Abstract

In this paper, the roles of Epstein‐Barr virus (EBV) in gastric carcinogenesis are discussed, reviewing mainly epidemiological and clinicopathological studies. About 10% of gastric carcinomas harbor clonal EBV. LMP1, an important EBV oncoprotein, is only rarely expressed in EBV‐associated gastric carcinoma (EBV‐GC) while EBV‐encoded small RNA is expressed in almost every EBV‐GC cell, suggesting its importance for developing and maintaining this carcinoma. In addition, the hypermethylation‐driven suppressor gene downregulation, frequently observed in EBV‐GC, appears to give a selective advantage for carcinoma cells. EBV reactivation is suspected to precede EBV‐GC development since antibodies against EBV‐related antigens, including EBV capsid antigen (VCA), are elevated in prediagnostic sera. Interestingly, the average anti‐VCA immunoglobulin G antibody titer in EBV‐GC patients was significantly higher among men than among women, whereas EBV‐negative GC cases did not show such a sex difference. A higher frequency of human leucocyte antigen‐DR11 in EBV‐GCs suggests that major histocompatibility complex‐restricted EBV nuclear antigen 1 epitope recognition may enhance EBV reactivation. EBV infection of gastric cells by lymphocytes with reactivated EBV is suspected to be the first step of EBV‐GC development. Male predominance of EBV‐GC suggests the involvement of lifestyles and occupational factors common among men. The predominance of EBV with XhoI+ and BamHI type i polymorphisms in EBV‐GC in Latin America suggests a possibility of some EBV oncogene expressions being affected by EBV polymorphism. The lack of such predominance in Asian countries, however, indicates an interaction between EBV polymorphism and the host response. In conclusion, further studies are necessary to examine the interaction between EBV infection, its polymorphisms, environmental factors, and genetic backgrounds. (Cancer Sci 2008; 99: 195 –201)

Most individuals turn Epstein‐Barr virus (EBV) seropositive in childhood, mainly through salivary contact, and remain asymptomatic throughout their life. In some developed countries, however, EBV infection is delayed into adolescence and adulthood, particularly, in the upper sections of society.( 1 ) The fate of EBV‐infected cells (lysis or latency) depends on the nature of involved tissue; whereas lytic replication and production of viral particles take place in oropharyngeal epithelial cells, EBV is considered to establish lifelong persistent infection in memory B cells, which exit the cell cycle and persists for life. Occasionally, a small percentage of latently infected B cells may undergo spontaneous replication. The EBV episome in memory B cells does not express any of the known latent proteins of EBV. However, when the latently infected memory cells in the periphery divide, EBV expresses its nuclear antigen 1 (EBNA1),( 2 ) which is essential for retaining the EBV genome by tethering it to cellular DNA and allowing it to be replicated.( 3 ) It is noteworthy that the Gly/Ala repeat domain of EBNA1 prevents proteasome‐dependent processing for presentation on major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I, and makes it elusive to CD8(+) cytotoxic T lymphocytes.( 4 ) Despite this clever strategy, EBNA1 does not fully escape MHC I class presentation and CD8+ T cell detection on EBV‐transformed B cells, particularly in individuals with certain human leucocyte antigen (HLA) haplotypes.( 5 ) Other viral proteins are not expressed to escape from immunosurveilance.( 2 ) Although the EBV episomal replicon is inherited by daughter cells in only 97% of the cell cycles,( 6 ) EBV's loss from proliferating cells is irrelevant to EBV persistence, which is in non‐proliferating and long‐lived memory B cells. An additional role of oropharyngeal epithelium as a site of EBV replication in healthy individuals has been suspected. Although such a role has been regarded controversial, a recent study reported by Shannon‐Lowe et al. has rekindled interest on the role of epithelial cells. They have reported that a newly infected primary B cell with EBV virions retained on the surface serves as a vehicle to transport EBV to epithelial cells, and gets those cells infected with EBV.( 7 )

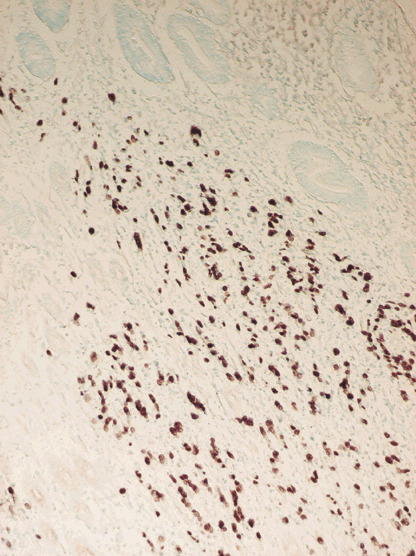

Epstein‐Barr virus has been known for its oncogenic potential, and has been implicated in the etiology of some types of B cell lymphomas, such as Burkitt's lymphoma, and some epithelial malignancies, including undifferentiated nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC),( 1 ) which is characterized by lymphoid stroma. In 1990, using polymerase chain reaction, Burke et al. first reported EBV‐genome detection in lymphoepithelioma‐like carcinoma (LELC), accounting for about 1% of gastric carcinomas.( 8 ) Subsequent studies in the early 1990s revealed that LELCs were almost always EBV‐genome positive, using a new technique, in situ hybridization, to detect the expression of EBV‐encoded small RNAs (EBERs) in tissue specimens.( 9 ) Later, in 1992, EBV involvement in gastric malignancy was found to be not limited to LELC as shown by a study of Shibata and Weiss, who reported the presence of EBER expression in 16% of gastric adenocarcinoma cases in a small North American series.( 10 ) EBV's etiological involvement in gastric carcinogenesis is strongly suspected by the uniform presence of EBER in tumor cells but not in the surrounding normal epithelial cells,( 10 ) as shown in Fig. 1, and the detection of monoclonal EBV episomes by Southern blot hybridization.( 11 ) Note, however, the presence of clonal EBV in every tumor cell merely indicates the presence of EBV prior to the last transformation producing the tumor, as pointed out by Thorley‐Lawson.( 2 ) Additional observations supporting its etiological involvement are elevated antibodies against EBV‐related antigens in prediagnostic sera of EBV‐GC patients,( 12 ) and the unique morphologic features observed in early stage EBV‐GCs.( 13 ) Although EBV is considered to play significant roles in the development of a portion of gastric carcinomas, LMP1, an important EBV oncoprotein, is only rarely expressed in such carcinomas.( 14 ) On the other hand, EBERs are expressed in almost every EBV‐GC cell, suggesting its importance for developing and maintaining the carcinoma. In addition, BARF1 and LMP2A are also suspected to be involved in EBV‐associated gastric carcinogenesis.( 15 ) Taken together, the precise role of EBV in gastric carcinogenesis is still unclear although EBV's etiologic involvement in gastric carcinogenesis is strongly suspected.

Figure 1.

Epstein‐Barr virus (EBV)‐encoded small RNA expression in EBV‐associated gastric carcinoma.

There are three different types of EBV latency (Table 1), which seems important to understand EBV‐related malignancies. The immunologically invisible pool of latently infected memory B cells is believed to be critical for stable maintenance of EBV's persistent infection.( 2 ) However, whether the virus initially infects memory B cells is still disputed. According to the model proposed by Thorley‐Lawson, the first step for establishing persistent EBV infection is its infection of naïve B cells, which become transformed into proliferating lymphoblasts, expressing six nuclear proteins (EBNAs) and three membrane proteins (LMPs) of EBV. This form of latency is called the growth program. An activated B cell blast migrates into the follicle to form a germinal center and differentiates through the germinal center reaction into memory compartment. In the germinal center, EBV latency switches to another transcription program, referred to as the default program, expressing only three of the nine latent proteins, EBNA1, LMP1, and LMP2A. Hodgkin's disease is suspected to arise from an EBV‐infected cell using the default program since they are blocked at the germinal center stage. Burkitt's lymphoma, which is suspected to arise from a germinal center cell entering memory compartment, expresses EBNA1 but not other EBNA proteins or latent membrane proteins.( 2 ) This pattern of EBV latent‐protein expression, called the EBNA1 only program, is similar to EBV‐GCs. Whether this similarity indicates any common roles of EBV in development of the Burkitt's lymphoma and EBV‐GC is of interest.

Table 1.

Latent Epstein‐Barr virus (EBV) infection and related malignancies

| Transcription program | EBNA and LMP expression | Malignancies with similar expression pattern |

|---|---|---|

| Growth | EBNA1,2,3a,3b,3c,LP LPM1, LMP2a, LMP2b | Immunoblastic lymphoma |

| Default | EBNA1, LMP1, LMP2a | Hodgkin's disease |

| Latency | None | |

| EBNA‐1 only | EBNA1 | Burkitt's lymphoma |

| EBV‐GC |

EBNA, EBV nuclear antigen; EBV‐GC, EBV‐associated gastric carcinoma.

In this paper, mainly epidemiologic and clinicopathologic studies on EBV‐GC are reviewed, and the significance of their findings for understanding the roles of EBV in gastric carcinogenesis are discussed.

Demographic features

Age and sex. Most studies showed no evident age dependence of EBV‐GC frequency. However, a study in Mexico showed an evident age‐dependent increase of its frequency.( 16 ) On the other hand a couple of studies showed an age‐dependent decrease of EBV‐GC.( 17 , 18 ) The mechanism involved in the observed age dependence is yet to be elucidated. An interesting feature of EBV‐GC is its male predominance. To our knowledge, no study reported an evident female predominance; almost all of the studies so far showed a male predominance of EBV‐GC.( 10 , 11 , 14 , 19 ) The male predominance suggests the modification of EBV‐GC risk by lifestyles and occupational factors that are common among males. Interestingly, an interview study of Japanese EBV‐GC and EBV‐negative GC patients has shown that frequent salty food intake and wood dust and/or iron filings exposure are related to a higher EBV‐GC risk, suggesting that mechanical injury to the gastric epithelia may be involved in the development of EBV‐GCs.( 20 )

Geographical distribution. Some countries in the American continents such as Chile and the United States have shown a prevalence of EBV‐GCs higher than 15%.( 10 , 21 ) On the other hand, in Mexico and Peru, EBV‐GC was reported to account for only 7% and 4%, respectively.( 16 , 22 ) Similarly, studies in Asian countries have relatively low frequencies of EBV‐GC, ranging from 2% to 10%.( 23 ) In Europe, the regional difference of EBV‐GC prevalence is evident. The highest value of 18% was reported from Germany,( 24 ) and a study in the United Kingdom reported the lowest value, which was 2%.( 23 ) Data from the African continent are limited but the prevalence does not seem to be much higher than any other part of the world.( 15 ) On the basis of observations in several areas with different gastric cancer risk in Japan, it has been suspected that the EBV‐GC prevalence is inversely related to the GC incidence.( 19 ) However, the international data described above do not entirely support such a notion.

Migration. When the frequency of a disease is different in two countries, studies of migrants give important clues regarding the etiology of that disease. A study of Americans with Japanese ancestry, mostly born in Hawaii, reported 10% of 187 gastric cancer cases to be EBV‐associated.( 25 ) The observed percentage of EBV‐GC was intermediate between Japanese (7%),( 19 ) and Caucasians in Los Angeles (16%),( 10 ) suggesting that the frequency of EBV‐GC may be affected by environmental factors. On the other hand, a study of Japanese Brazilians found no increase of EBV‐GC among Japanese immigrants in São Paulo.( 26 ) This finding might be due to the fact that the Japanese‐Brazilian study was not restricted to those born in Brazil, and their socio‐economic status and lifestyles did not change as much as the lifestyles of Japanese Hawaiians. The increase of EBV‐GC among Japanese Hawaiians may be related to EBV infection at older ages in childhood, which usually takes place in developed countries.( 1 )

Birth order. An Iranian study, which detected EBER expression in nine (3%) out of 272 GC cases, showed that six out of nine EBV‐GC cases were born during the period between 1928 and 1930, suggesting the involvement of EBV infection or other events at early childhood in EBV‐GC development.( 27 ) On top of that, a Colombian study showed that the subjects born as the eldest child had a several‐fold lower EBV‐GC risk.( 28 ) It is of note that the eldest children are suspected to be related to older and/or less frequent exposure to infectious agents in early childhood due to the lack of elder siblings.( 1 ) On the other hand, a study in Japan showed an opposite relationship: the subjects born as the eldest or second‐eldest child had about a twofold higher EBV‐GC risk than the other subjects.( 20 ) Since the Japanese and Colombian findings are statistically significant, neither observation can be simply dismissed as a chance finding. Neither of them can be explained by a recall bias either, since interviewees did not know the EBER expression in their gastric carcinomas. A possible explanation may be differences of age at first EBV infection. In the countries where most EBV infection takes place in the early childhood, earlier and/or frequent EBV infection may increase the number of resting memory B cells with latently infected EBV, and as a consequence, increase EBV‐GC risk in adulthood. This may be an explanation for the relatively low EBV‐GC risk among subjects born as the eldest child in Colombia. On the other hand, the observed association of EBV‐GC risk with the highest and second‐highest birth order in the Japanese study is similar to what was reported for Hodgkin's lymphoma in North America and Europe. Its risk has been reported to be associated with higher social classes and small family sizes, which are suspected to be associated with the delay of EBV infection into young adult life.( 1 ) Although it is unlikely that Japanese people reaching cancer‐prone ages in recent years had first EBV infection at ages as late as young adulthood on average, the age at infection in Japan might have been somewhat delayed when compared to underdeveloped countries like Colombia. Therefore, in countries like Japan, where the primary EBV infection may take place in elder childhood, older ages at infection may result in an increased EBV‐GC risk. Unfortunately, the age distributions of EBV infection among Colombian and Japanese GC patients are unknown, and therefore it is difficult to tell whether those hypotheses can explain the observations in Japanese and Colombian studies.

Major clinicopathological and molecular features

Major clinicopathological and molecular features are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Main clinicopathological features of Epstein‐Barr virus‐associated gastric carcinoma (EBV‐GC)

| Male predominance (no study showed female predominance) |

| Predisposition to the non‐antrum of the stomach |

| Evidently low frequencies of intestinal‐phenotype mucins |

| Characteristic morphological feature: |

| Lace pattern in early GC, strong lymphocyte infiltration |

| Aberrant methylation |

Tumor location. Epstein‐Barr virus‐encoded small RNA expression can not be detected in other digestive tract organs, including the colon and esophagus.( 29 ) Those findings indicate the importance of epithelial change(s) and/or condition(s) specific to the stomach. An interesting feature of EBV‐GC is its predominance in the non‐antrum part of the stomach. It is of note that Helicobacter pylori (HP) infection is strongly related to atrophic gastritis frequently starting in the antrum, and HP is more strongly related to cancer of the antrum than more proximally located GCs. However, there appears to be no major interaction or antagonism between EBV‐GC risk and HP‐related GC risk.( 30 ) Note that primary gastric mucosa‐associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma, which is caused by HP infection, does not harbor the EBV genome.( 31 ) Houghton et al. have reported that chronic HP infection induces repopulation of the stomach with bone marrow‐derived cells (BMDCs), which give rise to gastric cancer originated from bone marrow‐derived cells in C57BL/6 mice.( 32 ) It is of interest to examine whether EBV‐GC development is related to BMDCs in gastric epithelia.

Morphology and phenotypic mucin expression. Although EBV‐positive cases are observed in any type of gastric adenocarcinoma, EBV‐GC frequency is slightly more common in moderately differentiated tubular types and poorly differentiated solid‐types than in other types of adenocarcinomas.( 10 , 19 ) EBV‐positive early GCs show a characteristic morphology recognized as ‘lace pattern’ both in intestinal and diffuse‐type GCs, whereas EBV‐negative GCs have, if at all, focal lace‐pattern growth.( 13 ) Analysis of phenotypic mucin expression has shown that EBV‐GCs tend to be the gastric phenotype or the null phenotype, expressing neither intestinal mucins, such as MUC2, nor gastric mucins, such as MUC5AC and MUC6.( 33 , 34 ) Their expressions are downregulated by hypermethylation of their promoters or the promoters of their regulatory proteins. Since phenotypic expression is suspected to change during stages of gastric cancer,( 35 ) it would be of interest to examine whether EBV‐GC has time‐dependent phenotypic expression that is different from EBV‐negative GC.

Lymphocyte infiltration. Another characteristic morphological feature of EBV‐GCs is massive infiltration of CD8‐positive cytotoxic T cells,( 29 , 36 ) indicating that tumor‐specific cytotoxic T‐lymphocyte activity is retained in patients with EBV‐GC. However, cytotoxic T cells do not appear to be able to get rid of the tumor. Even so, we cannot deny the possibility that tumor cells erratically expressing other EBV protein(s) are recognized by infiltrated T lymphocytes and are destroyed by them. In addition to CD8+ T cell infiltration, the average numbers and the grades of the infiltrating natural killer cells, dendritic cells, Ki67‐positive cells were reported to be significantly greater in EBV‐GCs than in EBV‐negative GCs.( 37 ) EBV‐GC is known to be MHC class II positive as well.( 36 ) Examining 110 EBV‐GCs and 155 EBV‐negative GCs, Koriyama et al. reported that HLA‐DR11 was more frequently expressed in EBV‐GCs.( 38 ) Interestingly, EBNA1 was reported to evoke the CD4+ T cell response restricted by HLA‐DR11.( 39 )

Suppressor gene expression. Alterations in signaling pathways mediated by p53 and p16INK4a/Rb are frequently observed in carcinomas of the stomach and other organs. It is reported that nearly all of the EBV‐GCs showed a weak to moderate p53 expression characterized by heterogeneous intensity of staining in a variable proportion of tumor cells, whereas the EBV‐negative GCs showed a bimodal distribution of p53 expression levels, with either homogeneous intense staining of most tumor nuclei, or only very weak expression in a few cells.( 40 ) Although the p53 is the most frequently inactivated suppressor gene in human cancer, there is no convincing evidence indicating that EBV‐GC is associated with p53 mutation. The p16INK4a‐Rb pathway also plays a critical role in preventing inappropriate cell proliferation and is often targeted by viral oncoproteins during immortalization. Recently, Kang et al. reported that the methylation frequency of p16INK4a in the EBV‐GCs was more than three times higher than that in the EBV‐negative GCs.( 41 ) In addition, many other genes suspected to be downregulated through aberrant methylation in malignant cells are more frequently downregulated in EBV‐GC than in EBV‐negative GCs. Although aberrant methylation may be an important mechanism of EBV‐related gastric carcinogenesis, there is no convincing evidence indicating that EBV directly or indirectly causes the aberrant CpG island methylation of the host genome. A possible explanation is that EBV‐GC with extensive hypermethylation is the selected descendent of a cancer or precancer cell with the hypermethylation‐driven downregulation of suppressor genes. Be that as it may, if hypermethylation is involved in maintaining latent EBV infection, inducing hypomethylation may reactivate EBV lytic infection and consequently kill EBV‐infected cancer cells.

Prognosis. Most studies did not show any relationship between EBV presence and GC prognosis. An exception is the study by Koriyama et al.( 42 ) They examined the prognosis of 64 EBV‐GC cases and 128 EBER‐negative gastric cancer cases. EBER expression was related to poor prognosis in intestinal‐type carcinoma, whereas the diffuse‐type EBV‐GC had better prognosis even when lymphoepithelioma‐like carcinomas were excluded. Since recent studies showed that MUC1 and MUC2 expressions are related to poor and better prognosis of gastric cancer, respectively,( 43 ) it is of interest to examine the relative expression of MUC1 and MUC2 expressions in EBV‐GC and their association with prognosis.

How and when EBV infection in gastric epithelia takes place

Serum antibody response. Epstein‐Barr virus‐associated gastric carcinoma is known for elevated antibodies against EBV‐related antigens.( 11 , 12 , 44 ) Levine et al. reported that EBV‐GC patients have significantly high immunoglobulin (Ig) G and IgA antibody titers against EBV capsid antigen (VCA) more than 5 years preceding their diagnoses.( 12 ) A similar study in Japan found IgG antibody against VCA but not IgM antibody.( 44 ) These observations suggest that EBV reactivation, producing lytic viral proteins rather than latent proteins, takes place before gastric carcinoma development. Indeed, reactivation of lytic infection in the tonsils is considered to occur regularly in healthy EBV carriers.( 45 ) Although the role of EBV reactivation in EBV‐GC development is unclear, virion production may have an advantage to get target cells infected. Another possibility is the shift from the protective antiviral Th1 immunity to a more Th2‐polarized EBV‐specific immune response, which may allow the escape of tumor cells from immune surveillance. A similar shift is suspected to take place prior to the development of Hodgkin's disease.( 5 ) An interesting observation made in Shinkura et al.'s study is that average IgG antibody titer against VCA among EBV‐GC patients was significantly higher among men than among women, whereas male EBV‐negative GC cases showed a slightly lower anti‐VCA IgG titer on average than female EBV‐negative cases (1998, unpublished data). Those findings suggest a possible association of EBV reactivation with the male predominance of EBV‐GC. Another interesting observation was made by Charles Rabkin of the National Cancer Institute in the US and his colleagues. They showed that patients with superficial gastritis or chronic atrophic gastritis had several‐fold higher risk of developing dysplasia if they had elevated antibodies against EBNA and EBV VCA.( 46 ) Whether those patients with elevated EBV antibodies are at a higher risk of developing EBV‐GC is yet to be examined. Although studies reported to date indicate an important role of EBV reactivation in the development of EBV‐GC, what is yet unclear is which gastric cells are infected with reactivated EBV. Since EBV cannot be detected in normal gastric epithelia, it is unlikely that EBV infects gastric stem cells. The most likely possibility is that reactivated‐EBV infects precancerous cells.

Precancerous lesions. Shibata and Weiss reported EBER expression in dysplastic epithelium adjacent to a carcinoma.( 10 ) However, zur Hausen et al. examined 11 patients with EBV positive gastric carcinoma of the intact stomach and eight patients with EBV positive gastric stump carcinoma, and reported the absence of EBER transcripts in preneoplastic gastric lesions (intestinal metaplasia or dysplasia). Since EBV infection was observed only in neoplastic gastric cells, they concluded that EBV infection is most likely a late event in gastric carcinogenesis.( 47 ) EBV infection may take place immediately before the last transformation producing the tumor.

Association with other diseases. Yanai et al. reported that EBER was detected in 64% of Crohn's disease and 60% of ulcerative colitis, but not in non‐inflammatory controls and appendicitis cases.( 48 ) In addition, a high prevalence of EBER signals, as high as 20–30%, was shown in gastric remnant cancers in Japan and Korea.( 49 , 50 ) Neither study mentioned sex‐specific distribution of cases. However, when we re‐examined the Japanese data of remnant GCs, male and female remnant cancer cases showed similar EBV‐GC frequencies. Interestingly, the Korean study showed a high prevalence of EBV‐GC only in remnant cancers developed after gastrectomy due to ulcer but not due to cancer. In the remnant cancers among subjects who underwent gastrectomy due to cancer, we cannot deny the possibility that the second cancer is the recurrence of the first one, and that the first and second cancers share clinicopathological features, including EBER expression. Another possibility is that gastric ulcer disease itself may be a strong risk factor of EBV‐GC. Regarding this possibility, an interesting finding was made in Mexico. Herrera‐Goepfert et al. reported a GC case with EBER signals not in cancerous lesions but in regenerative epithelium of ulcerative gastric mucosa adjacent to an EBER‐negative primary adenocarcinoma.( 16 ) This GC case suggests that EBV infection is associated with the regenerative process triggered by certain membrane damage.

EBV entry into gastric epithelial cells. Entry of EBV into B cells is initiated by the attachment of glycoprotein gp350 to the complement receptor type 2, which is CD21. However, CD21 expression is very low or nonexistent in the gastric epithelia, and therefore the entry of EBV into epithelial cells is considered to be mainly through cell‐to‐cell contact between gastric epithelial cells and lymphocytes with EBV.( 51 ) Another possibility is the transfer infection of EBV to CD21‐negative epithelial cells by primary B cells with EBV on their cell surface.( 7 ) It is, however, difficult for those hypotheses to explain the rarity of EBV‐infected gastric dysplasia cells. On the basis of the following observations, we suspect that gastric EBV infection is related to stomach mucosal damage: (i) EBV‐GC patients had more frequent exposures to wood dust and metal dust exposure;( 19 ) (ii) a high prevalence of EBER signals, as high as 20–30%, was shown in gastric remnant cancers;( 49 , 50 ) and (iii) EBER signals were observed in an ulcerous region but not in adjacent carcinoma lesion in a Mexican case.( 15 ) Membrane damage and subsequent regeneration of gastric membrane may induce EBV infection of the gastric membrane. An extremely high prevalence of EBER expression in Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis reported by Yanai et al.( 48 ) also supports the notion. Although highly speculative, a possibility is that gastric EBV infection may take place through lymphocytes with EBV, recruited to the damaged membrane or the regenerative gastric mucosa.

Is EBV detected in GC different from healthy controls?

Epstein‐Barr virus genotype detected in GC was considered to be the same as those found in healthy subjects. Recently, however, Corvalan et al. showed that EBV detected in GCs had a distinctive viral genotype, characterized as type ‘i’ at the BamHI W1/I1 boundary region and XhoI+ at the XhoI restriction site polymorphism in exon 1 of the LMP1 gene.( 52 ) On the other hand, among healthy adults, these polymorphisms were as common as the other three genotypes (type I/XhoI – and the recombinants type ‘i’/XhoI – and type I/XhoI+). In addition, although based on a small subset of cases, most EBV‐GC cases harbored the same strain in both stomach and throat washings. These case‐control differences suggest that a particular polymorphism (type ‘i’/XhoI+) is predominant in EBV‐GC.

The finding of a distinctive genotype in EBV‐GC cases in comparison with healthy donors suggests the expression of particular EBV gene(s) with transforming capacity might be encoded in the vicinity of BamHI W1/I1 boundary and XhoI restriction site polymorphism. However, the XhoI restriction site is located in exon 1 of the LMP1 gene, which is only occasionally expressed, if at all, in EBV‐GC.( 14 ) Among several genes that may be related to those polymorphisms, the most likely candidate is LMP2A, since the XhoI restriction site is located in the intron between exons 1 and 2 of this gene. Interestingly, Tanaka et al. compared EBV‐GC and healthy donors and found that strains detected in EBV‐GC tended to have LMP2A gene with threonin substitution at codon 348, which corresponds to HLA A‐11 restricted cytotoxic T lymphocytes epitope.( 53 )

Genetic backgrounds and EBV‐GC risk

The balance between the virulence of EBV and the host reaction, including cytokine production, is important when we consider the interrelationships among infective organisms, chronic inflammation and carcinogenesis. Single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) of cytokine genes is of interest since SNP may alter certain cytokine production. Indeed, the frequency of interleukin‐10 and tumor necrosis factor‐α SNPs has been reported to show differences between EBV‐GCs and EBV‐negative GCs.( 54 ) In addition, EBV‐GC is known to downregulate many host genes by its promoter hypermethylation. Interestingly, Kusano et al. reported that EBV‐associated tumors were associated strongly with high CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP).( 55 ) Further studies seem warranted to examine the association of EBV‐GC risk with genetic backgrounds.

Conclusion

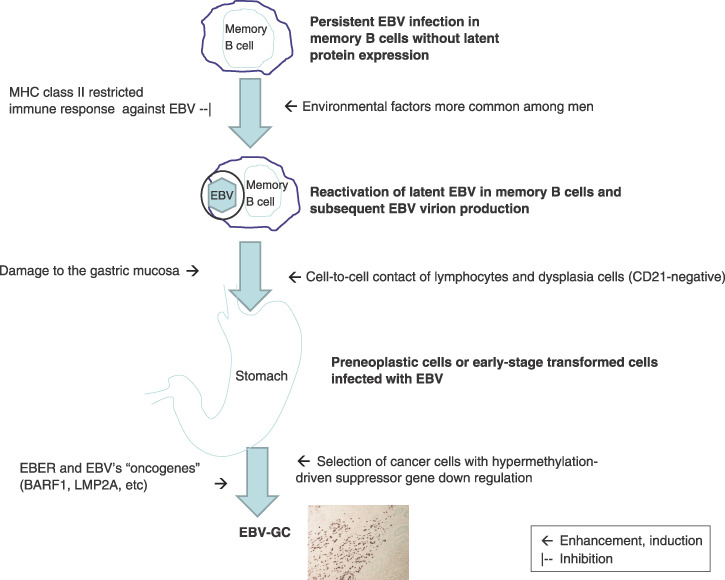

In summary, our current understanding of EBV‐related gastric carcinogenesis is, although speculative, as follows (Fig. 2). Elevated antibodies against EBV‐related antigens in prediagnostic sera of EBV‐GC patients indicate that EBV reactivation in B cells precedes EBV‐GC development. Viral particles produced by EBV reactivation may have an advantage to get target cells infected. Higher VCA antibodies in male EBV‐GC patients than in female EBV‐GC cases suggest the involvement of a sex‐related factor in EBV reactivation. In addition, the decreased expression of HLA‐DR11 in EBV‐GCs suggests that MHC class II restricted EBNA1 epitope recognition may decrease the frequency of EBV reactivation. Male predominance of EBV‐GC suggests the involvement of lifestyles and occupational factors more common among men. The association of EBV‐GC risk with factors related to the stomach mucosal damage suggests such damage to the mucosa and subsequent regeneration of the gastric mucosa may induce EBV infection of the gastric epithelia. The lack of sex difference in the frequency of EBV‐GC in stump tumors suggests that the frequency of EBV infection of the damaged stomach mucosa may not be different in two sexes. EBV Infection of gastric dysplasia cells by lymphocytes with reactivated EBV is suspected to be the first step of EBV‐GC development. The mechanism involved in the relatively high frequency of EBV‐GC in the non‐antrum part of the stomach or oxyntic mucosa is yet to be elucidated.

Figure 2.

The development of Epstein‐Barr virus (EBV)‐associated gastric carcinoma (EBV‐GC). EBER, EBV‐encoded small RNAs; MHC, major histocompatibility complex.

LMP1, an important oncoprotein of EBV, is only rarely expressed in EBV‐GC while EBERs are expressed in almost every EBV‐GC cell, suggesting its importance for developing and maintaining this carcinoma. BARF1 and LMP2A are also suspected to be involved in EBV‐associated gastric carcinogenesis.( 15 ) EBV‐GC is known to downregulate many host genes by its promoter hypermethylation, suggesting that such a cell with latent EBV infection is more likely to develop into a carcinoma. The mechanism involved in aberrant CpG island methylation of host genome in EBV‐GC is yet to be elucidated.

The predominance of EBV with XhoI+ and BamHI type ‘i’ polymorphisms in EBV‐GC in Latin America suggests a possibility of some EBV oncogene expressions being affected by EBV polymorphisms. However, the lack of such predominance in Asian countries indicates the presence of interaction between EBV polymorphism and the host response. Regional differences of EBV‐GC prevalence also suggest that EBV‐GC development is related to environmental factors, genetic backgrounds and geographic distributions of EBV with different polymorphism.

Acknowledgments

The authors were supported by Grants‐in‐Aid for Scientific Research on Priority Areas of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan (12218231 and 1701503). We appreciate insightful comments made by Alejandro Corvalan of the Department of Pathology, Catholic University of Chile, Santiago, Chile Kim Woo Ho of Seoul National University Medical School, and the anonymous reviewer of Cancer Science.

References

- 1. Mueller N, Birmann B, Parsonnet J, Schiffman M, Stuver S. Infectious agents. In: Schottenfeld D, Fraumeni JF, eds. Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention, 3rd edn. New York: Oxford University Press, 2006; 507–49. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Thorley‐Lawson EBV. Persistence and latent infection in vivo . In: Robertson ES, ed. Epstein‐Barr Virus. Norfolk: Caister Academic Press, 2005: 309–58. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Yates JL, Warren N, Sugden B. Stable replication of plasmids derived from Epstein‐Barr virus in various mammalian cells. Nature 1985; 313: 812–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Levitskaya J, Coram M, Levitsky V et al . Inhibition of antigen processing by the internal repeat region of the Epstein‐Barr virus nuclear antigen‐1. Nature 1995; 375: 685–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Munz C. Immune response and evasion in the host–EBV interaction. In: Robertson ES, ed. Epstein‐Barr Virus. Norfolk: Caister Academic Press, 2005; 197–231. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kirchmaier AL, Sugden B. Plasmid maintenance of derivatives of oriP of Epstein‐Barr virus. J Virol 1995; 69: 1280–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Shannon‐Lowe CD, Neuhierl B, Baldwin G, Rickinson AB, Delecluse HJ. Resting B cells as a transfer vehicle for Epstein‐Barr virus infection of epithelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2006; 103: 7065–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Burke AP, Yen TS, Shekitka KM, Sobin LH. Lymphoepithelial carcinoma of the stomach with Epstein‐Barr virus demonstrated by polymerase chain reaction. Mod Pathol 1990; 3: 377–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Shibata D, Tokunaga M, Uemura Y, Sato E, Tanaka S, Weiss LM. Association of Epstein‐Barr virus with undifferentiated gastric carcinomas with intense lymphoid infiltration. Lymphoepithelioma‐like carcinoma. Am J Pathol 1991; 139: 469–74. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Shibata D, Weiss LM. Epstein‐Barr virus‐associated gastric adenocarcinoma. Am J Pathol 1992; 140: 769–74. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Imai S, Koizumi S, Sugiura M et al . Gastric carcinoma: monoclonal epithelial malignant cells expressing Epstein‐Barr virus latent infection protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1994; 91: 9131–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Levine PH, Stemmermann G, Lennette ET, Hildesheim A, Shibata D, Nomura A. Elevated antibody titers to Epstein‐Barr virus prior to the diagnosis of Epstein‐Barr‐virus‐associated gastric adenocarcinoma. Int J Cancer 1995; 60: 642–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Uemura Y, Tokunaga M, Arikawa J et al . A unique morphology of Epstein‐Barr virus‐related early gastric carcinoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 1994; 3: 607–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gulley ML, Pulitzer DR, Eagan PA, Schneider BG. Epstein‐Barr virus infection is an early event in gastric carcinogenesis and is independent of bcl‐2 expression and p53 accumulation. Hum Pathol 1996; 27: 20–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Iwakiri D, Takada K. Epstein‐Barr virus and gastric cancer. In: Robertson ES, ed. Epstein‐Barr Virus. Norfolk: Caister Academic Press, 2005; 157–69. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Herrera‐Goepfert R, Akiba S, Koriyama C et al . Epstein‐Barr virus‐associated gastric carcinoma: evidence of age‐dependence among a Mexican population. World J Gastroenterol 2005; 11: 6096–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chang MS, Lee HS, Kim HS et al . Epstein‐Barr virus and microsatellite instability in gastric carcinogenesis. J Pathol 2003; 199: 447–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Van Beek J, Zur Hausen A, Klein Kranenbarg E et al . EBV‐positive gastric adenocarcinomas: a distinct clinicopathologic entity with a low frequency of lymph node involvement. J Clin Oncol 2004; 22: 664–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tokunaga M, Uemura Y, Tokudome T et al . Epstein‐Barr virus related gastric cancer in Japan: a molecular patho‐epidemiological study. Acta Pathol Jpn 1993; 43: 574–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Koriyama C, Akiba S, Minakami Y, Eizuru Y. Environmental factors related to Epstein‐Barr virus‐associated gastric cancer in Japan. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2005; 24: 547–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Corvalan A, Koriyama C, Akiba S et al . Epstein‐Barr virus in gastric carcinoma is associated with location in the cardia and with a diffuse histology: a study in one area of Chile. Int J Cancer 2001; 94: 527–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Yoshiwara E, Koriyama C, Akiba S et al . Epstein‐Barr virus‐associated gastric carcinoma in Lima, Peru. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2005; 24: 49–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Burgess DE, Woodman CB, Flavell KJ et al . Low prevalence of Epstein‐Barr virus in incident gastric adenocarcinomas from the United Kingdom. Br J Cancer 2002; 86: 702–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Van Beek J, Zur Hausen A, Klein Kranenbarg E et al . EBV‐positive gastric adenocarcinomas: a distinct clinicopathologic entity with a low frequency of lymph node involvement. J Clin Oncol 2004; 22: 664–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Shibata D, Hawes D, Stemmermann GN, Weiss LM. Epstein‐Barr virus‐associated gastric adenocarcinoma among Japanese Americans in Hawaii. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 1993; 2: 213–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Koriyama C, Akiba S, Iriya K et al . Epstein‐Barr virus‐associated gastric carcinoma in Japanese Brazilians and non‐Japanese Brazilians in Sao Paulo. Jpn J Cancer Res 2001; 92: 911–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Abdirad A, Ghaderi‐Sohi S, Shuyama K et al . Epstein‐Barr virus associated gastric carcinoma: a report from Iran in the last four decades. Diagn Pathol 2007; 2: 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Campos FI, Koriyama C, Akiba S et al . Environmental factors related to gastric cancer associated with Epstein‐Barr virus in Colombia. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2006; 7: 633–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kijima Y, Hokita S, Takao S et al . Epstein‐Barr virus involvement is mainly restricted to lymphoepithelial type of gastric carcinoma among various epithelial neoplasms. J Med Virol 2001; 64: 513–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Arikawa J, Tokunaga M, Satoh E, Tanaka S, Land CE. Morphological characteristics of Epstein‐Barr virus‐related early gastric carcinoma: a case‐control study. Pathol Int 1997; 47: 360–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ott G, Kirchner T, Seidl S, Muller‐Hermelink HK. Primary gastric lymphoma is rarely associated with Epstein‐Barr virus. Virchows Arch B Cell Pathol Incl Mol Pathol 1993; 64: 287–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Houghton J, Stoicov C, Nomura S et al . Gastric cancer originating from bone marrow‐derived cells. Science 2004; 306: 1568–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lee HS, Chang MS, Yang HK, Lee BL, Kim WH. Epstein‐barr virus‐positive gastric carcinoma has a distinct protein expression profile in comparison with Epstein‐Barr virus‐negative carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 2004; 10: 1698–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hirano N, Tsukamoto T, Mizoshita T et al . Down regulation of gastric and intestinal phenotypic expression in Epstein‐Barr virus‐associated stomach cancers. Histol Histopathol 2007; 22: 641–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tatematsu M, Tsukamoto T, Inada K. Stem cells and gastric cancer – role of gastric and intestinal mixed intestinal metaplasia. Cancer Sci 2003; 94: 135–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Saiki Y, Ohtani H, Naito Y, Miyazawa M, Nagura H. Immunophenotypic characterization of Epstein‐Barr virus‐associated gastric carcinoma: massive infiltration by proliferating CD8+ T‐lymphocytes. Lab Invest 1996; 75: 67–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kijima Y, Ishigami S, Hokita S et al . The comparison of the survivals between Epstein‐Barr virus (EBV)‐positive gastric carcinomas and EBV‐negative ones cancer letter. 2003; 200: 33–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Koriyama C, Shinkura R, Hamasaki Y, Fujiyoshi T, Eizuru Y, Tokunaga M. Human leukocyte antigens related to Epstein‐Barr virus‐associated gastric carcinoma in Japanese patients. Eur J Cancer Prev 2001; 10: 69–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Leen A, Meij P, Redchenko I et al . Differential immunogenicity of Epstein‐Barr virus latent‐cycle proteins for human CD4 (+) T‐helper 1 responses. J Virol 2001; 75: 8649–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Leung SY, Chau KY, Yuen ST, Chu KM, Branicki FJ, Chung LP. p53 overexpression is different in Epstein‐Barr virus‐associated and Epstein‐Barr virus‐negative carcinoma. Histopathology 1998; 33: 311–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kang GH, Lee S, Kim WH et al . Epstein‐barr virus‐positive gastric carcinoma demonstrates frequent aberrant methylation of multiple genes and constitutes CpG island methylator phenotype‐positive gastric carcinoma. Am J Pathol 2002; 160: 787–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Koriyama C, Akiba S, Itoh T et al . Prognostic significance of EBV involvement in gastric carcinoma in Japan. Int J Mol Med 2002; 10: 635–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Utsunomiya T, Yonezawa S, Sakamoto H et al . Expression of MUC1 and MUC2 mucins in gastric carcinomas: its relationship with the prognosis of the patients. Clin Cancer Res 1998; 4: 2605–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Shinkura R, Yamamoto N, Koriyama C, Shinmura Y, Eizuru Y, Tokunaga M. Epstein‐Barr virus‐specific antibodies in Epstein‐Barr virus‐positive and ‐negative gastric carcinoma cases in Japan. J Med Virol 2000; 60: 411–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Babcock GJ, Decker LL, Volk M, Thorley‐Lawson DA. EBV persistence in memory B cells in vivo . Immunity 1998; 9: 395–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Rabkin C, You WC, Lennette ET, Gail MT, Schetter AJ. Association of Epstein‐Barr virus antibody levels with precancerous gastric lesions in a high risk cohort. In: American Association for Cancer Research Annual Meeting: Proceedings; 2007 April 14–18; Los Angeles, CA. Philadelphia (PA): AACR, 2007. Abstract 1748. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Zur Hausen A, Van Rees BP, Van Beek J et al . Epstein‐Barr virus in gastric carcinomas and gastric stump carcinomas: a late event in gastric carcinogenesis. J Clin Pathol 2004; 57: 487–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Yanai H, Shimizu N, Nagasaki S, Mitani N, Okita K. Epstein‐Barr virus infection of the colon with inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol 1999; 94: 1582–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Yamamoto N, Tokunaga M, Uemura Y et al . Epstein‐Barr virus and gastric remnant cancer. Cancer, 1994; 74: 805–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Chang MS, Lee JH, Kim JP et al . Microsatellite instability and Epstein‐Barr virus infection in gastric remnant cancers. Pathol Int, 2000; 50: 486–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Imai S, Nishikawa J, Takada K. Cell‐to‐cell contact as an efficient mode of Epstein‐Barr virus infection of diverse human epithelial cells. J Virol 1998; 72: 4371–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Corvalan A, Ding S, Koriyama C et al . Association of a distinctive strain of Epstein‐Barr virus with gastric cancer. Int J Cancer 2006; 118: 1736–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Tanaka M, Kawaguchi Y, Yokofujita J, Takagi M, Eishi Y, Hirai K. Sequence variations of Epstein‐Barr virus LMP2A gene in gastric carcinoma in Japan. Virus Genes 1999; 19: 103–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Wu MS, Huang SP, Chang YT et al . Tumor necrosis factor‐alpha and interleukin‐10 promoter polymorphisms in Epstein‐Barr virus‐associated gastric carcinoma. J Infect Dis 2002; 185: 106–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Kusano M, Toyota M, Suzuki H et al . Genetic, epigenetic, and clinicopathologic features of gastric carcinomas with the CpG island methylator phenotype and an association with Epstein‐Barr virus. Cancer 2006; 106: 1467–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]