Abstract

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a presently incurable B‐cell malignancy, and newer biologically based therapies are needed. Arsenic trioxide (ATO) has been established as a therapeutic agent for relapsed acute promyelocytic leukemia patients, and has been used for MM patients in clinical trials. In this study, we investigated the role of c‐jun‐N‐terminal kinase (JNK) in ATO‐induced apoptosis in MM lines. The exogenous interleukin (IL)‐6 dependent MM line, ILKM‐3, and independent MM lines, U266 and XG‐7, were treated with a therapeutic concentration of ATO with or without JNK inhibitor 1 (a JNK‐specific inhibitor) and anisomycin (a JNK activator). Their cell growth, cell cycle, JNK activation and NF‐κB activation were investigated. ATO induced apoptosis in U266 and ILKM‐3 regardless of their exogenous IL‐6 dependency. This apoptosis, accompanied with decreased mitochondrial transmembrane potential, sustained activation of JNK but not cell cycle arrest. Pretreatment of JNK inhibitor prevented ATO‐induced apoptosis in ATO‐sensitive lines. Combined treatment with ATO and anisomycin induced sustained activation of JNK and apoptosis in the ATO‐insensitive MM line, XG‐7. Results of various time period treatments of ATO showed that sustained activation of JNK was needed in ATO‐induced apoptosis in MM. IkBα phosphorylation was not associated with ATO‐sensitivity of MM lines. These findings suggest that sustained activation of JNK plays a critical role in ATO‐induced apoptosis in MM cell lines. Cotreatment with ATO and the agent, which can induce sustained activation of JNK, might improve the outcome in MM therapy. (Cancer Sci 2006; 97)

Multiple myeloma (MM) is an incurable hematological malignancy, characterized by the clonal proliferation of malignant plasma cells associated in most patients with the production of monoclonal immunoglobulins. With standard therapy, the median survival rate of MM patients is 3 years and the 5‐year median survival rate is approximately 25%, fewer than 5% are alive at 10 years.( 1 , 2 ) Despite intensive or newer treatments, including alkylating agents, anthracyclins, corticosteroids, thalidomide and high‐dose therapy with stem cell transplantation, the 5‐year median survival rate is 32% and the 10‐year median survival rate is 3%.( 3 )

Arsenic trioxide (ATO) has been shown to be effective in the treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL).( 4 , 5 ) ATO also has been clinically studied as a single agent( 6 ) and in combination with ascorbic acid( 7 ) and melphalan,( 8 ) has been reported to be safe and to have some antimyeloma activity. The mechanism of ATO‐induced antimyeloma activity has been studied, however, the concentration of ATO used in those studies was higher than the pharmacological concentration (1–2 µM).( 9 , 10 )

We previously reported that sustained activation of c‐jun‐N‐terminal kinase (JNK) plays an important role in ATO‐induced apoptosis in not only APL but also in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) cell lines.( 11 ) Here we show sustained activation of JNK is observed in ATO‐induced apoptosis in MM cell lines and that inhibition of JNK activation restores the viability of ATO‐treated MM cells. Pretreatment of the JNK activator, anisomycin, increases the sensitivity to ATO in the ATO‐insensitive MM cell line, suggesting that combined therapy with the drugs inducing sustained activation of JNK could enhance its antimyeloma activity in vivo.

Materials and Methods

Cells

The exogenous interleukin (IL)‐6 dependent MM cell line, ILKM‐3,( 12 ) and independent MM cell lines, U266( 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 ) and XG‐7,( 17 ) were kindly provided by Dr Shiro Shimizu (Shimane Prefectural Central Hospital, Izumo, Japan) and Dr Bernard Klein (Institute for Molecular Genetics, Montpellier, France). ILKM‐3 was maintained in RPMI 1640 (Gibco BRL, Life Technologies, NY, USA) with 10% heat‐inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS) and 2 ng/mL human recombinant IL‐6 (Kirin Brewery, Tokyo, Japan). U266 and XG‐7 were maintained in RPMI 1640 with 10% FCS.

Reagents

ATO was purchased from Sigma (St Louis, MO, USA), and the 0.1 g/mL solution of ATO was prepared at Nagoya University Graduate School of Medicine, Department of Hospital Pharmacy. The 3,39‐dihexy‐loxacarbocyanine (DiOC6) was obtained from Molecular Probes (Interchim, France). Anisomycin and N‐acetylcysteine (NAC) were purchased from Sigma. (L)‐JNKI1 (JNK inhibitor‐1) was purchased from Calbiochem (Bad Soden, Germany). Annexin‐V‐PE and binding buffer for annexin‐V were purchased from MBL (Nagoya, Japan).

Growth inhibition assays

Tetracolor one cell proliferation assay (Seikagaku, Tokyo, Japan) was performed following the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, the cells (1 × 104/well) were added to 96‐well plates in 100 µL RPMI containing 10% FCS in the presence or absence of IL‐6 (2 ng/mL) with varying concentrations of ATO, JNK inhibitor‐1, anisomycin and NAC. The plates were incubated at 37°C for varying time periods and then a mixture of tetrazolium (2‐(2‐methoxy‐4‐nitrophenyl)‐3‐(4‐nitrophenyl)‐5‐(2,4‐disulfophenyl)‐2H‐tetrazolium, monosodium salt) and electron carrier (1‐methoxy‐5‐methylphenazium methylsulfate; final volume 110 µL/well) was added. The cells were incubated for an additional hour at 37°C, and the absorption of 450 nm was measured using an enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) plate reader.

Cell cycle analysis

Cells were washed with cold phosphate‐buffered saline (PBS) and then fixed with cold 70% ethanol. Fixed cells were incubated with 10 µg/mL of RNase A (Roche, Japan) and 5 µg/mL propidium iodine (PI; Sigma) for 10 min, then DNA contents were measured by FACScan flow cytometry (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA).

Analysis of apoptosis and mitochondrial transmembrane potential (Δψm)

After drug treatment, 1 × 106 cells were washed in PBS and resuspended in 500 µL staining solution containing 5 µL of annexin‐V‐PE and 40 nM of DiOC6 in a binding buffer. After 15‐min incubation at room temperature, the cells were analyzed by FACScan flow cytometry, with an excitation and emission setting of 495 and 525 nm, respectively.

Western blot analysis

Cells were lyzed by adding an equal volume of a two‐fold concentrated sample buffer (125 mM Tris‐HCl, pH 6.8, 4% SDS, 10% 2‐mercaptoethanol, 20% glycerol) then protein samples were subjected to 8–12% sodium dodecyl sulfate‐polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS‐PAGE), and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. After blocking with 5% non‐fat milk, the membrane was incubated with primary antibodies as follows: antiphospho‐specific SAPK/JNK (Thr183/Tyr185), anti‐SAPK/JNK, antiphospho‐specific IkB and anti‐IkB, all purchased from Cell Signaling (Beverly, MA, USA). Primary antibodies were detected by horseradish peroxidase‐conjugated secondary antibody (1:2000), and were visualized by chemiluminescence (ECL; Amersham, Buckinghamshire, UK). For reprobing, the membranes were stripped (2% SDS, 62.5 mM Tris, pH 6.8, 100 mM 2‐ME, 50°C, 30 min) and reprobed with the corresponding antibodies.

Results

ATO induce apoptosis in MM cell lines regardless of their exogenous IL‐6 dependency

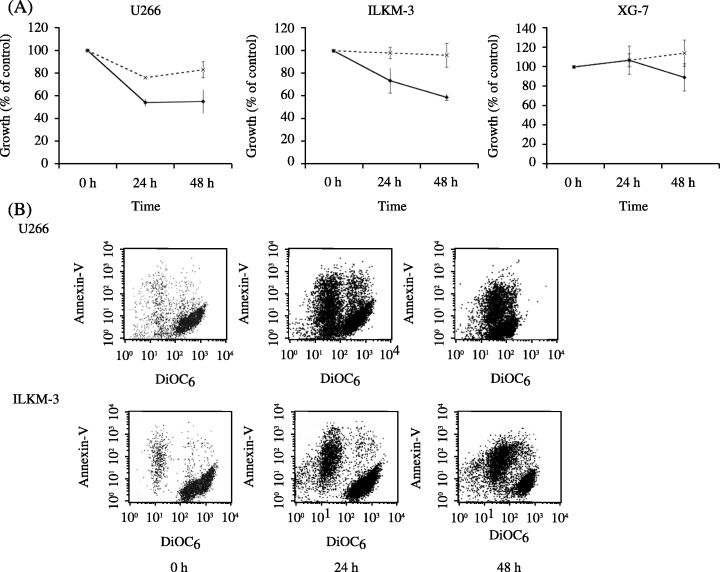

We first investigated the effects of ATO on proliferation of MM cell lines. As the therapeutic concentration, 1 µM and 2 µM of ATO were used. Although 1 µM ATO inhibited the cell growth of U266, which is an exogenous IL‐6 independent cell line,( 13 , 14 , 16 ) no remarkable change was observed in the other two cell lines, XG‐7 (IL‐6 independent)( 17 ) and ILKM‐3 (IL‐6 dependent).( 12 ) Two µM solution of ATO inhibited the cell growth in U266 and ILKM‐3, but not in XG‐7 (Fig. 1A). To investigate the mechanism of ATO‐induced cell growth inhibition in MM cell lines, cells were stained with PI and analyzed for DNA content by flow cytometry. As shown in Table 1, the amount of cells in the sub‐G1 phase increased in each ATO‐sensitive cell line as time progressed. In these examinations, no sign of cell cycle arrest was observed. We previously reported that ATO induces apoptosis in AML cells through the decrease of mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψm). To examine if the decrease of Δψm is involved in ATO‐induced apoptosis in MM cell line, Δψm of ATO‐treated MM cell lines was measured by using DiOC6 11 , 18 and annexin‐V by flow cytometry. As shown in Figure 1B, Δψm decreased as time progressed, accompanied with an increase in annexin‐V fluorescent intensity. After 24 h treatment, annexin‐V‐negative cells, which have already shown a decrease of Δψm, were observed. These results suggest that ATO induces cell apoptosis through the decrease of Δψm, but not cell cycle arrest in IL‐6 dependent and independent MM cell lines.

Figure 1.

(A) Cell growth assay. Cells were incubated in a culture medium with different concentrations of arsenic trioxide (ATO) for the time periods indicated. Cell growth was determined by Tetracolor One cell proliferation assay. Results show the mean ± SE of five independent experiments. (‐‐×‐‐) 1 µM; (‐•‐) 2 µM. (B) Analysis of apoptosis and mitochondrial transmembrane potential. U266 and ILKM‐3 cells were treated with 2 µM ATO for the time periods indicated, stained with DiOC6 (40 nM) and annexin‐V‐PE (5 µM) in a binding buffer, and subjected to flow‐cytometric analysis. Representative results of three experiments with consistent results are shown.

Table 1.

Cell cycle analysis

| ILKM‐3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| sub‐G1 | G0/G1 | S | G2/M | |

| 5.96 | 72.34 | 5.8 | 15.67 | 0 h |

| 6.66 | 73.91 | 5.42 | 13.96 | 12 h |

| 11.42 | 66.84 | 7.6 | 14.88 | 24 h |

| 82.62 | 11.51 | 3.11 | 3.18 | 48 h |

| U266 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| sub‐G1 | G0/G1 | S | G2/M | |

| 4.71 | 44.67 | 9.92 | 19.74 | 0 h |

| 6.52 | 40.57 | 13.98 | 12.43 | 12 h |

| 15.16 | 40.42 | 10.44 | 10.65 | 24 h |

| 44.42 | 22.13 | 8.95 | 10.28 | 48 h |

Arsenic trioxide (ATO)‐treated ILKM‐3 and U266 cells were stained with PI and assayed using FACScan. Population of each cycle was measured by Cell Quest software. Representative results of three experiments with consistent results are shown.

Involvement of sustained activation of JNK in ATO‐induced apoptosis in MM cell lines

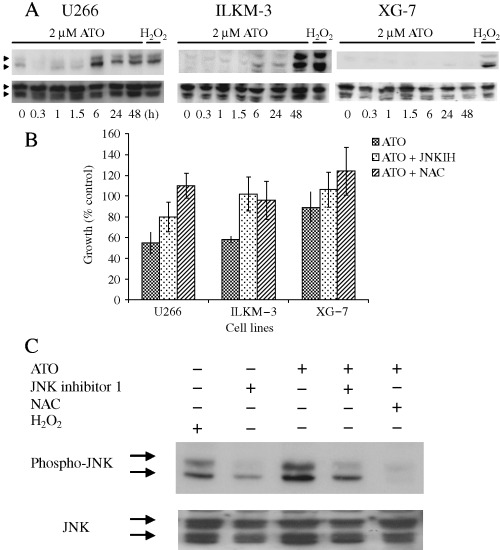

Activation of JNK has been reported to be involved in PS‐341‐induced apoptosis in MM cells,( 19 ) and to be involved in ATO‐induced apoptosis in AML cells.( 11 ) Therefore, we investigated the activation status of JNK in ATO‐treated MM cell lines by western blot analysis. As shown in Figure 2A, sustained activation of JNK was observed in the ATO‐sensitive cell lines, U266 and ILKM‐3, but not in the insensitive cell line, XG‐7. In U266 and ILKM‐3, JNK was activated from 6 h to 48 h. Compared to U266, JNK activation in ILKM‐3 was mild at 6 h and 24 h after the treatment. No JNK activation was detected in ATO‐treated XG‐7 cells. To further determine the effect of JNK on ATO‐induced apoptosis in MM cell lines, JNK inhibitor‐1, a cell‐permeable peptide inhibitor, was used. Pretreating the cells with 1 µM of JNK inhibitor‐1 for 1 h restored ATO‐induced cell growth inhibition in U266 and ILKM‐3 cell lines (Fig. 2B). NAC, which is a potent antioxidant, has been reported to block ATO‐induced apoptosis.( 11 , 20 ) Pretreatment of the cells with 10 µM of NAC for 1 h prevented ATO‐induced cell growth inhibition in MM cell lines (Fig. 2B). Pretreatment of these reagents also inhibited ATO‐induced activation of JNK (Fig. 2C).

Figure 2.

(A) Effects of arsenic trioxide (ATO) on the activities of JNK. After treatment with 2 µM ATO for the indicated time periods, cells were lyzed and subjected to immunoblot assay with antiphospho‐JNK antibody (upper panel). Membranes were stripped and reprobed with the anti‐JNK antibody (lower panel). (B,C) Addition of the cell‐permeable peptide inhibitor of JNK and N‐acetylcysteine (NAC) inhibited ATO‐induced cell growth inhibition (B) and JNK activation (C). Cells were treated with ATO (2 µM for 48 h), with or without pretreatment of JNK inhibitor‐1 (1 µM for 1 h) and NAC (10 µM for 1 h). Cell growth (U266, ILKM‐3 and XG‐7) was determined using Tetracolor One. Results show the mean ± SE of five independent experiments. JNK activation (U266) was analyzed by western blot analysis.

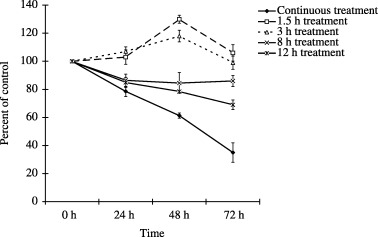

Critical period of ATO‐induced cell growth inhibition in MM cell lines

To clarify the importance of sustained activation of JNK in ATO‐induced MM cell growth suppression, U266 cells were treated with ATO for several hours. As shown in Figure 3, there was no major growth suppression observed in the cells treated for 1.5 h or 3 h. In the cells treated for 8 h, the period when phosphorylation of JNK started to be detected by western blot analysis, cell growth was suppressed for 86.4% of control after 24 h and for 86% of control after 72 h. In cells treated for 12 h, cell growth was suppressed for 84.9% of control after 24 h and for 69% of control after 72 h. These results suggest that sustained, not transient, activation of JNK was involved in ATO‐induced cell growth inhibition in the U266 cell line.

Figure 3.

Critical period of arsenic trioxide (ATO)‐induced cell growth inhibition. U266 cells were treated with ATO for the time periods indicated. After the treatment, cells were washed with cold phosphate‐buffered saline (PBS), and then resuspended in 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) containing RPMI‐1640. Cell growth was measured by Tetracolor One proliferation assay.

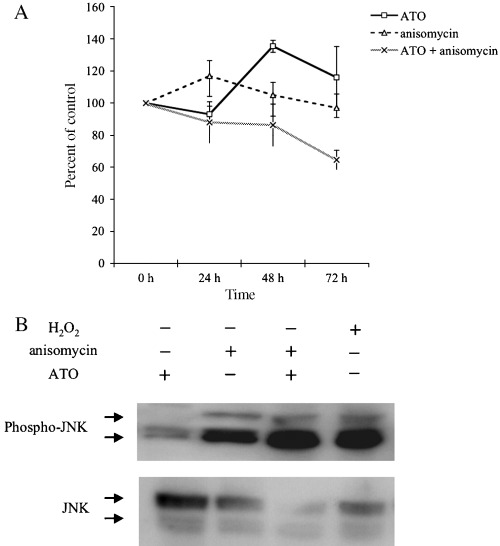

Cotreatment with anisomycin and ATO induces cell growth inhibition in ATO‐insensitive MM cell line

It was reported that treating the cells with anisomycin induced degradation of JNK phosphatase, resulting in activation of JNK.( 21 ) Although treatment with 20 ng/mL of anisomycin or 1 µM of ATO alone did not suppress cell growth in the XG‐7 cell line, cotreatment with anisomycin and ATO induced cell growth inhibition in XG‐7 (Fig. 4A). As shown in Figure 4B, JNK was phosphorylated more strongly in cotreated cells than in the cells treated with anisomycin or ATO alone. These results suggested that there was a threshold of JNK activation to induce growth inhibition, or other growth inhibitory pathways other than JNK activation.

Figure 4.

Combination treatment of anisomycin and arsenic trioxide (ATO)‐induced sustained activation of JNK and suppressed cell growth of XG‐7 cell line. (A) Cell growth assay with or without ATO and anisomycin. Cells were treated with or without ATO (1 µM) and anisomycin (20 ng/mL) for the time periods indicated. Cell growth was determined by Tetracolor One cell proliferation assay. Results show the mean ± SE of three independent experiments. (B) Effect of combination therapy of ATO and anisomycin on JNK activation. Cells were treated for 6 h with or without ATO (1 µM), anisomycin (20 ng/mL) and H2O2 (1 mM). JNK activation was measured by western blot analysis.

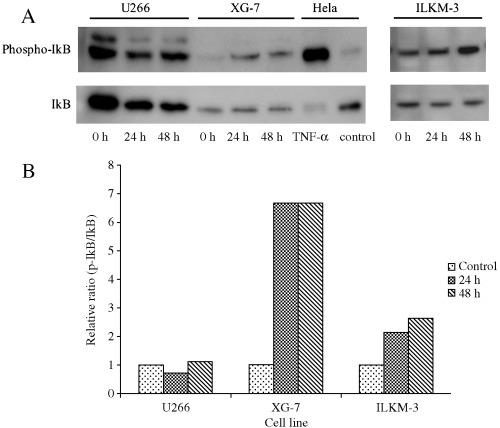

Effect of ATO in phosphorylation of IkB in MM cell lines

NF‐κB is supposed to be an important target in MM. It was reported that PS‐341 inhibits NF‐κB activation in MM cells by stabilizing IkBα.( 22 ) In addition, a high concentration of ATO reportedly suppressed tumor necrosis factor (TNF)‐α‐induced NF‐κB activation in HeLa cells and bone marrow stromal cells.( 23 ) To determine if inhibition of NF‐κB is involved in the therapeutic concentration of ATO‐induced cell growth inhibition in MM cell lines as the other pathway other than JNK activation, phosphorylation of IkBα was examined. As shown in Fig. 5A, in U266, IkBα was already phosphorylated before ATO treatment. After 48 h ATO treatment, phosphorylated IkBα slightly increased and the total amount of IkBα protein decreased compared with that of 24 h treatment. Conversely, in ILKM‐3, the protein level of total IkBα did not change and phosphorylation of IkBα was increased after 48 h. In XG‐7, ATO increased phosphorylated IkBα after 24 h but had no effect on total expression of IkBα. Analysis of optical density ratio (phospho‐IkB/IkB) showed that the relative ratio was increased in XG‐7 and ILKM‐3 during ATO treatment, but scanty changes were observed in U266 (Fig. 5B). These results indicated that ATO induced IkBα phosphorylation in both ATO‐sensitive and insensitive cell lines, although there was no consistency in change of IkBα protein amount, suggesting that IkBα phosphorylation is not associated with ATO sensitivity of MM lines.

Figure 5.

Effect of arsenic trioxide (ATO) in phosphorylation of IkB in multiple myeloma (MM) cell lines. Cells were treated with ATO (2 µM) for the time period indicated, then lyzed in the lysis buffer. Total cell extracts from untreated HeLa and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)‐α treated HeLa were used as negative and positive controls, respectively. Phosphorylation of IkB was analyzed by western blot analysis using antiphospho‐IkB and anti‐IkB antibody (A). Optical density was measured by NIH Image software. The value obtained from 0 h treatment was arbitrarily set to 1 (control), and the values obtained from 24 and 48 h treatment were adjusted accordingly (B).

Discussion

ATO has been shown to have two major effects on the growth inhibition of MM cells; a direct effect and an indirect effect. As a direct effect, induction of cell cycle arrest,( 24 ) induction of apoptosis( 25 ) and inhibition of NF‐κB activation( 26 ) have been reported. Conversely, an increase in lymphokine‐activated killer (LAK) mediated killing and decreased MM cell binding to bone marrow stromal cells were reported as an indirect effect.( 27 ) These studies of the direct effect of ATO in MM cells were performed using a higher concentration than the therapeutic concentration (1–2 µM). In this study, therapeutic concentration of ATO (2 µM) was used for investigating the direct effect of ATO in MM cells. Our study showed that the therapeutic concentration of ATO induced apoptosis in MM cell lines through a decrease of Δψm without cell cycle arrest. This apoptosis was accompanied by sustained activation of JNK. Results of experiments using the JNK specific inhibitor and anisomycin showed that activation of JNK was involved in ATO‐induced apoptosis in MM cells. Moreover, sustained JNK activation was shown to be required for ATO‐induced growth inhibition in MM cells with various time period treatments of ATO. The importance of sustained activation of JNK in ATO‐induced apoptosis has been reported in AML cell lines, including the APL cell line.( 11 ) ATO is also known to induce activation of p38 MAP kinase.( 11 , 28 ) In contrast to JNK, p38 MAP kinase was activated in both ATO‐sensitive and insensitive lines from just after the administration of ATO.( 11 ) Treating the cells with p38 MAP kinase specific inhibitor, SB203580, increased ATO‐induced apoptosis accompanied with JNK activation instead of suppressing.( 28 ) In addition, proteasome inhibitor PS‐341 was reported to induce JNK activation during MM cell apoptosis, whereas JNK‐specific inhibitor SP600125 blocked PS‐341‐induced apoptosis in MM cells.( 19 ) All these findings suggest that activation of JNK plays a central role in ATO‐induced apoptosis in MM cells.

The mechanism of ATO‐induced JNK activation has been reported in several settings. M3/6 is a dual‐specificity phosphatase selective for JNK and is inactivated by a high concentration of arsenite.( 21 ) Inactivation of M3/6 resulted in accumulation of phospho‐JNK. Although the mechanism of ATO‐induced inactivation of M3/6 is still unclear, it has been suggested that As3+ may bind to thiol groups in the catalytic site of a JNK‐specific phosphatase.( 29 ) In fact, our previous and present studies showed that pretreatment with NAC, which is supposed to protect thiol groups, inhibited ATO‐induced JNK activation in AML cell lines and in MM cell lines, respectively. Inhibition of NF‐κB activation is another mechanism which is thought to be involved in ATO‐induced apoptosis in MM cells. It was reported that sodium arsenite inhibited IkB kinase activation and resulted in inhibition of NF‐κB activation.( 23 ) However, in that report, the inhibition was observed in 12.5 µM of sodium arsenite and not observed in 6.25 µM. Moreover, inhibition of NF‐κB activation has not been confirmed using therapeutic concentrations of ATO in MM cells. In our study, although a decrease of total protein level of IkB was detected in U266, no change was detected in ILKM‐3 and XG‐7. Conversely, after ATO‐treatment, phosphorylation of IkB was decreased in U266 at 24 h, and then increased. In the other cell lines, after ATO‐treatment, phosphorylation of IkB was increased from 24 h and maintained to 48 h. These data suggest that inhibition of NF‐κB might not play a central role in ATO‐induced apoptosis in MM cells.

Recently, melphalan, ascorbic acid and ATO combination therapy (MAC) was reported to be effective for relapsed and refractory MM.( 8 ) This combination therapy also is effective for Bortezomib resistant patients. These clinical findings and our data suggest that combined therapy with ATO and an agent, which can induce sustained activation of JNK, might have a good outcome in MM therapy.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mr Satoshi Suzuki and Miss Chika Wakamatsu for their excellent technical assistance, Dr Ivo Wortman for his assistance with English editing, and the Kirin Brewery (Tokyo, Japan) for the recombinant human IL‐6. This work was supported in part by a grant from the Aichi Cancer Research Foundation and in part by Grants‐in‐Aid from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan.

References

- 1. Alexanian R, Dimopoulos M. The treatment of multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med 1994; 330: 484–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Anderson KC. Who benefits from high‐dose therapy for multiple myeloma? J Clin Oncol 1995; 13: 1291–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Anderson KC. Clinical update: novel targets in multiple myeloma. Semin Oncol 2004; 31 (6 Suppl. 16): 27–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Soignet SL, Frankel SR, Douer D et al. United States multicenter study of arsenic trioxide in relapsed acute promyelocytic leukemia. J Clin Oncol 2001; 19: 3852–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Shen ZX, Shi ZZ, Fang J et al. All‐trans retinoic acid/As2O3 combination yields a high quality remission and survival in newly diagnosed acute promyelocytic leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2004; 101: 5328–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hussein MA, Saleh M, Ravandi F, Mason J, Rifkin RM, Ellison R. Phase 2 study of arsenic trioxide in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. Br J Haematol 2004; 125: 470–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bahlis NJ, McCafferty‐Grad J, Jordan‐McMurry I et al. Feasibility and correlates of arsenic trioxide combined with ascorbic acid‐mediated depletion of intracellular glutathione for the treatment of relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma. Clin Cancer Res 2002; 8: 3658–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Borad MJ, Swift R, Berenson JR. Efficacy of melphalan, arsenic trioxide, and ascorbic acid combination therapy (MAC) in relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma. Leukemia 2005; 19: 154–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zhu XH, Shen YL, Jing YK et al. Apoptosis and growth inhibition in malignant lymphocytes after treatment with arsenic trioxide at clinically achievable concentrations. J Natl Cancer Inst 1999; 91: 772–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Shen ZX, Chen GQ, Ni JH et al. Use of arsenic trioxide (As2O3) in the treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL): II. Clinical efficacy and pharmacokinetics in relapsed patients. Blood 1997; 89: 3354–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kajiguchi T, Yamamoto K, Hossain K et al. Sustained activation of c‐jun‐terminal kinase (JNK) is closely related to arsenic trioxide‐induced apoptosis in an acute myeloid leukemia (M2)‐derived cell line, NKM‐1. Leukemia 2003; 17: 2189–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Shimizu S, Yoshioka R, Hirose Y, Sugai S, Tachibana J, Konda S. Establishment of two interleukin 6 (B cell stimulatory factor 2/interferon beta 2)‐dependent human bone marrow‐derived myeloma cell lines. J Exp Med 1989; 169: 339–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nilsson K, Bennich H, Johansson SG, Ponten J. Established immunoglobulin producing myeloma (IgE) and lymphoblastoid (IgG) cell lines from an IgE myeloma patient. Clin Exp Immunol 1970; 7: 477–89. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Drexler H. The Leukemia‐Lymphoma Cell Line Factsbook. London: Academic Press, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mahmoud MS, Ishikawa H, Fujii R, Kawano MM. Induction of CD45 expression and proliferation in U‐266 myeloma cell line by interleukin‐6. Blood 1998; 92: 3887–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zhou Q, Yao Y, Ericson SG. The protein tyrosine phosphatase CD45 is required for interleukin 6 signaling in U266 myeloma cells. Int J Hematol 2004; 79: 63–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zhang XG, Gaillard JP, Robillard N et al. Reproducible obtaining of human myeloma cell lines as a model for tumor stem cell study in human multiple myeloma. Blood 1994; 83: 3654–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kitamura K, Minami Y, Yamamoto K et al. Involvement of CD95‐independent caspase 8 activation in arsenic trioxide‐induced apoptosis. Leukemia 2000; 14: 1743–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hideshima T, Mitsiades C, Akiyama M et al. Molecular mechanisms mediating antimyeloma activity of proteasome inhibitor PS‐341. Blood 2003; 101: 1530–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dai J, Weinberg RS, Waxman S, Jing Y. Malignant cells can be sensitized to undergo growth inhibition and apoptosis by arsenic trioxide through modulation of the glutathione redox system. Blood 1999; 93: 268–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Theodosiou A, Ashworth A. Differential effects of stress stimuli on a JNK‐inactivating phosphatase. Oncogene 2002; 21: 2387–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hideshima T, Chauhan D, Richardson P et al. NF‐kappa B as a therapeutic target in multiple myeloma. J Biol Chem 2002; 277: 16639–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kapahi P, Takahashi T, Natoli G et al. Inhibition of NF‐kappa B activation by arsenite through reaction with a critical cysteine in the activation loop of Ikappa B kinase. J Biol Chem 2000; 275: 36062–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Park WH, Seol JG, Kim ES et al. Arsenic trioxide‐mediated growth inhibition in MC/CAR myeloma cells via cell cycle arrest in association with induction of cyclin‐dependent kinase inhibitor, p21, and apoptosis. Cancer Res 2000; 60: 3065–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rousselot P, Labaume S, Marolleau JP et al. Arsenic trioxide and melarsoprol induce apoptosis in plasma cell lines and in plasma cells from myeloma patients. Cancer Res 1999; 59: 1041–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hayashi T, Hideshima T, Akiyama M et al. Arsenic trioxide inhibits growth of human multiple myeloma cells in the bone marrow microenvironment. Mol Cancer Ther 2002; 1: 851–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Deaglio S, Canella D, Baj G, Arnulfo A, Waxman S, Malavasi F. Evidence of an immunologic mechanism behind the therapeutical effects of arsenic trioxide (As(2)O(3) on myeloma cells. Leuk Res 2001; 25: 227–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Maeda H, Hori S, Nishitoh H et al. Tumor growth inhibition by arsenic trioxide (As2O3) in the orthotopic metastasis model of androgen‐independent prostate cancer. Cancer Res 2001; 61: 5432–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cavigelli M, Li WW, Lin A, Su B, Yoshioka K, Karin M. The tumor promoter arsenite stimulates AP‐1 activity by inhibiting a JNK phosphatase. Embo J 1996; 15: 6269–79. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]