Abstract

The purpose of this study was to establish a standard histological classification for intra‐operative histological examination of ductal resection margins in cholangiocarcinoma to distinguish between epithelial and intramural lesions and to clarify correlations between the new classification and clinical outcomes. Intra‐operative diagnosis of ductal margins was performed for 357 stumps from 216 patients undergoing surgical resection of cholangiocarcinoma at the National Cancer Center, Japan. Three expert pathologists reviewed the materials and established a histological classification defined by grade of atypia. The new classification comprised four categories: ‘insufficient’, insufficient for diagnosis due to distortion of specimen; ‘negative for malignancy’, no atypia suggestive of neoplasia; ‘undetermined lesion’, specimen showing either cellular or structural atypia; and ‘positive for malignancy’, specimen showing both cellular and structural atypia. Each category was defined to distinguish between epithelial and intramural lesions. Validity and reproducibility of the proposed classification were found to be moderate to substantial. Multivariate analyses using the clinicopathological factors identified to be associated with overall survival by univariate analyses indicated that patients diagnosed with ‘positive for malignancy’ in intramural lesions of the proximal margin displayed significant poor prognosis. Meanwhile, in patients diagnosed with ‘positive for malignancy’ or ‘undetermined lesion’ in epithelial lesions of the proximal margin, no difference in overall survival was apparent compared to patients diagnosed with ‘negative for malignancy’. We propose new histological classification for intra‐operative histological examination of ductal resection margins in cholangiocarcinoma that shows a correlation with patients’ prognosis and should facilitate the determination of ductal resection margin status for cholangiocarcinoma. (Cancer Sci 2009; 100: 255–260)

- Abbreviations: INS

insufficient

- NM

negative for malignancy

- UDL

undetermined lesion

- PM

positive for malignancy

- BilIN

biliary intraepithelial neoplasia

- HR

hazard ratio

- CI

confidence interval

Surgical resection with negative surgical margins offers patients with resectable cholangiocarcinoma the only chance for cure and long‐term survival. Surgical resection margin status is a critical prognostic factor, and the prognosis for patients with positive ductal margins has generally been considered as poor.( 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 ) More extensive surgery to obtain negative ductal margins increases the risk of postoperative morbidity–mortality, whereas less extensive surgery increases the risk of positive ductal margins. Balancing these conflicting considerations is thus difficult. Although preoperative diagnosis for extension of cholangiocarcinoma has improved in recent years, intra‐operative frozen section remains the only method for confirming microscopic involvement of the ductal margins. However, determination of positive or negative status is sometimes difficult.( 7 , 8 ) Lining epithelia of the bile duct in obstructive jaundice are known to display atypical lesions related to the development of cholangitis. Both carcinoma in situ and carcinoma showing intra‐epithelial spread are difficult to differentiate from atypical epithelia arising in association with cholangitis. Similarly, in intramural lesions of the bile duct, proper glands with atypical changes due to cholangitis are sometimes difficult to distinguish from invasive ductal lesions. Moreover, distortions induced by drainage tubes and operative manipulations can complicate the diagnosis. Widely disparate histological grades ranging from reactive atypia to carcinoma can be assigned to lesions by different pathologists. Furthermore, results from different researchers have been hard to compare due to the absence of standard diagnostic classifications for these lesions.

Wakai et al.( 9 ) demonstrated that residual carcinoma in situ differs prognostically from residual invasive ductal disease in patients with extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, as the progression from carcinoma in situ to invasive carcinoma at ductal resection margins may require several years. When ductal margin status is positive for malignancy on examination of frozen sections, discriminating between carcinoma in situ and invasive carcinoma is crucial.

Given this background, the purpose of this study was to establish a standard histological classification for intra‐operative histological examination of ductal resection margins in cholangiocarcinoma, to distinguish between epithelial and intramural lesions and to clarify correlations between the new classification and clinical outcomes.

Materials and Methods

Study design. A retrospective study was conducted to establish histological classifications. Expert pathologists reviewed a large number of specimens of ductal resection margins and then established a new histological classification. Next, to examine utility of this new classification, validity and reproducibility were tested by independent observers. Finally, correlations between the results of margin status and clinical outcomes in patients were analyzed.

Patient selection. Between 1990 and 2003, a total of 216 patients underwent surgical resection for cholangiocarcinoma with intra‐operative histological examination of the ductal margins at the National Cancer Center, Japan (Central Hospital, n = 171; East Hospital, n = 45). Carcinoma of the ampulla of Vater or gallbladder was not included. Patients comprised 149 men and 67 women with a mean age of 64 years (range, 41–88 years). Predominant lesion sites were the distal bile duct (n = 66), hilar bile duct (n = 91), and intrahepatic bile duct (n = 59). The surgical procedure consisted of pancreatoduodenectomy (n = 50), hepatectomy with bile duct resection (n = 147), extrahepatic bile duct resection (n = 14), or hepatopancreatoduodenectomy (n = 5).

We routinely use intra‐operative frozen sections to assess remnant ductal stumps. In cases of hepatic resection or extrahepatic bile duct resection, proximal and distal margins were taken for intra‐operative diagnosis. In cases with pancreatoduodenectomy, only proximal margins were examined. When multiple proximal margins were present, each margin was examined. When the first cut end was positive, additional resection of the marginal bile duct was performed to the maximum extent possible. A total of 357 stumps were examined for the 216 patients, with 230 specimens taken from proximal ductal margins and 127 specimens taken from distal ductal margins. All identifiers were removed from the slides and each slide was assigned a unique number from 1 to 357.

Frozen sections represent true surgical margins, but involve problems such as distortion of the specimen. Histological classification requires high‐quality specimens, so the present study used formalin‐fixed sections from frozen tissue samples.

Establishment of a new histological classification. Three expert pathologists (AY, TH and HO) participated in this study. For the first step, a slide‐set of materials was sent to each pathologist. Ductal lesions submitted for review were then classified using the individual criteria of the pathologist for distinction between epithelial and intramural lesions. Bile duct epithelium often exfoliates, so if some epithelium remained, pathologists were asked to render diagnosis for epithelial lesions. Each observer was blinded to the original diagnosis and the findings of the other two observers.

For the next step, the three pathologists met together to establish a new histological classification for lesions of the ductal resection margin. Lesions for which diagnoses differed between pathologists in terms of negative and positive margins on initial slide review were discussed. After this meeting, the consensus histological classification with distinction between epithelial and intramural lesions was adopted.

Validity and reproducibility of the new histological classification. Four independent pathologists, all of whom were general surgical pathologists (MM, TO, II and SY) were educated in the new histological classification in a review of specimens (using the 68 stumps of the 45 cases from East Hospital) by the three pathologists who participated in the consensus meeting. To test the validity and reproducibility of the new histological classification, the four independent observers were then asked to review 120 stumps (80 proximal margins, 40 distal margins) selected at random from the 289 stumps of the 171 cases from Central Hospital. The observers were asked to diagnose each lesion based on consideration of the proposed classification. These observers were blinded to diagnoses given by the original reviewers or each other.

Correlation between the new histological classification and clinical outcomes. In this analysis, patients who underwent intra‐operative examination for the final ductal margins were enrolled. Patients with intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma or incomplete clinicopathological data were excluded. Of 216 patients, 120 patients with proximal ductal margin and 77 patients with distal ductal margin were included in the analysis of prognosis and anastomotic recurrence, which was defined as local recurrence surrounding the anastomosis confirmed by radiological examination, biopsy or autopsy.

Statistical analysis. As a measure of validity, percentage agreements and κ coefficient between the consensus diagnosis and review diagnosis were calculated with 95% confidence intervals (CI) for each diagnostic site using the pooled review diagnoses of the four review pathologists. As a measure of reproducibility, mean percentage agreement and κ coefficient among each pair of the four review pathologists (i.e. 6 combinations) were calculated for each diagnostic site. As a measure of agreement, κ coefficient is commonly interpreted as follows: 0.00–0.20, slight; 0.21–0.40, fair; 0.41–0.60, moderate; 0.61–0.80, substantial; and 0.80–1.00, almost perfect agreement.( 10 )

The Cox proportional hazards model was used to estimate hazard ratio (HR) and 95% CI of overall survival by margin status according to the new histological classification. Multivariate analyses were performed using the clinicopathological factors identified to be associated with overall survival by univariate analyses. All tests were two‐sided and values of P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

All statistical analyses were performed by an expert statistician (MI) using SAS software, version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, US).

Results

New histological classification for intra‐operative histological examination of ductal resection margins in cholangiocarcinoma. In the initial review, of the 230 proximal margin specimens, the number of lesions for which diagnosis varied was 55 (24%) for epithelial lesions and 28 (12%) for intramural lesions. Of the 127 distal margin specimens, the number of lesions for which diagnosis varied was 17 (13%) for epithelial lesions and 16 (13%) for intramural lesions.

At the consensus meeting, the three pathologists discussed and created a uniform histological classification, particularly for lesions with diagnoses that varied. For some of these lesions, a consensus could be reached regarding negative or positive results for malignancy. As each pathologist may have already had preconceived notions about diagnostic criteria, some lesions could not be agreed upon as negative or positive by the group.

Specimens of the ductal resection margin were frequently low quality due to distortions induced by drainage tubes or operative manipulations and complete exfoliation of the epithelium was often observed. Specimens with severe distortions or complete exfoliation of the epithelium thus could not be diagnosed. These lesions were categorized as insufficient for diagnosis. In specimens that could be diagnosed, lesions that all members agreed on as negative were categorized as negative for malignancy. Lesions that all members agreed on as positive were categorized as positive for malignancy. Lesions that could not be agreed on as negative or positive by the group were categorized as undetermined lesions.

To objectively clarify these categories, members of the consensus meeting discussed the definition of each category. As each category could be distinguished by grade of atypia, definitions were made from the perspective of cellular and structural atypia, with distinction between epithelial and intramural lesions. Finally, each category was defined as follows: ‘insufficient’ (INS), insufficient for diagnosis due to distortion of specimen; ‘negative for malignancy’ (NM), specimen shows no atypia suggestive of neoplasia; ‘undetermined lesion’ (UDL), specimen shows either cellular or structural atypia; and ‘positive for malignancy’ (PM), specimen shows both cellular and structural atypia (Table 1). Histological characteristics of atypia for ductal resection margins with distinction between epithelial and intramural lesions are shown in Table 2. Specimen is diagnosed to have atypia when one or more atypical features are seen in the specimen. Representative examples of each category in the new classification are shown in 1, 2.

Table 1.

Categories of the new histological classification for intra‐operative histological examination of ductal resection margins in cholangiocarcinoma

| Epithelial lesion | |

| Insufficient (INS) | Insufficient for diagnosis, including distortions of specimen or complete exfoliation of epithelium. |

| Negative for malignancy (NM) | Specimen shows no atypia suggestive of neoplasia. |

| Undetermined lesion (UDL) | Specimen shows either cellular or structural atypia. |

| Positive for malignancy (PM) | Specimen shows both cellular and structural atypia. |

| Intramural lesion | |

| Insufficient (INS) | Insufficient for diagnosis, including distortions of specimen or crushed atypical intramural lesion. |

| Negative for malignancy (NM) | Specimen shows no atypical glands or cell nests suggestive of neoplasia. |

| Undetermined lesion (UDL) | Specimen shows atypical glands with either structural or cellular atypia. |

| Positive for malignancy (PM) | Specimen shows atypical glands with both structural and cellular atypia. |

Table 2.

Histological characteristics of atypia in ductal resection margins for cholangiocarcinoma

| Epithelial lesion | ||

| Structural atypia | • | low‐papillary feature |

| • | micropapillary feature | |

| • | papillary feature | |

| Cellular atypia | • | nuclear stratification with loss of nuclear polarity |

| • | nuclear stratification reaching the luminal surface | |

| • | nuclear enlargement | |

| • | nuclear hyperchromasia | |

| • | irregular nuclear membrane | |

| • | increased nuclear‐to‐cytoplasmic volume ratio | |

| • | obvious large nucleoli | |

| • | frequent apoptotic figures | |

| • | frequent mitotic figures | |

| • | atypical mitotic figure | |

| Intramural lesion | ||

| Structural atypia | • | irregular multiluminal formation such as fusion of glands or cribriform architecture |

| • | solid nest pattern | |

| • | haphazard distribution of glands | |

| Cellular atypia | • | nuclear stratification with loss of nuclear polarity |

| • | nuclear enlargement | |

| • | nuclear hyperchromasia | |

| • | irregular nuclear membrane | |

| • | increased nuclear‐to‐cytoplasmic volume ratio | |

| • | obvious large nucleoli | |

| • | frequent apoptotic figures | |

| • | frequent mitotic figures | |

| • | atypical mitotic figure | |

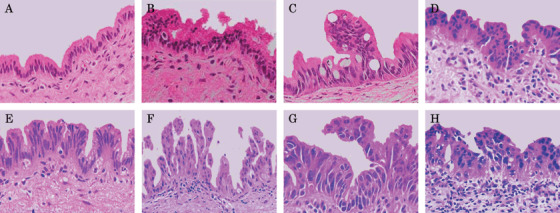

Figure 1.

Histological features of epithelial lesions at ductal resection margins for cholangiocarcinoma. (A, B) Histological features of bile duct epithelia considered negative for malignancy (NM) at the resection margin. The epithelial lesion in (B) shows nuclear stratification without loss of nuclear polarity. This histological feature is considered as reactive atypia of bile duct epithelium. (C–E) Histological features of bile duct epithelia considered as undetermined lesion (UDL) at the resection margin. Bile duct epithelia show low‐ to micropapillary features and atypical nuclei with or without loss of nuclear polarity. Atypical epithelia show large ovoid‐to‐round nuclei and some nuclei display an irregular nuclear membrane. Although the degree of atypia in UDL is lower than that in PM, determining whether UDL represents truly benign atypia or malignancy is difficult. (F–H) Histological features of bile duct epithelia considered positive for malignancy (PM) at the resection margin. Epithelia show low‐ to micropapillary features with irregularly shaped, large, atypical nuclei displaying complete loss of nuclear polarity. Apoptotic cells are also evident in some areas.

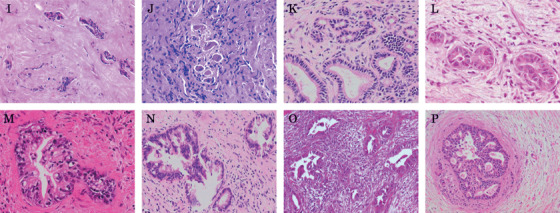

Figure 2.

Histological features of intramural lesions at ductal resection margins for cholangiocarcinoma. (I, J) Histological features of intramural lesion considered insufficient (INS) at the cut end of the bile duct. Atypical intramural lesions are seen in both figures and probably represent infiltrating carcinoma cells in the wall of the bile duct. Howeever, we are unable to define these as carcinoma cells, as all cells are crushed. (K) Normal proper glands at the cut end of bile duct (negative for malignancy, NM). (L, M) Histological features of intramural lesions considered as undetermined lesion (UDL) at the resection margin. Epithelial cells of UDL intramural lesions show irregularly shaped to round nuclei with or without loss of nuclear polarity. Epithelium of the UDL intramural lesion in (M) shows micropapillary features. Although we suspect these UDL intramural lesions represent intramural invasive carcinoma glands, the possibility of intramural proper glands showing severe reactive atypia cannot be completely excluded. (N–P) Histological features of infiltrating carcinoma cells (PM) at the resection end of the bile duct, forming irregularly shaped glands lined with epithelia showing low‐papillary to cribriform features. Epithelial cells display irregularly shaped nuclei.

Final distributions are shown in Table 3. Of the total 357 stumps, 62 epithelial lesion stumps (17%) were categorized as INS (including 59 stumps [17%] with exfoliation of epithelium) and 47 stumps (13%) were categorized as UDL. Among intramural lesions, three stumps (1%) were categorized as INS and 21 stumps (6%) were categorized as UDL.

Table 3.

Final distribution of the new histological classification

| Proximal margin (n = 230) | Distal margin (n = 127) | Total (n = 357) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epithelial | Intramural | Epithelial | Intramural | Epithelial | Intramural | |

| Insufficient (INS) | 51 (22%) | 2 (1%) | 11 (9%) | 1 (1%) | 62 (17%) | 3 (1%) |

| Negative for malignancy (NM) | 115 (50%) | 177 (77%) | 86 (68%) | 101 (80%) | 201 (56%) | 278 (78%) |

| Undetermined lesion (UDL) | 34 (15%) | 15 (7%) | 13 (10%) | 6 (5%) | 47 (13%) | 21 (6%) |

| Positive for malignancy (PM) | 30 (13%) | 36 (16%) | 17 (13%) | 19 (15%) | 47 (13%) | 55 (15%) |

Validity and reproducibility of the new histological classification. A total of 120 stumps were selected at random as materials for validity and reproducibility testing, comprising 13 INS (11%), 70 NM (58%), 19 UDL (16%) and 18 PM (15%) in epithelial lesions, and 0 INS (0%), 91 NM (76%), 6 UDL (5%) and 23 PM (19%) in intramural lesions.

In terms of validity, percentage agreement between consensus diagnosis and review diagnoses of the four observers was 73%, 85%, 78% and 87% for proximal epithelial lesions, proximal intramural lesions, distal epithelial lesions and distal intramural lesions (κ coefficients, 0.57, 0.60, 0.64 and 0.68, respectively).

In terms of reproducibility, mean percentage agreements in each pair of the four observers were 65%, 84%, 73% and 85% for each diagnostic site (mean κ coefficients, 0.46, 0.61, 0.57 and 0.57, respectively). Based on the κ coefficient, validity and reproducibility for the new criteria in this study were considered ‘moderate to substantial’ (Table 4).

Table 4.

Validity and reproducibility of the new histological classification

| Proximal margin | Distal margin | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epithelial | Intramural | Epithelial | Intramural | |

| Validity | ||||

| Percentage agreement (95% CI) | 73% (67–77%) | 85% (81–89%) | 78% (71–84%) | 87% (81–92%) |

| κ coefficient (95% CI) | 0.57 (0.49–0.64) | 0.60 (0.52–0.70) | 0.64 (0.55–0.74) | 0.68 (0.57–0.79) |

| Reproducibility | ||||

| Mean percentage agreement (range of 6 combinations) | 65% (54–74%) | 84% (75–95%) | 73% (68–78%) | 85% (83–88%) |

| Mean κ coefficient (range of 6 combinations) | 0.46 (0.32–0.59) | 0.61 (0.48–0.84) | 0.57 (0.50–0.63) | 0.57 (0.43–0.68) |

Correlation between the new histological classification and clinical outcomes. The 120 patients with proximal margins comprised 61 NM, 18 UDL in epithelial lesions, seven UDL in intramural lesions, 12 PM in epithelial lesions, and 22 PM in intramural lesions. The 77 patients with distal margins comprised 52 NM, 5 UDL in epithelial lesions, 2 UDL in intramural lesions, six PM in epithelial lesions, and 12 PM in intramural lesions.

Univariate analyses identified the following seven factors as significant prognostic factors: icterus; dissected surgical margin; size of primary tumor; histological grade; hepatic or pancreatic invasion; major vessel invasion; and lymph node metastasis.

In multivariate analyses using the significant prognostic factors mentioned above, for proximal margins, overall survival was significantly poorer for patients diagnosed with PM in intramural lesions than for those diagnosed with NM (HR, 3.02; 95% CI, 1.41–6.48). Similarly, overall survival tended to be poor for patients diagnosed with UDL in intramural lesions, but this finding was not significant (HR, 2.33; 95% CI, 0.72–7.55). Compared to patients diagnosed with NM, no difference in overall survival was found for patients diagnosed with UDL or PM in epithelial lesions.

For distal margins, overall survival was significantly poorer for patients diagnosed with PM in epithelial lesions than for those diagnosed with NM (HR, 5.03; 95% CI, 1.29–19.6). Similarly, overall survival tended to be poor for patients diagnosed with PM in intramural lesions, but the result was not significant (HR, 2.56; 95% CI, 0.79–8.34). Compared to patients diagnosed with NM, no difference in overall survival was found for patients diagnosed with UDL in epithelial and intramural lesions (Table 5).

Table 5.

Hazard ratio and 95% CI of overall survival according to the new histological classification

| Overall survival | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative for malignancy | Undetermined lesion | Positive for malignancy | |||

| Epithelial | Intramural | Epithelial | Intramural | ||

| Proximal margin | |||||

| Number of patients | 61 | 18 | 7 | 12 | 22 |

| Number of death | 35 | 11 | 6 | 5 | 20 |

| Hazard ratio † | 1.00 | 1.08 | 2.33 | 0.97 | 3.02 |

| 95% CI | 0.45–2.59 | 0.72–7.55 | 0.33–2.81 | 1.41–6.48 | |

| Distal margin | |||||

| Number of patients | 52 | 5 | 2 | 6 | 12 |

| Number of death | 34 | 4 | 1 | 5 | 9 |

| Hazard ratio † | 1.00 | 0.45 | 1.22 | 5.03 | 2.56 |

| 95% CI | 0.12–1.69 | 0.12–12.8 | 1.29–19.6 | 0.79–8.34 | |

Ajusted for icterus, dissected surgical margin, size of primary tumor, histological grade, hepatic or pancreatic invasion, major vessel invasion and lymph node metastasis.

Anastomotic recurrence was observed only on the proximal side. Patients with anastomotic recurrence on the proximal side comprised two NM (2%), 0 UDL in epithelial lesions (0%), 2 UDL in intramural lesions (29%), 1 PM in epithelial lesions (8%), and six PM in intramural lesions (27%).

Discussion

In the surgical treatment of cholangiocarcinoma, intra‐operative frozen section examination of ductal resection margins is indispensable in achieving negative margins. However, the determination of positive or negative status is difficult due to atypical lesions related to the development of cholangitis or distortions induced by drainage tubes and operative manipulations. In fact, ambiguous diagnosis can result in clinical confusion for the surgeon as to whether additional resection of the bile duct is required. No uniformly applied histological criteria have been created for intra‐operative examination of the bile duct and most pathologists seem to use an intuitive approach. Moreover, the clinical impact of epithelial lesions at ductal resection margins is prognostically different from that of intramural lesions.( 9 , 11 , 12 , 13 ) In the present study, the condition of ductal resection margins was assessed with distinction between epithelial and intramural lesions to establish a uniform classification, and correlations between the new histological classification and clinical outcomes were analyzed.

When three expert pathologists were initially asked to classify lesions of ductal resection margins using their own criteria, a unanimous diagnosis could not be reached for 12–24% of specimens. Moreover, after the consensus meeting, disagreement on positive or negative status remained for 17% of epithelial lesions and 6% of intramural lesions. Agreement was particularly difficult for epithelial lesions. Of course, reactive and neoplastic lesions may overlap among such lesions. Alternatively, the execution of this study by experts may itself have contributed to some difficulty in achieving interobserver concordance, as experts with long experience may not adapt readily to new classifications. This study aimed to create a practical and widely applicable histological classification, so that a greater degree of uniformity can be achieved in classification. Lesions for which agreement could not be reached thus had to remain as one category: UDL. As the lesions categorized as UDL could be distinguished from consensus‐negative and consensus‐positive lesions by grade of atypia, each category was defined from the perspective of grade of atypia. Finally, we propose a new histological classification for intra‐operative histological examination of ductal resection margins as defined by cellular and structural atypia, translating into the four categories of INS, NM, UDL and PM (Table 1).

Zen et al.( 14 , 15 ) recently proposed histological criteria for biliary epithelial lesions of the bile duct (biliary intra‐epithelial neoplasia (BilIN)). However, the BilIN study used intra‐epithelial atypical lesions in the biliary system of patients suffering from primary sclerosing cholangitis, choledochal cyst or hepatolithiasis. The proposed criteria in the BilIN study were made only for grading of non‐invasive or premalignant lesions with the purpose of investigating cholangiocarcinogenesis in biliary diseases. Conversely, the purpose of the present study was to establish a new histological classification for intra‐operative histological examination of ductal resection margins in cholangiocarcinoma, with distinction between epithelial and intramural lesions. Actually, in biliary lining epithelia of the bile ducts, epithelial lesions categorized UDL in the present study may contain the lesions diagnosed as BilIN‐3 or BilIN‐2. To clarify a correlation between the proposed histological classification and the BilIN criteria, we need further investigations with clinical outcomes.

Validity and reproducibility of the proposed classification were found to be moderate to substantial, with κ coefficients of 0.57–0.68 for the validity test and 0.46–0.61 for the reproducibility test. These results were better than those described in the BilIN study.( 14 , 15 )

Moreover, the analysis of correlations between the new histological classification and clinical outcomes suggested a guideline for intra‐operative judgment of ductal margin status. Patients diagnosed with PM in intramural lesions of the proximal margin showed poor prognosis and high risk of anastomotic recurrence. For UDL in intramural lesions of the proximal margin, no significant difference in overall survival was found from NM lesions. However, HR was 2.33 and anastomotic recurrence rate was high (29%). In these cases, additional resection of the bile duct is required if long‐term survival is to be obtained. Meanwhile, in patients diagnosed with PM in epithelial lesions of the proximal margin, no difference in overall survival was found for patients diagnosed with NM. Previous reports have indicated that PM in epithelial lesions does not represent a poor prognostic factor.( 9 , 13 ) However, these reports emphasized that residual epithelial lesions cause late anastomotic recurrence. In the present study, one patient diagnosed with PM in epithelial lesions developed anastomotic recurrence. The need for additional resection of the bile duct should thus be decided after taking the clinical factors and risk of postoperative morbidity–mortality into consideration. For UDL in epithelial lesions, no difference in overall survival was seen from NM lesions and anastomotic recurrence was not observed. Additional ductal resection was not necessary for lesions with either cellular or structural atypia.

Although for the distal margin, patients diagnosed with PM in epithelial lesions showed significant poor prognosis, the number of cases analyzed for the distal margin was small. The implications regarding the distal margin need to be further clarified with a larger number of cases.

The proposed classification in this study allows very simple assessment of not only epithelial lesions but also intramural lesions, resulting in easy diagnosis of both lesions on routine examination, particularly in the diagnosis of frozen ductal resection margins for cholangiocarcinoma. The results of correlation analysis between the new histological classification and clinical outcomes suggest guidelines for intra‐operative judgment of ductal margin status. This classification may thus reduce the stress associated with intra‐operative examination of ductal resection margins for both pathologists and surgeons.

Although the proposed histological classification represents high‐level agreement and shows a correlation with patients’ prognoses, whether the new histological classification might be applicable to diagnosis of ductal resection margins for cholangiocarcinoma is unclear. In particular, the clinical implication of distal resection margin and the correlation with anastomotic recurrence were inconclusive. Practical clinical implications of this new histological classification must be established in rigorous clinical studies using a greater volume of materials from multiple centers. This study represents the first step in clarifying the implication of ductal resection margin status in cholangiocarcinoma.

One more issue remains in intra‐operative histological examination. This study included 17% INS specimens, so specimens of ductal resection margins should be carefully handled to allow establishment of accurate diagnosis.

In conclusion, we propose a new histological classification for intra‐operative histological examination of ductal resection margins in cholangiocarcinoma that has shown a correlation with patient prognosis. The proposed classification should facilitate the determination of ductal resection margin status in cholangiocarcinoma.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant‐in‐aid for cancer research from the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare of Japan.

References

- 1. Kosuge T, Yamamoto J, Shimada K, Yamasaki S, Makuuchi M. Improved surgical results for hilar cholangiocarcinoma with procedures including major hepatic resection. Ann Surg 1999; 230: 663–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jarnagin WR, Fong Y, DeMatteo RP et al . Staging, respectability, and outcome in 225 patients with hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Surg 2001; 234: 507–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kawasaki S, Imamura H, Kobayashi A, Noike T, Miwa S, Miyagawa S. Results of surgical resection for patients with hilar bile duct cancer: application of extended hepatectomy after biliary drainage and hemihepatic portal vein embolization. Ann Surg 2003; 238: 84–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Seyama Y, Kubota K, Sano K et al . Long‐term outcome of extended hemihepatectomy for hilar bile duct cancer with no mortality and high survival rate. Ann Surg 2003; 238: 73–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hemming AW, Reed AI, Fujita S, Foley DP, Howard RJ. Surgical management of hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Surg 2005; 241: 693–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Baton O, Azoulay D, Adam DVR, Castaing D. Major hepatectomy for hilar cholangiocarcinoma type 3 and 4: prognostic factor and longterm outcome. J Am Coll Surg 2007; 204: 250–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Albores‐Saavedra J, Henson DE, Klimstra DS. Tumors of the Gallbladder, Extrahepatic Bile Ducts, and Ampulla of Vater, 3rd edn. Washington DC: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, 2000; 191–215. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Okazaki Y, Horimi T, Kotaka M, Morita S, Takasaki M. Study of the intrahepatic surgical margin of hailar bile duct carcinoma. Hepatogastroenterology 2002; 49: 625–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wakai T, Shirai Y, Moroda T, Yokoyama N, Hatakeyama K. Impact of ductal resection margin status on long‐term survival in patients undergoing resection for extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Cancer 2005; 103: 1210–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977; 33: 159–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sakamoto E, Nimura Y, Hayakawa N et al . The pattern of infiltration at the proximal border of hilar bile duct carcinoma: a histologic analysis of 62 resected cases. Ann Surg 1998; 227: 405–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ebata T, Watanabe H, Ajioka Y, Oda K, Nimura Y. Pathological appraisal of lines of resection for bile duct carcinoma. Br J Surg 2002; 89: 1260–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nakanishi Y, Zen Y, Kawakami H et al . Extrahepatic bile duct carcinoma with extensive intraepithelial spread: a clinicopathological study of 21 cases. Mod Pathol 2008; 21: 807–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zen Y, Aishima S, Ajioka Y et al . Proposal of histological criteria for intraepithelial atypical/proliferative biliary epithelial lesions of the bile duct in hepatolithiasis with respect to cholangiocarcinoma: preliminary report based of interobserver agreement. Pathol Int 2005; 55: 180–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zen Y, Adsay NV, Bardadin K et al . Biliary intraepithelial neoplasia: an international interobserver agreement study and proposal for diagnostic criteria. Mod Pathol 2007; 20: 701–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]