transitions (Coleman, 2011), during which adolescents can experience lower emotional well-being (e.g., increased depressive symptoms, hopelessness, and decreased self-esteem) and increased risk for involvement in health compromising behaviors (e.g., alcohol and cigarette use, aggression, rule-breaking, and sexual risk taking). In the United States (U.S.), immigrant Latino adolescents may face additional stressors that can result from navigating multiple cultural contexts and belonging to a stigmatized group (Cano et al., 2015a). Compared to non-Latino White and Black youth, Latino adolescents report lower emotional well-being and higher levels of health risk behaviors (Gibson & Miller, 2010; Johnston et al., 2015; Kann et al., 2014). These health disparities are concerning given that 25% of children in the U.S. K-12 school system identify as Latino, and it is projected that by 2050, 30% of newborn children will be Latino (U.S. Census Bureau, 2014).

Latino immigrant youth often report better emotional well-being and behavioral health than their U.S.-born counterparts. However, research indicates that their emotional well-being and behavioral health worsens as they spend time in the U.S. (e.g., Alcántara, Estevez, & Alegría, forthcoming). One possible reason for this immigrant paradox might involve changes in family functioning (e.g., lower or higher family cohesion, involved parenting, and positive parenting) that might be influenced by cultural factors and can occur as Latino adolescents and their parents navigate the U.S. cultural context (Alcántara et al., in press). In the U.S., Latino immigrant adolescents and their parents can experience cultural stressors that result from navigating multiple cultural contexts, a negative contexts of reception, and experiencing discrimination (Lorenzo-Blanco et al., 2016a; Cano et al., 2015a; Gassman-Pines, 2015; Schwartz et al., 2014, 2015), and these cultural stressors can negatively influence family functioning, emotional well-being and health risk behaviors among adolescents and parents. For example, in a daily diary study (Gassman-Pines, 2015), Mexican immigrant parents reported that, on days when they experienced workplace discrimination, they interacted less warmly and more aversely with their children, experienced lower emotional well-being, and reported more child internalizing and externalizing behaviors. In a longitudinal study with recent immigrant Latino families (Cano et al., 2015b), positive family functioning predicted lower adolescent depressive symptoms and health-risk behaviors six months later, and family functioning was compromised in the presence of parent-child acculturation discrepancies. In another study using the same data, Córdova et al. (2016) examined how latent classes of parent-adolescent family functioning discrepancy scores developed over time. They reported that, compared to adolescents in the low family functioning discrepancy classes, adolescents in the high family functioning discrepancy class engaged in more sexual risk behaviors.

However, most of the published research has (a) used cross-sectional study designs, (b) not investigated how parent and adolescent views of family functioning evolve separately and together over time, or (c) focused on parent-adolescent family functioning discrepancies. As a result, we know less about the separate developmental trajectories of both parent- and adolescent-reported family functioning. To address this gap in the literature, and informed by ecodevelopmental theory, which posits that the family is the most proximal unit to youth development and that family functioning can change over time, we examined the separate developmental trajectories of adolescent- and parent-reported family functioning. The present study not only helps to bridge the literatures on the immigrant paradox (Alcántara et al., in press) and child and family functioning, but it also advances the child developmental literature in several key ways. First, we operationalized family functioning as a multifaceted construct consisting of family cohesion, positive parenting, and involved parenting. Second, we examined the effects of two separate family functioning trajectories (i.e., one for adolescents and one for parents) on the emotional well-being and health risk behaviors of both recent immigrant Latino adolescents and their parents. Third, heterogeneity exists in how well families function and prior studies have not identified types of Latino families who may differ from each other based on the developmental trajectories of both parent and adolescent views of family functioning trajectories. As such, in the present study, we empirically identified unique subgroups of recent immigrant parents and adolescents who differed based on family functioning trajectories for adolescents and their parents. Finally, we examined potential differences across these family functioning subgroups in terms of adolescent and parent emotional well-being and behavioral health. Informed by the Family Stress Model (FSM), which suggests that parent cultural stress may lead to changes in family functioning to negatively affect youth development (Conger & Conger, 2010) as well as the cultural stress literatures, we investigated (a) whether parent and adolescent cultural stress predicted lower initial levels of and change in parent- and adolescent-reported family functioning, and (b) whether latent classes of family functioning differed by parent and adolescent cultural stress.

Theoretical Basis: Ecodevelopmental Theory and the Family Stress Model

Ecodevelopmental Theory (Szapocznik & Coatsworth, 1999) posits that adolescent development is influenced by proximal (i.e., settings in which adolescents directly participate) and distal (i.e., settings in which adolescents do not directly participate) contexts, with the family representing the most proximal system for adolescent development. The family environment might be particularly relevant for Latino youth given the emphasis on cultural values that promote close family relationships in Latino cultures (Lugo Steidel & Contreras, 2003). Importantly, ecodevelopmental theory recognizes that contextual processes such as family functioning can change over time.

Proximal and distal contexts that may lead to changes in family functioning and influence youth development can include cultural stressors experienced by adolescents and their parents. These cultural stressors can involve adolescents’ and parents’ experiences with discrimination, acculturative stress, and a negative context of reception (which we define below; Cano et al., 2015a; Lorenzo-Blanco et al., 2016 a, b). According to the Family Stress Model (FSM), parents’ cultural stressors may indirectly influence Latino adolescents’ emotional well-being and behavioral health by negatively impacting parents’ emotional well-being and the overall functioning of the family (e.g., Conger et al., 2010). Thus, according to ecodevelopmental theory and the FSM, cultural stressors experienced by adolescents and parents may lead to changes in family functioning, which in turn may affect adolescents’ and parents’ emotional well-being and behavioral health.

Family Functioning, Emotional Well-being and Behavioral Health

Family functioning can be characterized as a multifaceted construct consisting of parental involvement, family cohesion, positive parenting, and other positive relational processes (Tolan, Gorman-Smith, Huesmann, & Zelli, 1997). The importance of positive family functioning vis-à-vis the positive emotional well-being and behavioral health of Latino adolescents and parents has been demonstrated empirically in a number of studies. Among Latino youth and adults, positive family functioning has been linked with lower depressive symptoms (e.g., Cano et al., 2015b; Lorenzo-Blanco & Cortina, 2013); reduced risk for suicidality (e.g., Baumann, Kuhlberg, & Zayas, 2010), lower substance use (e.g., Canino, Vega, Sribney, Warner, & Alegria, 2008; Cano et al., 2015b), lower sexual risk taking (e.g., Cano et al., 2015b), less aggressive and rule-breaking behavior (e.g., Santisteban et al., 2012), and higher self-esteem (Schwartz et al., 2015).

Cultural Stress, Family Functioning, Emotional Well-Being and Behavioral Health

Cultural stress may affect family functioning, and, in turn, the health of Latino youth and parents (e.g., Gassman-Pines, 2015; Lorenzo-Blance et al., 2016a). Cultural stress refers to a constellation of interrelated but distinct factors that can contribute to the stress experience among Latino immigrant families, including discrimination, a negative context of reception, and acculturative or bicultural stress (Lorenzo-Blanco et al., 2016a; Cano et al., 2015a). Discrimination refers to experiences of unfair or differential treatment such as being teased or ostracized for being an immigrant or for having an accent when speaking English (Perez, Fortuna, & Alegría, 2008). A negative context of reception refers to immigrants’ perception of not feeling welcomed in their U.S. settlement community, including lack of access to good employment and schools (Schwartz et al., 2014). Acculturative or bicultural stress can include pressures involved in learning a new language, maintaining one’s native language, and balancing differing cultural values and ways of behaving (Torres, Driscoll, & Voell, 2012).

According to the FSM, cultural stressors can negatively influence family functioning and, ultimately, the emotional well-being and behavioral health of Latino adolescents and parents (e.g., Conger et al., 2010). Supporting this proposition, Lorenzo-Blanco and colleagues (2016a) investigated, in a sample of recent immigrant Latino families, the developmental trajectories of parents’ cultural stress over a two-year period. They found that early levels of and increases in parent cultural stress predicted worse adolescent- and parent-reported family functioning at a later time-point, which then predicted lower youth self-esteem and increased alcohol and cigarette use six months later. In a related study, using the same dataset, Lorenzo-Blanco and colleagues (2016b) employed a cross-lagged model to test whether, over a two-year period, parent cultural stress led to higher depressive symptoms in parents or whether parent depressive symptoms led parents to perceive more cultural stress. Findings indicated that parent cultural stress at earlier time-points predicted parent depressive symptoms at later time-points but not vice versa. They also found that parent cultural stress and parent depressive symptoms predicted lower family functioning at a later time-point, which then predicted lower youth self-esteem and higher youth alcohol and cigarette use.

Although these studies have advanced our understanding of how cultural stressors develop over time to influence family functioning, parent depressive symptoms, and adolescent health outcomes, in the present study, we attempt to ascertain the separate development of adolescent- and parent-reported family functioning trajectories and the role of cultural stress in the evolution of family functioning. According to ecodevelopmental theory and the FSM, family functioning may evolve as Latino immigrant families experience cultural stress. However, studies have not tested whether, and how, family functioning changes as immigrant families navigate the U.S. cultural context. As such, studying the effects of cultural stressors on longitudinal trajectories of adolescent- and parent-reported family functioning will enhance researchers’ understanding of how cultural stressors impact Latino families. Such understanding may also provide insights into the best timing of interventions to promote family functioning and prevent the negative consequences of cultural stress on family functioning. In turn, such interventions would be expected to promote the emotional and behavioral health of Latino adolescents and parents.

Additionally, prior studies on family functioning, emotional well-being and health risk behaviors among Latinos have relied on variable-centered approaches and ignored individual differences in how well Latino families function. However, given the heterogeneity that exists among Latino families vis-à-vis family functioning, it is important to identify subgroups of families that may differ in regard to adolescent- and parent-reported family functioning trajectories. Whereas some families may be characterized by high adolescent-reported and high parent-reported family functioning trajectories, others may be characterized by low adolescent- and low parent-reported family functioning trajectories. Still others may be characterized by adolescents with high and parents with low family functioning trajectories or vice versa. Identifying distinct groups of families who differ based on their family functioning trajectories may facilitate adapting interventions based on the family’s existing resources and needs.

The Present Study

The present six-wave longitudinal study with recent immigrant Latino families advances theory, research, and intervention development vis-à-vis family functioning, cultural stress, and health outcomes through the following two aims: First, informed by ecodevelopmental theory and the FSM, we examined how adolescent- and parent-reported family functioning changed over time as a function of adolescents’ and parents’ cultural stress experiences. Doing so allowed us to test one of the tenets of the FSM, which posits that cultural stress can lead to changes in family functioning. Second, given individual differences in how well families function, we also sought to identify unique subgroups of family functioning classes that differed with regard to adolescent- and parent-reported family functioning trajectories. We also investigated the influence of family functioning trajectories and unique family functioning classes on adolescent and parent emotional well-being and health risk behaviors.

According to ecodevelopmental theory, family functioning can undergo developmental changes as adolescents and parents navigate the U.S. cultural context. As such, we first examined the longitudinal trajectories of adolescent- and parent-reported family functioning as two separate latent constructs. Next, because the FSM posits that cultural stress can compromise positive family functioning and thereby impact the health of parents and adolescents, we investigated how parent and adolescent cultural stressors impacted parent- and adolescent-reported family functioning trajectories, respectively. Third, because both ecodevelopmental theory and the FSM posit that family functioning is an important determinant of adolescent and parent health outcomes, we investigated the degree to which adolescent- and parent-reported family functioning trajectories separately predicted a range of adolescent and parent outcomes. Lastly, using latent class growth analysis, we sought to identify distinct subgroups of parents and adolescents who differed based on their family functioning trajectories, and we then investigated how these empirically derived family functioning subgroups influenced adolescent and parent outcomes and differed from each other based on parent and adolescent cultural stress. Based on theory and prior research, we propose the following hypotheses and research question:

1. Consistent with ecodevelopmental theory, we expected family functioning to change over time. Specifically, and consistent with the notion that family functioning may deteriorate as Latino families navigate the U.S. cultural context, we expected family functioning for adolescents and parents to decline over time.

2. Based on the FSM and its extension into cultural stress (Lorenzo-Blanco et al., 2016a), we expected adolescent and parent cultural stress to predict (a) lower initial levels of positive adolescent and parent family functioning and (b) a steeper decline in adolescent and parent family functioning over time.

3. In accordance with ecodevelopmental theory and the FSM, we expected that greater positive family functioning at baseline and over time would predict more favorable emotional well-being and behavioral health outcomes in adolescents and parents.

4. We also sought to determine whether we could empirically identify subgroups of adolescents and parents based on their family functioning trajectories (in terms of both baseline levels and change over time). Given the lack of longitudinal research in this area, we did not have an empirical basis on which to hypothesize the specific number of groups that would emerge or on how these groups would change over time. However, as evident in prior research, we expected to find groups of adolescents and parents who would fall into “high” and a “low” functioning groups, and we expected that adolescents and parents in groups characterized by “low” family functioning would report higher levels of cultural stress, worse emotional well-being, and worse behavioral health compared to parents and adolescents in high family functioning groups.

Method

Sample

Data for the present study came from a six-wave longitudinal study on cultural stress, family functioning, and health among recently immigrated Latino families (Schwartz et al., 2014). The sample consisted of 302 adolescent-caregiver dyads from Los Angeles (N = 150) and Miami (N = 152) who had resided in the U.S. for five years or less at baseline. Forty-seven percent of the adolescent sample was female (Mage = 14.51, SD = .88). Each adolescent participated with a primary caregiver, to whom we refer as “parents” in the present study. Parents included mothers (74.0%), fathers (22.1%), stepparents (2.1%), and grandparents or other relatives (1.7%). The mean parent age was 41.09 years (SD = 7.09) at baseline. Approximately 80% of parents reported annual incomes of less than $25,000, and 78.6% had graduated from high school. Miami families were primarily from Cuba (61%), the Dominican Republic (8%), Nicaragua (7%), Honduras (6%), and Colombia (6%). Los Angeles families were primarily from Mexico (70%), El Salvador (9%), and Guatemala (6%). The majority of adolescents (98%) and parents (98%) reported Spanish as their “first or usual language”; 82% of adolescents and 87% parents reported “speaking mostly Spanish at home” and 16% of the adolescents and 11% of parents reported speaking “English and Spanish about the same at home.”

Procedures

School selection and participant recruitment.

Families were recruited from randomly selected schools in Miami-Dade (10 schools) and Los Angeles Counties (13 schools). To capture the greatest possible representation of recent Latino immigrant families from these two counties, we selected schools whose student body was at least 75% Latino. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at the University of Miami and the University of Southern California, and by the Research Review Committees for each participating school district.

Assessments.

Baseline (T1) data were gathered during the summer of 2010, and subsequent time points occurred during Spring 2011 (T2), Fall 2011 (T3), Spring 2012 (T4), Fall 2012 (T5), and Spring 2013 (T6). Participants completed assessments at the universities’ research centers, schools, community locations, or their homes. Assessments were available in Spanish and English, and each parent and adolescent was asked to select the language in which she or he wanted to complete the assessment. Participants completed assessments with an audio computer-assisted interviewing (A-CASI) system (Turner et al., 1998). Parents provided informed consent for themselves and their adolescents. Adolescents provided informed assent for themselves. Parents received $40 at baseline and an additional $5 at each subsequent time point. Adolescents received a voucher for a movie ticket at each time point.

Measures

We translated all of our measures from English into Spanish, and we used a simultaneous translation process because our participants spoke different Spanish dialects (i.e., Cuban Spanish in Miami and Mexican Spanish in Los Angeles). Two translators in Miami and two translators in Los Angeles forward and back translated all the measures from English into Spanish. The Miami research team then reviewed the translations from the Los Angeles research team, and the Los Angeles team reviewed the translations from the Miami team. Any discrepancies in translations were resolved through phone conferences. In instances where the research team could not find a resolution for translation discrepancies, we used both the "Miami" and "Los Angeles" expressions in the item content that was displayed to participants.

Unless otherwise specified, we used a 5-point Likert-type scale for all measures, ranging from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 5 (Strongly Agree).

Adolescent and parent family functioning

was assessed at each of the first five time points using parent-adolescent (i.e., parental involvement and positive parenting) and whole-family relational processes (i.e., family cohesion). Parental involvement and positive parenting were assessed using the Parenting Practices Scale (Gorman-Smith, Tolan, Zelli, & Huesmann, 1996). The parental involvement subscale consisted of 15 items for adolescents (α = .87; Sample item: “When was the last time that you talked with your parents about what you were going to do for the coming day?”) and 19 items for parents (α = .79; Sample item: “How many of your child’s friends do you know?”). The positive parenting subscale consisted of 9 items for adolescents (α = .87; Sample item: “When you have done something that your parents approve of, how often do they say something nice about it?”) and 9 for parents (α = .70; Sample item: “When your child has done something that you like or approve of, do you mention it to someone else?”). Family cohesion was measured using the corresponding 6-item subscale from the Family Relations Scale (Tolan, Gorman-Smith, Huesmann, & Zelli, 1997). Sample items include “Family members feel very close to each other” (α = .87 for adolescents and .76 for parents).

Adolescent and parent cultural stress

was assessed at T1 and treated as two separate latent variables - one for adolescents (see Cano et al., 2015a) and one for parents (see Lorenzo-Blanco et al., 2016a, 2016b). For parents, cultural stress was measured in terms of discrimination, negative context of reception, and acculturative stress. For adolescents, cultural stress was measured in terms of discrimination, a negative context of reception, and bicultural stress. For parents and adolescents, perceived discrimination was measured using the 7-item Perceived Discrimination Scale (Phinney, Madden, & Santos, 1998; α = .87; Sample item: “How often do people your age treat you unfairly or negatively because of your ethnic background?”). This measure uses a 5- point Likert response format ranging from 0 (Not at all) to 4 (Almost always). Negative context of reception (Schwartz et al., 2014) was measured among adolescents and parents using a 6-item scale developed using the present dataset (α = .83; Sample item: “I don’t have the same chances in life as people from other countries”). Parents and adolescents indicated the degree to which they agreed with each statement on a scale ranging from 0 (Not at all) to 4 (Strongly Agree). Acculturative Stress among parents was measured with 24 items from the Multidimensional Acculturative Stress Inventory, which assess stress that originates from U.S. (sample item: “It bothers me that I speak English with an accent”) and Latino sources (sample item: “I feel pressure to speak Spanish”) (MASI; Rodriguez, Myers, Mira, Flores, & Garcia-Hernandez, 2002). Parents indicated on a Likert Scale, ranging from 0 (Not at all stressful) to 4 (Extremely stressful), the degree to which they each item applied to them (α = .93). Bicultural stress among adolescents was measured using 20 items from the Bicultural Stress Scale (Romero & Roberts, 2003; α = .89; Sample item: “I feel embarrassed because of my accent). Adolescents rated on a scale ranging from 1 (Never happened to me) to 4 (Very stressful) the degree to which each statement applied to them.

Adolescent and parent depressive symptoms

were assessed at T1 and T6 using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977); α = .93 for parents and α = .93 for adolescents, sample item: “I felt like crying this week”. Adolescents and parents indicated on a scale ranging from 0 (Strongly disagree) to 4 (Strongly agree), how depressed they have felt during the past week. Higher scores indicate greater depressive symptoms. The CES-D has been translated into Spanish and used frequently with Latinos (e.g., Todorova, Falcón, Lincoln, & Price, 2010).

Adolescent self-esteem

was assessed at T1 and T6 with 10 items (α = .74; Sample item: “I feel that I have a number of good qualities”) from the Rosenberg (1968) Self-Esteem Scale. This measure has been used widely with Spanish-speaking populations (Schmidt & Allik, 2005).

Adolescent hope

was measured at T1 and T6 with the Children’s Hope Scale (Edwards, Ong, & Lopez, 2007). This measure consists of six items and measures the extent to which young people are optimistic about their future (α = .86; Sample item: “I can think of many ways to get the things in life that are most important to me”).

Adolescent aggressive and rule-breaking behavior

was assessed at T1 and T6 with 32 items from the Youth Self-Report (YSR; Achenbach, Dumenci, & Rescorla, 2002). We used 17 items to measure aggressive behavior (α = .93, sample item: “I am mean to others”) and 15 items to measure rule-breaking behavior (α = .93, sample item: “I break rules at home, school, or elsewhere”). Adolescents rated, on a scale ranging from 0 (Not true) to 2 (Often or very often true), their behavior within the previous six months.

Adolescent and parent substance use.

Adolescent substance use was assessed in terms of cigarette smoking, binge drinking, and marijuana use with a modified version of the Monitoring the Future survey (Johnston et al., 2015). Parent substance use was assessed with the same items and assessed cigarette smoking, alcohol, and drug use. Adolescents and parents responded to questions regarding the frequency of their substance use in the 90 days prior to assessment. Because of low base rates, we dichotomized the responses to create binary variables (1=Use vs. 0=Nonuse) at T1 and T6.

Adolescent sexual risk taking

was assessed with four questions. One question asked adolescents about how many times in the last 90 days they had engaged in vaginal or anal sex (question 1). Because many young people engage in oral sex without intercourse (Lindberg et al. 2008), we asked separately about oral sex (question 2). We also asked participants about how often they used a condom during vaginal or anal sex (question 3) and oral sex (question 4) during the past 90 days. Response options ranged from 0 (Never) to 4 (Always). Because of low base rates we dichotomized the responses to create binary variables at T1 and T6 as follows: Question 1: 1 = Had sex vs. 0 = Did not have vaginal or anal sex; Question 2: 1 = Did have oral sex vs. 0 = Did not have oral sex; Question 3: 1 = Did not use condom during vaginal or anal sex vs. 0 = Used condom during vaginal or anal sex; Question 4: 1 = Did not use condom during oral sex vs. 0 = Used condom during oral sex. Additionally, adolescents who reported that they did not have vaginal or anal sex in response to question 1, were coded as 0 for questions 2-4.

Analytic Overview

Analyses were conducted in Mplus version 7.2 (Muthen & Muthen, 1998 – 2007) using Maximum Likelihood with Robust Standard Errors (MLR), which is robust to non-normality and non-independence of observations when used with nested data (Kauermann & Carroll, 2001). Analyses proceeded in eight steps: (1) examining the longitudinal invariance of two latent family functioning variables - one for parents and one for adolescents (Little, 2013); (2) estimating two growth curve models for family functioning – one for parents and one for adolescents; (3) investigating the degree to which parent and adolescent cultural stress at T1 predicted adolescent and parent family functioning trajectories and examining the effect of parent and adolescent family functioning trajectories on parent and adolescent outcomes at T6; (4) explored site differences in the predictive effects of parent and adolescent cultural stress at T1 on parent and adolescent reports of family functioning and outcomes; (5) estimating a latent class growth analysis to determine the number and characteristics of empirically distinguishable family functioning trajectory classes (based on parent-and adolescent-reported intercepts and slopes; Nagin, 2005); (6) predicting family functioning class membership as a function of demographic variables and cultural stress; (7) predicting parent and adolescent outcomes as a function of family functioning class membership: and (8) examining site differences in the predictive effects of parent and adolescent outcomes as a function of family functioning class membership.

Results

Step 1: Longitudinal Invariance of Parent- and Adolescent-Reported Family Functioning

One prerequisite for latent growth curve modeling (LGCM) is structural invariance of the same latent construct at each time point (Little, 2013). As such, we evaluated separately whether the structures of the parent- and adolescent-reported family functioning latent variables were invariant across the first five time points by comparing the fit of the following three models, separately for parents and adolescents: (1) an unconstrained model with all factor loadings and item intercepts free to vary across time points; (2) a metric invariance model with factor loadings (but not item intercepts) constrained equal across time points; and (3) a scalar invariance model with factor loadings and item intercepts constrained equal across time points (Dimitrov, 2010). Model fit was evaluated using three fit indices: the chi-square index (χ2), the comparative fit index (CFI), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) (West, Taylor, & Wu, 2012). Adequate model fit was defined as CFI ≥ .90 and RMSEA ≤ .08. We report the chi-square index but did not use it to evaluate model because it tends to be overpowered (West et al., 2012).

As recommended by Little (2013), we conducted tests of metric invariance by comparing models (1) and (2), and we conducted tests of scalar invariance by comparing models (2) and (3). For the assumption of longitudinal invariance to be satisfied, both model comparisons need to yield a conclusion of invariance. Such a conclusion would be supported if at least two of three criteria were satisfied: Δχ2 not significant (p >.05), ΔCFI < .01, and ΔRMSEA < .01 (Widaman, Ferrer, & Conger, 2010). Additionally, according to Little (2013), it is acceptable to use variables for which partial metric or scalar invariance is retained. Partial metric and scalar invariance would be supported if the majority of loadings or intercepts were invariant across time points.

Model 1 (the unconstrained model) for parent-reported family functioning yielded good fit, χ2 (60) = 106.015, p < .001; CFI = .972; RMSEA = .050. Both metric (Δχ2 (8) = 5.60, p = .69; ΔCFI = .002; ΔRMSEA = .004) and scalar invariance (Δχ2 (20) = 36.29, p < .05; ΔCFI = .009; ΔRMSEA = .001) were supported, suggesting that the structure of the parent-reported family functioning variable was equivalent over time. Model 1 (the unconstrained model) for adolescent-reported family functioning also yielded good fit, χ2 (60) = 79.576, p < .05; CFI = .990; RMSEA = .033. Although metric (Δχ2 (8) = 11.02, p = .20; ΔCFI = .001; ΔRMSEA < .001) invariance was supported, scalar invariance (Δχ2 (12) = 337.85, p < .05; ΔCFI = .015; ΔRMSEA = .013) was not. However, freeing the intercept for the parental involvement variable permitted us to retain the assumption of partial scalar invariance (Δχ2 (16) = 25.74, p = .06; ΔCFI = .005; ΔRMSEA = .002). Because at least partial invariance was established for parent- and adolescent-reported family functioning, we were able to estimate growth curves (Little, 2013).

Step 2: Estimation of Latent Growth Curve Models (LGCM)

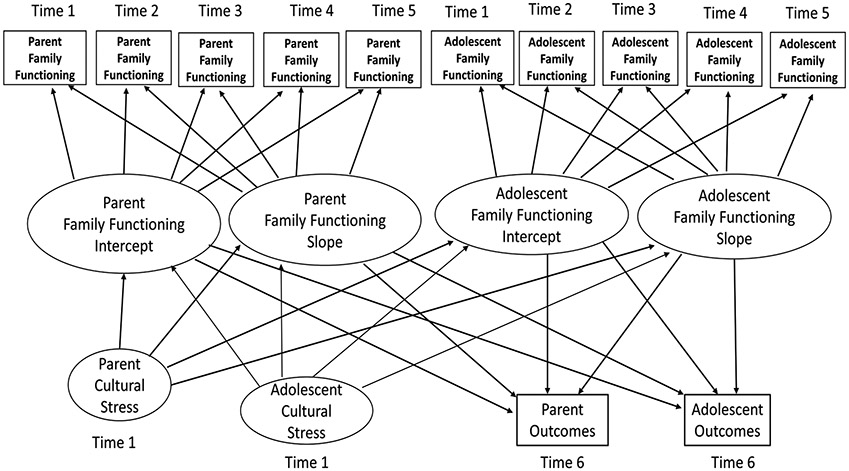

We evaluated trajectories of parent- and adolescent-reported family functioning using LGCM (see top part of Figure 1). Because estimating the effect of a latent construct on dichotomous outcomes requires 15 dimensions of mathematical integration per outcome, we saved the factor scores for the latent parent-and adolescent-reported family functioning variables from the longitudinal invariance models back into the dataset and used these factor scores as indicators in LGCM. The LGCM fit the data well, χ2 (36) = 53.455, p < .05; CFI = .992; RMSEA = .040 (90% CI = .013-.062). Although the mean linear slopes for parent- and adolescent-reported family functioning were not significant (parent = .03, p = .26; adolescent = .08, p = .13), there was significant variability around the mean slopes (s2 = .09, p < .001 for parents; s2 = .78, p < .001 for adolescents), indicating that parent-and adolescent-reported family functioning may vary across individuals. There was also significant variability around the intercepts (s2 = 3.77, p < .001 for parents; s2 =16.21, p < .001 for adolescents), documenting individual differences in baseline levels of parent- and adolescent-reported family functioning.

Figure 1.

Latent Family Functioning Growth Curve Model - Cultural Stress Predicting Family Functioning and Family Functioning predicting Adolescent and Parent Outcomes.

Step 3: Cultural Stress as Predictor of Family Functioning & Family Functioning as Predictor of Parent and Adolescent Outcomes.

Next, as shown in Figure 1 (bottom part), we allowed parent and adolescent cultural stress to predict the slopes and intercepts of both parent- and adolescent-reported family functioning. We also allowed the intercepts and slopes for parent- and adolescent-reported family functioning to predict adolescent and parent outcomes. We controlled for age, gender, site (Miami versus Los Angeles), and years in the U.S., along with baseline levels of the continuous outcome variables. We did not control for prior levels of categorical outcome variables because scores on dichotomous variables can remain the same over time even though developmental change has occurred (Agresti, 2007). Additionally, controlling for prior levels of categorical variables may, in some cases, result in inflated standard errors for model parameters, potentially rendering baseline-adjusted results unstable or invalid (Glymour, Weuve, Berkman, Kawachi, & Robins, 2005). Also, because modeling categorical outcomes in MLR requires numerical integration, Mplus does not provide model fit indices for these analyses (Muthén & Muthén, 2010).

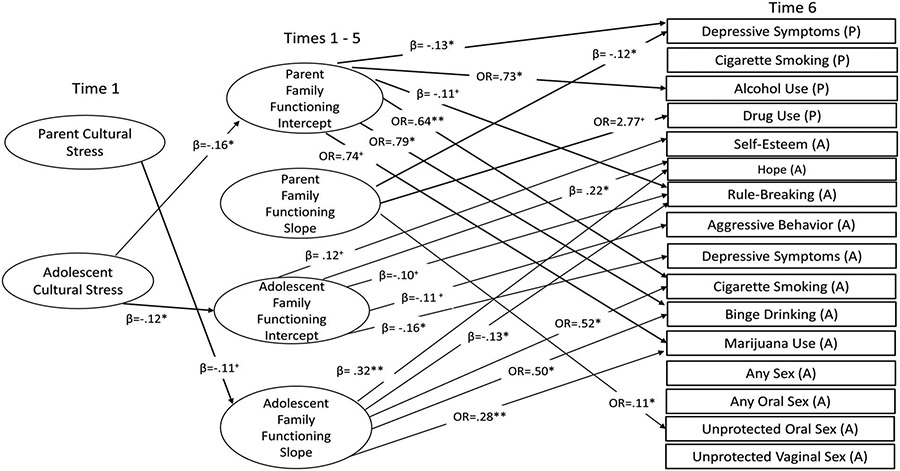

As shown in Table 1 and Figure 2, adolescent cultural stress predicted lower parent- (β = −.16, p < .05) and adolescent-reported (β = −.12, p < .05) family functioning intercepts, and parent cultural stress marginally and negatively predicted the adolescent-reported family functioning slope (β = −.11, p = .097). Moreover, the intercept (i.e., Time 1) for parent-reported (higher) family functioning predicted less youth rule breaking (β = −.10, p = .067), cigarette smoking (OR = .64, p < .001), alcohol use (OR = .73, p <.05), binge drinking (OR = .79, p < .05), and marijuana use (OR = .74, p = .07), and lower parent depressive symptoms (β = −.13, p < .05), at T6. The slope for parent-reported (higher) family functioning predicted lower unprotected youth oral sex (OR = .11, p < .05), lower parent depressive symptoms (β = −.12, p <.05), and marginally more parent drug use (OR = 2.77, p = .08). Additionally, the intercept for adolescent-reported (higher) family functioning predicted higher youth self-esteem (β = .12, p = .09), higher hope (β = .22, p < .05), lower rule breaking (β = −.10, p = .09), lower aggressive behavior (β = −.11, p = .06), lower youth depressive symptoms (β = −.16, p < .05), and lower parent drug use (OR = .76, p = .067) at T6. Further, the slope of adolescent-reported (higher) family functioning predicted higher youth hope (β = .32, p < .001), less rule-breaking (β = −.13, p < .05), lower odds of cigarette smoking (OR = .52, p < .05), lower odds of marijuana use (OR = .28, p < .001), and lower odds of binge drinking (OR = .50, p < .05) at T6. Lastly, the adolescent-reported family functioning slope predicted lower parent drug use (OR = .67, p < .05) at T6.

Table 1.

Cultural Stress Predicting Family Functioning Intercepts and Slopes & Family Functioning Intercepts and Slopes Predicting Parent and Adolescent Outcomes

| Outcome | Predictor | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parent-reported | Adolescent-reported | |||||

| Cultural Stress |

Family Functioning Intercept |

Family Functioning Slope |

Cultural Stress |

Family Functioning Intercept |

Family Functioning Slope |

|

| Family Functioning Intercept (P) | −.10 | - | - | −.16* | - | - |

| Family Functioning Slope (P) | −.02 | - | - | .01 | - | - |

| Family Functioning Intercept (A) | −.01 | - | - | −.12* | - | - |

| Family Functioning Slope (A) | −.12+ | - | - | .06 | - | - |

| Self-esteem (A) | - | .02 | .04 | - | .12+ | .11 |

| Hope (A) | - | .08 | .02 | - | .22* | .32** |

| Rule Breaking (A) | - | −.10+ | −.03 | - | −0.10+ | −.13* |

| Aggressive Behavior (A) | - | −.01 | −.05 | - | −.11+ | −.09 |

| Depressive Symptoms (A) | - | −.03 | .00 | - | −.16* | −.08 |

| Cigarette Smoking (A) | - | .64** | 5.84 | - | 1.02 | .52* |

| Binge Drinking (A) | - | .79* | 1.34 | - | .95 | .50* |

| Marijuana Use (A) | - | .74+ | .83 | - | 92 | .28** |

| Any Anal or Vaginal Sex (A) | - | 1.01 | .69 | - | .97 | 1.05 |

| Any Oral Sex (A) | - | 1.14 | .11 | - | .99 | 1.04 |

| Unprotected Vaginal or Anal Sex (A) | - | 1.16 | .19 | - | 1.00 | .92 |

| Unprotected Oral Sex (A) | - | 1.00 | .11* | - | .97 | 1.09 |

| Depressive Symptoms (P) | - | −.13* | −.12* | - | −.04 | −.05 |

| Cigarette Smoking (P) | - | .86 | .35 | - | .99 | .92 |

| Alcohol Use (P) | - | .73* | .75 | - | 1.00 | .79 |

| Drug Use (P) | - | .98 | 2.77+ | - | .74 | .67* |

Note. * p < .05; **p < .001; +p = .05 - .09

Figure 2.

Parent and Adolescent Cultural Stress Predicting Parent-and Adolescent-Reported Family Functioning Intercepts and Slopes & Parent-and Adolescent-Reported Family Functioning Intercepts and Slopes Predicting Parent and Adolescent Outcomes. Significant and marginally significant results are shown.

Step 4. Model Invariance Across Sites

Next, we examined whether the findings from Step 3 differed across site (Miami vs. Los Angeles). We compared an unconstrained model (will all paths free to vary across sites) to a constrained model (with each path constrained to be equal across site) using the likelihood ratio test to evaluate the null hypothesis of equivalent findings across sites. This test provides only a chi-square difference and does not provide any other SEM fit indices. Our results indicated no significant difference across site; Δχ2(66) = 81.01; p = .101, suggesting that findings from step 3 do not vary for families in Miami versus Los Angeles.

Step 5. Latent Class Growth Analysis

Next, using latent class growth analysis, we identified subgroups of parents and adolescents who differed based on their family functioning intercepts and slopes (Nagin, 2005). Following Nagin (2005), we fixed the intercept and slope variances to zero so that the classes extracted would be as homogenous as possible in terms of their starting points and change trajectories. We used five criteria to decide on the number of classes (Nylund, Asparouhov, & Muthén, 2007). First, the Vuong-Lo-Mendell-Rubin likelihood ratio test (LRT) indicates the extent to which the −2 log likelihood value for a model with k classes is significantly smaller than the corresponding value for a model with k-1 classes. Second, the sample-size-adjusted Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and Bayesian Information (BIC) provide an additional basis for comparing models, where lower values indicate better fit. Third, to ensure stability of the class solution, each class had to represent more than 5% of the sample. Fourth, classes had to be substantively different from one another (i.e., one class could not simply be a variant on another class). Fifth, entropy values and posterior probabilities of correct classification should be at least .70, and when entropy is lower than .70, posterior class membership probabilities should be used as weighting variables (Bandeen-Roche, Miglioretti, Zeger, & Rathouz, 1997).

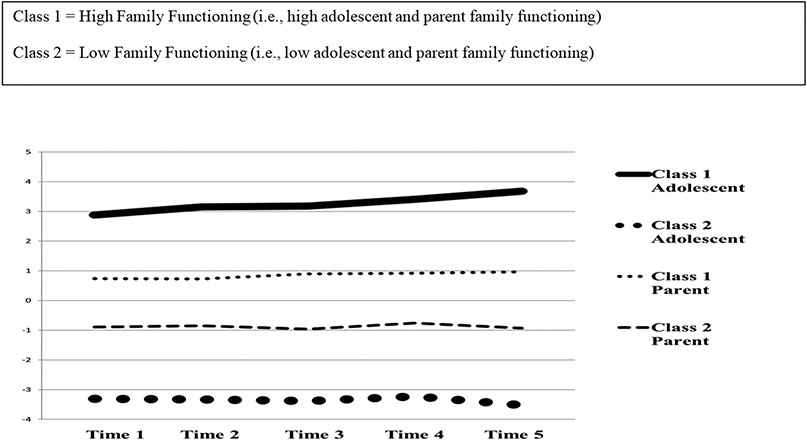

Based on these criteria, we extracted a two-class solution, LRT = 578.032, p < .05 (see Figure 3) using adolescent- and parent-reported family functioning slopes and intercepts. The entropy value was .85, and posterior probabilities ranged from .94 to .97. The first class represented 51.33% of the sample (n = 155), and the second class represented 48.68% of the sample (n = 147). For class 1, the parent-reported family functioning intercept and linear slope were .71 (p < .001) and .05 (p = .09), respectively, and the adolescent-reported family functioning intercept and linear slope were 2.77 (p < .001) and .18 (p < .01), respectively. For class 2, the parent-reported family functioning intercept and slope were −.92 (p < .05) and .02 (p = .62), respectively, and for adolescent-reported family functioning the class 2 intercept and linear slope were −3.33 (p < .001) and −.03 (p = .79), respectively. For parents and adolescents, the intercepts were significantly different from zero in both classes. The slope was significant for adolescents in class 1 (p < .01) and non-significant in class 2 (p = .79). Similarly, for parents, the slope was marginally significant (p = .09) in class 1 and non-significant (p = .62) in class 2. This pattern of results suggests that classes 1 and 2 differed in both their intercepts and slopes. As shown in Figure 3, class 1 was characterized by high parent- and adolescent-reported family functioning and class 2 by low adolescent- and parent-reported family functioning. As such, we named class 1 “High Family Functioning” and class 2 “Low Family Functioning.” For all subsequent analyses, we used the High Family Functioning class as our reference group because we expected this class to score lowest on negative youth and parent outcomes.

Figure 3.

Latent Trajectory Class Solution for Adolescent- and Parent-reported Family Functioning

Step 6. Demographic Variables and Cultural Stress as Predictors of Class Membership

Next, we examined whether class membership differed based on youth age, gender, site, years spent in the U.S., and parent and adolescent cultural stress. As indicated in Table 2, class membership significantly differed by gender and years in the U.S. Specifically, relative to the high family functioning class (52% girls and 48% boys), the low family functioning class contained fewer girls (41%) than boys (59%; OR = .66, p<.05) and had spent more time in the U.S. (MHigh family functioning class = 1.79, SD = 1.53 and MLow family functioning class = 2.37, SD = 2.14; OR = 1.14, p < .05). Additionally, the low family functioning class was characterized by higher adolescent cultural stress (M = .33, SD = 3.01) compared to the high family functioning class (M = .31, SD = 3.37), but this difference was only marginally significant (OR = 1.05, p = .07).

Table 2.

Predictors of Class Membership & Class Membership as Predictor of Adolescent and Parent Outcomes.

| Demographic Variables and Cultural Stress as Predictors of Class Membership | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline Predictors | Odds Ratio | p-value | 95% CI |

| Gender | .66 | .04 | .44, .99 |

| Age | .82 | .17 | .61, 1.09 |

| Site | 1.23 | .45 | .72, 2.08 |

| Years in the U.S. | 1.14 | .04 | 1.00, 1.29 |

| Parent Cultural Stress | 1.03 | .37 | .96, 1.10 |

| Adolescent Cultural Stress | 1.05 | .07 | .98, 1.13 |

| Class Membership as Predictor of Parent and Adolescent Outcomes | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Time 6 Outcomes | Estimate | p-value | 95% CI |

| Self-esteem (A) | −.14 | .064 | −.295, .008 |

| Hope (A) | −.26 | <.001 | −.388, −.134 |

| Rule Breaking (A) | .14 | .002 | .053, .224 |

| Aggressive Behavior (A) | .11 | .029 | .011, .200 |

| Depressive Symptoms (A) | .22 | .003 | .075, .366 |

| Cigarette Smoking (A) | 1.87 | .223 | .683, 5.134 |

| Binge Drinking (A) | 3.84 | .004 | 1.533, 9.632 |

| Marijuana Use (A) | 4.56 | .009 | 1.465, 14.172 |

| Any Anal or Vaginal Sex (A) | 1.61 | .186 | .796, 3.254 |

| Any Oral Sex (A) | 1.31 | .417 | .680, 2.535 |

| Unprotected Vaginal or Anal Sex (A) | 1.83 | .036 | .887, 4.227 |

| Unprotected Oral Sex (A) | 1.94 | .097 | 1.039, 3.204 |

| Depressive Symptoms (P) | .16 | .014 | .033, .292 |

| Cigarette Smoking (P) | 1.09 | .838 | .468, 2.546 |

| Alcohol Use (P) | 1.20 | .503 | .705, 2.040 |

| Drug Use (P) | 0.49 | .243 | .150, 1.617 |

Note:

Class 1 (High Family Functioning) served as reference group. We report standardized regression coefficients for continuous outcome variables and unstandardized odds ratios for categorical outcome variables.

Step 7. Class Membership as Predictor of Parent and Adolescent Outcomes

Next, we predicted T6 parent and adolescent outcomes using class membership, controlling for youth age, gender, site, years in the U.S., and prior levels of continuous outcome variables. As shown in Table 2, as expected, the Low Family Functioning class, compared to the High Family Functioning class reported: (1) lower youth self-esteem (β = −.14, p = .06), (2) lower hope (β = −.21, p < .001), (3) higher youth rule breaking (β = .14, p < .05), (4) higher aggressive behavior (β = .11, p < .05), (5) higher levels of youth depressive symptoms (β = .220, p < .05); (6) greater odds of youth binge drinking (OR = 3.84, p < .05), (7) greater odds of youth marijuana use (OR = 4.56, p < .05), (8) greater odds of unprotected vaginal sex (OR = 1.83, p < .05), and (9) higher levels of parent depressive symptoms (β = .16, p < .05).

Step 8. Invariance by Site: Class Membership as Predictor

Lastly, we sought to explore differences across site in terms of the effect of class membership on parent and adolescent outcomes at T6. Results indicated no significant differences across site; Δχ2(16) = 12.22; p = .729, suggesting that class membership has the same effect on outcomes for parents and adolescents in Miami and LA.

Discussion

Informed by ecodevelopmental theory (Szapocznik & Coatsworth, 1999) and the FSM (Conger et al., 2010), in this study we examined separate longitudinal trajectories of parent- and adolescent-reported family functioning and the effects of these separate family functioning trajectories on adolescent and parent emotional well-being and health risk behaviors. We also investigated the role of parent and adolescent cultural stress in predicting family functioning trajectories and examined whether family functioning trajectories, in turn, predicted adolescent and parent emotional well-being and health risk behaviors Given heterogeneity among Latino families and family functioning, we identified distinct subgroups of parents and adolescents who differed from each other based on their family functioning trajectories (i.e., slopes and intercepts). We also investigated the effects of these empirical family functioning trajectory subgroups on adolescent and parent emotional well-being and health risk behaviors. Lastly, we examined how family functioning subgroups differed by parent and adolescent cultural stress. We now discuss in more detail the key findings and their implications.

We first evaluated the over-time latent structure of two family functioning reports (one separate construct for parents and one for adolescents) to investigate whether the meaning of the latent family functioning structure changed significantly over time. We observed that the structures of these two constructs were consistent over time, suggesting that family functioning, in the form of family cohesion, positive parenting, and parental involvement, carries the same meaning over time and that this meaning does not change as families navigate the U.S. cultural context.

After establishing the temporal stability of the family functioning constructs, we investigated whether the quality of parent- and adolescent-reported family functioning increased or decreased over time. Informed by ecodevelopmental theory and scholarship indicating that positive family functioning may erode as Latino families settle into their U.S. receiving contexts, we hypothesized that adolescent-and parent-reported family functioning would decline over time. Contrary to expectations, our findings indicated that on average, the quality of parent-and adolescent-reported family functioning did not change. However, variability around the slope for parent- and adolescent-reported family functioning suggests that, for some parents and adolescents, family functioning decreased over time, whereas for others it may have increased, and for still others it may have remained the same. These findings suggest heterogeneity in the development of family functioning. We also observed variability in initial levels of parent- and adolescent-reported family functioning, further pointing to differences across families in adolescent- and parent-reported family functioning during the early years following immigration.

Next, informed by the FSM, we investigated (1) the influence of parent and adolescent cultural stressors (i.e., discrimination, a negative context of reception, and acculturative or bicultural stress) on family functioning, and (2) the effect of parent- and adolescent-reported family functioning on adolescent and parent outcomes. Partially supporting our hypothesis that cultural stress would predict lower initial levels of family functioning, adolescent (but not parent) cultural stress predicted worse adolescent- and parent-reported family functioning at baseline (i.e., the intercept). These findings suggest that, although parents’ cultural stress did not predict family functioning, adolescent cultural stress negatively impacted the initial quality of parent- and adolescent-reported family functioning. It is possible that, compared to adolescents, parents have learned to access available resources and assets to actively manage cultural stressors so that these experiences may not negatively affect the well-being of their families. Alternatively, it may be that, compared to their parents, adolescents are more sensitive to cultural stressors such as discrimination, acculturative or bicultural stress, and a negative context of reception because they have had less experience learning how to actively manage stress and because adolescence can be a challenging developmental period, possibly making adolescents more vulnerable to any additional stressors they and their families experience (Coleman, 2011; Falicov, 2013). Alternatively, it may be that adolescents are more exposed to the receiving culture than parents–especially in highly ethnically dense communities (Falicov, 2013). It is also possible that the transition to living in the U.S. is more difficult for adolescents, for whom immigration often occurs involuntarily (Falicov, 2013). The involuntariness of immigration may render adolescents more sensitive and reactive to cultural stressors, thereby impacting family functioning (e.g., Suárez-Orozco, Suárez-Orozco, & Todorova, 2008). Our findings point to the need to employ a developmental lens in research on cultural stress, family functioning, and health, and to investigate the reasons for why adolescent cultural stress appears to impact family functioning more strongly than parent cultural stress does. Such information could help inform the development of interventions to reduce the impact of adolescent cultural stress on family functioning.

Surprisingly, earlier levels of cultural stress did not result in a decline in parent- and adolescent-reported family functioning over time. Instead, cultural stress appeared to have a negative influence on the quality of family functioning early on, after which family functioning remained stable over time. The fact that adolescent- and parent-reported family functioning did not decline for recent immigrant families suggests that families possess strengths and assets that help them successfully navigate cultural stressors. Additionally, these results generally indicate that interventions to foster positive family functioning may be most needed and effective during the early years following immigration, when adolescent cultural stress had the greatest negative impact on parent-and adolescent-reported family functioning. Our findings also indicate that interventions to foster positive family functioning could benefit from identifying resources and assets that recent immigrant families possess and build on these strengths to promote the well-being of adolescents and parents. Moreover, these findings suggest that interventions could benefit from actively addressing adolescents’ cultural stress experiences (Falicov, 2013). Prior research has observed that, for recent immigrant Latino adolescents (Schwartz et al., 2015) and parents (Lorenzo-Blanco et al., 2016 a), cultural stress was highest during the early years of immigration and decreased over time, further supporting the need to make interventions available early on in the settlement process, before adolescent cultural stress impacts the functioning of the family.

Consistent with ecodevelopmental theory and the FSM, we hypothesized that greater positive family functioning at baseline and over time would predict more favorable adolescent and parent outcomes. As expected, we observed that initial levels of positive adolescent-reported family functioning predicted higher levels of adolescent hope and lower levels of adolescent depressive symptoms, whereas initial levels of positive parent-reported family functioning predicted lower odds of adolescent cigarette smoking and binge drinking, lower parent depressive symptoms, and lower odds of parent alcohol use. These findings further suggest that adolescents and parents might benefit from preventive interventions that foster family functioning during the early years following immigration. Moreover, and as expected, positive adolescent-reported family functioning trajectories predicted higher adolescent hope, lower rule breaking, lower odds of cigarette smoking, binge drinking, and marijuana use, and lower odds of parent drug use, whereas parent-reported family functioning trajectories predicted lower odds of unprotected oral sex and lower parent depressive symptoms. These findings suggest that, although families might benefit from intervention efforts during the early years following immigration, interventions may also be beneficial later on. Additionally, our findings indicate that interventions efforts should involve both parents and adolescents because adolescent-reported family functioning influenced some outcomes while parent-reported family functioning predicted other outcomes.

Next, we used latent class growth analysis (LCGA) to identify empirically derived constellations of parent-and adolescent-reported family functioning trajectories. Specifically, we identified two family functioning classes: a “High Family Functioning” and a “Low Family Functioning” class. Adolescents and parents in the “High Family Functioning” class both scored higher on family functioning across time points compared to the “Low Family Functioning” class. Moreover, family functioning scores for adolescents (but not parents) in the “High Family Functioning” class appeared to increase over time, whereas the family functioning scores for both adolescents and parents in their respective “Low Family Functioning” class remained stable over time. These results indicate that adolescents who report high levels of positive family functioning within the first five years of arriving in the U.S. will likely continue to experience increases in positive family functioning, whereas adolescents who report low initial levels of family functioning may likely continue to experience low levels of family functioning over time. This pattern may place youth in the “Low Family Functioning” class at elevated risk for emotional and behavioral health problems compared to adolescents in the “High Family Functioning” class.

Contrary to expectations, family functioning remained stable and did not decline over time. Instead, there appeared to be families who experienced low family functioning early on in the settlement process and for whom family functioning remained low. It is possibly that these families experienced significant stressors prior to or during the immigration process and that these stressors resulted in low family functioning before families arrived in the U.S. (Falicov, 2013). Alternatively, it is possible that these families arrived in the U.S. with high positive family functioning but that family functioning deteriorated early on and families lacked the resources to recover. We did not ask families about their experiences prior or during the immigration process, and future research could benefit from asking families about their stress experience prior to arriving in the U.S. (Falicov, 2013). This information would provide further insights into the development of family functioning and the reasons why family functioning is low for some families and not others, providing valuable information about ways to best promote family functioning among recent immigrant families.

As a next step, we investigated how family functioning classes differed in terms of parent and adolescent cultural stress. Importantly and as expected, compared to the “High” family functioning class, adolescents and parents in the “Low” family functioning class were characterized by higher reports of adolescent (but not parent) cultural stress, further providing support for our variable-centered finding that cultural stress experienced by adolescents may more negatively affect family functioning than might cultural stress experienced by parents. Thus, intervention efforts aimed at improving family functioning for adolescents and parents could benefit from (a) reducing sources of cultural stress for adolescents, (b) helping adolescents develop cultural stress management strategies, or (c) providing parents with the tools to help their adolescents better manage cultural stress. Additionally, schools could offer school-based stress and coping interventions to their recent immigrant Latino students to equip students with effective coping skills to successfully manage cultural stress (Hampel, Meier, & Kummel, 2008).

Lastly, we investigated whether differences would emerge between the two family functioning classes in terms of parent and adolescent outcomes, and we observed some significant differences. Specifically, compared to the “High” family functioning group, the “Low” family functioning group scored higher on parent depressive symptoms and youth rule breaking, aggressive behavior, depressive symptoms, binge drinking, marijuana use, and unprotected oral sex. Additionally, the “Low” family functioning group scored lower on youth optimism compared to the “High” family functioning class, providing further evidence that positive family functioning may indeed promote positive emotional and behavioral health for adolescents and parents. Importantly, these findings corroborate our variable-centered finding that intervention efforts might be most needed during the early years following immigration and might be especially beneficial for families in which adolescents and parents report low family functioning. Moreover, these findings provide additional support that interventions could benefit from fostering family functioning for youth and parents and address adolescent cultural stress.

Limitations

Our findings should be interpreted in light of some important limitations. First, our results may not generalize to all Latino families in the United States. Data were collected in relatively well-established Latino receiving communities with ethnic enclaves that may buffer against cultural stress experiences. As such, our results may not generalize to families who move into new settlement communities (e.g., Deep South, Pacific Northwest) that have less experience interacting with newcomers and where sources of support might not be available (Rodriguez, 2012). Second, we did not measure stressors that might have impacted family functioning prior to families arriving in the U.S., and as such, our findings may not fully represent the stressors experienced by recent immigrant families (Falicov, 2013). Additionally, the majority of adolescents in the present study arrived in the U.S. with their primary caregivers (Schwartz et al., 2014). The results of this study may not generalize to adolescents and parents who come to the U.S. by themselves (Falicov, 2013). Fourth, although, we included adolescent and parent reports of cultural stress, family functioning, and health, not all of the adolescent variables matched the parent variables exactly (e.g., bicultural stress was measured among youth whereas acculturative stress was measured among parents). Future studies should aim at replicating our results using the same variables for adolescents and their parents. Lastly, although we included well-established measures of family functioning, adolescents and parents reported on their perceived family functioning, and future studies may benefit from objective reports of family functioning.

Despite these and other limitations, the present study contributes to our understanding of how family functioning evolves over time to affect the health of recent immigrant adolescents and their parents. Our findings also inform the family and cultural stress literatures by adopting a developmental lens and demonstrating that adolescent cultural stress may impact family functioning more strongly than parent cultural stress does. Importantly, this study indicates that preventive interventions may be most beneficial in the early years following immigration and could benefit from fostering positive family functioning and helping adolescents manage cultural stressors by drawing from the strengths and assets Latino immigrant families already possess. Intervention efforts could specifically target families with poor family functioning in the early years following immigration but all families could benefit from these efforts. Equally important are systematic strategies that combat discrimination against Latino families and improve contexts of reception. All of these efforts would result in improved emotional well-being and behavioral health for adolescents and their parents.

Acknowledgments

Preparation of this article was supported by funding from the National Institutes on Drug Abuse and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (Grant# DA025694) and the National Institute of Health/Fogarty International Center (Grant # 3R01TW009274-04S1).

Contributor Information

Elma I. Lorenzo-Blanco, University of South Carolina

Alan Meca, University of Miami

Brandy Piña-Watson, Texas Tech University

Byron L. Zamboanga, Smith College

José Szapocznik, University of Miami.

Miguel Ángel Cano, Florida International University

David Cordova, University of Michigan

Jennifer B. Unger, University of Southern California

Andrea Romero, University of Arizona

Sabrina E. Des Rosiers, Barry University

Daniel W. Soto, University of Southern California

Juan A. Villamar, Northwestern University

Monica Pattarroyo, University of Southern California.

Karina M. Lizzi, University of Michigan

Seth J. Schwartz, University of Miami

References

- Achenbach TM, & Rescorla LA (2002). Manual for the ASEBA adult forms and profiles. Burlington: Research Center for Children, Youth, and Families, University of Vermont. [Google Scholar]

- Agresti A. (2007). An introduction to categorical data analysis (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Alcántara C, Estevez C, & Alegría M (in press). Latino and Asian immigrant health: Paradoxes and explanations. In Schwartz SJ & Unger JB (Eds.), Oxford handbook of acculturation and health. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bandeen-Roche K, Miglioretti DL, Zeger SL, & Rathouz PJ (1997). Latent variable regression for multiple discrete outcomes. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 92, 1375–1386. doi: 10.2307/2965407 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann AA, Kuhlberg JA, & Zayas LH (2010). Familism, mother-daughter mutuality, and suicide attempts of Latinas. Journal of Family Psychology, 24, 616–624. doi: 10.1037/a0020584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canino G, Vega WA, Sribney WM, Warner LA, & Alegria M (2008). Social relationships, social assimilation, and substance-use disorders among adult Latinos in the U.S. Journal of Drug Issues, 38, 69–101. doi: 10.1177/002204260803800104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cano MA, Schwartz SJ, Castillo LG, Romero AJ, Huang S, Lorenzo-Blanco EI,… & Szapocznik J (2015a). Depressive symptoms and externalizing behaviors among Hispanic immigrant adolescents: Examining longitudinal effects of cultural stress. Journal of Adolescence, 42, 31–39. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2015.03.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cano MA, Schwartz SJ, Castillo LG, Unger JB, Huang S, Zamboanga BL,… & Lizzi KM (2015b). Health risk behaviors and depressive symptoms among Hispanic adolescents: Examining acculturation discrepancies and family functioning. Journal of Family Psychology, 30, 254–265. doi: 10.1037/fam0000142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman JC (2011). The nature of adolescence (4th ed.). New York: Routlege. [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Conger KJ, & Martin MJ (2010). Socioeconomic status, family processes, and individual development. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72, 685–704. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00725.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Córdova D, Schwartz SJ, Unger JB, Baezconde-Garbanati L, Villamar JA, Soto DW,… & Romero AJ (2016). A longitudinal test of the parent–adolescent family functioning discrepancy hypothesis: A trend toward increased HIV risk behaviors among immigrant Hispanic adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 1–14. doi: 10.1007/s10964-016-0500-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimitrov DM (2010). Testing for factorial invariance in the context of construct validation. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 43, 121–149. doi: 10.1177/0748175610373459 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards LM, Ong AD, & Lopez SJ (2007). Hope measurement in Mexican American youth. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 29, 225–241. doi: 10.1177/0739986307299692 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Falicov CJ (2013). Latino families in therapy (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Gassman-Pines A. (2015). Effects of Mexican immigrant parents’ daily workplace discrimination on child behavior and family functioning. Child Development, 4, 1175–1190. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson CL, & Miller HV (2010). Crime and victimization among Hispanic adolescents: A multilevel longitudinal study of acculturation and segmented assimilation. A Final Report for the WEB Du Bois Fellowship Submitted to the National Institute of Justice. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice. [Google Scholar]

- Gorman-Smith D, Tolan PH, Zelli A, & Huesmann LR (1996). The relation of family functioning to violence among inner-city minority youths. Journal of Family Psychology, 10, 115–129.doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.10.2.115 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Glymour MM, Weuve J, Berkman LF, Kawachi I, & Robins JM (2005). When is baseline adjustment useful in analyses of change? An example with education and cognitive change. American Journal of Epidemiology, 162, 267e278. 10.1093/aje/kwi187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampel P, Meier M, & Kummel U (2008). School-based stress management training for adolescents: Longitudinal results from an experimental study. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 37, 1009–1024. doi: 10.1007/s10964-007-9204-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Miech RA, Bachman JG, & Schlenberg JG (2015). Monitoring the future national results on adolescent drug use: Overview of key findings. Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan. [Google Scholar]

- Kann L, Kinchen S, Shanklin SL, Flint KH, Kawkins J, Harris WA, … & Whittle L. (2014). Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States, 2013. Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance — United States, 2013. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report Surveillance Summaries, 63, 1–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauermann G, & Carroll RJ (2001). A note on the efficiency of sandwich covariance matrix estimation. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 96, 1387–1396. doi: 10.1198/016214501753382309 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lindberg LD, Jones R, & Santelli JS (2008). Noncoital sexual activities among adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 43(3), 231–238. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little TD (2013). Longitudinal structural equation modeling. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo-Blanco EI, & Cortina LM (2013). Towards an integrated understanding of Latino/a acculturation, depression, and smoking: A gendered analysis. Journal of Latina/o Psychology, 1, 3–20. 10.1037/a0030951 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo-Blanco EI, Meca A, Unger JB, Romero A, Gonzales-Backen M, Piña-Watson B, … & Schwartz SJ (2016a). Latino parent acculturation stress: Longitudinal effects on family functioning and youth emotional and behavioral health. Journal of Family Psychology, 30, 966 – 976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo-Blanco EI, Meca A, Unger JB, Romero A, Szapocznik J, Piña-Watson B, … & Schwartz SJ (2016b). Longitudinal Effects of Latino Parent Cultural Stress, Depressive Symptoms, and Family Functioning on Youth Emotional Well-Being and Health Risk Behaviors. Family Process, 1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lugo Steidel AG, & Contreras JM (2003). A new familism scale for use with Latino populations. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 25, 312–330. doi: 10.1177/0739986303256912 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén B & Asparouhov T (2002). Using Mplus Monte Carlo simulations in practice: A note on non-normal missing data in latent variable models. Version 2, March 22, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Nagin DS (2005). Group-based modeling of development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nylund K, Asparouhov T, & Muthén B (2007). Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: A Monte Carlo simulation study. Structural Equation Modeling, 14, 535–569. doi: 10.1080/10705510701575396 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez DJ, Fortuna L, & Alegría M (2008). Prevalence and correlates of everyday discrimination among U.S. Latinos. Journal of Community Psychology, 36, 421–433. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS, Madden T, & Santos LJ (1998). Psychological variables as predictors of perceived ethnic discrimination among minority and immigrant adolescents. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 28, 937–953. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.1998.tb01661.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS (1977). The CES-D scale a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1, 385–401. doi: 10.1177/014662167700100306 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez N, Myers HF, Mira CB, Flores T, & Garcia-Hernandez L (2002). Development of the Multidimensional Acculturative Stress Inventory for adults of Mexican origin. Psychological Assessment, 14, 451–461. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.14.4.451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez N. (2012). New Southern Neighbors: Latino immigration and prospects for intergroup relations between African-Americans and Latinos in the South. Latino Studies, 10, 18–40. doi: 10.1057/lst.2012.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Romero AJ, & Roberts R. (2003). Stress within a bicultural context for adolescents of Mexican descent. Cultural Minority and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 9, 171–184. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.9.2.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg M. (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Santisteban DA, Coatsworth JD, Briones E, Kurtines W, & Szapocznik J. (2012). Beyond acculturation: An investigation of the relationship of familism and parenting to behavior problems in Hispanic youth. Family Process, 51, 470–482. Doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2012.01414.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Unger JB, Lorenzo-Blanco EI, Des Rosiers SE, Villamar JA, Soto DW, … & Szapocznik J (2014). Perceived context of reception among recent Hispanic immigrants: Conceptualization, instrument development, and preliminary validation. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 20, 1–14. doi : 10.1037/a0033391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Unger JB, Baezconde-Garbanati L, Zamboanga BL, Lorenzo-Blanco EI, Des Rosiers SE, … & Szapocznik J. (2015). Trajectories of cultural stressors and effects on mental health and substance use among Hispanic immigrant adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 56, 433–439. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt DP, & Allik J. (2005). Simultaneous administration of the Rosenberg self-esteem scale in 53 nations: Exploring the universal and culture-specific features of global self-esteem. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 89, 623–642. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.89.4.623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suárez-Orozco C, Suárez-Orozco MM, & Todorova ILG (2008). Learning a new land. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Szapocznik J, & Coatsworth JD (1999). An ecodevelopmental framework for organizing the influences on drug abuse: A developmental model of risk and protection. In Glantz MD & Hartel CR (Eds.), Drug abuse: Origins and interventions (pp. 331–366). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Todorova IL, Falcón LM, Lincoln AK, & Price LL (2010). Perceived discrimination, psychological distress and health. Sociology of Health and Illness, 32, 843–861. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2010.01257.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolan PH, Gorman-Smith D, Huesmann LR, & Zelli A (1997). Assessment of family relationship characteristics: a measure to explain risk for antisocial behavior and depression among urban youth. Psychological Assessment, 9, 212–223. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.9.3.212 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Torres L, Driscoll MW, & Voell M (2012). Discrimination, acculturation, acculturative stress, and Latino psychological distress: A moderated mediational model. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 18, 17–25. doi: 10.1037/a0026710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner CF, Ku L, Rogers SM, Lindberg LB, Pleck JH, & Sonsenstein LH (1998). Adolescent sexual behavior, drug use, and violence: Increased reporting with computer survey technology. Science, 280, 867–873. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5365.867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau (2014). Hispanic Heritage Month 2014. Facts for Features (CB14-FF.22). Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/newsroom/facts-for-features/2014/cb14-ff22.html [Google Scholar]

- West SG, Taylor AB, Wu W. (2012). Model fit and model selection in structural equation modeling. In: Hoyle RH, ed. Handbook of Structural Equation Modeling (pp. 209–231). New York, NY: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Widaman KF, & Thompson JS (2003). On specifying the null model for incremental fit indices in structural equation modeling. Psychological Methods, 8, 16–37. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.8.1.16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]