Abstract

Oncogenic mutations of the KRAS gene have emerged as a common mechanism of resistance against epidermal growth factor receptor (EGF‐R)‐directed tumor therapy. Mutated KRAS leads to ligand‐independent activation of signaling pathways downstream of EGF‐R. Thereby, direct effector mechanisms of EGF‐R antibodies, such as blockade of ligand binding and inhibition of signaling, are bypassed. Thus, a humanized variant of the approved EGF‐R antibody Cetuximab inhibited growth of wild‐type KRAS‐expressing A431 cells, but did not inhibit KRAS‐mutated A549 tumor cells. We then investigated whether killing of tumor cells harboring mutated KRAS can be improved by enhancing antibody‐dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC). Protein‐ and glyco‐engineering of antibodies’ Fc region are established technologies to enhance ADCC by increasing antibodies’ affinity to activating Fcγ receptors. Thus, EGF‐R antibody variants with increased affinity for the natural killer (NK) cell‐expressed FcγRIIIa (CD16) were generated and analyzed. These variants triggered significantly enhanced mononuclear cell (MNC)‐mediated killing of KRAS‐mutated tumor cells compared to wild‐type antibodies. Additionally, cells transfected with mutated KRAS were killed as effectively by ADCC as vector‐transfected control cells. Together, these data demonstrate that KRAS mutations are not sufficient to render tumor cells resistant to ADCC. Consequently Fc‐engineered EGF‐R antibodies may prove effective against KRAS‐mutated tumors, which are not susceptible to signaling inhibition by EGF‐R antibodies.

(Cancer Sci 2010; 101: 1080–1088)

After approximately 30 years of translational research, the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGF‐R), ErbB1, has emerged as a validated target antigen for molecular therapies.( 1 ) Today, both EGF‐R‐directed tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI) and EGF‐R antibodies have obtained approval for tumor therapy.( 2 , 3 ) As expected from clinical experience with TKI against other target antigens,( 4 ) mutations in the EGF‐R kinase domain critically affect sensitivity and resistance against EGF‐R directed TKI.( 5 ) These EGF‐R mutations proved less relevant for tumor cell killing by EGF‐R antibodies in vitro ( 6 ) and in animal models,( 7 ) and early clinical data support these observations.( 8 ) On the other hand, resistance against EGF‐R antibodies in colorectal cancer (CRC) patients has been associated with activating mutations of KRAS ( 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 ) and other mediators of downstream signaling such as v‐raf murine sarcoma viral oncogene homolog B1 (B‐RAF),( 13 ) phosphoinositide‐3‐kinase (PI3K), phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN), and others.( 14 ) This clinical resistance of KRAS‐mutated CRC led to the development of guidelines that recommend to limit the application of EGF‐R‐directed antibodies to CRC patients bearing wild‐type KRAS tumors.( 15 )

KRAS belongs to the family of RAS proto‐oncogenes that activate intracellular signaling downstream of receptor kinases.( 16 ) Thereby, oncogenic point mutations in the KRAS gene promote cellular growth and apoptosis resistance – leading to more aggressive tumor phenotypes with increased resistance to chemo‐ and radiotherapy. Oncogenic RAS proteins display impaired intrinsic GTPase activity preventing their inactivation by GTPase activating proteins (GAPs).( 17 ) This makes the development of small molecule inhibitors inherently difficult,( 18 ) although promising approaches are emerging.( 19 ) Furthermore, inhibitors of RAS processing, such as farnesyltransferase‐inhibitors, often do not inhibit KRAS4b – the most common RAS isoform in solid tumors.( 20 ) Therefore, substances blocking molecules downstream of KRAS, such as PI3K and MEK are actively investigated,( 21 ) but other strategies to overcome RAS‐mediated resistance to tumor therapy are required.

EGF‐R antibodies can recruit a broad panel of tumor cell killing mechanisms.( 22 ) These mechanisms may be divided into those mediated by the F(ab′) region – called direct mechanisms – and indirect mechanisms that are triggered by antibodies’ constant Fc region.( 23 ) For EGF‐R antibodies, direct mechanisms such as blockade of ligand binding, inhibition of signaling, and receptor down‐regulation are considered to be particularly important.( 2 , 3 ) However, in vitro EGF‐R antibodies can also effectively recruit indirect mechanisms such as complement‐dependent cytotoxicity (CDC)( 24 ) and antibody‐dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC).( 25 ) In mice, the efficacy of ErbB2 (HER‐2/neu)‐directed antibodies has been demonstrated to critically depend on the expression of activating Fcγ receptors,( 26 ) and – against other target antigens – on antibodies’ relative binding affinities to activation compared to inhibitory Fc receptors (A:I ratio).( 27 ) Importantly, ADCC operated at lower antibody concentrations compared to direct effector mechanisms.( 28 ) The contribution of ADCC to ErbB antibodies’ efficacy in patients is supported by studies demonstrating associations between therapeutic efficacy and the expression of certain Fcγ receptor allotypes,( 29 , 30 , 31 ) which display enhanced antibody binding and increased ADCC activity compared to their less active alloforms.( 32 , 33 ) Together, these observations stimulate research into antibodies with enhanced affinity to activating Fcγ receptors.( 34 , 35 )

So far, two approaches of engineering antibodies’ Fc regions have proved to be particularly powerful for enhancing Fcγ receptor binding and for improving Fcγ receptor‐mediated effector functions: reducing the amount of fucose in the CH2 attached glycosylation( 36 , 37 ) (glyco‐engineering), and site‐directed mutagenesis of amino acids in the hinge or CH2 regions of antibodies (protein‐engineering).( 38 ) Here, we demonstrate that EGF‐R antibodies of IgG1 isotype can kill KRAS‐mutated tumor cells via ADCC. Tumor cell killing was significantly enhanced when Fc‐engineered EGF‐R antibodies were compared to their wild‐type counterpart. These results support approaches to enhance the ADCC activity of EGF‐R antibodies, particularly in patients with KRAS‐mutated tumors, who otherwise have a low probability of responding to currently available EGF‐R‐directed therapies.( 15 )

Material and Methods

Study population and consent.

Experiments reported here were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Christian‐Albrechts‐University, Kiel, Germany, in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Blood donors were randomly selected from healthy volunteers, who gave written informed consent before analyses. Distribution of FcγRIIIa genotypes among analyzed individuals was 25% (V/V), 33.3% (F/F), and 41.7% (V/F).

Culture of human EGF‐R‐expressing cancer cell lines.

Epidermoid carcinoma cell line A431, non‐small cell‐lung cancer (NSCLC) cell line H2030 (both ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA), and colorectal carcinoma (CRC) cell line SW‐480 (kindly provided by Genmab, Utrecht, The Netherlands) were kept in RPMI‐1640‐Glutamax‐I medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). NSCLC cells A549 and CRC cells HCT‐116 (both ATCC) were kept in DMEM (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). All media were supplemented with 10% (v/v) heat‐inactivated fetal calf serum, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin. The growth medium for the H2030 cell line was additionally supplemented with 2 mm l‐glutamine, 10 mm HEPES, 1 mm sodium pyruvate, 4.5 g/L glucose, and 1.5 g/L sodium bicarbonate (all Sigma‐Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA).

Construction of a KRAS expression vector and stable transfection of A431 cells.

Full‐length wild‐type KRAS4b was amplified by PCR from cDNA of H1975 cells. The G12V mutation was inserted by PCR, and the resulting PCR product was cloned between the HindIII and NotI sites of the expression vector pSec (Invitrogen). An N‐terminal myc‐tag was added into the NheI and HindIII restriction sites with the following oligonucleotides 5′‐CTAGCATGGAGCAGAAGCTGATCAGCGAG‐GAGGACCTGATGACTGAATATA‐3′ and 5′‐AGCTTATAT‐TCAGTCACAGGTCCTCCTCGCTGATCAGCTTCTGCTCC‐ATG‐3′. To control vector expression, an internal ribosomal entry site (IRES) and green fluorescence protein (GFP) were subcloned from the vector pIRES‐ZsGreen (Clonetech, St‐Germain‐en‐Laye, France) into the pSec KRAS4bG12V vector or into the pSec vector – serving as the control vector. The resulting vectors were transfected into A431 with lipofectamine2000 (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Transfectants were sorted for GFP expression with a FACSAria cytofluorometer (BD Biosciences, Erembodegem, Belgium).

Immunoprecipitation.

Cells were seeded in 10‐cm dishes at 5 × 106 cells/dish and grown overnight. The next day, cells were washed with ice‐cold PBS and pelleted by centrifugation. Cells were lysed according to the manufacturer’s instructions using native lysis buffer (NLB; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA). Five‐hundred μg of native protein were incubated with 10 μL of Raf‐1 RBD agarose beads (Millipore, Temecula, CA, USA) for 1 h at 4°C to precipitate activated RASGTP. Precipitates were washed three times with NLB, denatured by boiling in 40 μL 2 × Laemmli buffer, and separated by SDS‐PAGE. After transfer onto PVDF membranes, samples were probed for precipitated RAS using rabbit anti‐RAS or rabbit anti‐myc antibody (both Cell Signaling Technology). Whole protein extracts were separated by SDS‐PAGE and immunoblotted against total RAS to control equal protein loading.

Determination of viable cell mass (MTS assay).

The CellTiter 96 non‐radioactive cell proliferation assay was performed with A431 and A549 cells according to manufacturer’s instructions (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). Cells were seeded at 5000 cells/well in 96‐well flat‐bottom tissue culture plates (Becton Dickinson, Meylan Cedex, France) and grown in complete growth medium in a final volume of 100 μL. Cells were treated for 72 h with antibodies before the absorbance of formazan was measured at 490 nm on a Sunrise ELISA reader (Tecan Group, Männedorf, Switzerland).

Isolation of human effector cells.

Human effector cells such as peripheral mononuclear cells (MNCs) or polymorphonuclear cells (PMNs) were isolated from peripheral blood from healthy volunteers as previously described.( 39 )

Antibody‐dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) assays.

ADCC assays were performed as described in( 39 ) but without stimulation of PMNs with granulocyte‐macrophage colony‐stimulating factor. For whole blood assays, unseparated human blood was freshly drawn from healthy volunteers, anticoagulated with 500 U/mL heparin and directly used as effector source in ADCC assays. Percentage of cellular cytotoxicity was calculated using the following formula: % specific lysis = (experimental cpm − basal cpm)/(maximal cpm – basal cpm) × 100. For calculation of relative tumor cell lysis (%), specific lysis triggered by 10 μg/mL of S239D/I332E was equated with 100% lysis and set into relation with all other lysis rates.

EGF‐R antibodies.

The approved EGF‐R antibody Cetuximab (chimeric IgG1; Erbitux) was bought from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). A humanized IgG1 version of Cetuximab was generated, and produced in HEK293E cells (wildtype).( 40 ) Protein‐ or glyco‐engineered antibody variants of this wild‐type antibody were constructed, expressed, and purified as described,( 38 , 41 ) except that expression was carried out in HEK293E cells using the pTT5 vector system (NRC‐BRI, Montreal, Quebec, Canada).( 38 ) An human IgG1 antibody against keyhole limpet hemocyanin (HuMab‐KLH), which was kindly provided by Genmab, served as irrelevant control antibody.

Determination of Fc receptor binding affinities.

Human Fc receptors with 6 × His tags were expressed in HEK293T cells and purified using nickel affinity chromatography. Binding affinities of EGF‐R antibodies to FcγRs were determined by Biacore as described previously.( 41 )

Flow cytometric analyses.

For indirect immunofluorescence, cells were incubated with antibodies at various concentrations in PBS supplemented with 0.5% bovine serum albumin (Sigma‐Aldrich) and 0.1% sodium‐azide (PBS buffer) for 30 min on ice. After washing, cells were stained with FITC‐conjugated F(ab′)2 fragments rabbit antihuman IgG (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark), respectively. Quantitative surface EGF‐R expression was determined using murine EGF‐R and control antibodies, and the QIFIKIT (Dako), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Immunofluorescence was analyzed on a flow cytometer (Epics Profile; Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA, USA).

Data processing and statistical analyses.

Data are displayed graphically and were statistically analyzed using GraphPad Prism 4.0. Curves were fitted using a nonlinear regression model with a sigmoidal dose response (variable slope). Statistical significance was determined by the Student’s t‐test (paired, two‐tailed) and the respective results are displayed as mean ± SEM. P‐values were calculated and null hypothesis was rejected when P ≤ 0.05.

Results

Characterization of used cell lines.

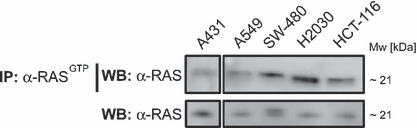

Cell lines were selected according to their KRAS status from the Cancer Genome Project online database at the Sanger Institute and from literature.( 42 ) While the A431 cell line harbors wild‐type KRAS,( 43 ) A549, H2030, HCT‐116, and SW‐480 cells carry activating mutations of the KRAS gene. As measured by using the QIFIKIT, all of these cell lines differ in the expression of EGF‐R molecules per cell, with A431 cells showing the highest and HCT‐116 cells the lowest EGF‐R expression. The characteristics of the aforementioned cell lines are summarized in Table 1. To analyze whether point mutations of the KRAS gene, described for A549, H2030, HCT‐116, and SW‐480 cells, influence the activation status of RAS, all five cell lines were assayed by immunoprecipitation against activated RASGTP. As expected, enhanced activation of RAS was detected for the cell lines harboring oncogenic KRAS (A549, H2030, HCT‐116, and SW480 cells) when compared to A431 cells (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Cell lines used in this study

| Cell line | Origin | EGF‐R molecules/cell† | EGF‐R | KRAS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A431 | Epidermoid carcinoma | 2 056 108 ± 399 361 | Wild‐type, amplified | Wild‐type |

| A549 | NSCLC | 255 890 ± 21 063 | Wild‐type | G12Shomozygous |

| H2030‡ | NSCLC | 166 400 ± 31 407 | Wild‐type | G12Chomozygous |

| HCT‐116§ | CRC | 45 062 ± 5638 | Wild‐type | G13Dheterozygous |

| SW‐480 | CRC | 48 059 ± 6478 | Wild‐type | G12Vhomozygous |

†Determined by indirect immunofluorescence using the QIFIKIT; ‡additional homozygous p53 mutation (G262V); §additional heterozygous PIK3CA mutation (H1047R). CRC, colorectal cancer; EGF‐R, epidermal growth factor receptor; NSCLC, non‐small‐cell lung cancer. Source: Cancer Genome Project online database at Sanger Institute (http://www.sanger.ac.uk) and reference.( 42 )

Figure 1.

Oncogenic mutations of the KRAS gene are accompanied by constitutive activation of KRAS. Cells were grown overnight in 10‐cm dishes at 5 × 106 cells/dish. The next day, immunoprecipitation against activated RASGTP was performed using Raf‐1 RBD agarose beads and 500 μg native protein extracts. Precipitated, activated RAS was separated by SDS‐PAGE and immunoblotted against RAS. The amount of total RAS protein in the analyzed cell lines was controlled by separation of 15 μg of whole protein extracts per sample by SDS‐PAGE and immunoblotting against RAS.

Humanized EGF‐R antibody did not inhibit proliferation, but mediated ADCC against KRAS‐mutated cells.

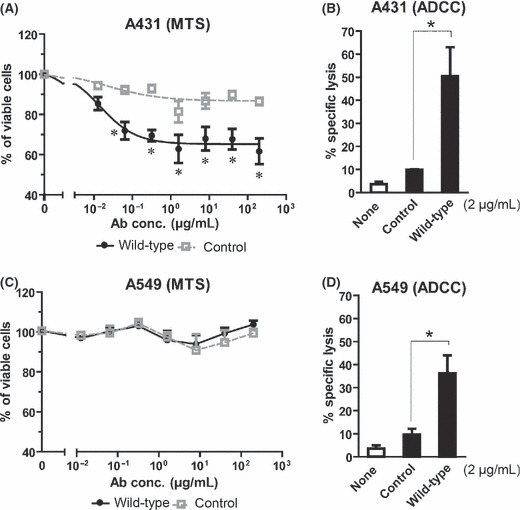

In order to investigate effector mechanisms of humanized Cetuximab (wild‐type) against cell lines carrying wild‐type or oncogenic KRAS, growth inhibition and ADCC assays were performed with A431 and A549 cells, respectively. While the EGF‐R antibody induced significant growth inhibition of A431 cells when compared to the non‐binding control antibody, it failed to affect A549 cells. Vital cell masses at the highest antibody concentration (200 μg/mL) of wild‐type antibody ranged from 61.6% ± 6.4% for A431 cells to 103.7% ± 1.9% for A549 cells after 72 h of incubation, respectively (Fig. 2A,C). In a next set of experiments, ADCC mediated by MNC effector cells was analyzed. Interestingly, wild‐type antibody induced significant ADCC activity (P ≤ 0.05) against A431 cells (50.3% ± 12.6%) and A549 cells (36.2% ± 7.9%) when compared to control antibody (Fig. 2B,D).

Figure 2.

Humanized Cetuximab did not induce growth inhibition, but triggered antibody‐dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) against the KRAS‐mutated tumor cell line A549. Wild‐type KRAS‐expressing A431 cells and KRAS‐mutated A549 cells served as targets in MTS growth inhibition and 51chromium‐release ADCC assays. (A,C) Cells were incubated in the presence or absence of wild‐type or control antibodies (0.013 to 200 μg/mL). After 72 h of incubation, cells were analyzed by MTS assay. (B,D) For ADCC assays, cells were incubated with human mononuclear cells (MNCs) at an E:T ratio of 80:1 in the presence or absence of wild‐type or isotype control antibodies (final concentration 2 μg/mL). After 3 h, lysis of tumor cells was determined by measurement of 51Cr release. Data are presented as mean ± SEM of multiple independent experiments (MTS A431 n = 9; MTS A549 n = 3; ADCC A431/A549 n = 5) with different donors. Asterisks (*) indicate significant lysis or growth inhibition (P < 0.05).

Construction and characterization of Fc‐engineered EGF‐R antibody variants.

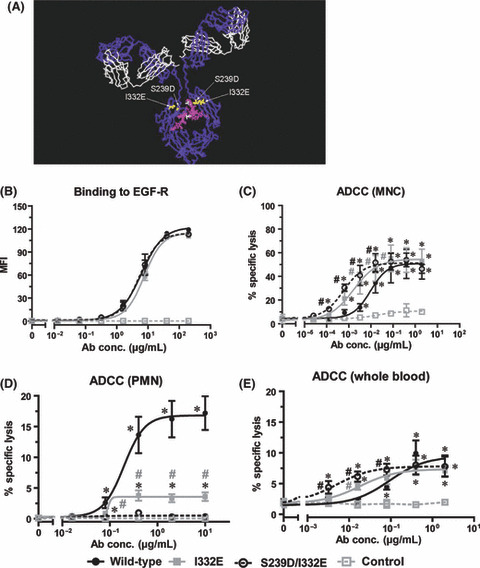

As the KRAS‐mutated A549 cell line was susceptible to ADCC, it was investigated whether Fc engineering may improve ADCC against EGF‐R‐expressing tumor cells. Binding of the wild‐type antibody to FcγRIII (CD16) was enhanced by protein engineering of its CH2 domain (I332E and S239D/I332E) as described previously.( 38 , 41 ) Furthermore, the wild‐type antibody was expressed in Lec‐13 cells to generate a non‐fucosylated variant. Binding to activating human Fcγ receptors (FcγRIIa and FcγRIIIa) and their alloforms (FcγRIIa‐131H/R and FcγRIIIa‐158V/F) was analyzed by Biacore. Results are summarized in Table 2, and were as expected from previous studies. Binding of the variants to human FcγRI and FcγRIIb has been described in a recent study.( 41 ) SDS‐PAGE and immunoblotting experiments with HRP‐conjugated antihuman‐IgG antibodies and a HRP‐conjugated Aleuria Aurantia lectin specific for fucose linked (α‐1,6) to N‐acetylglucosamine or (α‐1,3) to N‐acetyllactosamine‐related structures revealed that the Lec‐13 expressed antibody did not contain detectable levels of fucose (Fig. S1). In Figure 3(A) a model structure of a human IgG1 antibody comprising protein‐engineered variants is represented.

Table 2.

Binding affinities of EGF‐R antibody variants to human Fcγ receptors

| Antibody variant | Kd (nm) (fold increase to IgG1wt) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FcγRIIa H131 | FcγRIIa R131 | FcγRIIIa V158 | FcγRIIIa F158 | |

| Wild‐type | 640 (1.0) | 870 (1.0) | 250 (1.0) | 920 (1.0) |

| Afucosylated IgG1 | 680 (0.94) | 610 (1.4) | 14 (18) | 84 (11) |

| I332E | 400 (1.6) | 530 (1.6) | 34 (7.4) | 200 (4.6) |

| S239D/I332E | 210 (3.0) | 160 (5.4) | 5.0 (50) | 24 (38) |

EGF‐R, epidermal growth factor receptor.

Figure 3.

Fc engineering enhanced mononuclear cell (MNC)‐mediated but decreased polymorphonuclear cell (PMN)‐mediated antibody‐dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC). (A) Model structure of human IgG1( 42 ) highlighting the amino acid substitutions and the fucose residue in the antibodies’ heavy chains. Gray = heavy chain; white = light chain. The picture was generated using Accelrys DS visualizer software. To characterize the antibody variants, indirect immunofluorescence and ADCC assays with wild‐type KRAS and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGF‐R)‐high‐expressing A431 cells were performed. (B) For indirect immunofluorescence A431 cells were incubated with increasing concentrations (0.013 to 200 μg/mL) of wild‐type, Fc variant (I332E or S239D/I332E), or control antibodies, and stained with F(ab′)2 fragments of polyclonal FITC‐conjugated rabbit antihuman IgG. Each data point represents the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of respective antibody at the indicated concentration. To analyze the cytotoxic activity of Fc‐engineered antibodies, ADCC assays (C–E) were performed. Target cells were opsonized with increasing concentrations of wild‐type, Fc variant (I332E or S239D/I332E), or control antibodies, respectively. Isolated MNC (C) or PMN (D) at an E:T ratio of 80:1 or whole blood (E) served as effector cells in 51Cr release assays. Data are presented as mean ± SEM of at least three independent experiments. *P < 0.05 control vs wild‐type antibody; #P < 0.05 variants vs wild‐type antibody.

Wild‐type and protein‐engineered antibody variants were then analyzed with regard to their F(ab′)‐mediated effector functions. As expected, all three antibodies demonstrated very similar binding characteristics to EGF‐R‐expressing A431 cells, resulting in EC50 values ranging from 5.2 μg/mL (S239D/I332E; 95% confidence interval [CI], 4.1–6.5 μg/mL) to 6.9 μg/mL (I332E; 95% CI, 5.4–8.9 μg/mL) (Fig. 3B) – indicating that protein‐engineering did not affect antibody affinity to its antigen. EGF‐R affinity of the antibodies was also indistinguishable when tested by Biacore (data not shown). To assess Fc‐mediated effector functions, ADCC assays were performed with A431 target cells, and isolated effector cell populations or human whole blood samples. With isolated MNC, I332E and S239D/I332E variants demonstrated significantly increased killing at lower EC50 concentrations (0.0016 μg/mL [95% CI, 0.00039–0.0069] and 0.0006 μg/mL [95% CI, 0.00023–0.0015], respectively) compared to wild‐type antibody (0.0095 μg/mL [95% CI, 0.0029–0.03]) (Fig. 3C). However, when ADCC assays were performed with isolated PMN effector cells, ADCC was less effective with the I332E variant compared to wild‐type antibody, and abolished with the S239D/I332E variant (Fig. 3D). To analyze the cytolytic capacity of variant antibodies under more physiological conditions, unseparated human whole blood samples were assayed in ADCC experiments. As shown in Figure 3(E), differences in EC50 values between variant and wild‐type antibodies were comparable to MNC‐mediated ADCC, but at lower overall killing. In conclusion, data presented in Figure 3 revealed MNC to be the main effector cell population in whole blood samples mediating ADCC by wild‐type and variant antibodies.

Fc‐engineered EGF‐R antibody variants did not affect direct effector mechanisms.

Antibody variants were compared with regard to their capacity to inhibit growth of A431 and A549 cells. In contrast to A431 cells where vital cell masses of 59.8% ± 6.6% with S239D/I332E or 64.3% ± 5.7% with I332E variants and 61.7% ± 6.4% with wild‐type at the highest antibody concentration (200 μg/mL) were detected (Fig. S2A), no growth inhibition was induced in A549 cells (Fig. S2B). These results were significantly (P < 0.05) different from that received in experiments with a control antibody, where the detected vital cell mass was 86.5% ± 1.9% at highest concentration. Thus, for both antibody variants, no alterations concerning their capacity to directly inhibit cell proliferation could be detected – demonstrating F(ab′)‐mediated effector functions not to be affected by Fc protein‐engineering.

Fc engineering enhanced ADCC against KRAS‐mutated tumor cells.

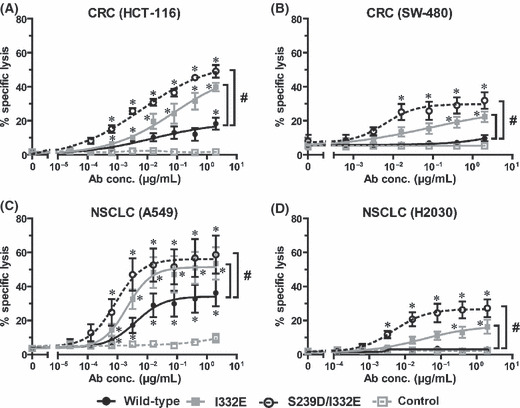

Furthermore, wild‐type antibody and its protein‐engineered variants were compared in ADCC assays against the KRAS‐mutated tumor cell lines HCT‐116, SW‐480 (Fig. 4A,B), A549, and H2030 (Fig. 4C,D). Significantly enhanced killing (up to 2.5‐fold) of all cell lines was observed when protein‐engineered antibody variants were compared with the respective wild‐type EGF‐R antibody. The S239D/I332E variant triggered killing, ranging from 27.2% ± 5.3% of H2030 cells to 58.7% ± 11.2% of A549 cells, while the I332E variant showed killing from 16.4% ± 4.1% of H2030 cells to 53.6% ± 9.6% of A549 cells at highest antibody concentration (2 μg/mL). ADCC against HCT‐116 and SW‐480 cells at saturating antibody concentration (2 μg/mL) was slightly lower with the S239D/I332E variant (49.1% ± 3.7% and 31.9% ± 4.9%), respectively. With the I332E variant, lysis rates of 39.8% ± 2.5% and 22.4% ± 3.1% were observed with the CRC cell lines. Notably, the S239D/I332E variant was significantly (P ≤ 0.05) more effective than the single‐engineered counterpart at antibody concentrations ranging from 0.00013 μg/mL to 0.016 μg/mL against HCT‐116 cells (Fig. 4A), and from 0.0032 μg/mL to 2 μg/mL against H2030 cells (Fig. 4D; symbols for significance not shown), while other differences between the variants were not significant. Furthermore, ADCC with the wild‐type antibody was not significant against SW‐480 (9.7% ± 1.9%) as well as H2030 cells (3.2% ± 1%, both at concentrations of 2 μg/mL), while both engineered antibodies triggered significant lysis (Fig. 4B,D).

Figure 4.

Fc protein engineering improved killing of KRAS‐mutated tumor cells. To analyze the cytotoxic activity of Fc‐engineered antibody variants, wild‐type, Fc variants (I332E or S239D/I332E), or control antibodies were incubated at increasing concentrations with KRAS‐mutated colorectal cancer (CRC) cell lines HCT‐116 (A) or SW‐480 (B), or the non‐small‐cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cell lines A549 (C) and H2030 (D), respectively. Isolated mononuclear cells (MNCs) served as effector cells at an E:T ratio of 80:1. Data are presented as mean ± SEM of at least four independent experiments with different donors. *P < 0.05 control vs wild‐type antibody; #P < 0.05 variants vs wild‐type antibody.

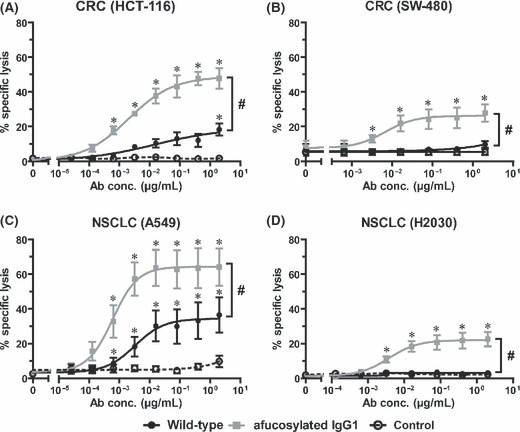

To assess whether glyco‐engineering also results in enhanced ADCC against KRAS‐mutated tumor cells, similar experiments were performed comparing a non‐fucosylated and the wild‐type antibody (Fig. 5). Interestingly, all four cell lines proved susceptible to ADCC by the glyco‐engineered EGF‐R antibody. The wild‐type antibody demonstrated significantly lower ADCC activity with all cell lines tested. Moreover, MNC mediated ADCC against KRAS‐mutated tumor cells with both protein‐ and glycoengineered variants is not only distinguished by lower EC50 concentrations compared to wild‐type, but also by remarkably increased killing at saturating antibody concentrations.

Figure 5.

Fc glyco‐engineering enhanced antibody‐dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) against KRAS‐mutated tumor cells. The impact of the afucosylated antibody Fc portion on ADCC against KRAS‐mutated tumor cells was analyzed in comparison to wild‐type antibody. Afucosylated, wild‐type, or control antibodies were incubated at increasing concentrations with colorectal cancer (CRC) (A,B) or non‐small‐cell lung cancer (NSCLC) (C,D) cell lines and mononuclear cell (MNC) effector cells at an E:T ratio of 80:1. Data are presented as mean ± SEM of triplicate wells from at least four independent experiments with different donors. *P < 0.05 control vs wild‐type antibody; #P < 0.05 variants vs wild‐type antibody.

In conclusion, data presented in 5, 6 demonstrated that KRAS‐mutated cells were susceptible to ADCC, and that ADCC activity could be enhanced by protein‐ or glyco‐engineering of EGF‐R antibodies.

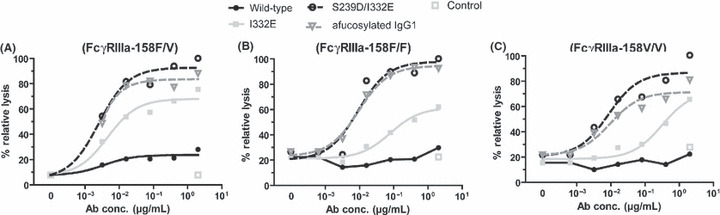

Figure 6.

Fc‐engineering improved antibody‐dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) activity independently of the FcγRIIIa‐158F/V genotype. For ADCC experiments, SW‐480 cells were incubated with increasing concentrations of wild‐type, variant, or control antibodies and mononuclear cell (MNC) effector cells from healthy donors (E:T ratio 80:1) that were genotyped for the FcγRIIIa‐158F/V polymorphism. After 3 h of incubation, 51Cr‐release was determined, and relative tumor cell lysis was calculated as described in Materials and Methods. Graphs represent means of triplicates from experiments with MNC from FcγRIIIa‐158F/V (A), ‐158F/F (B), or ‐158V/V (C) genotyped donors, respectively. Legends are as shown.

Fc engineering improved ADCC activity independently of the FcγRIIIa allotype.

To analyze whether ADCC activity triggered by Fc‐engineered EGF‐R antibodies was influenced by different FcγRIIIa‐158F/V genotypes, ADCC experiments were performed with KRAS‐mutated SW‐480 cells and MNC effector cells from healthy donors, genotyped for the FcγRIIIa‐158F/V polymorphism. Irrespective of the individual FcγRIIIa allotype, stronger ADCC activity was observed for protein‐ and glyco‐engineered antibodies compared to their wild‐type counterpart (Fig. 6).

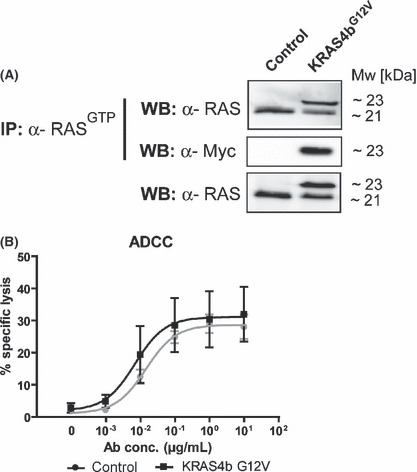

Overexpression of oncogenic KRAS did not affect MNC‐mediated ADCC.

Previous experiments demonstrated that KRAS‐mutated tumor cell lines were susceptible to ADCC by Fc‐engineered EGF‐R antibodies, but did not address the question whether KRAS mutations directly affected ADCC. To investigate this interesting issue, A431 cells harboring wild‐type KRAS were stably transfected with oncogenic KRAS4b G12V or a control vector (see Materials and Methods). Tumor cells were assayed by immunoprecipitation against activated RASGTP and western blot experiments. Results from these experiments demonstrated that both transfectants stably expressed GFP (data not shown) and basal levels of active, wild‐type KRAS, whereas only in KRAS4b G12V ‐transfected cells a second protein band could be detected – representing active myc‐tagged KRAS4b G12V (Fig. 7A).

Figure 7.

Oncogenic KRAS did not affect mononuclear cell (MNC)‐mediated antibody‐dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) activity. A431 cells were stably transfected with oncogenic myc‐tagged KRAS4b G12V or control vector and stable vector expression was controlled by sorting for GFP expression. (A) Functional analysis of transfected KRAS4b G12V was performed by immunoprecipitation against activated RASGTP using Raf‐1 RBD agarose beads and 500 μg native protein extracts. Precipitated, activated RAS was separated by SDS‐PAGE and immunoblotted against RAS and the myc‐tag. The amount of total RAS protein was controlled by separation of 15 μg of whole protein extracts per sample by SDS‐PAGE and immunoblotting against RAS. To analyze whether oncogenic KRAS‐transfected A431 cells differed in susceptibility to ADCC by epidermal growth factor receptor (EGF‐R) antibodies, both KRAS4b G12V or control vector‐transfected cells were incubated with increasing antibody concentrations. Isolated MNC served as effector cells at an E:T ratio of 80:1. Data are presented as mean ± SEM of four independent experiments with different donors (B).

Next, ADCC experiments with MNC effector cells were performed with A431 KRAS4b G12V cells and A431 cells transfected with the control vector. As presented in Figure 7(B), no differences in Cetuximab‐triggered cytotoxicity were observed between both transfectants – demonstrating that oncogenic KRAS did not affect MNC‐mediated cytotoxicity.

Discussion

In the present study, a humanized variant of Cetuximab did not inhibit the growth of KRAS‐mutated A549 cells, but triggered limited ADCC activity against these cells. Interestingly, established approaches to enhance ADCC activity of antibodies by protein‐ or glyco‐engineering significantly improved killing against a panel of KRAS‐mutated tumor cells by MNC effector cells. This difference between wild‐type and Fc‐engineered antibodies is well explained by the higher affinity of the latter for FcγRIIIa – the predominant Fcγ receptor on human natural killer (NK) cells( 38 ) that constitute the main effector cell population in MNC. Interestingly, protein‐engineered antibodies with increased binding affinity for FcγRIIIa (I332E and S239D/I332E) demonstrated lower ADCC activity with PMN effector cells than the respective wild‐type antibody (Fig. 3D). We have previously reported similar results for glyco‐engineered variants of the EGF‐R antibody Zalutumumab where low‐fucosylated compared to completely‐fucosylated Zalutumumab demonstrated higher binding to FcγRIIIa, improved ADCC by MNC effector cells, but reduced tumor cell killing by PMN.( 39 ) Similar results were observed in the present study with a glyco‐variant of the humanized Cetuximab antibody (data not shown). These unexpected results with PMN effector cells may be explained by the homology between FcγRIIIa and the PMN‐expressed FcγRIIIb. Thus, improving the affinity for FcγRIIIa simultaneously increases binding to FcγRIIIb,( 39 ) which is not a cytotoxic trigger molecule on PMN.( 44 ) Glyco‐engineering predominantly modulates binding affinity to FcγRIIIa, while protein‐engineering can alter binding characteristics to FcγRIIIa and FcγRIIa, as well as FcγRI and FcγRIIb.( 41 ) Whether these differential FcγR binding profiles of protein‐ and glyco‐engineered antibodies will impact their therapeutic effects in vivo will require further studies.

Notably, Fc‐engineered EGF‐R antibodies proved more effective than the wild‐type antibody in ADCC against both KRAS‐unmutated and ‐mutated cell lines (3, 4, 5). The negative impact of KRAS mutations on the clinical efficacy of EGF‐R antibodies in CRC has now been confirmed in numerous clinical trials (reviewed in reference( 15 )), while more preliminary studies in NSCLC patients suggested that the KRAS status may not be predictive for Cetuximab’s efficacy in these patients.( 8 , 45 ) Presently, it is not clear whether these differences are explained by statistical considerations (lower response rates and lower incidence of KRAS mutations in NSCLC vs CRC) or whether they reflect biological differences between both tumor types. There is experimental evidence to suggest that the relative contribution of antibodies’ effector mechanisms depends on antibody concentrations( 28 ) and potentially on the tumor location.( 46 ) Further studies are required to address these interesting issues.

Results from in vitro studies with tumor cell lines are often confounded by multiple genetic abnormalities that are commonly observed in these cells. These often poorly defined alterations impair the interpretation of results with respect to specific mutations. Thus, results presented in 4, 5 demonstrate that KRAS‐mutated tumor cells can be killed by ADCC, and that mutated KRAS is not sufficient to render tumor cells resistant to ADCC, but they do not allow the direct assessment of the impact of KRAS mutations on the susceptibility of tumor cells against ADCC. To address this important issue, wild‐type KRAS‐expressing A431 cells were transfected with oncogenic KRAS4b G12V or a control vector. Interestingly, both cell lines were similarly susceptible to MNC‐mediated ADCC by EGF‐R antibodies. Furthermore, HCT‐116 cells additionally carry an activating PI3K mutation (http://www.sanger.ac.uk), which is discussed as another mechanism of resistance against EGF‐R antibodies.( 47 ) Our preliminary results suggest that also this mechanism of resistance could be overcome by Fc‐engineered EGF‐R antibodies. Potentially, enhancing Fc‐mediated effector functions of EGF‐R antibodies – such as ADCC and CDC – may prove as a more general approach to overcome resistance against EGF‐R‐directed therapy.( 48 )

An important question is whether our in vitro results have relevance for the understanding of the mechanisms of action for EGF‐R antibodies in vivo, and whether they impact potential approaches to enhance the efficacy of EGF‐R directed therapy. Recent recommendations suggested to exclude patients with KRAS‐mutated CRC from EGF‐R directed therapies, as they showed low response rates in clinical trials.( 10 , 11 , 12 ) These clinical observations supported the concept that inhibition of EGF‐R‐mediated signaling might be the predominant mechanism of action for EGF‐R antibodies. Accordingly, activating mutations of downstream signaling molecules – like KRAS or v‐raf murine sarcoma viral oncogene homolog B1 (B‐RAF) – would render tumor cells resistant to EGF‐R inhibitors.( 13 , 14 ) Further support for the contribution of Fc‐mediated effector mechanisms for Cetuximab’s clinical efficacy was derived from statistical correlations between Fcγ receptor alloforms and clinical outcomes.( 29 ) These studies suggested that Fc‐mediated effector functions were relevant for Cetuximab’s clinical efficacy in CRC patients – as previously demonstrated for other therapeutically approved antibodies.( 31 , 49 , 50 ) Importantly, individual patients with favorable Fcγ receptor alloforms (FcγRIIa‐131H and/or FcγRIIIa‐158V) responded to Cetuximab therapy – even when their tumors harbored oncogenic KRAS mutations.( 29 ) As previously reported by others,( 38 ) Fc engineering improved ADCC by FcγRIIIa‐158F/F, ‐158F/V, and 158V/V donors.

Presently, there is a wide gap between results from in vitro models addressing mechanisms of sensitivity and resistance against EGF‐R‐directed antibody therapy and clinical data that validate them. Unfortunately, studies in small animals are of limited value for many of these specific questions due to differences between the murine and the human Fcγ receptor systems. In studies investigating the impact of Fc engineering on antibody efficacy, those differences in species characteristics additionally impede the transfer of in vitro results to in vivo relevance.( 51 ) On the other hand, protein‐ and glyco‐engineered antibodies against other target antigens (e.g. CD30, CD20) have already entered clinical trials, while trials with glyco‐engineered EGF‐R antibodies are expected to start soon. Another approach to clinically assess the contribution of ADCC versus other antibody effector mechanisms would include studies that prospectively investigate the impact of Fcγ receptor polymorphisms on therapeutic outcomes, for example in FcγRIIIa‐158V/V donors, as is currently on‐going for Trastuzumab (a humanized monoclonal IgG1 antibody directed against human epidermal growth factor receptor 2, ErbB2).

In conclusion, KRAS‐mutated tumor cells can be effectively killed by ADCC, indicating that mutated KRAS is not sufficient to confer resistance to antibody‐mediated effector cell killing. Consequently, approaches to enhance ADCC may have the potential to increase the clinical activity of EGF‐R antibodies – particularly in patients whose tumors harbor activating KRAS mutations.

Disclosure Statement

Greg A. Lazar is employed by Xencor, Monrovia, CA, USA.

Supporting information

Fig. S1. Antibody expression in LEC13 cells resulted in an afucosylated variant of 225‐IgG1. Expression constructs harboring the light‐ and heavy‐chain cDNAs of the 225 antibody were expressed in LEC13 and CHO‐K1 cells by transient transfection. The purified antibodies were analyzed by SDS‐PAGE and immunoblotting with HRP‐conjugated antihuman‐IgG antibodies and a HRP‐conjugated Aleuria Aurantia lectin specific for fucose linked (α‐1,6) to N‐acetylglucosamine or (α‐1,3) to N‐acetyllactosamine‐related structures. Lane 1 = 225‐IgG1 expressed in LEC13 cells; lane 2 = 225‐IgG1 expressed in CHO‐K1 cells. One representative experiment out of three performed is shown.

Fig. S2. Fc engineering did not influence F(ab′)‐mediated effector functions. To characterize the antibody variants’ F(ab′)‐mediated effector functions, MTS assays with wild‐type KRAS‐expressing A431 cells and oncogenic KRAS‐expressing A549 cells were performed. Inhibition of cell growth was analyzed by incubating cells in the presence or absence of increasing concentrations (see above) of the antibodies. After 72 h, vital cell masses were measured by MTS assays. *P < 0.05 control vs wild‐type antibody.

Please note: Wiley‐Blackwell are not responsible for the content or functionality of any supporting materials supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the corresponding author for the article.

Supporting info item

Supporting info item

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Christyn Wildgrube, Beatrix Berger, and Sher Karki for excellent technical assistance. This work was supported by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Va 124/7‐1 and De 1478/1‐1), from Genmab (Utrecht, The Netherlands), and from intramural grants of Christian‐Albrechts‐University, Kiel.

References

- 1. Mendelsohn J. Targeting the epidermal growth factor receptor. J Clin Oncol 2002; 20: 1s–13s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kumar A, Petri ET, Halmos B, Boggon TJ. Structure and clinical relevance of the epidermal growth factor receptor in human cancer. J Clin Oncol 2008; 26: 1742–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ciardiello F, Tortora G. EGFR antagonists in cancer treatment. N Engl J Med 2008; 358: 1160–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Krause DS, Van Etten RA. Mechanisms of disease: tyrosine kinases as targets for cancer therapy. N Engl J Med 2005; 353: 172–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pao W, Miller VA. Epidermal growth factor receptor mutations, small‐molecule kinase inhibitors, and non‐small‐cell lung cancer: current knowledge and future directions. J Clin Oncol 2005; 23: 2556–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Peipp M, Schneider‐Merck T, Dechant M et al. Tumor cell killing mechanisms of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) antibodies are not affected by lung cancer‐associated EGFR kinase mutations. J Immunol 2008; 180: 4338–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Doody JF, Wang YF, Patel SN et al. Inhibitory activity of cetuximab on epidermal growth factor receptor mutations in non‐small cell lung cancers. Mol Cancer Ther 2007; 6: 2642–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Khambata‐Ford S, Harbison CT, Hart LL et al. Analysis of potential predictive markers of cetuximab benefit in BMS099, a phase III study of cetuximab and first‐line taxane/carboplatin in advanced non‐small‐cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 2010; Jan 25 (E pub ahead of print). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Van Cutsem E, Kohne C‐H, Hitre E et al. Cetuximab and chemotherapy as initial treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med 2009; 360: 1408–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Karapetis CS, Khambata‐Ford S, Jonker DJ et al. K‐ras mutations and benefit from cetuximab in advanced colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med 2008; 359: 1757–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Amado RG, Wolf M, Peeters M et al. Wild‐type KRAS is required for panitumumab efficacy in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 2008; 26: 1626–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bokemeyer C, Bondarenko I, Makhson A et al. Fluorouracil, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin with and without cetuximab in the first‐line treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 2009; 27: 663–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Di Nicolantonio F, Martini M, Molinari F et al. Wild‐type BRAF is required for response to panitumumab or cetuximab in metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 2008; 26: 5705–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mitsudomi T, Yatabe Y. Mutations of the epidermal growth factor receptor gene and related genes as determinants of epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors sensitivity in lung cancer. Cancer Sci 2007; 98: 1817–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Allegra CJ, Jessup JM, Somerfield MR et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology provisional clinical opinion: testing for KRAS gene mutations in patients with metastatic colorectal carcinoma to predict response to anti‐epidermal growth factor receptor monoclonal antibody therapy. J Clin Oncol 2009; 27: 2091–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Downward J. Prelude to an anniversary for the RAS oncogene. Science 2006; 314: 433–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Schubbert S, Shannon K, Bollag G. Hyperactive Ras in developmental disorders and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2007; 7: 295–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Braun BS, Shannon K. Targeting Ras in myeloid leukemias. Clin Cancer Res 2008; 14: 2249–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tanaka T, Williams RL, Rabbitts TH. Tumor prevention by a single antibody domain targeting the interaction of signal transduction proteins with Ras. EMBO J 2007; 26: 3250–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Karnoub AE, Weinberg RA. Ras oncogenes: split personalities. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2008; 9: 517–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Downward J. Targeting RAS and PI3K in lung cancer. Nat Med 2008; 14: 1315–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Peipp M, Dechant M, Valerius T. Effector mechanisms of ErbB antibodies. Curr Opin Immunol 2008; 20: 436–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Houghton AN, Scheinberg DA. Monoclonal antibody therapies – a ‘constant’ threat to cancer. Nat Med 2000; 6: 373–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Dechant M, Weisner W, Berger S et al. Complement‐dependent tumor cell lysis triggered by combinations of epidermal growth factor receptor antibodies. Cancer Res 2008; 68: 4998–5003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dechant M, Beyer T, Schneider‐Merck T et al. Effector mechanisms of recombinant IgA antibodies against epidermal growth factor receptor. J Immunol 2007; 179: 2936–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Clynes RA, Towers TL, Presta LG, Ravetch JV. Inhibitory Fc receptors modulate in vivo cytotoxicity against tumor targets. Nat Med 2000; 6: 443–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Nimmerjahn F, Ravetch JV. Divergent immunoglobulin G subclass activity through selective Fc receptor binding. Science 2005; 310: 1510–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bleeker WK, Van Bueren JJL, Van Ojik HH et al. Dual mode of action of a human anti‐epidermal growth factor receptor monoclonal antibody for cancer therapy. J Immunol 2004; 173: 4699–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bibeau F, Lopez‐Crapez E, Di Fiore F et al. Impact of FcγRIIa‐FcγRIIIa polymorphisms and KRAS mutations on the clinical outcome of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer treated with cetuximab plus irinotecan. J Clin Oncol 2009; 27: 1122–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zhang W, Gordon MS, Schultheis AM et al. FCGR2A and FCGR3A polymorphisms associated with clinical outcome of epidermal growth factor receptor expressing metastatic coloreactal cancer patients treated with single‐agent cetuximab. J Clin Oncol 2007; 25: 3712–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Musolino A, Naldi N, Bortesi B et al. Immunoglobulin G fragment C receptor polymorphisms and clinical efficacy of trastuzumab‐based therapy in patients with HER‐2/neu‐positive metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2008; 26: 1789–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Van De Winkel JGJ, Anderson CL. Biology of human immunoglobulin G Fc receptors. J Leukoc Biol 1991; 49: 511–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kimberly RP, Salmon JE, Edberg JC. Receptors for immunoglobulin G. Molecular diversity and implications for disease. Arthritis Rheum 1995; 38: 306–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Carter PJ. Potent antibody therapeutics by design. Nat Rev Immunol 2006; 6: 343–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Jefferis R. Glycosylation as a strategy to improve antibody‐based therapeutics. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2009; 8: 226–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Umana P, Jean‐Mairet J, Moudry R, Amstutz H, Bailey JE. Engineered glycoforms of an antineuroblastoma IgG1 with optimized antibody‐dependent cellular cytotoxic activity. Nat Biotechnol 1999; 17: 176–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Niwa R, Hatanaka S, Shoji‐Hosaka E et al. Enhancement of the antibody‐dependent cellular cytotoxicity of low‐fucose IgG1 is independent of FcγRIIIa functional polymorphism. Clin Cancer Res 2004; 10: 6248–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lazar GA, Dang W, Karki S et al. Engineered antibody Fc variants with enhanced effector function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2006; 103: 4005–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Peipp M, Lammerts van Bueren J, Schneider‐Merck T et al. Antibody fucosylation differentially impacts cytotoxicity mediated by NK and PMN effector cells. Blood 2008; 112: 2390–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lazar GA, Desjarlais JR, Jacinto J, Karki S, Hammond PW. A molecular immunology approach to antibody humanization and functional optimization. Mol Immunol 2007; 44: 1986–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Richards JO, Karki S, Lazar GA, Chen H, Dang W, Desjarlais JR. Optimization of antibody binding to FcγRIIa enhances macrophage phagocytosis of tumor cells. Mol Cancer Ther 2008; 7: 2517–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Yu SH, Wang TH, Au LC. Specific repression of mutant K‐RAS by 10‐23 DNAzyme: sensitizing cancer cell to anti‐cancer therapies. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2009; 378 (2): 230–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Balko JM, Potti A, Saunders C, Stromberg A, Haura EB, Black EP. Gene expression patterns that predict sensitivity to epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors in lung cancer cell lines and human lung tumors. BMC Genomics 2006; 7: 289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Stockmeyer B, Valerius T, Repp R et al. Preclinical studies with Fc(gamma)R bispecific antibodies and granulocyte colony‐stimulating factor‐primed neutrophils as effector cells against HER‐2/neu overexpressing breast cancer. Cancer Res 1997; 57: 696–701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. O’Byrne KJ, Bondarenko I, Barrios C et al. Molecular and clinical predictors of outcome for cetuximab in non‐small cell lung cancer: data from the FLEX study. J Clin Oncol 2009; 27 (Suppl): abstract 8007. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Schneider‐Merck T, Lammerts van Bueren JJ, Berger S et al. Human IgG2 antibodies against epidermal growth factor receptor effectively trigger antibody‐dependent cellular cytotoxicity but, in contrast to IgG1, only by cells of myeloid lineage. J Immunol 2010; 184: 512–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Perrone F, Lampis A, Orsenigo M et al. PI3KCA/PTEN deregulation contributes to impaired responses to cetuximab in metastatic colorectal cancer patients. Ann Oncol 2009; 20: 84–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Peipp M, Dechant M, Valerius T. Sensitivity and resistance to EGF‐R inhibitors: approaches to enhance the efficacy of EGF‐R antibodies. MAbs 2009; 1: 590–599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Weng WK, Levy R. Two immunoglobulin G fragment C receptor polymorphisms independently predict response to rituximab in patients with follicular lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 2003; 21: 3940–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Cartron G, Dacheux L, Salles G et al. Therapeutic activity of humanized anti‐CD20 monoclonal antibody and polymorphism in IgG Fc receptor FcgammaRIIIa gene. Blood 2002; 99: 754–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Loisel S, Ohresser M, Pallardy M et al. Relevance, advantages and limitations of animal models used in the development of monoclonal antibodies for cancer treatment. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2007; 62 (1): 34–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1. Antibody expression in LEC13 cells resulted in an afucosylated variant of 225‐IgG1. Expression constructs harboring the light‐ and heavy‐chain cDNAs of the 225 antibody were expressed in LEC13 and CHO‐K1 cells by transient transfection. The purified antibodies were analyzed by SDS‐PAGE and immunoblotting with HRP‐conjugated antihuman‐IgG antibodies and a HRP‐conjugated Aleuria Aurantia lectin specific for fucose linked (α‐1,6) to N‐acetylglucosamine or (α‐1,3) to N‐acetyllactosamine‐related structures. Lane 1 = 225‐IgG1 expressed in LEC13 cells; lane 2 = 225‐IgG1 expressed in CHO‐K1 cells. One representative experiment out of three performed is shown.

Fig. S2. Fc engineering did not influence F(ab′)‐mediated effector functions. To characterize the antibody variants’ F(ab′)‐mediated effector functions, MTS assays with wild‐type KRAS‐expressing A431 cells and oncogenic KRAS‐expressing A549 cells were performed. Inhibition of cell growth was analyzed by incubating cells in the presence or absence of increasing concentrations (see above) of the antibodies. After 72 h, vital cell masses were measured by MTS assays. *P < 0.05 control vs wild‐type antibody.

Please note: Wiley‐Blackwell are not responsible for the content or functionality of any supporting materials supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the corresponding author for the article.

Supporting info item

Supporting info item