Abstract

Natural killer (NK) cells are known to be critically involved in the control of tumors through their direct cytotoxic function, but have also been proposed as an initial source of interferon (IFN)‐γ that primes subsequent adaptive tumor‐specific immune responses. Although mounting evidence supports the importance of NK cells in antitumor immune responses, the immunological characteristics of NK cells infiltrating the tumor microenvironment and the mechanisms that regulate this process remain unclear. In the present study, we found that NK cells infiltrate early developing MCA205 tumors, and further showed that mature CD27high NK cells were the predominant subpopulation of NK cells accumulating in the tumor microenvironment. The tumor‐infiltrating NK cells displayed an activated cell surface phenotype and provided an early source of IFN‐γ. Importantly, we also found that host IFN‐γ was critical for NK cell infiltration into the local tumor site and that the tumor‐infiltrating NK cells mainly suppressed tumor growth via the IFN‐γ pathway. This work implicates the importance of IFN‐γ as a positive regulatory factor for NK cell recruitment into the tumor microenvironment and an effective antitumor immune effector response. (Cancer Sci 2011; 102: 1967–1971)

The tumor microenvironment is largely surrounded by stromal cells including inflammatory cells that secrete pro‐inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, and growth factors and enzymes that degrade extracellular matrixes, and as such this microenvironment is considered an important component of neoplastic disease. 1 , 2 , 3 Among such inflammatory cells in the tumor microenvironment, natural killer (NK) cells are known as innate lymphocytes that contribute to the early host immune response to cancer by their effector functions. (4) Natural killer cells recognize self‐MHC molecules and activating ligands on stressed, transformed or infected cells, thereby integrating signals transduced by various inhibitory and activating receptors, respectively. 5 , 6 , 7 Activated NK cells kill target cells or produce inflammatory cytokines such as interferon (IFN)‐γ, and therefore play an important role in the innate immune response. 4 , 8 In addition to these effector activities, a series of studies revealed that NK cells also influence adaptive immune responses through these same effector functions. 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 Moreover, recent studies discovered that subpopulations of NK cells show distinct tissue distribution and expression of homing and chemokine receptors. 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 Despite these advances, it has not yet been reported what type of NK cell is able to infiltrate into the tumor microenvironment and what mechanism regulates this process in tumor immune surveillance. Herein, we report that NK cells infiltrate at a very early phase of MCA205 tumor development and furthermore, mature CD27high NK cells are the predominant NK cell subpopulation within the tumor microenvironment. To characterize the tumor‐infiltrating NK cells, we investigated their cell surface phenotype and cytokine production. Using IFN‐γ−/− mice we also investigated the role of host IFN‐γ in promoting NK cell tumor infiltration and early antitumor immunity. Interferon‐γ was critical for NK cell infiltration into the local tumor site and those early tumor infiltrating NK cells mainly suppressed tumor growth by an IFN‐γ pathway.

Materials and Methods

Mice. Inbred wild‐type C57BL/6 (B6 WT) mice were purchased from CLEA Japan, Inc. (Tokyo, Japan). B6 IFN‐γ−/− mice were kindly provided by Dr Y. Iwakura (The University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan), and were bred and maintained at the Laboratory Animal Research Center, Institute of Medical Science, The University of Tokyo. All experiments were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Graduate School of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Institute of Medical Science of The University of Tokyo, and performed according to the guidelines of the Bioscience Committee of The University of Tokyo.

Antibodies and reagents. Purified monoclonal antibodies (mAb) reactive with mouse CD16/32 (2.4G2) and mouse NK1.1 (PK136) were all purified from hybridomas. Rabbit anti‐asialoGM1 (AGM1) Ab was purchased from Wako Chemicals (Osaka, Japan).

In vivo tumor challenge. MCA205, a methylcholanthrene‐induced murine fibrosarcoma cell line was kindly provided by Dr S. A. Rosenberg (National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD, USA) and maintained in complete RPMI 1640 medium. Groups of B6 WT or IFN‐γ−/− mice were injected s.c. with MCA205 cells (range, 1 × 105–4 × 105 cells) in 0.1 mL PBS. Tumor growth was measured by a caliper square measuring along the longer axes (a) and the shorter axes (b) of the tumors. Tumor volumes (mm3) were calculated by the formula: tumor volume (mm3) = ab 2/2. To deplete NK cells in vivo, mice were treated on days – 1, 0 and 7 (where day 0 is the day of primary tumor inoculation) with anti‐AGM1 (150 μg i.p.) or anti‐NK1.1 mAb (200 μg i.p.) as previously described. 24 , 25

Tumor‐infiltrating lymphocyte isolation and flow cyto‐metry. To isolate tumor‐infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL), tumor tissues were dissected, minced and digested with 2 mg/mL collagenase (Wako) and 0.1 mg/mL DNase I (Roche, Indianapolis, IN, USA) in serum‐free RPMI 1640 for 1 h at 37°C. Samples were then further homogenized through wire mesh and mononuclear cells (MNC) were isolated by Percoll gradient (30%). For flow cytometry analysis, MNC were first pre‐incubated with CD16/32 (2.4G2) mAb to avoid the non‐specific binding of antibodies to FcγR. The cells were then incubated with a saturating amount of mAb. Antibodies to CD3ε (2C11), NK1.1 (PK136), CD11b (M1/70), CD27 (LG.3A10), CD69 (H1.2F3), TRAIL (N2B2), CXCR3 (CXCR3‐173), NKG2D (CX5), H‐2Kb (AF6‐88.5) and pan‐Rae1 (186107) were purchased from Biolegend (San Diego, CA, USA), eBioscience (San Diego) or R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN, USA). Flow cytometric analysis was performed with a FACS Aria (BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA, USA) and data were analyzed with FlowJo software (Tree Star).

Ex vivo IFN‐γ production assay. Freshly isolated TIL were first incubated with Golgistop (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA, USA) for 2 h and then subjected to surface receptor staining. Cells were fixed and permeabilized using the BD Cytofix/Cytoperm kit (BD Bioscience) and then stained with PE‐conjugated IFN‐γ (XMG1.2; Biolegend).

Statistical analysis. Data were analyzed for statistical significance using the Student t‐test. P‐values <0.05 were considered significant.

Results

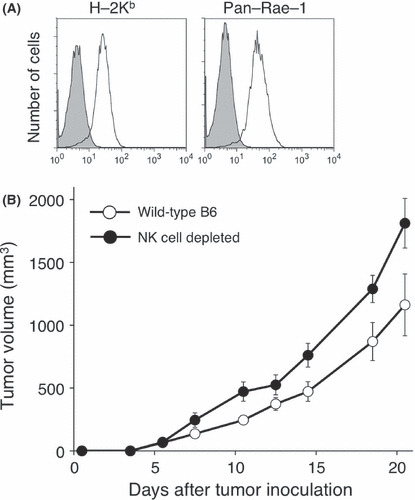

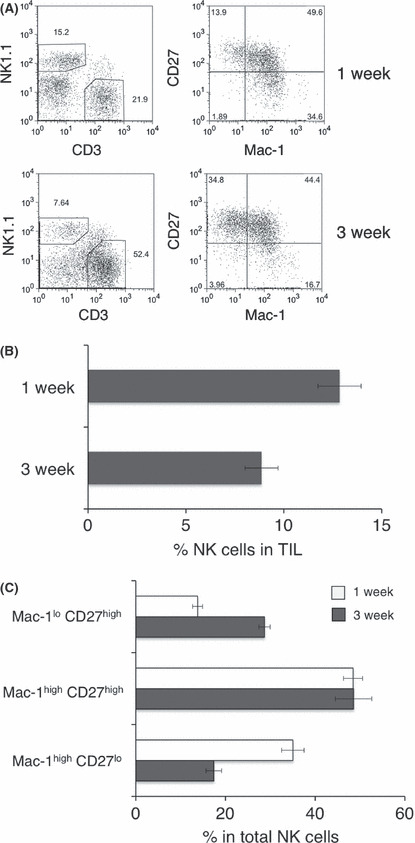

Early infiltration of NK cells controls MCA205 tumor growth. In a previous study, we reported the importance of endogenous IFN‐γ and the contribution of NK cells and T cells as effector cells in the control of MCA205 fibrosarcoma growth in vivo. (26) In order to further evaluate the importance of NK cells as early effector cells, we determined the contribution of NK cells in MCA205 subcutaneous growth by examining localization of NK cells into MCA205 tumors at 1 or 3 weeks after tumor inoculation. As shown in Figure 1, the growth of MHC class I+ NKG2D ligand+ MCA205 tumor was enhanced in NK cell‐depleted mice at 1 week, and such increased tumor growth was observed even at later time points (3 weeks). Within MCA205 TIL, NK cells represented a substantial lymphocyte population at both 1 and 3 weeks of tumor implantation (Fig. 2A,B). Functional subsets of mouse NK cells are determined by the expression of two markers, Mac‐1 (CD11b) and CD27, and the functional and phenotypic differences in those NK cell subsets are well characterized. 16 , 22 , 23 Thus, we analyzed the distribution of NK cell subsets defined by Mac‐1 and CD27 expression within MCA205 TIL. As shown in Figure 2A and C, we found that the mature Mac‐1high CD27high NK cell subset was the predominant population within the tumor‐infiltrating NK cells (approximately 50% of total NK cells) at both 1 and 3 weeks of tumor implantation. While the mature Mac‐1high CD27lo NK cell subset preferentially infiltrated early tumor, phenotypically immature Mac‐1lo NK cells tended to only be more prevalent in MCA205 tumors at a later time point. These results clearly indicate that early infiltration of NK cells into MCA205 tumors can be observed, and furthermore, that mature Mac‐1high CD27high NK cells are the predominant NK cell population infiltrating at both 1 and 3 weeks of MCA205 tumor implantation.

Figure 1.

Natural killer (NK) cell controls MCA205 tumor growth. (A) The expression of MHC class I (H‐2Kb) or NKG2D ligand (pan‐Rae‐1) was determined by flow cytometry (shaded histogram: control). (B) B6 mice were inoculated s.c. with MCA205 fibrosarcoma (4 × 105) with or without anti‐AGM1 treatment. Data are represented as the mean ± SEM.

Figure 2.

Early natural killer (NK) cell infiltration to MCA205 tumor. B6 mice were inoculated s.c. with MCA205 fibrosarcoma (4 × 105) and tumors were harvested at the indicated times after inoculation. Tumor‐infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL) were isolated and then subjected to flow cytometry analysis. The representative FACS plots from the indicated groups of mice are shown and the numbers represent the percentage of cells in the different gates (A). The proportion of NK cells (B, NK1.1+ CD3− cells) or NK cell subsets (Mac‐1lo CD27high, Mac‐1high CD27high, Mac‐1high CD27lo, electronically gated on NK1.1+ CD3− cells) from the indicated groups of mice are presented. The data represent the mean ± SEM and are representative of two experiments.

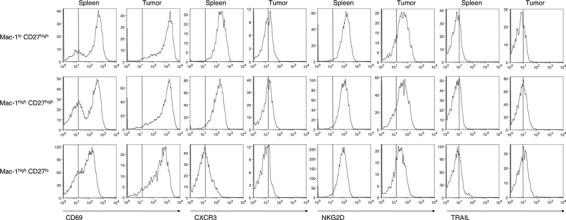

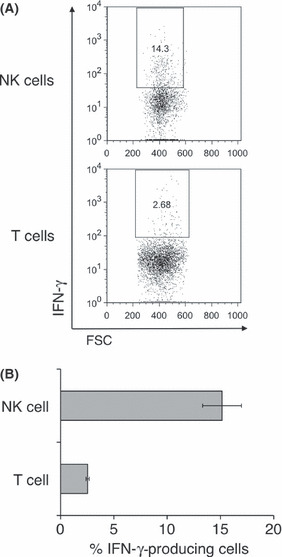

Early activation and IFN‐γ production of tumor infiltrating NK cells. It is generally recognized that the NK cell can be quickly activated and upregulate its effector function during immune responses. To clarify the exact role of tumor‐infiltrating NK cells in controlling tumor growth, we next characterized the activation status of early tumor‐infiltrating NK cells by flow cytometry. By analyzing cell surface markers on tumor‐infiltrating NK cells and splenic NK cells 1 week after MCA205 inoculation, we observed the significant upregulation of an early activation marker, CD69, on NK cells in the MCA205 tumor. In contrast, the chemokine receptor CXCR3 on Mac‐1lo CD27high and Mac‐1hi CD27high tumor‐infiltrating NK cell subsets was significantly downregulated when compared with expression on splenic NK cell subsets from the same tumor‐bearing mice (Fig. 3). The expression level of the activating receptor NKG2D was slightly lower on most of the tumor‐infiltrating NK cells when compared with the splenic NK cells from tumor‐bearing mice. Within tumor‐infiltrating NK cells, there was no alteration in the expression of the cytotoxic effector molecule TRAIL (Fig. 3), although we had previously observed activated NK cells express functional TRAIL via an IFN‐γ‐dependent pathway. (15) These results suggest that NK cells were activated by infiltrating into the MCA205 tumor at an early stage, causing altered expression of NKG2D but not TRAIL. In addition to their direct cytotoxic effector function, NK cells have been considered as an important source of IFN‐γ in antitumor immune responses; however, little is known about whether early tumor‐infiltrating NK cells can actually produce IFN‐γ within the tumor microenvironment. To directly determine whether early tumor‐infiltrating NK cells were a primary source of IFN‐γ within tumors, we isolated TIL from MCA205 tumors and measured cellular IFN‐γ production from lymphocytes without any additional stimulation in vitro. As shown in Figure 4, early infiltrating NK cells predominantly produced IFN‐γ at the tumor site when compared with infiltrating T cells. Collectively, these data clearly indicate the importance of NK cells, particularly mature Mac‐1high CD27high NK cells, as early activated effector cells providing initial IFN‐γ production among the tumor‐infiltrating lymphocyte subpopulations and effectively controlling MCA205 tumor growth.

Figure 3.

Characterization of early MCA205 tumor‐infiltrating natural killer (NK) cells. B6 mice were inoculated s.c. with MCA205 fibrosarcoma (4 × 105) and tumors were harvested 1 week after inoculation. Tumor‐infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL) were isolated and then subjected to flow cytometry analysis. The histogram plots shown are the expression levels for the indicated cell surface markers on the NK cell subsets in spleen or TIL electronically gated on the relevant population. Data are representative of two experiments (n = 4–5 mice).

Figure 4.

Early interferon (IFN)‐γ production of natural killer (NK) cells in MCA205 tumor. B6 mice were inoculated s.c. with MCA205 fibrosarcoma (4 × 105) and tumors were harvested 1 week after inoculation. Tumor‐infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL) were isolated and then incubated with Golgistop for 2 h without any in vitro stimulation. Cells were subjected to flow cytometry analysis to determine the intracellular level of IFN‐γ. (A) The dot plots show the population of IFN‐γ‐producing cells in TIL electronically gated on NK cells (NK1.1+ CD3−) or T cells (NK1.1− CD3+). (B) The proportion of IFN‐γ‐producing cells from NK cells or T cells is shown. The data represent the mean ± SEM and are representative of two experiments (n = 5 mice). FSC, forward light scatter.

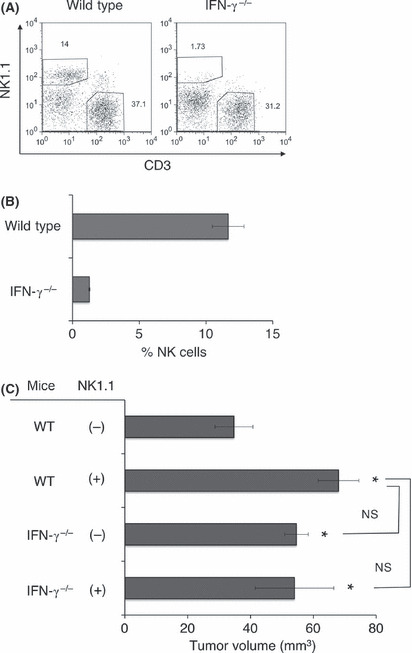

Host IFN‐γ is critical for effective NK cell infiltration into the tumor microenvironment. We have previously demonstrated the importance of host IFN‐γ in NK cell recruitment into lymph node following dendritic cell immunization. (27) To further clarify whether endogenous IFN‐γ also plays an important role in NK cell infiltration into tumors, we examined early NK cell infiltration into MCA205 tumors in IFN‐γ−/− mice. As shown in Figure 5A and B, it was very clear that host IFN‐γ deficiency severely impaired NK cell infiltration into MCA205 tumors throughout tumor development. Finally, we determined the importance of IFN‐γ in the NK cell‐dependent suppression of early MCA205 tumor growth. As shown in Figure 5C, tumor size was significantly enhanced in NK cell‐depleted mice or IFN‐γ−/− mice compared with WT mice within 7 days of MCA205 tumor inoculation. Importantly, NK cell depletion did not further enhance MCA205 tumor size in IFN‐γ−/− mice, suggesting the early tumor‐infiltrating NK cells mainly suppress MCA205 tumor growth through IFN‐γ‐mediated immune responses. Our results clearly highlight that the early tumor‐infiltrating NK cells might be primary antitumor effector cells and that host IFN‐γ is critically involved in early NK cell‐dependent antitumor immune responses.

Figure 5.

Importance of endogenous interferon (IFN)‐γ for natural killer (NK) cell MCA205 tumor infiltration and early antitumor immune responses. B6 wild‐type or IFN‐γ−/− mice were inoculated s.c. with MCA205 fibrosarcoma (4 × 105) and tumors were harvested 1 week after inoculation. Tumor‐infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL) were isolated and then subjected to flow cytometry analysis. The representative FACS plots from the indicated groups of mice are shown and numbers represent the percentage of cells in the different gates (A). The proportion of NK cells (NK1.1+ CD3− cells) from the indicated groups of mice are presented (B). The data represent the mean ± SEM and are representative of two experiments. (C) B6 mice or IFN‐γ−/− mice were inoculated s.c. with MCA205 fibrosarcoma (4 × 105) with or without anti‐NK1.1 treatment. The data are represented as the mean ± SEM on day 7 after tumor inoculation. *P < 0.05 compared with untreated wild‐type (WT) mice. NS, not significant.

Discussion

Natural killer cells have been recognized as early antitumor effectors through their direct cytotoxic functions. (4) Further recent evidence strongly supports that NK cells are important regulatory cells in antitumor immune responses by providing regulatory cytokines such as IFN‐γ. 6 , 11 Herein, we characterized the distribution of tumor‐infiltrating NK cell subpopulations, their activation status and their IFN‐γ production within tumors. Mature Mac‐1high CD27high NK cells infiltrated early MCA205 tumors and they displayed an activated cell surface phenotype and provided early IFN‐γ. Importantly, we also found that host IFN‐γ was critical for NK cell infiltration into tumors, implicating the importance of IFN‐γ as a positive regulatory factor for NK cell recruitment to tumors.

By investigating the expression of CD27 on naïve NK cells together with other NK cell maturation and differentiation markers, we previously showed that CD27 expression dissects the mature NK cell population into CD27high and CD27lo subsets. 16 , 22 Both types of mature Mac‐1high NK cells exert typical NK cell functions; however, CD27high cells have a lower threshold for activation than CD27lo cells whose activation is tightly regulated. 16 , 22 In addition to the effector function of NK cells, the diversity in tissue distribution of NK cells might be important for tissue resident/specific immune responses. In mice, the tissue distribution of NK cell subsets in various lymphoid and non‐lymphoid organs is quite distinct. 16 , 22 Interestingly, the CD27lo subset is comparatively excluded from bone marrow and lymph node, and is the dominant tissue‐resident NK cell population in peripheral tissues such as lung or blood. 16 , 22 In addition to such steady‐state tissue‐resident cells, NK cells appear to be rapidly recruited to tissues at the site of immune responses, and chemokines might play an important role in this process. Regarding the chemokine receptor expression on NK cells, it has been clearly shown that the chemokine receptor CXCR3 plays an important role in NK cell recruitment and the expression of CXCR3 ligands generally can be upregulated by IFN‐γ. 12 , 16 , 28 Among NK cell subpopulations, Mac‐1lo CD27high and Mac‐1high CD27high NK cells constitutively express CXCR3, whereas there was no detectable CXCR3 expression on CD27lo NK cells. 16 , 22 In the present study, we observed that the expression of CXCR3 on tumor‐infiltrating NK cells was severely downregulated, whereas the expression of CD69 was highly upregulated. Because such CXCR3 downregulation was not observed in splenic NK cells in the same tumor‐bearing mice, we assume the tumor microenvironment might preferentially down modulate NK cell CXCR3 expression. Considering the general importance of CXCR3 in NK cell mobilization, 12 , 16 , 28 the downregulation of CXCR3 on tumor‐infiltrating NK cells might be a key event that limits NK cell egress from the tumor microenvironment, maintaining NK cell immune surveillance. Alternatively, pre‐activated NK cells might be preferentially recruited into the tumor since in vivo activation of NK cells leads to a similar subset distribution and CXCR3 downregulation of NK cells. (29) Regarding the upregulation of CD69 expression on tumor‐infiltrating NK cells, there are several studies reporting that CD69 molecules negatively regulate NK cell antitumor immune responses. 30 , 31 Further study will be important in the context of NK cell homeostasis within the tumor microenvironment to further understand the detailed mechanisms of tumor escape from NK cells.

Such a critical requirement of host IFN‐γ was also seen in NK cell mobilization to other organs including implanted tumors with extracellular matrix Matrigel; 27 , 28 , 32 collectively the data indicate the general importance of IFN‐γ in maintaining NK cell infiltration to inflamed tissues. Of note, we observed that CD8 T‐cell infiltration into MCA205 tumor was also impaired in IFN‐γ−/− mice (data not shown), thus suggesting the importance of IFN‐γ as a key cytokine for maintaining antitumor effector cells within the tumor microenvironment. Despite the clear requirement of IFN‐γ in NK cell tumor infiltration, the detailed mechanism by which it regulates NK cell accumulation into the tumor microenvironment has not yet been determined. Further study will be required to fully understand NK cell behavior in the tumor microenvironment and successful establishment of effective immunotherapy for cancer.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgment

We thank Mark J. Smyth for critical reading of this manuscript. We are also grateful to Satomi Yoshinaga, Asuka Asami, Ruriko Miyake and Setsuko Nakayama for their technical assistance. This work was partly supported by a Grant‐in‐Aid for Young Scientists (21890044), the Global COE Program “Center of Education and Research for the Advanced Genome‐Based Medicine for personalized medicine and the control of worldwide infectious diseases,” The Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT), Japan, and the Takeda Science Foundation.

References

- 1. Mueller MM, Fusenig NE. Friends or foes – bipolar effects of the tumour stroma in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2004; 4: 839–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Albini A, Sporn MB. The tumour microenvironment as a target for chemoprevention. Nat Rev Cancer 2007; 7: 139–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Joyce JA, Pollard JW. Microenvironmental regulation of metastasis. Nat Rev Cancer 2009; 9: 239–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Smyth MJ, Hayakawa Y, Takeda K, Yagita H. New aspects of natural‐killer‐cell surveillance and therapy of cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2002; 2: 850–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lanier LL. NK cell recognition. Annu Rev Immunol 2005; 23: 225–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Raulet DH. Interplay of natural killer cells and their receptors with the adaptive immune response. Nat Immunol 2004; 5: 996–1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Yokoyama WM, Plougastel BF. Immune functions encoded by the natural killer gene complex. Nat Rev Immunol 2003; 3: 304–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cerwenka A, Lanier LL. Natural killer cells, viruses and cancer. Nat Rev Immunol 2001; 1 (1): 41–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cooper MA, Fehniger TA, Fuchs A, Colonna M, Caligiuri MA. NK cell and DC interactions. Trends Immunol 2004; 25: 47–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Moretta A. Natural killer cells and dendritic cells: rendezvous in abused tissues. Nat Rev Immunol 2002; 2: 957–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Degli‐Esposti MA, Smyth MJ. Close encounters of different kinds: dendritic cells and NK cells take centre stage. Nat Rev Immunol 2005; 5: 112–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Martin‐Fontecha A, Thomsen LL, Brett S et al. Induced recruitment of NK cells to lymph nodes provides IFN‐gamma for T(H)1 priming. Nat Immunol 2004; 5: 1260–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Scharton TM, Scott P. Natural killer cells are a source of interferon gamma that drives differentiation of CD4+ T cell subsets and induces early resistance to Leishmania major in mice. J Exp Med 1993; 178: 567–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kim S, Iizuka K, Kang HS et al. In vivo developmental stages in murine natural killer cell maturation. Nat Immunol 2002; 3: 523–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Takeda K, Cretney E, Hayakawa Y et al. TRAIL identifies immature natural killer cells in newborn mice and adult mouse liver. Blood 2005; 105: 2082–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hayakawa Y, Smyth MJ. CD27 dissects mature NK cells into two subsets with distinct responsiveness and migratory capacity. J Immunol 2006; 176: 1517–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cooper MA, Fehniger TA, Caligiuri MA. The biology of human natural killer‐cell subsets. Trends Immunol 2001; 22: 633–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dalbeth N, Gundle R, Davies RJ, Lee YC, McMichael AJ, Callan MF. CD56bright NK cells are enriched at inflammatory sites and can engage with monocytes in a reciprocal program of activation. J Immunol 2004; 173: 6418–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fehniger TA, Cooper MA, Nuovo GJ et al. CD56bright natural killer cells are present in human lymph nodes and are activated by T cell‐derived IL‐2: a potential new link between adaptive and innate immunity. Blood 2003; 101: 3052–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ferlazzo G, Thomas D, Lin SL et al. The abundant NK cells in human secondary lymphoid tissues require activation to express killer cell Ig‐like receptors and become cytolytic. J Immunol 2004; 172: 1455–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Freud AG, Becknell B, Roychowdhury S et al. A human CD34(+) subset resides in lymph nodes and differentiates into CD56bright natural killer cells. Immunity 2005; 22: 295–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hayakawa Y, Huntington ND, Nutt SL, Smyth MJ. Functional subsets of mouse natural killer cells. Immunol Rev 2006; 214: 47–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Silva A, Andrews DM, Brooks AG, Smyth MJ, Hayakawa Y. Application of CD27 as a marker for distinguishing human NK cell subsets. Int Immunol 2008; 20: 625–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ogasawara K, Takeda K, Hashimoto W et al. Involvement of NK1+ T cells and their IFN‐gamma production in the generalized Shwartzman reaction. J Immunol 1998; 160: 3522–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hayakawa Y, Takeda K, Yagita H et al. Critical contribution of IFN‐gamma and NK cells, but not perforin‐mediated cytotoxicity, to anti‐metastatic effect of alpha‐galactosylceramide. Eur J Immunol 2001; 31: 1720–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kaiga T, Sato M, Kaneda H, Iwakura Y, Takayama T, Tahara H. Systemic administration of IL‐23 induces potent antitumor immunity primarily mediated through Th1‐type response in association with the endogenously expressed IL‐12. J Immunol 2007; 178: 7571–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Watt SV, Andrews DM, Takeda K, Smyth MJ, Hayakawa Y. IFN‐gamma‐dependent recruitment of mature CD27(high) NK cells to lymph nodes primed by dendritic cells. J Immunol 2008; 181: 5323–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wendel M, Galani IE, Suri‐Payer E, Cerwenka A. Natural killer cell accumulation in tumors is dependent on IFN‐gamma and CXCR3 ligands. Cancer Res 2008; 68: 8437–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hayakawa Y, Watt SV, Takeda K, Smyth MJ. Distinct receptor repertoire formation in mouse NK cell subsets regulated by MHC class I expression. J Leukoc Biol 2008; 83: 106–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Esplugues E, Sancho D, Vega‐Ramos J et al. Enhanced antitumor immunity in mice deficient in CD69. J Exp Med 2003; 197: 1093–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Esplugues E, Vega‐Ramos J, Cartoixa D et al. Induction of tumor NK‐cell immunity by anti‐CD69 antibody therapy. Blood 2005; 105: 4399–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wald O, Weiss ID, Wald H et al. IFN‐gamma acts on T cells to induce NK cell mobilization and accumulation in target organs. J Immunol 2006; 176: 4716–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]