Abstract

(Cancer Sci 2010; 101: 579–585)

Cholangiocarcinoma is relatively rare, but high incidence rates have been reported in Eastern Asia, especially in Thailand. The etiology of this cancer of the bile ducts appears to be mostly due to specific infectious agents. In 2009, infections with the liver flukes, Clonorchis sinensis or Opistorchis viverrini, were both classified as carcinogenic to humans by the International Agency for Research on Cancer for cholangiocarcinoma. In addition, a possible association between chronic infection with hepatitis B and C viruses and cholangiocarcinoma was also noted. The meta‐analysis of published literature revealed the summary relative risks of infection with liver fluke (both Opistorchis viverrini and Clonorchis sinensis), hepatitis B virus, and hepatitis C virus to be 4.8 (95% confidence interval [95% CI]: 2.8–8.4), 2.6 (95% CI: 1.5–4.6), and 1.8 (95% CI: 1.4–2.4), respectively – liver fluke infection being the strongest risk factor for cholangiocarcinoma. Countries where human liver fluke infection is endemic include China, Korea, Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia. The number of infected persons with Clonorchis sinensis in China has been estimated at 12.5 million with considerable variations among different regions. A significant regional variation in Opistorchis viverrini prevalence was also noted in Thailand (average 9.6% or 6 million people). The implementation of a more intensive preventive and therapeutic program for liver fluke infection may reduce incidence rates of cholangiocarcinoma in endemic areas. Recently, advances have been made in the diagnosis and management of cholangiocarcinoma. Although progress on cholangiocarcinoma prevention and treatment has been steady, more studies related to classification and risk factors will be helpful to develop an advanced strategy to cure and prevent cholangiocarcinoma.

Cholangiocarcinomas (CCAs) – primarily cancers of the epithelial cells (mostly adenocarcinoma) in the bile ducts arising anywhere along the intrahepatic or extrahepatic biliary tree( 1 , 2 )– are relatively rare, but high incidence rates have been reported in Eastern Asia, especially in Thailand.( 3 ) CCAs are highly fatal tumours, as they are clinically silent in the majority of cases.( 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 ) Fortunately, survival of this cancer is improving.( 10 )

CCA occurs with a highly varying frequency in different areas of the world. CCA is second‐most common primary liver cancer and accounted for an estimated 15% of primary liver cancer worldwide;( 3 ) however, it varies widely by region from 5% in Japan( 11 ) and 20% in Pusan (Busan), Korea( 12 ) to 90% in Khon Kaen in Thailand.( 3 )

Recently, a rising tendency of intrahepatic CCA incidence was reported in Western countries.( 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 ) The reasons for this increase are not clear, but some of these increases were attributed to the switch between coding systems going from International Classification of Disease‐Oncology‐2 (ICD‐O‐2) to ICD‐O‐3.

The etiology of CCA in Asian countries appears to be mostly linked to infections, especially infections with the liver flukes Clonorchis sinensis (C. sinensis) and Opisthorchis viverrini (O. viverrini). ( 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 ) These liver flukes, two close members of the family Opistorchiidae,( 21 ) are foodborne trematodes that chronically infect the bile ducts. Liver flukes induce chronic inflammation leading to oxidative DNA‐damage of the infected biliary epithelium and malignant transformation.( 21 ) Chronic infection with either of these two liver flukes is considered to be of major socioeconomic importance to humans and animals in Asian countries such as China, Korea, Vietnam, Laos, and Thailand.( 21 )

In 1994, infection with C. sinensis was classified by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) as ‘probably carcinogenic to humans’ (Group 2A) because there was limited evidence in humans, whereas infection with O. viverrini was already classified as ‘carcinogenic to humans’ (Group 1), based on its involvement in the etiology of CCA.( 22 ) In February 2009, the IARC Monograph Working Group for Volume 100B reassessed the carcinogenicity of infection with liver flukes with a comprehensive review of all of the available published literature.( 23 ) Since the 1994 Monograph, two papers showed that prevalence of infection with liver flukes (C. sinensis and O. viverrini) correlates with incidence of CCA,( 19 , 20 ) and several case–control studies showed a high risk for this cancer.( 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 ) Therefore, infections with C. sinensis or O. viverrini are now both classified in Group 1 by IARC, based on ‘sufficient evidence in humans’ for CCA. In addition, a possible association between chronic infection with hepatitis B and C viruses (HBV and HCV) – known to cause hepatocellular carcinoma – and cholangiocarcinoma was also reported by IARC as there is only limited human evidence.( 23 )

A few review papers on CCA in Asian countries have focused on the relationship of CCA with liver fluke infection,( 28 , 29 ) and on a disclosed role of HCV infection.( 30 , 31 )

In the present paper, the updated CCA epidemiology includes (1) summary risk estimates of the risk factors of CCA (i.e. liver fluke, HBV, and HCV infection) in the form of a meta‐analysis of published literature; and (2) epidemiology of liver fluke infection, focusing on East Asian countries.

Relative Risk Estimation of Risk Factors: Systematic Review and Meta‐Analysis

Methods. Published literature showing association between CCA and infections with liver fluke, HBV, or HCV was retrieved and a full‐text analysis was performed to estimate the summary odds ratio (OR) using a meta‐analysis (Table 1). Pooled ORs with a 95% confidence interval (CI) on the basis of both fixed‐ and random‐effect models were estimated. The pooled ORs were separately estimated for intrahepatic CCA or extrahepatic CCA and then the relative risks were compared separately for sensitivity analysis. The overall summary estimates were the combined effect for both intrahepatic CCA and extrahepatic CCA due to an overlap of confidence intervals of the pooled ORs of each CCA. Heterogeneity analysis was carried out to verify if there was a significant difference by studies. For statistical analysis, Stata version 10.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA) and Comprehensive Meta‐Analysis version 2 (Biostat, Englewood, NJ, USA) were used.

Table 1.

Summary of study characteristics according to liver fluke, HBV, and HCV infection included in meta‐analysis

| Risk factors Study | Study design and place | Cholangiocarcinoma | Control | Comments | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Exposure | n | Exposure | |||

| Clonorchis sinensis | CS+ | CS+ | Eggs in stool | |||

| Gibson( 72 ) | Autopsy series 1964–1966, Hong Kong | 17 | 11 | 1384 | 310 | CCA Crude OR |

| Kim et al. ( 73 ) | Cross‐sectional study Pusan Gospel hospital, Busan and Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul, Korea, 1961–1972 | 54 | 21 | 1348 | 120 | Case: CCA Control: HCC Crude OR |

| Chung & Lee( 74 ) | Cross‐sectional study Busan National University Hospital, Busan, Korea, 1963–74 | 36 | 19 | 559 | 88 | CCA Crude OR |

| Shin et al. ( 24 ) | Hospital‐based case–control study Pusan Paik Hospital, Busan, Korea, 1990–1993 | 36 | 12 | 350 | 44 | CCA Adjusted OR |

| Choi et al. ( 26 ) | Hospital‐based case–control study Samsung Medical Center, Seoul, Korea, 2003–2004 | 122 | 3 | 122 | 5 | Intrahepatic, hilar, extrahepatic CCA Adjusted OR |

| Lee et al. ( 27 ) | Hospital‐based case–control study Asan Medical Center, Seoul, Korea, 2000–2004 | 622 | 26 | 2488 | 9 | Intrahepatic CCA Adjusted OR |

| Opisthorchis viverrini | n | OV+ | n | OV+ | Eggs in stool | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kurathong et al. ( 18 ) | Cross‐sectional study Ramathibodi hospital, Bangkok, Thailand, 1981–1983 | 25 | 19 | 535 | 389 | CCA Crude OR |

| Parkin et al. ( 75 ) | Matched case–control study. Three hospitals, Maharat Nakornratchasima Hospital (Korat) and Sappasithppasong Hospital, Ubonratchathani (Ubon) both in north‐east Thailand, and the National Cancer Institute, Bangkok, Thailand, 1987–1988 | 101 | 43 | 101 | 9 | CCA Adjusted OR |

| Haswell‐Elkins et al. ( 76 ) | Cross‐sectional study Khon Kaen and Mahasarakham province, Thailand, 1990–1991 | 15 | 14 | 1792 | 1383 | CCA Crude OR |

| Honjo et al. ( 25 ) | Population‐based case–control study Nakhon Pahnom provincial hospital, Nakhon Pahnom, Thailand, 1999–2001 | 126 | 65 | 127 | 8 | CCA Adjusted OR |

| HBV or HCV infection | n | HBsAg + Anti‐HCV+ | n | HBsAg + Anti‐HCV+ | Comments | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parkin et al. ( 75 ) | Refer to the above description (liver fluke) | 100 | 8 – | 100 | 8 – | CCA HCV not included |

| Shin et al. ( 24 ) | Refer to the above description (liver fluke) | 40 29 | 5 4 | 406 394 | 14 9 | CCA ICD9 155.1 |

| Donato et al. ( 77 ) | Hospital‐based case–control study Two main hospitals in Brescia, Italy, 1995–2000 | 23 24 | 3 6 | 824 | 45 50 | Intrahepatic |

| Yamamoto et al. ( 78 ) | Hospital‐based matched case–control study Osaka City University Hospital and Osaka City General Hospital, Osaka, Japan, 1991–2002 | 50 | 2 18 | 205 | 5 7 | Intrahepatic HBV: unadjusted OR HCV: adjusted OR |

| Shaib et al. ( 79 ) | Population‐based case–control study Cases (aged 65 + ) from SEER 1993–1999 Controls without cancer from Medicare database case definition is the same as Reference( 80 ) | 625 | Not in the table 5 | 90 834 | Not in the table 161 | Intrahepatic Adjusted OR Available adjusted OR for HBV (Table 3), but no information of prevalence of HBV |

| Choi et al. ( 26 ) | Refer to the above description (liver fluke) | 51 | 4 1 | 51 | 5 1 | Intrahepatic |

| Lee et al. ( 27 ) | Refer to the above description (liver fluke) | 622 | 84 12 | 2488 | 125 47 | Intrahepatic |

| Shaib et al. ( 81 ) | Hospital‐based case–control study M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, TX, USA, 1992–2002 | 75 83 | 1 5 | 236 | 1 2 | Intrahepatic |

| 163 | 4 6 | 236 | 2 | Extrahepatic | ||

| Welzel et al. ( 80 ) | Population based case–control study Cases (aged 65 + ) from SEER 1993–1999 Cancer‐free controls from Medicare database | 535 | – | 102 782 | – | Intrahepatic |

| <5 (HCV) | 142 | Adjusted OR | ||||

| 549 | – | – | Extrahepatic | |||

| <5 (HCV) | 142 | Adjusted OR | ||||

| Zhou et al. ( 83 ) | Hospital‐based case–control study Eastern Hepatobiliary Surgery Hospital, Shanghai, China, 2004–2006 | 312 | 151 9 | 438 | 42 6 | Intrahepatic |

| Hsing et al. ( 82 ) | Population‐based case–control study Shanghai Cancer Institute (SCI) and 42 collaborating hospitals in 10 urban districts of Shanghai, China, 1997–2001 | 134 | 19 2 | 762 | 55 15 | Extrahepatic |

| Lee( 83 ) | Case–control study Chang Gung Memorial Hospital Taipei, Taiwan, 1991–2005 | 160 | 60 21 | 160 | 22 10 | Intrahepatic |

| El‐Serag et al. ( 84 ) | Cohort study for HCV and hepatobiliary cancers among US veterans at VA medical facilities in USA, 1988–2004 | HCV cohort 146 394 | Cases = 14 (4.0/100 000 PY) Cases = 15 (4.3/100 000 PY) | Non‐infected cohort 572 293 | Cases = 23 (1.6/100 000 PY) Cases = 60 (4.2/100 000 PY) | Intrahepatic Extrahepatic |

CCA, cholangiocarcinoma; CS+, Clonorchis Sinensis positive; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HCV, hepatitis C virus; ICD9, ICD9, International Classification of Diseases; OR, odds ratio; OV+, Opistorchis Vivernini positive.

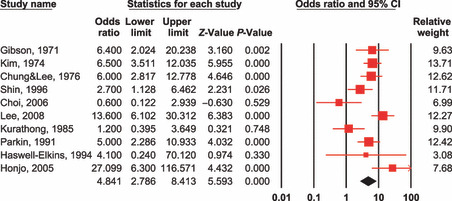

Results. The overall summary relative risks of infection with liver fluke (both C. sinensis and O. viverrini), HBV, and HCV were 4.8 (95% CI: 2.8–8.4), 2.6 (1.5–4.6), and 1.8 (1.4–2.4), respectively (1, 2, 3). Heavy alcohol drinking had a two‐fold increased risk for CCA and was not statistically significant (OR = 2.1, 95% CI: 0.4–10.2) (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Test for heterogeneity: Q = 27.163 on 9 degrees of freedom (P = 0.001). Moment‐based estimate of between‐studies variance = 0.481. 95% CI, 95% confidence interval. Risk estimates for cholangiocarcinoma according to Clonorchis sinensis or Opisthorchis viverrini infection.

Figure 2.

Test for heterogeneity: Q = 40.722 on 9 degrees of freedom (P = 0.000). Moment‐based estimate of between‐studies variance = 0.498. 95% CI, 95% confidence interval. Risk estimates for cholangiocarcinoma according to hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection (overall).

Figure 3.

Test for heterogeneity: Q = 17.296 on 10 degrees of freedom (P = 0.068). Moment‐based estimate of between‐studies variance = 0.188. Risk estimates for cholangiocarcinoma according to hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection (overall).

Issues for discussion. Many studies have investigated the mechanisms of carcinogenesis induced by O. viverrini infection,( 29 ) but there is a paucity of data regarding mechanistic studies for clonorchiasis.

The relative risks of infection with HBV or HCV for the development of intrahepatic CCA and extrahepatic CCA vary widely according to the prevalence of each viral infection and are inconsistent in their significance through different studies. Even though the etiopathogenesis is still inconclusive, the overall risks of HBV‐ or HCV‐associated CCA in meta‐analysis are significant.

The overriding link between most known risk factors and CCA is chronic inflammation and chronic biliary irritation.( 29 , 32 , 33 ) It is still unclear whether biliary neoplasms from different sites share common pathogenic features, even if they are linked anatomically and histopathologically;( 34 ) only a few studies have been carried out to investigate mechanisms of carcinogenesis in CCAs according to anatomical location.( 35 , 36 ) From the epidemiological point of view, the roles of risk factors of intrahepatic CCA and hilar CCA with Klatskin tumor coded as topographically intrahepatic have not yet been clearly elucidated. Further epidemiological research on risk factors according to the anatomical location (intrehepatic vs extrahepatic) and to the macroscopic appearance and/or new histological classification of CCA( 37 ) is needed.

Liver Fluke Infection: Focusing on East Asian Countries

Prevalence, geographic distribution. Countries in which human liver fluke infection is endemic are China, Korea, Thailand, Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia. Persons with C. sinensis infection were infrequently reported from Singapore and Malaysia, and many of them might have been infected in other countries when traveling or through eating imported fish. However, liver fluke infection occurs in all parts of the world where there are Asian immigrants from endemic areas.( 38 )

1. Clonorchis sinensis.

China. In 1994, some archaeologists found a large number of C. sinensis eggs in the content of the bowel from an ancient corpse buried at the middle stage of the Warring States Period (475–221 BC) in Hubei, China,( 39 ) indicating that this disease has been present in this province for more than 2300 years. A comprehensive review paper of clonorchiasis in China shows a very wide range of variations of C. sinensis prevalence from 0.08% to 74.7% during 1960–2003.( 21 ) In a survey over the period 2001–2004 in a Chinese endemic area for liver flukes, a total of 217 829 persons were investigated, and 5230 were found to be infected with C. sinensis, the infection rate being 2.4%. The number of infected persons was estimated to be 12.49 million with the highest prevalence in the provinces of Guangdong (16.4%, 2278/13 876) and Guangxi (9.8%, 1365/13 990) in southern China and Heilongjiang (4.7%, 636/13 458) in Korean (minority) communities in north‐eastern China.( 40 ) In 2001–2004, in a village of Zhaoyuan county, in Heilongjiang province, 87.8% of 1348 residents were found as being positive by stool examination.( 41 )

Since clonorchiasis patients were first diagnosed by Ohi in Taiwan, C. sinensis was one of the most important and most common food‐borne parasites.( 42 ) Infection with C. sinensis is not rare, but is ethnically and geographically associated.( 43 ) The prevalence rates of infection with C. sinensis were 20–50% before 1980 in endemic areas of Miao‐li in northern Taiwan, Sun‐moon lake in the center, and Mei‐nung in the south. In 2000, a prevalence survey in the above endemic areas showed that the C. sinensis infection rate of freshwater snails and fishes which are intermediate hosts was 0.9%, and high infection rate of Haplorchis infections was also observed.( 44 ) From this result, it might be assumed that decrease of C. sinensis prevalence among residents in the endemic area is due to very low infection rate in intermediate hosts. But the reasons are not explained.

Korea. C. sinensis is currently the most prevalent human parasitic helminth detected by fecal examination in Korea. About 1.8 million people were estimated to be infected in 2004.( 45 ) There has not been much decrease in the infection rate of C. sinensis for almost 30 years; the percentage of egg‐positives was 4.6% in 1971, 2.6% (3.8% in males and 1.6% in females) in 1981, 1.4% (1.9% in males and 0.9% in females) in 1997, and 2.9% (3.2% in males and 1.6% in females) in 2004. Egg positivity in males was almost double than that of females.( 45 ) Heavily endemic areas of clonorchiasis in Korea are scattered throughout the country, with the most extensive and intensive endemic regions found mainly along the Nakdong River and the lower reaches of the rivers.( 46 , 47 , 48 )

Vietnam. Due to a lack of available data from national surveys, there is no accurate estimate of the numbers of infected people in Vietnam, however, the World Health Organization estimated in 1995 that approximately 1 million people were infected with C. sinensis or O. viverrini liver flukes.( 38 ) C. sinensis is prevalent in northern Vietnam, while O. viverrini is predominant in central and southern Vietnam.( 49 ) A couple of publications have reported C. sinensis prevalence as low as 5% or less.( 50 , 51 ) A study of 1155 villagers in two communes in northern Vietnam showed that the prevalence of C. sinensis infection was 26% (33.8% in males and 11.0% in females) in 1999–2000.( 52 ) A survey on 771 stool samples showed that the positive rate of C. sinensis was 17.2% by the cellophane thick smear method.( 53 ) There is a generally higher prevalence in males and this is often associated with male‐oriented social gathering during which raw or pickled fish is consumed, and an increasing prevalence with increasing age was also reported.( 51 , 54 ) The increased risks for human infections with fish‐borne liver flukes (C. sinensis) are supposed to be due to the recent rapid development in aquaculture fish production.( 54 )

2. Opisthorchis viverrini.

Thailand. In 1980–1981 the prevalence of O. viverrini in the north, north‐east, central, and south of Thailand was 5.6%, 34.6%, 6.3%, and 0.01% respectively, with an overall prevalence of 14% (or 7 million people infected).( 55 ) Due to the intensive and continuous control activities, the prevalence of infection in north‐east Thailand declined to 15.7% in 2001, and the rates in other areas were 19.3% (north), 3.8% (center), and 0% (south), with an average prevalence of 9.6% (or 6 million people infected).( 56 ) The geographic pattern of O. viverrini infection within the endemic country is not uniform.( 57 )

Laos. It is estimated that over 2 million people are infected with O. viverrini in Laos,( 38 ) mainly in the southern part of the country, in Saravane, Suvannakhet, and Khammuan along the Mekong River, stretching as far as in the lowlands of the country among people with close ethnic ties to the majority of the north‐east Thai population. According to a national survey on primary school children in 17 provinces and the Ventiane Municipality, the rate for O. viverrini was 10.9% (29 846 participants). The regions along the Mekong River such as Khammuane, Saravane, or Savannakhet Province showed a higher prevalence of O. viverrini (32.2%, 21.5%, 25.9%, respectively).( 58 ) More recently, a survey in Saravane district revealed a high prevalence of O. viverrini infection (58.5%) among 814 persons from 13 villages.( 59 )

Cambodia. In Cambodia, there are few official reports or published data on O. viverrini infection. In 2002, a small survey in primary school children from Kampongcham province showed a prevalence of Opisthorchis sp. of 4.0% from 251 fecal specimens.( 60 )

Vietnam. O. viverrini is reported to be endemic in the central and southern parts of the country.( 49 )

Risk factors for liver fluke infection. The main risk factors for liver fluke infection are: (1) consumption of raw or undercooked freshwater fish: many surveys show that people in Thailand,( 28 , 29 ) Vietnam,( 52 ) China,( 21 , 40 ) Laos,( 61 ) and Korea( 20 ) have such habits. (2) Poor sanitation: it is common in some endemic regions in China, particularly in the provinces of Guangdong and Guangxi, that ‘lavatories’ are built adjacent to fish ponds, resulting in human excrement containing C. sinensis eggs ending up in the pond water.( 21 ) It is also reported in Laos that 95.5% of houses in some rural villages in Bolikhamxay Province do not have a latrine. More than half of the people in the village use animal and/or human feces as fertilizer, and two‐thirds of them eat raw fish.( 61 ) (3) Fresh water aquaculture is developing rapidly, but food quality controls are not in place.( 62 ) (4) Accidental ingestion of C. sinensis metacercariae via hands or utensils: contamination occurs as a consequence of not thoroughly washing after catching and handling freshwater fish in endemic areas.( 21 )

Transmission. The definitive host is infected by the liver fluke through ingestion of raw or undercooked (i.e. dried, pickled, or salted) infected fish which contain metacercariae – the infective stage of the liver fluke. In southern China and among the Cantonese populations in Hong Kong, raw fish is traditionally eaten after being dipped in rice porridge. Alternatively, large fish are sliced and eaten with ginger and garlic known as ‘yushen’, and with this route of transmission the infection rate tends to increase with age. Many children in the hilly areas of Guangdong and eastern China such as Jiangsu, Shandong, and Anhui provinces often catch fish during play‐time and roast it incompletely before eating it. With this mode of transmission, the infection rate tends to decline with age.( 40 ) Koreans eat raw fresh fish soaked in vinegar, red‐pepper mash, or hot bean paste with rice wine at social gatherings.( 46 ) The fact that men do so more frequently than women has been given as an explanation for the higher prevalence of the infection among men; however, in heavily endemic areas, no significant differences are observed between genders.( 46 ) When fish is abundant, raw fish is eaten more frequently as opposed to being reserved for special occasions. Vietnamese people also eat raw fish.( 52 ) In Thailand and lowland parts of Laos,( 63 , 64 ) three types of uncooked fish preparations are noted: (1) koi pla, eaten soon after preparation; (2) moderately fermented pla som, stored from a few days to weeks; and (3) pla ra extensively fermented, highly salted fish, stored for at least 2–3 months.( 57 , 65 ) At present, koi pla is probably the most infective dish, followed by fish preserved for <7 days, then pla ra and jaewbhong, in which viable metacercariae are rare.( 57 )

Other Risk Factors of Cholangiocarcinoma

Both intrahepatic CCA and extrahepatic CCA are well‐known complications of primary scleosing cholangitis (PSC) in Western countries.( 66 ) The other known risk factors for CCA include cirrhosis, chronic non‐alcoholic liver disease, obesity, and hepatolithiasis. Other rarer conditions associated with the development of CCA are bile‐duct adenoma, multiple biliary papillomatosis, choledochal cysts, congenital fibropolycystic liver, Caroli’s disease (cystic dilatation of intrahepatic bile ducts), and exposure to the radiopaque medium thorium dioxide (Thorotrast).( 4 , 5 , 6 , 8 , 14 ) Approximately 90% of patients diagnosed with cholangiocarcinoma do not have a recognized risk factor in Western countries.( 67 )

Among these risk factors, hepatolithiasis is a very uncommon disease in the West; in contrast, intra‐ and extrahepatic bile duct stones are much more common in Eastern Asia.( 30 ) Hepatolithiasis is strongly associated with cholangiocarcinoma with proportions varying from 10% in Japan to more than 60% in Taiwan.( 68 , 69 ) Similarly, in the cholangiocarcinogenesis of other risk factors, bacterial infection and bile stasis, which are demonstrable in virtually all patients, underlie cholangiocarcinoma development.( 30 , 70 , 71 ) This carcinogenic process is not limited to the intrahepatic lesions.

Conclusive Remarks

The etiology of CCA in Asian countries appears to be mostly linked to infections, especially infections with liver flukes C. sinensis and O. viverrini which are the strongest risk factor for CCA. In addition, infection with HBV and HCV are significantly associated with the development of CCA.

The mechanisms of adenocarcinoma carcinogenesis in the bile ducts caused by chronic infection with liver flukes include chronic inflammation and resulting oxidative stress. Established mechanistic events for hepatitis B or C viruses in the development of CCAs consist of inflammation, liver cirrhosis, chronic hepatitis, and liver fibrosis.( 23 )

In Asian countries, an improved recognition of etiological factors such as liver flukes, hepatitis B or C viruses, and environmental exposures has heightened awareness of CCA and improved surveillance in patients with these risk factors. Eating habits such as ingestion of raw or undercooked (dried, pickled, or salted) infected fish which contain metacercariae, however, are still prevalent in endemic areas. More attention should to be paid to primary prevention of liver fluke infection through health education and hygiene improvement. In high HBV endemic regions in Asia, universal vaccination in the 1990s showed long‐lasting protection against becoming a carrier, and decreases of chronic liver disease and liver cancer are anticipated. Screening of HCV for blood transfusion has also prevented the transmission of HCV infection since the early 1990s. The burden of CCAs attributed with HBV and HCV are, however, not fully investigated. Recently, advances have been made in the diagnosis and management of CCA. Although progress on CCA prevention caused by liver fluke and treatment has been steady, more studies related to classification and risk factors will be helpful to develop an advanced strategy to control CCA.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Katiuska Veselinovic for her assistance in preparing this review and Laurent Galichet for manuscript editing.

References

- 1. Nakeeb A, Pitt HA, Sohn TA et al. Cholangiocarcinoma. A spectrum of intrahepatic, perihilar, and distal tumors. Ann Surg 1996; 224: 463–73; discussion 73–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Esposito I, Schirmacher P. Pathological aspects of cholangiocarcinoma. HPB (Oxford) 2008; 10: 83–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Parkin DM, Ohshima H, Srivatanakul P, Vatanasapt V. Cholangiocarcinoma: epidemiology, mechanisms of carcinogenesis and prevention. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 1993; 2: 537–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Olnes MJ, Erlich R. A review and update on cholangiocarcinoma. Oncology 2004; 66: 167–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lazaridis KN, Gores GJ. Cholangiocarcinoma. Gastroenterology 2005; 128: 1655–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Blechacz BR, Gores GJ. Cholangiocarcinoma. Clin Liver Dis 2008; 12: 131–50, ix. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Blechacz B, Gores GJ. Cholangiocarcinoma: advances in pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. Hepatology 2008; 48: 308–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Khan SA, Toledano MB, Taylor‐Robinson SD. Epidemiology, risk factors, and pathogenesis of cholangiocarcinoma. HPB (Oxford) 2008; 10: 77–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yachimski P, Pratt DS. Cholangiocarcinoma: natural history, treatment, and strategies for surveillance in high‐risk patients. J Clin Gastroenterol 2008; 42: 178–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. DeOliveira ML, Cunningham SC, Cameron JL et al. Cholangiocarcinoma: thirty‐one‐year experience with 564 patients at a single institution. Ann Surg 2007; 245: 755–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Primary liver cancer in Japan. Clinicopathologic features and results of surgical treatment. Liver Cancer Study Group of Japan. Ann Surg 1990; 211: 277–87. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jung MY, Shin HR, Lee CU, Y SS, Lee SW, Park BC. A study of the ratio of hepatocellular carcinoma over cholangiocarcinoma and their risk factors. J Pusan Med Assoc 1993; 29: 29–37. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Patel T. Increasing incidence and mortality of primary intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in the United States. Hepatology 2001; 33: 1353–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Shaib Y, El‐Serag HB. The epidemiology of cholangiocarcinoma. Semin Liver Dis 2004; 24: 115–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. McGlynn KA, Tarone RE, El‐Serag HB. A comparison of trends in the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2006; 15: 1198–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. West J, Wood H, Logan RF, Quinn M, Aithal GP. Trends in the incidence of primary liver and biliary tract cancers in England and Wales 1971–2001. Br J Cancer 2006; 94: 1751–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kim YI. Liver carcinoma and liver fluke infection. Arzneimittelforschung 1984; 34: 1121–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kurathong S, Lerdverasirikul P, Wongpaitoon V et al. Opisthorchis viverrini infection and cholangiocarcinoma. A prospective, case‐controlled study. Gastroenterology 1985; 89: 151–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sriamporn S, Pisani P, Pipitgool V, Suwanrungruang K, Kamsa‐ard S, Parkin DM. Prevalence of Opisthorchis viverrini infection and incidence of cholangiocarcinoma in Khon Kaen, Northeast Thailand. Trop Med Int Health 2004; 9: 588–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lim MK, Ju YH, Franceschi S et al. Clonorchis sinensis infection and increasing risk of cholangiocarcinoma in the Republic of Korea. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2006; 75: 93–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lun ZR, Gasser RB, Lai DH et al. Clonorchiasis: a key foodborne zoonosis in China. Lancet Infect Dis 2005; 5: 31–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. IARC , ed. Schistosomes, Liver Flukes and Helicobactor pylori. Lyon, France: IARC, 1994. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bouvard V, Baan R, Straif K et al. A review of human carcinogens – Part B: biological agents. Lancet Oncol 2009; 10: 321–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Shin HR, Lee CU, Park HJ et al. Hepatitis B and C virus, Clonorchis sinensis for the risk of liver cancer: a case‐control study in Pusan, Korea. Int J Epidemiol 1996; 25: 933–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Honjo S, Srivatanakul P, Sriplung H et al. Genetic and environmental determinants of risk for cholangiocarcinoma via Opisthorchis viverrini in a densely infested area in Nakhon Phanom, northeast Thailand. Int J Cancer 2005; 117: 854–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Choi D, Lim JH, Lee KT et al. Cholangiocarcinoma and Clonorchis sinensis infection: a case‐control study in Korea. J Hepatol 2006; 44: 1066–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lee TY, Lee SS, Jung SW et al. Hepatitis B virus infection and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in Korea: a case‐control study. Am J Gastroenterol 2008; 103: 1716–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kaewpitoon N, Kaewpitoon SJ, Pengsaa P, Sripa B. Opisthorchis viverrini: the carcinogenic human liver fluke. World J Gastroenterol 2008; 14: 666–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sripa B, Pairojkul C. Cholangiocarcinoma: lessons from Thailand. Curr Opin Gastroenterol 2008; 24: 349–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Okuda K, Nakanuma Y, Miyazaki M. Cholangiocarcinoma: recent progress. Part 1: epidemiology and etiology. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2002; 17: 1049–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Okuda K, Nakanuma Y, Miyazaki M. Cholangiocarcinoma: recent progress. Part 2: molecular pathology and treatment. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2002; 17: 1056–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Gores GJ. Cholangiocarcinoma: current concepts and insights. Hepatology 2003; 37: 961–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Khan SA, Thomas HC, Davidson BR, Taylor‐Robinson SD. Cholan‐giocarcinoma. Lancet 2005; 366: 1303–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rashid A. Cellular and molecular biology of biliary tract cancers. Surg Oncol Clin N Am 2002; 11: 995–1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tsuda H, Satarug S, Bhudhisawasdi V, Kihana T, Sugimura T, Hirohashi S. Cholangiocarcinomas in Japanese and Thai patients: difference in etiology and incidence of point mutation of the c‐Ki‐ras proto‐oncogene. Mol Carcinog 1992; 6: 266–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ohashi K, Tsutsumi M, Nakajima Y et al. High rates of Ki‐ras point mutation in both intra‐ and extra‐hepatic cholangiocarcinomas. Jpn J Clin Oncol 1994; 24: 305–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Konishi M, Ochiai A, Ojima H et al. A new histological classification for intra‐operative histological examination of the ductal resection margin in cholangiocarcinoma. Cancer Sci 2008; 100: 255–260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. WHO . Control of Foodborne Trematode Infections. WHO technical Report Series 849, WHO: Genova, 1995; 1–157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wu Z, Guan Y, Zhou Z. [Study of an ancient corpse of the Warring States period unearthed from Tomb No. 1 at Guo‐Jia Gang in Jingmen City (a comprehensive study)]. J Tongji Med Univ 1996; 16: 1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Fang Y, Cheng Y, Wu J, AZhang Q, Ruan C. Current pevalence of Clonorchis sinensis infection in endemic areas of China. Chin J Parasitol Parasit Dis 2008; 26: 81–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Choi MS, Choi D, Choi MH et al. Correlation between sonographic findings and infection intensity in clonorchiasis. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2005; 73: 1139–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Chen ER. Clonorchiasis in Taiwan. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health 1991; 22 (Suppl): 184–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Yeh TC, Lin PR, Chen ER, Shaio MF. Current status of human parasitic infections in Taiwan. J Microbiol Immunol Infect 2001; 34: 155–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wang JJ, Chung LY, Lee JD et al. Haplorchis infections in intermediate hosts from a clonorchiasis endemic area in Meinung, Taiwan, Republic of China. J Helminthol 2002; 76: 185–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kim TS, Cho SH, Huh S et al. A nationwide survey on the prevalence of intestinal parasitic infections in the Republic of Korea, 2004. Korean J Parasitol 2009; 47: 37–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Choi DW. Clonorchis sinensis: life cycle, intermediate hosts, transmission to man and geographical distribution in Korea. Arzneimittelforschung 1984; 34: 1145–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Rim HJ. Clonorchiasis: an update. J Helminthol 2005; 79: 269–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Cho SH, Lee KY, Lee BC et al. Prevalence of clonorchiasis in southern endemic areas of Korea in 2006. Korean J Parasitol 2008; 46: 133–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. De NV, Murrell KD, Cong LD et al. The foodborne termatode zoonoses of Vietnam. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health 2003; 34 (Suppl 1): 12–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Verle P, Kongs A, Dr NV et al. Prevalence of intestinal parasitic infection in northern Vietnam. Trop Med Int Health 2003; 8: 961–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Trung Dung D, Van De N, Waikagul J et al. Fishborne zoonotic intestinal trematodes, Vietnam. Emerg Infect Dis 2007; 13: 1828–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Dang TC, Yajima A, Nguyen VK, Montresor A. Prevalence, intensity and risk factors for clonorchiasis and possible use of questionnaires to detect individuals at risk in northern Vietnam. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2008; 102: 1263–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Nontasut P, Thong TV, Waikagul J et al. Social and behavioral factors associated with Clonorchis infection in one commune located in the Red River Delta of Vietnam. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health 2003; 34: 269–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Keiser J, Utzinger J. Emerging foodborne trematodiasis. Emerg Infect Dis 2005; 11: 1507–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Harinasuta C, Harinatusa T. Opisthorchis viverrini: life cycle, intermediate hosts, transmission to man and geographical distribution in Thailand. Arzneim-Forsch Drug Res 1984; 34: 1164–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Jongsuksuntigul P, Imsomboon T. Opisthorchiasis control in Thailand. Acta Trop 2003; 88: 229–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Sithithaworn P, Haswell‐Elkins M. Epidemiology of Opisthorchis viverrini. Acta Trop 2003; 88: 187–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Rim HJ, Chai JY, Min DY et al. Prevalence of intestinal parasite infections on a national scale among primary schoolchildren in Laos. Parasitol Res 2003; 91: 267–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Sayasone S, Odermatt P, Phoumindr N et al. Epidemiology of Opisthorchis viverrini in a rural district of southern Lao PDR. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2007; 101: 40–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Lee KJ, Bae YT, Kim DH et al. Status of intestinal parasites infection among primary school children in Kampongcham, Cambodia. Korean J Parasitol 2002; 40: 153–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Hohmann H, Panzer S, Phimpachan C, Southivong C, Schelp FP. Relationship of intestinal parasites to the environment and to behavioral factors in children in the Bolikhamxay Province of Lao PDR. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health 2001; 32: 4–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Fang YY, Wu J, Liu Q et al. Investigaion and analysis on epidemic status clonorchiasis in Guangdong Province, China. J Pathog Biol 2007; 2: 54–6. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Migasena S, Egoramaiphol S, Tungtrongchitr R, Migasena P. Study on serum bile acids in opisthorchiasis in Thailand. J Med Assoc Thai 1983; 66: 464–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Changbumrung S, Ratarasarn S, Hongtong K, Migasena P, Vutikes S, Migasena S. Lipid composition of serum lipoprotein in opisthorchiasis. Ann Trop Med Parasitol 1988; 82: 263–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Sadun EH. Studies on Opisthorchis viverrini in Thailand. Am J Hyg 1955; 62: 81–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. De Groen PC, Gores GJ, LaRusso NF, Gunderson LL, Nagorney DM. Biliary tract cancers. N Engl J Med 1999; 341: 1368–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Ben‐Menachem T. Risk factors for cholangiocarcinoma. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007; 19: 615–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Kubo S, Kinoshita H, Hirohashi K, Hamba H. Hepatolithiasis associated with cholangiocarcinoma. World J Surg 1995; 19: 637–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Chen MF, Jan YY, Jeng LB et al. Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in Taiwan. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 1999; 6: 136–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Su CH, Shyr YM, Lui WY, P’Eng FK. Hepatolithiasis associated with cholangiocarcinoma. Br J Surg 1997; 84: 969–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Chen MF. Peripheral cholangiocarcinoma (cholangiocellular carcinoma): clinical features, diagnosis and treatment. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1999; 14: 1144–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Gibson JB. Parasites, Liver Disease and Liver Cancer. Lyon: IARC, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- 73. Kim YI, Yang DH, Chang KR. Relationship between Clonorchis sinensis infestation and cholangiocarcinoma of the liver in Korea. Seoul J Med 1974; 15: 247–53. (in Korean) [Google Scholar]

- 74. Chung CS, Lee SK. An epidemiological study of primary liver carcinomas in Busan area with special reference to clonorchis. Korean J Pathol 1976; 10: 33–46. (in Korean) [Google Scholar]

- 75. Parkin DM, Srivatanakul P, Khlat M et al. Liver cancer in Thailand. I. A case‐control study of cholangiocarcinoma. Int J Cancer 1991; 48: 323–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Haswell‐Elkins MR, Mairiang E, Mairiang P et al. Cross‐sectional study of Opisthorchis viverrini infection and cholangiocarcinoma in communities within a high‐risk area in northeast Thailand. Int J Cancer 1994; 59: 505–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Donato F, Gelatti U, Tagger A et al. Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma and hepatitis C and B virus infection, alcohol intake, and hepatolithiasis: a case‐control study in Italy. Cancer Causes Control 2001; 12: 959–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Yamamoto S, Kubo S, Hai S et al. Hepatitis C virus infection as a likely etiology of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Cancer Sci 2004; 95: 592–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Shaib YH, El‐Serag HB, Davila JA, Morgan R, McGlynn KA. Risk factors of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in the United States: a case‐control study. Gastroenterology 2005; 128: 620–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Welzel TM, Graubard BI, El‐Serag HB et al. Risk factors for intrahepatic and extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in the United States: a population‐based case‐control study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007; 5: 1221–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Shaib YH, El‐Serag HB, Nooka AK et al. Risk factors for intrahepatic and extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: a hospital‐based case‐control study. Am J Gastroenterol 2007; 102: 1016–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Zhou YM, Yin ZF, Yang JM et al. Risk factors for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: a case‐control study in China. World J Gastroenterol 2008; 14: 632–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Hsing AW, Zhang M, Rashid A et al. Hepatitis B and C virus infection and the risk of biliary tract cancer: a population‐based study in China. International Journal of Cancer 2008; 122: 1845–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Lee CH, Chang CJ, Lin YJ, Yeh CN, Chen MF, Hsieh SY. Viral hepatitis‐associated intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma shares common disease processes with hepatocellular carcinoma. Br J Cancer 2009; 100: 1765–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. El‐Serag HB, Engels EA, Landgren O et al. Risk of hepatobiliary and pancreatic cancers after hepatitis C virus infection: a population‐based study of U.S. veterans. Hepatology 2009; 49: 116–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]