Abstract

Alphastatin, an endogenous angiogenesis inhibitor, has recently been used as an anticancer agent in several tumor models. This study was to investigate whether local sustained long‐term expression of alphastatin could serve to diminish tumor growth of a human xenograft glioma model. We found that the recombinant alphastatin lentiviruses were able to stably infect HUVECs, and infected HUVECs could sustainably secrete alphastatin, which exhibited potent inhibitory effects on HUVECs migration, differentiation but not proliferation induced by vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) or basic fibroblast growth factor(bFGF). And the expression of secreted protein alphastatin markedly decreased tumor vascularization and inhibited tumor growth. Additionally, alphastatin inhibited VEGF‐ or bFGF‐induced initial stage of angiogenesis by reducing JNk and ERK phosphorylation in vitro. Taken together, these data demonstrate that secreted protein alphastatin inhibits VEGF‐ or bFGF‐induced angiogenesis by suppressing JNK and ERK kinases activation pathways in HUVECs, and markedly inhibits tumor angiogenesis in vivo. Consequently lentivirus‐mediated gene transfer might represent an effective strategy for expression of alphastatin to achieve inhibition of human malignant glioma proliferation and tumor progression. (Cancer Sci 2011; 102: 1038–1044)

Malignant gliomas are highly vascularized human tumors.( 1 ) Angiogenesis plays a pivotal role in the development and progression of human malignancies and may contribute to other molecular mechanisms involved in tumor progression,( 2 ) which is supported by the fact that tumor blood vessel density is an independent prognostic indicator for human astroglial tumors.( 3 ) Despite significant improvements in surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy, malignant gliomas continue to have a poor prognosis and a high relapse rate. Anti‐angiogenesis therapy is currently considered to be a promising anticancer treatment.

Endogenous inhibitor alphastatin, a 24‐amino acid peptide derived from the amino terminus of the alpha chain of human fibrinogen, has potent anti‐angiogenic properties, inhibiting both the migration and tubule formation of human endothelial cells responding to vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) or basic fibroblast growth factor(bFGF) but not influencing tumor cells in vitro, and in tumor models, inhibiting tumor growth by suppressing mice endothelial angiogenesis.( 4 , 5 , 6 ) However, long‐term systemic delivery of recombinant molecules will lead to the reduction of active peptide and is time consuming for the patient. In this regard, delivery of these molecules through a gene therapy approach might provide persistent expression and achieve high local levels of the anti‐angiogenic protein within the tumor microenvironment.( 7 , 8 , 9 )

Lentiviruses represent an attractive new vector system that allows permanent integration of the delivered transgene and can be pseudotyped with a variety of envelopes to achieve broad tropism.( 10 , 11 ) However, the anti‐angiogenic and anti‐tumor effects of lentivirus‐mediated gene transfer of alphastatin have not yet been evaluated. Accordingly, we constructed recombinant lentivirus vectors for long‐term expression of alphastatin, and assessed the anti‐angiogenesis efficiency of secreted protein alphastatin in vitro and in vivo. In addition, the role of JNK, ERK and p38 signaling pathways was investigated during anti‐angiogenesis treatment of alphastatin. Our data revealed the anti‐tumor vasculogenesis activities of lentivirus‐mediated gene transfer of alphastatin, a strategy that would be tremendously useful for brain glioma therapy.

Materials and Methods

Reagents and antibodies. Endothelial cell growth supplement and high glucose DMEM were purchased from Gibco (Grand Island, NY, USA). FBS was purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA). Growth factor‐reduced matrigel (GFR Matrigel) was purchased from BD Bioscience (Bedford, MA, USA). Recombinant human VEGF and bFGF were acquired from PeproTech EC (London, UK). Primary antibodies to β‐actin, JNK, p‐JNK, ERK, p‐ERK, p38 and p‐p38 were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Rat anti‐human CD31 was purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA, USA). SP600125 (a JNK inhibitor), PD 98059 (an ERK inhibitor) and SB 203580 (a p38 inhibitor) were purchased from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA, USA). Restriction enzyme MluI and EcoRI were purchased from New England Biolabs (Beverly, MA, USA).

Cells and cell culture. Freshly delivered umbilical cords were obtained from natural births and HUVECs were isolated from human umbilical cord veins via collagenase digestion as previously described.( 12 ) The cells were cultured in EGM‐2 supplemented with 20% FBS at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. Confluent cultures between the third and eighth passages were employed in the functional assays. The SHG44 and U87 cell line (KeyGEN, Nanjing, China) was maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS, 1% penicillin and 1% streptomycin. Cells were grown at 37°C in a humidified incubator with a gas phase of 5% CO2.

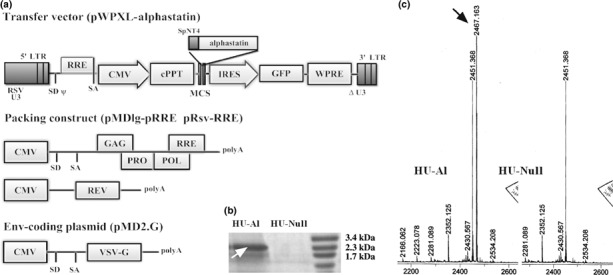

Lentiviral vector production and transduction. The four‐plasmid‐based lentiviral expression system was used in our experiment. Lentiviral shuttle plasmid pWPXL‐MOD was a kind gift from the University of California, San Diego. Plasmid pWPXL‐SpNT4‐Al was constructed as previously described.( 13 , 14 , 15 ) Here, SpNT4 stands for the fusion gene containing human neurotrophin‐4 signal peptide and pro‐region. Briefly, to prepare pseudotyped lentivirus vectors, lent‐SpNT4‐Al, 20 μg pWPXL/SpNT4‐Al, 12 μg pMDLG/pRRE, 10 μg pRSV/REV, and 10 μg pMD2.G were co‐transfected into 293T cells, which were then cultured in 10 cm dishes with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) (Fig. 1a). The lentiviral vector titers were estimated by flow cytometric analyses (FACS) as described previously.( 16 ) HUVECs cells were transduced with Lent‐green fluorescent protein (GFP) and Lent‐SpNT4‐Al at the multiplicity of infection of 40 in the presence of 6 mg/mL polybrene (Sigma‐Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) for 72 h.

Figure 1.

Construction of lentivirus vectors and transfection of HUVECs. (a) Self‐inactivating lentivirus vectors: The human neurotrophin‐4 signal peptide and pro‐region fusion sequences (SpNT4) were cloned into lentiviral transfer vector plasmid pWPXL/GFP, to construct pWPXL‐SpNT4‐Al. Recombinant lentivirus vectors were produced by co‐transfection of the envelope plasmid pMD2.G, packaging plasmid pMDlg‐RRE and pRsv‐RRE, and transfer vector plasmid. (b) After HUVECs were successfully transfected by two kinds of recombined lentivirus at MOI 40, SDS‐PAGE determined only HU‐Al cells express the protein alphastatin, and the production has a higher purity (shown at the white arrow). (c) The difference between two kinds of conditioned medium was that only HU‐Al cell supernatant has secreted protein which molecular weight was 2467.163 kDa (equal to the theoretical value of alphastatin, shown at the black arrow). ΔU3, self‐inactivating deletion in U3 region; ψ, packaging signal; CMV, cytomegalovirus promoter; GFP, green fluorescent protein marker gene; IRES, internal ribosome entry site; LTR, long terminal repeat; MCS, multiple cloning site; poly A, polyadenylation signal; RRE, Rev response element; RSV U3, U3 region from Rous sarcoma virus; SD, splice donor; SA, splice acceptor; VSVG, vesicular stomatitis virus G protein envelope.

Determination of the expression of secreted protein alphastatin. Following gene transfer into HUVECs, the secretion and expression levels of the alphastatin protein were identified by SDS‐PAGE analysis and mass spectrometry analysis. Briefly, HUVEC‐SpNT4‐Al‐GFP or HUVEC‐GFP cells were incubated for 48 h in serum free medium. The conditioned medium was collected and 25 μL of each sample was run on SDS‐PAGE gels, and then gels were stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue. To confirm that alphastatin had been secreted into cell conditioned medium, two kinds of conditioned media were respectively tested with mass spectrometry to identify the target secreted protein molecular weight.

Collection of cell‐conditioned media. Cell conditioned media were collected from HUVEC‐GFP (HU‐Null) cells and HUVEC‐SpNT4‐Al‐GFP (HU‐Al) cells. HU‐Null or HU‐Al cells were cultured until sub‐confluent in DMEM media containing 100 μg/mL endothelial cell growth supplement for 24 h. The medium was then replaced with DMEM containing 1% FCS for a further 24 h. The cell conditioned media were then collected and concentrated 40‐fold by using a Microcon‐10 column (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). Sample collections were stored at −80°C for subsequent function assays.

Proliferation assay. The MTT assay was performed as previously described to measure HUVECs proliferation.( 17 ) Briefly, HUVECs were seeded into 96‐well plates at a density of 3 × 104 cells/mL in the presence of various concentrations of cell conditioned media 0, 2, 12.5 or 25 μL/mL, for 24, 48, or 72 h. A quarter volume of MTT solution (2 mg MTT/ml in PBS) was added to each well, and then the plates were incubated for 4 h at 37°C. The medium was aspirated and the formazan crystals were dissolved in 150 μL of DMSO buffered at pH 10.5. The absorbance was finally read at 590 nm by using a Dynex ELISA plate reader (Ashford, Middlesex, UK).

Migration assay. The cell migration assay was adapted from Malinda et al.,( 18 ) and involved the use of a 24‐well microchemotaxis chamber (AM; Neuro Probe, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) with 8 μm pore size polycarbonate membranes (Neuro Probe), the undersurfaces of which were coated with 10 μL of GFR Matrigel. VEGF or bFGF alone (10 ng/mL) or with various concentrations of the conditioned medium (2, 12.5 or 25 μL/mL) were respectively added to the lower chambers (DMEM containing 1% FCS). HUVEC cells suspension (1 × 105 cells/mL) was then added to the upper chambers and incubated at 37°C for 8 h. Migrated cells adhering to the under surface of the membranes were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and stained with H&E. The migrated cells were then counted using an optical microscope at ×20 magnification.

Tubule formation assay. Twenty‐four‐well plates were coated with GFR Matrigel (300 μL/well). HUVECs were seeded at 2 × 105 cells/mL and incubated for 8 h in 500 μL DMEM + 1% FCS (control), medium + SP600125 (5 μM), medium + PD 98059, medium + SB 203580 or medium + 25 μL/mL conditioned media, either with or without 20 ng/mL bFGF or VEGF. Eight hours later, the endothelial cell‐derived tube‐like structures were visualized using an inverted microscope and photographed at ×20 magnification. The tube‐like structure formation was then quantified by calculating the tube pixel areas.

Western blot analysis. HUVECs were treated as described in the previous section. HUVECs were then washed twice with ice‐cold PBS and lysed in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl [pH 7.9], 5 mM EDTA, 0.1% SDS, 10% glycerol, 0.2% Triton X‐100, 5 μg/mL aprotinin, 1 mM PMSF and one protease inhibitor cocktail tablet). Protein concentrations were determined using a BCA kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA). Each protein lysate (25 μL) was separated on SDS‐PAGE gels and then transferred onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Millipore). The blots were incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies to β‐actin, JNK, p‐JNK, ERK, p‐ERK, p38 and p‐p38 (Santa Cruz), followed by a 1 h incubation with horseradish peroxidase‐conjugated secondary antibodies (Santa Cruz). Proteins were visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescence detection system (Amersham Life Science, Little Chalfont, UK).

Tumor/endothelial cell co‐inoculation assay (in vivo efficacy studies). All mice were handled according to the guidelines for the care and use of Laboratory Animals. This study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Xi’an Jiaotong University. All experiments were performed on 6‐week‐old Balb/c mice weighing 20 g (n = 13) purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). Animals were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of 10% chloral hydrate before experiments. Then 2 × 106 cell/mL (in 100 μL medium) viable SHG44 or U87 (glioma cell lines) cells were respectively implanted subcutaneously, either alone, or co‐implanted with parental HUVEC, HU‐Al or HU‐Null cells at a ratio 10:1 between a tumor cell and endothelial cell. Tumor volumes were measured daily using calipers,( 19 ) along with bodyweight and well‐being.

Immunohistochemical analysis. Mice were sacrificed after 12 days. The tumor tissues were excised, divided in half and fixed overnight in either 10% neutral buffered formalin or a zinc‐based fixative,( 20 ) before being embedded in paraffin wax and sectioned. Formalin‐fixed tissue sections were subsequently stained with anti‐CD31, periodic acid‐Schiff (PAS) and hematoxylin to assess microvessel density (MVD).

Statistical analysis. The data were expressed as the mean ± SEM and representative data from one of the three replicate experiments are shown. The differences between the groups were determined using one‐way anova followed by the Student’s t‐test. A P‐value of <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Construction of lentivirus and expression of secreted alpha‐statin. The lentivirus expression plasmid we constructed contains the elements required for virion packaging, such as 5′ and 3′ long terminal repeats and ψ packaging signal. The packaging system of Lent‐SpNT4‐Al‐GFP is shown in Figure 1a. HUVECs infected by Lent‐SpNT4‐Al‐GFP showed both nuclear and cytoplasmic expression of GFP, typically at a multiplicity of infection of 40, >98% of transduced cells were found to be GFP positive by fluorescence activated cell sorting analysis (data not shown). Secreted protein alphastatin was identified by both SDS‐PAGE and Mass spectrometry analysis, and both results showed that only HU‐Al cells secreted alphastatin. SDS‐PAGE analysis proved that the relative molecular weight of the expressed product was about 2.3–2.5 kDa, which was consistent with the expectation and had higher purity (Fig. 1b). Mass spectrometry analysis showed that the experimental protein molecular weight was about 2467.163 kDa, similar with the theoretic value (Fig. 1c). In our experiment, flow cytometry analysis showed that the virus titer was 3.4 × 108 TU/mL (transducing units/mL media). In conclusion, we believed that lentivirus vector could efficiently transduce fusion gene into HUVEC cells and protein alphastatin could be successfully secreted and expressed in lentinvirus mediated gene delivery system.

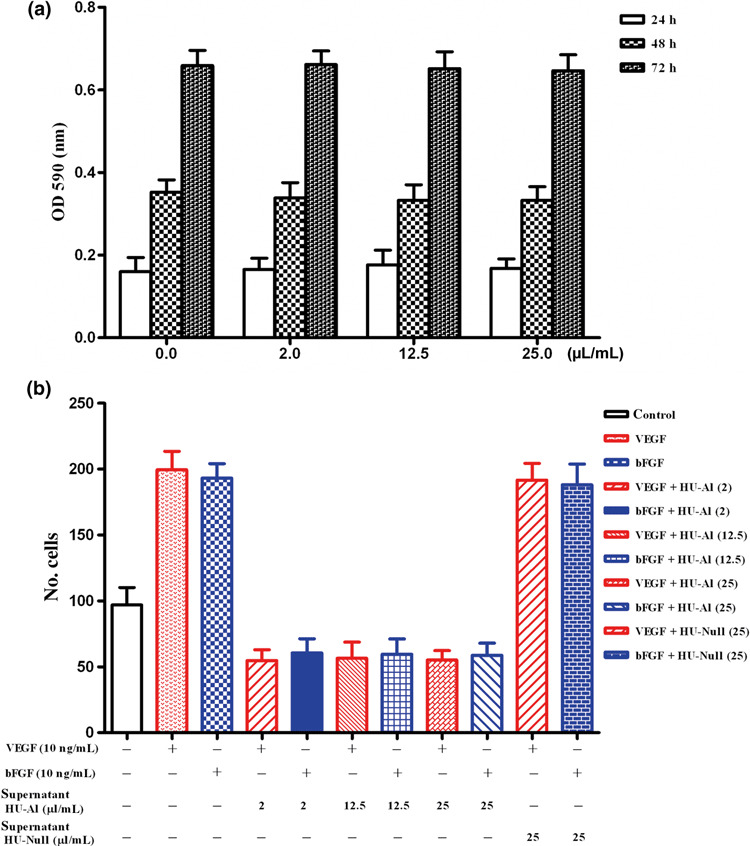

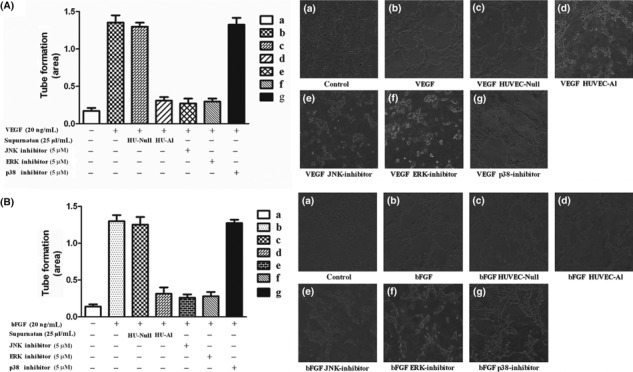

Effects of alphastatin on HUVECs in vitro. Initial experiments were performed to determine whether and how alphastatin affected the three main initial stages of the angiogenesis endothelial proliferation, migration, and tubule formation in vitro.( 21 , 22 , 23 ) We also investigated the effects of JNK, ERK and p38 inhibitors on HUVECs tube formation induced by VEGF or bFGF and found that exposure to alphastatin‐containing conditioned medium at doses of 2, 12.5 and 25 μL/mL for up to 72 h had no significant effect on HUVEC proliferation (Fig. 2a). However, exposure to alphastatin‐containing conditioned media (2, 12.5 and 25 μL/mL) significantly inhibited VEGF‐ or bFGF‐induced migration in the Boyden chamber assay (P < 0.001; Fig. 2b). Besides, we also found that there was no significant difference among groups of conditioned media 2, 12.5 and 25 μL/mL (Fig. 2b) and tubule formation by HUVECs was significantly inhibited by alphastatin‐containing conditioned medium (25 μL/mL), SP600125 (5 μM), PD 98059 (5 μM), and SB 203580 (5 μM) in presence of 20 μg/mL bFGF or VEGF (Fig. 3). The above results showed that alphastatin markedly inhibited HUVECs migration, differentiation but not proliferation induced by VEGF or bFGF, moreover, our related studies showed that recombinant alphastatin peptide significantly inhibited HUVECs migration, differentiation but not proliferation induced by VEGF or bFGF but not influenced human glioma cell (data not shown). And the JNK, ERK inhibitors showed marked efficacy of their abilities in inhibiting HUVECs tube formation induced by VEGF or bFGF.

Figure 2.

Effects of alphastatin on cell migration and cell proliferation in vitro. (a) HUVECs proliferation over a 72‐h period. Exposure to HU‐Al supernatant at dose between 0, 2, 12.5 and 25 μL/mL for up to 72 h had no significant effect on HUVECs proliferation. (b) HUVECs migration across a collagen‐coated filter in response to medium alone (control) or conditioned media (0, 2, 12.5 and 25 μL/mL) containing 10 ng/mL VEGF or bFGF. Alphastatin significantly inhibits VEGF‐ or bFGF‐induced HUVECs migration, and the concentration of conditioned medium 2 μL/m has already reached a saturated inhibition efficacy. Results are expressed as the mean ± SEM. P < 0.001 for VEGF + HU‐Al vs VEGF or bFGF; and P < 0.001 for bFGF + HU‐Al vs VEGF or bFGF.

Figure 3.

Effects of alphastatin on tube formation induced by VEGF or bFGF in vitro. (A) Tube formation by HUVECs exposed to conditioned medium from HU‐Al, HU‐Null cells or containing a JNK, ERK and p‐38 inhibitor in the presence or absence of VEGF (20 ng/mL). The HU‐Al conditioned medium and the JNK, ERK inhibitor significantly inhibited HUVECs tube formation induced by VEGF. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. P < 0.004, (d) vs (b); and P < 0.001, (e) vs (b); and P < 0.001, (f) vs (b). (B) Tube formation by HUVECs exposed to HU‐Al, HU‐Null conditioned medium or JNK, ERK and p‐38 inhibitor in the presence or absence of bFGF (20 ng/mL). HU‐Al supernatant and JNK, ERK inhibitor significant inhibited HUVECs tube formation induced by bFGF. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. P < 0.005, (d) vs (b); and P < 0.004, (e) vs (b); and P < 0.004, (f) vs (b).

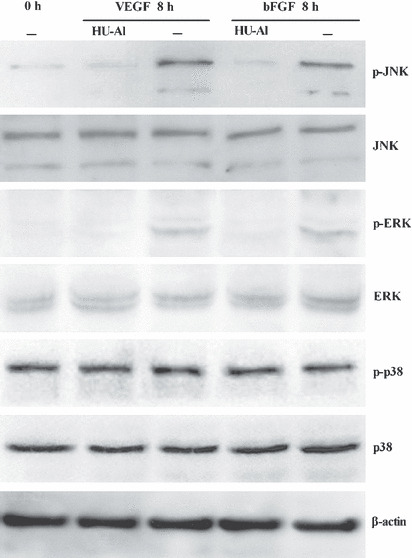

Alphastatin downregulates p‐JNK and p‐ERK expression. We attempted to determine how the anti‐angiogenic activity of alphastatin is mediated through the modulation of JNK, ERK and p38 signal pathway during HUVECs tube formation induced by VEGF or bFGF. Western blot analysis showed that the expression of JNK, ERK and p38 had no significant difference under different conditioned media. However, total p‐JNK and p‐ERK but not p‐p38 were reduced after the treatment with HUVEC‐Al conditioned medium in the presence of VEGF or bFGF (Fig. 4). Taken together, these results suggest that VEGF or bFGF activated JNK and ERK phosphorylation, and alphastatin markedly inhibited angiogenesis by suppressing JNK and ERK phosphorylation pathway.

Figure 4.

Secreted protein alphastatin inhibited VEGF‐ or bFGF‐induced JNK and ERK phosphorylation in HUVECs. HUVECs were cultured in the presence of HU‐Al or HUVECs conditioned media and induced by VEGF or bFGF (20 ng/mL). After 8 h, cells were harvested for protein extraction and western blot analysis. The results show that only the HU‐Al conditioned medium significantly inhibited JNK, ERK but not p‐38 phosphorylation induced by VEGF or bFGF.

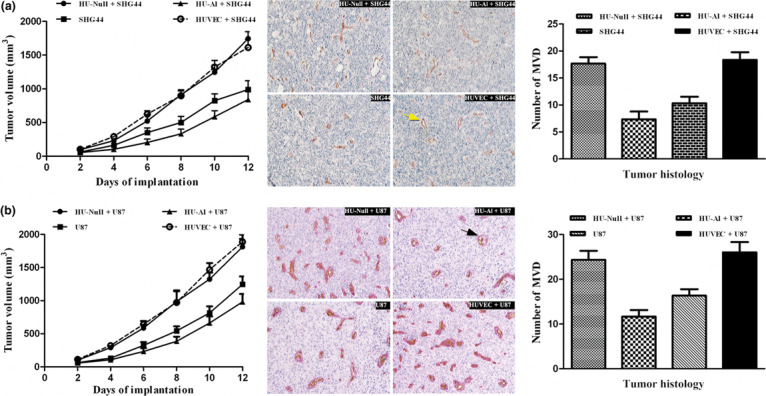

Effects of alphastatin on tumor growth. SHG44 or U87 (glioma cell lines) cells were subcutaneously implanted alone, or co‐implanted with HU‐Null cells, HU‐Al cells or HUVECs. In all SHG44‐type tumors (SHG44, SHG44 + HUVEC, SHG44 + HU‐Null, SHG44 + HU‐Al), tumors grew to a volume between 56 mm3 and 1744 mm3 after 12 days of implantation. SHG44 cells co‐implanted with HUVECs or HU‐Null cells grew steadily, reaching final tumor volumes of 1612 ± 120 and 1744 ± 102 mm3, respectively. However, tumors co‐implanted with SHG44 cells and HU‐Al cells showed a significantly reduced growth rate, reaching a final tumor volume of only 841 ± 124 mm3 after 12 days (P < 0.012; Fig. 5a). Also, tumors co‐implanted with U87 cells and HU‐Al cells showed a significantly reduced growth rate, reaching a final tumor volume of only 981 ± 119 mm3 after 12 days (P < 0.014; Fig. 5b). Similar results were obtained in two repeat experiments. It has been manifested that alphastatin was well tolerated by the animals, and had no significant effect on bodyweight or general well‐being (animals were not lethargic, and intermittent hunching, tremors, or disturbed breathing patterns were not observed). Furthermore, alphastatin could effectively suppress the growth of established tumor model, which was related to the anti‐angiogenesis effects (data not shown). Data showed that secreted protein alphastatin significantly inhibited tumor growth in vivo.

Figure 5.

Effects of alphastatin on tumor growth and tumor histology. (a) The graph shows the changes in SHG44 tumor volume over 12 days. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. P < 0.012, HU‐Al + SHG44 vs SHG44; P < 0.023, HU‐Al + SHG44 vs HU‐Null + SHG44; and P < 0.012, HU‐Al + SHG44 vs HUVEC + SHG44. The average vessel count within three fields was regarded as the microvessel density (MVD), and the four groups were counted respectively. New blood vessels were visible after CD31/PAS double staining (indicated by the yellow arrow); original magnification ×20. The MVD values are expressed as mean ± SEM. P < 0.035, HU‐Al + SHG44 vs SHG44; P < 0.007, HU‐Al + SHG44 vs HU‐Null + SHG44; and P < 0.010, HU‐Al + SHG44 vs HU‐HUVEC + SHG44. (b) The graph shows the changes in U87 tumor volume over 12 days. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. P < 0.012, HU‐Al + U87 vs U87; P < 0.015, HU‐Al + U87 vs HU‐Null + U87; and P < 0.014, HU‐Al + U87 vs HUVEC + U87. The average vessel count within three fields was regarded as the MVD, and the four groups were counted respectively. New blood vessels were visible after CD31/PAS double staining (indicated by the black arrow); original magnification × 20. The MVD values are expressed as mean ± SEM. P < 0.005, HU‐Al + U87 vs U87; P < 0.003, HU‐Al + SHG44 vs HU‐Null + U87; and P < 0.004, HU‐Al + U87 vs HU‐HUVEC + U87.

Effects of alphastatin on tumor histology. Histologic analysis revealed the difference of MVD between different co‐implanted tumor groups. MVD was determined by the examination of CD31‐stained sections at those sites with the greatest number of capillaries and small venules. The positive expression of CD31 was visualized as brown‐yellow or brown granules in the cytoplasm of the vascular endothelial cells. Areas showing increased levels of neovascularization were identified by scanning tumor sections at low power (×10). The average vessel count within three selected fields was then scanned at increased magnification (×20), which was taken as the MVD. In SHG44 group, the MVD was significantly reduced (HU‐Al + SHG44 vs HUVEC + SHG44, 7.333 ± 1.413 vs 18.33 ± 1.432; P < 0.010) in the tumors derived from SHG44 co‐implanted subcutaneously with HU‐Al cells (Fig. 5a). And in U87 group, the MVD was significantly reduced (HU‐Al + U87 vs HUVEC + U87, 11.67 ± 1.453 vs. 26.00 ± 2.309; P < 0.004) in the tumors derived from U87 co‐implanted subcutaneously with HU‐Al cells (Fig. 5b). The results suggested that alphastatin could significantly inhibit tumor angiogenesis.

Discussion

In this study, we showed that recombinant lentivirus vectors can be used for the stable transduction of endothelial cells to achieve persistent secretion of alphastatin, which have been proved to inhibit HUVECs migration, differentiation in vitro and suppress glioma growth in vivo. Our data also indicated that alphastatin inhibited the initial stage of angiogenesis by blocking JNK and ERK phosphorylation pathway. This is the first report to describe the therapeutic effects of lentivirus‐based vectors expressing alphastatin on the growth of glioma.

Lentiviral vectors can integrate their cDNA into both dividing and non‐dividing cells.( 24 ) A third‐generation self‐inactivating (SIN) lentivirus vector, in which the U3 region of the 3′ long terminal repeat (including the TATA box) was deleted, abolishing any long terminal repeat promoter activity,( 25 ) enhanced the security level of transgene expression. In addition, VSV‐G pseudotyped lentivirus vectors, which can bind to cell surface phospholipids,( 26 ) have a potential advantage in achieving efficient gene delivery to endothelial cells. However, the alphastatin sequence alone is not sufficient for efficient translation and secretion in mammalian cells.( 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 ) Therefore, the human neurotrophin‐4 signal peptide and pro‐region sequence were fused in‐frame to ensure exogenous protein expressing in a secretory manner,( 31 ) and a stop codon was appended to the end of the alphastatin coding sequence.

Several endogenous inhibitors of angiogenesis have been well‐characterized, such as interferons, IL‐4, tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinase’s, platelet factor‐4 and the proteolytic fragments angiostatin and endostatin.( 32 ) These inhibitors block the multistep angiogenic process in vascular endothelial cells induced by pro‐angiogenic proteins including VEGF, basic fibroblast growth factor, interleukin‐8, and platelet‐derived growth factor. Here we determined that alphastatin could inhibit HUVECs migration and tube formation induced by VEGF or bFGF. More importantly, alphastatin significantly inhibited glioma growth and decreased the tumor MVD which was essential for the growth of solid tumors and a reliable index of tumor angiogenesis.( 33 ) The results indicated that alphastatin can markedly suppress the initial stages of angiogenesis induced by VEGF or bFGF, tumor angiogenesis and tumor growth.

It has been reported that MAPK signals promote endothelial cell proliferation, cytoskeletal reorganization, migration and, finally, differentiation and formation of a new vascular lumen. ERK–MAPK activation is able to increase proliferation of endothelial cells;( 34 , 37 ) p38‐MAPK activation triggers actin‐based cell motility;( 34 , 35 , 36 ) and JNK–MAPK performs a significant role in both the proliferation and migration properties.( 37 ) We confirmed in our experiment that both VEGF‐ or bFGF‐stimulated HUVECs tube formations were blocked by alphastatin, the JNK inhibitor and ERK inhibitor, and that alphastatin attenuated the VEGF‐ or bFGF‐induced JNK and ERK phosphorylation. Our data support, at least partially, the fact that alphastatin inhibited the VEGF‐ or bFGF‐induced angiogenesis via a reduction in JNK and ERK activation. Finally, we determined that alphastatin inhibited VEGF‐ or bFGF‐induced tube formation by blocking JNK and ERK phosphorylation pathway. Nevertheless, the mechanism of JNK and ERK pathway differed from each other in some aspects during anti‐angiogenesis, which was that the inhibition of ERK blocked cell proliferation, but only partially attenuated migration. However, JNK played a significant role in both proliferation and migration responses.( 37 )

We chose endothelial cells as target cells of transfection in our study for the following reasons. Firstly, in co‐implanting tumor models, sustained secretion protein alphastatin from HUVECs simulated intravenous route of administration to avoid repeated administration directly with expensive recombinant lentivirus. Furthermore, tumor growth is highly dependent on angiogenesis, particularly in brain malignant gliomas.( 38 , 39 ) Finally, in intravenous administration, viral vectors directly access endothelial cells without crossing through the vessel wall to reach the targets and the introduction of a vector into endothelial cells is by contrast exponential or geometric.( 40 ) Thus, introducing HUVECs as target transduction cells represented practically a systematic anti‐angiogenesis therapeutic strategy. Of course, the effect of endothelial cells promoting tumor growth should be considered in co‐implanted tumor models.( 41 )

In conclusion, we constructed recombinant lentivirus‐mediated gene delivery system of alphastatin, which significantly suppressed tumor growth and tumor angiogenesis by blocking JNK phosphorylation pathway.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Quan‐Ying Wang, Guang‐Xiao Yang (Xi’an Huaguang Bioengineering Co.) for expert technical assistance in constructing the recombined plasmid. We are also grateful to Dr. Yong Song for the professional help during our experiments. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 30672162).

References

- 1. Brem S, Tsanaclis AM, Gately S et al. Immunolocalization of basic fibroblast growth factor to the microvasculature of human brain tumors. Cancer 1992; 70: 2673–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Plate KH, Risau W. Angiogenesis in malignant gliomas. Glia 1995; 15: 339–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Leon SP, Folkerth RD, Black PM. Microvessel density is a prognostic indicator for patients with astroglial brain tumors. Cancer 1996; 77: 362–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Staton CA, Brown NJ, Rodgers GR et al. Alphastatin, a 24‐amino acid fragment of human fibrinogen, is a potent new inhibitor of activated endothelial cells in vitro and in vivo . Blood 2004; 103: 601–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chen L, Li T, Li R et al. Alphastatin downregulates vascular endothelial cells sphingosine kinase activity and suppresses tumor growth in nude mice bearing human gastric cancer xenografts. World J Gastroenterol 2006; 12: 4130–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Staton CA, Stribbling SM, Garcia‐Echeverria C et al. Identification of key residues involved in mediating the in vivo anti‐tumor/anti‐endothelial activity of Alphastatin. J Thromb Haemost 2007; 5: 846–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Shichinohe T, Bochner BH, Mizutani K et al. Development of lentiviral vectors for antiangiogenic gene delivery. Cancer Gene Ther 2001; 8: 879–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Folkman J. Antiangiogenic gene therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1998; 95: 9064–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kong HL, Crystal RG. Gene therapy strategies for tumor antiangiogenesis. J Natl Cancer Inst 1998; 90: 273–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Naldini L, Blomer U, Gage FH et al. Efficient transfer, integration, and sustained long‐term expression of the transgene in adult rat brains injected with a lentiviral vector. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1996; 93: 11382–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zufferey R, Nagy D, Mandel RJ et al. Multiply attenuated lentiviral vector achieves efficient gene delivery in vivo . Nat Biotechnol 1997; 15: 871–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jaffe EA, Nachman RL, Becker CG et al. Culture of human endothelial cells derived from umbilical veins. Identification by morphologic and immunologic criteria. J Clin Invest 1973; 52: 2745–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Song LP, Li YP, Wang N et al. NT4(Si)‐p53(N15)‐antennapedia induces cell death in a human hepatocellular carcinoma cell line. World J Gastroenterol 2009; 15: 5813–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Xiaojiang T, Jinsong Z, Jiansheng W et al. Adeno‐associated virus harboring fusion gene NT4‐ant‐shepherdin induce cell death in human lung cancer cells. Cancer Invest 2010; 28: 465–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Li Y, Qiu S, Song L et al. Secretory expression of p53(N15)‐Ant following lentivirus‐mediated gene transfer induces cell death in human cancer cells. Cancer Invest 2008; 26: 28–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Marr RA, Rockenstein E, Mukherjee A et al. Neprilysin gene transfer reduces human amyloid pathology in transgenic mice. J Neurosci 2003; 23: 1992–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Liu J, Kolath J, Anderson J et al. Positive interaction between 5‐FU and FdUMP[10] in the inhibition of human colorectal tumor cell proliferation. Antisense Nucleic Acid Drug Dev 1999; 9: 481–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Malinda KM, Ponce L, Kleinman HK et al. Gp38k, a protein synthesized by vascular smooth muscle cells, stimulates directional migration of human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Exp Cell Res 1999; 250: 168–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Grosios K, Holwell SE, McGown AT et al. In vivo and in vitro evaluation of combretastatin A‐4 and its sodium phosphate prodrug. Br J Cancer 1999; 81: 1318–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Beckstead JH. A simple technique for preservation of fixation‐sensitive antigens in paraffin‐embedded tissues. J Histochem Cytochem 1994; 42: 1127–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ferrara N. Vascular endothelial growth factor: basic science and clinical progress. Endocr Rev 2004; 25: 581–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hanahan D, Folkman J. Patterns and emerging mechanisms of the angiogenic switch during tumorigenesis. Cell 1996; 86: 353–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Conway EM, Collen D, Carmeliet P. Molecular mechanisms of blood vessel growth. Cardiovasc Res 2001; 49: 507–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Naldini L, Blomer U, Gallay P et al. In vivo gene delivery and stable transduction of non‐dividing cells by a lentiviral vector. Science 1996; 272: 263–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zufferey R, Dull T, Mandel RJ et al. Self‐inactivating lentivirus vector for safe and efficient in vivo gene delivery. J Virol 1998; 72: 9873–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Schlegel R, Tralka TS, Willingham MC et al. Inhibition of VSV binding and infectivity by phosphatidylserine: is phosphatidylserine a VSV‐binding site? Cell 1983; 32: 639–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Nagai K, Oubridge C, Kuglstatter A et al. Structure, function and evolution of the signal recognition particle. EMBO J 2003; 22: 3479–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Muller JP, Bron S, Venema G et al. Chaperone‐like activities of the CsaA protein of bacillus subtilis. Microbiology 2000; 146: 77–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tjalsma H, Antelmann H, Jongbloed JD et al. Proteomics of protein secretion by bacillus subtilis: separating the “secrets” of the secretome. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 2004; 68: 207–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zanen G, Antelmann H, Meima R et al. Proteomic dissection of potential signal recognition particle dependence in protein secretion by bacillus subtilis. Proteomics 2006; 6: 3636–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Fan G, Egles C, Sun Y et al. Knocking the NT4 gene into the BDNF locus rescues BDNF deficient mice and reveals distinct NT4 and BDNF activities. Nat Neurosci 2000; 3: 350–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sim BK, MacDonald NJ, Gubish ER. Angiostatin and endostatin: endogenous inhibitors of tumor growth. Cancer Metastasis Rev 2000; 19: 181–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bouck N. Tumor angiogenesis: the role of oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes. Cancer Cells 1990; 2: 179–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kanno S, Oda N, Abe M et al. Roles of two VEGF receptors, Flt‐1 and KDR, in the signal transduction of VEGF effects in human vascular endothelial cells. Oncogene 2000; 19: 2138–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rousseau S, Houle F, Kotanides H et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)‐driven actin‐based motility is mediated by VEGFR2 and requires concerted activation of stress‐activated protein kinase 2 (SAPK2/p38) and geldanamycin‐sensitive phosphorylation of focal adhesion kinase. J Biol Chem 2000; 275: 10661–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lamalice L, Houle F, Jourdan G et al. Phosphorylation of tyrosine 1214 on VEGFR2 is required for VEGF‐induced activation of Cdc42 upstream of SAPK2/p38. Oncogene 2004; 23: 434–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Meadows KN, Bryant P, Vincent PA et al. Activated Ras induces a proangiogenic phenotype in primary endothelial cells. Oncogene 2004; 23: 192–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Louis DN, Pomeroy SL, Cairncross JG. Focus on central nervous system neoplasia. Cancer Cell 2002; 1: 125–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Papale A, Cerovic M, Brambilla R. Viral vector approaches to modify gene expression in the brain. J Neurosci Methods 2009; 185: 1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Liu Y, Deisseroth A. Tumor vascular targeting therapy with viral vectors. Blood 2006; 107: 3027–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Calabrese C, Poppleton H, Kocak M et al. A perivascular niche for brain tumor stem cells. Cancer Cell 2007; 11: 69–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]