Abstract

Transfection of the mouse Fut1 and Fut2, and human FUT1 genes into human ovarian carcinoma‐derived RMG‐1 cells resulted in 20–30‐fold increases in cellular α1,2‐fucosyltransferase activity, and in alteration of the glycolipid composition, including not only fucosylated products, but also precursor glycolipids. Although globo‐series glycolipids were not significantly affected by the transfection, the major glycolipids belonging to the lacto‐series type 1 chain family in RMG‐1 cells and the transfectants were the Lc4Cer, Lewis a (Le)a and Leb, and H‐1 glycolipids, respectively, suggesting that fucosylation of Lc4Cer to the H‐1 glycolipid prevents the further modification of Lc4Cer to Lea and Leb in the transfectants. Also, the lacto‐series type 2 chains in RMG‐1 cells were LeX, NeuAc‐nLc4Cer and NeuAc‐LeX, and those in the transfectants were LeX and LeY, indicating that the sialylation of nLc4Cer and LeX is restricted by increased fucosylation of LeX. As a result, the amount of sialic acid released by sialidase from the transfectants decreased to 70% of that from RMG‐1 cells, and several membrane‐mediated phenomena, such as the cell‐to‐cell interaction between cancer cells and mesothelial cells, and the cell viability in the presence of an anticancer drug, 5‐fluorouracil, for the transfectants was found to be increased in comparison to that for RMG‐1 cells. These findings indicate that cell surface carbohydrates are involved in the biological properties, including cell‐to‐cell adhesion and drug resistance, of cancer cells. (Cancer Sci 2005; 96: 26 –31)

The glycocalyx layer of mammalian cells consists of glycolipids, glycoproteins and proteoglycans, the carbohydrate structures of which are known to change in association with cellular differentiation and transformation, and to be involved in the histoblood group antigens and several carbohydrate‐mediated functions. (1) Because transformation‐associated alteration of carbohydrates occurs frequently and dramatically in several types of cancers, mainly due to the aberrant expression of glycosyltransferases, carbohydrate‐specific antibodies have been successfully applied for the clinical diagnosis of cancer patients, such as that against sialyl lacto‐N‐fucopentaose (sialyl Lewis a) as a ligand for selectin for predicting the metastatic potential, 2 , 3 , 4 and those against Leb, LeY and H antigens for determining the grade of dysplasia and the malignancy of colorectal carcinomas. 5 , 6 Modification of the galactose at the non‐reducing terminal of the Lewis carbohydrate by α1,2‐fucosyltransferase has been shown to result in the reduced adhesive and metastatic properties of pancreatic cancer cells, due to the inhibition of sialylation or sulfation at position 3 of galactose to form the selectin ligand, (7) indicating that expression of LeY or Leb competes with that of sialylated or sulfated Le‐structures.

Although the involvement of the sialyl Le structure in the metastatic potential has been clearly demonstrated through the application of carbohydrate‐specific antibodies as probes in the above experiments, there has been no report concerning the detailed carbohydrate structures in cancer cells manipulated by means of gene transfer. Because the synthesis of carbohydrate chains occurs through the sequential addition of a monosaccharide, the transfection of a gene does not always yield the same end products or the same carbohydrate composition. Consequently, quantitative analysis of carbohydrates in cells after transfection of a glycosyltransferase gene is required to elucidate the functional significance of carbohydrates in cancer cells. Because the concentrations of individual carbohydrate structures of glycolipids can be precisely determined by thin‐layer chromatography (TLC)‐immunostaining with carbohydrate‐specific antibodies, glycolipids are anticipated to provide useful information about any alteration of carbohydrate structures on gene transfer. Through the application of TLC‐immunostaining, the authors characterized the glycolipid composition of ovarian carcinoma‐derived RMG‐1 cells before and after transfection of the fucosyltransferase gene, and compared several cell biological properties between RMG‐1 cells and the transfectants.

Materials and Methods

Materials. Glycolipids were purified from various sources in our laboratory: GlcCer, LacCer, Gb3Cer, Gb4Cer, GM3, IV3NeuAc‐nLc4Cer and IV3Fuc‐Lc4Cer from human erythrocytes, Lc4Cer, Lea and Leb from human meconium, and LeX and LeY from rectal carcinoma tissue. nLc4Cer and Lc3Cer were prepared from IV3NeuAc‐nLc4Cer with sialidase (Arthrobacter ureafaciense), and from nLc4Cer with β‐galactosidase (Diplococus pneumoniae). 8 , 9 Human monoclonal anti‐Lc4Cer (HMST‐1) (10) and mouse monoclonal anti‐Leb plus LeY (11) antibodies were established in the authors’ laboratory. Monoclonal antibodies against H‐1, LeX (NCC‐LU‐279) and LeY (NCC‐ST‐433 and H18A), and nLc4Cer (H‐11) were kindly donated by Dr S. Hirohashi, National Cancer Center (Tokyo, Japan), and Dr T. Taki, Otsuka Pharmaceutical Company (Tokushima, Japan), respectively. Monoclonal anti‐LeX (73–30), antisialyl Lea (2D3), and sialyl LeX (KM‐93) were obtained from Seikagaku (Tokyo, Japan).

Ovarian carcinoma‐derived cells. A cell line, RMG‐1, was established from the tumor tissue of a patient with clear cell carcinomas of the ovary, (12) and was cultured in Ham's F12 medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS).

Fucosyltransferase genes. The cDNA of mouse and human α1,2‐fucosyltransferases, that is, mouse Fut1 (MFUT‐I) and Fut2 (MFUT‐II) (GenBank accession numbers AF113533 and AF06472), and human FUT1 (GenBank accession number M35531), were prepared from mouse intestine mRNA and a human brain genome library (Funakoshi, Tokyo), respectively, according to the procedure reported previously. 13 , 14 The cDNA were constructed in the Kpn1 and EcoR1 sites of mammalian expression vector pcDNA3.1 (pcDNA3.1‐Fut1, pcDNA3.1‐Fut2 and pcDNA3.1‐FUT1), and were then transfected into RMG‐1 cells using a Cellphect Transfection Kit (Pharmacia, Piscataway, NJ, USA). The cells transfected with the vector alone were used as a control.

α1,2‐Fucosyltransferase activity. α1,2‐Fucosyltransferase activity was determined using a glycolipid, that is, Gg4Cer, Lc4Cer, nLc4Cer, Lea, LeX or sialyl Lea, as the substrate, and with the homogenates of RMG‐1 cells and the transfectants as enzyme sources. The standard assay mixture comprised 38 nM glycolipid, 20 mM MnCl2, 1% Triton X‐100, 50 mM cacodylate‐HCl (pH 5.8), 0.37 µM GDP‐[14C]fucose (270.2 mCi/mmole), and 80–400 µg enzyme protein, in a final volume of 100 µL. After incubation at 37°C for 1 h, the reaction was ended with 300 µL of chloroform/methanol (2:1, v/v), and then the products in the lower phase were separated, using TLC with chloroform/methanol/0.5% CaCl2 (55:45:10, v/v). 14 , 15 The radioactivity incorporated into the glycolipids was determined using a liquid scintillation counter (Tri‐Carb 1500; Packard, Foster City, CA, USA).

Quantitative determination of glycolipids. The RMG‐1 cells that were transfected with pcDNA3.1, pcDNA3.1‐Fut2 or pcDNA3.1‐FUT1 were lyophilized, and then extraction of their lipids was carried out by incubating the lyophilized cells with chloroform/methanol/water (20:10:1, 10:20:1 and 1:1:0, v/v/v). The lipid extracts, corresponding to 0.1 mg of dry weight, were chromatographed on a plastic‐coated TLC plate with chloroform/methanol/0.5% CaCl2 in water (55:45:10, v/v), and the spots were seen by staining with orcinol‐H2SO4 reagent and by immunostaining with carbohydrate‐specific antibodies, as described above. (16) Known amounts of the respective glycolipids were run on the same plates to obtain standard curves, and the density of the spots was measured at 500 nm using TLC‐densitometry (CS‐9000; Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). The lower limits for detection with orcinol reagent and immunostaining were 0.1 µg and 0.5 ng, respectively, and the standard curves were linear up to 2 µg and 100 ng, respectively. Detection of Lc4Cer and nLc4Cer, which co‐migrated to the same position on TLC, was carried out by immunostaining of the neutral glycolipids with anti‐Lc4Cer (HMST‐1) and anti‐nLc4Cer (H‐11) antibodies, and that of sialylated derivatives by immunostaining of the acidic glycolipids after treatment of the TLC‐plate with Vibrio cholerae sialidase. (11)

Determination of sialic acid. The cells (1 × 109) that were liberated by treatment with trypsin were suspended in 200 µL of phosphate‐buffered saline containing 200 munits of neuraminidase (V. cholerae), and then incubated at 37°C for 2 h. After centrifugation at 500 g for 5 min, the quantity of sialic acid in the supernatant was determined by means of the thiobarbituric acid reaction. (8)

Cellular properties. The RMG‐1 cells and the transfectants (1 × 104) were cultured in Ham's F12 medium supplemented with 1% FCS in the presence of 0.1 mg/mL, 0.5 mg/mL, 1.0 mg/mL and 5 mg/mL of 5‐fluorouracil (5‐FU; Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA), and then the cell numbers were determined after liberation of the cells with trypsin, 6 days after cultivation. To characterize the adhesive property to mesothelial cells, the RMG‐1 cells and the transfectants were labeled with 5(6)‐carboxyfluorescein diacetate, (12) and then added to enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) plates bearing a mesothelial cell monolayer derived from the lesser omentum by treatment with dispase (Sigma) at 2.0 × 105 cells in 0.1 mL of Ham's F12 medium containing 1% FCS. After incubation at 37°C for 20 min, the wells were filled with the same medium, sealed with tape, inverted and centrifuged at 150 g for 5 min. After removal of the non‐adherent cells, the fluorescence intensity of each well was measured using an ELISA reader (Corona, Tokyo, Japan) at an excitation wavelength of 496 nm and an emission wavelength of 520 nm.

Results

Fucosyltransferase activity toward glycolipid substrates. As shown in Table 1, the fucosyltransferases encoded by the Fut1, Fut2 and FUT1 genes exhibited the ability to transfer α‐L‐fucose to the terminal galactose of glycolipids of the lacto‐series, but not to sialyl LeX, indicating that sialic acid at position 3 of the terminal galactose inhibits the fucosyltransferase activity at position 2. On comparison of the specific activities toward lacto‐series glycolipids, the activities of the Fut2 and FUT1 enzymes toward the lacto‐series type 1 chain were found to be higher than those toward the type 2 chain, which was fucosylated by the Fut1 enzyme with higher specific activity than by the Fut2 and FUT1 enzymes (Table 1). Thus, although the amino acid sequence of the human FUT1 enzyme was similar to that of the mouse Fut1 enzyme (78.4%), its substrate specificity was similar to that of the mouse Fut2 enzyme.

Table 1.

Specific activity of fucosyltransferases on several glycolipids in RMG‐1 cells and the transfectants

| Glycolipid | RMG‐1 | Transfectants | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pcDNA3.1 | pcDNA3.1‐Fut1 | pcDNA3.1‐Fut2 | pcDNA3.1‐FUT1 | ||

| Gg4Cer | 2.9 ± 0.2 | 2.8 ± 0.6 | 44.8 ± 7.3 | 91.7 ± 12.8 | 73.9 ± 10.3 |

| nLc4Cer | – | – | 10.8 ± 0.2 | 43.6 ± 3.4 | 38.7 ± 5.5 |

| Lc4Cer | – | – | 6.2 ± 0.1 | 60.5 ± 4.8 | 54.8 ± 5.0 |

| III3Fuc‐nLc4Cer (LeX) | – | – | 22.3 ± 3.5 | 13.6 ± 0.5 | 26.3 ± 3.2 |

| III4Fuc‐Lc4Cer (Lea) | – | – | 12.0 ± 2.7 | 20.2 ± 2.5 | 30.4 ± 4.1 |

| IV3NeuAc, III3Fuc‐nLc4Cer (sialyl Lea) | – | – | – | – | – |

Specific activity was expressed as pmol/mg protein/h. –, not detected.

Change in the glycolipid composition on transfection of fucosyltransferase genes. As reported previously, (15) the glycolipids with terminal galactose in ovarian carcinoma‐derived RMG‐1 cells were Lc4Cer and LeX, which were expected to be converted to H‐1 and LeY glycolipids, respectively, on transfection of the fucosyltransferase gene. Accordingly, selection of transfectants, which were preselected for resistance to G418, was carried out by immunostaining of the cells with anti‐LeY antibody after limiting dilution of the transfectants, and the resultant cell clones of transfectants with a stronger intensity of immunostaining than that of RMG‐1 cells were used for analyses of the fucosyltransferase activity and glycolipid composition. As shown in Figure 1 and Table 2, the concentrations of globo‐series glycolipids in the transfectants were not significantly different from those in RMG‐1 cells. However, those of lacto‐series glycolipids, including H‐1 glycolipid and LeY, were affected by the transfection.

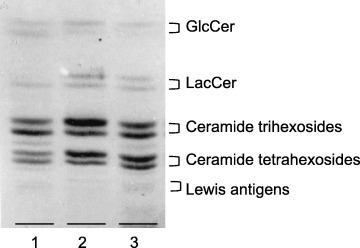

Figure 1.

Thin‐layer chromatography (TLC) of neutral glycolipids from RMG‐1 cells and the transfectant. Glycolipids, corresponding to 0.5 mg of dry cells, were chromatographed on a TLC plate with chloroform/methanol/water (65:35:8, v/v/v) and the spots were seen with orcinol‐H2SO4 reagent. 1, RMG‐1; 2, pcDNA3.1‐FUT1‐RMG‐1; 3, pcDNA3.1‐Fut2‐RMG‐1.

Table 2.

Concentration of glycolipids with short carbohydrate chains and globoside in RMG‐1 cells and the transfectants (µg/mg of dry cells)

| RMG‐1 | Transfectants | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| pcDNA3.1‐Fut2 | pcDNA3.1‐FUT1 | ||

| GlcCer | 0.24 ± 0.05 | 0.18 ± 0.01 | 0.21 ± 0.05 |

| LacCer | 0.18 ± 0.03 | 0.26 ± 0.02 | 0.32 ± 0.02 |

| Gb3Cer | 1.42 ± 0.02 | 1.53 ± 0.05 | 2.02 ± 0.02 |

| Gb4Cer | 1.12 ± 0.01 | 1.48 ± 0.04 | 1.55 ± 0.02 |

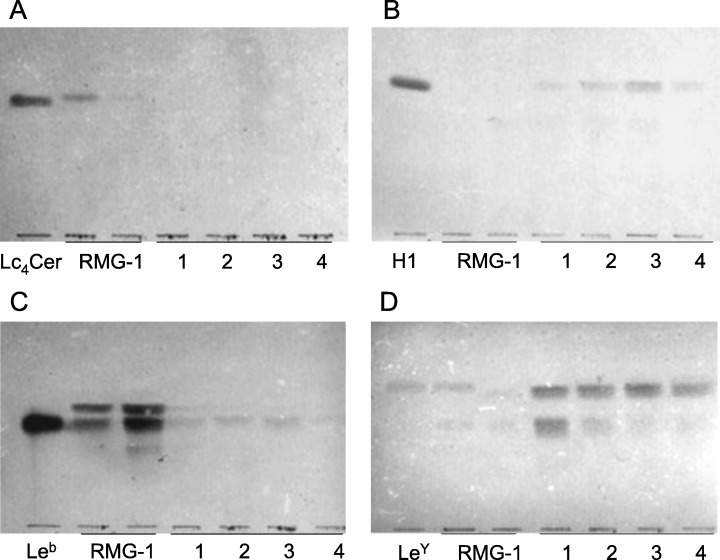

As shown in Figure 2A, Lc4Cer was detected in RMG‐1 cells, but not in any cell clones that were transfected with the fucosyltransferase gene, and H‐1 glycolipid, as a fucosylated product, was compensatorily present in the transfectants, but not in RMG‐1 cells (Fig. 2B), indicating that Lc4Cer is scarcely fucosylated in RMG‐1 cells, but is virtually completely converted to H‐1 glycolipid in the transfectants. Similarly, the concentration of LeY was elevated by more than approximately 10‐fold in the transfectants compared with the concentration in the original RMG‐1 cells (Fig. 2D).

Figure 2.

Thin‐layer chromatography (TLC)‐immunostaining of glycolipids from RMG‐1 cells and the transfectants. The antibodies used for detection were (A) anti‐Lc4Cer, (B) anti‐H1, (C) anti‐Leb, and (D) anti‐LeY. 1, pcDNA3.1‐Fut1‐RMG‐1; 2, pcDNA3.1‐Fut2‐RMG‐1; 3 and 4, pcDNA3.1‐FUT1‐RMG‐1.

In support of the increased concentration of fucosylated glycolipids in the transfectants, fucosyltransferase activity with Gg4Cer as the substrate in the transfectants was demonstrated to be 20–30‐fold that in the original RMG‐1 and empty vector‐transfected cells, indicating that the increased concentration of the LeY and H‐1 antigens in the gene‐transfected cells was due to the enhanced activity of fucosyltransferase (Table 1). However, Leb, which is a structural isomer of LeY and was detected in RMG‐1 cells, was significantly reduced in the transfectants, as shown in Figure 1C. The opposite effect of the increased activity of fucosyltransferase on the concentration of Leb and LeY was thought to depend on the concentration of the precursor glycolipids, Lea and LeX, respectively. IV3NeuAc‐nLc4Cer and NeuAc‐LeX in the transfectants were also reduced in concentration compared with RMG‐1 cells, such as that of Leb.

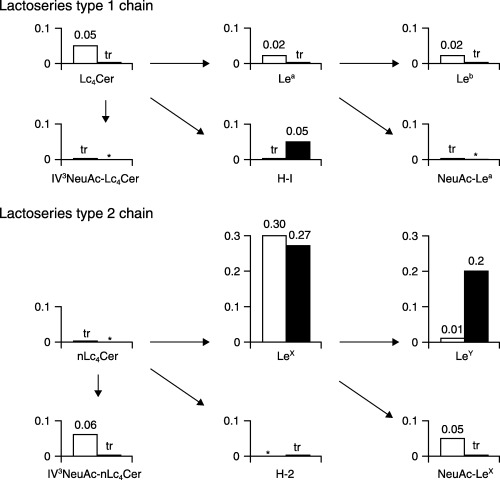

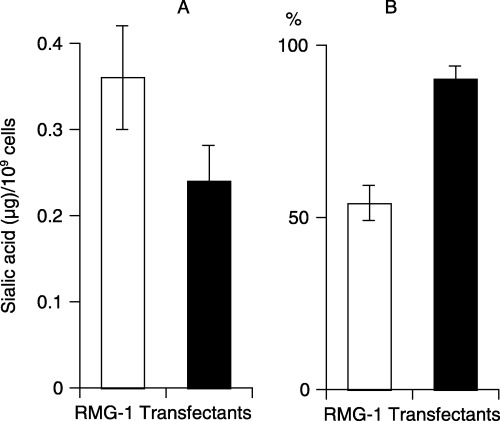

As shown in Figure 3, among the glycolipids that belong to the lacto‐series type 1 chain family, only H‐1 glycolipid was present at a concentration of 0.05 µg/mg of dry cells in the transfectants, although the original RMG‐1 cells contained 0.02–0.05 µg of Lc4Cer, Lea and Leb per milligram of dry cells, suggesting that fucosylation of Lc4Cer to H‐1 glycolipid prevented further modification of Lc4Cer to Leb in the transfectants. In contrast, among the glycolipids with lacto‐series type 2 chains in RMG‐1 cells, that is, LeX, NeuAc‐nLc4Cer and NeuAc‐LeX, sialylated derivatives completely disappeared, and LeX and LeY were present in the transfectants at concentrations of >0.2 µg/mg of dry cells, indicating that sialylation of nLc4Cer and LeX in RMG‐1 cells is restricted by increased fucosylation of LeX to LeY. Consequently, the quantity of sialic acid released from the transfectants on treatment with V. cholerae sialidase decreased to 70% of that from the original RMG‐1 cells, although the alteration of carbohydrate structures in the glycoproteins was obscure (Fig. 4A).

Figure 3.

Concentrations of (□) lacto‐series glycolipids in RMG‐1 cells and (▪) the transfectants with pcDNA3.1‐FUT1. The concentrations are expressed as micrograms of glycolipids per milligram of dry cells, and are the means for three experiments. tr, trace amount (<0.005 µg/mg of dry cells); *not detected.

Figure 4.

Quantity of (□) sialic acid released from RMG‐1 cells and (▪) the transfectants with pcDNA3.1‐FUT1 on treatment with (A) Vibrio cholerae sialidase, and (B) adhesion of the cells to a mesothelial cell monolayer.

Change in the cellular properties on transfection of the fucosyltransferase genes. On comparison of the cellular properties of RMG‐1 and the transfectants, several membrane‐mediated phenomena were found to be altered, probably due to the modification of glycoconjugates as a result of the increased activity of fucosyltransferase, as described above. First, after dispersion of the cells by treatment with trypsin, the transfectants aggregated more readily than the original RMG‐1 cells (data not shown). Second, the rate of binding to mesothelial cells for the transfectants was significantly elevated compared with that for the original cells (Fig. 4B). Third, the viability of the transfectants in the medium containing the anticancer drug, 5‐FU, was significantly elevated compared with that of RMG‐1 cells (Table 3), this probably being attributable to the alteration of the membrane permeability through the drug channels with modified carbohydrate structures.

Table 3.

Cell numbers after cultivation in the medium containing 5‐fluorouracil

| Cells | No. of cells (×104/mL) 1 µg 5FU/mL | 0.1 µg 5FU/mL |

|---|---|---|

| RMG‐1 | 0.4 ± 0.2 | 0.9 ± 0.2 |

| RMG‐1 with pcDNA3.1 | 0.4 ± 0.3 | 0.7 ± 0.1 |

| RMG‐1 with pcDNA3.1‐Fut2 | 2.4 ± 07 | 2.2 ± 1.1 |

| RMG‐1 with pcDNA3.1‐FUT1 | 2.4 ± 0.5 | 2.1 ± 1.0 |

Cells (1 × 104) were cultured in Ham's F12 medium containing 1% fetal calf serum in the presence of 5‐fluorouracil (5FU) for 7 days.

Discussion

Manipulation of cell surface carbohydrates using the gene‐transfection technique with sugar transferase genes is widely applied to elucidate the functional significance of transformation‐associated carbohydrate antigens, and the resultant cells with a promising modification are frequently examined using qualitative analysis of expression of the respective carbohydrate structures with carbohydrate‐specific probes, such as monoclonal antibodies and lectins. Almost all of the gene‐transfer experiments carried out so far have involved qualitative analysis, mainly due to difficulties in the quantitation of individual carbohydrate structures, particularly in the glycoproteins, and no detailed description of a carbohydrate composition that has been modified by gene transfer has appeared in the past. Accordingly, the authors first compared the glycolipid composition of RMG‐1 cells and transfectants. As has been clearly shown in this paper, enhancement of the activity of fucosyltransferase at the terminal step of glycolipid synthesis brought about alterations in the composition, not only of the respective fucosylated glycolipids, but also of the surrounding structures related to the substrate glycolipids. For example, Lc4Cer, Lea and Leb were the major glycolipids belonging to the lacto‐series type 1 chain family in the original RMG‐1 cells, but H‐1 was the predominant glycolipid in the transfectants in which the fucosylation of Lc4Cer into H‐1 glycolipid was almost complete, because Lc4Cer was absent from the transfectants, suggesting that the decreased expression of Lea and Leb in the transfectants was probably due to interception of the substrate, Lc4Cer, for synthesis of the H‐1 glycolipid through its fucosylation. In contrast, the glycolipids that contained lacto‐series type 2 chains and showed concentrations of >0.01 µg/mg of dry cells in RMG‐1 cells were LeX, LeY, IV3NeuAc‐nLc4Cer and NeuAc‐LeX, but those in the transfectants were LeX and LeY, and the rate of fucosylation of LeX to LeY in the transfectants was enhanced compared with that in RMG‐1 cells, being 3.2% for RMG‐1 cells and 42.6% for the transfectants. An increase in the metabolic rate for the formation of LeY was thought to cause the reduced syntheses of IV3NeuAc‐nLc4Cer and NeuAc‐LeX. (7)

Thus, an increased fucosyltransferase activity was found to modify the metabolism of substrate lacto‐series glycolipids, leading to a greatly altered composition without any effect on unrelated pathways, such as that for globo‐series glycolipids. The difference in the mode of modification between the lacto‐series types 1 and 2 chains was thought to be due to the different metabolic rates for the substrates, Lea and LeX, respectively, the synthetic potential of the former being lower than that in the latter. Consequently, synthesis of Lea in the transfectants seemed to be reduced to a trace level through enhanced fucosylation of the substrate, Lc4Cer, while the enhanced fucosylation of LeX led to a more active synthesis of LeX, resulting in a reduced quantity of nLc4Cer, followed by a decreased quantity of IV3NeuAc‐nLc4Cer. It was evident that a change in the synthetic potential at a single step in the multitransferase cascade caused this distinct glycolipid composition. It is probable that the carbohydrate structures in the glycoproteins should be modified in the same way as for the glycolipids.

By substituting the non‐reducing terminal galactose with fucose, the quantity of sialic acid that was liberated from the transfectants by neuraminidase was reduced to 70% of the level for RMG‐1 cells, and the reduced amount of sialic acid‐dependent negative charge, as well as LeX and LeY, seemed to be attributable to the enhanced adhesion to mesothelial cells. 17 , 18

With regard to resistance against anticancer drugs, similar results to the authors’ have been obtained for rat colon carcinoma cells transfected with either the α1,2‐fucosyltransferase gene or its antisense sequence; the H‐2 antigen, which was increased in the transfectants, was reported to be involved in the drug resistance. (19) However, our results did not reveal the possible involvement of the H‐2 antigen (IV2Fuc‐nLc4Cer), the concentration of which was not increased by transfection. Because the basic carbohydrate structures of rat cells are clearly different from those of human cells, a specific carbohydrate structure seemed not to be involved in the resistance to anticancer drugs. It is probable that a distinct change in the concentration of sialic acid‐containing glycolipids on transfection might be implicated in drug resistance, through regulation of the activity of the transporter protein, because sphingolipids are known to play a role by regulating physiological proteins in the membrane microdomain. (20) An experiment on transfection with the sialyltransferase and sulfotransferase genes is now in progress in the authors’ laboratory to characterize the relationship between carbohydrate structure and drug resistance.

References

- 1. Roseman S. Reflections on glycobiology. J Biol Chem 2001; 276: 41527–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Koprowski H, Herlyn M, Steplewski Z, Sears HF. Specific antigen in serum of patients with colon carcinoma. Science 1981; 212: 53–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bevilacqua MP, Stengelin S, Gimbrone MA Jr, Seed B. Endothelial leukocyte adhesion molecule 1. an inducible receptor for neutrophils related to complement regulatory proteins and lectins. Science 1989; 243: 1160–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ohmori K, Kanda K, Mitsuoka C, Kanamori A, Kurata‐Miura K, Sasaki K, Nishi T, Tamatani T, Kannagi R. P‐ and E‐selectins recognize sialyl 6‐sulfo Lewis X, the recently identified 1‐selectin ligand. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2000; 278: 90–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Goupille C, Marionneau S, Bureau V, Hallouin F, Meichenin M, Rocher J, Le Pendu J. α1,2Fucosyltransferase increases resistance to apoptosis of rat colon carcinoma cells. Glycobiology 2000: 10: 375–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Baldus SE, Hanisch FG, Putz C, Flucke U, Monig SP, Schneider PM, Thiele J, Holscher AH, Dienes HP. Immunoreactivity of Lewis blood group and mucin peptide core antigens: correlations with grade of dysplasia and malignant transformation in the colorectal adenoma‐carcinoma sequence. Histol Histopathol 2002; 17: 191–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Aubert M, Panicot L, Crotte C, Gibier P, Lombardo D, Sadoulet MO, Mas E. Restoration of α1,2‐fucosyltransferase activity decreases adhesive and metastatic properties of human pancreatic cancer cells. Cancer Res 2000; 60: 1449–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Iwamori M, Ohta Y, Uchida Y, Tsukada Y. Arthrobacter ureafaciens sialidase isoenzymes, L, M1 and M2, cleave fucosyl GM1. Glycoconj J 1997; 14: 67–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kojima K, Iwamori M, Takasaki S, Kubushiro K, Nozawa S, Iizuka R, Nagai Y. Diplococcal beta‐galactosidase with a specificity reacting to beta 1–4 linkage but not to beta 1–3 linkage as a useful exoglycosidase for the structural elucidation of glycolipids. Anal Biochem 1987; 165: 465–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nozawa S, Narisawa S, Kojima K, Sakayori M, Iizuka R, Mochizuki H, Yamauchi T, Iwamori M, Nagai Y. Human monoclonal antibody (HMST‐1) against lacto‐series type 1 chain and expression of the chain in uterine endometrial cancers. Cancer Res 1989; 49: 6401–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Iwamori M, Sakayori M, Nozawa S, Yamamoto T, Yago M, Noguchi M, Nagai Y. Monoclonal antibody‐defined antigen of human uterine endometrial carcinomas is Leb . J Biochem (Tokyo) 1989; 105: 718–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kishikawa T, Sakamoto M, Ino Y, Kubushiro K, Nozawa S, Hirohashi S. Two distinct patterns of peritoneal involvement shown by in vitro and in vivo ovarian cancer dissemination models. Invasion Metastasis 1995; 15: 11–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ishiwata I, Ishiwata C, Soma M, Akagi H, Hiyama H, Nakaguchi T, Ono I, Hashimoto H, Ishikawa H. Presence of human papillomavirus genome in human tumor cell lines and cultured cells. Anal Quant Cytol Histol 1991; 13: 363–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lin B, Hayashi Y, Saito M, Sakakibara Y, Yanagisawa M, Iwamori M. GDP‐fucose. β‐galactoside α1,2‐fucosyltransferase, MFUT‐II, and not MFUT‐I or ‐III, is induced in a restricted region of the digestive tract of germ‐free mice by host–microbe interactions and cycloheximide. Biochim Biophys Acta 2000; 1487: 275–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lin B, Saito M, Sakakibara Y, Hayashi Y, Yanagisawa M, Iwamori M. Characterization of three members of murine α1,2‐fucosyltransferases. change in the expression of the Se gene in the intestine of mice after administration of microbes. Arch Biochem Biophys 2001; 388: 207–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Takehara K, Kubushiro K, Kiguchi K, Ishiwata I, Tsukazaki K, Nozawa S, Iwamori M. Expression of glycolipids bearing Lewis phenotypes in tissues and cultured cells of human gynecological cancers. Jpn J Cancer Res 2002; 93: 1129–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kiguchi K, Iwamori M, Mochizuki Y et al. Selection of human ovarian carcinoma cells with high dissemination potential by repeated passage of the cells in vivo into nude mice, and involvement of Le(x)‐determinant in the dissemination potential. Jpn J Cancer Res 1998; 89: 923–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cao Z, Zhao Z, Mohan R, Alroy J, Stanley P, Panjwani N. Role of the Lewis(x) glycan determinant in corneal epithelial cell adhesion and differentiation. J Biol Chem 2001; 276: 21714–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cordel S, Goupille C, Hallouin F, Meflah K, Le Pendu J. Role for alpha1,2‐fucosyltransferase and histo‐blood group antigen H type 2 in resistance of rat colon carcinoma cells to 5‐fluorouracil. Int J Cancer 2000; 85: 142–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Belton RJ Jr, Adams NL, Foltz KR. Isolation and characterization of sea urchin egg lipid rafts and their possible function during fertilization. Mol Reprod Dev 2001; 59: 294–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]