Abstract

Field cancerization currently described the theory of tumorigenesis and, until now, has been described in almost all organ systems except in liver. For this reason, we explore the presence of field cancerization in liver and its underlying clinical implication in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). In our study, methylation profile of HCC and surgically resected margin (SRM) were established by methylation‐specific PCR. Liver cirrhosis (LC), chronic hepatitis and normal liver were treated in the same way as the background control. The correlation analysis among the methylation profile of HCC, SRM and clinicopathological data of HCC patients was made respectively. Our results showed that methylation abnormities related to HCC, but not background disease existed in histologically negative SRM. Monoclonal and polyclonal models may coexist in field cancerization in liver. Patients with RIZ1 methylation in SRM had a shorter disease free survival. The local recurrence trend of early and later recurrence in HCC is potentially related to a second field tumor. From these results, we can suggest that field cancerization exists in liver. The study of field cancerization in liver plays an important role in hepatocarcinogenesis. Second field tumor derived form field cancerization may have important implications in HCC prognosis assessment that is worthy of further study. (Cancer Sci 2009; 100: 996–1004)

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is one of the most common malignancies in the world and among the most fatal of human neoplasms, but the molecular mechanisms that lead to hepatocarcinogenesis are primarily unknown.

Field cancerization is an accepted theory about tumorigenesis, which was first introduced by Slaughter( 1 ) in 1953 when he was studying oral cancer. Many recent studies have provided unequivocal evidence to support this theory, most of which are characterized in human. Field cancerization is defined as a cancer begins with multiple cumulative epigenetic and genetic alterations that transform a cell or a group of cells in a particular organ. The early genetic events lead to monoclonal or polyclonal expansion of preneoplastic daughter cells in a particular tumor field. Subsequent genomic changes in some of these cells drive them towards the malignant phenotype. A population of daughter cells with early genetic changes (without histopathology) remains in the organ, is able to progress and might become another malignant tumor. The subsequent transforming tumor is referred to as a second field tumor (SFT).( 2 ) This theory not only can be used to explain how multiple tumors develop, but also has important clinical implication. Focused on the initiation of the disease, the study of field cancerization can lead to discoveries of new biomarkers that could be useful in risk assessment, early detection, disease monitoring, and surrogate endpoint in chemoprevention trials.( 3 ) Until now, field cancerization has been described in many organ systems such as the esophagus,( 4 ) lung,( 5 ) stomach,( 6 ) colon( 7 ) and breast,( 8 ) but has not been thoroughly studied in liver.

Recently, aberrant promoter hypermethylation has been shown to be a common event in human cancer due to functional loss of the tumor suppressor genes (TSG). Remarkably, this neoplastic‐related DNA methylation is regarded as an early event in tumorigenesis( 9 ) and tumor type specificity.( 10 ) It would be, therefore, an ideal method for us to probe into field cancerization.

Intend to explore the presence of field cancerization in liver, eight TSGs were selected for their involvement in multiple tumor pathways and frequent epigenetic inactivation in tumors of the digestive system. We examined the methylation status of these 8 genes in samples from 60 pairs of HCC and their corresponding surgically recsected margins (SRM), 16 cases of liver cirrhosis (LC) secondary to hepatitis, 5 cases of chronic hepatitis (CH) and 5 cases of normal liver (NL) using a methylation‐specific polymerase chain reaction (MSP) assay. Methylation frequencies in different liver tissues were compared, as well as the clonal relationship of methylation status between HCC and corresponding SRM. The results were also correlated with the findings from pathological studies to define the clinical significance of aberrant DNA methylation in both HCC and SRM.

Materials and Methods

Sample collection. With the informed consent of all patients and approval of the ethics committee, the samples of tumor and corresponding SRM (the surgically margin tissue that locate at the shortest distance to tumor in vertical direction) were collected from 60 HCC patients who underwent radical hepatectomy in the Third Center Hospital of Tianjin between 2003 and 2005. Only patients with pathological diagnosis of HCC were considered. None of patients had evidence of macroscopic or microscopic disease at the resected liver margins, so SRM of this series is also considered to be adjacent non‐cancerous tissues. LC, CH and NL samples were obtained from patients without HCC. Needle biopsied sample were obtained from 16 cases of cirrhotic liver secondary to hepatitis and 5 cases of hepatitis. In addition, normal liver tissues adjacent to hemangiomas of liver were taken from surgical resection specimens from 5 patients. As a positive control, placenta sample was obtained from uncomplicated pregnancies. All samples were stored at –80°C until analysis.

Patients and histology. Clinicopathological data of 60 HCC patients (median age, 53.5 years; 51 males and 9 females) were collected from patient records and pathology reports. Types of hepatitis and tumor biomarker were determined through serological test prior to operation. Liver function was evaluated according to Child‐Pugh criteria based on clinical findings of patients one week before surgery. The pathological classification of tumor tissues was carried out by Edmondson classification. The stage of each HCC patient was determined according to international TNM staging (6th edition)( 11 ) and Chinese staging.( 12 ) All patients were followed up from the date of surgery and the status about the recurrence and survival were recorded.

DNA extraction and sodium bisulfite modification. Genomic DNA was extracted from HCC, SRM, LC, CH and NL samples using a proteinase K treatment followed by a phenol/chloroform /isoamylalcohol extraction. One microgram of genomic DNA extracted from specimens was subjected to bisulfite treatment as described previously.( 13 ) Briefly, alkali‐denatured DNA was modified by 3 M sodium bisulfite/10 mM hydroquinone at pH 5.0. The bisulfite‐reacted DNA was subsequently treated with NaOH, purified with Wizard DNA Clean‐Up System (Promega, Hope), precipitated with ethanol, and resuspended in 1 mM TE (pH 7.6) buffer. The DNA was finally stored at –4°C before analyses by PCR.

Methylation‐specific PCR. MSP was performed to examine the methylation status at CpG islands of APC, RASSF1A, DAPK, SOCS‐1, GSTP1, RIZ1, p16 and MGMT. The primer of p16 and GSTP1 for MSP were described by Herman( 14 ) and Esteller( 15 ) with minor modification. The primers of other genes were described previously( 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 ) (Table 1). Forty‐fifty ng bisulfite modified DNA was amplified in a 25 µL volume of reaction buffer containing 0.2 mM each deoxynucleotide triphosphates, 0.4 µM of each primer and 1U of Taq DNA polymerase (Takara, Dalian). The PCR program is in a hot start reaction as follows: an initial denaturation cycle of 95°C for 5 min; followed by 35 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, primer specific annealing temperature for 40 s, an extension at 72°C for 30 s, this was followed by a final extension step of 5 min at 72°C. Initially, placenta DNA, treated in vitro with SssI methyltransferase (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA), was used as positive control for methylated genes. DNA from normal lymphocytes was used as the negative control. A water blank was used in each round of PCR. Ten microliters of each PCR product was eletrophoresed in 2.5% agarose gel, stained with ethidium bromide, and visualized under UV illumination. To verify the PCR results, representative bands from each target were gel‐purified and cloned into pMD 18‐T Vector (Takara, Dalian) followed by automatic DNA sequencing provided by Genecore (Shanghai, China). Only results verified by sequence analyses are presented in this report.

Table 1.

Primer sequences and PCR conditions for MSP analysis

| Gene | M/U | Prime sequence(5′‐3′)forward | Prime sequence(5′‐3′)reverse | product size(bp) | Tm (°C) | Gene function |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| APC | M | TATTGCGGAGTGCGGGTC | TCGACGAACTCCCGACGA | 98 | 58 | Wnt pathway |

| U | GTGTTTTATTGTGGAGTGTGGGTT | CCAATCAACAAACTCCCAACAA | 108 | 57 | ||

| RASSF1A | M | GTGTTAACGCGTTGCGTTGCGTATC | AACCCCGCGAACTAAAAACGA | 93 | 52 | cell growth factor |

| U | TTGGTTGGAGTGTGTTAATGTG | CAAACCCCACAAACTAAAAACAA | 107 | 52 | ||

| p16 | M | CGGGGAGTAGTATGGAGTCGGCG | GACCCCGAACCGCGACCGTAA | 81 | 60 | cell cycle control |

| U | GGGAGTAAGTATGGAGTTGGTGGTG | CAACCCCAAACCACAACCATAA | 80 | 55 | ||

| DAPK | M | GGATAGTCGGATCGAGTTAACGTC | CCCTCCCAAACGCCGA | 97 | 59 | apoptosis |

| U | GGAGGATAGTTGGATTGAGTTAATGTT | CAAATCCCTCCCAAACACCAA | 105 | 60 | ||

| GSTP1 | M | TTAGTTGCGCGGCGATTTC | GCCCCAATACTAAATCACGACG | 142 | 61 | repair of DNA damage |

| U | TTTTGGTTAGTTGTGTGGTGATTTTG | TGTTGTGATTTAGTATTGGGGTGGA | 151 | 55 | ||

| MGMT | M | TTTCGACGTTCGTAGGTTTTCGC | GCACTCTTCCGAAAACGAAACG | 81 | 59 | repair of DNA damage |

| U | TTTGTGTTTTGATGTTTGTAGGTTTTTGT | AACTCCACACTCTTCCAAAAACAAAACA | 93 | 59 | ||

| SOCS‐1 | M | TTCGCGTGTATTTTTAGGTCGGTC | CGACACAACTCCTACAACGACCG | 160 | 63 | inhibitor of signal pathway |

| U | TTATGAGTATTTGTGTGTATTTTTAGGTTGGTT | CACTAACAACACAACTCCTACAACAACCA | 174 | 61 | ||

| RIZ1 | M | GTGGTGGTTATTGGGCGACGGC | GCTATTTCGCCGACCCCGACG | 176 | 69 | inhibitor of cell growth |

| U | TGGTGGTTATTGGGTGATGGT | ACTATTTCACCAACCCCAAGA | 175 | 58 |

M, methylated sequence; U, unmethylated sequence.

To ensure reliable and accurate results, we took a batch‐process of samples. Template DNA amounts in each PCR reaction system was kept constant before and after bisulfite treatment and each sample was analyzed in duplicate.

Statistical analysis. Chisquare and Fisher's exact test were used to compare the frequencies of aberrations in methylation among HCC, SRM and LC. The aforementioned tests as well as the student's unpaired t‐test were used to determine the correlations between methylation status and clinicopathological data. Overall survival and disease free survival (DFS), respectively, were calculated from the date of surgery to time of death and the first confirmed recurrence. Association of methylation status in tumor and margin with overall survival and DFS were studied using a Kaplan‐Meier method with a log‐rank test to detect the statistical differences, with a value of P < 0.05 considered as significant. All statistical analysis was carried out using SPSS Software Program (version 11.0).

Results

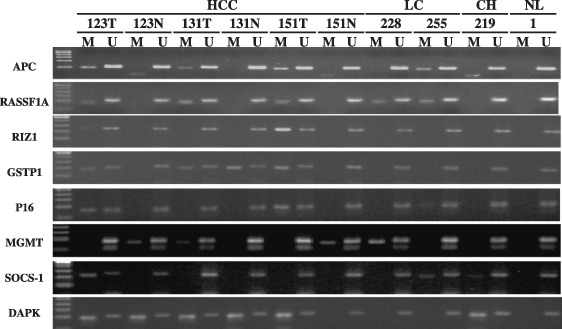

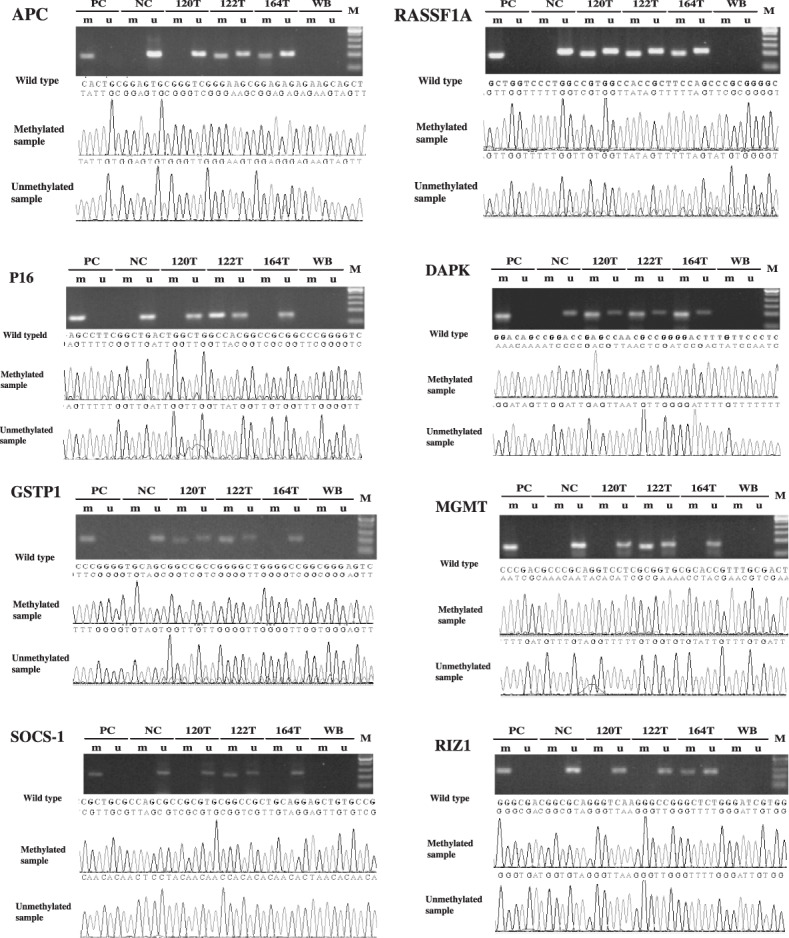

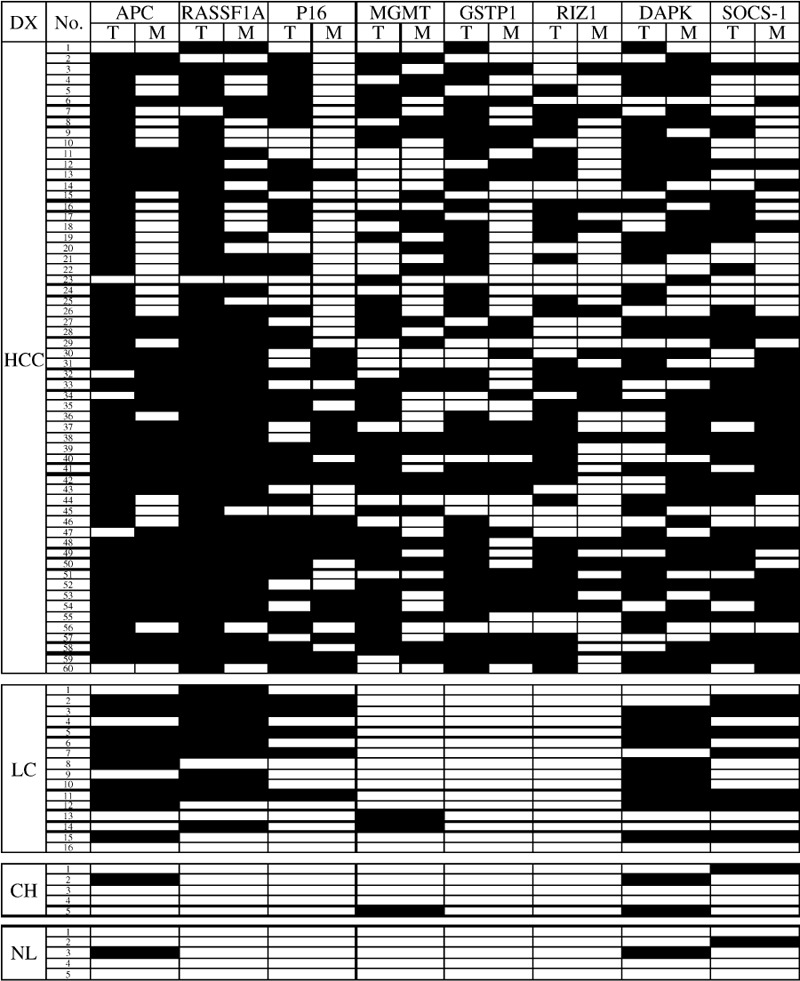

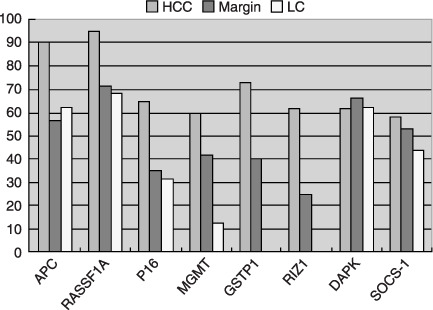

Frequency of methylation of tumor suppressor genes in various tissues. MSP method of the 8 TSGs was first established successfully (Fig. 1). Corrective nucleotide sequence and completely chemical modification were confirmed in all detected MSP products (Fig. 2). The methylation frequency of 8 genes in HCC, SRM, LC, CH and NL tissues was determined by overall MSP results (Fig. 3). The most frequently methylated TSGs in HCC were RASSF1A (95%) and APC (90%). The methylation frequencies of other TSGs were as follows: GSTP1(73.3%), p16(65%), RIZ1 (61.6%), DAPK1(61.6%), MGMT (60%) and SOCS‐1 (58.3%) (Table 2). The methylation frequency of APC`RASSF1A, MGMT p16, GSTP1 and RIZ1 was significantly higher in HCC than in SRM, which indicated closed relationship between the 6 gene methylation and HCC tumorigenesis. LC also had many aberrant methylation events like SRM, however, methylation frequency of MGMT, GSTP1 and RIZ1 was lower in LC than in SRM. GSTP1 and RIZ1 showed no indication of methylation in either LC or CH. Different from other genes, DAPK1 and SOCS‐1 had similar methylation frequency among HCC, SRM and LC (Table 2; Fig. 4). Additionally, the methylation of APC, MGMT, DAPK1 and SOCS‐1 were also found in CH and NL (Table 2).

Figure 1.

The typical MSP result of APC, RASSF1A, RIZ1, GSTP1, P16, MGMT, SOCS1, DAPK in HCC, non‐cancer margin, LC, CH and NL. HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; LC, liver cirrhosis; CH, chronic hepatitis; NL, normal liver; T, tumor; N, non‐cancer margin; M, methylated status; U, unmethylated status; Different figure indicates sample number selected stochasticly.

Figure 2.

Sequencing result of MSP product for the 8 TSGs in 3 HCC samples selected stochasticly. PC, positive control; NC, negative control; WB, water blank; M, DNA ladder; T, tumor; m, methylated status; u, unmethylated status.

Figure 3.

Summary of methylation analysis of APC, RASSF1A, p16, MGMT, GSTP1, RIZ1, DAPK1, SOCS‐1 in 146 liver samples. Filled boxes indicate the presence of methylation and open boxes indicate the absence of methylation. DX, diagnosis; T, tumor; M, margin; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; LC, liver cirrhosis; CH, chronic hepatitis; NL, normal liver.

Table 2.

Methylation frequency for eight genes in hepatocellular carcinoma, margin, liver cirrhosis, chronic hepatitis and normal liver

| Gene | Frequence of methylation %(n) | Significance* | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HCC (n = 60) | SRM (n = 60) | LC (n = 16) | CH (n = 5) | NL (n = 5) | HCC versus margin | margin versus LC | HCC versus LC | |

| APC | 90.0(54) | 56.6(34) | 62.5(10) | 20(1) | 20(1) | <0.001 | 0.675 | 0.022 |

| RASSF1A | 95.0(57) | 71.6(43) | 68.7(11) | 0 | 0 | 0.001 | 0.819 | 0.01 |

| P16 | 65.0(39) | 35.0(21) | 31.3(5) | 0 | 0 | 0.001 | 0.779 | 0.01 |

| MGMT | 60.0(36) | 41.6(25) | 12.5(2) | 20(1) | 0 | 0.045 | 0.03 | 0.01 |

| GSTP1 | 73.3(44) | 40.0(24) | 0 | 0 | 0 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| RIZ1 | 61.6(37) | 25.0(15) | 0 | 0 | 0 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| DAPK | 61.6(37) | 66.6(40) | 62.5(10) | 20(1) | 20(1) | 0.568 | 1 | 0.951 |

| SOCS‐1 | 58.3(35) | 53.3(32) | 43.7(7) | 40(2) | 20(1) | 0.581 | 0.496 | 0.297 |

HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; SRM, surgically resected margin; LC, liver cirrhosis; CH, chronic hepatitis; NL, normal liver.

Figure 4.

Comparision of methylation frequency of eight genes in hepatocellular carcinoma, margin and liver cirrhosis. HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; LC, liver cirrhosis.

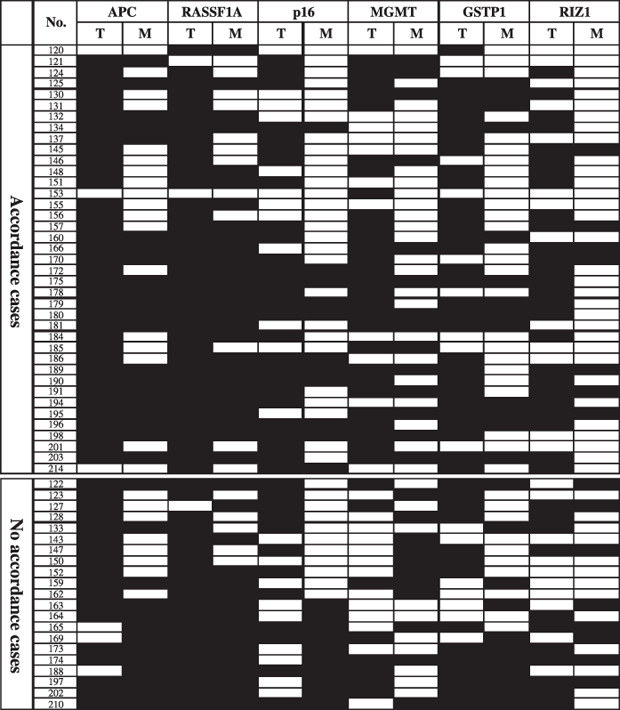

Clonal analysis of methylation status in HCC and SRM. As shown in Table 2, aberrant promoter methylation of all genes was also found in SRM, which is considered to be an epigenetic event of preneoplastic lesions surrounding the tumor. Nomoto et al.( 22 ) pointed out that hypermethylation of multiple genes also can be used as clonal marker. Therefore, we analyzed the clonal correlation of cells in both tumor and surgically resected margin. Due to the monoclonal origin, the methylation status of SRM should not be positive unless methylation of corresponding HCC is positive. This includes the phenomenon of T+M+, T+M–, T–M–, (Table 3) which can simply be regarded as accordant alterations. Despite this monoclonal origin, the phenomenon of T–M+ represents a polyclonal origin in tumor and its corresponding SRM. When analyzed in a methylation profile of 6 tumor‐related genes, the accordant methylation status of all 6 genes were found in 39 cases (65%); however, there were 21 cases (35%) existing inconsistent phenomenon in 1 to 3 genes (1 gene, 18 cases; 2 genes, 1 cases; 3 genes, 2 cases) (Fig. 5).

Table 3.

Methylation status correlation between tumor and margin

| Gene | T+M+ | T+M– | T–M+ | T–M– |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| APC | 31 | 23 | 3 | 3 |

| RASSF1A | 42 | 15 | 1 | 2 |

| P16 | 15 | 24 | 6 | 15 |

| MGMT | 16 | 20 | 9 | 15 |

| GSTP1 | 20 | 24 | 4 | 12 |

| RIZ1 | 12 | 25 | 3 | 20 |

| DAPK | 24 | 13 | 16 | 7 |

| SOCS‐1 | 23 | 12 | 9 | 16 |

T, tumor; M, margin.

Figure 5.

Accordance analysis of all six tumor‐related TSGs methylation status between tumor and surgically resected margin. Filled boxes indicates the presence of methylation and open boxes indicates the absence of methylation; T, tumor; M, margin.

Correlation between TSG methylation profile and clinicopathological data. We attempted to explore the correlation between the methylation status of the aforementioned 6 tumor‐related genes and clinicopathological features. The data of 60 HCC cases was shown in Table 4. P16 methylation was observed more frequently in HCC derived from elder patients. Additionally, the frequency of MGMT methylation tended to be higher in massive HCC than in other gross types. No other associations were found between methylation status of tumor‐related genes and the clinicopathological findings including sex, serum tumor marker, types of hepatitis virus, presence/absence of cirrhosis, tumor size, histological differentiation, international TNM6 staging and China HCC staging (Table 4).

Table 4.

Correlation analysis between methylated status of different TSGs and clinicopathological data of HCC patient

| clinical data | APC | RASSF1A | P16 | MGMT | GSTP1 | RIZ1 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | P‐value | M | P‐value | M | P‐value | M | P‐value | M | P‐value | M | P‐value | ||

| Gender | |||||||||||||

| Male | 51(85%) | 45 | 0.63 | 48 | 1.00 | 32 | 0.62 | 31 | 1.00 | 36 | 0.46 | 28 | 0.12 |

| Female | 9(15%) | 9 | 9 | 7 | 5 | 8 | 8 | ||||||

| Age(year) | 53.5(22–75) | 54.28 ± 10.81 | 0.06 | 52.77 ± 11.29 | 0.08 | 56.00 ± 10.44 | 0.01 | 53.08 ± 11.4 | 0.82 | 51.64 ± 11.89 | 0.06 | 53.04 ± 12.33 | 0.86 |

| AFU(U/L) | 599.4 | 599.58 ± 252.06 | 0.98 | 594.94 ± 250.45 | 0.61 | 600.64 ± 274.87 | 0.96 | 653.32 ± 289.8 | 0.06 | 582.76 ± 251.78 | 0.44 | 620.97 ± 269.93 | 0.46 |

| HbsAg | |||||||||||||

| (+) | 49(81.7%) | 44 | 1.00 | 47 | 0.34 | 32 | 1.00 | 31 | 0.49 | 37 | 0.70 | 32 | 0.17 |

| (–) | 10 | 10 | 7 | 4 | 7 | ||||||||

| HCV‐Ab | |||||||||||||

| (+) | 3(5%) | 3 | 1.00 | 3 | 1.00 | 3 | 0.48 | 2 | 1.00 | 3 | 0.55 | 2 | 1.00 |

| (–) | 45 | 48 | 31 | 29 | 35 | 29 | |||||||

| Liver cirrhosis | |||||||||||||

| (+) | 54(90%) | 49 | 1.00 | 52 | 0.28 | 36 | 0.72 | 31 | 0.43 | 40 | 1.00 | 33 | 0.88 |

| (–) | 6(10%) | 5 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 3 | ||||||

| Child‐Pugh | |||||||||||||

| A | 46(76.7%) | 41 | 1.00 | 44 | 0.56 | 29 | 0.80 | 29 | 0.38 | 33 | 0.87 | 27 | 0.71 |

| B | 14(23.3%) | 13 | 13 | 10 | 7 | 11 | 9 | ||||||

| AFP | |||||||||||||

| <400 µg/L | 35(60.3%) | 31 | 0.64 | 34 | 0.71 | 24 | 0.35 | 21 | 0.79 | 25 | 0.84 | 19 | 0.25 |

| >400 µg/L | 23(39.7%) | 22 | 21 | 13 | 13 | 17 | 16 | ||||||

| r‐GT II | |||||||||||||

| (+) | 23(44.2%) | 20 | 0.44 | 21 | 0.84 | 12 | 0.13 | 13 | 0.69 | 17 | 0.90 | 16 | 0.19 |

| (–) | 29(55.8%) | 28 | 28 | 21 | 18 | 21 | 15 | ||||||

| Tumor number | |||||||||||||

| single | 35(58.3%) | 34 | 1.00 | 33 | 1.00 | 27 | 0.20 | 14 | 0.66 | 30 | 0.20 | 18 | 0.11 |

| multiple | 25(41.7%) | 20 | 24 | 12 | 22 | 14 | 18 | ||||||

| Growth way | |||||||||||||

| Distention | 27(45%) | 23 | 0.49 | 26 | 1.00 | 19 | 0.58 | 14 | 0.24 | 20 | 0.90 | 16 | 0.92 |

| Inflitration | 33(55%) | 31 | 31 | 20 | 22 | 24 | 20 | ||||||

| Gross type | |||||||||||||

| Massive | 18(30%) | 15 | 0.48 | 16 | 0.30 | 10 | 0.08 | 15 | 0.02 | 13 | 1.00 | 9 | 0.42 |

| Nodular | 40(66.7%) | 37 | 39 | 29 | 19 | 29 | 25 | ||||||

| Diffuse | 2(3.3%) | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | ||||||

| Tumor size | |||||||||||||

| <= 5 cm | 20(33.3%) | 17 | 0.77 | 19 | 0.20 | 16 | 0.19 | 8 | 0.08 | 16 | 0.70 | 12 | 0.93 |

| 5–10 cm | 21(35%) | 19 | 21 | 13 | 15 | 15 | 12 | ||||||

| >10 cm | 19(31.7%) | 18 | 17 | 10 | 13 | 13 | 12 | ||||||

| Vascular invasion | |||||||||||||

| (+) | 22(36.7%) | 21 | 0.53 | 21 | 1.00 | 14 | 0.87 | 14 | 0.66 | 16 | 0.94 | 15 | 0.33 |

| (–) | 38(63.3%) | 33 | 36 | 25 | 22 | 28 | 21 | ||||||

| TNM6 stage | |||||||||||||

| I/II | 26(43.3%) | 22 | 0.43 | 24 | 0.81 | 20 | 0.90 | 13 | 0.17 | 21 | 0.26 | 15 | 0.75 |

| III/IV | 34(56.7%) | 32 | 33 | 19 | 23 | 23 | 21 | ||||||

| Chinese stage | |||||||||||||

| I | 11(18.3%) | 9 | 0.63 | 11 | 1.00 | 10 | 0.13 | 5 | 0.44 | 9 | 0.23 | 7 | 0.48 |

| II | 43(71.7%) | 39 | 40 | 25 | 28 | 29 | 24 | ||||||

| III | 6(10%) | 6 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 6 | 5 | ||||||

| Edmondson classification | |||||||||||||

| I/II | 21(35%) | 18 | 0.09 | 18 | 0.06 | 15 | 0.74 | 9 | 0.06 | 14 | 0.71 | 11 | 0.48 |

| II‐III/III | 23(38.3%) | 23 | 23 | 14 | 14 | 18 | 16 | ||||||

| III‐IV/IV | 16(26.7%) | 13 | 16 | 10 | 13 | 12 | 9 | ||||||

r‐GT II: r‐Glutamyl transpeptidase isoenzyme II.

Follow‐up observations. With the exception of 9 patients who died from non‐cancer related deaths, we were able to follow up with 51 patients originally involved in this study. No patient was lost in follow‐up and length of follow‐up ranged from 1 month to 48 months. Thus, of the 51 patients, 37 had a recurrence in which the median time was 6.75 months (range, 1–25 months). Of these 37 recurrences, 19 patients died of the disease. Out of twenty small HCCs (defined as 5 cm or less), 10 recurrences were observed and the median time of recurrence was 14.5 months (range, 7–25 months). All recurrences of small HCC were focal lesions located more than 2 cm from the surgical scar. Of 10 patients, 7 recurrences were located in the ipsilateral lobe of the primary tumor and 3 in a different lobe from the primary tumor.

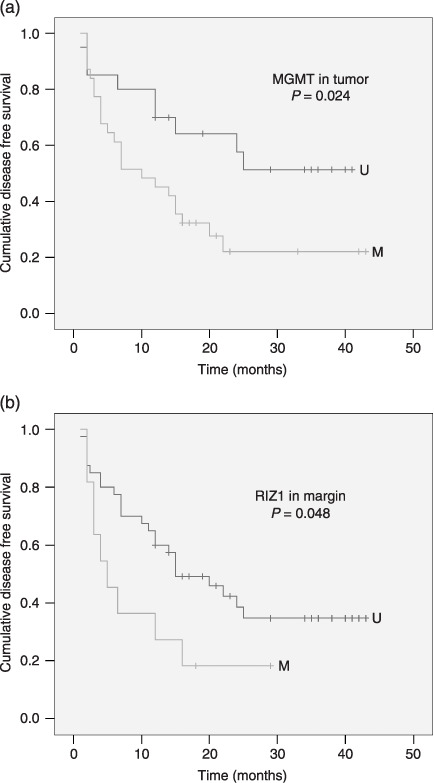

Relationship between survival and methylation status of tumor‐related genes in HCC and SRM. The relationship between overall survival or DFS and the methylation status of tumor‐related genes in HCC and SRM has been explored and we find that the methylation of MGMT in HCC and RIZ1 in SRM were related to the DFS. Patients with MGMT methylation in tumor and RIZ1 methylation in SRM had a shorter DFS (Fig. 6). There were no associations between other survival analyses (Table 5). We have also analyzed prognostic factor of patients with RIZ1 methylation in SRM, which show that out of the 11 patients, 9 recurred with a median recurrence time of 4 months (range, 2–16 months). Of the 9 patients, 2 patients had diffused metastases in liver; 1 patient suffered lung metastases 2 months after surgical resection, the remaining 6 patients had local tumor recurrence.

Figure 6.

Disease free survival of hepatocellular carcinoma patients according to the methylation status of MGMT in tumor (a) and RIZ1 in margin (b). M, methylated status; U, unmethylated status.

Table 5.

Correlation analysis between methylated status of different TSGs and HCC patient's prognosis

| n | Disease free survival | Overall survival | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate (month) | Scope (month) | Log‐Rank | P‐value | Estimate (month) | Scope (month) | log‐rank | P‐value | ||||

| APC | T | M | 46 | 20.642 | 1–43 | 0.003 | 0.956 | 30.285 | 1–44 | 0.557 | 0.456 |

| U | 5 | 14.5 | 6.5–21 | 31.5 | 12–35 | ||||||

| N | M | 29 | 18.872 | 1–41 | 0.399 | 0.528 | 30.833 | 1–44 | 0.029 | 0.866 | |

| U | 22 | 22.529 | 2–43 | 31.312 | 2–43 | ||||||

| RASSF1A | T | M | 49 | 21.115 | 1–43 | 0.623 | 0.43 | 30.977 | 1–44 | 0.056 | 0.814 |

| U | 2 | 11 | 7–15 | 25 | 15–35 | ||||||

| N | M | 35 | 18.489 | 1–38 | 0.24 | 0.624 | 31.447 | 1–44 | 0.005 | 0.946 | |

| U | 16 | 22.581 | 2–43 | 30.263 | 2–43 | ||||||

| P16 | T | M | 33 | 19.161 | 2–43 | 0.396 | 0.529 | 31.363 | 2–44 | 0.028 | 0.866 |

| U | 18 | 22.54 | 1–42 | 29.089 | 1–42 | ||||||

| N | M | 17 | 14.961 | 1–29 | 0.306 | 0.58 | 20.471 | 1–29 | 0.487 | 0.485 | |

| U | 34 | 21.542 | 2–43 | 32.274 | 1–44 | ||||||

| MGMT | T | M | 31 | 16.247 | 2–43 | 5.067 | 0.024 | 31.316 | 3–44 | 0.272 | 0.602 |

| U | 20 | 26.841 | 1–41 | 29.828 | 1–42 | ||||||

| N | M | 23 | 23.261 | 2–43 | 0.906 | 0.341 | 34.677 | 3–43 | 2.372 | 0.124 | |

| U | 28 | 18.012 | 1–41 | 27.629 | 1–44 | ||||||

| GSTP1 | T | M | 36 | 19.323 | 1–42 | 0.224 | 0.636 | 30.994 | 1–44 | 0.012 | 0.914 |

| U | 15 | 21.867 | 2–43 | 29.6 | 3–43 | ||||||

| N | M | 20 | 23.79 | 1–42 | 1.291 | 0.256 | 30.957 | 1–44 | 0.007 | 0.933 | |

| U | 31 | 18.464 | 2–43 | 30.257 | 2–43 | ||||||

| RIZ1 | T | M | 30 | 17.784 | 1–43 | 2.229 | 0.135 | 29.417 | 1–43 | 0.382 | 0.537 |

| U | 21 | 23.856 | 2–40 | 33.63 | 5–44 | ||||||

| N | M | 11 | 10.136 | 2–29 | 3.927 | 0.048 | 29.545 | 2–44 | 0.08 | 0.777 | |

| U | 40 | 22.986 | 1–43 | 30.874 | 1–43 | ||||||

Discussion

Although there have been remarkable improvements in many therapeutic techniques, the long‐term prognosis of HCC patients remains generally poor due to high recurrence rate in the liver remnant. In our previous study,( 13 ) we found aberrant methylation of p16 gene in surgical margins of HCC. It is not clear whether this aberrant methylation of the surgical margin was caused by field cancerization or by an underlying liver disease such as LC and CH, which is very common in Chinese HCC patients. In this study, we have compared the methylation profiles of HCC, SRM and LC. Our results show that methylation of the 8 TSGs were quite a frequent event in HCC and SRM. Specifially, aberrant methylation of APC`RASSF1A`MGMT`p16`GSTP1 and RIZ1 were higher in HCC than in SRM. The tumor relevance of the 6 methylated TSGs fully embodied their important role in HCC tumorigenesis. Consistent with the previous study, we have also found many aberrant methylation alternations in LC tissue. It was well known that LC was a pre‐malignant lesion that may progress to HCC. Our results ultimately supported this notion from epigenetic studies. We showed that more than 90% of HCC patients had CH and/or LC simultaneously. It is conceivable that some molecular changes of SRM such as methylation of APC`RASSF1A`p16`DAPK1 and SOCS‐1, which show no significant different between SRM and LC, actually reflected the alterations of LC and/or CH. Alternatively, the methylation frequencies of MGMT, GSTP1 and RIZ1 were much higher in SRM than in LC. Methylation of the 3 genes in SRM was independent of LC. Consistent with the field cancerization theories,( 3 ) methylation abnormities correlated with HCC but not with background disease in histologically negative margins suggests that field cancerization is present within the liver.

As a progressive process, tumor formation needs cumulative genetic alterations. We have analyzed different epigenetic changes in different HCC tumorigenesis phase. Although DAPK1 and SOCS‐1 had already been shown to be methylation‐specific genes related with tumorigenesis, they don't show any tumor relevance in HCC because of the lack of difference between methylation frequency among HCC, SRM and LC. Our results suggest that aberrant methylation of DAPK1 and SOCS‐1might occur in early phase of hepatocarcinogenesis. It has been suggested by Yoshida et al.( 23 ) that SOCS‐1 contributes to protection against hepatic injury and fibrosis, and may also protect against hepatocarcinogenesis. Similar to DAPK1 and SOCS‐1, methylation frequencies of APC`RASSF1A and p16 did not show any difference in SRM and LC, methylation of these genes should also occur in early tumorigenesis. However, these enhanced methylation frequencies in HCC than in SRM suggest that the methylation of these 3 genes, in particularly, may be a key event for HCC transformation from cirrhotic nodules. MGMT`GSTP1 and RIZ1 showed much more aberrant methylation in HCC than in SRM and little to no methylation in LC. This implicates that methylation of the 3 genes might occur in the late phase of hepatocarcinogenesis when precancerous cells would progress to the true tumor cells. Taken together, difference of methylation frequencies in HCC`SRM and LC clearly show progressive epigenetic alteration in hepatocarcinogenesis.

According to recent explanation from Gabriel,( 3 ) cancerization field results from monoclonal or polyclonal expansion of preneoplastic cells in early tumorigenesis. It is still necessary to elucidate the exact clonal model of field cancerization in liver. In our study, methylation profile was used as clonal markers to evaluate the clonal origin of HCC and SRM. Our results showed that the methylation status of HCC and SRM were accordant in 65% of the cases, but inconsistent for 1–3 genes in 35% of cases. Considering strict accordance of genetic alteration in the essence of monoclone, we presume that the origin of HCC might be complicated and monoclonal and polyclonal model may coexist in field cancerization in liver. Similarly to our analysis, Paradis et al.( 24 ) showed that 54% of macronodules in cirrhosis which was well‐accepted liver preneoplatic lesion was monoclonal and 46% of it was polyclonal. Ochiai et al.( 25 ) also demonstrated that 58.9% of liver regenerative nodules showed a monoclonal model, moreover, the single HCV‐infected liver also showed a monoclonal model, whose mean monoclonal area was about 3.3 mm.

It has been proved that the silence of TSGs induced by promoter hypermethylation play an important role in tumorigenesis. Subsequently, we found some interesting correlations between methylation status of tumor‐related genes in tumor and HCC clinicopathological features. Our data showed that p16 methylation was more frequent in HCC from elder patients. It was also reported by other researchers.( 26 , 27 ) As a tumor‐related gene, p16 methylation reflected the synergetic effect in age and tumorigenesis. The age‐related methylation also functioned in accumulation of tumorigenesis.( 28 ) MGMT is a DNA repair gene that is responsible for the repair of damaged DNA induced by alkylating agents. It has been revealed that the silence of MGMT caused mainly by promoter hypermethylation is closely related with mutation of various oncogenes and TSGs. Our results showed that methylation frequency of MGMT was much higher in massive HCC than in nodular and diffuse HCC, and patients with MGMT methylation in tumor had a shorter DFS. For all these findings, we suppose that MGMT methylation in HCC might be associated with tumor malignancy degree. There are some other studies supporting the supposition. For example, Nakamura et al.( 29 ) demonstrated that frequency of MGMT methylation was significantly lower in primary glioblastomas (WHO grade II) than in secondary glioblastomas (WHO grade IV) that had progressed from low‐grade astrocytomas. Park et al.( 30 ) also suggested that MGMT methylation was significantly associated with lymph node invasion, tumor staging, and DFS in patients with gastric carcinoma.

Intrahepatic recurrence results from either residual intrahepatic metastasis or metachronous, multicentric liver carcinogenesis.( 31 ) However, considering the presence of field cancerization in liver, SFT is also a possible reason.( 32 ) We analyzed the correlation between methylation status of the 6 tumor‐related genes in SRM and the survival data. Patients with RIZ1 methylation in SRM had a shorter DFS. As discussed previously, RIZ1 methylation takes place in the late phase of tumorigenesis. Appearance of RIZ1 methylation in surgical margin, in fact, indicates that transformation of preneoplastic cell was at hand, which would lead to faster recurrence and shorter DFS. Furthermore, we analyzed the type of recurrence in 9 patients with RIZ1 methylation in SRM. Among the 9 patients, local recurrence was observed in 6 patients. Though local recurrence of the 6 patients was possibility caused by minimal residual tumor or intrahepatic metastases, SFT was also a reasonable explanation.

Usually, small HCC recurrence over 1 years is thought to be mainly caused by multicentric tumor.( 33 ) For the presence of field cancerization in liver, the later recurrence should be further divided into SFT and second primary tumor (SPT). Moreover, SFT could be more common in later recurrence. We analyzed recurrence type and distribution of small HCC patients. Our results showed that 70 percent of recurrence tumor in small HCC was located in the neighborhood of primary tumor. For 14.5 months of median time to recurrence, these recurrence tumors unlikely came from minimal residual tumor. Different from SPT's stochastic disribution in the remaining liver, the local recurrence trend should be more related with SFT. Clonal analysis is the exact approaches to distinguish SFT from SPT. But in this study, recurrence sample can not be obtained. Consequently, we can not confirm the exact proportion of recurrence arising from SFT in total HCC recurrence. Further work will be needed to understand the relative importance of SFT in HCC recurrence, and to identify the scope of field cancerization in liver.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Tianjin science committee (grant no. 033801011 and 05YFSZSF02500).

References

- 1. Slaughter DP, Southwick HW, Smejkal W. Field cancerization in oral stratified squamous epithelium; clinical implications of multicentric origin. Cancer 1953; 6: 963–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Braakhuis BJ, Tabor MP, Kummer JA, Leemans CR, Brakenhoff RH. A genetic explanation of Slaughter's concept of field cancerization: evidence and clinical implications. Cancer Res 2003; 63: 1727–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gabriel D, John PJ, Mark AB, Ryan LP. Clinical implications and utility of field cancerization. Cancer Cell Int 2007; 7: 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wong DJ, Paulson TG, Prevo LJ et al . P16 (INK4a) lesions are common, early abnormalities that undergo clonal expansion in Barrett's metaplastic epithelium. Cancer Res 2001; 61: 8284–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chang YL, Wu CT, Lin SC, Hsiao CF, Jou YS, Lee YC. Clonality and prognostic implications of p53 and epidermal growth factor receptor somatic aberrations in multiple primary lung cancers. Clin Cancer Res 2007; 13: 52–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kim SK, Jang HR, Kim JH et al . The epigenetic silencing of LIMS2 in gastric cancer and its inhibitory effect on cell migration. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2006; 349: 1032–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Shen L, Kondo Y, Rosner GL et al . MGMT promoter methylation and field defect in sporadic colorectal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 2005; 97: 1330–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Heaphy CM, Bisoffi M, Fordyce CA et al . Telomere DNA content and allelic imbalance demonstrate field cancerization in histologically normal tissue adjacent to breast tumors. Int J Cancer 2006; 119: 108–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Das PM, Singal R. DNA Methylation and Cancer. J Clin Oncol 2004; 22: 4632–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Esteller M, Corn PG, Baylin SB, Herman JG. A gene hypermethylation profile of human cancer. Cancer Res 2001; 61: 3225–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. International Union Against Cancer (UICC) , Sobin LH, Wittekind C, eds. TNM classification of malignant tumors[M], 6th edn. New York: Wiley‐Liss, 2002: 81–3. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yang BH. Clinical staging research on hepatocellular carcinoma. Modern Digestion Intervention 2002; 7: 5–7. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Yang B, Gao YT, Du Z, Zhao L, Song WQ. Methylation‐based molecular margin analysis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2005; 338: 1353–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Herman JG, Graff JR, Myöhänen S, Nelkin BD, Baylin SB, Methylation‐specific PCR. A novel PCR assay for methylation status of CpG islands. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1996; 93: 9821–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Esteller M, Corn PG, Urena JM, Gabrielson E, Baylin SB, Herman JG. Inactivation of glutathione s‐transferase P1 gene by promoter hypermethylation in human neoplasia. Cancer Res 1998; 58: 4515–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lo KW, Kwong J, Hui AB et al . High frequency of promoter hypermethylation of RASSF1A in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer Res 2001; 61: 3877–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tsuchiya T, Tamura G, Sato K et al . Distinct methylation patterns of two APC gene promoters in normal and cancerous gastric epithelia. Oncogene 2000; 19: 3642–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Katzenellenbogen RA, Baylin SB, Herman JG. Hypermethylation of the DAP‐kinase CpG island is a common alteration in B‐cell malignancies. Blood 1999; 93: 4347–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Yoshikawa H, Matsubara K, Qian GS et al . SOCS‐1,a negative regulator of the JAK/STAT pathway, is silenced by methylation in human hepatocellular carcinoma and shows growth‐suppression activity. Nat Genet 2001; 28: 29–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Du Y, Carling T, Fang W, Piao Z, Sheu JC, Huang S. Hypermethylation in human cancers of the RIZ1 tumor suppressor gene, a member of a histone/protein methyltransferase superfamily. Cancer Res 2001; 61: 8094–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gonzalez‐Gomez P, Bello MJ, Lomas J et al . Aberrant methylation of multiple genes in neuroblastic tumours: relationship with MYCN amplification and allelic status at 1p. Eur J Cancer 2003; 39: 1478–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nomoto S, Kinoshita T, Kato K et al . Hypermethylation of multiple genes as clonal markers in multicentric hepatocellular carcinoma. Br J Cancer 2007; 97: 1260–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Yoshida T, Ogata H, Kamio M et al . SOCS1 is a suppressor of liver fibrosis and hepatitis‐induced carcinogenesis. J Exp Med 2004; 199: 1701–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Paradis V, Laurendeau I, Vidaud M, Bedossa P. Clonal analysis of macronodules in cirrhosis. Hepatology 1998; 28: 953–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ochiai T, Urata Y, Yamano T, Yamagishi H, Ashihara T. Clonal expansion in evolution of chronic hepatitis to hepatocellular carcinoma as seen at an X‐chromosome locus. Hepatology 2000; 31: 615–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Katoh H, Shibata T, Kokubu A et al . Epigenetic instability and chromosomal instability in hepatocellular carcinoma. Am J Pathol 2006; 168: 1375–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Peng CY, Chen TC, Hung SP et al . Genetic alterations of INK4alpha/ARF locus and p53 in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Anticancer Res 2002; 22: 1265–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ahuja N, Li Q, Mohan AL, Baylin SB, Issa JP. Aging and DNA methylation in colorectal mucosa and cancer. Cancer Res 1998; 58: 5489–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Nakamura M, Watanabe T, Yonekawa Y, Kleihues P, Ohgaki H. Promoter methylation of the DNA repair gent MGMT in astrocytomas is frequently associated with G : C – A : T mutations of the TP53 tumor suppressor gene. Carcinogenesis 2001; 22: 1715–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Park TJ, Han SU, Cho YK, Paik WK, Kim YB, Lim IK. Methylation of O (6)‐methylguanine‐DNA methyltransferase gene is associated significantly with K‐ras mutation, lymph node invasion, tumor staging, and disease free survival in patients with gastric carcinoma. Cancer 2001; 92: 2760–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sakon M, Umeshita K, Nagano H et al . Clinical significance of hepatic resection in hepatocellular carcinoma: analysis by disease‐free survival curves. Arch Surg 2000; 135: 1456–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Braakhuis BJM, Brakenhoff RH, Leemans CR. Second Field Tumors: a new opportunity for cancer prevention? Oncologist 2005; 10: 493–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Poon RT, Fan ST, Ng IO, Lo CM, Liu CL, Wong J. Different risk factors and prognosis for early and late intrahepatic recurrence after resection of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer 2000; 89: 500–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]