Abstract

The epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)–RAS–RAF–mitogen‐activated protein kinase signaling cascade is an important pathway in cancer development and recent reports show that EGFR and its downstream signaling molecules are mutated in a number of cancers. We have analyzed 91 Japanese head and neck squamous cell carcinomas (HNSCC) and 12 HNSCC cell lines for mutations in EGFR, ErbB2, and K‐ras. Exons encoding the hot‐spot regions in the tyrosine kinase domain of both EGFR (exons 18, 19, and 21) and ErbB2 (exons 18–23), as well as exons 1 and 2 of K‐ras were amplified by polymerase chain reaction and sequenced directly. EGFR expression was also analyzed in 65 HNSCC patients using immunohistochemistry. Only one silent mutation, C836T, was found in exon 21 of EGFR in the UT‐SCC‐16A cell line and its corresponding metastasic cell line UT‐SCC‐16B. No other mutation was found in EGFR, ErbB2, or K‐ras. All tumors showed EGFR expression. In 21 (32%) tumors, EGFR was expressed weakly (+1). In 27 (42%) tumors it was expressed (+2) moderately, and in 17 (26%) tumors high expression (+3) was detected. Overexpression (+2, +3) was found in 44 tumors (68%). A worse tumor differentiation and a positive nodal stage were significantly associated with EGFR overexpression (P = 0.02, P = 0.032, respectively). Similar to patients from western ethnicity, mutations are absent or rare in Japanese HNSCC. Protein overexpression rather than mutation might be responsible for activation of the EGFR pathway in HNSCC. (Cancer Sci 2008; 99: 1589–1594)

Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) is the sixth most frequent cancer worldwide.( 1 ) Recently, new strategies based on molecular targeted therapy have been developed to combat this fatal disease. The epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), a transmembrane protein and one of the ErbB family of receptors, is a promising target for molecular therapy. This receptor has an intrinsic tyrosine kinase (TK) activity, and regulates cell growth in response to binding of ligands like epidermal growth factor (EGF) or transforming growth factor α.( 2 ) Ligand binding leads to dimerization of two receptors and autophosphorylation of the TK domain located on the cytoplasmic side, resulting in receptor activation. The activated receptor recruits signaling complexes and activates the RAS–RAF–mitogen‐activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway. This pathway, along with other signaling pathways of EGFR, is a potent regulator of tumor cell growth, invasion, angiogenesis, and metastasis. Likewise, activation of this pathway can also occur through heterodimerization between EGFR and ErbB2, another member of the ErbB family. Although ErbB2 does not act as a receptor for EGF, it can decrease the rate of ligand dissociation from the cognate receptor EGFR.( 3 ) This results in stronger and more prolonged activation of the EGFR signaling network.

Recently, mutations in the EGFR TK domain have been found, especially in the adenocarcinoma subtype of non‐small‐cell lung cancer (NSCLC). These mutations are associated with response to tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI) like gefitinib.( 4 ) Interestingly, a higher mutation rate was found in non‐smoking female patients of Japanese ethnicity.( 5 ) It is worth noting that some HNSCC cases have also shown response to TKI in phase II clinical trials.( 6 ) However, the mutation status of EGFR and ErbB2 in HNSCC has not been established, especially in Japanese patients.

Knowledge of the expression and mutation status of EGFR and other ErbB receptors as well as downstream effectors like K‐ras would help us to better understand the response of these patients to molecular targeted therapy. EGFR overexpression has been identified in various tumor types. Overexpression might lead to effects that are similar to those of mutations. However, the expression and prognostic significance in HNSCC have yielded controversial results necessitating more studies in this field. Therefore, we have also studied EGFR expression by immunohistochemistry (IHC) and this was correlated with the clinicopathological variables.

Materials and Methods

Tissue samples and patients. Archival tumor samples were collected randomly from 91 HNSCC at Okayama University Hospital between 1994 and 2003. The tumors were from the oral cavity (n = 51), larynx (n = 17), hypopharynx (n = 14), and oropharynx (n = 9). Informed consent was obtained from each patient. Genomic DNA was isolated from frozen tissues by sodium dodecylsulfate–proteinase K treatment, phenol–chloroform extraction, and ethanol precipitation.

Cell lines. Twelve HNSCC cell lines were analyzed for mutations of EGFR, ErbB2, and K‐ras. Four cell lines, HSC‐2, HSC‐3, HSC‐4, and Ca9‐22, were obtained from the Cell Resource Center of the Biomedical Research Institute of Development, Aging and Cancer, Tohoku University. Ca9‐22 is known to overexpress EGFR. The remaining eight cell lines, UT‐SCC‐12A, UT‐SCC‐12B, UT‐SCC‐16A, UT‐SCC‐16B, UT‐SCC‐60A, UT‐SCC‐60B, UT‐SCC‐24A, and UT‐SCC‐110B, were kindly provided by Dr Reidar Grenman, University of Turku, Finland. The first six cell lines were paired and derived from the primary and metastatic tumors of the same patients. All cell lines were maintained in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium (Gibco, Tokyo, Japan) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco), 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 µg/mL streptomycin (Invitrogen, Tokyo, Japan), and 25 mg/mL amphotericin B (Gibco) in a CO2 incubator with an atmosphere of 95% air plus 5% CO2 at 37°C. DNA was extracted for mutation analysis using the same method as above.

Mutation analysis. The hot‐spot regions of the TK domains of both EGFR (exons 18, 19, 21) and ErbB2 (exons 18–23) as well as exons 1 and 2 of K‐ras (covering codons 12, 13, and 61) were amplified using the following primer pairs (sense and antisense, respectively): EGFR exon 18, 5′‐CAATGAGCTGGCAAGTGCCGTGTC‐3′ and 5′‐GAGTTTCCCAAACACTCAGTGAAAC‐3′; EGFR exon 19, 5′‐GCAATATCAGCCTTAGGTGGTGCGGCTC‐3′ and 5′‐CATAGAAAGTGAACATTTAGGATGTG‐3′; EGFR exon 21, 5′‐CTAACGTTCGCCAGCCATAAGTCC‐3′ and 5′‐GCTGCGAGCTGACCCAGAATGTCTGG‐3′; ErbB2 exon 18, 5′‐GACACCTAGCGGAGCGATGC‐3′ and 5′‐ATCAGAACTGCCGACCACACC‐3′; ErbB2 exon 19, 5′‐GCCCACGCTCTTCTCACTCA‐3′ and 5′‐ATGGGGTCCTTCCTGTCCTC‐3′; ErbB2 exon 20 5′‐GTGATGGTTGGGAGGCTGTG‐3′ and 5′‐GCTGCACCGTGGATGTCAG‐3′; and 5′‐CATATGTCTCCCGCCTTCTG‐3′, 5′‐GCTGCACCGTGGATGTCAG‐3′; ErbB2 exon 21 5′‐CATATGTCTCCCGCCTTCTG‐3′ and 5′‐CTGCTCCTTGGTCCTTCAC‐3′; ErbB2 exon 22 5′‐GGCCACCTCCCCACAACACA‐3′ and 5′‐CACCCACCCCTCCCAACACC‐3′; ErbB2 exon 23 5′‐CACCCACCCCTCCCAACACC‐3′ and 5′‐GCTCAGCCACGCACATTTGAC‐3′; K‐ras exon 1, 5′‐GGCCTGCTGAAAATGATGA‐3′ and 5′‐GTCCTGCACCAGTAATATGC‐3′; and K‐ras exon 2, 5′‐CTGTAATAATCCAGACTGTG‐3′ and 5′‐TCCCCAGTCCTCATGTACTG‐3′. The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was carried out in 20 µL of reaction mixture with 20 pmol of each primer, 200 ng of genomic DNA, 1× PCR buffer, 200 µM of each deoxynucleotide triphosphate, and 0.5 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Takara, Kyoto, Japan). Initial denaturation at 94°C for 3 min was followed by amplification for 35 cycles at 94°C for 30 s, annealing for 30 s, and extension at 72°C for 1 min. A final extension step at 72°C for 7 min was added.

The PCR products (2.5 µL) were then mixed with 0.5 µL of Exosap (usb, Cleveland, Ohio, USA), incubated at 37°C for 30 min, and then heated to 80°C for 20 min. The PCR products were reamplified using a BigDye terminator sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster, CA, USA), ethanol precipitated, and sequenced directly on an automated sequence machine (ABI Prism 3100; Applied Biosystems).

Immunohistochemistry of EGFR. Archival paraffin blocks were used for IHC. Sixty‐five of the 91 samples used in the mutation study were chosen as a cohort for the IHC study.

Cut tissue sections (4 µm) were deparaffinized in xylene for 20 min, and then rehydrated in graded alcohol solutions. The endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked by immersing the sections in 3% H2O2 in methanol for 30 min. For antigen retrieval sections were boiled in 0.01 mol/L citrate buffer (pH 6.0) in a pressure cooker for 5 min; this was followed by treatment with 10% normal horse serum for 30 min. Sections were then incubated with the primary EGFR antibody (dilution 1:25; Novocastra, Newcastle, UK) at 4°C overnight. Identification of immunoreactive sites was achieved by subsequent incubation with a biotinylated secondary antibody for 30 min, followed by detection using the avidin–biotin complex (ABC) method (Vectastain ABC Kit; Funakoshi, Tokyo, Japan). Sections were then reacted with 0.02% 3‐3‐diaminobenzidine (Wako, Osaka, Japan) with 0.006% H2O2 in 0.05 mol/L Tris–HCl (pH 7.6). The sections were then counterstained with Mayer's hematoxylin and mounted. Membranous staining of EGFR was considered for immunoreactivity and scoring of the tumors was done by two pathologists (HN, MSA) blinded to each other and to the clinical data of the patients. A scoring system adapted from Fisher et al. was used to score the tumors.( 7 )

Statistical analysis. The patient's clinicopathological variables were correlated with EGFR protein expression. Survival analysis was carried out with Kaplan–Meier curves and the related log‐rank tests. All of the statistical analysis was carried out using SPSS for Windows package (15.0) (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Mutation analysis. Mutation analysis of hot‐spots in EGFR, ErbB2, and the downstream signaling molecule K‐ras was carried out in 91 HNSCC and 12 HNSCC cell lines. Only one silent mutation in exon 21 of EGFR (C836T) was detected in the UT‐SCC‐16A cell line and the corresponding metastatic cell line UT‐SCC‐16B (Suppl. Fig. S1). All other cell lines and tumors showed a normal sequence for EGFR, ErbB2, and K‐ras.

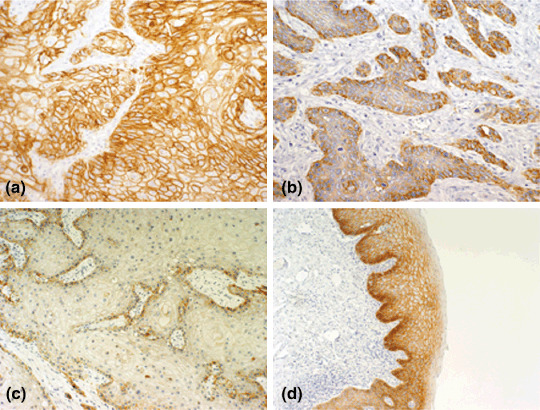

Immunohistochemistry of EGFR. A scoring system that took into consideration the intensity of the staining as well as the percentage of positive tumor cells was used. Figure 1a–c shows representative examples of the IHC. Twenty‐one of 65 tumors (32%) showed weak (+1) EGFR expression, 27 tumors (42%) had moderate (+2) expression, and 17 tumors (26%) had strong (+3) expression. Considering the +2 and +3 cases as overexpression of EGFR, overexpression was found in 44 of 65 cases (68%). The intensity of staining was stronger in the outer cells of tumor nests and decreased significantly in the keratinized central cells. The intensity was also stronger in the invasive front. In the normal epithelium, expression was confined to the basal cell layer. However, the dysplastic epithelium adjacent to the tumor (available in 36 specimens) showed increased expression in the basal cell layer as well as in the spinous layer. The intensity of expression was proportional to the degree of dysplasia and decreased gradually in the direction of the surface epithelium. The keratinized upper‐most layer was negative (Fig. 1d). This pattern of expression was similar to the pattern seen in the tumor nests in which the staining intensity was less in the central region of the nests compared to the basal cells in the periphery.

Figure 1.

Representative examples of immunohistochemistry of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR). (a) Tumors with dark membrane staining that is easily visible with a low‐power objective and involves >50% of cells were scored as +3. (b) Tumors showing focal darkly staining areas in <50% of cells or moderate membrane staining of >50% of cells were scored as +2. (c) Tumors showing focal moderate staining in <50% of cells, or pale membrane staining in any proportion of the cells not easily seen under a low power were scored as +1. (d) EGFR expression in the dysplastic epithelium adjacent to the tumor, dark staining in the basal layer, expression was also extended in the spinous layer of the epithelium but sparing the outer most keratinized layer.

Correlation of EGFR expression with the patient's clinical variables. A summary of the patient's characteristics is shown in Table 1. All patients had surgical intervention, and 13 of them had received chemotherapy or radiotherapy before surgery. The follow‐up period ranged from 2 to 114 months (mean 35.9 months, median 30 months, and standard deviation 25.36 months). Thirty‐six patients died due to the cancer and one patient died by another cause during this period. During the follow‐up period, 28 tumors relapsed, of which seven were distant, and 21 patients had regional or local recurrences. Postoperative radiotherapy or chemotherapy was carried out in 17 patients. The clinicopathological variables were compared statistically between tumors with low expression and overexpression of EGFR. No correlation was found between expression level and the patients’ age, sex, smoking or alcohol consumption, tumor stage, tumor node metastasis (TNM) stage, or previous cancer history. However, a significant correlation was found with tumor differentiation and nodal stage (P = 0.02 and P = 0.032, respectively). Patients with a positive nodal stage and moderate–poor tumor differentiation showed higher EGFR expression (Table 1).

Table 1.

Relationship between epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) expression and clinicopathological characteristics

| Predictor | EGFR protein expression | P‐value* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | Low (%) | Moderate–high (%) | ||

| Total n = 65 (100) | n = 21 (32.3) | n = 44 (67.7) | ||

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 56 (86.2) | 18 (32.1) | 38 (67.9) | |

| Female | 9 (13.8) | 3 (33.3) | 6 (67.7) | 0.94 |

| Age (years) † | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 64.2 ± 7.6 | 63.1 ± 9.32 | 0.64 | |

| Smoking | ||||

| Yes | 47 (75.8) | 14 (29.8) | 33 (70.2) | |

| No | 15 (24.2) | 6 (40) | 9 (60) | 0.46 |

| Alcohol consumption | ||||

| Yes | 34 (55.7) | 12 (35.3) | 22 (64.7) | |

| No | 27 (44.3) | 8 (29.6) | 19 (70.4) | 0.64 |

| Primary tumor site | ||||

| Oral cavity | 37 (56.9) | 15 (40.5) | 22 (59.5) | |

| Larynx | 11 (16.9) | 1 (9.1) | 10 (90.9) | |

| Hypopharynx | 9 (13.8) | 2 (22.2) | 7 (77.7) | |

| Oropharynx | 8 (12.3) | 3 (37.5) | 5 (62.5) | 0.22 |

| Tumor stage | ||||

| Early (T1–T2) | 23 (35.9) | 10 (43.5) | 13 (56.5) | |

| Late (T3–T4) | 41 (64.1) | 10 (24.4) | 31 (75.6) | 0.114 |

| TNM stage ‡ | ||||

| Early (I–II) | 18 (28.1) | 8 (44.4) | 10 (55.6) | |

| Late (III–IV) | 46 (71.9) | 12 (26.1) | 34 (73.9) | 0.154 |

| Nodal stage | ||||

| Negative (N0) | 25 (38.5) | 12 (48) | 13 (52) | |

| Positive (N+) | 40 (61.5) | 9 (22.5) | 31 (77.5) | 0.032 |

| Differentiation | ||||

| Well | 24 (36.9) | 12 (50) | 12 (50) | |

| Moderate–poor | 41 (63.1) | 9 (22) | 32 (78) | 0.02 |

| Previous cancer history | ||||

| Exist | 8 (12) | 1 (12.5) | 7 (87.5) | |

| Not exist | 57 (88) | 16 (28.1) | 41 (71.9) | 0.35 |

Tumors with unknown situation for smoking (n = 3), alcohol consumption (n = 4), T stage (n = 1), and tumor node metastasis (TNM) stage (n = 1) were not included in the evaluation.

P‐value was calculated by χ2‐test.

Student's t‐test.

According to the International Union Against Cancer 1997 TNM classification system.

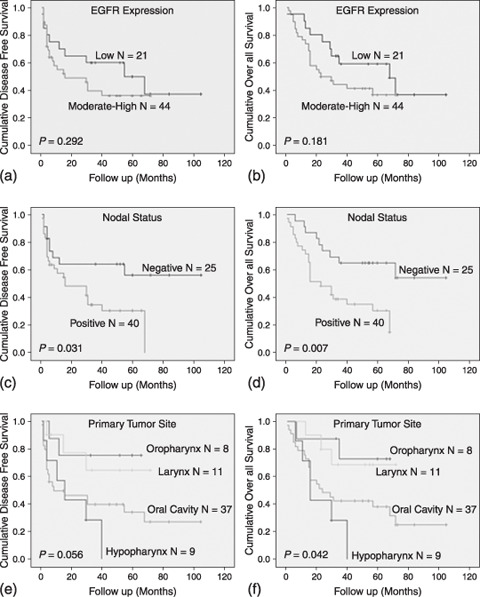

Survival analysis. Kaplan–Meier analysis and the log rank test for disease‐free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS) were carried out. The 5‐year survival rates according to EGFR expression and other clinicopathological variables are shown in Table 2. Kaplan–Meier survival curves were plotted according to EGFR expression, nodal status, and the location of the primary tumor (Fig. 2).

Table 2.

Univariate 5‐year overall survival and disease‐free survival analysis for clinicopathological characteristics and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) expression

| Predictor | Overall survival (%) (95% CI) † | P‐value* | Disease‐free survival (%) (95% CI) | P‐value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 48 (44–70) | 48 (39–67) | ||

| Female | 25 (11–51) | 0.108 | 14 (3–43) | 0.053 |

| Smoking | ||||

| Yes | 43 (39–66) | 43 (33–62) | ||

| No | 53 (34–66) | 0.624 | 34 (24–61) | 0.807 |

| Alcohol consumption | ||||

| Yes | 40 (36–66) | 40 (29–62) | ||

| No | 50 (35–61) | 0.692 | 44 (31–59) | 0.627 |

| Primary tumor site | ||||

| Oral cavity | 38 (32–60) | 34 (25–57) | ||

| Larynx | 68 (42–71) | 64 (34–71) | ||

| Hypopharynx | – | – | ||

| Oropharynx | 73 (40–71) | 0.042 | 75 (35–69) | 0.056 |

| EGFR expression | ||||

| Weak | 59 (45–81) | 50 (37–77) | ||

| Moderate–high | 36 (7–39) | 0.181 | 36 (23–43) | 0.292 |

| T stage | ||||

| Early T (T1–T2) | 57 (46–82) | 48 (41–81) | ||

| Late T (T3–T4) | 39 (29–52) | 0.117 | 38 (24–49) | 0.179 |

| TNM stage | ||||

| Early stage (I–II) | 56 (46–84) | 41 (36–81) | ||

| Late stage (III–IV) | 42 (31–53) | 0.164 | 42 (27–50) | 0.301 |

| Nodal stage | ||||

| Negative (N0) | 54 (55–88) | 57 (45–85) | ||

| Positive (N+) | 32 (25–42) | 0.007 | 31 (20–39) | 0.031 |

| Differentiation | ||||

| Well | 45 (32–67) | 34 (25–63) | ||

| Moderate–poor | 43 (37–60) | 0.545 | 47 (33–57) | 0.366 |

| Previous cancer history | ||||

| Exist | 44 (31.8–55.8) | 40 (26–50) | ||

| Not exist | 48 (40.2–70.1) | 0.915 | 43 (35–67) | 0.871 |

Log rank test.

The lower and upper 95% confidence interval (CI) for the median. In the case of hypopharynx tumors, the median has not been reached. TNM, tumor node metastasis.

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier curves for disease‐free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS) analysis of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) expression, lymph node metastasis, and primary tumor site. (a,b) EGFR expression was not significantly related to DFS or OS. (c,d) Nodal stage was the most accurate predictor for DFS and OS. (d,f) According to the site of the primary tumor, tumors of the oropharynx and larynx had a better OS and DFS compared to tumors of the oral cavity and hypopharynx.

In the case of EGFR overexpression, both curves shifted down. However, the association was not significant using the log rank test (P = 0.29 and P = 0.18 for DFS and OS, respectively) (Fig. 2a,b). Nevertheless, there was a tendency toward a lower survival in patients with EGFR overexpression. For DFS, the mean survival time was 57.03 months in patients with low EGFR expression, whereas it was 33.43 months in those with overexpression. For OS, the mean survival time was 62.66 months for patients with low EGFR expression, whereas it was 37.9 months in the patients with overexpression. Positive nodal status was significantly associated with poor DFS and OS (P = 0.031 and P = 0.007, respectively). These results demonstrate that nodal status was the most accurate predictor for survival in HNSCC (Table 2) (Fig. 2c,d). When OS was analyzed according to tumor location, patients with laryngeal and oropharyngeal tumors had a better survival probability (P = 0.042) (Fig. 2e,f).

Discussion

Recently, molecular targeted therapy has gained a lot of interest in the battle against cancer. Clinical trials suggest that EGFR targeting agents can help many cancer patients, including those with HNSCC.( 6 ) Moreover, cetuximab, an anti‐EGFR monoclonal antibody, has recently been approved for HNSCC treatment. Bauman et al. reported two successful cases of treatment for recurrent squamous cell carcinoma of the skin with cetuximab.( 8 ) However, improvements with chemoradiotherapy might be achieved by inhibiting molecules that are selectively or preferentially expressed on tumor cells, such as EGFR and cyclooxygenase (COX)‐2, which have both shown to provide cells with resistance to drugs or radiation.( 9 ) Another approach to inhibit EGFR is by using TKI, such as gefitinib and erlotinib. Mutations in this domain are frequent in lung cancer, especially of Asian ethnicity.( 5 ) Interestingly, approximately 80% of patients with EGFR mutations respond to EGFR TKI, whereas only 10% of those without mutations do so.( 10 ) These mutations affect amino acids near the ATP binding pocket, which is targeted by gefitinib, resulting in increased gene activation and sensitivity to TKI.( 11 ) Somatic mut‐ations of ErbB2 have also been reported in less than 5% of NSCLC. These involve in‐frame duplications or insertions within exon 20 that correspond to the identical nine‐codon region in exon 20 of EGFR, where duplications or insertions have also been reported.( 12 )

Because a considerable response to gefitinib has also been noticed in HNSCC in phase II clinical trials,( 6 ) we speculated that the mutation status of the TK domain of EGFR and ErbB2 might be helpful for the evaluation of drug response to TKI. Thus we have sequenced the hot‐spot regions in the TK domain of both EGFR and ErbB2 in Japanese HNSCC patients as a first step. However, no activating mutations of EGFR were found. The present study is in agreement with some authors who have also reported the absence or low incidence of EGFR mutations in HNSCC.( 13 , 14 ) It has been noticed that EGFR mutations are also rare or absent in cancers other than lung cancer.( 15 )

Cohen et al. sequenced the EGFR TK domain and exon 20 of ErbB2 in eight gefitinib‐responsive HNSCC patients.( 16 ) Mutations were lacking in EGFR but a single mutation of ErbB2 (V773A) was found. The authors suggested that the response of some HNSCC cases to gefitinib could be due to mutations in ErbB2 rather than EGFR. However, it has been shown that cells expressing ErbB2YVMA (a mutant form of ErbB2) are resistant to EGFR inhibitors but still sensitive to ErbB2 inhibitors.( 17 ) Screening of cancer patients for mutation of EGFR and ErbB2 can aid in defining a group of patients who will benefit mostly from targeting therapy as well as the drug that will give them the best response. However, no activating mutations in either EGFR or ErbB2 in Japanese HNSCC patients were found, indicating that screening of these patients for targeting therapy might not be useful based on their mutation profile.

We also analyzed the mutation status of K‐ras, a membrane‐bound protein that plays a crucial role in transduction of the growth signal downstream of EGFR. Mutations of the RAS family, especially in codons 12, 13, and 61, constitute one of the most common changes in cancer development. However, these mutations differ between cancer types and ethnicity of patients. Although such mutations were relatively low or absent in HNSCC patients from the western world,( 18 ) they were very common in countries like India.( 19 ) In our study, Japanese HNSCC patients lacked K‐ras mutations similar to the western patients. Variation in the incidence of K‐ras mutation might be related to etiological factors rather than ethnicity.

According to Cohen's study, a response to TKI in HNSCC might be detected even in the absence of EGFR mutation; this might be due to the effect of the drug on the wild‐type receptors rather than the mutated ones. Because we detected EGFR expression in all of the tumors and overexpression was detected in a significant proportion (68%), targeting EGFR especially in those patients who overexpress might be of clinical value.

Earlier studies reported a wide range of expression of EGFR ranging from 31 to 100%.( 20 , 21 ) This might be related to the methodology of the IHC techniques. In our study, positive nodal stage and poor tumor differentiation, two parameters of poor patient outcome, were significantly associated with EGFR overexpression. However, in survival analysis, no significant relationship was detected between EGFR expression and survival of the patients.

At present, the most accurate predictor of disease recurrence in patients treated for HNSCC was the extent of regional lymph node metastasis.( 22 ) In line with this, we have shown that nodal stage is the best variable to associate with DFS and OS (P = 0.031 and P = 0.007, respectively). However, the association between EGFR expression and DFS and OS was insignificant (P = 0.292 and P = 0.181 for DFS and OS, respectively). Nevertheless, comparing the mean survival times, there was a trend toward lower survival in cases with EGFR overexpression. Many authors also reported a worse survival outcome for EGFR overexpression.( 21 , 23 ). However, there have been few reports suggesting a better prognosis and survival for patients with high EGFR expression.( 24 , 25 )

In conclusion, although mutation was absent in EGFR in HNSCC, overexpression was detected in the majority of the cases and overexpression was associated with poor tumor differentiation and a positive nodal stage. In the literature, there were also correlations with parameters of poor clinicopathological state, such as high tumor stage, size, and local and distant metastasis, indicating worse survival for patients with EGFR overexpression. These findings lead us to the conclusion that EGFR might be considered as a marker of poor prognosis in HNSCC, and overexpression but not mutation might be the decisive factor for an EGFR‐targeted drug response in these patients. However, more clinical studies are needed to define whether overexpression alone or other molecular changes or both are the decisive factors for the response to these agents in HNSCC.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the surgeons of the Department of Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery of our Hospital. This work was partially supported by Grants‐in‐Aid for scientific research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology (19592109 to HN, 18‐06262 to EG, 17406027 to NN), Seed Innovation Research from the Japan Science and Technology Agency (to MG), the Sumitomo Trust Hasaguchi Memorial Cancer Research Promotion (to MG), and an Astrazeneca Research Grant (to MG).

References

- 1. Hoffman HT, Karnell LH, Funk GF, Robinson RA, Menck HR. The national cancer data base report on cancer of the head and neck. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1998; 124: 951–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cohen S, Carpenter G, King L. Epidermal growth factor receptor–protein kinase interaction: co‐purification of receptor and epidermal growth factor‐enhanced phosphorylation activity. J Biol Chem 1980; 255: 4834–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Karunagaran D, Tzahar E, Beerli RR et al . ErbB‐2 is a common auxiliary subunit of NDF and EGF receptors: implications for breast cancer. EMBO J 1996; 15: 254–64. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lynch TJ, Bell DW, Sordella R et al . Activating mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor underlying responsiveness of non‐small‐cell lung cancer to gefitinib. N Engl J Med 2004; 350: 2129–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Shigematsu H, Lin L, Takahashi T et al . Clinical and biological features associated with epidermal growth factor receptor gene mutations in lung cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst 2005; 97: 339–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cohen EE, Rosen F, Stadler WM et al . Phase II trial of ZD1839 in recurrent or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. J Clin Oncol 2003; 21: 1980–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fisher CJ, Gillett CE, Vojtesek B, Barnes DM, Millis RR. Problems with p53 immunohistochemical staining: the effect of fixation and variation in the methods of evaluation. Br J Cancer 1994; 69: 26–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bauman JE, Eaton KD, Martins RG. Treatment of recurrent squamous cell carcinoma of the skin with cetuximab. Arch Dermatol 2007; 143: 889–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Milas L, Mason KA, Liao Z, Ang KK. Chemoradiotherapy: emerging treatment improvement strategies. Head Neck 2003; 25: 152–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fukui T, Mitsudomi T. Gefitinib and epidermal growth factor receptor gene mutation. Gan Kagaku Ryoho 2007; 34: 1168–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gazdar AF, Shigematsu H, Herz J, Minna JD. Mutations and addiction to EGFR: the Achilles heal of lung cancers? Trends Mol Med 2004; 10: 481–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Stephens P, Hunter C, Bignell G et al . Lung cancer: intragenic ERBB2 kinase mutations in tumors. Nature 2004; 431: 525–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lemos‐González Y, Páez de la Cadena M, Rodríguez‐Berrocal FJ, Rodríguez‐Piñeiro AM, Pallas E, Valverde D. Absence of activating mutations in the EGFR kinase domain in Spanish head and neck cancer patients. Tumour Biol 2007; 28: 273–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Loeffler‐Ragg J, Witsch‐Baumgartner M, Tzankov A et al . Low incidence of mutations in EGFR kinase domain in Caucasian patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Eur J Cancer 2006; 42: 109–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lee JW, Soung YH, Kim SY et al . Absence of EGFR mutation in the kinase domain in common human cancers besides non‐small cell lung cancer. Int J Cancer 2006; 113: 510–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cohen EE, Lingen MW, Martin LE et al . Response of some head and neck cancers to epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors may be linked to mutation of ERBB2 rather than EGFR. Clin Cancer Res 2005; 11: 8105–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wang SE, Narasanna A, Perez‐Torres M et al . HER2 kinase domain mutation results in constitutive phosphorylation and activation of HER2 and EGFR and resistance to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Cancer Cell 2006; 10: 25–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yarbrough WG, Shores C, Witsell DL, Weissler MC, Fidler ME, Gilmer TM. Ras mutations and expression in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Laryngoscope 1994; 104: 1337–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Das N, Majumder J, DasGupta UB. Ras gene mutations in oral cancer in eastern India. Oral Onco 2000; 36: 76–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kusukawa J, Harada H, Shima I, Sasaguri Y, Kameyama T, Morimatsu M. The significance of epidermal growth factor receptor and matrix metalloproteinase‐3 in squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity. Eur J Cancer B Oral Oncol 1996; 32: 217–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Katoh K, Nakanishi Y, Akimoto S, Yoshimura K et al . Correlation between laminin‐5 γ2 chain expression and epidermal growth factor receptor expression and its clinicopathological significance in squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue. Oncology 2002; 62: 318–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rubin Grandis J, Melhem MF, Gooding WE et al . Levels of TGF‐α and EGFR protein in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma and patient survival. J Natl Cancer Inst 1998; 90: 799–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ulanovski D, Stern Y, Roizman P, Shpitzer T, Popovtzer A, Feinmesser R. Expression of EGFR and Cerb‐B2 as prognostic factors in cancer of the tongue. Oral Oncol 2004; 40: 532–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Reimers N, Kasper HU, Weissenborn SJ et al . Combined analysis of HPV‐DNA, p16 and EGFR expression to predict prognosis in oropharyngeal cancer. Int J Cancer 2007; 120: 1731–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Smith BD, Smith GL, Carter D et al . Molecular marker expression in oral and oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2001; 127: 780–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]