Abstract

Strong HLA‐DR antigen expression on cancer cells relates to better prognosis of colorectal cancer patients, although the precise mechanism is controversial. From an immunological point of view, HLA‐DR antigen, induced by interferon (IFN)‐γ, is required for tumor‐associated antigen recognition by CD4+ T cells. For instance, as reported previously, the expression of HLA‐DR antigen in normal colorectal epithelium immediately adjacent to cancer coincided significantly with the existence of IFN‐γ mRNA in the tissue. From another aspect, IFN‐γ has been revealed to suppress c‐myc expression in vivo through a stat1‐dependent mechanism, which is important for cell growth, cell cycle and chromosome instability. In the present study, strong HLA‐DR‐positive expression on cancer cells was significantly related to better prognosis for colorectal cancer patients. High IFN‐γ mRNA expression in situ indicated significantly less activation of c‐myc mRNA expression. Further, HLA‐DR antigen expression in cancer cells, as well as Dukes stages, was an independent factor for better long‐term survival by multivariate analysis. Taken together, IFN‐γ, which induces HLA‐DR antigens on the cell surface, also suppresses c‐myc expression in situ, and is a possible non‐immunological mechanism involved in the better long‐term survival of colorectal cancer patients. (Cancer Sci 2006; 97: 57– 63)

HLA‐DR antigen is required for tumor‐associated antigen recognition by CD4+ T cells.( 1 , 2 , 3 ) HLA‐DR antigen, scarcely expressed on the normal colorectal epithelium,( 4 ) is expressed on the colorectal epithelium of inflammatory bowel disease and on cancer cells by interferon (IFN)‐γ with or without tumor necrosis factor (TNF)‐α.( 5 , 6 , 7 ) As reported previously, the expression of HLA‐DR antigen in cancer and normal epithelium immediately adjacent to cancer is a useful marker of IFN‐γ mRNA expression in the tissues.( 6 ) In fact, strong HLA‐DR antigen expression on cancer cells closely relates to a more favorable prognosis for colorectal cancer patients,( 8 , 9 ) but the immunological and non‐immunological mechanisms are still obscure. So far, two possible mechanisms of tumor cell elimination have been discussed in relation to HLA‐DR antigen expression on cancer cells. The first mechanism, one of immunological action, is that of tumor growth inhibition by cytokines produced by CD4+ T cells. CD4+ T cells are classified into two subgroups: Th1 and Th2 cells. Th1 cells produce interleukin (IL)‐2 and IFN‐γ whereas Th2 cells produce IL‐4, IL‐5 and IL‐10.( 10 ) It is considered that HLA‐DR antigen expression on cancer cells stimulates CD4+ Th1 cells and natural killer (NK) cells by presenting tumor‐associated antigens with IFN‐γ production, which then leads to improved prognosis.

The second mechanism of tumor growth inhibition, one of non‐immunological activity, is due to the direct strong antitumor action of IFN‐γ.( 11 ) Recently, IFN‐γ has been reported to suppress c‐myc gene expression via a stat1‐dependent pathway.( 12 , 13 ) c‐myc regulates the cell cycle, proliferation, genomic instability and tumorigenesis. Regression of established tumors due to inactivation of the c‐myc transgene in beta cells was associated with rapid proliferative arrest, differentiation and apoptosis of tumor cells.( 14 ) In addition, relatively low c‐myc‐expressing cells among high c‐myc‐expressing cells led to cell death in a Drosophila model.( 15 ) Thus, the effect of IFN‐γ on c‐myc expression in situ cannot be ignored as it may reveal a mechanism of tumor suppression.

In the present study, the influence of IFN‐γ on c‐myc mRNA expression was investigated by examining its in situ expression. c‐myc expression was significantly lower when IFN‐γ RNA expression was high in cancer tissues. In total, c‐myc suppression by IFN‐γ represents a possible non‐immunological mechanism that functions for the better prognosis of strong HLA‐DR antigen‐expressing colorectal cancers.

Materials and methods

Patients and tissue samples

Fifty‐one patients with pathologically proven adenocarcinoma (all primary cases), hospitalized at the Department of Frontier Surgery, Chiba University Hospital (Chiba, Japan) between 1991 and 1994, were investigated in this study. The patients consisted of 33 men (64.7%) and 18 women (35.3%) aged 61.2 ± 11.5 years (range 35–84 years). The cases were classified according to Dukes classification: Dukes A, 10 cases; Dukes B, 15 cases; Dukes C, 12 cases; Dukes D, 14 cases. The majority of tumors (36/51, 70.6%) were located at the sigmoid colon or rectum, and 92.2% (47/51) were well or moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma. Average tumor size was 5.7 ± 2.5 cm in diameter (Table 1). These proportions were fairly similar to larger series reported in Japan.( 16 ) No patient had received blood transfusion, radiotherapy or chemotherapy within 6 months of the start of this study.

Table 1.

HLA‐DR antigen expression and clinicopathological and biological characteristics of colorectal cancer patients

| Characteristic | Total number | HLA‐DR expression | P‐value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | Negative | Positive | ||

| Age (years) | |||||

| <50 | 6 | 11.7 | 3 | 3 | 0.29 |

| 50≤, <60 | 17 | 33.3 | 14 | 3 | NS |

| 60≤, <70 | 14 | 27.5 | 10 | 4 | |

| ≥70 | 13 | 25.5 | 7 | 6 | |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 33 | 64.7 | 22 | 11 | 0.68 |

| Female | 18 | 35.3 | 13 | 5 | NS |

| Dukes stage | |||||

| A | 10 | 19.6 | 8 | 2 | |

| B | 15 | 29.4 | 7 | 8 | 0.12 |

| C | 12 | 23.5 | 8 | 4 | NS |

| D | 14 | 27.5 | 12 | 2 | |

| Tumor site | |||||

| Right colon | 12 | 23.6 | 7 | 5 | 0.15 |

| Left colon | 22 | 43.1 | 12 | 5 | |

| Rectum | 17 | 33.3 | 10 | 7 | NS |

| Histology | |||||

| Differentiated | 47 | 92.2 | 33 | 14 | 0.40 |

| Undifferentiated | 4 | 7.8 | 2 | 2 | NS |

| Tumor size | |||||

| <6 cm | 27 | 52.9 | 17 | 10 | 0.36 |

| ≥6 cm | 24 | 47.1 | 18 | 6 | NS |

| Prognosis | |||||

| Dead | 27 | 52.9 | 22 | 5 | 0.036 |

| Alive | 24 | 47.1 | 13 | 11 | |

| IFN‐γ expression | |||||

| Positive | 25 | 49.0 | 15 | 10 | cf. |

| Negative | 26 | 51.0 | 20 | 6 | 0.19 |

| Total | 51 | 100 | 35 | 16 | |

Sets of samples containing cancer tissues and non‐cancer tissues 5–10 cm remote from the tumors were obtained from each case for DNA or RNA extraction. Surgically excised samples of cancer and non‐cancer tissues were also embedded in optimal cutting temperature compound (Tissue‐Tek®, Sakura, Tokyo, Japan), frozen in liquid nitrogen immediately after excision, and stored at −80°C until used. Written informed consent was obtained from each patient prior to surgery.

Immunohistochemical procedures for HLA‐DR antigen expression

Immunohistochemical procedures for HLA‐DR antigen expression detection were described previously.( 6 ) Briefly, air‐dried 4‐µm cryostat sections on slides were fixed in cold acetone for 20 min and washed with phosphate‐buffered saline (PBS) for 5 min. After pretreatment with normal rabbit serum, the sections were incubated with mouse monoclonal anti‐HLA‐DR antibody, HU‐20, for 1 h. After washing with PBS, the sections were incubated with biotinylated antimouse immunoglobulin as secondary antibody. The sections were then incubated with horseradish peroxidase‐conjugated streptavidin–biotin complex for 30 min. Peroxidase activity was visualized using DAB solution (20 mg of 3,3′‐diaminobenzidine, 65 mg of sodium azide, and 10 mL of 30% H2O2 in 100 mL of 0.05 M Tris buffer at pH 7.6). Hematoxylin was used for nuclear counterstaining. Cases with more than 10% of cancer cells strongly stained in the membrane or cytoplasm with HU‐20 specific for HLA‐DR antigen were regarded as positive.

IFN‐γ mRNA detection by RT‐PCR following Southern blot analysis

IFN‐γ mRNA detection was carried out as described previously.( 6 ) Total RNA was extracted from excised cancer and non‐cancer colorectal tissues using the guanidium/cesium chloride procedure. DNase treatment was carried out before reverse transcription. IFN‐γ mRNA was converted to cDNA by reverse transcription and amplified with suitable primers by reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT‐PCR). Consecutive Southern blot analysis was carried out with a PCR‐amplified IFN‐γ DNA fragment as probe DNA. Each experiment was performed at least twice to confirm the results. To confirm the accuracy of PCR‐amplified bands in the agarose gel, each PCR product was digested with restriction enzyme DraI (New England BioLabs, Beverly, MA, USA) and hybridized with the PCR‐amplified IFN‐γ cDNA fragment.

c‐myc mRNA detection by northern blot analysis

c‐myc mRNA was detected as reported previously.( 17 ) Briefly, 10 ìg of total RNA was electrophoresed on a 1% agarose gel prepared in gel containing 2.2 M formaldehyde. The RNA was transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane and cross‐linked (Stratalinker 1800; Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, USA). Membranes were prehybridized and hybridized with a random‐priming 32P‐labeled probe of the human c‐myc gene (0.4‐kb fragment containing part of exon 2). After the c‐myc signals were detected, the same filters were washed off and rehybridized with glyceraldehyde‐3‐phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) for standardization of mRNA. The levels of mRNA expression were measured by densitometric scanning, and the relative expression levels were calculated as c‐myc mRNA divided by GAPDH mRNA. These were indicated as T in cancer and N in non‐cancer tissues.

RT‐PCR for HLA‐DR mRNA

Total RNA were extracted from tumor and non‐tumor epithelial tissues as described previously.( 6 ) cDNA was synthesized from total RNA with the first strand cDNA Synthesis Kit for RT‐PCR (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). Using the cDNA as a template, HLA‐DRA or HLA‐DRB1 cDNA was amplified with suitable primer sets by RT‐PCR. The HLA‐DRA primers were: forward, 5′‐GGAGTCCCTGTGCTAGGATT‐3′; reverse, 5′‐CTCCTGTGGTGACAGGTTTT‐3′. The HLA‐DRB1 primers were: forward, 5′‐GCGGTTCCTGGACAGATAC‐3′; reverse, 5′‐GGCTGGGTCTTTGAAGGATA‐3′. For a control, GAPDH cDNA was amplified. The PCR product was loaded on a 1.0% agarose gel (Promega, Madison, WI, USA).

Statistics

Comparisons between unpaired groups were made using the Mann–Whitney U‐test. Survival probabilities were calculated using the product limit method of Kaplan and Meier. Differences between groups were tested using the Wilcoxon test. Fisher's exact probability test was applied to determine the significance between two groups. The influence of each clinical and pathological variance on survival was assessed by the Cox's proportional hazards model with backward stepwise procedure. All statistical analyses were carried out using the SPSS program release 6.1.3 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA), and all P‐values that were two‐sided at 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

HLA‐DR antigen expression on cancer cells differed from adjacent non‐cancer epithelium

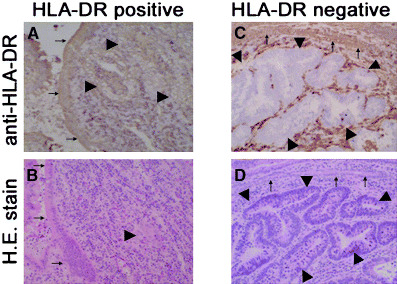

IFN‐γ activates transcription of class II transactivator (CIITA) through the stat1 signaling pathway that induces HLA‐DR antigen expression on the cell surface.( 18 ) In some cancer cells, this IFN‐γ signaling pathway for HLA‐DR antigen induction is disturbed due to epigenetic inactivation, methylation or histone deacetylation in the promoter region of the CIITA gene.( 19 ) The actual decreased expression of HLA‐DR antigen expression on cancer cells is shown in Fig. 1C (arrowheads), but the immediately adjacent non‐cancer epithelium strongly expressed HLA‐DR antigen in each case (Fig. 1, arrows). This result supports the notion that the HLA‐DR antigen expression mechanism on cancer cells is impaired or is different from that on the non‐cancer epithelium immediately adjacent to cancer cells.

Figure 1.

Representative HLA‐DR positive and negative expression in colorectal cancer tissues. (A) Strong HLA‐DR expression is seen in both cancer (arrowheads) and immediately adjacent non‐cancer epithelium (arrows). (B) Hematoxylin and eosin staining corresponding to part A. (C) HLA‐DR expression is completely suppressed in a cancer cluster (arrowheads), whereas strong HLA‐DR expression is observed on non‐cancer epithelium (arrowheads). (D) Hematoxylin and eosin stain corresponding to part C.

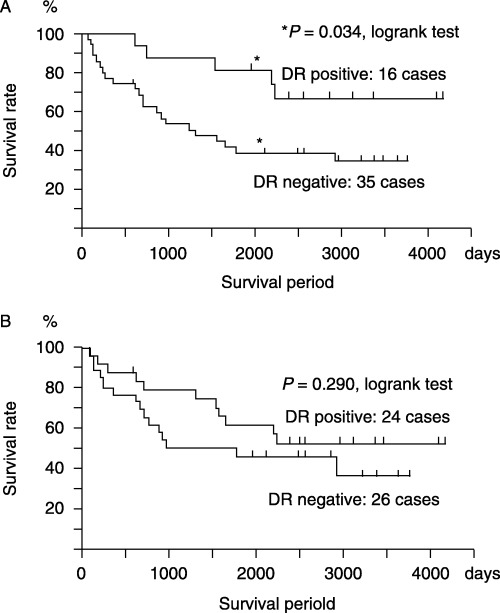

Strong HLA‐DR antigen expression on cancer cells, but not on adjacent non‐cancer cells, is related to better long‐term survival of colorectal cancer patients

Recent studies have revealed that HLA‐DR antigen‐transfected cancer cells or epithelial cells acquire an antigen‐presenting function that is removed by the immune response.( 1 , 20 ) Interestingly, HLA‐DR antigen expression on cancer cells (Fig. 2A), but not on the non‐cancer epithelium immediately adjacent to cancer cells (Fig. 2B), is significantly related to a better prognosis for colorectal cancer patients. This result shows that, although HLA‐DR antigen expression on adjacent non‐cancer epithelium reflects the IFN‐γ expression in situ, the decreased expression of HLA‐DR antigen on cancer cells is more significant for tumor progression in terms of the immune response.

Figure 2.

HLA‐DR antigen expression on cancer cells, but not on non‐cancer epithelium, is significant for a better prognosis of colorectal cancer patients. (A) More than 10‐year survival rate of patients with HLA‐DR‐positive cancer cells (16 cases; 67% survival) is significantly better than that of patients with HLA‐DR‐negative cancer cells (35 cases; 34% survival) (P = 0.034, log‐rank test). Survival probabilities were calculated by the product limit method of Kaplan and Meier. (B) There was no significant difference when prognoses were compared between HLA‐DR antigen expression on adjacent non‐cancer epithelium.

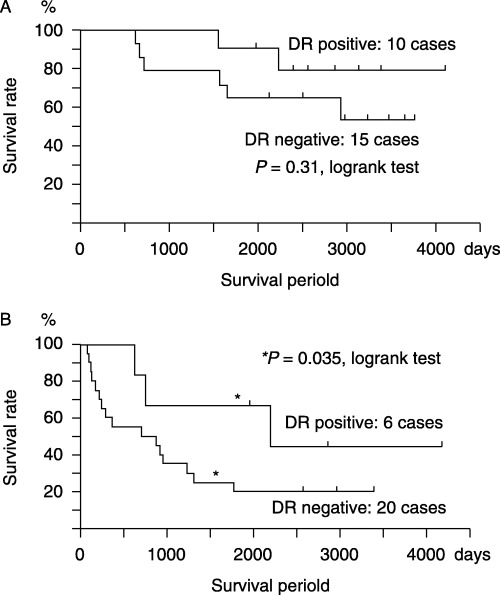

HLA‐DR antigen expression on cancer cells is a significant indicator for the prognosis of Dukes C and D patients (with lymph node or organ metastasis)

We then examined the association between HLA‐DR antigen expression on cancer cells and patient prognosis in relation to the clinical stages of cancer progression. Strong HLA‐DR expression on cancer cells was related to better prognosis in both Dukes A and B (without lymph node or organ metastasis) and C and D stages (with lymph node or organ metastasis). In Dukes A and B stages, there was no significant difference of survival rate between the HLA‐DR‐positive and HLA‐DR‐negative groups, whereas in Dukes C and D stages, strong HLA‐DR expression on cancer cells was significantly related to a better prognosis of up to 2200 days compared to the prognosis of patients with weak HLA‐DR expression (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

Strong HLA‐DR expression in cancer cells is associated with better prognosis in both (A) Dukes A and B, and (B) C and D classifications. A combination of Dukes stages and HLA‐DR antigen expression on cancer cells is more predictive than Dukes stages alone in Dukes C and D stages.

Univariate and multivariate analysis with Cox's proportional hazards model.

To evaluate the significance of HLA‐DR antigen expression for patient prognosis, univariate and multivariate analyses with the backward stepwise Cox's proportional hazards model were carried out (Table 2). Factors examined were sex (male vs female), age (<60 years vs ≥60 years), Dukes stages (Dukes A and B vs C and D), HLA‐DR antigen expression of cancer cells (<10% vs ≥10%), histologic type (differentiated vs undifferentiated), tumor site (colon vs rectum), and tumor size (<6 cm vs ≥6 cm). Multivariate analysis with the backward stepwise procedure revealed that HLA‐DR antigen expression on cancer cells and Dukes stages were only independent prognostic factors for the colorectal cancer patients examined.

Table 2.

Univariate and multivariate analysis of prognostic factors of colorectal cancer patients

| Parameter | P‐value | Hazard ratio | 95% confidence interval |

|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate | |||

| Gender (male vs female) | 0.21 | ||

| Age (<60 years vs ≥60 years) | 0.27 | ||

| Stage (Dukes A, B vs C, D) | 0.00 | ||

| HLA‐DR antigen (negative vs positive) | 0.03 | ||

| Histology (differentiated vs undifferentiated) | 0.46 | ||

| Site (colon vs rectum) | 0.37 | ||

| Size (<6 cm vs ≥6 cm) | 0.53 | ||

| Multivariate | |||

| Stage (Dukes A and B vs C and D) | 0.03 | 3.62 | 1.56–8.39 |

| HLA‐DR antigen (negative vs positive) | 0.11 | 0.45 | 0.17–1.19 |

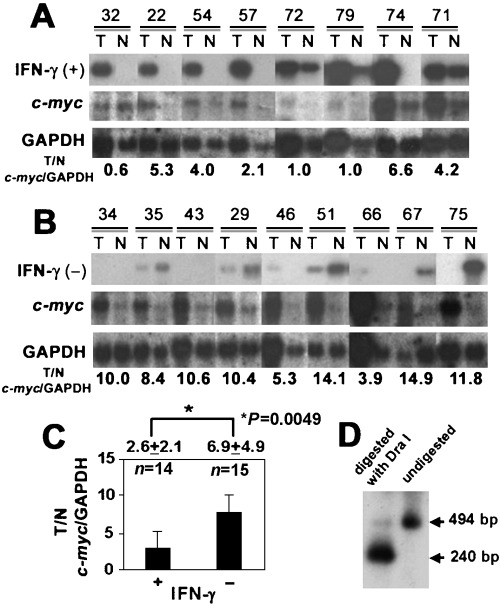

c‐myc mRNA expression was significantly suppressed when high IFN‐γ expression was observed in cancer tissues

Table 1 shows no significant difference in clinicopathological and biological characteristics between negative and positive groups of HLA‐DR expression in cancer cells. The percentage of cancer cells expressing HLA‐DR antigen gradually decreased along with tumor development; for Dukes A and B it was 60.0% (15/25 cases) whereas Dukes C and D dropped to 23.1% (6/26 cases). Instead of futile attempts to induce HLA‐DR antigen on advanced cancer cells, clarifying the possible role of IFN‐γ in this induction might offer some advantages. Recent studies have revealed that IFN‐γ suppresses c‐myc expression in a stat1‐dependent manner.( 12 , 13 ) Of particular interest was the fact that c‐myc mRNA expression was significantly less activated in cancer tissues where IFN‐γ was highly expressed (Fig. 4A–C). The PCR band of IFN‐γ was digested with suitable restriction enzyme as expected size (Fig. 4D). These results indicate that IFN‐γ in cancer tissues has an accompanying function of suppressing c‐myc expression in situ, besides inducing HLA‐DR antigen on the cancer cell surface. Although further studies will be necessary, c‐myc gene suppression by IFN‐γin situ as a non‐immunological action also needs to be taken into account when considering the mechanism of why strong HLA‐DR antigen expression on cancer cells is related to a more favorable prognosis in colorectal cancer patients.

Figure 4.

Cancer tissues and non‐cancer tissues are described as (T) and (N), respectively. c‐myc expression in the cancer tissues (T) is significantly suppressed where interferon (IFN)‐γ mRNA is detected. (A) c‐myc mRNA expression was less activated when IFN‐γ was strongly positive in the tissues. (B) c‐myc mRNA expression was more activated when IFN‐γ was negatively expressed in the tissues. (C) Intensity of the bands was quantified by NIH image. c‐myc mRNA expression/glyceraldehyde‐3‐phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) mRNA in IFN‐γ‐positive cancer tissues (n = 14, 2.8 ± 3.2) was significantly lower (P‐value = 0.02) than that of IFN‐γ‐negative cancer tissues (n = 15, 5.8 ± 4.4). (D) The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) band of IFN‐γ was digested with a suitable restriction enzyme (DraI) to confirm the accuracy of the PCR product.

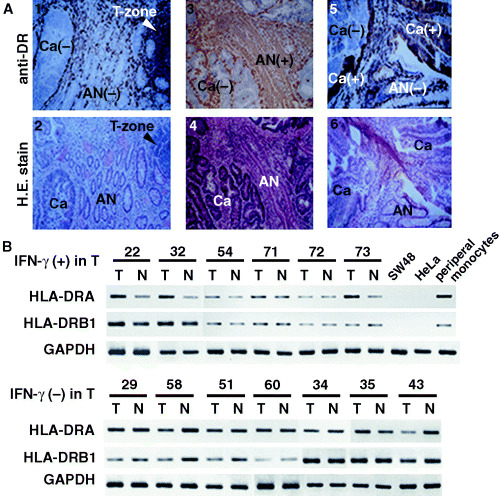

HLA‐DR antigen mRNA expression was activated in the tumor tissues where IFN‐γ was apparently detected in the tissues

Para‐cortical T cells (Fig. 5; T‐zone of panels 1 and 2 with arrow) express strong HLA‐DR expression, as do infiltrating T cells. Panel 5 (Fig. 5A) shows heterogenous expression of HLA‐DR antigen on cancer cells. These results suggest that HLA‐DR antigen is expressed in both cancer cells and T cells, at least in some patients. HLA‐DR antigen mRNA expression was examined by RT‐PCR targeting HLA‐DRA (α‐chain) and HLA‐DRB1 (β‐chain). HLA‐DR antigen mRNA was activated in the tumor tissues where IFN‐γ was detected highly. Both HLA‐DRA and HLA‐DRB1 mRNA expression of IFN‐γ‐positive tumor tissues (Fig. 5B) were more activated than those of IFN‐γ‐negative tumor tissues (Fig. 5B). Case 73 was IFN‐γ‐positive in tumor tissues, whereas cases 58 and 60 were IFN‐γ‐negative (Fig. 5B and data not shown).

Figure 5.

(A) Representative HLA‐DR antigen expression on cancer (Ca) and normal epithelium immediately adjacent to the cancer (AN) of three different patients. Panels 1 and 2, 3 and 4, 5 and 6 indicate the same fields of HLA‐DR antigen expression and hematoxylin and eosin staining, respectively. Para‐cortical T cells (T‐zone; panels 1 and 2) show strong HLA‐DR expression as well as infiltrating T cells. Panel 5 shows heterogenous expression of HLA‐DR antigen on cancer cells. This immunohistochemical examination suggests that HLA‐DR antigen is expressed in both cancer cells and T cells, at least in some colorectal cancer patients. (B) Both HLA‐DRA and HLA‐DRB1 mRNA expression were detected by reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction in tumor tissues (T) and non‐tumor tissues (N). Glyceraldehyde‐3‐phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) mRNA was used as an internal control. HLA‐DRA mRNA expression in T was apparently activated in cases. IFN‐γ mRNA was highly expressed in T (upper panel: cases 22, 32, 54 and 73), whereas it was relatively less activated in cases where IFN‐γ was negative in T (lower panel). In addition, HLA‐DRB1 expression in T was less activated than in N in cases where IFN‐γ was negative in T (lower panel: cases 29, 58, 51 and 43), whereas expression levels were the same as in normal tissues in IFN‐γ‐positive cases (upper panel). Note that SW48 (human colorectal cancer cell line) and HeLa (human cervical squamous cancer cell line) express low levels of HLA‐DRA and HLA‐DRB1 mRNA, whereas peripheral blood monocytes express both HLA‐DRA and HLA‐DRB1 mRNA. Case numbers are the same as those shown in Fig. 4.

Discussion

Recent studies have pointed out the relationship between HLA‐DR antigen expression on cancer cells and prognosis, but the precise mechanism remains to be elucidated.( 8 , 9 , 21 , 22 ) In the present study, multivariate analysis revealed that strong HLA‐DR antigen expression on cancer cells, but not on adjacent non‐cancer cells, is an independent factor for better prognosis of colorectal cancer patients, to much the same extent as Dukes stages.

Several studies have so far focused mainly on the immunological aspects of how HLA‐DR antigen expression on cancer cells relates to better prognosis of colorectal cancer patients. Although there was no significant relationship between HLA‐DR antigen expression on cancer cells alone and IFN‐γ mRNA expression in situ (Table 1[cf.], P = 0.19, χ2‐test), IFN‐γ mRNA expression was higher in situ where HLA‐DR antigen was expressed strongly on both cancer cells and adjacent non‐cancer epithelium.( 6 ) Thus, the strong HLA‐DR antigen expression on cancer cells together with the adjacent non‐cancer epithelium more closely associates with the activation of IFN‐γin situ. HLA‐DR antigen expression on cancer cells activates CD4+ Th1 cells and NK cells by presenting tumor‐associated antigens, resulting in the production of antitumor cytokines such as IFN‐γ.( 10 , 23 ) Nonetheless, the number of tumor‐infiltrating lymphocytes and prognosis are not necessarily correlated in colorectal cancer.( 2 , 24 , 25 ) In addition, the mechanism of HLA‐DR antigen induction by IFN‐γ on cancer cells can be disturbed by epigenetic changes in the promoter region of CIITA.( 19 ) In some colorectal cancer patients, HLA‐DR antigen does not express on cancer cells even in the tissues where IFN‐γ is highly expressed.( 6 ) These represent the possible tumor escape mechanisms of cancer cells from immunosurveillance in terms of impaired T‐cell activation through the IFN‐γ signaling pathway.( 26 )

In contrast, IFN‐γ exerts strong antitumor inhibitory activity as a non‐immunological function.( 11 , 26 , 27 ) For instance, IFN‐γ suppresses c‐myc expression through a stat1‐dependent pathway in vivo, which is critical for tumor cell growth, proliferation and progression.( 12 ) In addition, as the overexpression of c‐myc is reported to be a poor prognostic factor in colorectal cancers and hematological malignancies,( 28 , 29 ) its suppression might inhibit tumor progression and improve prognosis. It has been shown that downregulation of the c‐myc gene leads to inhibition of tumor progression or to tumor cell differentiation to normal cells, resulting in tumor dormancy in a mouse model.( 14 , 30 ) Further analyses are required to evaluate the significant association between IFN‐γ mRNA expression and c‐myc mRNA suppression in colorectal cancer tissues, and postulate a non‐immunological mechanism for the better prognosis; however, the c‐myc gene seems to be a pivotal target of IFN‐γ for preventing tumor progression. In the present study, of major interest was the fact that c‐myc expression was significantly suppressed when IFN‐γ was highly expressed in situ in colorectal cancer (Fig. 4).

Taken together, strong HLA‐DR antigen expression in cancer cells, a favorable marker of the existence of IFN‐γin situ, may be associated with better prognosis of colorectal cancer patients not only by activating local immune response but also by suppressing c‐myc expression in situ as a non‐immunological action. Colorectal cancer serves as a good model for investigating the interaction between HLA‐DR expression and tumor progression.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by a Grant‐in‐Aid 16591292 to KM and the 21st Century Center of Excellence Program to TO from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture of Japan.

References

- 1. Armstrong TD, Clements VK, Ostrand‐Rosenberg S. Class II‐transfected tumor cells directly present endogenous antigen to CD4+ T cells in vitro and are APCs for tumor‐encoded antigens in vivo . J Immunother 1998; 21: 218–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dalerba P, Maccalli C, Casati C, Castelli C, Parmiani G. Immunology and immunotherapy of colorectal cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2003; 46: 33–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zeh HJ, Stavely‐O’Carroll K, Choti MA. Vaccines for colorectal cancer. Trends Mol Med 2001; 7: 307–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mayer L, Eisenhardt D, Salomon P, Bauer W, Plous R, Piccinini L. Expression of class II molecules on intestinal epithelial cells in humans. Differences between normal and inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 1991; 100: 3–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Satoh A, Toyota M, Ikeda H et al. Epigenetic inactivation of class II transactivator (CIITA) is associated with the absence of interferon‐gamma‐induced HLA‐DR expression in colorectal and gastric cancer cells. Oncogene 2004; 23: 8876–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Matsushita K, Takenouchi T, Kobayashi S et al. HLA‐DR antigen expression in colorectal carcinomas: influence of expression by IFN‐γin situ and its association with tumour progression. Br J Cancer 1996; 73: 644–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ishii N, Chiba M, Iizuka M, Horie Y, Masamune O. Induction of HLA‐DR antigen expression on human colonic epithelium by tumor necrosis factor‐α and interferon‐γ. Scand J Gastroenterol 1994; 29: 903–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lovig T, Andersen SN, Thorstensen L et al. Strong HLA‐DR expression in microsatellite stable carcinomas of the large bowel is associated with good prognosis. Br J Cancer 2002; 87: 756–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Andersen SN, Rognum TO, Lund E, Meling GI, Hauge S. Strong HLA‐DR expression in large bowel carcinomas is associated with good prognosis. Br J Cancer 1993; 68: 80–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cherwinski HM, Schumacher JH, Brown KD, Mosmann TR. Two types of mouse helper T cell clone. III. Further differences in lymphokine synthesis between Th1 and Th2 clones revealed by RNA hybridization, functionally monospecific bioassays, and monoclonal antibodies. J Exp Med 1987; 166: 1229–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dredge K, Marriott JB, Todryk SM, Dalgleish AG. Adjuvants and the promotion of Th1‐type cytokines in tumour immunotherapy. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2002; 51: 521–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ramana CV, Grammatikakis N, Chernov M et al. Regulation of c‐myc expression by IFN‐γ through Stat1‐dependent and ‐independent pathways. EMBO J 2000; 19: 263–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Carlberg AL, Moberg KH, Hall DJ. Tumor necrosis factor and gamma‐interferon repress transcription from the c‐myc P2 promoter by reducing E2F binding activity. Int J Oncol 1999; 15: 121–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pelengaris S, Khan M, Evan GI. Suppression of Myc‐induced apoptosis in beta cells exposes multiple oncogenic properties of Myc and triggers carcinogenic progression. Cell 2002; 109: 321–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Secombe J, Pierce SB, Eisenman RN. Myc: a weapon of mass destruction. Cell 2004; 117: 153–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Muto T, Kotake K, Koyama Y. Colorectal cancer statistics in Japan: data from JSCCR registration, 1974–1993. Int J Clin Oncol 2001; 6: 171–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Imaseki H, Hayashi H, Taira M et al. Expression of c‐myc oncogene in colorectal polyps as a biological marker for monitoring malignant potential. Cancer 1989; 64: 704–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Murphy SP, Choi JC, Holtz R. Regulation of major histocompatibility complex class II gene expression in trophoblast cells. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 2004; 2: 52–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kanaseki T, Ikeda H, Takamura Y et al. Histone deacetylation, but not hypermethylation, modifies class II transactivator and MHC class II gene expression in squamous cell carcinomas. J Immunol 2003; 170: 4980–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hershberg RM, Cho DH, Youakim A et al. Highly polarized HLA class II antigen processing and presentation by human intestinal epithelial cells. J Clin Invest 1998; 102: 792–803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Diederichsen AC, Hjelmborg JB, Christensen PB, Zeuthen J, Fenger C. Prognostic value of the CD4+/CD8+ ratio of tumour infiltrating lymphocytes in colorectal cancer and HLA‐DR expression on tumour cells. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2003; 52: 423–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zhang L, Conejo‐Garcia JR, Katsaros D et al. Intratumoral T cells, recurrence, and survival in epithelial ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med 2003; 348: 203–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Belardelli F. Role of interferons and other cytokines in the regulation of the immune response. Apmis 1995; 103: 161–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ishigami S, Natsugoe S, Tokuda K et al. CD3‐zetachain expression of intratumoral lymphocytes is closely related to survival in gastric carcinoma patients. Cancer 2002; 94: 1437–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Reichert TE, Scheuer C, Day R, Wagner W, Whiteside TL. The number of intratumoral dendritic cells and zeta‐chain expression in T cells as prognostic and survival biomarkers in patients with oral carcinoma. Cancer 2001; 91: 2136–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dunn GP, Bruce AT, Ikeda H, Old LJ, Schreiber RD. Cancer immunoediting: from immunosurveillance to tumor escape. Nat Immunol 2002; 3: 991–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ikeda H, Old LJ, Schreiber RD. The roles of IFN gamma in protection against tumor development and cancer immunoediting. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 2002; 13: 95–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sato K, Miyahara M, Saito T, Kobayashi M. c‐myc mRNA overexpression is associated with lymph node metastasis in colorectal cancer. Eur J Cancer 1994; 30A: 1113–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Nagy B, Lundan T, Larramendy ML et al. Abnormal expression of apoptosis‐related genes in haematological malignancies: overexpression of MYC is a poor prognostic sign in mantle cell lymphoma. Br J Haematol 2003; 120: 434–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Shachaf CM, Kopelman AM, Arvanitis C et al. MYC inactivation uncovers pluripotent differentiation and tumour dormancy in hepatocellular cancer. Nature 2004; 431: 1112–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]