Abstract

Unmethylated cytosine‐phosphorothioate‐guanine containing oligodeoxynucleotides (CpG‐ODN) is known as a ligand of toll‐like receptor 9 (TLR9), which selectively activates type‐1 immunity. We have already reported that the vaccination of tumor‐bearing mice with liposome‐CpG coencapsulated with model‐tumor antigen, ovalbumin (OVA) (CpG + OVA‐liposome) caused complete cure of the mice bearing OVA‐expressing EG‐7 lymphoma cells. However, the same therapy was not effective to eradicate Lewis lung carcinoma (LLC)‐OVA‐carcinoma. To overcome the refractoriness of LLC‐OVA, we tried the combination therapy of radiation with CpG‐based tumor vaccination. When LLC‐OVA‐carcinoma intradermally (i.d.) injected into C57BL/6 became palpable (7–8 mm), the mice were irradiated twice with a dose of 14 Gy at intervals of 24 h. After the second radiation, CpG + OVA‐liposome was i.d. administered near the draining lymph node (DLN) of the tumor mass. The tumor growth of mice treated with radiation plus CpG + OVA‐liposome was greatly inhibited and approximately 60% of mice treated were completely cured. Moreover, the combined therapy with radiation and CpG + OVA‐liposome allowed the augmented induction of OVA‐tetramer+ LLC‐OVA‐specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) in DLN of tumor‐bearing mice. These results indicate that the combined therapy of radiation with CpG‐based tumor vaccine is a useful strategy to eradicate intractable carcinoma. (Cancer Sci 2009; 100: 934–939)

Radiation therapy using advanced technology has been established as an excellent local treatment for carcinomas.( 1 , 2 ) However, all the patients treated with radiation therapy have not always been cured from tumor because some tumors are resistant to ionization. To overcome this problem, combined immunotherapy with radiation has been tried by many clinical investigators, although an ideal therapeutic strategy has not yet been established.( 3 ) Tumor‐specific immunotherapy has been tried since Boon et al. demonstrated the presence of tumor‐rejection antigen.( 4 , 5 ) In order to induce tumor‐specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL) in tumor‐bearing states, many investigators have attempted to vaccinate the tumor‐bearing host with major histocompatability complex (MHC) class I‐binding tumor antigen peptide or tumor antigen peptide‐pulsed dendritic cells (DC).( 6 , 7 , 8 ) However because of strong immunosuppressive and escape mechanisms, it has been difficult to induce fully activated tumor‐specific CTL.( 9 , 10 ) As one of the strategies to overcome immunosuppressive states, several tumor immunologists have been exploring combining chemotherapy or radiation therapy with immunotherapy.( 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 )

We have developed a superior tumor immunotherapy using tumor‐specific T‐helper type 1 (Th1) cell plus tumor antigen or liposome‐CpG (cytosine‐phosphorothioate‐guanine) encapsulated with tumor antigen to introduce Th1‐dominant immunity in tumor‐bearing hosts, which is critically important to overcome the immunosuppression and to induce fully activated tumor‐specific CTL.( 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 ) In our previous work on CpG‐based tumor vaccine therapy, we succeeded in eradication of well established MHC class II−/– tumor mass of lymphoma by injection of CpG‐ODN (oligodeoxynucleotide) and OVA (ovalbumin) protein coencapsulate in liposome (CpG + OVA‐lipo) near tumor draining lymph node (DLN).( 28 ) However, as most human tumors are carcinomas, but not lymphomas, we have considered that it is of great importance to develop a new theraputic strategy to eradicate mouse carcinoma to apply our basic study to clinical practice.

Here, we tried CpG‐based tumor vaccine therapy to OVA‐expressing Lewis lung carcinoma (LLC‐OVA). In contrast to cases of lymphoma, LLC‐OVA carcinoma was resistant to CpG‐based tumor vaccine therapy alone. Therefore, we next challenged the combined therapy of radiation with CpG‐based tumor vaccine therapy to induce complete cure of carcinoma‐bearing mice. It has remained unclear how irradiation exhibits antitumor responses. Some groups reported that the elevated levels of tissue‐derived tumor growth factor (TGF)‐β( 31 ) and interleukin (IL)‐10( 32 ) by irradiation diminish the activity of T‐cell immunity specific for tumor antigens.( 33 ) Others reported that irradiation creates an inflammatory setting in vivo via induction of apoptosis, duration of tumor antigen, up‐regulation of MHC and costimulatory molecules and release of the high‐mobility‐group box 1 (HMGB‐1) recognized by toll‐like receptor (TLR)4, thereby modulated the tumor environment for eliciting a potent antitumor immunity.( 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 ) In the present work, we demonstrated that the combined therapy with radiation and CpG‐based tumor vaccine therapy is a powerful strategy to induce complete rejection of LLC‐OVA tumor mass through augmented induction of tumor‐specific CTL in tumor‐bearing mice.

Materials and Methods

Mice. C57BL/6 and BALB/c mice were obtained from Charles River Japan (Yokohama, Japan). All mice were female and were used at 6–8 weeks of age.

Antigen, mAb and tetramer. OVA protein was purchased from Sigma Aldrich Japan (Tokyo, Japan). Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)‐CD8 monoclonal antibody (mAb) was purchased from PharMingen (San Diego, CA, USA). H‐2Kb OVA tetramer‐SIINFEKL‐PE (OVA tetramer) were purchased from MBL (Nagoya, Japan). LLC‐OVA was kindly donated by Dr K Yamazaki (Hokkaido University, Sapporo, Japan).

CpG‐ODN and liposomes. Phosphorothioate‐stabilized CpG‐ODN 1668 (5′‐TCCATGACGTTCCTGATGCT‐3′) was synthesized by Hokkaido System Science (Sapporo, Japan). Cationic liposomes were purchased from NOP Corporation (Tokyo, Japan).

Antibody staining and flow cytometry. For analysis of OVA‐specific CTL frequencies, lymphocytes from the DLN and tumor tissue were stained with FITC‐conjugated anti‐CD8 mAb and PE‐conjugated OVA‐tetramer. Data were acquired on a Becton Dickinson FACSCalibur (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). Data were analyzed using CellQuest software (Becton Dickinson).

Local irradiation and tumor‐immunotherapy model. OVA‐expressing LLC‐OVA cells (2 × 106) were intradermally (i.d.) inoculated into C57BL/6 mice. When the tumor mass became large (8–9 mm in diameter), the tumor‐bearing mice were immobilized in a plastic syringe with a hole from which we can pull out the target tumor, and put the mouse under a 4 mm‐thick lead shield with a 10 mm × 10 mm hole. The mouse was locally irradiated twice with a dose of 14 Gy at intervals of 24 h (X‐ray, Toshiba, Tokyo, Japan, 10 Gy/min). After the second radiation the tumor‐bearing mice were treated with saline, liposome‐encapsulated OVA protein (200 µg), liposome‐encapsulated CpG‐ODN (50 µg) or liposome‐encapsulated CpG‐ODN plus OVA protein. The antitumor activity was determined by measuring the tumor size in perpendicular diameters. Tumor volume was calculated by the following formula: tumor volume = 0.4 × length (mm) × [width (mm)]2. Tumor‐bearing mice that survived for >60 days after therapy were considered completely cured.

Cytotoxicity assay. The cytotoxicity mediated by tumor‐specific CTL was measured by 6 h‐51Cr‐release assay as described previously.( 39 ) Tumor‐specific cytotoxicity was determined using LLC‐OVA cells as target cells. Parental LLC cells were used as control target cells. To confirm the antigen‐specificity of H‐2Kb‐restricted CTL, 51Cr‐labeled target cells were incubated with CD8+ CTL pretreated with OVA‐tetramer, which can block the recognition of H‐2Kb‐restricted target peptide (OVA257‐264) recognition by CTL, termed tetramer‐blocking assay.( 40 ) The percent cytotoxicity was calculated as described previously.( 39 )

Statistical analyses. All experiments were repeated at least three times. Mean values and standard deviation (SD) were calculated for data from representative experiments and are shown in the figures. Significant differences in the results were determined by Student's t‐test. P < 0.05 was considered as significant in the present experiments.

Results

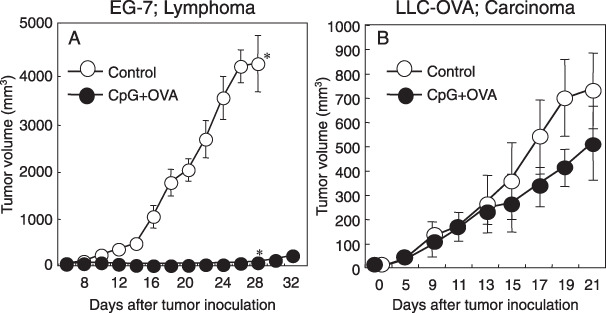

CpG tumor vaccine therapy induced the eradication of an established tumor mass of lymphoma, but not carcinoma. In the previous paper, we already developed CpG‐based tumor vaccine therapy, in which tumor‐bearing mice were vaccinated with CpG‐ODN and tumor antigen (OVA) coencapsulated in liposome (CpG + OVA‐liposome).( 28 ) Here we tested whether CpG‐based tumor vaccine therapy could be applied to carcinoma‐bearing mice as well as lymphoma‐bearing mice. C57BL/6 mice were i.d. inoculated with OVA‐expressing EG‐7 tumor cells. When the tumor mass became palpable (7–8 mm), the tumor‐bearing mice were treated by i.d. injection of CpG + OVA‐liposome near the DLN of the tumor. As shown in Fig. 1(A), vaccination of tumor‐bearing mice with CpG + OVA‐liposome caused a great inhibition of the established tumor mass in coincidence with our previous result.( 28 ) Since most human cancers are identified as carcinomas, we next investigated whether CpG‐based tumor vaccine therapy exhibited therapeutic efficacy to carcinomas. To examine this, OVA‐expressing LLC‐OVA carcinoma was inoculated into C57BL/6 mice and the same therapy was performed when the tumor mass became palpable. As shown in Fig. 1(B), LLC‐OVA tumor‐bearing mice were refractory to CpG‐based tumor vaccine therapy, although a slight tumor‐growth inhibition was observed.

Figure 1.

Cytosine‐phosphorothioate‐guanine (CpG) tumor vaccine therapy induced the eradication of an established tumor mass of lymphoma, but not tumor mass of carcinoma. EG‐7 cells (2 × 106; A) or Lewis lung carcinoma – ovalbumin (LLC‐OVA) (2 × 106; B) were intra‐dermally (i.d.) inoculated into C57BL/6 mice. When the tumor mass became palpable (7–8 mm), the tumor‐bearing mice were injected i.d. near the draining lymph node (DLN) with saline ( in A and B), or (CpG + OVA)‐liposomes (

in A and B), or (CpG + OVA)‐liposomes ( in A and B). The antitumor effect was determined by measuring the tumor size in perpendicular diameters. Tumor volume was calculated as described in Methods. The bars reveal mean ± SD of five mice in each experimental group. Asterisk means significant difference between CpG + OVA‐treated group and untreated‐control group 28 days after tumor inoculation (P < 0.05). Similar results were obtained in three separate experiments.

in A and B). The antitumor effect was determined by measuring the tumor size in perpendicular diameters. Tumor volume was calculated as described in Methods. The bars reveal mean ± SD of five mice in each experimental group. Asterisk means significant difference between CpG + OVA‐treated group and untreated‐control group 28 days after tumor inoculation (P < 0.05). Similar results were obtained in three separate experiments.

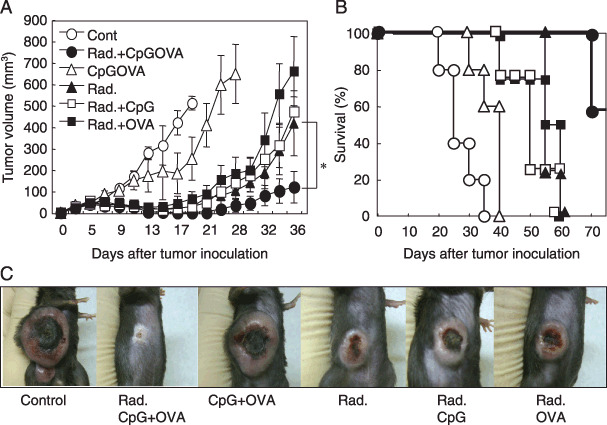

Combined therapy of local irradiation with CpG‐based tumor vaccine therapy induced the eradication of established LLC‐OVA. Since LLC‐OVA was refractory to CpG‐based tumor vaccine therapy, we developed a combination therapy with local tumor irradiation. When the LLC‐OVA tumor mass reached palpable size, it was irradiated twice with a dose of 14 Gy at intervals of 24 h. After the second radiation therapy, CpG + OVA‐liposome was i.d. administered near the DLN of the tumor. As shown in Fig. 2(A–C), the growth of tumors of the mice treated with radiation plus CpG + OVA‐liposome was significantly inhibited and about 60% of mice were completely cured from their tumors. However, the mice treated with other therapeutic protocols (radiation alone, CpG + OVA‐liposome alone, radiation plus CpG or radiation plus OVA) could not induce complete cure although tumor growth was slightly inhibited (Fig. 2c). These results indicated that combined therapy of local irradiation and CpG‐based tumor vaccine therapy was effective to eradicate carcinoma, which was resistant to radiation therapy alone or CpG‐based tumor vaccine therapy alone.

Figure 2.

Combined therapy of local irradiation with (CpG) tumor vaccine therapy induced significant eradication of established Lewis lung carcinoma – ovalbumin (LLC‐OVA). LLC‐OVA (2 × 106) were intra‐dermally (i.d.) inoculated into C57BL/6 mice. When the tumor mass became palpable (7–8 mm), the tumor‐bearing mice were irradiated twice by a single dose of 14 Gy at 24 intervals ( ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  in A and B). After the second irradiation, tumor‐bearing mice were injected i.d. near the draining lymph node (DLN) with saline (

in A and B). After the second irradiation, tumor‐bearing mice were injected i.d. near the draining lymph node (DLN) with saline ( in A and B) (CpG + OVA)‐liposomes (

in A and B) (CpG + OVA)‐liposomes ( ,

,  in A and B), CpG‐liposomes (

in A and B), CpG‐liposomes ( in A and B), and OVA‐liposomes (

in A and B), and OVA‐liposomes ( in A and B). The anti‐tumor effect was determined by measuring the tumor volume (A) and by assessing the survival ratio (B). The photos in (C) exhibited the representative mouse on each group 25 days after the tumor inoculation. Tumor volume was calculated as described in Methods. The bars reveal mean ± SD of five mice in each experimental group. Asterisk means significant difference from radiation‐treated group and radiation + CpGOVA‐treated group (P < 0.05). Similar results were obtained in three separate experiments.

in A and B). The anti‐tumor effect was determined by measuring the tumor volume (A) and by assessing the survival ratio (B). The photos in (C) exhibited the representative mouse on each group 25 days after the tumor inoculation. Tumor volume was calculated as described in Methods. The bars reveal mean ± SD of five mice in each experimental group. Asterisk means significant difference from radiation‐treated group and radiation + CpGOVA‐treated group (P < 0.05). Similar results were obtained in three separate experiments.

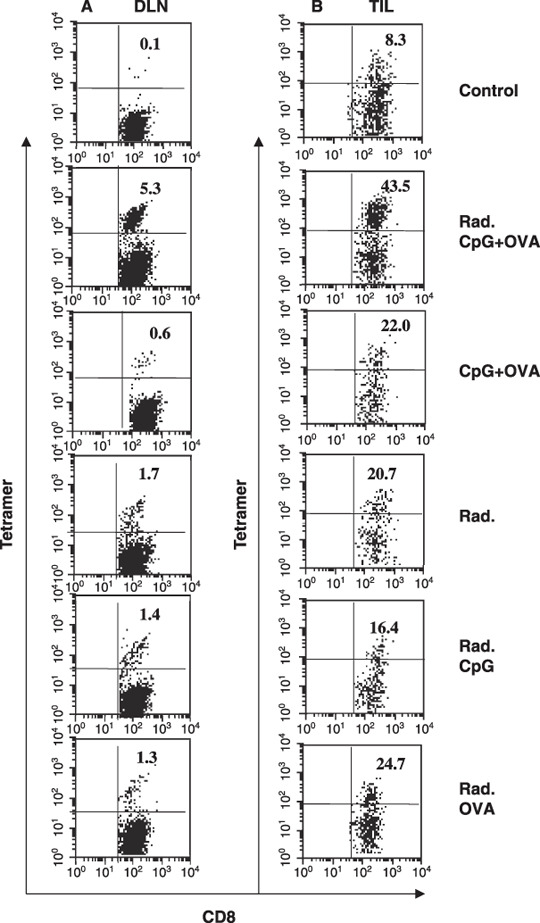

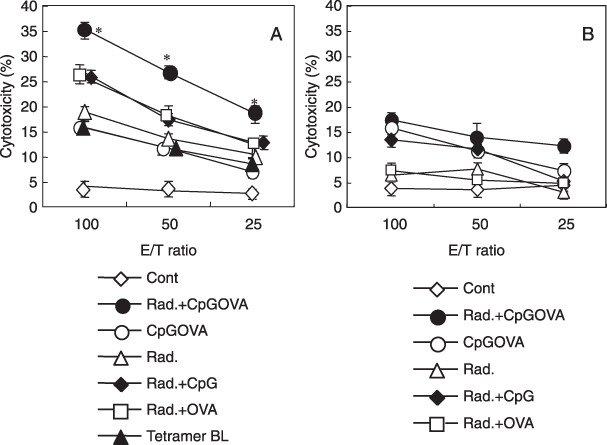

Tumor‐specific CTLs were synergistically induced in DLN and tumor tissue during the combined therapy of irradiation with CpG‐based tumor vaccine. We next investigated the frequency of tumor‐specific CTL in DLN and tumor tissue in tumor‐bearing mice 6 days after vaccination. Lymphocytes were prepared from tumor DLN or tumor mass to examine the generation of tumor antigen (OVA)‐specific CTL by staining with OVA/H‐2Kb‐tetramers. In tumor‐bearing mice treated with local radiation and vaccination with CpG + OVA‐liposome, tetramer+ CD8+ CTL greatly increased in DLN (5.3%) and tumor tissue (43.5%), as compared with mice treated with radiation alone, CpG + OVA‐liposome alone, radiation plus CpG or radiation plus OVA (Fig. 3). We also demonstrated that the unfractionated lymphocytes prepared from DLN exhibited a specific cytotoxicity against OVA‐gene transfected LLC‐OVA carcinoma but not their parental LLC carcinoma cells (Fig. 4). Moreover, as shown in Fig. 4(A), the cytotoxicity mediated by lymphocytes derived from DLN of mice treated with the combined therapy with radiation and CpG‐based vaccination was strongly blocked by OVA/H‐2Kb‐tetramer in tetramer‐blocking assay, which was previously developed by us to ensure whether CTL specifically kills target cells by recognizing tumor‐derived MHC‐class I‐binding peptide.( 40 ) These results indicated that combination therapy of local irradiation and vaccination with CpG + OVA‐liposome provided an efficient strategy to promote the generation of OVA/H‐2Kb‐tetramer+ CD8+ CTL, which recognized H‐2Kb‐binding OVA257–264 peptide antigen and exhibited a strong cytotoxicity against LLC‐OVA, from endogenously circulated naïve CD8+ T cells in tumor‐bearing mice.

Figure 3.

Synergistic induction of tumor‐specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) in tumor‐bearing mice by irradiation combined with vaccination of CpG plus ovalbumin (CpG + OVA)‐liposomes. Six days after treatment with saline, radiation plus (CpG + OVA)‐liposomes, (CpG + OVA)‐liposomes, radiation, radiation plus CpG‐liposomes and radiation plus OVA‐liposomes, lymphocytes were prepared from the tumor draining lymph node (DLN) (A) and the tumor mass (B). OVA‐specific CTL frequency in the DLN (A) and tumor‐infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL) (B) were examined by flow cytometry as described in Methods. The ratio of tetramer+ CTLs was analyzed among CD8+ T cell‐gated population. The numbers in the top right quadrant represent the percentage of tetramer+ cells among the total CD8+ cells. Similar results were obtained in three different experiments.

Figure 4.

Tumor‐specific cytotoxicity of tumor draining lymph node (DLN) prepared from combined therapy was mediated by ovalbumin (OVA)‐tetramer+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs). The total lymphocyte population isolated from the DLN of tumor‐bearing mice treated with saline ( ), radiation plus (CpG + OVA)‐liposomes (

), radiation plus (CpG + OVA)‐liposomes ( ), (CpG + OVA)‐liposomes (

), (CpG + OVA)‐liposomes ( ), radiation (

), radiation ( ) radiation plus CpG‐liposomes (

) radiation plus CpG‐liposomes ( ) and radiation plus OVA‐liposomes (

) and radiation plus OVA‐liposomes ( ) against LLC‐OVA cells (A) or parental LLC cells (B) was examined in a 6‐h 51Cr‐release assay. Then, to determine the specificity of cytolysis, cytotoxicity was examined after lymphocytes were incubated with OVA/H‐2Kb‐tetramer (

) against LLC‐OVA cells (A) or parental LLC cells (B) was examined in a 6‐h 51Cr‐release assay. Then, to determine the specificity of cytolysis, cytotoxicity was examined after lymphocytes were incubated with OVA/H‐2Kb‐tetramer ( ) against LLC‐OVA (A). Asterisk means significant difference from radiation + CpG‐treated group and radiation + CpGOVA‐treated group (P < 0.05). Similar results were obtained in three different experiments.

) against LLC‐OVA (A). Asterisk means significant difference from radiation + CpG‐treated group and radiation + CpGOVA‐treated group (P < 0.05). Similar results were obtained in three different experiments.

Discussion

Here, we demonstrated that LLC‐OVA carcinoma cells are refractory to CpG‐based tumor vaccine therapy in contrast to EG‐7 lymphoma cells (Fig. 1). The possible explanations for the resistance of LLC‐OVA to immunotherapy might be that: (i) the expression of MHC class I on carcinoma was much lower than T lymphoma; and (ii) carcinoma cells produce high levels of TGF‐β, which accelerate the generation of immunosuppressive regulatory cells, compared with lymphoma cells (data not shown). In our previous work of the CpG‐based tumor vaccine model, we used curable EG‐7 to explore the potential ability of CpG as a tumor‐immunotherapeutic adjuvant.( 28 ) However in clinical practice, most human solid tumors are carcinomas, which may be intractable with immunotherapy alone.

Radiation therapy often cures patients with carcinomas but not always. In order to induce complete destruction of established carcinoma, we tested to combine radiation therapy with CpG‐based tumor vaccine. Radiation therapy is increasing in importance as a curative local cancer treatment with an estimated half of all newly diagnosed cancer patients receiving radiotherapy at some point in the course of their disease.( 41 ) Therefore, the combination with radiotherapy would provide many opportunities to apply CpG‐based tumor vaccine therapy to tumor patients. Although other groups reported the combination therapy of radiation and CpG‐ODN, they used CpG‐ODN alone without tumor antigen.( 42 , 43 ) On the contrary, in CpG‐based tumor vaccine therapy we developed, tumor antigen was vaccinated with CpG‐ODN as a strong adjuvant, resulting in the induction of tumor‐specific CTL. As shown in Fig. 2, in the group treated with CpG‐based tumor vaccine therapy and radiation therapy, the LLC‐OVA tumor growth was greatly inhibited and approximately 60% of the mice were completely cured. Since one of the most important monitoring markers of tumor immunotherapy is the generation of tumor‐specific CTL, we determined the frequency of OVA‐tetramer+ CTL in tumor‐bearing mice treated with combined therapy. Notably, the generation of tumor‐specific CTL was significantly enhanced in DLN of LLC‐OVA‐bearing mice during treatment with the combined therapy (Fig. 3). It might be estimated how this combination therapy augmented the generation of tumor‐specific CTL. Five days after the irradiation, the ratio of CD11c+ cells in the tumor site was significantly increased from 6.4% to 20.7% compared with the untreated group in our model (data not shown). Additionally, Teitz‐Tennenbaum et al. reported that tumor irradiation facilitated homing of DCs to DLN by down‐regulating CCL21 expression in the tumor mass.( 44 ) Furthermore, in our previous report,( 21 ) we demonstrated that tumor‐antigen processed antigen presenting gel (APC) in tumor tissue migrated into DLN and provoked the generation of OVA‐tetramer+ CTL in DLN. Thus it might be possible to consider that radiation therapy supports the tetramer+ CTL generation of CpG‐based tumor vaccine therapy through the promoted migration of APC into DLN. HMGB‐1 protein from apoptotic tumor mass recognized by TLR4 might also be involved in activation of APC.( 37 , 38 )

Since tumor‐specific CTLs are essential for inducing complete cure in CpG‐based tumor vaccine therapy,( 28 ) we next investigate whether the induced tumor‐specific CTL actually kills LLC‐OVA carcinoma in an antigen‐specific manner. As shown in Fig. 4(A), lymphocytes derived from DLN of tumor‐bearing mice exhibit model tumor antigen (OVA)‐specific cytotoxicity and its activity is blocked by tetramer‐blocking assay. Thus, we conclude that the combined therapy with radiation and CpG‐based tumor vaccination therapy is superior strategy to induce OVA‐tetramer+ CTL, which specifically recognize the MHC class I‐binding tumor‐antigenic peptide, from endogenous naïve CD8+ T cells in tumor‐bearing mice.

In a previous paper,( 28 ) we showed that CpG‐based tumor vaccine therapy exhibited both lymphatic and systemic antitumor effect and prolonged survival of tumor‐bearing mice. Therefore, it may be possible to prevent tumor metastasis by combination therapy through inducing enhanced tumor‐specific CTL. Thus, the combination therapy of radiation and immunotherapy may be more important since it has become possible to give radiation doses sufficient to nearly eradicate local carcinomas with advanced technology.( 1 , 2 ) We are now planning to develop a therapeutic model of tumor metastasis by the combination of radiation therapy with immunotherapy. We are also investigating the detailed mechanism of how an irradiation treatment potentiates the efficacy of immunotherapy against tumor‐bearing hosts.

In conclusion, the combined therapy of radiation with CpG‐based tumor vaccine therapy exhibits superior antitumor activity to eradicate LLC‐OVA carcinoma tissue compared with radiotherapy alone or CpG‐based tumor vaccine therapy alone in carcinoma‐bearing mice. Radiation therapy accelerates the induction of tumor‐specific CTL in tumor‐bearing mice. We believe the combined therapy may be a powerful strategy to eradicate radio‐ and immune‐resistant carcinomas and will be applicable to human cancer therapy.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Grant‐in‐Aid for National Project ‘Knowledge Cluster Initiative’ (2nd stage, ‘Sapporo Biocluster Bio‐S’) from the Ministry of Education Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology, a Grant‐in‐Aid for Scientific Research on priority Areas, a Grant‐in‐Aid for Immunological Surveillance and its Regulation and Special Coordination Funds for Promoting Science and Technology from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, the Japanese Government.

Note: Kenji Chamoto and Tsuguhide Takeshima were equally contributed in this work.

References

- 1. Shirato H, Shimizu S, Kitamura K, Onimaru R. Organ motion in image‐guided radiotherapy: lessons from real‐time tumor‐tracking radiotherapy. Int J Clin Oncol 2007; 12: 8–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nishioka T, Shirato H, Kagei K, Fukuda S, Hashimoto S, Ohmori K. Three‐dimensional small‐Volume irradiation for residual or recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2000; 48: 495–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Argiris A, Karamouzis MV, Raben D, Ferris RL. Head and neck cancer. Lancet 2008; 371: 1695–709. Review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. van der Bruggen P, Traversari C, Chomez P et al . A gene encoding an antigen recognized by cytolytic T lymphocytes on a human melanoma. Science 1991; 254: 1643–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Boon T, Cerottini JC, Van den Eynde B, van der Bruggen P, Van Pel A. Tumor antigens recognized by T lymphocytes. Annu Rev Immunol 1994; 12: 337–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ribas A, Butterfield LH, Glaspy JA, Economou JS. Current developments in cancer vaccines and cellular immunotherapy. J Clin Oncol 2003; 21: 2415–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Coulie PG, van der Bruggen P. T‐cell responses of vaccinated cancer patients. Curr Opin Immunol 2003; 15: 131–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rosenberg SA, Yang JC, Restifo NP. Cancer immunotherapy: moving beyond current vaccines. Nat Med 2004; 10: 909–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rabinovich GA, Gabrilovich D, Sotomayor EM. Immunosuppressive Strategies that are mediated by Tumor Cells. Annu Rev Immunol 2007; 25: 267–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Oizumi S, Deyev V, Yamazaki K et al . Surmounting tumor‐induced immune suppression by frequent vaccination or immunization in the absence of B cells. J Immunother 2008; 31: 394–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yu E, Gabrilovich N, Gabrilovich DI. Combination of γ‐irradiation and dendritic cell administraion induces a potent antitumor response in tumor‐bearing mice: approach to treatment of advanced stage cancer. Int J Cancer 2001; 94: 825–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Teitz‐Tennenbaum S, Li Q, Rynkiewicz S, Ito F, Davis MA, McGinn CJ, Chang AE. Radiotherapy potentiates the therapeutic efficacy of intratumoral dendritic cell administration. Cancer Res 2003; 63: 8466–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ganss R, Ryschich E, Klar E, Arnold B, Hammerling GJ. Combination of T‐cell therapy and trigger of inflammation induces remodeling of the vasculature and tumor eradication. Cancer Res 2002; 62: 1462–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cao ZA, Daniel D, Hanahan D. Sub‐lethal radiation enhances anti‐tumor immunotherapy in a transgenic mouse model of pancreatic cancer. BMC Cancer 2002; 2: 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dudley ME, Wunderlich JR, Robbins PF et al . Cancer regression and autoimmunity in patients after clonal repopulation with antitumor lymphocytes. Science 2002; 25: 850–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Milas L, Mason KA, Ariga H et al . CpG oligodeoxynucleotide enhances tumor response to radiation. Cancer Res 2004; 64: 5074–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mason KA, Ariga H, Neal R et al . Targeting toll‐like receptor 9 with CpG oligodeoxynucleotides enhances tumor response to fractionated radiotherapy. Clin Cancer Res 2005; 11: 361–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nishimura T, Iwakabe K, Sekimoto M et al . Distinct role of antigen‐specific T helper type 1 (Th1) and Th2 cells in tumor eradication in vivo. J Exp Med 1999; 190: 617–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nishimura T, Nakui M, Sato M et al . The critical role of Th1‐dominant immunity in tumor immunology. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2000; 46: S52–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chamoto K, Tsuji T, Funamoto H et al . Potentiation of tumor eradication by adoptive immunotherapy with T‐cell receptor gene‐transduced T‐helper type 1 cells. Cancer Res 2004; 64: 386–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chamoto K, Wakita D, Narita Y et al . An essential role of antigen‐presenting cell/T‐helper type 1 cell–cell interactions in draining lymph node during complete eradication of class II‐negative tumor tissue by T‐helper type 1 cell therapy. Cancer Res 2006; 66: 1809–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zhang Y, Wakita D, Chamoto K et al . Th1 cell adjuvant therapy combined with tumor vaccination: a novel strategy for promoting CTL responses while avoiding the accumulation of Tregs. Int Immunol 2007; 19: 151–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chamoto K, Kosaka A, Tsuji T et al . Critical role of the Th1/Tc1 circuit for the generation of tumor‐specific CTL during tumor eradication in vivo by Th1‐cell therapy. Cancer Sci 2003; 94: 924–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ikeda H, Chamoto K, Tsuji T et al . The critical role of type‐1 innate and acquired immunity in tumor immunotherapy. Cancer Sci 2004; 95: 697–703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Suzuki Y, Wakita D, Chamoto K et al . Liposome‐encapsulated CpG oligodeoxynucleotides as a potent adjuvant for inducing type 1 innate immunity. Cancer Res 2004; 64: 8754–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gyobu H, Tsuji T, Suzuki Y et al . Generation and targeting of human tumor‐specific Tc1 and Th1 cells transduced with a lentivirus containing a chimeric immunoglobulin T‐cell receptor. Cancer Res 2004; 64: 1490–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tsuji T, Yasukawa M, Matsuzaki J et al . Generation of tumor‐specific, HLA class I‐restricted human Th1 and Tc1 cells by cell engineering with tumor peptide‐specific T‐cell receptor genes. Blood 2005; 106: 470–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wakita D, Chamoto K, Zhang Z et al . An indispensable role of type‐1 IFNs for inducing CTL‐mediated complete eradication of established tumor tissue by CpG‐liposome co‐encapsulated with model tumor antigen. Int Immunol 2006; 18: 425–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kobayashi H, Celis E. Peptide epitope identification for tumor‐reactive CD4 T cells. Curr Opin Immunol 2008; 20: 221–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Trinchieri G. Interleukin‐12 and the regulation of innate resistance and adaptive immunity. Nat Rev Immunol 2003; 3: 133–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Canney PA, Dean S. Transforming growth factor beta: a promoter of late connective tissue injury following radiotherapy? Br J Radiol 1990; 63: 620–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Broski AP, Halloran PF. Tissue distribution of IL‐10 mRNA in normal mice. Evidence that a component of IL‐10 expression is T and B cell‐independent and increased by irradiation. Transplantation 1994; 27: 582–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Horwitz DA, Zheng SG, Gray JD. The role of the combination of IL‐2 and TGF‐β or IL‐10 in the generation and function of CD4+ CD25+ and CD8+ regulatory T cell subsets. J Leuko Biol 2003; 74: 471–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Friedman EJ. Immune modulation by ionizing radiation and its implications for cancer immunotherapy. Curr Pharm 2002; 8: 1765–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Garnett CT, Palena C, Chakarborty M, Tsang KY, Schlom J, Hodge JW. Sublethal irradiation of human tumor cells modulate phenotype resulting in enhanced killing by cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Cancer Res 2004; 64: 7985–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Reits EA, Hodge JW, Herberts CA et al . Radiation modulates the peptide repertoire, enhances MHC class I expression, and induces successful antitumor immunotherapy. J Exp Med 2006; 15: 1259–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Zhang B, Bowerman NA, Salama JK et al . Induced sensitization of tumor stroma leads to eradication of established cancer by T cells. J Exp Med 2007; 204: 49–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Apetoh L, Ghiringhelli F, Tesniere A et al . Toll‐like receptor 4‐dependent contribution of the immune system to anticancer chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Nat Med 2007; 13: 1050–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Nishimura T, Burakoff SJ, Herrmann SH. Protein kinase C required for cytotoxic T lymphocyte triggering. J Immunol 1987; 139: 2888–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Yokouchi H, Chamoto K, Wakita D et al . Tetramer‐blocking assay for defining antigen‐specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes using peptide‐MHC tetramer. Cancer Sci 2006; 97: 148–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ringborg U, Bergqvist D, Brorsson B et al . The Swedish Council on Technology Assessment in Health Care (SBU) systematic overview of radiotherapy for cancer including a prospective survey of radiotherapy practice in Sweden 2001 – summary and conclusions. Acta Oncol 2003; 42: 357–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Mason KA, Neal R, Hunter N, Ariga H, Ang K, Milas L. CpG oligodeoxynucleotides are potent enhancers of radio‐ and chemoresponses of murine tumors. Radiotheroncol 2006; 80: 192–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Rayburn ER, Wang W, Zhang R, Wang H. Experimental therapy for colon cancer. anti‐cancer effects of TLR9 agonism, combination with other therapeutic modalities, and dependence upon p53. Int J Oncol 2007; 30: 1511–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Teitz‐Tennenbaum S, Li Q, Okuyama R, Davis MA, Sun R, Whitfield J, Knibbs RN, Stoolman LM, Chang AE. Mechanisms involved in radiation enhancement of intratumoral dendritic cell therapy. J Immunother 2008; 31: 345–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]