Abstract

Dendritic cells (DC) are critical for priming adaptive immune responses to foreign antigens. However, the feasibility of harnessing these cells in vivo to optimize the antitumor effects has not been fully explored. The authors investigated a novel therapeutic approach that involves delivering synergistic signals that both recruit and expand DC populations at sites of intratumoral injection. More specifically, the authors examined whether the co‐administration of plasmids encoding the chemokine macrophage inflammatory protein‐3 alpha (pMIP3α) and plasmid encoding the granulocyte macrophage colony stimulating factor (pGM‐CSF; a DC‐specific growth factor) can recruit, expand and activate large numbers of DC at sites of intratumoral injection. It was found that the administration of pGM‐CSF and pMIP3α resulted in dramatic recruitment and expansion of DC at these sites and in draining lymph nodes. Furthermore, treatment with pGM‐CSF and pMIP3α generated the strongest MUC1‐associated CD8+ T‐cell immune responses in draining lymph nodes and in tumors, produced the greatest antitumor effects and enhanced survival rates more than pcDNA3.1, pGM‐CSF alone and pMIP3α alone. It was also found that pGM‐CSF plus pMIP3α generated the strongest MUC1‐associated CD4+ T‐cell immune responses in draining lymph nodes and in tumors. The findings of the present study suggest that the recruitment and activation of DC in vivo due to the synergistic actions of pGM‐CSF and pMIP3α presents a potentially feasible means of controlling immunogenic malignancies and provides a basis for the development of novel immunotherapeutic treatments. (Cancer Sci 2010; 101: 2341–2350)

Several studies have demonstrated the trafficking of dendritic cells (DC) from sites of antigen (Ag) capture to draining lymphoid organs.( 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 ) Immature DC capture tumor Ag, are activated, and then undergo extensive phenotypic and functional transformations under the influence of inflammatory stimuli. Mature DC subsequently migrate to T‐cell‐rich areas, such as the lymph nodes where they can present Ag to naive T cells and generate tumor‐specific immune responses.( 1 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 ) The DC also control the type of immunity by activating CD4+ T‐helper cells to release T‐helper type‐1 (Th1) or Th2 cytokines.( 10 ) Thus, the recruitment of DC to tumor sites provides a rational strategy for the induction of antitumor immune responses.

A variety of strategies have been devised to use DC to stimulate immunity against tumor Ag, based on this understanding of the central role played by DC in the initiation of immune responses. The majority of these strategies rely on the activation and maturation of DC ex vivo and their subsequent reinfusion to tumor‐bearing recipients after being pulsed with tumor Ag expressed as peptides, protein or nucleic acids.( 11 ) However, the ex vivo manipulation of DC is time consuming, costly, requires the use of numerous cytokines and exposes patients to infection. To avoid the manipulation of DC ex vivo, we investigated an approach based on the expanding, loading and activation of DC in vivo.

Immature DC express CCR6, the only known receptor of macrophage inflammatory protein‐3 alpha (MIP‐3α) (CCL20),( 12 , 13 ) and MIP‐3α triggers adaptive immunity by attracting immature DC to sites of inflammation. After antigen uptake, immature DC lose their responsiveness to MIP‐3α, strongly express CCR7, and are differentiated into mature DC. The mature DC migrate to lymph nodes in response to MIP‐3β (CCL19), a ligand of CCR7.( 14 ) Granulocyte macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM‐CSF) is one of the most potent, specific, long‐lasting inducers of antitumor systemic immunity,( 15 , 16 ) and mediates its effect by stimulating the differentiation and activation of antigen‐presenting cells (APC), such as dendritic cells and macrophages.( 17 , 18 ) The APC in turn, process and present tumor antigens to helper T cells and CTL cells, thus augmenting the immune response.( 19 , 20 ) Furthermore, GM‐CSF is particularly effective at generating systemic immunity against a number of poorly immunogenic tumors.( 21 , 22 , 23 ) Accordingly, we considered that these signals might exert synergistic effects. However, plasmid MIP‐3 alpha (pMIP3α) (DC‐specific chemotactic factor) and plasmid GM‐CSF (pGM‐CSF) (DC‐growth factor) combinations have not been previously investigated in an established MUC1 expressing–murine thymoma cell line.

In the present study, we attempted to increase the uptake of tumor Ag by DC in vivo by directing the circulating DC. To do so, we used MIP‐3α chemokine, a potent chemoattractant for a subset of DC in both humans and mice.( 24 , 25 ) This technique allowed us to determine if DC numbers at tumor sites critically determines the induction of antitumor immunity. We also used GM‐CSF (a growth factor) to activate tumoral DC and to evaluate the effects of the maturational states of these cells on the development of antitumor immunity. By co‐administering plasmid GM‐CSF (pGM‐CSF) and plasmid MIP‐3α (pMIP3α), we sought to explore the biology and the immune targets of each of these molecules in vivo.

In this study, we found that pGM‐CSF plus pMIP3α administration resulted in dramatic recruitment and expansion of DC at tumor sites and draining lymph nodes, and that it generated more MUC1‐associated CD8+ T‐cell immune responses in draining lymph nodes and in tumors, had a greater antitumor effect, and enhanced survival rates more than the other treatment regimens examined (pcDNA3.1, pGM‐CSF alone and pMIP3α alone). We also found that pGM‐CSF plus pMIP3α generated greater MUC1‐associated CD4+ T‐cell immune responses in draining lymph nodes and in tumors. Thus, our data suggest that co‐treatment with pGM‐CSF and pMIP3α offers a potentially feasible means of controlling MUC1‐associated malignancies. The clinical implications of this treatment are discussed.

Materials and Methods

Mice. Specific pathogen‐free 6‐week‐old female C56BL/6 mice were obtained from SLC Inc. (Hamamatsu, Japan). All experimental animals were housed under specific pathogen‐free conditions and handled in accordance with the guidelines issued by the Seoul National University Animal Research Committee.

Murine tumor cell line expressing hMUC1. The human pancreatic mucin‐1, hMUC1 (accession no. J05582), gene was cloned into the BamHI site of retroviral vector pLXIN (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA, USA). Packing cell line PA317 was transfected with the pLXIN‐muc1 construct using Lipofectamine (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and grown in 10% FBS‐supplemented DMEM containing G418. The most productive clone, as determined by RT‐PCR, was chosen and used to transduce the EL4 murine thymoma cell line, which is of the H‐2b MHC type. Transduced EL4 cells were cultured in 1 mg/mL G418‐containing DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS to establish stable cell lines expressing hMUC1, which were designated EL4/MUC1.

Generation of complementary DNA constructs and plasmid preparation. cDNA encoding GM‐CSF or MIP3α were obtained by RT‐PCR from inflamed mouse skin and cloned into the pcDNA3.1 expression vector (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), which contains a CMV promoter. Plasmid DNA harboring GM‐CSF, MIP3α and the empty plasmid vector were introduced into Escherichia coli DH5α competent cells. The DNA was prepared using endotoxin‐free Giga Prep columns (Qiagen, Chatsworth, CA, USA). The DNA was dissolved in endotoxin‐free buffer for storage.

Expression of pGM‐CSF and pMIP3α vector in vitro. EL4/MUC1 tumor cells (1 × 105) were transiently transfected with pcDNA3.1 (0.4 μg/μL), pGM‐CSF (0.4 μg/μL) and pMIP3α (0.4 μg/μL) vector using Lipofectamine reagents (Invitrogen). Two days after transfection, media supernatant samples were obtained. The presence of GM‐CSF or MIP3α was detected by ELISA (Endogen, Cambridge, MA, USA). Serial dilutions of known concentrations of purified recombinant mouse GM‐CSF or MIP3α were used to produce standard curves.

Expressions of pGM‐CSF and pMIP3α vector in vivo. EL4/MUC1 tumor cells (5 × 104 cells) were administered subcutaneously to C57BL/6 mice. After 10 days, tumors were injected intratumorally with pcDNA3.1 (100 μg/100 μL), pGM‐CSF (100 μg/100 μL) and pMIP3α (100 μg/100 μL) vector. Tumors were excised 3 days after these intratumoral injections. Total RNA of the tumor was extracted using Trizol reagents (Gibco BRL, Paisley, UK), and RT‐PCR products were generated from the mRNA template using pairs of primers specific for GM‐CSF or MIP3α. β‐actin was amplified using β‐actin‐specific primers as an RNA quality control. In addition, treated tumors were homogenized and treated with a protein inhibitor cocktail (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA). Homogenates were centrifuged in a high‐speed microcentrifuge for 10 min and analyzed for total protein contents using a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay reagent kit (Bio‐Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Levels of GM‐CSF and MIP3α in supernatants were determined by ELISA (Endogen). Cytokine results were normalized versus total protein concentrations for each tumor, and results are expressed as picograms per milligram of total protein.

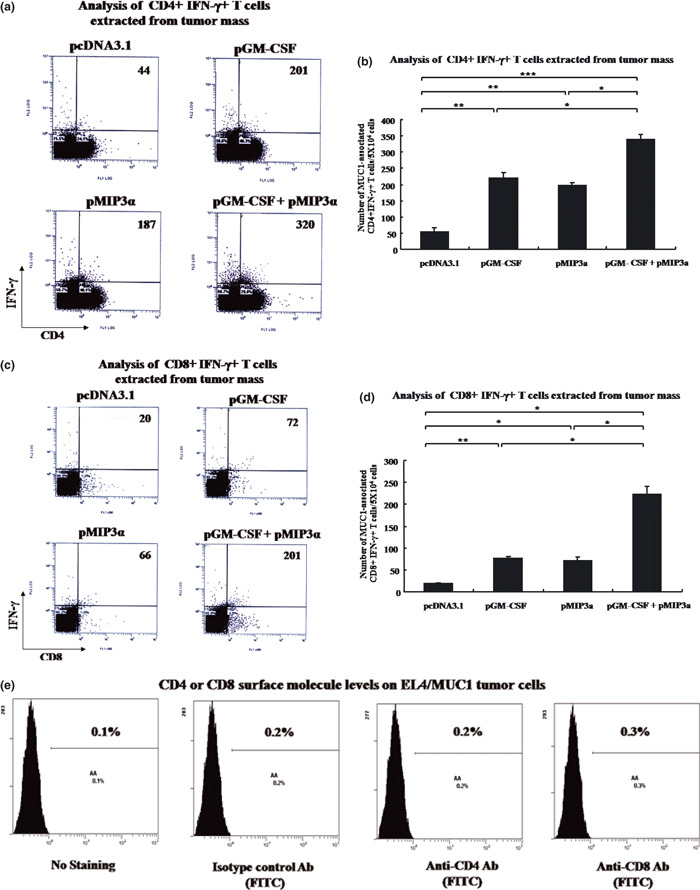

Phenotype marker analysis. To determine the levels of CD4 and CD8 surface molecule on EL4/MUC1, these cells were grown in 75‐cm2 flasks and incubated for 48 h at 37°C in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS. These cells were stained with FITC‐conjugated isotype antibody, FITC‐conjugated anti‐CD4 antibody (BD Pharmingen, Piscataway, NJ, USA) or FITC‐conjugated anti‐CD8 antibody (BD Pharmingen). Flow cytometric analysis was performed using Becton‐Dickson FACScan CELLQuest software (Becton Dickinson Immunocytometry System, San Jose, CA, USA). Additional supporting information may be found in online version of this article.

Results

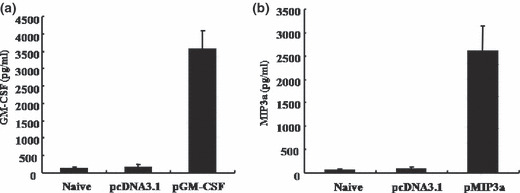

In vitro expressions of pGM‐CSF and pMIP3α. The in vitro transient expressions of GM‐CSF and MIP3α from pGM‐CSF and pMIP3α were determined in transfected EL4/MUC1 tumor cells by ELISA. Observed GM‐CSF expression levels were 123 ± 55, 155 ± 75 and 3568 ± 523 pg/mL in naive, pcDNA3.1 and pGM‐CSF transfected cells, respectively. ELISA assays showed that GM‐CSF protein levels in pGM‐CSF transfected EL4/MUC1 tumor cells were 29 times higher than in their pcDNA3.1 transfected counterparts (Fig. 1a). Observed pMIP3α expression levels were 55 ± 36, 75 ± 57, and 2578 ± 553 pg/mL in naive, pcDNA3.1 and pMIP3α transfected cells, respectively. These results showed that MIP3α protein levels in pMIP3α transfected EL4/MUC1 tumor cells were 46 times higher than in their pcDNA3.1 transfected counterparts (Fig. 1b).

Figure 1.

Expression of plasmid granulocyte macrophage colony stimulating factor (pGM‐CSF) and plasmid macrophage inflammatory protein‐3 alpha (pMIP3α) vectors in vitro. EL4/MUC1 tumor cells were transiently transfected with the pcDNA3.1 (0.4 μg/μL), pGM‐CSF (0.4 μg/μL) and pMIP3α (0.4 μg/μL) vector using the Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). (a,b) The expression of pGM‐CSF and pMIPα were determined by ELISA. Cell supernatants of EL4/MUC1 tumor cells transfected with pGM‐CSF or pMIPα were evaluated after 2 days. GM‐CSF and MIP3α were detected by ELISA after serially diluting supernatants. A representative result of three experiments is shown. Columns contain mean values. Bars are means ± SD.

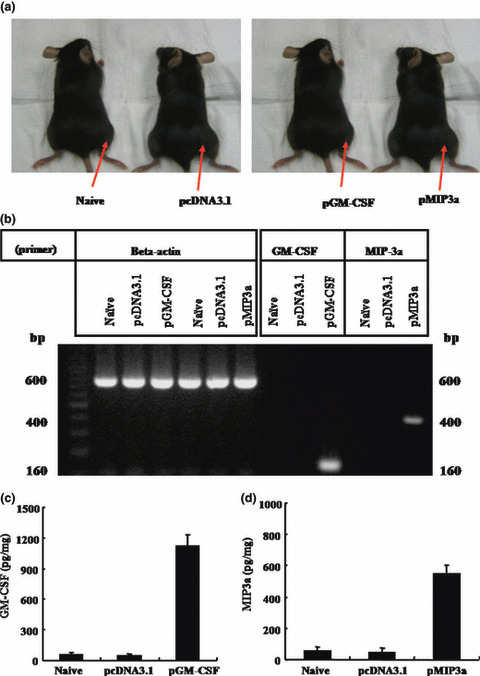

In vivo expressions of pGM‐CSF and pMIP3α. Figure 2a shows a diagram of various vector injection sites of the tumor mass. Tumors were excised 3 days after intratumoral injection and intratumoral cytokines were determined by RT‐PCR (Fig. 2b) and ELISA (Fig. 2c,d), as described in Materials and Methods. GM‐CSF and MIP3α mRNA were detected only in EL4/MUC1 tumors injected with pGM‐CSF and pMIP3α, respectively (Fig. 2b). Figure 2c,d shows the mean SD levels of GM‐CSF and MIP3α in picograms per milligram of total protein. The observed GM‐CSF expression levels were 62 ± 17, 55 ± 18 and 1050 ± 155 pg/mg in naive, pcDNA3.1 and pGM‐CSF transfected tumor cells, respectively. ELISA assays showed that GM‐CSF protein levels in pGM‐CSF transfected EL4/MUC1 tumor cells were 17 times higher than in their pcDNA3.1 transfected counterparts (Fig. 2c). Furthermore, pMIP3α expression levels were 56 ± 23, 48 ± 24 and 546 ± 55 pg/mg in naive, pcDNA3.1 and pMIP3α transfected tumor cells, respectively. These result showed that MIP3α protein levels in pMIP3α transfected EL4/MUC1 tumor cells were 11 times higher than in their pcDNA3.1 transfected counterparts (Fig. 2d).

Figure 2.

Expression of plasmid granulocyte macro‐phage colony stimulating factor (pGM‐CSF) and plasmid macrophage inflammatory protein‐3 alpha (pMIP3α) vectors in vivo. EL4/MUC1 tumor cells (5 × 104) were administered subcutaneously to C57BL/6 mice. After 10 days, tumors were injected with various vectors (pcDNA3.1, pGM‐CSF and pMIP3α). (a) A diagram of various vector injection sites of the tumor mass. Arrows indicate the injection sites. (b) RT‐PCR analysis. Tumors were excised 3 days after injecting pcDNA3.1, pGM‐CSF and pMIP3α. Total RNA was extracted using Trizol reagents. RT‐PCR products were generated from an mRNA template with a pair of primers specific for GM‐CSF or MIP3α. β‐actin was amplified using a β‐actin‐specific primer as a RNA quality control. (c,d) ELISA analysis. Tumors were excised 3 days after injecting pcDNA3.1, pGM‐CSF and pMIP3α. GM‐CSF and MIP3α expression was quantified in tumor homogenates by ELISA. A representative result of three experiments is shown. Columns contain mean values. Bars are means ± SD.

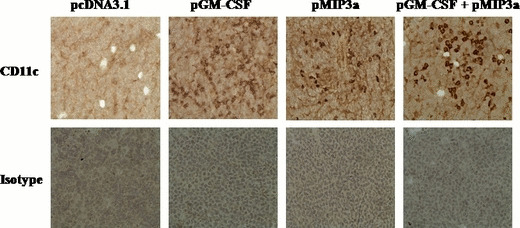

In vivo functions of pGM‐CSF plus pMIP3α in tumors. To quantify DC accumulations in tumors, EL4/MUC1 tumors were examined with anti‐CD11c antibody for the presence of DC at 7 days after the final administration of pcDNA3.1, pGM‐CSF alone, pMIP3α alone and pGM‐CSF plus pMIP3α. As shown in Figure 3, we analyzed the immunohistochemistry by counting the stained cells. Staining of CD11c+‐expressing cells was graded on a 0 ∼ 4 scale (0, no positive staining/×200; 1, <10 stained cells/×200; 2, 11∼30 stained cells/×200;3, 31∼50 stained cells/×200; 4, >50 stained cells/×200). Treatment with pGM‐CSF plus pMIP3α recruited higher numbers of tumor infiltrating CD11c+ DC than in the other three groups (pcDNA3.1, pGM‐CSF, pMIP3α, and pGM‐CSF plus pMIP3α, 0.57 ± 0.53 scale, 1.86 ± 0.38 scale, 2.00 ± 0.58 scale, and 3.57 ± 0.53 scale, respectively). pGM‐CSF alone (1.86 ± 0.38 scale) or pMIP3α alone (2.00 ± 0.58 scale) recruited limited number levels of CD11c+ DC (Table 1). Furthermore, pMIP3α alone did not increase CD11c+ DC infiltrates more than pGM‐CSF alone (Fig. 3, Table 1).

Figure 3.

Immunohistochemistry of tumor sections injected with various vectors (pcDNA3.1, plasmid granulocyte macrophage colony stimulating factor [pGM‐CSF], plasmid macrophage inflammatory protein‐3 alpha [pMIP3α], and pGM‐CSF plus pMIP3α). EL4/MUC1 tumor cells (5 × 104) were administered s.c. to C57BL/6 mice. The various vectors, namely pcDNA3.1, pGM‐CSF, pMIP3α, and pGM‐CSF plus pMIP3α, were injected intratumorally into the EL4/MUC1 tumors on days 10, 12 and 14 after tumor cell inoculation. Frozen tumor sections were stained with anti‐CD11c antibody or isotype IgG as a control (magnification, ×200). No staining was observed using isotype‐matched control antibodies. The result shown is representative of two experiments.

Table 1.

Immunohistochemical analysis of tumor mass from C57BL/6 mice at day 7 after co‐injection with pGM‐CSF and pMIP3α

| Plasmid injected | CD11c (SD) |

|---|---|

| pcDNA3.1 | 0.57 (0.53) |

| pGM‐CSF | 1.86 (0.38) |

| pMIP3a | 2.00 (0.58) |

| pGM‐CSF+ pMIP3α | 3.57 (0.53) |

Immunohistochemistry of sections of tumors injected with the various vectors (pcDNA3.1, pGM‐CSF, pMIP3α, and pGM‐CSF plus pMIP3α). The various vectors, namely pcDNA3.1, pGM‐CSF, pMIP3α, and pGM‐CSF plus pMIP3α were injected intratumorally into EL4/MUC1 tumors on days 10, 12 and 14 after tumor cell inoculation. Frozen tumor sections were stained with anti‐CD11c Ab or isotype IgG as a control (magnification, ×200). Staining of CD11c+‐expressing cells was graded on a 0 ∼ 4 scale: 0, no positive staining/×200); 1, <9 stained cells/×200); 2, 11∼30 stained cells/×200);3, <30‐50 stained cells/×200); 4, 31∼50 stained cells/×200). Results are given as an average of eight tumor masses). pGM‐CSF, plasmid granulocyte macrophage colony stimulating factor; pMIP3α, plasmid macrophage inflammatory protein‐3 alpha; SD, standard deviation.

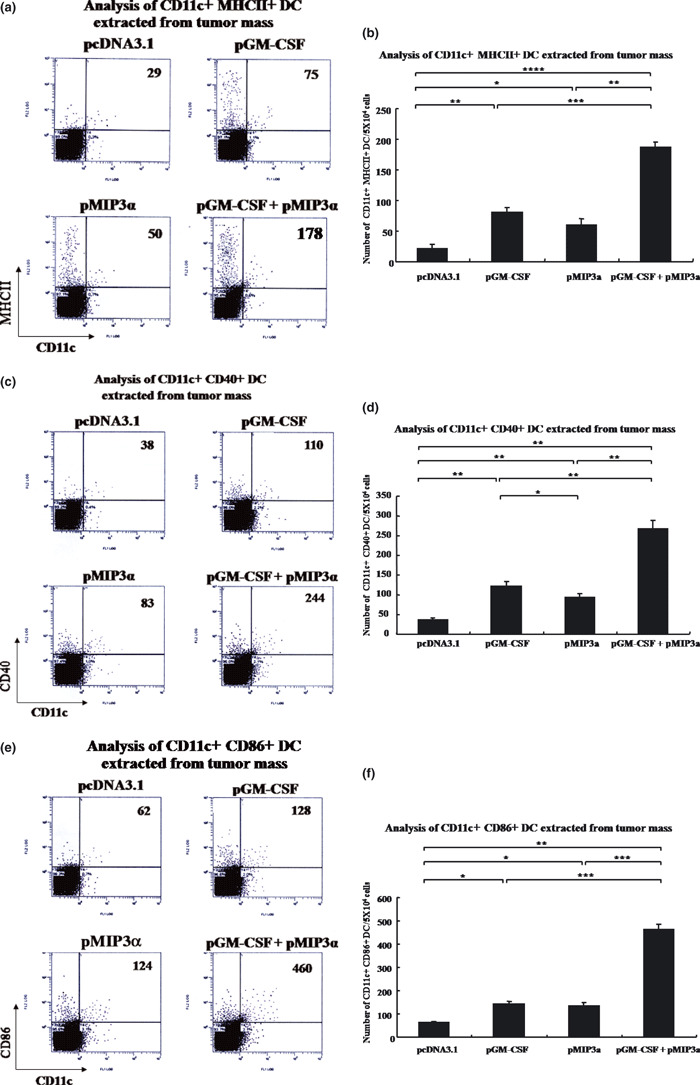

Strong increase in tumor‐infiltrating DC cell numbers by pGM‐CSF plus pMIP3α. The levels of activated CD11c+MHCII+, CD11c+CD40+ and CD11c+CD86+ DC in EL4/MUC1 tumors were measured in pcDNA3.1, pGM‐CSF alone, pMIP3α alone, and pGM‐CSF plus pMIP3α transfected tumor cells (Fig. 4). As shown in Figure 4a,b, higher numbers of CD11c+MHCII+ cells were found in mice treated with pGM‐CSF plus pMIP3α than in the other treated groups (pcDNA3.1, pGM‐CSF alone and pMIP3α alone). Furthermore, pGM‐CSF plus pMIP3α generated a significantly greater increase in CD11c+MHCII+ cell numbers (174 ± 18/5 × 104 tumor cells) than pcDNA3.1 (25 ± 5/5 × 104 tumor cells, P < 0.00005), which represents a 7.1‐fold increase in the number of CD11c+MHCII+ cells. Injections of pGM‐CSF alone (P < 0.0005 vs pcDNA3.1 or P < 0.0001 vs pGM‐CSF plus pMIP3α) and of pMIP3α alone (P < 0.05 vs pcDNA3.1 or P < 0.0005 vs pGM‐CSF plus pMIP3α) also enhanced CD11c+MHCII+ cell numbers but to a lesser extent (70 ± 7/5 × 104 tumor cells and 45 ± 8/5 × 104 tumor cells, respectively). As shown in Figure 4c,d,a higher number of CD11c+CD40+ cells were observed in mice treated with pGM‐CSF plus pMIP3α than in the other treated groups (pcDNA3.1, pGM‐CSF alone and pMIP3α alone). Furthermore, pGM‐CSF plus pMIP3α generated a significantly greater number of CD11c+CD40+ cells (231 ± 32/5 × 104 tumor cells) than pcDNA3.1 (32 ± 6/5 × 104 tumor cells, P < 0.005), which represents a 7.2‐fold increase. Injections with pGM‐CSF alone (P < 0.005 vs pcDNA3.1 or P < 0.005 vs pGM‐CSF plus pMIP3α) or pMIP3α alone (P < 0.005 vs pcDNA3.1 or P < 0.005 vs pGM‐CSF plus pMIP3α) still enhanced CD11c+CD40+ cell numbers but to a lesser extent (105 ± 10/5 × 104 tumor cells and 80 ± 12/5 × 104 tumor cells, respectively). Figure 4e,f shows higher numbers of CD11c+CD86+ cells were found in mice treated with pGM‐CSF plus pMIP3α than in the other treated groups (pcDNA3.1, pGM‐CSF alone and pMIP3α alone). Furthermore, pGM‐CSF plus pMIP3α generated a significantly greater number of CD11c+CD86+ cells (452 ± 28/5 × 104 tumor cells) than pcDNA3.1 (55 ± 5/5 × 104 tumor cells, P < 0.001), which represents an 8.2‐fold increase. Injections of pGM‐CSF alone (P < 0.005 vs pcDNA3.1 or P < 0.0005 vs pGM‐CSF plus pMIP3α) and pMIP3α alone (P < 0.005 vs pcDNA3.1 or P < 0.0005 vs pGM‐CSF plus pMIP3α) enhanced CD11c+CD86+ cells numbers but to a lesser extent (120 ± 13/5 × 104 tumor cells and 120 ± 15/5 × 104 tumor cells, respectively), which is consistent with our immunohistochemical results. These data show that pGM‐CSF plus pMIP3α exerted synergistic effects that substantially exceeded the sums of their individual effects.

Figure 4.

Analysis of dendritic cells (DC) extracted from tumors. (a) Representative set of flow cytometry data. (b) Columns contain mean numbers of CD11c+MHCII+ DC per 5 × 104 tumor cells. *P < 0.05. **P < 0.0005. ***P < 0.0001. ****P < 0.00005. (c) Representative flow cytometry data. (d) Columns contain mean numbers of CD11c+CD40+ DC per 5 × 104 cells. *P < 0.05. **P < 0.005. (e) Representative flow cytometry data. (f) Columns contain mean numbers of CD11c+CD86+ DC per 5 × 104 cells. *P < 0.005. **P < 0.001. ***P < 0.0005. A representative result of three experiments is shown. Bars are means ± SD. Five mice were examined per group. pGM‐CSF, plasmid granulocyte macrophage colony stimulating factor; pMIP3α, plasmid macrophage inflammatory protein‐3 alpha.

Numbers of CD8+ IFN‐γ+‐expressing T cells generated by MUC1‐loaded dendritic cells. We analyzed the effect of generation of CD8+ T cells on the function of tumor‐infiltrating DC. To determine whether GM‐CSF plus MIP‐3α therapy increased hMUC‐1 antigen presentation in tumor mass, various vectors (pcDNA3.1, pGM‐CSF, pMIP3α, and pGM‐CSF plus pMIP3α) were injected into EL4/MUC1 tumors on days 10, 12 and 14 after tumor inoculation. As shown in Supporting Information Figure S4a,b, enriched CD11c+ cells obtained from the tumor mass of animals administered the pGM‐CSF plus pMIP3α most effectively generated CD8+ IFN‐γ+‐expressing T cells (pcDNA3.1, pGM‐CSF, pMIP3α, and pGM‐CSF plus pMIP3α, 25 ± 7, 1610 ± 85, 1130 ± 102, and 2850 ± 310, respectively). In fact, a >110‐fold increase in the number of IFN‐γ‐secreting MUC1‐associated CD8+ T cells was found in mice administered the pGM‐CSF plus pMIP3α therapy compared with mice administered pcDNA3.1 (2850 ± 310 vs 25 ± 7). These results show that tumor‐bearing mice treated with the pGM‐CSF plus pMIP3α therapy generated higher levels of antigen‐loaded dendritic cells in the tumor mass, which are able to activate hMUC1‐associated CD8+ T cell immune responses.

Strong increase of DC cell numbers in draining lymph nodes by pGM‐CSF plus pMIP3α. We also observed an increased number of CD11c+MHCII+ cells (Supporting Information Figure S2a,b), CD11c+CD40+ cells (Supporting Information Fig. S2c,d) and CD11c+CD86+ cells (Supporting Information Fig. S2e,f) in draining lymph nodes after injecting pGM‐CSF alone, pMIP3α alone, and pGM‐CSF plus pMIP3α. The pGM‐CSF plus pMIP3α resulted in a robust increase in the number of activated DC cells compared with single therapy with pGM‐CSF alone or pMIP3α alone. pGM‐CSF alone or pMIP3α alone also increased in the number of activated DC cells more than pcDNA3.1, but these increases were less than that of pGM‐CSF plus pMIP3α.

Strong increase in tumor‐infiltrating CD4+ IFN‐γ+ T cells and CD8+ IFN‐γ+ T cell numbers by pGM‐CSF plus pMIP3α. As shown in Figure 5a,b, greater numbers of MUC1‐associated IFN‐γ‐secreting CD4+ T cells were observed in mice treated with pGM‐CSF plus pMIP3α than in the other treated groups (pcDNA3.1, pGM‐CSF alone and pMIP3α alone). pGM‐CSF plus pMIP3α generated a significantly greater increase in MUC1‐associated IFN‐γ‐secreting CD4+ T cell numbers (315 ± 22/5 × 104 tumor cells) than pcDNA3.1 (38 ± 12/5 × 104 tumor cells, P < 0.00005), which represents an 8.2‐fold increase (Fig. 5a,b). Injections of pGM‐CSF alone (P < 0.0005 vs pcDNA3.1 or P < 0.001 vs pGM‐CSF plus pMIP3α) and of pMIP3α alone (P < 0.0005 vs pcDNA3.1 or P < 0.001 vs pGM‐CSF plus pMIP3α) enhanced MUC1‐associated IFN‐γ‐secreting CD4+ T cell numbers but to a lesser extent (195 ± 16/5 × 104 tumor cells and 180 ± 9/5 × 104 tumor cells, respectively). These results show that pGM‐CSF plus pMIP3α significantly enhanced the MUC1‐associated CD4+ T cell immune response in the treated mice.

Figure 5.

Analysis of T cells extracted from tumor masses. (a) Representative set of flow cytometry data. (b) Columns contain mean numbers of MUC1‐associated IFN‐γ‐secreting CD4+ T cells per 5 × 104 cells. *P < 0.001. **P < 0.0005. ***P < 0.00005. (c) Representative flow cytometry data. (d) Columns contain mean numbers of MUC1‐associated interferon‐γ‐secreting CD8+ T cells per 5 × 104 cells. *P < 0.005. **P < 0.001. (e) CD4 or CD8 surface molecule levels on EL4/MUC1 tumor cells. A representative result of three experiments is shown. Bars are means ± SD. Five mice were examined per group. Ab, antibody; pGM‐CSF, plasmid granulocyte macrophage colony stimulating factor; pMIP3α, plasmid macrophage inflammatory protein‐3 alpha.

As shown in Fig. 5c,d, tumors from mice treated with pGM‐CSF plus pMIP3α (197 ± 24/5 × 104 tumor cells) showed significantly greater numbers of MUC1‐associated IFN‐γ‐secreting CD8+ T cells than tumors from mice treated with pcDNA3.1 (15 ± 3/5 × 104 tumor cells, P < 0.005), pGM‐CSF alone (65 ± 6/5 × 104 tumor cells, P < 0.005) and pMIP3α alone (60 ± 11/5 × 104 tumor cells, P < 0.005). pGM‐CSF alone (P < 0.001 vs pcDNA3.1) and pMIP3α alone (P < 0.005 vs pcDNA3.1) also enhanced MUC1‐associated IFN‐γ‐secreting CD8+ T cell numbers but to a lesser extent. These results show that pGM‐CSF plus pMIP3α enhances MUC1‐associated CD8+ T cell immune response. We also observed an increased number of CD4+ IFN‐γ+ T cells (Supporting Information Fig. S1a,b) and CD8+ IFN‐γ+ T cells (Supporting Information Fig. S1c,d) in the draining lymph nodes after injecting pGM‐CSF alone, pMIP3α alone, and pGM‐CSF plus pMIP3α. As shown shown in Supporting Information Figure S3, CTL against EL4/MUC1 cells in the pGM‐CSF‐plus‐pMIP3α‐treated mice had specific lysis percentages of 40, 24 and 18% at effector:target ratios of 40:1, 20:1 and 10:1, respectively. However, the specific lysis percentages of CTL against MUC1‐expressing EL4 cells in pcDNA3.1‐treated mice were only 4, 1.8 and 2.1% at effector:target ratios of 40:1, 20:1 and 10:1, respectively. Also, CD8+ T cells from pGM‐CSF+pMIP3α did not exhibit a lysis against a control tumor (EL4; no MUC1 expression). These results confirmed that pGM‐CSF plus pMIP3α induced a more potent antitumor response than any of the other treatments examined.

Effect on the induction of specific CD8+ T cell and CD4+ T cell accumulation by hMUC1 peptide. As shown in Supporting Information Figure S5a,b, the number of IFN‐γ‐secreting MUC1‐associated CD8+ T cells in pGM‐CSF plus pMIP3α was markedly higher than in the other three groups (pcDNA3.1, pGM‐CSF, pMIP3α, and pGM‐CSF plus pMIP3α, 3 ± 1/1 × 104 splenocytes, 140 ± 32/1 × 104 splenocytes, 118 ± 25/1 × 104 splenocytes, and 263 ± 51/1 × 104 splenocytes, respectively). Interestingly, the number of MUC1‐specific CD8+ IFN‐γ+ T cells in the GM‐CSF‐plus‐MIP3α‐treated mice was 87‐fold higher than in the pcDNA3.1 treated mice. Furthermore, the number of IFN‐γ‐secreting MUC1‐associated CD4+ T cells in the pGM‐CSF plus pMIP3α was markedly higher than in the other three groups (pcDNA3.1, pGM‐CSF, pMIP3α, and pGM‐CSF plus pMIP3α, 58 ± 13/5 × 104 splenocytes, 390 ± 75/5 × 104 splenocytes, 220 ± 47/5 × 104 splenocytes, and 760 ± 152/5 × 104 splenocytes, respectively). The number of MUC1‐specific CD4+ IFN‐γ+ T cells in the GM‐CSF‐plus‐MIP3α‐treated mice was 12‐fold higher than in the pcDNA3.1‐treated mice (as shown in Supporting Information Fig. S5c,d). These results show that a combination of pGM‐CSF and pMIP3α can significantly enhance tumor antigen‐specific CD8+ T cell (and CD4+ T cell) immune responses.

In vivo antibody depletion experiments. To determine the subsets of lymphocytes that are important for the observed antitumor effect generated by GM‐CSF plus MIP‐3α therapy, we performed an in vivo antibody depletion experiment (Supporting Information Fig. S5e); all of the mice depleted of CD8+ T cells grew tumors within 14 days of the EL4/MUC1 challenge. In contrast, 60% of mice with CD4+ T cell depletion and 80% of mice with no depletion remained tumor‐free 31 days after the EL4/MUC1 challenge. These data indicate that CD8+ T cells play a vital effector role in the antitumor defense generated by GM‐CSF plus MIP‐3α therapy. The percentage of tumor‐free mice in the CD8‐depleted group was significantly lower than the percentage of tumor‐free mice in the non‐depleted group (P < 0.05). CD4+ T cells might also contribute to the antitumor effect, although the numbers of tumor‐free CD4 depleted mice are not significantly different from the number of tumor‐free non‐depleted mice.

Enhanced antitumor response induced by pGM‐CSF plus pMIP3α. As shown in Figure 6a,b, the pGM‐CSF plus pMIP3α produced significantly better results than pcDNA3.1 (P < 0.005 on days 23–30). pGM‐CSF alone (P < 0.0005 on days 27–30) and pMIP3α alone (P < 0.001 on days 27–30) also inhibited tumor growth more than pcDNA3.1, but these inhibitions were less than that of pGM‐CSF plus pMIP3α (Fig. 6a). Furthermore, mice treated with pGM‐CSF plus pMIP3α (P < 0.01), pGM‐CSF alone (P < 0.05) and pMIP3α alone (P < 0.05) survived longer than mice treated with pcDNA3.1 (Fig. 6b). Treatment with pGM‐CSF plus pMIP3α (P < 0.01 vs pcDNA3.1; P < 0.05 vs pGM‐CSF alone; P < 0.05 vs pMIP3α alone), pGM‐CSF alone (P < 0.05 vs pcDNA3.1; no significance vs pMIP3α alone) and pMIP3α alone (P < 0.05 vs pcDNA3.1) increased the median survival time (MST; 60.7 ± 4.3, 43.5 ± 3.2 and 43.2 ± 2.2, respectively) (Table 2).

Figure 6.

In vivo tumor growth inhibition induced by plasmid granulocyte macrophage colony stimulating factor (pGM‐CSF) plus plasmid macrophage inflammatory protein‐3 alpha (pMIP3α) treatment. (a) Tumor sizes were measured using a caliper at 7, 11, 14, 17, 20, 23, 27 and 30 days after the tumor challenge. Tumor sizes were defined as length (mm) × width (mm). *P < 0.05. **P < 0.01. ***P < 0.005. ****P < 0.001. *****P < 0.0005. (b) Survival was defined as the percentage of animals surviving on a given day. *P < 0.05. **P < 0.01. A representative result of three experiments is shown. Bars are means ± SD. Five mice were examined per group.

Table 2.

Median survival time (MST) of mice

| Treatment | MST (days) |

|---|---|

| pcDNA3.133.4 ± 2.1 | |

| pGM‐CSF 43.5 ± 3.2* | |

| pMIP3a43.2 ± 2.2* | |

| pGM‐CSF + pMIP3a | 60.7 ± 4.3** |

EL4/MUC1 tumor cells (5×104) were resuspended in 0.1 mL of PBS and inoculated subcutaneously into the right hind legs of mice. pcDNA3.1, pGM‐CSF, pMIP3α, and pGM‐CSF plus pMIP3α vectors (100 μg each) were resuspended in 100 μL of PBS and injected into EL4/MUC1 tumors on days 10, 12 and 14 after tumor cell inoculation. pGM‐CSF plus pMIP3α (**P < 0.01 vs pcDNA3.1; *P < 0.05 vs pGM‐CSF alone; *P < 0.05 vs pMIP3α alone), pGM‐CSF alone (*P < 0.05 vs pcDNA3.1; no significance versus pMIP3α alone) and pMIP3α (*P < 0.05 vs pcDNA3.1). pGM‐CSF, plasmid granulocyte macrophage colony stimulating factor; pMIP3α, plasmid macrophage inflammatory protein‐3 alpha.

Discussion

In the present study, we tested the efficacy of pGM‐CSF plus pMIP3α therapy against EL4/MUC1 tumors. We found that pGM‐CSF plus pMIP3α resulted in dramatic recruitment and expansion of DC at tumor sites (Figs 3,4) and at the draining lymph nodes (Supporting Information Fig. S2) and generated the greatest MUC1‐associated CD8+ T‐cell immune response in the draining lymph nodes (Supporting Information Fig. S1c,d). In addition, pGM‐CSF plus pMIP3α induced a greater antitumor effect and enhanced survival more than pcDNA3.1, pGM‐CSF alone and pMIP3α alone (Fig. 6), and induced a more significant MUC1‐associated CD8+ T cell immune response in tumors (Fig. 5c,d) than pcDNA3.1, pGM‐CSF alone and pMIP3α alone. Another interesting result was that pGM‐CSF plus pMIP3α induced more significant CD4+ T cell immune response in tumors (Fig. 5a,b) and the draining lymph nodes (Supporting Information Fig. S1a,b) than pcDNA3.1, pGM‐CSF alone and pMIP3α alone. It has been previously suggested that some MUC1‐associated‐CD4+ T cells help generate and expand the CD8+ T cells in these mice.( 26 ) Thus, our data suggest that pGM‐CSF plus pMIP3α treatment potentially offers an effective means of controlling MUC1‐associated malignancies.

The adjuvant action of MIP‐3α is less well recognized than those of chemokines such as MIP‐1α. However, complete tumor regression was achieved when tumor cells were transduced with a retroviral vector carrying the MIP‐3α gene in a mouse model.( 27 ) In the present study, we are the first to provide evidence that pMIP3α possesses significant immunoadjuvant activity when injected without a DNA vaccine. Furthermore, MIP‐3α is the only chemokine ligand for CCR6, which is expressed on immature DC,( 28 , 29 ) memory T cells( 13 ) and B cells.( 30 ) In addition, the stimulation of epithelial cells induces recruitment of immature DC via the upregulation of MIP‐3α expression.( 31 ) Because immature DC have high endocytosis capacity and tumor Ag concentration is highest at the tumor mass, it seems logical to attract immature DC into the tumor mass to induce an antitumor immune response. It has been demonstrated that the capacity of DC to recruit the site of tumor is determined by their ability to respond to selected MIP‐3α. It appears to be one of the most chemotactic chemokines for immature DC.( 14 ) Thus, MIP‐3α triggers the initiation of adaptive immunity by attracting immature DC to sites of injection. In agreement with these observations, our study demonstrates that pMIP3α more potently activated MUC1‐associated CD8+ CTL than pcDNA3.1 (Supporting Information Fig. S3).

Granulocyte–macrophage colony‐stimulating factor has been suggested to be essential for regulating the survival, proliferation, differentiation and function of DC both in human and murine systems.( 21 , 32 , 33 ) Pan et al. ( 20 ) showed that APC, such as DC, are recruited and matured by the intratumoral gene delivery of GM‐CSF. Furthermore, GM‐CSF is a potential vaccine adjuvant and has been widely used as an adjuvant in clinical trials of cancer vaccines.( 34 , 35 )

In the present study, pGM‐CSF alone or pMIP3α alone recruited functionally immature DC to sites of inoculation, but was not enough to mobilize DC and induce effective antitumor activity (Fig. 4). In fact, prior studies have shown that MIP‐3α recruits DC to the sites of inoculation, and that GM‐CSF triggers the expansion and maturation of the recruited DC.( 32 , 33 , 36 ) However, we cannot exclude the possibility that plasmid GM‐CSF may also induce the chemotaxis of DC.( 20 , 37 ) Regardless of the precise mechanism involved, it is clear that pGM‐CSF plus pMIP3α was substantially more effective than treatment with either plasmid cytokine alone in terms of augmenting MUC1‐associated antitumor immune responses. However, further studies are required to explore the details of this mechanism.

We speculate that DC acquire tumor‐specific MUC1 antigen at tumor sites and then migrate to the draining lymph nodes where they prime naive T lymphocytes.( 38 ) This possibility is supported by the observation that T lymphocytes and DC were found in large numbers in tumor (Figs 4,5) and draining lymph node sections (Supporting Information Figs S1,S2). However, additional detailed studies are clearly required to determine the precise cell trafficking pathways associated with this priming of the immune response. In summary, the findings of the present study suggest that the co‐administration of pGM‐CSF and pMIP3α induces local accumulation of DC and a tumor‐specific CTL response, and inhibits tumor growth in vivo.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no financial and personal relationships with other people or organizations that could inappropriately influence (bias) this work.

Supporting information

Fig. S1. Analysis of T cells extracted from tumor‐draining lymph nodes.

Fig. S2. Analysis of DC extracted from tumor‐draining lymph nodes.

Fig. S3. Cytotoxic T cells directed against tumors after the intratumoral administration of pGM‐CSF plus pMIP3α.

Fig. S4. Numbers of hMUC1‐associated CD8+IFN‐γ+ T cells stimulated by tumor‐infiltrated dendritic cells of mice treated with the pGM‐CSF plus pMIP3α therapy.

Fig. S5. Flow cytometry analysis of MUC1‐specific T cell immune response and in vivo antibody depletion experiment.

Data S1. Materials and Methods: polymerase chain reaction; tumor model; immunohistochemistry; extraction and analysis of infiltrating DC or T cells; in vitro splenocyte cytotoxicity assays; restimulation of hMUC1‐associated CD8+ T cells by enriched CD11c+ cells from various vectors treated mice; the effect on the induction of specific CD8+ T cells and CD4+ T cells accumulation by hMUC1 peptide; in vivo antibody depletion experiment; and statistical analysis.

Supporting info item

Supporting info item

Supporting info item

Supporting info item

Supporting info item

Supporting info item

Supporting info item

Supporting info item

Supporting info item

Supporting info item

Supporting info item

Supporting info item

Supporting info item

Supporting info item

Supporting info item

Supporting info item

Supporting info item

Supporting info item

Supporting info item

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grants from the Cancer Research Center, the Korean Science and Engineering Foundation (KOSEF) through the Tumor Immunity Medical Research Center at Seoul National University College of Medicine, Korea. Y. Choi was supported by the BK21 Project for Medicine, Dentistry, and Pharmacy in South Korea (2009).

References

- 1. Bonnotte B, Favre N, Moutet M et al. Role of tumor cell apoptosis in tumor antigen migration to the draining lymph nodes. J Immunol 2000; 164: 1995–2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lee HK, Iwasaki A. Innate control of adaptive immunity: dendritic cells and beyond. Semin Immunol 2007; 19: 48–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cella M, Sallusto F, Lanzavecchia A. Origin, maturation and antigen presenting function of dendritic cells. Curr Opin Immunol 1997; 9: 10–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sogn JA. Tumor immunology: the glass is half full. Immunity 1998; 9: 757–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bonnotte B, Larmonier N, Favre N et al. Identification of tumor‐infiltrating macrophages as the killers of tumor cells after immunization in a rat model system. J Immunol 2001; 167: 5077–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nouri‐Shirazi M, Banchereau J, Bell D et al. Dendritic cells capture killed tumor cells and present their antigens to elicit tumor‐specific immune responses. J Immunol 2000; 165: 3797–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Banchereau J, Steinman RM. Dendritic cells and the control of immunity. Nature 1998; 392: 245–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Clark GJ, Angel N, Kato M et al. The role of dendritic cells in the innate immune system. Microbes Infect 2000; 2: 257–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Steinman RM, Inaba K, Turley S, Pierre P, Mellman I. Antigen capture, processing, and presentation by dendritic cells: recent cell biological studies. Hum Immunol 1999; 60: 562–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Banchereau J, Schuler‐Thurner B, Palucka AK, Schuler G. Dendritic cells as vectors for therapy. Cell 2001; 106: 271–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fong L, Engleman EG. Dendritic cells in cancer immunotherapy. Annu Rev Immunol 2000; 18: 245–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Caux C, Vanbervliet B, Massacrier C et al. Regulation of dendritic cell recruitment by chemokines. Transplantation 2002; 73: S7–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Liao F, Rabin RL, Smith CS, Sharma G, Nutman TB, Farber JM. CC‐chemokine receptor 6 is expressed on diverse memory subsets of T cells and determines responsiveness to macrophage inflammatory protein 3 alpha. J Immunol 1999; 162: 186–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dieu MC, Vanbervliet B, Vicari A et al. Selective recruitment of immature and mature dendritic cells by distinct chemokines expressed in different anatomic sites. J Exp Med 1998; 188: 373–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Abe J, Wakimoto H, Yoshida Y, Aoyagi M, Hirakawa K, Hamada H. Antitumor effect induced by granulocyte/macrophage‐colony‐stimulating factor gene‐modified tumor vaccination: comparison of adenovirus‐ and retrovirus‐mediated genetic transduction. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 1995; 121: 587–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dranoff G, Jaffee E, Lazenby A et al. Vaccination with irradiated tumor cells engineered to secrete murine granulocyte‐macrophage colony‐stimulating factor stimulates potent, specific, and long‐lasting anti‐tumor immunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1993; 90: 3539–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chiodoni C, Paglia P, Stoppacciaro A, Rodolfo M, Parenza M, Colombo MP. Dendritic cells infiltrating tumors cotransduced with granulocyte/macrophage colony‐stimulating factor (GM‐CSF) and CD40 ligand genes take up and present endogenous tumor‐associated antigens, and prime naive mice for a cytotoxic T lymphocyte response. J Exp Med 1999; 190: 125–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Curiel‐Lewandrowski C, Mahnke K, Labeur M et al. Transfection of immature murine bone marrow‐derived dendritic cells with the granulocyte‐macrophage colony‐stimulating factor gene potently enhances their in vivo antigen‐presenting capacity. J Immunol 1999; 163: 174–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hornell TM, Beresford GW, Bushey A, Boss JM, Mellins ED. Regulation of the class II MHC pathway in primary human monocytes by granulocyte‐macrophage colony‐stimulating factor. J Immunol 2003; 171: 2374–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Pan PY, Li Y, Li Q et al. In situ recruitment of antigen‐presenting cells by intratumoral GM‐CSF gene delivery. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2004; 53: 17–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Arca MJ, Krauss JC, Aruga A, Cameron MJ, Shu S, Chang AE. Therapeutic efficacy of T cells derived from lymph nodes draining a poorly immunogenic tumor transduced to secrete granulocyte‐macrophage colony‐stimulating factor. Cancer Gene Ther 1996; 3: 39–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Arca MJ, Krauss JC, Strome SE, Cameron MJ, Chang AE. Diverse manifestations of tumorigenicity and immunogenicity displayed by the poorly immunogenic B16‐BL6 melanoma transduced with cytokine genes. Cancer Immunol Immunother 1996; 42: 237–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fagerberg J. Granulocyte‐macrophage colony‐stimulating factor as an adjuvant in tumor immunotherapy. Med Oncol 1996; 13: 155–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Caux C, Ait‐Yahia S, Chemin K et al. Dendritic cell biology and regulation of dendritic cell trafficking by chemokines. Springer Semin Immunopathol 2000; 22: 345–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cyster JG. Chemokines and cell migration in secondary lymphoid organs. Science 1999; 286: 2098–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chen CH, Wang TL, Hung CF et al. Enhancement of DNA vaccine potency by linkage of antigen gene to an HSP70 gene. Cancer Res 2000; 60: 1035–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Furumoto K, Soares L, Engleman EG, Merad M. Induction of potent antitumor immunity by in situ targeting of intratumoral DCs. J Clin Invest 2004; 113: 774–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Greaves DR, Wang W, Dairaghi DJ et al. CCR6, a CC chemokine receptor that interacts with macrophage inflammatory protein 3alpha and is highly expressed in human dendritic cells. J Exp Med 1997; 186: 837–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Baba M, Imai T, Nishimura M et al. Identification of CCR6, the specific receptor for a novel lymphocyte‐directed CC chemokine LARC. J Biol Chem 1997; 272: 14893–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Liao F, Shirakawa AK, Foley JF, Rabin RL, Farber JM. Human B cells become highly responsive to macrophage‐inflammatory protein‐3 alpha/CC chemokine ligand‐20 after cellular activation without changes in CCR6 expression or ligand binding. J Immunol 2002; 168: 4871–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sierro F, Dubois B, Coste A, Kaiserlian D, Kraehenbuhl JP, Sirard JC. Flagellin stimulation of intestinal epithelial cells triggers CCL20‐mediated migration of dendritic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2001; 98: 13722–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Gunji Y, Tagawa M, Matsubara H et al. Antitumor effect induced by the expression of granulocyte macrophage‐colony stimulating factor gene in murine colon carcinoma cells. Cancer Lett 1996; 101: 257–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Yu JS, Burwick JA, Dranoff G, Breakefield XO. Gene therapy for metastatic brain tumors by vaccination with granulocyte‐macrophage colony‐stimulating factor‐transduced tumor cells. Hum Gene Ther 1997; 8: 1065–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Weber J, Sondak VK, Scotland R et al. Granulocyte‐macrophage‐colony‐stimulating factor added to a multipeptide vaccine for resected Stage II melanoma. Cancer 2003; 97: 186–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hodge JW, Chakraborty M, Kudo‐Saito C, Garnett CT, Schlom J. Multiple costimulatory modalities enhance CTL avidity. J Immunol 2005; 174: 5994–6004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Song R, Liu S, Leong KW. Effects of MIP‐1 alpha, MIP‐3 alpha, and MIP‐3 beta on the induction of HIV Gag‐specific immune response with DNA vaccines. Mol Ther 2007; 15: 1007–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Miller G, Pillarisetty VG, Shah AB, Lahrs S, Xing Z, DeMatteo RP. Endogenous granulocyte‐macrophage colony‐stimulating factor overexpression in vivo results in the long‐term recruitment of a distinct dendritic cell population with enhanced immunostimulatory function. J Immunol 2002; 169: 2875–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Dupuis M, Denis‐Mize K, Woo C et al. Distribution of DNA vaccines determines their immunogenicity after intramuscular injection in mice. J Immunol 2000; 165: 2850–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1. Analysis of T cells extracted from tumor‐draining lymph nodes.

Fig. S2. Analysis of DC extracted from tumor‐draining lymph nodes.

Fig. S3. Cytotoxic T cells directed against tumors after the intratumoral administration of pGM‐CSF plus pMIP3α.

Fig. S4. Numbers of hMUC1‐associated CD8+IFN‐γ+ T cells stimulated by tumor‐infiltrated dendritic cells of mice treated with the pGM‐CSF plus pMIP3α therapy.

Fig. S5. Flow cytometry analysis of MUC1‐specific T cell immune response and in vivo antibody depletion experiment.

Data S1. Materials and Methods: polymerase chain reaction; tumor model; immunohistochemistry; extraction and analysis of infiltrating DC or T cells; in vitro splenocyte cytotoxicity assays; restimulation of hMUC1‐associated CD8+ T cells by enriched CD11c+ cells from various vectors treated mice; the effect on the induction of specific CD8+ T cells and CD4+ T cells accumulation by hMUC1 peptide; in vivo antibody depletion experiment; and statistical analysis.

Supporting info item

Supporting info item

Supporting info item

Supporting info item

Supporting info item

Supporting info item

Supporting info item

Supporting info item

Supporting info item

Supporting info item

Supporting info item

Supporting info item

Supporting info item

Supporting info item

Supporting info item

Supporting info item

Supporting info item

Supporting info item

Supporting info item