Abstract

The ATP‐binding cassette (ABC) transporters (ABC‐T) actively efflux structurally and mechanistically unrelated anticancer drugs from cells. As a consequence, they can confer multidrug resistance (MDR) to cancer cells. ABC‐T are also reported to be phenotypic markers and functional regulators of cancer stem/initiating cells (CSC) and believed to be associated with tumor initiation, progression, and relapse. Dofequidar fumarate, an orally active quinoline compound, has been reported to overcome MDR by inhibiting ABCB1/P‐gp, ABCC1/MDR‐associated protein 1, or both. Phase III clinical trials suggested that dofequidar had efficacy in patients who had not received prior therapy. Here we show that dofequidar inhibits the efflux of chemotherapeutic drugs and increases the sensitivity to anticancer drugs in CSC‐like side population (SP) cells isolated from various cancer cell lines. Dofequidar treatment greatly reduced the cell number in the SP fraction. Estimation of ABC‐T expression revealed that ABCG2/breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP) mRNA level, but not the ABCB1/P‐gp or ABCC1/MDR‐associated protein 1 mRNA level, in all the tested SP cells was higher than that in non‐SP cells. The in vitro vesicle transporter assay clarified that dofequidar had the ability to suppress ABCG2/BCRP function. Dofequidar treatment sensitized SP cells to anticancer agents in vitro. We compared the antitumor efficacy of irinotecan (CPT‐11) alone with that of CPT‐11 plus dofequidar in xenografted SP cells. Although xenografted SP tumors showed resistance to CPT‐11, treatment with CPT‐11 plus dofequidar greatly reduced the SP‐derived tumor growth in vivo. Our results suggest the possibility of selective eradication of CSC by inhibiting ABCG2/BCRP. (Cancer Sci 2009)

Although conventional chemotherapy kills most tumor cells, it is believed to leave some cells behind, which might be the source of recurrence. The cells that tend to remain are thought to be cancer stem cells (CSC).( 1 ) CSC are likely to share many properties of normal stem cells, such as a resistance to drugs and toxins through the expression of several ATP‐binding cassette (ABC) transporters (ABC‐T). Therefore, tumors might have a built‐in population of drug‐resistant pluripotent cells that can survive after chemotherapy and can repopulate the tumor.

The drug‐transporting properties of some ABC‐T are important markers for isolation and analysis of stem cells. Most differentiated cells accumulate the fluorescent dye Hoechst33342, but stem cells cannot accumulate the dye because of its active efflux via ABC‐T. Thus, stem cells can be concentrated by collecting a population that contains only a low level of Hoechst33342 fluorescence.( 2 , 3 ) These cells are referred to as side population (SP) cells. A large fraction of hematopoietic stem cells are found in the SP fraction.( 4 ) SP cells can be isolated from many normal tissues,( 3 , 5 , 6 ) which were enriched in lineage‐specific stem cell. SP cells can be also identified in some neuroblastoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, gastrointestinal cancer, and glioblastoma cells, and in several cell lines that have been maintained in culture over long periods of time.( 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 )

By inhibiting the major transporters, tumor elimination could be achieved by reversing drug resistance. Therefore, many efforts have been devoted to developing inhibitors against ABC‐T. Since the discovery of verapamil as a multidrug resistance (MDR)‐reversing agent,( 11 ) many compounds have been investigated as MDR inhibitors.( 12 ) Most of the compounds, however, do not exhibit positive results in animal studies because of their dose‐limiting toxicity.( 12 )

We previously reported a series of quinoline derivatives that show MDR‐reversing activities in K562 cells that are resistant to doxorubicin (K562/ADM).( 13 ) K562/ADM is a human leukemia cell line that endogenously overexpresses ABCB1/P‐gp. Among these derivatives, dofequidar fumarate (dofequidar) was identified as a novel, orally active, quinoline‐derivative inhibitor of ABCB1/P‐gp. In preclinical studies, dofequidar reversed MDR in ABCB1/P‐gp‐expressing and ABCC1/MDR‐associated protein (MRP) 1‐expressing cancer cells in vitro. In addition, oral administration of dofequidar enhanced the antitumor activity of doxorubicin (ADM), vincristine, and docetaxel in vivo. ( 14 , 15 , 16 ) Thus, dofequidar is a promising MDR‐reversing agent. The results of phase III clinical evaluations of dofequidar for breast cancer patients showed a relative improvement and absolute increase in response rate for patients who received dofequidar plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and fluorouracil (CAF), but the findings did not reach statistical significance. However, subgroup analysis suggested that dofequidar plus CAF therapy displayed significantly improved, progression‐free survival and overall survival in patients who had not received prior therapy.( 17 )

Irinotecan (CPT‐11) is one of the most widely prescribed drugs for many cancers.( 18 ) It is reported that CPT‐11 is exported from the cells by ABCB1/P‐gp and ABCC1/MRP1.( 19 , 20 ) In addition, SN‐38, the active metabolite of prodrug CPT‐11, is exported from the cells by ABCG2/breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP),( 21 ) and the therapeutic efficacy of CPT‐11 is strongly correlated with BCRP expression. Therefore, in the present study, we tried to evaluate the antitumor activity of dofequidar combined with CPT‐11.

In the present study, we found that SP cells from various cancer cell lines exhibited MDR properties. Treatment of SP cells with dofequidar reversed the MDR phenotype by inhibiting ABCG2/BCRP. Dofequidar also reversed the drug resistance of xenografted SP cells in vivo. These results suggest that dofequidar may show clinical efficacy and may improve progression‐free survival by inhibiting ABCG2/BCRP that is overexpressed specifically in CSC.

Material and Methods

Reagents and cell culture conditions. Fumitremorgin C (FTC) and reserpine were purchased from Alexis Corp. (Lausen, Switzerland) and Daiichi Pharmaceutical (Tokyo, Japan), respectively. Mitoxantrone (MXR) and methotrexate (MTX) were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA) and Biomol International L.P. (Exeter, UK), respectively. Dofequidar and CPT‐11 were kindly provided by Bayer Schering Pharma (Osaka, Japan) and Yakult Honsha Co. (Tokyo, Japan), respectively. Human cervix carcinoma HeLa cells, human epidermoid carcinoma KB‐3‐1 cells, and the stable transfectants of KB‐3‐1 cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS (DMEM growth medium). Human chronic myeloid leukemia K562 and the stable transfectants, human breast cancer BSY‐1, HBC‐4, and HBC‐5, human glioma U251, human pancreatic cancer Capan‐1, human colon cancer KM12, and human stomach cancer MKN74 were cultured in RPMI‐1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS. To assess the cell viability, cells were incubated with 3‐(4,5‐dimethylthiazol‐2‐yl)‐5‐(3‐carboxymethoxyphenyl)‐2‐(4‐sulfophenyl)‐2H‐tetrazolium (MTS) (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) for 1 h and the optical density was measured using a microplate spectrophotometer (Benchmark‐Plus; Bio‐Rad, Richmond, CA, USA).

Analysis and SP cell sorting from various cancer cell lines using FACS Vantage. Cells were trypsinized and resuspended in ice‐cold HBSS supplemented with 2% FBS at a concentration of 1 × 106 cells/mL. For SP analysis, cells were treated with 2.5–15 μg/mL Hoechst33342 dye (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) for 60 min at 37°C with or without ABC‐T inhibitors (reserpine, FTC, or dofequidar). After washing with PBS, 3 × 104 cells were analyzed using a FACS Vantage SE flow cytometer (BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA, USA). Analysis was done using Flow Jo software (Treestar, San Carlos, CA, USA).

RNA preparation and real‐time PCR. Total RNA from HeLa SP and non‐SP (NSP) cells were extracted using an RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hiden, Germany). RNA (1 μg) was reverse transcribed using SuperScript III (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Then, the amount of ABCG2, ABCB1, and ABCC1 mRNA was quantified with TaqMan probes using a PCR LightCycler 480 (Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland) and normalized to the amount of GAPDH mRNA. The sequences of the primers for ABC‐T are described in Table S1.

In vivo tumorigenicity and treatment. Sorted HeLa SP and NSP cells were collected and resuspended in DMEM growth medium at concentrations ranging from 100 to 10 000 cells/30 μL. Cells were then mixed with 30 μL of Matrigel (BD Bioscience). This cell–Matrigel suspension was injected s.c. into 5‐ to 6‐week‐old female BALB/c‐nu/nu (nude) mice (Charles River Laboratories, Yokohama, Japan). The mice were checked twice weekly for palpable tumor formation. The mice were then euthanized and tumors were resected and diced. A piece of tumor was sequentially injected s.c. into another 5‐ to 6‐week‐old female BALB/c nude mouse. Tumor size was measured every second day with a caliper, and tumor volumes were defined as (longest diameter) × (shortest diameter)/2.( 2 ) When tumor size was approximately 100 mm3, mice were sorted into four equal groups. Then, the nude mice were administered orally with dofequidar (200 mg/kg) or water as a control, 30 min before intravenous administration of CPT‐11 (67 mg/kg) on days 0, 4, and 8. Bodyweight and tumor size were measured every 3 days. All animal procedures were carried out using protocols approved by the Japanese Foundation for Cancer Research Animal Care and Use Committee.

Transfection and immunoblotting. Negative control siRNA (medium GC duplex), ABCG2‐1 siRNA, and ABCG2‐2 siRNA were purchased from Invitrogen (Table S1). HeLa cells were transfected with various siRNA with LipofectAMINE 2000 reagent (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After 24 h of incubation, cells were harvested, and the expression of ABCG2/BCRP and the cell number in the SP fraction was analyzed. For immunofluorescent staining, cells were incubated in blocking buffer (5 mg/mL of BSA and 2 mM EDTA in PBS) for 15 min. Then, 0.5 μg of biotin‐conjugated anti‐ABCG2/BCRP antibody (5D3; eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA) was added. After incubation for 30 min, cells were washed and incubated with 0.1 μg of streptavidin–phycoerythrin (PE) (BD Bioscience). After washing, cells were analyzed by flow cytometry. For immunoblotting, cells were lysed in SDS sample buffer (0.1 M Tris‐HCl at pH 8.0, 10% glycerol, and 1% SDS) with sonication and cleared by centrifugation at 17 400g for 10 min. Samples were electrophoresed and immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies: ABCG2/BCRP polyclonal antibody,( 22 ) MDR1 antibody (JSB‐1; Monosan, Uden, the Netherlands), MRP1 antibody (MRPm6, Monosan), and tubulin alpha antibody (YL1/2; Serotec, Oxford, UK).

In vitro vesicle transport assay. We assayed 3H‐labeled MTX ([3H]MTX) transport using lipid vesicles containing ABCG2/BCRP protein (Genomembrane, Yokohama, Japan), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. [3H]MTX was purchased from Moravek (Brea, CA, USA) (#MT701). The transport reaction (50 mM MOPS‐Tris [pH 7.0], 7.5 mM MgCl2, 70 mM KCl, 160 μM cold MTX, with various inhibitors [dofequidar, FTC, or verapamil], 1 mCi/mL [3H]MTX, and membrane vesicles [25 μg protein]) in a 30‐μL mixture was kept on ice for 5 min. Then, 20 μL of 10 mM ATP or AMP was added into reaction mixtures and incubated at 37°C for 5 min. The reaction was terminated by adding an ice‐cold stop solution (40 mM MOPS‐Tris [pH 7.0] and 70 mM KCl). The membrane vesicles were trapped on a TOPCOUNT plate filter and washed with ice‐cold stop solution. The radioactivity was measured with a liquid scintillation counter (Topcount; Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA).

Intracellular drug accumulation. The effect of dofequidar on the intracellular accumulation of MXR was determined by flow cytometry. K562 or K562/BCRP cells (5 × 105 cells) were incubated with 3 μM MXR for 30 min at 37°C with or without dofequidar or FTC, washed in ice‐cold PBS, and then subjected to fluorescence analysis using a Cytomics FC500 (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA, USA) with 630 nm excitation.

Statistical analysis. All data are shown as means ± SD. Student’s t‐test was carried out. P‐values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical tests were two sided.

Results

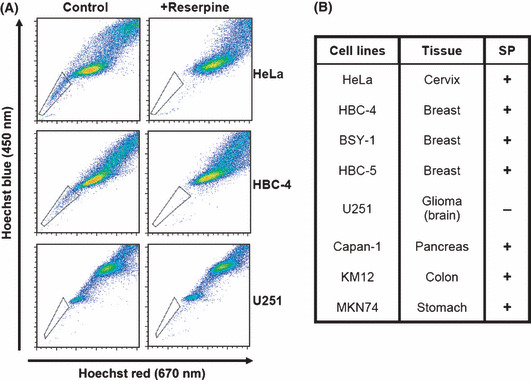

Identification and characterization of SP cells. Staining the cells with Hoechst33342 dye followed by flow cytometric analysis revealed the presence of a very small unstained population (i.e. the SP) of cells in primary tumors and several cell lines. SP cells are known to show cancer stem cell‐like properties, such as high tumorigenicity and repopulating ability. To study the characteristics of SP cells and to develop new strategies targeting cancer stem cells, we first investigated the presence of SP cells in established human cancer cell lines. Consistent with a previous report,( 10 ) the human cervical cancer HeLa cell line contained SP cells at approximately 0.5–1% of the total (Fig. 1A, left panels). The number of cells in the SP fraction derived from HeLa and HBC‐4 cells was drastically reduced by adding the ABC‐T inhibitor reserpine (Fig. 1A, right panels). Because reserpine treatment did not affect the fluorescence patterns of Hoechst33342‐stained U251 glioma cells, we concluded that U251 glioma cells did not contain SP cells. However, the cell lines that contain no SP cells, like U251, might have CSC that don’t overexpress ABC‐T associated with Hoechst33342 efflux. We further examined the presence of SP cells in various cancer cell lines, and as shown in Figure 1(B), most cancer cell lines contained SP cells, whereas the SP fractions varied from 0.2 to 10%.

Figure 1.

The presence of side population (SP) cells in various cancer cell lines. (A) Cells were stained with Hoechst33342 in the presence (+reserpine) or absence (control) of reserpine, and were analyzed using FACS Vantage. The trapezia in each panel indicate the SP area. (B) Summary of the presence of SP cells in various human cancer cell lines. Cells were stained and the presence of SP cells examined, as described in (A). +, Presence of SP cells; −, absence of SP cells.

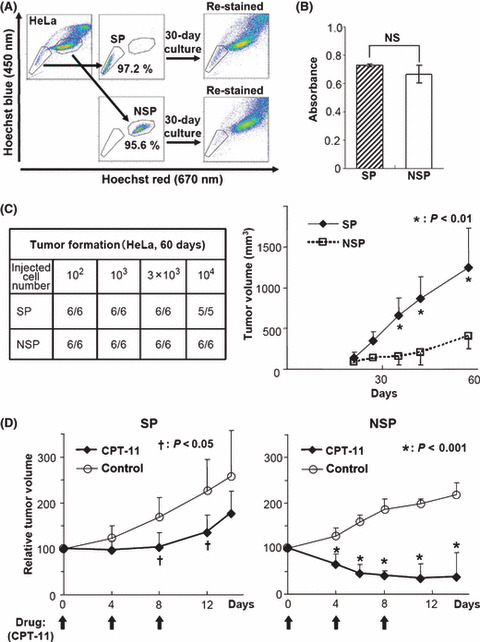

To examine the characteristics of SP cells, we sorted the SP and NSP cells from HeLa using a cell sorter. After sorting, SP and NSP cells were cultured in DMEM growth medium for 30 days. The cells were restained with Hoechst33342 and analyzed by flow cytometry. As shown in Figure 2(A), SP cells derived from HeLa cells showed repopulating capacity. Although NSP cells could proliferate in vitro, at approximately the same speed as the SP cells (Fig. 2B), the SP cell number after 30‐day culture of NSP cells was smaller than that of post‐culture SP cells. Thus, HeLa‐derived NSP cells had weak repopulating capacity. We checked several cell lines and confirmed that the isolated SP cells could repopulate (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Characteristics of side population (SP) cells. (A) SP and non‐SP (NSP) fractions were sorted from HeLa cells. The sorting purities were confirmed by immediate reanalysis. After 30‐day in vitro culture of the separated cells, cells were restained and analyzed (re‐stained). (B) Two thousand sorted HeLa SP and NSP cells were incubated for 72 h, and the viable cell number was assessed by 3‐(4,5‐dimethylthiazol‐2‐yl)‐5‐(3‐carboxymethoxyphenyl)‐2‐(4‐sulfophenyl)‐2H‐tetrazolium (MTS) assay. No significant difference was observed between SP and NSP (NS, P = 0.21). (C) The indicated numbers of sorted HeLa SP and NSP cells were s.c. injected into BALB/c nude mice (n = 6 or 5). Tumor formation was assessed after 60 days (left). The growth of xenografts derived from one hundred sorted HeLa SP and NSP cells (n = 6, *P < 0.01) (right). (D) The xenografted HeLa‐derived SP and NSP tumors were cut into 2‐mm cubes and transplanted into other mice. When secondary tumors reached approximately 100 mm3 in volume, CPT‐11 was administrated intravenously at 67 mg/kg on days 0, 4, and 8 (arrows). The graphs show the relative tumor volume (n = 6). († P < 0.05, *P < 0.001).

We next tested the tumorigenic ability of the isolated SP cells when grafted into nude mice. When HeLa‐derived SP and NSP cells were s.c. injected into nude mice, both fractions exhibited similar tumor‐forming abilities (Fig. 2C, left). Interestingly, tumors derived from HeLa SP cells grew faster than those from NSP cells (Fig. 2C, right). These results suggest that HeLa SP cells, which have the ability of self‐renewal and repopulation, form more aggressive tumors in nude mice than do HeLa NSP cells. To evaluate the chemoresistance of SP cells, we inoculated SP and NSP cells derived from HeLa cells. To equalize the tumor volume, the tumors that formed first were transplanted into other nude mice. The secondary tumors derived from HeLa SP cells also grew faster than those from NSP cells (data not shown). When the secondarily formed tumor volume reached 100 mm3, the mice were treated with CPT‐11. In HeLa SP‐bearing mice, 4‐day intervals (q4d) × 3 treatments of CPT‐11 (67 mg/kg) alone arrested tumor growth without reducing the tumor volume. After termination of CPT‐11 treatment, the remaining tumor started to regrow (Fig. 2D, left). However, treatment of HeLa NSP cells with q4d × 3 of 67 mg/kg of CPT‐11 alone drastically reduced the tumor volume (Fig. 2D, right). These results suggest that SP‐derived tumor cells had robust chemoresistance.

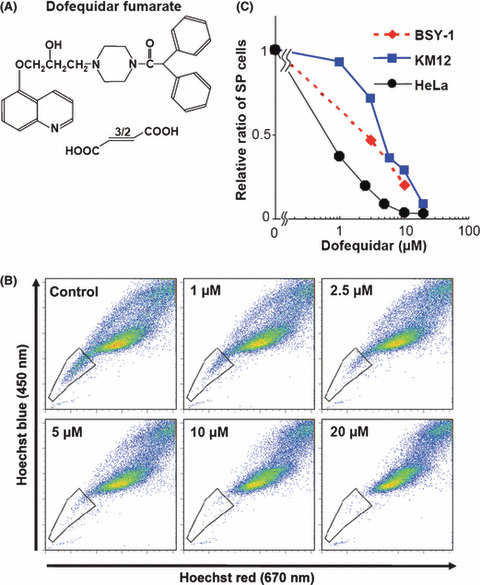

Dofequidar reduced the SP cell ratio. Several reports suggest that CSC show resistance to chemotherapy by expressing such ABC‐T as ABCB1/P‐gp and ABCG2/BCRP.( 1 ) SP cells also have the a exporting ability of Hoechst33342, which is a substrate of ABC‐T (Fig. 1). Expression of ABC‐T might be associated with drug resistance in SP cells (Fig. 2D). Dofequidar (Fig. 3A) is a MDR‐reversing agent currently under clinical evaluation in phase III trials.( 17 ) Therefore, we tested the effects of dofequidar on cancer stem‐like SP cells. As shown in Figure 3(B), dofequidar treatment reduced the HeLa cell number in the SP fraction dose dependently. We obtained similar results using BSY‐1 and KM12 cells (Fig. 3C). These results indicate that dofequidar suppressed Hoechst33342 export by inhibiting transporters highly expressed on SP cell surfaces but not by reducing the number of SP cells themselves.

Figure 3.

Dofequidar reduced the cell number in the side population (SP) fraction. (A) Chemical structure of dofequidar. (B) HeLa cells were stained with 5 μg/mL Hoechst33342 in the presence of the indicated concentrations of dofequidar, and then analyzed. (C) Cells were stained and analyzed as in (B). The relative ratios of SP cell numbers in dofequidar‐treated samples is shown by comparing with them with SP cell numbers in dofequidar‐untreated samples.

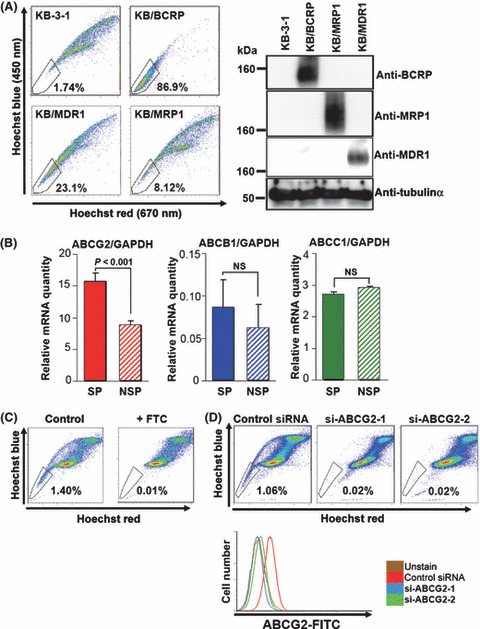

Involvement of ABCG2/BCRP, ABCB1/MDR1, and ABCC1/MRP1 in Hoechst33342 efflux. Because SP cells were separated according to the exporting activity of Hoechst33342 dye, we tried to identify the ABC‐T responsible for Hoechst33342 efflux. Hoechst33342 was reported to be exported by several ABC‐T, mainly ABCG2/BCRP; however, the targets of dofequidar were reported to be ABCB1/P‐gp( 13 ) and ABCC1/MRP1.( 23 ) Then, we evaluated the Hoechst33342 export in ABCB1/P‐gp‐overexpressing KB‐3‐1 cells, ABCB1/P‐gp‐overexpressing KB‐3‐1 cells (KB/MDRI), ABCC1/MRP1‐overexpressing KB‐3‐1 cells (KB/MRP1), and ABCG2/BCRP‐overexpressing KB‐3‐1 cells (KB/BCRP)( 22 ) As shown in Figure 4(A), overexpression of ABCB1/P‐gp, ABCC1/MRP1, or ABCG2/BCRP in KB‐3‐1 cells increased the cell number in the SP fraction (23.1, 8.12, and 86.9%, respectively). Overexpression of each ABC‐T did not affect the expression level of other ABC‐T (Fig. 4A, right), suggesting that all of these ABC‐T were associated with the Hoechst33342 efflux. We also observed that ABCG2/BCRP overexpression in K562 cells decreased Hoechst33342 blue (450 nm) fluorescence compared with parental K562 cells (Fig. S1A). We then compared the ABCB1, ABCC1, and ABCG2 mRNA expression in SP and NSP cells using a quantitative RT‐PCR method. Unexpectedly, the expression levels of ABCB1 and ABCC1 mRNA were not significantly different between them. The ABCG2 mRNA expression in SP cells was significantly higher than that in NSP cells (Fig. 4B). We also observed elevated ABCG2/BCRP expression in SP cells derived from other cancer cells (data not shown). We examined the change in Hoechst33342 staining after FTC, a specific inhibitor of ABCG2/BCRP,( 24 ) treatment, which resulted in a reduction of cell number in the SP fraction (Fig. 4C).

Figure 4.

Efflux of Hoechst33342 by ATP‐binding cassette (ABC) G2/ABCG2/breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP), ABCB1/P‐gp/multidrug resistance (MDR) 1, and ABCC1/MDR‐associated protein (MRP) 1. (A) KB‐3‐1 and the stable transfectants were stained with Hoechst33342 and analyzed using FACS Vantage (left). The cell lysates from KB‐3‐1 and the stable transfectants were immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies (right). (B) mRNA was extracted from the sorted HeLa SP and NSP cells (solid and hatched columns, respectively). The graphs indicate relative mRNA expression levels of each ABC‐transporter normalized with GAPDH. The expression level of ABCG2 mRNA in side population (SP) cells versus that in non‐SP (NSP) cells was significantly different (P < 0.001). The expression levels of ABCB1 and ABCC1 mRNA were not significantly different (NS). (C) HeLa cells were stained with 5 μg/mL Hoechst33342 in the presence (+FTC) or absence (control) of 3 μM fumitremorgin C (FTC) and were analyzed. (D) HeLa cells were transfected with control siRNA or ABCG2 siRNA (si‐ABCG2‐1 and si‐ABCG2‐2). After transfection for 48 h, cells were stained with Hoechst33342 and analyzed (upper panels). The expression level of ABCG2/BCRP protein in the same samples were analyzed (lower panel).

To further confirm the role of ABCG2/BCRP in Hoechst33342 dye efflux, we carried out Hoechst33342 staining after ABCG2 gene silencing using two different ABCG2 siRNA. Both ABCG2 siRNA could almost completely downregulate the ABCG2/BCRP protein expression in HeLa cells (Fig. 4D, bottom panel). Under these conditions, we found a remarkable decrease in the SP cell number (Fig. 4D). These results strongly indicate that ABCG2/BCRP is mainly associated with the export of Hoechst33342 in HeLa SP cells.

Dofequidar inhibits ABCG2/BCRP in addition to ABCB1/P‐gp and ABCC1/MRP1. Because dofequidar could reduce the cell number in the SP fraction that highly expressed ABCG2/BCRP (3, 4), we hypothesized that dofequidar had the ability to inhibit ABCG2/BCRP in addition to the previously reported ABCB1/P‐gp and ABCC1/MRP1.( 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 ) Parental K562 cells or K562 stable transfectants were stained with Hoechst33342 in the presence or absence of ABC‐T inhibitors. Dofequidar but not verapamil could increase the intracellular Hoechst33342 concentration in K562/BCRP cells dose dependently (Fig. S1B). We obtained similar results in KB/BCRP cells (data not shown).

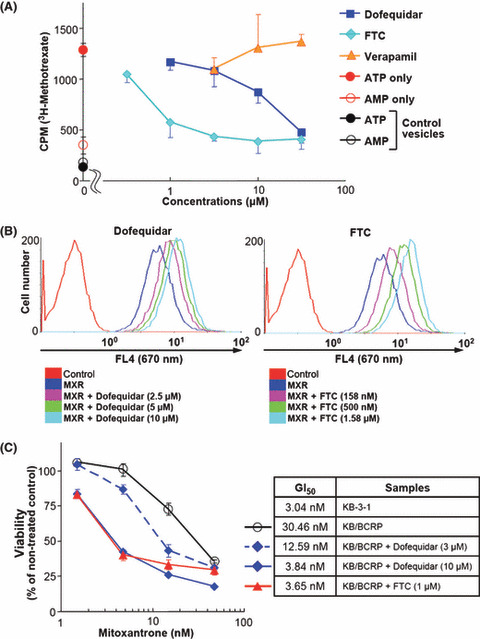

To confirm the result, we carried out an in vitro vesicle transport assay. Membrane vesicles from control or ABCG2/BCRP‐overexpressing insect cells were incubated with [3H]MTX in the presence of ATP or AMP. The ATP‐dependent uptake of [3H]MTX was observed in ABCG2/BCRP‐overexpressing membrane vesicles but not in control vesicles (Fig. 4A). FTC and dofequidar, but not verapamil, inhibited [3H]MTX uptake dose dependently (Fig. 5A). These results suggest that dofequidar had the ability to inhibit ABCG2/BCRP in addition to the previously reported ABCB1/P‐gp and ABCC1/MRP1.( 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 )

Figure 5.

Dofequidar inhibits ATP‐binding cassette (ABC) G2/ABCG2/breast cancer resistantance protein (BCRP)in vitro and in cells. (A) Membrane vesicles from ABCG2/BCRP‐overexpressing insect cells were incubated with 3H‐labeled methotrexate ([3H]MTX) and ATP together with vehicle (ATP only) or the indicated concentrations of dofequidar, fumitremorgin C (FTC), or verapamil at 37°C. In some experiments, membrane vesicles were incubated with [3H]MTX and AMP (AMP only). Membrane vesicles from control insect cells were also incubated with [3H]MTX and ATP or AMP (control vesicles). After incubation for 5 min, the incorporated [3H]MTX was assayed by liquid scintillation. (B) K562/BCRP cells were incubated with 3 μM mitoxantrone (MXR) together with vehicle or the indicated concentrations of dofequidar (MXR+Dofequidar, left panel) or FTC (MXR+FTC, right panel). In some experiments, K562/BCRP cells were incubated without drugs (control). After incubation for 30 min, the fluorescence of MXR at 670 nm was analyzed. (C) KB‐3‐1 and KB/BCRP cells were cultured in medium containing the indicated concentration of MXR with or without dofequidar or FTC for 3 days. Cell viability was evaluated using the 3‐(4,5‐dimethylthiazol‐2‐yl)‐5‐(3‐carboxymethoxyphenyl)‐2‐(4‐sulfophenyl)‐2H‐tetrazolium (MTS) method.

ABCG2/BCRP is known to export various anticancer agents, such as MTX, MXR, topotecan, and SN‐38, and cause chemoresistance.( 25 ) Accordingly, we examined whether dofequidar could reverse chemoresistance by inhibiting ABCG2/BCRP function. First, we tested whether dofequidar inhibited the export of MXR in K562/BCRP cells. K562/BCRP cells were preincubated with dofequidar or FTC for 30 min, followed by MXR incubation in the presence of inhibitors. After 30 min of incubation, MXR incorporation was analyzed by flow cytometry. As a result dofequidar inhibited MXR export, like FTC (Fig. 5B). Second, we tested whether dofequidar induced cell death in KB/BCRP cells. KB/BCRP cells showed 10‐fold resistance to MXR compared to parental KB‐3‐1 cells. Dofequidar could sensitize the KB/BCRP in a dose‐dependent fashion. Treatment with 10 μM dofequidar reversed chemoresistance, to the same level as 1 μM FTC (Fig. 5C).

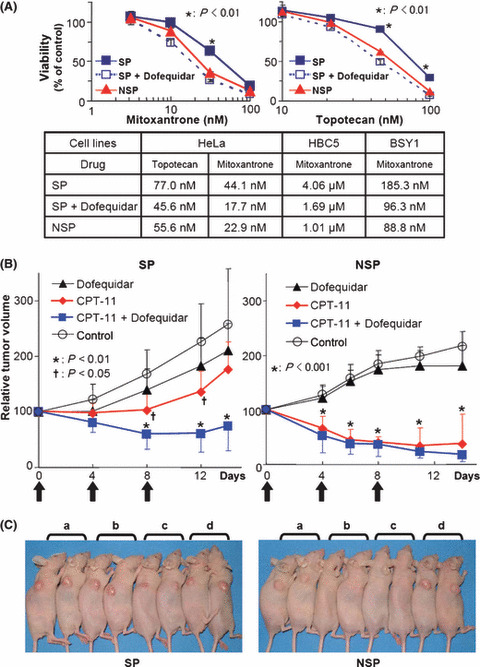

Dofequidar sensitized SP cells to anticancer agents. To overcome the chemoresistance of cancer stem‐like SP cells, we examined the effects of dofequidar on chemosensitivity. Although HeLa‐derived SP cells showed resistance to MXR and topotecan, compared with HeLa‐derived NSP cells, adding dofequidar reversed the sensitivity to MXR and topotecan to a level similar to NSP cells (Fig. 6A). To confirm the results, SP and NSP cells were separated from breast cancer BSY‐1 and HBC‐5 cell lines and examined for changes in chemosensitivity after dofequidar treatment. SP cells derived from BSY‐1 and HBC‐5 cells showed two‐ to four‐fold resistance to chemotherapy compared with NSP cells, and dofequidar effectively sensitized SP cells and decreased the 50% growth inhibition (GI50) values to a level similar to NSP cells (Fig. 6A, lower table).

Figure 6.

Sensitization by dofequidar of cancer stem‐like SP cells to chemotherapeutic drugs in cells and in vivo. (A) SP and NSP cells from HeLa, HBC‐5 or BSY‐1 cells were cultured in medium containing the indicated concentration of mitoxantrone (upper left panel) or topotecan (upper right panel). In some experiments, side population (SP) cells were cultured in the presence of 3 μM dofequidar (SP+Dofequidar). The lower panel gives a summary of 50% growth inhibition (GI50) values in each experiment. (B) The xenografted HeLa‐derived SP and non‐SP (NSP) secondary tumors were treated with 200 mg/kg dofequidar, 67 mg/kg CPT‐11, or both on days 0, 4, and 8 (arrows) (n = 6). Graphs show relative tumor volume. The data of control and CPT‐11‐treated groups were the same as in Figure 2(D). The xenografted SP tumor size treated with CPT‐11 versus control (†) or that treated with CPT‐11 plus dofequidar versus control (*) was significantly different (P < 0.05 and P < 0.01, respectively). (C) The mice bearing HeLa SP (left) or NSP (right) tumors were photographed at 14 days after first treatment. a, Dofequidar‐treated; b, CPT‐11‐treated; c, CPT‐11 plus dofequidar‐treated; d, control.

FTC is not suitable for clinical studies because of its severe toxicity, but it strongly and specifically inhibits ABCG2/BCRP.( 26 ) On the other hand, dofequidar exhibits low toxicity and has already been approved for clinical trials. To overcome the chemoresistance of cancer stem‐like SP cells in vivo, we evaluated the antitumor activity of CPT‐11 plus dofequidar in a clinically relevant model. HeLa‐derived SP and NSP cells were transplanted into nude mice, and the xenografted tumors were treated with CPT‐11 with or without dofequidar. Dofequidar (200 mg/kg) was orally administrated 30 min before CPT‐11 (67 mg/kg) injection. Although xenografted HeLa SP cells showed resistance to CPT‐11, co‐treatment of the mice with dofequidar drastically decreased the tumor volume (Fig. 6B, left panel), like that seen in CPT‐11‐treated or CPT‐11 plus dofequidar‐treated NSP‐bearing mice (Fig. 6B, right panel). Dofequidar alone had almost no effect on SP‐ or NSP‐derived tumor growth in vivo. To assess the toxicity, we measured the bodyweight of the tumor‐bearing mice. The mice seemed to be healthy (Fig. 6C), and the change in bodyweight was very small (data not shown). Thus CPT‐11 plus dofequidar therapy appeared to have good therapeutic efficacy in vivo by sensitizing cancer stem‐like cells to anticancer drugs.

Discussion

It is still difficult to cure advanced cancer with chemotherapy because advanced cancer often shows resistance to many chemotherapeutic agents. Although MDR was thought to result from treatment with chemotherapy,( 27 ) recent studies suggest that the primary tumor already has chemotherapy‐ or radiation therapy‐resistant cells called CSC.( 1 ) Because CSC are able to self‐renew and regenerate the tumor, as likely as primary tumor, CSC are thought to be associated with recurrence. Therefore, it is important to study the characteristics of CSC and to develop new therapies targeting them.

In the present study, we used SP cells as a model of cancer stem‐like cells. Various cancer cell lines contain SP cells (Fig. 1) that possess the repopulating ability (Fig. 2A). In the breast cancer cell line BSY‐1, SP cells have higher cancer‐initiating ability than that of NSP cells. Therefore, CSC were concentrated in BSY‐1 SP cells (data not shown). On the other hand, both SP and NSP cells from the HeLa cell line could initiate tumor formation after injection of a very few number of cells (Fig. 2C). SP cells, but not NSP cells, from HeLa, however, showed resistance to several anticancer agents (2, 6). Therefore, SP cells from cancer cell lines may not always correspond to CSC, but they may, at least, contain more malignant cells.

To address the targeting of CSC, various efforts have been made, and several studies have reported the success of inducing cell death or differentiation in CSC.( 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 ) In the present study, we showed that inhibition of ABC‐T by dofequidar was one possible method to overcome anticancer drug resistance in cancer stem‐like SP cells in vitro and in vivo (5, 6).

In human cancer, ABCB1/P‐gp, ABCC1/MRP1, and ABCG2/BCRP are the most studied, but there are more ABC‐T that relate to cancer. Recently, ABCB5, originally reported to be expressed on the surface of clinically malignant melanoma and a major efflux mediator of doxorubicin in melanoma,( 33 ) marked primitive cells (malignant melanoma‐initiating cells) capable of recapitulating melanomas in xenotransplantation models. Further, targeting malignant melanoma‐initiating cells with a specific antibody against ABCB5 inhibited tumor growth by inducing antibody‐dependent, cell‐mediated cytotoxicity.( 34 ) Indeed, it has already been reported that some ABC‐T are overexpressed in CSC.( 1 , 7 , 35 ) Thus, it is important to understand the characteristics of ABC‐T, such as its endogenous substrate, and the mechanisms of ABC‐T overexpression in CSC.

From the results of phase III clinical trials of dofequidar for breast cancer patients, dofequidar treatment showed great advances in the patient group of no prior therapy.( 17 ) This result indicates that CSC already existed in primary tumors, and they tended to remain after treatment with anticancer agents alone. Therefore, treating these patients with dofequidar plus conventional chemotherapy might effectively kill the CSC, resulting in good progression‐free survival and overall survival in the clinical study. If the CSC remained, they might cause recurrence and might acquire resistance to therapy. Therefore co‐administration of a MDR‐reversing agent such as dofequidar in primary chemotherapy could drastically reduce the rate of recurrence.

In the present study we used CPT‐11 as an anticancer agent in in vivo experiments (2, 6). CPT‐11 is one of the most widely prescribed drugs for various cancers, including lung, stomach, colon, and cervical cancer.( 18 ) CPT‐11 is a prodrug converted into the active compound SN‐38 in the liver. CPT‐11 is exported from cells by ABCB1/P‐gp and ABCC1/MRP1,( 19 , 20 ) and the active metabolite SN‐38 is exported by ABCG2/BCRP.( 21 ) As dofequidar could inhibit ABCB1/P‐gp, ABCC1/MRP1, and ABCG2/BCRP, we tried to treat xenografted tumors with CPT‐11 together with dofequidar. From our study, the combination of dofequidar and CPT‐11 was shown to be effective in killing of the SP cells in vivo without severe side effects (Fig. 6). Dofequidar could have future use as a chemotherapy‐sensitizing agent targeting CSC.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Supporting information

Fig. S1. Dofequidar inhibits ABCG2 / BCRP in addition to ABCB1.

Table S1. Sequence information of qRT‐PCR primers and siRNA for ABCG2.

Please note: Wiley‐Blackwell are not responsible for the content or functionality of any supporting materials supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the corresponding author for the article.

Supporting info item

Supporting info item

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs T. Yamori, A. Tomida, and H. Seimiya for helpful discussions and Ms S. Tsukahara for technical assistance. This study was supported in part by special grants from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan, 19790241 and 20015046 (to R. Katayama and N. Fujita, respectively). This study was also supported in part by a grant from the Vehicle Racing Commemorative Foundation and the Mochida Memorial Foundation for Medical and Pharmaceutical Research (to N. Fujita).

References

- 1. Dean M, Fojo T, Bates S. Tumour stem cells and drug resistance. Nat Rev 2005; 5: 275–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Goodell MA, Brose K, Paradis G, Conner AS, Mulligan RC. Isolation and functional properties of murine hematopoietic stem cells that are replicating in vivo . J Exp Med 1996; 183: 1797–806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zhou S, Schuetz JD, Bunting KD et al. The ABC transporter Bcrp1/ABCG2 is expressed in a wide variety of stem cells and is a molecular determinant of the side‐population phenotype. Nat Med 2001; 7: 1028–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Scharenberg CW, Harkey MA, Torok‐Storb B. The ABCG2 transporter is an efficient Hoechst 33342 efflux pump and is preferentially expressed by immature human hematopoietic progenitors. Blood 2002; 99: 507–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Barile L, Messina E, Giacomello A, Marban E. Endogenous cardiac stem cells. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 2007; 50: 31–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kato K, Yoshimoto M, Kato K et al. Characterization of side‐population cells in human normal endometrium. Hum Reprod 2007; 22: 1214–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chiba T, Kita K, Zheng YW et al. Side population purified from hepatocellular carcinoma cells harbors cancer stem cell‐like properties. Hepatology 2006; 44: 240–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Haraguchi N, Utsunomiya T, Inoue H et al. Characterization of a side population of cancer cells from human gastrointestinal system. Stem Cells 2006; 24: 506–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hirschmann‐Jax C, Foster AE, Wulf GG et al. A distinct “side population” of cells with high drug efflux capacity in human tumor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2004; 101: 14 228–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kondo T, Setoguchi T, Taga T. Persistence of a small subpopulation of cancer stem‐like cells in the C6 glioma cell line. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2004; 101: 781–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tsuruo T, Iida H, Tsukagoshi S, Sakurai Y. Overcoming of vincristine resistance in P388 leukemia in vivo and in vitro through enhanced cytotoxicity of vincristine and vinblastine by verapamil. Cancer Res 1981; 41: 1967–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Szakacs G, Paterson JK, Ludwig JA, Booth‐Genthe C, Gottesman MM. Targeting multidrug resistance in cancer. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2006; 5: 219–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Suzuki T, Fukazawa N, San‐nohe K, Sato W, Yano O, Tsuruo T. Structure‐activity relationship of newly synthesized quinoline derivatives for reversal of multidrug resistance in cancer. J Med Chem 1997; 40: 2047–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Naito M, Matsuba Y, Sato S, Hirata H, Tsuruo T. MS‐209, a quinoline‐type reversal agent, potentiates antitumor efficacy of docetaxel in multidrug‐resistant solid tumor xenograft models. Clin Cancer Res 2002; 8: 582–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nakanishi O, Baba M, Saito A et al. Potentiation of the antitumor activity by a novel quinoline compound, MS‐209, in multidrug‐resistant solid tumor cell lines. Oncol Res 1997; 9: 61–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sato W, Fukazawa N, Nakanishi O et al. Reversal of multidrug resistance by a novel quinoline derivative, MS‐209. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 1995; 35: 271–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Saeki T, Nomizu T, Toi M et al. Dofequidar fumarate (MS‐209) in combination with cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and fluorouracil for patients with advanced or recurrent breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2007; 25: 411–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rothenberg ML. Topoisomerase I inhibitors: review and update. Ann Oncol 1997; 8: 837–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chu XY, Suzuki H, Ueda K, Kato Y, Akiyama S, Sugiyama Y. Active efflux of CPT‐11 and its metabolites in human KB‐derived cell lines. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1999; 288: 735–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jansen WJ, Hulscher TM, Van Ark‐Otte J, Giaccone G, Pinedo HM, Boven E. CPT‐11 sensitivity in relation to the expression of P170‐glycoprotein and multidrug resistance‐associated protein. Br J Cancer 1998; 77: 359–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kawabata S, Oka M, Shiozawa K et al. Breast cancer resistance protein directly confers SN‐38 resistance of lung cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2001; 280: 1216–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kage K, Tsukahara S, Sugiyama T et al. Dominant‐negative inhibition of breast cancer resistance protein as drug efflux pump through the inhibition of S‐S dependent homodimerization. Int J Cancer 2002; 97: 626–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Narasaki F, Oka M, Fukuda M et al. A novel quinoline derivative, MS‐209, overcomes drug resistance of human lung cancer cells expressing the multidrug resistance‐associated protein (MRP) gene. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 1997; 40: 425–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rabindran SK, Ross DD, Doyle LA, Yang W, Greenberger LM. Fumitremorgin C reverses multidrug resistance in cells transfected with the breast cancer resistance protein. Cancer Res 2000; 60: 47–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mao Q, Unadkat JD. Role of the breast cancer resistance protein (ABCG2) in drug transport. AAPS J 2005; 7: E118–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Allen JD, Van Loevezijn A, Lakhai JM et al. Potent and specific inhibition of the breast cancer resistance protein multidrug transporter in vitro and in mouse intestine by a novel analogue of fumitremorgin C. Mol Cancer Ther 2002; 1: 417–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Borst P, Evers R, Kool M, Wijnholds J. A family of drug transporters: the multidrug resistance‐associated proteins. J Natl Cancer Inst 2000; 92: 1295–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jordan CT, Guzman ML, Noble M. Cancer stem cells. N Engl J Med 2006; 355: 1253–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ito K, Bernardi R, Morotti A et al. PML targeting eradicates quiescent leukaemia‐initiating cells. Nature 2008; 453: 1072–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Jin L, Hope KJ, Zhai Q, Smadja‐Joffe F, Dick JE. Targeting of CD44 eradicates human acute myeloid leukemic stem cells. Nat Med 2006; 12: 1167–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Li L, Neaves WB. Normal stem cells and cancer stem cells: the niche matters. Cancer Res 2006; 66: 4553–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Piccirillo SG, Reynolds BA, Zanetti N et al. Bone morphogenetic proteins inhibit the tumorigenic potential of human brain tumour‐initiating cells. Nature 2006; 444: 761–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Frank NY, Margaryan A, Huang Y et al. ABCB5‐mediated doxorubicin transport and chemoresistance in human malignant melanoma. Cancer Res 2005; 65: 4320–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Schatton T, Murphy GF, Frank NY et al. Identification of cells initiating human melanomas. Nature 2008; 451: 345–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ho MM, Ng AV, Lam S, Hung JY. Side population in human lung cancer cell lines and tumors is enriched with stem‐like cancer cells. Cancer Res 2007; 67: 4827–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1. Dofequidar inhibits ABCG2 / BCRP in addition to ABCB1.

Table S1. Sequence information of qRT‐PCR primers and siRNA for ABCG2.

Please note: Wiley‐Blackwell are not responsible for the content or functionality of any supporting materials supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the corresponding author for the article.

Supporting info item

Supporting info item