Abstract

As there are very few reproducible animal models without conditioning available for the study of human B‐cell‐type Hodgkin's lymphoma (HL), we investigated the ability of HL cells to induce tumors using novel NOD/SCID/γcnull (NOG) mice. Four human Epstein–Barr virus‐negative cell lines (KM‐H2 and L428 originated from B cells, L540 and HDLM2 originated from T cells) were inoculated either subcutaneously in the postauricular region or intravenously in the tail of unmanipulated NOG mice. All cell lines successfully engrafted and produced tumors with infiltration of cells in various organs of all mice. Tumor cells had classical histomorphology as well as expression patterns of the tumor marker CD30, which is a cell surface antigen expressed on HL. Tumor progression in mice inoculated with B‐cell‐type, but not T‐cell‐type, HL cells correlated with an elevation in serum human interleukin‐6 levels. Tumor cells from the mice also retained strong nuclear factor (NF)‐κB DNA binding activity, and the induced NF‐κB components were indistinguishable from those cultured in vitro. The reproducible growth behavior and preservation of characteristic features of both B‐cell‐type and T‐cell‐type HL in the mice suggest that this new xenotransplant model can provide a unique opportunity to understand and investigate the mechanism of pathogenesis and malignant cell growth, and to develop novel anticancer therapies. (Cancer Sci 2005; 96: 466–473)

Hodgkin's disease (HD) is characterized by malignant cells known as multinucleated Reed–Sternberg (RS) and mononucleated Hodgkin (H) cells, which comprise less than 1% of the tumor mass.( 1 ) The remaining cells are benign infiltrating T‐ and B‐lymphocytes, monocytes, eosinophils, macrophages and dendritic cells (DC).( 1 ) Molecular studies have shown that the majority of H and RS cells are derived from the germinal center B lymphocytes and, in rare cases, T lymphocytes.( 2 , 3 ) The tumor necrosis factor receptor (TNFR) family member CD30 has been identified as a cell surface antigen expressed on H and RS cells.( 4 ) HD tumor cells show constitutive nuclear factor (NF)‐κB activity as their characteristic feature,( 5 ) suggesting a role for NF‐κB in the pathogenesis of Hodgkin's lymphoma (HL).

To develop novel therapies and study the pathophysiology of this disease requires a reliable animal model of HL derived from both B and T cells. With the introduction of immunodeficient mice strains carrying the nude, Rag‐1, Rag‐2 or severe combined immunodeficient (SCID) (with or without beige) mutations, xenotransplantation of human tumor cells has become possible.( 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 ) Due to the low engraftment efficiency (23%) of tumor biopsies from HL patients transplanted into SCID mice, tumor cells in the SCID mice have been derived from either Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) superinfected H and RS cells, or from EBV‐infected bystander cells.( 10 , 11 ) However, most cases of HL among young adults in Western countries are EBV negative.( 12 , 13 ) Conventional SCID mice have also been utilized in studies using T‐cell‐type HL.( 14 , 15 ) One approach, which used nude and SCID mice with growth supportive treatments to block innate immunity, succeeded in engrafting B‐cell‐type HL cell lines in less than 50% of inoculated mice.( 16 ) However, some major drawbacks, namely, low engraftment ability, lack of reproducibility, and immunosuppressive requirements (e.g. total body irradiation, anti‐asialo‐GM1 antibody to suppress mouse natural killer (NK) cell activity and growth supportive treatment with pristane), appear to limit the further use of this animal model. Depending on the type of treatment, immunosuppressive conditioning releases a cascade of pro‐inflammatory cytokines.( 17 ) These are known to strongly influence the activity of various cell types of tumor stroma, such as fibroblasts, myoepithelial cells and macrophages, all of which are in close functional interaction with adjacent tumor cells.( 18 , 19 , 20 ) Therefore, such treatments could lead to changes in the relevant histomorphological or functional features of tumors implanted into their respective recipients. Furthermore, immunosuppressive pretreatments, such as irradiation, alter the expression patterns of adhesion molecules in peripheral tissue.( 17 ) This may also influence immune cell migration into those sites and so act as a potential limitation of cellular transfer studies in such models.( 17 )

In the present study we have used the newly developed SCID mouse strain NOD/SCID/γcnull (NOG) in order to overcome such problems.( 21 , 22 , 23 ) This is a unique type of animal, lacking both T and B cells and having defects in NK activity, macrophage function, complement activity and DC function. We report that B‐cell‐type HL cells successfully and efficiently engrafted in all unconditional NOG mice. HL cells inoculated either subcutaneously (s.c.) in the postauricular region or intravenously (i.v.) in the tail of NOG mice also allowed us to study both macroscopic and microscopic mechanisms of tumor growth and the development of new anticancer drugs.

Materials and Methods

Mice and inoculation of cell lines

The NOG mice were obtained from the Central Institute for Experimental Animals (Kawasaki, Japan). All mice were maintained under specific pathogen‐free conditions in the Animal Center of Tokyo Medical and Dental University (Tokyo, Japan). The Ethical Review Committee of the institute approved the experimental protocol.

The L540, HDLM2, KM‐H2 and L428 cell lines (established from HL patients) and the Jurkat T‐cell line were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (Nikken Bio‐laboratory) with 10% or 20% heat‐inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS; JRH Biosciences), 2 mm l‐glutamine, 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 µg/mL streptomycin at 37°C and 5% CO2. Cells were washed twice with serum‐free RPMI 1640 medium and resuspended in medium. Mice were anesthetized with ether and cells were inoculated either i.v. in the tail or s.c. in the postauricular region of NOG mice at a dose of between 1 × 106 and 2 × 107 cells per mouse. KM‐H2 and L540 cells were inoculated into 11 mice (eight s.c. and three i.v.), while three mice were inoculated s.c. with L482 and HDLM2 cells.

Measurement of subcutaneous tumor growth and immunological and histological examinations

Mice were killed 30 or 60 days after inoculation with the different cell lines. We measured the length, width and height of the tumor. Tumor tissues and various organs were collected from the mice and fixed with Streck Tissue Fixative (STF). They were then processed to paraffin wax‐embedded sections for staining with hematoxylin and eosin (HE) and immunostaining. Paraffinized sections of tumors and various organs were deparaffinized and hydrated in xylenes or clearing agents and a graded alcohol series, and were rinsed for 5 min in water. Deparaffinized samples were autoclaved with citrate buffer for 10 min followed by washing for heat‐induced antigen retrieval. They were then incubated with 0.3% methanol for 30 min at room temperature and washed twice with phosphate‐buffered saline (PBS). Immunostaining was carried out for HL cells using a 1:500 dilution of primary mouse monoclonal antibody specific for human CD30 (BerH2; Dako). This was followed by washing in PBS and then incubation with a secondary antibody, biotinylated antimouse IgG. The sections were washed in PBS and again incubated with horseradish peroxidase‐conjugated streptavidin for 30 min at room temperature. Positive staining was visualized after incubation of these samples with a mixture of 0.05% 3,3′‐diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride in 50 mm Tris‐HCl buffer and 0.01% hydrogen peroxide for 5 min. The samples were counterstained with hematoxylin for 15 min, hydrated completely, cleaned in xylene and then mounted.

Measurement of serum human interleukin‐6 and soluble interleukin‐6 receptor levels

Blood collected from the mice hearts was used for the measurement of human interleukin (IL)‐6 and soluble interleukin‐6 receptor (sIL‐6R). The concentrations of IL‐6 and sIL‐6R were determined using an enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay procedure.( 23 ) Microtiter 96‐well plates were coated with 2.5 µg/mL antihuman IL‐6 (IM‐R109; Diaclone Research) and 2.5 µg/mL antihuman IL‐6R (MAB227; R & D Systems) for 2 h at 37°C. They were then washed three times with PBS containing 0.1% Tween‐20 (washing buffer) and blocked with 3% bovine serum albumin at 37°C for 2 h, followed by three washes with the same buffer. The IL‐6 and sIL‐6R standards and the unknown samples were added to the plates and incubated at 37°C for 2 h, before washing. To detect bound IL‐6 and sIL‐6R, biotinylated antihuman IL‐6 (50 ng/mL; 44206; Genzyme‐Techne) and IL‐6R (50 ng/mL; 44227; Genzyme‐Techne) were added and incubated for 2 h at 37°C, followed by washing. Horseradish peroxidase‐conjugated streptavidin was added and incubated at 37°C for 30 min, followed by three washes with the PBS washing buffer. Peroxidase activity was determined using 3,3′,5,5′‐tetramethylbenzidine as a substrate. The reaction was stopped with 1.8 M H2SO4, and absorbance was measured at 450 nm.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay

Nuclear extract preparations and electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA) were carried out as described previously.( 22 , 23 ) The wild‐type κB probe used was a double‐stranded oligonucleotide (5′‐AGCTTCAACAGAGGGGACTTTCCGAGAGGCTCGA‐3′) containing a single κB motif derived from murine immunoglobulin κ light chain enhancer. To identify the subunits constituting the NF‐κB complexes, specific antibodies against p50 and c‐Rel (both from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), p65 (1226) and RelB (13482) (both from Dr Nancy Rice and Dr A. Israel, Institute Pasteur de Paris, France) and p52 (1319; Upstate Biotechnology) were used.

Results

Successful engraftment and rapid tumor formation of Hodgkin's lymphoma cells in NOG mice without changes in histomorphology or tumor marker expression

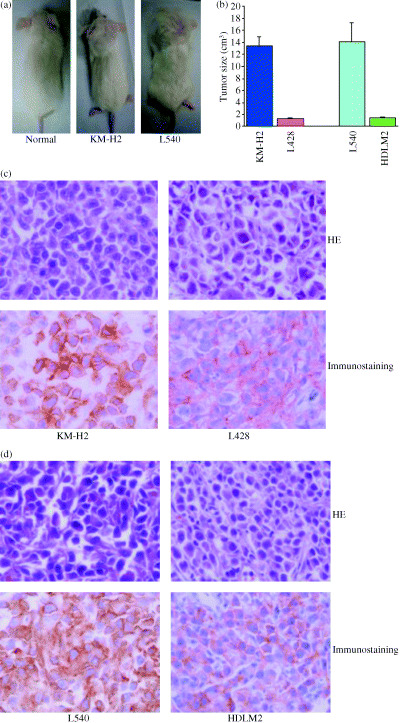

To investigate the in vivo growth of tumors, HL cell lines (KM‐H2, L428, L540 and HDLM2) were inoculated either s.c. in the postauricular region or i.v. in the tail of NOG mice (Table 1). Mice inoculated s.c. with cell lines KM‐H2 and L428 (derived from B cells) produced a visible large tumor within 60 days, while i.v.‐inoculated mice were found to efficiently engraft tumor cells in various organs. Mice inoculated with the L540 cell line (originated from T cells) did so 30 days after inoculation. The T‐cell‐derived HDLM2 cell line produced a progressively growing tumor 30 days after s.c. inoculation, while i.v.‐inoculated mice did so after 60 days. Most notable was the fact that the cell lines KM‐H2 and L540 inoculated s.c. were very efficient in the formation of a large tumor (Fig. 1a). The average tumor sizes in NOG mice inoculated s.c. with HL cells are shown in Fig. 1b (KM‐H2 = 13.42 cm3 and L428 = 1.28 cm3, 60 days after inoculation; L540 = 14.21 cm3 and HDLM2 = 1.54 cm3, 30 days after inoculation). There were no secondary tumors in the mice with s.c. transplantation, and microscopic investigations revealed tumor cells in various organs of the mice. Mice inoculated i.v. with the L428 and L540 cell lines had visible tumor masses in the liver, but not in other organs. The characteristic features and tumor markers of HL cells are given in Table 1.( 4 , 5 , 24 , 25 , 26 ) Among the tumor markers, CD30 is a primary diagnostic marker of HL and is expressed on both primary and cultured H and RS cells.( 4 ) To test whether tumors in NOG mice maintained their original histomorphology and expression patterns of tumor markers, we carried out HE staining and immunostaining of tumor tissues obtained from mice inoculated with KM‐H2, L428, L540 and HDLM2 cells. Histological and immunological analyses revealed that in vivo tumor cells did preserve the original tumor morphology, and they did express human CD30 (Fig. 1c,d). These results showed that all HL cell lines inoculated into NOG mice were able to produce tumors very efficiently, irrespective of whether they were originated from B or T cells. This extremely rapid tumor formation in all of the mice is one of the hallmarks of our animal model, without changes in histomorphology or tumor marker expression.

Table 1.

In vitro and in vivo characteristics of Hodgkin's lymphoma (HL) cell lines in NOD/SCID/γcnull mice

| Cell line † | Origin/EBV status ‡ | In vitro characteristic | No. cells inoculated/mouse (106) ‡‡ | Inoculation route §§ | Time of killing (no. days after inoculation) | No. mice with tumor/no. mice inoculated ¶¶ | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor marker § | IL‐6 ¶ | NF‐κB †† | ||||||||||||

| CD2 | CD3 | CD15 | CD19 | CD21 | CD25 | CD30 | ||||||||

| KM‐H2 | B/– | – | – | + | – | + | – | + | +++ | +++ | 20 | s.c. | 60 | 08/08 |

| KM‐H2 | B/– | – | – | + | – | + | – | + | +++ | +++ | 2 | i.v. | 60 | 06/06 |

| L428 | B/– | – | – | + | – | + | – | + | +++ | +++ | 20 | s.c. | 60 | 03/03 |

| L428 | B/– | – | – | + | – | + | – | + | +++ | +++ | 2 | i.v. | 60 | 03/03 |

| L540 | T/– | + | – | + | – | – | + | + | – | +++ | 20 | s.c. | 30 | 08/08 |

| L540 | T/– | + | – | + | – | – | + | + | – | +++ | 1 | i.v. | 30 | 03/03 |

| HDLM2 | T/– | + | – | + | – | – | + | + | + | +++ | 20 | s.c. | 30 | 03/03 |

| HDLM2 | T/– | + | – | + | – | – | + | + | + | +++ | 2 | i.v. | 60 | 0/03 |

Cell lines KM‐H2 and L428 were established from B‐cell‐type HL patients, whereas L540 and HDLM2 were from T‐cell‐type HL patients.

All of these cell lines are devoid of Epstein–Barr virus (EBV).( 12 )

T‐cell and B‐cell lineage differences and tumor markers are described on the DSMZ home page.( 30 ) +, Positive; –, negative.

Interleukin (IL)‐6 was measured by enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay. +++, Strongly positive; +, weakly positive; –, not detected.

Nuclear factor (NF)‐κB DNA binding activity was detected by electrophoretic mobility shift assay. +++, Strongly positive.

Mice were injected with 1 × 106−2 × 107 cells per mouse.

§§ i.v., intravenous; s.c., subcutaneous.

¶¶ No. animals in which visible tumor developed.

Figure 1.

Growth, infiltration and tumor markers of Hodgkin's lymphoma (HL) cells in NOD/SCID/γcnull mice. (a) Photograph of a normal mouse (left panel), and mice inoculated with KM‐H2 (middle panel) or L540 (right panel) cells subcutaneously in the postauricular region. (b) Subcutaneous tumor growth of mice inoculated with various HL cell lines. (c,d) Hematoxylin and eosin and immunohistochemical staining of tumor tissue from KM‐H2‐, L428‐, L540‐ and HDLM2‐injected mice. Upper panel represents HE staining. Immunohistochemical staining was conducted using antihuman CD30 (lower panel). Left and right panels represent results with (c) KM‐H2 and L428, and (d) L540 and HDLM2 (magnification, ×60).

Infiltration of Hodgkin's lymphoma cells into various organs of NOG mice

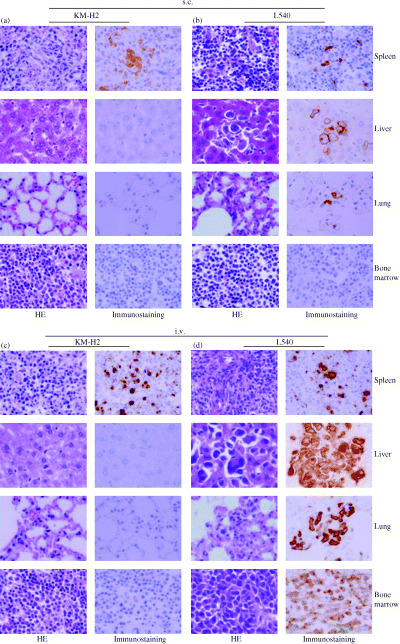

To assess the tissue distribution of HL cells, we carried out histological examinations of the different organs of NOG mice after inoculation of the HL cell lines (Table 2). Proliferation and infiltration of tumor cells were found in the primary tumor, regional cervical lymph node and spleen, but not in the liver, lung or bone marrow of NOG mice inoculated s.c. with the KM‐H2 and L428. We found that mice inoculated i.v. with KM‐H2 cells exhibited infiltration in the spleen, but not in the lung, liver, lymph node or bone marrow, while L428 cells showed infiltration in the spleen, liver and lung. L540 cells inoculated s.c. in mice infiltrated the primary tumor, regional cervical lymph node, liver, lung and spleen, but HDLM2 were found to infiltrate the primary tumor and regional cervical lymph node only. We also found that mice inoculated i.v. with L540 cells exhibited infiltration in the liver, lung, spleen and bone marrow, but HDLM2 cells showed infiltration in the liver and spleen only. HE and immunostaining showed a degree of infiltration of tumor cells in the various organs of mice inoculated with KM‐H2 and L‐540 (Fig. 2). Interestingly, i.v.‐inoculated tumor cells appeared to infiltrate various organs of mice more aggressively than s.c.‐inoculated tumor cells. These data suggest that HL cell lines could invade different organs of NOG mice in a manner similar to HL cells in human patients.

Table 2.

Infiltration of Hodgkin's lymphoma (HL) cells into various organs of NOD/SCID/γcnull (NOG) mice

| Cell line | Inoculation route | Infiltration of HL cells into | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regional lymph node | Liver | Lung | Spleen | Bone marrow | ||

| KM‐H2 | s.c. | +++ | – | – | + | – |

| L428 | s.c. | +++ | – | – | + | – |

| L540 | s.c. | +++ | + | + | + | – |

| HDLM2 | s.c. | +++ | – | – | – | – |

| KM‐H2 | i.v. | – | – | – | +++ | – |

| L428 | i.v. | – | +++ | + | ++ | NE |

| L540 | i.v. | – | +++ | ++ | ++ | +++ |

| HDLM2 | i.v. | – | + | – | +++ | NE |

All cell lines were inoculated either subcutaneously (s.c.) in the postauricular region or intravenously (i.v.) in the tail of NOG mice. Tumor tissue and organ samples were examined by histological analysis. +, Slight infiltration; ++, marked infiltration; +++, massive infiltration; –, no infiltration; NE, not examined.

Figure 2.

Infiltration of Hodgkin's lymphoma (HL) cells in various organs of NOD/SCID/γcnull mice. (a–d) Histological analysis of spleen, liver, lung and bone marrow of mice inoculated with KM‐H2 and L540 cells either (a,b) subcutaneously or (c,d) intravenously. Immunohistochemical staining was conducted using antihuman CD30. (a,c) KM‐H2‐inoculated mice; (b,d) L540‐inoculated mice. Left and right panels of all figures represent hematoxylin and eosin staining, and immunostaining, respectively (magnification, ×60).

Serum soluble human interleukin‐6 level, an indicator of B‐cell‐type Hodgkin's lymphoma cell proliferation in NOG mice

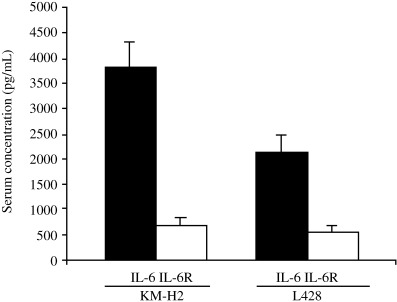

Previous studies in HD have demonstrated the association of elevated serum levels and expression of IL‐6 with unfavorable prognoses, as well as associating advanced stage and presence of ‘B’ symptoms with poor survival.( 24 , 27 ) Therefore, serum human IL‐6 and IL‐6R levels were measured in the tumor‐bearing mice. IL‐6 (mean values: KM‐H2 = 3716.67 pg/mL and L428 = 2149.31 pg/mL) was markedly elevated in mice that were found to be successfully engrafted with cell lines derived from B‐cell‐type HL, but sIL‐6R was not (Fig. 3). There was no correlation between tumor formation and increased serum levels of IL‐6 and sIL‐6R in mice inoculated with cell lines derived from T‐cell‐type HL, even though one cell line (HDLM2) was weakly positive for IL‐6 in the culture supernatant. IL‐6 levels were detected in the in vitro culture supernatants of KM‐H2, L428 and HDLM2 cells (Table 1), but sIL‐6R was only weakly positive in KM‐H2 and HDLM2 culture supernatants (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Serum levels of interleukin (IL)‐6 and soluble interleukin‐6 receptor (sIL‐6R) in NOD/SCID/γcnull mice. Enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assays was carried out using sera from mice inoculated with KM‐H2 and L428 cells. Data represent the mean ± SD from 14 KM‐H2 and six L428 tumor‐bearing mice.

Nuclear factor‐κB binding activity of Hodgkin's lymphoma cells inoculated in NOG mice

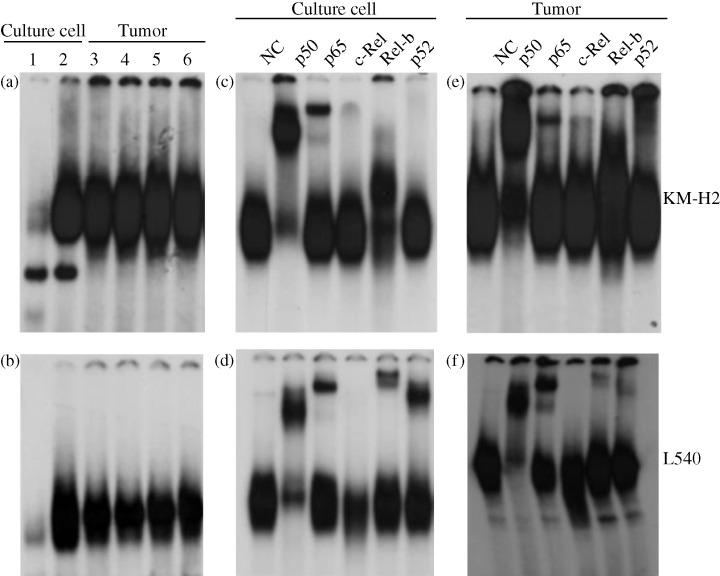

Despite the diversity in clinical manifestations of HL, strong and constitutive NF‐κB activation is a unique and common characteristic of HL cells in patients.( 5 , 25 ) To ascertain the constitutive NF‐κB activity of HL tumor cells before and after inoculation, we used EMSA. Tumor cells from mice inoculated with KM‐H2 and L540 sustained a strong NF‐κB DNA binding activity comparable to that observed in in vitro‐cultured cells (Fig. 4a,b). Supershift assays were carried out with nuclear extracts of tumor tissues in the absence or presence of antibodies that specifically recognize the following members of the NF‐κB family: p50, p65, c‐Rel, RelB and p52. The band was completely shifted by p50 and p65 and partially shifted by RelB both in vitro and in vivo in cells of KM‐H2 (Fig. 4c,e). It was also shifted by p50, p65, p52 and RelB both in vitro and in vivo in cells of L540 (Fig. 4d,f). These results demonstrate that the NF‐κB complexes contained p50, p65 and RelB in HL cells. They also suggest that constitutive NF‐κB activity is required for HL cell growth in NOG mice, which may offer an effective therapeutic target for the treatment of HD.

Figure 4.

Constitutive nuclear factor (NF)‐κB binding activity of L540 and KM‐H2 cells in NOD/SCID/γcnull mice. (a,b) Electrophoretic mobility shift assay analysis of NF‐κB binding activity of the KM‐H2 and L540 cells obtained from in vitro‐cultured cells or in vivo tumors from mice. Nuclear extracts (5 µg) were treated with 32P‐labeled wild‐type NF‐κB oligonucleotides. Lane 1 represents the negative control using Jurkat, and lane 2 represents in vitro‐cultured KM‐H2 and L540 cells. Lanes 3–6 show in vivo NF‐κB DNA binding of KM‐H2 and L540 cells from four different tumor‐bearing mice. (c–f) Analysis of the NF‐κB components of KM‐H2 and L540 cells by supershift assay. Supershift using antibodies specific to the p50, p65, c‐Rel, RelB and p52 subunits of NF‐κB was conducted both (c,d) in vitro and (e,f) in vivo. Upper and lower panels represent the results of KM‐H2 and L540, respectively. NC, negative control.

Discussion

For the development of new therapies for treating HL, it is essential to establish an effective animal model. Currently, there are several available animal models, the majority of which use SCID mice.( 14 , 16 ) These models, however, have their drawbacks. Tumor biopsies from HL patients as well as HL cell lines transplanted into SCID mice show a low level of engraftment efficiency in SCID mice.( 10 , 16 ) The differing behaviors of HL cells in terms of tumor formation in the different types of SCID mice are dependent on the host's immune system. NK cells and DC may play an important role in the rejection of implanted tissue or cells in SCID mice.( 28 , 29 ) Because B‐cell‐derived major type HL showed very low engraftment efficiency in conventional SCID mice, we attempted to establish new animal models in NOG mice using HL cell lines, especially those derived from B cells. In the present study, HL cell lines inoculated s.c. in the postauricular region over the skeleton of mice permitted us to observe tumor growth macroscopically and to measure tumor size in a relatively short period of time (Table 1; Fig. 1a). By measuring the tumor size macroscopically, it is possible to compare the growth ability of inoculated tumor cells between control mice and mice treated with drugs or other therapies. It is of particular importance that i.v.‐inoculated HL cells were found to infiltrate various organs more aggressively than s.c.‐inoculated HL cells.

The circulating level of IL‐6 may act as a useful prognostic marker, as high serum IL‐6 concentrations are associated with specific disease characteristics, including several adverse prognostic features such as the presence of ‘B’ symptoms and reduced survival.( 24 ) IL‐6 production was detected in the in vitro culture supernatants of the HL cell lines KM‐H2, L428 and HDLM2 (Table 1). Our results also indicate that the presence of a high level of human IL‐6 in mouse serum is linked to the development of B‐cell‐type HL tumor growth and clinical signs of death. Expression of the tumor marker CD30 and NF‐κB DNA binding activity were indispensable for HL cell growth and maintenance of phenotype, irrespective of whether they were originated from B or T cells.( 4 , 5 , 25 , 26 ) The implantation procedure was performed easily without manipulating mice by any means, such as irradiation or antibodies. The engraftment was highly efficient, and CD30 expression and NF‐κB DNA binding activity were strong and unaltered in tumor cells. However, there was no correlation between tumor formation of HL cell lines in mice and IL‐6 production and high NF‐κB activity (Table 1).

In summary, the reproducible growth behavior and preservation of characteristic features of HL cells derived from both B‐cell‐type and T‐cell‐type cells suggest that the NOG mice model system described in the present study may provide a unique opportunity to understand and investigate the mechanism of pathogenesis and malignant cell growth of HL, and to develop novel therapeutic regimens.

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Tanaka, M. Aoki and S. Yamaoka of the Department of Molecular Virology, S. Ichinose of the Instrumental Analysis Research Center and S. Endo of Animal Research Center, Tokyo Medical and Dental University (Tokyo, Japan), and Peter J. Richard of Cardiff University (Cardiff, UK), for their advice and assistance with the experiments. We also thank Y. Sato of the National Institute of Infectious Diseases (Tokyo, Japan) for her excellent technical assistance. The present work was supported by grants from the Ministry of Education, Science and Culture, the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare and Human Health Science of Japan.

References

- 1. Kadin ME. Pathology of Hodgkin's disease. Curr Opin Oncol 1994; 6: 456–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Stein H, Hummel M. Cellular origin and clonality of classic Hodgkin's lymphoma: immunophenotypic and molecular studies. Semin Hematol 1999; 3: 233–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Staudt LM. The molecular and cellular origins of Hodgkin's disease. J Exp Med 2000; 191: 207–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Schwab U, Stein H, Gerdes J et al. Production of a monoclonal antibody specific for Hodgkin's and Sternberg–Reed cells of Hodgkin's disease and a subset of normal lymphoid cells. Nature 1982; 299: 65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bargou RC, Leng C, Krappmann D et al. High‐level nuclear NF‐κB and Oct‐2 are a common feature of cultured Hodgkin's and Reed–Sternberg cells. Blood 1996; 87: 4340–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sharkey F, Fogh J. Metastasis of human tumors in athymic nude mice. Int J Cancer 1979; 24: 733–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Giovanella BC, Fough J. The nude mice in cancer research. Adv Cancer Res 1985; 44: 69–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zietman AL, Sugiyama E, Ramsey JR et al. A comparative study on the xenotransplantability of human solid tumors into mice with different genetic immune deficiencies. Int J Cancer 1991; 47: 759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Garofalo A, Chirivi RGS, Scanziani E, Mayo JG, Vecchi A, Giavazzi P. A comparative study on the metastatic behavior of human tumors in nude, beige/nude/xid and severe combined immunodeficient mice. Invasion Metastasis 1993; 3: 82–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kapp U, Wolf J, Hummel M et al. Hodgkin's Lymphoma‐derived tissue serially transplanted into severe combined immunodeficient mice. Blood 1993; 82: 1247–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Armbinder RF, Weiss LM. Association of Epstein–Barr virus with Hodgkin's disease. In: Mauch PM, Armitage JO, Diehl V, Hoppe RT, Weiss LM, eds. Hodgkin's Disease. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, 1999; 79–98. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Drexler HG. Recent results on the biology of Hodgkin's and Reed–Sternberg cells. II. Continuous cell lines. Leuk Lymphoma 1993; 9: 1–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jungnickel B, Staratschek‐Jox A, Brauninger A et al. Clonal deleterious mutations in the IκBα gene in the malignant cells in Hodgkin's lymphoma. J Exp Med 2000; 191: 395–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mathas S, Lietz A, Janz M et al. Inhibition of NF‐κB essentially contributes to arsenic‐induced apoptosis. Blood 2003; 102: 1028–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Francisco JA, Cerveny CG, Meyer DL et al. cAC10‐vcMMAE, an anti‐CD30‐monomethyl auristatin E conjugate with potent and selective antitumor activity. Blood 2003; 102: 1458–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kalle CV, Wolf J, Becker A et al. Growth of Hodgkin cell lines in severely combined immunodeficient mice. Int J Cancer 1992; 52: 887–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Quarmby S, Kumar S, Kumar P. Radiation‐induced normal tissue injury: role of adhesion molecules in leukocyte–endothelial cell interactions. Int J Cancer 1999; 82: 385–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Adam L, Crepin M, Lelong J, Spanakis E, Israel L. Selective interactions between mammary epithelial cells and fibroblast in co‐culture. Int J Cancer 1994; 59: 262–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sawhney N, Garrahan N, Douglas‐Jones A, Williams ED. Epithelial–stromal interaction in tumors. A morphologic study of fibroepithelial tumors of the breast. Cancer 1992; 70: 2115–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Van Roosendaal C, Van Ooijen B, Klijn JG et al. Stromal influences on breast cancer cell growth. Br J Cancer 1992; 65: 77–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ito M, Hiramatsu H, Kobayashi K et al. NOD/SCID/γcnull mouse: An excellent recipient mouse model for engraftment of human cells. Blood 2002; 100: 3175–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dewan MZ, Terashima K, Teruishi M et al. Rapid tumor formation of HTLV‐1‐infected cell lines in novel NOD‐SCID/γcnull mice: suppression by an inhibitor against NF‐κB. J Virol 2003; 77: 5286–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Dewan MZ, Watanabe M, Terashima K et al. Prompt tumor formation and maintenance of constitutive NF‐κB activity of multiple myeloma cells in NOD/SCID/γcnull mice. Cancer Sci 2004; 95: 564–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kurzrock R, Redman J, Cabanillas F, Jones D, Rothberg J, Talpaz M. Serum interleukin 6 levels are elevated in lymphoma patients and correlate with survival in advanced Hodgkin's disease and with B symptoms. Cancer Res 1993; 53: 2118–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bargou RC, Emmerich F, Krappmann D et al. Constitutive nuclear factor‐κB‐RelA activation is required for proliferation and survival of Hodgkin's disease tumor cells. J Clin Invest 1997; 100: 2961–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nonaka M, Horie R, Itoh K, Watanabe T, Yamamoto N, Yamaoka S. Aberrant NF‐κB2/p52 expression in Hodgkin/Reed–Sternberg cells and CD30‐transformed rat fibroblasts. Oncogene 2005; 24: 3976–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Reymolds GM, Billingham LJ, Gray LJ et al. Interleukin 6 expression by Hodgkin/Reed–Sternberg cells is associated with the presence of ‘B’ symptoms and failure to achieve complete remission in patients with advanced Hodgkin's disease. Br J Haematol 2002; 118: 195–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Feuer G, Stewart SA, Baird SM, Lee F, Feuer R, Chen ISY. Potential role of natural killer cells in controlling tumorigenesis by human T‐cell leukemia viruses. J Virol 1994; 69: 1328–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lechler R, Ng WF, Steinman RM. Dendritic cells in transplantation – friends or foes? Immunity 2001; 14: 357–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. DSMZ [website on the internet]. Human and Animal Cell Cultures/Index. 2005. [Cited June 2005] Available from URL: http://www.dsmz.de/mutz/mutzinde.htm