Abstract

Ten novel human pancreatic carcinoma cell lines (Sui65 through Sui74) were established from a transplantable pancreatic carcinoma cell line. All the cell lines resembled the original clinical carcinoma in terms of the morphological and biological features, presenting with genetic alterations such as point mutations of K‐ras and p53, attenuation or lack of SMAD4 and p16 and other relevant cellular characteristics. Using this panel, we evaluated the effects of 5‐FU in suppressing the proliferation of pancreatic carcinoma cells. When tested in vitro, although Sui72 was highly susceptible to 5‐FU, the other cell lines were found to be resistant to the drug. When Sui72 and Sui70 were implanted subcutaneously in SCID mice followed by treatment with 5‐FU, the drug was found to be effective against Sui72 but not Sui70, consistent with the results in vitro. In order to identify the molecular determinant for high sensitivity of Sui72 to 5‐FU, we examined the mRNA expression levels of the metabolic enzymes of 5‐FU. Decreased expression of DPYD was observed in Sui72 as compared with other cell lines (0.1 versus 0.6 ± 0.5, 0.1‐fold).

It is believed that the novel cell lines established in the present study will be useful for analyzing the pattern of progression of pancreatic cancer and for evaluating the efficacy of anticancer agents. (Cancer Sci 2008; 99: 1859–1864)

- Abbreviations: i.p.

intraperitoneal

- s.c.

subcutaneous

- TPA

tissue polypeptide antigen

- 5‐FU

5‐fluorouracil

- SCID

severe combined immunodeficiency.

Pancreatic cancer is an intractable cancer with a prognosis poorer than that of any other cancer of the gastrointestinal tract. In Japan, the 5‐year survival rate of patients with pancreatic cancer is 5.5%, which is extremely low as compared with that of patients with colorectal cancer (64.6%), gastric cancer (58.8%) or even hepatic cancer (17.1%).( 1 , 2 ) The number of patients with this cancer has been increasing significantly in recent years, and the mean life expectancy of patients with this cancer is only about 1.5 years. Pancreatic cancer, often characterized by pain, jaundice and digestive dysfunction, causes much pain and stress to the patient. These characteristics make this cancer an important open issue in medicine and healthcare. Currently, no valid clinical means are available for the prevention, diagnosis or treatment of this cancer. Treatment of pancreatic cancer with local therapy alone, that is surgical resection and radiotherapy, has limitations, and chemotherapy needs to be considered.( 2 ) In the past, various adjuvant chemotherapy regimes, primarily based on 5‐FU, have been attempted;( 3 , 4 , 5 ) however, no effective therapy has as yet been established for pancreatic cancer.

In recent years, close attention has been paid to the development of cancer treatment methods based on information about the molecular mechanism of onset and progression of cancer.( 2 , 6 , 7 ) Thus, exploration of molecular markers and target molecules for treatment is expected to play a key role in cancer management. For this kind of preclinical research, in particular, for evaluation of the efficacy of molecule‐targeted drugs, the development of a panel of cultured cells derived from clinical cancer specimens is indispensable. To date, a number of cell lines derived from human pancreatic cancer have been established ( 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 ) and have contributed greatly to advancing cancer research( 15 , 16 ) in terms of analysis of biological features and evaluation of the efficacy of anticancer agents. However, after multiple passages, some of these cell lines lose their original features (e.g. histopathological characteristics of the tumor formed after implantation, etc.).

The present study was undertaken to establish 10 novel cell lines derived from human pancreatic carcinoma that would reliably reflect the clinical features of pancreatic carcinoma. We investigated the proliferative characteristics and genetic alterations in these cell lines, then, using the panel of cell lines, we evaluated the efficacy of conventional 5‐FU‐based chemotherapy against pancreatic cancer and attempted to elucidate the determinants of sensitivity of these pancreatic cancer cell lines to 5‐FU‐based anticancer agents.

Materials and Methods

Establishment of the cell lines. All the cell lines were established in vitro from xenotransplantable tumors (taco series) originating from primary or metastatic human pancreatic cancer (Table 1) (T. Oda and A. Ochiai, unpublished data). The cell lines were established by s.c. back transplantation of the primary tumor for the 8th transplant generation, then tumors were removed for in vitro cultivation. Fresh tumor specimens obtained under sterile conditions were washed five times in Roswell Park Memorial Institute medium (RPMI)‐1640 containing streptomycin (500 µg/mL) and penicillin (500 IU/mL). The tumor tissue specimens were trimmed of fat and necrotic materials and minced with a scalpel. The tissue pieces were transferred together with Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) + Ham's F12 + 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS), at 10–15 fragments per dish, to 60‐mm culture dishes.( 17 ) The dishes were left undisturbed for 24 h at 37°C in a 5% CO2/95% air atmosphere. The medium was composed of Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM)/Ham's F12 medium (1:1) supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA), 100 IU/mL penicillin G sodium, and 100 mg/mL streptomycin sulfate (Immuno‐Biological Laboratories [IBL], Fujioka, Japan). After 48 h, the medium was replaced by RPMI‐1640 medium (IBL, Fujioka, Japan) supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 IU/mL penicillin G sodium and 100 mg/mL streptomycin sulfate. The dishes containing the tissue fragments were observed weekly under an inverted phase microscope. The dishes were initially trypsinized (0.05% trypsin and 0.02% ethylenediametetraacetic acid [EDTA]) to selectively remove overgrowing fibroblasts. In addition, we also attempted to remove the fibroblasts mechanically and transfer only the tumor cells. Half of the medium was changed every 4–6 days. The cultures were first split after 3–8 months of cultivation, and the cells were passaged thereafter at a 1:10 or 1:20 ratio.( 18 ) They were then judged, established and designated (Table 1). All of the cell lines were routinely tested for Mycoplasma using a PCR Mycoplasma Detection kit (Takara, Kyoto, Japan), and no contamination was detected. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all of the patients from whom the tumor specimens were obtained. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board of the National Cancer Center (approved number: 17–43).

Table 1.

Establishment of ten human pancreatic cancer cell lines from the xenotransplantable tumors

| Cell line | Source | Origin | Histology | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| xenograft tumor | Age/sex | Source (TNM) | ||

| Sui65 | taco‐1 | 63/F | Peritoneum (metastatic focus) | Tubular adenocarcinoma c/w meta |

| Sui66 | taco‐2 | 74/M | Pancreas | Tubular adenocarcinoma |

| Sui67 | taco‐4 | 73/F | Pancreas | Tubular adenocarcinoma |

| Sui68 | taco‐5 | 53/M | Pancreas | Adenocarcinoma |

| Sui69 | taco‐6 | 54/M | Pancreas | Tubular adenocarcinoma |

| Sui70 | taco‐7 | 53/M | Pancreas | Adenocarcinoma |

| Sui71 | taco‐12 | 65/M | Liver (metastatic focus) | Adenocarcinoma c/w meta |

| Sui72 | taco‐13 | 76/F | Pancreas | Tubular adenocarcinoma |

| Sui73 | taco‐15 | 65/F | Pancreas | Tubular adenocarcinoma |

| Sui74 | taco‐16 | 72/F | Pancreas | Adenocarcinoma |

Animal experimentation. The animal experiment protocols were approved by the Committee for Ethics in Animal Experimentation, and the experiments were conducted in accordance with the Guideline for Animal Experiments of the National Cancer Center. Female SCID mice (C.B.17/Icr Jcl‐scid) were purchased from CLEA Japan (Tokyo, Japan), and maintained under specific‐pathogen‐free conditions. Six‐ to 8‐week‐old mice were used for this experiment. The mice were housed in filter‐protected cages and reared on sterile water. The ambient light was controlled to provide regular 12‐h light : 12‐h dark cycles.

Western blot analysis. SMAD4 and p16 expression was examined in all the cell lines using Western blotting.( 19 ) An osteosarcoma (SaOs2) and a human embryonic kidney (293) cell line were used as positive controls for p16 and SMAD4, respectively. Monoclonal mouse antihuman antibodies to DPC4/Smad 4 (cloneB8, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) and to p16 (clone G175‐405, PharMingen, San Diego, CA, USA) were used.

Therapeutic studies with 5‐fluorouracil (5‐FU). S.C. implantation of 5 × 105 cultured cells suspended in 0.1 mL RPMI‐1640 medium was conducted in 6‐week‐old female SCID mice. To evaluate the antitumor activity, 3 days after the tumor cell implantation, the mice were divided into three groups of six mice each according to the tumor volume on Day 0. The experimental mice were divided into a control group that received vehicle alone (saline), and experimental groups that received i.p. inoculation of different doses of the drug (50 and 100 mg/kg/head). On Days 3, 10 and 17, tumor‐bearing mice received an i.p. injection of 5‐FU. 5‐FU was purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA) and dissolved in saline before being injected. Tumor growth was measured weekly, in terms of the tumor diameter, with calipers. At appropriate intervals, or when moribund, the mice were sacrificed and the tissues were examined macroscopically for metastasis in various organs and then processed for histological examination, as described previously.( 20 )

Direct sequencing. Samples from the cell lines were analyzed for the presence of mutations in exon 1 of the K‐ras (Kirsten rat sarcoma‐2 viral oncogene homolog) gene and exons 5–8 of the p53 gene by direct sequencing of the PCR‐amplified DNA fragments. PCR and direct sequencing were performed as described previously( 21 ) using minor modifications.

Real‐time reverse‐transcription polymerase chain reaction. RNA derived from each cell line was converted to complementary DNA using a GeneAmp RNA PCR Core kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Real‐time reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT‐PCR) were performed using Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) and the 7900HT Fast Real‐time PCR system (Applied Biosystems). The PCR conditions were as follows: one cycle of denaturation at 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles at 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 60 s. Obtained data was normalized relative to glyceraldehyde‐3‐phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPD) expression. The following primers were used: DHFR‐FW: 5′‐GCA AAT AAA GTA GAC ATG GTC TGG A‐3′; DHFR‐RW: 5′‐AGT TTA AGA TGG CCT GGG TGA‐3′; FPGS‐FW: 5′‐TCT GCC CTA ACC TGA CAG AGG TG‐3′; FPGS‐RW: 5′‐TCG TCC AGG TGG TTC CAG TG‐3′; TP‐FW: 5′‐GAG GCA CCT TGG ATA AGC TGG A‐3′; TP‐RW: 5′‐GCT GTC ACA TCT CTG GCT GCA TA‐3′; UPP1‐FW: 5′‐GTA CTA TGC CCG GTG CTC CAA C‐3′; UPP1‐RW: 5′‐CTC TGC CTT GAA GCA GGA ATC CA‐3′; PRPS1‐FW: 5′‐AAC GCA TGC TTT GAG GCA GTA GTA G‐3′; PRPS1‐RW: 5′‐CTG ATG GCT TCT GCA AGG ATC ATA‐3′; DPYD‐FW: 5′‐CAA CGT AGA GCA AGT TGT GGC TAT G‐3′; DPYD‐RW: 5′‐AGT CGA CAA TAG GGC AAA CAC TGA‐3′; TYMS‐FW: 5′‐ATC ATC ATG TGC GCT TGG AAT C‐3′; TYMS‐RW: 5′‐TGT TCA CCA CAT AGA ACT GGC AGA G‐3′; OPRT‐FW: 5′‐CTG GCT CCC GAG TAA GCA TGA‐3′; OPRT‐RW: 5′‐CTG CTG AGA TTA TGC CAC GAC CTA‐3′; TK1‐FW: 5′‐ATT CTC GGG CCG ATG TTC TC‐3′; TK1‐RW: 5′‐GCG AGT GTC TTT GGC ATA CTT GA‐3′; MTHFR‐FW: 5′‐GGA CAC TAC CTC ACC TGC CAG TAT C‐3′; MTHFR‐RW: 5′‐CCA GAA GCA GTT AGT TCT GAC ACC A‐3′; NP‐FW: 5′‐CAA CCT ACC TGG TTT CAG TGG TCA‐3′; NP‐RW: 5′‐CCG GTC GTA GGC ATC AGA CA‐3′; UCK2‐FW: 5′‐TTC GTC AAG CCT GCC TTT GAG‐3′; UCK2‐RW: 5′‐TGG ATG TGC TGC ACG ATG AG‐3′; GAPD‐FW: 5′‐GCA CCG TCA AGG CTG AGA AC‐3′; GAPD‐RW: 5′‐ATG GTG GTG AAG ACG CCA GT‐3′.

Results

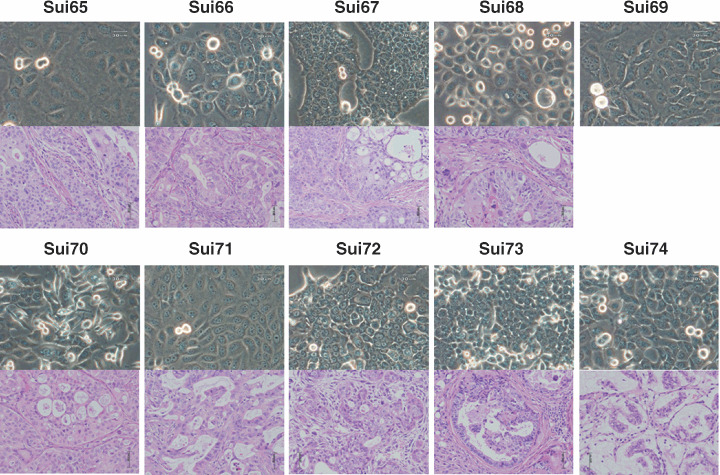

Establishment and characterization of pancreatic cancer cell lines. Ten cell lines derived from human pancreatic cancers (Sui65, Sui66, Sui67, Sui68, Sui69, Sui70, Sui71, Sui72, Sui73 and Sui74) were newly established in the present study (Table 1). All the cell lines formed mono‐layered sheets with clustering on confluence (Fig. 1 upper column). These cell lines exhibited the typical morphologic features of epithelial cells, characterized by sheets of polygonal cells in a pavement‐like arrangement. The Sui65, 67, 68, 70 and 71 cell lines were found to secrete carbohydrate antigen19‐9 (CA19‐9), the concentration of which in the culture supernatants varied from 69 to 450 units/mL (Table 2). Production of TPA was also detected from all of the cell lines. The doubling times of the cell lines varied from approximately 20.8 to 55.2 h in the RPMI‐1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS. When injected s.c., all of the cultured cell lines established from human pancreatic cancers, except for Sui69, survived and showed tumorigenicity (Fig. 1, lower column). These biological properties are summarized in Table 2. All the tumorigenic cell lines were also found to be strictly anchorage independent (60–90% efficiency).

Figure 1.

Phase‐contrast micrographs of the 10 established cell lines in this study (Sui65‐Sui74) at the 25–30th passage (upper column). Original magnification, ×200. Histological section of a tumor established by s.c. injection of one of the cell lines into a SCID mouse (lower column). HE Stain, ×400.

Table 2.

Biological characterization of newly established human pancreatic cancer cell lines

| Cell line | Histological typing † | Growth ‡ | Tumor marker § | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original | Xenografts | Pattern | in CDM | in Agar | DT (h) | CEA ng/mL | CA19‐9 u/mL | TPA u/L | CA125 u/mL | |

| Sui65 | Tub.ad. | Mod.tub.ad. | M | + | + | 48.6 | <0.5 | 69 | 2600 | 32.2 |

| Sui66 | Tub.ad. | Mod./well. | M | + | + | 41.2 | 1.2 | <6 | 1800 | 2.2 |

| Sui67 | Tub.ad. | Poor.tub.ad. | M | + | + | 35.1 | 2.6 | 420 | 1600 | 1.5 |

| Sui68 | Ad. | Poor./mod. | M | + | + | 43.3 | 5.1 | 450 | 980 | 3.2 |

| Sui69 | Tub.ad. | (–) | M | – | – | 55.2 | 0.6 | <6 | 2200 | <1.0 |

| Sui70 | Ad. | Mod.tub.ad. | M | + | + | 20.8 | <0.5 | 290 | 14 000 | 7.5 |

| Sui71 | Ad. | Well.tub.ad. | M | + | + | 24.1 | <0.5 | 170 | 7100 | 9.3 |

| Sui72 | Tub.ad. | Mod.tub.ad. | M | + | + | 27.8 | 31.6 | <6 | 4400 | <1.0 |

| Sarcoma | ||||||||||

| Sui73 | Tub.ad. | Well./mod. | M | + | + | 23.5 | <0.5 | <6 | 2400 | 1.5 |

| Sui74 | Ad. | Mucinos ca. | M | + | + | 47.5 | <0.5 | <6 | 1800 | 13.5 |

The tumorigenicity of the cell lines were tested by s.c. injection of 5 × 105 cultured cells suspended in 0.1 mL RPMI‐1640 medium into mice.

Histological typing of the pancreatic cancer was conducted in accordance with the ‘General Rules for the Study of Pancreatic Cancer (1993)’, as tub (tubular adenocarcinoma), or Muci. ca. (Mucinous carcinoma).

M, monolayer; CDM, composed of Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM)/Ham's F‐12 (1:1) medium supplemented with 0.05% bovine serum albumin (BSA); +, positive; −, negative; DT, doubling time.

The doubling time of each line was determined as described previously.( 20 )

Secretion of CEA, CA19‐9, TPA and CA125 was tested by radioimmunoassay and immunoradioassay at SRL Laboratories (Tokyo, Japan).

Genetic alterations in the established pancreatic cancer cell lines. The results are summarized in Table 3. K‐ras mutations were observed in eight of the 10 cell lines (80%). Activating mutations were detected in the 2nd base of codon 12 of k‐ras in eight cell lines. The mutations were G‐to‐A transitions (GGT to GAT, Gly to Asp) in five cell lines, G‐to‐T transversions (GGT to GTT, Gly to Val) in two cell lines and G‐to‐G transitions (GGT to GGT, Gly to Arg) in the remaining one cell line. Inactivating mutations of p53 were found in eight of the 10 cell lines (80%), and included missense mutations.

Table 3.

Molecular alterations of k‐ras, p53, SMAD4 and P16 genes in newly established human pancreatic cancer cell lines

| Cell line | Gene mutation | Gene expression | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| k‐ras | p53 | SMAD4/DPC4 | p16 | |||

| Sui65 | codon12 | GGT(Gly) → GAT(Asp) | codon248 | CGG(Arg) → CAG(Gln) | – | – |

| Sui66 | codon12 | GGT(Gly) → GAT(Asp) | codon133 | ATG(Met) → AAG(Lys) | + | – |

| Sui67 | codon12 | GGT(Gly) → GAT(Asp) | codon248 | CGG(Arg) → TGG(Trp) | – | + |

| Sui68 | codon12 | GGT(Gly) → GAT(Asp) | codon245 | GGC(Gly) → AGC(Ser) | + | – |

| Sui69 | codon12 | GGT(Gly) → GTT(Val) | codon175 | CGC(Arg) → CAC(His) | – | – |

| Sui70 | codon12 | GGT(Gly) → GTT(Val) | codon175 | CGC(Arg) → CAC(His) | – | – |

| Sui71 | codon12 | GGT(Gly) → GAT(Asp) | codon253 | ACC(Thr) → CCC(Pro) | – | + |

| Sui72 | Wt | codon135 | TGC(Cys) → TAC(Tyr) | + | – | |

| Sui73 | Wt | Wt | + | – | ||

| Sui74 | codon12 | GGT(Gly) → CGT(Arg) | Wt | – | + | |

Next, SMAD4/DPC4 gene expression was checked by Western blot analysis. Marked expression of this gene was observed in Sui66 and Sui73, while the expression was less marked in Sui68 and Sui72; expression was altogether absent in the remaining six cell lines. Expression of the P16 product was noted in Sui67, Sui71 and Sui74, but the levels were quite low or absent in the other cell lines (Table 3).

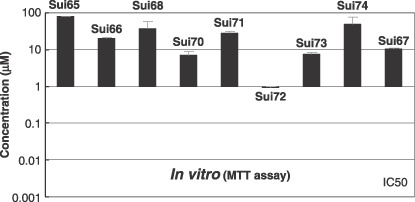

Therapeutic studies with 5‐FU. Using this panel of human pancreatic cancer‐derived cell lines, we evaluated the effect of 5‐FU in suppressing the proliferation of each cell line in vitro. Sui69 was excluded from the analysis, since its proliferation rate was quite slow. The other nine cell lines were subjected to the MTT assay and the results are shown in Fig. 2. Sui72 was about 10‐fold more susceptible to the drug, whereas the other cell lines were resistant to the drug.

Figure 2.

Inhibition of growth of various human pancreatic cancer cell lines by 5‐fluorouracil (5‐FU) in vitro. The cell‐growth inhibitory effects of 5‐FU were assessed by the 3‐(4,5‐dimethylthiazol‐2‐yl)‐2,5‐diphenyltetrazolium bromide) (MTT) assay as described elsewhere.( 21 )

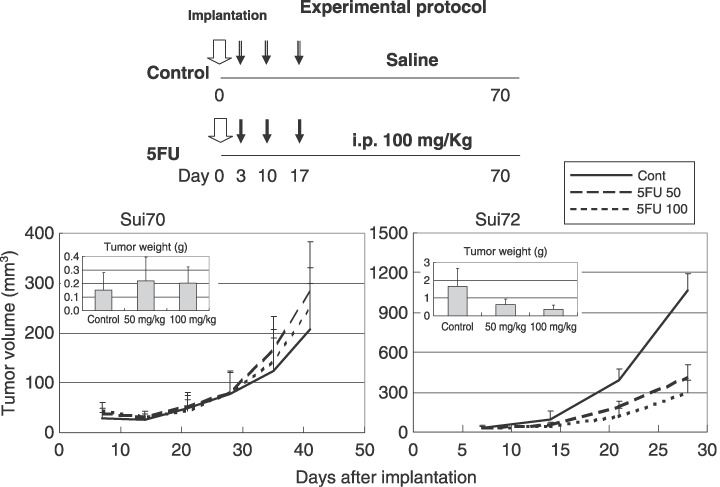

Based on this result, we conducted a study in vivo, in which the highly drug‐susceptible Sui72 and the resistant Sui70 were implanted subcutaneously in SCID mice. The 5‐FU levels tested were 50 and 100 mg/kg/head. As shown in Fig. 3, tumor formation was markedly suppressed in all the mice implanted with Sui72. This suppressive effect was dose dependent, suggesting the effectiveness of 5‐FU against this cell line. On the other hand, 5‐FU did not inhibit the formation of tumor following implantation of Sui70, reflecting the findings in vitro.

Figure 3.

Effect of 5‐fluorouracil (5‐FU) on Sui70 and Sui72 tumor growth in the SCID mouse. Six mice from each group were sacrificed when moribund, or on Day 28 or 40. The tumor mass was measured at predetermined time intervals in two dimensions with calipers, and the tumor volume was calculated according to the equation (l × w2)/2 [l = length, w = width].( 18 ) Pancreatic carcinoma was confirmed by histopathology.

We attempted to identify the cause of the hypersensitivity of Sui72‐5‐FU by RT‐PCR (Table 4). The mRNA expression levels of genes associated with the metabolisms of 5‐FU, i.e. DHFR, EPGS, ECGF (TP), UPP1, PRPS1, TYMS (TS), UMPS (OPRT), TK1, MTHFR, NP (PNP) and UCK2 (UMPK) were analyzed in Sui72 as compared with other cell lines. Remarked decreased expression of DPYD was observed in Sui72 compared with other cell lines (0.6;/–0.5). These results suggest that lower expression of DPYD is the molecular determinant of high sensitivity to 5‐FU in Sui72 cells.

Table 4.

mRNA expression levels of genes related with 5‐FU metabolism in a high sensitive Sui72 cells and in other human pancreatic cancer cell lines

| Genes | Expression † The others ‡ | Expression † Sui72 | Fold |

|---|---|---|---|

| DHFR | 32.7 ± 37.8 | 33.1 | 1.0 |

| FPGS | 10.3 ± 18.3 | n.d. | n.d. |

| TP | 3.1 ± 4.6 | 0.1 | 0.0 |

| UPP1 | 3.8 ± 5.0 | 1.6 | 0.4 |

| PRPS1 | 9.1 ± 5.2 | 3.9 | 0.4 |

| DPYD | 0.6 ± 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| TYMS(TS) | 49.9 ± 33.7 | 35.6 | 0.7 |

| UMPS(OPRT) | 7.2 ± 4.3 | 6.2 | 0.8 |

| TK1 | 46.6 ± 46.3 | 28.4 | 0.6 |

| MTHFR | 4.4 ± 7.8 | 9.6 | 2.2 |

| NP(PNP) | 15.7 ± 8.0 | 23.3 | 1.5 |

| UCK2(UMPK) | 15.8 ± 9.7 | 29.7 | 1.9 |

n.d.: Not detectable by reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction.

Ratio of target gene/GAPD × 10‐3 (fold).

The average ± SD of other cell lines except for Sui72.

Discussion

A number of cultured cell lines have been established from human pancreatic cancers( 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 ) and have contributed greatly to advancing cancer research by allowing biological characterization (analysis of the features of proliferation, progression, etc.) of this cancer and being useful as a preclinical research tool in the evaluation of anticancer agents.( 15 , 16 ) However, after multiple passages, some of these cell lines lose their initial properties (e.g. the histopathological features of the tumors formed following their implantation). There seems to be a universal necessity for enriching the research resources through establishment of new cancer cell lines which would reliably reflect the clinical features of this cancer. Pancreatic cancer is usually characterized by stromal cell infiltration, therefore it is relatively difficult to establish pancreatic cancer cell lines.( 16 ) Bearing this in mind, we first attempted to establish pancreatic cell lines from the tumors formed in SCID mice following implantation of primary or metastatic pancreatic cancer tissue. In this way, we established 10 cell lines of the Sui series. Half of the 10 cell lines were positive for the tumor marker CA19‐9, while all were positive for TPA. The histopathological profile of most of the 10 cell lines resembled that of the original tumor. These findings indicate that the cell lines of this Sui series are pancreatic cancer cell lines reliably reflecting the clinical features of pancreatic cancer. However, one of these cell lines (Sui69) did not form a tumor in the SCID mice, even though it was transplantable. This Sui69 cell line exhibited very slow proliferative activity. We are currently studying this cell line in NOD‐SCID or NOG mice.

Pancreatic cancer cells often exhibit genetic alternations. Point mutation of the oncogene K‐ras, loss of heterozygosity (LOH; 9p, 17p, 18q, 1q, etc.), point mutation of tumor suppresser genes at these chromosomal locations (p16, p53, DPC4/AMAD4, etc.), methylation of the promoter region, etc., have been reported in pancreatic cancer.( 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 ) Of the 10 cell lines established in this study, K‐ras point mutation( 26 , 27 ) and p53 mutation( 28 ) were noted in eight cell lines, and the genetic alterations found resembled those seen in the clinical materials. In Sui73, both K‐ras and p53 were wild type. The SMAD4/DPC4 gene is known to show a high frequency of alterations (50%), including mutation (20%) and deletion (30%).( 29 , 30 ) Marked expression of the SMDA4/DPC4 gene was observed in two cell lines, and less marked expression in two cell lines; expression was altogether absent in the remaining six cell lines. Analysis of expression of the P16/CDKN2A/INK4A product in the 10 established cell lines revealed its expression in three cell lines, but the expression was quite low or altogether absent in remaining seven cell lines. It has been suggested that in pancreatic cancer free of P16 mutations or deletions, expression of this gene is absent because of abnormal methylation of the gene expression–adjusting region and that most pancreatic cancers show malfunctioning of P16.( 30 , 31 ) These changes are seen commonly in many cases of pancreatic cancer and seem to determine the proliferative potential and tumorigenicity of pancreatic cancer cells.

When treating pancreatic cancer, surgical resection, one or a various combination of surgical resection, systemic chemotherapy and radiotherapy is selected depending on the stage of the cancer.( 2 , 25 , 32 ) Conventionally, various regimens of adjuvant chemotherapy, primarily involving 5‐FU, have been attempted,( 3 , 4 , 5 ) but no valid means of treating pancreatic cancer have yet been established. We attempted to evaluate the efficacy of 5‐FU (a drug used as a standard therapy for this cancer in the past) against the cell lines established by us in this study. When tested in vitro, Sui72 was susceptible to the drug, whereas the remaining eight lines (Sui70, etc.) were found to be resistant to the drug. This finding was endorsed by the results of the in vivo study. We then explored the molecular determinant of sensitivity of the Sui72 cell line to 5‐FU. The results of the analysis suggest that the decreased expression of DPYD may be involved in the mechanism of cellular sensitivity to 5‐FU. In addition, decreased expression of TYMS was also observed in Sui72 as compared with other cell lines. This observation might be consistent with high sensitivity to 5‐FU of Sui72 cells.

Throughout this study, it was shown that the new cell lines of the Sui series are useful for research on pancreatic cancer (e.g. evaluation of pancreatic cancer cell proliferation and progression, evaluation of the efficacy of anticancer agents, and so on).

New anticancer agents (e.g. TS‐1, which reinforces the efficacy of 5‐FU),( 33 , 34 , 35 ) and gemcitabine hydrochloride (GEM) have recently become available for clinical use,( 36 , 37 , 38 ) with the expectation of extending the survival period of patients with pancreatic cancer. To date, however, no chemotherapeutic agents more efficacious than GEM for pancreatic cancer have been developed. Clinical studies have therefore been carried out, focusing on developing treatment regimens containing GEM in combination with some other drugs. If GEM were combined with TS‐1 or other molecule‐targeted drugs, further extension of the survival period of pancreatic cancer patients may be expected. In the near future, we propose to carry out preclinical studies to evaluate the efficacy of various anticancer agents in SCID mice implanted with the new cell lines derived from human pancreatic cancer and to identify the genes, etc. which determine the susceptibility of pancreatic cancer cells to anticancer agents. It also seems to be essential to develop a model of orthotopic implantation, with the goal of establishing a drug evaluation system more relevant to the clinical setting.( 23 )

In conclusion, we established 10 cell lines derived from human pancreatic cancers that were found to possess biological characteristics and genetic alterations unique to pancreatic cancer. These new cell lines are expected to be highly useful for analyzing the pattern of pancreatic cancer progression and evaluating the efficacy of anticancer agents.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by a Grant‐in‐Aid for Cancer Research from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan. We are grateful to M. Namae and R. Nakanishi for their excellent technical work.

T. Oda and Y. Aoyagi are currently at HBP Surgery, Tsukuba University, Clinical Medicine, Japan.

References

- 1. Tsukuma H, Ajiki W, Ioka A, Oshima A. Survival of cancer patients diagnosed between 1993 and 1996: a collaborative study of population‐based cancer registries in Japan. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2006; 36: 602–7. Epub 2006 Jul 26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Okusaka T, Matsumura Y, Aoki K. New approaches for pancreatic cancer in Japan. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2004; 54: S78–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ikeda M, Okada S, Ueno H et al . A phase II study of sequential methotrexate and 5‐fluorouracil in metastatic pancreatic cancer. Hepatogastroenterology 2000; 47: 862–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ueno H, Okada S, Okusaka T, Ikeda M, Kuriyama H. Phase II study of uracil‐tegafur in patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer. Oncology 2002; 62: 223–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Okada S. Non surgical treatments of pancreatic cancer. Int J Clin Oncol 1999; 4: 257–66. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bhattacharyya M, Lemoine NR. Gene therapy developments for pancreatic cancer. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2006; 20: 285–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lohr JM. Medical treatment of pancreatic cancer. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther 2007; 7: 533–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kato M, Shimada Y, Tanaka H et al . Characterization of six cell lines established from human pancreatic adenocarcinomas. Cancer 1999; 85: 832–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ku JL, Yoon KA, Kim WH et al . Establishment and characterization of four human pancreatic carcinoma cell lines. Genetic alterations in the TGFBR2 gene but not in the MADH4 gene. Cell Tissue Res 2002; 308: 205–14. Epub 2002 Apr 11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kawano K, Iwamura T, Yamanari H, Seo Y, Suganuma T, Chijiiwa K. Establishment and characterization of a novel human pancreatic cancer cell line (SUIT‐4) metastasizing to lymph nodes and lungs in nude mice. Oncology 2004; 66: 458–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Starr AN, Vexler A, Marmor S et al . Establishment and characterization of a pancreatic carcinoma cell line derived from malignant pleural effusion. Oncology 2005; 69: 239–45. Epub 2005 Sept 2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sato N, Mizumoto K, Beppu K et al . Establishment of a new human pancreatic cancer cell line, NOR‐P1, with high angiogenic activity and metastatic potential. Cancer Lett 2000; 155: 153–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mohammad RM, Li Y, Mohamed AN et al . Clonal preservation of human pancreatic cell line derived from primary pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Pancreas 1999; 19: 353–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kimura Y, Kobari M, Yusa T et al . Establishment of an experimental liver metastasis model by intraportal injection of a newly derived human pancreatic cancer cell line (KLM‐1). Int J Pancreatol 1996; 20: 43–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ulrich AB, Schmied BM, Standop J, Schneider MB, Pour PM. Pancreatic cell lines: a review. Pancreas 2002; 24: 111–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Iwamura T, Hollingsworth MA. Pancreatic tumors. In: Master JRW, Palsson B, eds. Human Cell Culture. Great Britain: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1999; 107–22. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Yanagihara K, Tanaka H, Takigahira M et al . Establishment of two cell lines from human gastric scirrhous carcinoma that possess the potential to metastasize spontaneously in nude mice. Cancer Sci 2004; 95: 575–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yanagihara K, Takigahira M, Tanaka H et al . Development and biological analysis of peritoneal metastasis mouse models for human scirrhous stomach cancer. Cancer Sci 2005; 96: 323–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sun C, Yamato T, Furukawa T, Ohnishi Y, Kijima H, Horii A. Characterization of the mutations of the K‐ras, p53, p16, and SMAD4 genes in 15 human pancreatic cancer cell lines. Oncol Rep 2001; 8: 89–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yanagihara K, Seyama T, Tsumuraya M, Kamada N, Yokoro K. Establishment and characterization of human signet ring cell gastric carcinoma cell lines with amplification of the c‐myc oncogene. Cancer Res 1991; 51: 381–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Arao T, Yanagihara K, Takigahira M et al . ZD6474 inhibits tumor growth and intraperitoneal dissemination in a highly metastatic orthotopic gastric cancer model. Int J Cancer 2006; 118: 483–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rozenblum E, Schutte M, Goggins M et al . Tumor‐suppressive pathways in pancreatic carcinoma. Cancer Res 1997; 57: 1731–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Loukopoulos P, Kanetaka K, Takamura M, Shibata T, Sakamoto M, Hirohashi S. Orthotopic transplantation models of pancreatic adenocarcinoma derived from cell lines and primary tumors and displaying varying metastatic activity. Pancreas 2004; 29: 193–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yatsuoka T, Sunamura M, Furukawa T et al . Association of poor prognosis with loss of 12q, 17p, and 18q, and concordant loss of 6q/17p and 12q/18q in human pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol 2000; 95: 2080–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Giovannetti E, Mey V, Nannizzi S, Pasqualetti G, Del Tacca M, Danesi R. Pharmacogenetics of anticancer drug sensitivity in pancreatic cancer. Mol Cancer Ther 2006; 5: 1387–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Almoguera C, Shibata D, Forrester K, Martin J, Arnheim N, Perucho M. Most human carcinomas of the exocrine pancreas contain mutant c‐K‐ras genes. Cell 1988; 53: 549–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hruban RH, Van Mansfeld AD, Offerhaus GJ et al . K‐ras oncogene activation in adenocarcinoma of the human pancreas. A study of 82 carcinomas using a combination of mutant‐enriched polymerase chain reaction analysis and allele‐specific oligonucleotide hybridization. Am J Pathol 1993; 143: 545–54. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Redston MS, Caldas C, Seymour AB et al . p53 mutations in pancreatic carcinoma and evidence of common involvement of homocopolymer tracts in DNA microdeletions. Cancer Res 1994; 54: 3025–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hahn SA, Schutte M, Hoque AT et al . DPC4, a candidate tumor suppressor gene at human chromosome 18q21.1. Science 1996; 271: 350–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wilentz RE, Su GH, Dai JL et al . Immunohistochemical labeling for dpc4 mirrors genetic status in pancreatic adenocarcinomas: a new marker of DPC4 inactivation. Am J Pathol 2000; 156: 37–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Caldas C, Hahn SA, Da Costa LT et al . Frequent somatic mutations and homozygous deletions of the p16 (MTS1) gene in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Nat Genet 1994; 8: 27–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hochster HS, Haller DG, De Gramont A et al . Consensus report of the international society of gastrointestinal oncology on therapeutic progress in advanced pancreatic cancer. Cancer 2006; 107: 676–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kaneko T, Goto S, Kato A et al . Efficacy of immuno‐cell therapy in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. Anticancer Res 2005; 25: 3709–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zhu AX, Clark JW, Ryan DP et al . Phase I and pharmacokinetic study of S‐1 administered for 14 days in a 21‐day cycle in patients with advanced upper gastrointestinal cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2007; 59: 285–93. Epub 2006 Jun 20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sakata Y, Ohtsu A, Horikoshi N, Sugimachi K, Mitachi Y, Taguchi T. Late phase II study of novel oral fluoropyrimidine anticancer drug S‐1 (1 M tegafur‐0.4 M gimestat‐1 M otastat potassium) in advanced gastric cancer patients. Eur J Cancer 1998; 34: 1715–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rothenberg ML, Moore MJ, Cripps MC et al . A phase II trial of gemcitabine in patients with 5‐FU‐refractory pancreas cancer. Ann Oncol 1996; 7: 347–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Burris HA, 3rd Moore MJ, Andersen J et al . Improvements in survival and clinical benefit with gemcitabine as first‐line therapy for patients with advanced pancreas cancer: a randomized trial. J Clin Oncol 1997; 15: 2403–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Aristu J, Canon R, Pardo F et al . Surgical resection after preoperative chemoradiotherapy benefits selected patients with unresectable pancreatic cancer. Am J Clin Oncol 2003; 26: 30–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]