Abstract

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is one of the most prevalent cancers worldwide. However, effective chemopreventive and chemotherapeutic agents for this cancer have not yet been developed. In clinical trials acyclic retinoid (ACR) and vitamin K2 (VK2) decreased the recurrence rate of HCC. In the present study we examined the possible combined effects of ACR or another retinoid 9‐cis retinoic acid (9cRA) plus VK2 in the HuH7 human HCC cell line. We found that the combination of 1.0 µM ACR or 1.0 µM 9cRA plus 10 µM VK2 synergistically inhibited the growth of HuH7 cells without affecting the growth of Hc normal human hepatocytes. The combined treatment with ACR plus VK2 also acted synergistically to induce apoptosis in HuH7 cells. Treatment with VK2 alone inhibited phosphorylation of the retinoid X receptor (RXR)α protein, which is regarded as a critical factor for liver carcinogenesis, through inhibition of Ras activation and extracellular signal‐regulated kinase phosphorylation. Moreover, the inhibition of RXRα phosphorylation by VK2 was enhanced when the cells were cotreated with ACR. The combination of retinoids plus VK2 markedly increased both the retinoic acid receptor responsive element and retinoid X receptor responsive element promoter activities in HuH7 cells. Our results suggest that retinoids (especially ACR) and VK2 cooperatively inhibit activation of the Ras/MAPK signaling pathway, subsequently inhibiting the phosphorylation of RXRα and the growth of HCC cells. This combination might therefore be effective for the chemoprevention and chemotherapy of HCC. (Cancer Sci 2007; 98: 431–437)

Abbreviations

- 9cRA

9‐cis‐retinoic acid

- ACR

acyclic retinoid

- ERK

extracellular signal‐regulated kinase

- FCS

fetal calf serum

- GAPDH

glyceraldehyde‐3‐phosphate dehydrogenase

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- MAPK

mitogen‐activated protein kinase

- p‐ERK

phospho‐ERK

- PKA

protein kinase A

- p‐RXRα

retinoid X receptor protein

- RAR

retinoic acid receptor

- RARE

retinoic acid receptor responsive element

- RXR

retinoid X receptor

- RXRE

retinoid X receptor responsive element

- SXR

steroid and xenobiotic receptor

- TUNEL

terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase‐meditated dUTP nick‐end labeling

- VK2

vitamin K2.

HCC is a major healthcare problem worldwide because it is the fifth leading cause of cancer mortality and the third most common cause of cancer‐related death.( 1 ) The development of HCC is frequently associated with chronic inflammation of the liver induced by a persistent infection with the hepatitis B virus or hepatitis C virus. Owing to the high incidence of recurrence, the prognosis for patients with HCC is poor. Therefore, even in early stage cases when surgical treatment might be expected to be curative, the incidence of recurrence in patients with underlying cirrhosis is approximately 20–25% every year.( 2 , 3 ) In addition, at least, one‐third of the secondary tumors are primary de novo cancers.( 4 ) Therefore, strategies to prevent a second primary HCC are required to improve the prognosis for patients with HCC.( 5 ) However, at the present time there are no established chemopreventive and chemotherapeutic agents for HCC.

Retinoids, a group of structural and functional analogs of vitamin A, exert fundamental effects on the regulation of epithelial cell growth, differentiation and development.( 6 , 7 ) Retinoids exert their biological function primarily through two distinct nuclear receptors, RAR and RXR, both of which are composed of three subtypes (α, β and γ).( 6 , 7 ) Nuclear retinoid receptors are ligand‐dependent transcription factors that bind to RARE and RXRE, which are present in the promoter regions of retinoid responsive target genes.( 6 , 7 ) Abnormalities in the expression and function of both RAR and RXR play an important role in influencing the growth of various cancers. Indeed, we previously found a malfunction of RXRα, due to post‐translational modification by phosphorylation, to be associated with carcinogenesis in the liver.( 8 , 9 ) In addition, we previously reported that ACR, a novel synthetic retinoid, inhibits experimental liver carcinogenesis and induces apoptosis in human HCC‐derived cells.( 10 , 11 , 12 ) A clinical trial demonstrated that the administration of ACR reduced the incidence of a post‐therapeutic recurrence of HCC and improved the survival rate of patients, without causing significant adverse side‐effects.( 13 , 14 , 15 ) It is also of interest that ACR acts synergistically with interferon and OSI‐461, a potent derivative of sulindac sulfone, in suppressing growth and inducing apoptosis in human HCC‐derived cells.( 16 , 17 ) Therefore, ACR may be a valuable agent in the chemoprevention and chemotherapy of HCC and its efficacy may be enhanced by combination with agents that target other signaling pathway in hepatoma cells.

Recent studies have reported that VK2 can exert growth‐inhibitory effects in a variety of human cancer cells, including HCC.( 18 , 19 , 20 ) A recent clinical trial demonstrated that oral administration of VK2 reduced the development and recurrence rates of HCC, thus improving the overall survival of patients.( 21 , 22 ) Although the precise mechanism of how VK2 exerts its growth‐inhibitory effects on cancer cells has not yet been determined, there are some reports that the combined treatment of VK2 plus retinoid exerts synergistic anticancer effects.( 23 , 24 ) In view of these observations, there has been considerable interest in utilizing the combination of ACR and VK2 for the prevention and treatment of HCC. The aim of the present study is to investigate whether the combination of retinoids, ACR or 9cRA, plus VK2 exerts synergistic growth‐inhibitory effects on human HCC cells and to examine possible mechanisms for such synergy. In the present study, we examined in detail the effects of such combined treatments on the inhibition of cell growth in HuH‐7 human HCC cells, which express high levels of phosphorylated forms of p‐RXRα with a focus on the Ras/MAPK signaling pathway.( 8 )

Materials and Methods

Materials. ACR (NIK333) was supplied by Kowa Pharmaceutical Company (Tokyo, Japan). 9cRA was purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St Louis, MO, USA). VK2 was from Eisai Co. (Tokyo, Japan). Polyclonal anti‐RXRα (DN197) antibody was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Polyclonal anti‐ERK antibody and polyclonal anti‐p‐ERK antibody were from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA, USA). Monoclonal antibody against GAPDH was from Chemicon International (Temecula, CA, USA). RPMI‐1640 media and FCS were both from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA). CS‐C complete medium was from CellSystems Biotechnologie Vertrieb (St Katharinen, Germany).

Cell lines and cell culture. The HuH7 human HCC cell line was obtained from the Japanese Cancer Research Resources Bank (Tokyo, Japan) and was maintained in RPMI‐1640 medium supplemented with 10% FCS. The Hc human normal hepatocyte cell line was purchased from Applied Cell Biology Research Institute (Kirkland, WA, USA) and was maintained in CS‐C complete medium. Cells were cultured in an incubator with humidified air with 5% CO2 at 37°C.

Cell proliferation assays. Two thousand HuH7 or Hc cells were seeded into 96‐well plates in RPMI‐1640 medium supplemented with 1% FCS or CS‐C complete medium, respectively, and 72 h later they were treated with 10 µM 9cRA or 5 µM ACR in the presence or absence of 10 µM VK2. As an untreated solvent control, the cells were treated with ethanol (Sigma Chemical Co.) at a final concentration of 0.05%. The numbers of viable cells in replica plates were then counted using the Trypan Blue dye exclusion method, as described previously.( 16 ) All assays were carried out in triplicate, and mean values were plotted. To determine whether the combined effects of retinoids plus VK2 were synergistic, HuH7 cells were treated with ACR alone, 9cRA alone, VK2 alone, or a combination of the indicated concentrations of these agents for 72 h, and the combination index‐isobologram was then calculated and used in the drug combination assays.( 17 , 25 )

TUNEL assays. HuH7 cells were treated with 1.0 µM 9cRA or 1.0 µM ACR in the presence or absence of 10 µM VK2 for 48 h on coverslips. The cells were fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde at room temperature for 10 min, permeabilized with 0.3% Triton X‐100 in Tris‐buffered saline (pH 7.4), and then stained using a TUNEL method with the In Situ Cell Death Detection Kit, Fluorescein (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany), as described previously.( 16 )

Protein extraction and western blot analysis. Total cellular protein was extracted and equivalent amounts of protein were examined by western blot analysis using specific antibodies, as described previously.( 8 ) The protein concentrations in the samples were determined using the BCA Protein Assay Reagent Kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA). For detection of its expression levels, p‐RXRα was affinity purified from the total cell extracts using anti‐RXRα antibody‐immobilized Sepharose beads and was then subjected to western blot analysis using an antiphosphoserine antibody.( 8 ) An antibody to GAPDH was used as a loading control. Each membrane was developed using an ECL™ Western blotting detection reagents (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ, USA). The intensities of the blots were quantified using the NIH image software package version 1.61.

Ras activation assay. The ras activities were determined using a Ras activation assay kit (Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Ras was precipitated in equivalent amounts of cell extract (15 µg) using Raf‐1/Ras‐binding domain‐immobilized agarose and was then subjected to western blot analysis using an anti‐Ras antibody.( 8 )

RARE and RXRE reporter assays. Reporter assays were carried out as described previously.( 8 ) The RXRE–luciferase reporter plasmid tk‐CRBP II‐RXRE‐Luc and the RARE–luciferase reporter plasmid tk‐CRBP II‐RARE‐Luc were kindly provided by the late Dr K. Umesono (Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan). The HuH7 cells were transfected with the RXRE or RARE reporter plasmids (750 ng/35 mm‐dish), along with pRL‐CMV (Renilla luciferase, 100 ng/35 mm‐dish; Promega, Madison, WI, USA) as an internal standard to normalize the transfection efficiency. Transfections were carried out using the UniFector reagent (B‐Bridge, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. After exposure of the cells to the transfection mixture for 24 h, the cells were treated with vehicle, 1.0 µM 9cRA, or 1.0 µM ACR in the presence or absence of 10 µM VK2 for 24 h. Thereafter, the cell lysates were prepared and the luciferase activity of each cell lysate was determined using a dual‐luciferase reporter assay system (Promega), as described previously.( 8 ) Changes in the firefly luciferase activity were calculated and plotted after normalization with changes in the Renilla luciferase activity in the same sample.

Statistical analysis. The data are expressed as the mean values SD. The statistical significance of differences in the mean values was assessed using one‐way ANOVA, followed by Sheffe's t‐test.

Results

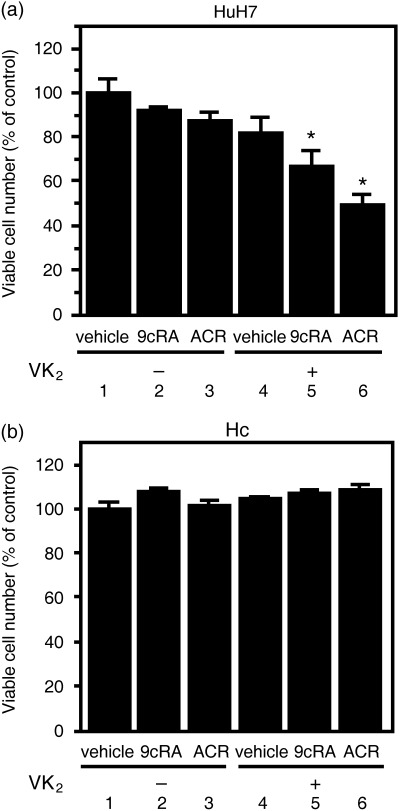

Combined treatment of retinoids plus VK2 preferentially inhibits the growth of HuH7 human HCC cells. In our initial study we examined the growth‐inhibitory effects of the combination of retinoids plus VK2 in the HuH7 human HCC cell line and Hc normal human hepatocyte cell line (Fig. 1). We found that although 9cRA alone (10 µM), ACR alone (5 µM) or VK2 alone (10 µM) could not inhibit the growth of HuH7 cells, the combination of ACR or 9cRA plus VK2 significantly inhibited the growth of these HCC cells (Fig. 1a, columns 5 and 6). However, growth of the Hc cell line was not affected by treatment with 9cRA, ACR, VK2 or the combination of these agents (Fig. 1b).

Figure 1.

Effect of retinoids and vitamin K2 (VK2) on the proliferation of (a) HuH7 human hepatocellular carcinoma cells and (b) Hc human normal hepatocytes. HuH7 cells and Hc cells were cultured for 72 h in the presence of vehicle (column 1), 10 µM 9‐cis‐retinoic acid (9cRA) (column 2), 5 µM acyclic retinoid (ACR) (column 3), 10 µM VK2 (column 4), the combination of 10 µM VK2 plus 10 µM 9cRA (column 5), or the combination of 10 µM VK2 plus 5 µM ACR (column 6). Cell number was determined using the Trypan Blue dye exclusion method and expressed as a percentage vehicle. Values are the mean ± SD (n = 5). An asterisk represents significant differences (P < 0.01) compared to vehicle (column 1). Similar results were obtained in a repeat experiment.

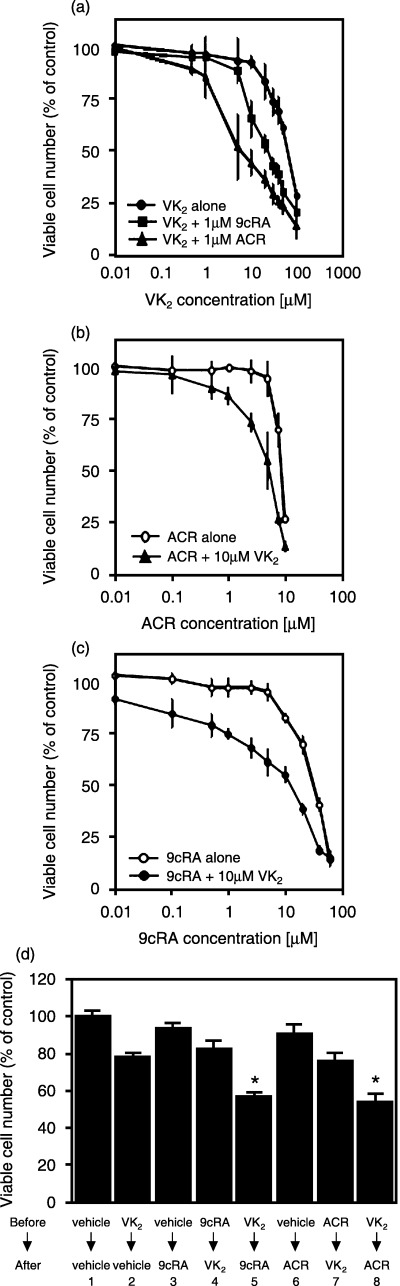

Retinoids plus VK2 synergistically inhibits the proliferation of HuH7 cells. We then examined the effects of combined treatment with a range of concentrations of 9cRA or ACR plus VK2 on the growth of HuH7 cells (Fig. 2a–c). We initially found that VK2, ACR and 9cRA inhibited growth of the HuH7 cells with IC50 values of approximately 80 (Fig. 2a), 9.4 (Fig. 2b) and 33 µM (Fig. 2c), respectively, when the cells were grown in RPMI‐1640 medium supplemented with 10% FCS. We also found that the combination of as little as 1.0 µM ACR or 1.0 µM 9cRA plus 10 µM VK2 exerted synergistic growth inhibition. Therefore, when analyzed by the isobologram method,( 17 , 25 ) the combination index for 1.0 µM ACR plus 10 µM VK2 or for 1.0 µM 9cRA plus 10 µM VK2 was less than 0.9, which indicates that there is a synergy between these combinations (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Inhibition of cell growth by retinoids, vitamin K2 (VK2) and the combination of these agents in HuH7 cells. (a) The cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of VK2 in the presence or absence of 1.0 µM acyclic retinoid (ACR) or 1.0 µM 9‐cis‐retinoic acid (9cRA) in 96‐well plates for 72 h. (b) The cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of (b) ACR or (c) 9cRA in the presence or absence of 10 µM VK2 in 96‐well plates for 72 h. (d) Effects of sequential treatment with VK2 and retinoids on the proliferation of HuH7 cells. The cells were cultured for the initial 24 h in the presence of vehicle, 1.0 µM 9cRA, 1.0 µM ACR or 10 µM VK2, and subsequently incubated for another 24 h with one of these agents, as indicated. Cell number was then determined using the Trypan Blue dye exclusion method and expressed as a percentage vehicle. Values are the mean ± SD (n = 5). Similar results were obtained in a repeat experiment. Asterisks represent significant difference (P < 0.05) compared to column 1.

We next examined whether retinoids might enhance the growth‐inhibitive effect of VK2 or, alternatively, whether VK2 might amplify the antiproliferative effect of the retinoids (Fig. 2d). HuH7 cells were first exposed to either 1.0 µM retinoids or 10 µM VK2 for 24 h, followed by incubation with the second respective agent for another 24 h. As shown in Fig. 2d, a significant reduction in the number of viable cells was found only when retinoids followed the VK2 treatment (columns 5 and 8), but treatment with these agents in the reverse order did not yield a synergistic effect (columns 4 and 7). From these results, we speculated that VK2 might enhance the sensitivity of the cancer cells to retinoids.

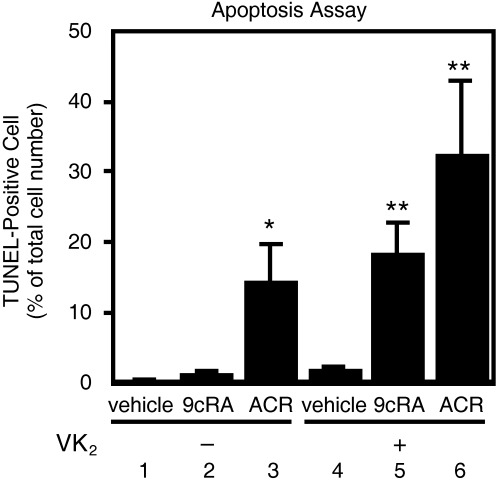

VK2 plus retinoids act synergistically to induce apoptosis in HuH7 cells. We then examined whether the synergistic growth inhibition by the combined treatment of VK2 plus retinoids (1, 2) was associated with the induction of apoptosis. We counted TUNEL‐positive cells, which indicate DNA fragmentation, and found that the treatment of HuH7 cells with either 1.0 µM ACR alone or the combination of 1.0 µM 9cRA plus 10 µM VK2 induced apoptosis in 15% of the total remaining cells (Fig. 3, columns 3 and 5), whereas no significant changes were observed in 1.0 µM 9cRA alone or 10 µM VK2 alone (Fig. 3, columns 2 and 4). Moreover, the combination of ACR plus VK2 markedly enhanced the induction of apoptosis to 33% (Fig. 3, column 6). These results strongly suggest synergism in inducing apoptosis by the combination of retinoids and VK2.

Figure 3.

Effects of the combination of retinoids plus vitamin K2 (VK2) on the induction of apoptosis in HuH7 cells. The cells were treated for 48 h with vehicle (column 1), 1.0 µM 9‐cis‐retinoic acid (9cRA) (column 2), 1.0 µM acyclic retinoid (ACR) (column 3), 10 µM VK2 (column 4), the combination of 10 µM VK2 plus 1.0 µM 9cRA (column 5), or the combination of 10 µM VK2 plus 1.0 µM ACR (column 6). The cells were then stained using a terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase‐meditated dUTP nick‐end labeling (TUNEL) method, and TUNEL‐positive cells were counted and expressed as a percentage of total cell numbers (500 cells were counted in each flask). Values are the mean ± SD (n = 5). Asterisks represent significant difference (P < 0.05) compared to column 1. Representative results from three independent experiments with similar results are shown.

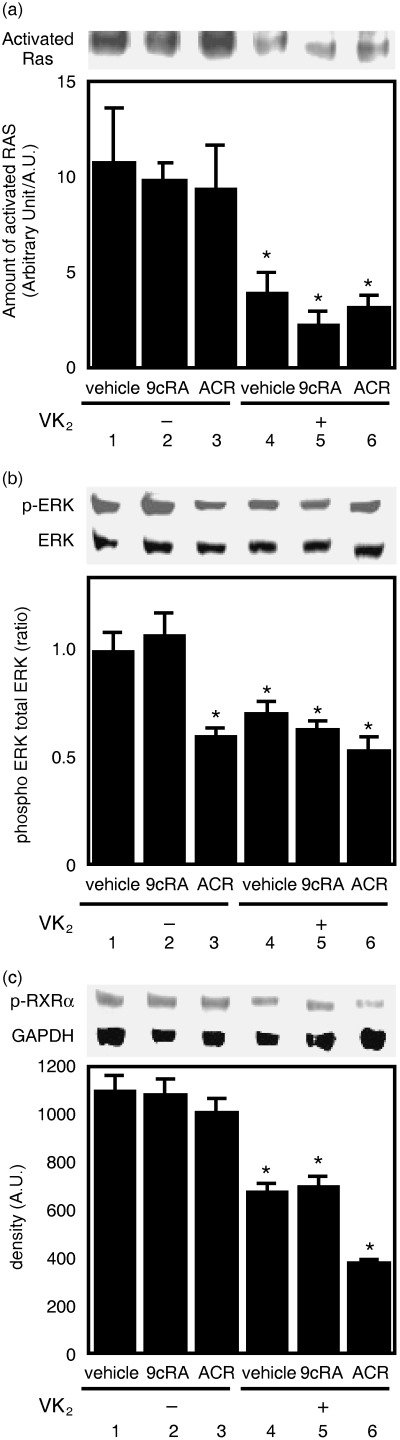

Retinoids and VK2 inhibit activation of ras and the phosphorylation of ERK and RXRα proteins in HuH7 cells. Our previous work suggested that a malfunction of RXRα due to aberrant phosphorylation is associated with liver carcinogenesis.( 8 , 9 ) Phosphorylation of p‐RXRα is caused mainly by activation of the Ras/MAPK signaling pathway in HCC cells.( 8 , 9 ) Therefore, we examined whether the combined treatment of retinoids plus VK2 downregulates the Ras/MAPK signaling pathway and inhibits phosphorylation of p‐RXRα in HuH7 cells. As shown in Fig. 4a, Raf‐1‐bound Ras activities were significantly inhibited when the cells were treated with 10 µM VK2 alone and with the combination of VK2 plus 1.0 µM 9cRA or 1.0 µM retinoids (lanes and columns 4–6). The expression levels of phosphorylated (i.e. activated) forms of the ERK protein were also decreased when the cells were treated with ACR alone, VK2 alone, or the combination of VK2 plus retinoids (Fig. 4b, lanes and columns 3–6). Moreover, treatment of the cells with VK2 alone or the combination of VK2 plus retinoids caused a marked decrease in the expression level of p‐RXRα (Fig. 4c, lanes and columns 4–6). This decrease was most apparent when the cells were treated with a combination of 1.0 µM ACR plus 10 µM VK2 (Fig. 4c, lane and column 6).

Figure 4.

Inhibition of Ras activation and phosphorylation of the extracellular signal‐regulated kinase (ERK) and retinoid X receptor (RXR)α proteins by the combination of vitamin K2 (VK2) plus retinoids in HuH7 cells. After the cells were treated for 72 h with the indicated concentrations and combinations of retinoids plus VK2 as described in the legend of Fig. 3, whole cell lysates were then prepared. (a) Ras was precipitated from the cell lysates using Raf/Ras binding domain‐immobilized agarose and then subjected to western blot analysis using an anti‐Ras specific antibody. Relative intensity of the bands was quantitated by densitometry and is displayed in the lower panel. (b,c) Western blot analysis for the phospho‐ERK (p‐ERK) and RXRα proteins. The cell extracts were examined by western blot analysis, and the results for (b) p‐ERK and ERK or for (c) RXRα protein and glyceraldehyde‐3‐phosphate dehydrogenase were quantitated by densitometry, and the ratios of these proteins are displayed in the lower panel. Values are the mean ± SD (n = 5). Asterisks represent significant differences (P < 0.01) compared with vehicle‐treated cells. Representative results from three independent experiments with similar results are shown.

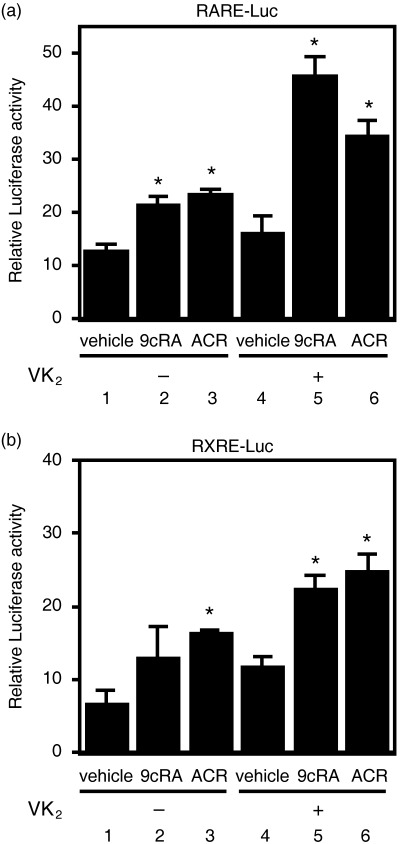

VK2 enhances the stimulation of both RARE and RXRE promoter activities produced by retinoids. RAR and RXR modulate the expression of target genes by interacting with RARE or RXRE located in the promoter regions of target genes.( 6 , 7 ) Therefore, we next examined whether VK2 might enhance the transcriptional activity of the RARE or RXRE promoters using transient transfection luciferase reporter assays. We found that 1.0 µM 9cRA alone caused an increase in RARE reporter activity (Fig. 5a, column 2) and 1.0 µM ACR alone caused an increase in both RARE and RXRE reporter activities (Fig. 5, columns 3). VK2 alone (10 µM) did not have an effect on the transcriptional activity of these responsive elements (Fig. 5, columns 4). However, when VK2 was combined with these retinoids, there was a synergistic increase in the transcriptional activity of these luciferase reporter activities (Fig. 5, columns 5 and 6).

Figure 5.

Effects of the combination of retinoids plus vitamin K2 (VK2) on transcriptional activity of retinoid X receptor responsive element (RXRE) and RXRE promoters in HuH7 cells. The cells were cotransfected with vectors expressing the (a) retinoic acid receptor responsive element (RARE)–luciferase reporter gene or (b) RXRE–luciferase reporter gene, along with pRL‐CMV as an internal standard using lipofection. The transfected cells were then treated for 24 h with the indicated concentrations and combinations of retinoids plus VK2 as described in the legend of Fig. 3. Thereafter, the cell lysates were prepared and the relative luciferase activity of each cell lysate was measured and plotted as fold induction compared with the activity in vehicle after normalization to Renilla luciferase activity. Values are the mean ± SD (n = 5). Asterisks represent significant differences (P < 0.01) compared with vehicle‐treated cells. Representative results from three independent experiments with similar results are shown.

Discussion

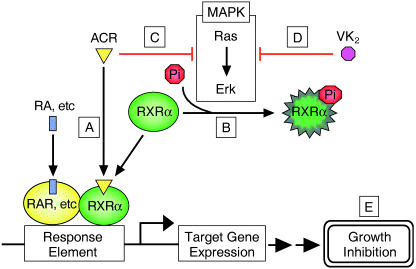

In the present study we found that the combination of retinoids (especially ACR) plus VK2 caused the synergistic inhibition of growth in human hepatoma HuH7 cells (1, 2) and that this was associated with the induction of apoptosis (Fig. 3). These findings are consistent with recent published results showing that retinoids have a synergistic growth‐inhibitory effect when combined with VK2 in leukemia cells, with an enhanced therapeutic benefit.( 23 , 24 ) However, the precise mechanisms of how the combination of retinoids plus VK2 could cause this preferable effect have not yet been determined. A hypothetical scheme that addresses this question is shown in Fig. 6. This scheme emphasizes cooperative inhibition of the Ras/MAPK signaling pathway by retinoids plus VK2 in HCC cells. In HCC cells, but not in normal hepatocytes, the Ras/MAPK signaling pathway is highly activated and phosphorylates RXRα, thus impairing the functions of this receptor.( 8 , 9 ) These findings indicate that p‐RXRα may be a useful target for inhibiting the growth of HCC cells. As shown in our present (Fig. 4) and previous studies,( 8 , 26 ) retinoids can inhibit Raf‐1‐bound Ras activity and phosphorylation of the ERK protein. We found in this study that VK2 itself also inhibits the Ras/MAPK signaling pathway via inhibition of Ras activation, thus causing a decrease in the levels of p‐ERK and p‐RXRα (Fig. 4). In a previous study we found that the accumulation of non‐functional p‐RXRα interfered with the function of remaining normal p‐RXRα in a dominant‐negative manner, thereby promoting the growth of hepatoma cells.( 8 ) Therefore, our finding in the present study that the combination of retinoids plus VK2 synergistically inhibits the phosphorylation of p‐RXRα seems to be very significant in the inhibition of HCC growth, without affecting the growth of normal hepatocytes (Fig. 1).

Figure 6.

Schematic representation of the effect of vitamin K2 (VK2) and acyclic retinoid (ACR) on retinoid X receptor (RXR)α phosphorylation in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. (a) In normal hepatocytes, ACR binds to RXRα and transactivates downstream genes via retinoid X receptor responsive element (RXRE), which may regulate cell proliferation. (b) In hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) cells, the Ras/mitogen‐activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway is highly activated and phosphorylates RXRα at serine residues, thus impairing the functions of the receptor. (c) ACR and (d) VK2 cooperatively suppress the Ras/MAPK signaling pathway, inhibit phosphorylation of RXRα, restore the function of the receptor, and thus subsequently activate the transcriptional activity of the responsive element, including RXRE. (e) These effects may contribute to growth inhibition of the hepatoma cells.

We also found in the present study that VK2 enhances binding of retinoids to the RARE and RXRE promoters, thereby enhancing transcriptional activity (Fig. 5). As previously noted, the restoration of the function of RXR as a master regulator for nuclear receptors, by inhibiting the Ras/MAPK signaling pathway (Fig. 4), was thus considered to possibly play a role in these promoter activities. However, there are reports that VK2 itself also works as a transcriptional regulator in addition to its role as an enzyme cofactor. For instance, VK2 inhibits growth and invasiveness of HCC cells via the activation of protein kinase A, which modulates the activation of several transcriptional factors.( 19 ) Tabb et al. reported that VK2 binds directly to the nuclear receptor SXR, which can dimerize with RXR and regulate the transcription of target genes, thus transcriptionally activating this receptor in a dose‐dependent manner.( 27 ) Moreover, RXR serves as an active partner of SXR and retinoids can activate the RXR/SXR‐mediated pathway and regulate the expression of target genes.( 28 ) Further studies are required to clarify whether both retinoids and VK2 synergistically exert their growth‐inhibitory effects in cancer cells at the level of transcription, especially focusing on the regulation of transcription factors and the expression of target genes located in the RXR/SXR‐mediated downstream signaling pathway.

Although clinical studies suggest that VK2 has a suppressive effect on the development and recurrence of HCC,( 21 , 22 ) the precise mechanism by which VK2 causes these antiproliferative effects in HCC cells remains to be determined. However, the structure of VK2 may play a role in the induction of apoptosis because geranylgeraniol, which is a side chain of VK2, strongly induces apoptosis in tumor cells.( 29 ) Such a report seems to be of interest as ACR also has geranylgeraniol in its side chain, thus suggesting that the synergistic induction of apoptosis caused by ACR plus VK2 (Fig. 3) may be associated with their similar structure. In addition, VK2 can cause an increase of cells in the G1 phase of the cell cycle in HCC cells( 30 , 31 ) and similar effects are also caused by ACR.( 17 , 32 ) These findings suggest that the combination of these agents might synergistically induce antitumor effects in HCC cells via the induction of cell cycle arrest. Therefore, in future studies it will be of interest to further examine the effects of ACR plus VK2 on cell cycle progression and on the expression of cell cycle control molecules including cyclin D1 or p21CIP1, which are target molecules of ACR.( 17 , 32 )

The chemoprevention of HCC must improve the prognosis for patients( 5 ) because this cancer has a high frequency of recurrence even after patients undergo curative therapy.( 2 , 3 ) Safety is critical when agents are applied as chemopreventive drugs in clinical use. A clinical trial demonstrated that the administration of both ACR and VK2 reduced the incidence of post‐therapeutic recurrence of HCC and improved the survival rate of patients without causing any untoward effects.( 13 , 14 , 15 , 22 ) Pharmacokinetic studies in clinical trials also indicate that the plasma concentrations of ACR and VK2 are approximately the same as the dosages that we used in the present study.( 13 , 33 ) In addition, our finding that the combination of appropriate dosages of ACR and VK2 can inhibit the growth of human HCC cells without affecting the growth of normal hepatocytes (Fig. 1) should encourage further clinical studies using these materials to investigate HCC prevention and treatment. The safety and efficacy for the combination of VK2 plus other agents were also demonstrated in an in vivo study. The antitumor activity of VK2 was enhanced when it was combined with perindooril, the antihypertensive drug, in a rat chemical‐induced liver carcinogenesis model without causing any toxicities.( 20 ) In conclusion, these reports, together with the results of our in vitro mechanistic studies on HCC cells as described in the present paper, suggest that combining specific retinoids (especially ACR) with VK2 might hold promise as a clinical modality for the prevention and treatment of HCC, due to their synergistic effects.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by a Grant‐in‐Aid from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture of Japan (no. 18790457 to M. S. and no. 17015016 to H. M.).

References

- 1. Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. Estimating the world cancer burden: Globocan 2000. Int J Cancer 2001; 94: 153–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kumada T, Nakano S, Takeda I et al. Patterns of recurrence after initial treatment in patients with small hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 1997; 25: 87–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Koda M, Murawaki Y, Mitsuda A et al. Predictive factors for intrahepatic recurrence after percutaneous ethanol injection therapy for small hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer 2000; 88: 529–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chen YJ, Yeh SH, Chen JT et al. Chromosomal changes and clonality relationship between primary and recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology 2000; 119: 431–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Okuno M, Kojima S, Moriwaki H. Chemoprevention of hepatocellular carcinoma: concept, progress and perspectives. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2001; 16: 1329–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chambon P. A decade of molecular biology of retinoic acid receptors. FASEB J 1996; 10: 940–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Altucci L, Gronemeyer H. The promise of retinoids to fight against cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2001; 1: 181–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Matsushima‐Nishiwaki R, Okuno M, Adachi S et al. Phosphorylation of retinoid X receptor α at serine 260 impairs its metabolism and function in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res 2001; 61: 7675–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Matsushima‐Nishiwaki R, Shidoji Y, Nishiwaki S, Yamada T, Moriwaki H, Muto Y. Aberrant metabolism of retinoid X receptor proteins in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol Cell Endocrinol 1996; 121: 179–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Muto Y, Moriwaki H. Antitumor activity of vitamin A and its derivatives. J Natl Cancer Inst 1984; 73: 1389–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Nakamura N, Shidoji Y, Yamada Y, Hatakeyama H, Moriwaki H, Muto Y. Induction of apoptosis by acyclic retinoid in the human hepatoma‐derived cell line, HuH‐7. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1995; 207: 382–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yasuda I, Shiratori Y, Adachi S et al. Acyclic retinoid induces partial differentiation, down‐regulates telomerase reverse transcriptase mRNA expression and telomerase activity, and induces apoptosis in human hepatoma‐derived cell lines. J Hepatol 2002; 36: 660–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Muto Y, Moriwaki H, Ninomiya M et al. Prevention of second primary tumors by an acyclic retinoid, polyprenoic acid, in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatoma prevention study group. N Engl J Med 1996; 334: 1561–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Muto Y, Moriwaki H, Saito A. Prevention of second primary tumors by an acyclic retinoid in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med 1999; 340: 1046–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Takai K, Okuno M, Yasuda I et al. Prevention of second primary tumors by an acyclic retinoid in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Updated analysis of the long‐term follow‐up data. Intervirology 2005; 48: 39–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Obora A, Shiratori Y, Okuno M et al. Synergistic induction of apoptosis by acyclic retinoid and interferon‐β in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Hepatology 2002; 36: 1115–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Shimizu M, Suzui M, Deguchi A et al. Synergistic effects of acyclic retinoid and OSI‐461 on growth inhibition and gene expression in human hepatoma cells. Clin Cancer Res 2004; 10: 6710–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lamson DW, Plaza SM. The anticancer effects of vitamin K. Altern Med Rev 2003; 8: 303–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Otsuka M, Kato N, Shao RX et al. Vitamin K2 inhibits the growth and invasiveness of hepatocellular carcinoma cells via protein kinase A activation. Hepatology 2004; 40: 243–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yoshiji H, Kuriyama S, Noguchi R et al. Combination of vitamin K2 and the angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor, perindopril, attenuates the liver enzyme‐altered preneoplastic lesions in rats via angiogenesis suppression. J Hepatol 2005; 42: 687–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Habu D, Shiomi S, Tamori A et al. Role of vitamin K2 in the development of hepatocellular carcinoma in women with viral cirrhosis of the liver. JAMA 2004; 292: 358–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mizuta T, Ozaki I, Eguchi Y et al. The effect of menatetrenone, a vitamin K2 analog, on disease recurrence and survival in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma after curative treatment: a pilot study. Cancer 2006; 106: 867–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sakai I, Hashimoto S, Yoda M et al. Novel role of vitamin K2: a potent inducer of differentiation of various human myeloid leukemia cell lines. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1994; 205: 1305–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yaguchi M, Miyazawa K, Katagiri T et al. Vitamin K2 and its derivatives induce apoptosis in leukemia cells and enhance the effect of all‐trans retinoic acid. Leukemia 1997; 11: 779–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Soriano AF, Helfrich B, Chan DC, Heasley LE, Bunn PA Jr, Chou TC. Synergistic effects of new chemopreventive agents and conventional cytotoxic agents against human lung cancer cell lines. Cancer Res 1999; 59: 6178–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Matsushima‐Nishiwaki R, Okuno M, Takano Y, Kojima S, Friedman SL, Moriwaki H. Molecular mechanism for growth suppression of human hepatocellular carcinoma cells by acyclic retinoid. Carcinogenesis 2003; 24: 1353–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tabb MM, Sun A, Zhou C et al. Vitamin K2 regulation of bone homeostasis is mediated by the steroid and xenobiotic receptor SXR. J Biol Chem 2003; 278: 43 919–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wang K, Mendy AJ, Dai G, Luo HR, Lin H, Wan YJ. Retinoids activate the RXR/SXR‐mediated pathway and induce the endogenous CYP3A4 activity in Huh7 human hepatoma cells. Toxicol Sci 2006; 92: 51–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ohizumi H, Masuda Y, Nakajo S, Sakai I, Ohsawa S, Nakaya K. Geranylgeraniol is a potent inducer of apoptosis in tumor cells. J Biochem (Tokyo) 1995; 117: 11–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hitomi M, Yokoyama F, Kita Y et al. Antitumor effects of vitamins K1, K2 and K3 on hepatocellular carcinoma in vitro and in vivo . Int J Oncol 2005; 26: 713–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kuriyama S, Hitomi M, Yoshiji H et al. Vitamins K2, K3 and K5 exert in vivo antitumor effects on hepatocellular carcinoma by regulating the expression of G1 phase‐related cell cycle molecules. Int J Oncol 2005; 27: 505–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Suzui M, Masuda M, Lim JT, Albanese C, Pestell RG, Weinstein IB. Growth inhibition of human hepatoma cells by acyclic retinoid is associated with induction of p21 (CIP1) and inhibition of expression of cyclin D1. Cancer Res 2002; 62: 3997–4006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ishii M, Shimomura M, Hasegawa J et al. Multiple dose pharmacokinetic study of soft gelatin capsule of menatetrenone (Ea‐0167) in elderly and young volunteers. Jpn Pharmacol Ther 1995; 23: 2637–42. [Google Scholar]