Abstract

Natural killer (NK) cells are an important component of the innate immune response against microbial infections and tumors. Direct involvement of NK cells in tumor growth and infiltration has not yet been demonstrated clearly. Primary effusion lymphoma (PEL) cells were able to produce tumors and ascites very efficiently with infiltration of cells in various organs of T‐, B‐ and NK‐cell knock‐out NOD/SCID/γcnull (NOG) mice within 3 weeks. In contrast, PEL cells formed small tumors at inoculated sites in T‐ and B‐cell knock‐out NOD/SCID mice with NK‐cells while completely failing to infiltrate into various organs. Immunosupression of NOD/SCID by treatment with an antimurine TM‐β1 antibody, which transiently abrogates NK cell activity in vivo, resulted in enhanced tumorigenicity and organ infiltration in comparison with non‐treated NOD/SCID mice. Activated human NK cells inhibited tumor growth and infiltration in NOG mice. Our results suggest that NK cells play an important role in growth and infiltration of PEL cells, and activated NK cells could be a promising immunotherapeutic tool against tumor or virus‐infected cells either alone or in combination with conventional therapy. The rapid and efficient engraftment of PEL cells in NOG mice also suggests that this new animal model could provide a unique opportunity to understand and investigate the mechanism of pathogenesis and malignant cell growth. (Cancer Sci 2006; 97: 1381–1387)

Primary effusion lymphoma (PEL) was originally identified in AIDS‐associated immunodeficient patients and has been recognized by the World Health Organization as a distinct AIDS‐related form of B‐cell lymphoproliferative disorder.( 1 , 2 , 3 ) PEL is a non‐Hodgkin's type lymphoma derived from postgerminal center B cells.( 4 ) The tumor clone is characteristically infected by the Kaposi's sarcoma‐associated herpesvirus, formerly called human herpesvirus type 8 (HHV‐8),( 5 ) and most cases are coinfected with Epstein–Barr virus.( 6 , 7 ) PEL shows a peculiar presentation involving lymphomatous effusions of serous cavities and only occasionally presents with a definable mass.( 5 )

Immunodeficient mouse models of human malignancy have contributed significantly to understanding the pathogenesis of diseases as well as therapeutic purpose. The congenitally athymic and hairless nude mouse lacking functional T cells has been utilized as a host for human xenotransplantations for 30 years.( 8 ) Thereafter, severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) mice were found to have a genetic defect preventing functional development of T and B lymphocytes,( 9 , 10 ) and can be engrafted successfully with a variety of normal hematopoietic and neoplastic cells.( 11 , 12 ) In comparison with conventional SCID, the NOD‐SCID strain appears to be more promising as a tool for xenotransplantion of human tumors. However, the NOD‐SCID mouse strain retains natural killer (NK) cell activity, macrophage function, complement activity and functional dendritic cells.( 13 ) NK cells might play an important role in the rejection of implanted tissues or cells in SCID mice.( 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 ) Although several models using mainly conventional nude and SCID mice are available, there are some major drawbacks: the requirement of long time periods, repeated transplantation, total body irradiation of mice, hormone supplements, etoposide pretreatment and anti‐NK monoclonal antibodies required for tumor formation. These problems appear to hinder wider use of these animal models. Due to the low engraftment efficiency of hematopoietic and tumor cells transplanted in SCID mice, T, B and NK knock‐out NOD/SCID/γcnull (NOG) mice were used in the present study to investigate the role of NK in tumor growth and metastasis.( 13 )

Natural killer cells are a type of lymphocyte that comprises up to 15% of peripheral blood lymphocytes and mediates innate immunity against pathogens and tumors.( 17 ) In addition, NK cells are an important source of cytokines that regulate hematopoiesis and link the innate to the adaptive immune response through a bidirectional cross‐talk with dendritic cells.( 18 , 19 ) NK cells were originally discovered because of their ability to kill tumor and virally infected cells in vitro. NK‐cell activity against these in vitro targets is spontaneous; it is readily apparent in individuals who have not been previously exposed to the target cell antigens. A clear involvement of NK cells in antitumor immunity in vivo, and the involvement of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I in NK‐cell recognition, was shown in 1986 by Karre and colleagues.( 20 ) They showed that the RMA T‐cell lymphoma, derived from the Rauscher virus‐induced murine cell line RBL‐5, grew progressively in syngenic mice, but that an MHC class I‐negative variant, RMA‐S, was rejected by host NK cells. In many different situations, NK cells were shown to kill certain tumor cell lines in vitro, despite significant levels of MHC class I on their cell surface.( 21 , 22 ) This implied that killing of MHC class I+ tumor cells was mediated by activating receptors that were either not impaired by the inhibitory NK receptors for MHC class I or provided sufficient stimulation to overcome the negative regulation.

One cohort study showed that individuals with low natural cytotoxic activity of peripheral blood lymphocytes are at a significantly higher risk of cancer, compared with those of median or high activity.( 23 ) It has been reported recently that NK cells isolated from HIV‐infected individuals are impaired in their ability to kill the virus‐infected autologous cells, as well as tumor cell lines.( 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 ) Previous studies also reported that NK‐cell activity controls PEL and Kaposi's sarcoma (KS) development associated with HHV‐8 infection.( 28 , 29 ) The ability of the NK cells to kill relevant targets, such as tumor or virally infected cells, depends on the delicate balance of the patterns of expression of MHC class I‐specific inhibitory NK receptors and activating receptors.( 30 , 31 ) As there is no animal model in which NK‐cell activities are genetically and selectively deficient to rule out the function of NK cells in viral infection and tumor growth and metastasis, most studies have relied on depleting NK cells in mice using monoclonal or polyclonal antibodies.( 32 , 33 ) Depletion of NK cells in vivo by anti‐NK antibody leads to enhanced tumor formation in several mouse tumor models.( 15 , 34 ) Therefore, the role of NK cells in the course of tumor growth and infiltration as well as viral infection remains one of the major topics in tumor immunology.

In the present study, we investigated the direct involvement of NK cells in growth and infiltration of PEL cells using T, B and NK knock‐out NOG mice,( 13 , 35 , 36 ) and T and B knock‐out NOD/SCID mice. NK knock‐out NOG mice were most efficient in the formation of large tumors, massive ascites and infiltration within 3 weeks in comparison with NK‐bearing NOD/SCID mice. We also provide evidence that activated human NK cells inhibit tumor growth and infiltration in NOG mice. These results suggest that NK cells play an important role in tumor growth and infiltration, and activated NK cells could be a promising immunotherapeutic strategy against AIDS‐associated PEL or other malignancies either alone or in combination with conventional therapy.

Materials and Methods

Mice and inoculation of cell lines. NOG and NOD/SCID mice were obtained from the Central Institute for Experimental Animals (Kawasaki, Japan). All mice were maintained under specific pathogen‐free conditions at the Animal Center of Tokyo Medical and Dental University (Tokyo, Japan). The Ethical Review Committee of the institute approved the experimental protocol.

Primary effusion lymphoma cell lines BCBL‐1( 37 ) and TY‐1,( 38 ) NK cell line KHYG‐1 and bcr‐abl+ leukemic cell line K562 were cultured in RPMI‐1640 medium supplemented with 2% heat‐inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS; JRH Biosciences, Lenexa, KS, USA), 100 U/mL penicillin and 10 µg/mL streptomycin. BCBL‐1 and TY‐1 cells were washed twice with serum‐free RPMI‐1640 and resuspended in fresh RPMI‐1640. Mice were anesthetized with ether and cells were inoculated either subcutaneously (sc) in the postauricular region or intraperitoneally (ip) in the abdominal region of mice at doses of 1 × 107 and 2 × 106 cells per mouse, respectively. BCBL‐1 cells were also inoculated either sc in the postauricular region or ip in the abdominal region of NOD/SCID mice with or without pretreatment with TMβ1 antibody, or in NOG mice. All mice were killed 3 weeks after inoculation with PEL cells. We measured tumor size, collected ascites from the abdomen of mice, and measured the volume of ascites.

Isolation and culture of NK cells. Blood was collected after obtaining informed consent from healthy volunteers. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were isolated from the blood by Ficoll‐Hypaque gradient centrifugation (Amersham Biosciences, Uppsala, Sweden), washed twice with RPMI‐1640, and the number of cells counted. To generate activated NK cells, PBMC were cultured in anti‐CD16‐coated flasks with AIM‐V medium (Invitrogen, Tokyo, Japan) supplemented with 5% auto‐plasma, 700 U/mL interleukin (IL)‐2 (Chiron, Amsterdam, the Netherlands), and 1 µL/mL OK432 (Chugai Pharmaceutical, Tokyo, Japan) for 24 h at 39°C, and then the cultured cells were centrifuged at 550 g for 10 min and the supernatants were discarded. Cells were again cultured in anti‐CD16‐uncoated flasks with AIM‐V medium supplemented with 5% auto‐plasma, and 700 U/mL IL‐2 at 37°C for 2–3 weeks. During culture periods, we added medium several times for expansion and maintenance of activated NK cells. The purity of NK cells was 92–95%.

Flow cytometric analysis and cytotoxic activity. For five‐color flow cytometric analysis (Cytomics FC500; Beckman Coulter, Miami, FL, USA), freshly isolated and activated NK cells were stained with monoclonal antibodies (ECD‐labeled anti‐CD3, PC5‐labeled anti‐CD4, PC7‐labeled anti‐CD8, PC7‐labeled anti‐CD16, PE or PC7‐labeled anti‐CD45, PC5‐labeled anti‐CD56, and PE‐labeled anti‐CD69 [Immunotech, Marseile, France]) and appropriate anti‐isotypic monoclonal antibodies stained as negative controls. Data were analyzed by using CXP Analysis software version 1.1.

Freshly isolated and activated NK cells were tested for cytotoxic activity at various effector‐to‐target (E/T) ratios in a calcein‐AM release assay using TERASCAN VP (Minerva Tech., Tokyo, Japan). We labeled the target cells with the immunofluorescent dye Calcein‐AM solution (Do Jindo Laboratory, Kumamoto, Japan) and incubated them for 30 min. The cells were then washed with phosphate‐buffer saline (PBS)(–) and the fluorescence intensity checked. Target cells and effector cells were suspended in RPMI‐1640 with 10% FBS at various E/T ratios, added into 96‐well plates and incubated for 2 h, and the fluorescence intensity was again checked.

Inoculation of activated NK cells into mice and collection of samples. Mice were inoculated with BCBL‐1 (2 × 106) cells ip in the abdominal region of NOG mice. Three days after inoculation of PEL cells, mice were treated with either RPMI‐1640 (control mice) or activated NK cells (1 × 107) ip on days 4, 10 and 17. All mice were killed 3 weeks after inoculation with PEL cells. We measured tumor size, collected ascites from the abdomen of mice, and measured the volume of ascites. Tissues and various organs of mice were also collected and fixed with 10% buffered formalin (Streck Tissue Fixative, Omaha, NE, USA), then processed to paraffin‐embedded sections for staining with hematoxylin and eosin (HE) and immunostaining.

Immunohistochemistry. Paraffin sections of various organs were deparaffinized and hydrated in xylene or clearing agents and a graded alcohol series, then rinsed for 5 min in water. Deparaffinized samples were incubated with 0.025% trypsin/PBS for 30 min followed by washing, and then incubated with 0.3% H2O2 in methanol for 30 min at room temperature before being washed twice with PBS. Immunostaining was done for PEL cells with a 1:500 dilution of primary rabbit polyclonal antibody specific for HHV‐8‐encoded LANA.( 39 ) This was followed by washing in PBS and incubation with a secondary antibody, biotinylated antirabbit IgG, after which cells were again washed in PBS and incubated with horseradish peroxidase‐conjugated streptavidin for 30 min at room temperature. After two washes in PBS, the amplification procedure was carried out using kits according to the manufacturer's instructions (catalyzed signal amplification system kit; DAKO, Copenhagen, Denmark). The signal was visualized using 0.2 mg/mL diaminobenzidine and 0.015% H2O2 in 0.05 M Tris‐HCl, pH 7.6. Positive staining was visualized after incubation of these samples with a mixture of 0.05% 3,3′‐diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride in 50 mM Tris‐HCl buffer and 0.01% H2O2 for 5 min. The samples were counterstained with hematoxylin for 2 min, dehydrated completely, cleaned in xylene and then mounted. HE and immunostaining were visualized and photographed under light microscopy (BX41 and DP70; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

Statistical analysis. The statistical analysis was carried out using StatView J‐4.5 (Hulinks, Tokyo, Japan).

Results

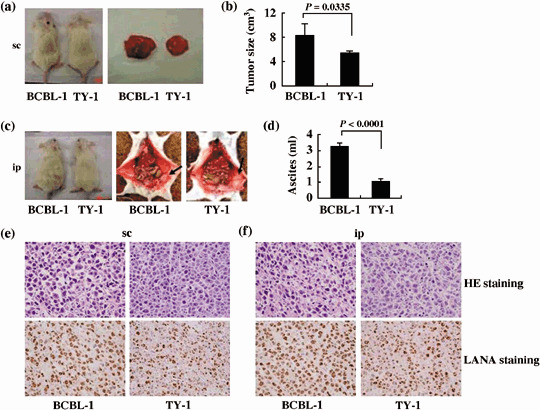

Rapid tumor and massive ascites formation and infiltration of PEL cells in T, B and NK knock‐out NOG mice. To investigate in vivo growth, PEL cell lines (BCBL‐1 and TY‐1) were inoculated sc in the postauricular region of NOG mice (Fig. 1a,b). Mice inoculated with cell lines BCBL‐1 and TY‐1 produced a visible tumor within 3 weeks in all NOG mice. The BCBL‐1 cell line was very efficient in the formation of a large tumor (Fig. 1a,b), as well as development of clinical signs of near‐death, such as pilorection, weight loss and cachexia in mice at the time of killing. The average tumor size in NOG mice inoculated with BCBL‐1 and TY‐1 was 8.25 cm3 and 5.43 cm3, respectively. PEL is an AIDS‐associated non‐Hodgkin's lymphoma that is characterized by lymphomatous effusions of serous cavities and rarely presents with a definable tumor mass.( 5 , 7 ) To establish a clinically relevant PEL model, we inoculated BCBL‐1 and TY‐1 cells ip in the abdominal region of NOG mice (Fig. 1c,d). BCBL‐1 and TY‐1 produced massive ascites and a small tumor mass in the peritoneal cavity within 3 weeks of inoculation in all mice. The BCBL‐1 cell line was most efficient in the formation of massive ascites (Fig. 1c,d), as well as development of clinical signs of near‐death. The average volume of ascites in NOG mice inoculated with BCBL‐1 and TY‐1 was 3.26 mL and 1.05 mL, respectively. To test whether tumors maintain original histomorphology and expression patterns of tumor markers in NOG, we carried out HE and immunostaining of tumor tissues and various organs obtained from mice inoculated with BCBL‐1 and TY‐1 cells. Histological and immunological analysis revealed that in vivo tumor cells had well‐preserved morphology as well as expression of the viral gene LANA (Fig. 1e,f). These results show that PEL cell lines inoculated either sc into the postauricular region or ip in the abdominal region of NOG mice were able to produce a large tumor and ascites very efficiently. Interestingly, ip‐inoculated PEL cells were found to form clinically relevant lymphomatous effusions in the peritoneal cavity as well as a small definable mass.

Figure 1.

Successful engraftment and tumor marker of primary effusion lymphoma (PEL) cells in T, B and natural killer (NK) knock‐out NOG mice. (a) Photograph of mice inoculated with BCBL‐1 and TY‐1 cells subcutaneously in the postauricular region (left panel) and those of subcutaneously formed BCBL‐1 and TY‐1 tumor 3 weeks after inoculation of cells (right panel). (b) Subcutaneous tumor size of mice inoculated with BCBL‐1 and TY‐1 cells, shown as the mean ± s.e.m. from five mice (P = 0.0335). (c) Photograph of ascites‐bearing mice inoculated with BCBL‐1 and TY‐1 cells intraperitonealy in the abdominal region (left panel) and peritoneal cavity of mice 21 days after inoculation of BCBL‐1 (middle panel) and TY‐1 cells (right panel). Arrow head indicates the tumor in mice inoculated intraperitonealy. (d) Volume of ascites in mice inoculated with various BCBL‐1 and TY‐1 cells, shown as the mean ± s.e.m. from five mice (P < 0.0001). (e,f) Hematoxylin–eosin (HE) and immunohistochemical staining of tumor tissue of BCBL‐1 and TY‐1 cells injected mice. Upper panels represent HE staining. Immunohistochemical staining was conducted using rabbit anti‐LANA (lower panels). Left and right panels represent results with BCBL‐1 and TY‐1, respectively (magnification, ×40). Data are from (e) mice inoculated subcutaneously and (f) mice inoculated intraperitonealy.

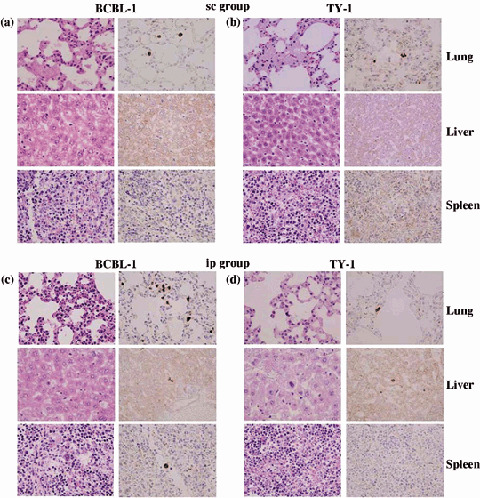

To assess the tissue distribution of PEL cells, we carried out histological examinations of the different organs of NOG mice after inoculation of the cells. Infiltration of tumor cells was found not only in primary tumor tissues, but also to a lesser extent in the lung of NOG mice inoculated sc with BCBL‐1 and TY‐1 (Fig. 2a,b). We found that mice inoculated ip with BCBL‐1 cells exhibited infiltration in the lung, liver and spleen (Fig. 2c), whereas TY‐1 cells did so to a lesser extent only in the lung and liver (Fig. 2d). HE and immunohistochemical staining showed a degree of infiltration of tumor cells at the site of inoculation and various organs with BCBL‐1 and TY‐1 (Fig. 2). Furthermore, BCBL‐1 was most efficient at infiltrating the lung (Fig. 2a,c). Interestingly, ip‐inoculated PEL cells appeared to infiltrate various organs of mice more aggressively and massively than sc inoculation. This extremely rapid tumor formation and infiltration in all mice is one of the hallmarks of our clinically relevant animal model without changes in histomorphology or tumor marker expression.

Figure 2.

Metastasis of primary effusion lymphoma (PEL) cells in various organs of T, B and natural killer (NK) knock‐out NOG mice. (a–d) Histological analysis of lung, liver and spleen of mice inoculated with BCBL‐1 and TY‐1 cells either (a,b) subcutaneously (sc) or (c,d) intraperitonealy (ip). Immunohistochemical staining was conducted using anti‐LANA. Data are from (a,c) BCBL‐1‐inoculated mice and (b,d) TY‐1‐inoculated mice. Left and right panels of all figures represent hematoxylin–eosin and immunostaining, respectively (magnification, ×40).

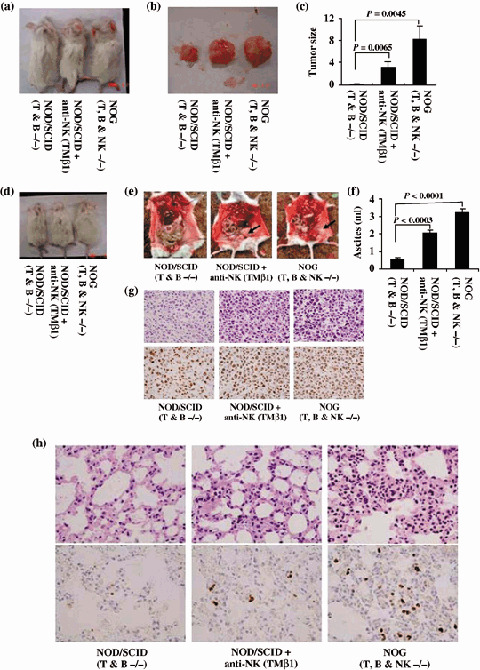

Role of NK cells in the growth and infiltration of PEL cell in vivo. Severe combined immunodeficiency mice lack functional T and B lymphocytes, but NK‐cell activity remains normal.( 10 , 17 , 40 ) Despite severe immunological defects, SCID mice have the ability to reject xenografts. Further, immunosupression of SCID by treatment with etoposide, irradiation or an anti‐NK antibody, which transiently abrogates NK‐cell activity in vivo, results in enhanced tumor growth in mice.( 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 ) To determine the possibility that NK‐cell activity suppresses tumorigenesis in conventional SCID mice, the PEL cell line BCBL‐1 was inoculated either sc in the postauricular region or ip in the abdominal region of T and B knock‐out NOD/SCID mice with or without pretreatment of with TMβ1 antibody, or T, B and NK knock‐out NOG mice (Fig. 3a−g). BCBL‐1 cells were able to produce tumors at inoculation sites in NOD/SCID mice with common γ‐chain. Immunosupression of NOD/SCID by treatment with an antimurine TMβ1 antibody, which transiently abrogates natural killer cell activity in vivo, resulted in induction of larger tumor and ascites formation in comparison with non‐treated NOD/SCID mice. NOG mice lacking common γ‐chain inoculated with BCBL‐1 cells were most efficient in the formation of large tumor and massive ascites within 3 weeks. NOG mice have a defective common cytokine receptor, γ chain. Mutation in the common cytokine receptor γ chain leads to life‐threatening, X‐linked, severe combined immunodeficiency disease (XSCID) in humans, characterized by an extremely low number of T and NK cells.( 48 , 49 ) These results suggest that NK cells are responsible for the formation of a progressively growing rapid large tumor and massive ascites of PEL cells in SCID mice at inoculation sites.

Figure 3.

Natural killer (NK) cells in tumor growth and infiltration. BCBL‐1 cells were inoculated subcutaneously in the postauricular region or intraperitonealy in the abdominal region of T and B knock‐out NOD/SCID, TMβ1‐pretreated T and B knock‐out NOD/SCID and T, B and NK knock‐out NOG mice. (a) Photograph of mice inoculated with BCBL‐1 cells subcutaneously in the postauricular region. (b) Photograph of BCBL‐1 tumor 3 weeks formed subcutaneously after inoculation of cells. (c) Subcutaneous tumor size of mice inoculated with BCBL‐1 cells, shown as the mean ± s.e.m. from six mice. Tumor size of TMβ1‐pretreated NOD/SCID mice was significantly larger than NOD/SCID (P = 0.0065) and that of NOG mice was more significant than NOD/SCID (P = 0.0045). (d) Photograph of ascites‐bearing mice inoculated with BCBL‐1 cells intraperitonealy in the abdominal region. (e) Photograph of the peritoneal cavity of mice 3 weeks after inoculation of BCBL‐1. Left, middle and right panels represent the T and B knock‐out NOD/SCID, TMβ1‐pretreated T and B knock‐out NOD/SCID and T, B and NK knock‐out NOG mice, respectively. Arrow head indicates the tumor in mice inoculated intraperitonealy. (f) Volume of ascites in mice inoculated with BCBL‐1 cells, shown as the mean ± s.e.m. from six mice. Volume of ascites in TMβ1‐pretreated NOD/SCID mice was significantly higher than NOD/SCID (P = 0.0003) and that of NOG mice was more significant than NOD/SCID (P < 0.0001). Hematoxylin–eosin (HE) and immunohistochemical staining of (g) lung tissue and (h) tumor tissue of BCBL‐1‐injected mice. Upper panels represent HE staining. Immunohistochemical staining was conducted using rabbit anti‐LANA (lower panels). Left, middle and right panels represent results from T and B knock‐out NOD/SCID, TMβ1‐pretreated T and B knock‐out NOD/SCID and T, B and NK knock‐out NOG mice, respectively. Magnification, ×40.

Severe combined immunodeficiency mice have NK cells, an important immune effector population implicated in protection against tumor metastasis and viral infection.( 17 , 50 ) It has been reported recently that individuals with low natural cytotoxic activity of peripheral blood lymphocytes are at a significantly higher risk of cancer, compared with those of median or high activity, as well as functional impairment of NK cells in viral infection.( 23 ) To assess the infiltration of PEL cells, we carried out histological examinations of tumor tissue and the different organs of mice inoculated with BCBL‐1 cells (Fig. 3h). Infiltration of tumor cells was found in various organs of NOG mice inoculated with BCBL‐1 cells. We found that NOD/SCID inoculated with BCBL‐1 cells exhibited no infiltrate in any organs. NOD/SCID mice immunosuppressed by pretreatment with anti‐NK antibody showed infiltration of PEL cells to a lesser extent in various organs of mice inoculated with BCBL‐1 cells. HE and immunohistochemical staining showed a degree of infiltration of tumor cells in the lung of mice inoculated with BCBL‐1 (Fig. 3h). These results suggest that NK cells play an important role in the infiltration of cancer cells in various organs.

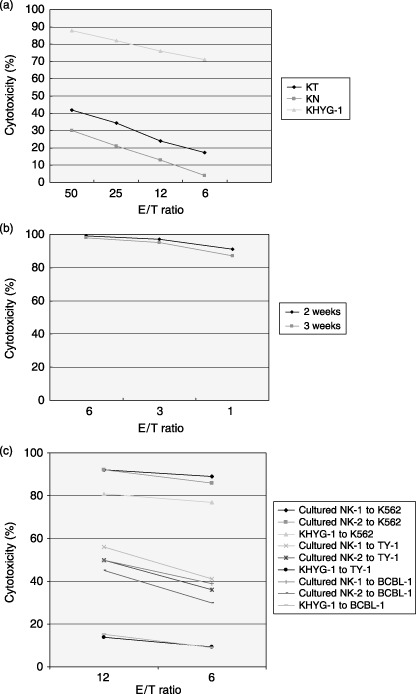

Activated NK cells inhibit tumor growth and infiltration in vivo. As the above results suggested the potential role of NK cells in tumor growth and metastasis, we next examined whether adoptive transfer of activated NK cells could inhibit tumor growth and infiltration of xenografted PEL cells in the NOG mouse model. For this purpose, freshly isolated PBMC from the blood of healthy donors were cultured for 2–3 weeks to generate NK cells. NK cells were expanded ex vivo by several hundred to 2500‐fold after 2 weeks cultivation and the expression level of CD69, an activated marker of NK cells, was increased dramatically. The purity of the activated NK cells used in the present study was 92–95% (data not shown). NK cells use cytoplasmic granules containing perforins and granzymes to kill the target cells. Using a highly sensitive flow cytometry‐based intracellular cytokine assay, we next investigated the expression of intracellular perforins and granzymes in NK cells. Intracellular perforin and granzyme expression was increased in activated culture cells in comparison to freshly isolated cells from healthy donors (data not shown). PBMC, NK cell line KHYG‐1 and activated NK cells were analyzed for cytotoxic activity against the NK‐susceptible K562 erythroleukemia cell line (Fig. 4a,b). Cytotoxic activity of cells cultured for 2 weeks was increased significantly compared with freshly isolated PBMC from healthy donors (Fig. 4b). Activated NK cells also killed PEL cells efficiently in vitro at various E/T ratios, but the NK cell line KHYG‐1 did not (Fig. 4c).

Figure 4.

Cytotoxic activity of activated natural killer (NK) in vitro culture cells. (a) Spontaneous cytotoxic activity of freshly isolated peripheral blood mononuclear cells (KT‐1 and KN‐2 represent samples from two donors) and NK cell line KHYG‐1 against K‐562 cells at different effector‐to‐target (E/T) ratios. (b) Cells cultured for 2 weeks against K‐562 cells at different E/T ratios. (c) Cytotoxic activity of activated NK cells (NK‐1 and NK‐2 represent samples from two donors) against primary effusion lymphoma cells in vitro at various E/T ratios.

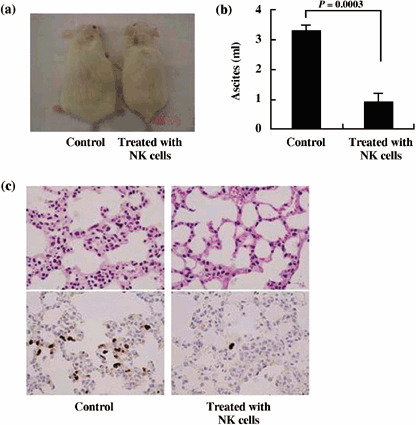

To examine the antitumor effect of activated NK cells against PEL, we injected the PEL cell line BCBL‐1 (2 × 106) ip into the abdominal region of NOG mice. Three days after inoculation, mice were treated with either RPMI‐1640 (as control) or activated NK cells (1 × 107) ip on days 4, 10 and 17. BCBL‐1 cell inoculation promoted the development of massive ascites in the peritoneal cavity of all control mice within 3 weeks of inoculation. In contrast, activated NK‐treated mice appeared to be healthy and had a significantly lower volume of ascites (Fig. 5a,b). Clinical evaluation of organ infiltration 3 weeks after injection of PEL cells showed that activated NK treatment inhibited their infiltration into the lung. In contrast, all control mice showed massive infiltration of tumor cells into the lung (Fig. 5c). Organ infiltration of tumor cells was analyzed and evaluated by HE and immunostaining of LANA. These data indicate that activated NK cells significantly inhibit the growth and infiltration of PEL cells in vivo (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Inhibition of primary effusion lymphoma (PEL) cell growth and infiltration in NOG mice. T, B and natural killer (NK) knock‐out NOG mice were injected with PEL cells (2 × 106) intraperitonealy in the abdominal region. Mice were administered either RPMI‐1640 or activated NK cells (1 × 107) intraperitonealy on days 4, 10 and 17 followed by observation for up to 3 weeks. (a) Photograph of ascites‐bearing control PEL mice and activated NK‐treated PEL mice. (b) Volume of ascites in control PEL mice and activated NK‐treated PEL mice. Volume of ascites in mice inoculated with BCBL‐1 cells, shown as the mean ± s.e.m. from six mice (P = 0.0003). (c) Hematoxylin–eosin (HE) and immunohistochemical staining of the lung of NOG mice 3 weeks after inoculation of PEL cells using anti‐LANA. Upper and lower panels show HE and immunohistochemical staining, respectively. Left and right panels represent the data from control mice and mice treated with activated NK cells, respectively. Magnification, ×40. The data represent six mice in each group and three healthy donors (two mice for each donor).

Discussion

Natural killer cells form a first line of defense against pathogens or host cells that are stressed or cancerous. To execute the concept of using activated NK cells in order to prevent cancer, it is indispensable to know how NK cells are important for tumor growth and infiltration. There have been a number of reports about the contribution of NK cells in tumor growth and metastasis. In particular, whole‐body irradiation has been reported to suppress NK activity and increase the ability of human and murine tumors to be transplanted into SCID mice.( 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 ) Treatment of mice with murine anti‐NK antibody, which transiently inhibits NK‐cell activity, results in efficient engraftment of tumor cells in SCID mice.( 15 , 47 ) In the present study, we demonstrated the direct role of NK cells in tumor growth and metastasis using T, B and NK knock‐out NOG and T and B knock‐out NOD/SCID mice. PEL cells were able to produce a large tumor and massive ascites very efficiently at inoculated sites and infiltrate various organs in T, B and NK nock‐out NOG mice. We found that T and B knock‐out NOD/SCID mice inoculated with PEL cells formed small tumors and a lower volume of ascites, but completely failed to infiltrate. T and B knock‐out NOD/SCID mice were further immunosuppressed by pretreatment with anti‐NK antibody, which enhanced tumor and ascites formation as well as organ infiltration. These results demonstrate the critical role of NK cells in tumor growth and infiltration using NK knock‐out mice. It is of particular importance that ip‐inoculated PEL cells were found to form clinically relevant lymphomatous effusions in the peritoneal cavity and small tumor mass as well as infiltration. This clinically relevant animal model without changes in its histomorphology or tumor marker expression would be useful to understand and investigate the mechanism of PEL cell growth and infiltration.

In patients with cancer and viral infection, NK‐cell function has been shown to be impaired, as determined by the reduced proliferation, response to interferon (IFN), and cytotoxicity of the cells of patients ex vivo.( 51 , 52 ) In the present study, we inoculated activated NK cells to treat tumor‐bearing mice to further clarify the role of NK cells in tumor growth and infiltration. Transfer of activated NK cells in T, B and NK knock‐out NOG mice showed significant inhibition of tumor and ascites formation as well as infiltration. T, B and NK knock‐out NOG mice treated with activated NK cells rejected the tumor cells to a similar extent as T and B knock‐out NOD/SCID mice.

Natural killer cells kill target cells by various mechanisms. One way is by the release of cytoplasmic granules − complex organelles that combine specialized storage and secretory functions with the generic degradative functions of lysosomes. These granules contain a number of proteins, such as perforins and granzymes, which lyse target cells. Increased perforin and granzyme expression in activated NK cells was significantly correlated with inhibition of tumor growth and metastasis in the NOG mouse model. Perforin‐ and granzyme‐mediated apoptosis is the principal pathway used by NK cells to eliminate tumor and virus‐infected cells.( 53 ) Studies in perforin‐deficient mice have revealed that this protein is required for most NK‐cell cytotoxicity.(54)

In summary, NK knock‐out NOG mice were very efficient in the formation of primary tumors and organ infiltration. These results indicate that activated human NK cells prevent tumor growth and infiltration in NOG mice. Finally, our results suggest that NK cells play a critical role in tumor growth and infiltration, and that activated NK cells could be a promising immunotherapeutic strategy against cancer or viral infection either alone or in combination with conventional therapy. The reproducible growth behavior and preservation of characteristic features of PEL cells also suggest that the NOG mouse model system described in the present study may provide a novel opportunity to understand and investigate the mechanism of pathogenesis and malignant cell growth of PEL.

Acknowledgments

We thank K. Ohba of the Department of Molecular Virology, S. Ichinose of the Instrumental Analysis Research Center and S. Endo of the Animal Research Center, Tokyo Medical and Dental University for their advice and assistance with the experiments. We also thank Y. Sato of the National Institute of Infectious Diseases for her excellent technical assistance. This work was supported by grants from the Ministry of Education, Science and Culture; the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare; and Human Health Science of Japan.

References

- 1. Jaffe ES, Harris NL, Stein H, Vardiman JW, eds. World Health Organization Classification of Tumors, Pathology and Genetics of Tumors of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. Lyon, France: IARC Press, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gaidano G, Carbone A. Primary effusion lymphoma: a liquid phase lymphoma of fluid‐filled body cavities. Adv Cancer Res 2001; 80: 115–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cesarman E, Knowles DM. The role of Kaposi's sarcoma‐associated herpesvirus (KSHV/HHV‐8) in lymphoproliferative diseases. Semin Cancer Biol 1999; 9: 165–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Klein U, Gloghini A, Gaidano G et al. Gene expression profile analysis of AIDS‐related primary effusion lymphoma (PEL) suggests a plasmablastic derivation and identifies PEL‐specific transcripts. Blood 2003; 102: 4115–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cesarman E, Chang Y, Moore PS, Said JW, Knowles DM. Kaposi's sarcoma‐associated herpesvirus‐like DNA sequences in AIDS‐related body‐cavity‐based lymphomas. N Engl J Med 1995; 332: 1186–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Horenstein MG, Nador RG, Chadburn A et al. Epstein–Barr virus latent gene expression in primary effusion lymphomas containing Kaposi's sarcoma‐associated herpesvirus/human herpesvirus‐8. Blood 1997; 90: 1186–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nador RG, Cesarman E, Chadburn A et al. Primary effusion lymphoma: a distinct clinicopathologic entity associated with the Kaposi's sarcoma‐associated herpes virus. Blood 1996; 88: 645–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Schmidt M, Deschner EE, Thaler HT, Clemments L, Good RA. Gastrointestinal cancer studies in the human to nude mouse heterotransplant system. Gastroenterology 1977; 72: 829–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bosma GC, Custer RP, Bosma MJ. A severe combined immunodeficiency mutation in the mouse. Nature 1983; 301: 527–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Schuler W, Bosma MJ. Nature of the scid defect: a defective VDJ recombinase system. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 1989; 152: 55–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kamel‐Reid S, Letarte M, Sirard C et al. A model of human acute lymphoblastic leukemia in immune‐deficient SCID mice. Science 1989; 246: 1597–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mosier DE, Gulizia RJ, Baird SM, Wilson DB. Transfer of a functional human immune system to mice with severe combined immunodeficiency. Nature 1988; 335: 256–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ito M, Hiramatsu H, Kobayashi K et al. NOD/SCID/γcnull mouse: An excellent recipient mouse model for engraftment of human cells. Blood 2002; 100: 3175–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dorshkind K, Pollack SB, Bosma MJ, Phillips RA. Natural killer (NK) cells are present in mice with severe combined immunodeficiency (scid). J Immunol 1985; 134: 3798–801. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Feuer G, Stewart SA, Baird SM, Lee F, Feuer R, Chen ISY. Potential role of natural killer cells in controlling tumorigenesis by human T‐cell leukemia Viruses. J Virol 1994; 69: 1328–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Welsh RM. Regulation of virus infections by natural killer cells: a review. Nat Immun Cell Growth Regul 1986; 5: 169–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Trinchieri G. Biology of natural killer cells. Adv Immunol 1989; 47: 187–376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Moretta A. Natural killer cells and dendritic cells: rendezvous in abused tissues. Nat Rev Immunol 2002; 2: 957–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Raulet DH. Interplay of natural killer cells and their receptors with the adaptive immune response. Nat Immunol 2004; 5: 996–1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Karre K, Ljungger HG, Piontek G, Kiessling R. Selective rejection of H‐2‐deficient lymphoma variants suggests alternative immune defense strategy. Nature 1986; 319: 675–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pena J, Alonso C, Solana R, Serrano R, Carracedo J, Ramirez R. Natural killer susceptibility is independent of HLA class I antigen expression on the cell lines obtained from human solid tumors. Eur J Immunol 1990; 20: 2445–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Litwin V, Gumperz J, Parham P, Philips JH, Lanier LL. Specificity of HLA class I antigen recognition by human NK clones: evidence for clonal heterogeneity, protection by self and non‐self alleles, and influence of the target cell type. J Exp Med 1993; 178: 1321–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Imai K, Matsuyama S, Miyake S, Suga K, Nakachi K. Natural cytotoxic activity of peripheral‐blood lymphocytes and cancer incidence: an 11‐year follow‐up study of a general population. Lancet 2000; 356: 1795–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ullum H, Gotzsche PC, Victor J, Dickmeiss E, Skinhoj P, Pedersen BK. Defective natural immunity: an early manifestation of human immunodeficiency virus infection. J Exp Med 1995; 182: 789–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ahmad R, Menezes J. Defective killing activity against gp120/41‐expressing human erythroleukaemic K562 cell line by monocytes and natural killer cells from HIV‐infected individuals. AIDS 1996; 10: 143–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Scott‐Algara D, Paul P. NK cells and HIV infection: lessons from other viruses. Curr Mol Med 2002; 2: 757–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bonaparte MI, Barker E. Inability of natural killer cells to destroy autologous HIV‐infected T lymphocytes. AIDS 2003; 17: 487–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sirianni MC, Libi F, Campagna M et al. Downregulation of the major histocompatibility complex class I molecules by human herpesvirus type 8 and impaired natural killer cell activity in primary effusion lymphoma development. Br J Haematol 2005; 130: 92–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sirianni MC, Vincenzi L, Topino S et al. NK cell activity controls human herpesvirus 8 latent infection and is restored upon highly active antiretroviral therapy in AIDS patients with regressing Kaposi's sarcoma. Eur J Immunol 2002; 32: 2711–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lanier LL. NK cell receptors. Annu Rev Immunol 1998; 16: 356–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Moretta A, Bottino C, Mingari MC, Biassoni R, Moretta L. What is a natural killer cell? Nat Immunol 2002; 3: 6–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Koo GC, Dumont FJ, Tutt M, Hackett J Jr, Kumar V. The NK‐1.1(–) mouse: a model to study differentiation of murine NK cells. J Immunol 1986; 137: 3742–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Smyth MJ, Crowe NY, Godfrey DI. NK cells and NKT cells collaborate in host protection from methylcholanthrene‐induced fibrosarcoma. Int Immunol 2001; 13: 459–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Smyth MJ, Godfery DI, Trapani JA. A fresh look at tumor immunosurveillance and immunotherapy. Nature 2001; 2: 293–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Dewan MZ, Terashima K, Taruishi M et al. Rapid tumor formation of human T‐cell leukemia virus type 1‐infected cell lines in novel NOD‐SCID/γcnull mice: suppression by an inhibitor against NF‐κB. J Virol 2003; 77: 5286–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Dewan MZ, Uchihara JN, Terashima K et al. Efficient intervention of growth and infiltration of primary adult T‐cell leukemia cells by an HIV protease inhibitor, ritonavir. Blood 2006; 107: 716–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Renne R, Zhong W, Herndier B et al. Lytic growth of Kaposi's sarcoma‐associated herpesvirus (human herpesvirus 8) in culture. Nat Med 1996; 2: 342–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Katano H, Hoshino Y, Morishita Y et al. Establishing and characterizing a CD30‐positive cell line harboring HHV‐8 from a primary effusion lymphoma. J Med Virol 1999; 58: 394–401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Katano H, Sato Y, Kurata T, Mori S, Sata T. High expression of HHV‐8‐encoded ORF73 protein in spindle‐shaped cells of Kaposi's sarcoma. Am J Pathol 1999; 155: 47–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Dorshkind K, Pollack SB, Bosma MJ, Phillips RA. Natural killer (NK) cells are present in mice with severe combined immunodeficiency (scid). J Immunol 1985; 134: 3798–801. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Visonneau S, Cesano A, Torosian MH, Miller EJ, Santoli D. Growth characteristics and metastatic properties of human breast cancer xenografts in immunodeficient mice. Am J Pathol 1998; 152: 1299–311. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Cavacini LA, Giles‐Komar J, Kennel M, Quinn A. Effect of immunosuppressive therapy on cytolytic activity of immunodeficient mice: implications for xenogeneic transplantation. Cell Immunol 1992; 144: 296–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hochman PS, Cudkowicz G, Dausset J. Decline of natural killer cell activity in sublethally irradiated mice. J Natl Cancer Inst 1978; 61: 265–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Huang YW, Richardson JA, Tong AW, Zhang BQ, Stone MJ, Vitetta ES. Disseminated growth of a human multiple myeloma cell line in mice with severe combined immunodeficiency disease. Cancer Res 1993; 53: 1392–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lapidot T, Sirard C, Vormoor J et al. A cell initiating human acute myeloid leukaemia after transplantation into SCID mice. Nature 1994; 367: 645–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Taghian A, Budach W, Zietman A, Freeman J, Gioioso D, Suit HD. Quantitative comparison between the transplantability of human and murine tumors into the brain of NCr/Sed‐nu/nu nude and severe combined immunodeficient mice. Cancer Res 1993; 53: 5018–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Tanaka T, Tsudo M, Karasuyama H et al. Novel monoclonal antibody against murine IL‐2 receptor beta‐chain: Characterization of receptor expression in normal lymphoid cells and EL‐4 cells. J Immunol 1991; 147: 2222–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Noguchi M, Yi H, Rosenblatt HM et al. Interleukin‐2 receptor gamma chain mutation results in X‐linked severe combined immunodeficiency in humans. Cell 1993; 73: 147–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Puck JM, Deschenes SM, Porter JC et al. The interleukin‐2 receptor gamma chain maps to Xq13.1 and is mutated in X‐linked severe combined immunodeficiency, SCIDX1. Hum Mol Genet 1993; 2: 1099–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Welsh RM. Regulation of virus infections by natural killer cells: a review. Nat Immun Cell Growth Regul 1986; 5: 169–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Whiteside TL, Herberman RB. Role of human natural killer cells in health and disease. Clin Diagn Laboratory Immunol 1994; 1: 125–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Whiteside TL, Vujanovic NL, Herberman RB. Natural killer cells and tumor therapy. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 1998; 230: 221–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Trapani JA, Davis J, Sutton VR, Smyth MJ. Proapoptotic functions of cytotoxic lymphocyte granule constituents in vitro and in vivo . Curr Opin Immunol 2000; 12: 323–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]